Abstract

Free full text

Chromosome Y Regulates Survival Following Murine Coxsackievirus B3 Infection

Associated Data

Abstract

Coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3) contributes to the development of myocarditis, an inflammatory heart disease that predominates in males, and infection is a cause of unexpected death in young individuals. Although gonadal hormones contribute significantly to sex differences, sex chromosomes may also influence disease. Increasing evidence indicates that Chromosome Y (ChrY) genetic variants can impact biological functions unrelated to sexual differentiation. Using C57BL/6J (B6)-ChrY consomic mice, we show that genetic variation in ChrY has a direct effect on the survival of CVB3-infected animals. This effect is not due to potential Sry-mediated differences in prenatal testosterone exposure or to differences in adult testosterone levels. Furthermore, we show that ChrY polymorphism influences the percentage of natural killer T cells in B6-ChrY consomic strains but does not underlie CVB3-induced mortality. These data underscore the importance of investigating not only the hormonal regulation but also ChrY genetic regulation of cardiovascular disease and other male-dominant, sexually dimorphic diseases and phenotypes.

Coxsackievirus infection of the heart can lead to myocarditis and cause unexpected death in individuals less than 40 years old (Woodruff 1980). Like most heart diseases, myocarditis predominates in males by a 2:1 ratio and displays a greater severity of disease over females. Susceptibility is greatest in men during the first year of life and after puberty. However, females are often rendered susceptible to myocarditis during pregnancy, during the postpartum period, and in individuals over 40 years of age, suggesting a role for hormonal influences on disease development (Woodruff 1980).

The coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3)-induced mouse model of experimental myocarditis exhibits many of the same characteristics as the human disease (Gauntt et al. 1979; Grodums and Dempster 1959b; Huber et al. 1982; Matsumori and Kawai 1980; Reyes and Lerner 1985; Wong et al. 1977). Adult male mice less than 40 weeks of age are more susceptible to CVB3-induced myocarditis than females of the same age. However, both males and females less than 3 weeks of age or over 40 weeks of age are equally susceptible, indicating that age-related changes in sex-associated hormones may influence experimental myocarditis susceptibility (Grodums and Dempster 1959a; Lyden et al. 1987a). In this regard, susceptibility was significantly reduced in male mice that were orchiectomized prior to infection (Huber et al. 1982). However, when orchiectomized males received exogenous testosterone or progesterone prior to infection, disease susceptibility returned to similar levels seen in intact males (Huber et al. 1982). In contrast, treatment of orchiectomized males with estrogens provided protection from disease. Moreover, in vitro experiments revealed that male and female cardiomyocytes exhibited enhanced infectivity when cultured in the presence of progesterone or testosterone, but not estradiol, due to increased virus binding to the cell surface (Lyden et al. 1987b). Further studies demonstrated that testosterone induced an approximately 6-fold increase in virus receptor expression in cardiomyocytes (Lyden et al. 1987a). Therefore, these studies indicate that androgens enhance virus receptor expression and disease susceptibility, whereas estrogens provide protection from disease.

Sex hormones also influence the immune response mounted against CVB3 infection in mice. Susceptibility to CVB3-induced myocarditis in males is dependent on the induction of a CD4+ Th1 cellular response, and the immune bias toward a Th1 phenotype requires activated γδ Tcells (Huber and Pfaeffle 1994; Huber et al. 2001). Orchiectomy led to an increase in immune regulatory cells in the heart, including regulatory T cells, suggesting that testosterone inhibits anti-inflammatory cell recruitment and enhances susceptibility to disease (Frisancho-Kiss et al. 2009). In contrast, resistance to disease in females was associated with a preferential Th2 response to infection (Huber and Pfaeffle 1994). However, treatment of female mice with testosterone in vivo caused a shift from the protective Th2 cell response toward the Th1 phenotype, leading to enhanced susceptibility in these mice (Huber and Pfaeffle 1994).

Clearly, testosterone plays a critical role in the sexual dimorphism in susceptibility to myocarditis by regulating not only viral infectivity but also differences in innate and adaptive antiviral immune responses. While a clear role for sex-associated hormones, and particularly testosterone, can be observed in the male-specific sexual dimorphism during CVB3 pathogenesis, the effect of Chromosome Y (ChrY) on disease has not been examined. Here, we provide direct evidence that ChrY regulates survival following CVB3 infection and suggest that the mechanism is unrelated to biological differences in testosterone production among the strains.

Materials and Methods

Mice

C57BL/6J, C57BL/6J-ChrY129S1/SvImJ/NaJ, C57BL/6J-ChrYA/J/NaJ, C57BL/6J-ChrYMET/J, C57BL/6JEi-ChrYAKR/J/EiJ, C57BL/6JEi-ChrYBUB/BnJ/EiJ, C57BL/6JEi-ChrYLEWES/EiJ, C57BL/6JEi-ChrYRF/J/EiJ, C57BL/6JEi-ChrYSJL/J/EiJ, C57BL/6JEi-ChrYST/bJ/EiJ, C57BL/6JEi-ChrYWSB/Ei/EiJ, B6Ei.MA-AChrYMA/MyJ/EiJ, and B6Ei.SWR-AChrYSWR/J/EiJ were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and bred and maintained on the C57BL/6J background in the animal facility at the University of Vermont. B6-ChrY129F11/Pas and B6-ChrYNkt-129/Pas mice were obtained from the Pasteur Institute (Paris, France) and bred and maintained in the animal facility at Brown University. Only male mice were used in the experiments. All animal protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Vermont and Brown University.

Virus and infection

The H3 variant of CVB3 was made from an infectious cDNA clone as previously described (Knowlton et al. 1996). Mice were infected by intraperitoneal injection of 0.5 ml of PBS containing 100 or 50 PFU CVB3 and killed seven days after infection.

