Abstract

Purpose

Genetic counseling is now routinely offered to individuals at high risk of carrying a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Risk prediction provided by the counselor requires reliable estimates of the mutation penetrance. Such penetrance has been investigated by studies worldwide. The reported estimates vary. To facilitate clinical management and counseling of the at-risk population, we address this issue through a meta-analysis.Methods

We conducted a literature search on PubMed and selected studies that had nonoverlapping patient data, contained genotyping information, used statistical methods that account for the ascertainment, and reported risks in a useable format. We subsequently combined the published estimates using the DerSimonian and Laird random effects modeling approach.Results

Ten studies were eligible under the selection criteria. Between-study heterogeneity was observed. Study population, mutation type, design, and estimation methods did not seem to be systematic sources of heterogeneity. Meta-analytic mean cumulative cancer risks for mutation carriers at age 70 years were as follows: breast cancer risk of 57% (95% CI, 47% to 66%) for BRCA1 and 49% (95% CI, 40% to 57%) for BRCA2 mutation carriers; and ovarian cancer risk of 40% (95% CI, 35% to 46%) for BRCA1 and 18% (95% CI, 13% to 23%) for BRCA2 mutation carriers. We also report the prospective risks of developing cancer for currently asymptomatic carriers.Conclusion

This article provides a set of risk estimates for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers that can be used by counselors and clinicians who are interested in advising patients based on a comprehensive set of studies rather than one specific study.Free full text

Meta-Analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Penetrance

Abstract

Purpose

Genetic counseling is now routinely offered to individuals at high risk of carrying a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Risk prediction provided by the counselor requires reliable estimates of the mutation penetrance. Such penetrance has been investigated by studies worldwide. The reported estimates vary. To facilitate clinical management and counseling of the at-risk population, we address this issue through a meta-analysis.

Methods

We conducted a literature search on PubMed and selected studies that had nonoverlapping patient data, contained genotyping information, used statistical methods that account for the ascertainment, and reported risks in a useable format. We subsequently combined the published estimates using the DerSimonian and Laird random effects modeling approach.

Results

Ten studies were eligible under the selection criteria. Between-study heterogeneity was observed. Study population, mutation type, design, and estimation methods did not seem to be systematic sources of heterogeneity. Meta-analytic mean cumulative cancer risks for mutation carriers at age 70 years were as follows: breast cancer risk of 57% (95% CI, 47% to 66%) for BRCA1 and 49% (95% CI, 40% to 57%) for BRCA2 mutation carriers; and ovarian cancer risk of 40% (95% CI, 35% to 46%) for BRCA1 and 18% (95% CI, 13% to 23%) for BRCA2 mutation carriers. We also report the prospective risks of developing cancer for currently asymptomatic carriers.

Conclusion

This article provides a set of risk estimates for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers that can be used by counselors and clinicians who are interested in advising patients based on a comprehensive set of studies rather than one specific study.

INTRODUCTION

Genetic counseling is now routinely offered to individuals at high risk of carrying a BRCA1 (MIM 113705) or BRCA2 (MIM 600185) mutation. At-risk individuals receive advice and make decisions about genetic testing, screening, and prevention strategies such as chemoprevention and prophylactic surgeries. To personalize management strategies according to risk level, risk assessment is first given to the counselee, often through the use of a risk prediction model.1–4 Such a model predicts the risk of carrying a deleterious mutation and the risk of developing breast or ovarian cancer based on prespecified penetrance. In this article, penetrance refers to the risk of developing breast and ovarian cancers among BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Thus, a reliable estimate of penetrance is crucial for counseling and decision making.

Different penetrance leads to different risk assessments. This is currently problematic for risk counseling. There has been controversy over the extent of the variation and the reasons for it. To provide a basis for more evidence-based counseling and decision making, we investigate potential sources of variation and then integrate the penetrance estimates into a consensus set of penetrance.

