Abstract

Objective

Heparan sulfate proteoglycans regulate key steps of blood vessel formation. The present study was undertaken to investigate if there is a functional overlap between heparan sulfate proteoglycans and chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans during sprouting angiogenesis.Methods and results

Using cultures of genetically engineered mouse embryonic stem cells, we show that angiogenic sprouting occurs also in the absence of heparan sulfate biosynthesis. Cells unable to produce heparan sulfate instead increase their production of chondroitin sulfate that binds key angiogenic growth factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor A, transforming growth factor β, and platelet-derived growth factor B. Lack of heparan sulfate proteoglycan production however leads to increased pericyte numbers and reduced adhesion of pericytes to nascent sprouts, likely due to dysregulation of transforming growth factor β and platelet-derived growth factor B signal transduction.Conclusions

The present study provides direct evidence for a previously undefined functional overlap between chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans and heparan sulfate proteoglycans during sprouting angiogenesis. Our findings provide information relevant for potential future drug design efforts that involve targeting of proteoglycans in the vasculature.Free full text

Functional overlap between chondroitin and heparan sulfate proteoglycans during VEGF-induced sprouting angiogenesis

Associated Data

Abstract

Objective

Heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) regulate key steps of blood vessel formation. The present study was undertaken to investigate if there is a functional overlap between HSPGs and chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs) during sprouting angiogenesis.

Methods and Results

Using cultures of genetically engineered mouse embryonic stem cells, we show that angiogenic sprouting occurs also in the absence of HS biosynthesis. Cells unable to produce HS instead increase their production of CS that binds key angiogenic growth factors such as VEGFA, TGFβ and PDGFB. Lack of HSPG production however leads to increased pericyte numbers and reduced adhesion of pericytes to nascent sprouts, likely due to dysregulation of TGFβ and PDGFB signal transduction.

Conclusions

The present study provides direct evidence for a previously undefined functional overlap between CSPGs and HSPGs during sprouting angiogenesis. Our findings provide information relevant for potential future drug design efforts that involve targeting of PGs in the vasculature.

Angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels from preexisting vasculature, occurs during several pathological conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and cancer 1. Sprouting angiogenesis, a major mechanism of neovascularization, depends on a set of spatially and temporally strictly regulated processes, including (1) induction and selection of a leading tip cell among endothelial cells (ECs); (2) tip cell migration followed by stalk formation; (3) lumen formation and vessel anastomosis, and finally (4) stabilization of the immature vessel through the recruitment of mural cells (pericytes) 2. Key factors identified to regulate sprouting angiogenesis include vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA), fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) and platelet-derived growth factor B (PDGFB). Importantly, proteoglycans (PGs) carrying heparan sulfate (HS) polysaccharide chains have been shown to bind these and other angiogenic modulators through their HS chains and act as coreceptors. HSPGs thereby support VEGFA- and FGF2-signaling required for angiogenesis, as well as the formation of PDGFB gradients to allow for recruitment of pericytes along nascent vessels 3–10.

HS biosynthesis is strictly regulated resulting in the formation of a multitude of sulfated protein-binding epitopes. The HS chains evolve by the stepwise addition of alternating glucuronic acid (GlcA) and N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) residues by the HS polymerases exostosin 1 and 2 (EXT1 and EXT2) to oligosaccharide acceptor linkage regions attached to core proteins. As the HS chains grow in length, they undergo several consecutive modification steps, including N-deacetylation and N-sulfation of GlcNAc residues by N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferases (NDSTs), epimerization of GlcA to iduronic acid by a C5-epimerase, and finally sulfation at various locations by O-sulfotransferases. It is important to note that while protein-protein interactions rely on unique primary sequences, HS-protein interactions depend on HS charge distribution as well as overall conformation 11, rather than on a specific sequence of sulfated disaccharide units 12. From this notion it follows that other sulfated polysaccharides such as chondroitin sulfate (CS), having a charge density similar to HS and also being attached to proteoglycan core proteins, may regulate growth factor activities in a fashion analogous to HS.

Several recent studies have shed light on the role of HS in vascular development. Mice that lack the HS-retention motif of PDGFB, or produce reduced levels of functional HS (due to deletion of Ndst1), display delayed pericyte recruitment, as well as defective attachment of pericytes to endothelial cells 10, 13. Endothelial-specific loss of Ndst1 has also been shown to inhibit tumor angiogenesis 14. Further, a recent study examining pericyte-specific loss of Ext1 suggests that HSPGs must be expressed by the pericyte itself to allow for proper PDGF- and TGFs-signaling during pericyte recruitment15. However, as both Ext1−/− 16 and Ndst1/2−/− 17 mouse embryos exhibit severe gastrulation defects and die early during embryonic development, these global loss-of function models cannot be used to study vascular development and sprouting angiogenesis and the complex interplay between endothelial cells and pericytes.

