Abstract

Background

Child maltreatment is associated with heightened risk for depression; however, not all individuals who experience maltreatment develop depression. Previous research indicates that maltreatment contributes to an attention bias for emotional cues, and that depressed individuals show attention bias for sad cues.Method

The present study examined attention patterns for sad, depression-relevant cues in children with and without experience of maltreatment. We also explored whether individual differences in physiological reactivity and emotion regulation in response to a sad emotional state predict heightened attention to sad cues associated with depression.Results

Children who experienced high levels of maltreatment showed an increase in attention bias for sad faces throughout the course of the study, such that they showed biased attention for sad faces following the initiation of a sad emotional state. Maltreated children who had high levels of trait rumination showed an attention bias toward sad faces across all time points.Conclusions

These data suggest that maltreated children show heightened attention for depression-relevant cues in certain contexts (e.g. after experience of a sad emotional state). Additionally, maltreated children who tend to engage in rumination show a relatively stable pattern of heightened attention for depression-relevant cues. These patterns may identify which maltreated children are most likely to exhibit biased attention for sad cues and be at heightened risk for depression.Free full text

Emotion Regulation Predicts Attention Bias in Maltreated Children at Risk for Depression

Abstract

Background

Child maltreatment is associated with heightened risk for depression; however, not all individuals who experience maltreatment develop depression. Previous research indicates that maltreatment contributes to an attention bias for emotional cues, and that depressed individuals show attention bias for sad cues.

Method

The present study examined attention patterns for sad, depression-relevant cues in children with and without experience of maltreatment. We also explored whether individual differences in physiological reactivity and emotion regulation in response to a sad emotional state predict heightened attention to sad cues associated with depression.

Results

Children who experienced high levels of maltreatment showed an increase in attention bias for sad faces throughout the course of the study, such that they showed biased attention for sad faces following the initiation of a sad emotional state. Maltreated children who had high levels of trait rumination showed an attention bias toward sad faces across all time points.

Conclusions

These data suggest that maltreated children show heightened attention for depression-relevant cues in certain contexts (e.g., after experience of a sad emotional state). Additionally, maltreated children who tend to engage in rumination show a relatively stable pattern of heightened attention for depression-relevant cues. These patterns may identify which maltreated children are most likely to exhibit biased attention for sad cues and be at heightened risk for depression.

Child maltreatment is a prevalent problem in the United States and has been linked to myriad detrimental effects on long-term mental health (Widom, DuMont, & Czaja, 2007). Risk for depression is particularly high; however, not all individuals who experience maltreatment develop depression. Previous research has shown that maltreated children exhibit alterations in emotional reactivity and regulation, and that these behaviors are associated with altered attention to emotional information (Pollak, 2008). Similarly, children at-risk for depression and adults with depression show preferential attention to sad faces (e.g., Caseras, Garner, Bradley, & Mogg, 2007). Therefore, we examined maltreated children’s attention to sad cues after exposure to an elicitor of sad emotion. We hypothesized that children without a history of maltreatment would respond to a sad emotional state with minimal consequences on their attention to emotion-congruent information. In contrast, we predicted that children with an early experience of maltreatment would show increased reactivity to the experience of a sad emotional state, leading to the heightened attention to sad cues that is typically associated with depression.

Child Maltreatment and Emotional Reactivity

The experience of maltreatment is known to disrupt many processes involved in normative emotional development. For example, youth who have experienced maltreatment show altered neuroendocrine activation (Heim et al., 2000; Lipschitz, Morgan, & Southwick, 2002; Tarullo & Gunnar, 2006) and sympathetic arousal (Gordis, Granger, Susman, & Trickett, 2008) in response to psychological stress. These effects are proposed to be physiological indices of emotional reactivity. Physiological reactivity to emotional states may further contribute to alterations in processing emotional information, such as biased attention to emotional cues (Lupien, Gillin, Frakes, Soefje, & Hauger, 1995). For example, individuals with high cortisol responses to stress show biased attention to images of threatening faces compared to neutral faces following a stressor (Roelofs, Bakvis, Hermans, van Pelt, & van Honk, 2007). Indeed, maltreatment experience is also associated with atypical patterns of attentional control to anger cues in children (Pine et al., 2005; Pollak, Vardi, Putzer, & Curtin, 2005; Shackman, Shackman, & Pollak, 2007) and adults (Gibb, Schofield, & Coles, 2009).