METHODS

We addressed this issue via a meta-analysis. We performed a PubMed search for combinations of the following words in the title of the article: (“risk” OR “penetrance”) AND (“breast cancer” OR “ovarian cancer”) AND (“BRCA1” OR “BRCA2”). We then restricted attention to the studies that satisfied all of the following criteria: study was based on genotyping information; if the study was not population-based, the statistical analysis corrected for ascertainment; study reported age-specific breast and ovarian cancer risks for mutation carriers with CIs; and study patients did not overlap with patients in other included studies. Motivated by the extent of heterogeneity observed in the eligible studies, we combined the published estimates using the DerSimonian and Laird random effects modeling approach.5

RESULTS

Ten studies met our search criteria. Studies that provided risk-related information but failed to satisfy the criteria are listed in Appendix Table A1 (online only), with reasons for exclusion. In Table 1, we give a synopsis of the included studies, briefly describing study population, design, mutation testing information, and risk estimation methods.

Table 1

Characteristics of Eligible Studies

| Study | Population | Ascertainment | No. of Families | No. of Carriers* | Genotyping Method | Estimation Approach | Necessary Condition for Unbiasedness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ford et al6 and Easton et al7 | BCLC | Four or more patients | 237 | 64 + 36 | Markers flanking BRCA1/2 | Maximum LOD score, equivalent to retrospective likelihood | No additional familial aggregation other than BRCA1/2 |

| Struewing et al8 | AJs in Washington, DC area | Population-based volunteers | 4,873 | 61 + 59 | ASO and allele-specific PCR | Used empirical risk to first-degree relatives to deduce carrier risk | The incidence rate among the volunteers was the same as in the general AJ population |

| Hopper et al9 | Australian Cancer Registry | Population-based early-onset patients | 388 | 9 + 9 | PTT | (1) Repeated sampling; (2) joint likelihood of family history conditioning on the index patient and on her being a carrier | The predefined protein truncation mutations have the same penetrance as all mutations pooled |

| Satagopan et al10 | New York + Canada hospital-based AJ breast cancer patients | Population-based patients | 782 | 45 + 12 + 23† | PCR or ASO | Used patients from Struewing et al as a control group to estimate age-specific relative risk | The control group is representative of the general population in terms of mutation prevalence |

| Satagopan et al11 | AJ ovarian cancer patients from multiple hospitals | Population-based patients | 436 | 76 + 27 + 44† | PCR or ASO | Used patients from Struewing et al as a control group to estimate age-specific relative risk | The control group is representative of the general population in terms of mutation prevalence |

| Scott et al12 | kConFab, Australian | High-risk families with mutations | 53 | 28 + 23 | PTT or CCM or HA or DGGE, all with sequencing | Modified segregation analysis, similar to Ford et al | No additional familial aggregation other than BRCA1/2 |

| Antoniou et al13 | European + North America (Israel) + Australia + Hong Kong | Population-based patients | 8,139 | 289 + 221 | Various | Joint likelihood of family history conditioning on the index patient and on her being a carrier | No effect from size-biased sampling; or, risks to carrier patient cases and their relatives are not higher than carrier non–patient cases |

| King et al14 | New York hospital-based AJ breast cancer patients | Population-based patients | 1,008 | 42 + 25 + 37† in patients, 212 in relatives | Sequencing | Genotyped all relatives of found patient carriers and used Kaplan-Meier analysis | No effect from size-biased sampling; or, risks to carrier patient cases and their relatives are not higher than carrier non–patient cases |

| Marroni et al15 | From five Italian cancer genetic clinics | High-risk families | 568 | 46 + 39 | PTT-SSCP alone, with sequencing or with FAMA | Retrospective likelihood: joint likelihood of genotyping result conditioning on family history | No additional familial aggregation other than BRCA1/2 |

| Chen et al16 | AJ and non-AJ families from the US Cancer Genetics Network | High-risk families | 1,948 | 296 + 130 | Various | Retrospective likelihood | No additional familial aggregation other than BRCA1/2 |

Abbreviations: BCLC, Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium; AJ, Ashkenazi Jew; LOD, logarithm of the odds; ASO, allele-specific oligonucleotide; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PTT, protein truncation test; kConFab, Kathleen Cuningham Foundation Consortium for Research into Familial Breast Cancer; CCM, chemical cleavage mismatch; HA, heteroduplex analysis; DGGE, denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis; SSCP, single strand conformational polymorphism; FAMA, fluorescence-assisted mutational analysis.