The present study examines angiogenic sprouting in differentiating stem cell cultures, so called embryoid bodies (EBs), where all endothelial cells and pericytes exhibit defective HS biosynthesis. Elimination of HS N-sulfation was shown to result in reduced production of both HS and CS resulting in severely delayed angiogenesis, including arrest in pericyte formation. Surprisingly, the complete loss of HS-production in Ext1−/− EBs was compatible with angiogenic sprouting and pericyte formation and resulted in increased CS biosynthesis. CS was further shown to affect TGFβ signaling and PDGFB signaling. Our results thus strongly suggest that many steps of the angiogenic process may be modulated by CSPGs, and demonstrate a previously unrecognized functional overlap between CS and HS in the support of VEGF-induced sprouting angiogenesis.

Materials and Methods

For an expanded Materials and Methods section, please see the supplemental materials, available online at http://atvb.ahajournals.org.

Culture of EBs, primary cells and MEFs

Wild type (wt) mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs) of the R1 strain18 were a gift from Dr. Andras Nagy (Samuel Lunenfeld Research Institute, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada). The Ndst1/2−/− and the Ext1−/− ESCs were established as described19,16 and EBs generated according to standard procedures9, see the supplemental materials for details. Human aortic smooth muscle cells (hAoSMCs) were purchased from Lonza and maintained in medium 231 supplemented with SMGS (Invitrogen). HUVECs (Lonza, Invitrogen) were cultured in EGM2-MV medium (Lonza, Invitrogen), and MEFs cultured in high-glucose DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS.

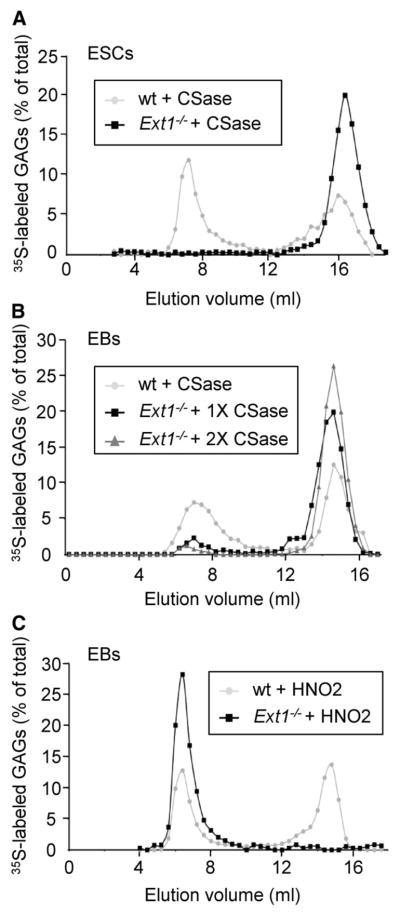

Metabolic labeling and characterization of 35S-labeled GAGs

The total glycosaminoglycan (GAG) pools containing both HS and CS produced by wt and Ext1−/− ESCs, or GAGs produced by EBs stimulated with VEGFA for 12 days, were metabolically labeled for 20 h with 500 μCi of 35S-sulfate in 10 ml of cell culture medium. The isolation of labeled GAGs is described in detail in the supplemental materials section. The radiolabeled GAG pools were next subjected to digestion either with 0.05 units of Chondroitinase (CSase) ABC (Seikagaku)20 to degrade CS, or treated with nitrous acid at pH 1.5 to degrade HS. The treated GAG pools were analyzed by gel chromatography on Sephadex G50 (0.5 × 100 cm) eluted in 0.2 M NaCl; fractions of 0.4 ml were collected and the 35S-radioactivity measured.

Compositional analysis of HS and CS

Unlabeled HS and CS were isolated form ESCs and EBs as described in the supplemental materials, and thereafter analyzed by RPIP-HPLC according to the protocols previously described by Ledin et al.21.

Isolation of endothelial cells from EBs and quantitative RT-PCR

Protocols for isolation of endothelial cells on basis of CD31 expression, together with protocols for quantitative RT-PCR, are described in the supplemental materials.

Immunofluorescence, Western Blotting and signaling assays

Whole EBs in collagen gel were cut out and fixed in 4% p-formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 min at room temperature, and thereafter blocked and permeabilized for 1 h. The fixed EBs were incubated over night at 4°C with primary antibodies, followed by washing and incubation with secondary antibodies the next day. Detailed procedures for analysis by immunofluorescence, western blotting and growth factor signaling assays are described in the supplemental materials.

Nitrocellulose filter binding assay

35S-Labeled GAGs were purified from wt and Ext1−/− ESCs and EBs (stimulated with VEGFA for 12 days) and probed for binding to VEGFA-165, PDGFB and TGFβ1 using the previously described nitrocellulose filter-binding assay 22.