Less is currently understood about the relationships between emotional reactivity to sad emotional states and attention to emotion-congruent cues in maltreated individuals. The processing of information congruent with sad emotions is particularly relevant, as there is considerable evidence that children at-risk for depression (Gibb, Benas, Grassia, & McGeary, 2009; Joormann, Talbot, & Gotlib, 2007) and individuals with depression or depressive symptoms (Caseras, et al., 2007; Eizenman et al, 2003; Gotlib et al., 2004) show biased attention to sad cues. Additionally, many maltreated individuals develop major depressive disorder or depressive symptoms that indicate dysegulation of sad emotion (Ethier, Lemelin, & Lacharite, 2004; Harkness, Bruce, & Lumley, 2006; Widom, DuMont, & Czaja, 2007). It is also important to examine individual differences within populations of children who have experienced maltreatment.

There may be individual differences in physiological indicators of emotional reactivity (such as sympathetic arousal) that predict attention biases to sad, emotion-congruent cues. Indeed, previous research indicates there are individual differences in systolic blood pressure reactivity in response to stress, which are associated with differences in neural activity and a range of behavioral and health outcomes (Gianaros et al., 2008).

Individual differences in how children learn to think about their emotions may predict difficulties with attentional control for sad cues over a longer period of time. One such thought pattern is rumination, or repetitive thinking about the causes and consequences of negative events and emotions. The tendency to engage in this maladaptive and ineffective emotion regulation strategy for sadness is common among depressed youth (Rood, Roelofs, Bogels, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Shouten, 2009) and is associated with concurrent and prospective depressive symptoms (Ziegert & Kistner, 2002; Abela, Brozina, & Haigh, 2002; Hilt, McLaughlin, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2010; Roelofs et al., 2009). Maltreated individuals who show heightened reactivity to experiencing a sad emotion and then engage in rumination may continue to show altered patterns of attention for sad cues well beyond the initiation of a sad emotion, when most individuals have recovered.

The Current Study

In the present study, we examined the impact of two individual differences related to emotion reactivity and regulation on attention patterns commonly observed in depression: Blood pressure reactivity to experience of a sad emotional state and trait rumination. We sought to determine the associations between these variables and attention biases to sad emotional stimuli in children who have and have not experienced maltreatment. We predicted that maltreated children who have heightened physiological reactivity when experiencing a sad emotion would show heightened attention to sad cues compared to non-maltreated children. Because timing of the onset and offset of emotions may be a key factor in mental health, we also examined the chronometry of these effects. We predicted that those maltreated children who have heightened reactivity and also engage in ruminative thinking would continue to show heightened attention to sad cues for a longer period of time than their peers. This finding would link a risk feature in maltreated children to a marker observed in adults with depressive disorders.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 61 children (31 males, 30 females) ages 11-14 (M = 12.08, SD = 0.88). This age range was selected because prevalence rates of major depressive disorder substantially increase between ages 13-15 (Hankin et al., 1998). Participants were Caucasian/non-Hispanic (67%, n = 41), African-American (28%, n = 17), and Hispanic (5%, n = 3). Families were recruited through newspaper ads, bus ads, and flyers in the community. Families with substantiated cases of child maltreatment were recruited through letters forwarded by the Dane County (WI) Department of Human Services. Written assent and consent was obtained for all participants and parents. Study procedures were approved by the Social and Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Board at the University of Wisconsin – Madison.

Maltreatment Assessment

Parents completed the Conflict Tactics Scale for Parent-Child (CTSPC; Straus et al., 1998) to assess emotionally abusive, physically abusive, and neglectful behaviors. The CTSPC is a valid measure of maltreatment and is associated with court substantiated cases of maltreatment (see Straus & Hamby, 1997 for review). The frequency of physically abusive behaviors in the past year (from 13 items on the CTSPC; Straus et al., 1998) was used as a measure of maltreatment in the current study (α = .74; n = 61, M = 5.46, SD = 10.04). Participant age and race/ethnicity were not associated with differences in maltreatment experience. Males experienced higher levels of physical abuse than females, F(1, 60) = 4.15, p = .05.1

Assessment of Psychopathology

Master’s level trained interviewers administered the Computerized Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (C-DISC; Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000) to participants. This interview was included because individuals with depression and depressive symptoms show preferential attention to sad cues (Caseras et al., 2007; Eizenman et al, 2003; Gotlib et al., 2004); therefore, it is important to rule out the possibility that observed differences are due to depression. The interview assessed current and past year diagnoses of anxiety disorders, mood disorders, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), and conduct disorder. Ten children did not complete the C-DISC; these children did not differ from the remaining sample in distribution of sex or race/ethnicity.

No children in the current study met full criteria for diagnosis of a major depressive episode in the past year. Only five children met full criteria for any diagnosis, and four of these children also met criteria for a co-morbid diagnosis. Three children were diagnosed with specific phobia, two children were diagnosed with ADHD, and one child each was diagnosed with social phobia, separation anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and ODD. Symptom prevalence in the past year was low (M < 5 for all diagnoses).

