Abstract

Free full text

CCDC39 is required for assembly of inner dynein arms and the dynein regulatory complex and for normal ciliary motility in humans and dogs

Abstract

Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) is an inherited disorder characterized by recurrent infections of the upper and lower respiratory tract, reduced fertility in males and situs inversus in about 50% of affected individuals (Kartagener syndrome). It is caused by motility defects in the respiratory cilia that are responsible for airway clearance, the flagella that propel sperm cells and the nodal monocilia that determine left-right asymmetry1. Recessive mutations that cause PCD have been identified in genes encoding components of the outer dynein arms, radial spokes and cytoplasmic pre-assembly factors of axonemal dyneins, but these mutations account for only about 50% of cases of PCD. We exploited the unique properties of dog populations to positionally clone a new PCD gene, CCDC39. We found that loss-of-function mutations in the human ortholog underlie a substantial fraction of PCD cases with axonemal disorganization and abnormal ciliary beating. Functional analyses indicated that CCDC39 localizes to ciliary axonemes and is essential for assembly of inner dynein arms and the dynein regulatory complex.

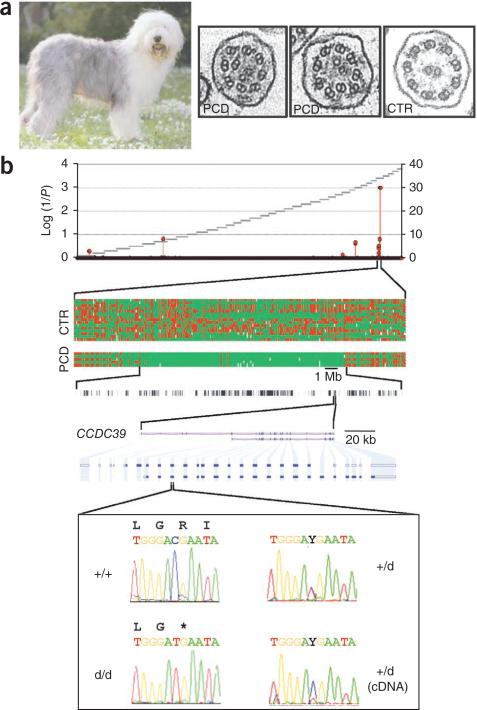

Between December 2006 and November 2007, we examined five Old English Sheepdogs (Bobtails aged 8–15 months and 3 littermates) suffering from chronic airway inflammation. Radiography revealed situs inversus in one, which suggested PCD2. This was confirmed by identifying ciliary defects in nasal and tracheal biopsies and in respiratory epithelial cell cultures using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). We noted absent or eccentric central pairs, occasional displacement of outer doublets, reductions in the mean number of inner dynein arms, and abnormal radial spokes and nexin links (Fig. 1a), reminiscent of an earlier report of PCD in Bobtails3. Pedigree analysis indicated that the parents of the five probands traced back to the same female champion. Interviews with breeders and veterinarians led to the identification of ten additional Bobtail litters with PCD. All parents were descended from the same founder female. For litters with complete records, parents were reported healthy, the proportion of affected offspring was 21 out of 65 (32%) and the male:female ratio among cases was 9:14, which suggests autosomal recessive inheritance (Supplementary Fig. 1). Situs inversus was confirmed in three out of nine cases examined. A spermogram conducted on one affected male revealed oligoasthenospermia. The midpiece was narrowed in around one-third of sperm cells and the flagellum was shortened in around one-fifth.

Positional identification of CCDC39 as the gene that underlies PCD in Bobtails. (a) Old English Sheepdog (Bobtail). Representative TEM images of disorganized cilia identified in nasal mucosal biopsies of cases (PCD) and normal cilia from a healthy dog (CTR). (b) Positional identification of the p.Arg96X alteration in CCDC39. Homozygosity mapping identified a genome-wide significant signal on chromosome CFA34, corresponding to a 15-Mb segment shared homozygous- by-descent by 5 affected animals and encompassing 151 annotated protein-coding genes, of which 10 were included in the ciliome or cilia proteome database (or both). Sequencing CCDC39 in affected individuals revealed a C>T transition in the third exon of the main isoform, creating a stop codon that causes nonsense-mediated RNA decay. d, disease.

We genotyped 5 cases and 15 controls with the Affymetrix v2 Canine array. We found a 15-Mb segment of autozygosity on chromosome 34 that was shared by all cases (genome-wide P < 0.001; Fig. 1b). The shared region contained 151 genes. We mined the ciliary proteome4 and ciliome5 databases and identified ten proteins that had been discovered in at least two independent genomic or proteomic studies of cilia enrichment. We sequenced the coding exons and intron-exon boundaries of six of these candidates in cases and controls and identified a stop codon (p.Arg96X) in CCDC39 (Gene ID: 488089) in the affected dogs that was predicted to truncate 90% of the 976–amino acid CCDC39 protein (Fig. 1b). All of 10 additional cases were homozygous for the p.Arg96X alteration, all of 10 obligate carriers were heterozygous for it and 8 of 102 randomly sampled healthy Bobtails were heterozygous for it; we did not find the alteration in 80 healthy animals from 9 other breeds. We sequenced CCDC39 RT-PCR products from the tracheal RNA of a carrier and found a mutant to wildtype allelic ratio of about 0.25, compatible with nonsense-mediated RNA decay of transcripts containing the p.Arg96X alteration (Fig. 1b).

