Abstract

Free full text

Complex Interactions Between Genes Controlling Trafficking in Primary Cilia

Abstract

Cilia-associated human genetic disorders are striking in the diversity of their abnormalities and their complex inheritance. Inactivation of the retrograde ciliary motor by mutations in DYNC2H1 cause skeletal dysplasias that have strongly variable expressivity. Here we define unexpected genetic relationships between Dync2h1 and other genes required for ciliary trafficking. Mutations in mouse Dync2h1 disrupt cilia structure, block Sonic hedgehog (Shh) signaling and cause midgestation lethality. Heterozygosity for Ift172, a gene required for anterograde ciliary trafficking, suppresses the cilia phenotypes, Shh signaling defects and early lethality of Dync2h1 homozygotes. Ift122, like Dync2h1, is required for retrograde ciliary trafficking, but reduction of the Ift122 gene dosage also suppresses the Dync2h1 phenotype. These genetic interactions illustrate the cell biology underlying ciliopathies and argue that mutations in IFT genes cause their phenotypes because of their roles in cilia architecture rather than direct roles in signaling.

Introduction

Human ciliopathies arise from defects in the primary cilium and can lead to obesity, retinal degeneration and cystic kidney disease, and are also associated with a wide array of morphological abnormalities. Although most of the characterized ciliopathies are single gene recessive disorders, there is evidence that mutations in more than one cilia-associated gene can have additive or synergistic effects in disease 1-5. It has been estimated that there are more than 100 cilia-associated human diseases 6 and that hundreds of genes are required for the construction of cilia and the centrioles that template cilia 7,8, making ciliopathies a model for the complex genetic interactions seen in human genetic disease.

Mutations in human DYNC2H1, which encodes the heavy chain of the cytoplasmic dynein-2 motor required for trafficking cargo from the tip to the base of the cilium, have been associated with short rib-polydactyly syndrome (SRP) type III and Jeune asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy (JATD) 9,10, two related skeletal dysplasias characterized by shortened long bones, a narrow rib cage and polydactyly, and other features of ciliopathies. Assembly of cilia depends on the process of intraflagellar transport (IFT) 11. IFT particles, composed of IFT-A and IFT-B protein complexes, are transported to the tip of the cilium (anterograde transport) by the heterotrimeric kinesin-2, and transport of products back to the base of the cilium (retrograde transport) is powered by cytoplasmic dynein-2. Chondrocyte cilia from individuals with DYNC2H1 mutations are shortened with bulbous distal ends, similar to the phenotypes of IFT-dynein mutant cilia in other species 10. The human syndromes show a range of severity, from lethality during gestation to adult survival in affected individuals, with no apparent relationship between the nature of the mutation and the severity of the disease 9. The presence of both SRP type III and the less severe JATD within the same family also suggests that the human phenotypes can be modified by other genetic or environmental factors 12.

Many of the morphological abnormalities seen in human ciliopathies are likely to be caused by disruption of the Hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway 13,14. Genetic analysis in the mouse and zebrafish has shown that primary cilia are essential for Hh signal transduction in vertebrate embryos 13. Mutations in all of the IFT genes that have been studied disrupt Hh signaling. For example, mouse mutants that lack IFT-B complex proteins lack cilia and fail to respond to Hh signals; these mutants can neither activate Hh target genes nor produce the Gli repressors that keep target genes off in the absence of ligand 15,16.

The proteins that mediate Hedgehog signal transduction are enriched in wild-type primary cilia. Patched1 (Ptch1), the Hh receptor, is present in cilia in the absence of ligand, but moves out in response to Hh ligand 17. The transmembrane protein Smoothened (Smo), which acts downstream of Ptch1 moves into cilia in response to Shh, and cilia localization of Smo is required to activate downstream signaling 17,18. The Gli2 and Gli3 transcription factors that implement Hh signals are enriched at the tips of cilia 19, and the level of Gli2 and Gli3 at cilia tips increases in response to ligand 20,21. It is, however, unclear how or whether IFT directly regulates trafficking of specific components of the Hh signal transduction pathway.

Mouse Dync2h1 mutants show a loss of Shh-dependent signaling in the neural tube and die at midgestation (~e10.5) 15,22. Here we define the genetic relationships between Dync2h1 and other genes required for ciliogenesis. Unexpectedly, we find that both the cilia morphology and Shh phenotypes of Dync2h1 homozygotes are strongly suppressed when the level of either the IFT-A or IFT-B proteins is reduced. The results indicate that the balance of anterograde and retrograde IFT controls ciliary architecture, which in turn controls Shh signaling and the developmental processes that are disrupted in ciliopathies.

Results

Dync2h1 mutant alleles disrupt Sonic hedgehog signal transduction and cilia structure