A different group of Master’s level trained interviewers administered the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia – Lifetime (SADS-L; Endicott & Spitzer, 1978) to the parent. This interview was included because caregiver depression has been associated with alterations in emotional attention (Gibb et al., 2009a; Joormann et al., 2007); therefore, it is important to rule out the possibility that observed differences are due to caregiver diagnoses. The interview assessed current and lifetime diagnoses of mood disorders, anxiety disorders, drug and alcohol disorders, eating disorders, and somatization disorder. Caregivers of ten children did not complete the SADS-L; children with and without caregiver interviews did not differ in distribution of sex or race/ethnicity.

Twenty parents met full criteria for a diagnosis of a current or lifetime major depressive episode, five parents were diagnosed with current or lifetime post-traumatic stress disorder, and five parents were diagnosed with current or lifetime alcohol or other drug abuse disorders. No parents met criteria for any other disorder.

Interviewers were trained in procedures by thorough review of diagnostic criteria, observing and coding interviews, and administering and coding interviews until inter-rater reliability for individual diagnoses was greater than κ > .70. Interviewers met regularly to discuss cases to prevent interviewer drift.

Measures

Prior to the lab session, participants completed the Children’s Response Styles Scale (CRSS; Ziegert & Kistner, 2002) to assess trait rumination (α = .84, n = 57, M = 6.03, SD = 1.81) and the Child Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1985) to assess current depressive symptoms (α = .91; n = 61, M = 5.54, SD = 6.63) at home. Female participants (M = 6.58, SD = 1.84) had significantly higher trait rumination scores than male participants (M = 5.49, SD = 1.65), F (1, 60) = 6.03, p = .02. This sex difference and mean level of trait rumination are consistent with previous research (Ziegert & Kistner, 2002). Children’s depressive symptoms and trait rumination scores did not differ based on age or race/ethnicity.

Participants completed the Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM; Bradley & Lang, 1994) before and after mood inductions to assess current affect. Participants’ ratings on the affective valence scale (pictorial representation of five pictures from smiling to frowning) were translated into a numerical scale from 1 (positive affect) to 5 (negative affect).

Procedure

After completing the CRSS and CDI, participants and a parent came to lab. Participants were outfitted with the blood pressure monitor and completed the first dot probe task. Participants then completed the SAM, the sad mood induction, the SAM, and the second dot probe task. Participants had an 8-minute delay period alone in the experimental room (to allow time for individual differences in emotion regulation to emerge), and again completed the dot probe task. After the task, participants completed a happy mood induction and the SAM. Participants then completed the C-DISC. Finally, participants were fully debriefed by the experimenter. Parents completed the SADS-L during the experiment.

Blood Pressure Monitoring

Systolic blood pressure was monitored using the SpaceLabs 20917 Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitor. Readings were taken at nine points throughout the experimental session. Because of particular interest in systolic blood pressure reactivity (SBPR) to experience of a sad emotion, a change score was calculated for SBP immediately after the sad mood induction minus baseline (measured after participants had acclimated to the lab setting). Participants’ mean baseline SBP was in the normal range (M = 116.77, SD = 11.71). Participants’ SBP did not change on average from baseline to after the sad mood induction, t(59) = −1.70, p = .09. The majority of participants (56.7%) showed a decrease in blood pressure in response to the sad mood induction.

Dot Probe Task

Face stimuli on the dot probe task were selected from the MacArthur Network Face Stimuli Set (http://www.macbrain.org/resources.htm; Tottenham, Borscheid, Ellertsen, Marcus, & Nelson, 2002; Tottenham et al., 2009). This stimuli set consists of color photographs of 646 different facial-expression stimuli displayed by a variety of models of each sex and varying ethnicities. From this set, we selected 19 models with equal representations of sex and ethnicity that each had a neutral, happy, sad, and angry expression. Models were selected based on reliability scores across emotion types (Tottenham et al., 2009).

Each trial began with a fixation cross for 1000ms, followed by presentation of a pair of faces (emotion and neutral) for 1500ms. Face presentation duration of 1500ms was selected based on previous findings that depression-relevant attention biases occur only for longer stimulus durations (e.g., Joormann et al., 2007). After presentation of the face stimluli, a dot appeared in the center of the location where one of the faces had been. The dot remained on the screen until the participant pressed a key to indicate the location of the dot (left or right). Slower reaction times to probes appearing in the location of neutral stimuli compared to emotion stimuli indicate a bias in attention to emotion stimuli. Each pair of faces (happy, sad and angry faces paired with neutral faces) was presented two times per task, for a total of 114 trials. Both the emotion faces and the dot appeared in the right and left positions equally. Each presentation of the dot probe task (baseline, post-mood, and post-delay period) had identical stimuli, with order of presentation pseudorandomized to differ across tasks.

