Abstract

Free full text

The properties of high-dimensional data spaces: implications for exploring gene and protein expression data

Abstract

High-throughput genomic and proteomic technologies are widely used in cancer research to build better predictive models of diagnosis, prognosis and therapy, to identify and characterize key signalling networks and to find new targets for drug development. These technologies present investigators with the task of extracting meaningful statistical and biological information from high-dimensional data spaces, wherein each sample is defined by hundreds or thousands of measurements, usually concurrently obtained. The properties of high dimensionality are often poorly understood or overlooked in data modelling and analysis. From the perspective of translational science, this Review discusses the properties of high-dimensional data spaces that arise in genomic and proteomic studies and the challenges they can pose for data analysis and interpretation.

Genomic microarray and proteomic technologies provide powerful methods with which systems biology can be used to address important issues in cancer biology. These technologies are often used to identify genes and proteins that may have a functional role in specific phenotypes. It is becoming possible to define expression patterns that can identify specific phenotypes (diagnosis)1,2, establish a patient’s expected clinical outcome independent of treatment (prognosis)3,4 and predict a potential outcome from the effects of a specific therapy (prediction)5,6 (BOX 1). One recent example is the MammaPrint prognostic gene-expression signature, the first multivariate in vitro diagnostic assay approved for use by the US Food and Drug Administration. The gene set is based on the Amsterdam 70-Gene Profile, derived from the analysis of 25,000 human genes in a series of 98 primary breast cancers7. Subsequently, the signature (or classifier) was verified in an independent series of 295 breast cancers8. Activity levels of the genes in the signature are translated into a score that is used to classify patients into those at high risk and those at low risk of recurrent disease, thereby informing decisions on treatment strategy to deliver appropriate treatment according to each patient’s risk classification7. MammaPrint is applicable for patients diagnosed with node-negative, stage I or stage II breast cancer, demonstrating a place for molecular-based technologies in modern medicine.

Despite the encouraging progress of the MammaPrint classifier, the application of modern systems-biology techniques has introduced into cancer research the problems of working in high-dimensional data spaces, wherein each sample can be defined by hundreds or thousands of measurements. Gene microarray analysis of a single cancer specimen could yield concurrent measurements on >10,000 detectable mRNA transcripts. Even after a simple pair-wise analysis to select differentially expressed genes in a supervised analysis (see discussion of supervised analysis below), for example, using t-test or false discovery rate (FDR) methodology, the data structure may still contain information on >1,500 genes per sample in a study with a small sample size9 (BOX 2). Dimensionality may be much larger in proteomic studies10. Although often encountered in other fields, such as engineering and computer science, this data structure is unlike most others in biomedicine. Our goal in this Review is not to provide a guide to data analysis, as this has been done by others11,12. Rather, we discuss the theory and properties of these data spaces and highlight how they may affect data analysis and interpretation. We also describe the basic properties of high-dimensional data structures and discuss the challenges these pose for extracting accurate, reliable and optimal knowledge.

We consider data structure from several perspectives. In the simplest sense, these data represent a direct or indirect assessment of the levels of expression of 100s to 10,000s of mRNA transcripts or proteins. These values reside in space characterized by multiple additional properties, as the space is also defined by the biological properties of the specimens from which they were obtained, by the functional interactions among co-expressed genes or proteins in signalling networks, and by the experimental design. Each of these factors can affect data structure and the ability to analyse it effectively. We begin by discussing key aspects of data spaces that affect many experimental designs. We then describe the properties of high-dimensional data spaces and how they affect the derivation of meaningful information from the data.

Basic transcriptome or proteome data structure

Data points can be seen from the perspective of either the samples or the individual genes or proteins. Viewed from the perspective of the samples, each sample exists in the number of dimensions defined by the number of gene or protein signals that are measured. This is a common perspective in cancer classification, patient survival analysis, identification of significantly expressed genes and other studies in which patients or samples are treated as observations and genes or proteins are treated as variables. These data structures are the primary focus of this Review. By contrast, studies in which genes or proteins are treated as observations and samples or patients are treated as variables, such as in gene function prediction13,14, face low-dimensional challenges because there may be insufficient observations (genes or proteins) in specific gene function classes for a supervised classification.

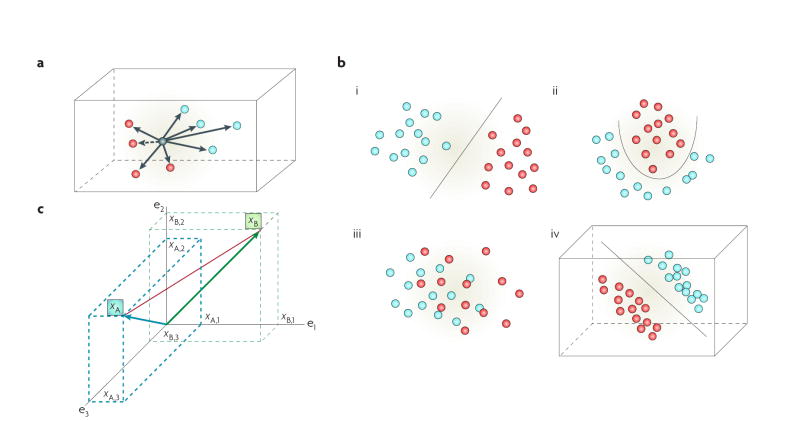

Transcriptome and proteome data comprise a mixture of discrete categories (clusters), each category defining a specific class. Clusters are subgroups of data that are more like each other than like any other subgroup of data, and are scattered throughout high-dimensional data spaces (FIG. 1a,b). Each class can be defined by the goal of the experiment, which might be a phenotype (such as recurrent or non-recurrent), a response (responder or non-responder), a treatment (treated, untreated or specific dose), a timed event (time points in a longitudinal study) or some other measure. A class can be represented by more than one cluster. Expression data are massively parallel (FIG. 2) and represent a snapshot of the state of the transcriptome or proteome at the time the specimen was collected. However, some biological functions proceed in a stepwise fashion and these may be inadequately captured in a snapshot. Regulation of expression of some genes is multifactorial, with the key regulatory determinants differing among cell and tissue types and, indeed, among individuals. Some genes can perform different functions in different cells, and different genes can perform more or less the same function in the same cell15. Hence, the activity of some genes is cell context-dependent; the cellular context is defined by the patterns of gene or protein expression and activation within a cell16. This biological complexity, where function can be influenced by concurrent, sequential, redundant, degenerate, interdependent or independent events15, complicates the ability to fully discover the information contained within high-dimensional data.