FAP59, the Chlamydomonas ortholog of CCDC39, was predicted to be essential for motile ciliary function, as orthologs do not occur in nonciliated organisms (‘CiliaCut’) or in Caenorhabditis elegans (‘MotileCut’)6. FAP59 was also among the top 50 of the 650 proteins that were detected by mass spectrometry in purified flagella of Chlamydomonas, consistent with ciliary localization7. Mouse Ccdc39 was predicted to be present in cilia because Ccdc39 is strongly expressed in tissues rich in ciliated cells; Ccdc39 was also shown by in situ hybridization to be expressed in olfactory and vomeronasal sensory neurons and the respiratory epithelium8. To extend these findings, we performed in situ hybridization at different stages of mouse development and identified specific expression of Ccdc39 in node cells carrying motile cilia, in upper and lower airways, and in ependymal and choroid plexus cells, consistent with Ccdc39 having a functional role in motile cilia (Fig. 2a). In tissue from adult humans, quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) showed predominant expression of CCDC39 in nasal brushings and, to a lesser extent, in lungs and testes. However, this expression was systematically lower than that of other PCD genes (expression of DNAI1 > DNAI2 > LRRC50 ≈ C14orf104 (also called KTU) > CCDC39; Supplementary Fig. 2a,b).

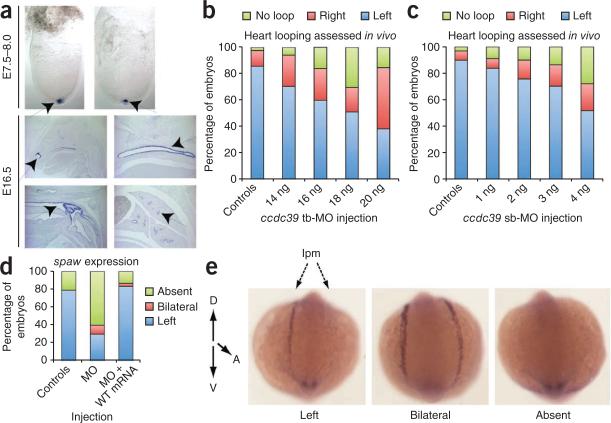

Expression and functional studies in mouse and zebrafish. (a) Whole-mount in situ hybridization analysis of mouse Ccdc39 in mouse embryos. Ccdc39 expression is restricted to the node in embryos at embryonic day (E) 7.75–8.0 (arrowheads). In E16.5 mouse embryonic sections, Ccdc39 (arrowheads) is expressed in ciliated cells of the upper and lower airways. (b) Dose-response curve of ccdc39 translation-blocking morpholino (tb-MO). Wildtype zebrafish embryos were injected with increasing concentrations of tb-MO and were scored live at 36 h post fertilization for heart looping (left, right, no loop). (c) Dose-response curve of ccdc39 splice-blocking MO. Scoring was conducted as in b. (d) Quantification of spaw staining in embryo batches injected with 4 ng ccdc39 morpholino or 4 ng ccdc39 morpholino plus 25 pg wildtype (WT) human CCDC39 mRNA (n = 24–30 embryos per injection). (e) Representative spaw RNA in situ staining in 14 somite-stage embryos. In wildtype embryos, spaw is expressed in the left lateral plate mesoderm (lpm; left); however, ccdc39 morphant embryos showed bilateral (center) or, in most cases, undetectable spaw expression (right).

To provide further support for the role of CCDC39 in ciliary motility, we used morpholino-based suppression of ccdc39 in zebrafish embryos. Using reciprocal BLAST, we identified the only Danio rerio ortholog of CCDC39 (LOC555319; 53% identity and 73% similarity). We amplified this transcript readily from embryonic complementary DNA (cDNA) as early as the shield stage (data not shown). Injection of either a translation-blocking or a splice-blocking morpholino at the two-cell stage caused a dose-dependent increase in heart-looping defects at 36 hours post-fertilization (rightward or absent looping; Fig. 2b,c and Supplementary Fig. 3) and bilateral or lack of spaw expression at the left lateral plate mesoderm in 14 somite embryos (Fig. 2d,e). These phenotypes were likely specific, as they were reproduced at similar frequencies by both morpholinos and were rescued by co-injection with wildtype human CCDC39 mRNA (Fig. 2d). These findings recapitulate laterality defects seen in other PCD morphants (for example, C14orf104, also known as ktu, and lrrc50)9,10, consistent with compromised fluid flow at the Kupffer's vesicle due to impaired ciliary motility.

