Abstract

Free full text

NOW AND THEN: The Global Nutrition Transition: The Pandemic of Obesity in Developing Countries

Associated Data

Abstract

Decades ago discussion of an impending global pandemic of obesity was thought of as heresy. Diets in the 1970’s began to shift toward increased reliance upon processed foods, increased away from home intake and greater use of edible oils and sugar-sweetened beverages. Reduced physical activity and increased sedentary time was seen also. These changes began in the early 1990-‘s in the low and middle income world but did not become clearly recognized until diabetes, hypertension and obesity began to dominate the globe. Urban and rural areas from sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia’s poorest countries to the higher income ones are shown to have experienced rapid increases in overweight and obesity status. Concurrent rapid shifts in diet and activity are documented. An array of large-scale programmatic and policy shifts are being explored in a few countries; however despite the major health challenges faced, few countries are serious in addressing prevention of the dietary challenges faced.

INTRODUCTION

Several decades ago, it was heresy to talk about an impending pandemic of obesity across the globe. Clearly diets and activity patterns had changed drastically in the US and by the 1980’s we understood that the dietary quality of US diets were worsening, physical activity was drastically reduced, and obesity was rising across the US and Europe. At that point, only the US was considered a country with an obesity problem: more than half of adults in some age-gender-race-ethnic specific subpopulations were overweight or obese. Home economics was dying as a taught art in the schools, processed food and prepared meals were increasingly common, away from home eating and in particular, fast food, was becoming a major part of our lives, and we became increasingly concerned about a wider array of health conditions related to obesity. In reviewing the original publications on the nutrition transition published in nutrition reviews, there were several key themes 1, 2: urbanization was a major driving force in global obesity, and overweight and obesity were emerging in low and middle income countries. Further, we documented how changes in edible oil production created cheap vegetable oils that allowed low and middle countries to increase energy consumption at very low income levels. However, at that point in history, we assumed global hunger and malnutrition were the dominant concerns in low and middle income countries, and it was very difficult to draw attention to the importance of how dietary and physical activity shifts were increasing the threat of obesity in -these settings.

Over the past several decades a dramatic shift in stages of the way the entire globe eats, drinks and moves have clashed with our biology to create major shifts in body composition. The major mismatches between our biology and modern society that we have addressed in our research and are highlighted in Table 1.3–12

Table 1

Technological Clashes with our biology

| Biology | Technology |

|---|---|

| Sweet preferences | cheap caloric sweeteners, food processing benefits |

| Thirst and hunger/satiety mechanisms not linked | Caloric beverage revolution |

| Fatty food preference | Edible oil revolution-high yield oilseeds, cheap removal of oils |

| Desire to eliminate exertion | Technology in all phases of movement/exertion |

Source: 6

Overweight and obesity were estimated to afflict nearly 1.5 billion adults worldwide in 2008. One estimate, based on data our analysis of new data shows is an undercount, predicted in 2030 globally an estimated 2.16 billion adults will be overweight, and 1.12 billion will be obese13. Below we provide trends data from repeated surveys conducted over the 1990–2010 period over 40 countries with the same methods to suggest possibly 2 or more billion are already overweight or obese today. The implications of these trends for health, quality of life, productivity, and health care costs are staggering. The burden is greater for much of Asia, Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa due to differences in fat patterning and body composition and the cardiometabolic effects of body mass index (BMI) at levels far below standard BMI overweight cutoffs of 25 14, 15. These results are seen in India in relation to the prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose and in China in the prevalence of hypertension and diabetes.

This paper documents the changes in global obesity, describes what countries are doing, with a focus on the potential options low and middle income countries are considering. It provides a comprehensive examination of the state of the art of current knowledge on the diet-related dimension of the changes in the low and middle income world.

OBESITY IN LOW AND MIDDLE-INCOME COUNTRIES

Recent studies have used data from a large number of countries to estimate current prevalence rates and project increases in all regions of the world 13, 16. However, there is little detailed information on longitudinal trends in low- and middle-income countries aside from Brazil, China, India, and Mexico 17, 18. In addition, none of these recent studies have focused on within-country trends related to urban-rural or income/wealth differences. The general impression has been that in higher-income countries we often find greater obesity rates in rural areas and among the poor—the reverse of what is seen in lower-income countries. However, new evidence suggests that these patterns are changing, and the increasing rate of obesity among the poor has important implications for the distribution of health inequalities 19. In the past three decades the age-standardized mean BMI, the most widely used metric for defining overweight and obesity has increased by 0.4–0.5 kilograms/meter2/year 13.

The major gaps in this literature relate to lack of data and superficial examinations of patterns and trends without sufficient attention to the extant literature and the dynamics of change rather than simplistic cross-sectional perspectives. For example, in recent papers, Subramanium and colleagues, using just one wave of data and ignoring dynamics point out that the rich are far more likely than the poor to be obese 16. This is a very different conclusion from Jones-Smith and colleagues, who use similar data, but longitudinal analysis 20, 21. Jones-Smith studied repeated cross-sectional data from women ages 18–49 in 37 developing countries to assess within-country trends in overweight/obesity inequalities by SES between 1989 and 2007 (n = 405,550). Meta-regression was used to examine the associations between GDP and disproportionate increases in overweight prevalence by SES with additional testing for modification by country-level income inequality. In 27 of 37 countries, higher SES (vs. lower) was associated with higher gains in overweight prevalence; in the remaining 10 countries, lower SES (vs. higher) was associated with higher gains in overweight prevalence. GDP was positively related to a faster increase in overweight prevalence among the lower wealth groups. Among countries with a higher GDP, lower income inequality was associated with faster overweight growth among the poor.

Another limitation is the focus on women of childbearing age and preschoolers. This reflects the availability of data from multiple countries which have relied on the Demographic and Health Surveys, which focus on women of childbearing age and their children. A few studies, in particular some national surveys in Mexico and Brazil and a few large-scale longitudinal studies, including the China Health and Nutrition Survey, the Indonesia Family Life Survey, and the Mexico Family Life Survey, cover all age and gender groups 19. Using inclusive data, one sees quite different gender-specific patterns of change and differentials by socioeconomic status. According to the limited research and data available, men with higher socioeconomic status (SES) have higher rates of overweight and obesity than do lower SES men22.

While we know obesity prevalence appears to be rising across all low- and middle-income countries, it is not clear what urban-rural difference may exist. Here we use some recent data we published in other form and rearrange for this review 19, 20. These data provided repeated nationally representative cross-sectional surveys that include 441,916 rural and 364,267 urban (806,183 total) adult women (18–49 years old) from 42 countries in Asia, the Middle East, Africa (East, West, central, and southern), and Latin America. The absolute and relative change in the prevalence of overweight and obesity for women in these countries and the regions are shown in Supplementary Table 1. The combined prevalence of overweight and obesity (overweight = BMI ≥ 25. obesity = BMI ≥ 30; called overweight/obesity hereafter grew for all 42 countries at about 0.7 percentage points per year on average. Using population weights, we estimate that 19 percent of rural women and 37.2 percent of urban women are overweight or obese.