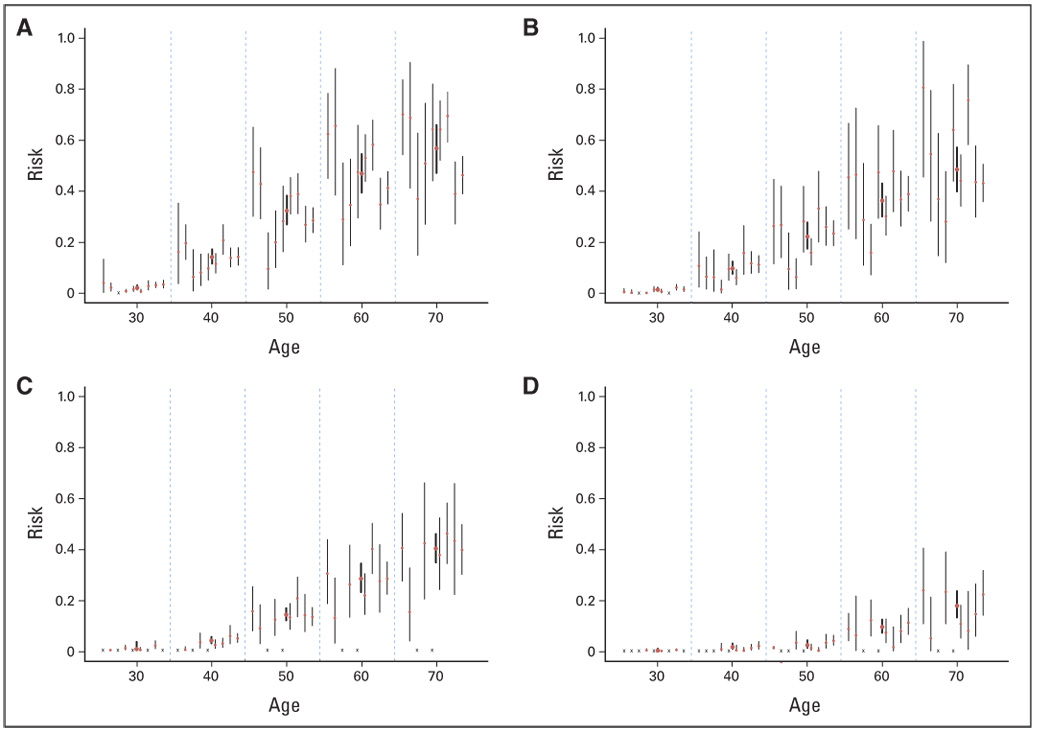

Heterogeneity was observed among the reported risks (Fig 1). Visual pairwise comparisons of CIs include many that overlap as well as some that do not. To quantify this study-to-study variation, we performed tests of heterogeneity5 for all age-specific risks, after logit transformation. With two cancer sites, two genes, and six age intervals, a total of 24 tests were performed. For ovarian cancer, nine of the 12 P values ranged from .11 to .92. The other three P values were .02, .04, and < .001; all occurred at age 30 years or younger, where the risk estimates are low and unstable. Therefore, we conclude that there is not enough evidence for heterogeneous ovarian cancer risks. Breast cancer risks are more heterogeneous. For BRCA1 carriers, all P values ranged from .001 to .045. For BRCA2 carriers, the P values were .23 and .22 at ages 20 and 30 years and between .02 and .05 at later ages.

