Abstract

Free full text

Id1 cooperates with oncogenic Ras to induce metastatic mammary carcinoma by subversion of the cellular senescence response

Abstract

Recent evidence demonstrates that senescence acts as a barrier to tumorigenesis in response to oncogene activation. Using a mouse model of breast cancer, we tested the importance of the senescence response in solid cancer and identified genetic pathways regulating this response. Mammary expression of activated Ras led to the formation of senescent cellular foci in a majority of mice. Deletion of the p19ARF, p53, or p21WAF1 tumor suppressors but not p16INK4a prevented senescence and permitted tumorigenesis. Id1 has been implicated in the control of senescence in vitro, and elevated expression of Id1 is found in a number of solid cancers, so we tested whether overexpression of Id1 regulates senescence in vivo. Although overexpression of Id1 in the mammary epithelium was not sufficient for tumorigenesis, mice with expression of both Id1 and activated Ras developed metastatic cancer. These tumors expressed high levels of p19Arf, p53, and p21Waf1, demonstrating that Id1 acts to make cells refractory to p21Waf1-dependent cell cycle arrest. Inactivation of the conditional Id1 allele in established tumors led to widespread senescence within 10 days, tumor growth arrest, and tumor regression in 40% of mice. Mice in which Id1 expression was inactivated also exhibited greatly reduced pulmonary metastatic load. These data demonstrate that established tumors remain sensitive to senescence and that Id1 may be a valuable target for therapy.

A number of mechanisms act to suppress tumorigenesis, including cell cycle checkpoints, apoptosis, and immune surveillance. Evidence is emerging for a role for cellular senescence as an additional tumor suppressive response to oncogene activation. Oncogene-induced senescence (OIS) was initially described in cultured cells exposed to activated oncogenes and is defined as a proliferative arrest insensitive to mitogenic stimulation. A number of other cellular stresses such as exposure to DNA damaging agents or oxidative stress can also induce a senescence-like state. It is characterized by the expression of markers, including acidic beta-galactosidase (SA-βGal) and the CDK inhibitors p21waf1 and p16INK4A. Cells undergoing senescence in culture also adopt a distinctive flattened, vacuolar morphology.

The molecular sensors of OIS are variously reported to include components of the DNA damage response, the PML protein, and the p16INK4A or p19ARF tumor suppressors (reviewed in ref. 1). The retinoblastoma (RB) and p53 tumor suppressor pathways are generally required for the induction of OIS; however, the contribution of either varies between models and appears dependent on the initiating event and the cellular context. In some settings, p16INK4A is required for OIS, whereas, in others, p19ARF-p53-p21waf1 pathway is the essential effector of OIS.

Members of the Ras family of small GTPases are frequently involved in cancer, and overexpression or activating mutation of one of the three family members, HRAS, KRAS, and NRAS is found in a wide array of cancers, including breast cancer (2, 3). Mutant Ras oncoproteins signal through multiple effector pathways including the RAF-MAPK and PI3K-AKT pathways, to control survival, proliferation, and angiogenesis. In multiple mouse models of cancer, including lung, mammary, and osteosarcoma (4–8), oncogenic transformation by Ras or Raf oncogenes can trigger a p53-dependent senescence response. In humans, a proportion of melanocytic nevi carrying activating mutations in BRAF express markers of senescence (9). These data suggest a bona fide tumor suppressor role for senescence in mouse and certain human cancers.

Id1 encodes an HLH transcription regulator that, unlike other HLH factors, lacks a basic domain and hence is unable to bind DNA directly. Id1 instead is thought to function by forming inactive heterodimers with other HLH and helix–turn–helix factors, including MyoD, E proteins, and Ets transcription factors. Although Id1 is expressed in complex spatiotemporal patterns during mammalian embryonic development, its expression is undetectable in many mature tissues. However, in a number of advanced cancers, Id1 is reexpressed in a high proportion of cases. In breast cancer, Id1 is overexpressed in high grade tumors and estrogen receptor (ER) negative disease (10), and its expression correlates negatively with disease free survival of patients (11). Despite its common overexpression in solid cancers, little is known about the role of Id1 in tumorigenesis in vivo. Overexpression of Id1 in hematopoetic compartments leads to massive apoptosis, disruption of differentiation, and leukemia (12), and overexpression of Id1 in the intestine leads to adenomas with long latency and low penetrance (13).

Surprisingly, although the overwhelming majority of fatal cancers are carcinomas of epithelial origin, very few studies address the relative importance or molecular mediators of the senescence response in epithelial transformation. We used a mouse mammary model to investigate the role for senescence in carcinoma and show that hyperactive Ras signaling triggers a senescence response in vivo. This response can be subverted by inactivation of any member of the p19ARF–p53–p21waf1 pathway or by overexpression of Id1. Inactivation of Id1 in established tumors triggers widespread senescence and tumor regression.