Urban-rural differences and the shifting burden of obesity toward the poor

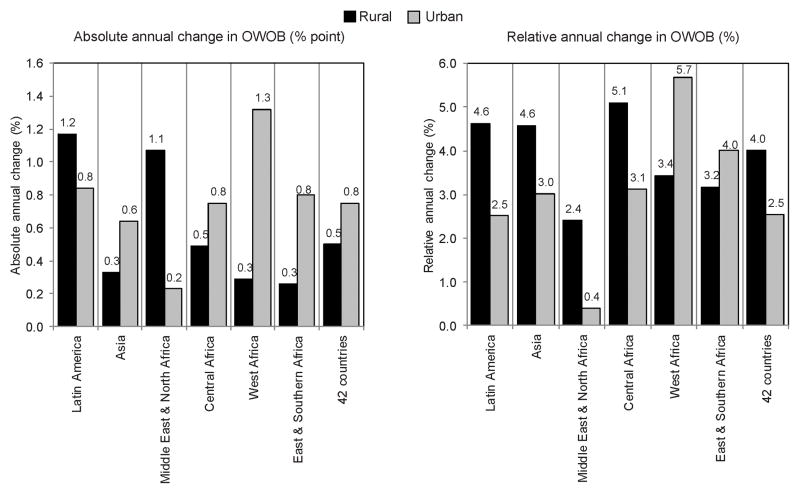

Figure 1 and Supplemental Figure 1 summarize the weighted absolute annual change and relative annual change in the prevalence of overweight/obesity and obesity only, respectively, among rural versus urban women by region. On average, urban women have higher baseline prevalence and larger increases in prevalence of overweight/obesity compared to rural women in the 42 countries (0.8 vs. 0.5 percentage points for overweight; 0.4 vs. 0.2 percentage points for obesity). However, there are regional differences, with rural women in Latin America, the Middle East, and North Africa having much higher increases in prevalence compared to their urban counterparts. However, the relative annual change in weighted prevalence is higher for rural (3.9%) than urban women (2.5%). In other words, women in rural areas are quickly catching-up to their urban counterparts. Supplemental Figure 1 shows the statistics for obesity prevalence, and the results are consistent. The higher relative annual rates of change for obesity compared to overweight suggest that obesity in particular is changing very quickly.

Absolute and relative annual percentage point change in weighted prevalence of overweight and obesity (BMI ≥ 25) among women in rural and urban areas of 42 countries by region (N=42)

We also looked at the data for each of the 42 countries in our study ranked by gross domestic product (GDP) per capita (Supplemental Figure 2). There appears to be little association of residence with prevalence of overweight/obesity among higher GDP countries. Among lower GDP countries, urban women are more likely to be overweight/obese, and countries around the middle and bottom of the GDP distribution have a higher proportion of urban women who are overweight or obese compared to rural women. Statistical analyses show that increased per capita GDP is associated with increases in the absolute annual change in prevalence of overweight/obesity only in rural areas.

KEY FACTORS THAT EXPLAIN INCREASED OBESITY WITH POTENTIAL TO BE CONSIDERED FOR FUTURE PROGRAMMATIC AND POLICY CHANGES?

Ultimately, obesity reflects energy imbalance, so the major areas for intervention relate to dietary intake and energy expenditure, for which the main modifiable component is physical activity. It is clear that large shifts in access to technology have reduced energy expenditure at work in the more labor-intensive occupations, such as farming and mining, as well as in the less energy-intensive service and manufacturing sectors 23. Changes in transportation 24, leisure, and home production 25 relate to reduced physical activity. In addition the complex interplay between biological factors operating during fetal and infant development and these energy imbalances exacerbates many health problems26. Such changes have been well documented for China and are also found in varying manifestations in many countries.

Finding ways to increase physical activity across all age groups is important for public health, but options for increasing energy expenditure through physical activity may be limited in low- and middle-income countries. For instance, to offset any increase of about 110 kcal of food or beverage in average daily energy intake, a women weighing 54 kg must walk moderately fast for 30 minutes and a man weighing 82 kg for about 25 minutes. Such levels of physical activity may be too much to expect, and so diet modification is a key approach to lower obesity prevalence, particularly with the ongoing decline in physical activity and increase in sedentary time (unpublished data). The dietary dynamics represent a major set of complex issues. On the global level, new access to technologies (e.g., cheap edible oils, foods with excessive ‘empty calories’, modern supermarkets, and food distribution and marketing) and regulatory environments (e.g., the World Trade Organization [WTO] and freer flow of goods, services, and technologies) are changing diets in low- and middle-income countries. Accompanying this are all the critical issues of food security and global access to adequate levels of intake. Many populations focus on basic grain and legume food supplies, while the overall transition has shifted the structure of prices and food availability and created a nutrition transition linked with obesity as well as hunger. We have used detailed time use data along with energy expenditures and other data to examine past patterns and trends and predit until 2020 and 2030 patterns of physical activity and sedentary time in the US, UK, Brazil, China, and India (unpublished data).

Prior to exploring the dietary dimension, we consider an important biological factor affecting obesity and chronic diseases in rapidly developing countries in Asia and Africa. This factor is the biological insults suffered during fetal and infant development that may influence susceptibility to the changes described above, thus influencing the development and severity of chronic disease trends for these countries.

Developmental origins of health and disease: Special concerns for low- and middle-income countries

The patterns of change in dietary intake and energy expenditure related to the global nutrition transition are particularly important in the context of current theories of the developmental origins of adult disease. Based on three decades of research, we now recognize that susceptibility to obesity and chronic diseases is influenced by environmental exposures from the time of conception to adulthood. An extensive literature demonstrates that fetal nutritional insufficiency triggers a set of anatomical, hormonal, and physiological changes that enhance survival in a “resource poor” environment 27. However, in a postnatal environment with plentiful resources, these developmental adaptations may contribute to the development of disease. Some of the strongest evidence on the long-term effects of moderate to severe nutrition restriction during pregnancy comes from follow-up of infants born after maternal exposure to famine conditions, such as those experienced in parts of Europe during World War II. For example, A. C. Ravelli and colleagues 28, 29 found higher rates of obesity in 50-year-old men and women whose mothers were exposed to the Dutch famine in the first half of their pregnancies, and G. P. Ravelli and colleagues (Ravelli, Stein et al. 1976) found obesity in 19-year-old men whose mothers experienced famine during their pregnancies. Similarly, a follow-up of Hmong refugee immigrants shows higher rates of central obesity among those raised in a war zone, with effects amplified in those who migrated to the United States compared to those living in a traditional rural setting 30.

The developomental origins theory of mismatch fits closely with the broader issues of mismatch discussed by us below, issues that emerged in our early research1, 2 and later work.31–33 This theory of “mismatch,” that is, early nutritional deficits followed by excesses 34, may be particularly important in low- and middle-income countries undergoing rapid social and economic changes, because economic progress amplifies mismatch 35. Much of the literature on developmental origins of health and disease (DOHAD) focuses on chronic diseases. However, given the strong association of chronic diseases with obesity and in particular with central obesity, this evidence is highly relevant and provides a strong rationale for obesity prevention in populations that have experienced dramatic changes in the nutritional environment as a consequence of the nutrition transition.