(A) Breast cancer risk for BRCA1 carriers, (B) breast cancer for BRCA2 carriers, (C) ovarian cancer for BRCA1 carriers, and (D) ovarian cancer for BRCA2 carriers. The cumulative risk estimates from published studies (thin vertical bars) and the meta-analytic mean (thick vertical bars, height represents 95% CIs). Within each 10-year age interval, the published studies are arranged in the following order (left to right): Ford et al6 and Easton et al,7 Struewing et al,8 Hopper et al,9 Satagopan et al,10,11 Scott et al,12 Antoniou et al,13 King et al,14 Marroni et al,15 and Chen et al.16 An “x” represents not available.

Next, we searched for systematic sources of heterogeneity from various aspects of study characteristics. Systematic differences could arise from the mutation type, the study population, or the design/analysis strategy. Regarding mutation type, Hopper et al7 was the only study that exclusively looked at protein-truncating mutations. All other studies included carriers of a mixed pool of mutation types. If penetrance was mutation specific, we would wish to learn about the penetrance(s) associated with each distinct type of mutation(s). However, it is not presently feasible to separate the effects of mutations from these studies. Instead, a reachable goal is to learn about the average risk among a group of carriers with a representative mix of mutations in a population. Because Hopper et al9 looked only at protein-truncating mutations, which are reported to confer lower risks than other types of mutations, we conducted our meta-analysis of this risk both including and excluding this study. The issue of study populations is similar to that of mutation type in that different populations (by ethnicity, eg, Ashkenazi Jew v not, or geographic locations) may segregate different mutations or share different risk factors. Currently, there are studies containing more than one subpopulation; however, they provide limited evidence of population-specific variation in penetrance, either by geographical region or by ethnicity.13,16,17 Regarding design and analysis, as shown in Table 1, each study used an analysis method that addressed ascertainment mechanism in its design. Although it has been conjectured that the designs and analyses used in the studies may result in biases,8,9,13,18 which could generate the observed heterogeneity, some of the empirical evidence also suggests the contrary. For example, the Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium studied families with higher logarithm of the odds scores and also demonstrated that the penetrance estimates are equally high when families with low logarithm of the odds scores are included. Meanwhile, King et al14 used case series data and arrived at similar estimates. Scott et al,12 Marroni et al,15 and Chen et al16 used a similar design and analysis as Ford et al6 and reported lower penetrance. In summary, as the number of studies grows, there is no clear systematic trend attributable to the design and analysis.

Motivated by the lack of systematic heterogeneity among current penetrance estimates, we summarized them with a random effects model using the DerSimonian and Laird approach.5 The resulting consensus estimates are weighted averages of the risks reported by all studies, whereas their SEs take into account both within-study SEs and study-to-study heterogeneity. This approach relies on an assumption of normality of the random effects, which is reasonable because there is no pronounced asymmetry and no study is an obvious outlier.

On the basis of our analysis, we report the mean and standard deviation of the meta-analytic penetrance by 10-year age intervals, as shown in Figure 1. In a separate analysis, we excluded the Hopper et al9 study. However, the difference was minimal (< 0.1 percentage point at all age intervals).

For comparison, we also obtained the estimate of the penetrance assuming no interstudy variation. The resulting cumulative risks by age 70 years are as follows: breast cancer risk of 55% (95% CI, 50% to 59%) for BRCA1 and 47% (95% CI, 42% to 51%) for BRCA2 mutation carriers;and ovarian cancer risk of 39% (95% CI,34% to 45%) for BRCA1 and 17% (95% CI,13% to 21%) for BRCA2 mutation carriers. Compared with the random effects model, the point estimates are within 2 percentage points of each other. However, the CIs for breast cancer risks become much narrower by ignoring existing heterogeneity, whereas those for the ovarian cancer risks remain similar.

Penetrance curves based on these results have been incorporated in the genetic counseling and risk prediction software BayesMendel,3 which includes the BRCA mutation prediction tool BRCAPRO,19 and will be incorporated in the next version of CancerGene.20 Note that penetrance by definition is the net risk in the absence of any competing risks. We also derived the future risks of developing cancer for currently asymptomatic carriers after taking into account deaths as the competing cause (death hazard was obtained from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results 13 Incidence and Mortality, 2000–2002; http://seer.cancer.gov/canques/mortality.html). We report those risks in Table 2. An at-risk individual can directly read her prospective risks from this table, depending on her current age, and use them to make clinical decisions such as those regarding prophylactic surgeries.