The size of each picture on the screen was approximately 13 cm × 16.5 cm. The pictures in each pair were approximately 20 cm apart (measured from their centers). The task was presented on an IBM-compatible computer and a ViewSonic 15-in. (20.3-cm) color monitor. E-Prime (Psychology Software Tools, 2002) software was used to control stimulus presentation and record response accuracy and reaction times.

Mood Manipulations

For the sad mood induction, participants were instructed to recall and write about a time in their lives when they felt purely sad for three minutes. During the writing period, the experimenter played a recording of sad music (Samuel Barber’s Adagio For Strings, 1936). The happy mood induction consisted of the same procedure with a happy memory and happy music (Antonio Vivaldi’s Concerto for 2 Mandolins & Strings in G Major, 1742), and was included to ensure participants returned to baseline mood before leaving the lab. Both musical selections have been previously validated as successful methods of manipulating sad and happy emotional states (Siemer, 2005).

Attention bias scoring

Only reactions times from correct responses were analyzed; percentage of dot probe trials with errors were low (< 1%). Trials with reaction times less than 100ms and greater than 1500ms were excluded from analyses as they likely reflect inattention to the task. Less of 1% of the data was excluded. Average reaction times for each emotion were computed for each dot probe task (baseline, post-mood induction, and after delay period). Attention bias to emotion faces (sad, happy, angry) compared to neutral faces was computed using standard procedures (Mogg, Bradley, & Williams, 1995). Positive values for attention bias scores indicate attention toward the emotion faces, while negative values indicate attention away from the emotion faces relative to neutral faces.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

One-way ANOVA analyses indicated that participant sex, age, race/ethnicity, and parent diagnoses were not associated with any attention bias measures. Linear regression analyses indicated no association between child symptoms of psychopathology from the C-DISC or child depressive symptoms from the CDI and any attention bias measures. Children with and without C-DISC and caregiver SADS-L interviews did not differ in trait rumination, depressive symptoms on the CDI, or any attention bias measure. CDI score was included as a covariate in all analyses.

Mood manipulation check

As expected, a repeated-measure ANOVA indicated that children’s levels of negative affect changed throughout the study, F(2, 116) = 24.05, p < .001, partial eta-squared = .29. Children reported greater negative affect following the sad mood induction (M = 2.40, SD = 0.94) compared to baseline (M = 1.89, SD = 0.76). Children also showed affective recovery with the happy mood induction (M = 1.59, SD = 0.79).

Attention patterns for emotion faces

We conducted a repeated measures GLM with time (baseline, post-mood induction, and post-delay period), emotion cue (sad, angry, and happy), maltreatment (CTSPC physical abuse scale score), systolic blood pressure reactivity (SBPR), trait rumination (CRSS score), and all interactions as predictors of attention on the dot probe task. 2 All predictor variables were Z-scored.

We predicted that maltreated children with high physiological reactivity to experience of a sad emotional state would show heightened attention for sad faces immediately after the sad mood induction. Additionally, we predicted that those reactive maltreated children who also tend to ruminate would continue to show heightened attention for sad faces over time. Contrary to predictions, there was no five-way interaction among time point, emotion cue, maltreatment, SBPR, and trait rumination on attention patterns (see Table 1 for results from the omnibus model).

Table 1

Results of repeated measures GLM with time, emotion cue, maltreatment (PA), systolic blood pressure reactivity (SBPR), trait rumination (RUM), and all interactions as predictors of attention. Interactions involving time × emotion not included (all n.s. at p > .05).

| F | Partial eta-squared | |

|---|---|---|

| Time | 1.01 | .019 |

| Time × PA | 0.14 | .003 |

| Time × RUM | 1.32 | .025 |

| Time × SBPR | 0.08 | .001 |

| Time × PA × RUM | 4.40 | .079* |

| Time × PA × SBPR | 0.45 | .009 |

| Time × RUM × SBPR | 2.47 | .046 |

| Time × PA × RUM × SBPR | 1.91 | .036 |

| Emotion | 1.82 | .034 |

| Emotion × PA | 6.27 | .109* |

| Emotion × RUM | 3.09 | .057* |

| Emotion × SBPR | 3.25 | .060* |

| Emotion × PA × RUM | 4.27 | .077* |

| Emotion × PA × SBPR | 7.84 | .133* |

| Emotion × RUM × SBPR | 3.62 | .066* |

| Emotion × PA × RUM × SBPR | 2.81 | .052* |

| PA | 1.76 | .033 |

| RUM | 2.43 | .045 |

| SBPR | 0.00 | .000 |

| PA × RUM | 0.11 | .002 |

| PA × SBPR | 0.01 | .000 |

| RUM × SBPR | 0.25 | .005 |

| PA × RUM × SBPR | 0.00 | .000 |

Changes in attention to emotion faces

Only the interaction between maltreatment and trait rumination on attention for all emotion faces changed across time points, F(2, 102) = 4.40, p = .02, partial eta-squared = .08. We further explored this interaction by examining the relationship between maltreatment and rumination at each time point. Children on average did not show biased attention toward or away from emotion faces at any time point. However, there was a significant interaction between maltreatment and trait rumination on attention for emotion faces after the delay period, B = 9.88, p = .04, partial eta-squared = .08.

