Abstract

Background

Arthralgia is common in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors (BCS) who are receiving aromatase inhibitors (AIs). The objective of this study was to evaluate the perceived onset, characteristics, and risk factors for AI-related arthralgia (AIA).Methods

In a cross-sectional survey of postmenopausal BCS who were receiving adjuvant AI therapy at a university-based oncology clinic, patient-reported attribution of AIs as a cause of joint pain was used as the primary outcome. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to evaluate risk factors.Results

Among 300 survey respondents, 139 (47%) attributed AI as a cause of their current arthralgia. Of those patients, 74% recognized the onset of AIA within 3 months of starting medication, and 67% rated joint pain as moderate or severe in the previous 7 days. In multivariate logistic regression analyses, the time since last menstrual period (LMP) was the only significant predictor of AIA. Controlling for covariates, the women who had their LMP within 5 years had the highest probability of reporting AIA (73%), whereas those who had their LMP > or =10 years previously had the lowest probability of reporting AIA (35%; adjusted odds radio, 3.39; 95% confidence interval, 1.21-9.44; P = .02). Wrists/hands, ankles/feet, elbows, and knees appeared to be associated more strongly with AI-related symptoms than non-AI-related joint symptoms (all P < .01).Conclusions

AIA was common, began within the first 3 months of therapy in most patients, and appeared to be related inversely to the length of time since cessation of menstrual function. These findings suggest that estrogen withdrawal may play a role in the mechanism of this disorder.Free full text

Patterns and Risk Factors Associated with Aromatase Inhibitor Related Arthralgia Among Breast Cancer Survivors

Abstract

Purpose

Arthralgia is common in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors (BCS) receiving aromatase inhibitors (AI). This study aims to evaluate the perceived onset, characteristics, and risk factors for AI-related arthralgia (AIA).

Patients and Methods

We performed a cross-sectional survey of postmenopausal BCS receiving adjuvant AI therapy at a university-based oncology clinic. Patient-reported attribution of AIs as a cause of joint pain was used as the primary outcome. Multivariate logistic regression analyses (MVA) were performed to evaluate risk factor(s).

Results

Among 300 participants, 139 (47%) attributed AI as a cause of their current arthralgia. Of these patients, 74% recognized onset of AIA within three months since medication initiation, and 67% rated joint pain moderate or severe in the previous seven days. In a MVA, time since last menstrual period (LMP) was the only significant predictor of AIA. Controlling for covariates, those who had LMP within five years had the highest probability of reporting AIA (73%), while those with LMP beyond ten years had the lowest (35%; adjusted odds radio, 3.39, 95% confidence interval, 1.21-9.44, P=0.02). Wrists/hands, ankles/feet, elbows and knees appeared to be more strongly associated with AI-related symptoms than non-AI related joint symptoms (all p<0.01).

Conclusions

AIA is common, begins within the first three months of therapy in most patients, and appears to be inversely related to the length of time since cessation of menstrual function. These findings suggest that estrogen withdrawal may play a role in the mechanism of this disorder.

Introduction

Aromatase inhibitors (AIs) have become an indispensable part of standard adjuvant hormonal therapy for hundreds of thousands of postmenopausal women with hormone receptor positive invasive breast cancer. Large adjuvant randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have found improvements in disease-free survival rates as high as 40%, greater than rates observed with tamoxifen.1-4 Their utility is also being investigated in combination with ovarian suppression in premenopausal women with breast cancer and among healthy postmenopausal women for prevention of breast cancer.5

With the increase in its use and potential indications, AI-related arthralgia is emerging as a major source of symptom burden among its users,6, 7 with a 28% relative increase compared to placebo (21.3% for AI vs. 16.6%, p<0.001).2 In trials comparing AIs to tamoxifen, the incidence of arthralgia is substantially larger in AI groups (5-36%) than in tamoxifen groups (4-29%); although the rates vary.8, 9 Arthralgia affects daily function and appears to decrease adherence leading to premature discontinuation of AIs.10 One Canadian chart review of 50 patients found that 22% of patients discontinued adjuvant AI therapy because of toxicity, including muscle and joint symptoms.11 A study using a health claims dataset found that one in five AI users filled less than 80% of their prescribed AI medications.12