Mechanisms are varied but may include affects on the number of nephrons in the kidney 36, glucocorticoid exposure subsequent to maternal stress or poor nutritional status may program the insulin and hypothalamic-pituitary axes for high levels of metabolic efficiency 27, and epigenetic changes. Maternal stress and specific aspects of diet (for example, intake of folate and other methyl donors) can affect DNA methylation and gene expression 37, 38,39. Ongoing studies in places such as India are examining the role of maternal micronutrient intake on epigenetic changes that affect child adiposity 39, 40. Research in India has provided other important insights. Indian infants with poorly nourished mothers are born with weight deficits, but in relative terms the deficits in lean mass are greater than those in adiposity. In later life, when consuming modern high-energy and high-fat diets, the previously “thin-fat” babies also have greater central adiposity 41, 42.

It is apparent from studies of developmental origins of disease that there is a strong intergenerational component to health. While much of the literature on early origins of obesity and associated risk has focused on undernutrition, there is also substantial evidence that maternal overweight and obesity in pregnancy influence disease risk among offspring. For example, gestational diabetes is related to offspring body composition and increased risk of insulin resistance and diabetes in offspring 43, 44. Thus there is concern about an intergenerational amplification of diabetes risk. Women who were malnourished as children are at increased risk of being centrally obese and having impaired glucose tolerance as adults. If these conditions affect a woman’s pregnancy, her offspring are now at increased risk of early development of obesity and diabetes. As obesity develops at younger and younger ages, the likelihood that adolescents and young women will experience pregnancy complications associated with gestational diabetes and hypertension will increase dramatically. There is growing evidence that maternal obesity, even without gestational diabetes, is a risk factor for child obesity through a pathway related to fetal overnutrition (see the review by CH Fall45).

On the other end of the nutrition spectrum, short maternal stature acts as a physical constraint on fetal growth 46, 47. And vitamin and mineral deficiencies and stunting may in turn relate to increased obesity risk 48.

Beyond the fetal period, nutrition and other input to health in infancy, childhood, and adolescence are important determinants of adult body composition and obesity risk. In light of the large increases in overweight and obesity in children as well as adults, attempts have been made to determine the ages at which faster weight gain relates to later obesity. A large literature relates “rapid growth” during infancy to risk of obesity in later childhood and into adulthood 49. In addition, rapid weight gain, particularly from mid-childhood on, is related to increased risk of elevated blood pressure or impaired fasting glucose in young adulthood in low- and middle-income countries 50. Concerns have been raised about the promotion of rapid weight gain in children who are malnourished. In low-income countries catch-up or compensatory growth following a period of faltering growth is desirable, because it is associated with reduced morbidity and improved survival 51,52, 53 and better cognitive development 54. A key concern is whether the benefits of faster growth in these settings outweigh the possible long-term risks. Based on the COHORTS analysis of children from five low- and middle-income countries, faster weight gain in the first two years of life has a number of benefits. It is associated with the development of lean body mass but not with increased risk of impaired fasting glucose or diabetes in young adulthood (papers of team under journal review: e.g., Kuzawa et al 55). Given observations that patterns of child growth have important consequences for the development of obesity and chronic diseases, another line of research focuses on factors that contribute to or protect against early development of adiposity. In this regard, the potential programming roles of early diet have been explored, including the roles of breast-feeding and high intake of dietary protein, fat, and sodium. These topics are important in light of the dramatic changes in diet composition that characterize many populations in the developing world.

Of course, early feeding issues are important. Some studies show a protective effect of breast-feeding on later development of obesity and chronic diseases 56, 57, while other studies show no effects 58. Similarly consistently high protein intake during complementary feeding in the first two years of life has been associated with a higher mean BMI and percentage body fat at age seven in cohort studies of German children 59, and other researchers have suggested a strong link between high protein intake and obesity 60.

Dietary fat may also play a role in the development of NCDs in terms of both the amount of fat and the composition of fats. The STRIP study in Finland demonstrates that lower total and saturated dietary fat intake in infancy results in lower serum cholesterol, LDL-c, and triglyerides (as well as lower blood pressure) in children up to age 14, even without effects on height, weight, or BMI 61, 62. Worldwide the increase in plant oil consumption has increased the intake of n-6 fatty acids and the ratio of n-6 to n-3 fatty acids. This is a concern, because high intake of n-6 fatty acids is associated with altered immune function, differentiation of preadipocytes into mature fat cells, and changes in fat deposition patterns. Another study relates high sodium intake from infant formula and weaning foods to increased blood pressure in adulthood 63.

Dietary changes

The knowledge emerging with the developmental origins research provides only one dimension of the shift toward greater obesity. While early life exposures and biological insults appear to enhance the adverse effects of dietary change, in the end shifts in energy balance and the entire structure of the diet have played major concomitant and separate roles. We speak first of broad trends and then return to the issues of poverty and availability. These link the set of dynamic changes in our food supply with food security.

It is useful to understand how vastly diets have changed across the low- and medium-income world to converge on what we often term the “Western diet.” This is broadly defined by high intake of refined carbohydrates, added sugars, fats, and animal-source foods. Data available for low- and middle-income countries document this trend in all urban areas and increasingly in rural areas. Diets rich in legumes, other vegetables, and coarse grains are disappearing in all regions and countries. Some major global developments in technology have been behind this shift.

Edible oil–vegetable oil revolution

Fats have major benefits in improving flavor. Some scientists suggest that the selection of fat- as opposed to carbohydrate-rich foods is primarily determined by brain mechanisms that may include central levels of neurotransmitters, hormones, or neuropeptides 1. In the 1950s and 1960s in the United States and Japan, technology was developed to cheaply remove oils from oilseeds (corn, soybean, cottonseed, red palm seeds, etc.) 1. Breeding techniques to increase the oil content of these seeds accompanied the shifts, and higher-income countries saw a large increase in the availability of cheap vegetable oils. This was followed by removal of the erucic acid from rapeseed oil to create healthier canola oil accompanied by extensive research on the good and bad components of each edible oil (e.g., trans fats and specific fatty acids). By 2010 inexpensive oils were available throughout the developing world. Between 1985 and 2010 individual intake of vegetable oils increased threefold to sixfold, depending on the subpopulation studied. In China, which has moderate but not high vegetable oil intake, persons age two and older now consume on average almost 300 calories and more than 30 grams of vegetable oil daily 64.

Caloric sweeteners

The globe’s diet is much sweeter today than heretofore 65. For example, 75 percent of foods and beverages bought in the US contain added caloric sweeteners and the average American aged 2 and older consumes about 375kcal/day 66, 67. In the United States, one of the few countries where the added sugar in the diet is estimated 68, research has shown a remarkable stability of added sugar intake from food over the last 30 years, while added sugar from beverages has increased significantly 66. In 1977–78 two-thirds of added sugar in the US diet came from food, but today two-thirds comes from beverages. However, this may be an underestimate, as the USDA added-sugar estimate excludes fruit juice concentrate, a source of sugar that has seen major increases in consumption in the last decade and is now found in over 10 percent of US foods (unpublished data). Mexico, which experienced a doubling of caloric beverage intake to more than 21 percent of the kilocalories/day for all age groups from 1996 to 2002 is one of the few developing countries with data on caloric beverage patterns and trends 31, 69, 70. While individual dietary intake data are not available for most low-income countries, national aggregate data on sugar available for consumption (food disappearance or food balance data) suggest that this is a major concern in all regions of the world 65.

