Abstract

Free full text

Serum from patients with SLE instructs monocytes to promote IgG and IgA plasmablast differentiation

Abstract

The development of autoantibodies is a hallmark of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). SLE serum can induce monocyte differentiation into dendritic cells (DCs) in a type I IFN–dependent manner. Such SLE-DCs activate T cells, but whether they promote B cell responses is not known. In this study, we demonstrate that SLE-DCs can efficiently stimulate naive and memory B cells to differentiate into IgG- and IgA-plasmablasts (PBs) resembling those found in the blood of SLE patients. SLE-DC–mediated IgG-PB differentiation is dependent on B cell–activating factor (BAFF) and IL-10, whereas IgA-PB differentiation is dependent on a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL). Importantly, SLE-DCs express CD138 and trans-present CD138-bound APRIL to B cells, leading to the induction of IgA switching and PB differentiation in an IFN-α–independent manner. We further found that this mechanism of providing B cell help is relevant in vivo, as CD138-bound APRIL is expressed on blood monocytes from active SLE patients. Collectively, our study suggests that a direct myeloid DC–B cell interplay might contribute to the pathogenesis of SLE.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease characterized by multiorgan involvement and immunological abnormalities that include aberrant autoreactive B cell responses. In SLE, elevated levels of autoantibodies, particularly those recognizing double-stranded DNA, are considered to be pathogenic (Kotzin, 1996; Arbuckle et al., 2003), as autoantibody-derived immune complexes deposit in tissues and exacerbate SLE disease pathogenesis, such as lupus nephritis (Koffler et al., 1971).

The mechanisms underlying the failure to maintain B cell tolerance in SLE remain incompletely understood. There are multiple checkpoints during B cell development, maturation, and activation that have been demonstrated to be defective in mouse lupus models (Kuo et al., 1999; Grimaldi et al., 2001, 2002; Santulli-Marotto et al., 2001) as well as in SLE patients (Wardemann et al., 2003; Cappione et al., 2005; Yurasov et al., 2005, 2006). Thus, active SLE patients show elevated frequencies of autoreactive B cells in the new emigrant and mature B cell compartments (Pugh-Bernard et al., 2001; Yurasov et al., 2005, 2006). SLE patients in clinical remission continue to show higher numbers of autoreactive mature naive B cells, although at lower frequency than patients with active disease. Thus, the treatments do not seem to restore defective early B cell tolerance checkpoints in this disease. The frequency of polyreactive IgG+ memory B cells from untreated, active SLE patients seems to be similar to those of healthy controls, but at higher frequency of SLE, autoantigen-specific cells exist within this compartment in some patients (Mietzner et al., 2008). Altered tolerance check points have also been described in the lymphoid organs of SLE patients, as autoreactive B cells are allowed to undergo germinal center reaction in tonsils (Cappione et al., 2005). In addition, SLE patient blood is characterized by B cell lymphopenia and alterations in B cell subset composition. Thus, numbers of naive B cells are decreased, whereas the frequency of CD27− memory B cells, plasmablasts (PBs), and plasma cells (PCs) is increased (Odendahl et al., 2000; Arce et al., 2001; Wei et al., 2007). However, the mechanisms underlying these alterations are not well understood.

DCs play an important role in B cell activation (Dubois et al., 1997; Jego et al., 2003) as well as in B cell tolerance (Pascual et al., 2003; Banchereau et al., 2004). Constitutive deletion of DCs in a mouse lupus model led to disease improvement (Teichmann et al., 2010), whereas their deletion in a nonautoimmune model resulted in autoimmunity (Ohnmacht et al., 2009). DCs circulate at very low levels in the blood of SLE patients (Blanco et al., 2001), and thus their ex vivo functional properties are difficult to study. Monocytes represent the most abundant circulating pool of APCs and also serve as precursors of macrophages and DCs. Indeed, blood monocytes from pediatric SLE patients act as DCs, as they induce the proliferation of allogeneic naive CD4+ T cells (Blanco et al., 2001). Furthermore, exposure of healthy monocytes to SLE serum results in the generation of cells with DC morphology and functions. This DC-inducing property of SLE serum is mainly mediated through IFN-α (Blanco et al., 2001). However, SLE serum contains additional factors that might potentiate healthy monocyte differentiation into DCs (Gill et al., 2002) and eventually promote autoreactive B cell responses in patients.

In this study, we have explored the capability of SLE serum–induced monocyte-derived DCs (SLE-DCs) to promote B cell responses. Our data demonstrate that SLE-DCs are very efficient at inducing naive and memory B cell differentiation into IgG- and particularly IgA-secreting PBs through conventional as well as novel pathways. Furthermore, blood monocytes of SLE patients showed similar functional characteristics to those of SLE-DCs. Understanding the mechanisms underlying SLE-DC–mediated B cell responses might disclose novel therapeutic targets to treat this disease.

RESULTS

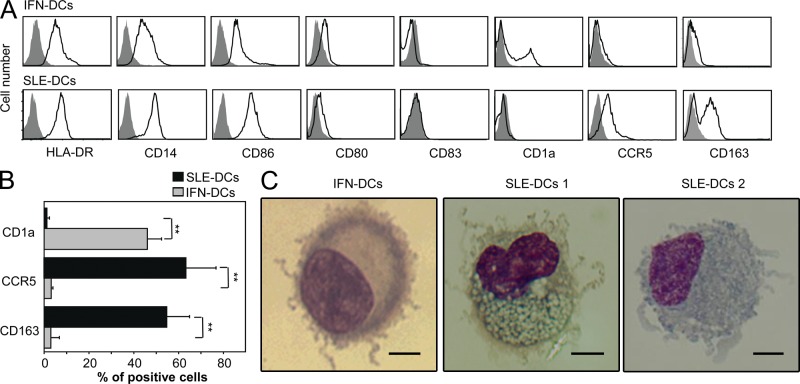

Phenotype and morphology of SLE-DCs

SLE serum induces the differentiation of healthy monocytes into DCs in an IFN-α–dependent manner (Blanco et al., 2001). Thus, we first compared the phenotype of DCs generated by culturing healthy monocytes with either SLE serum (SLE-DCs) or IFN-α plus GM-CSF (IFN-DCs). Both SLE-DCs and IFN-DCs expressed comparable levels of HLA-DR and CD80, but SLE-DCs expressed higher levels of CD14 and CD86 (Fig. 1 A). Although this phenotype was consistent regardless of the method used to purify monocytes, neither IFN-DCs nor SLE-DCs expressed significant levels of CD83 unless monocytes were obtained by CD14 positive selection, as previously reported (Gill et al., 2002). Notably, whereas a fraction of SLE-DCs expressed CCR5 and CD163, IFN-DCs expressed low levels of CD163. Additionally, a fraction of IFN-DCs expressed CD1a (Fig. 1 A); this marker was absent on SLE-DCs. Fig. 1 B shows the percentage of CD1a+, CCR5+, and CD163+ cells in IFN-DCs and SLE-DCs.

Phenotype and morphology of IFN-DCs and SLE-DCs. (A) Surface phenotype of IFN-DCs and SLE-DCs. Closed gray histograms indicate isotype control, and black line histograms indicate markers of interest. (B) Summarized data (mean ± SD in A) for CD1a, CCR5, and CD163 expression. Student’s t test: **, P < 0.01. (C) Giemsa staining of IFN-DCs and SLE-DCs generated with sera from SLE patients. Bars, 2.5 µm. In A and C, experiments using sera from 20 SLE patients and monocytes from 12 healthy donors showed similar results.

Giemsa staining of SLE-DCs showed the presence of dendrites. As compared with the fine projections of dendrites found in IFN-DCs, SLE-DCs had a mixture of fine and thicker dendrites (SLE-DCs 1 and SLE-DCs 2) and contained larger numbers of cytoplasmic vacuoles (Fig. 1 C). Thus, SLE-DCs differ from IFN-DCs with respect to phenotype and morphology. This raised the question as to whether the two types of DCs possess distinct functions in the controlling of B cell responses.

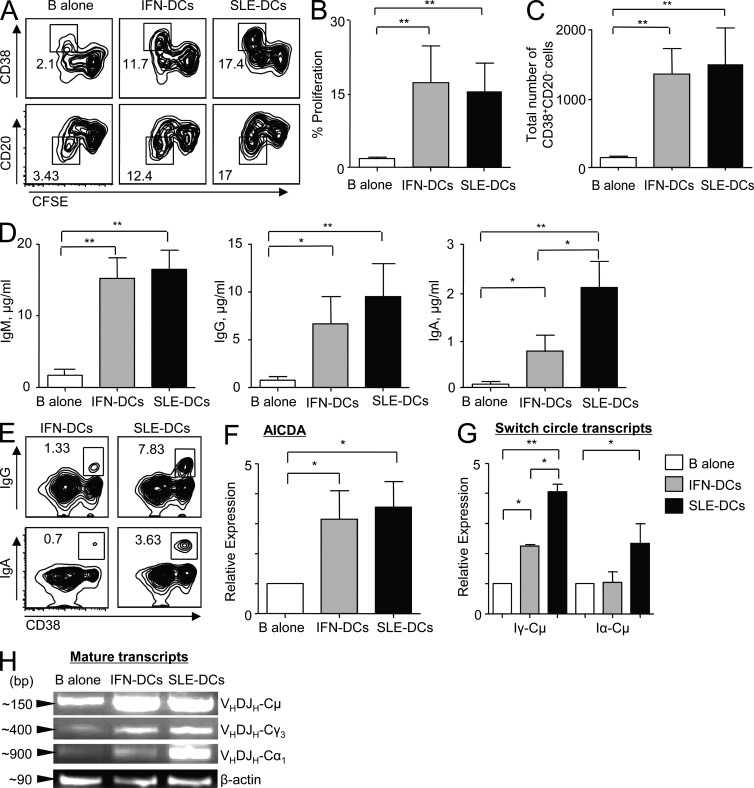

SLE-DCs induce naive B cells to differentiate into IgG- and IgA-secreting PBs

To test the role of SLE-DCs on B cell responses, purified naive B cells (CD19+IgD+CD27−) were cultured with or without DCs in the presence of IL-2 and CpG. It is known that CpG promotes memory B cell proliferation and IgM production (Krieg et al., 1995; Bernasconi et al., 2002). CpG can also activate human naive B cells (He et al., 2004; Huggins et al., 2007; Jiang et al., 2007), resulting in enhanced proliferation and survival. However, CpG alone does not induce IgG or IgA class switching (He et al., 2004; Jiang et al., 2007). IL-2 supports human B cell proliferation and Ig production (Yoshizaki et al., 1982; Arpin et al., 1995).