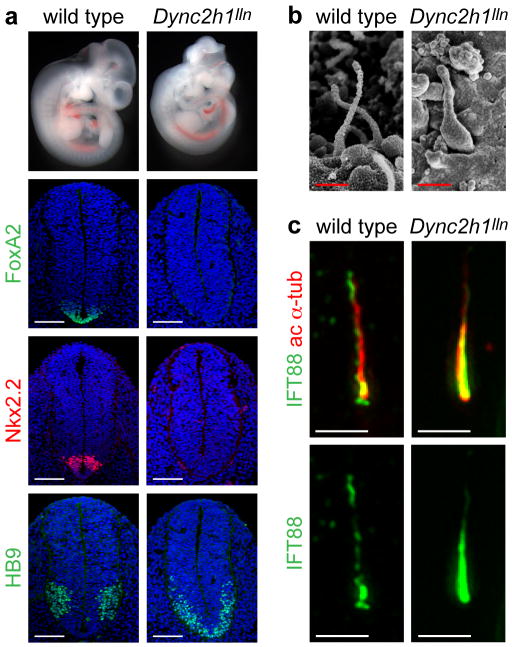

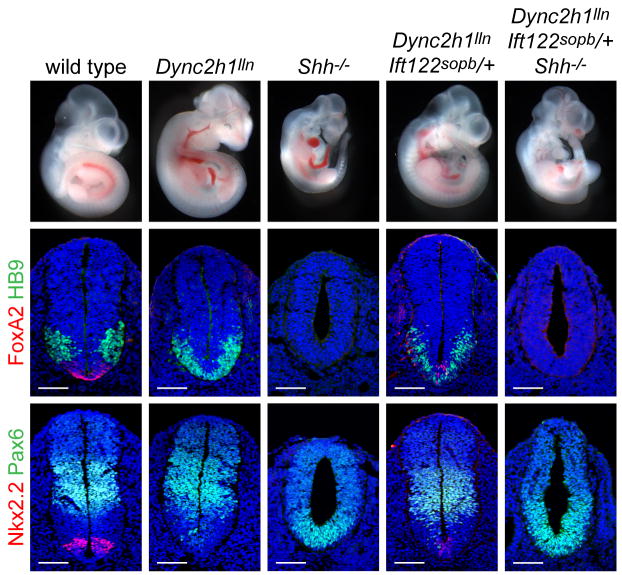

Shh-dependent neural patterning is blocked in each of the Dync2h1 mutants that have been studied, including apparent null alleles (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1) 15,22,23. The ventral neural cell types specified by the highest level of Shh signaling, the floor plate and V3 interneuron progenitors, are never specified in any of the mouse Dync2h1 mutants (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1a, b) 15,22,23. Motor neurons, which are specified by intermediate levels of Shh, are greatly reduced in number in the rostral neural tube (Supplementary Fig. 2), but do develop caudally (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1b). Double mutant analysis showed that Dync2h1 is required for the activity of the Hh pathway at the heart of the signal transduction pathway, downstream of Ptch1 and upstream of the Gli transcription factors (Supplementary Fig. 2), like other IFT genes 16,24.

(a), Mutations in Dync2h1 lead to the absence of Shh-dependent cell types in the E10.5 neural tube. In Dync2h1lln/lln mutants, floor plate (FoxA2, green) and V3 progenitor (Nkx2.2, red) domains are not specified, and motor neurons (HB9, green) are present only in the caudal neural tube (shown here); dorsal up. Scale bars represent 100 μm. (b), Scanning electron micrographs show that neural tube primary cilia in Dync2h1lln/lln mutants are bloated; dimensions are given in Supplementary Table1. Scale bars represent 500 nm. (c), IFT88 (green) in cilia of serum-starved wild-type MEFs is enriched at the base and the tip of the cilium, marked with acetylated α-tubulin (red). In Dync2h1lln/lln mutant MEFs, the amount of IFT88 in the cilium is increased and is found all along the axoneme. Quantitation is in Supplementary Table 2. Scale bars represent 1 μm (c).

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis of primary cilia in the neural tube showed that, while there were some differences in cilia morphology between different Dync2h1 alleles, all mutant cilia appeared swollen (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 1c). Dync2h1lln/lln cilia were the least affected of the Dync2h1 mutants; these cilia were as long as in wild type, but were twice as wide (Supplementary Table 1). We found that twice as much IFT88, a component of the IFT-B complex, accumulated in Dync2h1lln/lln ciliary axonemes (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Table 2), similar to the accumulation of IFT particles in Chlamydomonas dynein-2 mutant flagella 25-27.

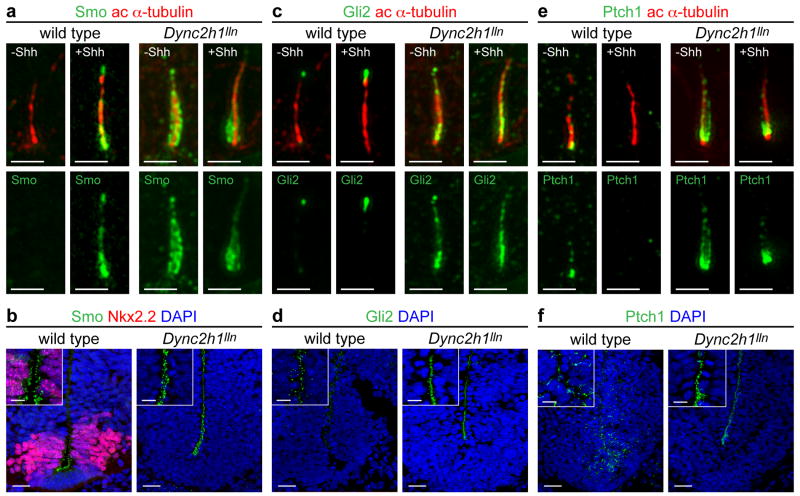

In contrast to the restricted, Shh-dependent localization of Shh pathway proteins in wild-type cilia, we observed previously that Smo accumulates in cilia of Dync2h1ttn/ttn mutant mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) 23 and over-expressed Gli2 accumulates to high levels in Dync2h1 RNAi-treated cells 28. We examined the localization of Hh pathway proteins in Dync2h1lln/lln MEFs (Fig. 2), and found that high levels of Smo, Gli2 and Ptch1 accumulated along the entire length of Dync2h1lln/lln ciliary axoneme in the absence or presence of Shh (Fig. 2a, c, e, Supplementary Table 3). We also examined the cilia on the neural progenitors that project into the lumen of the developing neural tube and found that Smo, Gli2 and Ptch1 accumulated to high levels in the cilia at both ventral positions, near the source of Shh, and dorsally, far from any Shh (Fig. 2b, d, f, Supplementary Fig. 3). Thus, even in the absence of ligand, Smo, Gli2 and Ptch1 traffic into cilia and accumulate there in the absence of the IFT-dynein retrograde motor.