Serum testosterone

Eight-week-old mice were bled by tail vein, and the samples were spun down for 20 min at 16,000 g to extract serum. Serum testosterone levels were measured using a testosterone enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI). Briefly, serum samples were diluted with 1 part steroid displacement reagent for every 99 parts sample. Each sample was diluted 1:10 and 1:20 in PBS and added to the 96-well plate in duplicate, followed by the primary antibody, and incubated at room temperature for 1 hr while shaking. Wells were washed and conjugate was added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 1 hr while shaking. Wells were washed, and the pNpp substrate was added to each well and incubated at 37° for 1 hr without shaking. Stop solution was added, and the plate was read immediately with optical density at 405 nm.

Lymphocyte isolation

Perfused and intact liver, spleen, and thymus were extracted from 8-week-old mice and placed in 50 ml tubes containing RPMI 1640 media with 10% FCS and shipped overnight on ice to Brown University. Thymocytes were minced and washed once in 1% PBS-serum. To obtain splenic lymphocytes, spleens were minced, passed through nylon mesh (Tetko, Kansas City, MO), washed once in 1% PBS-serum, and then cell suspensions were layered on lympholyte-M (Cedarlane Laboratories Ltd., Canada). Hepatic lymphocytes were prepared by mincing and passing through a 70 mm nylon cell strainer (Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ). After washing three times in 1% PBS-serum, cell suspensions were layered on a two-step discontinuous Percoll gradient (Pharmacia Fine Chemicals, Piscataway, NJ). Splenocytes and hepatic lymphocytes were collected after centrifugation for 20 min at 900 g.

Antibodies and flow cytometric analysis

TCRβ-FITC (or APC), CD8α-efluor 450 (or Pacific blue), CD4-APC (or perCP), CD44-efluor 780, NK1.1-PE-Cy7, and CD24-FITC were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). CD1d Tetramer-PE was obtained from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease MHC Tetramer Core Facility at Emory University (Atlanta, GA). Cells were suspended in buffer composed of PBS containing 1% FCS. Cells were first incubated with 2.4G2 mAb and stained with mAbs specific for cell surface markers for 20 min at room temperature. Depending on the experiment and the tissue, from 2.5 × 105 to 1 × 106 events were collected in the lymphoid gate on a FACSAria. The data were analyzed using FlowJo (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 5.0c (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The specific tests used are detailed in the figure legends. A P value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results and Discussion

ChrY polymorphism regulates CVB3-induced mortality

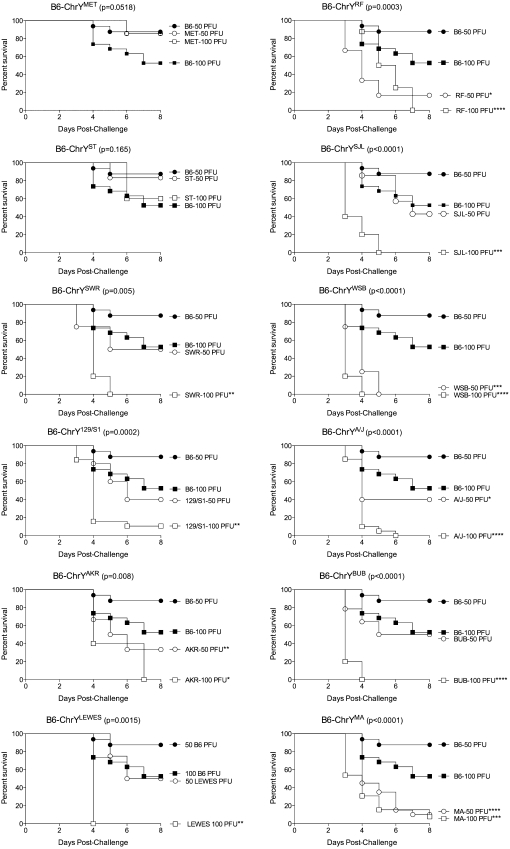

To test whether ChrY polymorphism influences survival following CVB3 infection, we utilized a panel of consomic strains in which C57BL/6J (B6) mice inherit ChrY donated from either Mus musculus musculus (musculus) or Mus musculus domesticus (domesticus) subspecies (B6-ChrY). The B6-ChrY consomic strains used include B6-ChrYSJL, B6-ChrYSWR, B6-ChrYAKR, B6-ChrYMA, B6-ChrYST, B6-ChrYLEWES, B6-ChrYBUB, B6-ChrYRF, B6-ChrYMET, B6-ChrYWSB, B6-ChrYA/J, and B6-ChrY129S1, in which the mouse strain donating ChrY to B6 is indicated in superscript. Male mice from the panel of B6-ChrY consomic strains, as well as wild-type B6 male mice, were infected intraperitoneally with either 100 or 50 PFU CVB3 and monitored for survival for eight days following infection. The survival data obtained from each B6-ChrY consomic strain at each virus dose was compared with wild-type B6 and tested for significant differences using a log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test (supporting information, File S1).

