Abstract

Free full text

Effects of Hypoperfusion in Alzheimer’s Disease

Abstract

The role of hypoperfusion in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a vital component to understanding the pathogenesis of this disease. Disrupted perfusion is not only evident throughout disease manifestation, it is also demonstrated during the pre-clinical phase of AD (i.e., mild cognitive impairment) as well as in cognitively healthy persons at high-risk for developing AD due to family history or genetic factors. Studies have used a variety of imaging modalities (e.g., SPECT, MRI, PET) to investigate AD, but with its recent technological advancements and non-invasive use of blood water as an endogenous tracer, arterial spin labeling (ASL) MRI has become an imaging technique of growing popularity. Through numerous ASL studies, it is now known that AD is associated with both global and regional cerebral hypoperfusion and that there is considerable overlap between the regions implicated in the disease state (consistently reported in precuneus/posterior cingulate and lateral parietal cortex) and those implicated in disease risk. Debate exists as to whether decreased blood flow in AD is a cause or consequence of the disease. Nonetheless, hypoperfusion in AD is associated with both structural and functional changes in the brain and offers a promising putative biomarker that could potentially identify AD in its pre-clinical state and be used to explore treatments to prevent, or at least slow, the progression of the disease. Finally, given that perfusion is a vascular phenomenon, we provide insights from a vascular lesion model (i.e., stroke) and illustrate the influence of disrupted perfusion on brain structure and function and, ultimately, cognition in AD.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by gradual onset, progressive deterioration, and decreased regional cerebral blood flow (CBF) [1]. Indeed, vascular factors play a critical role in the pathogenesis of AD [2–3], and it is currently debated whether decreased CBF is a cause or a consequence of AD [1]. Perfusion deficiencies are present from the very early pre-clinical phases of AD (i.e., during mild cognitive impairment (MCI)) and persist well into the latest stages of the disease, demonstrating a pattern of increased hypoperfusion with disease development. This phenomenon, over time, yields catastrophic consequences on brain structure, function, and cognition, leaving the patient irreversibly impaired, especially in their memory faculties.

Although there is no cure for this devastating illness, identification of pre-symptomatic AD is necessary to explore treatments (pharmacological and non-pharmacological) that could potentially prevent or at least slow the progression of the disease. Thus, much research has been focused on identifying biomarkers associated with AD manifestation as well as biomarkers in individuals at high risk for developing AD. Among the most promising of these putative biomarkers are the well-documented abnormalities in CBF associated with AD and its development.

Investigating perfusion in AD, however, is no straightforward task, as decreased CBF is only one of many neuropathological characteristics associated with AD. Indeed, the co-occurrence of hypoperfusion, arterial plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, vascular amyloid deposits, atrophy, and stenosis complicate the investigation of any one neuropathological feature, and it becomes increasingly difficult to distinguish cause from consequence. Thus, in order to better understand the effects of perfusion disruption in AD, a vascular lesion model such as stroke that examines the simplest form of perfusion alteration can be examined in order to gain further insight.

The following review investigates the role of perfusion in the development of AD. After a brief review of the genetic and vascular risk factors associated with AD, we discuss 1) imaging methods used to measure perfusion, 2) the brain regions most frequently disrupted by hypoperfusion in both pre-clinical and progressive AD, 3) the effects of hypoperfusion on the structure and function of the brain in AD, and 4) the role of disrupted perfusion in aging and stroke and its relation to AD.

Vascular Risk Factors

The prevalence of late-onset AD, which accounts for approximately 97% of AD cases, is highly associated with the presence of the ε4 allele of the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene on chromosome 19. The presence of one copy of the ε4 allele, which is carried by about half of all patients with dementia [4], is reported to increase the likelihood of developing AD by fourfold while two copies of the ε4 allele may increase risk by ninefold [5]. This genetic factor (APOE4), however, is neither necessary nor sufficient to cause AD, and so it remains of critical importance to identify biomarkers associated with developing AD in high-risk groups.

Vascular factors are repeatedly implicated in the risk for developing AD [1]. Factors such as ischemic stroke, atherosclerosis, hypertension, diabetes, and cardiac disease have been reported to result in cerebrovascular disease and trigger AD pathology in older adults [6–9]. Hypercholesterolemia in midlife also can lead to AD and has been targeted as a potentially modifiable risk factor [10]. Animal studies suggest that amyloid-β deposition in the brain, a hallmark characteristic of AD, is stimulated by hypercholesterolemia [11] and may be modified with the use of lipid-lowering agents, such as statins [12]. A recent study in humans showed that simvastatin improved cognition in asymptomatic middle-aged adults with a parental history of AD without significantly changing CSF Aβ42 or total tau levels [13].