Localization of Smo (a, b), Gli2 (c, d) and Ptch1 (e, f) to the primary cilium in wild-type and Dync2h1lln/lln MEFs (a, c, e) and E10.5 neural tube (b, d, f). (a) Smo (green) was enriched in cilia of wild-type MEFs only after exposure to Shh. Smo was enriched in cilia of Dync2h1lln/lln mutant cells even in the absence of Shh. (b) Smo was enriched in cilia of ventral neural progenitors in wild-type. Smo was strongly enriched in primary cilia of Dync2h1lln/lln neural progenitors at all dorsal-ventral levels. (c) Gli2 (green) localized to the tips of cilia in wild-type MEFs and accumulated further after Shh treatment. Gli2 levels were elevated along the axoneme of Dync2h1lln/lln mutant MEF cilia. (d) Gli2 was elevated in the cilia of Dync2h1lln/lln neural progenitors. (e) Low amounts of endogenous Ptch1 (green) were detected near the base and along the length of primary cilia in wild-type MEFs only in the absence of Shh, whereas Ptch1 was strongly enriched along the axoneme of Dync2h1lln/lln cilia in unstimulated cells; strong Ptch1 immunofluorescence remained near the base of the cilium after stimulation with Shh. (f) Ptch1 appeared localized to the cytoplasm of wild-type neural progenitors, and was strongly enriched in cilia throughout the neural tube in Dync2h1lln/lln mutants. Acetylated α-tubulin (red) marks cilia in (a, c, e); (b, d, f) are ventral views of transverse sections through the ventral half of the neural tube at the level of the forelimb. Scale bars represent 500 nm (a, c, e), 25 μm (b, d, f) and 10 μm (insets b, d, f).

Decreased activity of IFT-B suppresses the defects in Shh signaling, cilia morphology and Hh pathway protein localization of Dync2h1 homozygotes

Because Hh pathway proteins accumulate in primary cilia in the absence of the retrograde motor, we tested whether reduction of anterograde trafficking within the cilium would affect the Dync2h1lln/lln phenotypes. The IFT-B protein complex is required for anterograde trafficking, and null mutations in IFT-B genes block ciliogenesis 16. As expected, mutants that were homozygous for both Dync2h1lln and a null allele of an IFT-B gene, Ift172wim, were indistinguishable from Ift172wim homozygotes: they lacked cilia and embryos failed to specify all ventral neural cell types (Supplementary Fig. 4a). We then examined the Dync2h1lln phenotype when combined with avc1, a partial loss-of-function allele of Ift172 29,30. While neural patterning in Ift172avc1/avc1 mutants was nearly wild type (Supplementary Fig. 4a), Dync2h1lln/lln Ift172avc1/avc1 double mutants lacked floor plate and V3 progenitors, as in Dync2h1lln/lln but did specify motor neurons rostrally as well as caudally, suggesting that Ift172avc1/avc1 partially rescued the Dync2h1lln/lln phenotype (Supplementary Fig. 4).

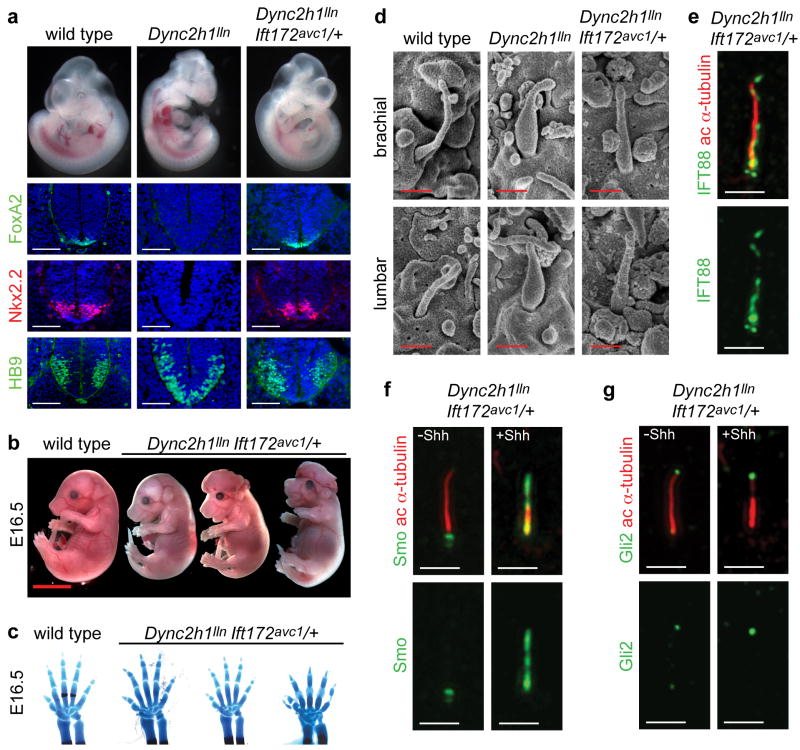

A more dramatic rescue of the Dync2h1 phenotype was observed in Dync2h1lln/lln Ift172avc1/+ compound mutants. All Shh-dependent ventral neural cell types were specified in the compound mutants, including the floor plate, which expressed FoxA2, and Nkx2.2-expressing V3 progenitors (Fig. 3a). A similar, but less complete, rescue of Shh-dependent neural patterning was seen in Dync2h1lln homozygotes that were heterozygous for null alleles of Ift172 or of another IFT-B complex gene, Ift88 (Supplementary Fig. 5), although Ift172wim/+, Ift88null/+ and Ift172avc1/+ animals have no detectable phenotype. While all Dync2h1lln/lln mutants die by E13.5 15, ~30% of Dync2h1lln/lln Ift172avc1/+ embryos survived to at least E16.5 (Fig. 3b). IFT mutants that survive long enough to make digits are polydactylous due to the failure to make Gli3 repressor 15,22,24,31-33. At E16.5, some Dync2h1lln/lln Ift172avc1/+ mutants (n=2/5) did not exhibit polydactyly in either forelimbs or hindlimbs (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Fig. 6). Thus a modest reduction of IFT-B proteins rescued the early lethality and polydactyly caused by the absence of IFT-dynein function.