Shift toward increased animal-source food intake

Earlier research by C. L. Delgado and others at the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) found the beginning of a livestock revolution in the developing world 71. Subsequent research by Popkin and others has shown major increases in production of beef, pork, dairy products, eggs, and poultry across low-and middle-income countries 72, 73. Most of the global increases in animal-source foods have been in low- and middle-income countries. For example, India has had a major increase in consumption of dairy products and China in pork and eggs, among others.

The increase in animal-source food products has both positive and adverse health effects. On the one hand, for poor individuals throughout the developing world a few extra grams of animal-source foods can significantly improve the micronutrient profile of food consumed. On the other hand, excessive consumption of animal-source foods is linked with excessive saturated fat intake and increased mortality 74,75.

Reduced intake of legumes, coarse grains, and other vegetables

While significant systematic research on the reduced consumption of these nutritionally important foods has not been undertaken, it is clear from case studies that consumption of beans, a vast array of bean products, and what we term often ‘coarse’ grains such as sorghum and millet has declined significantly 6, 76, 77. This occurred from the 1960s through the 1980s in the United States and more recently across Asia and the rest of the Americas 78.

Understanding the reasons for the trend toward increased consumption of animal-source food, oils, and caloric sweeteners and reduced consumption of legumes, coarse grains, and other vegetables begins with understanding the relative price structure shifts since World War II. Most of these changes are purposeful and relate to agricultural policies across the globe 6, 79.

Food system changes

In the past 10 to 15 years, several factors have influenced the food supply of each country. The food system characterizing most urban and an increasing proportion of rural areas across low- and middle-income countries has changed drastically with globalized distribution of technology related to food production, transportation and marketing, mass media, and the flow of capital and services. Access to many new empty calorie foods and beverages relates to current economic and social development. Modern food technology has provided enormous benefits in reducing food waste, enhancing sanitation, and reducing many adverse effects of seasonality, among the myriad benefits. Similarly the same is true for the modern supermarket. Here we highlight some of the potential adverse effects of these important changes while acknowledging critical benefits to producers and consumers.

A key component is modern food distribution and sales. This reflects the enormous penetration of super- and mega-market companies throughout the developing world 80. Most countries also have large convenience store chains. The fresh market (wet or open public market) is disappearing as the major source of food in the developing world. These markets are being replaced by large regional and local supermarkets, which are usually part of multinational chains (e.g., Carrefour or Walmart) or, in countries such as South Africa and China, by domestic chains that function and look like the global chains. Increasingly, hypermarkets (megastores) are the major force driving changing food expenditures in a country or a region. For example, in Latin America supermarkets’ share of all retail food sales increased from 15 percent in 1990 to 60 percent by 2000. In comparison, supermarkets accounted for 80 percent of retail food sales in the United States in 2000. This process is also occurring at varying rates in Asia, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and all urban areas of Africa. We will undertake a national survey of diet and related factors in India in 2012.

One study suggests that the shifts in the food environment might enhance intake of processed, lower-quality foods81. Carlos Monteiro has been particularly clear in his concern that this modern food environment has impacted diets 4, 5, 82. Indeed his concern regarding processing meshes well with the vast shift away from consumption of legumes and coarse grains to consumption of refined grains purchased at modern supermarkets and convenience stores, which have penetrated urban Africa and Asia and most of the Middle East and Latin America.

The potential adverse effects of these trends are increased access to cheaper processed, high-fat, added-sugar, and salt-laden foods in developing countries. At the same time, they are the purveyors of some good. For example, supermarkets were instrumental in the development of ultra-heat treatment (UHT) for pasteurization of milk, giving it a long shelf life (not requiring refrigeration) and providing a safe source of milk for all income groups. Supermarkets were also key players in establishing food safety standards 83. Most importantly, they solved the cold chain problem and in many instances have brought higher-quality produce to the urban consumer throughout the year. Other factors include the liberalization of direct foreign investment, trade liberalization, and the saturation of Western markets that has pushed growing companies into other locales. Improvements in the logistics and procurement systems used by supermarkets have allowed them to compete, on cost, with the more typical outlets in developing countries—the small mom-and-pop stores and wet markets (fresh or open public markets) for fruits, vegetables, and all other products.

Another result of the global changes in food consumption is the freer flow in food trade linked with the WTO. For instance, barriers to edible oil imports have been reduced, and vegetable oil production has been centralized to compete with imports and to significantly lower prices of vegetable oil in countries such as China.

These changes along with global investments in agriculture over the last half century have produced a large shift in relative prices to favor animal-source foods, edible oils, and other key global commodities, including sugar 79. Supplemental Figure 3, reproduced from research at the IFPRI, highlights some of the global trends that have resulted from the vast investment in the animal foods sector and feed crops across the globe 71, 79. Supplemental Figure 4 highlights the real shifts in China in relative costs of selected foods based on data from 330 communities and their food markets 84.

Food security and the dual burden of undernutrition and obesity

This rapid transition in income and diet and the large shift toward animal-source food consumption creates major demands for basic grains to feed livestock, disregarding the needs of the poor for the same food supply. While drought, climate change, and increased demand for ethanol have contributed to global food prices, the longer-term structural shift relates to demand for animal-source food and its impact on corn, rice, and wheat prices. In the face of the need for basic foods for the poor, the marketing, desirability, and availability of low-cost edible oils, empty calorie foods, and such have encouraged urban poor people to consume lower-quality foods that are obesogenic (most likely more processed foods, but this has not yet been documented). These complex changes are reflected in the emergence of obesity alongside hunger even in the same households.

Families faced with an inability to grow food or inadequate income to purchase food will likely opt for the cheapest cost per calorie from the available choices. When food prices for basic grains double or triple, the pressures to adjust food purchases increase. Among the most salient issues are the vulnerability of poor female-headed households 85 and the combination of price increases and volatility in global food markets (linked also with climate change issues). It is also important to note that the relative price changes matter most. If prices of fatty foods, oils, sugar, and animal-source foods go down relative to legumes, fruits, and other vegetables, the latter items become less attractive.

Despite substantial economic growth, large inequalities remain in many low- and middle-income countries, and it is common to see problems of underweight, stunting, and micronutrient deficiencies side by side with increasing rates of obesity. This “dual burden” of undernutrition and obesity exists not only in countries and communities 86 but in households 87, 88 and even in individuals, who may have excess adiposity along with micronutrient deficiencies, such as iron deficiency anemia 87–90, or stunting and overweight. Dual burden households are most common in countries undergoing the nutrition transition 87, 88 and may reflect gender or generation differences in food allocation related to social norms. For example, high-quality foods may be given preferentially to adult males rather than to children. But other patterns may exist. In China it is common to indulge children in the wake of the one-child population control strategy 91, 92. Individuals of different generations may also respond differently to social and economic changes, with the younger generation adopting new dietary patterns more quickly while the elderly continue to eat in more traditional (and sometimes healthier) ways.

A challenge for programs and policies is the need to address food insecurity and hunger without adding to the burden of overweight and obesity. This is particularly challenging given the relatively low cost and high availability of energy-dense but low-micronutrient-content foods. Again it is relative prices that matter. The lack of focus on coarse grains, legumes, and other vegetables and the vast attention to sugar crops, oilseeds, vegetable oil technologies, and cheaper animal-source foods have contributed to the global shift in diets.