The vascular risk factors associated with AD, however, also play a fundamental role in the development of vascular dementia (VaD), which by current diagnostic criteria, is differentiated from AD by its vascular pathology and its abrupt clinical onset [1]. The diagnostic mutual exclusivity of these two dementias is further equivocated by evidence from epidemiological, neuropathological, clinical, pharmacological, and functional studies which report considerable overlap in the risk factors and pathological changes associated with AD and VaD [1]. In this light, recent AD studies have focused more on brain circulation abnormalities and have collectively found that such vascular factors, including hypoperfusion, are more commonly associated with AD than was previously thought [14].

Measuring Perfusion

In AD, perfusion (Cerebral blood flow, Cerebral blood volume (CBV)) has been measured using a number of different imaging modalities including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), CT, single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), and regional cerebral metabolism using 2-deoxy-2-[F-18]fluoro-D-glucose (FDG-PET). Perfusion in AD has also been investigated using dynamic perfusion computed tomography and transcranial Doppler, but the incidence of such studies is far lower [14]. For the past two decades, SPECT and FDG-PET have served as the mainstream imaging techniques for perfusion and metabolism studies in AD, respectively [14]. SPECT, despite its relatively low spatial resolution (~1cm), lends to a large number of applications [15–17], while FDG-PET, with higher sensitivity and spatial resolution than SPECT, is better able to measure regional cerebral metabolism in low perfusion areas [14]. These techniques, however, require the use of exogenous radioactive tracers and are more expensive than the more recently developed perfusion-weighted MRI (PW-MRI) techniques. PW-MRI, as an alternative to nuclear imaging techniques, offers the benefits of 1) economic efficiency (PET may require a cyclotron in proximity which is expensive to maintain), 2) accessibility (most hospitals now have at least one MRI system used for clinical practice but rarely have a cyclotron), and 3) higher spatial accuracy (MRI systems have a spatial resolution of up to 0.1 mm while PET systems are only capable of 5-mm resolution). Indeed, PW-MRI is a powerful and promising brain imaging technique and is currently being used by many researchers investigating perfusion in AD.

PW-MRI techniques can be divided into two categories based on the type of contrast agent used. Techniques that use an exogenous contrast tracer (such as dynamic contrast enhancement imaging and dynamic susceptibility contrast [DSC]) fall into the dynamic perfusion imaging subcategory, and techniques that use an endogenous contrast tracer fall into the arterial spin labeling (ASL) subcategory [14]. Currently, the AD perfusion literature is dominated by studies using DSC MRI [14], but many researchers are now migrating towards the use of ASL MRI because it is completely non-invasive and poses less risk for the patient. ASL measures CBF directly by using magnetically-labeled arterial blood water as an endogenous tracer [18]. In addition, ASL can be used to investigate blood flow associated with task performance by using a subtractive method similar to that used in blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) functional MRI (fMRI) studies. ASL, though equal in sensitivity as the BOLD signal for detecting task-induced changes in local brain function, provides more quantitative information and has been shown to be more robust than BOLD-fMRI with reduced intra- and inter-subject variability [19–20]. ASL is further divided into sub-classes based on the labeling method (continuous, pulsed, or velocity-dependent) and can quantify CBF in single slices or for the whole brain. With its many recent advancements, ASL is fast becoming a popular choice for AD researchers and is thus the modality of focus for the current review.

