Abstract

Free full text

Increase in Invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae Infections in Children with Sickle Cell Disease since Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine Licensure

Abstract

Invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) in children with sickle cell disease (SCD) has decreased with prophylactic penicillin, pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine, and pneumococcal protein-conjugate vaccine (PCV7) usage. We report 10 IPD cases since PCV7 licensure, including a recent surge of non-vaccine serotypes. IPD continues to be a serious risk in SCD.

The natural history of sickle cell disease (SCD) includes a marked susceptibility to infection by Streptococcus pneumoniae. Prior to the advent of the polyvalent polysaccharide S. pneumoniae vaccine (PPV23), invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) affected approximately 10% of children with SCD by age 51, an infection risk that was 300 times greater than the general population.2 This susceptibility is primarily attributable to functional asplenia.3 By 1990, PPV234 and penicillin prophylaxis5 reduced the burden of IPD in SCD. More recently, a further 90%6 and 68%7 reduction of IPD in SCD was reported following the introduction of the heptavalent pneumococcal protein-conjugate vaccine (PCV7) in 2000.

However, a recent increase of IPD in hematologically normal children with non-vaccine serotypes has been reported.8 Reports of the trend in pneumococcal serotypes in patients with SCD because PCV7 licensure are limited.6, 7 We sought to describe cases of IPD in patients with SCD since PCV7 licensure.

Cases

We identified all cases of IPD at Children’s Medical Center Dallas after 2/17/2000 (PCV7 licensure) from administrative records. Cases had at least one ICD-9CM code for SCD (282.6x, 282.41, 282.42) and at least one IPD code (038.2, 041.2, 320.1, 481, 567.1). To ensure complete case identification, we also cross-referenced our sickle cell database for IPD. Sixteen cases were identified; 6 were excluded (2 for erroneous ICD-9CM coding, 2 for incomplete medical records, and 2 for unavailability of the pneumococcal isolate at an outside center). Pneumococcal isolates were serotyped using the capsular swelling method with commercially available rabbit anti-pneumococcal antisera (Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark.) The Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center approved this study.

Details of the 10 cases are presented in the Table. Patients were predominantly under the age of 5 years with sickle cell anemia (SS). Consistent with our center’s routine practice, all cases under age 5 with SS or sickle β0 thalassemia (Sβ0) had been prescribed prophylactic penicillin. Adherence to penicillin was not formally assessed. Additionally, we routinely administer PPV23 at age 2 and 5 years and ensure completion of the PCV7 series by age 18 months for all genotypes. The cases’ pneumococcal vaccine status is presented in the Table.

Table

Characteristics of IPD in Children with SCD

| Case | Age and Sex | SCD Genotype | Month& Year | Prophylactic PCN | PPV23 | PCV7 | Clinical Scenario | Culture Source | Pneumococcal Serotype | Susceptibilities* (MIC in mcg/mL) | Complications and Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1yo male | SS | 4/00 | Yes | None | Unavailable | Septic arthritis | L Hip fluid | Unavailable | Penicillin = 1, (S) Cefotaxime = 1, (S) | Resolution without complications |

| 2 | 2yo male | SS | 11/04 | Yes | 1 dose, 4/04 | 2 doses, last in 2/03 | Meningitis | Blood and CSF | 15A/C/F | Penicillin = 0.25, (S) Cefotaxime <0.25, (S) | Resolution without complications |

| 3 | 2yo female | SS | 3/05 | Yes | None | 3 doses, last in12/02 | ACS | Blood | 19A | Penicillin = 0.12, (S) Cefotaxime <0.25, (S) | Resolution without complications |

| 4 | 1yo female | SS | 11/05 | Yes | None | 4 doses, last in 4/05 | Septic shock | Blood | 7B/C | Penicillin = 0.06, (S) Cefotaxime <0.25, (S) | ICU, ARF, respiratory failure, DIC |

| 5 | 1yo male | SS | 8/07 | Yes | None | 4 doses, last in 2/07 | ACS | Blood | 19A | Penicillin = 4, (I) Cefotaxime = 2, (I) Vancomycin = 0.5 (S) | Resolution without complications |

| 6 | 1yo male | SS | 3/08 | Yes | Unknown | Unknown | Fever | Blood | 23A | Penicillin <0.03, (S) Cefotaxime <0.25, (S) | Stroke |

| 7 | 6yo female | SC | 9/08 | No | None | 3 doses, last in 1/05 | Septic shock | Blood | 23A | Penicillin = 0.12, (S) Cefotaxime <0.25, (S) | ICU, hepatic sequestration, ECMO, death |

