Abstract

Background

Cancer-related fatigue afflicts up to 33% of breast cancer survivors, yet there are no empirically validated treatments for this symptom.Methods

The authors conducted a 2-group randomized controlled trial to determine the feasibility and efficacy of an Iyengar yoga intervention for breast cancer survivors with persistent post-treatment fatigue. Participants were breast cancer survivors who had completed cancer treatments (other than endocrine therapy) at least 6 months before enrollment, reported significant cancer-related fatigue, and had no other medical conditions that would account for fatigue symptoms or interfere with yoga practice. Block randomization was used to assign participants to a 12-week, Iyengar-based yoga intervention or to 12 weeks of health education (control). The primary outcome was change in fatigue measured at baseline, immediately post-treatment, and 3 months after treatment completion. Additional outcomes included changes in vigor, depressive symptoms, sleep, perceived stress, and physical performance. Intent-to-treat analyses were conducted with all randomized participants using linear mixed models.Results

Thirty-one women were randomly assigned to yoga (n = 16) or health education (n = 15). Fatigue severity declined significantly from baseline to post-treatment and over a 3-month follow-up in the yoga group relative to controls (P = .032). In addition, the yoga group had significant increases in vigor relative to controls (P = .011). Both groups had positive changes in depressive symptoms and perceived stress (P < .05). No significant changes in sleep or physical performance were observed.Conclusions

A targeted yoga intervention led to significant improvements in fatigue and vigor among breast cancer survivors with persistent fatigue symptoms.Free full text

Yoga for persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial

Abstract

Background

Cancer-related fatigue afflicts up to one-third of breast cancer survivors, yet there are no empirically-validated treatments for this symptom.

Methods

We performed a two-group RCT to determine the feasibility and efficacy of an Iyengar yoga intervention for breast cancer survivors with persistent post-treatment fatigue. Participants were breast cancer patients who had completed cancer treatments (other than endocrine therapy) at least 6 months prior to enrollment, reported significant cancer-related fatigue, and had no other medical conditions that would account for fatigue symptoms or interfere with yoga practice. Block randomization was used to assign participants to a 12-week Iyengar-based yoga intervention or to 12 weeks of health education (control). The primary outcome was change in fatigue measured at baseline, immediately post-treatment, and 3 months after treatment completion. Additional outcomes included changes in vigor, depressive symptoms, sleep, perceived stress, and physical performance. Intent to treat analyses were conducted with all randomized participants using linear mixed models.

Results

Thirty-one women were randomly assigned to yoga (n = 16) or health education (n = 15). Fatigue severity declined significantly from baseline to post-treatment and over a 3 month follow-up in the yoga group relative to controls (P = .032). In addition, the yoga group showed significant increases in vigor relative to controls (P = .011). Both groups showed positive changes in depressive symptoms and perceived stress (P < .05). No significant changes in sleep or physical performance were observed.

Conclusions

A targeted yoga intervention led to significant improvements in fatigue and vigor among breast cancer survivors with persistent fatigue symptoms.

INTRODUCTION

Approximately one-third of cancer survivors experience persistent fatigue of unknown origin, causing significant impairment in quality of life (1;2). Despite the prevalence and impact of this symptom, there are currently no empirically validated treatments for persistent cancer-related fatigue. To date, only two published behavioral intervention trials have specifically targeted cancer survivors with persistent fatigue (3;4). Other psychological (e.g., stress reduction) and activity-based (e.g., exercise) interventions have reduced fatigue in cancer populations (5-7); however, because these trials have not targeted fatigued patients, the feasibility and efficacy of these approaches for treating post-cancer fatigue is unclear. Indeed, fatigue is a significant barrier to participation in exercise programs for cancer survivors (8).