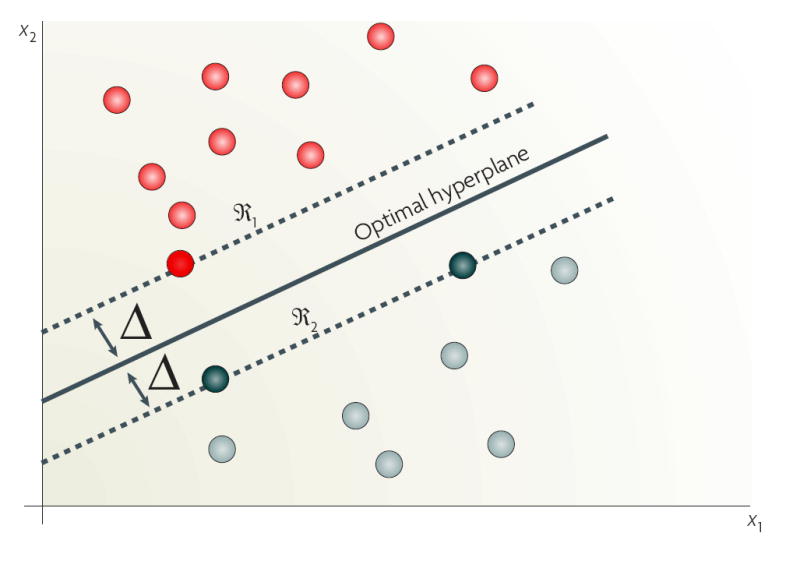

a | Each data point exists in the space defined by its attributes and by its relative distance to all other data points. The nearest neighbour (dashed arrow) is the closest data point. The goal of clustering algorithms is to assign the data point to membership in the most appropriate cluster (red or blue cluster). Many widely used analysis methods force samples to belong to a single group or link them to their estimated nearest neighbour and do not allow concurrent membership of more than one area of data space (hard clustering; such as k-means clustering or hierarchical clustering based on a distance matrix). Analysis methods that allow samples to belong to more than one cluster (soft clustering; such as that using the expectation-maximization algorithm) may reveal additional information. b | Data classes can be linearly separable or non-linearly separable. When linearly separable, a linear plane can be found that separates the data clusters (i). Non-linearly separable data can exist in relatively simple (ii) or complex (iii) data space. Well-defined clusters in simple data space may be separated by a non-linear plane (ii). In complex data space, cluster separability may not be apparent in low-dimensional visualizations (iii), but may exist in higher dimensions (iv). c | Expression data can be represented as collections of continuously valued vectors, each corresponding to a sample’s gene-expression profile. Data are often arranged in a matrix of N rows (samples) and D columns (variables or genes). The distance of a data point to the origin (vector space), or the distance between two data points (metric space), is defined by general mathematical rules. A (blue arrow) and B (green arrow) are vectors and their Euclidean distance is indicated by the red line. Individual data points, each represented by a vector, can form clusters, as in the examples of two clusters in b.

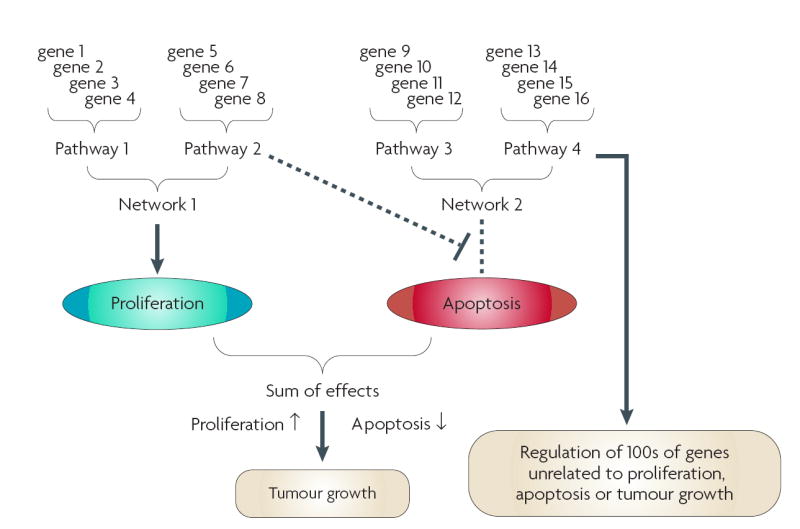

Most univariate and multivariate probability theories were derived for data space where N (number of samples) > D (number of dimensions). Expression data are usually very different (D>>>N). A study of 100 mRNA populations (one from each of 100 tumours) arrayed against 10,000 genes can be viewed as each of the 100 tumours existing in 10,000-D space. This data structure is the inverse of an epidemiological study of 10,000 subjects (samples) for which there are data from 100 measurements (dimensions), yet both data sets contain 106 data points. A further concern arises from the multimodal nature of high-dimensional data spaces. The dynamic nature of cancer and the concurrent activity of multiple biological processes occurring within the microenvironment of a tumour create a multimodal data set. Genes combine into pathways; pathways combine into networks. Genes, pathways and/or networks interact to affect subphenotypes (proliferation, apoptosis); subphenotypes contribute to clinically relevant observations (tumour size, proliferation rate). Genes in pathway 2 are directly associated with a network (and with pathway 1) and a common subphenotype (increased proliferation). Genes in pathway 2 are also inversely associated with a subphenotype (apoptosis). Here, multimodality captures the complex redundancy and degeneracy of biological systems15 and the concurrent expression of multiple components of a complex phenotype. For example, tumour growth reflects the balance between cell survival, proliferation and death, and cell loss from the tumour (such as through invasion and metastasis), each being regulated by a series of cellular signals and functions. Many such complex functions may coexist, such as growth-factor or hormonal stimulation of tumour cell survival or proliferation, or the ability to regulate a specific cell-death cascade. A molecular profile from a tumour may contain subpatterns of genes that reflect each of these individual characteristics. This multimodality may be problematic for statistical modelling to build either accurate cell signalling networks or robust classification schemes.

Most common approaches to exploring entire expression profiles use some measure of distance within Euclidean space (mathematical geometric model) as a means to establish the relationship among data points (FIG. 1c). For example, the numerator in a t-test equation uses the Euclidean distance between the means of the two populations. A k-means clustering algorithm uses various Euclidean distances to measure the distance from a data point to the estimated median of a cluster. A support vector machine (SVM; BOX 3) measures the distance of a data point or pattern from the boundary between the two populations in Euclidean space. A common method is hard clustering using a Pearson correlation matrix to construct a hierarchical representation of the data17, used, for example, to discover five new molecular subclasses of breast cancer18. The k-nearest neighbour (kNN) decision rule assigns similar patterns to the same class and requires computation of the distance between a test pattern and all the patterns in the training set19. The number of neighbourhoods, k, is set by the user. If k = 1, the test pattern is then assigned to the class of the closest training pattern19. For k = 3, 5, 7… the majority vote is applied based on the assumption that the characteristics of members of the same class are similar. A kNN approach was used in a recent study to define molecular subclasses of childhood acute leukaemias20.