In countries such as Mexico, Brazil, Chile, and China, where great strides have been made to minimize acute malnutrition through programs targeting vulnerable subpopulations, hunger and malnutrition have been reduced. An example is Oportunidades in Mexico, the conditional cash transfer program that provides a stipend and complementary food for preschoolers 93, 94. These countries recognize that the programs must be tailored to address malnutrition while not accelerating energy imbalance and obesity among the recipients, as has occurred in some programs 93, 95. For instance, Chile continued to feed young children in its various feeding programs even when most were adequately nourished and did not revise the programs to deal with energy imbalance issues for some time after they reduced undernutrition 95. The Mexican government found a need to reduce the fat content of the milk along with other changes in its feeding programs to address problems of child obesity.

CURRENT EXPERIENCES AND MAJOR INITIATIVES

One of the major gaps in the area of large-scale health-related interventions is the need for rigorous evaluation of existing programs and initiatives followed by refinements to enhance their efficacy. In fact, with one exception, across the globe there are no rigorous evaluations or reviews of interventions in terms of their impact on diet or obesity. The one exception is the evaluations in Mexico of welfare and feeding programs’ effects on obesity 93, 95. This was designed as part of a large quasi-experimental study of welfare in Mexico and was not designed to examine the food component. Thus it is impossible to highlight in any unbiased manner what might and might not work. In essence, no funding has existed for evaluation activities across the low- and middle-income world.

The lack of appropriate technology and environments to foster beneficial change is a critical health issue. In many ways it would be ideal to refocus attention on these points and away from what is often perceived as irrational behavior and ignorance in individual and household consumption patterns. Across the globe, the major focus is on education. This focus is identical to the way agriculture systems created farmers across the globe. Ignoring environmental determinants, outsiders assumed the poor were ignorant, lazy, illiterate peasants who would never change without technology, and programs suffered from problems of approach. With an understanding of appropriate versus inappropriate technologies and the rationale behind decisions by farmers and others, the development approach to agriculture changed completely 96 and began to appreciate the interplay of literacy and education with technology and extension 97. However, in the health sector and in public health education there remains a perception that providing the buildings and the technologies will accomplish set goals.

Institutional and large-scale feeding programs

Refer back to the earlier section on feeding program. Most of the large-scale initiatives in Brazil, Mexico, and Chile, where there have been efforts to systematically address obesity, have focused on schools 98.

Education: Labeling and front-of-the-package initiatives

Front-of-the-package labeling provides information that helps consumers make healthier food choices and stimulates product reformulation. This began globally with a desire to reduce saturated and trans fats, added salt, and added sugar in ‘empty calorie foods’ and to enhance fruit, vegetable, and whole grain intake while limiting energy intake. The most common approach is that promoted by an international program led by scientists at the Choices International Foundation. This product-specific nutrient-profiling approach has developed food categories, revised them to meet unique country- and region-specific dietary needs, and created food group–specific nutrition criteria to show what is a healthy choice 99. Recently the US Institute of Medicine recommended a single front of a package design somewhat similar to the Choices approach though the deliberations are still in process 100, 101.

Underlying this system is the need for reformulations of a vast array of products to enhance their healthfulness. For instance, there are at least 200,000 packaged foods and beverages in the United States with unique formulations 67. Reducing their energy content and enhancing their quality is linked with this front-of-the-package effort.

Regulations regarding beverages and food marketing

The World Health Organization (WHO) and others have called for regulations to minimize or eliminate marketing of less healthy foods and to consider ways to control sugary beverage consumption.

Brazil and Chile have initiated controls over the marketing of unhealthful foods with an official national code of marketing. A second initiative relates to control of sugar-sweetened beverages (sugar-sweetened beverages). A large number of global health groups (concerned with diabetes, heart disease, and cancer) have called for reduction of sugar-sweetened beverage intake. In some cases this has included 100 percent fruit juice and in all cases has included carbonated sugar-sweetened beverages, fruit drinks, energy drinks, sports drinks, and vitamin waters. More than 20 countries have eliminated vending machines in schools and prevent sales of these less healthful beverages on school grounds.

Mexico is one of the few low- or middle-income countries to aggressively move against sugar sweetened beverages and other high-calorie, less healthful beverages (e.g., full fat whole milk vs. 1 percent, reduced fat milk). In Mexico the Ministry of Health created a set of beverage guidelines that the government used to change procedures in their feeding and welfare programs and in schools 31. An as yet unaddressed area is foods high in saturated fats and added sugars. Called ‘junk foods’ or foods with excessive ‘empty calories’, these represent an increasing component of diets across the globe 4, 5, 82, 102. There is very limited research to show what increased costs of such foods might do to overall diets 103. Would people just substitute other refined carbohydrates or fried foods? Would calories be cut? Could this lead to healthier food choices? There is a great need for small- and large-scale studies that are well monitored and evaluated on such activities prior to promoting them, and there is a need for research using extant data to understand how price shifts might affect the structure of diets.

Schools

As noted above, countries throughout the globe have focused on school feeding and vending policies. Examples as simple as providing potable water along with water education show that even small efforts with an initial investment and small marginal costs can have an impact 104.

Unique country issues

While there are unique issues in many countries, we only focus on Mexico to limit space. Mexico experienced one of the world’s largest increases in obesity, diabetes, and cardiometabolic diseases in the 1990–2010 105–107. It is one of the very few countries aggressively pursuing a full-scale effort to slow down and reverse the obesity trend. First, the government took on calories consumed from beverages, including excessive calories from whole milk, sugar-sweetened beverages, and heavily sweetened agua frescas (fruit juice, water, and added sugar)31. Among the major actions of the government’s Beverage Guidance Panel was removal of all whole milk from government programs and replacement with 1.5 percent milk. This was followed by an Obesity Prevention Strategy signed by all ministers and the president. More recently, an agreement between the major Mexican food companies and the Ministries of Health and Education removed most high-sugar and high–saturated fat foods and beverages from schools. The government also established a front-of-the-package initiative to provide Ministry of Health–approved healthy food labels for foods with reduced sodium, sugar, and saturated fats and more healthful components.

Asian countries aside from Singapore and Thailand have done little. In Thailand, led by key nutritionists and Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn, the government has started a number of infant feeding and school initiatives related to obesity prevention. They have revised food labeling, increased promotion of fruits and vegetables, and worked on fat and oil reduction, but as yet they have not invested significant resources or developed a comprehensive program.

In Latin America, Brazil and Chile are initiating a number of issues; however the will has and will continue to come up against food industry concerns as consumption of highly processed and unhealthful foods is found in schools and elsewhere 108.

FUTURE OPTIONS AT THE COMMUNITY AND LARGE-SCALE LEVELS

Our prime focus if we are to prevent obesity and reduce the rapid increases in global obesity must be on the food supply and improving the quality of diets while reducing total caloric intake. From the intervention, programmatic, and policy perspective, this is the area with most potential. Will interventions in pregnancy and infancy represent the key to preventing future overweight? Can such interventions work without major shifts in energy imbalance and thus in diets in later life?

