Abstract

Background

Knowing a patient's health literacy can help clinicians and researchers anticipate a patient's ability to understand complex health regimens and deliver better patient-centered instructions and information. Poor health literacy has been linked with lower ability to function adequately in health care systems.Objective

We evaluated and compared three measures of health literacy and performance among older patients with diabetes.Design

Cross-sectional study utilizing in-person interviews conducted in participants' homes.Participants

A tri-ethnic sample (n = 563) of African American, American Indian, and white older adults with diabetes from eight counties in south-central North Carolina.Main measure

Participants completed interviews and health literacy assessments using the Short-Form Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (S-TOFHLA), the Rapid Estimates of Adult Literacy in Medicine Short-Form (REALM-SF), or the Newest Vital Signs (NVS). Scores for reading comprehension and numeracy were calculated.Results

Over 90% completed the S-TOFHLA numeracy and approximately 85% completed the S-TOFHLA reading and REALM-SF. Only 73% completed the NVS. The correlation of S-TOFHLA total scores with REALM-SF and NVS were 0.48 and 0.54, respectively. Age, gender, ethnic, educational and income differences in health literacy emerged for several instruments, but the pattern of results across the instruments was highly variable.Conclusions

A large segment of older adults is unable to complete short-form assessments of health literacy. Among those who were able to complete assessments, the REALM-SF and NVS performed comparably, but their relatively low convergence with the S-TOFHLA raises questions about instrument selection when studying health literacy of older adults.Free full text

Performance of Health Literacy Tests Among Older Adults with Diabetes

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Knowing a patient’s health literacy can help clinicians and researchers anticipate a patient’s ability to understand complex health regimens and deliver better patient-centered instructions and information. Poor health literacy has been linked with lower ability to function adequately in health care systems.

OBJECTIVE

We evaluated and compared three measures of health literacy and performance among older patients with diabetes.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional study utilizing in-person interviews conducted in participants’ homes.

PARTICIPANTS

A tri-ethnic sample (n =

= 563) of African American, American Indian, and white older adults with diabetes from eight counties in south-central North Carolina.

563) of African American, American Indian, and white older adults with diabetes from eight counties in south-central North Carolina.

MAIN MEASURE

Participants completed interviews and health literacy assessments using the Short-Form Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (S-TOFHLA), the Rapid Estimates of Adult Literacy in Medicine Short-Form (REALM-SF), or the Newest Vital Signs (NVS). Scores for reading comprehension and numeracy were calculated.

RESULTS

Over 90% completed the S-TOFHLA numeracy and approximately 85% completed the S-TOFHLA reading and REALM-SF. Only 73% completed the NVS. The correlation of S-TOFHLA total scores with REALM-SF and NVS were 0.48 and 0.54, respectively. Age, gender, ethnic, educational and income differences in health literacy emerged for several instruments, but the pattern of results across the instruments was highly variable.

CONCLUSIONS

A large segment of older adults is unable to complete short-form assessments of health literacy. Among those who were able to complete assessments, the REALM-SF and NVS performed comparably, but their relatively low convergence with the S-TOFHLA raises questions about instrument selection when studying health literacy of older adults.

Promotion of health literacy is a Healthy People objective1. For the purpose of this study, health literacy is defined as "the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions2." At the most fundamental level, health literacy has at least two major components: the ability to “make sense of” health-related terms and phrases (comprehension), and the ability to understand and apply numerical expressions to health matters (numeracy). A variety of instruments have been developed to measure health literacy3.The Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA), typically viewed as the standard, measures the ability to comprehend narrative text and the ability to perform computations involving health-related tasks4. A short-form version of the TOFHLA (S-TOFHLA) containing 36 items has been found to yield valid and reliable estimates of overall health literacy, including component sub scores for both comprehension and numeracy5.

There are several alternative measures for assessing health literacy. The Rapid Estimates of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) is a validated and widely-used instrument that uses word recognition to measure the comprehension domain of health literacy6. Scoring is based solely on an individual’s ability to read and correctly pronounce written medical terms. The REALM short form (REALM-SF) has been developed and validated for use in adults7. The Newest Vital Signs (NVS) is reported to be an overall measure of health literacy that consists primarily of questions requiring participants to read and interpret numerical facts by reading a standard food label8. Evidence indicating that poor understanding of food labels is reflective of low-level numeracy skills,9 suggests the NVS is not an overall measure of health literacy but rather a specific measure of numeracy.