Results

Activation of Ras Triggers Senescence in Vivo.

We used a mammary transplantation technique (14) to express activated Ras in the mammary epithelia. The majority of mice receiving Ras-transformed mouse mammary epithelial cells (MMECs) possessed well encapsulated microscopic nodules at the site of injection in their mammary fat pad. These foci contained disorganized epithelial cells and a high density of inflammatory cells, including abundant lymphocytes and polymorphonuclear cells (Fig. 1A).

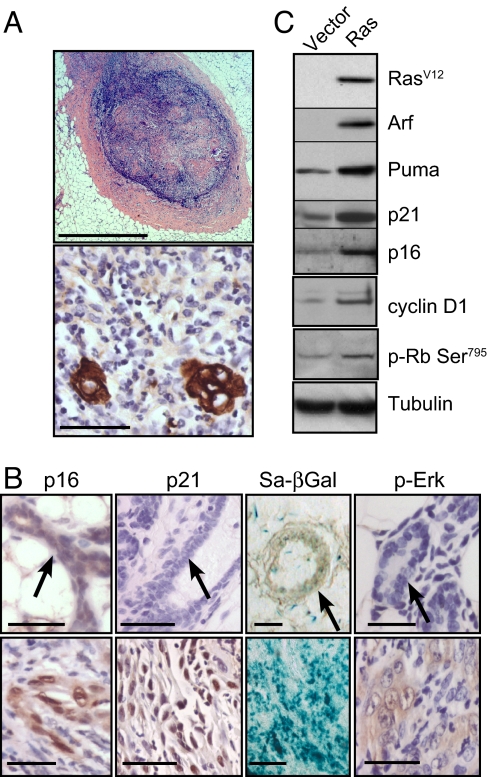

Ras activation triggers cellular senescence in vivo via p19ARF-p53-p21waf1 signaling. (A and B) Four weeks after transplantation, mammary fat pads of mice transplanted with MMECs expressing oncogenic Ras were harvested and sectioned. (A) Foci at the site of injection were stained with H&E (Upper) or an antibody to cytokeratins (Lower). (Scale bars: Upper, 1 mm; Lower, 100 μm.) (B) Ras-expressing glands (Lower) or controls (Upper) were stained for SA-βGal activity and by IHC for p-Erk1/2, p21waf1, and p16INK4A. Arrows indicate mammary ducts. (Scale bars: 100 μm.) (C) Seven days after infection and antibiotic selection in vitro, MMECs expressing oncogenic Ras or vector control were harvested, and extracts were analyzed by Western blot for components of the p16INK4A and p19ARF–p53 pathways.

Epithelial cells in these foci expressed elevated levels of phosphorylated Erk1/2—a marker of Ras activation (Fig. 1B). Given that Ras activation has been shown to elicit a senescence-like response in other models, we looked for evidence of senescence in the nodules. Epithelial cells within these nodules expressed elevated levels of several markers of senescence compared with controls: SA-βGal, p21waf1, and p16INK4A (Fig. 1B).

To further investigate the senescence pathways activated in these cells, we expressed oncogenic Ras in MMECs in vitro. Ras activation strongly increased expression of p19ARF, a tumor suppressor commonly activated by oncogenic mutation (15) (Fig. 1C). A key function of p19ARF is the inhibition of MDM2-mediated degradation of p53, so we tested whether Ras activation also leads to activation of p53. Although p53 was undetectable by Western blot analysis or immunohistochemistry, we detected increases in the expression of two canonical p53 targets, Puma and p21waf1, after Ras activation, suggesting increased p53 transcriptional activity (Fig. 1C).

Ras activation also induced p16INK4A expression (Fig. 1C). However, cyclin D1 was also induced, which would be presumed to have opposing effects to p16INK4A on CDK4/6 activity (Fig. 1C). To determine how phosphorylation of Rb by Cdk4/6 was affected by Ras overexpression, we used Western blot analysis to detect phosphorylation of Serine 795 of Rb, which is a substrate of Cdk4/6 but not Cdk2 (16). Rb phosphorylation at Ser-795 did not decrease after Ras overexpression but instead increased modestly (Fig. 1C), suggesting that Ras activation does not result in a net inhibition of cyclin D-Cdk4/6 activity.

