Abstract

Free full text

CD36, a Scavenger Receptor Involved in Immunity, Metabolism, Angiogenesis, and Behavior

Abstract

CD36 is a membrane glycoprotein present on platelets, mononuclear phagocytes, adipocytes, hepatocytes, myocytes, and some epithelia. On microvascular endothelial cells, CD36 is a receptor for thrombospondin-1 and related proteins and functions as a negative regulator of angiogenesis. On phagocytes, through its functions as a scavenger receptor recognizing specific oxidized phospholipids and lipoproteins, CD36 participates in internalization of apoptotic cells, certain bacterial and fungal pathogens, and modified low-density lipoproteins, thus contributing to inflammatory responses and atherothrombotic diseases. CD36 also binds long-chain fatty acids and facilitates their transport into cells, thus participating in muscle lipid utilization, adipose energy storage, and gut fat absorption and possibly contributing to the pathogenesis of metabolic disorders, such as diabetes and obesity. On sensory cells, CD36 is involved in insect pheromone signaling and rodent fatty food preference. The signaling pathways downstream of CD36 involve ligand-dependent recruitment and activation of nonreceptor tyrosine kinases, specific mitogen-activated protein kinases, and the Vav family of guanine nucleotide exchange factors; modulation of focal adhesion constituents; and generation of intracellular reactive oxygen species. CD36 in many cells is localized in specialized cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains and may also interact with other membrane receptors, such as tetraspanins and integrins. Identification of the precise CD36 signaling pathways in specific cells elicited in response to specific ligands may yield novel targets for drug development.

Overview

CD36 was described nearly 30 years ago as “glycoprotein IV,” the fourth major band (of ~88 kD) observed on SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels of platelet membranes (1). It was later found to be identical to the antigen recognized by the monoclonal antibody OKM5, a marker for monocytes and macrophages (2). CD36 is present on many mammalian cell types: microvascular endothelium; “professional” phagocytes including macrophages, dendritic cells, microglia, and retinal pigment epithelium; erythroid precursors; hepatocyes; adipocytes; cardiac and skeletal myocytes; and specialized epithelia of the breast, kidney, and gut (3). CD36 is the defining member of a gene family (4, 5) that includes two other members in vertebrates, LIMP-2 (lysosomal integral membrane protein–2) and CLA-1 (CD36 and LIMP-2 analogous), which is also known as SRB-1 (scavenger receptor B-1). The primary structure of CD36 family members is conserved in mammals, and multiple orthologs have been identified in most orders of insect (Diptera, Hymenoptera, Coleoptera, and Lepidoptera) (6) as well as in nematodes, sponges (7), and slime mold, suggesting that the common ancestral gene appeared more than 300 million years ago.