To further investigate this interaction, we used the simple slopes technique (Aiken and West, 1991). We examined the simple slope at one SD above the mean maltreatment score and when number of physically abusive experiences was zero. Children who experienced higher levels of maltreatment and who had higher levels of trait rumination showed a greater attention bias toward emotion faces overall after the delay period, B = 19.01, p = .007, partial eta-squared = .14. In contrast, children who experienced no maltreatment did not differ in attention for emotion faces as a function of trait rumination, B = 3.75, p = .24.

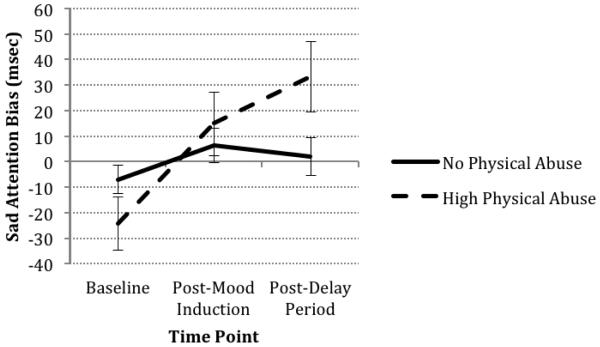

Changes in attention to sad faces

Although the omnibus analyses indicated changes in attention over time did not vary based on emotion cue type, we had particular interest in the chronometry of attention patterns for sad cues and repeated analyses on attention for sad faces alone. The relationship between maltreatment and attention for sad faces changed across time, F(2, 102) = 5.33, p = .006, partial eta-squared = .10, see Figure 1. We further explored this interaction by examining the influence of maltreatment on attention for sad faces at each time point. Children on average did not show an attention bias toward sad faces at any time point. However, after the delay period, children who had experienced more maltreatment showed more attention toward sad faces, B = 20.36, p = .012, partial eta-squared = .12. In sum, maltreated children showed heightened attention to sad faces after the delay period, and those maltreated children who ruminate showed generalized heightened attention to emotion faces after the delay period.

Attention patterns for sad faces at baseline, immediately after induction of a sad affective state, and after a delay period. Positive attention bias scores indicate attention toward sad faces. No and high physical abuse represent points at zero physical abuse and one SD above the mean physical abuse score, respectively.

Stable attention patterns

Across time points, children on average did not show a bias toward or away from any emotion cue. However, there was a trend for a significant four-way interaction among emotion cue, maltreatment, SBPR, and trait rumination, F(2, 102) = 2.81, p = .07, partial eta-squared = .05. To further explore this interaction, we examined the relationships among maltreatment, SBPR, and trait rumination for each emotion cue separately.

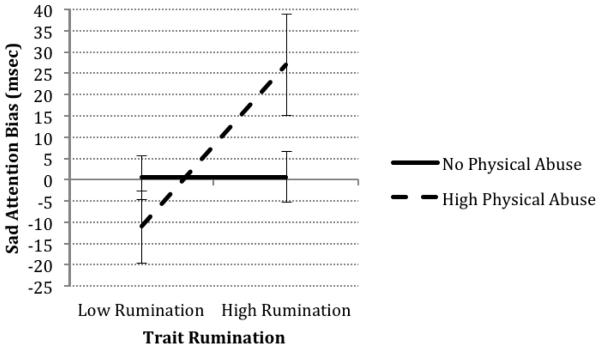

Attention patterns for sad faces were of particular interest in the present study. Across time points, there was a significant interaction between maltreatment experience and trait rumination on attention patterns for sad faces, F(1, 51) = 5.81, p = .02, partial eta-squared = .10, see Figure 2. Children who had experienced high levels of maltreatment (1 SD above the mean) showed a greater attention bias toward sad faces if they had higher levels of trait rumination, B = 19.03, p = .013, partial eta-squared = .11. In contrast, children who had no maltreatment experience did not differ in attention for sad faces as a function of trait rumination, B = 0.72, p = 0.98.

Interaction of maltreatment and trait rumination on attention bias to sad faces across all dot probe tasks. Positive attention bias scores indicate attention toward sad faces. No and high physical abuse represent points at zero physical abuse and one SD above the mean physical abuse score, respectively. Low and high trait rumination represent points one SD below and above the mean, respectively.