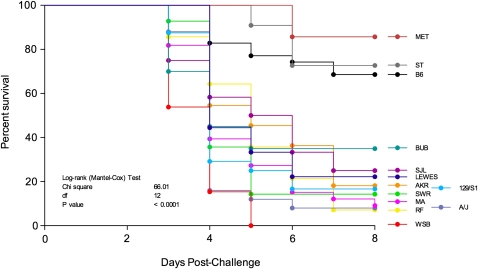

B6-ChrYST and B6-ChrYMET mice were the only strains that did not display a decrease in survival following infection with either 100 or 50 PFU CVB3 when compared to B6. B6-ChrYLEWES, B6-ChrYSWR, B6-ChrYSJL, B6-ChrY129/S1 and B6-ChrYBUB mice only showed a decrease in survival compared with B6 when infected with 100 PFU CVB3 but not at the 50 PFU dose. Conversely, B6-ChrYRF, B6-ChrYMA, B6-ChrYAKR, B6-ChrYSWR, B6-ChrYWSB, and B6-ChrYA/J mice were significantly more susceptible to CVB3-induced mortality at both the 100 and 50 PFU doses compared with B6 (Figure 1). Transforming the data into a single susceptibility value by averaging the 100 and 50 PFU response groups for each strain indicated that B6-ChrY consomic strains exhibit a continuous distribution of CVB3-induced mortality phenotypes (Figure 2). Because the only genetic difference among these strains is the inheritance of ChrY, the differences in mortality rates can be directly attributed to polymorphic differences in ChrY. We have designated this locus as YCvb3 (CVB3 susceptibility region of ChrY). With respect to candidates for YCvb3, there are three loci that are biologically relevant to CVB3-induced mortality: YNkt (iNKT-determining region of ChrY) (Wesley et al. 2007), Sry (sex determining region of ChrY), and YCmc (cardiomyocyte size–determining region of ChrY) (Llamas et al. 2007, 2009).

ChrY polymorphism influences susceptibility to CVB3-induced mortality. B6 and B6-ChrY consomic strains were infected with 100 or 50 PFU CVB3 and monitored for survival. Significance of observed differences were determined using a log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test (n = 5–20). The legend labels indicate the mouse strain donating ChrY to B6. P values in graph title represent overall P values, and asterisks in the legend labels represent significant differences in survival between B6 and the B6-ChrY consomic strains at the indicated virus dose. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

CVB3-induced mortality exhibits a continuous distribution across the B6-ChrY consomic strains. The survival data obtained from the infection with 100 and 50 PFU in Figure 1 was combined for each consomic strain and plotted in a single graph. The legend labels indicate the mouse strain donating ChrY to B6. Significance of observed differences measured using a log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test (n = 5–20).

Differences in basal invariant natural killer T cell numbers do not influence the mortality of CVB3-infected B6-ChrY consomic mice

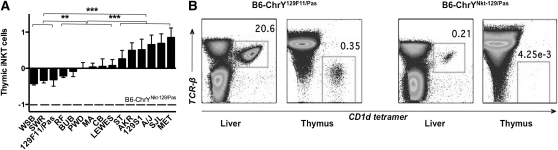

Invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells are an important immune regulator during CVB3 infections, and the treatment of mice with α-galactosylceramide, an agonist for iNKT cells, protects the mice from CVB3-induced disease (Liu and Huber 2011; Wu et al. 2010). Consequently, YNkt, a locus that leads to a profound deficiency in iNKT cells in male B6-ChrYNkt-129F11/Pas mice (Wesley et al. 2007), is a functionally relevant candidate for YCvb3. Therefore, we analyzed the number of iNKT cells in the liver, spleen, and thymus of all B6-ChrY consomic strains by staining leukocytes for TCRβ+ and CD1d-tetramer+ cells and assessing the percentage of iNKT cells by flow cytometry (File S1).

YNkt polymorphism influences the frequency of iNKT cells in B6-ChrY consomic strains. (A) Thymocytes were analyzed by flow cytometry for the percentage of iNKT cells by staining for TCRβ- and CD1d-expressing cells for each B6-ChrY consomic strain and then normalizing to B6 controls. The data are represented as the difference in the percentage iNKT from B6 (B6 is the baseline). The X-axis labels indicate the mouse strain donating ChrY to B6. The hatched line represents the normalized percentage of iNKT cells seen in B6-ChrYNkt-129/Pas mice. The significance of observed differences among the strains was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison test. (B) Representative liver and thymus staining from (left) male B6-ChrY129F11/Pas inheriting the ChrY129F11/Pas from mice by natural breeding and (right) male B6-ChrYNkt-129/Pas mice carrying the ChrY129/Pas transmitted from male founder mice derived from 129/Pas embryonic stem cells. n ≥ 4 mice per group. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

As the various B6-ChrY consomic strains were analyzed throughout multiple experiments, the data derived from each consomic line was normalized to the B6 data from each independent experiment to control for interexperimental variability. Interestingly, we observed a continuous distribution of iNKT cells across the ChrY strains. The analysis of thymic iNKT cells produced three significant groupings (Figure 3A). Similar continuous distributions of iNKT cells were also observed for liver and splenic iNKT cell numbers (data not shown).

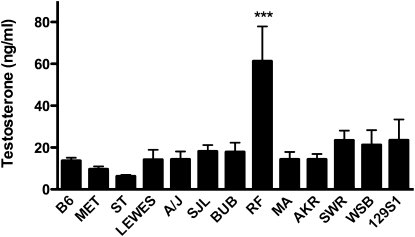

Differences in CVB3-induced mortality are not the result of changes in adult serum testosterone levels among the B6-ChrY consomic strains. Serum testosterone was measured in 8-week-old B6-ChrY consomic male mice and compared with wild-type B6 by EIA. X-axis labels indicate the mouse strain donating ChrY to B6. Only B6-ChrYRF mice exhibited a significant elevation in testosterone compared with B6. Significance of observed differences was determined by one-way ANOVA, followed by a Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. n = 5 mice per strain. ***P ≤ 0.001.