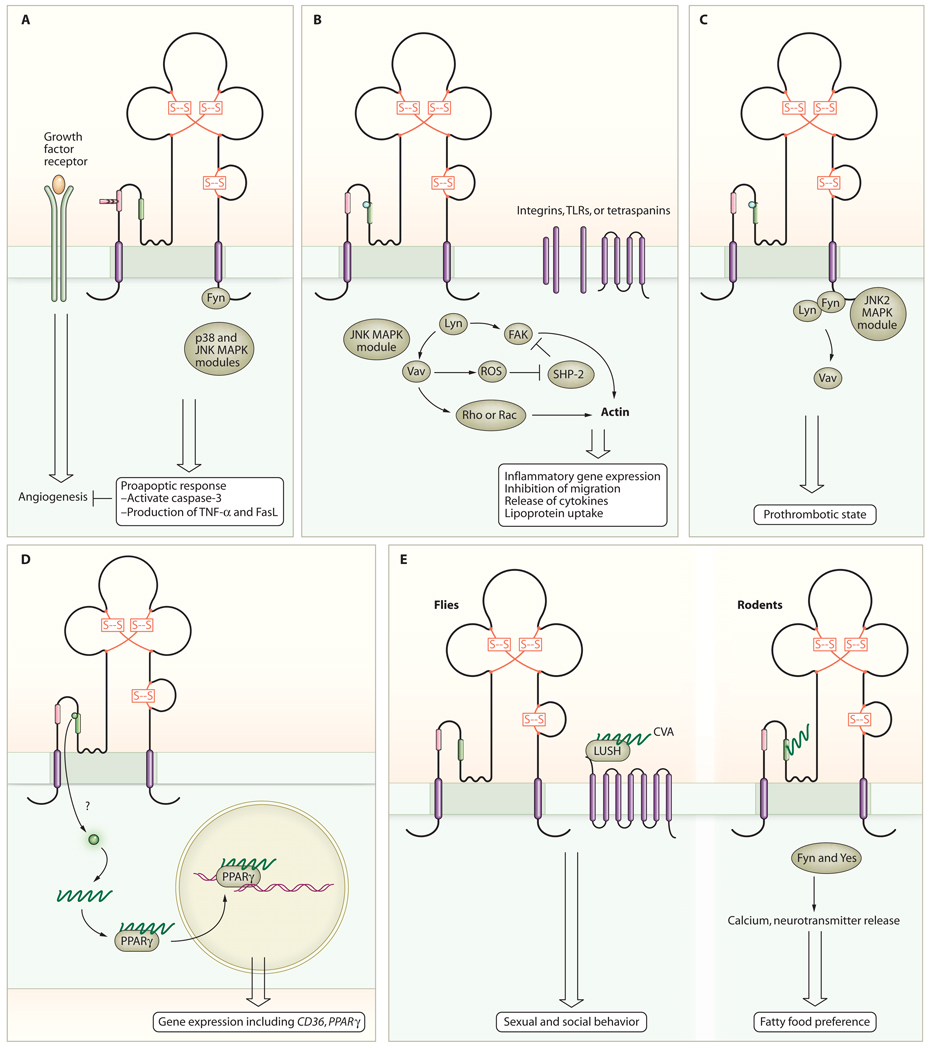

CD36 in Angiogenesis

The diverse expression pattern of CD36 is reflective of its multiple cellular functions. It is a receptor for thrombospondin-1 (8, 9) and several other proteins containing peptide domains known as thrombospondin type I repeats (TSRs) (10). In this capacity on microvascular endothelial cells, it functions as an endogenous negative regulator of angiogenesis (11) and, therefore, plays a role in tumor growth, inflammation, wound healing, and other pathological processes requiring neovascularization. CD36 accomplishes this function by inhibiting growth factor–induced proangiogenic signals that mediate endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and tube formation and instead generating anti-angiogenic signals that lead to apoptosis (11, 12). Pharmacologic and genetic knockout experiments identified the signaling pathway downstream of CD36 in this setting as one involving the nonreceptor protein tyrosine kinase Fyn, the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) p38 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and caspase-3 (12) (Fig. 1A). Downstream induction of expression of additional proapoptotic effectors, including Fas ligand and tumor necrosis factor–α (TNF-α), is also involved (13, 14).

CD36 mediates cell-specific responses. (A) In endothelial cells, CD36 inhibits angiogenesis induced by growth factors, such as fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and promotes apoptosis. (B) In macrophages and monocytes, CD36 promotes inflammatory responses and phagocytosis. CD36 may interact with other receptors, such as integrins, TLRs, or tetraspanins, to mediate some of the responses. (C) In platelets, CD36 promotes activation, aggregation, and secretion. (D) In monocytes and macrophages, CD36 promotes the uptake of bioactive lipids, leading to activation of PPARγ transcriptional pathways. (E) In sensory cells, CD36 contributes to cellular responses in the mouth and gut to dietary fats in mammals (right) and to pheromone responses in Drosophila (left).