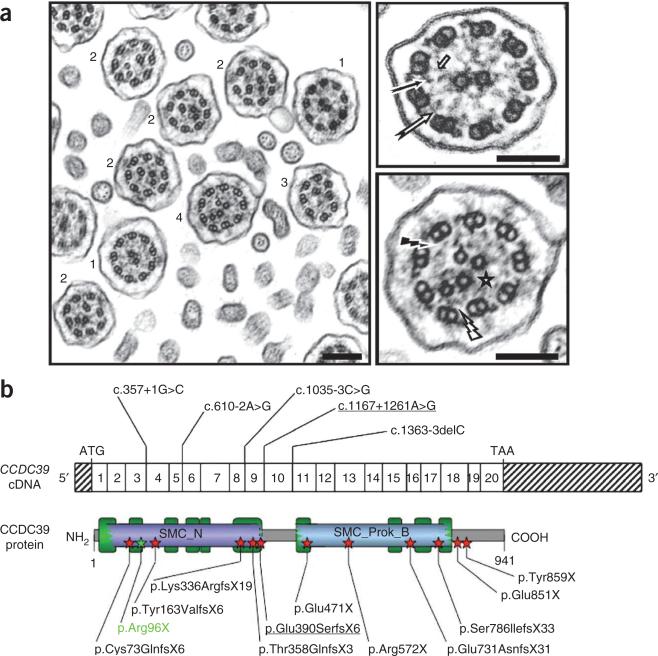

These findings prompted us to screen for mutations in unresolved human PCD cases (Supplementary Note). We sequenced the 20 coding exons and intron-exon boundaries of human CCDC39 (Gene ID: 339829) in 53 cases (from 50 families) with axonemal defects reminiscent of those observed in Bobtails, that is, the absence of inner dynein arms in all examined cilia and coexistence of axonemes with various ultrastructural defects within the same section (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 4). This group accounts for 5–15% of PCD cases11. We detected 14 unambiguous loss-of-function mutations in 19 of the 50 families (38%): four nonsense mutations, six frameshifts leading to premature stop codons and four splice-site variants (located within 3 bp of an intron-exon boundary) (Fig. 3b and Table 1). Notably, no nonsense or frameshift mutations in CCDC39 were reported in the latest 1000 Genomes Project data release (see URLs) for 60 sequenced individuals. Transmission of mutations was consistent with autosomal recessive inheritance (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 5). Fifteen cases (ten of whom were consanguineous) were homozygous and five were compound heterozygous. Two cases carried only one pathogenic allele (DCP580 and DCP481). Nasal epithelial cells were available for DCP580, allowing us to investigate the integrity of the CCDC39 mRNA by RT-PCR. One primer pair yielded a unique 537-bp amplicon in control subjects as well as an additional 644-bp product in DCP580 because of a 116-bp insertion between exons 9 and 10. Sequencing of the corresponding genomic region showed that this insertion resulted from activation of a pseudo-exon in intron 9 (designated ψExon9). The sequence 5′ of ψExon9 matches a perfect acceptor splice site, and its 3′ boundary contains a near-perfect splice donor site that is activated by an AT>GT transition involving nucleotide c.1167+1261 (Supplementary Fig. 6). This mutation (which, if translated, would lead to the frameshift alteration p.Glu390SerfsX6) was not found in any other case. A second loss-of-function mutation has not yet been identified for DCP481, but two previously unknown candidate variants are worth mentioning: a missense variation involving a highly conserved residue (p.Thr594Ile) and a putative branch site variant in intron 9 (c.1168-32A>G). We also detected two rare missense variations in the heterozygous state among the 31 remaining cases (p.Cys803Tyr and p.Thr182Ser), but their effect on CCDC39 function is unknown.

Ultrastructural and mutational analysis of human PCD cases with axonemal disorganization. (a) Electron microscopy of respiratory cilia from an individual (DCP85) who is homozygous for the CCDC39 mutation resulting in the p.Glu731AsnfsX31 alteration. It shows the absence of inner dynein arms in all ciliary sections, associated with a range of other, heterogeneous defects: isolated absence of the nine inner dynein arms (1), axonemal disorganization with mislocalized peripheral doublet associated with either a displacement of the central pair (2), an absence of the central pair (3), or supernumerary central pairs (4). Magnification of the axoneme from a normal cilium is shown in the upper right panel with presence of inner dynein arms (black arrow), nexin links (white arrow) and radial spokes (short arrow). The axonemal disorganization found in cases is associated with defects of inner dynein arms (black flash), nexin links (white flash) and radial spokes (star) that are better seen after magnification (lower right panel). Scale bar, 0.2 μm. (b) Unambiguous disease-causing CCDC39 mutations detected in PCD cases with axonemal disorganization. Exonic organization of the human CCDC39 cDNA (top) and domain organization model of the corresponding protein (bottom). The 20 coding exons are indicated by empty or hashed boxes, depicting translated or untranslated sequences, respectively. ‘SMC_N’ and ‘SMC_Prok_B’ refer to domains homologous to the N terminus of SMC (structural maintenance of chromosomes) proteins and to the common bacterial type SMC protein, respectively. The predicted coiled-coil domains of the protein are indicated by green rectangles. The canine p.Arg96X alteration is shown in green. The splice mutation leading to the inclusion of pseudo-exon 9 is underlined.

Table 1

CCDC39 mutations in PCD cases with axonemal disorganization

| Subject | Origin | Sex | Consanguineous | Laterality defects | Sperm defects | Alteration and mutation 1 | Alteration and mutation 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCP85a | Algeria | F | Y | – | – |

p.Glu731AsnfsX31

c.2190delA |

p.Glu731AsnfsX31

c.2190delA |

| DCP91a | Unknown | F | Y | – | – |

p.Glu731AsnfsX31c

c.2190delA |

p.Glu731AsnfsX31

c.2190delA |

| DCP413a | Northern Africa | M | Y | Kartagener | NA | p.Glu731AsnfsX31 | p.Glu731AsnfsX31 |