Our data confirm that natural ChrY polymorphism results in differences in the percentage of basal iNKT cells in mice. However, it is important to note that further investigation is required to determine whether CVB3 infection itself changes the distribution of iNKT cells among the B6-ChrY consomic strains. Nonetheless, as the strain distribution pattern (SDP) for mortality is discordant with the SDP for iNKT cells in naïve B6-ChrY consomic strains, these data suggest that YCvb3 is not YNkt, and that the variations in basal iNKT cell numbers do not contribute to the phenotypic differences in CVB3-induced mortality. Moreover, these data indicate that the YNkt-129/Pas allele transmitted by male founder mice derived from 129F11/Pas embryonic stem cells is unique, as male mice that inherited the wild-type ChrY129F11/Pas by natural breeding differed markedly in iNKT cell numbers (Figure 3B). A direct comparison of these two ChrYs could in theory lead to the identification of the locus controlling iNKT cell numbers and possibly, as with yaa (Pisitkun et al. 2006; Subramanian et al. 2006), the identification of a unique translocation in ChrYNkt-129/Pas giving rise to a dramatic reduction in iNKT cell numbers compared to naturally occurring YNkt alleles.

Sry allele-dependent variations in prenatal testosterone production do not underlie YCvb3

Sry is a particularly intriguing candidate for YCvb3 because Sry expression by the bipotential cells of the primordial gonad initiates testis differentiation by activating male-specific transcription factors, in particular Sox9, to induce Sertoli cell differentiation. This drives testis formation (Kashimada and Koopman 2010), including differentiation of fetal Leydig cells (Brennan et al. 2003; Clark et al. 2000; Gnessi et al. 2000; Yao et al. 2002), which produce the androgens required for masculinization of the male fetus during embryogenesis (Sriraman et al. 2005). Sertoli cells also contribute to the proper differentiation and function of adult Leydig cells (Loveland and Schlatt 1997; Russell et al. 2001; Yan et al. 2000) responsible for pubertal production of testosterone and sexual maturation (Ge and Hardy 2007). There is increasing evidence that testis determination may not be the only function of Sry, as it is also expressed in the brain, kidney, and adrenal glands of adult males (Ely et al. 2010). The existence of functionally significant Sry polymorphisms is well documented in studies using B6-ChrY consomic strains in which Sry alleles give rise to varying degrees of sex reversal, ranging from normal testis development to permanent sex reversal (Albrecht et al. 2003; Biddle and Nishioka 1988; Eicher and Washburn 1986; Eicher et al. 1982; Nagamine et al. 1987, 1999). Therefore, Sry polymorphisms could lead to differences in neonatal and/or adult testosterone levels, thereby impacting susceptibility to CVB3-induced mortality.

To test our hypothesis, we compared the SDP of Sry polymorphisms with the SDP of CVB3-induced mortality. The B6-ChrY consomic lines can be separated into two categories based on the evolutionary origin of the Mus musculus species donating ChrY, including musculus and domesticus. Within the domesticus ChrY consomic lines, two groups of mice exist based on their Sry alleles (Table 1) (Washburn et al. 2001). Domesticus Group A is defined as having Sry alleles with 13 CAG repeats in glutamine repeat cluster 3, which results in sex reversal when inherited by B6 mice heterozygous for the Chr17 TOrleans mutation. Mice within this group have reduced Sry expression in the fetal gonad, which is insufficient for normal development. Domesticus Group B is defined as having Sry alleles with 12 CAG repeats in glutamine repeat cluster 3 and a 10 bp deletion in the 5′ UTR that allows for normal development in B6 mice heterozygous for the TOrleans mutation and normal Sry expression levels in the fetal gonad. However, our analysis of the consomic lines revealed that the SDP for CVB3-induced mortality is discordant with the SDP for Sry alleles (Table 1). These data suggest that the Sry allelic variations having the potential to influence testis development and neonatal testosterone production are not likely to underlie YCvb3.

Table 1

| Musculus ChrY | Domesticus ChrY Group A | Domesticus ChrY Group B |

|---|---|---|

| B6 | a B6-ChrYAKR | b B6-ChrYBUB |

| b B6-ChrY129S1 | b B6-ChrYLEWES | b B6-ChrYSJL |

| a B6-ChrYA/J | a B6-ChrYMA | c B6-ChrYST |

| a B6-ChrYRF | b B6-ChrYSWR | |

| a B6-ChrYWSB | ||

| c B6-ChrYMET |

Variation in adult testosterone levels do not account for ChrY regulation of CVB3-induced mortality

Testosterone clearly plays a critical role in the sexual dimorphism in susceptibility to myocarditis by regulating both viral infectivity and differences in innate and adaptive antiviral immune responses. Therefore, we hypothesized that allelic differences in Sry could also in theory influence the production of postpubertal testosterone in CVB3-infected B6-ChrY consomic mice and lead to differences in mortality among the strains. To test this, blood was collected from male mice at eight weeks of age that were bled between 1 and 3 pm to minimize daily fluctuations in testosterone production. Serum testosterone levels were measured using a testosterone EIA kit (File S1). First, adult testosterone levels did not correlate with Sry alleles, suggesting that Sry allelic variations with the potential to influence testis development do not influence adult testosterone levels (Table 1). Only B6-ChrYRF consomic mice exhibited significant differences in adult testosterone levels compared with B6 Figure 4. Thus, elevated testosterone levels may contribute to increased mortality in B6-ChrYRF, but an increase in adult testosterone levels does not explain the enhanced mortality seen in the other 11 B6-ChrY consomic strains. However, whether ChrY influences other steroid hormones and whether ChrY influences virus receptor expression in the heart independently of testosterone levels remain under consideration.

