Abstract

Free full text

Alpha Interferon Potently Enhances the Anti-Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Activity of APOBEC3G in Resting Primary CD4 T Cells

Abstract

The interferon (IFN) system, including various IFNs and IFN-inducible gene products, is well known for its potent innate immunity against wide-range viruses. Recently, a family of cytidine deaminases, functioning as another innate immunity against retroviral infection, has been identified. However, its regulation remains largely unknown. In this report, we demonstrate that through a regular IFN-α/β signal transduction pathway, IFN-α can significantly enhance the expression of apolipoprotein B mRNA-editing enzyme-catalytic polypeptide-like 3G (APOBEC3G) in human primary resting but not activated CD4 T cells and the amounts of APOBEC3G associated with a low molecular mass. Interestingly, short-time treatments of newly infected resting CD4 T cells with IFN-α will significantly inactivate human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) at its early stage. This inhibition can be counteracted by APOBEC3G-specific short interfering RNA, indicating that IFN-α-induced APOBEC3G plays a key role in mediating this anti-HIV-1 process. Our data suggest that APOBEC3G is also a member of the IFN system, at least in resting CD4 T cells. Given that the IFN-α/APOBEC3G pathway has potent anti-HIV-1 capability in resting CD4 T cells, augmentation of this innate immunity barrier could prevent residual HIV-1 replication in its native reservoir in the post-highly active antiretroviral therapy era.

Cellular APOBEC3G belongs to a family of proteins that have cytidine deaminase activity (13, 25, 40). Albeit they could restrict the mobility of endogenous retroviruses and long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons, their normal functions in host cells remain largely unknown (3, 11). Recently, they were identified to potently inhibit the replication of various retroviruses, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), simian immunodeficiency virus, and type C retroviruses, as well as hepatitis B virus and endogenous retroviruses (2, 8, 11, 19, 25, 35, 42). APOBEC3G can either edit the newly synthesized viral DNA or have an inhibitory effect at another site(s) of the viral life cycle (16, 17, 33, 40). For surviving, retroviruses encode various gene products to counteract the inhibition of cytidine deaminases. In the case of HIV-1 and many other lentiviruses, virion infectivity factor (Vif) is encoded to effectively counteract the antiviral effect of APOBEC3G and APOBEC3F by facilitating the degradation of these cytidine deaminases (25, 36, 42). Alternatively, a recent study has shown that in resting primary CD4 T cells, APOBEC3G may play a major role to significantly restrict wild-type HIV-1 replication at the early stage of the viral life cycle (5). These newly discovered defense and antidefense mechanisms from the host have prompted us to further exploit the regulatory network of this innate immunity system.

Alpha interferon (IFN-α) is one of a cytokine family that exhibits antiviral properties and was discovered as an antiviral agent during studies on virus interference. It exerts antiviral activity through multiple pathways, including PKR (double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase)/eukaryotic initiation factor 2α, oligoadenylate synthetase-mediated RNase L, adenosine deaminase, and protein GTPase Mx/nitric oxide synthetase (24). In this report, we suggest that in addition to these antiviral pathways, IFN-α exerts its anti-HIV-1 activity through APOBEC3G in resting CD4 T cells. We have shown that APOBEC3G mRNA and protein level are substantially up-regulated in the presence of exogenous human (h)-IFN-α in resting CD4 T cells derived from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). Importantly, the low-molecular-mass (LMM)-associated APOBEC3G is also enhanced. The potent and irreversible inhibitory effect of IFN-α upon reverse transcription and viral infectivity, which is mediated by APOBEC3G, has raised the possibility that enhancement of APOBEC3G protein level may completely destruct residual HIV-1 replication in resting CD4 T cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation and culture of primary cells.

The fresh human PBMC were isolated from healthy human subjects (provided by the blood bank of Thomas Jefferson University Hospital) by using histopaque (Sigma). The resting primary CD4 T lymphocytes were isolated from PBMC by using CD4 T cell isolation kit II (Miltenyl), with which PBMC were depleted of CD8+, CD14+, CD19+, CD56+, CD36+, CD123+, CD235a+, CD16+, and anti-T-cell receptor γ/δ+ cells by direct immunomagnetic labeling, using antibodies against their respective surface markers. The isolated resting CD4 T cells were maintained in RPMI 1640-conditioned medium. The activated primary CD4 T cells were obtained by stimulation with phytohemagglutinin (PHA) (5 μg/ml) for 48 h, followed by maintenance with interleukin-2 (IL-2) (25 U/ml; Sigma).

Construction of chimeric report gene.

The promoter of h-ABOBEC3G (1.95 kb) was generated by PCR, using an elongase amplification system (Invitrogen) with primers 5′-GATACGCGTGCTAGCAAAGATGAAAACAATCCCACCTCACCCAGCG-3′ (sense) and 5′-GATAGATCTAAGCTTCTGGCAGAGGGACCTCTGATAAAGACAGGCCGCTCTGTGC-3′ (antisense). The template DNA was extracted from H9 cells using a genomic DNA isolation kit (Sigma). Cleaved 1.95-kb DNA with restriction enzymes NheI and HindIII was ligated into pGL3 basic plasmid (Promega) harboring a luciferase reporter gene. The 1.5-kb, 0.9-kb, and 0.4-kb promoters of h-APOBEC3G were produced by PCR or cleaved by various restriction enzymes. The 1.5-kb promoter DNA containing the IFN-stimulated response element (ISRE) mutant (GTTTCACTTCTT to GTTTCACGGCTT) was generated by PCR-based mutagenesis.

siRNA synthesis.

The short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) used in the experiments were chemically synthesized by Dharmacon. The APOBEC3G-specific siRNA was siGENOME SMART pool (catalog no. M-013072); the interferon regulatory factor 9 (IRF9)-specific siRNA was siGENOME SMART pool (catalog no. M_020858-01). The luciferase-specific siRNA served as a negative control. The sequence in its positive strand is 5′-CTTACGCTGAGTACTTCGA-3′.

Transfection.

The chimeric plasmids and control plasmids were transfected into 293T cells using Fugene 6 reagent (Roche). The plasmids or siRNAs were transfected into primary CD4 T cells, using an Amaxa nucleofector apparatus (Amaxa Biosystems). The U-14 program was selected for the resting CD4 T cells, while the T-23 program was selected for the activated CD4 T cells. The procedures suggested by the manufacturer were followed. The cells were then maintained in RPMI 1640-conditioned medium.

Flow cytometric analysis.