Supervised and unsupervised analyses

Among the most common experimental designs are those aimed at finding molecular profiles that establish a patient’s prognosis, or identify those signalling events that drive a specific biological property of a cancer cell line, mouse model, therapy or other manipulation (for examples, see REFS 6,21,22). Studies in which the endpoint measurements that are associated with the respective expression pattern(s) are known (that is, there is external information that can be used to guide and evaluate the process) are termed supervised analyses; these generally have the greatest power to correctly identify important molecular changes. For example, when one group of samples (class 1: sensitive to a cytotoxic drug) is compared with another (class 2: resistant to a cytotoxic drug), the external knowledge is the class membership of the samples under analysis. The analysis can proceed to find genes or proteins that are differentially expressed between the two classes. These genetic or proteomic profiles can then be used to build a classifier to predict whether unknown samples belong to class 1 or class 2; that is, the classifier is trained on a series of samples for which class membership is known and then validated on an independent data set. An independent data set is one for which class membership is known but the data are not from the samples used to identify the profile or train the classifier. This approach allows the accuracy of the classifier to be determined without the outcome being biased by using the same input data used to build or train the predictor (FIG. 3). Supervised analysis can be used for many aspects of high-dimensional data analysis, including dimensionality reduction, feature selection and predictive classification.

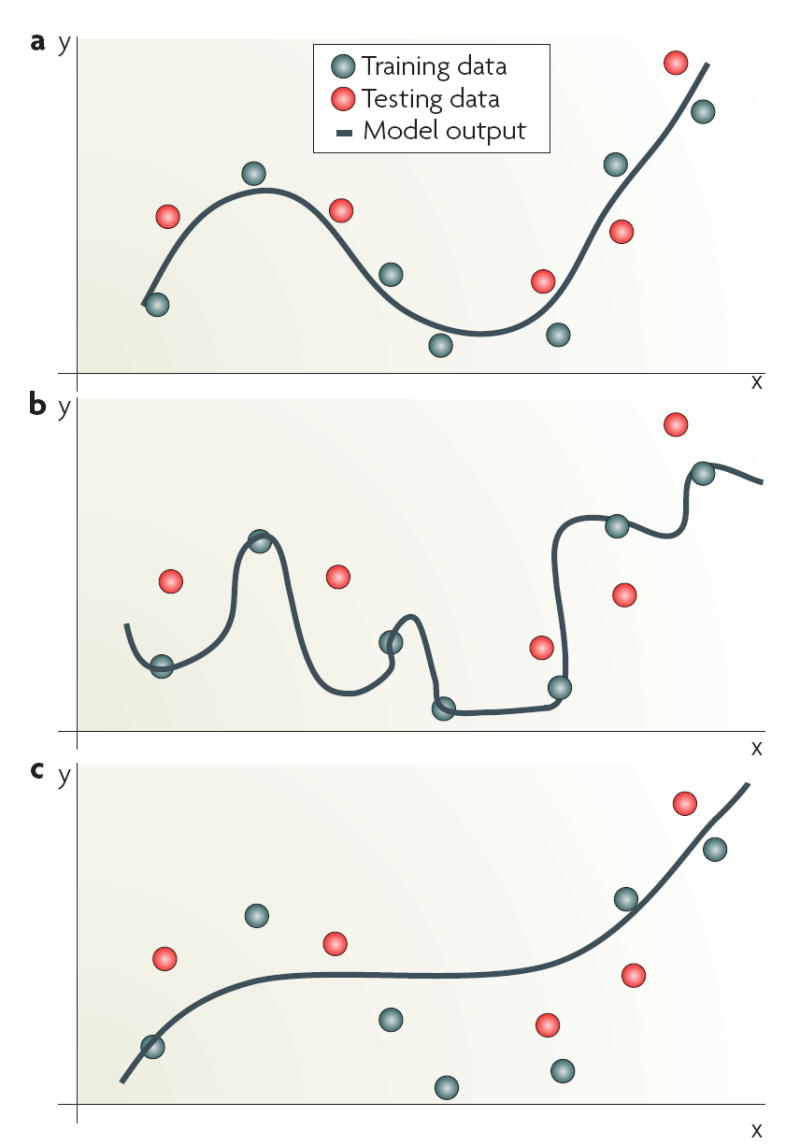

a | Output of a smooth function that yields good generalization on previously unseen inputs. b | A model that performs well on the training data used for model building, but fails to generalize on independent data and is hence overfitted to the training data. c | A model that is insufficiently constructed and trained and is considered to be underfitted. The imposition of stability on the solution can reduce overfitting by ensuring that the function is smooth, and some random fluctuations are well-controlled in high-dimensions46. This allows new samples that are similar to those in the training set to be similarly labelled. This phenomenon is often referred to as the ‘blessing of smoothness’. Stability can also be imposed using regularization that ensures smoothness by constraining the magnitude of the parameters of the model. Support vector machines apply a regularization term that controls the model complexity and makes it less likely to overfit the data (BOX 3). By contrast, k-nearest neighbour or weighted voting average algorithms overcome the challenge simply by reducing data dimensionality. Validation of performance is a crucial component in model building. Although an iterative sequential training is often used for both training and optimization114, validation must be done using an independent data set (not used for model training or optimization) and where there are adequate outcomes relative to the number of variables in the model39. For early proof-of-principle studies, for which an independent data set may not be available, some form of cross-validation can be used. For example, three-fold cross-validation is common, in which the classifier is trained on two-thirds of the overall data set and tested for predictive power on the other third36,115,116. This process is repeated multiple times by reshuffling the data and re-testing the classification error.

Unsupervised cluster analyses are an important tool for discovering underlying cancer subtypes or gene modules23,24 and can also be applied when information for supervised analyses is available to suggest refinements of known cancer categories: categorical labels are purposely withheld or used to initiate a clustering algorithm25 (FIG. 1). Class labels can subsequently be used to validate the clustering methodology and assumptions, where strong correlations among clustering outcomes and known class labels support the applicability of this clustering approach to other unlabelled microarray data23. The study by Golub et al.23 of acute myeloid leukaemia and acute lymphoblastic leukaemia is one example of the use of unsupervised analysis on data from samples with known histopathological subtypes (supervised data).

Applying unsupervised methods to data with known categorical information might seem counterintuitive. However, an important consideration is the quality of the known categorical information, as the extent to which data membership is defined by existing information might be incomplete. Consider a study of the anthracycline anticancer drug doxorubicin with two goals: the first to identify the mechanism of doxorubicin action and resistance, and the second to build a clinically meaningful predictor of doxorubicin responsiveness. For the first goal (molecular signalling), a common assumption is that all tumours will respond to doxorubicin in the same way. However, data may not be fully defined by the binary outcomes (supervision) of sensitivity and resistance. For example, doxorubicin can both produce chemically reactive metabolites that damage nucleic acids and proteins (mechanism 1) and inhibit topoisomerase II, an enzyme involved in maintaining DNA topology (mechanism 2)26,27. If doxorubicin can kill cells through either mechanism, some tumours may be more sensitive to one mechanism than to the other. If only one responsive phenotype is assumed but both occur, a supervised analysis comparing all sensitive with all resistant tumours could fail to identify, either correctly and/or completely, consistent changes in gene expression that would identify either pathway.