SLE-DCs and IFN-DCs were equally effective at enhancing the proliferation of naive B cells (Fig. 2, A and B). They also equally supported the differentiation of PBs (Fig. 2, A and C), as measured by up-regulation of CD38 and down-regulation of CD20 expression. Although IFN-DCs and SLE-DCs were equally potent at inducing IgM secretion, SLE-DCs were more potent than IFN-DCs at inducing naive B cells to secrete switched isotypes, especially IgA (Fig. 2 D). This was further confirmed by intracellular Ig staining (Fig. 2 E). The lower capability of IFN-DCs to promote IgG and IgA was not caused by a defect in AID (activation-induced cytidine deaminase) expression, as AICDA expression levels were similar in B cells co-cultured with either type of DCs (Fig. 2 F). RT-PCR analysis of switch circle transcripts revealed that naive B cells co-cultured with either IFN-DCs or SLE-DCs had significantly increased levels of Iγ-Cμ (Fig. 2 G). Naive B cells co-cultured with SLE-DCs but not IFN-DCs showed increased levels of IgA class switching as measured by Iα-Cμ transcripts. Additionally, B cells co-cultured with SLE-DCs showed higher levels of the mature transcripts VHDJH-CHγ3 and VHDJH-CHα1 than B cells co-cultured with IFN-DCs (Fig. 2 H). Compared with B cells alone, IFN-DCs also increased expression of VHDJH-CHμ and VHDJH-CHγ3 transcripts. Collectively, SLE-DCs display a potent capability to enhance naive B cell differentiation into IgG- and IgA-PBs. Although SLE sera contain elevated levels of IL-21 (0.05–2 ng/ml; Kang et al., 2011), 1–100 ng/ml of exogenous IL-21 did not further enhance the SLE-DC–mediated naive B cell responses in the presence of IL-2 and CpG (not depicted).

IFN-DCs and SLE-DCs induce naive B cell differentiation into PBs. DCs were co-cultured with CFSE-labeled naive B cells for 6 or 12 d in the presence of 50 nM CpG and 20 U/ml IL-2. (A) CD38 and CD20 expression as well as CFSE dilution were assessed after 6 d. Experiments using sera from 36 patients and monocytes from 12 healthy controls showed similar results. (B and C) Proliferation (B) and PB differentiation (C) on day 6. (D) Total Ig assayed by ELISA on day 12. In B–D, combined data (mean ± SD) from experiments using sera from 19 patients and cells from 8 healthy controls are presented. (E) Intracellular Ig staining on day 6. Experiments using sera from six patients and monocytes/B cells from four healthy controls showed similar results. (F) RNA was harvested after 6 d of DC and naive B cell co-culture in the presence of 50 nM CpG and 20 U/ml IL-2. RT-PCR was performed to measure AICDA expression. Representative data are from three independent experiments with triplicate assay using sera from eight patients and monocytes from three healthy controls. Individual experiments showed similar results. (G) RNA was harvested after 4 d of co-culture for γ switch circles and after 5 d of co-culture for α switch circles. RT-PCR was performed to measure the relative expression of each switch circle transcript. (F and G) Combined data (mean ± SD) from experiments using sera from four SLE patients and monocytes and B cells from three healthy controls are presented. (H) RNA was harvested after 6 d of DC and naive B cell co-cultures in the presence of 50 nM CpG and 20 U/ml IL-2. The products of an RT-PCR reaction were run on an agarose gel. Three independent experiments using sera from five patients and monocytes and B cells from five healthy controls showed similar results. Student’s t test: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

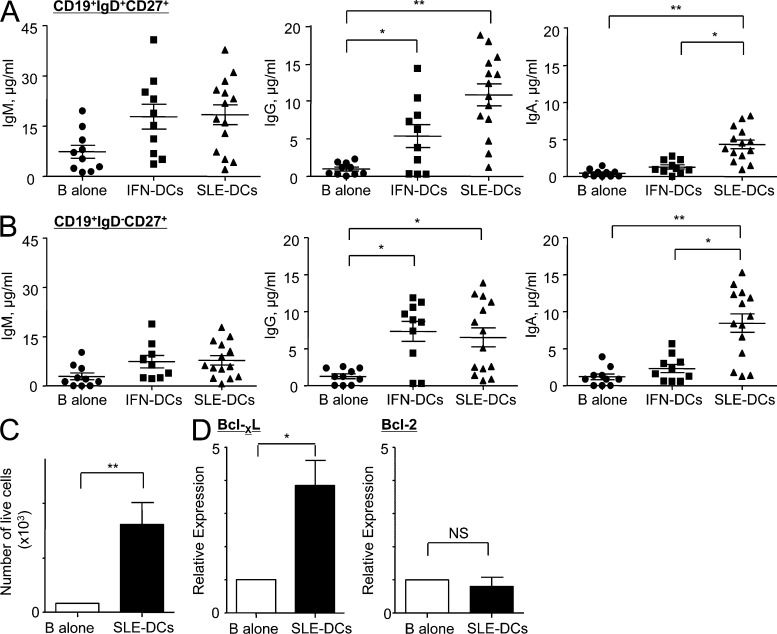

SLE-DCs enhance IgG and IgA secretion from memory B cells and support PB survival

We then tested whether SLE-DCs could promote the differentiation of both CD19+IgD+CD27+ and CD19+IgD−CD27+ memory B cells into PBs. As shown in Fig. 3 A, SLE-DCs efficiently induced IgD+CD27+ B cell differentiation into PBs (CD20−CD38+) secreting IgG and IgA. In particular, SLE-DCs were more efficient than IFN-DCs at inducing IgA-secreting B cell responses. Similar to IgD+CD27+ B cells, IgD−CD27+ memory B cells co-cultured with SLE-DCs secreted increased levels of IgG and particularly IgA (Fig. 3 B). Thus, SLE-DCs can efficiently promote both naive and memory B cell responses.

SLE-DCs enhance CD19+IgD−CD27+ and CD19+IgD+CD27+ B cell responses by promoting IgG- and IgA-secreting B cell responses. (A and B) CD19+IgD+CD27+ (A) or CD19+IgD−CD27+ B cells (B) were co-cultured with DCs for 12 d in the presence of 20 U/ml IL-2. The amount of total Ig was assayed by ELISA. Combined data (mean ± SD) from experiments using sera from 14 patients and cells from 10 healthy controls are presented. ANOVA test: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. (C) FACS-sorted PBs (CD19lowCD20−CD38+) were co-cultured with SLE-DCs in the presence of 20 U/ml IL-2. The viability of PBs was measured after 6 d of co-culture by Trypan blue exclusion method. Combined data (mean ± SD) from experiments using sera from 10 patients and monocytes and B cells from 6 healthy donors are presented. (D) RNA was harvested after 2 d. Relative expression of Bcl-XL and Bcl-2 was determined by RT-PCR. Combined data (mean ± SD) from experiments using sera from six patients and monocytes and B cells from five healthy controls are presented. Student’s t test: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

We next tested the effect of SLE-DCs on PB survival. PBs were generated by co-culturing purified total B cells and conventional monocyte-derived IL-4–DCs (monocytes cultured with GM-CSF and IL-4). These PBs were composed of IgM- (~35%), IgG- (~37%), and IgA-PBs (~16%), as measured by surface Ig staining (not depicted). FACS-sorted total PBs (CD20−CD38+) were further cultured with or without SLE-DCs in the presence of IL-2 only. SLE-DCs enhanced the number of viable PBs by more than sevenfold (Fig. 3 C) and resulted in enhanced Ig secretion (not depicted). PBs exposed to SLE-DCs displayed increased levels of Bcl-XL, whereas Bcl-2 levels were not altered (Fig. 3 D). Thus, SLE-DCs can enhance B cell responses by promoting the differentiation of naive and memory B cells into PBs and by supporting PB survival and Ig secretion.

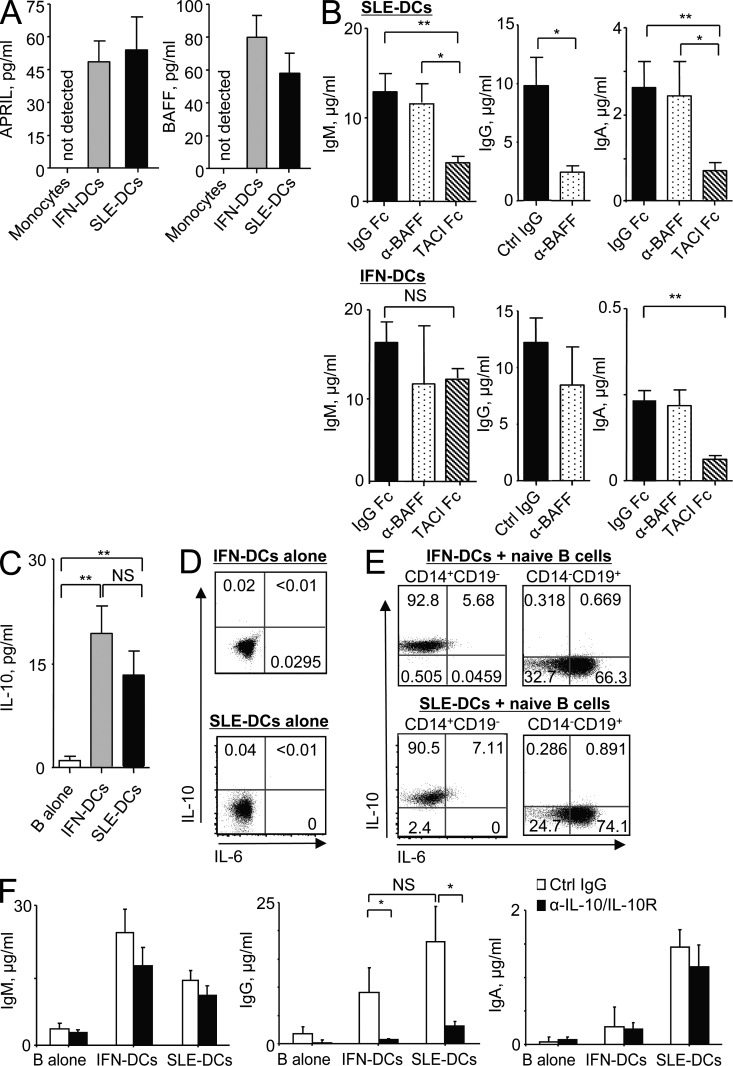

SLE-DC–mediated IgG and IgA responses are differentially regulated by B cell–activating factor (BAFF)/IL-10 and a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL), respectively

