Abstract

Free full text

Directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into intestinal tissue in vitro

Abstract

Studies in embryonic development have guided successful efforts to direct the differentiation of human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) into specific organ cell types in vitro 1,2. For example, human PSCs have been differentiated into monolayer cultures of liver hepatocytes and pancreatic endocrine cells3–6 that have therapeutic efficacy in animal models of liver disease 7,8 and diabetes 9 respectively. However the generation of complex three-dimensional organ tissues in vitro remains a major challenge for translational studies. We have established a robust and efficient process to direct the differentiation of human PSCs into intestinal tissue in vitro using a temporal series of growth factor manipulations to mimic embryonic intestinal development 10 (Summarized in supplementary Fig. 1). This involved activin-induced definitive endoderm (DE) formation 11, FGF/Wnt induced posterior endoderm pattering, hindgut specification and morphogenesis 12–14; and a pro-intestinal culture system 15,16 to promote intestinal growth, morphogenesis and cytodifferentiation. The resulting three-dimensional intestinal “organoids” consisted of a polarized, columnar epithelium that was patterned into villus-like structures and crypt-like proliferative zones that expressed intestinal stem cell markers17. The epithelium contained functional enterocytes, as well as goblet, Paneth, and enteroendocrine cells. Using this culture system as a model to study human intestinal development, we identified that the combined activity of Wnt3a and FGF4 is required for hindgut specification whereas FGF4 alone is sufficient to promote hindgut morphogenesis. Our data suggests that human intestinal stem cells form de novo during development. Lastly we determined that NEUROG3, a pro-endocrine transcription factor that is mutated in enteric anendocrinosis 18, is both necessary and sufficient for human enteroendocrine cell development in vitro. In conclusion, PSC-derived human intestinal tissue should allow for unprecedented studies of human intestinal development and disease.

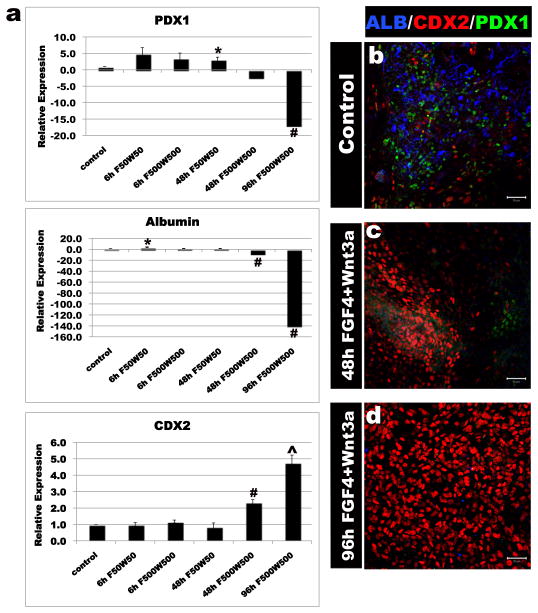

The epithelium of the intestine is derived from a simple sheet of cells called the definitive endoderm (DE) 17. As a first step to generating intestinal tissue from PSCs, we used ActivinA, a nodal-related TGFβ molecule, to promote differentiation into DE as previously published 11 resulting in up to 90% of the cells co-expressing the DE markers SOX17 and FOXA2 and fewer than 2% expressing the mesoderm marker Brachyury (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Using microarray analysis we observed a robust activation of DE markers, many of which were expressed in mouse DE from e7.5 embryos (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 1a and b). We investigated the intrinsic ability of DE to form foregut and hindgut lineages by culturing for seven days under permissive conditions and observed that cultures treated with ActivinA for only 3 days were competent to develop into both foregut (Albumin+ and PDX1+) and hindgut (CDX2) lineages (Fig. 1b, control). In contrast, treatment with ActivinA for 4–5 days resulted in DE cultures that were intrinsically anterior in character and less competent in forming posterior lineages (Supplementary Fig. 2b).