CD4+ T cells were isolated from fresh human PBMC, using MACS CD4 T cell isolation kit II (Miltenyi), and maintained in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. For activation, the cells were stimulated with PHA (5 μg ml−1) for 48 h, followed by IL-2 (25 U ml−1) for 24 h, and then subjected to flow cytometric analysis as described previously (34). For analysis of the effect of siRNA transfection, fresh resting CD4+ T cells were transfected with various siRNAs, using an Amaxa nucleofector II apparatus, and subjected to flow cytometric analysis at 72 h posttransfection.

Gel mobility shift assay.

Nuclear proteins were prepared by using the urea extraction method, and the gel mobility shift assay was performed as described previously (14, 15). Briefly, resting CD4 T cells treated with or without recombinant IFN-α (300 U/ml; Sigma) for 7 h were lysed with 0.6% NP-40 lysis buffer. After the cells were vortexed for 15 seconds, nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 20 s and resuspended in 10-pellet volumes of extraction buffer. After incubation on ice for 30 min, the mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was collected, and glycerol was added to a final concentration of 10%. The protein concentration of the nuclear extract was determined by the Lowry method. Conversely, synthesized wild-type ISRE-like nucleotide (5′-CTGGCTGTTTCACTTCTTTTGTGT-3′) and mutant nucleotide (5′-CTGGCTGTTTCACGGCTTTTGTGT-3′) and their complementary strands (5′-ACACAAAAGAAGTGAAACAGCCAG-3′ and 5′-ACACAAAAGCCGTGAAACAGCCAG-3′) were annealed to form double-stranded DNA and then labeled with [γ-32P]dATP. The labeled probes were purified with a G-25 column (Amersham). The nuclear extract (10 μg) was incubated with 2 μg poly(dI-dC)n in 50 μl binding buffer on ice for 20 min. Approximately 2 × 104 to 6 × 104 cpm (1 to 5 ng) of a 32P-labeled double-stranded DNA fragment was added to the preincubated nuclear extract mixture and continued to be incubated on ice for 50 min. DNA-protein complexes were resolved on 6% polyacrylamide gels in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer at 350 V for 3 h. The gel was dried and autoradiographed overnight. For the competition experiment, 100-fold excess unlabeled competitor oligonucleotides were added to the reaction mixture before the labeled DNA fragment was added.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay.

The experiment was performed as described previously, with minor modifications (7, 20). Briefly, resting CD4 T cells isolated from human PBMC were cultured in 12-well plates (2 × 107/well) and treated with or without IFN-α (300 U/ml) for 7 h. Formaldehyde was added directly to the medium to a final concentration of 1% and incubated in 37°C for 10 min. The fixed cells were washed twice, lysed with 200 μl sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) lysis buffer (Upstate), and then subjected to sonication. The sonicated samples were diluted to 2 ml. Immunoprecipitation was carried out by the addition of mouse anti-STAT2 antibody (Santa Cruz) or anti-β-actin antibody (Sigma) and incubation at 4°C overnight. Protein A agarose-salmon sperm DNA beads (Upstate) were applied to the reaction mixture and incubated at 4°C for 1 h. After being washed, the bead-associated DNA was eluted with fresh elution buffer (1% SDS, 0.1 M NaHCO3) and recovered with 5 M NaCl at 65°C for 4 h. A DNA sample was extracted with phenol-chloroform, followed by ethanol precipitation. Purified DNA samples were amplified with PCR for 30 cycles, using two primer pairs. Oligo 1 primers are for target cis element sequences: 5′-CAAAGGCGGTCATCTGTTGTCAGC-3′ (upstream, nucleotides [nt] −1126 to −1103) and 5′-GAAGTGAAACAGCCAGTTTCTCCC-3′ (downstream, nt −935 to −958). Oligo 2 primers served as a negative control: 5′-ATCAGAAGACCACAGACCATGGAC-3′ (upstream, nt −1715 to −1691) and 5′-GACAGAGTGAGACTCCATCTCA-3′ (downstream, nt −1486 to −1507).

Luciferase assay.

Luciferase enzymatic activity was detected with luminous reaction substrate (Promega) by using an FB 12 luminometer (DLR). The instructions of the manufacturer were followed.

Western blotting.

Proteins were extracted using CytoBuster protein extraction reagent (Novagen) and then quantified by a bicinchoninic acid protein assay reagent kit (Pierce). The procedure recommended by the manufacturer was followed. The immunoblotting assays were performed as described previously (39, 40). Rabbit polyclonal anti-APOBEC3G antibody was contributed by ImmunoDiagnostics, Inc., and obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program.

Real-time RT-PCR.

Resting CD4 T cells were treated with or without IFN-α for various hours or various doses, followed by RNA extraction using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). RNA was then reverse transcribed using an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). The cDNAs of APOBEC3G and GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) were amplified using iQSYBR green supermix (Bio-Rad) in a PCR buffer containing 100 mM KCl, 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.4), 0.4 mM of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 50 U/ml iTaq DNA polymerase, 6 mM MgCl2, SYBR green I, and 20 nM fluorescein. Quantitative reverse transcription (RT)-PCR for each sample was normalized using GAPDH as an endogenous control. The primers for h-APOBEC3G detection were 5′-TCAGAGGACGGCATGAGACTTAC-3′ (upstream) and 5′-AGCAGGACCCAGGTGTCATTG-3′ (downstream). The primers for GAPDH detection were 5′-GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGT-3′ (upstream) and 5′-GAAGATGGTGATGGGATTTCC-3′ (downstream). Data analysis and calculation were performed according to the 2ΔCT comparative method applied for the MyiQ single-color real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad).

Fast-protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) assay.

The resting and activated CD4 T cells were treated with or without IFN-α (300 U/ml). The cells were collected after 7 h of treatment and lysed with lysing buffer (6 mM Na2HPO4, 4 mM NaH2PO4, 1% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 0.1% proteinase inhibitor cocktail). The concentrated 3-ml protein samples were loaded into a HiPrep 26/60 Sephacryl S-300 HR column (Amersham Biosciences), driven by the LKB FRAC-100 system (Pharmacia) at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min, and eluted with elution buffer (0.05 M sodium phosphate, 0.15 M NaCl, 0.04% NaN3, pH 7.2). All fractions were concentrated with a centrifugal filter (Amicon Ultra-15 10000 MWCO; Millipore) and subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) analysis, followed by Western blot analysis.

Intracellular reverse transcription.

Resting CD4 T cells purified from human PBMC were transfected with various siRNAs. At 72 h postinfection, DNase-treated HIV-1NL4-3 viruses (5 ng p24 equivalent) were allowed to infect the resting or PHA-stimulated CD4 T cells with or without IFN-α. After 4 h, the unbound viruses were removed and infected cells were maintained in the conditioned medium in the presence of soluble CD4 molecule (10 μg/ml) and with or without IFN-α (300 U/ml). The cells were harvested at 48 h postinfection. DNA was extracted and subjected to PCR and Southern blot analysis, as described previously (9, 38).