To determine the requirements for p16INK4A, p19ARF, p53, and p21waf1 in tumor suppression and senescence, we activated Ras in wild type cells or cells genetically null for the complete ink4a/arf locus (which encodes both p16INK4A and p19ARF) or individually null for p19arf, p16ink4a, tp53 (p53), or cdkn1a (p21waf1). Deletion of the gene encoding any member of the p19ARF-p53-p21waf1 pathway was permissive for Ras-dependent tumorigenesis (Fig. 2A). These tumors displayed similar histological appearance [supporting information (SI) Fig. S1]. These tumors did not express SA-βGal and had low p16INK4A and p21waf1 expression by immunohistochemistry (IHC) (data not shown).

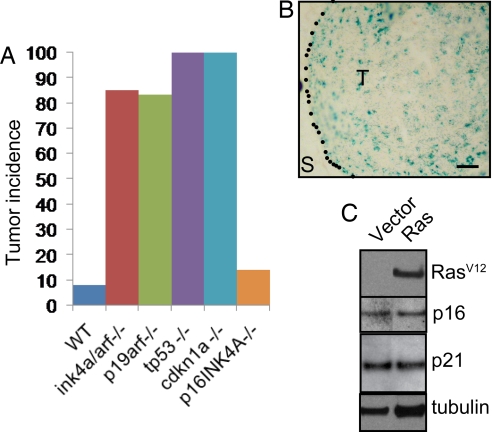

p19ARF, p53, and p21waf1 but not p16INK4A are required to suppress Ras-dependent tumorigenesis and senescence. (A) MMECs nullizygous for the indicated gene, or wild-type controls, were transduced with oncogenic Ras and transplanted to the cleared fat pads of naive hosts. Graph shows tumor incidence (>2 mm) 5 weeks after transplantation. n > 9 for each group. (B) p16ink4a−/− MMECs were transduced with oncogenic Ras and 4 weeks after mammary fat pad transplantation and stained for SA-βGal activity. S, stroma; T, transplanted cells. (Scale bar: 100 μm.) (C) p19arf−/− MMECs were transduced with oncogenic Ras in vitro, and extracts were analyzed by Western blot for RasV12, p16INK4A, p21waf1, and tubulin.

In contrast, p16INK4A loss was not permissive for Ras-dependent tumorigenesis, and, when transformed with oncogenic Ras, p16ink4a null MMECs formed tumors as infrequently as did wild-type cells (Fig. 2A). In fact, SA-βGal-positive cells were readily detected at the site of transplant of p16ink4a−/− MMECs transduced with Ras (Fig. 2B), suggesting that p16INK4A is not required for the induction of OIS in the mammary gland.

Based on these findings, we hypothesized that p16INK4A was induced as a consequence of senescence. We transduced p19arf null MMECs with activated Ras and western blotted for oncogenic Ras and p16INK4A. Ras was unable to induce senescence in these cells and was similarly unable to induce p16INK4A expression (Fig. 2C), confirming that p16INK4A is induced by Ras activation indirectly via activation of p19ARF. Similarly, activation of Ras did not lead to an increase in p21waf1 protein expression in these cells, confirming that Ras signals to p21waf1 via p19ARF (Fig. 2C).

Ras Cooperates with ID Proteins in Tumorigenesis.

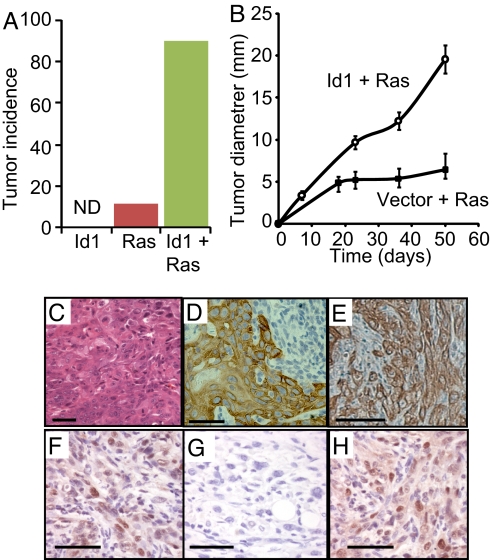

Id1 has been shown to antagonize Ras-induced senescence in vitro (17) so we asked whether Id1 could subvert the senescence response in vivo and thereby cooperate with Ras activation in tumorigenesis. Using the mammary transplant model described earlier, mice receiving transplants of MMECs transduced with Id1 alone did not develop palpable tumors within 6 weeks of transplant (Fig. 3A); however, coexpression of Id1 and Ras cooperated to produce a high frequency of rapidly growing aggressive tumors (Fig. 3 A and B and Fig. S2 A and B). These tumors focally expressed markers of both luminal (K18) and myoepithelial lineages (K14) (Figs. 3 C–E). Ninety percent of tumors in the Ras + Id1 group formed pulmonary micrometastases (<10 cells across), and 60% formed pulmonary macrometastases, frequently multiple (Fig. S2C). In contrast, tumors in the Ras-only group only occasionally formed micrometastases, which never progressed to macrometastases in the timeframe of these experiments.