Our data suggest that Sry polymorphisms neither underlie YCvb3 nor control adult serum testosterone levels. Nevertheless, dependence of CVB3-induced mortality on both testosterone and ChrY polymorphism makes YCmc, a ChrY polymorphism that impacts the sensitivity of cardiomyocytes to the hypertrophic effects of postpubertal testosterone, a strong candidate for YCvb3. Llamas et al. (2007) showed that the surface area of cardiomyocytes from B6 mice is significantly larger than cardiomyocytes from B6-ChrYA/J mice. Orchiectomy of B6 and B6-ChrYA/J consomic mice resulted in a decrease in the size of B6 cardiomyocytes but not in the size of B6-ChrYA/J cardiomyocytes (Llamas et al. 2007, 2009). Furthermore, treatment of orchiectomized mice with exogenous testosterone effectively increased the size of cardiomyocytes in B6 mice but not in B6-ChrYA/J mice (Llamas et al. 2009). Therefore, these differences are not due to inherent changes in testosterone production between the strains but, rather, due to the insensitivity of cardiomyocytes from B6-ChrYA/J mice to the hypertrophic effects of postpubertal testosterone, which is a direct consequence of YCmc. This same effect may contribute to the differences in CVB3-induced mortality among the B6-ChrY consomic lines, and it is being actively investigated.

The location of YCvb3, as well as YNkt and YCmc, with respect to the pseudoautosomal (PAR) and nonpseudoautosomal (NPAR) regions of ChrY remains to be determined. However, the fact that PAR is free to recombine with the B6 background and that all of the ChrY mice have been backcrossed over 10 generations to B6 excludes Sts (steroid sulfatase), the only full-length functional gene within the murine PAR, as a candidate (Park et al. 2005). Therefore, YCvb3 presumably resides within the NPAR where there are 9 pseudogenes (Gm2098, Gm4017, Gm8498, Gm8502, Gm8506, Gm8510, Gm2303, Gm2316, and Gm2357), 8 validated protein-coding genes of unknown function (Gm2191, Gm6026, Gm16501, Gm4064, Gm10256, Gm10352, Gm3376, and Gm3395), and 13 known genes [Ddx3y (DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 3, Y-linked); Eif2s3y (eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2, subunit 3, structural gene Y-linked); Kdm5d (lysine (K)-specific demethylase 5D histocompatibility Y); Rbmy1a1 (RNA binding motif protein, Y chromosome, family 1, member A1); Sly (Sycp3 like Y-linked); Sry (sex-determining region of ChrY); Ssty1 (spermiogenesis-specific transcript on the Y 1); Ssty2 (spermiogenesis-specific transcript on the Y 2); Ube1y1 (ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1, ChrY 1); Usp9y (ubiquitin-specific peptidase 9, Y chromosome); Uty (ubiquitously transcribed tetratricopeptide repeat gene, Y chromosome); Zfy1 (zinc finger protein 1, Y linked); and Zfy2 (zinc finger protein 2, Y linked)].

Our data suggest that the functional Sry alleles influencing testis differentiation are unlikely to be responsible for YCvb3 or YNkt. Moreover, a comparison of the available ChrY sequence data (phenome.jax.org) indicates that there are no single nucleotide polymorphisms within the NPAR candidates that uniquely distinguish the YCvb3 alleles influencing mortality (Table 1). Thus, it is important to also consider the impact that ChrY structural polymorphism may have on phenotypic differences among the B6-ChrY consomic strains. Structural polymorphism can arise through variations in the number of repeat sequences, inverted sequences, and retroelements composing heterochromatin. As seen in Drosophila, Y-linked heterochromatin can influence the epigenetic regulation of autosomal and ChrX gene expression through its interaction with chromatin, thereby epigenetically regulating differences in males (Lemos et al. 2008, 2010). Therefore, the differences in CVB3-induced mortality observed among the consomic strains may be the consequence of epigenetic regulation by ChrY resulting from heterochromatic polymorphism.

Delineating the underlying biological components regulating sex differences is critical to appropriate therapeutic treatment of sexually dimorphic diseases. Increasing evidence indicates that ChrY polymorphism can impact biological functions unrelated to male reproduction, such as autoimmune and cardiovascular diseases and hypertension, but the mechanisms behind these alternative functions remain unknown (Llamas et al. 2007, 2009; Teuscher et al. 2006). Fortunately, the use of ChrY consomic strains of mice presents the opportunity to reveal the polymorphism underlying these unconventional biological functions. Clearly, defining the genetic basis of ChrY functional polymorphism is of considerable importance to human health and disease, particularly in those settings where a male-specific sexual dimorphism dominates.

Acknowledgments

We thank Meena Subramanian for technical assistance. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants NS061014 (C.T.), NS069628 (C.T.), AI45666 (C.T. and S.A.H.), HL108371 (S.A.H.), and AI046709 (L.B.). L.T. was supported by NIH grant 3R01AI046709, a research supplement to promote diversity in health-related research.

Literature Cited

- Albrecht K. H., Young M., Washburn L. L., Eicher E. M., 2003.

Sry expression level and protein isoform differences play a role in abnormal testis development in C57BL/6J mice carrying certain Sry alleles.

Genetics

164: 277–288 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Sry expression level and protein isoform differences play a role in abnormal testis development in C57BL/6J mice carrying certain Sry alleles.

Genetics

164: 277–288 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Biddle F. G., Nishioka Y., 1988.

Assays of testis development in the mouse distinguish three classes of domesticus-type Y chromosome. Genome

30: 870–878 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Assays of testis development in the mouse distinguish three classes of domesticus-type Y chromosome. Genome

30: 870–878 [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Brennan J., Tilmann C., Capel B., 2003.

Pdgfr-alpha mediates testis cord organization and fetal Leydig cell development in the XY gonad.

Genes Dev.

17: 800–810 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Pdgfr-alpha mediates testis cord organization and fetal Leydig cell development in the XY gonad.

Genes Dev.

17: 800–810 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Clark A. M., Garland K. K., Russell L. D., 2000.

Desert hedgehog (Dhh) gene is required in the mouse testis for formation of adult-type Leydig cells and normal development of peritubular cells and seminiferous tubules.

Biol. Reprod.