To understand the mechanisms whereby SLE-DCs promote IgG and IgA secretion, we tested the effects of BAFF (TNFSF13B) and APRIL (TNFSF13) on naive B cells. Both BAFF and APRIL support B cell survival as well as Ig class switching (Litinskiy et al., 2002; Xu et al., 2007). Furthermore, SLE patient serum displays elevated levels of BAFF and APRIL (Cheema et al., 2001; Koyama et al., 2005). Fig. 4 A shows that IFN-DCs and SLE-DCs, but not monocytes from healthy donors, constitutively secrete both APRIL and BAFF. In addition, SLE serum up-regulates BAFF and APRIL gene expression in monocytes in a type I IFN–dependent and –independent manner, respectively (unpublished data).

BAFF/IL-10 and APRIL secreted from SLE-DCs contribute to IgG and IgA responses, respectively. (A) BAFF and APRIL secreted by monocytes, IFN-DCs, and SLE-DCs were measured by ELISA after 24-h culture in serum-free media. Combined data (mean ± SD) from experiments using sera from 10 SLE patients and monocytes from 8 healthy controls are presented. (B) Naive B cells were co-cultured with SLE-DCs or IFN-DCs for 12 d in the presence of 10 µg/ml control IgG, anti-BAFF, or TACI-Fc fusion protein. Ig production was detected by ELISA. Combined data (mean ± SD) from experiments using SLE-DCs generated with sera from 14 SLE patients and cells from 8 healthy controls are presented. For both SLE-DCs and IFN-DCs, monocytes from eight healthy controls were used. (C) IFN-DCs and SLE-DCs were co-cultured with naive B cells for 2 d. IL-10 levels in the supernatants were quantified by ELISA. Combined data (mean ± SD) from experiments using sera from eight SLE patients and cells from six healthy controls are presented. (D) IFN-DCs (top) and SLE-DCs (bottom) were cultured for 24 h and stained for intracellular IL-10 and IL-6. (E) After 24-h co-culture of naive B cells and IFN-DCs (top) or SLE-DCs (bottom), both DCs (gated on CD14+CD19− cells) and B cells (gated on CD14−CD19+ cells) were stained for intracellular expression of IL-6 and IL-10. In D and E, experiments using four patient sera and cells from four healthy donors showed similar results. (F) IFN-DCs and SLE-DCs were co-cultured with naive B cells in the presence of 10 µg/ml control IgG or anti–IL-10/anti–IL-10R for 12 d. Ig production was measured by ELISA. Combined data (mean ± SD) from experiments using sera from 12 SLE patients and cells from 8 healthy controls are presented. In B and F, 50 nM CpG and 20 U/ml IL-2 were added to the cultures. Student’s t test: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

To test the effects of DC-derived BAFF and APRIL on naive B cell responses, anti-BAFF antibody and TACI-Fc were added to the 12-d co-culture of DCs and naive B cells in the presence of IL-2 and CpG. Anti-BAFF antibody neutralizes only BAFF, whereas TACI-Fc neutralizes both BAFF and APRIL. Interestingly, anti-BAFF antibody reduced the levels of IgG produced in co-cultures, whereas TACI-Fc reduced both IgM and IgA levels (Fig. 4 B, top). In contrast, neither anti-BAFF antibody nor TACI-Fc significantly altered the Ig secretion of naive B cells co-cultured with IFN-DCs (Fig. 4 B, bottom). The effect of TACI-Fc or BCMA-Fc on IgG responses could not be assessed because these reagents were recognized by the anti–human IgG antibody used in the ELISA. The amount (10 µg/ml) of anti-BAFF and recombinant proteins used in this study was predetermined in separate experiments (Fig. S1). 10 µg/ml TACI-Fc efficiently decreased IgM and IgA secretion from B cells (Fig. S1 A, left and right). 10 µg/ml anti-BAFF also resulted in the least amount of IgG production (Fig. S1 A, middle). In addition, anti-BAFF or TACI-Fc did not significantly decrease SLE-DC–mediated B cell proliferation (Fig. S1 B) but decreased the total number of B cells acquired at the end of cultures (Fig. S1 C).

Along with BAFF and APRIL, DCs can secrete other cytokines providing B cell help, such as IL-10 and IL-6. Supernatants from co-cultures of naive B cells with the two types of DCs contained similar levels of IL-10 (Fig. 4 C). To access the sources of IL-10 in the co-culture, cells were stained for intracellular cytokine expression. Fig. 4 D shows that neither IFN-DCs nor SLE-DCs alone expressed IL-10 or IL-6. However, a majority of the two types of DCs co-cultured for 24 h with naive B cells expressed IL-10 but not IL-6 (Fig. 4 E, left). Large fractions of B cells co-cultured with either IFN-DCs or SLE-DCs expressed IL-6 but not IL-10 (Fig. 4 E, right). Thus, IL-10 in the co-culture supernatants (Fig. 4 C) is mainly secreted from DCs.

To test the roles of IL-10 in naive B cell responses induced by the two DC types, anti–IL-10 and anti–IL-10R antibodies were added to the co-culture of DCs and naive B cells in the presence of IL-2 and CpG. Neutralizing IL-10 decreased IgG level induced by both DC types (Fig. 4 F). Blocking IL-10 did not significantly alter IgM- or IgA-secreting B cell responses. Thus, SLE-DC–mediated enhanced IgG secretion is largely dependent on both BAFF (Fig. 4 B) and IL-10 (Fig. 4 F), whereas secretion of IgM and IgA mainly depends on APRIL with or without BAFF (Fig. 4 B). Blocking BAFF did not significantly alter the secretion of IgG from the co-culture of IFN-DCs and naive B cells (Fig. 4 B, bottom). Combining anti-BAFF with either TACI-Fc or anti–IL-10 did not result in any synergistic inhibition of IgA or IgG production, respectively, in the co-cultures of naive B cells and SLE-DCs (not depicted). Blocking IL-6 with anti–IL-6 and IL-6R antibodies did not significantly alter IgG responses. This might be because of the fact that anti–IL-6/IL-6R cannot efficiently block intracellularly expressed IL-6 that is used by B cells (Burdin et al., 1995).

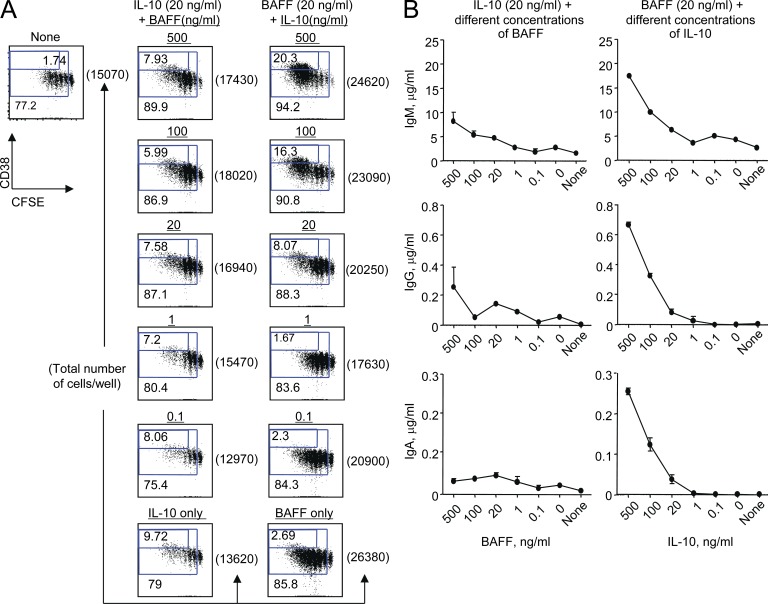

To further explore the roles of BAFF and IL-10 in naive B cell responses, BCR-activated naive B cells were cultured with combinations of exogenous IL-10 and BAFF in the presence of IL-2 and CpG. In the presence of 20 ng/ml IL-10, BAFF did not show significant effects on naive B cell differentiation into PBs (Fig. 5 A), but the numbers of B cells acquired on day 6 were slightly increased by the increasing amounts of BAFF added to the cultures. This suggests that BAFF can support B cell survival (Stohl et al., 2003; Schneider, 2005). In contrast to BAFF, IL-10 was able to enhance PB differentiation in a dose-dependent manner. Consequently, the amounts of Igs secreted from B cells were mainly dependent on IL-10 added to the culture (Fig. 5 A). IL-10 and BAFF did not show any synergistic effects on PB differentiation. Although IL-10 also enhanced IgM and IgA secretion from BCR-activated naive B cells (Fig. 5 B), blocking IL-10 in the co-culture of naive B cells and SLE-DCs resulted in only slightly decreased levels of IgM and IgA (Fig. 4 F). This supports the important roles of APRIL without or with BAFF in the enhanced IgM and IgA responses, which were mediated by SLE-DCs.