Agreement has not yet been reached on the criteria to use for selecting the most appropriate measure of health literacy for different groups10. Measurement selection can be particularly important in health care settings where the importance of patient understanding of health management is essential. The issue of measurement selection is especially important with older adults where substantial variation in educational attainment and interactions with healthcare over the life course raises concerns about both the length and complexity of health literacy tools11. The S-TOFHLA may address length and complexity, but few studies have evaluated the performance of alternative tools like the REALM-SF and the NVS in older populations12. Evaluation of common instruments is an essential step for enabling rigorous primary care research focused on the role of health literacy in shaping older adults’ clinical experiences and outcomes.

The goal of this study is to determine the performance of the REALM-SF and the NVS relative to the S-TOFHLA for use among older adults. We use data collected from an ethnically diverse sample of older adults to: 1) delineate variation in health literacy (comprehension and numeracy); 2) document the concurrent validity of the REALM-SF and the NVS for assessing comprehension and numeracy, respectively; and 3) delineate variation in the concurrent validity of the REALM-SF and NVS by gender and ethnicity.

METHODS

Study Population

Data for this study are from a larger study of the beliefs and attitudes of older adults with diabetes. Older adults with diabetes provide a good context for studying the performance of health literacy instruments because effective disease management requires understanding and applying narrative and numerical information to achieve glucose control. The larger project recruited a sample of older adults with diabetes stratified by ethnic group (white, African American, and American Indian).

Participants were recruited from eight counties in south-central North Carolina. Inclusion criteria were age 60 years or older and having had a diabetes diagnosis for at least two years. Exclusion criteria included inability to complete informed consent or end-stage renal disease. A federally authorized Institutional Review Board (FWA #00001435) approved all sampling, recruitment and data collection procedures. Site-based sampling was used to recruit a representative sample from the study area13. Sites are places, organizations, or services used by members of the population of interest, in this case older adults with diabetes. A member of the study staff was sent to each site with explicit instructions on the number of individuals to recruit. Staff approached prospective study participants as they became available at each site; prospective participants were screened and invited to participate in the research if determined to be eligible. Signed informed consent was obtained from all study participants (n =

= 593). Data collection for the larger project required two separate interviewer-administered survey questionnaires administered approximately one month apart. Health literacy assessments were completed during the second interview (n

593). Data collection for the larger project required two separate interviewer-administered survey questionnaires administered approximately one month apart. Health literacy assessments were completed during the second interview (n =

