Abstract

Free full text

Monocyte tissue factor–dependent activation of coagulation in hypercholesterolemic mice and monkeys is inhibited by simvastatin

Abstract

Hypercholesterolemia is a major risk factor for atherosclerosis. It also is associated with platelet hyperactivity, which increases morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular disease. However, the mechanisms by which hypercholesterolemia produces a procoagulant state remain undefined. Atherosclerosis is associated with accumulation of oxidized lipoproteins within atherosclerotic lesions. Small quantities of oxidized lipoproteins are also present in the circulation of patients with coronary artery disease. We therefore hypothesized that hypercholesterolemia leads to elevated levels of oxidized LDL (oxLDL) in plasma and that this induces expression of the procoagulant protein tissue factor (TF) in monocytes. In support of this hypothesis, we report here that oxLDL induced TF expression in human monocytic cells and monocytes. In addition, patients with familial hypercholesterolemia had elevated levels of plasma microparticle (MP) TF activity. Furthermore, a high-fat diet induced a time-dependent increase in plasma MP TF activity and activation of coagulation in both LDL receptor–deficient mice and African green monkeys. Genetic deficiency of TF in bone marrow cells reduced coagulation in hypercholesterolemic mice, consistent with a major role for monocyte-derived TF in the activation of coagulation. Similarly, a deficiency of either TLR4 or TLR6 reduced levels of MP TF activity. Simvastatin treatment of hypercholesterolemic mice and monkeys reduced oxLDL, monocyte TF expression, MP TF activity, activation of coagulation, and inflammation, without affecting total cholesterol levels. Our results suggest that the prothrombotic state associated with hypercholesterolemia is caused by oxLDL-mediated induction of TF expression in monocytes via engagement of a TLR4/TLR6 complex.

Introduction

Hypercholesterolemia describes the presence of increased lipids in blood that is caused either by a predisposed genetic condition, such as a mutation of the LDL receptor (LDLR), or by an underlying disorder, such as obesity. Hypercholesterolemia is a major risk factor for atherosclerosis (1). The “response-to-injury” hypothesis (2) of atherosclerosis proposes that endothelial dysfunction allows circulating LDL to infiltrate the arterial wall, where it is progressively oxidized to form minimally modified LDL (mmLDL) and immunogenic oxidized LDL (oxLDL) (3, 4). Indeed, autoantibodies against oxLDL can be detected in hyperlipidemic mice and humans (4, 5). Although the majority of oxidized lipoproteins are localized within atherosclerotic lesions, small quantities have been detected in the circulation of patients with coronary artery disease (6, 7).

mmLDL and oxLDL contain many oxidation products that form from both the oxidation and fragmentation of lipid and protein components (8). Monocytes recruited into the inflamed arterial wall internalize mmLDL via TLR4 and form lipid-laden foamy macrophages (9). OxLDL is recognized and internalized by macrophages via scavenger receptors (SRs), such as CD36 and SR-AI/II (10). A recent study found that oxLDL induction of chemokine expression in murine macrophages is mediated by a CD36/TLR4/TLR6 heterotrimeric receptor complex (11). Importantly, TLR4 expression on PBMCs and monocytes is increased in patients with advanced cardiovascular disease (12, 13), and circulating monocytes have been shown to accumulate mmLDL in a TLR4-dependent manner (9).

Hypercholesterolemia is associated with a prothrombotic state (14). Platelets are hyperactive in patients with hypercholesterolemia (14, 15). A recent study demonstrated that activation of platelets with a specific oxidized choline glycerophospholipid (oxPCCD36) is mediated by CD36 (16). Moreover, hypercholesterolemic mice exhibit a shortened time to occlusion in a carotid artery thrombosis model compared with healthy mice (16–19). At present, the mechanism underlying the systemic activation of coagulation associated with hypercholesterolemia has not been defined.

oxLDL and other bioactive lipids induce expression of the procoagulant protein tissue factor (TF) in monocytes/macrophages, endothelial cells, and smooth muscle cells (20–24). Consistent with these in vitro observations, high levels of TF are present in human and mouse atherosclerotic plaques (25–28). In addition, TF expression is increased in monocytes of patients with familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), who have high levels of plasma cholesterol due to mutations in the LDLR gene, and in monocytes of individuals with hypercholesterolemia (29–31). Furthermore, injection of oxidized lipids into mice increased TF expression in blood cells (32). Microparticles (MPs) are small plasma membrane vesicles released from activated and apoptotic cells that contain proteins from their cell of origin (33). Interestingly, acute coronary syndrome patients have elevated levels of monocyte-derived MPs and TF+ MPs (34, 35). Atherosclerotic plaques also contain high levels of monocyte-derived TF+ MPs (36), and cholesterol enrichment of human monocytic cells has been shown to induce the release of TF+ MPs (37). These data suggest that TF expression by circulating monocytes and the release of TF+ MPs may contribute to the systemic procoagulant state associated with hypercholesterolemia.

Statins are used to treat hypercholesterolemic patients and not only lower levels of plasma cholesterol, but also induce plaque regression (38). Statins also have antiinflammatory and antithrombotic activities (39, 40). Several studies have found that statin therapy is associated with a significant reduction in the incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) (41–43). Interestingly, statins also inhibit TF expression in monocytes and macrophages, both in vitro and in vivo (27, 29, 31, 39, 44–47).

In this study, we investigated the mechanism by which hypercholesterolemia leads to activation of coagulation in mice, monkeys, and humans and the effect of simvastatin administration.

Results

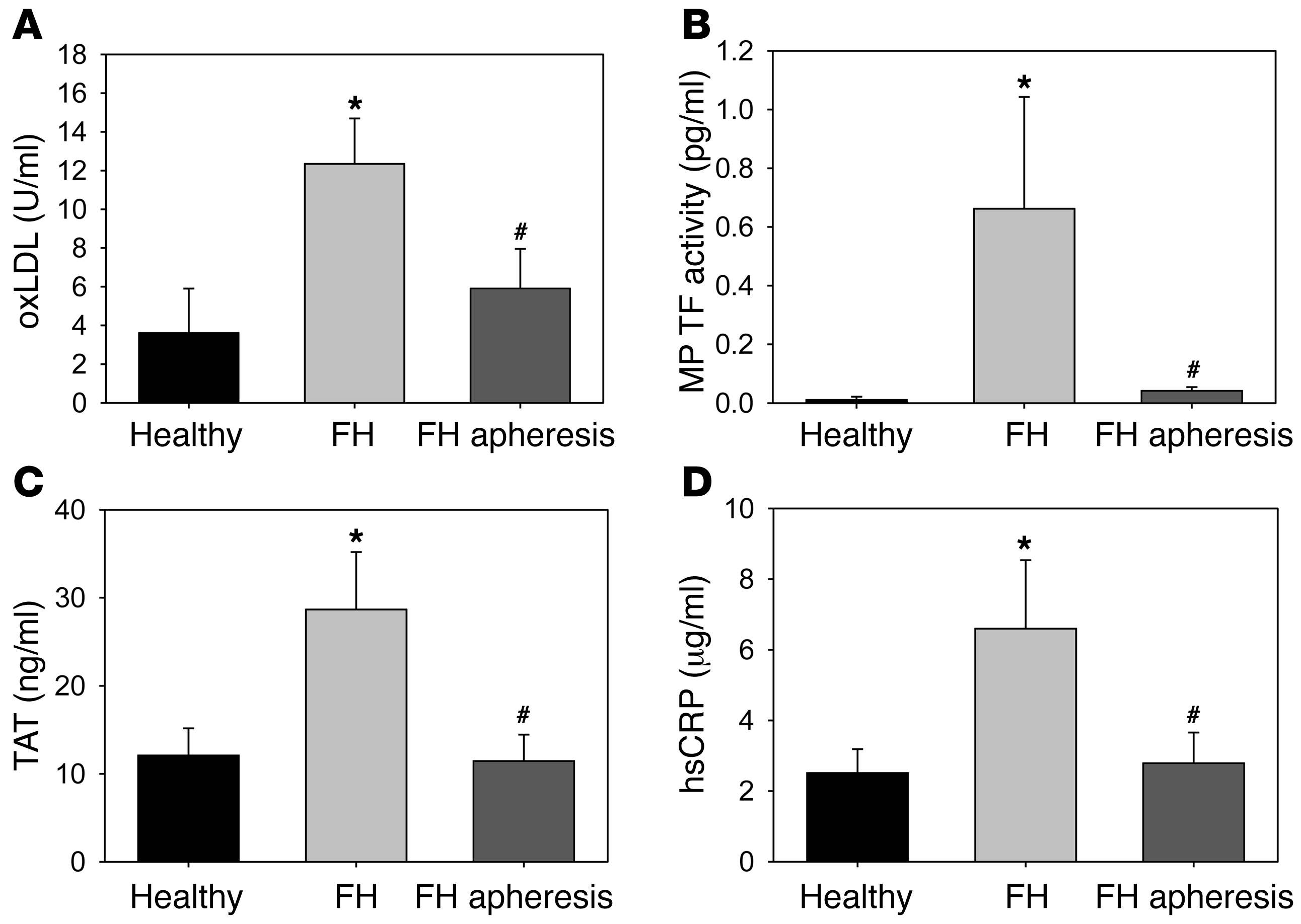

Levels of MP TF activity and activation of coagulation in FH patients before and after apheresis.