IL-10 promotes naive B cell differentiation into PBs and Ig secretion, whereas BAFF supports B cell survival. (A) 104/well BCR-activated CFSE-labeled naive B cells were cultured for 6 d in the presence of different concentrations of IL-10 and BAFF. Proliferation and PB differentiation were assessed by FACS. (B) On day 12, total Ig in the supernatants was assessed by ELISA. Error bars indicate mean ± SD of triplicate assay. Representative data from two independent experiments using cells from two healthy controls are presented. Both experiments showed similar results. In all experiments, 20 U/ml IL-2 and 50 nM CpG were added to the culture.

SLE-DCs trans-present CD138-bound APRIL to B cells to enhance IgA responses

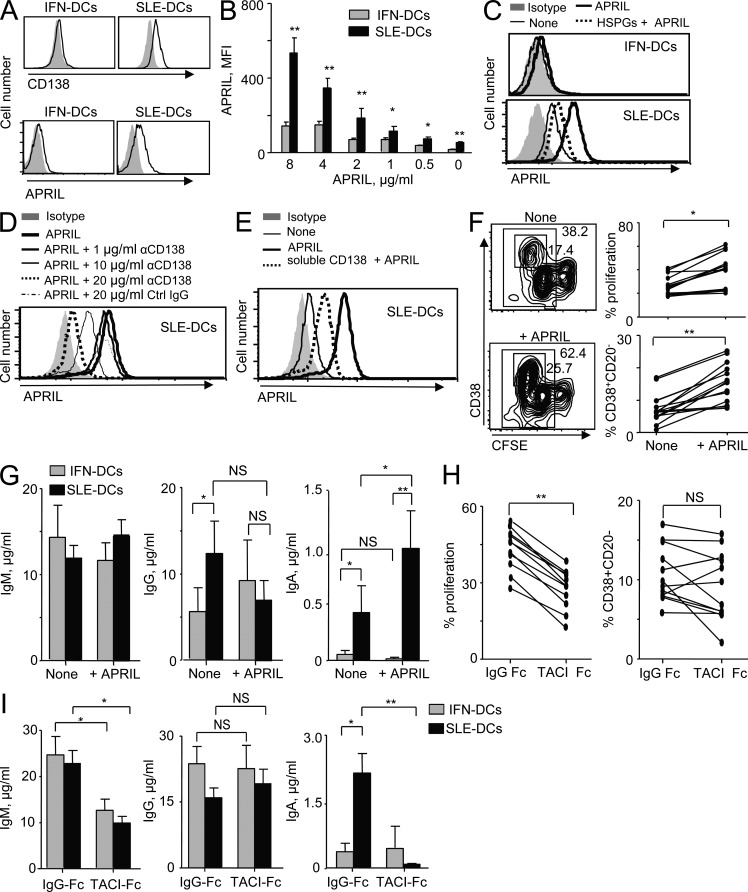

Although SLE-DCs express APRIL (Fig. 4 A), the amount of soluble APRIL is small compared with what is found in SLE serum (Cheema et al., 2001; Koyama et al., 2005). This led us to consider that APRIL might remain cell bound. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs; Hendriks et al., 2005; Ingold et al., 2005; Moreaux et al., 2009), such as syndecan-1 (CD138), are expressed on PCs and bind APRIL. Indeed, we found that SLE-DCs but not IFN-DCs express CD138 (Fig. 6 A, top) as well as membrane-bound APRIL (Fig. 6 A, bottom). Accordingly, SLE-DCs but not IFN-DCs could efficiently capture and display exogenous APRIL on their surface in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6 B). This binding is specific, as preincubation of APRIL with HSPGs diminished the binding of APRIL to the surface of DCs (Fig. 6 C, bottom). IFN-DCs did not express significant levels of surface CD138 (Fig. 6 A), and thus the preincubation of APRIL with HSPGs did not alter the surface APRIL expression (Fig. 6 C, top). Furthermore, treatment of SLE-DCs with anti-CD138 antibody but not with an isotype control antibody resulted in decreased binding of exogenous APRIL to the surface of SLE-DCs (Fig. 6 D). Consequently, preincubation of APRIL with soluble CD138 resulted in decreased binding of exogenous APRIL to these cells (Fig. 6 E). More than 10 µg/ml of soluble CD138 did not further enhance the inhibition of APRIL binding to the cells. IFN-α did not induce CD138 expression on monocytes, as IFN-DCs do not express CD138 (Fig. 6 A). Thus, we conclude that SLE serum induces CD138 expression on SLE-DCs in an IFN-independent manner. This may allow SLE-DCs to trans-present APRIL to promote B cell responses in SLE.

SLE-DCs express surface CD138 that trans-presents APRIL to B cells to enhance IgA-secreting B cell responses. (A) CD138 (top) and APRIL (bottom) expression on the surface of DCs. Closed gray histograms indicate isotype control antibody, and black line histograms indicate anti-CD138 (top) and anti-APRIL (bottom) antibody. Experiments using sera from 10 patients and monocytes from 16 healthy donors showed similar results. (B) Exogenous APRIL captured on the surface of DCs was determined by flow cytometry. Combined data (mean ± SD) from experiments using SLE-DCs made with sera from eight patients and four healthy controls are presented. (C) A competition assay was performed using 100 µg/ml HSPGs 2 h before the addition of APRIL to the DCs. Experiments using SLE-DCs made with sera from eight patients and four healthy controls showed similar results. (D) SLE-DCs were incubated with different concentrations of anti-CD138 antibody for 30 min and loaded with 2 µg/ml APRIL for 30 min. Cells were then stained with anti-APRIL antibody. (E) Competition assay with 10 µg/ml of soluble CD138. In C and D, experiments using SLE-DCs made with sera from four patients and four healthy controls showed similar results. (F) SLE-DCs were either preloaded (+APRIL) or unloaded (−APRIL) with APRIL and then washed before co-culture with naive B cells. Differentiation and proliferation were measured (left). Combined data from experiments (right) using sera from 12 patients and cells from 6 healthy donors are presented. (G) Total Ig levels (mean ± SD) in F. (H) SLE-DCs were preloaded with APRIL and then incubated for 30 min with either 10 µg/ml TACI-Fc or IgG-Fc. Before co-culture with naive B cells, DCs were washed twice. Differentiation and proliferation were measured. Each line represents the data generated with sera from 12 patients and cells from 5 healthy donors. (I) Total Ig levels (mean ± SD) in H. In F–I, 50 nM CpG and 20 U/ml IL-2 were added to the cultures. Student’s t test: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

To test whether such membrane-bound APRIL is functional, SLE-DCs were exposed to exogenous APRIL for 30 min, washed out, and co-cultured with naive B cells in the presence of IL-2 and CpG. APRIL-fed SLE-DCs resulted in enhanced naive B cell proliferation (Fig. 6 F, left and top right) and PB differentiation (Fig. 6 F, left and bottom right). In addition, APRIL-fed SLE-DCs displayed an enhanced ability to induce IgA but not IgG or IgM secretion by activated naive B cells (Fig. 6 G). These findings were further established by blocking membrane-bound APRIL with TACI-Fc (Fig. 6, H and I). APRIL-fed DCs were incubated with TACI-Fc for 30 min and washed to remove unbound TACI-Fc before they were co-cultured with naive B cells. TACI-Fc decreased the proliferation of naive B cells (Fig. 6 H, left) without significantly affecting PB differentiation (Fig. 6 H, right). However, TACI-Fc decreased both IgM and IgA responses without affecting IgG (Fig. 6 I).

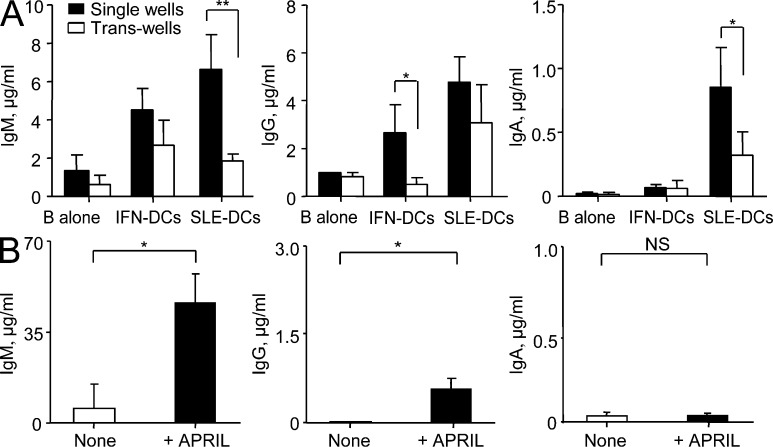

Transwell experiments further confirmed the importance of cell–cell contact for SLE-DC–mediated IgM and IgA secretion but not for IgG secretion (Fig. 7 A). Addition of soluble APRIL directly to activated naive B cells resulted in modestly increased proliferation and PB differentiation (Fig. 7 B). It also increased IgM and IgG secretion, without affecting that of IgA (Fig. 7 B). Collectively, our data demonstrates that trans-presentation of APRIL through CD138 is critical for SLE-DCs to promote IgM and particularly IgA responses.

