Abstract

Free full text

Epigenetic antagonism between Polycomb and SWI/SNF complexes during oncogenic transformation

Summary

Epigenetic alterations have been increasingly implicated in oncogenesis. Analysis of Drosophila mutants suggests that Polycomb and SWI/SNF complexes can serve antagonistic developmental roles. However, the relevance of this relationship to human disease is unclear. Here we have investigated functional relationships between these epigenetic regulators in oncogenic transformation. Mechanistically, we show that loss of the SNF5 tumor suppressor leads to elevated expression of the Polycomb gene EZH2 and that Polycomb targets are broadly H3K27-trimethylated and repressed in SNF5-deficient fibroblasts and cancers. Further, we show antagonism between SNF5 and EZH2 in the regulation of stem cell-associated programs and that Snf5 loss activates those programs. Finally, using conditional mouse models, we show that inactivation of Ezh2 blocks tumor formation driven by Snf5 loss.

Introduction

Epigenetic modifications, somatically heritable changes in gene expression derived from changes in chromatin structure not from changes in DNA sequence, serve crucial roles in cell fate decisions and are increasingly appreciated as having roles in oncogenic transformation (Jones and Baylin, 2007; McKenna and Roberts, 2009; Sparmann and van Lohuizen, 2006). Global alterations in covalent histone-tail modifications, such as acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation, are frequently observed in cancer, as are aberrant expression of enzymes mediating these reactions (Wang et al. 2007a; Yu et al. 2007). Alterations in nucleosome positioning are also contributors to oncogenesis, and specific mutations in chromatin remodeling complexes that utilize ATP to reposition nucleosomes contribute to the formation of a growing list of tumors (Lin et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2007). While genomic instability is present in most cancers, a subset of aggressive cancers are diploid and largely devoid of genomic alterations suggesting that genomic instability is dispensable for cancer formation and further highlighting important contributions of epigenetic alterations in oncogenesis (McKenna et al. 2008; McKenna and Roberts 2009). Gaining insight into the mechanisms by which epigenetic alterations drive cancer formation is an area of intense interest in cancer research because unlike DNA mutations epigenetic modifications are reversible, raising the possibility that therapeutics that specifically target epigenetic modifiers may be more effective in the treatment of cancer. While epigenetically based changes are increasingly recognized, the underlying mechanisms and contributions of individual chromatin modifying enzymes are not well understood.

Proteins from the Polycomb group (PcG) contribute to epigenetically based gene silencing during development and evidence is emerging to suggest that they may serve important roles during oncogenic transformation (Bracken and Helin, 2009; Simon and Lange, 2008). The PcG protein EZH2 is highly expressed in a range of cancer types, including breast, prostate, and lymphomas, and is often correlated with advanced stages of tumor progression and poor prognosis, although the mechanisms underlying the upregulation of EZH2 are poorly understood. EZH2 serves as the catalytic subunit in the PRC2 polycomb repressor complex and mediates gene silencing by catalyzing the trimethylation of histone 3 lysine 27 (H3K27) at the promoters of target genes. A number of studies, using tumor cell lines, have concluded that EZH2 may contribute to oncogenic transformation. Similarly, reducing the levels of EZH2 leads to growth inhibition and reduced tumor formation in tumor cell line transplantation models (Varambally et al. 2002; Bracken et al. 2003; Simon and Lange 2008). Collectively, these findings have led to the hypothesis that over-expression of EZH2 is an important driver of oncogenesis and that targeted inactivation of EZH2 may have therapeutic efficacy against these cancers in vivo.

Accumulating evidence has suggested that SWI/SNF complexes oppose epigenetic silencing by PcG proteins. Antagonistic relationships between SWI/SNF components and PcG proteins were first uncovered via genetic studies in Drosophila where mutations in core components of the SWI/SNF complex were found to suppress defects in body segment identity conferred by mutations in PcG proteins (Kennison and Tamkun, 1988). Insight into the underlying mechanism came when it was discovered that PcG proteins maintain repression of Hox genes during embryogenesis, while the SWI/SNF complex promotes Hox gene activation (Kennison, 1995; Tamkun et al., 1992). Subsequent in vitro work with mammalian proteins showed that SWI/SNF complexes mediate changes in gene expression by utilizing the energy of ATP to reposition nucleosomes and remodel chromatin and that this enzymatic activity can be counteracted by PcG proteins (Shao et al. 1999; Francis et al. 2001). Lastly, re-expression of SNF5 into a SNF5-deficient tumor cell line led to increased activation of the tumor suppressor protein p16INK4a and removal of PcG proteins at the p16INK4a locus (Kia et al., 2008; Oruetxebarria et al., 2004). Intriguingly, while PcG proteins are frequently overexpressed in cancer, core components of the SWI/SNF complex are frequently inactivated in cancer.

The SWI/SNF complex represents a novel link between epigenetic regulation and tumor suppression. Inactivation of the core SNF5 subunit leads to aggressive cancer formation and a familial cancer predisposition syndrome. Malignant rhabdoid tumors, which arise in the brain, kidney and other soft tissues following biallelic inactivation of SNF5, are aggressive and highly lethal cancers that strike young children. The list of tumors with frequent loss of SNF5 is expanding and includes several aggressive cancers (Reisman et al., 2009; Roberts and Biegel, 2009). Mouse models have validated the tumor suppressor function of Snf5 as heterozygous Snf5 mice are tumor prone and biallelic conditional inactivation of Snf5 leads to fully penetrant cancer formation with a median onset of 11 weeks (Guidi et al., 2001; Klochendler-Yeivin et al., 2000; Roberts et al., 2000; Roberts et al., 2002). Furthermore, accumulating evidence raises the possibility that SWI/SNF complexes have a more widespread role in preventing tumorigenesis as specific mutations of this complex have been identified in cancers of the lung, breast, prostate, and pancreas (Roberts and Orkin 2004; Medina et al. 2008; Reisman et al. 2009). While perturbations in SWI/SNF complexes can lead to aggressive widespread tumor formation, the mechanism underlying the formation of these tumors has remained elusive. Accumulating evidence suggests that epigenetic changes play a critical role in the genesis of cancer. The presence of genome instability and widespread genetic mutations in the majority of cancers makes it difficult to evaluate the role of epigenetic alterations as it is unclear which, if any, of these epigenetic alterations are primary drivers of cancer and which are secondary passengers. In contrast, SNF5-deficient cancers, despite being highly aggressive, are diploid and genomically stable, suggesting a critical epigenetic influence and making them an ideal model with which to elucidate epigenetic drivers of oncogenesis (McKenna et al. 2008; McKenna and Roberts 2009).

Here, we investigate a functional relationship between SNF5 and EZH2 in oncogenic transformation by examining the role of EZH2 in driving SNF5-deficient tumors.