Results

Ext1−/− EBs are capable of sprouting angiogenesis, albeit with defective pericyte attachment

The EB model for sprouting angiogenesis was employed to study sprout formation when HS biosynthesis was eliminated or deficient in both endothelial cells and mural cells. EBs were generated from genetically engineered mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs) deficient in the HS-polymerase EXT1 or lacking the HS-modifying enzymes NDST1 and NDST2. While the Ext1−/− ESCs have been shown to lack HS biosynthesis, Ndst1/2−/− ESCs synthesize an undersulfated HS containing only low levels of 6-O-sulfate groups19.

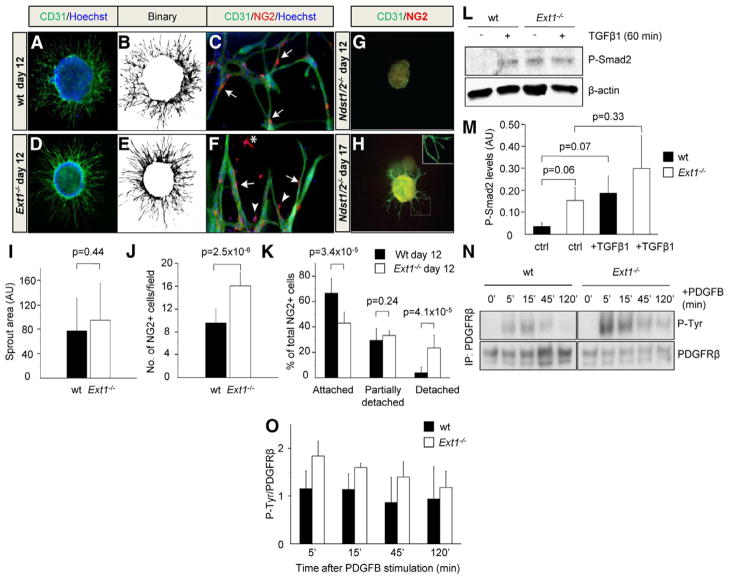

EBs were grown in a three-dimensional matrix of collagen I and stimulated with VEGFA165 to enhance sprouting angiogenesis 23. Both wild-type (wt) and Ext1−/− EBs showed vigorous angiogenic sprouting in response to VEGFA at day 12 of differentiation (Figure 1A, D). Indeed, no significant difference in sprout area fraction was observed between wt and Ext1−/− EBs (Figure 1B, E, I), suggesting that HS is not required for early angiogenic sprouting and tube formation. However, the Ext1−/− EBs exhibited increased pericyte formation, accompanied by an increased occurrence of detached pericytes, as compared to the wt control (Figure 1C, F, J–K). In contrast, Ndst1/2−/− EBs failed to produce angiogenic sprouts during the first 12 days of culture, in agreement with previous findings (Figure 1G) 9, while culture for 15 days or longer supported some formation of angiogenic sprouts in the Ndst1/2−/− EBs. No pericytes were however detected along the Ndst1/2−/− sprouts, indicating suppressed pericyte formation (Figure 1H).

wt, Ext1−/− and Ndst1/2−/− EBs were grown in collagen I for 12 days (A–G) or 17 days (H) in the presence of VEGFA (30 ng/ml). ECs were visualized by staining for CD31 (green) (A and D), and binary images were used for quantification (B and E). ECs and pericytes (PCs) in wt, Ext1−/− and Ndst1/2−/− EBs were visualized by staining for CD31 (green) and NG2 (red), respectively (C, F, G and H). Note the absence of pericytes in Ndst1/2−/− EBs, and the presence of detached (star), partially detached (arrow heads) and attached (arrows) pericytes in the Ext1−/− EBs. The sprouting area fractions of individual EBs were quantified (I; n = 12) as well as the number of NG2+ cells and their localization in relation to ECs (J–K; n = 11). The ability of TGFβ (5 ng/ml) to induce Smad2 phosphorylation (P-Smad2) (L and M; n = 3) and PDGFB (100 ng/ml) to induce PDGFRβ phosphorylation (N) was studied in wt and Ext1−/− EBs. PDGFRβ protein was immunoprecipitated (IP) followed by immunodetection of phosphotyrosine residues (P-Tyr) and PDGFRβ. (O) Quantification of PDGFRβ phoshorylation relative to total PDGFRβ protein after PDGFB stimulation and IP (n = 2).