Arterial Spin Labeling

Numerous studies have used ASL perfusion MRI to investigate CBF in AD, MCI, and in individuals at high-risk for developing AD, i.e., those with a parental history of AD or with at least one copy of APOE4. While individuals with AD demonstrate a global decrease in blood flow (averaged 40%) compared to healthy controls [21], CBF reduction may be specific to certain regions of the brain. Indeed, research has shown that individuals with AD consistently demonstrate reduced CBF in regions of the precuneus and/or posterior cingulate and frequently in lateral parietal cortex [see 18 for a review]. Other regions associated with decreased CBF in AD compared to healthy controls include regions of the temporo-occipital and parieto-occipital association cortices [22] as well as bilateral inferior parietal regions [23], hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus [21], and regions in the prefrontal cortex [24] including bilateral superior and middle frontal gyri [23]. Even in studies which include an atrophy correction for gray matter loss, individuals with AD persist at demonstrating reduced CBF in the right inferior parietal lobe extending into the bilateral posterior cingulate gyri, bilateral middle frontal gyri [23], posterior cingulate extending into the precuneus, inferior parietal cortex, left inferior lateral frontal and orbitofrontal cortex [25]. Also, perfusion measures have been shown to correlate with dementia severity in the parieto-occipital region [as measured by a subset of the Blessed Dementia Scale; 22] and parietal cortex along with the precuneus/posterior cingulate [as measured by the Mini-Mental State Examination; 24].

Interestingly, some studies report elevated blood flow in AD compared to healthy controls. Individuals with AD have been reported to demonstrate hyperperfusion, even after atrophy correction, in hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus, temporal pole, superior temporal gyrus [26] and anterior cingulate [25–26]. Hyperperfusion in the prefrontal cortex may serve as a compensation mechanism, especially in the early stages of disease [14]. As for hyperperfusion in the hippocampal regions, it should be noted that increased blood flow to this region is in contrast to the previously discussed hypoperfusion [see 21 above]. Perhaps this discrepancy is attributable to differences in patient demographics as the study reporting hyperperfusion investigated individuals with AD of unspecified severity and a mean age of 75.6±9.2 yrs [26] whereas the study reporting hypoperfusion investigated individuals with mild AD and a mean age 70.7±8.7 yrs [21].

Studies of patients with MCI, a condition of memory impairment considered to be the clinical transition stage between normal aging and dementia [27–28], provide insight into the prodromal phases of AD. Investigations of brain perfusion in individuals with MCI show that this group, in comparison to a healthy control group, demonstrates a reduction of CBF in the posterior cingulate with extension to the medial precuneus [atrophy corrected CBF; 25] as well as in right inferior parietal lobe (IPL) [23]. In the study by Johnson et al. [23], which compared individuals with AD and MCI to healthy controls, decreased perfusion in IPL was observed in both the AD and MCI groups but was more significantly reduced in the AD group. Compared to the MCI group, the AD group also demonstrated greater hypoperfusion in bilateral precuneus/posterior cingulate and bilateral inferior parietal lobe [23].

Hyperperfusion of certain brain regions has also been reported in MCI and other high-risk groups. MCI has been associated with increased blood flow in left hippocampus, right amygdala, and right basal ganglia compared to healthy controls [25]. Non-symptomatic high-risk groups also demonstrate hyperperfusion in the hippocampus; middle aged (average 58.5 years) individuals with a parental history of AD and at least one copy of APOE4 showed an approximately 25% elevated blood flow in the hippocampus compared to non-high-risk subjects [29].

Recent studies suggest that MCI may be a clinically heterogeneous syndrome [30]. Chao et al. [31] examined this idea by investigating CBF differences in two groups of single-domain MCI patients - those with isolated memory impairments (amnestic MCI) and those with isolated executive dysfunction impairments (dysexecutive MCI). Both groups demonstrated hypoperfusion in posterior cingulate compared to healthy controls, but individuals with dysexecutive MCI had significantly lower perfusion in left middle frontal gyrus, left posterior cingulate, and left precuneus when compared to individuals with amnestic MCI [31]. In another study investigating CBF during rest and during a memory encoding task, amnestic MCI patients demonstrated hypoperfusion in right precuneus and cuneus during the control state which extended to the posterior cingulate during task performance. Interestingly, healthy controls demonstrated a significant increase in perfusion in the parahippocampal gyrus when comparing task to baseline rest, but this increase was not observed in the MCI group. This suggests that individuals with amnestic MCI may lack the dynamic capability to modulate regional CBF in response to task demands [32]. In summary, research consistently demonstrates reduced CBF in posterior cingulate in MCI which could be a promising region for early detection [18].