ActivinA (100ng/ml) was used to differentiate H9-HES cells into definitive endoderm (DE). DE was treated with the posteriorizing factors FGF4 (50, 500ng), Wnt3a (50, 500ng) or both for 6, 48 or 96 hours. Cells were placed in permissive media for 7 days and expression of foregut markers (ALB, PDX1) and the hindgut marker (CDX2) were analyzed by RT-qPCR (a) and immunofluorescence (b-d). Controls DE was grown for identical lengths of time in the absence of FGF4 or Wnt3a. High levels of FGF4+Wnt3a for 96 hours gave resulted in stable CDX2 expression and lack of foregut marker expression. Error bars are S.E.M (n=3). Significance is shown by; * (p<0.05), ^ (p<0.001), # (p<0.0001).

Having identified the window of time when DE fate was plastic (day 3 of ActivinA treatment), we used Wnt3a and FGF4 to promote hindgut and intestinal specification. Studies in mouse, chick and frog embryos have demonstrated that Wnt and FGF signaling pathways are required for repressing anterior development and promoting posterior endoderm formation into the midgut and hindgut 12–14. Consistent with this, conditioned media containing Wnt3a was recently shown to promote Cdx2 expression in mouse ES-derived embryoid bodies19. In human DE cultures, neither factor alone was sufficient to robustly promote a posterior fate (Supplementary Fig. 2c). However high concentrations of both FGF4+Wnt3a induced expression of the hindgut marker CDX2 in the DE after 48 hours (Supplementary Fig. 4). However 48 hours of FGF4+Wnt3a treatment did not stably induce a CDX2+ hindgut fate and expression of anterior markers PDX1 and Albumin reappeared after cells were cultured in permissive media for 7 days (Fig. 1a, c). In contrast, 96 hours of exposure to FGF4+Wnt3a resulted in stable CDX2 expression and absence of anterior markers (Fig. 1a and d). These findings suggest a previously unidentified requirement for the synergistic activities of both the FGF and Wnt pathways in specifying the CDX2+ mid/hindgut lineage.

Remarkably, FGF4+Wnt3a treated cultures underwent morphogenesis that was similar to embryonic hindgut formation. Between 2 and 5 days of FGF4+Wnt3a treatment, flat cell sheets condensed into CDX2+ epithelial tubes, many of which budded off to form floating hindgut spheroids (Fig. 2a–c, Supplementary Fig. 5a–f) (Supplementary table 2a). Spheroids were similar to e8.5 mouse hindgut and consisted of uniformly CDX2+ polarized epithelium (E) surrounded by CDX2+ mesenchyme (M) (Fig. 2d–g). Spheroids were completely devoid of Albumin and PDX1-expressing foregut cells (Supplementary Fig. 5h and i). In vitro gut-tube morphogenesis was never observed in control or Wnt3a-only treated cultures. FGF4 treated cultures had a 2-fold expansion of mesoderm and generated 4–10 fold fewer spheroids (Supplementary Figure 2c and Supplementary Table 2a), which were weakly CDX2+ and did not undergo further expansion (data not shown). Together our data support a mechanism for hindgut development where FGF4 promotes mesoderm expansion and morphogenesis, while FGF4 and Wnt3a synergy is required for the specification of the hindgut lineage.

a, Bright field images of DE cultured for 96 hours in media, FGF4, Wnt3a or FGF4+Wnt3a. FGF4+Wnt3a cultures contained 3D epithelial tubes and free-floating spheres (black arrows) b, CDX2 immunostaining (Green) and nuclear stain (Draq5 - blue) on cultures shown in a. c, Bright field image of hindgut-like spheroids. d-f, Analysis of CDX2, basal-lateral laminin and E-Cadherin expression demonstrate an inner layer of polarized, cuboidal, CDX2+ epithelium surrounded by non-polarized mesenchymal CDX2+ cells. g, CDX2 expression in an e8.5 mouse embryo (sagittal section). Inset is a magnified view showing that both hindgut endoderm (E) and adjacent mesenchyme (M) are CDX2 positive (green). (FG – foregut, HG – hindgut).

Importantly, this method for directed differentiation is broadly applicable to other PSC lines as we were able to generate hindgut spheroids from both H1 and H9 hESC lines and from 4 iPSC lines that we have generated and characterized (Supplementary Figs. 3, 5, 6). The kinetics of differentiation and the formation of spheroids were comparable between these lines (Supplementary table 2). Two other iPSC lines tested were poor at hindgut spheroid formation and line iPSC3.6 also had a divergent transcriptional profile during DE formation (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary table 2c).