Results

Ezh2 is upregulated in Snf5-deficient tumors

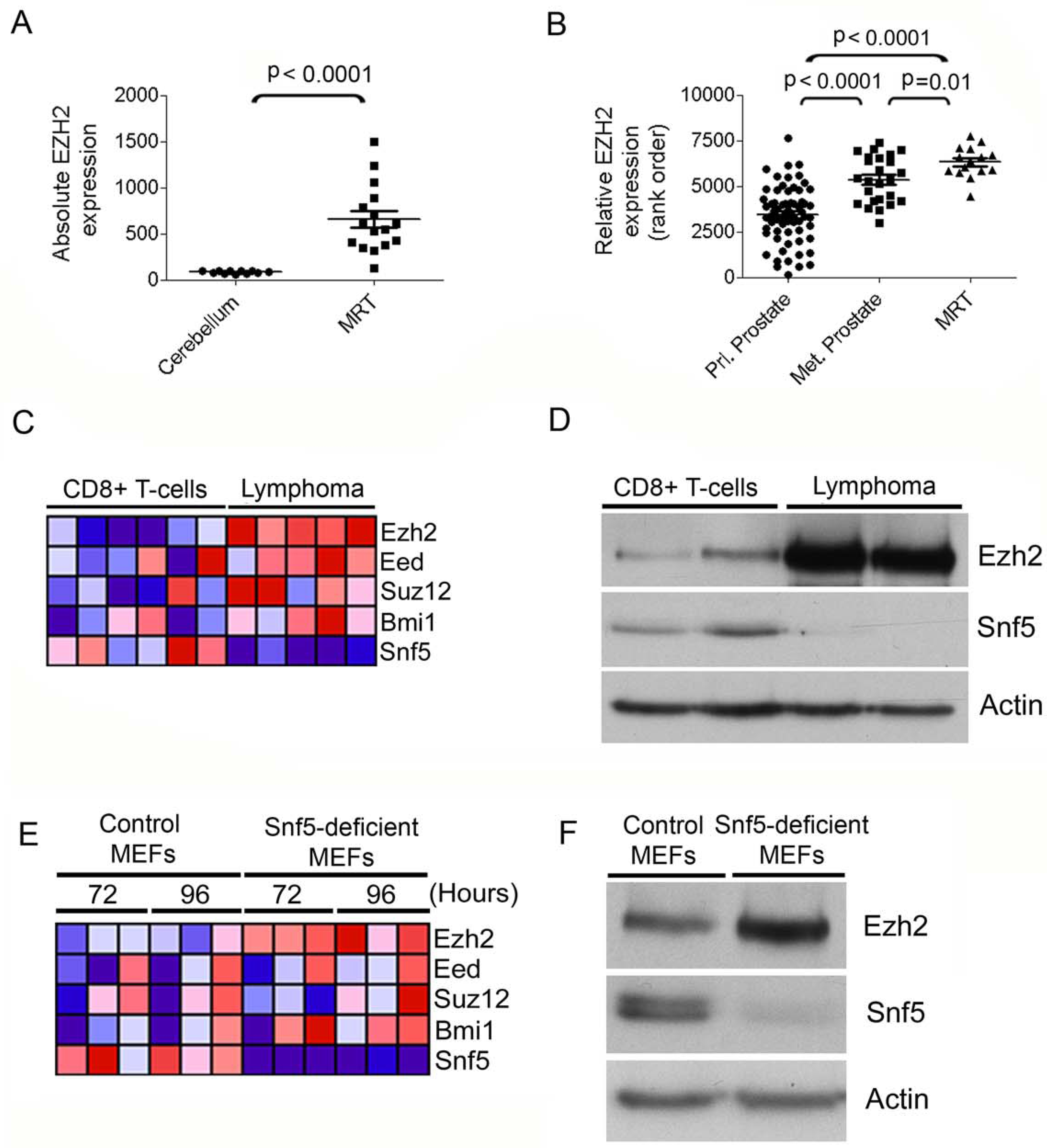

To investigate whether activation of PcG function contributes to the oncogenic drive caused by SNF5 loss, we evaluated PcG gene expression in SNF5-deficient tumors. We first examined PcG gene expression signatures from primary CNS rhabdoid tumors and cell lines compared to expression signatures from normal cerebellum. MRTs expressed higher levels of EZH2 (Figure 1A; p < 0.0001), whereas other PcG transcripts were upregulated in some samples but were not consistently affected (Figure S1A–D; EED, p = 0.54; SUZ12, p = 0.03; BMI1, p = 0.97). In order to evaluate the relative magnitude of this effect, we compared the levels of PcG transcripts in SNF5-deficient samples to prostate cancers because these tumors have been shown to express EZH2 at high levels in metastatic cancers or low levels in primary tumors (Varambally et al., 2002). We utilized previously published microarray datasets downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus database repository (GEO) (Edgar et al., 2002) and found that EZH2 was most highly expressed in MRTs exceeding even the levels in metastatic prostate cells (Figure 1B, p = 0.01; Actin control, Figure S1E). Taken together, these results reveal elevated levels of EZH2 in SNF5-deficient tumors.

EZH2 is elevated in SNF5-deficient cancers and following Snf5 inactivation in primary cells. Scatter plot of EZH2 expression in (A) primary MRT compared to normal cerebellum and (B) in MRT compared to prostate tumors. (C) Heat map showing expression of PcG transcripts in murine Snf5-deficient CD8+ T-cell lymphoma cells compared to purified wild type CD8+ T-cells. Relative expression values are normalized across each row where red indicates high level expression and blue indicates low level expression. (D) Ezh2 protein levels are elevated in Snf5-deficient lymphomas. Immunoblot analysis of Ezh2 in CD8+ T-cells compared to Snf5-deficient CD8+ lymphoma T-cells. (E) Ezh2 mRNA levels are upregulated following Snf5 inactivation in MEFs. Heat map showing expression of PcG genes following Cre-mediated excision of Snf5 in MEFs compared to control MEFs. (F) Ezh2 protein levels are upregulated following Snf5 inactivation in MEFs. Immunoblot analysis of Ezh2 and Snf5 from whole cell extracts derived from control MEFs or Snf5-deficient MEFs. Actin is used as a loading control. See also Figure S1.

We next sought to determine whether PcG genes were also upregulated in primary tumors that arise following conditional inactivation of Snf5 in the mouse T-cell lineage. In this mouse model of cancer, inactivation of Snf5 in peripheral T-cells rapidly gives rise to fully penetrant CD8+ T-cell lymphomas, thus providing a tumor model with which we could investigate functional relationships between PcG proteins and the SWI/SNF complex during oncogenic transformation (Isakoff et al., 2005; Roberts et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2009). Comparison of gene expression signatures from purified CD8+ Snf5-deficient lymphoma T-cells to wild type control CD8+ T-cells revealed markedly increased levels of the Ezh2 transcript in all lymphoma samples (Figure 1C; Figure S1F; p = 0.0002). These analyses also showed a trend toward upregulation of other PcG proteins although this was not as consistent (Figure 1C; Figure S1G–J; Eed, p = 0.19; Suz12, p = 0.08; Bmi1, p = 0.09). Ezh2 upregulation was confirmed using immunoblotting, which revealed a robust increase of Ezh2 protein in Snf5-deficient lymphomas (Figure 1D).

Snf5 directly represses Ezh2 transcription in mouse embryonic fibroblasts

To determine whether the elevated levels of Ezh2 detected in Snf5-deficient tumors was a primary effect of Snf5 inactivation, we next evaluated PcG expression in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) conditional for Snf5. We first utilized whole-genome expression data sets that we generated from Snf5-deficient MEFs compared to control MEFs to evaluate changes in PcG gene expression caused by Snf5 loss (Isakoff et al., 2005). The PcG gene Ezh2 was reproducibly upregulated in all samples following Snf5 depletion (p = 0.004), whereas, the expression of other PcG transcripts, Eed, (p = 0.50), Suz12 (p = 0.76) and Bmi1 (p = 0.15), did not show consistent patterns of upregulation (Figure 1E and Figure S1K–O). Ezh2 protein levels also increased following Snf5 inactivation (Figure 1F). To gain insight into whether the SWI/SNF complex directly regulates EZH2 expression we tested for binding of Snf5 at the genomic locus of Ezh2 in MEFs. Using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) we examined Snf5 and RNA Polymerase II occupancy at Ezh2 compared to three negative control locations and observed enrichment of Snf5 at the Ezh2 gene, but not at control genes (Figure S1P,Q).