SLE-DC and B cell interaction is important for SLE-DC–mediated IgM- and IgA-secreting B cell responses. (A) APRIL-fed IFN-DCs and SLE-DCs were loaded into the upper chamber of transwell plates. Naive B cells were added into the lower chamber of the transwell plates, and the cells were co-cultured for 12 d in the presence of 50 nM CpG and 20 U/ml IL-2. Total IgM, IgG, and IgA in the culture supernatants were measured by ELISA. Combined data (mean ± SD) from experiments using sera from seven SLE patients and monocytes and B cells from four healthy controls are presented. (B) Naive B cells were cultured without or with 2 µg/ml APRIL trimers in the presence of 50 nM CpG and 20 U/ml IL-2 for 12 d. Ig production was measured by ELISA. Combined data (mean ± SD) from experiments using B cells from eight healthy donors are presented. Student’s t test: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

SLE patients exhibit high numbers of IgG- and IgA-PBs in blood

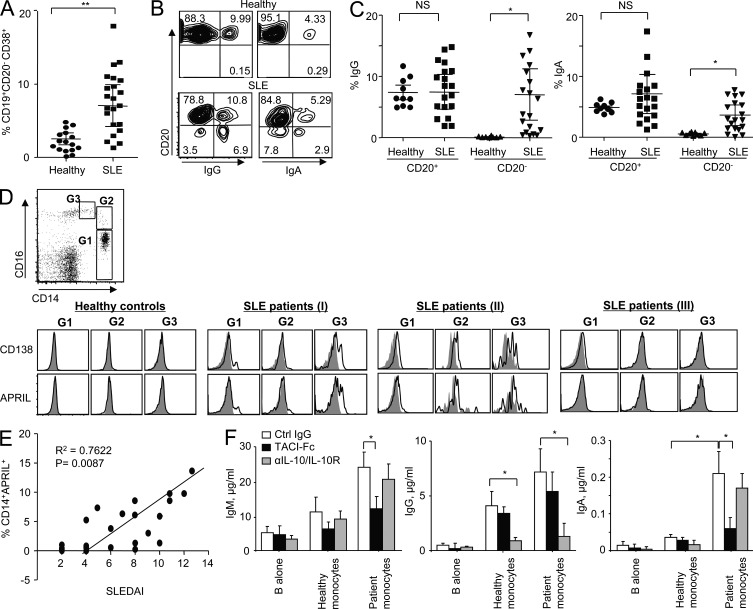

To assess the in vivo relevance of our findings, we characterized the mature B cell and PB compartments in the blood of SLE patients and healthy controls. The presence of expanded PC precursors in the blood of pediatric and adult SLE patients (Odendahl et al., 2000; Arce et al., 2001) and elevated serum IgA and IgG levels in SLE patients have been described earlier (Conley and Koopman, 1983; Lin and Li, 2009). As shown in Fig. 8 A, SLE patients displayed expanded CD19lowCD20−CD38+ PBs in their blood compared with healthy individuals. This expansion of PBs was accounted for by isotype-switched PBs (Fig. 8, B and C). Healthy individuals displayed IgG+ and IgA+ B cells, but most of the isotype-switched B cells were CD20+ (Fig. 8 B). In contrast, SLE patients displayed significant numbers of CD20−IgG+ and CD20−IgA+ PBs in their blood. Experiments performed with multiple donors are summarized in Fig. 8 C. The percentage of IgM+ PBs in patients was low (<1% of total CD19+ B cells). Thus, SLE patients show increased numbers of circulating IgG+ and IgA+ PB.

SLE patient monocytes express CD138 and can trans-present APRIL to B cells to expand IgA+ and IgG+ PBs. PBMCs were isolated from healthy controls and SLE patients. (A) Percentage of CD19lowCD20−CD38+ cells was assessed by flow cytometry. Combined data (mean ± SD) from 16 healthy controls and 22 SLE patients are presented. (B) Surface Ig on the CD19lowCD20− populations. Representative data from a total of 16 healthy controls and 22 SLE patients are presented. Individual experiments showed similar results. (C) Combined data (mean ± SD) from 10 healthy controls and 20 SLE patients. ANOVA test: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. (D, top) Gating strategy for blood monocytes. (bottom) Expression of CD138 and APRIL on the surface of monocyte subsets in the blood of healthy controls and SLE patients. Closed gray histograms indicate isotype control antibody, and black line histograms indicate anti-CD138 (first row) and anti-APRIL (second row) antibody. Representative data from experiments using blood from 6 healthy donors and 14 SLE patients are presented. (E) Correlation between the percentage of APRIL+ total monocytes and SLEDAI. Data from experiments using 20 patients are summarized. (F) Naive B cells were co-cultured for 12 d with patient monocytes in the presence of 10 µg/ml antibodies. 50 nM CpG and 20 U/ml IL-2 were added to the co-culture. Monocytes were incubated with 10 µg/ml TACI-Fc for 30 min and washed twice before adding to the culture. Total Ig levels were assessed by ELISA. Combined data (mean ± SD) from experiments using sera from 11 patients and cells from 6 healthy donors are presented. Student’s t test: *, P < 0.05.

SLE monocytes express CD138 and trans-present membrane-bound APRIL to promote IgA responses

Subsets of monocytes (G1, CD14highCD16−; G2, CD14highCD16low; and G3, CD14lowCD16high; Fig. 8 D, top) from SLE patients and healthy controls were stained for the surface expression of CD138 and APRIL. None of the three subsets of monocytes from healthy donors expressed either of these molecules on their surface (Fig. 8 D, bottom left). In contrast, monocytes from SLE patients showed three different patterns of surface CD138 and APRIL expression (Fig. 8 D, bottom right three panels): only a fraction of monocytes (I), all populations of monocytes (II), and none (III). More importantly, we found that the percentage of APRIL+ monocytes correlates with disease activity as measured by the SLE disease activity index (SLEDAI; Fig. 8 E). Furthermore, monocytes were able to induce naive B cells to isotype switch and to secrete Igs. Blocking membrane-bound APRIL with TACI-Fc significantly decreased IgM and IgA responses (Fig. 8 F). Blocking IL-10 also decreased IgG responses. We were also able to detect both CD138 and APRIL expression on the surface of myeloid DCs in the blood of SLE patients (not depicted). However, the numbers of DCs in the small volumes (~10–15 ml) of blood from pediatric patients did not allow us to test their functions. Collectively, our data demonstrate that SLE patient blood monocytes express CD138 and surface APRIL and promote IgM– and IgA–B cell responses. These cells also enhance IgG-secreting responses through the production of IL-10.

DISCUSSION

Autoantibodies are a hallmark of SLE, and B cells remain one of the main therapeutic targets in this disease. Our study demonstrated for the first time that SLE serum induces healthy monocyte differentiation into DCs with a unique ability to promote B cell responses. In particular, SLE-DCs and monocytes from the blood of SLE patients could efficiently generate antibody-secreting PBs, reminiscent of those found in the blood of SLE patients. Thus, SLE serum represents a unique microenvironment for the generation of DCs that could play a role in SLE pathogenesis through interactions with B cells.

IFN-α is a key player contributing to the differentiation of SLE serum–exposed monocytes into DCs (Blanco et al., 2001). However, DCs generated with IFN-α, IFN-DCs, were phenotypically and functionally distinct from SLE-DCs. For example, >50% of the SLE-DCs express CD163 and CCR5, but low numbers of IFN-DCs (<10%) express the two surface molecules. CCR5 is known to be important in disease progression in lupus nephropathy as well as in other glomerular diseases and can be found elevated on the surface of DCs in autoimmune disorders (Furuichi et al., 2000; Stasikowska et al., 2007). It is also expressed on CD14+CD16+ human monocytes, which have been described in the renal interstitium of SLE patients (Furuichi et al., 2000; Stasikowska et al., 2007). Other studies have also shown elevated levels of the CCR5 ligands RANTES and MIP-1α in the kidneys and serum of SLE patients (Lit et al., 2006; Stasikowska et al., 2007; Vilá et al., 2007). CD163 is a scavenger receptor (Van Gorp et al., 2010) that might contribute to the removal of apoptotic cells. Whether CD163 expression plays a role in disease, such as favoring the presentation of apoptotic cell–derived antigens by SLE-DCs, needs to be further studied.

Although IFN-DCs and SLE-DCs were able to induce the proliferation of B cells and their differentiation into PBs, SLE-DCs were more efficient than IFN-DCs at inducing switched B cell responses, especially IgA-secreting B cell responses. The enhanced IgG responses by IFN-DCs and SLE-DCs were mainly dependent on IL-10 and IL-10/BAFF, respectively. The ability of SLE-DCs to induce IgA secretion was further linked to their surface expression of CD138, which enables the trans-presentation of APRIL to B cells. More importantly, SLE blood monocytes also expressed CD138 and trans-presented APRIL to B cells, resulting in the promotion of IgA responses. CD138 expressed on PCs has been described as an APRIL-binding partner, which is the prerequisite for the triggering of TACI- and/or BCMA-mediated PC survival (Ingold et al., 2005). CD138-bound APRIL on the surface of PCs can create unique niches that support the accumulation of PCs in mucosal surfaces (Huard et al., 2008). We found that APRIL trans-presented by SLE-DCs was efficient at enhancing IgA-secreting B cell responses. Soluble APRIL directly added to B cells only resulted in IgM secretion, supporting the idea that trans-presentation of APRIL through CD138 is one of the key mechanisms responsible for SLE-DC–mediated IgA switching and PB differentiation. This is consistent with the requirement of SLE-DCs to be in direct contact with B cells for these effects to be observed.

Although the pathogenic role of SLE IgG autoantibodies is well described, the contribution of IgA to disease pathogenesis remains largely unknown. A previous study has described a profound increase of serum IgA level in lupus patients compared with controls (Conley and Koopman, 1983). Of interest, IgA from some patients has been reported to display a lower degree of glycosylation compared with controls, which has been linked to the pathogenic nature of this isotype in a related disease, IgA nephropathy (Donadio et al., 1978; Matei and Matei, 2000–2001). Furthermore, deposits of IgA are found in the kidneys of patients with SLE (Florquin et al., 2001). Although not currently used as an inclusion criteria for SLE, IgA autoantibodies, such as anticardiolipin and anti–β2-glycoprotein-I, have been shown to predict disease manifestations such as pro-thrombotic events (Wilson et al., 1998; Kumar et al., 2009; Sweiss et al., 2010; Mehrani and Petri, 2011a,b). In addition, the lupus-prone B6.Sle1Sle3 mouse strain produces high levels of anti–nuclear IgA autoantibodies that are deposited in the kidney glomeruli and are implicated in the pathogenesis of nephritis (Liu et al., 2007). Although selective IgA deficiency does not preclude the development of SLE, there is not enough data to ascertain whether IgA-deficient SLE patients could be excluded from suffering certain clinical manifestations such as nephritis and/or display a unique disease course.