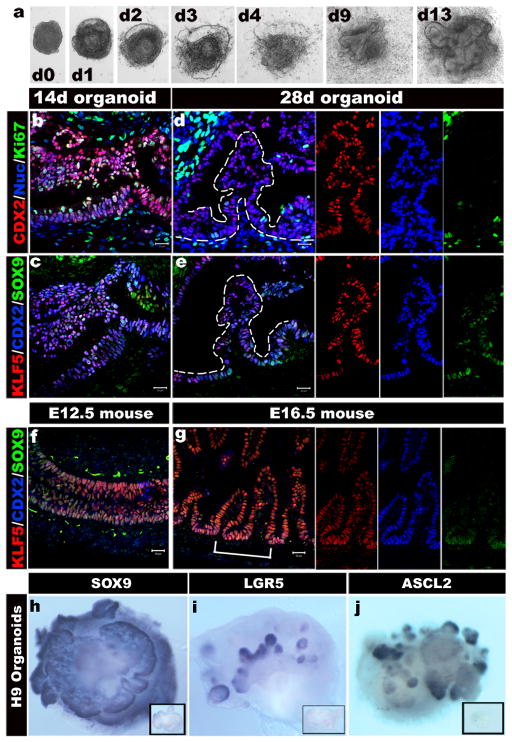

While in vivo engraftment of PSC-derived cell types, such as pancreatic endocrine cells, has been used to promote maturation 9, efficient development and maturation of organ tissues in vitro has proven more difficult. We investigated if hindgut spheroids could develop and mature into intestinal tissue in vitro using recently described 3-dimensional culture conditions that support growth and renewal of the adult intestinal epithelium 15,16. When placed into this culture system, hindgut spheroids developed into intestinal organoids in a staged manner that was strikingly similar to fetal gut development (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 5g, and Supplementary Fig. 7). In the first 14 days the simple cuboidal epithelium of the spheroid expanded and formed a highly convoluted pseudostratified epithelium surrounded by mesenchymal cells (Fig. 3a–c) similar to an e12.5 fetal mouse gut (Fig. 3f). After 28 days, the epithelium matured into a columnar epithelium with villus-like involutions that protrude into the lumen of the organoid (Fig. 3d, e). Comparable transitions were observed during mouse fetal intestinal development (Fig. 3f, g and Supplementary Fig. 7). The spheroids expanded up to 40 fold in mass as they formed organoids (data not shown) and were split and passaged over 9 additional times and cultured for over 140 days with no signs of growth failure. The cellular gain during that time was up to 1,800 fold (data not shown), resulting in a total cellular expansion of 72,000 fold per hindgut spheroid. This directed differentiation was up to 50-fold more efficient than spontaneous Embryoid Body (EB) differentiation methods 20 (Supplementary Fig. 8) and resulted in organoids were almost entirely intestinal (Supplementary Fig. 2e–g) as compared to EBs that contained a mix of neural, vascular, and epidermal tissues (Supplementary Fig. 8).

a, A time course shows that intestinal organoids formed highly convoluted epithelial structures surrounded by mesenchyme after 13 days. b-e, Intestinal transcription factor expression (KLF5, CDX2, SOX9) and cell proliferation on serial sections of organoids after 14 and 28 days (serial sections are b and c, d and e). f and g, Expression of KLF5, CDX2, and SOX9 in mouse fetal intestine at e14.5 (f) and e16.5 (g) is similar to developing intestinal organoids. The right panels show separate color channels for d, e and g. h, i and j, whole mount in situ hybridization of 56 day old organoids showing epithelial expression of Sox9 (h) and restricted “crypt-like” expression of the stem cell markers Lgr5 (i) and Ascl2 (j). Insets show sense controls for each probe.