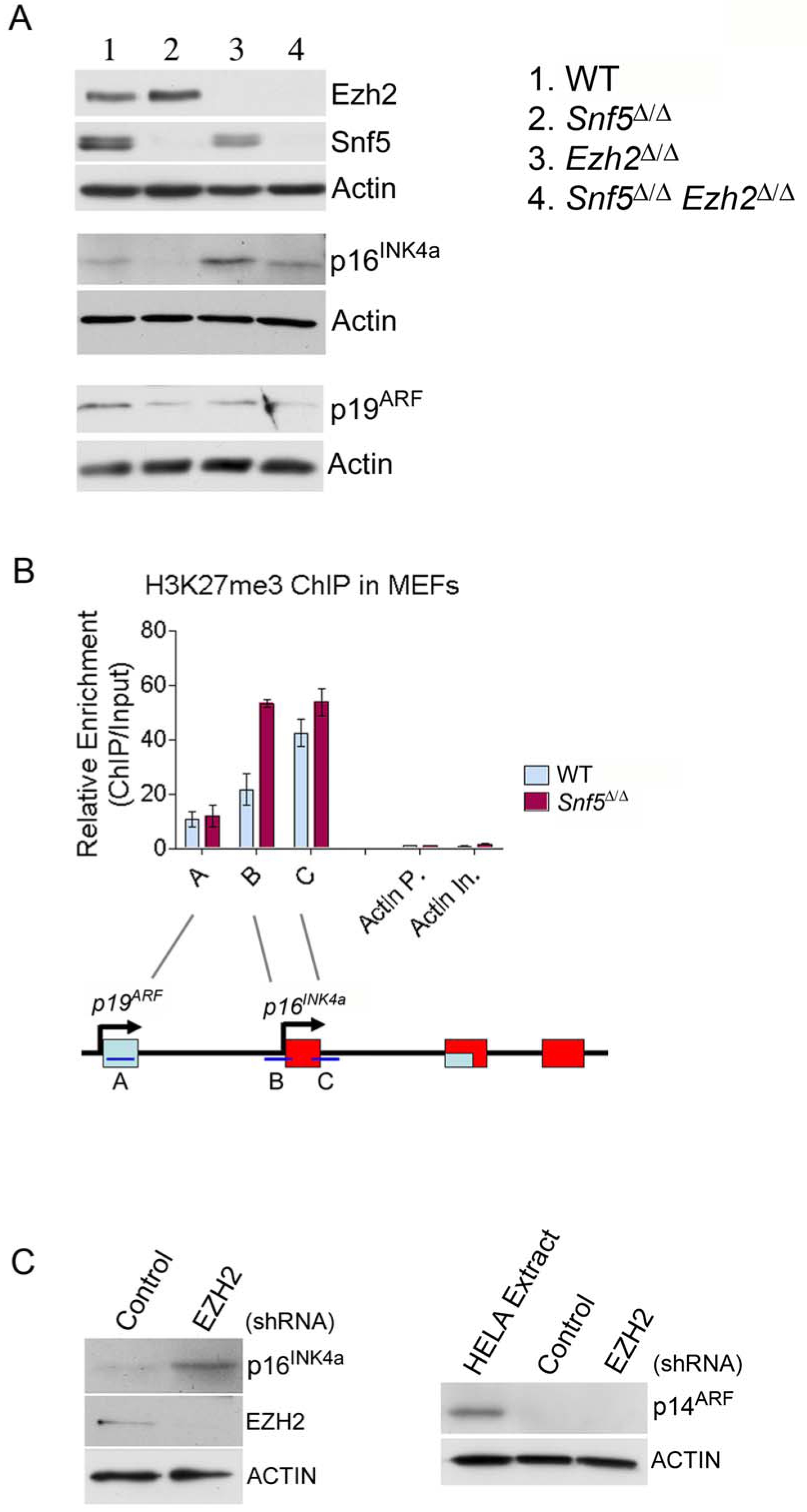

Ezh2 drives epigenetic silencing of p16INK4a following SNF5 loss

Downregulation of the p16INK4a tumor suppressor occurs following inactivation of SNF5 and may contribute to oncogenesis (Isakoff et al., 2005; Oruetxebarria et al., 2004). p16INK4a has also been shown to be a target of EZH2 and to be repressed by PcG mediated silencing (Kia et al., 2008; Kotake et al., 2007; Shen et al., 2008). Further, re-expression of SNF5 in human MRT cell lines leads to accumulation of SWI/SNF at the p16INK4a promoter and is associated with loss of PcG proteins (Kia et al., 2008). Therefore, we sought to utilize p16INK4a as a model target to investigate the functional relationship between EZH2 and SNF5 in primary cells. We crossed Snf5-conditional mice to Ezh2-conditional mice and isolated MEFs of 3 genotypes: Snf5-conditional, Ezh2-conditional and Snf5-Ezh2 doubly conditional. We evaluated p16INK4a expression after inactivation of Ezh2 or Snf5 or both. Consistent with previous reports, Snf5 inactivation alone resulted in silencing of p16INK4a (Isakoff et al., 2005). In contrast, inactivation of Ezh2 led to upregulation of p16INK4a (Figure 2A). Finally, inactivation of Ezh2 abrogated the downregulation effect of Snf5 loss upon p16INK4a expression and resulted in wild type p16INK4a levels in double deficient MEFs (Figure 2A). To test whether this antagonism was reversible, three days after inactivation of Snf5 and Ezh2, we re-introduced Snf5 and found that p16INK4a expression was restored to a high level, demonstrating reversibility (Figure S2). Since Ezh2 is thought to mediate epigenetic gene silencing through the addition of tri-methyl groups to lysine 27 of histone H3, we evaluated whether this histone modification was elevated at the p16INK4a locus after Snf5 inactivation. Using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), we quantified the relative levels of H3K27 tri-methylation at the p16INK4a locus after Snf5 inactivation in MEFs. Snf5 inactivation led to elevated levels of H3K27 trimethylation at the p16INK4a gene, consistent with a role for Ezh2 in driving epigenetic gene silencing after Snf5 inactivation (Figure 2B).

EZH2 and SNF5 have antagonistic roles in the control of expression of the model target p16INK4a. (A) Immunoblot analysis of p16INK4a and p19ARF after inactivation of Snf5 and Ezh2 in MEFs. Actin was used as a loading control. (B) ChIP analysis of H3K27me3 levels at the INK4a/ARF locus after Snf5 inactivation in MEFs. Primers were designed at the p19ARF and p16INK4a loci (primers A, B and C), as indicated in the schematic illustration in the bottom panel, and at several negative control regions (Actin promoter (Actin P.) and Actin intron (Actin In.). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM from 3 biological replicates. (C) Immunoblot analysis of p16INK4a and p14ARF after EZH2 knockdown in the G401 MRT cell line. Actin was used as a loading control. See also Figure S2.

To evaluate the relevance to human cancers, we next investigated whether EZH2 was essential for maintaining the epigenetic silencing of p16INK4a in a human SNF5-deficient MRT cell line. Using a shRNA against EZH2 we were able to achieve greater than 90% knockdown of EZH2, as determined at the protein level. Expression of the EZH2 shRNA, but not the non-silencing shRNA, led to increased expression of p16INK4a (Figure 2C), showing that EZH2 is required for epigenetic silencing of p16INK4a.

Repression of Polycomb signatures in Snf5-deficient tumors and following Snf5 inactivation in MEFs