Viral infection.

Wild-type HIV-1NL4-3 viruses were produced from 293T cells by transfection with pNL4-3. After determination of the 50% tissue culture infective dose, viruses were then allowed to infect the resting CD4 T cells (3 × 106) transfected with or without APOBEC3G-specific siRNA or luciferase-specific siRNA. The infected CD4 T cells were cultured in 12-well plates, treated with or without IFN-α (300 U/ml) for various periods, and subjected to stimulation with PHA (5 μg/ml) or without PHA for 48 h. The activated cells were maintained in the RPMI 1640-conditioned medium containing IL-2 (25 U/ml). The supernatant in each well was harvested every 3 or 4 days, and p24 detection was performed using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit as described previously (38).

RESULTS

Expression of APOBEC3G is up-regulated by IFN-α in human resting CD4 T cells.

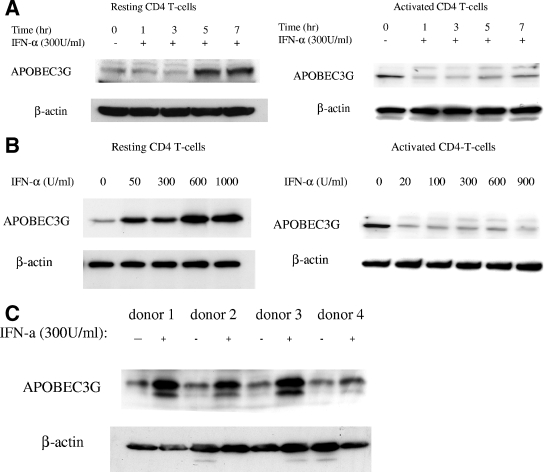

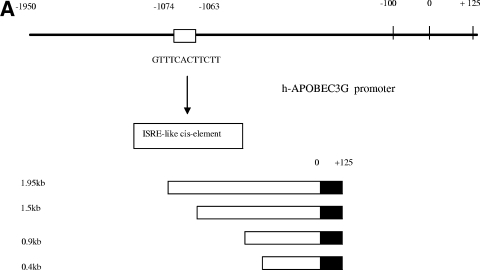

In order to search for the cellular factor(s) that regulates the expression of APOBEC3G, we have examined the possible influence of various cytokines on the expression of APOBEC3G, based upon the putative binding sites of various transcriptional factors in the promoter region of APOBEC3G. We found that IFN-α can significantly enhance the expression of APOBEC3G in resting primary CD4 T cells isolated from PBMC of healthy blood donors (Fig. 1A to C). The resting condition of these cells was further confirmed by examining the expression of CD25 and CD69 markers analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (Fig. (Fig.1D).1D). This enhancement cannot be observed in T-cell lines such as H9, C8166, and SupT-1 (data not shown). The enhancement of APOBEC3G expression by IFN-α in resting CD4 T cells becomes highly notable at 5 h postincubation (Fig. (Fig.1A)1A) and is dose dependent (Fig. (Fig.1B).1B). Importantly, this phenomenon can be observed in resting primary CD4 T cells isolated from multiple healthy blood donors (Fig. (Fig.1C).1C). In contrast to its actioninresting CD4 cells, IFN-α inhibits the expression of APOBEC3G in activated primary CD4 cells (Fig. 1A and B).

Expression of APOBEC3G is up-regulated by IFN-α in human resting CD4 T cells. (A) Time course study. Recombinant IFN-α (300 U/ml; Sigma) was added to the cultures of resting (left) or activated (right) primary CD4 T cells. The expression of APOBEC3G protein was detected at various time points. (B) Dose-dependent effect of IFN-α upon APOBEC3G expression in resting (left) or activated (right) CD4 T cells. Resting or activated CD4 T cells were treated with IFN-α at different concentrations. The cell lysates were prepared at 7 h posttreatment and subjected to Western blotting. (C) The resting CD4 T cells were prepared from four independent healthy blood donors and were treated with IFN-α for 7 h. The cell lysates were then prepared and subjected to Western blot analysis. Loading controls were carried out by detecting β-actin expression with an immunoblotting assay using mouse monoclonal antibody to human β-actin. The data (A to C) represent at least three independent experiments. (D) Flow cytometric analysis of activation status of resting CD4 T cells after nucleofection or activated CD4 T cells. The cells were labeled with anti-CD25 fluorescein isothiocyanate antibody, anti-CD69 allophycocyanin antibody, or an isotype control (arrows) and subjected to fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis. Similar results were obtained using cells from four different donors.

Transcriptional regulation of APOBEC3G expression by IFN-α.