The contribution of BAFF to B cell–mediated autoimmune diseases is relatively well understood. Excessive BAFF expression leads to autoimmunity in mice (Mackay et al., 1999; Gross et al., 2000). Elevated levels of BAFF in SLE serum support autoreactive naive B cell (Stohl et al., 2003) and PC survival (Schneider, 2005), which is consistent with our data. Thus, blocking BAFF or BAFF/APRIL is a promising therapeutic approach to treat B cell–mediated autoimmune diseases, and drugs that block BAFF or BAFF/APRIL have been recently approved to treat SLE (Dillon et al., 2006; Sanz and Lee, 2010), although modest clinical responses were observed in phase III clinical trials. However, PBs and PCs predominantly express BCMA and TACI that bind to both BAFF and APRIL. We show that the selective blockade of BAFF reduced only IgG, whereas nonselective blockers (TACI-Fc and BCMA-Fc) also decreased IgA secretion.

The information obtained from this study is particularly relevant to the generation of extrafollicular, T-independent B cell responses (Fagarasan and Honjo, 2000; Litinskiy et al., 2002; Crispín et al., 2010). Studying the role of SLE serum and SLE-DCs in T-dependent B cell responses is warranted, however, as the type of DC–B cell interaction that we herein describe could also be relevant to the expansion and survival of PBs and PCs from a pool of autoreactive memory B cells initially generated in the context of T cell help. It remains to be seen whether therapies, alone or in combination, aimed at blocking these interactions will find a place in the SLE armamentarium.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and sera.

A total of 96 pediatric patients, who met the American College of Rheumatology Revised Criteria for SLE, were enrolled in this study (Table S1). Patients were recruited at the Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children (Dallas, TX) and Children’s Medical Center of Dallas (Dallas, TX). Patients who received i.v. steroid, Mycophenolate, Methotrexate, >10 mg prednisone, and/or >200 mg Plaquenil were excluded. Disease activity was measured by the SLEDAI. 36 healthy controls were recruited at the Baylor Institute for Immunology Research (Dallas, TX). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Baylor Research Institute, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. Blood from patients was obtained during routine examinations. Patient sera were prepared with topical thrombin (King Pharmaceuticals).

Monocytes and B cells.

PBMCs were isolated using Ficoll–Paque PLUS gradient (GE Healthcare). Monocytes were purified using the EasySep Human Monocyte Enrichment kit (negative selection; STEMCELL Technologies) to a purity >93%. Total B cells were purified using the EasySep Human B Cell Enrichment kit (negative selection; STEMCELL Technologies) to a purity >95%. Subsets of B cells were further sorted by FACSAria II or FACSVantage (BD) to yield the following populations: naive (CD19+IgD+CD27−), memory (CD19+IgD−CD27+), marginal zone–like B cells (CD19+IgD+CD27+), and PBs (CD19lowCD20−CD38+) to a purity >97%.

DCs.

IFN-DCs and IL-4–DCs were generated by culturing healthy monocytes in serum-free CellGenix media (CellGenix GmbH) supplemented with 50 ng/ml GM-CSF (Baylor Hospital Pharmacy) and 250 U/ml IFN-α (Schering-Plough) or 50 ng/ml IL-4 (R&D Systems) for 3 or 6 d, respectively. SLE-DCs were generated by culturing healthy monocytes in CellGenix media supplemented with 25% SLE serum for 3 d.

Antibodies, reagents, and flow cytometry.

For the DC phenotype the following were used: anti-CD163-FITC, anti-CD86-PE, anti-CCR5-PE, anti-BCMA, anti–IL-10–PacBlue, anti–IL-6–PE (R&D Systems), anti-CD138-PE, anti-CD1a-FITC, anti-CD80-PE (eBioscience), anti-CD14-PerCp, anti-CD16-APC-Cy7 and anti-CD83-APC (BioLegend), anti-CD138 polyclonal antibody (LSBiosciences), and soluble CD138 (R&D Systems). Purified anti–human APRIL (Enzo Life Sciences) and anti-BCMA antibodies (R&D Systems) were conjugated with Alexa Fluor 647 (Invitrogen) Live/dead-aqua (Invitrogen). For the B cell phenotype the following were used: anti-CD38-PECy7 (BioLegend), anti–human IgG-PE, anti–human IgA-APC (Miltenyi Biotec), anti-CD20-PECy5, anti-CD27-APCCy7 (BD), CFSE, Live/dead-aqua (Invitrogen), and anti-CD138-PE (eBioscience). For B cell sorting, anti–human IgD-PE, anti-CD27-FITC (SouthernBiotech), anti-CD19-APC (BD), and anti-CD3–Quantum red (Sigma-Aldrich), anti-CD38-PECy7 (eBioscience), and BD Cytofix/Cytoperm and BD Perm/Wash (BD) were used for intracellular staining as per the manufacturers’ instructions. Cells were acquired on an LSRII or FACSCanto II (BD), and analysis was performed using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

ELISA.

Sandwich ELISAs were performed to measure total IgM, IgG, IgA, APRIL, and BAFF. Capture and detection antibodies for Ig ELISAs were purchased from SouthernBiotech. Human reference serum (Bethyl Laboratories, Inc.) was used to generate the standard curve for Ig ELISAs. APRIL and BAFF ELISAs were performed using reagents provided by ZymoGenetics. All ELISAs used Nunc MaxiSorp plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Plates were read with a SpectraMax M2 (Molecular Devices) and analyzed with SoftMaxPro V5 software (Molecular Devices).

DC morphology.

Cells were stained using the DiffQuick Stain Set (Siemens) as per the manufacturer’s instructions and visualized on a microscope (BX60; Olympus) at 100× using a digital camera (DXM1200C; Nikon) and NIS Elements Software (Nikon).

Cell culture.

4 × 104 purified B cells were co-cultured with 5 × 103 DCs in RPMI medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with Hepes (Invitrogen), nonessential amino acids, l-glutamate (Sigma-Aldrich), Pen/strep and 10% FBS (HyClone; Thermo Fisher Scientific), and 20 U/ml IL-2 (R&D Systems). 50 nM CpG (ODN2006; InvivoGen) was added to the co-cultures of naive B cells and DCs. CpG was not added into the co-cultures of total or memory B cells and DCs. 10 µg/ml α-BAFF antibody (R&D Systems), TACI-Fc, and BCMA-Fc (ZymoGenetics and R&D systems), and control IgG1 (Sigma-Aldrich) were added into B cell/DC co-culture systems. In some experiments, DCs were preincubated with 2 µg/ml APRIL trimer (ZymoGenetics) for 30 min and then washed before their addition to the B cell co-culture. On day 6, B cells were stained for phenotype and intracellular Igs, and culture supernatants were harvested on day 12 for measuring secreted Igs. To generate PBs, purified total B cells were co-cultured with IL-4–DCs for 6 d. CD19lowCD38+CD20− cells were sorted and used as PBs. 4 × 104 PBs were co-cultured with 5 × 103 DCs. For transwell experiments, 4 × 104 purified B cells were seeded in the lower compartment of a 96-well Nunc transwell insert, and 5 × 103 DCs were added to the upper portion. For some experiments, IL-10 and IL-10R were blocked using reagents from BD (clone JES3-9D7) and BioLegend (clone 3F9), respectively.

Naive B cells (106/ml) were cultured with anti-IgM–coated beads (1 µg/ml; immunobeads rabbit anti–human IgM; Irvine Scientific). Cells were cultured with different concentrations of cytokines, IL-10 (PeproTech), and BAFF (ZymoGenetics) in the presence of 50 nM CpG and 20 U/ml IL-2. B cell proliferation and PB differentiation as well as Ig secretion were measured on day 6 and 12, respectively.

RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from B cells co-cultured with DCs using the RNAqueous Micro kit (Invitrogen), and cDNA was synthesized using the Reverse Transcription System (Promega). cDNA was amplified with the LightCycler SYBR Green Master I kit (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and run on a LightCycler 480 (Roche). Primers for switch circles, mature transcripts, AICDA, and β-actin were as previously described (He et al., 2007; Dullaers et al., 2009); Bcl-XL forward, 5′-AAGCGCTCCTGGCCTTTC-3′; Bcl-XL reverse, 5′-CTGGGACACTTTTGTGGATCTCT-3′; Bcl-2 forward, 5′-TGGGATGCCTTTGTGGAACT-3′; and Bcl-2 reverse, 5′-GAGACAGCCAGGAGAAATCAAAC-3′. Relative expression was determined using the comparative Ct method.

APRIL binding assays.

DCs were incubated with a titrating dose of APRIL trimer (ZymoGenetics) for 30 min at 37°C. 50 µg/ml HSPGs (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the DCs 30 min before the addition of APRIL. Membrane-bound APRIL was detected by anti–human APRIL antibody (Enzo Life Sciences).

Cytokine ELISA and intracellular staining.

105 DCs were plated in a 100-µl volume and stimulated for 24 h with and without 20 ng/ml Escherichia coli LPS (InvivoGen). IL-10 was measured on a Luminex bead-based platform using a Bio Plex 200 and the Bio Plex Manager 5.0 software (Bio-Rad Laboratories). This system was also used to determine the concentration of IL-10 in DC–B cell co-culture systems. Both IFN-DCs and SLE-DCs were stained for intracellular IL-6 and IL-10 before co-culturing with B cells. In addition, DCs and naive B cells were co-cultured for 24 h and then stained for intracellular IL-6 and IL-10.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical significance was determined using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Student’s t test using Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software). Significance was set at P < 0.05.

Online supplemental material.

Fig. S1 shows that TACI-Fc and anti-BAFF antibody decrease IgM and IgA as well as IgG responses, respectively, in dose-dependent manners. Table S1 presents demographics of SLE patients and healthy donors tested in this study. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20111644/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jeanine Baisch for coordinating samples and obtaining clinical data. We thank Tracey Wright, Alisa Gotte, Lorien Nassi, and Matthew Stoll for collecting patient samples at the Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children. We thank Nicolas Loof and colleagues in the Flow Cytometry Core, Lynnette Walters in the Cell Processing Core, and Shannon Lunt in the Sample Core at the Baylor Institute for Immunology Research (BIIR). We thank Dr. Carson Harrod at BIIR for reading and editing this manuscript. We also thank Dr. Michael A. Ramsay for supporting this study.

This work was supported by P50-ARO 5503 (National Institutes of Health [NIH]), P50-ARO 54083 (NIH), and the Baylor Health Care System Foundation.

The authors have no competing financial interests regarding this work.