Because of the significant impact of AI-related arthralgia on quality of life, adherence behavior and potential survival benefit derived from AIs, research is needed to better define the characteristics of AI-related arthralgia to guide future interventions. Thus, the specific aims of this study were to: 1) Define the rate of AI as a cause for arthralgia in early stage breast cancer survivors who currently receive AIs; 2) Describe the perceived onset of AI-related arthralgia in relationship to initiating AI therapy; 3) Identify the demographic and clinical risk factors associated with AI-related arthralgia; and 4) Explore the joint specific presentation of AI-related arthralgia.

Methods

Study Design and Patient Population

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of breast cancer patients receiving care at the Rowan Breast Cancer Center of the Abramson Cancer Center of the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, PA) between April and October 2007. Potential participants included all postmenopausal women with a history of histologically confirmed stage I to III, hormone receptor-positive breast cancer who were currently taking a third-generation aromatase inhibitor (anastrozole, letrozole, or exemestane), completed chemotherapy or radiotherapy at least one month prior to enrollment, and had the ability to understand and provide informed consent in English. Research assistants obtained permission from the treating oncologist, screened medical records and approached potential study subjects for enrollment at their regular follow-up appointments. After informed consent was obtained, each participant was given a self administered survey. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania and the Scientific Review and Monitoring Committee of the Abramson Cancer Center.

Outcome Measurement

Primary outcome measures included patient self-report of joint pain, particularly self-reported joint pain attributed to AIs, severity of joint pain, and clinical characteristics (i.e., onset, location) of joint pain. Because AI-related arthralgia is a relatively new clinical phenomenon, we developed a questionnaire based on limited literature, clinical expert opinion, and patient input. We then piloted the questionnaire with 16 BCS receiving AIs to determine the clarity of items and patient relevance, as well as to identify additional content. Given that arthralgia in this population may be multifactorial,13 we instructed participants to attribute causes for their arthralgia by asking, “What do you believe are the sources of your current joint symptoms?” The response options included “Prior osteoarthritis”, “aromatase inhibitors”, “other medical conditions”, “other medications”, and “others”. Respondents were able to choose more than one option. To generate the main outcome variable of AI-related arthralgia, any participant who selected “aromatase inhibitors” as a cause of their current joint symptoms were considered to have AI-related arthralgia, and all others did not. This dichotomous variable was used as the main outcome in both bivariate and multivariate analyses.

To assess symptom severity, participants were asked to rate their joint pain over the preceding seven days on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “none” to “very severe.” To evaluate perceived onset, we asked the participants “If you are experiencing joint symptoms which you think are related to aromatase inhibitors, when did you first recognize the symptoms after starting to take the medications?” Response options ranged from “right away” and “within the first week” to “after six months”. To evaluate which joints were most commonly affected in those with AI-related arthralgia, we asked participants two questions. First, the participant was asked to indicate all joints with pain in the preceding 24 hours, and second, to indicate in which single joint the participant experienced the most pain in the preceding 24 hours.

Information of covariates was collected, including age, race, ethnicity, education level and employment status. Clinical and treatment characteristics were assessed by either self-report (i.e. timing of the last menstrual period [LMP], height, weight before breast cancer and current weight, and co-morbidities including prior arthritis) or medical record abstraction (i.e. stage, chemotherapy, tamoxifen use, aromatase inhibitor use).