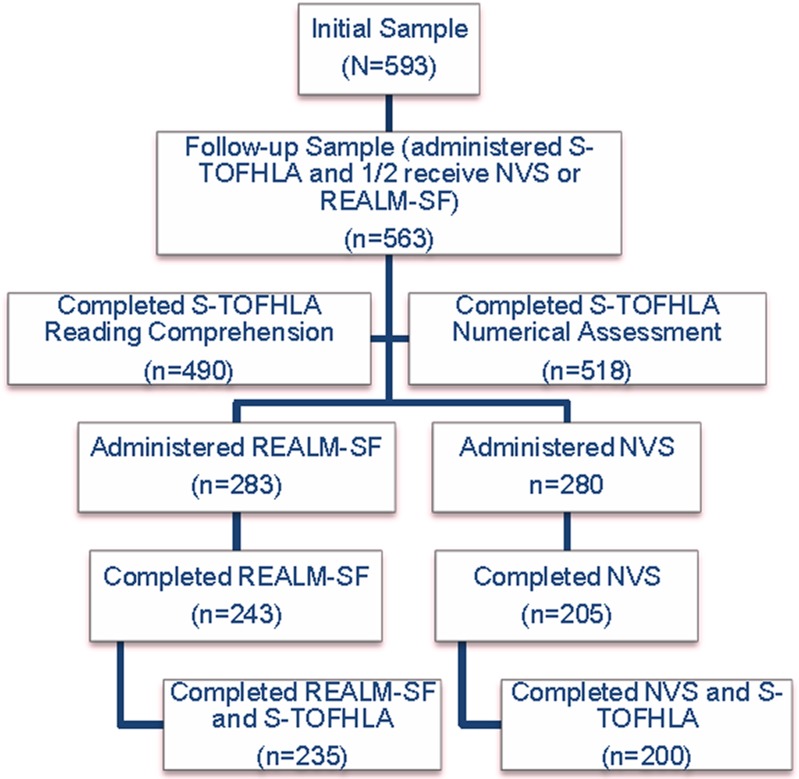

= 563) (Figure 1). All data collection was completed by trained research personnel.

563) (Figure 1). All data collection was completed by trained research personnel.

Personal characteristics assessed at the first interview included age, gender, ethnicity, educational attainment, marital status, and household income. Age was classified into three categories (i.e., 60 to 69, 70 to 79, and 80+), as was educational attainment (i.e., less than a high school education, high school graduate, and formal education beyond high school). Reported household income was used to construct a dichotomous indicator of poverty status based on 2007 federal poverty thresholds for household income and size14.

Measures

The data collection for health literacy occurred during the second interview. All study participants were assigned to complete the S-TOFHLA4. After first interviews were completed the REALM-SF7 and NVS8 were alternately assigned such that one-half of study participants received the REALM-SF and the other half received the NVS. Assignment of REALM-SF or NVS was performed at the time of recruitment and initial data collection.

The S-TOFHLA consists of 36 reading comprehension questions and four numeracy questions. Reading comprehension raw scores are scaled to give a score range of 0 to 72 while the numeracy questions are scaled to give a range of 0-28. Scores from each section are combined to give an S-TOFHLA score ranging from 0 to 100. The combined S-TOFHLA scores are used to categorize participants into three levels of functional health literacy: inadequate (0 to 53), marginal (54 to 66), and adequate (67 to 100) health literacy.

For the REALM-SF, participants read a list of seven common medical terms. Each correct answer results in a score of one point, and scores are converted to grade reading levels7. A score of zero indicates that the person will not be able to read most low literacy materials, while a score of 1 to 3 indicates a fourth to sixth grade reading level, while a score of 4 to 6 reflects a seventh to eighth grade reading level. A perfect score (i.e., 7) indicates a high school level of reading. Those with a score of

<

< 6 are considered at risk for poor literacy.

6 are considered at risk for poor literacy.The NVS is a screening tool that provides participants with a nutrition label and asks six questions8. Scores from the screener can be classified into three levels of literacy: low, limited, and adequate literacy, indicated by 0 to 1, 2 to 3, and 4 to 6 correct answers, respectively.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for scores obtained from each literacy assessment, and possible subgroup differences in literacy scores by race, gender, age group, education level, and income group were examined. For each demographic subgroup, we first selected a reference category (e.g., female for gender) for comparison; p-values for testing differences in literacy scores were reported. All statistical tests were two-sided with the significance level set at 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Pearson correlation coefficients were used for bivariate correlation analysis between literacy tests.

RESULTS

The ethnic composition of the sample was approximately balanced. Approximately one-third of the sample was African American; 30% of the sample was American Indian, and the remainder of the sample was white (Table 1). Over half of the sample (51.6%) was aged 60 to 69 years; 37.6% were aged 70 to 79, and the remainder of the sample was over 80 years. Over half of the sample (61.8%) was female. About one-third of participants reported having less than a high school education, while another one-third reported graduating from high school with no further formal education, and the remainder reported having some formal education beyond high school. Many participants (30.5%) reported household income below federal poverty thresholds for the household size, and less than half of the participants (46%) were currently married.