Id1 and oncogenic Ras cooperate in mammary tumorigenesis. Mice received transplants of mammary epithelial cells (MMECs) transduced with oncogenic Ras, Id1 or oncogenic Ras + Id1. (A) Incidence of mammary tumors 6 weeks after transplant. n > 10 for all groups. ND, not detected (B) Diameter of tumors over time after transplantation. Error bars represent mean diameters ± SEM. n > 10 for both groups. (C–E) Sections from a tumor expressing oncogenic Ras and Id1 stained with hematoxylin and eosin C or antibodies to cytokeratins 14 (D) or 18 (E). (F–H) IHC for p21waf1 on sections from a focus of epithelium expressing activated Ras (F), a tumor derived from activated Ras expression in tp53 null MMECs (G), or a tumor expressing activated Ras and Id1 (H). (Scale bars: 100 μm.)

Because we had earlier shown that a functional p19ARF–p53–p21waf1 pathway is required for senescence, we then asked whether Id1 prevents activated Ras-dependent induction of the p19ARF–p53–p21waf1 pathway. Western blot analysis of virally transduced MMECs in vitro revealed that Ras activation up-regulates Cyclin D1, p16INK4A, p19ARF, and the p53 transcriptional targets p21waf1 and Puma equally in the presence or absence of concomitant Id1 overexpression (Fig. S2D), demonstrating that Id1 does not alter the ability of Ras activation to induce p53 activation.

We then examined steady state p21waf1 expression in vivo by IHC staining of sections from epithelial foci expressing activated Ras alone and compared them to expression levels in tumors driven either by activated Ras + Id1 in otherwise wild type cells or by activated Ras alone in cells nullizygous for tp53. As shown earlier, Ras activation alone induced p21waf1 expression (Fig. 3F), whereas tumors driven by the cooperation between Ras activation and p53 deficiency expressed very low levels of p21waf1 (Fig. 3G), consistent with a requirement for p53 in p21waf1 induction. In contrast, the aggressive tumors driven by activated Ras and Id1 overexpression maintained high levels of p21waf1 expression (Fig. 3H). Therefore, Id1 acted downstream of p21waf1 expression to subvert the senescence program induced by Ras activation.

Ras and Id1 Are Required for Tumor Maintenance.

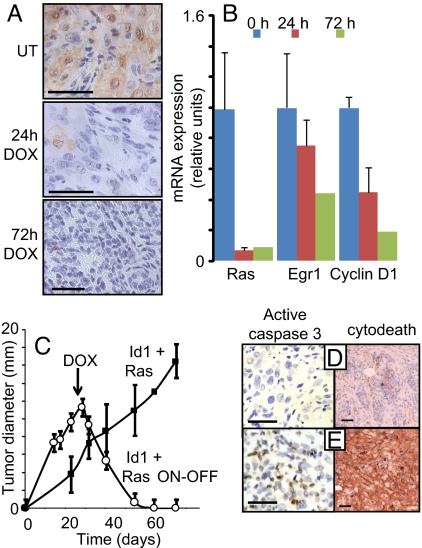

To investigate the requirement for Ras in tumor maintenance, we placed the hrasv12 transgene under the control of the TREti promoter while constitutively expressing Id1. Tumors formed with similar kinetics and phenotype as described earlier and when tumors were ≈8 mm in diameter, doxycycline was administered to mice to inactivate the TREti promoter. After doxycycline administration, the majority of Ras activity, as measured by h-Ras expression, the phosphorylation of Erk1/2, and the expression of transcriptional targets cyclin D1 and Egr1, was reduced within 1 day and dramatically decreased by 3 days (Fig. 4 A and B).