| DCP414a | M | Y | Kartagener | NA | c.2190delA | c.2190delA | |

| DCP532 | Tunisia | M | N | Kartagener | NA |

p.Glu731AsnfsX31

c.2190delA |

p.Glu731AsnfsX31

c.2190delA |

| DCP554 | Algeria | M | N | – | OAS |

p.thr358GlnfsX3

c.1072delA |

p.thr358GlnfsX3

c.1072delA |

| DCP384 | Unknown | F | Y | – | – |

p.thr358GlnfsX3

c.1072delA |

p.thr358GlnfsX3

c.1072delA |

| OP122b | Germany | M | N | Ivemark | OAS |

p.thr358GlnfsX3

c.1072delA | p.Lys336ArgfsX19 c.1007-1010delAGAA |

| DCP552a | Turkey | M | N | Kartagener | NA | c.357+1G>C | c.357+1G>C |

| DCP553a | M | N | Ivemark | NA | |||

| DCP274b | France | M | N | Kartagener | NA | c.357+1G>C | c.610-2A>G |

| OP736 II1b | Denmark | F | N | – | – | c.357+1G>C | p.Glu851X |

| OP736 II2b | M | N | – | – | c.2551G>T | ||

| DCP158a | France | M | N | – | NA | c.357+1G>C |

p.ser786IlefsX33

c.2357_2359delinsT |

| DCP580b | West Indies/Senegal | M | N | Kartagener | OAS |

p.ser786IlefsX33

c.2357_2359delinsT | p.Glu390SerfsX6 c.1167+1261A>G |

| DCP533 | Tunisia | F | Y | Heterotaxia | – | p.Tyr859X c.2577C>A | p.Tyr859X c.2577C>A |

| DCP528a | Egypt | F | Y | Kartagener | – | p.Cys73GlnfsX6 c.216_217delTT | p.Cys73GlnfsX6 c.216_217delTT |

| DCP323 | Unknown | F | N | Kartagener | – | c.1035-3C>G | c.1035-3C>G |

| DCP181a | Algeria | F | Y | – | – | p.Arg572X c.1714C>T | p.Arg572X c.1714C>T |

| OP18 II1a | Turkey | F | Y | Kartagener | – | p.Tyr163ValfsX6 c.485-486insA | p.Tyr163ValfsX6 c.485-486insA |

| OI5 II1a | Israel | F | Y | Kartagener | – | p.Glu471X c.1410G>T | p.Glu471X c.1410G>T |

| DCP481 | Algeria | M | N | – | OAS | c.1363-3delC | Unknown |

For subjects, DCPXXX, French cohort; OXXX, German cohort. Pairs of individuals in the same row are siblings. For sperm defects, OAS, oligoasthenospermia; NA, not analyzed. Founder mutations are shown in bold.

Of the 15 unambiguous disease-causing mutations, 11 were private, whereas 4 were shared by several families not known to be related (Table 1). Genotyping of ten microsatellites that flank CCDC39 and span ~9 Mb of the disease locus supports a founder effect for three of the mutations and/or alterations (p.Thr358GlnfsX3, p.Ser786IlefsX33 and c.357+1G>C). We found the p.Glu731AsnfsX31 alteration on a shared haplotype in three families, but on a distinct haplotype in the fourth family (DCP91), which suggests a recurrent event (Supplementary Fig. 7).

The PCD phenotype of individuals with recessive CCDC39 mutations is characterized by chronic upper and lower airway infections that cause severe morbidity. Nine cases (41%) showed situs solitus and ten cases (45%) had situs inversus, whereas three cases (14%) had heterotaxia. Two of the cases with heterotaxia had documented polysplenia (Ivemark syndrome; MIM208530). This is consistent with previous reports that randomization of left-right asymmetry not only results in situs solitus or situs inversus but can also cause situs ambiguous, including Ivemark syndrome12,13. Four affected males had oligoasthenospermia.

To determine whether CCDC39 mutations underlie PCD with distinct ultrastructural defects or heterotaxia in the absence of respiratory symptoms, we used massive parallel sequencing to scan the 20 coding exons for mutations in 24 independent cases of PCD with absence of inner dynein arms only (6 cases) or absence of both inner and outer dynein arms (18 cases) without axonemal disorganization, and in 216 sporadic heterotaxia cases and 216 ethnically matched controls from the United States (Supplementary Note). We amplified 25 ~250-bp amplicons that spanned the 20 CCDC39 exons from DNA pools of ~20 cases or controls, mixed and sequenced on a Roche FLX instrument. The sensitivity and specificity of a similar protocol have been estimated at 83% and 98%, respectively (Y.M. & M.G., unpublished data). Contrary to PCD cases with absence of inner dynein arms and axonemal disorganization, we detected no nonsense, frameshift or splice site variants in CCDC39 in these cohorts.

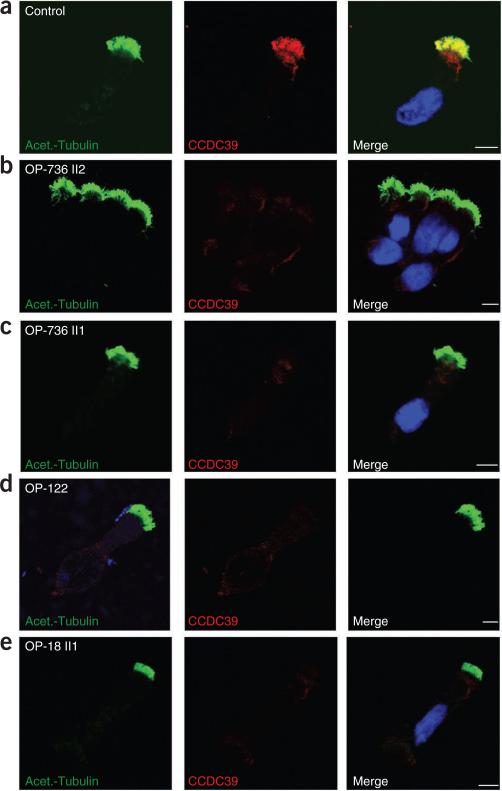

To gain insights into CCDC39 function, we analyzed its expression at the protein level. In protein blotting, antibodies to CCDC39 recognized a band of the expected size (~110 kD) in extracts from respiratory epithelial cells of a control subject but not of a CCDC39-deficient individual (Supplementary Fig. 8). High-resolution immunofluorescence analysis of respiratory cells showed predominant axonemal staining in controls (in agreement with the mass spectrometry analyses of purified flagella of Chlamydomonas7) but not in cells containing mutations in CCDC39 (Fig. 4).