Aberrant TGFβ- and PDGFB-signaling in Ext1−/− EBs

TGFβ and PDGFB have been shown to regulate pericyte differentiation and attachment24, 25. In agreement with the above described pericyte defects we found that both the TGFβ- and PDGFB-signaling pathways were affected in the Ext1−/− EBs. Markedly higher levels of phospho-Smad2 (a downstream target of TGFβ) were observed without addition of exogenous TGFβ in Ext1−/− EBs compared to the wt control, and the phospho-Smad2 levels did not increase further by acute TGFβ1 stimulation (Figure 1L–M). We next used the in situ proximity ligation assay (in situ PLA) to determine whether PDGF-receptor beta (PDGFRβ) was expressed and activated in the different cultures. As shown in Supplemental Figure IA, PDGFRβ was indeed expressed and tyrosine phosphorylated in both wt and Ext1−/− pericytes. Next, PDGFRβ was immunoprecipitated to analyze the degree of tyrosine phosphorylation (P-Tyr) per receptor in response to PDGFB at different time points after stimulation. A higher degree of PDGFRβ phosphorylation was detected in Ext1−/− EBs as compared to wt EBs in all samples analyzed (Figure 1N-O and Supplemental Figure IIA). Quantitative analysis of PDGFRβ protein expression was performed by immunoblotting of EB lysates, and the results showed that Ext1−/− EBs express ~50 % higher levels of PDGFRβ compared to wt EBs (Supplemental Figure IIB). Further, although not statistically significant, a tendency for decreased phosphorylation of the downstream target AKT, and increased phosphorylation of ERK1/2 was noted in the Ext1−/− EBs (Supplemental Figure IIC). Adding either exogenous PDGFB or TGFβ1 to the Ext1−/− cultures did not rescue pericyte attachment. Instead, these growth factor treatments clearly increased both the pericyte numbers and the extent of pericyte detachment (Supplemental Figure IB). Even though TGFβ– and PDGFB-signaling appeared dysregulated in Ext1−/− cultures, VEGFR2 activation was shown to be similar in VEGFA165-treated wt and Ext1−/− EBs (data not shown) in agreement with the strong VEGFA-induced sprouting seen in these cultures (Figure 1D–F).

Differentiated cells in Ext1−/− EBs are incapable of HS biosynthesis

Several aspects of angiogenesis and VEGF function have been shown to be regulated by HS 26. The fact that Ext1−/− EBs formed vessels in response to VEGFA could still in theory be due to some residual HS biosynthesis during differentiation in these cultures, despite the lack of EXT1 expression. To address this issue, we isolated metabolically 35S-labeled glycosaminoglycans (GAGs; including both HS and CS) from wt and Ext1−/− ESCs and EBs and performed GAG structural analysis.

Starting with ESCs, treatment of the total GAG pool from wt stem cells with chondroitinase (CSase) ABC, which selectively cleaves CS but not HS, resulted in degradation of approximately 50% of the material (Figure 2A). In contrast, the total GAG pool isolated from Ext1−/− ESCs were completely degraded by CSase treatment, indicating that no HS was produced by the Ext1−/− ESCs, in full agreement with previous observations 16 (Figure 2A). The same experiment was repeated with labeled GAGs from differentiated EBs with vascular structures. Consistently, half of the GAG pool isolated from wt cells was degraded by CSase (Figure 2B). A small fraction of GAGs isolated from Ext1−/− EBs however appeared to be resistant to CSase treatment (Figure 2B). A second round of enzyme treatment nevertheless reduced the amount of intact GAGs substantially, indicating that incomplete degradation at least in part could explain the small amount of non-degraded 35S-macromolecules in the Ext1−/− EB GAG preparation (Figure 2B). To exclude that HS was synthesized by the Ext1−/− EBs, the EB-derived GAG preparations were treated with nitrous acid at pH 1.5 which cleaves HS at N-sulfated residues. All GAGs isolated from Ext1−/− EBs resisted this treatment, whereas approximately 50% of GAGs isolated from wt EBs was degraded (Figure 2C). It could thus be concluded that Ext1−/− EBs, just like Ext1−/− ESCs, produce CS but not HS.