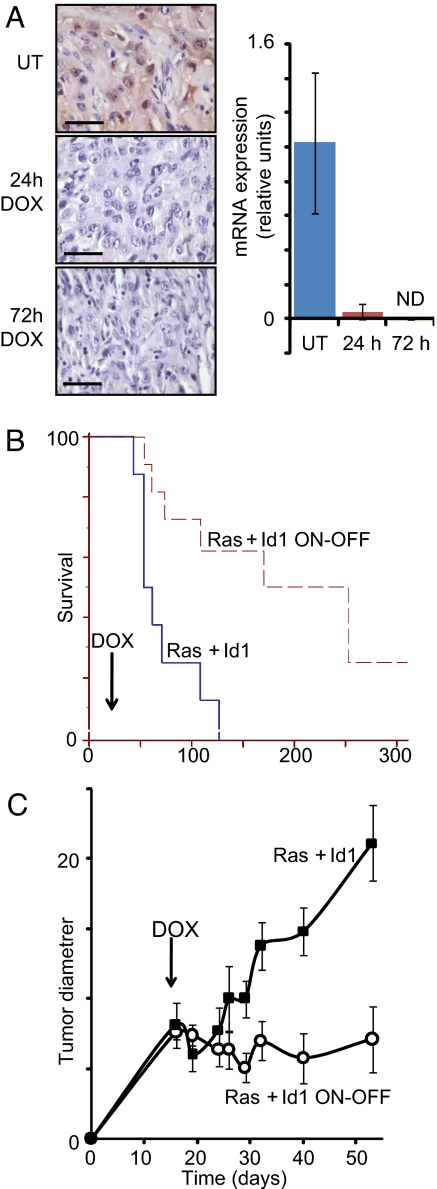

Sustained Ras activity is required for tumor survival. Mice received transplants of MMECs transduced with Id1 and the tetracycline transactivator (tTA), both expressed constitutively under the control of the MSCV LTR, in addition to oncogenic Ras under the control of the TREti conditional promoter. Twenty-one days after transplantation, mice received doxycycline (DOX) by a single IP injection and in their food to inactivate the hrasV12 transgene. (A) Immunohistochemical staining for p-Erk of tumor extracts harvested 0, 24, or 72 h after doxycycline administration. (B) mRNA expression of the hrasV12 transgene, Egr1, and cyclin D1 were determined by quantitative PCR, using RNA isolated from tumors 0, 24, or 72 h after doxycycline administration. Errors bars represent mean values ± SEM. (C) Tumor diameter in mice receiving doxycycline at day 21 (Id1+ Ras ON-OFF) or controls (Id1 + Ras) was measured over time. Error bars represent mean values ± SEM. (D and E) Sections of tumors from mice treated with doxycycline for 3 days (E) or controls (D) were stained with antibodies to activated caspase 3 (brown foci) or cleaved cytokeratin (M30 cytodeath). (Scale bars: 100 μm.)

Prolonged doxycycline administration led to the initiation of tumor regression within 8 days and complete regression within ≈40 days (Fig. 4C). Restoration of activated Ras expression by doxycycline withdrawal ≈60 days after administration was unable to reinitiate tumor growth after a further 30 days, suggesting complete tumor elimination (data not shown). To investigate the mechanism responsible for tumor regression, we stained sections of tumors treated with doxycycline for 3 days, or controls, with antibodies to cleaved caspase 3 or cleaved cytokeratin (cytodeath), a specific marker of epithelial apoptosis. Within 3 days of doxycycline administration, we observed staining for cleaved caspase 3 and cleaved cytokeratin indicating widespread apoptotic cell death (Fig. 4 D and E). These data suggest that activated Ras was required for mammary tumor cell survival.

We next turned our attention to the requirement for Id1 in tumor maintenance, and generated tumors carrying constitutive hrasv12 and conditional id1 transgenes. Twenty-one days after transplantation, doxycycline was administered to mice, and the id1 transgene expression was strongly reduced by 1 day and undetectable by 3 days (Fig. 5A). We observed a dramatic effect of id1 transgene repression on the survival of mice with a median survival time of 253 days from transplant for mice treated with doxycycline, compared with just 66 days for control mice (Fig. 5B).

Sustained Id1 expression is required for tumor growth. Mice received transplants of MMECs transduced with activated Ras and the tetracycline transactivator (tTA), both expressed constitutively under the control of the MSCV LTR, in addition to Id1 under the control of the TREti conditional promoter. Nineteen days after transplantation, mice received doxycycline by a single IP injection and in their food. (A) Analysis of tumor extracts harvested 0, 24, or 72 h after doxycycline administration by IHC, using Id1 antisera and by RT- PCR for the Id1 transgene. Errors bars represent mean values ± SEM. (B) Inactivation of the Id1 transgene at day 19 extends median time to ethical end point of mice from 66 days to 253 days. Kaplan–Meyer analysis, P < 0.003 (C) Tumor diameters in mice receiving doxycycline in their food (Ras + Id1 ON-OFF) or controls (Ras + Id1) were measured over time. Errors bars represent mean values ± SEM. Forty percent of tumors regressed to an undetectable state by day 80. n = 5–8 mice per time point for both groups. Statistical comparison (t test) between groups at each time point: P < 0.01 at days 29, 32, 40, and 53. (Scale bars: 100 μm.)