Marker analysis showed that after 14 days in culture, virtually all of the epithelium expressed the intestinal transcription factors CDX2, KLF5 and SOX9 broadly and was highly proliferative (Fig. 3b, c). By 28 days CDX2 and KLF5 remained broadly expressed in over 90% of the epithelium (Supplementary Fig. 2), while SOX9 became localized to pockets of proliferating cells at the base of the villus-like protrusions (Fig. 3d, e) similar to the intervillus epithelium of fetal mouse intestines at e16.5 (Fig. 3g and Supplementary Fig. 9). BrdU pulse chase and analysis of organoids using a Z-stack series of confocal microscopic images showed that epithelial BrdU incorporation was largely restricted to SOX9-expressing cells in crypt-like structures that penetrated into the underlying mesenchyme (Supplementary Fig. 9). At 28 days the SOX9+ proliferative zones weakly expressed the intestinal stem cell marker ASCL2 21 and did not express LGR5. However, organoids cultured until 56 days expressed both ASCL2 and LGR5 in restricted epithelial domains that appear to overlap with the SOX9+ zone (Fig. 3h–j, Supplementary Fig. 10). This domain is similar to developing intestinal progenitor domains in vivo, which ultimately gives rise to the stem cell niche in the crypt of Lieberkühn 15. iPSCs were equally capable of forming intestinal progenitor domains (Supplementary Fig. 9e). Thus, PSC-derived intestinal epithelium continued to mature in vitro and develop proliferative domains with nascent intestinal stem cells.

Between 18 and 28 days in culture, we observed cytodifferentiation of the stratified epithelium into a columnar epithelium containing brush borders and all of the major cell lineages of the gut as determined by immunofluorescence and RT-qPCR (Fig. 4a–d and Supplementary Fig. 11). By 28 days of culture Villin (Fig. 4a) and DPPIV (not shown) were localized to the apical surface of the polarized columnar epithelium and transmission electron microscopy revealed a brush border of apical microvilli indistinguishable from those found in mature intestine (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Fig. 1). Enterocytes had a functional peptide transport system and were able to absorb a fluorescently labeled di-peptide (Fig. 4e) 22. Cell counting revealed that the epithelium contained approximately 15% MUC2+ goblet cells, which secrete mucins into the lumen of the organoid, 18% lysozyme positive cells that are indicative of Paneth cells and ~1% chromogranin A-expressing enteroendocrine cells (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 11g). MUC2 and lysozyme staining indicated that the goblet and Paneth cells in 28-day organoids are immature (Figure 4a and b). However in organoids that were passaged over 100 days, all cells had acquired a more mature phenotype and Paneth cells were often localized in crypt-like structures (Supplementary Fig. 12b and c). RT-qPCR confirmed the presence of additional markers of differentiated enterocytes (iFABP) and Paneth cells (MMP7) (Supplementary Fig. 11). Individual organoids appeared to be a mix of proximal intestine (GATA4+/6+) and distal intestine (GATA4-/GATA6+)(HOXA13-expressing) (Supplementary Figs. 11 and 13) 23. Thus, directed differentiation of PSCs into intestinal tissue in vitro is highly efficient in generating three-dimensional intestinal tissue containing crypt-like progenitor niches, villus-like domains and all of the differentiated cell types of the intestinal epithelium.

28 day iPSC-derived organoids were analyzed for a, villin (VIL) and the goblet cell marker mucin (MUC2), b, the paneth cell marker lysozyme (LYSO) or c, the endocrine cell marker chromogranin A (CGA). d, Electron micrograph showing an enterocyte cell with a characteristic brush border with microvilli (inset). e, Epithelial uptake of the fluorescently labeled dipeptide d-Ala-Lys-AMCA (arrowheads) indicating a functional peptide transport system. f-h, Adenoviral expression of Neurog3 (pAd-NEUROG3) causes a 5-fold increase in CGA+ cells compared to a GFP control (pAd-GFP); (n=4 biological samples);*(p=0.005). i-k, Organoids were generated from hESCs that were stably transduced with shRNA-expressing lentiviral vectors. Compared to control shRNA organoids, NEUROG3 shRNA organoids had a 95% reduction in the number of CgA+ cells; (n=3 for shRNA controls and n=5 for Neurog3-shRNA); *(p=0.018). Error bars for h,k are S.E.M.