CD36 as a Pattern Recognition Receptor

CD36 functions as a scavenger receptor— that is, a pattern-recognition receptor—on phagocytic cells (15). In addition to CD36, scavenger receptors include the structurally unrelated proteins SRA, CLA-1, lectinlike oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor (LOX)–1, macrophage receptor with collagenous structure (Marco), Toll-like receptors (TLRs), and CD68, among others. These proteins evolved with the innate immune system as primitive receptors that recognized and helped the organism eliminate foreign agents (for example, bacteria, parasites, and viruses) during an infection (16, 17). The hallmark of these receptors is their ability to recognize specific classes of molecular patterns presented by pathogens or by pathogen-infected cells. CD36 recognizes specific lipid and lipoprotein components of bacterial cell walls (18)—particularly those of staphylococcal and mycobacterial organisms (19), β-glucans on fungal species (20), and erythrocytes infected with falciparum malaria (4, 21)—and thereby triggers a reaction that results in opsonin-independent pathogen internalization. As with many other scavenger receptors, CD36 also recognizes endogenously derived ligands, including apoptotic cells (22–24), shed photoreceptor outer segments (25, 26), oxidatively modified lipoproteins (15, 27), glycated proteins, and amyloid-forming peptides (28, 29). Studies of model organisms have shown that scavenging is an evolutionarily ancient function of CD36. For example, the protein products of the Drosophila croquemort (30, 31) and peste (19) genes are CD36 orthologs present on blood cells and are involved in recognition and clearance of apoptotic cells and mycobacteria, respectively. CO3F11.3, an ortholog on cells of the worm Caenorhabditis elegans, participates in the innate immune response to fungi (20).

Because of the potential importance of CD36 ligands in disease pathogenesis, including atherosclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease, the scavenger receptor functions of CD36 have been extensively studied. For example, recognition and internalization of oxidized forms of low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL) by macrophage CD36 promotes the formation of lipid-laden “foam cells” and atherosclerotic plaque (27, 32–34); triggers proinflammatory reactions, such as activation of the transcription factor nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) (35, 36), release of cytokines, and production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (37, 38); and inhibits macrophage migration (38, 39) [thus trapping cells in an inflammatory milieu (40)] (Fig. 1B). Similarly, CD36-dependent interaction of β-amyloid (Aβ) peptide with microglial cells leads to internalization of the peptides and a proinflammatory response (29, 41, 42) and may contribute to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. On blood platelets, the interaction of CD36 with oxLDL (43) or anionic phospholipids presented on the surface of cell-derived microparticles (44) renders the platelets more sensitive to activation by low doses of agonists and may represent a mechanistic link between oxidative stress, hyperlipidemia, inflammation, and pathological thrombosis (Fig. 1C). On dendritic cells of the immune system, CD36 mediates uptake of apoptotic cells and provides a mechanism for cross-presentation of antigens to cytotoxic T cells (24). CD36 may also play a role in cytokine-mediated macrophage fusion and granuloma formation (45).

Studies of mice with targeted deletion of the cd36 gene show that loss of CD36 confers protection from diet-induced atherosclerosis (32) and thrombosis (44) and limits inflammation and tissue infarction associated with acute cerebrovascular occlusion (37), but may increase susceptibility to certain infections (18). The athero-protective role of CD36 deficiency is controversial (46–48), but the preponderance of evidence supports an important role for CD36 in mediating macrophage responses described above that are proatherogenic. Studies in several in vivo model systems show smaller plaque lesions (32, 49–51) or less-complex lesions (48), less aortic cholesterol, or all three in the absence of CD36 (48). The reason for discrepancy among murine studies may relate to environmental factors that induce stress or inflammation and the type of analysis performed. We hypothesize that CD36, because of its unique specificity for ligands generated during host responses to atheroinflammatory diseases (that is, oxidized phospholipids and apoptotic cells), may function as a “disease sensor” capable of triggering a signaling cascade that could influence macrophage and platelet responses and contribute to disease pathology.