Subcellular localization of CCDC39 in respiratory epithelial cells from individuals with PCD carrying CCDC39 mutations. Axoneme-specific antibodies against acetylated α-tubulin (green) were used as the control. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). (a) In respiratory epithelial cells from healthy probands, CCDC39 (red) localized predominantly along the entire length of the axonemes, as well as to the apical cytoplasm. (b–e) In respiratory epithelial cells from individuals OP-736 II2 (b), OP-736 II1 (c), OP-122 (d) and OP-18 II1 (e) carrying CCDC39 loss-of function mutations, CCDC39 was absent from the axoneme and markedly reduced in the apical cytoplasm. White scale bars, 5 μm.

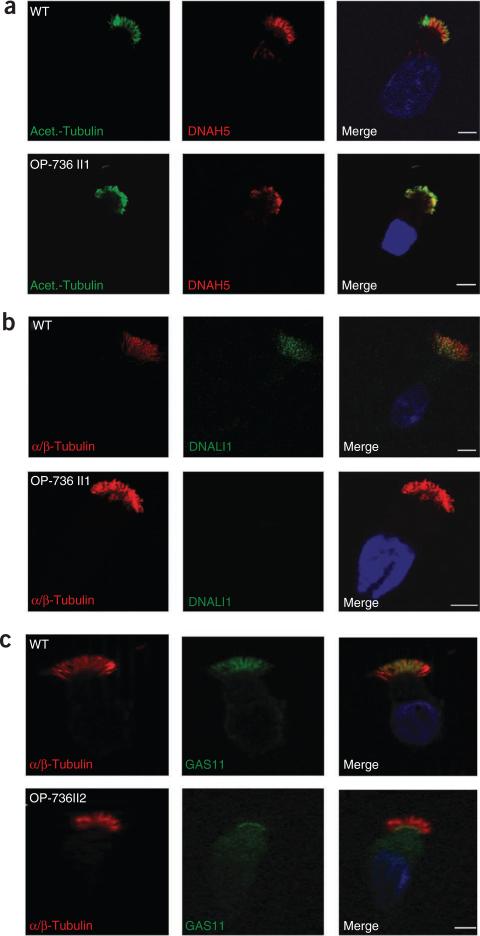

We used immunofluorescence to characterize the effect of CCDC39 deficiency on cilia structure. TEM analysis pointed toward defective inner dynein arms, nexin links and radial spokes but normal outer dynein arms (Fig. 3a). Because outer dynein arm complexes (ODA type 1 and type 2) vary along the length of ciliary axonemes and TEM cannot easily identify incomplete or regional outer dynein arm defects9,13, we used antibodies to the outer dynein arm components DNAH5 (type 1 and 2), DNAI2 (type 1 and 2) and DNAH9 (type 2) in five CCDC39-deficient individuals. The localization of outer dynein arm components was normal in CCDC39-deficient cilia (shown for DNAH5; Fig. 5). We then analyzed inner dynein arm components using antibodies to DNALI1. DNALI1, which is normally found throughout respiratory axonemes, was completely absent from CCDC39-deficient cilia (Fig. 5). The nexin links correspond to the dynein regulatory complex (DRC)14. Using antibodies to GAS11 (also known as GAS8), the human ortholog of the trypanin or DRC4 subunit of the protist DRC15–18, we found that GAS11 was localized along the whole axoneme in controls but was confined to the cytoplasm and ciliary base in CCDC39-deficient cilia (Fig. 5). qRT-PCR and protein blot analysis showed that the levels of GAS11 transcripts and protein were unaffected in individuals with PCD (Supplementary Fig. 9).

Subcellular localization of DNAH5, DNALI1 and GAS11 in respiratory epithelial cells from individuals with PCD carrying CCDC39 mutations. Immunofluorescence analyses of human respiratory epithelial cells using antibodies to the outer dynein arm heavy chain DNAH5 (a), the inner dynein arm component DNALI1 (b) and the DRC component GAS11 (c). Axoneme-specific antibodies to acetylated α-tubulin (a) or α/β-tubulin (b, c) were used as controls. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). The localization of DNAH5 (red) in respiratory epithelial cells from case OP-736 II1 was unchanged (a). DNALI1 (green) localized along the entire length of the axonemes of respiratory epithelial cells from healthy probands (b). In epithelial cells from case OP-736 II1, DNALI1 (green) was absent from the ciliary axonemes (b). In respiratory epithelial cells from healthy probands, GAS11 (green) localizes along the entire length of the axonemes (c). In respiratory epithelial cells from case OP-736 II1, GAS11 (green) was targeted to the ciliary base, where it accumulated (c). White scale bars, 5 μm.