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using STATA 9.0 for Windows (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX). We initially performed descriptive statistics and bivariable analyses. We then developed multivariate logistic regression to determine the relative impact of each variable on AI-related arthralgia. Variables that were not significant at the 0.20 level in the bivariable analyses were not included. To explore how AI-related arthralgia may impact specific joints differently, we then performed chi-square analyses to compare individuals with AI-related arthralgia and those without. Statistical tests were two-sided with p<0.05 indicating significance except the exploratory analyses for joint-specific arthralgias. Because multiple comparisons were used in these analyses, we lowered the statistical significance to be less than 0.01 to indicate significance.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Of 484 consecutive patients screened, 50 (10%) were ineligible due to discontinuation of AI therapy prior to screening, 45 (9%) had metastatic disease, 64 (13%) did not keep their scheduled appointment, and 25 (5%) declined enrollment, leaving a total of 300 participants. Characteristics of the study population are listed in Table 1. Among the 300 survey participants, the mean age was 61 and although the majority (84%) was non-Hispanic white, a substantial proportion (13%) was non-Hispanic black. In the analysis, we combined the race categories to white and non-white. Among the participants, 51(17.6%) reported having had their LMP within the five years prior to study enrollment, 95 (32.8%) had LMP between five and ten years, and 144 (49.7%) had LMP greater than ten years prior to enrollment. One hundred and seventy three (57.7%) patients were taking anastrozole, 69 (23%) were taking letrozole, and 58 (19%) were taking exemestane (Table 2).

Table 1

| No. participated | With AI-related Pain | %+ | P-value++ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 300 | 139 | ||

| Age, years | 0.001 | |||

<55 <55 | 73 | 45 | 62 | |

55-65 55-65 | 131 | 62 | 47 | |

>65 >65 | 96 | 32 | 33 | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.13 | |||

White White | 253 | 122 | 47 | |

Non-white* Non-white* | 47 | 17 | 36 | |

| Educational Level | 0.4 | |||

High school or less High school or less | 122 | 52 | 43 | |

College College | 76 | 34 | 45 | |

Graduate or professional school Graduate or professional school | 101 | 52 | 52 | |

| Employment | 0.002 | |||

Full-time Full-time | 114 | 67 | 59 | |

Part-time Part-time | 40 | 19 | 48 | |

Not currently Not currently | 142 | 52 | 37 | |

Table 2

| No. participated | With AI-related Pain | %* | P-value++ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 300 | 139 | ||

| Years since LMP | <0.001 | |||

<5 <5 | 51 | 37 | 73 | |

5-10 5-10 | 95 | 45 | 47 | |

>10 >10 | 144 | 52 | 36 | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 0.76 | |||