Table 2

Predicted Mean Cancer Risk to Currently Unaffected BRCA1/2 Mutation Carriers

| Risk (%) of Developing Cancer by Age | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 Years | 40 Years | 50 Years | 60 Years | 70 Years | ||||||

| Current Age | Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI |

| Breast cancer: BRCA1 | ||||||||||

| 20 years | 1.8 | 1.4 to 2.2 | 12 | 9.5 to 14 | 29 | 24 to 35 | 44 | 37 to 52 | 54 | 46 to 63 |

| 30 years | — | 10 | 8.2 to 13 | 28 | 23 to 24 | 44 | 36 to 52 | 54 | 45 to 63 | |

| 40 years | — | — | 20 | 16 to 25 | 38 | 31 to 45 | 49 | 41 to 58 | ||

| 50 years | — | — | — | 22 | 18 to 27 | 37 | 30 to 44 | |||

| 60 years | — | — | — | — | 19 | 15 to 24 | ||||

| Breast cancer: BRCA2 | ||||||||||

| 20 years | 1 | 0.78 to 1.4 | 7.5 | 5.8 to 9.8 | 21 | 17 to 26 | 35 | 28 to 42 | 45 | 38 to 53 |

| 30 years | — | 6.6 | 5.1 to 8.6 | 20 | 16 to 26 | 35 | 28 to 42 | 45 | 38 to 53 | |

| 40 years | — | — | 15 | 12 to 19 | 30 | 24 to 36 | 42 | 34 to 49 | ||

| 50 years | — | — | — | 18 | 15 to 22 | 32 | 26 to 38 | |||

| 60 years | — | — | — | — | 17 | 14 to 20 | ||||

| Ovarian cancer: BRCA1 | ||||||||||

| 20 years | 1 | 0.68 to 1.8 | 3.2 | 2.3 to 5.1 | 9.5 | 7.3 to 13 | 23 | 18 to 28 | 39 | 34 to 44 |

| 30 years | — | 2.2 | 1.6 to 3.4 | 8.7 | 6.7 to 12 | 22 | 18 to 27 | 39 | 34 to 43 | |

| 40 years | — | — | 6.7 | 5.2 to 8.9 | 20 | 17 to 24 | 38 | 33 to 41 | ||

| 50 years | — | — | — | 15 | 12 to 17 | 34 | 29 to 36 | |||

| 60 years | — | — | — | — | 22 | 20 to 23 | ||||

| Ovarian cancer: BRCA2 | ||||||||||

| 20 years | 0.19 | 0.09 to 0.47 | 0.7 | 0.37 to 1.5 | 2.6 | 1.5 to 4.5 | 7.5 | 5.1 to 11 | 16 | 12 to 20 |

| 30 years | — | 0.52 | 0.28 to 1 | 2.4 | 1.5 to 4.2 | 7.4 | 5.1 to 11 | 16 | 12 to 20 | |

| 40 years | — | — | 1.9 | 1.2 to 3.2 | 7 | 4.8 to 10 | 16 | 12 to 20 | ||

| 50 years | — | — | — | 5.2 | 3.7 to 7.2 | 14 | 11 to 17 | |||

| 60 years | — | — | — | — | 9.8 | 7.8 to 11 | ||||

NOTE. The CI is provided for the mean risk, not the risk itself.

DISCUSSION

In this article, we integrated information on available studies on the risk of breast and ovarian cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers (penetrance), with the goal of assisting clinicians and counselors in understanding and combining the information provided by the numerous studies that have investigated this question.

A graphical summary of penetrance estimates (Fig 1) and statistical tests show that study-specific estimates are somewhat heterogeneous. However, after taking into account the estimates’ uncertainties, each study has CIs overlapping with several others, and there are no pronounced outliers. This suggests that the heterogeneity among studies is a surmountable obstacle.