63: 1825–1838 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Desert hedgehog (Dhh) gene is required in the mouse testis for formation of adult-type Leydig cells and normal development of peritubular cells and seminiferous tubules.

Biol. Reprod.

63: 1825–1838 [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Eicher E. M., Washburn L. L., 1986.

Genetic control of primary sex determination in mice.

Annu. Rev. Genet.

20: 327–360 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Genetic control of primary sex determination in mice.

Annu. Rev. Genet.

20: 327–360 [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Eicher E. M., Washburn L. L., Whitney J. B., 3rd, Morrow K. E., 1982.

Mus poschiavinus Y chromosome in the C57BL/6J murine genome causes sex reversal.

Science

217: 535–537 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Mus poschiavinus Y chromosome in the C57BL/6J murine genome causes sex reversal.

Science

217: 535–537 [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Ely D., Underwood A., Dunphy G., Boehme S., Turner M., et al. , 2010.

Review of the Y chromosome, Sry and hypertension.

Steroids

75: 747–753 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Review of the Y chromosome, Sry and hypertension.

Steroids

75: 747–753 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Frisancho-Kiss S., Coronado M. J., Frisancho J. A., Lau V. M., Rose N. R., et al. , 2009.

Gonadectomy of male BALB/c mice increases Tim-3(+) alternatively activated M2 macrophages, Tim-3(+) T cells, Th2 cells and Treg in the heart during acute coxsackievirus-induced myocarditis.

Brain Behav. Immun.

23: 649–657 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Gonadectomy of male BALB/c mice increases Tim-3(+) alternatively activated M2 macrophages, Tim-3(+) T cells, Th2 cells and Treg in the heart during acute coxsackievirus-induced myocarditis.

Brain Behav. Immun.

23: 649–657 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Gauntt C. J., Trousdale M. D., LaBadie D. R., Paque R. E., Nealon T., 1979.

Properties of coxsackievirus B3 variants which are amyocarditic or myocarditic for mice.

J. Med. Virol.

3: 207–220 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Properties of coxsackievirus B3 variants which are amyocarditic or myocarditic for mice.

J. Med. Virol.

3: 207–220 [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Ge R., Hardy M. P., 2007.

Regulation of Leydig cells during pubertal development, pp. 55–70

The Leydig Cell in Health and Disease, edited by

Payne A. H., Hardy M. P.

Humana Press, Totowa, NJ [Google Scholar]

Regulation of Leydig cells during pubertal development, pp. 55–70

The Leydig Cell in Health and Disease, edited by

Payne A. H., Hardy M. P.

Humana Press, Totowa, NJ [Google Scholar] - Gnessi L., Basciani S., Mariani S., Arizzi M., Spera G., et al. , 2000.

Leydig cell loss and spermatogenic arrest in platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-A-deficient mice.

J. Cell Biol.

149: 1019–1026 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Leydig cell loss and spermatogenic arrest in platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-A-deficient mice.

J. Cell Biol.

149: 1019–1026 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Grodums E. I., Dempster G., 1959a

The age factor in experimental Coxsackie B-3 infection.

Can. J. Microbiol.

5: 595–604 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

The age factor in experimental Coxsackie B-3 infection.

Can. J. Microbiol.

5: 595–604 [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Grodums E. I., Dempster G., 1959b

Myocarditis in experimental Coxsackie B-3 infection.

Can. J. Microbiol.

5: 605–615 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Myocarditis in experimental Coxsackie B-3 infection.

Can. J. Microbiol.

5: 605–615 [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Huber S., Pfaeffle B., 1994.

Differential Th1 and Th2 cell responses in male and female BALB/c mice infected with Coxsackievirus Group B Type 3.

J. Virol.

68: 5126–5132 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Differential Th1 and Th2 cell responses in male and female BALB/c mice infected with Coxsackievirus Group B Type 3.

J. Virol.

68: 5126–5132 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Huber S. A., Job L. P., Auld K. R., 1982.

Influence of sex hormones on Coxsackie B-3 virus infection in Balb/c mice.

Cell. Immunol.

67: 173–179 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Influence of sex hormones on Coxsackie B-3 virus infection in Balb/c mice.

Cell. Immunol.

67: 173–179 [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Huber S. A., Graveline D., Born W. K., O'Brien R. L., 2001.

Cytokine production by Vgamma(+)-T-cell subsets is an important factor determining CD4(+)-Th-cell phenotype and susceptibility of BALB/c mice to coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis.

J. Virol.

75: 5860–5869 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Cytokine production by Vgamma(+)-T-cell subsets is an important factor determining CD4(+)-Th-cell phenotype and susceptibility of BALB/c mice to coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis.

J. Virol.

75: 5860–5869 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Kashimada K., Koopman P., 2010.

Sry: the master switch in mammalian sex determination.

Development

137: 3921–3930 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Sry: the master switch in mammalian sex determination.

Development

137: 3921–3930 [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Knowlton K. U., Jeon E. S., Berkley N., Wessely R., Huber S., 1996.

A mutation in the puff region of VP2 attenuates the myocarditis phenotype of an infectious cDNA of the Woddruff variant of Coxsackievirus B3.

J. Immunol.

149: 2715–2721 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

A mutation in the puff region of VP2 attenuates the myocarditis phenotype of an infectious cDNA of the Woddruff variant of Coxsackievirus B3.

J. Immunol.

149: 2715–2721 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Lemos B., Araripe L. O., Hartl D. L., 2008.

Polymorphic Y chromosomes harbor cryptic variation with manifold functional consequences.

Science

319: 91–93 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Polymorphic Y chromosomes harbor cryptic variation with manifold functional consequences.

Science

319: 91–93 [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Lemos B., Branco A. T., Hartl D. L., 2010.

Epigenetic effects of polymorphic Y chromosomes modulate chromatin components, immune response, and sexual conflict.