<25 <25 | 112 | 50 | 45 | |

25-30 25-30 | 93 | 42 | 45 | |

>30 >30 | 95 | 47 | 50 | |

| Stage | 0.45 | |||

I I | 100 | 42 | 42 | |

II II | 142 | 71 | 50 | |

III III | 32 | 14 | 44 | |

| Chemotherapy | 0.07 | |||

None None | 111 | 43 | 39 | |

Chemotherapy, but no Taxane Chemotherapy, but no Taxane | 101 | 49 | 49 | |

Chemotherapy included Taxane Chemotherapy included Taxane | 78 | 43 | 55 | |

| Prior tamoxifen | 0.63 | |||

None None | 151 | 72 | 48 | |

Yes Yes | 136 | 61 | 45 | |

| Aromatase inhibitor | 0.76 | |||

Anastrozole (Arimidex) Anastrozole (Arimidex) | 173 | 77 | 45 | |

Letrozole (Femara) Letrozole (Femara) | 69 | 34 | 49 | |

Exemestane (Aromasin) Exemestane (Aromasin) | 58 | 28 | 48 | |

| Duration of AI therapy, years | 0.78 | |||

<1 <1 | 126 | 60 | 48 | |

1-3 1-3 | 79 | 34 | 43 | |

>3 >3 | 86 | 41 | 48 | |

| Comorbidity | 0.1 | |||

None None | 87 | 47 | 54 | |

One One | 103 | 49 | 48 | |

Two or more Two or more | 110 | 43 | 39 | |

| Prior arthritis | 0.36 | |||

None None | 197 | 95 | 48 | |

Yes Yes | 103 | 44 | 43 | |

| Weight gain since breast cancer | 0.1 | |||

No weight gain No weight gain | 133 | 52 | 39 | |

10 lbs or less 10 lbs or less | 83 | 41 | 49 | |

greater than 10 lbs greater than 10 lbs | 81 | 43 | 53 | |

Perceived rate and severity of AI-related arthralgia

Among the 300 participants, 139 (46.3%) believed AI to be a source of their current joint symptoms, while 91 (30.3%) attributed joint symptoms to prior osteoarthritis, 97 (32.3%) attributed joint symptoms to other medical conditions (e.g. fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, spinal stenosis), 13 (4.3%) to other medications (e.g. statin, paclitaxel), and 63 (21.0%) attributed joint symptoms to other causes (e.g. mainly “aging”, injury). Compared to those without AI-related arthralgia, those who reported AI-related arthralgia had significantly more severe pain in the preceding seven days (p<0.001). For example, 26% of those with AI-related arthralgia had pain rated severe or very severe while only 11% among those without AI-related arthralgia did. Among those reporting AI-related arthralgia, 67% rated pain of moderate or greater severity.

Perceived onset of AI-related arthralgia

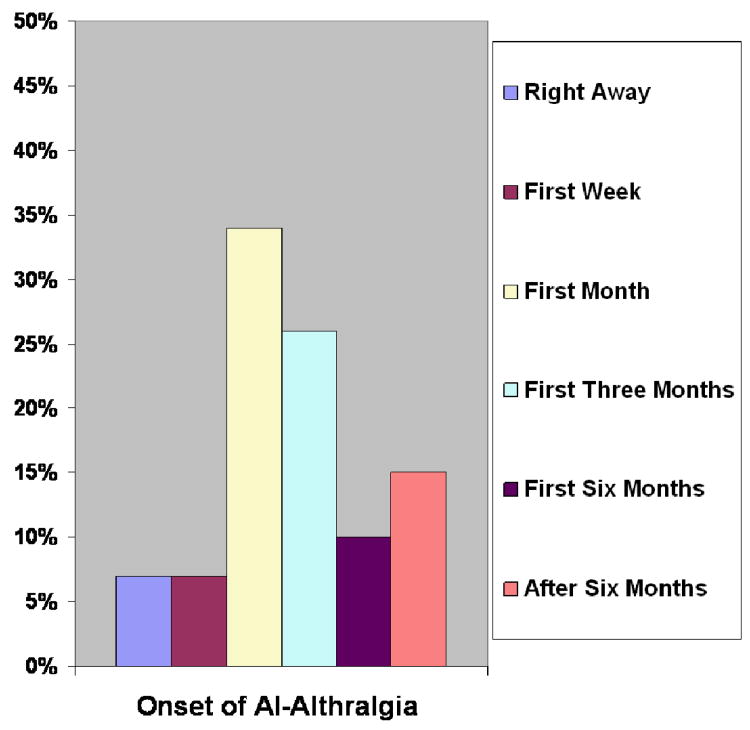

Among the 139 participants with AI-related arthralgia, 10(7%) noticed the onset of arthralgia due to AI right away after starting the medication, nine (7%) within the first week, 46(34%) within the remaining first month, 35 (26%) within the first three months, 14 (10%) within the first six months, 21 (15%) after the first six months, and four (3%) did not provide a response to this question (see Figure 1). Thus, about three-quarters of AI-related arthralgia has been noticed within the first three months from the onset of the therapy.