The mechanisms by which CD36 signaling in response to scavenger ligands leads to multiple outcomes, such as providing the trigger for internalization or phagocytosis of the bound ligand [a so-called “eat me signal” (21–28, 52)], induction of leukocyte proinflammatory responses (29, 35–42, 53), and promotion of platelet granule secretion and integrin activation (43, 44, 54), have been partially characterized. In all cases, the intracellular signals involve recruitment and activation of Src family nonreceptor protein tyrosine kinases and serine/threonine kinases of the MAPK family, analogous but not identical, to kinases downstream of CD36 in endothelial cells (12, 42, 52, 55). Lyn and JNK2 are critical effectors of both macrophage and platelet responses, whereas Fyn and p38 are the primary mediators of endothelial cell responses, showing that cellular context is critical to understanding the signaling components engaged by CD36 (Fig. 1). The signaling partners downstream of the Src family kinases and MAPKs are not fully elucidated, although studies have implicated focal adhesion components, including the tyrosine kinases Pyk 2 and FAK (focal adhesion kinase) and the adaptor proteins p130cas and paxillin in some responses (38, 56). For example, after macrophage exposure to oxLDL, FAK undergoes prolonged phosphorylation and activation (38) because of direct activation by Src family kinases coupled with inactivation of a specific phosphatase, SHP-2. The latter was the result of intracellular ROS generation and subsequent oxidative inactivation of a critical cysteine residue in the enzymatic active site. The net results of these intracellular events were enhanced actin polymerization, increased cellular spreading, and inhibition of migration. The Vav family of proteins may also link CD36 to downstream events (57). These proteins are known substrates for Fyn and Lyn and, when activated by phosphorylation, function as guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) for Rho and Rac guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases). Vavs are large multidomain proteins that contain two SH3 domains flanking a single SH2 domain, and, thus, they function as scaffolds as well as GEFs. Vavs are phosphorylated in macrophages, microglial cells, and platelets in a CD36-dependent manner and may be an important link between CD36 and responses requiring small molecular weight guanine nucleotide–binding proteins (G proteins).

CD36-Mediated Lipid Uptake

A ligand-specific aspect of CD36 signaling involves its capacity to deliver biologically active lipids to cells (58) (Fig. 1D). Incubation of monocytes with oxLDL increases transcription of several genes, including the one encoding CD36, through activation of the nuclear hormone receptor peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor γ (PPARγ) (59). The activating ligand(s) for PPARγ are oxidized phospholipids, such as 9- and 13-HODE (hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid), and these, their precursor lipids, or both are part of the cargo delivered to the cell within the oxLDL particle. Although PPARγ is generally thought to promote anti-inflammatory responses, the presence of macrophages with abundant CD36 expression in the setting of oxLDL is proinflammatory and proatherogenic. It is likely that, before the advent of the fat- and calorie-rich Western diet, uptake of modified LDL was rare and localized and up-regulation of CD36 was a mechanism for sequestration of this aberrant ligand. Continuous exposure to oxLDL, however, leads to development and accumulation of lipid-laden macrophages and contributes to a dysfunctional response. Although PPARγ activation is clearly an important component of CD36 signaling in monocytes and macrophages, most of the responses to CD36 ligands cannot be accounted for by a transcriptional mechanism. For example, internalization of large particulate ligands requires rapid induction of intracellular signals to effect cytoskeletal reorganization and direct internalized ligands to specific intracellular compartments but does not require new protein synthesis. Similarly, the rapid proinflammatory, prothrombotic responses are mostly nontranscriptional.