We investigated the effect of CCDC39 deficiency on ciliary function. Optic microscopy on nasal or bronchial biopsies showed ciliary immotility in 17 of 22 cases with CCDC39 mutations and residual dyskinetic motility in the other 5 cases (DCP414, DCP323, DCP481, DCP552 and OP122). High-speed videomicroscopy analyses of respiratory cells obtained by nasal brushing biopsy (OP122) identified a beating pattern characterized by reduced amplitude with rigid axonemes that showed fast, flickery movements, which suggests defective beat regulation (Supplementary Videos 1 and 2). This pattern differs from that imparted by PCD variants (DNAH5, DNAI1, DNAI2, LRRC50 and C14orf104 (KTU)) that cause defects in the dynein arms and enable beat generation. In these cases, the cilia appear paralyzed but not rigid.

In summary, we have shown that CCDC39 is an axonemal protein whose absence results in failure to correctly assemble DNALI1-containing inner dynein arm complexes, the DRC and the radial spokes, thereby causing axonemal disorganization and dyskinetic beating. Loss-of-function mutations in CCDC40, which encodes another axonemal protein with coiled-coil domains, cause PCD with identical ultrastructural and biochemical defects (including ciliary depletion of CCDC39 and GAS11)19. Both CCDC39 and CCDC40 may be integral components of the DRC, whose precise composition remains to be defined14. Mutations in the Chlamydomonas PF2 gene (which encodes the coiled-coil domain-containing DRC4 component) also cause structural defects of both the DRC and inner dynein arms, with failure to assemble DRC components 3–7 (refs. 20–22). Therefore, as was proposed for PF2, CCDC39 could encode a protein that contributes to the stability of the DRC by interacting with one or several DRC subunits18. Alternatively, CCDC39 could participate in the transport of the inner dynein arms and DRC. Although the intraflagellar transport mechanism for components located at the interior of the axonemal shaft remains poorly understood, studies in Chlamydomonas have shown that components of the axonemal matrix are required for positioning inner axonemal components but not the outer dynein arms23. CCDC39, mutations of which affect the internal part of the axoneme with no apparent deleterious effect on outer dynein arms, could therefore be involved in this process. In support of this, several ciliary and centrosomal proteins involved in intraflagellar transport contain SMC-like domains, as does CCDC39 (Fig. 3b). As previously suggested24, SMC-like domains might represent signature sequences that are recognized during these transport processes.

We have also shown that dogs are useful for accelerating the identification of genes in which mutations cause inherited diseases in humans. Diseases that are characterized by locus heterogeneity in humans will almost always involve a single founder mutation in a given dog breed, which facilitates mapping. The highly inbred structure of the domestic dog population, combined with increasingly attentive medical care, has resulted in a long list of breed-specific inherited conditions that advantageously complements phenotype-driven screens in model organisms, including mice. Our results provide useful information for the counseling of previously orphan PCD families and open possibilities for the study of new PCD therapies in the dog model.

URLs. 1000 Genomes Project, http://www.1000genomes.org/.

METHODS

Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/naturegenetics/.

ONLINE METHODS

Positional identification of the PCD locus in dogs

We conducted SNP geno-typing of 5 affected and 15 healthy dogs with the Affymetrix v2.0 Canine array using standard procedures. We performed autozygosity mapping with ASSIST software25. We conducted mutation scanning by direct Sanger sequencing of amplicons spanning the CCDC39 exons and intron-exon boundaries obtained from genomic DNA using standard procedures and primers, provided in Supplementary Table 1. The relative abundance of mutant versus wildtype CCDC39 transcripts was measured by direct sequencing of RT-PCR products obtained from total RNA extracted from tracheal samples of a heterozygous animal using standard procedures and analysis of the sequence traces using PeakPicker26.

Morpholino-based ccdc39 suppression and in vivo rescue assay in zebrafish

Morpholinos targeting either the translation initiation AUG (tb-MO) or the splice donor site of D. rerio ccdc39 exon 9 (sb-MO; Gene Tools) were diluted to the appropriate concentrations using sterile, deionized water. We subsequently injected wildtype zebrafish embryos at the 1–2-cell stage with morpholino injection cocktails (batches of 50–100 embryos; the investigator was masked to injection) and reared them at 28 °C until fixation (14-somite embryos for RNA in situ hybridization) or live scoring for heart looping phenotypes at 36-h post fertilization. Embryos scored live were reared in N-phenylthiourea. For rescue experiments, the CCDC39 open reading frame (ORF) was PCR amplified from cDNA generated with oligo-dT–primed total RNA isolated from HEK293T cells and subsequently cloned into the pCR8/GW/TOPO vector (Invitrogen). pCR8/GW/TOPO vectors were then shuttled into the pCS2+ Gateway destination vector using LR clonase II mediated recombination (Invitrogen). Capped mRNA was in vitro transcribed from linearized pCS2+ CCDC39 using the SP6 mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's instructions and injected with sb-MO. RNA in situ experiments were conducted with embryos fixed in 4% (v/v) paraformaldehyde and hybridized with digoxygenin-labeled spaw riboprobe according to standard procedures. Images were captured at ×8 magnification using a Nikon SMZ1500 stereoscope equipped with a Digital Sight camera. For RT-PCR experiments, to show ccdc39 expression and knockdown efficiency of the sb-MO, we extracted total RNA from whole zebrafish embryos using Trizol (Invitrogen) primed with oligo-dT and performed reverse transcription with SuperScriptIII reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) to generate cDNA for subsequent PCR amplification.