Factors associated with AI-related arthralgia

In bivariable analyses, younger age, full-time employment status, and fewer years since LMP were associated with greater AI-related arthralgia, (see Table 1 and Table 2). Nevertheless, in the multivariate regression model (adjusting for variables selected from the bivariable analyses), time since LMP was the only factor that was associated with reporting AI-related arthralgia. Women who had their LMP within the last five years were significantly more likely to report AI-related arthralgia than those women who had LMP greater than ten years, adjusted OR = 3.39 (95% CI, 1.21-9.44), P=0.02. Adjusting for covariates, the probabilities (95% CI) of reporting AI-related arthralgia were: 0.73 (0.59-0.84) for LMP within five years, 0.48 (0.37-0.58) for LMP between five and ten years, and 0.35 (0.28-0.44) for LMP greater than ten years.

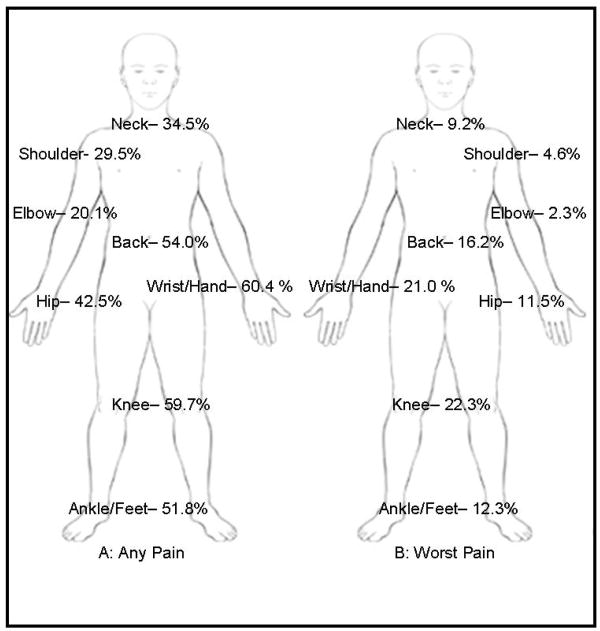

Joint Specific AI-related Arthralgia

As arthralgia in different joints may have different underlying patho-physiologic mechanisms and differential impact on function and quality of life, we examined manifestations of AI-related arthralgia in specific joints. The most common sites of joint pain in individuals with AI-related arthralgia were wrist/hand (60.4%), knee (59.7%), back (54.0%), ankle/foot (51.8%), and hip (42.5%) in descending order of endorsement (see Figure 2A). The average number of joints affected in patients with joint pain was greater in individuals with AI-related arthralgia than those without (3.5 vs. 2.1 p<0.001). The worst arthralgia was the most common in knee (22.3%) and wrist/hand (21.0%), followed by back (16.2%) ankle/foot (12.3%) and hip (11.5%), see Figure 2B. As compared to those without AI-related arthralgia, those patients who reported AI-related arthralgia were significantly more likely to report arthralgia in wrist/hand, relative risk (RR), 1.97 (95% CI, 1.53-2.54); elbow, RR, 1.79 (95% CI, 1.42-2.26); ankle/feet, RR, 1.66 (95% CI, 1.31-2.10); and knee, RR, 1.54 (95% CI, 1.20-1.99), see Table 4. Interestingly, joints that are distal for the torso may have greater pain as related to AIs (suggested by increasing RR).

Table 4

| Joint Location With Pain | RR (95% CI)* | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Upper extremity | ||

Shoulder Shoulder | 1.17 (0.90-1.52) | 0.25 |

Elbow Elbow | 1.79 (1.42-2.26) | <0.001 |

Wrist/hand Wrist/hand | 1.97 (1.53-2.54) | <0.001 |

| Core body | ||

Neck Neck | 1.23 (.96-1.57) | 0.11 |

Back Back | 1.49 (1.17-1.90 | 0.001 |

| Lower extremity | ||

Hip Hip | 1.45 (1.15-1.84) | 0.003 |

Knee Knee | 1.54 (1.20-1.99) | <0.001 |

Ankle/Feet Ankle/Feet | 1.66 (1.31-2.10) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: RR-relative risk, CI-confidence interval