Table 1

Characteristics of Participants N (%) Comparing Those Who Completed with Those Who Did Not Complete Health Literacy Tests

Sample (n = = 563) 563) | Completed All Assigned Health Literacy Tests (n = = 435) 435) | Non-Completers (n = = 128) 128) | p-Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.06 | |||

| Male | 215 (38.1) | 157 (36.1) | 58 (45.3) | |

| Female | 348 (61.8) | 278 (63.9) | 70 (54.7) | |

| Age | 0.48 | |||

| 60 to 69 years | 290 (51.6) | 229 (52.6) | 61 (47.7) | |

| 70 to 79 years | 212 (37.6) | 162 (37.2) | 50 (39.1) | |

| 80+ years | 61 (10.8) | 44 (10.1) | 17 (13.3) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.01 | |||

| African American | 190 (33.9) | 145 (33.3) | 45 (35.2) | |

| American Indian | 168 (29.8) | 119 (27.4) | 49 (38.3) | |

| White | 205 (36.3) | 171 (39.3) | 34 (26.6) | |

| Education | <0.01 | |||

| <High school | 205 (36.5) | 131 (30.1) | 74 (58.3) | |

| High school graduate | 189 (33.6) | 161 (37.0) | 28 (22.1) | |

| >High school | 168 (29.9) | 143 (32.9) | 25 (19.7) | |

| Economic Status | <0.01 | |||

| Below poverty line | 169 (30.5) | 114 (26.6) | 55 (43.7) | |

| Above the poverty line | 385 (69.5) | 314 (73.4) | 71 (56.3) | |

| Marital Status | 0.06 | |||

| Not married | 302 (53.6) | 224 (51.5) | 78 (60.9) | |

| Currently married | 261 (46.4) | 211 (48.5) | 50 (39.1) |

*Difference between completers and non-completers

A large segment of the sample (n =

= 128) was not able to complete at least one of the literacy tests. The “non-completers” differed from those who could complete all literacy assessments (Table 1, columns 2 and 3). American Indians were disproportionately “non-completers”. Educational attainment and poverty status were associated with non-completer status such that having less than a high school education and living below the federal poverty threshold was associated with being classified as a non-completer.

128) was not able to complete at least one of the literacy tests. The “non-completers” differed from those who could complete all literacy assessments (Table 1, columns 2 and 3). American Indians were disproportionately “non-completers”. Educational attainment and poverty status were associated with non-completer status such that having less than a high school education and living below the federal poverty threshold was associated with being classified as a non-completer.

Rates of completion varied for each of the health literacy instruments. Over 90% (n =

= 518) of the sample completed the S-TOFHLA numeracy and 87% (n

518) of the sample completed the S-TOFHLA numeracy and 87% (n =

= 490) completed the S-TOFHLA reading (Table 2). A total of 283 participants received the REALM-SF, of which 243 (86%) were able to complete the assessment. Another 280 participants received the NVS, of which 205 (73%) were able to complete the assessment (Table 2).

490) completed the S-TOFHLA reading (Table 2). A total of 283 participants received the REALM-SF, of which 243 (86%) were able to complete the assessment. Another 280 participants received the NVS, of which 205 (73%) were able to complete the assessment (Table 2).

Table 2

Health literacy Among Older Adults with Diabetes

S-TOFHLA TOTAL Score (n = = 490) 490) | S-TOFHLA Reading Score (n = = 490) 490) | S-TOFHLA Numeracy Score (n = = 518) 518) | REALM-SF* Score (n = = 243) 243) | NVS* Score (n = = 205) 205) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literacy Classification | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | N (%) |

| Inadequate† | 76 (15.5) | 80 (16.3) | n/a | 25 (10.3) | 44 (21.5) |

| Marginal/limited‡ | 65 (13.3) | 54 (11.0) | n/a | 66 (27.2) | 58 (28.3) |

| Adequate | 349 (71.2) | 356 (72.7) | n/a | 152 (66.6) | 103 (50.2) |

Short Test of Functional Literacy in Adults (S-TOFHLA), Rapid Estimates of Adult Literacy in Medicine Short Form (REALM-SF), Newest Vital Signs (NVS)

*Half of participants were assigned the REALM-SF and the other half were assigned the NVS

†Inadequate: S-TOFHLA (0-53), NVS score (0 to 1), REALM-SF (<3) indicating < a 6th grade reading level

a 6th grade reading level

‡Marginal/limited: S-TOFHLA (54-66), NVS score (2-3), REALM-SF scores of > 4 or <

4 or < 6 indicates a 7th to 8th grade reading level

6 indicates a 7th to 8th grade reading level

Among those who were able to complete an assessment, literacy was generally adequate. The average score for the S-TOFHLA reading portions was 53.9 +