(a), E10.5 embryos and transverse sections through the caudal neural tube of wild-type, Dync2h1lln/lln and Dync2h1lln/lln Ift172avc1/+ embryos. Specification of floor plate (FoxA2, green), V3 progenitors (Nkx2.2, red) and motor neurons (HB9, green) were rescued in Dync2h1lln/lln Ift172avc1/+ embryos. Scale bars represent 100 μm. (b), Dync2h1lln/lln Ift172avc1/+ mutants survive to at least E16.5 (n=5). Scale bar is 5 mm. (c), Right forelimbs and digits of embryos in (b) stained with Alcian blue (cartilage) and Alizarin red (bone) staining shows incomplete penetrance of polydactyly in Dync2h1lln/lln Ift172avc1/+ embryos at E16.5. (d), Scanning electron micrographs of cilia from the neural tube at E10.5 showing near-normal morphology of Dync2h1lln/lln Ift172avc1/+ mutant cilia (quantitation in Supplementary Table 1). Scale bar is 500 nm. IFT88 (green, e) and Smo (green, f) and Gli2 (red, g) localize normally in primary cilia of MEFs derived from Dync2h1lln/lln Ift172avc1/+ embryos. Acetylated α-tubulin (red) marks cilia in (e-g). Scale bars represent 1 μm in (e-g).

In parallel with this rescue of Shh signaling, the morphology of primary cilia in the neural tube of Dync2h1lln/lln Ift172avc1/+ was also rescued, as assayed by SEM (Fig 3d). The IFT-B complex protein IFT88 did not accumulate in the compound mutant cilia (Fig. 3e). In contrast to the accumulation of Smo in the absence of ligand in Dync2h1lln/lln MEFs (Fig. 2a), Smo was detected in cilia of Dync2h1lln/lln Ift172avc1/+ compound mutant cells only after stimulation with Shh (Fig. 3f), as in wild type. Gli2 was observed only at cilia tips in Dync2h1lln/lln Ift172avc1/+ mutants (Fig. 3g), as in wild type and at more normal levels (Supplementary Table 3). Thus, reduction of the level of IFT-B, and presumably a decreased rate of anterograde trafficking, bypassed the requirement for the IFT-dynein for both cilia structure and Shh signaling.

Hh pathway activation in the absence of both the IFT-A protein IFT122 and Dync2h1

Retrograde trafficking depends on both IFT-dynein and the IFT-A complex 25,26,34,35. Mouse mutants that lack the IFT-A complex genes Ift122 and Ttc21b (the mouse orthologue of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii IFT-A complex gene Ift139) have short bulbous cilia 24,36 and depletion of TTC21B causes slower retrograde IFT without affecting anterograde IFT 24, indicating that the function of IFT-A proteins in retrograde trafficking is conserved in mammals. However, in contrast to Dync2h1 mutants where the block in retrograde transport prevents the response to Shh, Ift139 and Ift122 mutants show ligand-independent ectopic activation of the Shh pathway 24,32.

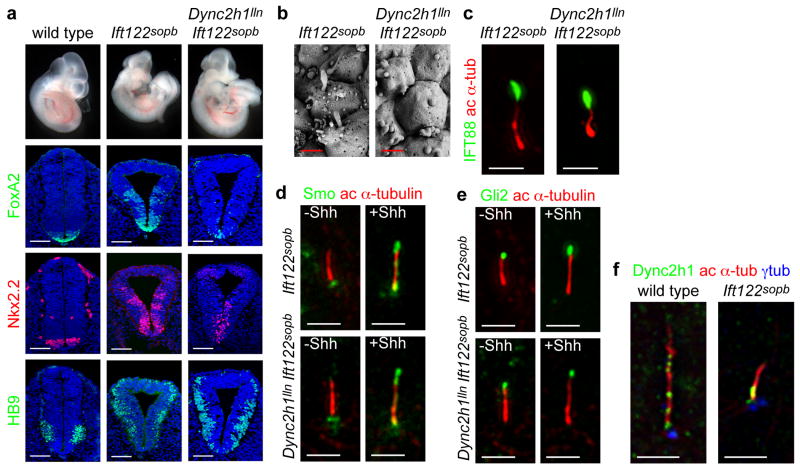

One hypothesis to explain the block of Hh signaling in Dync2h1 mutant embryos is that Gli proteins are trapped in the cilium by the defect in retrograde trafficking and therefore cannot activate target genes in the nucleus. If this were correct, then Dync2h1 IFT-A double mutant embryos should have a strong defect in retrograde trafficking and would be expected to lack Shh-dependent cell types in the neural tube. Ift122sopb is a null allele of the gene encoding IFT122 32, which is a core component of the IFT-A complex 37. Contrary to our expectation, embryos homozygous for both Dync2h1lln and the null allele Ift122sopb showed ectopic activity of the Shh pathway in the neural tube, similar to the phenotype of Ift122sopb/sopb single mutants (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. 7). The motor neuron marker HB9 was expressed in a dorsally expanded domain in the double mutants, as in Ift122sopb/sopb single mutants (Fig. 4a). Floor plate and V3 progenitors, which were absent in Dync2h1lln/lln embryos (Fig. 1b), were specified in the double mutants, although these domains did not show the dorsal expansion seen in Ift122sopb/sopb single mutants (Fig. 4a). Thus, in the context of this IFT-A mutant, the Shh pathway can be ectopically activated to high levels even in the absence of the canonical retrograde motor.