We examined levels of MP TF activity and activation of coagulation in FH patients (n = 25) and healthy matched controls (n = 17). FH patients had elevated levels of plasma lipids compared with healthy controls (except for HDL cholesterol [HDL-C]; Supplemental Table 1; supplemental material available online with this article; 10.1172/JCI58969DS1). FH patients also had elevated levels of oxLDL, MP TF activity, thrombin-antithrombin complex (TAT), which is a marker of activation of coagulation, and the inflammatory marker high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) compared with controls (Figure (Figure1,1, A–D). Apheresis reduced all parameters (Figure (Figure1,1, A–D).

Blood was obtained from matched healthy controls (n = 17) and FH patients (n = 25). Preapheresis is defined as blood drawn from the body that has not yet passed over the lipid-absorbing column. Postapheresis blood was collected after lipid absorbing, but prior to reentering the body. (A) oxLDL, (B) MP TF activity, (C) TAT, and (D) hsCRP. Histobars represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.025, FH patients versus healthy controls; #P < 0.01, FH patients before versus after apheresis. Data were analyzed with 1-way ANOVA on ranks with a Dunn’s post hoc.

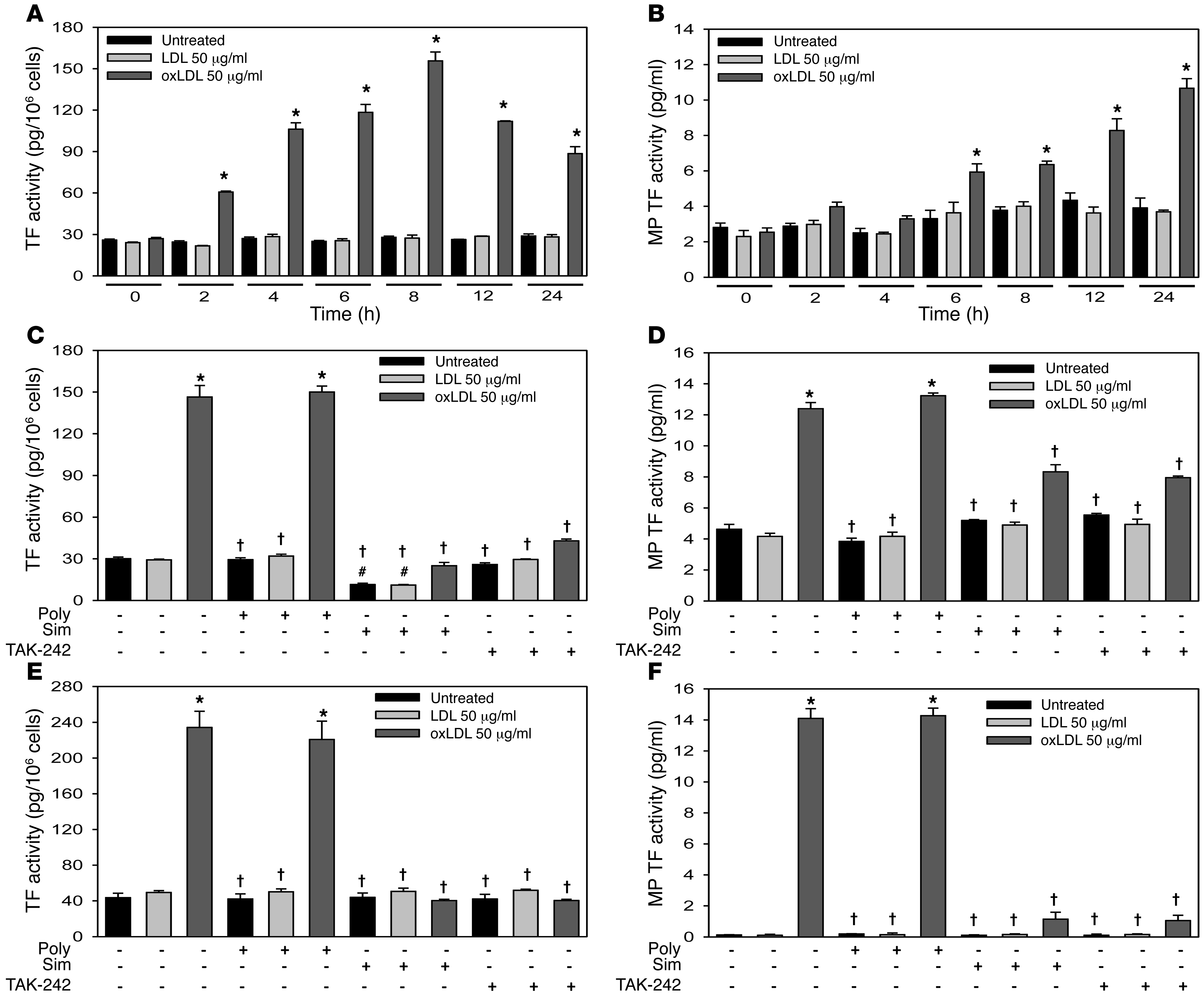

oxLDL induction of monocytic TF expression and release of TF+ MPs.

We determined the effect of LDL and oxLDL on TF expression in the human monocytic cell line THP-1 and human monocytes. OxLDL increased cellular TF activity in THP-1 cells at 24 hours in a concentration-dependent manner (0–50 μg/ml) without affecting cell viability (data not shown). Levels of oxLDL above 50 μg/ml decreased cell viability (data not shown). Therefore a dose of 50 μg/ml was chosen for all subsequent experiments. OxLDL, but not LDL, increased cellular TF activity in THP-1 cells in a time-dependent manner, with maximal levels observed at 8 hours (Figure (Figure2A).2A). Interestingly, this response was delayed compared with the induction of TF expression in cells treated with LPS (Supplemental Figure 1A). OxLDL treatment also induced a time-dependent release of TF+ MPs into the culture supernatant, with maximal levels observed at 24 hours (Figure (Figure2B).2B). LPS induced a more rapid release of TF+ MPs (Supplemental Figure 1B). OxLDL also induced TF expression in isolated human monocytes (Figure (Figure2E).2E). The LPS inhibitor polymyxin B had no effect on oxLDL induction of TF expression in THP-1 cells or monocytes, but abolished the LPS response (Figure (Figure2,2, C and E, and Supplemental Figure 1, C and E).

THP-1 cells were treated with LDL (50 μg/ml) or oxLDL (50 μg/ml) for different times, and (A) cellular TF activity and (B) MP TF activity in the culture supernatant were analyzed. THP-1 cells were treated for either 8 hours and analyzed for (C) cellular TF activity or 24 hours and analyzed for (D) MP TF activity in the culture supernatant after pretreatment with simvastatin (20 μM, sim) for 12 hours, the TLR4 inhibitor TAK-242 (1 μg/ml) for 2 hours, or the LPS-neutralizing antibiotic peptide polymyxin B (10 μg/ml) for 30 minutes. Human monocytes were also pretreated with the same agents; (E) cellular TF activity was analyzed after 8 hours, and (F) MP TF activity in the culture supernatant was analyzed after 24 hours. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. All experiments were performed 5 times in triplicate. *P < 0.01, oxLDL-treated versus untreated and LDL-treated cells; #P < 0.01, simvastatin-treated versus untreated cells; †P < 0.001, simvastatin-treated or TAK-242–treated versus cells without inhibitor. Data in A and B were analyzed with 1-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak post hoc, while data in C–F were analyzed via 2-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak post hoc.

Simvastatin and a TLR4 inhibitor attenuate oxLDL induction of monocytic TF expression.

To determine whether oxLDL induction of TF expression was dependent on TLR4, we pretreated THP-1 cells and monocytes with the TLR4 inhibitor CLI-095 (TAK-242). Inhibition of TLR4 ablated oxLDL and LPS induction of cellular TF activity and the release of TF+ MPs from THP-1 cells (Figure (Figure2,2, C and D, and Supplemental Figure 1, C and D) and monocytes (Figure (Figure2,2, E and F, and Supplemental Figure 1, E and F).

Statins have been shown to reduce LPS induction of TF expression in monocytes and macrophages. Therefore, we determined the effect of simvastatin on oxLDL induction of TF expression. Preincubation of THP-1 cells and monocytes with simvastatin decreased oxLDL induction of cellular TF activity and the release of TF+ MPs (Figure (Figure2,2, C–F). Simvastatin also decreased LPS induction of TF expression in the cells (Supplemental Figure 1, C–F) and the basal level of cellular TF activity in unstimulated THP-1 cells (Figure (Figure2C). 2C).