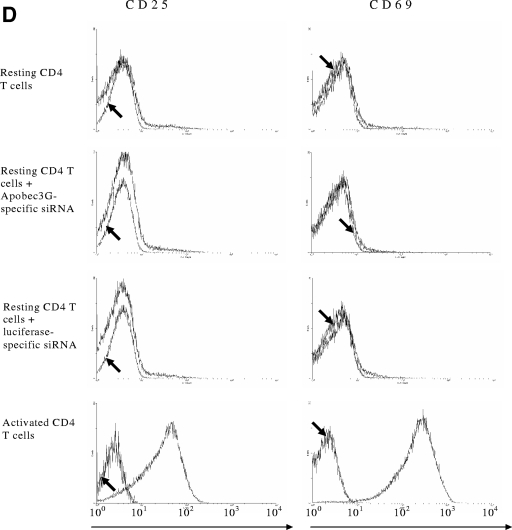

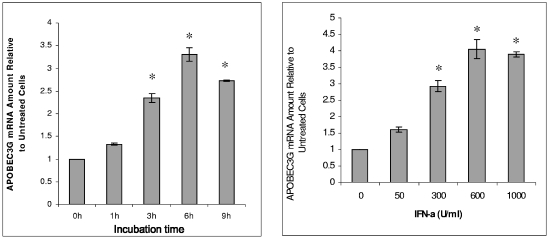

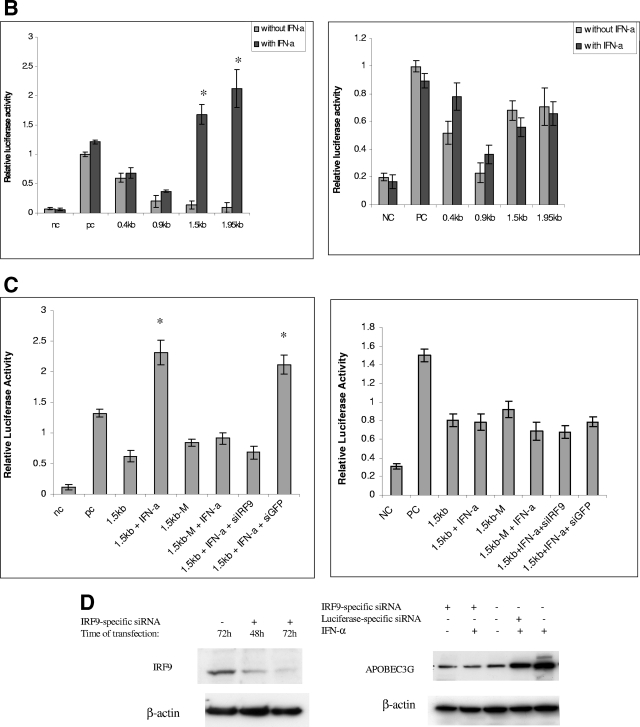

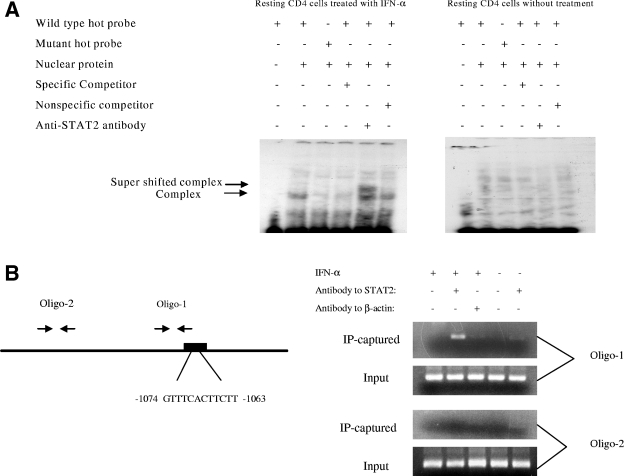

The amount of mRNA of APOBEC3G in resting CD4 T cells is increased in the presence of IFN-α (Fig. (Fig.2),2), suggesting that the enhancement of APOBEC3G expression by IFN-α could take place at the transcriptional level. We have identified an ISRE-like sequence in the promoter region of APOBEC3G, which is located at the region spanning bp −1074 to −1063 (Fig. (Fig.3A).3A). In the presence of this ISRE, IFN-α can significantly enhance the promoter activity of APOBEC3G in resting CD4 T cells (Fig. 3A and B). Mutations introduced at the ISRE site significantly decreased the augmenting effect of IFN-α upon the promoter activity of APOBEC3G (Fig. (Fig.3C).3C). As IRF9 is part of the IFN-stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3) complex and is required for the interaction between the ISGF3 complex and ISRE (31), we then examined whether inhibition of IRF9 expression can block the IFN-α-induced activity of the APOBEC3G promoter. As the expression of IRF9 is effectively decreased through an RNA interference assay (Fig. (Fig.3D),3D), the enhancement of APOBEC3G promoter activity by IFN-α is inhibited, either in an APOBEC3G promoter-driven luciferase system (Fig. (Fig.3C)3C) or in a wild-type APOBEC3G expression system (Fig. (Fig.3D).3D). In vitro gel mobility shifting experiments indicate that this ISRE sequence can specifically bind to the nuclear proteins extracted from resting primary CD4 T cells treated with IFN-α but not those without IFN-α treatment. The binding between the nuclear proteins and the ISRE-like sequence can be inhibited by a sequence-specific competitor. Mutations at the ISRE region can prevent this interaction. Anti-STAT2 antibody can supershift the binding complex, further suggesting that the ISGF3 complex, which is composed of STAT1, STAT2, and IRF9, can specifically bind to the ISRE region (Fig. (Fig.4A).4A). Moreover, the IFN-α-induced interaction between the ISGF3 complex and the ISRE element in the APOBEC3G promoter region in resting CD4 T cells can be identified by a chromatin immunoprecipitation assay, in which anti-STAT2 antibody can specifically capture the cis ISRE (Fig. (Fig.4B).4B). All of these results indicate that IFN-α up-regulates the activity of the APOBEC3G promoter through the classical IFN-α pathway (24). Interestingly, the promoter activity of APOBEC3G in activated CD4 T cells cannot be significantly affected by IFN-α (Fig. (Fig.3B).3B). Therefore, the decreased expression of APOBEC3G in activated CD4 T cells in the presence of IFN-α could be due to the accelerated degradation of APOBEC3G.

IFN-α enhances APOBEC3G mRNA expression in resting CD4 T cells. Total cellular RNA was extracted from resting CD4 T cells at 7 h after the addition of IFN-α (300 U/ml) into cell culture. The mRNA level of APOBEC3G was analyzed by real-time RT-PCR. (Left) Time course study. The amounts of APOBEC3G mRNA at 3 h, 6 h, and 9 h are significantly higher than that at time zero (asterisk, P < 0.001, t test). (Right) Dose-dependent experiment. The amounts of APOBEC3G mRNA induced by 300 U/ml, 600 U/ml, and 1,000 U/ml of IFN-α are significantly higher than that without IFN-α treatment (*, P < 0.001, t test).

Transcriptional regulation of APOBEC3G expression by IFN-α. (A) (Top) The APOBEC3G promoter at a 1.95-kb length was amplified using genomic DNA from H9 cells as a template and subjected to sequential deletion analysis. An ISRE-like sequence was identified in 1.95-kb DNA. (Bottom) The APOBEC3G promoters at various lengths (0.4 kb, 0.9 kb, 1.5 kb, and 1.95 kb) were constructed and placed upstream of the luciferase reporter gene. (B) Resting (left) or activated (right) CD4 T cells were transfected with various chimeric plasmids, followed by treatment with or without IFN-α (300 U/ml). Cell lysates were prepared at 24 h posttransfection, and luciferase activity was examined. The addition of IFN-α into resting CD4 T cells significantly enhances the activities of the 1.5-kb and 1.9-kb promoters (*, P < 0.001, t test) (right). (C) The resting (left) or activated (right) CD4 T cells were transfected, respectively, with a 1.5-kb promoter plasmid or plasmid containing a 1.5-kb promoter with a mutant ISRE-like sequence and treated with or without various siRNAs or treated with or without IFN-α (300 U/ml). The cell lysates were harvested at 24 h posttransfection, followed by detection of luciferase activity. In resting CD4 T cells, compared with the activity of the 1.5-kb promoter, the 1.5-kb M promoter, the 1.5-kb M promoter treated with IFN-α, or the 1.5-kb promoter treated with IFN-α and IRF9-specific siRNA, the activity of the 1.5-kb promoter treated with IFN-α or the 1.5-kb promoter plus green fluorescent protein (GFP)-specific siRNA treated with IFN-α was significantly increased (*, P < 0.001, t test). (D) The resting CD4+ T cells were transfected with or without IRF9-specific siRNA. At certain time points, the cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting using anti-IRF9 antibody (left). The resting CD4 T cells transfected with or without various siRNAs were treated with or without IFN-α (300 U/ml). Cells were collected at 7 h post-IFN-α treatment, and the APOBEC3G level (right) was analyzed using immunoblotting. NC, negative control plasmid without any promoter; PC, positive control plasmid containing cytomegalovirus promoter; 1.5kb-M, 1.5-kb chimeric plasmid containing mutations in the ISRE-like sequence; siIRF9, IRF9-specific siRNA; siGFP, GFP-specific siRNA.