Mind-body interventions such as yoga are a promising approach for treating cancer-related fatigue. Yoga involves physical postures (asanas) that develop strength and flexibility, and promote relaxation. Yoga is also a meditative practice because the practitioner focuses on the body and breath in each pose (9). A growing body of research indicates that yoga has beneficial effects on physical and behavioral outcomes in cancer patients and survivors (10-12), including improvements in quality of life, mood, and fatigue (13-18). However, as with the behavioral interventions, none of the published yoga trials have targeted patients with fatigue. Moreover, very few of these trials have included an active control group to control for attention, group support, and other non-specific components of the treatment.

The primary goal of this randomized controlled trial (RCT) was to examine the feasibility and efficacy of an Iyengar yoga intervention for breast cancer survivors with persistent post-treatment fatigue relative to health education control. Based on promising results from a small, uncontrolled trial conducted by our group (19), we hypothesized that this intervention would lead to significant improvements in fatigue and vigor. Effects on secondary outcomes, including depressive symptoms, sleep disturbance, stress, and physical performance, were also assessed.

METHODS

Design

The study was a single-center, two armed RCT. The UCLA Institutional Review Board approved the study procedures, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Participants

Breast cancer survivors with persistent post-treatment fatigue were recruited through multiple mechanisms, including tumor registry mailings, newspaper advertisements, and flyers distributed at cancer-related and community locations. Inclusion criteria were: 1) originally diagnosed with Stage 0 – II breast cancer; 2) completed local and/or adjuvant cancer therapy (with the exception of hormonal therapy) at least 6 months previously; 3) age 40 – 65; 4) post-menopausal; 5) no other cancer in last 5 years; and 6) experiencing persistent cancer-related fatigue. We focused on women with early-stage breast cancer to reduce heterogeneity in disease- and treatment-related factors impacting fatigue and its biological and psychological correlates. We focused on women at least 6 months post treatment completion to ensure that participants had persistent post-treatment fatigue and to reduce confounding residual effects of cancer treatment on biological parameters. The presence of cancer-related fatigue was indicated by scores of 50 or below on the SF-36 vitality scale, a reliable and valid measure of energy/fatigue in the past month (20), and self-report that fatigue was a consequence of cancer or cancer therapy. In our previous research, breast cancer survivors who scored at or below 50 on the SF-36 vitality scale showed behavioral, immune, and neuroendocrine alterations relative to women who scored above 50, supporting this classification (1;21-26).

Exclusion criteria were: 1) chronic medical conditions or regular use of medications that are associated with fatigue (e.g., untreated hypothyroidism, diabetes, autoimmune disease, anemia (defined as hematocrit < 24), chronic fatigue syndrome); 2) evidence that fatigue was primarily driven by a medical or psychiatric disorder other than cancer (e.g., current major depression, insomnia, sleep apnea); 3) evidence that fatigue was primarily driven by other non-cancer related factors (e.g., shift work, recent change in activity or schedule); 4) physical problems or conditions that could make yoga unsafe (e.g., serious neck injuries, unstable joints); and 5) body mass index greater than 31 kg/m2.

Potential participants were first screened by phone and then, if they met preliminary eligibility criteria, completed an in-person screening visit where they completed questionnaires and interviews about their medical history and were asked to perform simple movements (e.g., standing with feet touching for 30 seconds, lifting arms over head, moving from standing position to seated position on floor) to verify safety for yoga practice.

Randomization and blinding

Given class scheduling considerations, participants were randomized in blocks. Once a sufficient number of participants to comprise the yoga and health education groups had been screened as eligible (8-14 women), they were randomized (1:1) to the two treatments after completing baseline assessments. The allocation sequence was generated independently by the study statistician (RO) and concealed in opaque envelopes. Our recruitment documents, screening materials, and informed consent indicated that the purpose of this study was to compare two different treatments for post-cancer fatigue: yoga classes and a wellness seminar series. Thus, although participants were aware of the condition to which they were assigned, they did not know the study hypotheses. Outcomes assessors for the performance tasks were blinded to group assignment, and all were trained in standardized testing procedures.