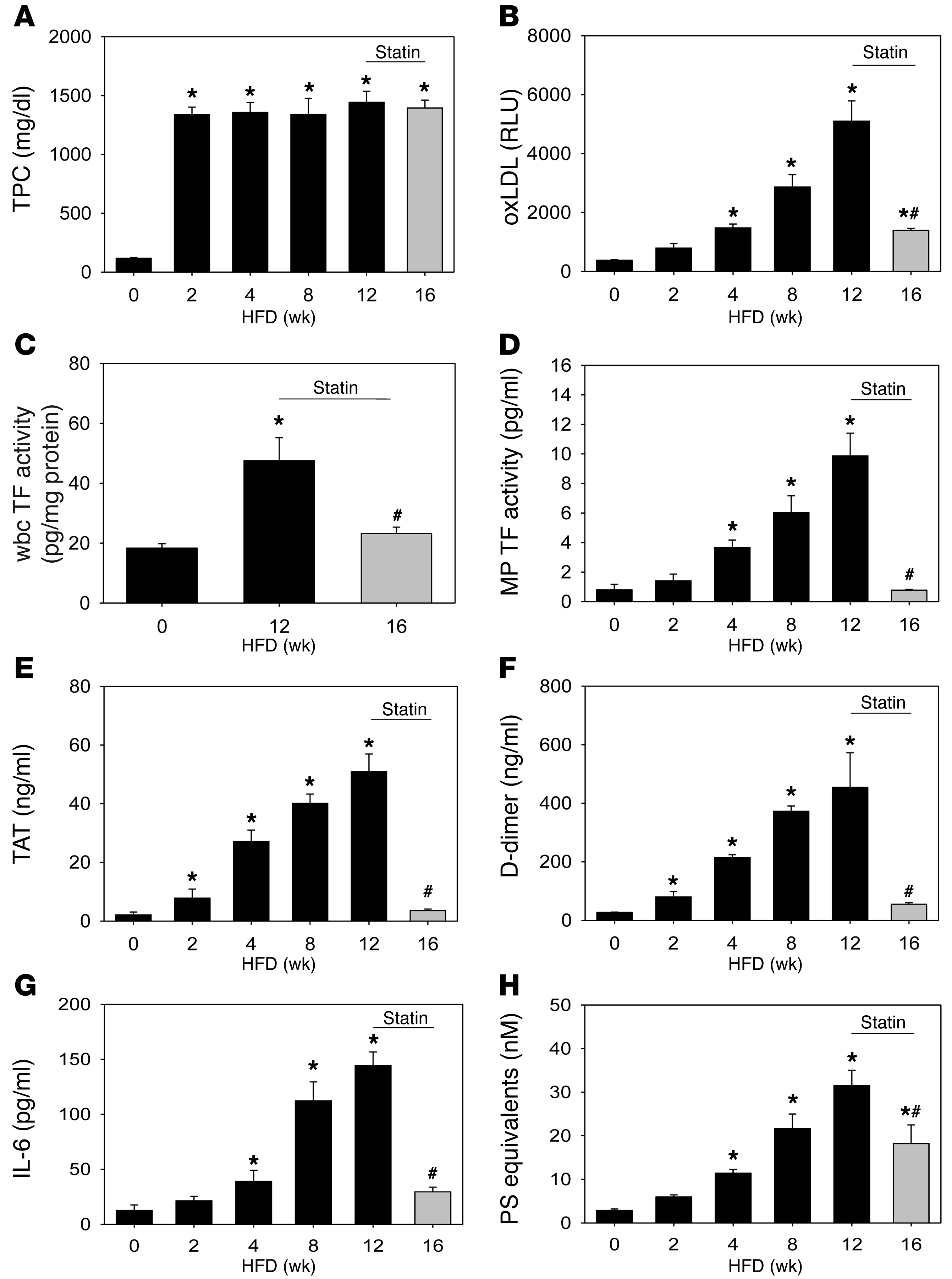

Hypercholesterolemia induces TF expression and activation of coagulation in mice.

We used LDLR-deficient (Ldlr–/–) mice fed a high-fat/high-cholesterol diet (HFD/Western) for up to 12 weeks as a model of hypercholesterolemia. We observed a rapid increase in plasma cholesterol levels at 2 weeks, followed by a plateau (Figure (Figure3A3A and Supplemental Table 2) and a time-dependent increase in plasma oxLDL (Figure (Figure3B).3B). Hypercholesterolemic mice also had an induction of wbc TF expression at 12 weeks (Figure (Figure3C)3C) and a time-dependent increase in MP TF activity, TAT, and D-dimer (Figure (Figure3,3, D–F). The increase of MP TF activity was linearly correlated (Pearson’s correlation) with both TAT (r = 0.92, P < 0.001) and D-dimer (r = 0.86, P < 0.009). Finally, we found that the level of IL-6 and the number of MPs were increased in a time-dependent manner in mice fed a HFD (Figure (Figure3,3, G and H).

Ldlr–/– mice were fed a HFD for up to 12 weeks and then fed a HFD with simvastatin (50 mg/kg/d) for an additional 4 weeks (16 weeks total). (A) Total plasma cholesterol (TPC), (B) oxLDL, (C) wbc TF activity, (D) MP TF activity, (E) TAT, (F) D-dimer, (G) IL-6, and (H) PS+ MPs. Histobars represent means ± SEM of 5 mice per group (HFD) or 10 mice per group (simvastatin). *P < 0.01, HFD versus 0-week control (chow). #P < 0.05, simvastatin treated versus week 12. Data were analyzed with 1-way ANOVA on ranks with Dunn’s post hoc (A and D–G) or 1-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak post hoc (B, C, and H).

Simvastatin reduces TF expression and activation of coagulation in hypercholesterolemic mice.

We examined the effect of administration of simvastatin on TF expression and activation of coagulation in hypercholesterolemic mice. Mice were fed a HFD for 12 weeks to activate coagulation and then fed a HFD containing simvastatin (50 mg/kg/d) for an additional 4 weeks. Simvastatin did not affect plasma cholesterol levels, weight, or other plasma lipids compared with 12 weeks of HFD (Figure (Figure3A3A and Supplemental Table 2). In contrast, simvastatin significantly reduced levels of oxLDL, wbc TF expression, MP TF activity, IL-6, activation of coagulation, and the number of MPs (Figure (Figure3,3, B–H).

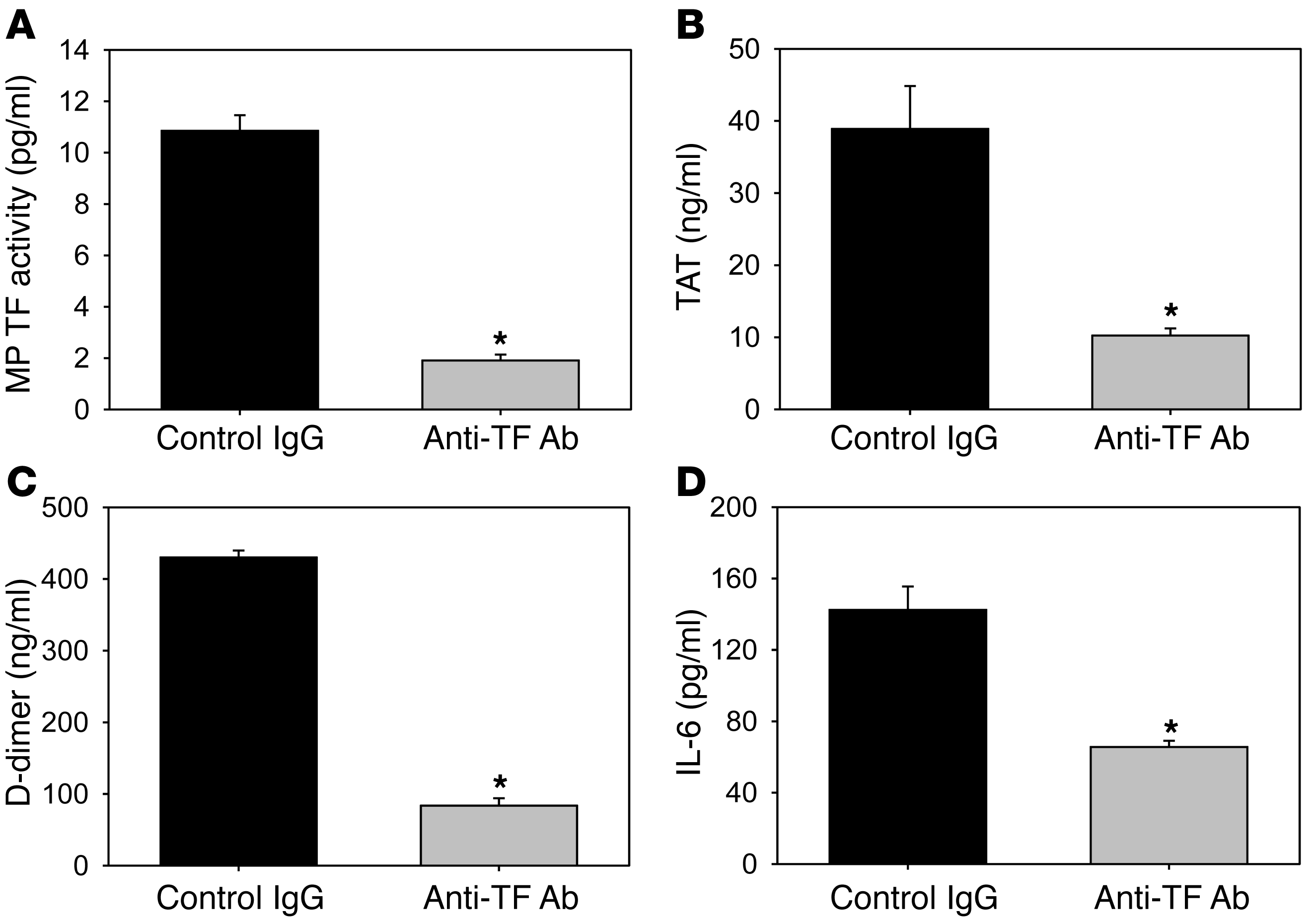

Role of TF in the activation of coagulation in hypercholesterolemic mice.