IFN-α-induced ISGF3 complex binds to ISRE-like sequence. (A) The ISRE-like sequence in the h-APOBEC3G promoter specifically binds to nuclear proteins from resting CD4 T cells treated with IFN-α. Resting CD4 cells were treated with or without IFN-α (300 U/ml) for 7 h, and nuclear proteins were extracted. 32P-labeled nucleotides containing the ISRE-like sequence or its mutant were incubated with or without nuclear proteins. As a control, anti-STAT2 antibody was added for supershifting. The mixtures were resolved in a 6% native PAGE gel. The gel was dried and autoradiographed overnight. (B) Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay. The resting CD4 T cells were treated with or without IFN-α and fixed with formaldehyde. After sonication to break down long chromatin filament, the samples were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-STAT2 or anti-β-actin antibody. DNA was then extracted from the precipitated complex and subjected to PCR with two primer pairs. The PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis.

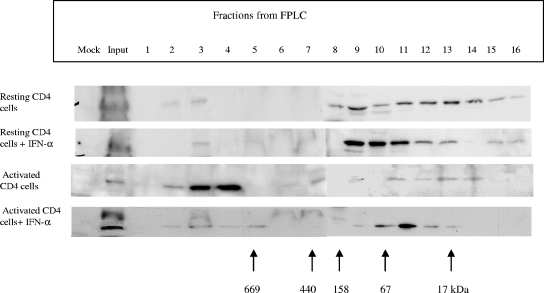

IFN-α enhances the association of APOBEC3G with an LMM.

It has been shown that in resting CD4 T cells, APOBEC3G is associated with an LMM by which it is active and able to perform DNA deamination and inhibit HIV-1 replication (5). To investigate the status of increased APOBEC3G induced by IFN-α in resting CD4 T cells, we performed FPLC assays to analyze the complex with which the increased APOBEC3G is associated. We found that the majority of increased APOBEC3G induced by IFN-α in resting CD4 T cells is associated with an LMM (Fig. (Fig.5).5). These data suggest that, as described previously (5), the increased APOBEC3G by IFN-α could have anti-HIV-1 activity. It is interesting that albeit IFN-α decreases the concentration of APOBEC3G in activated CD4 T cells, IFN-α induces the association of APOBEC3G with an LMM in activated CD4 T cells (Fig. (Fig.55).

Effect of IFN-α upon APOBEC3G in an LMM complex. The resting primary CD4 T cells were treated with or without IFN-α (300 U/ml) and harvested at 7 h after stimulation. The supernatants of cell lysates were concentrated and loaded into an FPLC column with 0.05 M sodium phosphate at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. Eluted fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by an immunoblotting assay with anti-APOBEC3G antibody. Cell lysates from the activated CD4 T cells with or without IFN-α treatment were also analyzed as controls.

IFN-α potently inhibits HIV-1 replication in initially resting CD4 T cells through APOBEC3G.