Importantly, although the majority of control mice demonstrated decreased body condition, cachexia, and metastatic tumors in the lung at the time their tumor size reached the ethical end point, only 10% of doxycycline-treated mice showed signs of significant ill-health and metastasis at the time their tumor size reached the ethical end point (data not shown), which was significantly later than control tumors. The tumors from these mice were typically fluid-filled cysts, and, under histological examination, the rims of these cysts were composed primarily of inflammatory cells and areas of necrosis with only sparse patches of epithelial cells (Fig. S3).

To address the mechanism of the requirement for Id1 in more detail, we measured the diameter of tumors after doxycycline administration. Doxycycline led to rapid cessation of tumor growth (Fig. 5C). Forty percent of doxycycline-treated tumors underwent regression to a nonpalpable state within 60 days of doxycycline administration, whereas all control tumors grew until the mice reached their ethical end point. Therefore, Id1 was required for the maintenance of tumor growth, even in established tumors. Thirty-three percent of regressed tumors spontaneously recurred after a variable period (>130 days after doxycycline administration in all cases) and were unresponsive to doxycycline treatment (data not shown), suggesting the acquisition of additional genetic or epigenetic alterations was required for regression.

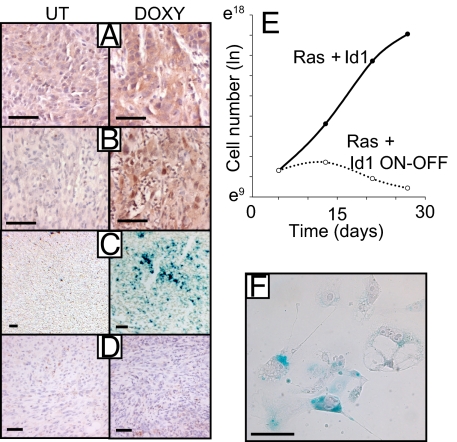

We examined sections of tumors from control mice or mice that had received acute doses of doxycycline. In contrast to Hrasv12 transgene inactivation (Fig. 4), we saw no evidence of increased apoptosis after id1 transgene inactivation, as measured by staining for the induction of cleaved cytokeratin (Fig. 6D) or activated caspase 3 (data not shown). We then asked whether Id1 may cooperate with Ras activation in tumorigenesis by subverting the senescence program described earlier, thus allowing Ras to promote tumor proliferation and survival. Sections taken from tumors treated with doxycycline for 10 days to inactivate the id1 transgene showed increases in the senescence markers SA-βGal, p16INK4A and DcR2 (Fig. 6 A–C). This striking result demonstrates that signaling from activated Ras to the p19ARF-p53-p21waf1 program persisted in vivo throughout malignant progression and that sustained Id1 overexpression was required to subvert p53-dependent senescence and tumor suppression.

Id1 regulates senescence in vivo. (A–D) Sections of tumors from mice treated with doxycycline or controls were stained for caspase-cleaved cytokeratin (D) (3 days Doxy), SA-βGal (C), p16INK4A (B), and DcR2 (A). (A–C) 10 days Doxy. (E and F) Cells from control tumors were cultured and treated with doxycycline at day 5 to inactivate the id1 transgene. (E) Cell number was measured over time after doxycycline administration. Cells were passaged every 6–8 days. (F) SA-βGal staining of cells 7 days after doxycycline administration. (Scale bars: 100 μm.)

To determine whether Id1 acted in a cell-autonomous capacity to subvert senescence, we cultured cells from control tumors and treated them with doxycycline to suppress Id1 expression. Although untreated cells continued to proliferate in culture, doxycycline-treated cells underwent synchronous growth arrest, displayed a flattened and vacuolar morphology and stained positive for SA-βGal (Figs. 6 E and F), all characteristics of cells undergoing senescence.

Discussion

Activation of Ras in the Mammary Gland Triggers p53-Dependent Senescence.

We set out to determine whether senescence plays a role in breast carcinoma initiation and maintenance and to identify the genes that regulate the process. We found that Ras activation and Id1 overexpression cooperate in mammary tumorigenesis and that Id1 functions by subverting a Ras-dependent senescence program downstream of p53 and p21Waf1.

Although activation of Ras has been known to trigger senescence in vitro for some time, Ras-dependent activation of senescence in vivo has only recently been demonstrated (see Introduction). More recently, Sarkisian et al. (5) demonstrated that activation of Ras induces a senescence-like phenotype in the mammary gland and that deinduction of Ras expression results in an apoptotic response. We also report the activation of a senescence-like arrest in response to Ras activation and show that sustained Ras activation is required for tumor maintenance.