To directly examine the role of TF in the activation of coagulation in hypercholesterolemic mice, we used an inhibitory rat anti-mouse TF monoclonal antibody (1H1) (48). Mice were fed a HFD for 12 weeks and then injected with either a rat anti-mouse TF antibody or a control rat IgG antibody. MP TF activity was significantly reduced in mice treated with 1H1 compared with mice treated with a control antibody (Figure (Figure4A).4A). In addition, inhibition of TF significantly reduced the activation of coagulation (Figure (Figure4,4, B and C) and reduced the level of IL-6 (Figure (Figure4D).4D). No differences in lipid profiles were observed in mice treated with the anti-TF antibody compared with controls (Supplemental Table 2).

Ldlr–/– mice were fed a HFD for 12 weeks and injected with either a rat anti-mouse TF monoclonal antibody or a rat IgG control. (A) MP TF activity, (B) TAT, (C) D-dimer, (D) IL-6. Histobars represent mean ± SEM of n = 7 mice per group. *P < 0.001, rat anti-mouse TF treatment versus rat IgG. Data were analyzed using either a 2-tailed Student’s t test (A–C) or a Mann-Whitney rank sum (D).

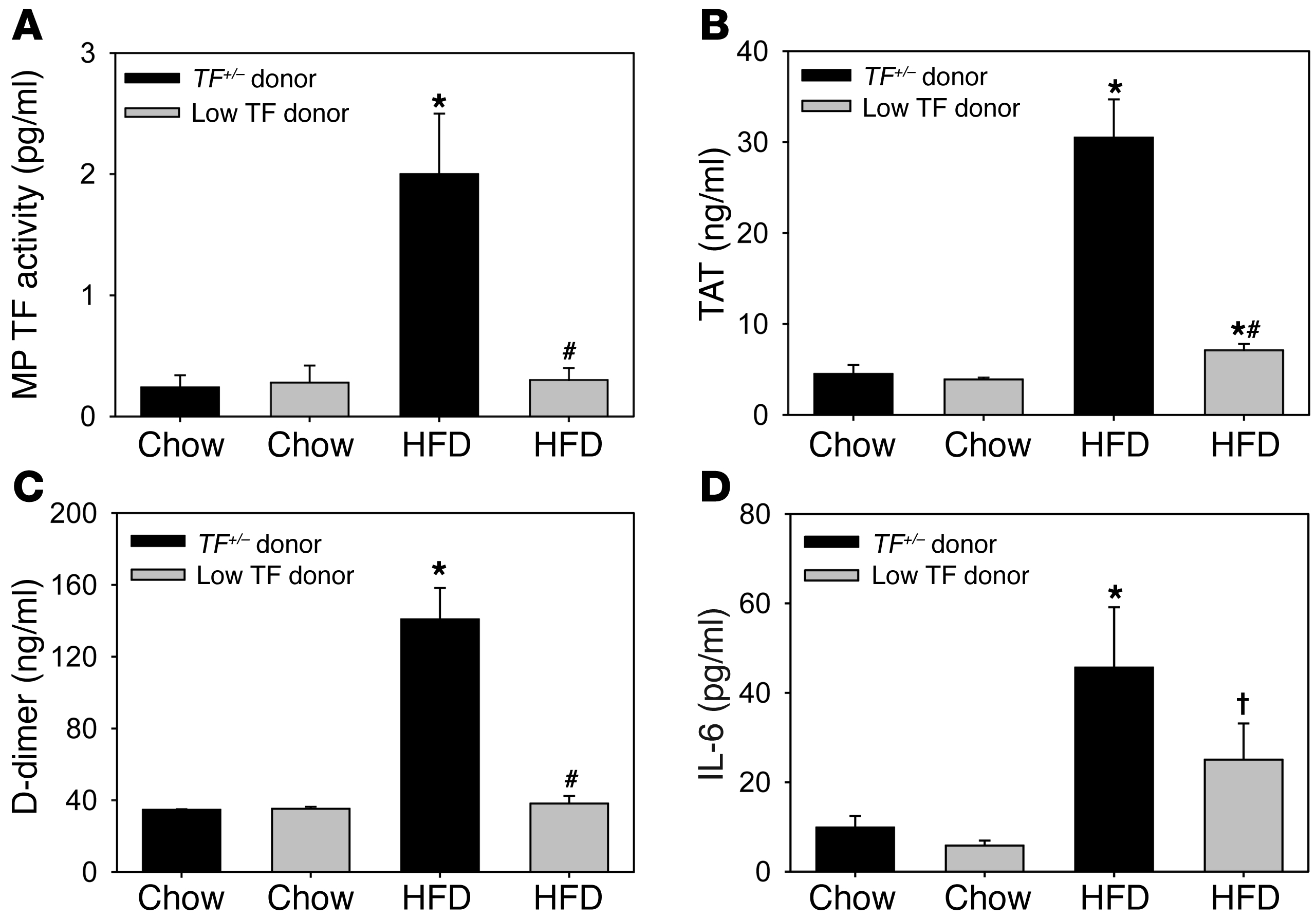

To assess the contribution of hematopoietic cell TF to the elevated levels of TF+ MPs and activation of coagulation in hypercholesterolemic mice, we performed a bone marrow transplantation experiment with cells deficient in TF expression. Irradiated Ldlr–/– mice were transplanted with bone marrow from either low TF mice (mTF–/–;hTF+), which express very low levels of TF (1% of wild-type levels), or bone marrow from heterozygous TF (TF+/–;hTF+) littermate control mice. Transplanted mice were fed a HFD for 12 weeks. Levels of MP TF activity and activation of coagulation were significantly lower in the hypercholesterolemic recipients that received low TF bone marrow compared with mice containing control marrow (Figure (Figure5,5, A–C). A deficiency of hematopoietic cell TF was also associated with a reduction in the level of IL-6, although this reduction did not achieve significance (Figure (Figure5D;5D; P = 0.08). No differences in lipid profiles were observed in irradiated mice that received low TF bone marrow compared with controls (Supplemental Table 2).

Irradiated Ldlr–/– mice were repopulated with either TF+/– or low TF bone marrow. Mice were fed either chow (n = 7 each group) or HFD (TF+/– n = 10, low TF n = 9) for 12 weeks and (A) MP TF activity, (B) TAT, (C) D-dimer, and (D) IL-6 were measured. Histobars represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.001, TF+/– HFD versus other groups; #P < 0.001, low TF HFD versus TF+/– HFD; †P = 0.08 low TF HFD versus TF+/– HFD. Data were analyzed with 2-way ANOVA with a Holm-Sidak post hoc.

Analysis of thrombosis in hypercholesterolemic mice.

We found that hypercholesterolemia is associated with a shorter time to occlusion, utilizing the ferric chloride (5%) model of arterial thrombosis (Supplemental Figure 2A). The addition of an anti-TF antibody increased the time to occlusion in these hypercholesterolemic mice (Supplemental Figure 2A). In addition, simvastatin treatment prolonged the time to occlusion in chow and HFD-fed Ldlr–/– mice (Supplemental Figure 2B). However, hypercholesterolemia increases TF expression in the vessel wall and also activates platelets (15, 16, 28). Therefore, we could not determine the contribution of elevated levels of TF+ MPs to the shortened occlusion time observed in these models.