Author contributions: H. Joo, C. Coquery, Y. Xue, and S. Oh performed experiments and analyzed data. I. Gayet provided technical assistance. S.R. Dillon and M. Punaro provided reagents and patient samples, respectively. G. Zurawski, J. Banchereau, and V. Pascual analyzed data and helped with writing this manuscript. H. Joo and S. Oh wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- APRIL

- a proliferation-inducing ligand

- BAFF

- B cell–activating factor

- HSPG

- heparan sulfate proteoglycan

- PB

- plasmablast

- PC

- plasma cell

- SLE

- systemic lupus erythematosus

- SLEDAI

- SLE disease activity index

References

- Arbuckle M.R., McClain M.T., Rubertone M.V., Scofield R.H., Dennis G.J., James J.A., Harley J.B. 2003. Development of autoantibodies before the clinical onset of systemic lupus erythematosus. N. Engl. J. Med. 349:1526–1533 10.1056/NEJMoa021933 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Arce E., Jackson D.G., Gill M.A., Bennett L.B., Banchereau J., Pascual V. 2001. Increased frequency of pre-germinal center B cells and plasma cell precursors in the blood of children with systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Immunol. 167:2361–2369 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Arpin C., Déchanet J., Van Kooten C., Merville P., Grouard G., Brière F., Banchereau J., Liu Y.J. 1995. Generation of memory B cells and plasma cells in vitro. Science. 268:720–722 10.1126/science.7537388 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Banchereau J., Pascual V., Palucka A.K. 2004. Autoimmunity through cytokine-induced dendritic cell activation. Immunity. 20:539–550 10.1016/S1074-7613(04)00108-6 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bernasconi N.L., Traggiai E., Lanzavecchia A. 2002. Maintenance of serological memory by polyclonal activation of human memory B cells. Science. 298:2199–2202 10.1126/science.1076071 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco P., Palucka A.K., Gill M., Pascual V., Banchereau J. 2001. Induction of dendritic cell differentiation by IFN-alpha in systemic lupus erythematosus. Science. 294:1540–1543 10.1126/science.1064890 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Burdin N., Van Kooten C., Galibert L., Abrams J.S., Wijdenes J., Banchereau J., Rousset F. 1995. Endogenous IL-6 and IL-10 contribute to the differentiation of CD40-activated human B lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 154:2533–2544 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Cappione A., III, Anolik J.H., Pugh-Bernard A., Barnard J., Dutcher P., Silverman G., Sanz I. 2005. Germinal center exclusion of autoreactive B cells is defective in human systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Clin. Invest. 115:3205–3216 10.1172/JCI24179 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cheema G.S., Roschke V., Hilbert D.M., Stohl W. 2001. Elevated serum B lymphocyte stimulator levels in patients with systemic immune-based rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 44:1313–1319 10.1002/1529-0131(200106)44:6<1313::AID-ART223>3.0.CO;2-S [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Conley M.E., Koopman W.J. 1983. Serum IgA1 and IgA2 in normal adults and patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and hepatic disease. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 26:390–397 10.1016/0090-1229(83)90123-X [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Crispín J.C., Kyttaris V.C., Terhorst C., Tsokos G.C. 2010. T cells as therapeutic targets in SLE. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 6:317–325 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.60 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon S.R., Gross J.A., Ansell S.M., Novak A.J. 2006. An APRIL to remember: novel TNF ligands as therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 5:235–246 10.1038/nrd1982 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Donadio J.V., Jr, Conn D.L., Holley K.E., Ilstrup D.M. 1978. Class of immunoglobulin deposition and prognosis in lupus nephritis. Mayo Clin. Proc. 53:366–372 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B., Vanbervliet B., Fayette J., Massacrier C., Van Kooten C., Brière F., Banchereau J., Caux C. 1997. Dendritic cells enhance growth and differentiation of CD40-activated B lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 185:941–951 10.1084/jem.185.5.941 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dullaers M., Li D., Xue Y., Ni L., Gayet I., Morita R., Ueno H., Palucka K.A., Banchereau J., Oh S. 2009. A T cell-dependent mechanism for the induction of human mucosal homing immunoglobulin A-secreting plasmablasts. Immunity. 30:120–129 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.008 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fagarasan S., Honjo T. 2000. T-Independent immune response: new aspects of B cell biology. Science. 290:89–92 10.1126/science.290.5489.89 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Florquin S., Roos A., Groothoff J.W., Claessen N., van Gijlswijk-Janssen D.J., Aten J., Davin J.C., Weening J.J. 2001. Severe non-proliferative lupus nephritis with predominant sub-endothelial IgA deposits. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 16:1479–1482 10.1093/ndt/16.7.1479 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Furuichi K., Wada T., Sakai N., Iwata Y., Yoshimoto K., Shimizu M., Kobayashi K., Takasawa K., Kida H., Takeda S.I., et al. 2000. Distinct expression of CCR1 and CCR5 in glomerular and interstitial lesions of human glomerular diseases. Am. J. Nephrol. 20:291–299 10.1159/000013603 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gill M.A., Blanco P., Arce E., Pascual V., Banchereau J., Palucka A.K. 2002. Blood dendritic cells and DC-poietins in systemic lupus erythematosus. Hum. Immunol. 63:1172–1180 10.1016/S0198-8859(02)00756-5 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi C.M., Michael D.J., Diamond B. 2001. Cutting edge: expansion and activation of a population of autoreactive marginal zone B cells in a model of estrogen-induced lupus. J. Immunol. 167:1886–1890 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi C.M., Cleary J., Dagtas A.S., Moussai D., Diamond B. 2002. Estrogen alters thresholds for B cell apoptosis and activation. J. Clin. Invest. 109:1625–1633 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J.A., Johnston J., Mudri S., Enselman R., Dillon S.R., Madden K., Xu W., Parrish-Novak J., Foster D., Lofton-Day C., et al. 2000. TACI and BCMA are receptors for a TNF homologue implicated in B-cell autoimmune disease. Nature. 404:995–999 10.1038/35010115 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- He B., Qiao X., Cerutti A. 2004. CpG DNA induces IgG class switch DNA recombination by activating human B cells through an innate pathway that requires TLR9 and cooperates with IL-10. J. Immunol. 173:4479–4491 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- He B., Xu W., Santini P.A., Polydorides A.D., Chiu A., Estrella J., Shan M., Chadburn A., Villanacci V., Plebani A., et al. 2007. Intestinal bacteria trigger T cell-independent immunoglobulin A(2) class switching by inducing epithelial-cell secretion of the cytokine APRIL. Immunity. 26:812–826 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.014 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks J., Planelles L., de Jong-Odding J., Hardenberg G., Pals S.T., Hahne M., Spaargaren M., Medema J.P. 2005. Heparan sulfate proteoglycan binding promotes APRIL-induced tumor cell proliferation. Cell Death Differ. 12:637–648 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401647 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Huard B., McKee T., Bosshard C., Durual S., Matthes T., Myit S., Donze O., Frossard C., Chizzolini C., Favre C., et al. 2008. APRIL secreted by neutrophils binds to heparan sulfate proteoglycans to create plasma cell niches in human mucosa. J. Clin. Invest. 118:2887–2895 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Huggins J., Pellegrin T., Felgar R.E., Wei C., Brown M., Zheng B., Milner E.C., Bernstein S.H., Sanz I., Zand M.S. 2007. CpG DNA activation and plasma-cell differentiation of CD27− naive human B cells. Blood. 109:1611–1619 10.1182/blood-2006-03-008441 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ingold K., Zumsteg A., Tardivel A., Huard B., Steiner Q.G., Cachero T.G., Qiang F., Gorelik L., Kalled S.L., Acha-Orbea H., et al. 2005. Identification of proteoglycans as the APRIL-specific binding partners. J. Exp. Med. 201:1375–1383 10.1084/jem.20042309 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Jego G., Palucka A.K., Blanck J.P., Chalouni C., Pascual V., Banchereau J. 2003. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells induce plasma cell differentiation through type I interferon and interleukin 6. Immunity. 19:225–234 10.1016/S1074-7613(03)00208-5 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W., Lederman M.M., Harding C.V., Rodriguez B., Mohner R.J., Sieg S.F. 2007. TLR9 stimulation drives naïve B cells to proliferate and to attain enhanced antigen presenting function. Eur. J. Immunol. 37:2205–2213 10.1002/eji.200636984 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kang K.Y., Kim H.O., Kwok S.K., Ju J.H., Park K.S., Sun D.I., Jhun J.Y., Oh H.J., Park S.H., Kim H.Y. 2011. Impact of interleukin-21 in the pathogenesis of primary Sjogren’s syndrome: increased serum levels of interleukin-21 and its expression in the labial salivary glands. Arthritis Res. Ther. 13:R179 10.1186/ar3504 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Koffler D., Agnello V., Thoburn R., Kunkel H.G. 1971. Systemic lupus erythematosus: Prototype of immune complex nephritis in man. J. Exp. Med. 134:169–179 10.1084/jem.134.3.169 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kotzin B.L. 1996. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Cell. 85:303–306 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81108-3 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama T., Tsukamoto H., Miyagi Y., Himeji D., Otsuka J., Miyagawa H., Harada M., Horiuchi T. 2005. Raised serum APRIL levels in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 64:1065–1067 10.1136/ard.2004.022491 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Krieg A.M., Yi A.K., Matson S., Waldschmidt T.J., Bishop G.A., Teasdale R., Koretzky G.A., Klinman D.M. 1995. CpG motifs in bacterial DNA trigger direct B-cell activation. Nature. 374:546–549 10.1038/374546a0 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Papalardo E., Sunkureddi P., Najam S., González E.B., Pierangeli S.S. 2009. Isolated elevation of IgA anti-beta2glycoprotein I antibodies with manifestations of antiphospholipid syndrome: a case series of five patients. Lupus. 18:1011–1014 10.1177/0961203309103048 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo P., Bynoe M.S., Wang C., Diamond B. 1999. Bcl-2 leads to expression of anti-DNA B cells but no nephritis: a model for a clinical subset. Eur. J. Immunol. 29:3168–3178 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199910)29:10<3168::AID-IMMU3168>3.0.CO;2-H [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lin G.G., Li J.M. 2009. IgG subclass serum levels in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Clin. Rheumatol. 28:1315–1318 10.1007/s10067-009-1224-x [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lit L.C., Wong C.K., Tam L.S., Li E.K., Lam C.W. 2006. Raised plasma concentration and ex vivo production of inflammatory chemokines in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 65:209–215 10.1136/ard.2005.038315 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Litinskiy M.B., Nardelli B., Hilbert D.M., He B., Schaffer A., Casali P., Cerutti A. 2002. DCs induce CD40-independent immunoglobulin class switching through BLyS and APRIL. Nat. Immunol. 3:822–829 10.1038/ni829 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K., Li Q.Z., Yu Y., Liang C., Subramanian S., Zeng Z., Wang H.W., Xie C., Zhou X.J., Mohan C., Wakeland E.K. 2007. Sle3 and Sle5 can independently couple with Sle1 to mediate severe lupus nephritis. Genes Immun. 8:634–645 10.1038/sj.gene.6364426 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay F., Woodcock S.A., Lawton P., Ambrose C., Baetscher M., Schneider P., Tschopp J., Browning J.L. 1999. Mice transgenic for BAFF develop lymphocytic disorders along with autoimmune manifestations. J. Exp. Med. 190:1697–1710 10.1084/jem.190.11.1697 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Matei L., Matei I. 2000–2001. Lectin-binding profile of serum IgA in women suffering from systemic autoimmune rheumatic disorders. Rom. J. Intern. Med. 38-39:73–82 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrani T., Petri M. 2011a. Association of IgA Anti-beta2 glycoprotein I with clinical and laboratory manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Rheumatol. 38:64–68 10.3899/jrheum.100568 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrani T., Petri M. 2011b. IgM anti-β2 glycoprotein I is protective against lupus nephritis and renal damage in systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Rheumatol. 38:450–453 10.3899/jrheum.100650 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mietzner B., Tsuiji M., Scheid J., Velinzon K., Tiller T., Abraham K., Gonzalez J.B., Pascual V., Stichweh D., Wardemann H., Nussenzweig M.C. 2008. Autoreactive IgG memory antibodies in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus arise from nonreactive and polyreactive precursors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105:9727–9732 10.1073/pnas.0803644105 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Moreaux J., Sprynski A.C., Dillon S.R., Mahtouk K., Jourdan M., Ythier A., Moine P., Robert N., Jourdan E., Rossi J.F., Klein B. 2009. APRIL and TACI interact with syndecan-1 on the surface of multiple myeloma cells to form an essential survival loop. Eur. J. Haematol. 83:119–129 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01262.x [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Odendahl M., Jacobi A., Hansen A., Feist E., Hiepe F., Burmester G.R., Lipsky P.E., Radbruch A., Dörner T. 2000. Disturbed peripheral B lymphocyte homeostasis in systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Immunol. 165:5970–5979 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnmacht C., Pullner A., King S.B., Drexler I., Meier S., Brocker T., Voehringer D. 2009. Constitutive ablation of dendritic cells breaks self-tolerance of CD4 T cells and results in spontaneous fatal autoimmunity. J. Exp. Med. 206:549–559 10.1084/jem.20082394 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual V., Banchereau J., Palucka A.K. 2003. The central role of dendritic cells and interferon-alpha in SLE. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 15:548–556 10.1097/00002281-200309000-00005 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh-Bernard A.E., Silverman G.J., Cappione A.J., Villano M.E., Ryan D.H., Insel R.A., Sanz I. 2001. Regulation of inherently autoreactive VH4-34 B cells in the maintenance of human B cell tolerance. J. Clin. Invest. 108:1061–1070 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Santulli-Marotto S., Qian Y., Ferguson S., Clarke S.H. 2001. Anti-Sm B cell differentiation in Ig transgenic MRL/Mp-lpr/lpr mice: altered differentiation and an accelerated response. J. Immunol. 166:5292–5299 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz I., Lee F.E. 2010. B cells as therapeutic targets in SLE. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 6:326–337 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.68 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider P. 2005. The role of APRIL and BAFF in lymphocyte activation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 17:282–289 10.1016/j.coi.2005.04.005 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stasikowska O., Danilewicz M., Wagrowska-Danilewicz M. 2007. The significant role of RANTES and CCR5 in progressive tubulointerstitial lesions in lupus nephropathy. Pol. J. Pathol. 58:35–40 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Stohl W., Metyas S., Tan S.M., Cheema G.S., Oamar B., Xu D., Roschke V., Wu Y., Baker K.P., Hilbert D.M. 2003. B lymphocyte stimulator overexpression in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: longitudinal observations. Arthritis Rheum. 48:3475–3486 10.1002/art.11354 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sweiss N.J., Bo R., Kapadia R., Manst D., Mahmood F., Adhikari T., Volkov S., Badaracco M., Smaron M., Chang A., et al. 2010. IgA anti-beta2-glycoprotein I autoantibodies are associated with an increased risk of thromboembolic events in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. PLoS ONE. 5:e12280 10.1371/journal.pone.0012280 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Teichmann L.L., Ols M.L., Kashgarian M., Reizis B., Kaplan D.H., Shlomchik M.J. 2010. Dendritic cells in lupus are not required for activation of T and B cells but promote their expansion, resulting in tissue damage. Immunity. 33:967–978 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.11.025 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gorp H., Delputte P.L., Nauwynck H.J. 2010. Scavenger receptor CD163, a Jack-of-all-trades and potential target for cell-directed therapy. Mol. Immunol. 47:1650–1660 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.02.008 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Vilá L.M., Molina M.J., Mayor A.M., Cruz J.J., Ríos-Olivares E., Ríos Z. 2007. Association of serum MIP-1alpha, MIP-1beta, and RANTES with clinical manifestations, disease activity, and damage accrual in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin. Rheumatol. 26:718–722 10.1007/s10067-006-0387-y [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wardemann H., Yurasov S., Schaefer A., Young J.W., Meffre E., Nussenzweig M.C. 2003. Predominant autoantibody production by early human B cell precursors. Science. 301:1374–1377 10.1126/science.1086907 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wei C., Anolik J., Cappione A., Zheng B., Pugh-Bernard A., Brooks J., Lee E.H., Milner E.C., Sanz I. 2007. A new population of cells lacking expression of CD27 represents a notable component of the B cell memory compartment in systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Immunol. 178:6624–6633 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson W.A., Faghiri Z., Taheri F., Gharavi A.E. 1998. Significance of IgA antiphospholipid antibodies. Lupus. 7:S110–S113 10.1177/096120339800700225 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W., He B., Chiu A., Chadburn A., Shan M., Buldys M., Ding A., Knowles D.M., Santini P.A., Cerutti A. 2007. Epithelial cells trigger frontline immunoglobulin class switching through a pathway regulated by the inhibitor SLPI. Nat. Immunol. 8:294–303 10.1038/ni1434 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizaki K., Nakagawa T., Kaieda T., Muraguchi A., Yamamura Y., Kishimoto T. 1982. Induction of proliferation and Ig production in human B leukemic cells by anti-immunoglobulins and T cell factors. J. Immunol. 128:1296–1301 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Yurasov S., Wardemann H., Hammersen J., Tsuiji M., Meffre E., Pascual V., Nussenzweig M.C. 2005. Defective B cell tolerance checkpoints in systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Exp. Med. 201:703–711 10.1084/jem.20042251 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Yurasov S., Tiller T., Tsuiji M., Velinzon K., Pascual V., Wardemann H., Nussenzweig M.C. 2006. Persistent expression of autoantibodies in SLE patients in remission. J. Exp. Med. 203:2255–2261 10.1084/jem.20061446 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Articles from The Journal of Experimental Medicine are provided here courtesy of The Rockefeller University Press