Intestinal organoids contained a mesenchymal layer that developed along with the epithelium in a staged manner similar to embryonic development 10,24 (Supplementary Fig. 14). Mesenchyme likely came from the 2% of mesoderm cells that were present after Activin differentiation, which expanded up to 10% in FGF4-treated hindgut cultures (Supplementary Fig. 2). At 14-days, organoids broadly expressed mesenchymal markers including FOXF1 and Vimentin (Supplementary Fig. 14) similar to an e12.5 embryonic intestine (Supplementary Fig. 7). We also observed Vimentin+/smooth muscle actin (SMA)+ double positive cells indicative of intestinal subepithelial myofibroblasts (ISEMFs)25. By 28 days, we observed a layer of SMA+/desmin+ double positive cells indicating smooth muscle and desmin+/Vimentin+ fibroblasts 26. The fact that intestinal mesenchyme differentiation coincided with differentiation of the overlying epithelium suggests that epithelial-mesenchymal crosstalk may be important in the development of PSC-derived intestinal organoids.

The molecular basis of congenital malformations in humans is often inferred from functional studies in model organisms. For example, Neurogenin 3 (NEUROG3) was investigated as a candidate gene responsible for congenital loss of intestinal enteroendocrine cells in humans 18 because of its known role in enteroendocrine cell development in mouse 27–30. However it has been impossible to directly investigate the role of NEUROG3 during human intestinal development. We therefore performed gain- and loss-of-function analyses to investigate the role of NEUROG3 during human enteroendocrine cell development (Fig. 4 and Supplementary fig. 15). NEUROG3 was over-expressed in 28-day human organoids using Adenoviral-mediated transduction 31. After 7 days, approximately 5% of cells were GFP+ and Ad-NEUROG3-GFP infected organoids contained 5-fold more chromograninA+ endocrine cells than control organoids (Ad-EGFP) (Fig. 4f–h and Supplementary Fig. 15), demonstrating that NEUROG3 expression is sufficient to promote an enteroendocrine cell fate. To knock down endogenous NEUROG3, we generated HESC lines by transducing cells with NEUROG3 shRNA-expressing lentiviral vectors. NEUROG3 mRNA levels were knocked down by 63% and this resulted in a 90% reduction in the number of enteroendocrine cells (Fig. 4i–k and Supplementary Fig. 15d) demonstrating that intestinal enteroendocrine cell development is highly dependent on NEUROG3 expression. This suggests that partial loss-of-function mutations in human NEUROG3 would be sufficient to cause a dramatic reduction in enteroendocrine cell numbers.

In conclusion, this is the first report demonstrating that human PSCs can be efficiently directed to differentiate in vitro into human tissue with a three-dimensional architecture and cellular composition remarkably similar to the fetal intestine. Moreover PSC-derived human intestinal tissue undergoes maturation in vitro, developing intestinal stem cells and acquiring both absorptive and secretory functionality. Furthermore this system allows for functional studies to investigate the molecular basis of human congenital gut defects in vitro and to generate intestinal tissue for eventual transplantation-based therapy for diseases such as necrotizing enterocolitis, inflammatory bowel diseases and short gut syndromes. Moreover the ability to generate human intestinal tissues should greatly facilitate future studies of intestinal stem cells and drug design to enhance absorption and bioavailability.

METHODS SUMMARY

Generation of human intestinal organoids

Human embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells were maintained on Matrigel (BD Biosciences) in mTesR1 media without feeders. Differentiation into Definitive Endoderm was carried out as previously described 11. Briefly, a 3-day ActivinA (R&D systems) differentiation protocol was used. Cells were treated with ActivinA (100ng/mL) for three consecutive days in RPMI 1640 media (Invitrogen) with increasing concentrations of 0%, 0.2%, 2% HyClone defined FBS (dFBS) (Thermo Scientific). For hindgut differentiation, DE cells were incubated in 2% dFBS-DMEM/F12 with 500ng/ml FGF4 and 500ng/ml Wnt3a (R&D Systems) for up to 4 days. Between 2 and 4 days with treatment of growth factors, 3-dimensional floating spheroids formed and were then transferred into three-dimensional cultures previously shown to promote intestinal growth and differentiation 15,16. Briefly, spheroids were embedded in Matrigel (BD Bioscience) containing 500ng/mL R-Spondin1 ( R&D Systems), 100ng/mL Noggin (R&D Systems) and 50ng/mL EGF (R&D Systems). After the Matrigel solidified, media (Advanced DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen) supplemented with L-Glutamine, 10 μM Hepes, N2 supplement (R&D Systems), B27 supplement (Invitrogen), and Pen/Strep containing growth factors was overlaid and replaced every 4 days.