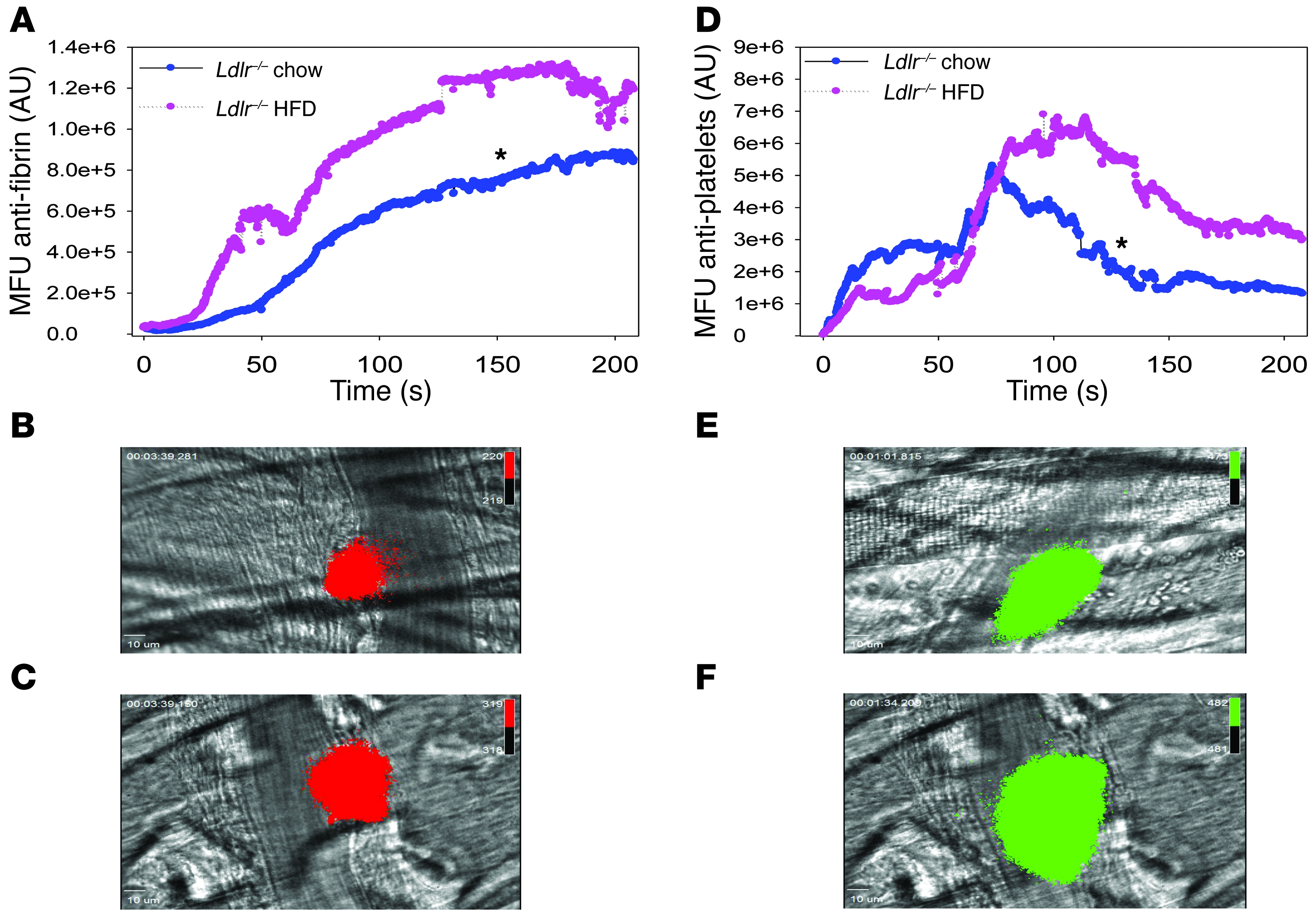

To more specifically analyze the role of the elevated levels of circulating TF+ MPs in thrombosis, we used the laser-injury cremaster arteriole model of thrombosis. We have found that low levels of hematopoietic cell–derived TF+ MPs present in healthy mice contribute to fibrin deposition in this model (49). We observed that fibrin accumulation in hypercholesterolemic mice was significantly increased compared with that in mice on a chow diet (Figure (Figure6A).6A). Representative images of fibrin deposition in chow and HFD-fed mice are shown in Figure Figure6,6, B and C, respectively. Similarly, we observed increased platelet accumulation in injured vessels of hypercholesterolemic mice compared with controls (Figure (Figure6,6, D–F).

Male Ldlr–/– mice fed either chow or HFD for 12 weeks (n = 3 mice per group) underwent cremaster arteriole laser injury (chow, 24 thrombi; HFD, 20 thrombi). (A) Fibrin and (D) platelet deposition were measured by intravital microscopy in which median fluorescent units (MFU) represented as AU were plotted against time for 200 seconds. Representative combined binarized fluorescence and bright field microscopy images of peak fibrin deposition in chow-fed (B) and HFD-fed (C) mice labeled with a fibrin-specific antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647 (red) or peak platelet accumulation in chow-fed (E) and HFD-fed (F) mice labeled with an anti-CD42b antibody conjugated to DyLight 488 (green). *P < 0.05 fibrin HFD versus chow and platelet HFD versus chow. Data analyzed as AUC with a Mann-Whitney rank sum. Original magnification, ×60. Scale bars: 10 μm.

Role of TLR4 and TLR6 in the induction of TF expression in hypercholesterolemic mice.

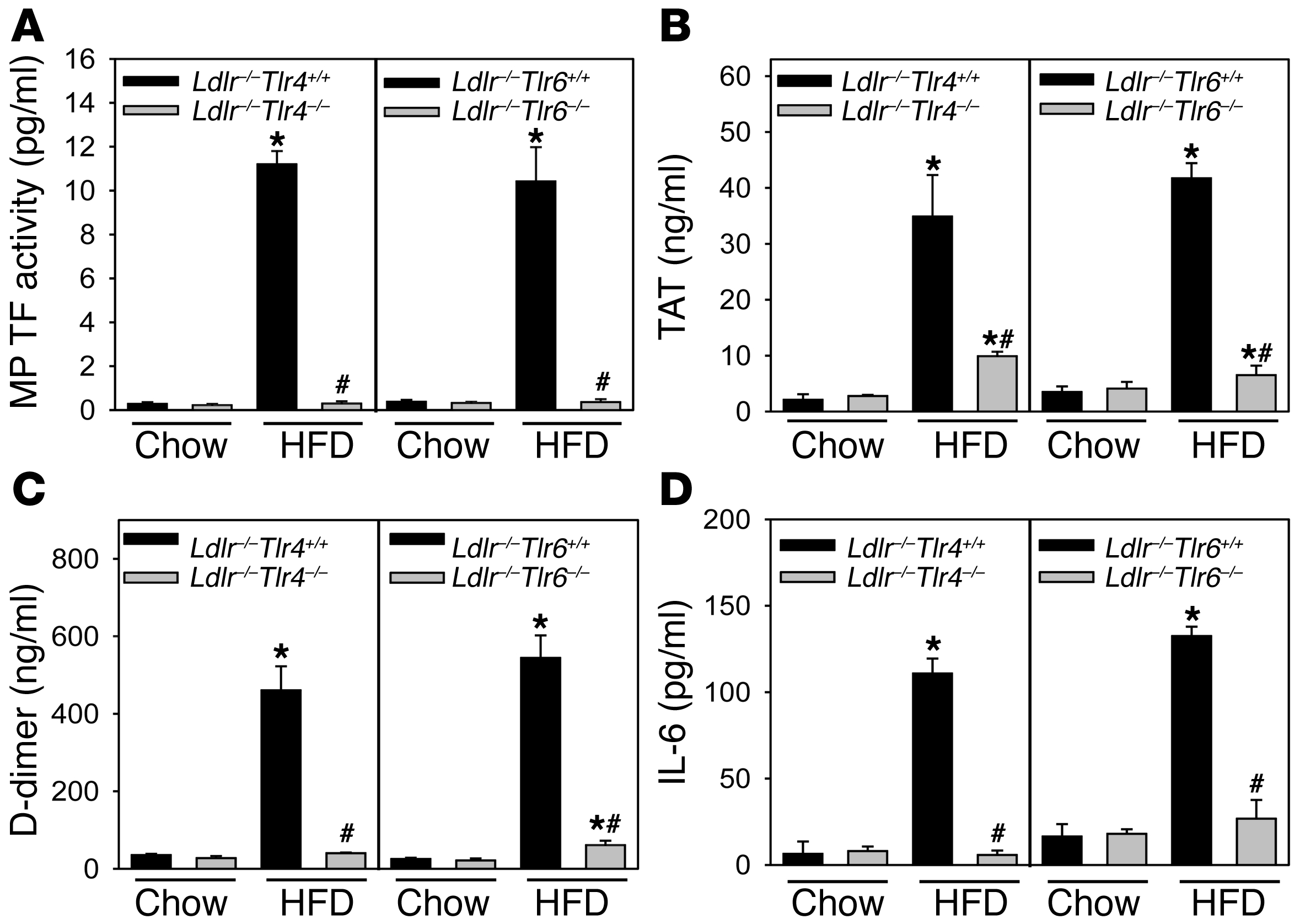

A recent study demonstrated that oxLDL binding to a CD36/TLR4/TLR6 heterotrimeric complex on macrophages and monocytic cells induces various chemokines (11). To determine whether hypercholesterolemic induction of TF expression and activation of coagulation are mediated by a similar complex, we used Ldlr–/– mice deficient in either TLR4 or TLR6. We found that an absence of either TLR4 or TLR6 dramatically reduced levels of MP TF activity and activation of coagulation in hypercholesterolemic mice (Figure (Figure7,7, A–C). Furthermore, TF activity of wbc isolated from these hypercholesterolemic Tlr4–/– or Tlr6–/– mice was significantly reduced (n = 6 per group; P < 0.001, data not shown) compared with wbc TF expression of littermate Tlr4+/+ or Tlr6+/+ controls. The high level of IL-6 observed in hypercholesterolemic mice was also significantly reduced in mice lacking TLR4 or TLR6 (Figure (Figure7D). 7D).

Ldlr–/–Tlr4+/+ (chow, n = 6; HFD, n = 10), Ldlr–/–Tlr4–/– (chow, n = 8; HFD, n = 26), Ldlr–/–Tlr6+/+ (chow and HFD, n = 7), and Ldlr–/–Tlr6–/– (chow, n = 6; HFD, n = 13) mice were fed either a chow diet or HFD for 12 weeks. (A) MP TF activity, (B) TAT, (C) D-dimer, and (D) IL-6. Histobars represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.001, Tlr4+/+ or Tlr6+/+ versus other groups; #P < 0.001, Tlr4–/– or Tlr6–/– HFD versus Tlr4+/+ or Tlr6+/+ HFD. Data were analyzed with 2-way ANOVA with a Holm-Sidak post hoc test.