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA

107: 15826–15831 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Epigenetic effects of polymorphic Y chromosomes modulate chromatin components, immune response, and sexual conflict.

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA

107: 15826–15831 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Liu W., Huber S. A., 2011.

Cross-talk between cd1d-restricted nkt cells and gammadelta cells in t regulatory cell response.

Virol. J.

8: 32. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Cross-talk between cd1d-restricted nkt cells and gammadelta cells in t regulatory cell response.

Virol. J.

8: 32. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Llamas B., Belanger S., Picard S., Deschepper C. F., 2007.

Cardiac mass and cardiomyocyte size are governed by different genetic loci on either autosomes or chromosome Y in recombinant inbred mice.

Physiol. Genomics

31: 176–182 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Cardiac mass and cardiomyocyte size are governed by different genetic loci on either autosomes or chromosome Y in recombinant inbred mice.

Physiol. Genomics

31: 176–182 [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Llamas B., Verdugo R. A., Churchill G. A., Deschepper C. F., 2009.

Chromosome Y variants from different inbred mouse strains are linked to differences in the morphologic and molecular responses of cardiac cells to postpubertal testosterone.

BMC Genomics

10: 150. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Chromosome Y variants from different inbred mouse strains are linked to differences in the morphologic and molecular responses of cardiac cells to postpubertal testosterone.

BMC Genomics

10: 150. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Loveland K. L., Schlatt S., 1997.

Stem cell factor and c-kit in the mammalian testis: lessons originating from Mother Nature's gene knockouts.

J. Endocrinol.

153: 337–344 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Stem cell factor and c-kit in the mammalian testis: lessons originating from Mother Nature's gene knockouts.

J. Endocrinol.

153: 337–344 [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Lyden D., Olszewski J., Huber S., 1987a

Variation in susceptibility of Balb/c mice to coxsackievirus group B type 3-induced myocarditis with age.

Cell. Immunol.

105: 332–339 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Variation in susceptibility of Balb/c mice to coxsackievirus group B type 3-induced myocarditis with age.

Cell. Immunol.

105: 332–339 [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Lyden D. C., Olszewski J., Feran M., Job L. P., Huber S. A., 1987b

Coxsackievirus B-3-induced myocarditis. Effect of sex steroids on viremia and infectivity of cardiocytes.

Am. J. Pathol.

126: 432–438 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Coxsackievirus B-3-induced myocarditis. Effect of sex steroids on viremia and infectivity of cardiocytes.

Am. J. Pathol.

126: 432–438 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Matsumori A., Kawai C., 1980.

Coxsackie virus B3 perimyocarditis in BALB/c mice: experimental model of chronic perimyocarditis in the right ventricle.

J. Pathol.

131: 97–106 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Coxsackie virus B3 perimyocarditis in BALB/c mice: experimental model of chronic perimyocarditis in the right ventricle.

J. Pathol.

131: 97–106 [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Nagamine C. M., Michot J. L., Roberts C., Guenet J. L., Bishop C. E., 1987.

Linkage of the murine steroid sulfatase locus, Sts, to sex reversed, Sxr: a genetic and molecular analysis.

Nucleic Acids Res.

15: 9227–9238 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Linkage of the murine steroid sulfatase locus, Sts, to sex reversed, Sxr: a genetic and molecular analysis.

Nucleic Acids Res.

15: 9227–9238 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Nagamine C. M., Morohashi K., Carlisle C., Chang D. K., 1999.

Sex reversal caused by Mus musculus domesticus Y chromosomes linked to variant expression of the testis-determining gene Sry.

Dev. Biol.

216: 182–194 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Sex reversal caused by Mus musculus domesticus Y chromosomes linked to variant expression of the testis-determining gene Sry.

Dev. Biol.

216: 182–194 [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Park S. H., Shin Y. K., Suh Y. H., Park W. S., Ban Y. L., et al. , 2005.

Rapid divergency of rodent CD99 orthologs: implications for the evolution of the pseudoautosomal region.

Gene

353: 177–188 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Rapid divergency of rodent CD99 orthologs: implications for the evolution of the pseudoautosomal region.

Gene

353: 177–188 [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Pisitkun P., Deane J. A., Difilippantonio M. J., Tarasenko T., Satterthwaite A. B., et al. , 2006.

Autoreactive B cell responses to RNA-related antigens due to TLR7 gene duplication.

Science

312: 1669–1672 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Autoreactive B cell responses to RNA-related antigens due to TLR7 gene duplication.

Science

312: 1669–1672 [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Reyes M. P., Lerner A. M., 1985.

Coxsackievirus myocarditis—with special reference to acute and chronic effects.

Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis.

27: 373–394 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Coxsackievirus myocarditis—with special reference to acute and chronic effects.

Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis.

27: 373–394 [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Russell L. D., Warren J., Debeljuk L., Richardson L. L., Mahar P. L., et al. , 2001.

Spermatogenesis in Bclw-deficient mice.

Biol. Reprod.

65: 318–332 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Spermatogenesis in Bclw-deficient mice.

Biol. Reprod.

65: 318–332 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Sriraman V., Anbalagan M., Rao A. J., 2005.

Hormonal regulation of Leydig cell proliferation and differentiation in rodent testis: a dynamic interplay between gonadotrophins and testicular factors.

Reprod. Biomed. Online

11: 507–518 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Hormonal regulation of Leydig cell proliferation and differentiation in rodent testis: a dynamic interplay between gonadotrophins and testicular factors.

Reprod. Biomed. Online

11: 507–518 [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Subramanian S., Tus K., Li Q. Z., Wang A., Tian X. H., et al. , 2006.

A Tlr7 translocation accelerates systemic autoimmunity in murine lupus.