+ 18.4 (maximum score 72), while the numeracy was 22.2

18.4 (maximum score 72), while the numeracy was 22.2 +

+ 6.8 (maximum score 28). Based on standard S-TOFHLA categorizations,4 over a quarter of the sample had marginal (13.3%) or inadequate (15.5%) health literacy (Table 2). The average score for the REALM-SF for the sample was 6.0

6.8 (maximum score 28). Based on standard S-TOFHLA categorizations,4 over a quarter of the sample had marginal (13.3%) or inadequate (15.5%) health literacy (Table 2). The average score for the REALM-SF for the sample was 6.0 +

+ 1.7 and the average score for the NVS was 3.4

1.7 and the average score for the NVS was 3.4 +

+ 1.9. The percentage of persons with classified as having inadequate literacy was 37.5% and 49.8% for the REALM-SF and the NVS, respectively.

1.9. The percentage of persons with classified as having inadequate literacy was 37.5% and 49.8% for the REALM-SF and the NVS, respectively.

Performance of each health literacy instrument, including the comprehension and numeracy subscales of the S-TOFHLA differed by several demographic characteristics (Table 3). Ethnic differences were evident for each health literacy instrument, such that American Indians and African Americans had lower scores than whites on each instrument, except for the numeracy subscale of the S-TOFHLA. None of the health literacy scores differed between American Indians and African Americans. There was no consistent evidence of differences in health literacy scores by gender, although men’s REALM-SF scores were lower than women’s. Participants aged 80+ had lower S-TOFHLA total scores than those in both the 60 to 69 and 70 to 79 age groups. However, when considering the comprehension and numeracy subcomponents of the S-TOFHLA, only comprehension scores differed by age. Similarly, there were no age-related differences in literacy scores obtained from the REALM-SF or the NVS.

Table 3

Health Literacy Scores Evaluated by Demographic Characteristics

| Demographic Variable | S-TOFHLA Total Score | S-TOFHLA Reading Score | S-TOFHLA Numeracy Score | REALM-SF Score | NVS Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Maximum 100 (N = = 490) 490) | Maximum 72 (N = = 490) 490) | Maximum 28 (N = = 518) 518) | Maximum 7 (N = = 243) 243) | Maximum 6 (N = = 205) 205) | |

| Race | |||||

| Whites | 52.0 + + 11.0 11.0 | 29.1 +7.4 +7.4 | 22.8 + + 6.2 6.2 | 6.4 + + 1.2 1.2 | 4.0 + + 1.6 1.6 |

| American Indians (AI) | 47.4 + + 13.8* 13.8* | 25.4 + + 10.0* 10.0* | 21.7 + + 7.0 7.0 | 5.5 + + 2.1* 2.1* | 2.9 + + 1.8* 1.8* |

| African Americans (AA) | 48.1 + + 14.3* 14.3* | 25.9 + + 10.0* 10.0* | 21.9 + + 7.2 7.2 | 5.8 + + 1.8* 1.8* | 3.2 + + 2.0* 2.0* |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 49.9 + + 12.9 12.9 | 27.5 + + 8.9 8.9 | 22.3 + + 6.7 6.7 | 6.2 + + 1.5 1.5 | 3.5 + + 1.9 1.9 |

| Male | 48.5 + + 13.6 13.6 | 26.1 + + 9.7 9.7 | 22.0 + + 6.9 6.9 | 5.6 + + 2.0† 2.0† | 3.2 + + 1.8 1.8 |

| Age | |||||

| 60 to 69 years | 51.2 + + 12.4 12.4 | 28.6 + + 8.4 8.4 | 22.4 + + 6.6 6.6 | 5.9 + + 1.8 1.8 | 3.5 + + 1.9 1.9 |

| 70 to 79 years | 48.8 + + 13.8 13.8 | 26.1 + + 9.8‡ 9.8‡ | 22.2 + + 7.0 7.0 | 6.1 + + 1.7 1.7 | 3.2 + + 2.0 2.0 |