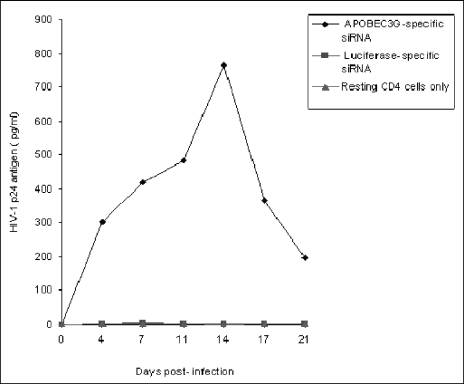

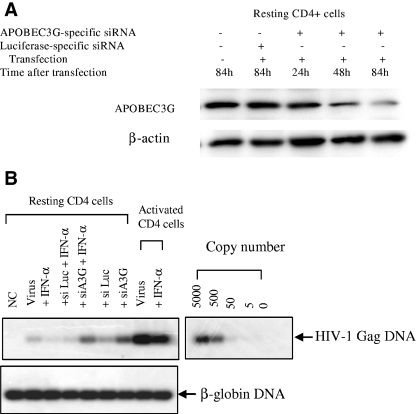

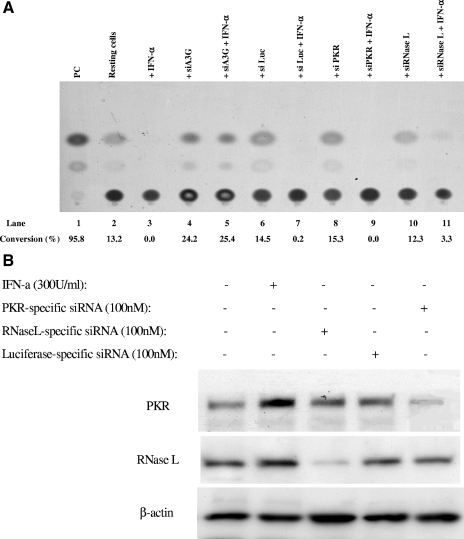

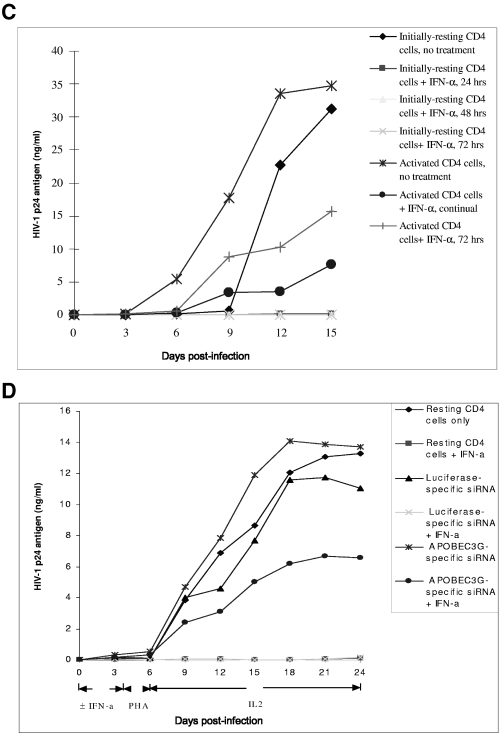

It has been well known that in cell cultures, HIV-1 could initially infect resting primary CD4 T cells and stay in a preintegration latency condition. Upon T-cell activation, HIV-1 can extend its life cycle and generate the progeny viruses (4, 29, 37). Recent studies have suggested that APOBEC3G associated with an LMM could be largely responsible for this preintegration latency (5). It is demonstrated that APOBEC3G-specific siRNA is capable of down-regulating the expression of APOBEC3G, thus allowing HIV-1 to infect resting CD4 T cells in a single-round infection assay (5). To further verify this interesting phenomenon, we have examined the effect of APOBEC3G-specific siRNA upon the replication of wild-type HIV-1 in resting CD4 T cells. We found that APOBEC3G-specific siRNA indeed can rescue the wild-type HIV-1 replication in resting CD4 T cells (Fig. (Fig.6).6). To investigate the effect of the IFN-α/APOBEC3G pathway upon HIV-1 replication in resting CD4 T cells, IFN-α was added to cell cultures during the resting stage of cells to enhance the expression of APOBEC3G. As shown in Fig. Fig.7B,7B, IFN-α treatment can significantly inhibit reverse transcription in resting CD4 T cells. However, APOBEC3G-specific siRNA, which can effectively decrease APOBEC3G in resting CD4 T cells (Fig. (Fig.7A),7A), can rescue reverse transcription and counteract the inhibitory effect of IFN-α. Further, a single-round infection experiment has also demonstrated that IFN-α potently inhibits the viral infectivity at an early event (Fig. (Fig.8A,8A, lanes 3 and 7). As this inhibitory effect can be significantly rescued by APOBEC3G-specific siRNA (Fig. (Fig.8A,8A, lane 5), we propose that the IFN-α/APOBEC3G pathway has a potent antiviral activity in resting CD4 cells. It is notable that we used a thin-layer chromatographic assay to process the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) assay. After an enzymatic reaction, the hydrophobic chloramphenicol was extracted with ethyl acetate. During this procedure, a minor contamination from aqueous phase may occur. These very few hydrophilic materials could slightly change the shape of spots formed by modified or unmodified chloramphenicol. Under the influence of the minor hydrophilic materials, the center part of the spots becomes the thinnest part of the spots (hollow). However, it should not affect the final result. The density of whole spots formed by modified or unmodified 14C-labeled chloramphenicol is measured by a phosphorimager. Similar results have been reported by other researchers (27).

APOBEC3G-specific siRNA makes the resting CD4 T cells purified from fresh human PBMC permissive to wild-type HIV-1 replication. The resting CD4 T cells (3 × 106) were transfected with or without APOBEC3G-specific siRNA (100 nmol/ml) or luciferase-specific siRNA (100 nmol/ml). After 72 h, the transfected cells were infected with HIV-1NL4-3 viruses (multiplicity of infection, 0.1). After being washed, the infected cells were cultured in RPMI 1640-conditioned medium without any mitogen or cytokine stimulation. The p24 antigen of HIV-1 viruses in the supernatant was detected via ELISA every 3 or 4 days.

APOBEC3G-mediated inhibitory effect of IFN-α upon intracellular reverse transcription. (A) Resting CD4 T cells were transfected with APOBEC3G-specific siRNA (100 nmol/ml) or luciferase-specific siRNA (100 nmol/ml). Cells were collected at different time points after transfection, and APOBEC3G levels were detected by an immunoblotting assay. (B) Resting or activated CD4 T cells, transfected with or without various siRNAs, were infected by DNase-treated HIV-1 viruses. The infected cells were treated with or without IFN-α. At 48 h postinfection, the cells were harvested and viral gag DNA was detected with PCR, using SK38/SK39 as the primer pair and SK19 as the probe. As a control, β-globin DNA was also detected.

IFN-α potently inhibits HIV-1 replication in initially resting CD4 T cells through APOBEC3G. (A) APOBEC3G-specific siRNA mediates potent inhibition of IFN-α upon HIV-1 infectivity in a single-round viral infection. Three plasmids, pMD.G, pCMVΔR8.2, and HIV-CAT (derived from pHR′ by replacing the LacZ gene with the CAT gene), were transfected into 293T cells (18). The supernatants were harvested after 72 h, and the recombinant viruses were further concentrated by ultracentrifugation. Conversely, the resting CD4 T cells purified from human PBMC were transfected with various siRNAs. After 72 h, the cells were infected with the concentrated recombinant viruses (20 ng p24 equivalent per cell sample [2 × 106]) with or without IFN-α treatment. After 4 h, the unbound viruses were washed off and the infected cells were maintained in a conditioned medium with or without IFN-α (300 U/ml). At 96 h postinfection, IFN-α was removed and PHA and IL-2 were added to activate the cells. After 48 h, the cells were harvested and a CAT assay was performed. (B) Effect of IFN-α and siRNA upon the expression of PKR and RNase L in resting CD4 T cells. The resting CD4 T cells purified from human PBMC were treated with IFN-α (300 U/ml) or transfected with PKR-specific siRNA or RNase L-specific siRNA. At 7 h posttreatment or 72 h posttransfection, the cells were harvested and subjected to Western blot analysis, using anti-PKR antibody (BD), anti-RNase L antibody (Abcam), or anti-β-actin antibody. (C) HIV-1NL4-3 viruses were allowed to infect resting or PHA-activated CD4 T cells (3 × 106) (multiplicity of infection, 0.1). Simultaneously, the infected cells were treated with or without IFN-α (300 U/ml) for various periods. For the infected activated CD4 T cells, the culture was maintained in RPMI 1640-conditioned medium containing IL-2 (25 U/ml). The HIV-1 p24 antigen in the supernatant was harvested every 3 days and detected by ELISA. For the infected resting CD4 T cells, however, PHA (5 μg/ml) was added into the cultures at 72 h postinfection. After 48 h, PHA was removed and the activated cells were cultured in RPMI 1640-conditioned medium containing IL-2 (25 U/ml). The HIV-1 p24 antigen in the supernatant was harvested every 3 days and detected by ELISA. (D) The resting CD4 T cells (3 × 106) were transfected with or without APOBEC3G-specific siRNA or luciferase-specific siRNA. After 72 h, the transfected or untransfected resting CD4 T cells were infected with HIV-1NL4-3 viruses (multiplicity of infection, 0.1) for 4 h. Simultaneously, the infected cells were treated with or without IFN-α (300 U/ml) for 96 h. After IFN-α was washed off, PHA (5 μg/ml) was added to stimulate the cells for 48 h. After PHA was removed, the activated cells were cultured in RPMI 1640-conditioned medium containing IL-2 (25 U/ml). The HIV-1 p24 antigen in the supernatant was harvested every 3 days and detected by ELISA. These data represent at least three independent experiments.