| 8 | 5yo female | SS | 10/08 | No | 2 doses, last in 8/08 | 4 doses, last in 1/05 | Septic shock | Blood | 6A | Penicillin = 0.05, (S) Cefotaxime <0.25, (S) | ICU, ARF, respiratory failure, meningitis, peri-spinal abscess |

| 9 | 3yo male | Sβ0 | 11/08 | Yes | 1 dose, last in 4/07 | 4 doses, last in 8/06 | Septic shock | Blood | 23A | Penicillin <0.03, (S) Cefotaxime <0.25, (S) | ICU, hypotension, ARF, respiratory failure, stroke, osteomyelitis |

| 10 | 16yo male | SS | 2/09 | No | 2 doses, last in 3/98 | 1 dose, last in 9/00 | Septic shock | Blood | 23B | Penicillin <0.03, (S) | ICU, hypotension, ARF, RSV co-infection |

SS – sickle cell anemia; SC – sickle hemoglobin-C disease;Sβ0 – sickle β0 thalassemia; CSF – cerebrospinal fluid; ACS – acute chest syndrome; MIC – minimal inhibitory concentration; R = resistant, I = intermediate resistance, S = sensitive; ICU – intensive care unit; ARF – acute renal failure; DIC – disseminated intravascular coagulation; ECMO – extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation; RSV – respiratory syncytial virus

PCV-7 serotypes – 4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, 23F

PPV-23 serotypes – 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6B, 7F, 8, 9N, 9V, 10A, 11A, 12F, 14, 15B, 17F, 18C, 19A, 19F, 20, 22F, 23F, 33F

Available isolates were predominantly non-vaccine (PCV7 and PPV23) serotype: 3 were 23A and 1 each was 6A, 7B/C, 15A/C/F, and 23B. The two isolates with vaccine (PPV23) serotype were 19A and occurred in unvaccinated patients. The mean presenting white blood cell (WBC) count was above baseline (22,000/mm3 vs 13,600/mm3), and the mean hemoglobin concentration (6.9 vs 7.5 g/dL) and percentage of reticulocytes (7.6 vs 10.8%) were below baseline. Baseline values were calculated as the average of 3 preceding steady-state values. IPD caused significant morbidity: 5 patients were admitted to the intensive care unit, 4 had respiratory failure, 4 had acute renal failure, 2 had acute stroke, and 2 had meningitis.

One child died (case 7), a 6 year old girl with sickle hemoglobin-C disease. She was brought to the emergency department (ED) with 1-week of cough and congestion, one day of vomiting, and several hours of fever to 104°F. Upon presentation, she was awake, alert and in no distress without focal findings of infection. The initial complete blood count (CBC) showed a WBC count of 9,100/mm3 and hemoglobin of 9.9 g/dL and platelets of 243 000/mm3. Three hours later, following intravenous antibiotic therapy and while still in the ED, she became unresponsive, developed massive hepatic enlargement, and quickly progressed to cardiorespiratory failure. Repeat CBC showed a WBC count of 21,700/mm3 hemoglobin of 3.7 g/dL, and platelets of 33 000/mm3. Resuscitation including cannulation for extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) was ineffective and she died 12 hours after presentation. Blood culture grew S. pneumoniae within 8 hours. Final clinicopathologic diagnosis was septic shock complicated by acute hepatic sequestration.

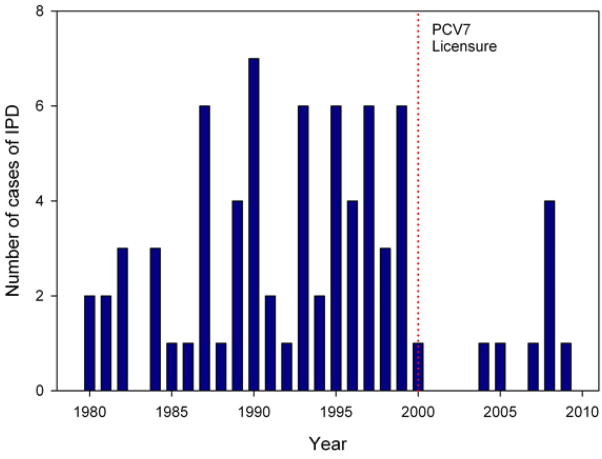

The Figure shows the crude annual frequency of IPD at our center between 1980 and 2009. The number of patients actively followed at our center during this time-frame remained relatively stable (approximately 650 per year). Pre-PCV7 infections were identified by query of our clinical database; no isolates were available for study. The crude frequency of IPD at our center fell to zero shortly after licensure of PCV7 (2001–2003), but there appears to be a recent increase in IPD that began in 2004.

A total of 66 cases of IPD were identified before PCV7 licensure (1980–1999) compared with 10 cases from after PCV7 licensure (2000–2009). The frequency of IPD at our center fell to zero shortly after licensure of PCV7 (2001–2003), but there appears to be a recent increase in IPD that started in 2004.