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA

103: 9970–9975 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

A Tlr7 translocation accelerates systemic autoimmunity in murine lupus.

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA

103: 9970–9975 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Teuscher C., Noubade R., Spach K., McElvany B., Bunn J. Y., et al. , 2006.

Evidence that the Y chromosome influences autoimmune disease in male and female mice.

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA

103: 8024–8029 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Evidence that the Y chromosome influences autoimmune disease in male and female mice.

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA

103: 8024–8029 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Washburn L. L., Albrecht K. H., Eicher E. M., 2001.

C57BL/6J-T-associated sex reversal in mice is caused by reduced expression of a Mus domesticus Sry allele.

Genetics

158: 1675–1681 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

C57BL/6J-T-associated sex reversal in mice is caused by reduced expression of a Mus domesticus Sry allele.

Genetics

158: 1675–1681 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Wesley J. D., Tessmer M. S., Paget C., Trottein F., Brossay L., 2007.

A Y chromosome-linked factor impairs NK T development.

J. Immunol.

179: 3480–3487 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

A Y chromosome-linked factor impairs NK T development.

J. Immunol.

179: 3480–3487 [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Wong C. Y., Woodruff J. J., Woodruff J. F., 1977.

Generation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes during coxsackievirus B-3 infection. III. Role of sex.

J. Immunol.

119: 591–597 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Generation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes during coxsackievirus B-3 infection. III. Role of sex.

J. Immunol.

119: 591–597 [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Woodruff J. F., 1980.

Viral myocarditis. A review.

Am. J. Pathol.

101: 425–484 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Viral myocarditis. A review.

Am. J. Pathol.

101: 425–484 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Wu C. Y., Feng Y., Qian G. C., Wu J. H., Luo J., et al. , 2010.

alpha-Galactosylceramide protects mice from lethal Coxsackievirus B3 infection and subsequent myocarditis.

Clin. Exp. Immunol.

162: 178–187 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

alpha-Galactosylceramide protects mice from lethal Coxsackievirus B3 infection and subsequent myocarditis.

Clin. Exp. Immunol.

162: 178–187 [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Yan W., Kero J., Huhtaniemi I., Toppari J., 2000.

Stem cell factor functions as a survival factor for mature Leydig cells and a growth factor for precursor Leydig cells after ethylene dimethane sulfonate treatment: implication of a role of the stem cell factor/c-Kit system in Leydig cell development.

Dev. Biol.

227: 169–182 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Stem cell factor functions as a survival factor for mature Leydig cells and a growth factor for precursor Leydig cells after ethylene dimethane sulfonate treatment: implication of a role of the stem cell factor/c-Kit system in Leydig cell development.

Dev. Biol.

227: 169–182 [Abstract] [Google Scholar] - Yao H. H., Whoriskey W., Capel B., 2002.

Desert Hedgehog/Patched 1 signaling specifies fetal Leydig cell fate in testis organogenesis.

Genes Dev.

16: 1433–1440 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Desert Hedgehog/Patched 1 signaling specifies fetal Leydig cell fate in testis organogenesis.

Genes Dev.

16: 1433–1440 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Articles from G3: Genes | Genomes | Genetics are provided here courtesy of Oxford University Press

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1534/g3.111.001610

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://academic.oup.com/g3journal/article-pdf/2/1/115/37066959/g3journal0115.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/138301825

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1534/g3.111.001610

Article citations

Sex Differences in Expression of Pro-Inflammatory Markers and miRNAs in a Mouse Model of CVB3 Myocarditis.

Int J Mol Sci, 25(17):9666, 06 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39273613 | PMCID: PMC11395254

XX sex chromosome complement modulates immune responses to heat-killed Streptococcus pneumoniae immunization in a microbiome-dependent manner.

Biol Sex Differ, 15(1):21, 14 Mar 2024

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 38486287 | PMCID: PMC10938708

Myocarditis in Athletes: Risk Factors and Relationship with Strenuous Exercise.

Sports Med, 54(3):607-621, 11 Dec 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38079080

Review

Impact of Sex and Age on mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine-Related Side Effects in Japan.

Microbiol Spectr, 10(6):e0130922, 31 Oct 2022

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 36314943 | PMCID: PMC9769945

Sex and gender differences in myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy: An update.

Front Cardiovasc Med, 10:1129348, 02 Mar 2023

Cited by: 28 articles | PMID: 36937911 | PMCID: PMC10017519

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (36) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Genetic variation in chromosome Y regulates susceptibility to influenza A virus infection.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 114(13):3491-3496, 27 Feb 2017

Cited by: 35 articles | PMID: 28242695 | PMCID: PMC5380050

The Y chromosome as a regulatory element shaping immune cell transcriptomes and susceptibility to autoimmune disease.

Genome Res, 23(9):1474-1485, 25 Jun 2013

Cited by: 90 articles | PMID: 23800453 | PMCID: PMC3759723

Sex chromosome complement contributes to sex differences in coxsackievirus B3 but not influenza A virus pathogenesis.

Biol Sex Differ, 2:8, 01 Aug 2011

Cited by: 62 articles | PMID: 21806829 | PMCID: PMC3162877

Chromosome Y genetic variants: impact in animal models and on human disease.

Physiol Genomics, 47(11):525-537, 18 Aug 2015

Cited by: 24 articles | PMID: 26286457 | PMCID: PMC4629007

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NHLBI NIH HHS (2)

Grant ID: R01 HL108371

Grant ID: R01 HL108371-02

NIAID NIH HHS (5)

Grant ID: R21 AI046709

Grant ID: R01 AI046709-10

Grant ID: P01 AI045666

Grant ID: R01 AI046709

Grant ID: P01 AI045666-11

NINDS NIH HHS (2)

Grant ID: R01 NS069628

Grant ID: R01 NS061014