Perfusion and Structural Changes

The pathway leading to AD genesis is marked not only by CBF deficiency but also by structural changes observed in AD and MCI, which are debated by some to be a consequence of primary hypoperfusion (see [33] or [1] for an extensive review). Numerous studies have utilized voxel-based morphometry (VBM), a fully-automated technique that allows the quantifiable investigation of structures across the whole brain [34], to investigate atrophy in the brains of patients with AD and MCI. Collectively, these studies report numerous regions of cell death that are either specific to the pre-clinical phase (MCI), specific to disease manifestation, or that overlap both groups. Studies of patients with AD report atrophy of the entire hippocampus and regions of the temporal lobe, cingulum, precuneus, insular cortex, caudate nucleus, amygdala, entorhinal cortex, medial thalamus, and frontal cortex [35–39]. Studies of patients with MCI report atrophy of the parahippocampal gyrus and medial temporal lobe [40], entorhinal cortex and cingulum [41], and insula and thalamus [37].

Patients with MCI, especially of the amnestic type, can be divided longitudinally by those who progress to AD and those who do not, and these groups show differential atrophy. Studies show that over time, patients with amnestic MCI who eventually progress to AD demonstrate gray matter loss in the medial and inferior temporal lobes, the temporoparietal neocortex, posterior cingulate, precuneus, anterior cingulate, and frontal lobes compared to amnestic MCI patients who are clinically stable [42]. Atrophy, however, is not exclusive to memory-impaired MCI patients; brain volume changes are also observed in cognitively healthy individuals. Studies report that individuals with a parental history of late-onset AD demonstrate decreased gray matter volume in precuneus, middle frontal, inferior frontal, and superior frontal gyri compared to individuals without a parental history of AD. Also, persons carrying the APOE4 allele have been reported to demonstrate decreased volume in hippocampus and amygdala compared to those without the APOE4 allele [43–44].

Hypoperfusion may also lead to changes in cortical thickness as obtained from structural MRI scans. Cortical thickness measures are significant predictors of evolution to AD for subjects with MCI [45]. Carriers of the APOE4 allele, a demographic with reported decreased glucose metabolism in medial temporal and parietal lobes [46–47], demonstrate accelerated cortical thinning in areas most vulnerable to aging (medial prefrontal and pericentral cortices) as well as in areas associated with AD and amyloid-aggregation (e.g., occipitotemporal and basal temporal cortices) [48]. Also, these carriers demonstrate significantly reduced cortical thickness in the entorhinal cortex when compared to non-carriers [49]. There is some evidence that the APOE4 allele has a stronger effect on cognitive decline in the earlier stages of AD and is less severe in the later stages [50].

Perfusion and Functional Changes

In addition to abnormal perfusion and structural changes, individuals with AD also demonstrate functional changes in the brain. Functional connectivity is the temporal dependence of neuronal activity patterns of anatomically separated brain regions [51–52]. This phenomenon can be investigated using MRI BOLD signal which is collected during rest (i.e., the signal is not driven by task performance). Although resting functional connectivity, or resting fMRI, methodologies are relatively new compared to those developed in task-driven fMRI, research has already yielded significant findings in AD. Because of the network-wide changes demonstrated as a result of local structural changes, AD is considered to be a disconnection syndrome [53]. During rest, patients with AD demonstrate decreased functional connectivity in both the default mode network (DMN) and the dorsal visuo-spatial system. The default mode network describes a set of brain regions that demonstrate decreased activation during task performance [54–57], i.e., these regions demonstrate high BOLD activity and a high degree of intrinsic functional connectivity during rest and are “deactivated” during task- or stimulus-driven activity [58–62]. The regions of the DMN include both medial (anterior and posterior cortical midline regions such as the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, different parts of the anterior cingulate cortex, the posterior cingulate cortex and precuneus) and lateral brain regions (lateral parietal cortex and hippocampus) [59].

Functional connectivity in AD as measured by resting fMRI may vary with severity of symptoms. Zhang et al. [63] investigated resting activity in three separate AD groups – those with mild, moderate, and severe AD. Their results show that all three groups demonstrated dissociated functional connectivity between the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) and a set of other regions including bilateral visual cortices, inferior temporal cortex, hippocampus, and especially medial prefrontal cortex and precuneus/cuneus. Interestingly, the disruption of these various networks involving PCC intensified with increasing severity of AD. It should also be noted that certain regions (extending from left lateralized frontoparietal regions and spreading to bilateral frontoparietal regions) demonstrated increased connectivity to PCC with increasing severity of AD [63].

Perfusion in Aging and Stroke

Aging is the leading risk factor for the development of late-onset AD. Investigation of the normal aging brain and age-related changes in vasculature serves as a fundamental template on which to better understand the pathogenesis of AD and its effect on cognition. Evidence from aging and stroke studies suggest that chronic brain hypoperfusion (CBH) leads to tissue pathology and cognitive impairments that are characteristic of AD.