Interventions

Iyengar yoga classes were conducted for 90 minutes twice a week for 12 weeks in groups of 4-6 women. Classes were taught by a certified Junior Intermediate Iyengar yoga instructor and an assistant under the guidance of a senior teacher. Iyengar yoga, a traditional form of Hatha yoga, prescribes specific therapeutic yoga practices for individuals with specific medical problems and conditions (27). This trial emphasized postures and breathing techniques believed to be effective for reducing fatigue among women with a history of breast cancer, with a focus on passive inversions (i.e., supported upside-down postures in which the head is lower than the heart) and passive backbends (i.e., supported spinal extensions). In supportive postures the shape of the pose is supported by props (e.g., blocks, bolsters, blankets, wall ropes, belts), rather than held by the strength of the body, so that participants can perform and maintain the postures without stress and tension. The postures were introduced using a standard progression from simpler to more challenging over the course of the intervention, and were adapted to suit individual needs. A complete list of study postures and the props used to support each is provided in Table 2. Of note, not all of these postures were included in each class. A typical sequence of postures included in a mid-intervention class and the duration of each posture is as follows: 1) Supta Baddhakonasana (10 minutes), 2) Setubandha Sarvangasana on bolsters (5 minutes); 3) Adhomukha Svanasana (5 minutes); 4) Salamba Sirsasana (5 minutes); 5) Viparita Dandasana (5 minutes); 6) Setubandha Sarvangasana on a wooden bench (5 minutes); 7) Viparita Karani (10 minutes); and 8) Supported Savasana (10 minutes).

Table 2

List of yoga postures for persistent cancer-related fatigue

| Sanskrit Name |

|---|

| Supta Baddhakonasana with bolster, strap, and blankets |

| Supta Svatstikasana with bolster and blanket |

| Setubandha Sarvangasana with bolster, strap and blankets |

| Setubandha Sarvangasana on a wooden bench with a box and bolster |

| Purvottanasana with two chairs, bolsters, and blankets |

| Viparita Dandasana on two chairs with the head supported |

| Salamba Sarvangasana with a chair, bolster, sticky mat, and blanket |

| Salamba Sirsasana on ropes |

| Supta Konasana with legs apart on two chairs |

| Viparita Karani with two blocks, a wall, a bolster and blankets |

| Bharadvajasana on chair |

| Adhomukha Svanasana on ropes with chair |

| Urdhva Mukha Svanasana with chair |

| Urdhva Hastasana |

| Urdhva Baddhanguliyasana |

| Ropes 1 |

| Savasana with bolster and blanket |

A full description of each pose, including pictures, and a detailed intervention manual including class sequences is available from the first author.

Health education classes were conducted for 120 minutes once a week for 12 weeks in groups of 4-7 women. Classes were led by a Ph.D. level psychologist with clinical experience in the treatment of breast cancer survivors. The classes were didactic in nature and consisted of lectures about topics of interest to breast cancer survivors followed by questions and discussion. The topics included 1) cancer-related fatigue, 2) introduction to cancer survivorship, 3) psychosocial issues in cancer survivorship, 4) weight and chronic disease management, 5) cancer genetic predisposition testing and counseling for breast/ovarian cancer syndromes, 6) stress and cancer, 7) diet, nutrition, and cancer survivorship, 8) sleep hygiene, 9) cognitive problems after cancer treatment, 10) osteoporosis and cancer survivorship, 11) body image and sexuality, 12) finding meaning and achieving goals. Our previous experience with this patient population suggested that women would be unlikely to travel to the study site twice a week for health education classes. Thus, we elected to have the health education group meet only once per week (vs. twice per week for yoga) for a longer duration (120 minutes/session vs. 90 minutes/session for yoga). As a result, the total number of class hours for yoga (36 hours) was higher than for health education (24 hours). Neither group was instructed to do home practice or reading.