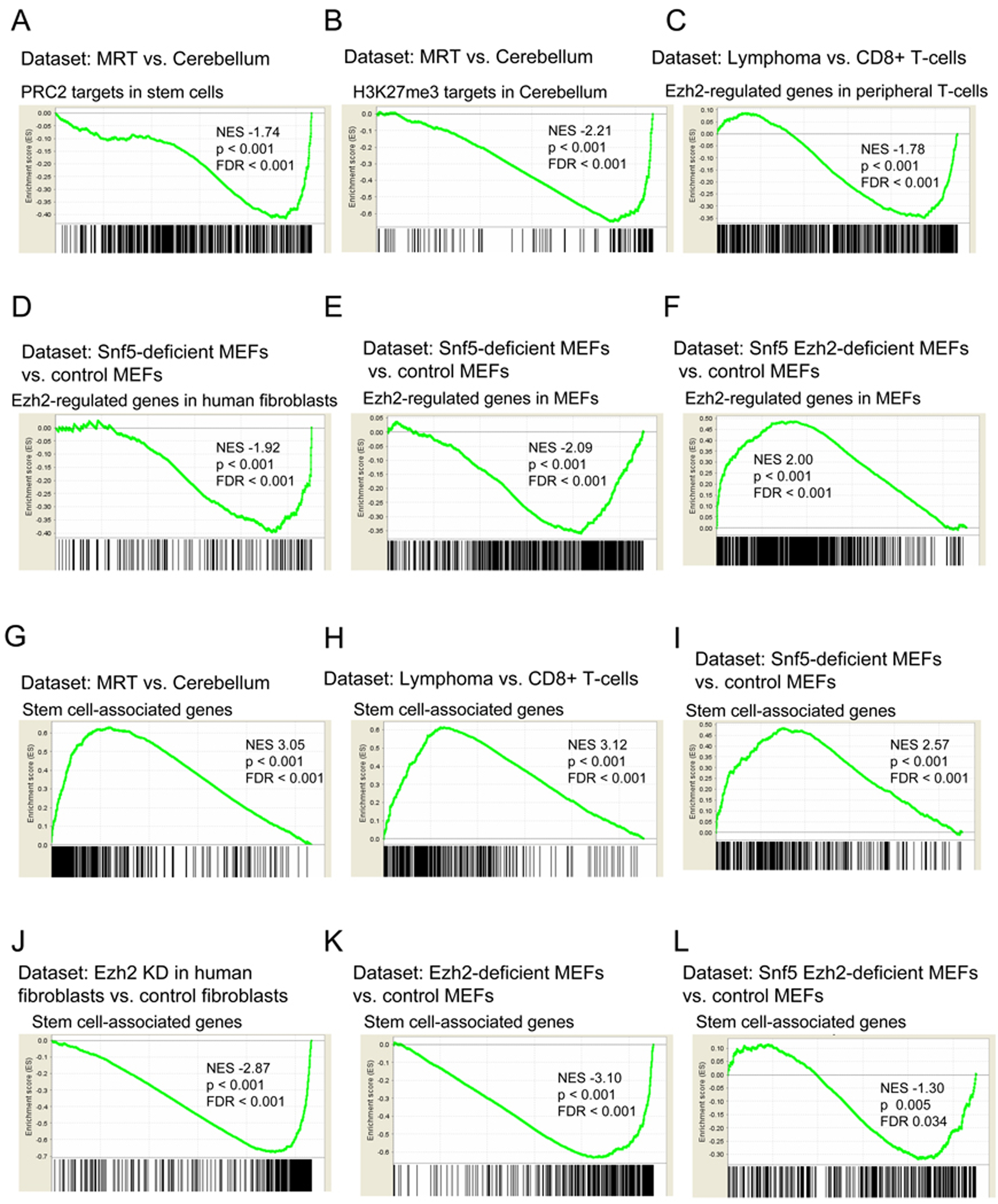

The findings at the p16INK4a locus were supportive of epigenetic antagonism between SNF5 and EZH2. However, downregulation of p16INK4a is unlikely to be the full mechanism by which SNF5 loss drives cancer formation as tumor onset occurs much more quickly, with higher penetrance, and in different a spectrum following Snf5 inactivation than p16INK4a inactivation (Krimpenfort et al., 2001; Sharpless et al., 2001). Also, humans with biallelic p16INK4a mutations are not predisposed to develop MRT (Kim and Sharpless, 2006; Roberts and Biegel, 2009). Lastly, both SWI/SNF and PcG bind the genome at many loci rather than just at p16INK4a. Consequently, we sought to determine whether the epigenetic antagonism between SNF5 and EZH2 was more broad. We began with an analysis of the expression levels of PcG targets using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA). PcG targets vary substantially by lineage, and as the cell of origin of MRTs is unknown but the tumors are poorly differentiated, we chose to utilize a gene set of PcG targets that had been defined in embryonic stem cells (Ben-Porath et al., 2008). We found that these PRC2 targets were downregulated in MRTs compared to normal brain (Figure 3A; p < 0.001). Consistent with this, a gene set consisting of H3K27me3 modified targets defined from embryonic stem cells (Ben-Porath et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2006) was similarly negatively enriched in rhabdoid tumors (Figure S3A; p < 0.001). We next used a gene set that we generated by performing ChIP-chip of H3K27me3 from primary murine cerebellum to identify H3K27me3 bound targets that were expressed to some degree to determine whether this gene set was downregulated in SNF5-deficient rhabdoid tumors. These genes were even more strongly downregulated in MRTs (Figure 3B; p < 0.001).

SNF5 loss leads to broad repression of PcG targets and activation of stem cell-associated programs. GSEA is a method that determines whether a set of genes shows differences between two biological states. The normalized enrichment score (NES) reflects the degree to which a gene set is upregulated (positive NES) or downregulated (negative NES). Corresponding p-values are indicated. (A)GSEA of PRC2 targets from stem cells (Ben-Porath et al., 2008) and (B) H3K27me3 enriched genes from cerebellum in expression data from human MRT samples compared to normal cerebellum. (C) GSEA of T-cell specific Ezh2-regulated genes (Su et al., 2005) in expression data from purified CD8+ Snf5-deficient lymphomas compared to CD8+ T-cells purified from a wild type mouse. (D) GSEA of human-fibroblast specific EZH2-regulated genes (Bracken et al., 2006) and (E) MEF-specific EZH2-regulated genes in expression data from Snf5-deficient MEFs compared to control MEFs. (F) GSEA of MEF-specific EZH2-regulated genes in expression data from Snf5 Ezh2-deficient MEFs compared to control MEFs. (G) GSEA of stem cell associated-program in expression data from human MRT samples compared to normal cerebellum, (H) purified CD8+ Snf5-deficient lymphomas compared to CD8+ T-cells purified from a wild type mouse, (I) Snf5-deficient MEFs compared to control MEFs, (J) human fibroblasts where EZH2 levels have been knocked down compared to control fibroblasts, (K) Ezh2-deficient MEFs compared to control MEFs, and (L) Snf5 Ezh2-deficient MEFs compared to control MEFs. The stem cell-associated expression signatures (Ben-Porath et al., 2008; Wong et al., 2008) and EZH2 knock down expression data (Bracken et al., 2006) were previously published. See also Figure S3. Gene sets are listed in Table S1.

We next turned to our conditional mice to determine whether the cancers caused by ablation of Snf5 in this model system displayed similar alterations in PcG target genes. We thus examined the expression of a gene set consisting of genes regulated by Ezh2 within the T-cell lineage (Su et al., 2005) and found that they are also repressed in Snf5-deficient CD8+ T-cell lymphomas compared to normal CD8+ T-cells (Figure 3C; p < 0.001,).

A key question is whether repression of PcG regulated genes is simply a consequence of oncogenic transformation or whether it is a primary consequence of Snf5 inactivation. We therefore utilized Snf5-conditional embryonic fibroblasts to evaluate the effect of Snf5 inactivation upon PcG regulated gene expression in primary non-transformed cells. We found that a gene set consisting of genes regulated by EZH2 in human fibroblasts (Bracken et al., 2006) was repressed following Snf5 inactivation in MEFs (Figure 3D; p < 0.001). We next utilized our Ezh2 conditional MEFs to identify an independently derived set of Ezh2 regulated genes (Table S1) and found that this gene set was also downregulated in Snf5-deficient MEFs (Figure 3E; p < 0.001). To evaluate specificity and to rule out a general repressive effect caused by Snf5 inactivation, we examined expression of Ezh2 regulated genes from an unrelated differentiated lineage, T- cells, and found them not to be repressed following Snf5 inactivation in MEFs (Figure S3B) indicating lineage specificity. Lastly, we analyzed MEFs derived from Snf5fl/fl-Ezh2fl/fl double conditional embryos and found that the absence of Ezh2 indeed blocked the downregulation of these targets otherwise caused by Snf5 inactivation (Figure 3F). Taken together, these results show that Snf5 inactivation leads to broad repression of lineage-specific PcG regulated genes and that this repression is dependent upon the presence of Ezh2.

Snf5 inactivation causes elevated levels of H3K27me3 at lineage-specific PcG targets

The antagonism between Snf5 and Ezh2 in the control of gene expression programs prompted us next to investigate the underlying mechanism by using ChIP to test whether increased levels of histone H3K27 trimethylation were present. We thus performed ChIP-PCR for H3K27me3 from both Snf5-deficient CD8+ T-cell lymphomas and from wild type CD8+ T-cells to ask whether increased levels of H3K27me3 were present at genes downregulated by Snf5. We tested 25 downregulated and 5 non-downregulated control genes. Eighteen of the 25 experimental genes demonstrated statistically significant increases in H3K27me3 in the Snf5-deficient lymphomas; an additional 4 of the 25 genes had increased H3K27me3 levels but were not statistically significant; 2 of the 25 genes were unchanged and only 1 of the 25 displayed reduced levels of H3K27me3 in the lymphoma (Figure 4A). In contrast, H3K27me3 levels were not significantly altered in any of the 5 control genes. Consequently, increased levels of H3K27me3 are present at the promoters of genes downregulated in Snf5-deficient lymphomas.

Elevated levels of Ezh2 and H3K27me3 at PcG target genes following Snf5 loss. (A) ChIP analysis of H3K27me3 in Snf5-deficient lymphomas compared to wild type CD8+ T-cells. The experimental genes represent a random set of genes downregulated in Snf5-deficient lymphomas whereas the control genes are a random set expressed in both CD8+ T-cells and lymphomas. Relative enrichment is calculated by dividing the H3K27me3 enrichment to input DNA after normalization to a negative binding region in an Actb intron. Data are represented as mean +/− SEM from three biological replicates. * = p < 0.05. GSEA enrichment plot of H3K27me3 modified genes in wild type MEFs in expression data from (B) Ezh2-deficient MEFs, (C) Snf5-deficient MEFs or (D) Snf5 Ezh2-deficient MEFs. (E) GSEA enrichment plot of a random set of non-H3K27me3 genes in expression data from Snf5-deficient MEFs. (F) H3K27 ChIP-chip at individual gene promoters displayed using the Affymetrix Integrated Genome Browser. (G) H3K27me3 and Ezh2 ChIP-chip signal intensities near the transcription start sites (TSS) of 85 genes most significantly upregulated in Ezh2−/− MEFs and (H) 132 randomly chosen control repressed genes not altered in Snf5-deficient or Ezh2-deficient expression data. See also Figure S4.

We next investigated whether increased H3K27 trimethylation and elevated levels of Ezh2 were directly contributing to changes in gene expression programs following Snf5 inactivation in the MEF model system. We utilized ChIP-chip to define a set of 508 high confidence genes bound by H3K27me3 modified histones in wild type MEFs and then evaluated how this gene set was affected by inactivation of Ezh2 and Snf5. Examination of the list revealed several gene families including Hox, Pax and Fox genes that have previously been shown to be regulated by PcG proteins (Bracken et al., 2006) (Table S1). As expected, given that Ezh2 and the PRC2 complex trimethylate H3K27, these targets were up-regulated in Ezh2 deficient MEFs (Figure 4B). In contrast, Snf5 inactivation led to further downregulation of the targets (Figure 4C). Co-inactivation of Ezh2 blocked the downregulation of these genes otherwise caused by Snf5 loss, demonstrating an essential role for Ezh2 in this process (Figure 4D). Of note, the effects of Snf5 inactivation were specific as genes not bound by H3K27me3 modified histones in wild type MEFs were not downregulated (Figure 4E). We next evaluated the effect of Snf5 inactivation upon the prevalence of genes modified by H3K27me3 and found that it led to a 1.9 fold increase (Figure S4).