With normal aging, cerebral vasculature undergoes both structural and functional changes that may act as a catalyst for cerebrovascular diseases and subsequent cognitive deficits. For example, changes in vascular ultrastructure, vascular reactivity, resting cerebral blood flow (rCBF) and oxygen metabolism are all associated with age [64]. There is also evidence that aging, per se, in the absence of other risk factors, promotes thickening and stiffness of the arteries and increases the morbidity and mortality of myocardial infarction and stroke [65–66]. Perfusion studies have shown that in normal aging, uncomplicated by the presence of hypertension, diabetes, arteriosclerosis or dementia, there is evidence for decreased CBF, CBV, cerebral metabolic rate for oxygen (CMRO2), and glucose oxidation without significant change in oxygen extraction or blood brain barrier permeability [e.g., 67]. Also, these changes in CBF and CMRO2 have been found to be largely restricted to discrete brain regions presumed to be associated with cell loss [68].

Studies have documented that CBF decreases with age, either globally or in a region specific manner. In an ASL study, Bertsch et al. demonstrated an association between the age-dependent decline in global rCBF and performance in an attention task [69], but other studies suggest that declines in perfusion may be more region-specific. For example, brain regions critical to higher-cognition, such as the frontal cortex, the medial temporal lobe, and the cingulate gyrus display local age-related decreases in rCBF, even after controlling for partial volume effects [70–71].

In addition to decreasing the volume of blood flow, age-related changes in cerebral vasculature can significantly alter the speed of blood flow during task performance. In a functional transcranial Doppler ultrasound study measuring cerebral blood flow velocities (BFV) in the ACA (anterior cerebral artery) and PCA (posterior cerebral artery), Sorond et al. found differences in BFV in healthy young and old adults during a word stem completion and a visual search task. In the younger subjects, greater activation was observed in the ACA than in the PCA territories during the word task, but older subjects did not show the same pattern. During the visual search task, however, both younger subjects and older subjects showed greater activation in PCA than in the ACA territories [72]. This suggests that blood flow to frontal areas may be altered in some cognitive tasks as part of the aging process.

Neurovascular and physiological changes associated with normal aging are often reflected in behavioral differences between the young and old. Studies show that older adults tend to display a general slowing in processing speed, a reduction in inhibitory control, and a general decline of attentional resources [73–75]. Models of neurocognitive aging based on neuroimaging studies suggest that during task performance, older adults recruit additional brain regions compared to younger adults due to the effects of age on brain integrity and function [76–77].

The relationship between perfusion and cognition in older adults raises the question of whether hyperperfusion can serve as compensatory mechanism against the cognitive decline seen in normal aging. It is known that exercise promotes healthy cognitive aging [78]. Conversely, Mozolic et al. have recently demonstrated that cognitive training increases rCBF in the rostrolateral PFC in older adults, and that this increase in rCBF correlated with the increase in their attention task [79]. Interestingly, models of neurocognitive aging suggest that the PFC is the seat of compensatory recruitment in older adults [76–77] and sometimes in MCI. In an fMRI study in which MCI patients were divided into two groups based on Mattis Dementia Rating Scale scores, higher-cognition MCI patients activated right ventrolateral and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex during verbal memory tasks while lower-cognition MCI patients and control subjects did not [80]. This suggests that PFC compensation is present at the beginning of the MCI continuum but eventually breaks down as the symptoms increase in severity. This is similar to the hypothesis that PFC hyperperfusion is compensatory in early stages of AD [14]. Another interesting connection between perfusion in normal aging and in AD was noted in a study by Lee et al. [81]. In this study, cognitively normal elderly individuals displayed cortical thinning and hypoperfusion, as measured by ASL, in patterns similar to those observed in AD.