CD36 also functions on adipocytes, muscle cells, enterocytes, and hepatocytes as a facilitator of long-chain fatty acid transport (60–64). There is evidence for CD36 binding to fatty acids and oxidized fatty acids, but the mechanism by which it facilitates fatty acid uptake remains vague (60, 65). Expression of the gene encoding CD36 in this context is controlled by the lipogenic transcription factors PPARγ, liver X receptor (LXR), and pregnane X receptor (PXR) (59, 61), and in skeletal muscle its abundance correlates with oxidative potential and is regulated by exercise and insulin (66, 67). In muscle, there is evidence for an intracellular pool of CD36 that can be translocated to the plasma membrane to increase fatty acid uptake (68). Cd36-null mice show abnormal plasma lipid and lipoprotein profiles and resting hypoglycemia (69), attributable in part to a marked impairment of fatty acid utilization in cardiac and striated muscle and of fatty acid uptake by adipose tissues (62). Studies in rodents and humans suggest that CD36–fatty acid interactions may contribute to the pathogenesis of metabolic disorders, such as insulin resistance, obesity, and nonalcoholic hepatic steatosis (70–75). The mechanistic role of CD36 in metabolic disease is likely to be complex and context dependent. CD36 contributes to intracellular lipid accumulation and might, therefore, be expected to promote lipotoxicity and, hence, insulin resistance. In several animal models, ablation of CD36-mediated lipid uptake in muscle or liver prevented lipotoxicity (76–78). In models in which CD36 was specifically induced in the liver by pharmacologic means or cDNA transduction, CD36 contributed to steatosis, which can also contribute to metabolic disorders (61, 68). Alternatively, a cd36-null mutation in the spontaneously hypertensive rat strain has been linked to insulin resistance (79, 80); however, the complete absence of CD36 in that model has come into question (81). Insulin and glucose infusion studies of a small number of human participants lacking CD36 showed insulin resistance (71), but other similar studies have not (82–84). CD36 deficiency in human participants is associated with multiple different compound mutations that may not only affect CD36 but also expression of other genes that could affect phenotype (85, 86). Although it may be counterintuitive, ablation of CD36 may also lead to insulin resistance. Mice null for cd36 are not whole-body insulin resistant, but they demonstrate liver insulin resistance (87). The phenotype is masked by the essential utilization of glucose by muscle because fatty acid uptake is impaired. One can imagine that differential organ or cell-specific CD36 expression may differentially affect insulin resistance and that this may underlie the discrepancies among the human studies.

In the gut, CD36 promotes absorption of long-chain fatty acids (63, 64) and participates in carotenoid uptake for vitamin A metabolism (88, 89). The mammalian CD36 homolog, SRB1, is present on steroidogenic tissues and hepatocytes, where it mediates selective cellular cholesterol uptake from high-density lipoprotein (HDL) particles (90). This provides cells with essential precursors for steroid hormone synthesis and also provides a mechanism to “unload” excess cholesterol from peripheral tissues through so-called “reverse cholesterol transport.” The mechanisms by which CD36 and related family members affect these lipid uptake functions are topics of ongoing study and controversy.

CD36 in Sensory Perception

As with the scavenging functions of CD36, study of model organisms has shed light on biological implications of CD36–fatty acid interactions (Fig. 1D). Many insect species have a CD36 ortholog, SNMP (sensory neuron membrane protein), on dendrites of the specialized neural cells in antennae involved in pheromone detection (91, 92). Drosophila SNMP functions as part of a multiprotein signaling complex, along with specific G protein–coupled odorant receptors (including Or67d and Or83b), that recognizes a fatty acid–derived pheromone, cis-vaccenyl acetate (CVA) (93, 94). CVA binds to the soluble odorant binding protein LUSH, inducing a conformational change in LUSH and allowing it to bind to the odorant receptor complex and initiate sexual and social aggregation behavior (95, 96). SNMP is required for electrophysiologic responses to CVA; snmp-null cells show increased spontaneous electrical activity but totally lack induced activity in response to CVA-LUSH, suggesting perhaps that SNMP serves a regulatory function in signal transduction. Interestingly, more than a dozen CD36 orthologs have been identified in the genomes of insect species with functions related to pheromone signaling, innate immunity, phagocytic clearance of apoptotic cells, and various aspects of fatty acid metabolism. The ninaD and santa maria genes in Drosophila, for example, encode proteins involved in gut uptake of carotenoids and activation of β-carotene monooxygenase in the eye (97).