Discussion

In this paper, we present a comprehensive evaluation of AI-related arthralgia based on patients' perceptions. Despite the multi-factorial nature of arthralgia in a postmenopausal BCS population, close to half of our sample reported experiencing AI-related arthralgia. Most patients recognized arthralgia within the first three months from initiation of AIs and over 60% reported current arthralgia to be moderate or severe. Controlling for clinical and demographic factors, time from LMP was inversely related to report of AI-related arthralgia, with those experiencing menopause in the five years prior to enrollment having a three-fold higher likelihood of developing AI-related arthralgia compared to those who were at least ten years out from menopause. Furthermore, despite the fact that multiple joints can be involved, wrists/hands, elbows, ankles/feet, and knees may be particularly vulnerable to AI-related arthralgia.

Recent data suggest that the prevalence of AI-related arthralgia is higher outside of clinical trials.10, 14 In a survey among 200 BCS receiving AIs, 94 (47%) reported having AI-related arthralgia, and of these patients, 50% had new onset of joint pain following initiation of AI, and 50% reported that their pain worsened since starting AIs.15 Our study, like others that have examined this issue in a practice setting outside a clinical trial, is subject to selection bias. Ten percent of individuals who stopped AIs were not captured by this survey. While our 5% refusal rate was low, it is possible that those patients refusing to participate were relatively asymptomatic, and may have viewed the survey as less relevant. Additionally, as patients with prior arthritic conditions may opt not to initiate AIs, our study may underestimate the degree of AI-related arthralgia in patients with pre-existing arthritis. Finally, since our study relied on self-report, some degree of misclassification bias due to patients' perception exists; however, for subjective symptoms like AI-related arthralgia, patient-reported-outcome is considered the gold standard. Despite such limitations, our estimated prevalence of ongoing AI-related arthralgia was almost identical to that of Crew et al, suggesting the prevalence is credible.15 Furthermore, the location(s) where patients reported joint pain were also very similar to that of Crew.15

Our findings regarding the temporal onset of symptoms confirm a similar observation in a small case series,10 and these data justify and inform prospective studies. Measuring perceived onset of AI-related arthralgia may be subject to recall bias as the actual event occurred months if not years prior to the study. As most patients reported onset of AI-related arthralgia within three months from initiation of AIs, more intense follow-up and data collection during this window of opportunity may help evaluate the true timing of the development of AI-related arthralgia as well as elucidate the potential biological mechanism. This data may further suggest clinicians have early follow-up with patients who initiate AIs to discuss the potential onset of arthralgia, so that timely detection and management can occur to prevent premature discontinuation,16 which has been documented to be as high as 20% in some studies.14, 17

Risk factors for AI-arthralgia are not well characterized. In the only other study to report on this issue in clinical practice, prior tamoxifen use and higher weight appeared to be associated with a lower risk of AI-arthralgia, whereas receiving taxane chemotherapy was associated with increased risk.15 While these were not significant risk factors in our population, we did see a trend for the use of taxanes (p=0.07). The differences in risk factor profiles between the two studies may be a result of sample size, or subtle underlying differences in the study populations. For example, our study population was younger, with a greater population of patients under age 55. These findings emphasize the need to replicate such studies in diverse populations to determine whether such associations are robust, reproducible or population specific.