Animal studies have shown that reduced CBF over long durations, or chronic brain hypoperfusion (CBH), leads to neurochemical, metabolic, anatomic [e.g., 33, 82, 83–89], and cognitive changes that are very similar to that observed in AD [90]. Aged rats that were subjected to 1–2 weeks of 2-vessel occlusion showed behavioral, physiological and anatomical changes. A significant finding was that the age of the animal together with the severity of CBH determined whether reperfusion could aid the animals to recover the CBF levels that existed prior to vessel occlusion. Based on evidence from rat CBH studies, de la Torre [85] suggests that aging combined with a vascular risk factor can lead to CBH which can, upon falling below a certain threshold (i.e., the critically attained threshold of cerebral hypoperfusion [CATCH]), trigger hemodynamic changes in the brain micro-circulature and impair optimal delivery of glucose and oxygen needed for normal brain cell function. Because glucose and oxygen are the crucial substrates in the production of tissue energy, metabolic energy deficits can trigger an intracellular biochemical cascade that effectively compromises brain cells and eventually leads to metabolic, cognitive and tissue pathology that characterize AD [91–92].

There is strong evidence for hypoperfusion and the occurrence of brain ischemia and infarcts. Patients with severe arterial stenosis, or narrowing of the arteries, often show the presence of microemboli that fail to get washed out on account of reduced blood flow [93]. Hypoperfusion also leads to sub-optimal supply of nutrients to places that may be blocked by the emboli. It has been suggested that the degree of severity of stenosis is accompanied by differential rates of transient ischemic attacks (TIA; an episode of stroke-like symptoms lasting less than 24 hours) and strokes. Stroke patients in the acute and subacute phase show region specific hypoperfusion leading to cognitive deficits [94–96]. There is also evidence that chronic stroke patients show hypoperfusion associated with cognitive deficits although without accompanying structural infarcts as indicated by T1- or T2-weighted scans [97–99]. This suggests that functional areas receive enough blood supply so that tissue viability is sustained but not enough to support cognitive or neurological functioning [100]. Twenty to twenty-five percent of ischemic stroke patients go on to develop post-stroke dementia, especially in patients who are 55 years or older [101]. Patients with post-stroke dementia show changes in cerebral blood flow, white matter hyperintensities, and cortical thinning associated with varying degrees of cognitive impairments.

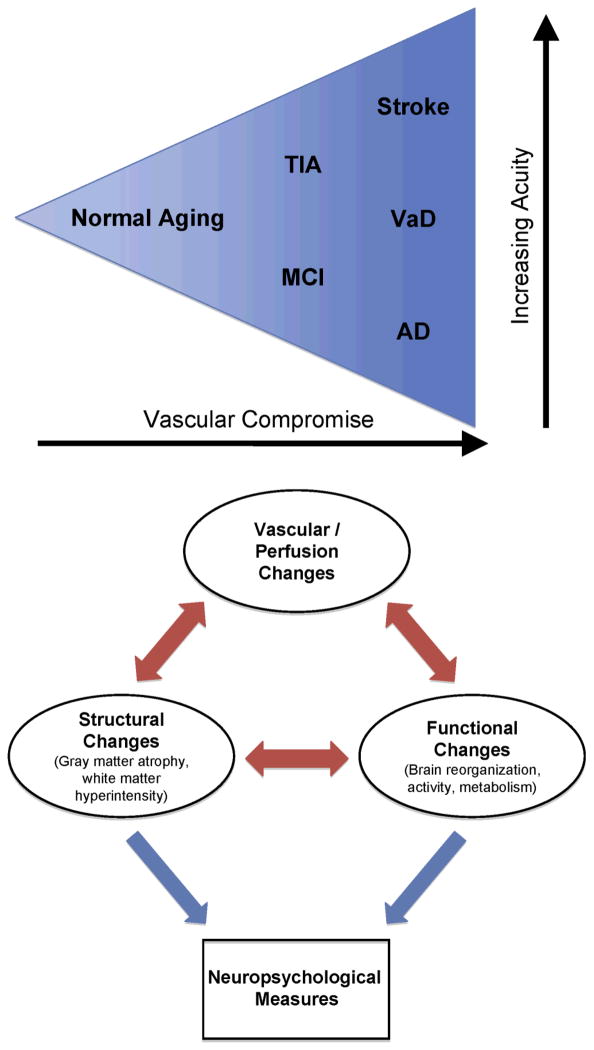

Although the evidence of a direct relationship between brain hypoperfusion and micro- or macro-structural changes leading to cognitive impairments is still forthcoming, recent studies suggest that the animal model of CBH proposed by de la Tore and colleagues [33] may very likely hold true in humans too. The thesis that CBH is a key determinant of eventual cognitive impairment is borne out of studies that have demonstrated that reperfusion of hypoperfused but dysfunctional regions leads to better functional outcomes [e.g., 102]. We therefore suggest that compromised vasculature may be represented on a continuum with mild vasculopathy falling at one end of this continuum (such as the vascular changes seen with aging), followed by moderate vasculopathy (such as those seen in patients with TIA or MCI) and severe vasculopathy (as noted in patients with stroke, VaD, or AD) falling at the other end of this continuum (see Figure 1). Chronic brain hypoperfusion may lead to micro- and macro-structural changes that are associated with cognitive impairments and dementia. However, the acuity of onset of these hypoperfusion changes contributes to the varying presentations of clinical disease in these population subsets.