CD36 also has a role in chemical sensory responses in mammalian species. CD36 is abundant on the apical surface of about 12 to 15% of circumvallate taste bud cells in the lingular papillae (98). Exposure to long-chain fatty acids, such as linoleic acid, causes a CD36-dependent rise in intracellular calcium concentration in these cells associated with neurotransmitter release, activation of gustatory neurons in the brain, and a rapid and sustained increase in the flux and protein content of pancreatobiliary secretions (98–101). In rodents, this series of reactions results in preferential attraction to lipid-rich food and at the same time readies the gut for a fatty meal (98, 99). These traits are lost in cd36-null animals. Similar to the signaling pathways identified in endothelial cells, macrophages, and platelets, the CD36-mediated neurosensory response is associated with phosphorylation of specific Src family kinases (in this case, Fyn and Yes), and inhibition of these kinases blocks neurotransmitter release in response to linoleic acid (99). Interestingly, duodenal infusion of fat (bypassing the tongue) in rodents leads to mobilization of oleoylethanolamide (OEA), a fatty acid derivative that suppresses feeding behavior. OEA synthesis requires dietary oleic acid and is deficient in cd36-null animals (102). Thus, CD36 sensing of fatty acids in the gut provides negative feedback to the fat feeding– promoting activity of CD36 sensing in the tongue.