A critical question in presence of heterogeneity is the identification of its sources. In this article, we systematically examined penetrance estimates across all studies, along with characteristics that are likely to be potential sources, including study population, mutation detection strategy, and design/analysis approach. A systematic comparison of groups of studies by potential heterogeneity source is informative about whether any of the characteristics can explain the variation. However, none of the potential sources considered was able to systematically explain the observed variation across studies. Because of the inherent complexity of gene characterization studies, there may be study characteristics that we have not been able to examine. However, it seems unlikely that there exists one simple answer to the nature of heterogeneity.

In current clinical practice, two scenarios are possible. In the first, the clinician is able to identify a single study that matches the relevant patient population for his or her practice. In the second, which is perhaps more common, there is no clear criterion for deciding which study is most appropriate for a particular patient. In this case, given current knowledge, a meta-analysis that acknowledges heterogeneity is the most evidence-based and, arguably, ethically sound approach to risk counseling. This does not conflict with the concept that risk counseling should be made as individualized as possible by taking into account well-understood risk modifiers.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by Grants No. P50CA88843, P50CA62924-05, 5P30 CA06973-39, and R01CA105090 from the National Cancer Institute; Grant No. HL99-024 from the National Institutes of Health, and the Hecht Fund.

Appendix

The Appendix is included in the full-text version of this article, available online at www.jco.org. It is not included in the PDF version (via Adobe® Reader®).

Footnotes

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2006.09.1066

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://ascopubs.org/doi/pdfdirect/10.1200/JCO.2006.09.1066?role=tab

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Article citations

Development of a novel prediction model for carriage of BRCA1/2 pathogenic variant in Japanese patients with breast cancer based on Japanese organization of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer registry data.

Breast Cancer Res Treat, 02 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39356394

Therapeutic upregulation of DNA repair pathways: strategies and small molecule activators.

RSC Med Chem, 11 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39430950 | PMCID: PMC11487406

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Cost-effectiveness of early vs delayed use of abemaciclib combination therapy for patients with high-risk hormone receptor-positive/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative early breast cancer.

J Manag Care Spec Pharm, 30(9):942-953, 01 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39213142 | PMCID: PMC11365564

Risk-reducing surgeries for breast cancer in Brazilian patients undergoing multigene germline panel: impact of results on decision making.

Breast Cancer Res Treat, 10 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39254767

Biological Functions and Therapeutic Potential of NAD+ Metabolism in Gynecological Cancers.

Cancers (Basel), 16(17):3085, 05 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39272943 | PMCID: PMC11394644

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (953) article citations

Other citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Diseases (2)

- (1 citation) OMIM - 600185

- (1 citation) OMIM - 113705

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

The average cumulative risks of breast and ovarian cancer for carriers of mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 attending genetic counseling units in Spain.

Clin Cancer Res, 14(9):2861-2869, 01 May 2008

Cited by: 65 articles | PMID: 18451254

Characterization of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in a large United States sample.

J Clin Oncol, 24(6):863-871, 01 Feb 2006

Cited by: 209 articles | PMID: 16484695 | PMCID: PMC2323978

BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation predictions using the BOADICEA and BRCAPRO models and penetrance estimation in high-risk French-Canadian families.

Breast Cancer Res, 8(1):R3, 12 Dec 2005

Cited by: 52 articles | PMID: 16417652 | PMCID: PMC1413985

[Clinical and molecular diagnosis of inherited breast-ovarian cancer].

J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris), 32(2):101-119, 01 Apr 2003

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 12717301

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NCI NIH HHS (12)

Grant ID: P30 CA006973

Grant ID: P50CA88843

Grant ID: R01CA105090

Grant ID: 5P30 CA06973-39

Grant ID: P50 CA088843

Grant ID: R01 CA105090-01A1

Grant ID: P50 CA062924

Grant ID: R01 CA105090

Grant ID: R01 CA105090-02

Grant ID: R01 CA105090-03

Grant ID: R01 CA105090-04

Grant ID: P50CA62924-05

NHLBI NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: HL99-024