For happy faces, like sad faces, there was a significant maltreatment by trait rumination interaction across all time points, B = −10.48, p = .03, partial eta-squred = .09. For children with higher levels of maltreatment (1 SD above the mean), there was a trend for those with higher levels of trait rumination to avoid happy faces overall, B = −12.40, p = .08, partial eta-squared = .06. In contrast, children with no maltreatment experience did not differ in attention for happy faces as a function of trait rumination, B = 3.78, p = .25. In sum, maltreated children who ruminate show more attention for sad faces and tend to show less attention for happy faces across time points. For anger faces, attention patterns did not differ as a function of maltreatment, SBPR, trait rumination, or their interaction.

Discussion and Conclusion

The current study was designed to test whether the experience of child maltreatment contributes to the preferential attention to sad cues that is associated with risk for depression. Specifically, we examined if individual differences in emotion reactivity to and regulation of a sad emotional state predicted which maltreated children exhibited depression-relevant attention biases to sad cues. We did so immediately after experience of a sad emotion and after a delay period when emotional state should have returned to baseline.

Children with histories of maltreatment showed preferential attention to sad, emotion-congruent cues only after they experienced a sad emotional state. Those maltreated children who engage in rumination showed a generalization of this effect, such that they showed preferential attention for all emotion cues after they experienced a sad emotional state. Additionally, maltreated children who engage in rumination showed a more stable pattern of heightened attention to sad cues across time points and a trend toward avoidance of happy cues across time points. Attention to sad cues did not vary as a function of emotional state for these children. This pattern cannot be attributed to negative affect or depression: Current negative affect and depressive symptoms in the past year did not influence attention biases and effects remained when controlling for current depressive symptoms.

The results of the current study expand on previous research indicating that maltreated children show heightened attention for anger cues to suggest that maltreated children also show heightened attention for sad, depression-relevant cues in certain contexts. Specifically, children who experienced higher levels of maltreatment did not immediately respond to a sad emotional state by showing a sad attention bias, but showed heightened attention for sad cues after a brief delay period. This finding is consistent with the idea that early experience may predispose individuals to depression when they experience a stressor. Additionally, the current results suggest that maltreated children who ruminate show a more stable pattern of heightened attention for sad cues.

These attention patterns could serve as a risk mechanism. Those maltreated children who have difficulty regulating emotional states pay more attention to sad cues and may also pay less attention to happy cues. These children may engage in even more rumination about their current social environment in response to these social cues, which may exacerbate sad moods when they occur. This could lead to a perpetual loop of maladaptive coping that exacerbates and prolongs sad moods.

Analyses of attention for anger cues did not replicate previous findings of an association between maltreatment and heightened attention for anger cues (e.g., Pine et al., 2005; Pollak, et al., 2005; Shackman, et al., 2007). However, much of the previous research has used either physiological indices of attention (such as skin conductance or ERP) or measures of visual attention at a shorter stimulus presentation than in the current study (500ms as compared to 1500ms). Attention patterns at 1500ms stimulus presentation likely reflect top-down control processes rather than vigilance. It may be that children with higher levels of maltreatment were vigilant to anger cues, but that they did not dwell on these cues and this pattern was not captured with the present methods.

The precise influence of trait rumination on attention biases to sad cues in this experiment is unclear. Although trait rumination predicted attention patterns, it is not possible to determine if trait ruminators actually engaged in rumination during the study. Future research would benefit from including state-level measures of rumination and manipulating rumination in studies of attention biases.

We did not observe the previously demonstrated relationship between children’s depressive symptoms and sad attention bias (e.g., Hankin, Gibb, Abela, & Flory, 2010). However, no children in the current study met criteria for a major depressive episode in the past year and depressive symptoms were low. Although children’s symptoms of depression in the past year were not related to attention patterns, we are unable to rule out the possibility that children in the current study had experienced a depressive episode prior to the past year. Therefore, it is not possible to determine if the results of the current study represent putative risk mechanisms that occur prior to development of depression. Replication of the current results in a sample of children who have never experienced a depressive episode is needed.

We assessed maltreatment using parent self-report, which is likely to elicit social desirability pressure to under-report abusive behaviors. However, the self-report measure used in the current study has been shown to be a valid measure of maltreatment and is associated with court-substantiated cases of maltreatment. Additionally, social desirability influences work against our hypotheses, and any abusive behaviors that parents report on this measure are likely to be an underestimate. Although children in the current study experienced a range of physical abuse, more children had lower exposure to abuse and results were influenced by a relatively small number of individuals with high levels of physical abuse. Replication of the current results with larger sample sizes of children with high levels of maltreatment exposure is needed.