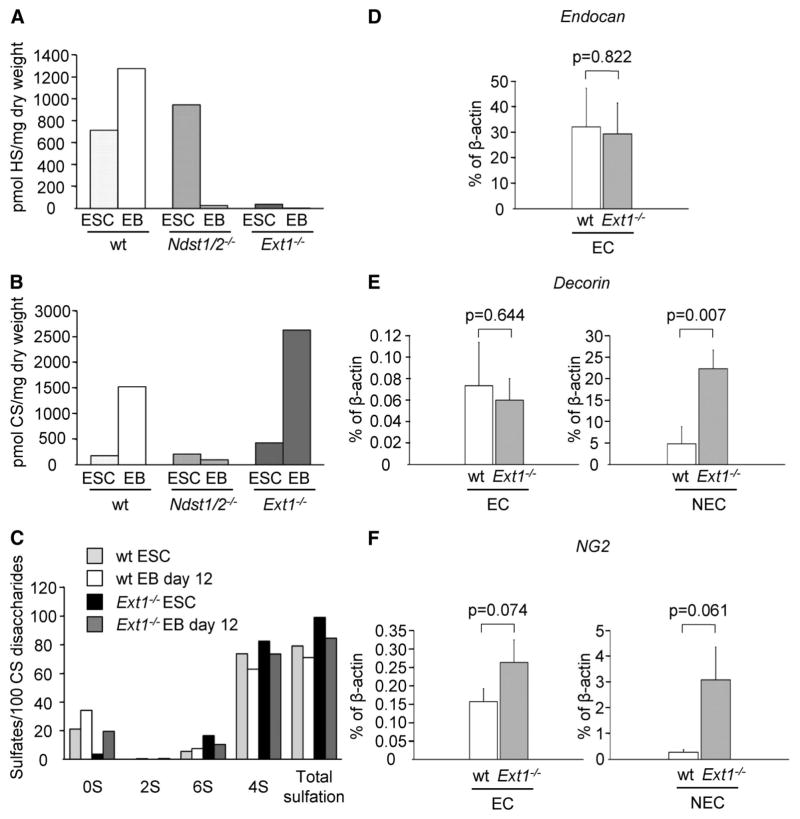

Ext1−/− EBs exhibit increased CS biosynthesis

As Ext1−/− EBs were unable to produce HS, but still formed angiogenic sprouts, we hypothesized that CS functionally could compensate for the lack of HS. The total amounts of CS and HS synthesized by ESCs and angiogenic EBs of the different genotypes were therefore determined. Both HS and CS synthesis were increased during the course of differentiation in wt cells, while there was a decrease in the amount of both types of GAGs in Ndst1/2−/− EBs compared to ESCs (Figure 3A–B). Accordingly, Ndst1/2−/− EBs may be regarded as null mutants for both HS and CS biosynthesis, providing an explanation for the markedly delayed formation of sprouts in these cultures (Figure 1G–H). The levels of HS produced by the Ext1−/− ESCs or EBs were at the limit of detection (Figure 3A) and therefore considered to be insignificant background signals, in agreement with the data presented in Figure 2. Notably, the total amounts of CS recovered were twice as high in Ext1−/− ESCs and EBs as compared to wt cells (Figure 3B). The detailed sulfation patterns of wt and Ext1−/−-derived CS revealed that in both cases the majority of CS disaccharide units were 4-O-sulfated. Also, there was no substantial difference between wt and Ext1−/− cells with regard to overall degree or pattern of sulfation of CS, as determined by disaccharide analysis (Figure 3C and Supplemental Figure III). Taken together, analysis of HS and CS produced by wt and Ext1−/− cells at different stages of differentiation showed that the loss of HS in vascularized Ext1−/− EB is compensated by a 2-fold increase in CS production.

Total amounts of HS produced by wt, Ndst1/2−/− and Ext1−/− ESCs and EBs quantified using the RPIP-HPLC method (A). Quantification of CS produced by wt, Ndst1/2−/− and Ext1−/− ES cells (B). The overall sulfate content of CS (C), specified according to type of substituent as total 2-O-sulfated (2S), total 6-O-sulfated (6S) and total 4-O-sulfated disaccharides (4S), demonstrate increased production of CS in Ext1−/− cultures, albeit with normal degree of sulfation. The average of two separate experiments is shown. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the CSPGs endocan (D), decorin (E), and NG2 (F) after isolation of CD31+ ECs from wt and Ext1−/− EBs. EC, CD31+ cells; NEC, non-endothelial (CD31−) cells.

Elevated decorin and NG2 mRNA levels in Ext1−/− EBs

The expression levels of core proteins and enzymes involved in CS biosynthesis were initially analyzed in endothelial cells as well as in non-endothelial cells isolated from both Ext1−/− and wt EBs using a qPCR screen (Supplemental Fig. IV, Supplemental Table I, and data not shown). Validation of the expression of selected genes was thereafter performed by additional qPCR analyses (Figure 3D–F). Endocan, known to carry CS, was found to be equally expressed in CD31-positive endothelial cells isolated from VEGFA-induced wt and Ext1−/− EBs, whereas no endocan mRNA was detected in the non-endothelial cell fraction (CD31-negative) (Figure 3D). In contrast, the expression levels of the CS-bearing PG core proteins decorin and NG2 were increased more than 5- and 10-fold, respectively, in non-endothelial cells isolated from Ext1−/− EBs as compared to wt (Figure 3E–F). Other genes linked to CS biosynthesis were expressed at equal levels in Ext1−/− and wt cultures (data not shown). These results demonstrate that the increased production of CS in Ext1−/− cultures is accompanied by increased expression of PG core proteins.