| 80+ years | 42.6 + + 12.3‡,§ 12.3‡,§ | 21.6 + + 8.8‡ 8.8‡ | 21.0 + + 6.9 6.9 | 6.0 + + 1.4 1.4 | 3.3 + + 1.7 1.7 |

| Education | |||||

| >High School | 54.4 + + 8.7 8.7 | 30.1 + + 6.5 6.5 | 24.3 + + 5.0 5.0 | 6.5 + + 1.1 1.1 | 4.0 + + 1.7 1.7 |

| High School grad | 50.4 + + 12.2|| 12.2|| | 27.9 +8.8|| | 22.4 + + 6.1|| 6.1|| | 6.3 + + 1.3 1.3 | 3.4 + + 1.9|| 1.9|| |

| <High School | 42.9 + + 15.4||,¶ 15.4||,¶ | 22.5 +10.4||,¶ | 19.9 + + 8.1||,¶ 8.1||,¶ | 5.2 + + 2.3||,¶ 2.3||,¶ | 2.5 + + 1.8||,¶ 1.8||,¶ |

| Income | |||||

| Above poverty line | 50.7 + + 12.5 12.5 | 27.8 + + 8.8 8.8 | 22.7 + + 6.4 6.4 | 6.1 + + 1.7 1.7 | 3.5 + + 1.8 1.8 |

| Below poverty line | 46.4 + + 14.2# 14.2# | 24.9 + + 10.0# 10.0# | 21.0 + + 7.5# 7.5# | 5.8 + + 1.8# 1.8# | 3.0 + + 2.0 2.0 |

Short Test of Functional Literacy in Adults (S-TOFHLA), Rapid Estimates of Adult Literacy in Medicine Short Form (REALM-SF), Newest Vital Signs (NVS)

*Score differs from Whites; †Score differs from females; ‡Score differs from the 60- to 69-year-old group, §Score differs from the 70- to 79-year-old group; ||Score differs from the >

> high school degree group, ¶Score differs from high school graduate group; #Score differs from above poverty line. All differences tested at p

high school degree group, ¶Score differs from high school graduate group; #Score differs from above poverty line. All differences tested at p <

< 0.05

0.05

Scores for each health literacy instrument were strongly associated with educational attainment. For all instruments except for one, individuals with less than a high school education had the lowest health literacy scores, followed by those with a high school degree only and those with some education beyond high school. The only exception to this pattern was observed for the REALM-SF. Finally, scores on all the instruments, except the NVS, were lower for those living below poverty compared to those above the poverty threshold.

The Pearson bivariate correlation between total scores from the S-TOFHLA and the REALM-SF was 0.48 among those who were assigned and able to complete these instruments. The corresponding correlation between total scores from the S-TOFHLA and the NVS was 0.54. The bivariate association of the REALM-SF and the NVS with the comprehension subcomponent (i.e., the reading component) of the S-TOFHLA, were 0.43 and 0.50, respectively. Bivariate associations of the REALM-SF and the NVS with the numeracy subcomponent of the S-TOFHLA were 0.38 and 0.39, respectively. Analyses relevant to the third aim of this study (i.e., to delineate variation in the concurrent validity of REALM-SF and NVS relative to the S-TOFHLA) indicated no significant differences in the magnitude of observed correlations among scores obtained from the instruments by gender, or ethnicity.

DISCUSSION

Promoting health literacy is a national priority. Low health literacy has been shown to be associated with negative clinical outcomes15,16. The performance of alternative health literacy assessments in older populations is under-researched; consequently, the goal of this study was to determine the performance of the REALM-SF and the NVS, relative to the S-TOFHLA for assessing health literacy among older adults with diabetes. This study was implemented in a sample of older individuals with diabetes, a condition for which health literacy is essential because disease management requires understanding and applying narrative and numerical information to achieve glucose control. In our sample, 28.8% had marginal or inadequate health literacy by the S-TOFHLA. Data from other cohorts of older individuals show similar trends of poor health literacy11,17.