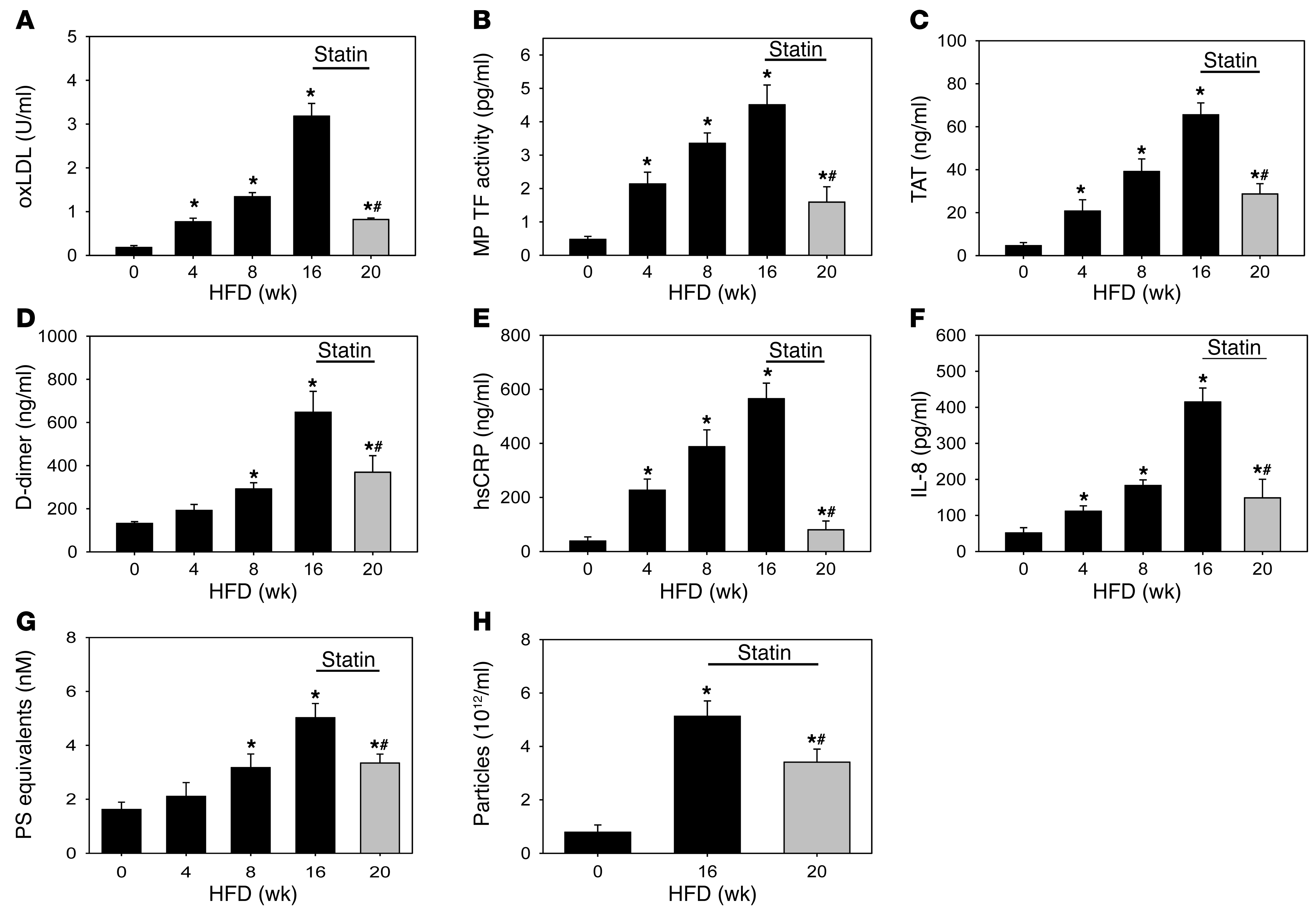

Induction of TF expression and activation of coagulation in hypercholesterolemic monkeys and the effect of simvastatin.

We extended the mouse studies by examining hypercholesterolemic induction of PBMC TF expression, MP TF activity, and activation of coagulation in a nonhuman primate model. We used African green monkeys fed a HFD for 16 weeks (Supplemental Table 3). Monkeys fed a HFD for a 16-week period had elevated levels of total plasma cholesterol, VLDL-C, and LDL-C compared with chow-fed controls (Supplemental Figure 3, A–C, and Supplemental Table 4). Levels of HDL-C and triglycerides remained unchanged during the course of the study (Supplemental Figure 3D and Supplemental Table 4). Unlike the rapid increase and plateau observed with LDL-C, we observed a time-dependent increase in oxLDL after feeding the monkeys a HFD (Figure (Figure8A).8A). Prolonged hypercholesterolemia in the monkeys resulted in an increase in PBMC TF activity (Supplemental Figure 3F) and a time-dependent increase in MP TF activity and activation of coagulation (Figure (Figure8,8, B–D). We also found that hypercholesterolemia significantly increased TF mRNA expression in PMBCs (Supplemental Figure 4A). Similarly, hypercholesterolemia induced TLR4, TLR6, and CD36 mRNA expression in PBMCs (Supplemental Figure 4, B–D). Next, we analyzed markers of inflammation and levels of MPs in hypercholesterolemic monkeys. IL-6 was not increased in hypercholesterolemic monkeys (data not shown). Therefore, we measured levels of the inflammatory markers hsCRP and IL-8. hsCRP and IL-8 were time dependently increased with hypercholesterolemia (Figure (Figure8,8, E and F). Finally, we observed a time-dependent increase in the number of MPs and elevation of total particles in hypercholesterolemic monkeys (Figure (Figure8,8, G and H).

African green monkeys were switched from a chow diet (0 weeks) to a HFD for 16 weeks before being fed a HFD containing simvastatin (10 mg/kg/d) for an additional 4 weeks (20 weeks total). Blood samples were collected at 0–20 weeks. (A) oxLDL, (B) MP TF activity, (C) TAT, (D) D-dimer, (E) hsCRP, (F) IL-8, (G) PS+ MPs, and (H) number of particles were measured. Histobars represent mean ± SEM of 12 monkeys. *P < 0.05, HFD versus chow; #P < 0.001, simvastatin treated versus 16 weeks. Data were analyzed with either 1-way ANOVA with a Holm-Sidak post hoc (A–C, E, and F) or 1-way ANOVA on ranks (D, G, and H).

To determine the effect of simvastatin, monkeys were fed a HFD for 16 weeks followed by 4 weeks with a HFD containing simvastatin (10 mg/kg/day). To confirm the bioavailability of simvastatin, we examined plasma levels of proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9 (PCSK9), which increases after statin administration as a compensatory mechanism to increase circulating LDL (50). PCSK9 was elevated by 60% in monkeys receiving simvastatin compared with controls (Supplemental Figure 3E). Simvastatin administration did not affect levels of plasma lipids and lipoprotein cholesterol (Supplemental Figure 3, A–D, and Supplemental Table 4). However, similar to the mouse studies, simvastatin reduced levels of PBMC TF expression, oxLDL, MP TF activity, TAT, and D-dimer in the hypercholesterolemic monkeys (Figure (Figure8,8, A–D, and Supplemental Figure 3F). In addition, simvastatin reduced the inflammatory markers and the number of MPs and particles (Figure (Figure8,8, E–H).

Discussion

In this study, we found that oxLDL induced TF expression in THP-1 monocytic cells and human monocytes in a TLR4-dependent manner. Furthermore, FH patients had elevated levels of both oxLDL and MP TF activity as well as activation of coagulation. We found that levels of MP TF activity increased in a time-dependent manner in parallel to markers of activation of coagulation in Ldlr–/– mice and monkeys fed a HFD. Hypercholesterolemia was also associated with increased fibrin deposition in a mouse model of microvascular thrombosis in which hematopoietic cell–derived TF+ MPs contribute to thrombosis (49). TF was responsible for the procoagulant state in hypercholesterolemic mice because inhibition of TF reduced the activation of coagulation. We found that a genetic deficiency of TF in hematopoietic cells dramatically reduced the activation of coagulation in hypercholesterolemic mice, which is consistent with the notion that monocytes are the primary source of pathologic TF expression in this model. In contrast, we recently found that activation of coagulation in a mouse model of endotoxemia was dependent on TF expression by both hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells (51). These results indicate that different cellular sources of TF contribute to the activation of coagulation in different pathologic states. This information is important for developing novel anticoagulant strategies that can inhibit inducible TF expression in specific cell types, such as monocytes, to reduce thrombosis.

Many studies have demonstrated that activation of the coagulation system can enhance inflammation in different diseases (52). Studies with septic baboons showed that inhibition of TF reduced IL-6 and IL-8 expression (53). In addition, we found that levels of IL-6 were reduced in endotoxemic mice with 1% TF expression compared with littermate controls with 50% levels of TF (54). In the current study, we found that inhibition of TF reduced levels of IL-6 in hypercholesterolemic mice. These results indicate that there is crosstalk between coagulation and inflammation during hypercholesterolemia.

Recent studies have demonstrated detectable levels of mmLDL and oxLDL in the circulation (6, 7). Indeed, several studies have demonstrated circulating oxidized lipids can be predictive of the presence, progression, and regression of cardiovascular disease (55, 56). We detected oxLDL in the circulation of hyperlipidemic mice, monkeys, and humans. In mice and monkeys, oxLDL in the plasma increased in a time-dependent manner after feeding a HFD. These results indicate that small amounts of mmLDL and oxLDL are present in the circulation during hypercholesterolemia and likely activate circulating monocytes.