An effective unsupervised analysis might allow the discovery of several molecular signatures associated with doxorubicin responsiveness. Information that defines outcome (sensitive versus resistant) could be used to assess the accuracy of the unsupervised clustering solution. Some of the clusters found might contain a high proportion of doxorubicin-sensitive tumours (clusters representing sensitivity to mechanisms 1, 2 and/or unknown mechanisms) whereas other clusters may contain mostly resistant tumours (resistant to mechanisms 1, 2 and/or unknown mechanisms).

To construct a classifier of prediction in a supervised analysis, the supervising information may be a measure of clinical response used as a surrogate for a long-term outcome such as survival. The choice of surrogate endpoint then becomes a crucial component of how to define and test a classifier of responsiveness. If the study applies a neoadjuvant design, the surrogate of palpable tumour shrinkage (clinical response) may be suboptimal compared with pathological response. A complete pathological response is usually a better predictor of survival outcome because microscopic disease rather than tumour shrinkage is evaluated28-30. When the pathological data are not available, an unsupervised method may help find those complete clinical responses that are not true complete pathological responses: hence, two subclusters might be identified within the group defined as complete clinical responses. These simple examples emphasize the importance of the hypothesis and the experimental design, and how these can affect the approach to data analysis.

Properties of high-dimensional data spaces

The properties of high-dimensional data can affect the ability of statistical models to extract meaningful information. For genomic and proteomic studies, these properties reflect both the statistical and mathematical properties of high-dimensional data spaces and the consequences of the measured values arising from the complexity of cancer biology. This section discusses such issues and their implications.

The curse of dimensionality

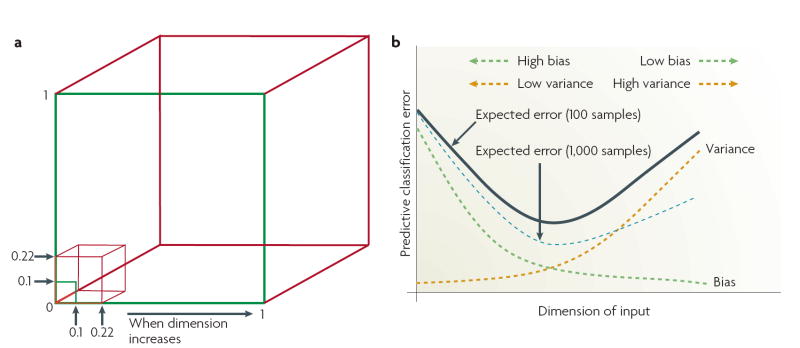

The performance of a statistical model depends on the interrelationship among sample size, data dimensionality, model complexity19 and the variability of outcome measures. Optimal model fitting using statistical learning techniques breaks down in high dimensions, a phenomenon called the ‘curse of dimensionality’31. FIGURE 4 illustrates the effects of dimensionality on the geometric distribution of data and introduces the performance behaviour of statistical models that concurrently use a large number of input variables. For example, a naive learning technique (dividing the attribute space into cells and associating a class label with each cell) requires the number of training data points to be an exponential function of the attribute dimension19. Thus, the ability of an algorithm to converge to a true model degrades rapidly as data dimensionality increases32.

a | The geometric distributions of data points in low- and high-dimensional space differ significantly. For example, using a subcubical neighbourhood in a 3-dimensional data space (red cube) to capture 1% of the data to learn a local model requires coverage of 22% of the range of each dimension (0.01 ≈ 0.223) as compared with only 10% coverage in a 2-dimensional data space (green square) (0.01 = 0.102). Accordingly, using a hypercubical neighbourhood in a 10-dimensional data space to capture 1% of the data to learn a local model requires coverage of as much as 63% of the range of each dimension (0.01 ≈ 0.6310). Such neighbourhoods are no longer ‘local’111. As a result, the sparse sampling in high dimensions creates the empty space phenomenon: most data points are closer to the surface of the sample space than to any other data point111. For example, with 5,000 data points uniformly distributed in a 10-dimensional unit ball centred at the origin, the median distance from the origin to the nearest data point is approximately 0.52 (more than halfway to the boundary), that is, a nearest-neighbour estimate at the origin must be extrapolated or interpolated from neighbouring sample points that are effectively far away from the origin111. b | A practical demonstration is the bias–variance dilemma36,111,115. Specifically, the mismatch between a model and data can be decomposed into two components; bias that represents the approximation error, and variance that represents the estimation error. Added dimensions can degrade the performance of a model if the number of training samples is small relative to the number of dimensions. For a fixed sample size, as the number of dimensions is increased there is a corresponding increase in model complexity (increase in the number of unknown parameters), and a decrease in the reliability of the parameter estimates. Consequently, in the high-dimensional data space there is a trade-off between the decreased predictor bias and the increased prediction uncertainty36,111.

The application of statistical pattern recognition to molecular profiling data is complicated by the distortion of data structure. For many neural network classifiers, learning is confounded by the input of high-dimensional data and the consequent large search radius — the network must allocate its resources to represent many irrelevant components of this input space (data attributes that do not contribute to the solution of data structure). When confronted with an input of 1,500 dimensions (D), much of the data space will probably contain irrelevant data subspaces unevenly distributed within the data space33. Supervised or unsupervised algorithms can fail when attempting to find the true relationships among individual data points for each sample and among different groups of similar data32. Thus, the data solution obtained may be incorrect, incomplete or suboptimal.

Because of the high dimensionality of the input data, arriving at an adequate or correct solution will generally be computationally intensive. Although simple models, such as some hierarchical clustering approaches, may not be computationally affected, these are often inappropriate for tasks other than visualization11,34. Simple models can perform well when the structure of the data is relatively simple, for example, a small number of well-defined clusters35, but may be less effective for complex data sets. A further challenge for modelling is to avoid overfitting the training data (FIG. 3b). Clearly, it is necessary to have methods that can produce models with good generalization capability. Models derived from a training data set are expected to apply equally well to an independent data set. FIGURE 3 illustrates the effects of overfitting and underfitting and the need for smoothness regularization in a curve-fitting problem36.

The often small number of sample replicates further compounds the problems of multimodal, high-dimensional data spaces. The number of replicate estimates of each sample is usually limited; often only a single measurement is obtained37. Moreover, the number of data features may be so large that an adequate number of samples cannot be obtained for accurate analysis. For example, logistic regression modelling is widely used to relate one or more explanatory variables (such as a cancer biomarker) to a dependent outcome (such as recurrence status) with a binomial distribution. However, the ability to model high-dimensional data accurately and robustly is restricted by the ‘rule of 10’ (REF. 38); Peduzzi et al.39 showed that regression coefficients can be biased in both directions (positive and negative) when the number of events per variable falls below 10. For example, a logistic regression model relating the expression of 50 genes (variables) to a binary clinical outcome such as doxorubicin responsiveness, for which the response rate was approximately 25%, might require a study population of 2,000 to obtain 500 responders (10 times the number of genes as required by the rule of 10 and 25% of the study population) and 1,500 non-responders.