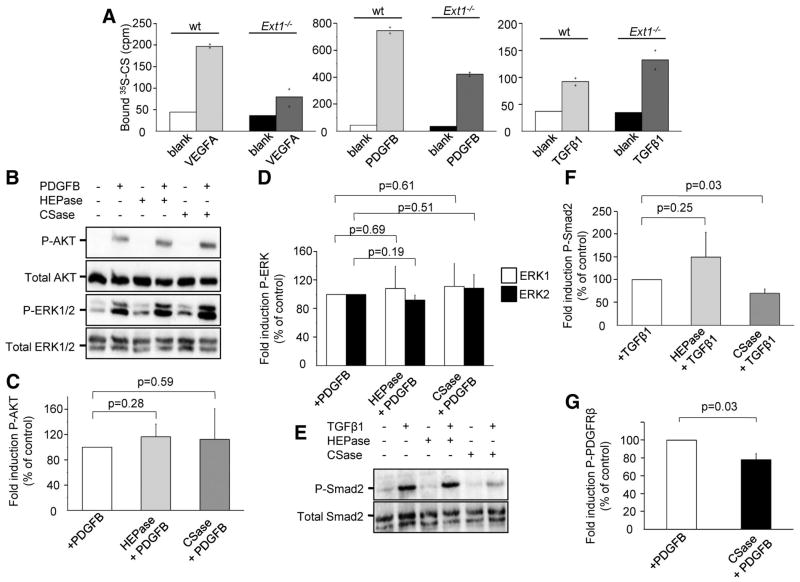

CS interacts with and supports PDGFB- and TGFβ-signaling

A standard nitrocellulose filter binding assay was employed to test interactions between Ext1−/−-derived CS and the angiogenic growth factors TGFβ1, PDGFB and VEGFA165. All three growth factors were shown to bind metabolically 35S-labeled CS isolated from wt and Ext1−/− EBs (Figure 4A). We next analyzed signaling pathways in endothelial cells (HUVECs) or smooth muscle cells (hAoSMCs) of human origin treated or not by CSase ABC or heparitinase III (HEPase) prior to growth factor stimulation, to degrade extracellular CS and HS. Supplemental Figure V shows that cell surface HS/CS degradation was efficient under these conditions. Phosphorylation of VEGFR2 and activation of downstream targets in HUVECs, as well as PDGFB signaling in hAoSMCs, were not significantly disturbed by degradation of GAGs under these conditions (Figure 4B–D and Supplemental Figure VIA). In contrast, treatment of hAoSMCs with CS-degrading enzymes before TGFβ stimulation significantly decreased the level of Smad2 phosphorylation by approximately 25% (Figure 4E–F); degradation of HS was without significant effects. Admittedly, the here performed enzymatic degradation of extracellular HS and CS, although efficient, is likely incomplete, providing an explanation for the small effects recorded on VEGFA- and PDGFB-signaling in HUVECs and hAoSMCs respectively. We therefore turned to the Ndst1−/− mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) model. Abramsson and co-workers have previously shown that PDGFB signaling in these cells, expressing normal levels of CS, is reduced due to reduced levels of functional HS 9. Using the Ndst1−/− MEF model, we could show that PDGFB signaling could be further reduced by degradation of CS by CSase treatment (Figure 4G and Supplemental Figure VIB), providing additional evidence for the involvement of CS in angiogenic growth factor signaling.

(A) VEGFA165, PDGFB, and TGFβ1 bind to 35S-labeled CS isolated from wt and Ext1−/− EBs. The graphs illustrate the mean of two measuring points. (B) Phospho-AKT (P-AKT) and phospho-ERK1/2 (P-ERK1/2) activation induced by PDGFB in hAoSMCs after treatment with HEPase or CSase. (C, D) Quantification of the results shown in (B). (E) Smad2 phosphorylation induced by TGFβ1 in hAoSMCs after treatment with HEPase or CSase. (F) Quantification of P-Smad2 after TGFβ1 stimulation. (G) Activation of PDGFRβ by PDGFB in Ndst1−/− MEFs. Treatment with CSase leads to reduced activation of the receptor. n=3 for all signaling experiments.