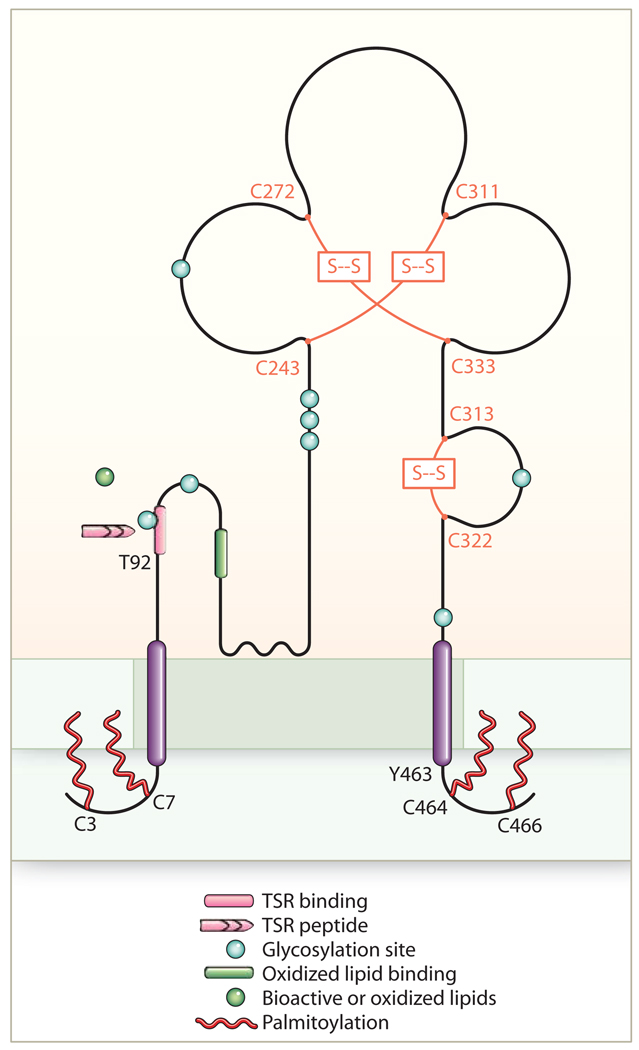

CD36 Organization, Membranes, Partners

As summarized above, CD36-mediated biological responses to its varied array of ligands in numerous cells and tissues have relevance to multiple homeostatic, developmental, and pathological processes, including eating preferences and sexual behavior. Considerable interest is currently focused on the mechanisms by which CD36 transmits intracellular signals and thereby affects its many functions. CD36 has two transmembrane domains, short intracytoplasmic domains of five to seven and 11 to 13 amino acids and a large extracellular domain with six conserved cysteines linked in three disulfide bridges (3, 86) (Fig. 2). The extracellular domain includes a hydrophobic region between amino acids 184 and 204 that may potentially interact with the plasma membrane. The extracellular domain is heavily glycosylated, accounting for the observed molecular weight that is 30 to 40,000 daltons greater than the weight predicted from the cDNA. Studies of recombinant proteins expressed in insect cells suggest that 9 of the 10 asparagine residues in the extracellular domain are glycosylated and that glycosylation is necessary for correct trafficking to the plasma membrane (103). Both of the intracellular domains contain paired cysteine residues that are lipid acylated and thus probably tightly associated with the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane (104) (Fig. 2). CD36 can be ubiquitinated on lysines 469 and 472 of the C-terminal domain (105), and this can target it to lysosomes, thus regulating its abundance. Interestingly, CD36 ubiquitination was stimulated by increasing fatty acid concentrations and inhibited by insulin, suggesting potential physiologic regulation of CD36 activity by this pathway (105).

Topology and domains of CD36. This ditopic transmembrane receptor resides in lipid raft membrane domains (shown shaded) and may interact with other cell surface receptors, such as integrins, tetraspanins, and TLRs (not shown). Ligand recognition may be modulated by phosphorylation of CD36 at Thr (92) (T). The extracellular domain contains three disulfide bridges (Cys243- Cys311, Cys272-Cys333, and Cys313-Cys322), multiple glycosylation sites, and at least two separate ligand binding domains, one for proteins with thrombospondin repeat (TSR) domains and one for oxidized lipids. The N- and C-terminal tails contain paired palmitoylated cysteine residues. Tyr463 and Cys464 in the C-terminal tail are important for ligand binding and for interaction with downstream signaling molecules.

The extracellular domain mediates ligand recognition and contains independent binding sites for TSR peptides (106, 107) and oxidized phospholipids (108, 109); the structural basis for fatty acid binding remains largely unknown (5, 60). The mechanisms by which a receptor with minimal intracellular presence, no intrinsic kinase or phosphatase activity, no known intracellular scaffolding domain(s), and no direct link to GTPases activates multiple signaling pathways remain poorly understood but are under intense study. A common theme in CD36 signal transduction is activation of Src family kinases (110) and MAPKs. Antibodies to CD36 coprecipitate specific Src kinases and upstream MAPK kinases (MAPKKs) from lysates of different cell types, and incubation of cells with CD36 ligands, such as oxLDL, increases the amount of activated (phosphorylated) Src kinases in the precipitates (52, 54). These studies suggest that CD36 associates with and participates in assembly of a dynamic signaling complex essential to downstream functions. It is highly likely that the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain of CD36 directs these associations. Point mutations of specific tyrosine or cysteine residues (Y463 or C464) in this domain (53) result in loss of response to ligands, and a recombinant protein containing this cytoplasmic domain precipitated a multiprotein complex from monocytes that contained Lyn, a MAPKK, and several as-yet-unidentified proteins (52). Because CD36 resides in cholesterol-rich, detergent-insoluble lipid raft domains and copurifies with caveolae from some tissues (111–114), it is possible that CD36 signaling relates to its localization in these membrane regions in which signaling molecules, such as Src, accumulate. It is also possible that residence in these domains facilitates lipid transport through a docking mechanism and aid from associated membrane and cytoplasmic proteins. CD36 is phosphorylated on an extracellular threonine residue (115), which influences binding of several ligands (115, 116) and may effect internalization and signaling.