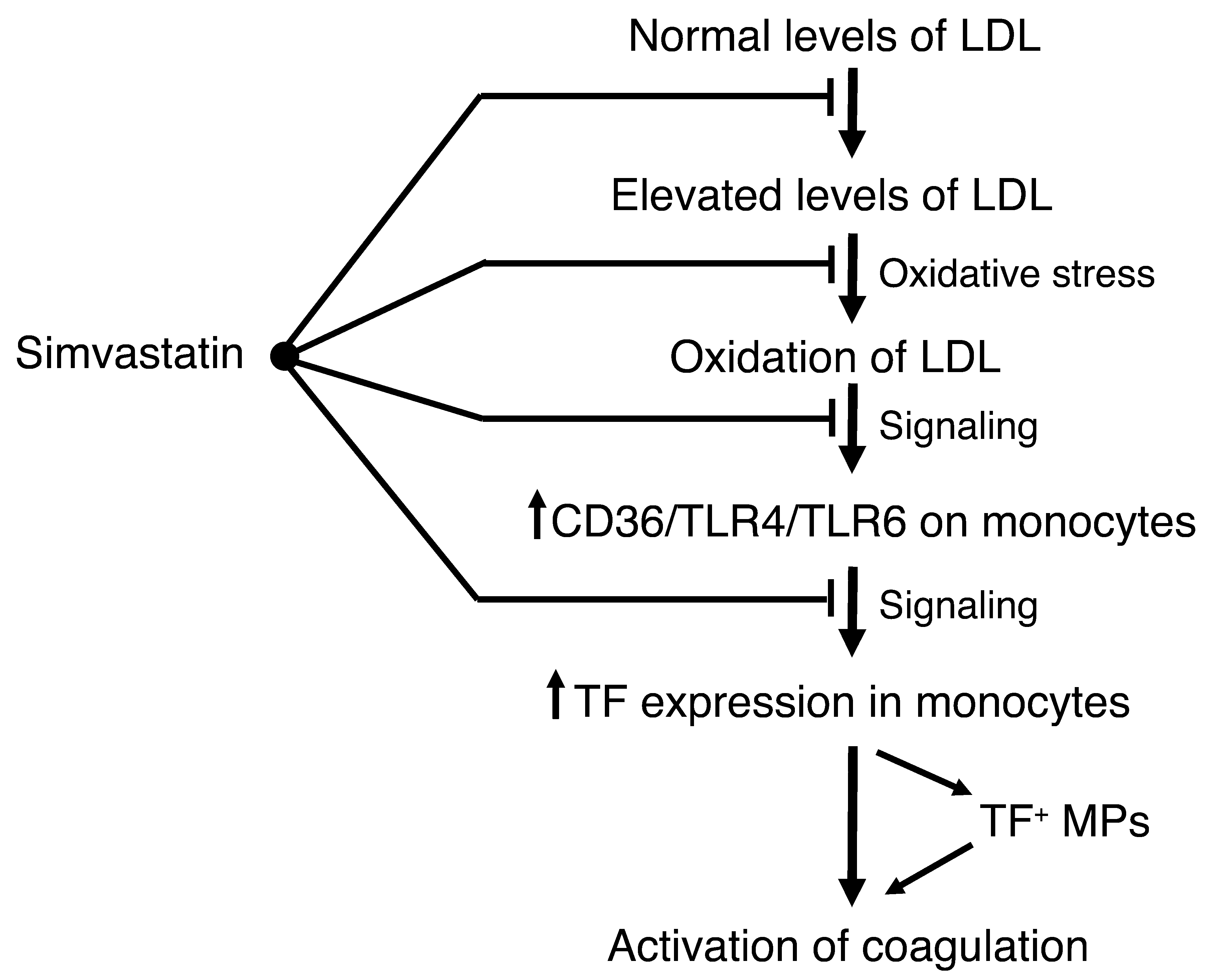

oxLDL induction of inflammatory mediators in murine macrophages was recently shown to be mediated by a CD36/TLR4/TLR6 heterotrimeric complex (11). Human THP-1 monocytic cells and human monocytes were also found to contain the same complex (11). Moreover, in patients with advanced cardiovascular disease, TLR4 expression is increased on PBMCs and monocytes by an undefined mechanism (12, 13). Our studies with both THP-1 cells and human monocytes demonstrated that oxLDL induction of TF expression and release of TF+ MPs required TLR4. Moreover, we found that a deficiency of either TLR4 or TLR6 was associated with reduced TF and IL-6 expression and systemic activation of coagulation in hypercholesterolemic mice. We found that prolonged hyperlipidemia increased TF, TLR4, TLR6, and CD36 mRNA expression in circulating monkey PBMCs, which is similar to the increased expression of TLR4 in monocytes of advanced cardiovascular disease patients (12, 13). These results indicate that hypercholesterolemia leads to the generation of oxLDL and the increased expression of the CD36/TLR4/TLR6 heterotrimeric complex on circulating monocytes. We propose that this complex is then activated by oxLDL, leading to the induction of both TF and IL-6 expression and the development of a prothrombotic and proinflammatory state (Figure (Figure9). 9).

In humans, but not mice or monkeys, statins reduce plasma cholesterol levels. In addition, our results indicate that simvastatin reduces activation of coagulation by inhibiting the oxidation of LDL, inhibiting the expression of the CD36/TLR4/TLR6 complex, and inhibiting monocyte TF expression and the release of TF+ MPs.

Simvastatin and rosuvastatin have been shown to reduce TF expression in the aorta and atherosclerotic lesions of hypercholesterolemic mice without reducing lipid levels (27, 39). In addition, simvastatin and pravastatin reduced inflammation and thrombogenicity in hypercholesterolemic pigs and monkeys without affecting cholesterol levels (57, 58). Simvastatin pretreatment was also shown to reduce LPS induction of monocyte TF expression and inflammation in healthy human volunteers (46). The JUPITER trial showed that administration of rosuvastatin to individuals with normal LDL but elevated levels of hsCRP significantly reduced the incidence of major cardiovascular events and symptomatic VTE (59). It was speculated that the reduction in thrombosis was due to statin inhibition of TF expression, but this was not analyzed (59). In our study, we found that simvastatin inhibited oxLDL induction of TF expression in THP-1 cells and human monocytes. In hypercholesterolemic mice and monkeys, simvastatin therapy reduced the levels of oxLDL independent of any effect on LDL-C or total cholesterol. This could be due to either the inhibition of oxidative modification of LDL or via mobilization and clearance of proinflammatory oxidized phospholipids (60–62). Furthermore, simvastatin treatment of hypercholesterolemic mice and monkeys also reduced wbc and PBMC TF expression, MP TF activity, and activation of coagulation (Figure (Figure9).9). TLR4, TLR6, and CD36 mRNA expression in circulating PBMCs was also reduced in statin-treated monkeys, which is similar to simvastatin- and rosuvastatin-induced decreases in human monocytes expressing TLR4 (63). Our results suggest that the ability of statins to reduce TF may explain the mechanism by which statins reduce VTE in hypercholesterolemic patients.

Methods

Addition information is provided in Supplemental Methods.

Cell culture.

Human monocytic THP-1 cells were obtained from ATCC. Cells were grown in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1 mM HEPES, 1% glucose, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were treated with native LDL or oxLDL obtained from Biomedical Technologies Inc. The TLR4 inhibitor CLI-095 was obtained from Invivogen. The carboxylate (activated) form of simvastatin was purchased from Calbiochem. Polymyxin B and LPS (E. coli; 0111:B4) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Viability was assessed using the alamarBlue Assay (Invitrogen).

Human monocyte isolation.

Human blood was collected into BD glass vacutainers (3.2% sodium citrate), and PBMCs were isolated using Ficoll-Paque Plus (GE Healthcare) from 5 separate donors. Human monocytes were isolated by negative selection (Monocyte Isolation Kit II; Miltenyi Biotech).

Clotting assay and MP TF activity assay.

The TF activity of cell lysates was measured using a 1-stage clotting assay with a STart 4 Clotting Machine (Diagnostica Stago), as described (51). MP TF activity was measured as described (64).

Human subjects.

Human subjects with FH were recruited at the University of Kansas Medical Center. The patient demographics are described in Supplemental Table 1. Apheresis was conducted as previously described (65). Control plasma samples (n = 17) were purchased from Innovative Research and were matched for age, sex, and race (Supplemental Table 1).

Mice and diet.

Male Ldlr–/– mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Ldlr–/–Tlr4+/+ and Ldlr–/–Tlr4–/– littermate mice were generated by interbreeding Ldlr–/–Tlr4+/– mice. The same strategy was used to generate Ldlr–/–Tlr6+/+ and Ldlr–/–Tlr6–/– littermates. mTF–/–;hTF+ (low TF) mice and littermate TF+/–;hTF+ controls were used as donors in bone marrow transplant experiments (66). To induce hypercholesterolemia, mice were fed a diet enriched with saturated milk fat (21% w/w) and cholesterol (0.15% w/w; diet TD.88137 from Harlan Teklad). Simvastatin (50 mg/kg/d) was administered in the diet, as described (27). Blood was collected and processed as previously described (51, 64). Then wbc were isolated by lysing erythrocytes using an ammonium chloride solution.