As PKR- and RNase L-specific siRNA, which can effectively decrease the concentration of PKR or RNase L in resting CD4 T cells (Fig. (Fig.8B),8B), cannot rescue the inhibitory effect of IFN-α (Fig. (Fig.8A,8A, lanes 9 and 11), it is unlikely that PKR or RNase L, which are also members of the IFN-α-induced signaling pathway, mediate the antiviral activity of IFN-α in resting CD4 T cells. We have also exploited the anti-HIV-1 activity of IFN-α in resting CD4 T cells with wild-type viruses. As shown in Fig. 8C and D, IFN-α, even if only incubated with infected resting T cells for the first 24 to 96 h and then completely removed, significantly inhibits the viral replication while the cells are in activating status, indicating that IFN-α inactivates a significant amount of viruses which are at their preintegration stage. As a control, IFN-α that has been incubated with activated T cells at the same dose for the first 72 h does not exert such a significant inhibitory effect upon HIV-1 replication (Fig. (Fig.8C).8C). Similar to what was seen with the single-round infection assay, APOBEC3G-specific siRNA can also significantly reduce the inhibitory effect of IFN-α upon wild-type HIV-1 replication (Fig. (Fig.8D).8D). This result also suggests that IFN-α could inhibit viral infectivity through enhancing the expression of APOBEC3G. Of note, transfection with APOBEC3G-specific siRNA or luciferase-specific siRNA did not increase the expression of CD25 and CD69 on the surface of resting CD4 T cells (Fig. (Fig.1D),1D), indicating that these treatments do not affect the resting status of primary CD4 T cells. To investigate whether the DNA deamination activity of APOBEC3G is involved in the IFN-α-induced anti-HIV-1 activity in resting CD4 T cells, we examined 59 viral sequences (32,450 total nucleotides in env or 3′ LTR region) of PCR products generated from the infected cells at 14 days postinfection. We also examined 46 viral sequences (25,300 total nucleotides) generated from the newly synthesized viral DNA at 48 h postinfection. These infected cells were initially treated with IFN-α but without any siRNA, followed by mitogen stimulation (Fig. (Fig.8C).8C). No significant G-to-A hypermutation has been identified in these sequences (data not shown). Therefore, it is unlikely that APOBEC3G-induced deamination in nascent viral DNA plays a major role in this antiviral activity of the IFN-α/APOBEC3G pathway.

DISCUSSION

The innate immunity is imperative during the early phase of host defense against various infections before an antigen-specific adaptive immune response is induced. Given that the majority of CD4 T cells in vivo are in a resting stage, APOBEC3G could function as a highly effective barrier to prevent extensive replication of HIV-1 and subsequently restrict its massive cytopathic effect on CD4 T cells. Unfortunately, this barrier is not yet reliable enough. It has been known that in cell cultures, HIV-1 could initially infect resting primary CD4 T cells and stay in a preintegration latency condition. Work from Greene's lab has indicated that APOBEC3G may play a major role in restricting HIV-1 replication in resting CD4 T cells (5). It seems that APOBEC3G, at its native concentrations in resting CD4 T cells, only transiently blocks the reverse transcription of HIV-1 and cannot completely eradicate the viruses, resulting in a preintegration latency. When resting CD4 cells are activated, a large amount of these viruses continue to complete their life cycle and generate progeny viruses, indicating that APOBEC3G in resting CD4 T cells could just transiently block reverse transcription and viral replication. Our data have demonstrated that IFN-α is able to enhance the anti-HIV-1 activity of APOBEC3G by increasing its concentration and keeping its association with an LMM. As very few or no viruses can be recovered after activation of the infected CD4 T cells (Fig. 8A and C to D), IFN-α-enhanced APOBEC3G can significantly inhibit reverse transcription and irreversibly inactivate HIV-1 viruses in the preintegration stage. This effect is in contrast to the transient restriction mediated by APOBEC3G at its normal concentration. These differences are of great in vivo relevance. HIV-1 could infect resting CD4 T cells and then be restricted by basic APOBEC3G in vivo. However, the infected resting CD4 T cells could be activated by antigen or cytokine stimulation at any moment. Upon activation, APOBEC3G will be associated with a high molecular mass rather than an LMM, and its inhibitory effect upon HIV-1 could be decreased. Therefore, the viruses blocked at the preintegration stage will continue their life cycle. However, if the IFN-α/APOBEC3G pathway is activated in resting CD4 T cells, the viruses blocked at the preintegration period will be inactivated and no live viruses will be produced upon activation. In summary, our work has demonstrated that interferon, a well-known antiviral innate immunity system, can potently regulate the expression and distribution of APOBEC3G in CD4 T cells. Similar results have been reported for macrophages and hepatocytes (21, 30). Therefore, the connection between two important antiviral innate immunity systems, the interferon system and APOBEC3G and its family members, has been identified.

We have simultaneously examined the pattern of the APOBEC3G-associated complex in the activated cells treated with IFN-α, along with several other treatments. As shown in Fig. Fig.5,5, the majority of APOBEC3G is associated with an LMM in the activated CD4 T cells treated with IFN-α. It should be emphasized, however, that the total concentration of APOBEC3G in the activated CD4 T cells is significantly decreased by IFN-α (Fig. (Fig.1).1). Therefore, the antiviral effect of LMM-associated APOBEC3G could be quite limited in the activated CD4 T cells. Conversely, as APOBEC3G has already been associated with an LMM in activated CD4 T cells treated with IFN-α, the poor replication of HIV-1 in the activated phase of CD4 T cells which are initially treated with IFN-α at their resting phase could not be due to the possible “locked” LMM-associated APOBEC3G which occurs during the resting stage of cells. Instead, it is more likely due to the fact that the viral infectivity is significantly inactivated in the resting stage by the treatment of IFN-α. The single-round infection experiments with a reporter gene and intracellular reverse transcription have further supported this hypothesis (Fig. (Fig.7B7B and and8A).8A). Furthermore, the inhibitory effect of IFN-α delivered transiently or continuously to the activated CD4 T cells upon HIV-1 replication is much less than the inhibitory effect of IFN-α delivered transiently to the initially quiescent CD4 T cells upon HIV-1 replication (Fig. (Fig.8C),8C), which also supports this hypothesis.