To gain insight into levels of H3K27me3 at specific genes we evaluated its density at promoters. Interestingly, while a 2-fold elevation of H3K27me3 was present at p16Ink4a, the effect was even more pronounced at numerous other targets (Figure 4F). At a few polycomb targets, such as Hoxb1, there appeared to be minimal change (Figure 4F). To evaluate the effect of Snf5 loss upon Ezh2 targets overall, we examined the set of genes that are upregulated following Ezh2 inactivation. Inactivation of Snf5 led to increased signal intensity of both H3K27me3 and Ezh2 binding overlying the TSS and upstream portion of these genes (Figure 4G), an effect not seen at control genes such as actin and Rps8 (Figure 4F) or at a randomly chosen set of repressed genes not expressed in wild type MEFs (Figure 4H).

Balanced expression of stem cell-associated programs by Ezh2 and Snf5

We next sought to investigate the mechanistic basis by which disruption of the SNF5-PcG balance drives oncogenic transformation. PcG genes have been implicated in the control of stem cell identity via the repression of lineage-specific targets (Boyer et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2006). Similarly, the SWI/SNF complex has recently been implicated in the control of stem cell self-renewal and pluripotency (Ho et al., 2009; Kidder et al., 2009). It has been proposed that oncogenic transformation may depend upon aberrant ectopic activation of stem cell-related self-renewal programs (Ben-Porath et al., 2008; Wong et al., 2008). Therefore, we evaluated the expression gene signatures associated with identity of embryonic stem cells in Snf5-deficient tumors. We utilized previously published embryonic stem cell-associated gene sets and found that these genes are significantly upregulated in both human MRTs (p < 0.001) and in murine Snf5-deficient lymphomas (p < 0.001)((Figure 3G,H and S3C,D)(Wong et al., 2008) (Ben-Porath et al., 2008). As a higher fraction of tumor cells than control cells are proliferating, we sought to determine whether proliferation associated genes were driving this enrichment. Therefore, we used a previously published “proliferation-corrected” gene set from which the proliferation associated genes had been removed (Somervaille et al., 2009). Significant enrichment remained intact using this gene set as well (MRT, p < 0.001; Snf5-deficient lymphomas, p < 0.001, Figure S3E,F). Again, we sought to determine whether activation of the stem cell-associated signature was simply a secondary consequence of oncogenic transformation or whether it was a primary effect due to Snf5 loss. Therefore, we examined the expression of these gene sets in Snf5-conditional MEFs and found enrichment of both the stem cell-associated signatures (p < 0.001) and proliferation deficient stem cell-associated signatures (p < 0.001) in Snf5-deficient MEFs (Figure 3I, S3G,H). Consequently, the upregulation of stem cell-like programs occurs in primary cells following Snf5 depletion and is not simply a consequence of transformation.

We next evaluated whether the gene expression signatures associated with stem cells were oppositely regulated by EZH2. To test this we examined the expression of these gene signatures in previously published microarray data from human embryonic fibroblasts in which EZH2 had been knocked down (Bracken et al., 2006). We found that the stem cell-associated signatures and a proliferation-deficient stem cell-associated signature were downregulated following EZH2 knockdown in primary cells, an effect opposite to that caused by Snf5 loss (Figure 3J, S3I,J). We next utilized our Ezh2-conditional MEFs and similarly found that these stem cell-associated signatures were downregulated following Ezh2 inactivation (Figure 3K, S3K,L). Finally, we utilized MEFs from Snf5fl/fl-Ezh2fl/fl double conditional embryos and found that inactivation of Ezh2 entirely blocked enrichment of the stem cell-associated signature otherwise caused by Snf5 loss (Figure 3L, S3M,N).

Ezh2 is required for growth of SNF5-deficient tumor cells

The antagonism between SNF5 and EZH2 in the control of gene expression prompted us to ask whether PcG activity is a key driver of oncogenic transformation following Snf5 loss. We began by evaluating the effect of EZH2 knockdown in human SNF5-deficient MRT lines and found that shRNA-mediated knockdown of EZH2 caused a decrease in cell proliferation (Figure 5A, S5). To confirm that the slowed proliferation was not due to off-target effects conferred by expressing the shRNA we monitored proliferation after knocking down EZH2 using a different system. We transiently transfected a smartpool of siRNAs that target EZH2 and then monitored growth by counting cells after 72 hours. Using this siRNA-mediated technology we were also able to achieve greater than 90% knockdown of EZH2 and similarly observed a reproducible reduction in proliferation compared to cells that were treated with control siRNAs (Figure 5B). Thus, EZH2 is required for proliferation of SNF5-deficient cancer cells.

EZH2 is required for the proliferation of MRT cell lines. (A) Slowed proliferation of the G401 MRT cell line after EZH2 knockdown using shRNAs. Immunoblotting was used to determine the efficiency of EZH2 knockdown. Cell proliferation was determined using the WST-1 cell proliferation reagent. Data are represented as mean +/− SEM from 3 biological replicates. (B) Slowed proliferation of the G401 MRT cell line after EZH2 knockdown using siRNAs. Immunoblotting was used to determine the efficiency of EZH2 knockdown. Cells were counted 72 hours after treatment with the indicated siRNAs. Data are represented as mean +/− SEM from 3 biological replicates. *p = 0.01. (C) The reduced proliferation after shRNA mediated knockdown of EZH2 is not due to apoptosis. Apoptosis in EZH2 knockdown or control is measured via PARP1 cleavage. HeLa cells treated with doxyrubicin were used as a positive control for PARP1 cleavage. (D) EZH2 knockdown leads to cellular senescence. Cellular senescence was determined by measuring the expression of β-galactosidase. See also Figure S5.

To gain further insight into how EZH2 is driving tumor formation, we next evaluated whether the decreased proliferation following EZH2 knockdown was a result of either apoptosis or cellular senescence. While EZH2 knockdown revealed no detectable apoptotic phenotype as measured by cleavage of PARP1 (Figure 5C), a significant increase in senescence-associated β-galactosidase expression was detected (Figure 5D). Further, these cells were larger and flatter, consistent with senescent morphology. These results suggested that EZH2 contributes to tumorigenesis, at least in part, by preventing the activation of cellular senescence.