Two of the more common approaches to addressing the properties of high dimensionality are reducing the dimensionality of the data set (FIG. 5) or applying or adapting methods that are independent of data dimensionality. For classification schemes, SvMs are specifically designed to operate in high-dimensional spaces and are less subject to the curse of dimensionality than other classifiers (BOX 3).

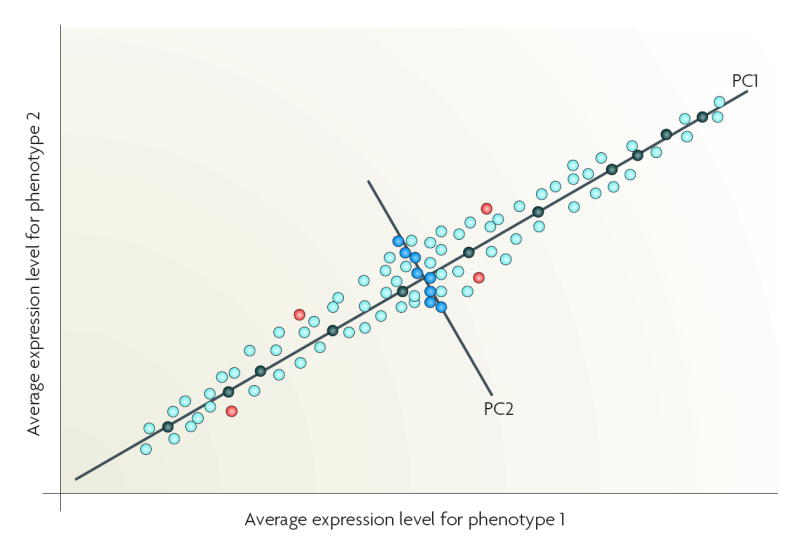

A practical implication of the curse of dimensionality is that, when confronted with a limited training sample, an investigator will select a small number of informative features (variables or genes). A supervised method can select these features (reduce dimensionality), where the most useful subset of features (genes or proteins) is selected on the basis of the classification performance of the features. The crucial issue is the choice of a criterion function. Commonly used criteria are the classification error and joint likelihood of a gene subset, but such criteria cannot be reliably estimated when data dimensionality is high. One strategy is to apply bootstrap re-sampling to improve the reliability of the model parameter estimates. Most approaches use relatively simple criterion functions to control the magnitude of the estimation variance. An ensemble approach can be derived, as multiple algorithms can be applied to the same data with embedded multiple runs (different initializations, parameter settings) using bootstrap samples and leave-one-out cross-validation. Stability analysis can then be used to assess and select the converged solutions114. Unsupervised methods such as principal component analysis (PCA) can transform the original features into new features (principal components (PC)), each PC representing a linear combination of the original features117. PCA reduces input dimensionality by providing a subset of components that captures most of the information in the original data118. For example, those genes that are highly correlated with the most informative PCs could be selected as classifier inputs, rather than a large dimension of original variables containing redundant features119,120. Non-linear PCA, such as kernel PCA can also be used for dimensionality reduction but adds the capability, through kernel-based feature spaces, to look for non-linear combinations of the input variables36. PCA is useful for classification studies but is potentially problematic for molecular signalling studies. If PC1 is used to identify genes that are differentially expressed between phenotypes 1 and 2, then genes that are strongly associated with PC1 (black circles) would be selected. If both PC1 and PC2 are used, then genes strongly associated with PC1 (black circles) and PC2 (blue circles) would be selected. Some genes could be differentially expressed but weakly associated with the top two PCs (PC1, PC2) and so not selected (red circles). As their rejection is not based on biological function(s), key mechanistic information could be lost.

Effect of high dimensionality on distance measures in Euclidean spaces

In many studies, investigators perform a similarity search of the data space that is effectively a nearest neighbour (distance) query in Euclidean space40. A similarity search might be used to build an agglomerative hierarchical representation of the data, in which data points are linked in a stepwise manner using their proximity, as measured by their respective Euclidean distance from each other17 (as was used in the molecular classification of breast cancers18). In a different context, similarity might be used to predict a biological outcome; the task is to find how similar (close) in gene or protein expression space is a sample of unknown phenotype to that of a known phenotype template. Use of the MammaPrint classifier to assess the prognosis of a patient with breast cancer is one example.

As dimensionality increases, the scalability of measures in Euclidean spaces is generally poor, and data can become uniformly distributed41,42. FIGURE 4 illustrates the effect of dimensionality on the geometric distribution of data and introduces the need for some statistical models to concurrently consider a large number of variables (curse of dimensionality). In the context of finding a nearest neighbour in Euclidean spaces, the distance to a point’s farthest neighbour approaches that of its nearest neighbour when D increases to as few as 15 (REF. 43); distances may eventually converge to become effectively equidistant. If all the data are close to each other (low variance in their respective distance measures), the variability of each data point’s measure (such as the variation in the estimate of a gene’s expression level) could render the search for its nearest neighbour, as a means to find the gene cluster to which it truly belongs, a venture fraught with uncertainty.

Beyer et al.43 suggest that this property may not apply to all data sets and all queries. When the data comprise a small number of well-defined clusters, a query within or near to such a cluster could return a meaningful answer43. It is not clear that all expression data sets exhibit such well-defined clusters, nor is it clear that there is consensus on how this property can be measured accurately and robustly. What does seem clear is that both dimensionality and data structure can affect distance measures in Euclidean space and the performance of a similarity search.

Concentration of measure

As discussed above, in high-dimensional data spaces, the probability that a function is concentrated around a single value, or the distance from a value to its expected mean or median value, approaches zero as the dimensionality increases. This phenomenon is usually referred to as the ‘concentration of measure’ and it was introduced by Milman to describe the distribution of probabilities in high dimensions44. A simple example of the concentration of measure in action is shown by considering the problem of missing value estimation. Missing values can arise from several sources, such as low-abundance genes (often those of most importance to signalling studies) that are frequently expressed at values near their limit of detection, leading to the appearance of missing values (below detection) within the same experimental group. A further source is the use of ‘Present Call’ and ‘Absent Call’ by Affymetrix, which can lead to apparent missing values when a gene in some specimens in an experimental group is called ‘present’ and in others ‘absent’.

Assuming that many signals on a microarray chip represent genes that have expression values equivalent to that of the missing gene, if we can identify enough of these signals on other chips from the same experimental group where the missing signal is present then we can use these signals to predict the value of the missing signal. The concentration of measure operates here when we can identify enough signals such that their expression values are located close to their true, common, underlying value. Because the assumption is based on the statistical properties of the expression values, the kNN interpolation can be applied45. Once identified, the characteristics of these expression values can be used to estimate both the missing value and its variance distribution, construct a normal (or other) distribution and obtain estimates for any comparable instance of the missing value. The accuracy of such methods may be affected by the property of the similarity of distances in high dimensions43.