Previous studies have already demonstrated that IFN-α has anti-HIV-1 activity for which several mechanisms have been proposed. It can inhibit the process of reverse transcription at an early stage, restrict the generation of viral particles but not viral proteins in chronically infected cells, down-regulate viral protein synthesis, or suppress the HIV-1 LTR promoter (6, 23, 26, 32). It is noteworthy that the addition of IFN-α into cell cultures of resting primary T lymphocytes before mitogen stimulation could have a much stronger inhibitory effect on reverse transcription (26), which is consistent with our observations (Fig. 8A and D). Moreover, IFN-α has been used in clinical trials to treat HIV-1-infected individuals. However, findings from early clinical trials in the pre-highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) era have shown that IFN-α plus reverse transcriptase inhibitor(s) is effective but unable to completely control HIV-1 replication (1). It should be emphasized, however, that HIV-1 extensively replicates in the replicating CD4 T cells and quickly kills them in the pre-HAART era. As IFN-α does not enhance the concentration of APOBEC3G in replicating CD4 T cells, APOBEC3G could not play a leading role for IFN-α to restrict HIV-1 replication in replicating CD4 T cells. In this report, we have demonstrated that APOBEC3G is IFN-α inducible and makes important contributions for the anti-HIV-1 activity of IFN-α in resting CD4 T cells. As APOBEC3G potently inhibits the reverse transcription of HIV-1 in resting T lymphocytes, IFN-enhanced APOBEC3G expression could mediate the potent inhibitory effect upon reverse transcription by IFN-α. Importantly, because the inactivation of HIV-1 in resting CD4 T cells by the IFN-α/APOBEC3G pathway is so remarkable, it could lead to a novel therapeutic strategy for IFN-α to treat HIV-1-infected individuals. Intriguingly, a very preliminary study has shown that IFN-α in combination with HAART could be more effective in decreasing viral RNA in blood plasma and PBMC-associated viral RNA and DNA than HAART alone (10).

It is notable that the concentrations of IFN-α observed in these experiments are relatively high compared to the concentrations in the blood plasma of individuals administrated IFN-α (24). However, these experiments are “proof-of-concept” experiments. In the coming experiments, we are going to investigate the effect of IFN-α at “realistic” concentrations upon intracellular APOBEC3G and anti-HIV-1 activity. As the first step of a series of in vivo experiments, it is interesting to investigate whether IFN-α which is administrated with a regular dose could enhance the expression of APOBEC3G in resting CD4 T cells.

In the post-HAART era, the replication of HIV-1 in replicating CD4 T cells is significantly prevented. Latent HIV-1 infection is the major obstacle in eradicating residual HIV-1 viruses. It has been demonstrated that resting CD4 T cells are the major reservoirs for HIV-1 viruses. HIV-1 may maintain latency in these cells by postintegration latency in the memory CD4 T cells or by a “cryptic” low-level replication (12, 22, 41). There have been many attempts to eradicate residual HIV-1. It is likely that APOBEC3G at its normal concentration in resting CD4 T cells cannot block this replication. Based on our findings, we propose to prevent residual HIV-1 replication by strengthening APOBEC3G-mediated intracellular innate immunity. If IFN-α is regularly administrated, or alternatively, secreted by interferon-producing cells (28) stimulated with certain cytokines, up-regulation of APOBEC3G in resting CD4 T cells could block HIV-1 viruses to complete the “cryptic” low-level replication or abort the established latency, at least the preintegration latency. Our finding could start a “new thinking” to reevaluate IFN-α in HIV/AIDS clinics, especially when we do not have any other reliable way to control the “cryptic” replication at present.

Acknowledgments

We obtained the anti-APOBEC3G antibody, which was contributed by ImmunoDiagnostics, Inc., from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program. We thank Elias Argyris for his critical comments on the manuscript and Jennifer Rosa for proofreading.

This investigation was supported by NIH grants (AI047720, AI058798, and AI052732) to H.Z.

REFERENCES

Articles from Journal of Virology are provided here courtesy of American Society for Microbiology (ASM)

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.00206-06

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc1563726?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

The Intricate Interplay between APOBEC3 Proteins and DNA Tumour Viruses.

Pathogens, 13(3):187, 20 Feb 2024

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 38535531 | PMCID: PMC10974850

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

The initial interplay between HIV and mucosal innate immunity.

Front Immunol, 14:1104423, 30 Jan 2023

Cited by: 11 articles | PMID: 36798134 | PMCID: PMC9927018

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Viral Coinfections.

Viruses, 14(12):2645, 26 Nov 2022

Cited by: 8 articles | PMID: 36560647 | PMCID: PMC9784482

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Differential Inhibition of HIV Replication by the 12 Interferon Alpha Subtypes.

J Virol, 95(15):e0231120, 12 Jul 2021

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 33980591 | PMCID: PMC8274621

The interferon-stimulated exosomal hACE2 potently inhibits SARS-CoV-2 replication through competitively blocking the virus entry.

Signal Transduct Target Ther, 6(1):189, 12 May 2021

Cited by: 24 articles | PMID: 33980808 | PMCID: PMC8113286

Go to all (105) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Cellular APOBEC3G restricts HIV-1 infection in resting CD4+ T cells.

Nature, 435(7038):108-114, 13 Apr 2005

Cited by: 324 articles | PMID: 15829920

Induction of APOBEC3 family proteins, a defensive maneuver underlying interferon-induced anti-HIV-1 activity.

J Exp Med, 203(1):41-46, 17 Jan 2006

Cited by: 211 articles | PMID: 16418394 | PMCID: PMC2118075

IFN-α induces APOBEC3G, F, and A in immature dendritic cells and limits HIV-1 spread to CD4+ T cells.

J Immunol, 190(7):3346-3353, 20 Feb 2013

Cited by: 31 articles | PMID: 23427247

APOBEC deaminases as cellular antiviral factors: a novel natural host defense mechanism.

Med Sci Monit, 12(5):RA92-8, 01 May 2006

Cited by: 12 articles | PMID: 16641889

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NIAID NIH HHS (7)

Grant ID: R21 AI047720

Grant ID: R01 AI052732

Grant ID: AI 047720

Grant ID: R01 AI047720

Grant ID: R01 AI058798

Grant ID: AI 052732

Grant ID: AI 058798