Despite extensive evidence that maltreated children are at heightened risk for depression, there has been minimal empirical exploration of which individuals who experience maltreatment go on to develop depression. The present data suggest that maltreated children show patterns of heightened attention to sad cues that emerge a brief time after induction of a sad emotional state. Additionally, maltreated children with difficulties with regulation of sad affect, as indexed by ruminative approaches to regulation, show a more stable pattern of preferential attention to sad cues. These patterns of attention have been previously observed in individuals at-risk for and with diagnoses of depression, and may reflect a mechanism linking maltreatment with development of depression for some individuals.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant to Seth Pollak from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH61285) and a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award to Sarah Romens from the National Institute of Mental Health (F31MH088111). We thank Jutta Joormann, Ph.D. for providing the template for the dot probe task used the current study. We thank Mary Schlaak, Alicia Hoffman, and Allison Lundahl for their help with data collection.

Footnotes

1All results of the current study are replicated when including sex as a covariate in analyses.

2This omnibus analysis was repeated with the emotional abuse subscale of the CTSPC. Results indicated that children with high levels of emotional abuse attended more to anger cues overall across time points, B = 8.67, p = .05, partial eta-squared = .09.

Contributor Information

Sarah E. Romens, Sarah Romens, Department of Psychology, University of Wisconsin – Madison, Waisman Center 1500 Highland Avenue, Room 399, Madison, WI 53705; ude.csiw@mherbes..

Seth D. Pollak, Seth Pollak, Department of Psychology, University of Wisconsin – Madison, Waisman Center, 1500 Highland Avenue, Room 399, Madison, WI 53705; ude.csiw@kallops..

References

- Abela JRZ, Brozina K, Haigh EP. An examination of the response styles theory of depression in third- and seventh-grade children: A short-term longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:515–527. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM, Lang PJ. Measuring emotion: The self-assessment manikin and semantic differential. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1994;25:49–59. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Caseras X, Garner M, Bradley BP, Mogg K. Biases in visual orienting to negative and positive scenes in dysphoria: An eye movement study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116(3):491–497. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Eizenman M, Yu LH, Grupp L, Eizenman E, Ellenbogen M, Gemar M, et al. A naturalistic visual scanning approach to assess selective attention in major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Research. 2003;118(2):117–128. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Spitzer RL. Use of the Research Diagnostic Criteria and the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia to study affective disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1979;136:52–56. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Éthier LS, Lemelin J, Lacharité C. A longitudinal study of the effects of chronic maltreatment on children’s behavioral and emotional problems. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28(12):1265–1278. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Gianaros PJ, Sheu LK, Matthews KA, Jennings JR, Manuck SB, et al. Individual differences in stressor-evoked blood pressure reactivity vary with activation, volume, and functional connectivity of the amygdala. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28:990–999. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Benas JS, Grassia M, McGeary J. Children’s attentional biases and 5-HTTLPR genotype: Potential mechanisms linking mother and child depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2009a;38:415–426. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Schofield CA, Coles ME. Reported history of childhood abuse and young adults’ information-processing biases for facial displays of emotion. Child Maltreatment. 2009b;14:148–156. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Gordis EB, Granger DA, Susman EJ, Trickett PK. Salivary alpha amylase-cortisol asymmetry in maltreated youth. Hormones and Behavior. 2008;53(1):96–103. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Krasnoperova E, Yue DN, Joormann J. Attentional biases for negative interpersonal stimuli in clinical depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113(1):121–135. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, et al. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:128–140. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Gibb BE, Abela JRZ, Flory K. Selective attention to affective stimuli and clinical depression among youths: Role of anxiety and specificity of emotion. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:491–501. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness KL, Bruce AE, Lumley MN. The role of childhood abuse and neglect in the sensitization to stressful life events in adolescent depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115(4):730–741. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Newport DJ, Heit S, Graham YP, Wilcox M, et al. Pituitary-adrenal and autonomic responses to stress in women after sexual and physical abuse in childhood. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284(5):592–597. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Hilt LM, McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Examination of the response styles theory in a community sample of young adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38:545–556. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Joormann J, Talbot L, Gotlib IH. Biased processing of emotional information in girls at risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116(1):135–143. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1985;21:995–998. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lipschitz DS, Morgan CA, III, Southwick SM. Neurobiological disturbances in youth with childhood trauma and in youth with conduct disorder. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2002;6(1):149–174. [Google Scholar]

- Lupien S, Gillin C, Frakes D, Soefje S, Hauger RL. Delayed but not immediate effects of a 100 minutes hydrocortisone infusion on declarative memory performance in young normal adults. International Society of Psychoneuroendocrinology Abstract. 1995:25. [Google Scholar]