The results of this study suggest various challenges to assessing health literacy among older adults. Non-completion rates of literacy tests are frequently not reported in either cohort studies or clinical trials, and exclusion criteria often eliminate individuals who may have marginal health literacy. As a result, overestimation of adequate literacy in research studies can occur. In the current study, about 23% could not complete at least one of the literacy tests. The majority of individuals were able to complete the S-TOFHLA numeracy portion (92%) while the reading portion of the S-TOFHLA and REALM-SF had similar rates of completion (over 85%). Approximately 27% of study participants could not complete the NVS health literacy instrument, indicating a much higher rate of non-completion than the other health literacy tests used in this study. Many reasons were given for not completing the instruments by participants, some of which speak directly to health literacy (e.g., self-identifying as illiterate), but other explanations like eyesight, physical or sensory impairment, or simply not being able to complete the instruments within a specified time period are ambiguous for understanding health literacy. These results suggest that health literacy cannot be accurately assessed in a large segment of older adults for a variety of age-related reasons using existing instruments. Further measurement development and refinement among older adults is essential for equipping researchers and clinicians in meeting the Healthy People objective of promoting health literacy1.

Several strands of evidence from this study suggest that researchers and clinicians need to carefully consider substituting the REALM-SF or the NVS for the S-TOFHLA when working with older adults. The correlations of the total S-TOFHLA with the REALM-SF and the NVS were only 0.48 and 0.54, respectively, suggesting that both the REALM-SF and the NVS are not capturing the measurement domain of the S-TOFHLA. These results diverge from previous research reporting a correlation of 0.81 between scores on the S-TOFHLA and the REALM,18 and a correlation of 0.61 between scores on the S-TOFHLA and the NVS19. The comparatively modest correlations among measures of health literacy observed in this study are likely attributed to our sample being older, more ethnically diverse, and having lower levels of education; these demographic characteristics likely pose challenges to validly measuring health literacy. A recent study evaluating the NVS and TOFHLA reading in a small (n =

= 62) sample of older African Americans found these assessments were not comparable and suggested that the NVS may not be suitable for older adults20. Our study replicates these findings in a larger and ethnically heterogeneous sample, thereby adding greater concern about the appropriateness of the NVS for use with older adults.

62) sample of older African Americans found these assessments were not comparable and suggested that the NVS may not be suitable for older adults20. Our study replicates these findings in a larger and ethnically heterogeneous sample, thereby adding greater concern about the appropriateness of the NVS for use with older adults.

A second strand of evidence suggesting that researchers and clinicians need to carefully consider which health literacy tool to use is divergence in subgroup comparisons from different instruments. The S-TOFHLA, for example, demonstrated clear age-related differences in overall literacy but a similar pattern was not produced for the REALM-SF, or the NVS. The clear and almost dose-response educational differences observed in S-TOFHLA scores were not apparent in scores from the REALM-SF, while the NVS did not detect the differences in overall health literacy or numeracy scores by income that were observed using the S-TOFHLA.

The inconsistent performance of the REALM-SF and NVS relative to the S-TOFHLA can be attributed to several factors. The first is statistical: analyses for the REALM-SF and NVS were based on smaller samples and had less power. Although possible, inadequate power is not the full explanation because both the REALM-SF and the NVS produced the same pattern of results as the S-TOFHLA for both race and gender. Similarly, the NVS and S-TOFHLA produced the same pattern of scores by educational attainment, but the S-TOFHLA appeared to have more sensitivity to educational attainment than did the REALM-SF. Therefore, inadequate power cannot fully explain the diverging pattern of results among the instruments.

Differences in content may provide a second explanation for the lack of a stronger inter-correlation of the S-TOFHLA with the REALM-SF and the NVS, and a diverging pattern of subgroup differences in literacy scores. The S-TOFHLA is intended to capture the entire domain of health literacy; by contrast, the REALM is primarily a measure of comprehension literacy, and the NVS weighs heavily toward numeracy. Our data provide some support for this explanation. The REALM-SF produces a pattern of results similar to the reading comprehension items from the S-TOFHLA for race and income, while the NVS produces a pattern of results similar to the numeracy items from the S-TOFHLA for gender, age, and educational attainment. Again, however, differential content does not provide a complete explanation because the NVS produces ethnic differences in numeracy where none exists with the S-TOFHLA. Likewise, the REALM-SF produces gender differences in comprehension literacy where there were none evidenced with the S-TOFHLA.