In our study, interval from menopause (measured as time from LMP) was the only significant factor that was associated with AI-related arthralgia. We hypothesize that those individuals who have most recently transitioned into menopause may have higher residual circulating estrogen; thus, the exposure to AIs may cause a more precipitous absolute drop in estrogen, leading to greater symptom experience. Several recent publications have cited estrogen deprivation caused by AIs as a potential mechanism for this clinical phenomenon.6, 8, 9, 18 The effect of estrogen withdrawal on the clinical syndrome of AI-arthralgia may be multifactorial,19 acting both centrally and peripherally.8 Centrally, acutely reducing estrogen levels may decrease endogenous opioid generation, thereby decreasing pain threshold. Thus, some individuals with subclinical osteoarthritis may experience a rise in AI-associated symtoms due to decreased pain threshold and increased awareness of arthralgia, leading some patients to attribute the “cause” of arthralgia to AIs.20 Peripherally, estrogen withdrawal may upregulate inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α, which may accelerate bone loss and bone aging, thereby leading to pain.21 Prospectively measuring appropriate biomarkers (e.g. reproductive hormone, drug metabolites, and inflammatory cytokines) in addition to subjective symptom measurement may help elucidate the biology underlying this unexplained clinical phenomenon.

Increasing evidence suggests that those women who may benefit from AI the most may also be the ones who experience the greatest degree of adverse events. Freedman et al. found that younger age was a predictor of benefiting from AIs in a cohort study in women who finished radiation therapy and tamoxifen.22 Cuzick et al. recently demonstrated that those with treatment emergent joint and vasomotor symptoms during the first three months of AI-therapy were less likely to develop breast cancer recurrence in a retrospective analysis of the ATAC trial.23 Our findings underscore the need to develop mechanistically-based treatment options for these women to adequately address AI-related arthralgia so that they can optimally adhere to AIs to maximize the benefit of AIs while maintaining quality of life.

Finally, the pattern of joint pain at specific sites provides important data for both clinical care and future intervention development. As suggested by the rheumatology literature,24, 25 site-specific joint symptoms may have a vastly different impact on functions and quality of life; therefore treatment and rehabilitation may differ. Joint specific symptom and function measures need to be tested in this population to guide further evaluation and treatment development. Some limited self-reported data and clinical review suggest pain medications, supplements, and exercise may be helpful for arthralgia;8, 9, 15 although these are not confirmed by well-designed randomized controlled trials. Initial research is also underway to evaluate alternative approaches such as acupuncture for treating AI-related arthraligia.26, 27

In summary, this study sheds light on the early onset and pattern of arthralgia related to AIs and has identified interval from menopause as a novel risk factor for symptom development. Multidisciplinary translational research is critically needed to evaluate the etiology and potential therapeutic options for AI-related arthralgia.

Table 3

| Bivariable Analysis OR (95% CI) | P-value | Multivariate Analysis AOR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||||

<55 (Reference) <55 (Reference) | 1 | 1 | ||

55-65 55-65 | 0.56 (0.31-1.00) | 0.05 | 0.99 (0.44-2.21) | 0.97 |

>65 >65 | 0.31 (0.16-0.59) | <0.001 | 0.79 (0.27-2.32) | 0.67 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

White (Reference) White (Reference) | 1 | 1 | ||

Non-white* Non-white* | 0.61 (0.32-1.16) | 0.13 | 0.59 (0.27-1.27) | 0.18 |

| Employment | ||||

Full-time (Reference) Full-time (Reference) | 1 | 1 | ||

Part-time Part-time | 0.63 (0.31-1.31) | 0.22 | 0.63 (0.28-1.41) | 0.26 |

Not currently Not currently | 0.41 (0.24-0.67) | <0.001 | 0.62 (0.33-1.13) | 0.13 |

| Years since LMP | ||||

>10 (Reference) >10 (Reference) | 1 | 1 | ||

5-10 5-10 | 1.59 (0.94-2.70) | 0.08 | 1.10 (0.55-2.21) | 0.79 |

<5 <5 | 4.68 (2.32-9.44) | <0.001 | 3.39 (1.21-9.44) | 0.02 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||

None (Reference) None (Reference) | 1 | 1 | ||

Chemotherapy, but no Taxane Chemotherapy, but no Taxane | 1.49 (0.86-2.57) | 0.15 | 1.04 (0.55-1.97) | 0.89 |