A second and equally important set of questions relates to improving diets at all ages. Can we recover all the healthful elements of diets lost over the last half century (e.g., beans or legumes from many countries, coarse grains and whole grain products from others, vegetables from many)? How do we reduce the excessive consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, fatty, salty and sugary refined carbohydrate foods termed ultra-processed foods by Monteiro, ‘junk foods’ by some, and empty calorie food by others 4, 5, 68, 109, 110. Are measurement methods in the current food systems adequate to address our concerns about diet quality and quantity 67? While changes in food systems are linked with dietary shifts, the changes in the overall global food systems are so profound for low- and middle-income countries that we discuss this briefly as a third concern. A fourth area relates to the health sector and its role in addressing these food and nutrition issues. Is its role to advocate and work for regulations or to work with others to educate the public? Fifth, we find food insecurity, major constraints on the poor, and many of the issues of poverty and low education affecting obesity just as they affect differentially the problems of hunger and malnutrition. What can the food insecurity literature suggest about addressing obesity in the developing world?

Direct feeding, care, and prevention interventions at the community level

What options emerge from the developmental origins?

Consideration of the developmental origins of obesity and chronic diseases is important because (1) there is strong evidence to support a role for early life exposures in the development of later disease risk, (2) there is potential for intergenerational amplification of risk, and (3) prevention efforts can capitalize on the same developmental plasticity that alters susceptibility to disease to intervene early to prevent obesity. The “greatest leverage in terms of reduction of risk can be achieved through a timely intervention in the developmentally plastic phase” 35, 111.

The first 1,000 days

Current focus for child survival and healthy growth and development in resource-poor settings is on the “first 1,000 days 112”.

This begins with pregnancy with attention to ensuring high diet quality, including micronutrient adequacy, and to optimizing pregnancy weight gain, avoiding inadequate as well as excessive gains 113. However, since early pregnancy matters, it is vital that interventions optimize the health and nutritional status of young women prior to pregnancy. This implies a need to focus on the period from childhood to adolescence as well to promote linear growth, minimize excess gains in adiposity, and establish health patterns of diet and physical activity. Recent attention has focused on young girls as an important target for improving health (e.g., Center for Global Development, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Start with a Girl: A New Agenda for Global Health [http://www.cgdev.org/content/publications/detail/1422899/], and Girls Count: A Global Investment and Action Agenda [http://www.cgdev.org/content/publications/detail/15154]). This focus is also important in light of the fact that in several low- and middle-income countries, such as South Africa and Guatemala, obesity increases sharply in girls in the years following menarche 114, putting young women at risk for pregnancies complicated by obesity as well as micronutrient deficiencies.

Some adverse feeding affects deserve careful consideration in program and policy work. Limited evidence from randomized clinical trials in high-income settings shows that a higher protein content in infant formula is associated with higher weight in the first two years of life but has no effect on linear growth 115 and that feeding a nutrient-enriched formula to infants who are small for their gestational age is related to higher fat mass in mid-childhood 116. In Finland a randomized study of individualized dietary and lifestyle counseling to reduce intake of saturated fat decreased the prevalence of overweight in school-age girls 117. These studies demonstrate the potential for dietary modification to influence obesity risk. Experimental evidence from low- and middle-income settings on dietary interventions to reduce obesity in infancy and childhood is lacking. Most nutrition intervention trials have been geared toward the amelioration of stunting and enhancement of growth of malnourished children.

Research is needed to define an optimal weaning and early child diet that promotes linear growth and lean body mass while minimizing excess adiposity. An extensive literature has explored whether breast-feeding reduces the risk of child obesity and generally finds only small or minimal protective effects. However, breast-feeding is well known to contribute to healthy growth and to reduce stunting, which is in turn associated with later overweight in low-income populations 118. Thus breast-feeding promotion has value in the context of obesity prevention in low- and middle-income countries.

While there is an appreciation of the potential importance of intervening in pregnancy and infancy to prevent later obesity 35, 119, there is a lack of specificity about the components of potentially successful interventions. This reflects a lack of knowledge relevant to early obesity prevention in low- and middle-income countries. Moreover, investigators are just now beginning to assess the relative importance and potential impact of prenatal versus postnatal effects and the relative importance of different periods (infancy, childhood, adolescence). Owing to the relatively recent acceptance of the premises put forth to support developmental origins of adult disease risk and the need for long-term cohort studies to test interventions, there is as yet no empirical evidence to support such efforts as a means to influence obesity and chronic disease risk. However, several trials have been initiated. For example, in India R. Yajnik and colleagues in Poona have begun to provide nutritional supplements to adolescent girls prior to and during pregnancy.

Clearly, there is a large unmet need to explore the implications of interventions based on developmental origins concepts, but it is key to include a life course perspective that recognizes intergenerational risks and the importance of infant and young child nutrition. Given the persistent problems of poor nutrition (stunting, impaired intellectual development, increased morbidity) that coexist with the development of child obesity, it is critical that interventions be geared to optimize nutritional status through careful attention to diet quality and composition with the aim to enhance linear growth, eliminate micronutrient deficiencies, and prevent obesity.

The focus on food supply

We are always faced with the question why can’t we just return to earlier, healthier components of traditional diets in Asia, Africa, and other transitional regions of the world? We follow a set of options grouped in a manner consistent with a set of options used by the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF).

Food fiscal measures

Are there ways to shift diets back to healthier components? Can we alter relative prices? Can we learn ways to promote legumes and other vegetables that link naturally with food system development? A major area of concern across the globe is the loss of overall healthy dietary patterns and the removal of key components of the diet. The thinking is that since we shifted dietary patterns greatly in a matter of 10 to 20 years, we can shift back just as readily. The first problem is the relative prices of the foods consumed as basic staples prior to the major dietary changes of the past 20 to 50 years. These include whole grains, legumes, other vegetables, and fruits that many scholars felt were part of the healthier components of diets across the globe before the 1960s. Relative prices globally have reduced the cost of animal-source foods, oils, sugar, and related products 79. Removal of subsidies in the United States and Europe might not appreciably alter the relatively lower prices of animal-source foods, oils, and sweeteners, among others 120, 121. In contrast, there is no research on the role of subsidies in the shift in the overall structure of diets in low- and middle-income countries. Such work is needed to fully understand if government interventions, which are numerous in most Asian, African, and Latin American countries, affect adversely the quality of the diet and are linked with excessive caloric intake. In 1989, Drs. B. Popkin and Per Pinstrup-Andersen helped organize a conference in China that discussed the future problems with obesity, the large subsidies of fatty pork, and the reduced intake of legumes, especially soy and soy products, in China. The Chinese Ministry of Agriculture made a small effort to reduce the pork subsidy (the conference was a joint Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences effort, and the Ministries of Health, Rural Development, and Agriculture were involved) 120, 121,122. It is unclear if we could return relative pricing and preferences to more healthful foods, but this represents one key global long-term goal.

One of the major targets of efforts to rapidly improve public health has been taxation of selected foods and beverages, in particular sugar-sweetened beverages. Many countries have initiated discussion or attempted to add sugar-sweetened beverage taxation, and global organizations, such as the World Cancer Research Fund and the World Heart Federation, have made this central to their work. Mexico provides a prime example of a government initiative to control sugar-sweetened beverages and reduce calories consumed from beverages 31, 69, 70. Over 20 countries have banned all sugary beverages from schools; about 12 have banned 100% fruit juice also. Limited literature supports the potential benefits of taxation of sugary beverages 7, 12,123–126.