- Pine DS, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Montgomery L, Monk CS, et al. Attention bias to threat in maltreated children: Implications for vulnerability to stress-related psychopathology. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162(2):291–296. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak SD. Mechanisms linking early experience and the emergence of emotions. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2008;17:370–375. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak SD, Vardi S, Putzer Bechner AM, Curtin JJ. Physically abused children’s regulation of attention in response to hostility. Child Development. 2005;76(5):968–977. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Roelofs K, Bakvis P, Hermans EJ, van Pelt J, van Honk J. The effects of social stress and cortisol responses on the preconscious selective attention to social threat. Biological Psychology. 2007;75(1):1–7. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Roelofs J, Rood L, Meesters C, te Dorsthorst V, Bögels S, et al. The influence of rumination and distraction on depressed and anxious mood: A prospective examination of the response styles theory in children and adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;18:635–642. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Rood L, Roelofs J, Bögels SM, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schouten E. The influence of emotion-focused rumination and distraction on depressive symptoms in non-clinical youth: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:607–616. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Shackman JE, Shackman AJ, Pollak SD. Physical abuse amplifies attention to threat and increases anxiety in children. Emotion (Washington, D.C.) 2007;7(4):838–852. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH C-DISC): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Siemer M. Mood-congruent cognitions constitute mood experience. Emotion. 2005;5:296–308. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL. Measuring physical and psychological maltreatment of children with the Conflict Tactics Scales; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association; Chicago, IL. 1997, March. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Finkelhor D, Moore DW, Runyan D. Identification of child maltreatment with the parent-child conflict tactics scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1998;22:249–270. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Tarullo AR, Gunnar MR. Child maltreatment and the developing HPA axis. Hormones and Behavior. 2006;50(4):632–639. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Tottenham N, Borscheid A, Ellersten K, Markus DJ, Nelson CA. Categorization of facial expressions in children and adults: Establishing a larger stimulus set; Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Cognitive Neuroscience Society; San Francisco, CA. 2002, April. [Google Scholar]

- Tottenham N, Tanaka J, Leon A, McCarry T, Nurse M, et al. The NimStim set of facial expressions: Judgments from untrained research participants. Psychiatry Research. 2009;168:242–249. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, DuMont K, Czaja SJ. A prospective investigation of major depressive disorder and comorbidity in abused and neglected children grown up. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(1):49–56. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegert DI, Kistner JA. Response styles theory: A downward extension to children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31:325–334. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02474.x

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc3258383?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02474.x

Article citations

Attentional processes in response to emotional facial expressions in adults with retrospectively reported peer victimization of varying severity: Results from an ERP dot-probe study.

BMC Psychol, 12(1):459, 29 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39210484 | PMCID: PMC11361057

A systematic review of childhood maltreatment and resting state functional connectivity.

Dev Cogn Neurosci, 64:101322, 10 Nov 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 37952287 | PMCID: PMC10665826

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

An Integrative Model of Youth Anxiety: Cognitive-Affective Processes and Parenting in Developmental Context.

Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev, 26(4):1025-1051, 11 Oct 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 37819403

Academic Performance in Institutionalized and Noninstitutionalized Children: The Role of Cognitive Ability and Negative Lability.

Children (Basel), 10(8):1405, 17 Aug 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37628405 | PMCID: PMC10453080

The Relationship Between Temperament Characteristics and Emotion Regulation Abilities in Institutionalized and Noninstitutionalized Children.

Psychol Stud (Mysore), 1-13, 16 May 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 37361514 | PMCID: PMC10185962

Go to all (48) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Childhood maltreatment is associated with an automatic negative emotion processing bias in the amygdala.

Hum Brain Mapp, 34(11):2899-2909, 13 Jun 2012

Cited by: 136 articles | PMID: 22696400 | PMCID: PMC6870128

Recognition of facial emotions among maltreated children with high rates of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Child Abuse Negl, 32(1):139-153, 21 Dec 2007

Cited by: 71 articles | PMID: 18155144 | PMCID: PMC2268025

Abnormal emotional processing in maltreated children diagnosed of Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder.

Child Abuse Negl, 73:42-50, 22 Sep 2017

Cited by: 11 articles | PMID: 28945995

Emotion Reactivity and Regulation in Maltreated Children: A Meta-Analysis.

Child Dev, 90(5):1503-1524, 07 Jul 2019

Cited by: 39 articles | PMID: 31281975

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NICHD NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: P30 HD003352

NIMH NIH HHS (5)

Grant ID: MH61285

Grant ID: R01 MH061285

Grant ID: F31 MH088111

Grant ID: F31MH088111

Grant ID: F31 MH088111-02