Activation of Ras in MMECs nullizygous for inkarf, p19arf, tp53, or cdkn1a (p21waf1) was sufficient to generate tumors with almost identical penetrance and histological type, suggesting an epistatic relationship between p19ARF, p53, and p21waf1. Although p16INK4A was induced by Ras activation, we show that up-regulation of p16INK4A was secondary to p53 pathway activation and that deletion of p16ink4a was not sufficient to prevent senescence. Therefore, the p19ARF–p53–p21waf1 pathway, not p16INK4A, was required for Ras-dependent senescence. Consistent with this proposal, human breast cancer cell lines respond to activation of ErbB2 (18) or Ras (19) by the induction of senescence that depends on p21waf1 expression.

Several studies have implicated Id1 in the repression of p16INK4A expression during replicative or oncogene induced senescence in vitro (20–21). However, we have shown that increased p16INK4A expression is not critical to the senescence response of mammary epithelia and that Id1 does not significantly regulate p16INK4A expression. This disparity with previous studies may reflect a fundamental difference between the biology of epithelial cells and fibroblasts; the latter are by far the predominant cell type used to study senescence. Our findings are consistent with the observation that, in clinical breast cancer samples, there is a positive correlation between Id1 and p16INK4A expression (11).

Although mutation of Ras is generally not considered to occur commonly in breast cancer, recent detailed analysis shows that 30% of breast cancer cells lines (2) and 9% of primary carcinomas (22) carry mutant RAS or BRAF genes, making them relatively commonly mutated protooncogenes in breast cancer. Breast cancers also commonly exhibit elevated Ras activity (23, 24). Because we have overexpressed oncogenic Ras, it is possible that we have induced senescence by driving levels of Ras activation not seen in human cancer. However, in fibroblasts (25) and mammary epithelia (5) expressing low levels of oncogenic Ras, the progression to neoplastic transformation is accompanied by dramatic up-regulation of Ras expression.

Mechanism of Id1 Function.

Id1 regulates angiogenesis under certain circumstances (26, 27) and an alternative explanation for our observations is that Id1 permits Ras-dependent tumorigenesis by driving tumor angiogenesis. However, several lines of evidence refute this proposal.

First, angiogenesis can be considered to be broadly controlled by the balance of proangiogenic factors, such as VEGF, and anti-angiogenic factors, such as thrombospondin 1 (Tsp1). We were unable to detect changes in Tsp1 mRNA expression in cells overexpressing Id1 (A.S. and J.M.B., unpublished data) and observed an increase in VEGF-A expression by Western blot analysis after Ras activation that was unaffected by concomitant Id1 overexpression (A.S. and J.M.B., unpublished data). Second, using hypoxiprobe reagent to assay levels of hypoxia in vivo, we found no difference between benign nodules expressing activated Ras alone and tumors expressing both activated Ras and Id1 (A.S. and J.M.B., unpublished data). Third, deletion of p21waf1 was sufficient to rescue Ras-dependent tumorigenesis, although p21waf1 has no reported function in angiogenesis. Our data suggest that angiogenesis is not the rate-limiting process regulated by Id1 in this model.

Instead, we show that Id1 acts to prevent cellular senescence. How Id1 achieves this end is unclear, but tumors expressing activated Ras and Id1 continue to proliferate with high levels of p21waf1, suggesting that Id1 acts downstream of p21waf1 to maintain cellular proliferation. Id1 was required beyond initiation of tumorigenesis and established tumors expressing activated Ras and Id1 responded to Id1 loss by the induction of senescence. Therefore, tumors in vivo, like cells in culture (28), can become “addicted” to Id1 expression. Forty percent of tumors fully regressed after id1 transgene inactivation, and the remaining tumors were mainly inflammatory cysts with a small carcinoma component. We conclude that the senescence signals from activated oncogenes, such as Ras, can persist through breast cancer development and that, under certain circumstances, breast tumors are primed to undergo senescence. Basal-like breast cancers exhibit amplification of the kras locus (3) and overexpress both Kras and Id1 (10). Our results suggest that targeting of Id1 or the p19ARF-p53-p21waf1 pathway, for example in metastatic basal-like cancers, may be sufficient to reactivate a tumor-suppressive senescence program and lead to positive therapeutic outcomes.

Experimental Procedures

Details of mouse strains and procedures are available in SI Methods.

Cell Culture.

Primary mammary epithelial cells were cultured and retrovirally transduced as described in ref. 14. Cells were transplanted into recipients within 2 days of retroviral transduction. HA-tagged murine Id1, human oncogenic Ras (H-Ras carrying an Alanine to Valine substitution at codon 12), and the tetracycline transactivator (tTA) were constitutively expressed from the vector pMig [a gift from Yosef Refaeli (National Jewish Medical and Research Center, Denver, CO)]. The pRQ conditional gene expression vector was used to express Id1 or HrasV12. Transgenes were cloned downstream of the TREtight promoter (Clontech). pRQ also contains a PGK-PuroR cassette for selection. All plasmid constructs are available from Addgene (www.addgene.org).