Discussion

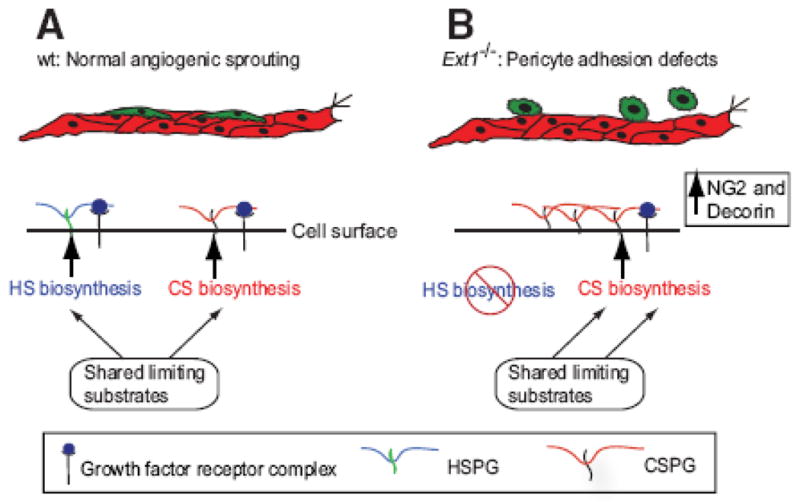

The present study demonstrates for the first time that angiogenic sprouting can occur in the absence of HS biosynthesis. Ext1−/− EBs, unable to synthesize HS but exhibiting increased CS biosynthesis, were accordingly shown to form vascular sprouts in response to VEGFA. The main morphological phenotypes detected in the Ext1−/− condition were increased formation of pericytes, accompanied by an increased extent of pericyte detachment from the vessel sprouts. Sprout formation in Ndst1/2−/− EBs was on the other hand severely compromised, and pericytes did not form in these cultures. This result is in agreement with the finding that differentiated Ndst1/2−/− EBs are effective “double knockouts” for both HS and CS (Figure 3). Thus, although sprout formation indeed is dependent on GAG function, our data suggest that selective loss of HS production in part can be compensated by increased CS biosynthesis. The fact that the CS-producing Ext1−/− EBs but not the GAG-null Ndst1/2−/− EBs supported angiogenesis, strongly argue for a functional overlap between HS and CS in sprouting angiogenesis (Figure 5). Importantly, these results challenge the view that HS is strictly required for all steps of the angiogenic process, and strengthen the notion that there is a broad selectivity for interactions between protein ligands and equally sulfated, yet distinct, HS and CS epitopes 12.

Model showing how increased biosynthesis of CSPGs as a result of blocked HS biosynthesis may support angiogenic growth factor signaling.

It is outside the scope of this study to identify the mechanism behind the increased CS biosynthesis in Ext1−/− EBs. However, HS and CS biosynthesis share some common substrates (UDP-sugars and the sulfate donor PAPS), and utilize the same tetrasaccharide linkage region for initiation of biosynthesis onto core proteins. A reduction in HS biosynthesis will thus likely result in more available substrates for CS biosynthesis, providing an explanation to the increased production of CS in Ext1−/− EBs.

The defect in pericyte attachment found in Ext1−/− EBs was mirrored at the level of TGFβ signaling and PDGFRβ phosphorylation. A trend was also seen for altered activation of AKT and ERK1/2 in response to PDGFB in Ext1−/− EBs. Dysregulated TGFβ and PDGFB signaling (Figure 1) offer highly plausible mechanisms for the observed loss in pericyte attachment in Ext1−/− EBs. TGFβ signaling has previously been shown to promote pericyte differentiation 24, and the increased TGFβ signaling may therefore explain the higher pericyte number in the Ext1−/− EBs. The Ext1−/− phenotype was not rescued by the addition of exogenous PDGFB or TGFβ1. Instead, both the number of pericytes and the extent of detachment were further increased by the exogenous addition of these growth factors (Supplemental Figure IB), emphasizing the need for regulated presentation of these factors, likely in the form of properly shaped and maintained extracellular concentration gradients.

The CS produced by the Ext1−/− EBs was capable of binding TGFβ, PDGFB, and VEGFA. Notably, the expression levels of CS biosynthetic enzymes were unchanged in these cultures, although the amounts of some of the CS-modified core proteins e.g. decorin and NG2 were increased, which may be linked to the increased production of CS. Decorin belongs to the family of small leucine rich PGs (SLRPs) and has been shown to regulate extracellular matrix organization as well as growth factor signaling 27–30. Indeed, decorin binds to PDGFB and may inhibit PDGFB-stimulated vascular smooth muscle cell function in a dose dependent manner28. Interestingly, the active form of TGFβ known to mediate the de novo induction of pericytes from the mesenchymal cell lineage during embryonic development also binds to decorin in the extracellular matrix 31. In addition, decorin has been shown to inhibit or stimulate angiogenesis dependent on the biological context32–35. NG2 has also been shown to play a role in pathological angiogenesis via interactions with anti-angiogenic factors as well as with FGF2 and different PDGFs36–38.

Our data furthermore suggest that CS is required for proper TGFβ signaling. The mechanisms underlying the sensitivity to loss of CS displayed in our analyses of TGFβ signaling is unclear (Figure 4). However, the fact that CSase treatment reduced TGFβ/TGFβR signaling in hAoSMCS suggests that CS could be engaged in ternary complexes together with growth factors and receptors to promote receptor complex assembly39, 40. Interestingly, TGFβ receptor III (TGFβRIII) or betaglycan is a “promiscuous” proteoglycan that has the capacity to carry either HS chains or CS chains, both HS and CS at the same time, or no GAG chains at all 41. The betaglycan protein core has further been shown to bind TGFβ and to act as a TGFβ co-receptor by facilitating TGFβRI/TGFβRII complex formation42, 43. The chemical nature of the GAG influences TGFβRIII activity 44 but the exact role of the different GAGs in TGFβRIII function is still not well understood. We suggest that disturbed balance between HS and CS production (as seen in Ext1−/− EBs) impacts the GAG composition of TGFβRIII and consequently alters signaling. Finally, using the Ndst1−/− MEF model, we could show that PDGFB signaling in a genetic background where HS biosynthesis but not CS biosynthesis is suppressed could be further reduced by CSase treatment (Figure 4G), providing evidence for a modulatory role of CS in PDGFB signal transduction.