Schematic figure of a perfusion model of chronic brain hypoperfusion (CBH) and micro- and macro-structural changes leading to behavioral deficits and cognitive impairment. The triangle represents a vasculature compromised in varying degrees with accompanying hemodynamic changes leading to CBH. Normal-aging, followed by TIA and MCI, followed by stroke, VaD, and AD in a graded fashion influence neural network reorganization in terms of increasing degree of vascular/perfusion changes as well as structural and functional mapping changes. These changes ultimately influence neuropsychological measures. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; TIA, transient ischemic attack; VaD, vascular dementia.

Conclusion

Although much is known about the role of hypoperfusion in AD, the direct consequences of disrupted blood flow is obscured by the co-occurrence of other neuropathological features implicated in AD including, e.g., arterial plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, vascular amyloid deposits, and cortical atrophy. Models of vascular lesion patients, however, provide a suitable model in which to investigate this phenomenon and to help elucidate the effects of decreased perfusion on cognition in AD. With the development of more economically efficient and non-invasive imaging techniques, such as ASL MRI, researchers are now able to measure blood flow with unprecedented spatial accuracy and with minimal risk to the patient. Thus, it is hopeful that in the near future, scientists will be able to identify putative biomarkers in AD and develop treatments to prevent, or at least slow, the progression of this incurable disease.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-2011-0010

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc3303148?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

The Cerebrovascular Side of Plasticity: Microvascular Architecture across Health and Neurodegenerative and Vascular Diseases.

Brain Sci, 14(10):983, 28 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39451997 | PMCID: PMC11506257

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Diastolic dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease model mice is associated with Aβ-amyloid aggregate formation and mitochondrial dysfunction.

Sci Rep, 14(1):16715, 19 Jul 2024

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 39030247 | PMCID: PMC11271646

Advances in Blood Biomarkers for Alzheimer's Disease: Ultra-Sensitive Detection Technologies and Impact on Clinical Diagnosis.

Degener Neurol Neuromuscul Dis, 14:85-102, 30 Jul 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39100640 | PMCID: PMC11297492

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Photobiomodulation in experimental models of Alzheimer's disease: state-of-the-art and translational perspectives.

Alzheimers Res Ther, 16(1):114, 21 May 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38773642 | PMCID: PMC11106984

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Associations of Serum Insulin and Related Measures With Neuropathology and Cognition in Older Persons With and Without Diabetes.

Ann Neurol, 95(4):665-676, 20 Feb 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38379184

Go to all (118) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Cerebral blood flow measured by arterial spin labeling MRI as a preclinical marker of Alzheimer's disease.

J Alzheimers Dis, 42 Suppl 4:S411-9, 01 Jan 2014

Cited by: 113 articles | PMID: 25159672 | PMCID: PMC5279221

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

The identification and cognitive correlation of perfusion patterns measured with arterial spin labeling MRI in Alzheimer's disease.

Alzheimers Res Ther, 15(1):75, 10 Apr 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 37038198 | PMCID: PMC10088108

Pattern of cerebral hypoperfusion in Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment measured with arterial spin-labeling MR imaging: initial experience.

Radiology, 234(3):851-859, 01 Mar 2005

Cited by: 370 articles | PMID: 15734937 | PMCID: PMC1851934

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NCRR NIH HHS (3)

Grant ID: UL1 RR025011

Grant ID: UL1 RR025011-04

Grant ID: UL1 RR025011-05

NHLBI NIH HHS (4)

Grant ID: T32 HL007936-10

Grant ID: T32 HL007936-11

Grant ID: T32 HL007936

Grant ID: T32 HL007936-12

NICHD NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: P30 HD003352

NIMH NIH HHS (3)

Grant ID: RC1 MH090912-01

Grant ID: RC1 MH090912-02

Grant ID: RC1 MH090912