Cellular Analysis.

Western blot analysis was performed by using standard procedures with the following antibodies: Id1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; catalog no. SC488), hRas (Epitomics; catalog no. 1521), p16INK4A (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; catalog no. SC1207), p21waf1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; catalog no. SC471), p19ARF (Abcam; catalog no. AB80), PUMA (Cell Signaling Technology; catalog no. 4976), cyclin D1 (Cell Signaling Technology; catalog no. 2978), and p-Rb Ser-795 (Cell Signaling Technology; catalog no. 9301).

mRNA abundance was determined by Taqman gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems) for human HRas and murine Id1, Egr1, cyclin D1, p21waf1, and p16INK4A.

IHC was performed on 4 μM sections of paraffin embedded tissues, using the following antibodies: p-Erk (Cell Signaling Technology; catalog no. 4376), p21waf1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; catalog no. SC471), p16INK4A (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; catalog no. SC1207), Id1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; catalog no. SC488), Pan cytokeratins (Sigma), cleaved caspase 3 (Cell Signaling Technology; catalog no. 9661), Dcr2 (Stressgen; catalog no. AAP-371), and M30 cytodeath (Roche Applied Science). Detailed protocols are available upon request.

Ten micromolar frozen sections were prepared from tissue embedded in OCT compound and snap frozen at −80°C. Staining for SA-βgal was performed by using a commercial kit (Cell Signaling Technology; catalog no. 9860).

Statistical Analysis.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves were prepared by using Medcalc (Medcalc Software). All other analyses were performed by using Excel (Microsoft).

Acknowledgments.

We thank all members of the Bishop laboratory for their helpful insights and assistance; Robert L. Sutherland for his support of this project; and Luda Urisman, Alana Welm, Sue Kim, Sanaz Maleki, and Sandra O'Toole for their assistance. This work was supported by the G. W. Hooper Research Foundation and a Clive and Vera Ramaciotti Foundation Establishment Grant. A.S. is a recipient of a C. J. Martin postdoctoral fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0801505105/DCSupplemental.

References

Articles from Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America are provided here courtesy of National Academy of Sciences

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0801505105

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc2291136?pdf=render

Free after 6 months at www.pnas.org

http://www.pnas.org/cgi/content/abstract/105/14/5402

Free after 6 months at www.pnas.org

http://www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/105/14/5402

Free after 6 months at www.pnas.org

http://www.pnas.org/cgi/reprint/105/14/5402.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Article citations

Proactive and reactive roles of TGF-β in cancer.

Semin Cancer Biol, 95:120-139, 11 Aug 2023

Cited by: 12 articles | PMID: 37572731 | PMCID: PMC10530624

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Inducible TgfbR1 and Pten deletion in a model of tongue carcinogenesis and chemoprevention.

Cancer Gene Ther, 30(8):1167-1177, 25 May 2023

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 37231058 | PMCID: PMC10754272

Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs), Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs) and Their Interplay with Cancer Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs): A New World of Targets and Treatments.

Cancers (Basel), 14(10):2408, 13 May 2022

Cited by: 14 articles | PMID: 35626011 | PMCID: PMC9139858

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Repurposing Cannabidiol as a Potential Drug Candidate for Anti-Tumor Therapies.

Biomolecules, 11(4):582, 15 Apr 2021

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 33921049 | PMCID: PMC8071421

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Signaling levels mold the RAS mutation tropism of urethane.

Elife, 10:e67172, 17 May 2021

Cited by: 9 articles | PMID: 33998997 | PMCID: PMC8128437

Go to all (73) article citations

Data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Dose-dependent oncogene-induced senescence in vivo and its evasion during mammary tumorigenesis.

Nat Cell Biol, 9(5):493-505, 22 Apr 2007

Cited by: 310 articles | PMID: 17450133

Resistance of primary cultured mouse hepatic tumor cells to cellular senescence despite expression of p16(Ink4a), p19(Arf), p53, and p21(Waf1/Cip1).

Mol Carcinog, 32(1):9-18, 01 Sep 2001

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 11568971

Depletion of ERK2 but not ERK1 abrogates oncogenic Ras-induced senescence.

Cell Signal, 25(12):2540-2547, 30 Aug 2013

Cited by: 26 articles | PMID: 23993963

Tumor suppressors and oncogenes in cellular senescence.

Exp Gerontol, 35(3):317-329, 01 May 2000

Cited by: 221 articles | PMID: 10832053

Review