Ezh2 is essential for tumor formation in vivo

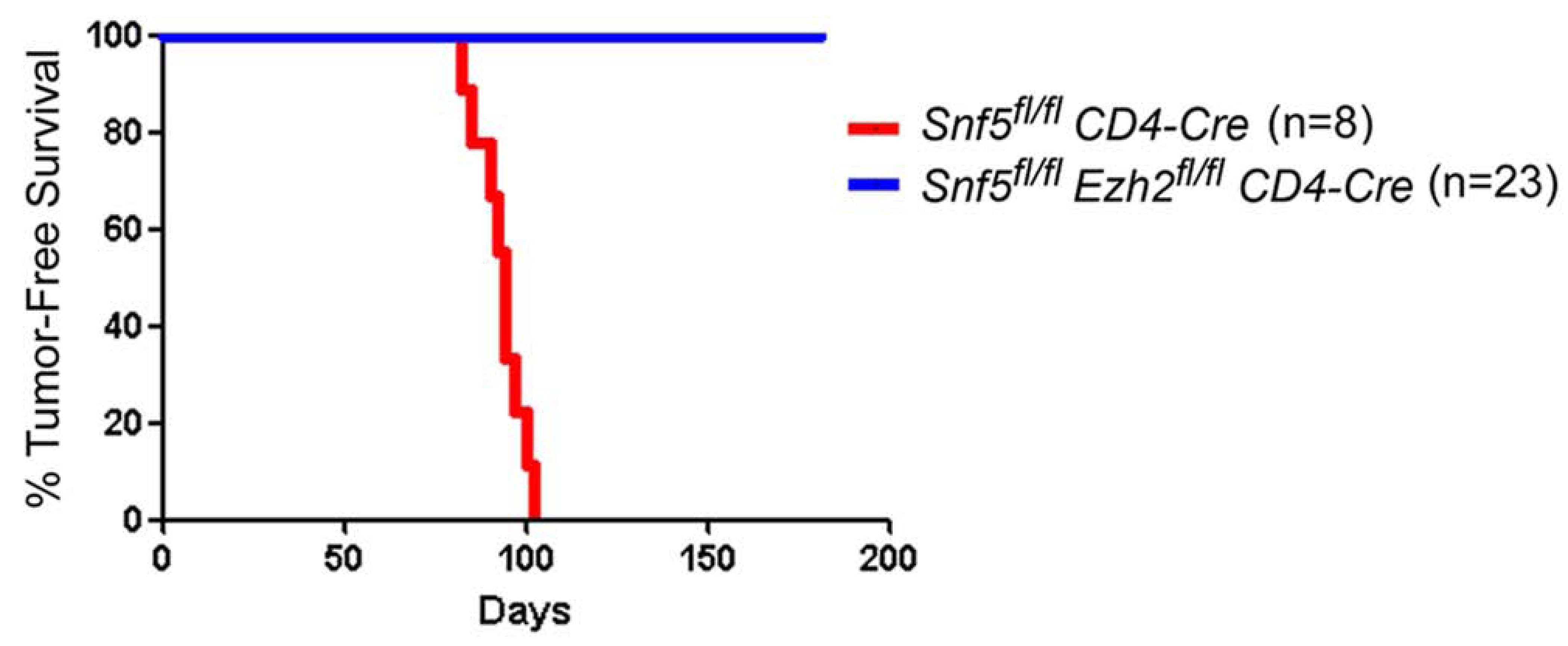

Given our results thus far, we hypothesized that imbalanced function between EZH2 and SNF5 might serve crucial roles in driving tumor formation. Therefore, we sought to test in vivo, using a formal genetic approach, whether inactivating Ezh2 could rescue the tumor phenotype conferred by Snf5 inactivation in the T-cell lineage. Importantly, inactivation of Snf5 in peripheral T-cells confers rapid onset of mature CD8+ T-cell lymphomas in 100% of the mice, thus allowing us to quickly investigate contributions of Ezh2 to oncogenesis in vivo (Roberts et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2009). Therefore, we interbred Snf5 and Ezh2 conditional mice in the presence of the CD4-Cre transgene and evaluated whether inactivation of Ezh2 would ameliorate the phenotypes caused by Snf5 loss in this lineage. While inactivation of Snf5 leads to a block in development and a reduction in peripheral T-cell numbers to 30% of wild type (Figure 6A,B)(Roberts et al., 2002), Ezh2 inactivation had no effect upon the number or distribution of peripheral T-cells (Figure 6A,B), consistent with previous studies (Su et al., 2005). We aged cohorts of CD4-Cre expressing Snf5fl/fl, Ezh2fl/fl and Snf5fl/fl-Ezh2fl/fl double conditional mice to monitor for tumor onset. Strikingly, while Snf5 inactivation led to fully penetrant and rapid tumor formation (Figure 6C), inactivation of Ezh2 completely blocked tumor onset driven by Snf5 loss (Figure 7).

Ezh2 is dispensable for peripheral T-cell development. (A) The distribution of peripheral T-cells is unaffected by Ezh2 inactivation. Flow cytometry analysis of the CD3 T-cell marker on spleen cells isolated from mice of the indicated genotypes. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of CD8+ cells, the population from which Snf5-deficient lymphomas ultimately arise, in the spleen from mice of the indicated genotype. (C) An older CD4-Cre Snf5fl/fl mouse in which a lymphoma has developed showing the CD8+ lymphoma population on flow cytometry and gross images of spleens isolated from a wild type mouse (control) or lymphoma-bearing mouse.

Discussion

Epigenetics in tumor development

Epigenetic alterations likely contribute to the formation of most, if not all cancers. However, in the setting of genomic instability it is difficult to evaluate the contributions of epigenetic changes as it is unclear which are primary drivers and which arise as secondary passengers due to instability (McKenna and Roberts, 2009). We recently showed that SNF5-deficient cancers, both in humans and mice, are diploid and genomically stable, demonstrating that disruption of this chromatin remodeling complex can substitute for chromosomal instability in the genesis of aggressive, lethal cancers (McKenna et al. 2008). Further, this suggests that epigenetic alterations play a central role in driving the formation of these malignancies. Given that they are initiated by perturbation of a chromatin remodeling complex, their rapid onset, aggressive nature and genomic stability, SNF5-deficient tumors constitute an ideal system with which to evaluate the epigenetic mechanisms that drive cancer formation.

While previous studies have demonstrated antagonism between PcG proteins and the SWI/SNF complex in regulating Hox gene expression in Drosophila, the extent of this relationship in mammalian development and disease has remained uncertain (Tamkun et al. 1992; Kennison 1995). Our studies show this epigenetic relationship is broad based in mammalian cells and demonstrate that balanced function between SWI/SNF and PcG serves to prevent tumor formation. As SWI/SNF is capable of displacing PcG proteins from the INK4a/ARF locus, our findings are consistent with a model where SWI/SNF and PcG complexes bind mutually exclusive of one another, a model supported by non-overlapping binding profiles on polytene chromosomes and from genome-wide localization studies in mammalian embryonic stem cells (Armstrong et al. 1998; Kia et al. 2008a; Ho et al. 2009; Kidder et al. 2009). Consequently, the antagonistic relationship between PcG proteins and the SWI/SNF complex also serves important roles in preventing tumor formation in mammals and is a critical component of tumor formation following Snf5 loss.

EZH2 and oncogenesis

Accumulating evidence has suggested that EZH2 contributes to cancer formation. This evidence comes from studies examining the expression of EZH2 in different tumors, where the highest levels correlate with the most aggressive tumors and the worst prognosis (Sparmann and van Lohuizen 2006; Simon and Lange 2008). Additional studies in a variety of tumor cell lines have shown that reducing the levels of EZH2 leads to slowed proliferation and a decreased capacity to form tumors when transplanted into mice, leading to the proposal of Ezh2 as a possible therapeutic target (Bracken et al., 2003; Croonquist and Van Ness, 2005; Kleer et al., 2003; Simon and Lange, 2008; Varambally et al., 2002). However, it has remained unclear whether hyperactivation of EZH2 has roles in the initiation and maintenance of primary cancers in vivo and whether targeted inactivation of EZH2 or its downstream function would be therapeutically useful. Using an in vivo cancer model, we show that inactivation of Ezh2 is sufficient to block tumor formation that occurs after Snf5 loss. A formal possibility is that Ezh2 could be an essential gene whose absence prevents cell growth. Several lines of evidence argue against this and for a specific relationship between PcG and SWI/SNF. First, as noted above, PcG and SWI/SNF serve antagonistic roles in control of Hox gene expression (Tamkun et al. 1992; Kennison 1995). Second, PcG blocks chromatin remodeling mediated by SWI/SNF in in vitro assays (Francis et al., 2001; Shao et al., 1999). Third, re-expression of SNF5 leads to PcG eviction from the INK4a/ARF locus (Kia et al., 2008). Fourth, Ezh2 loss does not have a negative effect upon T-cell number in vivo (Su et al., 2005). Lastly, we have found that the effects of Ezh2 inactivation in vivo to be quite specific. For instance, in a model of osteosarcoma, Ezh2 is largely dispensable for bone development and Ezh2 inactivation does not ablate cancer formation (J. Perry and S. Orkin, unpublished communication). Consequently, EZH2 does not serve an essential role in all cancers but rather likely drives cancer formation via specific activation.

Our results also provide mechanistic insight into the regulation of EZH2 expression. The SWI/SNF complex is thought to regulate activation or repression of genes via alterations in nucleosome positioning. Our work shows that Snf5 binds directly to the Ezh2 promoter and serves to prevent high-level expression. That Snf5 is an important regulator of Ezh2 expression is also supported by genome-wide ChIP-Chip analyses of Brg1 binding in embryonic stem cells where it was found that Ezh2 is a target of the SWI/SNF complex (Ho et al. 2009). Thus, our work establishes that Ezh2 is bound and regulated by Snf5, and required for tumor formation after Snf5 loss. In addition to Ezh2, several other PcG genes including Suz12, Eed, and Bmi1 are bound by Brg1 in embryonic stem cells, and these genes are also upregulated in some primary human cancers lacking SNF5, although to a lesser degree than EZH2. Therefore, SNF5 inactivation may lead to overexpression of other PcG genes which also contribute to oncogenesis. Indeed, while clear evidence linking SUZ12 and EED to oncogenic transformation is still lacking, BMI1 has been shown to possess clear oncogenic properties (Sparmann and van Lohuizen 2006; Simon and Lange 2008). Collectively, our work establishes that the regulatory relationship between SWI/SNF and PcG complexes extends across multiple cell types and that perturbation of this relationship can contribute to disease.

Hyperactivated stem cell-associated programs: a potential mechanism underlying tumors that arise following Snf5 inactivation or overexpression of PcG proteins

Stem cell-associated signatures have recently been found to be enriched in tumors with more aggressive behavior and poorer prognosis (Ben-Porath et al., 2008; Wong et al., 2008). While these signatures are upregulated in many cancers and are an important contributing factor during oncogenic transformation, the mechanisms underlying specific activation of these programs are not well understood. PcG proteins have a dynamic role in safeguarding stem cell identity by maintaining the repression of lineage-specific genes, and hyperactive PcG function may drive tumorigenesis through the repression of lineage-specific genes and reversion to a more stem cell like fate associated with an increased capacity for self-renewal and proliferation. The SWI/SNF complex has roles in lineage-specific differentiation and perturbations in SWI/SNF activity block differentiation, and thus may force cells to retain properties of a stem cell. Furthermore, while PcG and SWI/SNF complexes have opposing functions in the regulation of Hox gene expression in Drosophila, it is not clear whether this antagonistic relationship exists broadly during development or in the regulation of genetic programs in stem cells. Our results show stem cell-associated signatures are enriched in SNF5-deficient cancers and most importantly that Snf5 inactivation leads to upregulation of stem cell-associated programs in primary, untransformed cells. This thus identifies SNF5 as a key regulator of these genetic signatures. Conversely, PcG proteins regulate genetic programs in stem cells and PcG overexpression has been shown to promote increased proliferation and contribute to oncogenic transformation. We show that reduction of Ezh2 levels in primary cells leads to downregulation of stem cell-associated signatures, demonstrating antagonistic effects of Snf5 and Ezh2 upon stem cell-associated programs. Lastly, we show that activation of the stem cell-associated signature caused by Snf5 loss is dependent upon the presence of Ezh2. Collectively, our studies establish SNF5 as a regulator of stem cell-associated programs, show opposing functions for SWI/SNF and Polycomb in the regulation of these programs, and raise the possibility that imbalanced regulation of stem cell-associated programs maybe a key mechanism leading to oncogenesis following overexpression of EZH2 or SNF5 inactivation.