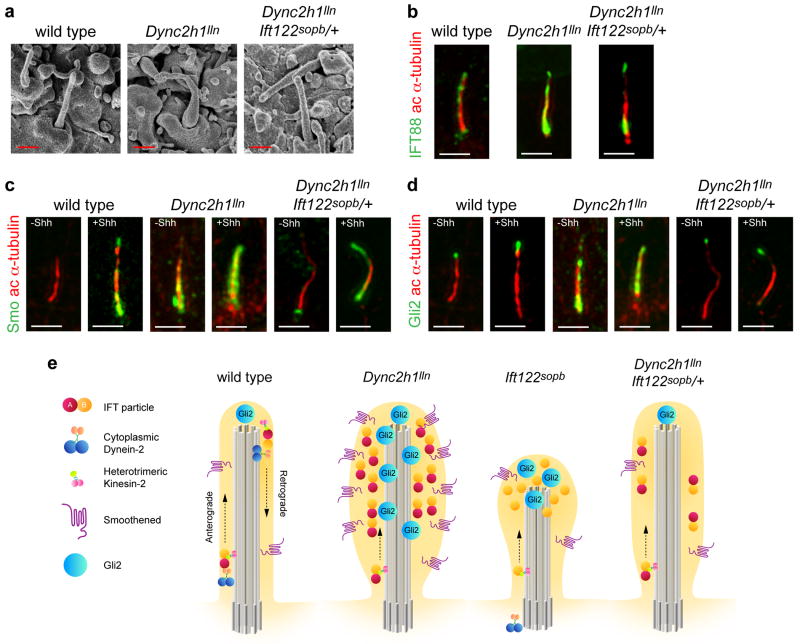

(a), In contrast to the lack of ventral neural cell types in Dync2h1lln/lln mutants, both Ift122sopb/sopb single and Dync2h1lln/lln Ift122sopb/sopb double mutants specify floor plate (FoxA2, green), V3 progenitors (Nkx2.2, red) and motor neurons (HB9, green) in the lumbar neural tube. Scale bars represent 100 μm. (b), Scanning electron micrographs of neural tube cilia from the neural tube of E10.5 Ift122sopb/sopb and Dync2h1lln/lln Ift122sopb/sopb embryos. The distal ends of Ift122sopb/sopb mutant cilia appeared swollen. Dync2h1lln/lln Ift122sopb/sopb mutant cilia were similar in diameter to Ift122sopb/sopb but were shorter than either Dync2h1lln/lln or Ift122sopb/sopb single mutants (See Supplementary Table 1). Scale bars represent 500 nm. (c), IFT88 (green) accumulates specifically at the distal tips of both Ift122sopb/sopb and Dync2h1lln/lln Ift122sopb/sopb mutant MEF cilia. Acetylated α-tubulin staining (red) marks primary cilia. Localization of Smo (d, green) and Gli2 (e, green) in the cilia of Ift122sopb/sopb and Dync2h1lln/lln Ift122sopb/sopb mutant MEFs. Acetylated α-tubulin (red) marks cilia. (f), Dync2h1 protein is present at the base of the cilium and along the ciliary axoneme in wild-type cells. In Ift122sopb/sopb mutant cilia, Dync2h1 localization accumulates mainly at the base of the cilium. Orientation for (b-f) is distal tip up. Scale bars are 1 μm (d-f).

Just as the neural patterning of the double mutants resembled that of Ift122sopb/sopb, the Dync2h1lln/lln Ift122sopb/sopb double mutant cilia were similar to those of the Ift122sopb/sopb single mutants (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Table 1). IFT88 was enriched at cilia tips (Fig. 4c), as in Ift122sopb/sopb single mutants, and not accumulated along the cilium as seen in Dync2h1lln/lln cilia (Fig. 1c). Smo was localized to cilia only in the presence of Shh (Fig. 4d), and Gli2 was limited to the tips of Dync2h1lln/lln Ift122sopb/sopb double mutant cilia (Fig. 4e). Thus removal of this IFT-A protein prevented the accumulation of proteins within the cilium caused by loss of Dync2h1, suggesting that Ift122 has a role in anterograde, as well as retrograde trafficking.

Dync2h1 protein was enriched at the base of the cilium and in puncta along in the axoneme of wild-type MEFs (Fig. 4f), as in Chlamydomonas 25,26. In contrast, Dync2h1 protein accumulated near the base of Ift122sopb mutant cilia with little or no staining along the distal axoneme (Fig. 4f). This suggests that the defect in retrograde trafficking in Ift122sopb mutants might be due to a failure of the retrograde motor to enter the cilium normally. The loss of Dync2h1 from the Ift122sopb/sopb cilium could account for the similarity between the Dync2h1lln/lln Ift122sopb/sopb double and Ift122sopb/sopb single mutant phenotypes.

Lowered dosage of Ift122 suppresses the Dync2h1 phenotype and restores Shh responsiveness

As with the IFT-B complex genes, removal of one copy of Ift122 partially rescued the phenotype of Dync2h1 homozygotes. All ventral neural cell types, including floor plate, V3 progenitors and motor neurons, were specified in the caudal neural tube in the Dync2h1lln/lln Ift122sopb/+ embryos (Fig. 5).