Monteiro has raised the controversial question can we remove some of the heavy reliance on ultraprocessed food? He defines “ultraprocessed foods” as basically confections of processed foods, typically with sophisticated use of additives to make them edible, palatable, and habit-forming which he feels have no real resemblance to regular food (commodities such as produce or meat), although Monteiro states that they may be shaped, labeled, and marketed to seem wholesome and “fresh” 4, 5, 82. Monteiro claims that ultraprocessed foods are a problem, because they readily induce overeating and are a major source of ‘empty calories’. In many ways this argument echoes the desire of Michael Pollan and other authors around the globe who want us to return to consuming basic commodities like fruits, vegetables, poultry, and other meat but no ultraprocessed foods (or very limited use of such foods) 127.

Given the dominance of a large complex chain of food handling from farm to consumer, with varying degrees of processing affecting all foods, it is hard to know what to label an ultraprocessed food. Further, the practicality of these initiatives from both a global hunger and an environmental perspective has yet to be examined. In the case of ultraprocessed food, one question is can we go back to healthier food for the large populations across the globe? For elites, income, time, and price constraints may not be as constraining and such shifts may be occurring as evidenced by the re-birth of farmers markets (wet markets) across the US and other high income countries, the Slow Food movement across the growth, and even the growth of the organic food in our global food supply. However, globalization of the food supply, increases in processing and preservation, and ultraprocessing of food may be so far along that it is impossible to return to simpler, earlier ways of obtaining food and preparing it.

Private sector voluntary initiatives

Can we work with global and national food companies to enhance the quality and reduce the caloric content of processed foods? Will voluntary initiatives work? Will food companies promote regulatory and other policy changes that address global obesity? Or can we succeed in improving diets if global companies (many of which are bigger than some nations in income and assets) do not cooperate and work with us? These are complex, almost impossible to answer questions, and history has shown that cooperation is only possible in some cases. Many use the example of the battle against smoking behavior and tobacco use as the approach to be used in addressing the ‘bad’ elements of the food supply 128, 129. However, the scope and reach of the food companies is far greater than that of the tobacco companies and the need for all consumers to eat some food lead to complex issues when we begin to focus what many feel is an essential point—there are ‘good’ foods to be encourage and ‘bad ‘foods to be discouraged and one can not longer rely on consumers to eat a ‘healthful’ diet.

Currently there are several major global initiatives. The only one that seems promising is the potential reduction of total calories proposed by 17 leading companies. Their commitment in the United States is to remove 1.5 trillion calories from the total US supply of processed foods they sell by 2015. They have made no explicit agreements with other countries on the exact calorie reduction; however, they are negotiating a similar arrangement at least in Australia. The US arrangement is under the umbrella of the Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation (http://www.healthyweightcommit.org/). The University of North Carolina (UNC) Food Research Program team is the official outside evaluator of that effort. Even in the United States these global giants control only about 25–30 percent of the total calories consumed. Therefore there are questions not only about the true effectiveness of the changes in their own sales but also about the substitutions of other packaged and processed food and beverage products and other sources of calories.

Walmart is leading a second initiative in which it has pledged to cut its calories sold, albeit without a solid exact pledge or a strong external evaluation plan. Furthermore, it is unclear how Walmart will translate this pledge made in the United States into its global stores. There is no clear evidence that these voluntary pledges will produce changes even for the global companies 130, 131. To date studies on topics such as control of mass media marketing to children provide little evidence of any positive impact 132. Furthermore, these voluntary efforts seem focused on the United States, Europe, or other high-income countries and not the low- and middle-income world.

There is a key additional element. Global food companies are the major components of sales of certain categories of foods, such as sugar-sweetened beverages, in low- and middle-income countries. However, there are numerous local food preparers, processors, and distributors. Even if global food companies did indeed reduce the caloric content of their sales, it is unclear whether this would be replaced by local competitors. Our group is attempting to determine if we can even measure the reach of global food companies in countries as diverse as the United States and China. In higher-income countries, where governance is open, it is simpler to do so, but across the globe the roles of global companies become much murkier and often impossible to gauge accurately as ownership is not publicly obtainable. Further, there is the indirect impact of these companies on how foods are produced, processed, and distributed and even what companies want to market as food and drink 133. J.L. Watson and his colleagues showed how the introduction of McDonald’s into Hong Kong, China, Taiwan, Japan, and other Asian countries affected the entire culture of food service and preparation in other restaurants 133.

The United States and Western Europe have implemented food safety and labeling controls and careful monitoring of many components of marketed food, but what will happen as global food and agribusiness companies become active in low- and middle-income transitional economies? As with tobacco, will ‘junk food’ and unethical marketing be focused on low- and middle-income countries? Our UNC team has found some evidence of this in the sugar-sweetened beverage area 3. We conducted a case study of the two largest and most influential producers of sweetened beverages, the Coca-Cola Company and PepsiCo, who together control 34 percent of the global soft drink market and 69% of the carbonated soft drink market. We examined how they adjusted their product portfolios globally and in three critical markets (the United States, Brazil, and China) in 2000–2010. On a global basis, total revenues and calories per capita sold increased. In the United States both total calories per capita and calories per ounce sold decreased, while the opposite was true in the developing markets of Brazil and China. Total calories per capita increased greatly in China and to a lesser extent in Brazil 3. It is quite possible that such shifts will cross into many other sectors.

Healthy public policies

Where does the public health system fit into this? In many countries the modern medical sector represents a major contact point for individuals during critical times in the life cycle (pregnancy, infancy, aging). Also modern medical practitioners are held in high esteem. The public health sector in particular plays a major role in its contact with individuals and families in many countries. At the same time, when it comes to guidance related to obesity, there are few examples at the provincial/state or national levels in which this sector has been mobilized and effectively used to prevent obesity. Rarely is there evidence that nurses, physicians, and other medical professionals raise and discuss intelligently the issues of proper diet and physical activity patterns.

Negative effects of current programs focused traditionally on undernutrition

As the experiences in Mexico and Brazil show, traditional poverty alleviation and food programs can have unforeseen consequences, especially in environments where activity patterns have shifted toward more sedentary activity. Are there current food and nutrition programs that actually increase the risk of obesity in Asia, the Middle East, and Africa? What about other macroeconomic policies? This again is an under-researched area.

As noted in studies in Chile and Mexico, there is the potential that current feeding programs can be focused on reducing hunger and malnutrition, but instead of additional calories their target populations may need higher-quality foods. The outcome may be increased weight gain and obesity 93, 95, 134. We know little about this issue globally, since, given the focus on prevention or treatment of undernutrition, data have not been systematically evaluated for potential effects on excess weight gain and obesity. As countries make the transition from reduced hunger and poverty toward less constrained food supplies, increased incomes, and modern infrastructure, there is a concomitant reduction in physical activity and in the quality of foods consumed, a clear trend toward overweight and obesity.

Can schools promote change?