Bone marrow transplantation.

Male recipient Ldlr–/– mice (8 weeks old) were irradiated with a total of 11 Gy (2 doses of 550 rads 4 hours apart) using a Cs137 irradiator (J.L. Shepherd). Irradiated mice were repopulated with bone marrow (2 × 106 cells per animal) harvested from TF+/– (n = 17) or low-TF (n = 16) donor mice via retroorbital injection. Mice were allowed to recover for 4 weeks and then either fed a HFD (n = 10, TF+/–; n = 9, low TF) or chow (n = 7, TF+/– and low TF) for 12 weeks.

Inhibition of TF.

Male Ldlr–/– mice (n = 14) were fed a HFD for 12 weeks and then split into 2 equal groups. One group received intraperitoneal injections of a rat anti-mouse TF monoclonal antibody (1H1, 20 mg/kg), while the other received the isotype control antibody (rat IgG2a; 20 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich). Injections were performed on day 0 and day 3, and mice were then euthanized and blood collected on day 6.

Monkeys and diet.

Adult male African green monkeys (Chlorocebus aethiops) (n = 12, age 5–10 years) were obtained from St. Kitts Island. Monkeys were housed under the care of the Wake Forest University Health Sciences (WFUHS) Animal Resources Program. Monkeys were fed either a chow diet (Monkey Diet 5038; Lab Diet) or a HFD semi-synthetic diet (Supplemental Table 3) to induce hypercholesterolemia. The monkeys were then fed a HFD containing simvastatin (10 mg/kg/d; Supplemental Table 3), which was provided by Merck and Co. Monkeys were sedated with 10 mg/kg ketamine. and blood was drawn into Vacutainers containing sodium citrate (3.2% sodium citrate; BD). Blood was spun at 1,500 g for 15 minutes to prepare plasma and stored at –80°C. Monkey PBMCs were isolated using the same protocol as used for the isolation of human PBMCs.

ELISA measurements.

The following commercial kits were used: mouse IL-6 and human IL-8 (R&D Systems), human oxLDL (Caymen Chemicals), human hsCRP (ALPCO Immunoassays), human D-dimer (Diagnostica Stago), and TAT Enzygnost Micro Kit (Dade Behring/Siemens).

PCSK9 analysis.

Plasma PCSK9 levels were determined using an in-house ELISA from Merck Pharmaceuticals. A capture antibody (E07) and a biotinylated secondary antibody (B20) were utilized for detection of PCSK9. Standard curves (11-point 2-fold dilutions from 1 μg/ml) were generated using purified African green monkey PCSK9.

Plasma lipid analysis.

Human and mouse plasma lipids were analyzed with the following commercial kits: total plasma cholesterol (Total Cholesterol E), triglycerides (L-Type TG M), and HDL-C (L-Type HDL-C) from Wako Chemicals. LDL-C was calculated using the Friedewald equation. VLDL-C was then calculated by subtracting HDL-C and LDL-C from total plasma cholesterol. Monkey total plasma cholesterol and triglycerides were measured using the Pointe Scientific Cholesterol Reagent Set and the L-type TG M assay (Wako Chemicals), respectively. Plasma lipoprotein cholesterol distribution was determined as described previously (67).

Measurements of mouse plasma oxLDL.

OxLDL was measured in the mouse plasma as previously described (68).

Ferric chloride carotid arterial thrombosis model.

Ferric chloride carotid arterial thrombosis was performed as described (16).

Laser-injury thrombosis model.

Intravital microscopy, laser-induced cremaster vessel-wall injury, and intravital imaging have been described (49).

Measurement of MPs.

Plasma MPs were evaluated utilizing a phosphatidylserine (PS) capture and prothrombinase complex thrombin generation assay (Zymuphen MP Activity; Aniara). The results are expressed in PS equivalents (nM). The particle count in plasma was measured using the NanoSight NS500 system (NanoSight), which focuses a laser beam through the plasma, as described (69).

Real-time PCR analysis of monkey PBMCs.

Total RNA was extracted from monkey PBMCs in TRIzol (Invitrogen). cDNA was synthesized, and real-time PCR performed as previously described (51). TF, TLR4, and CD36 TaqMan primers were obtained from Applied Biosystems, while TLR6 FAM-labeled primers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies.

Statistics and data representation.

All bar and line graphs were created with Sigma Plot v.11 (SPSS). All statistical analysis was performed using SigmaStat, now incorporated into Sigma Plot v.11. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. For 2-group comparison of parametric data, a 2-tailed Student’s t test was performed, while nonparametric data were analyzed with a Mann-Whitney rank sum. Statistical significance between multiple groups was assessed by ANOVA on ranks with a Dunn’s post hoc, 1-way ANOVA with Holm Sidak post hoc, or 1-way ANOVA with Holm Sidak post hoc, when appropriate. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Study approval.

All mouse studies were performed with the approval of the University of North Carolina IACUC. All studies with monkeys were approved by the Wake Forest University School of Medicine IACUC. All patients and controls provided written informed consent in accordance with University of Kansas Medical Center and University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocols for plasma and monocyte isolation, respectively.

Note added in proof.

After the submission of this manuscript, a study demonstrated a role of hematopoietic cell TF in diet-induced obesity (70). We similarly observed that Ldlr–/– mice reconstituted with TF-deficient bone marrow and fed a HFD exhibited less weight gain (Supplemental Table 2), less epididymal and retroperitoneal fat pad weight (unpublished data), and less total adipocity (unpublished data) compared with mice reconstituted with control bone marrow. Our results are consistent with the conclusion that hematopoietic cell TF signaling promotes obesity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kathryn L. Kelley, Jessica Warden, D. Anthony Barcel, and Rebecca Lee for their skilled technical assistance. We would like to thank L. Petersen (Novo Nordisk) for providing mouse FVIIa. This work was supported by NIH grants PO1-HL006350 (to N. Mackman), R01-HL095096 (to N. Mackman), R00-HL088528 (to R.E. Temel), R01-HL086674 (to S. Nagarajan), P01-HL087203 (to B. Furie), R01-HL092125 (to B.C. Furie), and AHA50608351216 (to J.P. Luyendyk). A. Phillip Owens III was supported by an American Heart Association Mid-Atlantic postdoctoral fellowship (09POST2250515) and is currently supported by a NIH F32 NRSA postdoctoral fellowship (1F32-HL099175-01). F. Passam is a recipient of an American Society of Hematology–European Hematology Association International Exchange fellowship.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Nigel Mackman is a consultant for Merck.

Citation for this article: J Clin Invest. 2012;122(2):558–568. 10.1172/JCI58969.

See the related Commentary beginning on page 478.

References

Articles from The Journal of Clinical Investigation are provided here courtesy of American Society for Clinical Investigation

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1172/jci58969

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

http://www.jci.org/articles/view/58969/files/pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Article citations

Hepatocyte-independent PAR1-biased signaling controls liver pathology in experimental obesity.

J Thromb Haemost, 22(11):3191-3198, 08 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39122189

Mitigating Vascular Inflammation by Mimicking AIBP Mechanisms: A New Therapeutic End for Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease.

Int J Mol Sci, 25(19):10314, 25 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39408645 | PMCID: PMC11477018

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Monocyte bioenergetics: An immunometabolic perspective in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis.

Cell Rep Med, 5(5):101564, 10 May 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38733988 | PMCID: PMC11148801

Extracellular vesicles in venous thromboembolism and pulmonary hypertension.

J Nanobiotechnology, 21(1):461, 30 Nov 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38037042 | PMCID: PMC10691137

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Crosstalk of ferroptosis and oxidative stress in infectious diseases.

Front Mol Biosci, 10:1315935, 07 Dec 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38131014 | PMCID: PMC10733455

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (108) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Teaching an old dog new tricks: potential antiatherothrombotic use for statins.

J Clin Invest, 122(2):478-481, 03 Jan 2012

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 22214843 | PMCID: PMC3266801

Hyperlipidemia, tissue factor, coagulation, and simvastatin.

Trends Cardiovasc Med, 24(3):95-98, 07 Sep 2013

Cited by: 33 articles | PMID: 24016468 | PMCID: PMC4102256

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Platelet tissue factor activity and membrane cholesterol are increased in hypercholesterolemia and normalized by rosuvastatin, but not by atorvastatin.

Atherosclerosis, 257:164-171, 16 Dec 2016

Cited by: 17 articles | PMID: 28142075

Colchicine inhibits the prothrombotic effects of oxLDL in human endothelial cells.

Vascul Pharmacol, 137:106822, 21 Nov 2020

Cited by: 9 articles | PMID: 33232770

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NHLBI NIH HHS (15)

Grant ID: 1F32-HL099175-01

Grant ID: R00-HL088528

Grant ID: R01 HL095096

Grant ID: P01-HL087203

Grant ID: T32 HL091797

Grant ID: R01 HL086674

Grant ID: R01-HL092125

Grant ID: P01 HL006350

Grant ID: P01-HL006350

Grant ID: P01 HL087203

Grant ID: R00 HL088528

Grant ID: R01 HL092125

Grant ID: R01-HL086674

Grant ID: R01-HL095096

Grant ID: F32 HL099175