Whole embryos and patterning in the lumbar neural tube of E10.5 wild type, Dync2h1lln/lln, Shh-/-, Dync2h1lln/lln Ift122sopb/+ and Dync2h1lln/lln Ift122sopb/+ Shh-/- compound mutants. Specification of floor plate (FoxA2, red, middle panels), V3 progenitors (Nkx2.2, red, bottom panels) and motor neurons (HB9, green, middle panels) were partially rescued in Dync2h1lln/lln Ift122sopb/+ mutant embryos but all these cell types were absent in Dync2h1lln/lln Ift122sopb/+ Shh-/- embryos. The Pax6 domain (green, bottom panels), which is restricted by low levels of Shh signaling, was ventrally expanded in Shh-/- and Dync2h1lln/lln Ift122sopb/+ Shh-/- embryos. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

Two alternative models could explain the suppression of the Dync2h1 phenotype by decreased dosage of Ift122. In the first model, Dync2h1 and IFT122 have opposing phenotypes because they have opposing effects on the activity of core Hh pathway components and the suppression reflects a balance of these effects. Both Ift122 and Dync2h1 act downstream of Shh, Patched1 and Smoothened 32(Supplementary Fig. 1a), so this model predicts that Ift122 and Dync2h1 have opposing effects on the activity of pathway proteins downstream of Smo; in this case, the suppression of the Dync2h1 phenotype would be independent of the presence of ligand. Alternatively, the suppression could indicate that changing the balance of IFT proteins restored sensitivity to Shh ligand. We therefore tested whether activation of the pathway in Dync2h1lln/lln Ift122sopb/+ embryos depended on Shh. The external morphology of Dync2h1lln/lln Ift122sopb/+ Shh-/- mutants appeared to be intermediate between Dync2h1lln/lln Ift122sopb/+ and Shh-/- embryos (Fig. 5). In the neural tube, markers of the FP and V3 progenitors, which were expressed in Dync2h1lln/lln Ift122sopb/+ embryos, were not expressed in Dync2h1lln/lln Ift122sopb/+ Shh-/- compound mutants. Thus the specification of ventral neural cell types in Dync2h1lln/lln Ift122sopb/+ embryos depended on the presence of Shh (Fig. 5, Supplementary Fig. 8). This suggests that the suppression of the Dync2h1 phenotype was not due to a direct effect on the activity of core components of the Shh pathway and was instead due to a change in the balance of IFT trafficking.

Consistent with the model that reduced IFT122 suppressed the Dync2h1 phenotype because of the altered balance of IFT, cilia phenotypes were also strongly rescued by lowering the dosage of Ift122: Dync2h1lln/lln Ift122sopb/+ compound mutant neural cilia were less wide than Dync2h1lln/lln cilia (Fig. 6a, Supplementary Table 1). Trafficking of IFT88 (Fig. 6b, Supplementary Fig. 9a, Supplementary Table 2) and the Hh components Smo (Fig. 6c, Supplementary Fig. 9b) and Gli2 (Fig. 6d, Supplementary Fig. 9c, Supplementary Table 3) was also rescued in the compound mutant MEFs. Smo was found in cilia of Dync2h1lln/lln Ift122sopb/+ MEFs only after cells were exposed to Shh (Fig. 6c, Supplementary Fig. 9b) and Gli2 was enriched in cilia tips only after stimulation with Shh (Fig. 6d, Supplementary Fig. 9c, Supplementary Table 3). Therefore partial loss of Ift122 rescued the Dync2h1 trafficking defect, restoring normal cilia morphology and normal ciliary localization of Hh pathway proteins (Fig. 6e). The restored trafficking of Gli2 and Smo in MEFs also paralleled the ligand-dependent specification of ventral neural cell types in Dync2h1lln/lln Ift122sopb/+ embryos (Fig. 5). In addition, Ift122sopb/+ rescues the ectopic localization of Smo in neural cilia seen in Dync2h1lln/lln embryos: Smo is present in cilia only in the ventral neural tube of Dync2h1lln/lln Ift122sopb/+ embryos (Supplementary Fig. 10). Thus normal Shh-dependent protein trafficking in cilia and neural patterning can take place in the absence of Dync2h1, if the dosage of Ift122 is reduced.

(a), SEM analysis of neural tube primary cilia show the more normal length and width of Dync2h1lln/lln Ift122sopb/+ mutants compared to Dync2h1lln/lln. Quantitation in Supplementary Table 1. Scale bars are 500 nm. (b-d), Localization of IFT88 (b, green), Smo (c, green) and Gli2 (d, green) in cilia (acetylated α-tubulin, red) appear normal in Dync2h1lln/lln Ift122sopb/+ mutants. Scale bars are 500 nm (b-d). (e) Model of the trafficking of mammalian IFT and Hh pathway proteins in the primary cilium, shown in the absence of Hh ligand. In wild-type cells, IFT directs the formation of cilia, which accumulate a basal level of Gli2 at cilia tips, while Smo traffics through the cilium at a low basal rate. Loss of retrograde motor in Dync2h1lln/lln mutant cilia leads to the accumulation of IFT particles and blocks the movement of both Smo and Gli2 out of the cilium. In Ift122sopb/sopb mutants, Dync2h1 protein fails to enter the cilium, leading to the accumulation of IFT-B particles. Loss of IFT122 also results in the accumulation of Gli2 but does not affect Smo trafficking. Decreased anterograde ciliary trafficking in Dync2h1lln/lln Ift122sopb/+ suppresses the Dync2h1lln/lln phenotype and permits normal transport of both Smo and Gli2 through the cilium.

Discussion

Our studies suggest that the roles of IFT proteins in Shh signaling depend, in large part, on their importance in cilia structure. While both IFT-dynein and IFT-B complex proteins are required for Shh signaling, we find that reduction of IFT-B complex protein levels can suppress the defects in the Shh pathway defects and cilia morphology caused by loss IFT-dynein. The most striking rescue of the Dync2h1lln/lln phenotype was seen by lowering the amount of IFT172 to ~60% of wild-type levels. Neural patterning in the caudal neural tube is indistinguishable from wild type in Dync2h1lln/lln Ift172avc1/+ embryos. In contrast to the midgestation lethality of Dync2h1lln/lln embryos, the compound mutants survive to at least E16.5 when most of the phenotypes associated with defects in Hh signaling, such as polydactyly, are mitigated.