Analyses of human CCDC39

Primers for (i) PCR and sequencing of the 20 coding exons and splice junctions of CCDC39, (ii) microsatellite haplotype analysis and (iii) identification of the c.1167+1261A>G mutation are available in Supplementary Table 1. For qRT-PCR analysis, 2 μg of total RNA from different human tissues (Takara Bio Europe/Clontech) were primed with 2.5 mM of oligo-dT and then subjected to reverse transcription with the Reverse Transcriptor kit from Roche following the manufacturer's instructions. cDNAs were amplified in the light Cycler LC480 (Roche/Boehringer Mannheim) with the LC480 probe master mix (Roche) using a forward primer in exon 6 and a reverse primer in exon 7. The primers used to amplify transcripts from other PCD genes expressed in nasal brushing samples (C14orf104 (KTU), LRRC50, GAS11, DNAI1 and DNAI2) are available on request. The ubiquitously expressed ERCC3 gene was used as an internal control.

Transmission electron microscopy

The biopsies were taken from the middle turbinate (for human tissue). The sample of nasal mucosa was fixed in 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer at 4 °C, washed overnight and postfixed in 1% (v/v) osmium tetroxide. After dehydration, the samples were embedded in a mixture of propylene oxide and epoxy resin. After polymerization, several resin sections were cut using an ultra-microtome. The sections were picked up onto copper grids. The sections were then stained with Reynold's lead citrate. TEM was performed with a Philips CM10.

In situ hybridization

We used a 1,272-bp probe mainly comprising the 3′ untranslated region of Ccdc39 (NM_026222.2) that we obtained by cDNA amplification from a mouse lung cDNA library (Marathon cDNA amplification kit, Clontech) and cloning into pBluescript. In situ hybridization analyses of whole mouse embryos (E7.5–E11.5) and embryonic (E14.5 and E16.5) and adult kidney sections were performed using a digoxigenin-labeled antisense riboprobe derived from mouse Ccdc39 cDNA as described in a published modification27,28. Color reactions were extended up to 4 d to visualize the weak expression in the node. Specimens were transferred into 80% glycerol and photographed using a Leica DC200 digital camera on a Leica M420 photo-microscope or under Nomarski optic using a Fujix digital camera HC300Z on a Zeiss Axioplan.

Generation of GAS11-specific antibodies

Antibodies were raised against the full-length protein of GAS11 (NP_001472.1). The corresponding cDNA fragment, which we obtained by cDNA amplification on a human testis cDNA library (Marathon cDNA amplification kit, Clontech), was cloned into pET-21a(+) (Novagen) and expressed as a HIS fusion protein in Escherichia coli. The purified protein was used to immunize mice. The monoclonal antibody was affinity column purified using protein G columns (Prochem).

Immunofluorescence analyses

Respiratory epithelial cells were obtained by nasal brush biopsy (Engelbrecht Medicine and Laboratory Technology) and suspended in cell culture medium. Samples were spread onto glass slides, air dried and stored at –80 °C until use. Cells were treated with 4% paraformaldehyde, 0.2% Triton-X 100 and 1% skim milk (all percentages are v/v) before incubation with primary (at least 3 h at room temperature (18–20 °C) or overnight at 4 °C) and secondary (30 min at room temperature) antibodies. Appropriate controls were performed omitting the primary antibodies. Monoclonal anti-DNALI1 antibody and polyclonal anti-DNAH5 antibodies were as reported9,13. Polyclonal rabbit CCDC39 was from Sigma. Polyclonal rabbit anti-α/β-tubulin was from Cell Signaling Technology, and monoclonal mouse anti-acetylated-α-tubulin antibody and polyclonal rabbit anti-CCDC39 antibodies were from Sigma. Highly cross-adsorbed secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 488, Alexa Fluor 546) were from Molecular Probes (Invitrogen). DNA was stained with Hoechst 33342 (Sigma). Immunofluorescence images were taken with a Zeiss Apotome Axiovert 200 and processed with AxioVision 4.7.2.

Immunoblotting

Protein extracts were prepared from human respiratory epithelial cell cultures as described13. Proteins were separated on a NuPAGE 4–12% bis-tris gel (Invitrogen) and blotted onto a PVDF membrane (Amersham). The blot was processed for ECL plus (GE Healthcare) detection using GAS11 (1:200), CCDC39 (1:250; Atlas Antibodies), GAPDH (1:1,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit-HRP (1:3,000) and mouse-HRP (1:5,000) antibodies (GE Healthcare).

High-speed video analyses of ciliary beat in human cells

Ciliary beat was assessed with the SAVA system (Sisson-Ammons Video Analysis of ciliary beat frequency)29. Trans-nasal brush biopsies were rinsed in cell culture medium and immediately viewed with an Olympus IMT-2 inverted phase-contrast microscope with a Redlake ES-310 Turbo monochrome high-speed video camera and a ×40 objective. Digital image sampling was performed at 125 frames per second and at 640 × 480 pixel resolution. The ciliary beat pattern was evaluated on slow motion playbacks.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the European Union (LUPA IP) and from the Police Scientifique Fédérale de Belgique (GENFUNC PAI) (to M.G.), from the Legs Poix from the Chancellerie des Universités, the Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris (PHRC AOM06053, P060245) and the Agence Nationale pour la Recherche (ANR-05-MRAR-022-01) (to S.A.), the US National Institutes of Health (HD04260, DK072301 and DK075972 (to N.K.) and DK079541 (to E.E.D.)) and by grants from the “Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft” DFG Om 6/4, GRK1104, SFB592, and the European Community (EU-CILIA; SYS-CILIA) (to H.O.). A.C.M. is a fellow from the FRIA. N.K. is the Jean and George W. Brumley Professor. Y.M. benefits from a postdoctoral fellowship to study abroad from the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS). We thank the Bobtail breeders for assistance; patients and their family members whose cooperation made this study possible; all referring physicians; the German patient support group “Kartagener Syndrom und Primaere Ciliaere Dyskinesie e.V.”; K. Nakamura and the GIGA-R genomics platform for their contribution to sequencing; E. Ostrander for samples from healthy Old English Sheepdogs; the Unité de Recherche Clinique (URC) Est (AP-HP, Hôpital Saint-Antoine, Paris, France) for support; and A. Heer, C. Reinhard, C. Kopp, K. Sutter, M. Petry, C. Tessmer, A.-M. Vojtek and S. Franz for technical assistance.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