It is also likely that CD36 may effect signal transduction, in part, by interacting with other membrane receptors, such as integrins, tetraspanins (117), and TLRs. The latter was elegantly demonstrated in studies showing cooperation between CD36 and TLR2 or TLR6 in macrophage recognition and response to bacteria and bacterial cell wall components, such as Staphylococcus-derived lipoteichoic acid (LTA) and diacylated lipoproteins (18, 118, 119). In some studies, however, some components of the proinflammatory response and bacteria uptake were shown to be dependent on CD36-JNK signaling (120, 121) and did not require TLR-mediated activation of NF-κB. TLRs do not appear to be required for CD36-dependent uptake of oxLDL (52) or apoptotic cells. Several CD36 functions require integrins, and both β2 (28, 57) and β3 (117) integrins coimmunoprecipitated with CD36. Internalization of apoptotic cells and photoreceptor outer segments requires integrins–αvβ3 in macrophages (22) and αvβ5 in dendritic cells (24) and retinal pigment epithelia (122). Microglial responses to Aβ require β2 integrins, and the spreading of brain tumor cells on thrombospondin- 1 seems controlled by a functional interaction between β1 integrins and CD36 (123).

In summary, CD36-mediated signaling pathways are conserved, defined by certain common themes, and involved in many critical cellular processes, but still relatively poorly understood. Figure 1 outlines our current model. Careful dissection of pathways in the context of specific cells and ligands may yield novel insights for drug development of multiple disorders.

References and Notes

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1126/scisignal.272re3

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc2811062?pdf=render

Free to read at stke.sciencemag.org

http://stke.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/sigtrans;2/72/re3

Subscription required at stke.sciencemag.org

http://stke.sciencemag.org/cgi/reprint/sigtrans;2/72/re3.pdf

Subscription required at stke.sciencemag.org

http://stke.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/sigtrans;2/72/re3

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Article citations

Genome-wide copy number variation association study in anorexia nervosa.

Mol Psychiatry, 12 Nov 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39533101

Single-cell landscape of innate and acquired drug resistance in acute myeloid leukemia.

Nat Commun, 15(1):9402, 30 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39477946 | PMCID: PMC11525670

Sex-specific phenotypical, functional and metabolic profiles of human term placenta macrophages.

Biol Sex Differ, 15(1):80, 17 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39420346 | PMCID: PMC11484421

Regulation of CD8+ T cells by lipid metabolism in cancer progression.

Cell Mol Immunol, 21(11):1215-1230, 14 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39402302 | PMCID: PMC11527989

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Combined Dietary <i>Spirulina platensis</i> and <i>Citrus limon</i> Essential Oil Enhances the Growth, Immunity, Antioxidant Capacity and Intestinal Health of Nile Tilapia.

Vet Sci, 11(10):474, 04 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39453066 | PMCID: PMC11512375

Go to all (623) article citations

Data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Mechanisms of cell signaling by the scavenger receptor CD36: implications in atherosclerosis and thrombosis.

Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc, 121:206-220, 01 Jan 2010

Cited by: 107 articles | PMID: 20697562 | PMCID: PMC2917163

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

CD36 as a multiple-ligand signaling receptor in atherothrombosis.

Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem, 9(1):42-55, 01 Jan 2011

Cited by: 43 articles | PMID: 20939828

Review

Class B scavenger receptors CD36 and SR-BI are receptors for hypochlorite-modified low density lipoprotein.

J Biol Chem, 278(48):47562-47570, 10 Sep 2003

Cited by: 48 articles | PMID: 12968020

Role of CD36 in membrane transport of long-chain fatty acids.

Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care, 5(2):139-145, 01 Mar 2002

Cited by: 101 articles | PMID: 11844979

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NHLBI NIH HHS (8)

Grant ID: P01 HL087018-03

Grant ID: P50 HL081011-040001

Grant ID: R01 HL085718

Grant ID: P01 HL087018-030004

Grant ID: P50 HL081011-04

Grant ID: R01 HL085718-02

Grant ID: P01 HL087018

Grant ID: P50 HL081011