The rescue of Shh signaling in the compound mutants correlates with the rescue of cilia structure. Dync2h1 mutant cilia that accumulate IFT proteins, Smo, Ptch1 and Gli2 to high levels, but downstream Hh targets are not activated in the Dync2h1 mutant neural tube. In contrast, Dync2h1lln/lln Ift172avc1/+ cilia have normal morphology and do not accumulate either IFT or Hh pathway proteins, and Hh target gene expression appears to be normal. We therefore conclude that the defect in Shh signal transduction in Dync2h1lln/lln mutants is caused by a block of retrograde trafficking that disrupts the architecture of the cilium due to the accumulation of IFT-B and other ciliary proteins, and that IFT-dynein does not play a direct role in transporting Gli proteins from the tip to the base of the cilium.

Because double mutants that lack both IFT-dynein and the IFT-A protein IFT122 have cilia that resemble those of the Ift122 single mutant, we suggest that Dync2h1 and Ift122 mutants share a common defect in retrograde trafficking, and that IFT122 has additional roles in the cilium. Like the IFT-B genes, reduced dosage of Ift122 suppresses the Dync2h1 phenotype, which suggests the IFT-A complex has a role in anterograde ciliary trafficking. Similarly, recent findings in Chlamydomonas show that while partial loss of IFT-A function causes preferential defects in retrograde trafficking, complete loss of IFT-A leads to loss of flagella 35,38. We suggest the gain of Hh phenotype seen in IFT-A mutants occurs either because IFT-A is required to load unidentified Hh pathway antagonists into the cilium 32,37 or because the structure of the cilium is altered in IFT-A mutants in a way that disrupts the normal interactions between Hh pathway proteins.

Our findings show that lowered levels of two IFT-B complex genes and one IFT-A complex gene strongly suppress the Dync2h1 phenotype in the mouse. Although previous studies have shown that mutations in cilia-associated genes can have additive effects 1-5, this is the first demonstration that mutations in one set of cilia genes can suppress the phenotype of mutations that affect another aspect of ciliary trafficking. It is striking that although mutations in human IFT122 cause cranioectodermal dyplasia 39, a ciliopathy that partially overlap with JATD, our data predict that heterozygosity for human IFT122 would partially correct the defects seen in JATD caused by mutations in DYNC2H1. As hundreds of genes are required for the formation of primary cilia, it is possible that the variable expressivity of human DYNC2H1 mutations could be due to heterozygosity for mutations in other cilia genes. It will be important to consider this type of dosage-sensitive genetic interaction when analyzing whole exome sequence data to identify genes responsible for ciliopathies and other complex genetic disorders 40.

Methods

Antibodies

Smo and Ptch1 antibodies were raised in rabbits (Pocono Rabbit Farm and Laboratory Inc.) using antigens and procedures described previously 17; both antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:500. Monoclonal antibodies against Nkx2.2 (74.5A5), HB9/MNR2 (81.5C10) and Pax6 (PAX6) were used at 1:10 and obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank. In all experiments, ciliary microtubules were marked by expression of acetylated α-tubulin (mouse, 1:5000, Sigma Aldrich). Other antibodies used were: FoxA2 (rabbit, 1:200, Abcam), Olig2 (rabbit, 1:200, Millipore), γ tubulin (mouse, 1:5000, Sigma Aldrich), IFT88 (rabbit, 1:500, Proteintech). The Gli2 antibody was described previously 41 (guinea pig, 1:500); antibodies that recognize Dync2h1 42 (rabbit, 1:200) were a gift from R. Vallee (Columbia University).

Mouse Mutations and Strains

Genotyping for the Dync2h1 alleles ling-ling (lln), tian-tian (ttn) and mei-mei (mmi) as well as the genetrap line Dync2h1Gt(RRM278)Byg were described previously 15,23,43. All Dync2h1 alleles were maintained in a C3H background, with the exception of mmi, which was analyzed in the FVB background. At least three embryos for each genotype described were examined for both neural patterning and cilia structure.

Ift172avc1 is an A to G transition in the splice donor site upstream of exon 24 29; this change creates a DraIII restriction fragment length polymorphism when assayed in genomic DNA using the allele-specific primer wmp-G1. The Ift122sopb mutation is a C to T transition in the start codon and destroys a BtgZI restriction site assayed using allele-specific primer sopb-G1 to genotype genomic DNA. Ift172wim genotyping has been described previously 16,31. The Ift88null allele used in Supplementary Fig. 6 was generated by crossing the conditional Ift88 allele 44 to the CAG-Cre line 45. Genotyping of the Shhtm1Chg, Ptch1tm1Mps, Gli3Xt-J and Gli2tm1Alj mutant alleles was carried out as described 46-49.

Primary MEF cell culture

MEFs were isolated from E10.5 embryos as described 23. Cells were maintained in High Glucose DMEM, 0.05 mg/ml Penicillin, 0.05 mg/ml Streptomycin, 2 mM L-Glutamine, and 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS). Cells were shifted from 10% to 0.5% FBS 24-48h after plating to induce ciliogenesis. Shh stimulation was initiated 24h post starvation using Shh-conditioned medium (used at 1:5 dilution in low-serum medium) for an additional 24h as described 23.