Smoothness and roughness

The properties of smoothness or roughness usually refer to the relative presence or absence of consistency or variability in the data. Although global smoothness is a property of some high-dimensional data spaces46, data often exhibit both global roughness and local noise47. This variability in the data can be reduced by applying a normalization procedure; common methods include those based on linear regression through the origin, or lowess smoothing48-50. Such methods may affect both global roughness and local noise. Some normalization procedures change the data points from measured values to estimated values that are expected to more closely approximate truth. As data analysis is generally performed after such noise reduction and normalization, investigators should understand how normalization alters data structure and may affect the use of data-analysis tools or the interpretation of analysis outcomes (for a review see REF. 47). For example, some normalization methods can generate estimated values with errors that are no longer normally distributed, thereby making more complex the application of parametric statistical models.

Biology further characterizes data properties

In addition to the statistical properties of high-dimensional data spaces, measurements obtained from cancer specimens (cell lines, tumour tissue samples and so on) reflect the concurrent presence of complex signalling networks. A key goal of many studies is to derive knowledge of this signalling from within high-dimensional expression data. Two aspects of data structure that are notable in biological systems, and that affect our ability to extract meaningful knowledge, are the confound of multimodality (COMM) and the presence of strongly correlated data (both discussed below).

In addressing the experimental goals of either classification or signalling, we may only be able to measure grossly meaningful characteristics of the source tissue, such as tumour size, local invasiveness or proliferation index; these characteristics represent combinations of biological processes (multimodality). Often, only indirect biomarkers of these processes are available, such as measuring the proportion of tumour cells in S phase as an indicator of proliferation. If we now consider what an expression profile of 30,000 measured protein signals represents from a single specimen, we are faced with the knowledge that, for the study goals of class prediction and molecular signalling, this profile is associated with multiple and potentially interactive, interdependent and/or overlapping components (correlated structures). Thus, investigators must have sufficient insight to be able to determine which of the profile segments (signatures) are definitively associated with which component of a phenotype.

The confound of multimodality

We introduce the COMM here to express the problems that are associated with extracting truth from complex systems. Biological multimodality exists at many different levels (FIG. 2). COMM refers to the potential that the presence of multiple interrelated biological processes will obscure the true relationships between a gene or gene subset and a specific process or outcome, and/or create spurious relationships that may appear statistically or intuitively correct and yet may be false.

Multimodality can arise from several sources. Within a tumour, each subpopulation of cells will contribute to the overall molecular profile (tissue heterogeneity). Within each cell, multiple components of its phenotype coexist (cellular heterogeneity) and these can be driven by independent signalling networks. Individual genes may participate concurrently in more than one network, controlling or performing more than one process. In breast cancer, transforming growth factor β1 (TGFB1) is implicated in regulating proliferation and apoptosis16,51,52 and it is a key player in the regulation of bone resorption in osteolytic lesions in bone metastases53-55. TGFB1-regulated functions that affect bone resorption might or might not require the cell to be in a bone environment; these functions might be expressed in the primary tumour but only become relevant when other genes have enabled the cells to metastasize to bone. TGFB1 activity can also be modified by other factors. The hormone prolactin can block TGFB1-induced apoptosis in the mammary gland through a mechanism that involves the serine/threonine kinase Akt56; anti-oestrogens also affect TGFB1 expression57. Thus, the multimodal biological functions of TGFB1 (apoptosis, proliferation, bone resorption and other activities) may confound a simple, correct or complete interpretation of its likely function, particularly if the knowledge in one cellular context is used to interpret its function in different cell types, tissues or states.

Transcription factors can regulate the expression of many genes, and understanding the precise activity of a transcription factor could be difficult because not all of these genes may be functionally important in every cellular context in which the transcription factor is expressed, mutated or lost. For example, in response to tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα) stimulation, the transcription factor nuclear factor κB p65 (RELA) occupies over 200 unique binding sites on human chromosome22 (REF. 58). Amplification of the transcription factor oestrogen receptor α (ERα; encoded by ESR1) is a common event in breast cancers and benign lesions59 and ERα occupies over 3,500 unique sites in the human genome60. Hence, thousands of putative ERα-regulated genes have the potential to affect diverse cellular functions in a cell context-specific manner16,61. Conversely, loss of transcription factor activity, as can occur with mutation of p53, could leave many downstream signals deregulated62,63.

Tissue heterogeneity contributes further to multimodality. It is not unusual for a breast tumour to contain normal and neoplastic epithelial cells, adipocytes, and myoepithelial, fibroblastic, myofibroblastic and/or reticuloendothelial cells64. When total RNA or protein is extracted without prior microdissection, the resulting data for each gene or protein will represent the sum of signals from every cell type present. Here, the multimodality of each signal is conferred by the different cell types in the specimen. Furthermore, heterogeneity may also arise within the tumour cell population itself from the differentiation of cancer stem cells, the molecular profiles of which are the focus of considerable interest65.

Biological data are highly correlated

It is generally assumed that genes or proteins that act together in a pathway will exhibit strong correlations among their expression values, evident as gene clusters66. Such clusters might inform both a functional understanding of cancer cell biology and reveal patterns for diagnostic, prognostic or predictive classification. However, the performance of algorithms that find correlation patterns (also termed correlation structures) is affected by the nature and extent of those correlations present in the data. Biological interpretation of the correlation structures identified can be influenced by an understanding of how genes act in cancer biology to drive the phenotypes under investigation.

A common property of high-dimensional data spaces is the existence of non-trivial, highly correlated data points and/or data spaces or subspaces. The correlation structure of such data can exhibit both global and local correlation structures67,68. Several sources of correlation are evident and represent both statistical and biological correlations. A transcription factor may concurrently regulate key genes in multiple signal transduction pathways. As the expression of each downstream gene is expected to correlate with its regulating (upstream) transcription factor(s), key genes under the same regulation are biologically correlated and are likely to be statistically correlated. In gene network building, local correlation structures are crucial for identifying tightly correlated gene expression signals that are expected to reflect biological associations. However, the selection of differentially expressed genes creates a global correlation structure. In a pairwise comparison, all genes upregulated in one group share, to some degree, a common correlation with that group and also share an inverse correlation with the downregulated genes.

Biological heterogeneity can contribute to the correlation structure of the data and the overall molecular profile and its internal correlation structure may change over time. For example, a synchronization study in which all cells are initially in the same phase of the cell cycle may exhibit a loss of synchronicity over time as cells transit through subsequent cell cycles69. As a population of cancer stem cells begins to differentiate, the molecular profiles and their correlation structures should diverge as the daughter cells acquire functionally differentiated phenotypes70-72. In a neoadjuvant chemotherapy study, cell population remodelling may occur in a responsive tumour as sensitive cells die out.

The highly correlated nature of high throughput genomic and proteomic data also has deleterious effects on the performance of methods that assume an absence of correlation, including such widely used models as FDR for gene selection (BOX 2). Spurious correlations are a property of high-dimensional and noisy data sets67 and can be problematic for analytical approaches that seek to define a data set solely by its correlation structures. Although data normalization can remove both spurious and real correlations66, the application of different normalization procedures could result in different solutions to the same data.