Chemotherapy included Taxane Chemotherapy included Taxane | 1.94 (1.08-3.50) | 0.027 | 1.06 (0.52-2.16) | 0.88 |

| Comorbidity | ||||

None (Reference) None (Reference) | 1 | 1 | ||

One One | 0.77 (0.44-1.37) | 0.38 | 0.96 (0.50-1.86) | 0.91 |

Two or more Two or more | 0.55 (0.37-0.97) | 0.037 | 0.92 (0.47-1.81) | 0.8 |

| Weight gain since breast cancer | ||||

No weight gain (Reference) No weight gain (Reference) | 1 | 1 | ||

10 lbs or less 10 lbs or less | 1.52 (0.87-2.65) | 0.14 | 1.12 (0.61-2.07) | 0.71 |

greater than 10 lbs greater than 10 lbs | 1.76 (1.01-3.08) | 0.047 | 1.25 (0.65-2.38) | 0.5 |

Abbreviations: O.R.-odds ratio, C.I.-confidence interval, A.O.R.-adjusted odds ratio

Acknowledgments

This study is in part supported by grants from the American Cancer Society #IRG-78-002-30, the Lance Armstrong Foundation, and Pennsylvania Department of Aging. Dr. Mao is also supported by American Cancer Society CCCDA-08-107-01. The funding agency had no role in the design and conduct of this study. We would like to acknowledge the contributions of the Recruitment, Retention, and Outreach Core Facility of the Abramson Cancer Center for assisting with the development and implementation of the recruitment and retention plan. Sincere thanks also go to the patients, oncologists, nurse practitioners, and staff for their support of this study.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.24419

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1002/cncr.24419

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

A Cohort Study to Evaluate Genetic Predictors of Aromatase Inhibitor Musculoskeletal Symptoms: Results from ECOG-ACRIN E1Z11.

Clin Cancer Res, 30(13):2709-2718, 01 Jul 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38640040

Association of Aromatase Inhibitor-Induced Musculoskeletal Symptoms with Central Sensitization-Related Symptoms: A Cross-Sectional Study.

Breast Care (Basel), 19(4):207-214, 18 Jun 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39185132

Association between trajectories of adherence to endocrine therapy and risk of treated breast cancer recurrence among US nonmetastatic breast cancer survivors.

Br J Cancer, 130(12):1943-1950, 18 Apr 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38637603

Current and future advances in practice: aromatase inhibitor-induced arthralgia.

Rheumatol Adv Pract, 8(2):rkae024, 10 Apr 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38601139 | PMCID: PMC11003819

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Searching for Essential Genes and Targeted Drugs Common to Breast Cancer and Osteoarthritis.

Comb Chem High Throughput Screen, 27(2):238-255, 01 Jan 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37157194

Go to all (116) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

The time since last menstrual period is important as a clinical predictor for non-steroidal aromatase inhibitor-related arthralgia.

BMC Cancer, 11:436, 10 Oct 2011

Cited by: 20 articles | PMID: 21985669 | PMCID: PMC3198721

Time course of arthralgia among women initiating aromatase inhibitor therapy and a postmenopausal comparison group in a prospective cohort.

Cancer, 119(13):2375-2382, 10 Apr 2013

Cited by: 21 articles | PMID: 23575918 | PMCID: PMC3687009

Ageing perceptions and non-adherence to aromatase inhibitors among breast cancer survivors.

Eur J Cancer, 91:145-152, 09 Jan 2018

Cited by: 14 articles | PMID: 29329697 | PMCID: PMC5803454

Aromatase inhibitor-induced arthralgia: a review.

Ann Oncol, 24(6):1443-1449, 06 Mar 2013

Cited by: 104 articles | PMID: 23471104

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NCCIH NIH HHS (2)

Grant ID: K23 AT004112

Grant ID: K23 AT004112-02

NCI NIH HHS (2)

Grant ID: L30 CA110987

Grant ID: L30 CA110987-01