The positional cloning of CCDC39 in the dog was performed by A.-C.M. and G.B. Genome-wide SNP genotyping was conducted at CNG under supervision of M. Lathrop and D.Z. Mining the ciliome databases was conducted by E.E.D. Experiments in the zebrafish were conducted by E.E.D. In situ hybridization in the mouse was conducted by A.K. and H.O. qRT-PCR on human samples was conducted by M. Legendre, P.D., G.M. and H.T. Sequencing of CCDC39 in human subjects, including high-throughput sequencing, was conducted by A.-C.M., G.B., Y.M., A.B.-H., M. Legendre, E.E., P.D., G.M. and H.T. Identifying the p.Glu390SerfsX6 mutation was realized by M. Legendre, P.D., G.M. and H.T. Haplotype analysis to determine founder status of CCDC39 mutations was conducted by M. Legendre and P.D. TEM analysis was conducted by M.J. (dog), E.E. and D.E. (French cohort), and by K.G.N., J.K.M., H.O. and routine laboratories (German cohort). High-resolution immunofluorescence analyses were done by A.B.-H., M.F., J.H. and N.T.L. Immunoblotting analyses were done by A.B.-H. High-speed video analyses were conducted by H.O., N.T.L. and A.B.-H. Monoclonal anti-GAS11 antibody was produced by A.B.-H. and H.Z. Polyclonal anti-GAS11 antibodies were provided by K.H. and R.C. Clinical examination and collection of the canine PCD cases was conducted by F.B., C.C. and S.D. M.G., A.-S.L., N.K., H.O. and S.A. designed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. All remaining authors as well as H.O., K.G.N. and J.K.M. examined and contributed samples from individuals with PCD or heterotaxia.

Accession codes. All accession codes are available in GenBank under the following accession codes: dog CCDC39 cDNA, XM_545213.2; human CCDC39 cDNA, NM_181426.1; mouse Ccdc39 cDNA, NM_026222.2; and zebrafish ccdc39 cDNA, XM_677617.4.

Supplementary information is available on the Nature Genetics website.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.726

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc3509786?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Article citations

Ependymal cells: roles in central nervous system infections and therapeutic application.

J Neuroinflammation, 21(1):255, 09 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39385253 | PMCID: PMC11465851

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Chronic lung inflammation and CK14+ basal cell proliferation induce persistent alveolar-bronchiolization in SARS-CoV-2-infected hamsters.

EBioMedicine, 108:105363, 25 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39326207 | PMCID: PMC11470415

Non-coding cause of congenital heart defects: Abnormal RNA splicing with multiple isoforms as a mechanism for heterotaxy.

HGG Adv, 5(4):100353, 12 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39275801 | PMCID: PMC11470249

Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia Associated Disease-Causing Variants in CCDC39 and CCDC40 Cause Axonemal Absence of Inner Dynein Arm Heavy Chains DNAH1, DNAH6, and DNAH7.

Cells, 13(14):1200, 15 Jul 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39056782 | PMCID: PMC11274998

Transcriptional analysis of primary ciliary dyskinesia airway cells reveals a dedicated cilia glutathione pathway.

JCI Insight, 9(17):e180198, 23 Jul 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39042459 | PMCID: PMC11385084

Go to all (200) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

RefSeq - NCBI Reference Sequence Database (2)

- (1 citation) RefSeq - XM_545213.2

- (1 citation) RefSeq - XM_677617.4

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

C11orf70 Mutations Disrupting the Intraflagellar Transport-Dependent Assembly of Multiple Axonemal Dyneins Cause Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia.

Am J Hum Genet, 102(5):956-972, 01 May 2018

Cited by: 30 articles | PMID: 29727692 | PMCID: PMC5986720

Defects in the cytoplasmic assembly of axonemal dynein arms cause morphological abnormalities and dysmotility in sperm cells leading to male infertility.

PLoS Genet, 17(2):e1009306, 26 Feb 2021

Cited by: 40 articles | PMID: 33635866 | PMCID: PMC7909641

Mutations in SPAG1 cause primary ciliary dyskinesia associated with defective outer and inner dynein arms.

Am J Hum Genet, 93(4):711-720, 19 Sep 2013

Cited by: 84 articles | PMID: 24055112 | PMCID: PMC3791252

[Cilia ultrastructural and gene variation of primary ciliary dyskinesia: report of three cases and literatures review].

Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi, 56(2):134-137, 01 Feb 2018

Cited by: 8 articles | PMID: 29429202

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NIAID NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: R01 AI052348

NICHD NIH HHS (2)

Grant ID: HD04260

Grant ID: R01 HD042601

NIDDK NIH HHS (6)

Grant ID: R01 DK072301

Grant ID: R01 DK075972

Grant ID: DK075972

Grant ID: DK072301

Grant ID: DK079541

Grant ID: F32 DK079541