Targeted therapy of EZH2

Our results may be therapeutically relevant to tumors caused by inactivation of SNF5 by providing an in vivo model cancer system with which to test novel Ezh2 inhibitors, and may additionally be applicable to the wide variety of cancers in which EZH2 is over-expressed. Most cancers caused by SNF5 loss are aggressive and respond poorly to current therapies. For example, despite intensive therapy most children affected with atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor of the CNS, a highly malignant neoplasm driven by inactivation of SNF5, die within a year of diagnosis (Chi et al., 2009). Thus, more effective treatments are needed. Unlike genetic mutations, which in the context of cancer are essentially irreversible, epigenetic modifications are reversible and thus represent attractive targets for intervention. Our results suggest that targeted inactivation of EZH2, or alternatively blockade of the epigenetic changes driven by EZH2, may be effective in the treatment of patients bearing tumors driven by SNF5 inactivation.

Experimental Procedures

Snf5 and Ezh2 inactivation and EZH2 knockdown

Excision of Snf5 and Ezh2 in MEFs was carried out as previously described (Isakoff et al., 2005; McKenna et al., 2008). EZH2 knockdown was achieved using siRNAs and shRNAs targeting EZH2. For details regarding EZH2 knockdown and cell culture experiments see supplemental procedures.

Immunoblots

The following antibodies were used: SNF5 (Bethyl, A301-087A), EZH2 (Cell Signalling; 3147), Actin-HRP (Abcam; 20272-200), p16INK4a (Santa Cruz sc-1207 and sc-468), p19ARF (Bethyl; A300-340A and Novus; NB200-106), PARP1 (Cell signaling; 9542), and HRP conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch). For details see supplemental procedures.

Murine models

All mouse experiments adhere to guidelines at the Animal Resources Children’s Hospital (ARCH) at the Children’s Hospital in Boston and have been approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Chromatin Immuoprecipitation and ChIP-chip

A two-step crosslinking method was done for the Snf5 ChIP according to (Nowak et al., 2005) with some slight modifications. The Bethyl, A301-087A Snf5 antibody, was used. p-values were determined using a paired t-test. The H3K27me3 and Ezh2 ChIP experiments were performed similarly to the above method using the H3K27me3 antibody (Upstate; 07-449) or the Ezh2 antibody (Millipore; 17-662) and a one-step crosslinking method where formaldehyde (1%) was added directly to the culture media and incubated for 10 minutes at 37C. p-values were determined using an unpaired t-test for the H3K27me3 ChIP experiments in lymphoma and CD8+ T-cell samples. In MEFs, MAT scores for all densely tiled genes at a region −500 and +2500 of the TSS were calculated. Differences between H3K27me3 enrichment in Snf5-deficient and WT MEFs were normally distributed (mean = 0.09). p-values were calculated as P(X > x) where X is the difference in MAT scores and x is the difference for the indicated gene. For details see supplemental procedures.

Gene expression data

Whole genome expression analyses from Snf5-deficient lymphomas, Ezh2-deficient MEFs and Snf5 Ezh2-deficient MEFs were generated as previously described (Isakoff et al., 2005). Expression data sets were analyzed using the Gene Pattern data analysis software (Reich et al., 2006). GSEA was performed as described previously (Subramanian et al., 2005). For details regarding the generation and analysis of whole-genome expression data see supplemental procedures.

Model: Epigenetic antagonism between EZH2 and SNF5 during oncogenesis. (A) Antagonism of Polycomb target expression by SWI/SNF and PRC2. SNF5 also negatively regulates EZH2 function by modulating its expression. (B) Perturbations in SWI/SNF activity lead to oncogenesis via imbalanced PRC2 activity, aberrant epigenetic silencing of Polycomb targets and upregulation of stem cell-associated programs.

Acknowledgements

Grant support was from the American Cancer Society New England Division-SpinOdyssey Postdoctoral Fellowship #PF-07-261-01-DDC from the American Cancer Society and the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award Fellowship 1 F32 CA130312-01A1 from the National Cancer Institute (B. Wilson). This work was supported in part by a U01 NCI Mouse Models of Cancer Consortium Award (S.H. Orkin and C.W.M Roberts) and a PHS award R01CA113794 (C.W.M. Roberts). C.W.M. Roberts is a recipient of an Innovative Research Grant from Stand Up 2 Cancer. The Garrett B. Smith Foundation, the Claudia Adams Barr Foundation, the Sarcoma Foundation of America (C.W.M.Roberts), and a R01 CA109467 research project grant (S.L. Pomeroy) provided additional support. S.H. Orkin is an Investigator of the HHMI.

We thank Jen Perry for helpful discussions and permission to cite unpublished data. We also thank Pablo Tamayo for help with cross-platform analysis of microarray data, Pengcheng Zhou for isolation of murine cerebellum cells and David James for the BT16 cell line.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Accession number

Whole-genome expression and ChIP-chip data are deposited in the GEO data repository (accession number GSE23659).