Cells were fixed in 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) in Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) for 15 minutes and washed extensively in PBS + 0.1% Triton X-100 (PBT). Fixed cells were placed in blocking solution (PBT + 1% v/v FBS) for 10 minutes. Cells were then incubated with primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution overnight at 4°C. The next day, cells were washed three times in PBT and incubated with Alexa-coupled secondary antibodies and DAPI in blocking solution for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing three times in PBT, cells were mounted in Vectashield for microscopy. For Dync2h1 staining, cells were fixed in cold methanol at -20°C for 5 minutes after fixation in 4% PFA. Processing for immunofluorescence proceeded as described above.

Light microscopy

Cilia images were obtained using a DeltaVision image restoration microscope (Applied Precision/Olympus) equipped with CoolSnap QE cooled CCD camera (Photometrics). An Olympus 100×/1.40 NA, UPLS Apo oil immersion objective was used. Z-stacks were taken at 0.20-μm intervals. Images were deconvolved using the SoftWoRx software (Applied Precision/DeltaVision) and corrected for chromatic aberrations.

Confocal microscopy was performed using an upright Leica TCS SP2 AOBS laser scanning microscope. Images were taken with a 63× water objective and 1× zoom. Extended views of the confocal datasets were processed using the Volocity software package (Improvision).

Scanning Electron Microscopy

E10.5 embryos were dissected in PBS at RT and immediately fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% PFA in 0.1M Sodium Cacodylate Buffer, pH 7.4 (Electron Microscopy Sciences) for at least 1 hr at RT. Embryos were stored in fixative for an additional 24 hr at 4°C before processing as described previously 16. Scanning electron micrograph images were taken on a Zeiss SUPRA 25 FESEM.

Cilia measurements

Cilia lengths and widths were measured from a series of representative SEM images of primary cilia located 15-60μm from the ventral midline acquired at 30,000× and 50,000× magnifications. All measurements were processed using ImageJ Software (NIH Image). Length was measured from the tip of cilia to the base. Width was measured from one side of cilia to the other at its widest point. At least three embryos per genotype were analyzed for measurement and at least 30 images were taken for each embryo; total number of cilia counted is indicated in the tables. Non-deconvolved confocal images were used for quantitative analysis of IFT88 and Gli2 immunofluorescence within cilia. Using Metamorph software (Molecular Devices, Downington, PA), a region of interest (ROI) was created using the acetylated α-tubulin channel and transposed to the IFT88 or Gli2 channel and integrated density was measured and reported as arbitrary units (a.u.).

Acknowledgments

We thank Richard Vallee (Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York) for the Dync2h1 antibody, Rajat Rohatgi and Matthew Scott (Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA) for expression constructs used to generate antibodies against Smo and Ptch1, and Scott Weatherbee for help in antibody production. We thank Brad Yoder (University of Alabama at Birmingham) for the mouse Ift88 conditional allele and Alexandra Joyner (MSKCC, New York) for Gli2 and Gli3XtJ mice. We acknowledge Nina Lampen (MSKCC Electron Microscopy Facility) for technical support with scanning electron microscopy; Zsolt Lazar, Yevgeniy Romin and Sho Fujisawa (MSKCC Molecular Cytology Core) for assistance with confocal microscopy and Metamorph analysis, and Shawn Galdeen (Rockefeller University Bio-Imaging Resource Center) for assistance with Deltavision microscopy. We are grateful to members of the Anderson lab and Timothy Bestor (Columbia University Medical Center) for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. Monoclonal antibodies were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, which was developed under the auspices of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and is maintained by the Department of Biological Sciences, University of Iowa. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health R01 NS044385 to KVA.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: P.J.O. and K.V.A. conceived the experiments and wrote the manuscript; P.J.O performed experiments; J.T.E. helped write the manuscript and provided reagents; I.M. provided reagents.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.832

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc3132150?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Article citations

Increased ER stress by depletion of PDIA6 impairs primary ciliogenesis and enhances sensitivity to ferroptosis in kidney cells.

BMB Rep, 57(10):453-458, 01 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39044457 | PMCID: PMC11524824

Molecular and structural perspectives on protein trafficking to the primary cilium membrane.

Biochem Soc Trans, 52(3):1473-1487, 01 Jun 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38864436 | PMCID: PMC11346432

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

SMYD3 Controls Ciliogenesis by Regulating Distinct Centrosomal Proteins and Intraflagellar Transport Trafficking.

Int J Mol Sci, 25(11):6040, 30 May 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38892227 | PMCID: PMC11172885

Involvement of kinesins in skeletal dysplasia: a review.

Am J Physiol Cell Physiol, 327(2):C278-C290, 22 Apr 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38646780 | PMCID: PMC11293425

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

The exocyst complex and intracellular vesicles mediate soluble protein trafficking to the primary cilium.

Commun Biol, 7(1):213, 21 Feb 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38378792 | PMCID: PMC10879184

Go to all (135) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Loss of dynein-2 intermediate chain Wdr34 results in defects in retrograde ciliary protein trafficking and Hedgehog signaling in the mouse.

Hum Mol Genet, 26(13):2386-2397, 01 Jul 2017

Cited by: 18 articles | PMID: 28379358 | PMCID: PMC6075199

Intraflagellar transport protein 122 antagonizes Sonic Hedgehog signaling and controls ciliary localization of pathway components.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 108(4):1456-1461, 05 Jan 2011

Cited by: 130 articles | PMID: 21209331 | PMCID: PMC3029728

Combinations of deletion and missense variations of the dynein-2 DYNC2LI1 subunit found in skeletal ciliopathies cause ciliary defects.

Sci Rep, 12(1):31, 07 Jan 2022

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 34997029 | PMCID: PMC8742128

Architecture of the IFT ciliary trafficking machinery and interplay between its components.

Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol, 55(2):179-196, 01 Apr 2020

Cited by: 39 articles | PMID: 32456460

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NINDS NIH HHS (2)

Grant ID: R01 NS044385

Grant ID: R01 NS044385-10