Discussion

We report 10 cases of IPD in children with SCD in our institution since PCV7 licensure in 2000. These cases are informative and potentially alarming in several respects. First is the apparent recent increase in IPD cases. Two other reports describe IPD in SCD since PCV7 licensure, but included relatively short follow-up periods after licensure (2 and 4 years).6, 7 Similar to these reports, we encountered few cases of IPD immediately after PCV7 licensure. With longer follow-up since PCV7 licensure (9 years), however, we now observe an increasing frequency of IPD, especially in the past 2 years. Further study of IPD in patients with SCD is needed to determine if our experience is occurring in other SCD populations.

Second, our IPD cases were predominantly with serotypes not contained in PCV7 or PPV23. This finding is consistent with the 89.1% prevalence of non-vaccine serotypes in 393 pneumococcal isolates in children without SCD in 2005-2006.9 A new pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, PCV13, was recently FDA-approved and will add serotypes 1, 3, 5, 6A, 7F, and 19A to those in PCV7.10 However, this additional coverage of PCV-13 would have protected only 3 of our 9 serotyped cases.

Third, the morbidity and mortality in our cases is remarkable. The case fatality rate of IPD was less than 1% in unselected children in the United Kingdom11 but was 10% in patients with SCD in the mid-1990s.12 Few studies have detailed morbidity related to IPD, yet our cases frequently had sepsis and respiratory failure requiring intensive care; some had renal failure or stroke. Consistent with prior reports, our older patients seem to have a higher morbidity associated with IPD.12, 13

In summary, we have seen a recent increase in the frequency of IPD which is caused by non-vaccine serotypes. IPD continues as a serious and sometimes fatal complication of SCD. These findings should drive continued efforts to develop better vaccines, improve the early identification and follow-up of patients with SCD by newborn screening, encourage adherence to penicillin prophylaxis and pneumococcal vaccination, and educate patients with SCD, families, and providers regarding the importance of promptly seeking medical attention for high fever.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH/NHLBI (U54 HL0705088-06) and NIH (UL1 RR024982-03).

We would like to thank Dr. George R. Buchanan for his thoughtful reviews of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.11.025

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc3062091?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

Pneumococcal infections in children with sickle cell disease before and after pneumococcal conjugate vaccines.

Blood Adv, 7(21):6751-6761, 01 Nov 2023

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 37698500 | PMCID: PMC10660014

Safety and immunogenicity of V114, a 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, in children with SCD: a V114-023 (PNEU-SICKLE) study.

Blood Adv, 7(3):414-421, 01 Feb 2023

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 36383730 | PMCID: PMC9979710

Monocyte HLA-DR Expression to Monitor Immune Response and Potential Infection Risks Following Vaso-Occlusive Crises in Patients with Sickle Cell Anemia.

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis, 14(1):e2022078, 01 Nov 2022

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 36425149 | PMCID: PMC9652011

Frequency of serious bacterial infection among febrile sickle cell disease children in the era of the conjugate vaccine: A retrospective study.

Int J Pediatr Adolesc Med, 9(3):165-170, 31 May 2022

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 36090129 | PMCID: PMC9441249

Incidence of Acute Chest Syndrome in Children With Sickle Cell Disease Following Implementation of the 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine in France.

JAMA Netw Open, 5(8):e2225141, 01 Aug 2022

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 35917121 | PMCID: PMC9346553

Go to all (52) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Pneumococcal bacteremia in a vaccinated pediatric sickle cell disease population.

Pediatr Infect Dis J, 31(5):534-536, 01 May 2012

Cited by: 16 articles | PMID: 22228232

Impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines on burden of invasive pneumococcal disease and serotype distribution of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates: an overview from Kuwait.

Vaccine, 30 Suppl 6:G37-40, 01 Dec 2012

Cited by: 8 articles | PMID: 23228356

Impact of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on serotype distribution and antimicrobial resistance of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates in Dallas, TX, children from 1999 through 2005.

Pediatr Infect Dis J, 26(6):461-467, 01 Jun 2007

Cited by: 102 articles | PMID: 17529859

Burden of invasive pneumococcal disease and serotype distribution among Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates in young children in Europe: impact of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and considerations for future conjugate vaccines.

Int J Infect Dis, 14(3):e197-209, 22 Aug 2009

Cited by: 177 articles | PMID: 19700359

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NCRR NIH HHS (2)

Grant ID: UL1 RR024982-03

Grant ID: UL1 RR024982

NHLBI NIH HHS (3)

Grant ID: U54 HL070588

Grant ID: U54 HL0705088-06

Grant ID: U54 HL070588-06