References

- Ben-Porath I, Thomson MW, Carey VJ, Ge R, Bell GW, Regev A, Weinberg RA. An embryonic stem cell-like gene expression signature in poorly differentiated aggressive human tumors. Nature genetics. 2008;40:499–507. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer LA, Plath K, Zeitlinger J, Brambrink T, Medeiros LA, Lee TI, Levine SS, Wernig M, Tajonar A, Ray MK, et al. Polycomb complexes repress developmental regulators in murine embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2006;441:349–353. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Bracken AP, Dietrich N, Pasini D, Hansen KH, Helin K. Genome-wide mapping of Polycomb target genes unravels their roles in cell fate transitions. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1123–1136. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Bracken AP, Helin K. Polycomb group proteins: navigators of lineage pathways led astray in cancer. Nature reviews. 2009;9:773–784. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Bracken AP, Pasini D, Capra M, Prosperini E, Colli E, Helin K. EZH2 is downstream of the pRB-E2F pathway, essential for proliferation and amplified in cancer. Embo J. 2003;22:5323–5335. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Chi SN, Zimmerman MA, Yao X, Cohen KJ, Burger P, Biegel JA, Rorke-Adams LB, Fisher MJ, Janss A, Mazewski C, et al. Intensive multimodality treatment for children with newly diagnosed CNS atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:385–389. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Croonquist PA, Van Ness B. The polycomb group protein enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH 2) is an oncogene that influences myeloma cell growth and the mutant ras phenotype. Oncogene. 2005;24:6269–6280. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic acids research. 2002;30:207–210. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Francis NJ, Saurin AJ, Shao Z, Kingston RE. Reconstitution of a functional core polycomb repressive complex. Mol Cell. 2001;8:545–556. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Guidi CJ, Sands AT, Zambrowicz BP, Turner TK, Demers DA, Webster W, Smith TW, Imbalzano AN, Jones SN. Disruption of Ini1 leads to peri-implantation lethality and tumorigenesis in mice. Molecular & Cellular Biology. 2001;21:3598–3603. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ho L, Ronanx JL, Wu J, Staahl BT, Chen L, Kuo A, Lessard J, Nesvizhskii AI, Ranish J, Crabtree GR. An embryonic stem cell chromatin remodeling complex, esBAF, is essential for embryonic stem cell self-renewal and pluripotency. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:5181–5186. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Isakoff MS, Sansam CG, Tamayo P, Subramanian A, Evans JA, Fillmore CM, Wang X, Biegel JA, Pomeroy SL, Mesirov JP, Roberts CW. Inactivation of the Snf5 tumor suppressor stimulates cell cycle progression and cooperates with p53 loss in oncogenic transformation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:17745–17750. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PA, Baylin SB. The epigenomics of cancer. Cell. 2007;128:683–692. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kennison JA. The Polycomb and trithorax group proteins of Drosophila: trans-regulators of homeotic gene function. Annu Rev Genet. 1995;29:289–303. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kennison JA, Tamkun JW. Dosage-dependent modifiers of polycomb and antennapedia mutations in Drosophila. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1988;85:8136–8140. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kia SK, Gorski MM, Giannakopoulos S, Verrijzer CP. SWI/SNF mediates polycomb eviction and epigenetic reprogramming of the INK4b-ARF-INK4a locus. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:3457–3464. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kidder BL, Palmer S, Knott JG. SWI/SNF-Brg1 regulates self-renewal and occupies core pluripotency-related genes in embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:317–328. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WY, Sharpless NE. The regulation of INK4/ARF in cancer and aging. Cell. 2006;127:265–275. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kleer CG, Cao Q, Varambally S, Shen R, Ota I, Tomlins SA, Ghosh D, Sewalt RG, Otte AP, Hayes DF, et al. EZH2 is a marker of aggressive breast cancer and promotes neoplastic transformation of breast epithelial cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:11606–11611. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Klochendler-Yeivin A, Fiette L, Barra J, Muchardt C, Babinet C, Yaniv M. The murine SNF5/INI1 chromatin remodeling factor is essential for embryonic development and tumor suppression. EMBO Reports. 2000;1:500–506. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kotake Y, Cao R, Viatour P, Sage J, Zhang Y, Xiong Y. pRB family proteins are required for H3K27 trimethylation and Polycomb repression complexes binding to and silencing p16INK4alpha tumor suppressor gene. Genes Dev. 2007;21:49–54. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Krimpenfort P, Quon KC, Mooi WJ, Loonstra A, Berns A. Loss of p16Ink4a confers susceptibility to metastatic melanoma in mice. Nature. 2001;413:83–86. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TI, Jenner RG, Boyer LA, Guenther MG, Levine SS, Kumar RM, Chevalier B, Johnstone SE, Cole MF, Isono K, et al. Control of developmental regulators by Polycomb in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006;125:301–313. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JC, Jeong S, Liang G, Takai D, Fatemi M, Tsai YC, Egger G, Gal-Yam EN, Jones PA. Role of Nucleosomal Occupancy in the Epigenetic Silencing of the MLH1 CpG Island. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:432–444. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna ES, Roberts CW. Epigenetics and cancer without genomic instability. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:23–26. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna ES, Sansam CG, Cho YJ, Greulich H, Evans JA, Thom CS, Moreau LA, Biegel JA, Pomeroy SL, Roberts CW. Loss of the epigenetic tumor suppressor SNF5 leads to cancer without genomic instability. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:6223–6233. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak DE, Tian B, Brasier AR. Two-step cross-linking method for identification of NF-kappaB gene network by chromatin immunoprecipitation. BioTechniques. 2005;39:715–725. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Oruetxebarria I, Venturini F, Kekarainen T, Houweling A, Zuijderduijn LM, Mohd-Sarip A, Vries RG, Hoeben RC, Verrijzer CP. P16INK4a is required for hSNF5 chromatin remodeler-induced cellular senescence in malignant rhabdoid tumor cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:3807–3816. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Reich M, Liefeld T, Gould J, Lerner J, Tamayo P, Mesirov JP. GenePattern 2.0. Nature genetics. 2006;38:500–501. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Reisman D, Glaros S, Thompson EA. The SWI/SNF complex and cancer. Oncogene. 2009;28:1653–1668. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts CW, Biegel JA. The role of SMARCB1/INI1 in development of rhabdoid tumor. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009;8:412–416. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts CW, Galusha SA, McMenamin ME, Fletcher CD, Orkin SH. Haploinsufficiency of Snf5 (integrase interactor 1) predisposes to malignant rhabdoid tumors in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:13796–13800. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts CW, Leroux MM, Fleming MD, Orkin SH. Highly penetrant, rapid tumorigenesis through conditional inversion of the tumor suppressor gene Snf5. Cancer cell. 2002;2:415–425. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Z, Raible F, Mollaaghababa R, Guyon JR, Wu CT, Bender W, Kingston RE. Stabilization of chromatin structure by PRC1, a Polycomb complex. Cell. 1999;98:37–46. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpless NE, Bardeesy N, Lee KH, Carrasco D, Castrillon DH, Aguirre AJ, Wu EA, Horner JW, DePinho RA. Loss of p16Ink4a with retention of p19Arf predisposes mice to tumorigenesis. Nature. 2001;413:86–91. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X, Liu Y, Hsu YJ, Fujiwara Y, Kim J, Mao X, Yuan GC, Orkin SH. EZH1 mediates methylation on histone H3 lysine 27 and complements EZH2 in maintaining stem cell identity and executing pluripotency. Mol Cell. 2008;32:491–502. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Simon JA, Lange CA. Roles of the EZH2 histone methyltransferase in cancer epigenetics. Mutat Res. 2008;647:21–29. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Somervaille TC, Matheny CJ, Spencer GJ, Iwasaki M, Rinn JL, Witten DM, Chang HY, Shurtleff SA, Downing JR, Cleary ML. Hierarchical maintenance of MLL myeloid leukemia stem cells employs a transcriptional program shared with embryonic rather than adult stem cells. Cell stem cell. 2009;4:129–140. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Sparmann A, van Lohuizen M. Polycomb silencers control cell fate, development and cancer. Nature reviews. 2006;6:846–856. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Su IH, Dobenecker MW, Dickinson E, Oser M, Basavaraj A, Marqueron R, Viale A, Reinberg D, Wulfing C, Tarakhovsky A. Polycomb group protein ezh2 controls actin polymerization and cell signaling. Cell. 2005;121:425–436. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:15545–15550. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Tamkun JW, Deuring R, Scott MP, Kissinger M, Pattatucci AM, Kaufman TC, Kennison JA. brahma: a regulator of Drosophila homeotic genes structurally related to the yeast transcriptional activator SNF2/SWI2. Cell. 1992;68:561–572. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Varambally S, Dhanasekaran SM, Zhou M, Barrette TR, Kumar-Sinha C, Sanda MG, Ghosh D, Pienta KJ, Sewalt RG, Otte AP, et al. The polycomb group protein EZH2 is involved in progression of prostate cancer. Nature. 2002;419:624–629. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GG, Allis CD, Chi P. Chromatin remodeling and cancer, Part II: ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:373–380. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Sansam CG, Thom CS, Metzger D, Evans JA, Nguyen PT, Roberts CW. Oncogenesis caused by loss of the SNF5 tumor suppressor is dependent on activity of BRG1, the ATPase of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex. Cancer research. 2009;69:8094–8101. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Wong DJ, Liu H, Ridky TW, Cassarino D, Segal E, Chang HY. Module map of stem cell genes guides creation of epithelial cancer stem cells. Cell stem cell. 2008;2:333–344. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2010.09.006

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

http://www.cell.com/article/S1535610810003430/pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1016/j.ccr.2010.09.006

Article citations

Opening and changing: mammalian SWI/SNF complexes in organ development and carcinogenesis.

Open Biol, 14(10):240039, 30 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39471843 | PMCID: PMC11521604

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Inhibiting EZH2 targets atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor by triggering viral mimicry via both RNA and DNA sensing pathways.

Nat Commun, 15(1):9321, 29 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39472584 | PMCID: PMC11522499

Aberrant SWI/SNF Complex Members Are Predominant in Rare Ovarian Malignancies-Therapeutic Vulnerabilities in Treatment-Resistant Subtypes.

Cancers (Basel), 16(17):3068, 03 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39272926 | PMCID: PMC11393890

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Never Smokers: An Insight into SMARCB1 Loss.

Int J Mol Sci, 25(15):8165, 26 Jul 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39125735 | PMCID: PMC11311737

Comprehensive Target Engagement by the EZH2 Inhibitor Tulmimetostat Allows for Targeting of ARID1A Mutant Cancers.

Cancer Res, 84(15):2501-2517, 01 Aug 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38833522 | PMCID: PMC11292196

Go to all (394) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

GEO - Gene Expression Omnibus

- (1 citation) GEO - GSE23659

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Polycomb mediated epigenetic silencing and replication timing at the INK4a/ARF locus during senescence.

PLoS One, 4(5):e5622, 20 May 2009

Cited by: 93 articles | PMID: 19462008 | PMCID: PMC2680618

SWI/SNF mediates polycomb eviction and epigenetic reprogramming of the INK4b-ARF-INK4a locus.

Mol Cell Biol, 28(10):3457-3464, 10 Mar 2008

Cited by: 175 articles | PMID: 18332116 | PMCID: PMC2423153

NSD1 mediates antagonism between SWI/SNF and polycomb complexes and is required for transcriptional activation upon EZH2 inhibition.

Mol Cell, 82(13):2472-2489.e8, 09 May 2022

Cited by: 21 articles | PMID: 35537449 | PMCID: PMC9520607

Targeting EZH2 and PRC2 dependence as novel anticancer therapy.

Exp Hematol, 43(8):698-712, 28 May 2015

Cited by: 74 articles | PMID: 26027790 | PMCID: PMC4706459

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NCI NIH HHS (7)

Grant ID: DP1 CA174420

Grant ID: R01 CA109467

Grant ID: F32 CA130312

Grant ID: 1 F32 CA130312-01A1

Grant ID: R01 CA113794

Grant ID: R01CA113794

Grant ID: U01 CA105423