This study has some limitations. First, the generalizability of study findings beyond the current sample is unknown because the sample was not randomly selected. Next, the attenuated inter-correlation among measures of health literacy used in this study relative to associations observed in previous research could reflect our use of short-form measures of each instrument. However, this issue requires substantial future research because the feasibility of using long-form versions of the assessments with older adults is highly suspect: if 20% of older adults could not complete a short-form version, the inability to complete long-form versions is likely even greater. Thus, while the use of short-form versions may contribute to the divergent results of this study compared to previous research, it does not take away from the fact that existing short-form health literacy instruments do not appear to be measuring the same latent construct in older adults. Other limitations include potential participant fatigue in completing multiple literacy tests.

Limitations notwithstanding, this study has several strengths including non-completion data from a sample of community-dwelling older adults. This study also includes individuals from minority groups that have not been well-represented in previous studies. These populations are particularly at risk for poor health literacy and are vulnerable to poorly managed chronic conditions, including diabetes. There is also good generalizability of the results to other community populations. The study population has significant health care barriers, including limited access to high quality primary and specialty care. Understanding literacy levels in this population can impact future interventions to address barriers to effective care and management of chronic conditions, like diabetes.

Individuals with limited literacy have worse health outcomes related to self-management, understanding of medical conditions, adherence, and utilization of preventative services21,22. Recent comprehensive reviews detail issues around health literacy including the need for further evaluation of health literacy definitions, approaches, and outcomes22,23. Although a variety of instruments exist for assessing literacy, choosing the most appropriate health literacy assessment is challenging, especially among older adults, and the results of this study indicate that the NVS or REALM-SF should not be substituted for the S-TOFHLA.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by grant R01 AG17587 from the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interests

None disclosed.

Author Contributions

All authors participated in the acquisition of subjects, analysis and interpretation of data, and the corresponding author prepared the manuscript.

References

Articles from Journal of General Internal Medicine are provided here courtesy of Society of General Internal Medicine

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1927-y

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc3326106?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

Health literacy in older adults: The newest vital sign and its relation to cognition and healthy lifestyle behaviors.

Appl Neuropsychol Adult, 1-8, 29 Mar 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38552259

Health literacy of informal caregivers of older adults with dementia: results from a cross-sectional study conducted in Florence (Italy).

Aging Clin Exp Res, 35(1):61-71, 19 Oct 2022

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 36260214 | PMCID: PMC9580430

The Relationship Between Attitudes about Research and Health Literacy among African American and White (Non-Hispanic) Community Dwelling Older Adults.

J Racial Ethn Health Disparities, 9(1):93-102, 07 Jan 2021

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 33415701 | PMCID: PMC7790309

Questionnaire validation practice within a theoretical framework: a systematic descriptive literature review of health literacy assessments.

BMJ Open, 10(6):e035974, 01 Jun 2020

Cited by: 9 articles | PMID: 32487577 | PMCID: PMC7265003

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Factors influencing chemotherapy knowledge in women with breast cancer.

Appl Nurs Res, 56:151335, 23 Jul 2020

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 32739071 | PMCID: PMC7722178

Go to all (35) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Concurrent validity and acceptability of health literacy measures of adults hospitalized with heart failure.

Appl Nurs Res, 46:50-56, 13 Feb 2019

Cited by: 7 articles | PMID: 30853076

Does numeracy correlate with measures of health literacy in the emergency department?

Acad Emerg Med, 21(2):147-153, 01 Feb 2014

Cited by: 28 articles | PMID: 24673670 | PMCID: PMC3970174

Feasibility and diagnostic accuracy of brief health literacy and numeracy screening instruments in an urban emergency department.

Acad Emerg Med, 21(2):137-146, 01 Feb 2014

Cited by: 41 articles | PMID: 24673669 | PMCID: PMC4042843

Measuring health literacy in individuals with diabetes: a systematic review and evaluation of available measures.

Health Educ Behav, 40(1):42-55, 09 Apr 2012

Cited by: 50 articles | PMID: 22491040

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NIA NIH HHS (3)

Grant ID: R01 AG017587-08

Grant ID: R01 AG017587

Grant ID: R01 AG17587

1

1