Pathological conditions characterized by vessel immaturity, vessel excess or dysregulated growth factor production, are often accompanied by pericyte detachment. Pericyte detachment or other types of pericyte deficiencies have been shown to lead to increased vessel tortuosity and leakage, as well as to the formation of microaneurysms, with an increased risk for bleedings. Interestingly, metastatic spread of cancer may be facilitated by vessel instability at least in part due to lack of attached pericytes45, 46. Here, EXT1-deficiency and decreased HS production was accompanied by pericyte detachment from angiogenic sprouts. PDGFRβ signaling was decreased in the Ext1−/− EBs, which expressed increased levels of CS. We suggest that CS-dependent elevation of TGFβ signaling (Figure 1) may indirectly affect the cellular response to PDGFB.

It is tempting to speculate that the observed functional overlap between HS and CS may be relevant not only to angiogenic sprouting, but also to other complex morphogenetic processes influenced by GAG-binding growth factors. Tampering with HS biosynthesis could represent a possible way to target HS-protein interactions of pathophysiological significance. Efforts are indeed ongoing to evaluate GAG-mimetics or inhibition of HS biosynthesis for therapeutic purposes 47. However, the partial functional overlap between HSPGs and CSPGs demonstrated by the present study suggests that targeting of either HS or CS production alone may not be sufficient to efficiently inhibit angiogenesis. Further, inhibition of HS may depending on strategy also affect CS biosynthesis, as seen here with the 2-fold increase in CS biosyntheis in Ext1−/− EBs. Finally, simultaneous blocking of both HS and CS biosynthesis would probably also lead to severe side effects. At any rate, the close link between HS and CS biosynthesis, as well as their overlapping functions, should be kept in mind when considering future drug strategies to influence GAG-modulated biological processes.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Prof. Ulf Lindahl for helpful discussions.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This study was supported by grants to J.K., L.K. and L.C.W. from the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish Childhood Cancer Foundation, the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (project no A3 05:207g), the Human Frontiers in science program, the Wenner-Gren Foundations, the Magnus Bergvall’s Foundation, the Jeansson’s Foundations, the Selander’s Foundation, Gustaf V:s 80-årsfond, Polysackaridforskning AB and Uppsala University. J.D.E and J.R.B were supported by grant GM33063 from the National Institutes of Health, USA. O.S. and I.W. were supported by grants from the Wallenberg foundation, the Swedish Cancer Society and the Beijer foundation.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

O.S. owns options in the company Olink Biosciences, commercializing the PLA technology.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1161/atvbaha.111.240622

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.240622

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1161/atvbaha.111.240622

Article citations

Glycosaminoglycans' Ability to Promote Wound Healing: From Native Living Macromolecules to Artificial Biomaterials.

Adv Sci (Weinh), 11(9):e2305918, 10 Dec 2023

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 38072674 | PMCID: PMC10916610

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Regulation of morphogen pathways by a Drosophila chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan Windpipe.

J Cell Sci, 136(7):jcs260525, 11 Apr 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 36897575 | PMCID: PMC10113886

Plasma and Urine Free Glycosaminoglycans as Monitoring and Predictive Biomarkers in Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Prospective Cohort Study.

JCO Precis Oncol, 7:e2200361, 01 Feb 2023

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 36848607 | PMCID: PMC10309541

Endothelial glycocalyx in hepatopulmonary syndrome: An indispensable player mediating vascular changes.

Front Immunol, 13:1039618, 22 Dec 2022

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 36618396 | PMCID: PMC9815560

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Glycosyltransferases EXTL2 and EXTL3 cellular balance dictates heparan sulfate biosynthesis and shapes gastric cancer cell motility and invasion.

J Biol Chem, 298(11):102546, 28 Sep 2022

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 36181793 | PMCID: PMC9637574

Go to all (43) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

The interaction of heparan sulfate proteoglycans with endothelial transglutaminase-2 limits VEGF165-induced angiogenesis.

Sci Signal, 8(385):ra70, 14 Jul 2015

Cited by: 26 articles | PMID: 26175493

Lead inhibits the core protein synthesis of a large heparan sulfate proteoglycan perlecan by proliferating vascular endothelial cells in culture.

Toxicology, 133(2-3):159-169, 01 Apr 1999

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 10378482

Endothelial heparan sulfate proteoglycan. I. Inhibitory effects on smooth muscle cell proliferation.

Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol, 2(1):13-24, 01 Jan 1990

Cited by: 47 articles | PMID: 2137707

Interaction of angiogenic basic fibroblast growth factor with endothelial cell heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Biological implications in neovascularization.

Int J Clin Lab Res, 26(1):15-23, 01 Jan 1996

Cited by: 65 articles | PMID: 8739851

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NIGMS NIH HHS (4)

Grant ID: GM33063

Grant ID: R01 GM033063

Grant ID: R01 GM033063-17

Grant ID: R37 GM033063