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20111644

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

http://jem.rupress.org/content/jem/209/7/1335.full.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1084/jem.20111644

Article citations

Distinct transcriptomes and autocrine cytokines underpin maturation and survival of antibody-secreting cells in systemic lupus erythematosus.

Nat Commun, 15(1):1899, 01 Mar 2024

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 38429276 | PMCID: PMC10907730

The contribution of a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL) and other TNF superfamily members in pathogenesis and progression of IgA nephropathy.

Clin Kidney J, 16(suppl 2):ii9-ii18, 04 Dec 2023

Cited by: 8 articles | PMID: 38053976 | PMCID: PMC10695512

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

α-Ketoglutarate-Dependent KDM6 Histone Demethylases and Interferon-Stimulated Gene Expression in Lupus.

Arthritis Rheumatol, 76(3):396-410, 11 Jan 2024

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 37800478

Autoimmune Responses and Therapeutic Interventions for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Comprehensive Review.

Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets, 24(5):499-518, 01 Jan 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37718519

Review

The SYSCID map: a graphical and computational resource of molecular mechanisms across rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus and inflammatory bowel disease.

Front Immunol, 14:1257321, 01 Nov 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38022524 | PMCID: PMC10646502

Go to all (71) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

BAFF-R and TACI expression on CD3+ T cells: Interplay among BAFF, APRIL and T helper cytokines profile in systemic lupus erythematosus.

Cytokine, 114:115-127, 19 Nov 2018

Cited by: 17 articles | PMID: 30467093

Plasmablasts With a Mucosal Phenotype Contribute to Plasmacytosis in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus.

Arthritis Rheumatol, 69(10):2018-2028, 01 Oct 2017

Cited by: 22 articles | PMID: 28622453

Deficient TACI expression on B lymphocytes of newborn mice leads to defective Ig secretion in response to BAFF or APRIL.

J Immunol, 181(2):976-990, 01 Jul 2008

Cited by: 55 articles | PMID: 18606649

BAFF and selection of autoreactive B cells.

Trends Immunol, 32(8):388-394, 13 Jul 2011

Cited by: 102 articles | PMID: 21752714 | PMCID: PMC3151317

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NIAMS NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: P50 AR054083

PHS HHS (1)

Grant ID: P50-ARO 5503

1

1