One issue is the large global shift toward precooked and preprepared highly processed empty calorie food. In many countries, knowledge about foods and skills in food preparation and cooking are being lost as new generations grow increasingly reliant on food prepared in locations outside the home 6, 135. The United Kingdom built kitchens to teach cooking to boys and girls in middle schools throughout the entire country 136–139. Can school gardens and exercises in understanding food and food preparation encourage the next generation to cook and consume healthier food? Little is known about this option.

A few studies suggest that such options might work, but rigorous evaluations do not exist. Nevertheless, in South Korea a generation of young housewives was trained to cook traditional low-fat and healthy vegetable dishes. This was linked to high vegetable intake and low fat intake 140, 141. Similarly, there is some evidence that training several generations of women in France to cook with portion controls might have been important for reduced portion sizes in France

Trade

Globalization and the WTO are often credited with opening the globe to free trade in food and services 142. There are effects such as reduced edible oil prices and increased intake of these oils in China that can be linked to specific agreements, such as those addressing trade barriers to imports. However, modernization and increased trade go hand in hand with improvements in the quality of living that no countries would willingly forego. The gap is in our knowledge of specific components of trade agreements that might adversely affect diet and the effects of trade policies and economic policies on dietary patterns.

Unhealthy food marketing to kids

A prime area of concern is how food marketing to children contributes to an obesogenic environment. The role of media—televisions, computers, notebooks, or cell phones—has expanded in use and impact. The media have ready access to the consumer, and the global penetration is such that not a household, village, or urban sector is missed. At the same time, product placement in movies, on billboards, and elsewhere has created an environment where children and adults are assaulted with a vision of eating and drinking that is creating global shifts in food demand. A prime target is media control, though all initiatives to date focus only on children and not on the total environment, as occurred with the tobacco controls 128, 129, 143, 144. Control of advertising represents a major aspect of tobacco control in countries that have seriously reduced tobacco use. There may be important lessons from the tobacco story that are relevant for food.

Public sector healthy food service policies

The public sector feeds enormous numbers of individuals in schools, hospitals, and government departments. Improving the quality of food served in these institutions remains another key option 98. As with the marketing of foods, minimal evaluations of initiatives in this sector as they relate to diet and body composition have been completed.

Food and nutrition labeling

Food labeling is emerging as a major global option. In Latin America, Asia, and Africa the focus is not only on providing “nutrition facts” panels on foods but also on developing systems for identifying which foods and beverages are deemed healthy according to the food customs of each country and global initiatives to reduce added sugar, trans fats, other saturated fats, and added sodium while encouraging whole grain, fruit, legume, and other vegetable consumption 99. India, China, Brazil, Mexico, South Africa, and Chile are considering such initiatives. This is a very promising option as the global food supply increases in complexity and consumers across the globe increasingly shift to processed and packaged foods and to shopping in commercial chains, be they convenience stores, grocery stores, supermarkets, or megamarts.

CONCLUSION: THEN AND NOW

The shifts in how we eat and drink and energy imbalance, overweight and obesity, and the vast array of other nutrition-related cardiometabolic problems have shifted so greatly in the past half century. Unfortunately we do not truly have the data to document how this change compares with others over our evolution. However, from the perspective of one concerned with our attaining a healthy diet and healthier body composition, it appears as if many adverse changes have accelerated in the past several decades across the globe. This does not mean that people perceive these changes as being harmful. In contrast, the increased fatty, sweet and salty diet, the interesting beverages with great flavors, and the convenient, safer sets of food bring many benefits. It is figuring a way to return to a healthier, and in many cases, less processed diet with more nutrient dense, healthier foods is critical. To prevent future problems and to provide for those with nutrition-related noncommunicable diseases, be they obesity, diabetes, a cancer or others, we must find ways to improve the dietary patterns of the globe. Focusing on medical treatment and reduction of smoking and sodium in the diet will not address the epidemic of obesity, many other cardiometabolic problems and all the related economic, health, and other consequences facing low- and middle-income countries. Effective action requires evidence-based carefully evaluated programs and policies. This paper summarizes a great deal of work that has occurred since the concerns in the past half century have alerted us and others to consider the rapid shift in stages of diet.

Supplementary Material

Supp Figure S1

Figure S1. Absolute and relative annual percentage point change in weighted prevalence of obesity (BMI ≥ 30) among women in rural and urban areas of 42 countries by region (N=42)

Supp Figure S2

Figure S2. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among women 18–49 years old ranked by GDP per capita in 2009 US dollars (N=42)

Supp Figure S3

Figure S3. Trends in Global Prices for Beef, 1990 US Dollars

Supp Figure S4

Figure S4. Real prices of selected food items, China, 1991–2004

Supp Table S1

Acknowledgments

This research was primarily funded by the Rockefeller Foundation. R Marten is thanked for his assistance in initiating and reviewing this document. We also wish to thank Ms. Frances L. Dancy for administrative assistance, Mr. Tom Swasey for graphics support, and Dr. Phil Bardsley for programming assistance. Carlos Monteiro, Juan Rivera, Ricardo Uauy and Srinath Reddy provided advice with selected components and are thanked. Additional support has come from NIH (R01-HD30880, DK056350, R24 HD050924 and R01-HD38700).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None of the authors has conflict of interests of any type with respect to this manuscript.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00456.x

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://academic.oup.com/nutritionreviews/article-pdf/70/1/3/24094379/nutritionreviews70-0003.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00456.x

Article citations

Teachers' perception of their students' dietary habits in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a qualitative study.

BMC Nutr, 10(1):141, 22 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39434168 | PMCID: PMC11494765

Abdominal obesity in youth: the associations of plasma Lysophophatidylcholine concentrations with insulin resistance.

Pediatr Res, 19 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39427100

Explaining socioeconomic inequality in food consumption patterns among households with women of childbearing age in South Africa.

PLOS Glob Public Health, 4(10):e0003859, 21 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39432471 | PMCID: PMC11493276

Association Between Dietary Habits and the Semen Quality of South Asian Men Attending Fertility Clinic: A Cross-sectional Study.

Reprod Sci, 31(11):3368-3378, 04 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39365422

Exploring the trend of age-standardized mortality rates from cardiovascular disease in Malaysia: a joinpoint analysis (2010-2021).

BMC Public Health, 24(1):2519, 16 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39285391 | PMCID: PMC11403801

Go to all (1,713) article citations

Other citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Processed foods and the nutrition transition: evidence from Asia.

Obes Rev, 15(7):564-577, 15 Apr 2014

Cited by: 118 articles | PMID: 24735161

Review

The nutrition transition and obesity in the developing world.

J Nutr, 131(3):871S-873S, 01 Mar 2001

Cited by: 468 articles | PMID: 11238777

Review

Where is Nepal in the nutrition transition?

Asia Pac J Clin Nutr, 26(2):358-367, 01 Mar 2017

Cited by: 31 articles | PMID: 28244717

An overview of the nutrition transition in West Africa: implications for non-communicable diseases.

Proc Nutr Soc, 74(4):466-477, 22 Dec 2014

Cited by: 53 articles | PMID: 25529539

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NICHD NIH HHS (6)

Grant ID: R01-HD30880

Grant ID: R01 HD030880

Grant ID: R01-HD38700

Grant ID: R24 HD050924

Grant ID: R01 HD030880-17

Grant ID: R01 HD038700

NIDDK NIH HHS (2)

Grant ID: DK056350

Grant ID: P30 DK056350