Some general properties of correlation structures and subspaces in high-dimensional data have been described67,73. local properties of correlation structures include the small-world property74, where the average distance between data points, such as genes in a data subspace (perhaps reflecting a gene network), does not exceed a logarithm of the total system size75. Thus, the average distance is small compared with the overall size. Connectivity among data points, such as correlated genes in a network, may also exhibit scale-free behaviour76, at least in some relatively well-ordered systems77. Network modularity is a manifestation of scale-free network connectivity78,79.

Precisely how data subspaces can be grown to define overall data structure is unclear. Both exponential neighbourhood growth and growth according to a power law (fractal-like) have been described73. How these approaches can be applied to transcriptome and proteome data sets and affect the extraction of statistical correlations that represent meaningful biological interactions (as is the goal in building gene networks), and particularly in complex biological systems such as cancer, remains to be determined. Nonetheless, it is possible to exploit the differential dependencies or correlations using data from different conditions to extract the local networks80,81. More advanced predictor-based approaches can be used to identify interacting genes that are only marginally differentially expressed but that probably participate in the upstream regulation programmes because of their intensive non-linear interactions and joint effect82,83.

Implications of multimodality and correlation

Multimodality and correlation structures can complicate the analysis of biological data; confounding factors or variables often reflect biological multimodality and spurious correlations that can lead to incorrect biomarker selection84,85. For example, it is not difficult to separate (grossly) anti-oestrogen-sensitive from anti-oestrogen-resistant breast cancers by measuring the expression of only one or two genes. Breast tumours that do not express either ERα or progesterone receptors (PGR) rarely respond to an anti-oestrogen, whereas approximately 75% of tumours positive for both ERα and PGR will respond, indicating other factors are involved16,86. Although there are clear mechanistic reasons why ERα and PGR expression is associated with hormone responsiveness, this simple classification is also associated with other clinical outcomes. ERα+–PGR+ tumours tend to have a lower proliferative rate, exhibit a better differentiated cellular phenotype and have a better clinical outcome (prognosis) than ERα−–PGR− tumours87-89. Thus, it may be relatively straightforward to find a robust molecular profile that does not include ERα and PGR but that separates ERα+ and ERα− tumours. Less straightforward might be to separate each of the subgroups of ERα+−PGR+ tumours because of multimodality. This would require sorting all ERα+−PGR+ tumours into subgroups with a poor versus good prognosis, anti-oestrogen-sensitive versus anti-oestrogen-resistant, high versus low proliferative rate, or well versus poorly differentiated. The task is non-trivial because some tumours will be a member of more than one subgroup, and the information supervising each subgroup may not be adequate to support the correct solution of the data structure. The correlation structure can further complicate analysis as ERα+ tumours are correlated with both good prognosis and sensitivity to anti-oestrogens.

Applying external information to limit the subphenotypes with which a gene or gene subtype is functionally associated requires careful consideration as this can lead to the trap of self-fulfilling prophesy (a consequence of COMM). To be effective, the list of likely gene or protein functions should be known and correctly annotated90. The contribution of cellular context should also be known, as cell-type specificity and subcellular compartmentalization can determine function and activity. When considered with the potential for redundancy and degeneracy, the importance and complexity of cellular context in affecting cell signalling and the uncertainty of completeness of knowledge to support deduction imply that the risk of falling into the trap of self-fulfilling prophesy may often be high. Association of a gene or list of genes with a known function and an apparently related phenotype may result in the interpretation that this is the functionally relevant observation. A signalling pathway or network linking these genes and the phenotype, but constructed primarily by intuition or deduction, may be neither statistically nor functionally correct. Of course, the association(s) found may be both statistically significant and intuitively satisfying. In this case the issue becomes whether these associations are truth, partial truth or falsehood.

Conclusions and future prospects

Perhaps the most widely used approach to the analysis of high-dimensional data spaces is to reduce dimensionality. Although essential in exploratory data analysis for improved visualization or sample classification, dimension reduction requires careful consideration for signalling studies (FIG. 5). A separate but related challenge to the curse of dimensionality is computational complexity. As the best subset of variables (for example, genes or proteins) may not contain the best individual variables, univariate variable selection is suboptimal and a search strategy is required to find the best subset of informative variables19. For example, the joint effect of complex gene–gene interactions can result in changes in the expression of a single gene being uninformative, whereas it might be highly informative when considered together with others that also may be individually uninformative91. However, the number of possible subsets with various sizes grows exponentially with the dimensionality, making an exhaustive search impractical. New approaches to this problem continue to emerge. Sequential forward floating search (SFFS) is a computationally efficient method that considers variable (for example, gene or protein) dependencies when searching for variables that exhibit such a joint effect92,93. SFFS consists of a series of forward inclusion and backward exclusion steps (dynamically) where the best variable that satisfies a chosen criterion function is included with the current variable set. The worst variable is eliminated from the set when the criterion improves after a variable (gene) is excluded.

Working in the high-dimensional data spaces generated by transcriptome and proteome technologies has the potential to change how we approach many complex and challenging questions in cancer research. However, our ability to fully realize this potential requires an objective assessment of what we do and do not understand. For biologists, the most immediate difficulties come in attempting to interpret the biological knowledge embedded in the expression data. It seems logical to be guided by a solid understanding of causality or reasonable biological plausibility. However, in the absence of full knowledge of gene function and the effect of cellular context, the risk of falling into the trap of self-fulfilling prophesy becomes real — simply stated, “you see only what you know” (johann Wolfgang von Goethe, 1749–1832). When a solution is imperfect and/or appears to contradict biological knowledge, it is important to assess objectively whether this reflects an incomplete knowledge of the biological and/or functional data, whether the model applied to the data is at fault, or both.

Biologists can test experimentally their interpretations of the data and it is evidence of function from appropriate biological studies that will usually be the ultimate arbiter of truth, partial truth or falsehood. However, accurately extracting information from genomic or proteomic studies is of vital importance. The properties of high-dimensional data spaces continue to be defined and explored, and their implications require careful consideration in the processing and analysis of data from many of the newer genomic and proteomic technologies.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank D. J. Miller (Department of Electrical Engineering, The Pennsylvania State University) for critical reading of the manuscript. Some of the issues we discuss may appear overly simplified to experts. Several of the emerging concepts have yet to appear in the biomedical literature and publications might not be accessible through PubMed (but are often found at an author’s or journal’s homepage or at CiteSeer). Many of the engineering and computer science works published in ‘proceedings’ represent peer-reviewed publications. This work was supported in part by Public Health Service grants R01-CA096483, U54-CA100970, R33-EB000830, R33-CA109872, 1P30-CA51008, R03-CA119313, and a U.S. Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program award BC030280.

Glossary

- t-Test

- A significance test for assessing hypotheses about population means, usually a test of the equality of means of two independent populations.

- False discovery rate

- A univariate statistical method that controls the type I (false-positive) errors to correct for multiple testing.

- Cluster

- A cluster consists of a relatively high density of data points separated from other clusters by a relative low density of points; patterns within a clusterare more similar to each other than patterns belonging to different clusters.

- Massively parallel

- A large number of simultaneous processes; in biology a living cell has multiple, concurrently active processes that are reflected in the proteome and its underlying transcriptome.