Supplementary Material

1

4

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the lab, D. Wiginton and C. Wylie for input. Vectors and antibodies were from D. Melton (Addgene #19410, #19413), S. Yamanaka (#17217-17220), C. Baum (Oct4, Klf4, Sox4, Myc lenti), and I. Manabe (Klf5 antibody). This work was supported by the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation JDRF-2-2003-530 (JMW) and NIH, R01GM072915 (JMW); R01DK080823A1 and S1 (AMZ and JMW); R03 DK084167 and R01 CA142826 (NFS), F32 DK83202-01 and T32 HD07463 (JRS). We also acknowledge core support for viral vectors, microarrays (supported by P30 DK078392), karyotyping and the Pluripotent Stem Cell Facility (supported by U54 RR025216).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Accession number for microarray data: NCBI: GSE25557.

Full Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Contributions

J.M.W. and J.R.S. conceived the study and experimental design, performed and analyzed experiments and co-wrote the manuscript. S.A.R, M.F.K and J.E.V. performed experiments. C.N.M, M.F.K, K.T., V.V.K., J.E.V, B.E.H., and S.I.W. provided reagents, conceptual and/or technical support in generating and characterizing iPSC lines and intestinal organoids. N.F.S. and A.M.Z. provided additional conceptual and experimental support and co-funded the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09691

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc3033971?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/101849972

Article citations

Xenotransplanted human organoids identify transepithelial zinc transport as a key mediator of intestinal adaptation.

Nat Commun, 15(1):8613, 07 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39375337 | PMCID: PMC11458589

The Use of Patient-Derived Organoids in the Study of Molecular Metabolic Adaptation in Breast Cancer.

Int J Mol Sci, 25(19):10503, 29 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39408832 | PMCID: PMC11477048

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Standardization and quality assessment for human intestinal organoids.

Front Cell Dev Biol, 12:1383893, 12 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39329062 | PMCID: PMC11424408

Interactions of SARS-CoV-2 with Human Target Cells-A Metabolic View.

Int J Mol Sci, 25(18):9977, 16 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39337465 | PMCID: PMC11432161

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Multi-Omics Profiles of Small Intestine Organoids in Reaction to Breast Milk and Different Infant Formula Preparations.

Nutrients, 16(17):2951, 02 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39275267 | PMCID: PMC11397455

Go to all (1,065) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

GEO - Gene Expression Omnibus

- (1 citation) GEO - GSE25557

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

FGF4 and retinoic acid direct differentiation of hESCs into PDX1-expressing foregut endoderm in a time- and concentration-dependent manner.

PLoS One, 4(3):e4794, 11 Mar 2009

Cited by: 68 articles | PMID: 19277121 | PMCID: PMC2651644

Generation of Gastrointestinal Organoids from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells.

Methods Mol Biol, 1597:167-177, 01 Jan 2017

Cited by: 28 articles | PMID: 28361317

Intestinal lineage commitment of embryonic stem cells.

Differentiation, 81(1):1-10, 08 Oct 2010

Cited by: 42 articles | PMID: 20934799

Activin A-induced differentiation of embryonic stem cells into endoderm and pancreatic progenitors-the influence of differentiation factors and culture conditions.

Stem Cell Rev Rep, 5(2):159-173, 05 Mar 2009

Cited by: 56 articles | PMID: 19263252

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NCATS NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: UL1 TR000077

NCI NIH HHS (2)

Grant ID: R01 CA142826

Grant ID: R01 CA142826-02

NCRR NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: U54 RR025216

NICHD NIH HHS (2)

Grant ID: T32 HD07463

Grant ID: T32 HD007463

NIDDK NIH HHS (12)

Grant ID: P30 DK078392

Grant ID: R01 DK080823-01A1S1

Grant ID: F32 DK083202-01

Grant ID: R01 DK080823-01A1

Grant ID: R01DK080823A1

Grant ID: R03 DK084167

Grant ID: R01 DK080823

Grant ID: R03 DK084167-02

Grant ID: K01 DK091415

Grant ID: F32 DK083202

Grant ID: F32 DK83202-01

Grant ID: R01 DK092456

NIGMS NIH HHS (3)

Grant ID: R01 GM072915

Grant ID: R01GM072915

Grant ID: R01 GM072915-01A2