- Trap of self-fulfilling prophesy

- With thousands of measurements and the concurrent presence of multiple sub-phenotypes, intuitively logical but functionally incorrect associations may be implied between a signal’s (gene or protein) perceived or known function in a biological system or phenotype of interest.

- Euclidean space

- Any mathematical space that is a generalization of the two-and three-dimensional spaces described by the axioms and definitions of Euclidean geometry, for example, properties of angles of plane triangles and of straight and parallel lines.

- k-Means clustering algorithm

- A method of cluster analysis in which, from an initial partition of the observations into k clusters, each observation in turn is examined and reassigned, if appropriate, to a different cluster, in an attempt to optimize a predefined numerical criterion that measures, in some sense, the quality of the cluster solution.

- Vector

- A coordinate-based data structure in which the information is represented by a magnitude and a direction.

- Hard clustering

- Any clustering method that forces a data point to belong only to a single cluster.

- Test pattern

- Also known as the testing set, this is a data point(s) that was not part of the training set, for example, in a leave-one-out approach the testing set is the sample that was left out during training.

- Training set

- The sample of observations from which a classification function is derived.

- Null hypothesis

- The hypothesis that there is no difference between the two groups for a variable that is being compared.

- Family-wise error rate

- The probability of making any error in a given family of inferences, rather than a per-comparison error rate or a per-experiment error rate.

- Clustering algorithm

- Procedure designed to find natural groupings or clusters in multidimensional data on the basis of measured or perceived similarities among the patterns.

- Surrogate

- A measure that substitutes for (and correlates with) a real endpoint but has no assured relationship for example tumour shrinkage in response to chemotherapy (surrogate) does not assure that the patient will live longer (endpoint).

- Soft clustering

- Any clustering method that allows a data point to be a member of more than one cluster.

- Vector space

- Space where data are represented by vectors that may be scaled and added as in linear algebra; two-dimensional Euclidean space is one form of vector space.

- Metric space

- A data space where the distance between each data point is specifically defined.

- Hierarchical clustering

- A series of models for a set of observations, where each model results from adding (or deleting) parameters from other models in the series.

- Logistic regression

- A method of analysis concerned with estimating the parameters in a postulated relationship between a response variable (binary for logistic regression) and one or more explanatory variables.

- Hyperplane

- A higher-dimensional generalization of the concepts of a plane in three-dimensional (or a line in two-dimensional) Euclidean geometry. A plane is a surface where, for any two points on the surface, the straight line that passes through those points also lies on the surface.

- Kernel function

- A mathematical transform operated upon one or multiple input variables; inner productor convolution is a popular form of kernel function.

- Regression coefficient

- A component of a statistical model in which a response variable is estimated by a number of explanatory variables, each combined with a regression coefficient that gives the estimated change in the response variable corresponding to a unit change in the appropriate explanatory variable.

- Agglomerative hierarchical clustering

- Methods of cluster analysis that begin with each individual in a separate cluster and then, in a series of steps, combine individuals, and later clusters, into new and larger clusters, until a final stage is reached where all individuals are members of a single group.

- Missing value estimation

- When an expected value is not reported for a specific gene or protein the missing value can be estimated and the estimated value used for data analysis.

- Normally distributed

- The value of a random variable(s) follows a probability-density function completely specified by the mean and variance.

- Parametric statistical model

- A statistical model, the probability distribution of which is specified by a relatively small set of quantitative parameters.

- Subcubical neighbourhood

- A smaller cubical area of a larger hypercubical space.

- Hypercubical neighbourhood

- A higher-dimensional generalization of the concepts of a cubic neighbourhood in three-dimensional Euclidean geometry.

- Bootstrap re-sampling

- A statistical method that iteratively uses subsets of the original data set to estimate the bias and variance for a classification algorithm.

- Scale-free behaviour

- The behaviour of an estimator is scale-free if it depends only on the ranks of the observations, for example, the estimator is equally accurate whether the logarithms of the observations or the values of the observations are used for analysis.

Footnotes

DATABASES

Entrez Gene: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=gene

ESR1 | p53 | RELA | TGFB1 | TNF

FURTHER INFORMATION

Robert Clarke's homepage: http://clarkelabs.georgetown.edu

Yue Wang's homepage: http://www.cbil.ece.vt.edu

Gene Ontology: http://www.geneontology.org

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes: http://www.genome.jp/kegg

Protein Information Resource: http://www.pir.georgetown.edu

CiteSeer: http://citeseer.ist.psu.edu

ALL LINKS ARE ACTIVE IN THE ONLINE PDF

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc2294

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc2238676?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

Preoperative prediction of CNS WHO grade and tumour aggressiveness in intracranial meningioma based on radiomics and structured semantics.

Sci Rep, 14(1):20586, 04 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39232068 | PMCID: PMC11374997

Construction of a pathway-level model for preeclampsia based on gene expression data.

Hypertens Res, 47(9):2521-2531, 24 Jun 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38914704

Predicting type 2 diabetes via machine learning integration of multiple omics from human pancreatic islets.

Sci Rep, 14(1):14637, 25 Jun 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38918439 | PMCID: PMC11199577

Review: Cancer and neurodevelopmental disorders: multi-scale reasoning and computational guide.

Front Cell Dev Biol, 12:1376639, 02 Jul 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39015651 | PMCID: PMC11249571

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Prediction of Acute Cardiac Rejection Based on Gene Expression Profiles.

J Pers Med, 14(4):410, 12 Apr 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38673037 | PMCID: PMC11051265

Go to all (256) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Primary transcripts: From the discovery of RNA processing to current concepts of gene expression - Review.

Exp Cell Res, 373(1-2):1-33, 26 Sep 2018

Cited by: 9 articles | PMID: 30266658

Review

Approaches to working in high-dimensional data spaces: gene expression microarrays.

Br J Cancer, 98(6):1023-1028, 19 Feb 2008

Cited by: 39 articles | PMID: 18283324 | PMCID: PMC2275474

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Introduction: Cancer Gene Networks.

Methods Mol Biol, 1513:1-9, 01 Jan 2017

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 27807826

Translational Metabolomics of Head Injury: Exploring Dysfunctional Cerebral Metabolism with Ex Vivo NMR Spectroscopy-Based Metabolite Quantification

CRC Press/Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton (FL), 14 Aug 2015

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 26269925

ReviewBooks & documents Free full text in Europe PMC

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NCI NIH HHS (11)

Grant ID: 54-CA100970

Grant ID: R03 CA119313

Grant ID: P30 CA051008

Grant ID: R33 CA109872

Grant ID: R33-CA109872

Grant ID: 1P30-CA51008

Grant ID: R01-CA096483

Grant ID: R03 CA119313-01A2

Grant ID: R01 CA096483

Grant ID: R03-CA119313

Grant ID: U54 CA100970

NIBIB NIH HHS (2)

Grant ID: R33 EB000830

Grant ID: R33-EB000830

1 (red patterns) and

1 (red patterns) and