Outcome Measures

Questionnaires and functional assessments were obtained at baseline, immediately post-intervention, and 3 months after the intervention was completed. The primary outcome of interest was subjective fatigue severity, assessed with the Fatigue Symptom Inventory (FSI), a reliable and valid measure of fatigue that was designed for use with cancer patients (28;29). A related outcome, vigor, was assessed using the vigor subscale of the Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory (30). Several secondary outcomes were also assessed. To determine whether intervention effects might extend to behavioral symptoms correlated with fatigue (1;31), we assessed depressive symptoms using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) (32) and subjective sleep quality using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (33). In addition, to examine more generalized intervention effects on feelings of stress, we administered the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)(34). Physical performance tasks were administered to provide an objective measure of functional status. Timed chair stands were used to assess lower extremity strength and endurance (35), and the functional reach test was used to assess strength, flexibility and balance (36).

Self-reported demographic and disease-related variables were assessed at baseline, and expectations and beliefs about treatment efficacy were assessed at baseline and post-intervention. Self-efficacy for managing fatigue, a potentially important component of intervention effects (37), was assessed with the fatigue subscale of the HIV self-efficacy questionnaire (38) adapted for breast cancer. Fatigue interference with activities, mood, and enjoyment of life was assessed with the interference subscale of the FSI (28;29). Finally, blood and saliva samples were collected for assessment of biological functioning; results from these assays are still pending and will be reported separately.

Statistical analyses

Based on the large effect on subjective fatigue severity observed in our single arm pilot study of this yoga intervention (d = 2.2 at post-intervention, 1.2 at 3 month follow-up) (19), a sample of 30 participants would provide 90% or greater power to detect a between-group difference on the FSI. To account for the possibility of a smaller intervention effect than that observed in our single-arm pilot, our original enrollment target was 72 participants and assumed 20% loss to follow-up. Because of our stringent eligibility criteria, enrollment was lower than planned (n = 31) but still adequate to detect a large intervention effect. All statistical analyses were performed on an intent-to-treat basis. Outcome measures were first tested for baseline equivalence using t-tests or chi-squared as appropriate. Primary analyses utilized mixed model ANOVAs to account for any incomplete data (i.e., lost to follow-up). Treatment (yoga, health education) by Time (baseline, post-treatment, 3 month post-treatment follow-up) were the independent factors, with the time factor covariances estimated individually (i.e., unstructured). Separate analyses were conducted for each of the outcome measures. We did not adjust for multiple testing. Exact p values are presented.

RESULTS

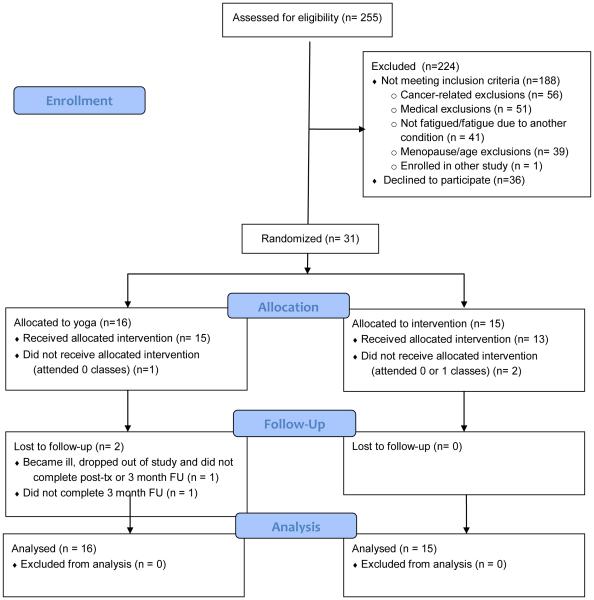

The study took place at the UCLA Medical Center, Westwood, CA between March 2007 and July 2010. We screened 255 women for eligibility; 188 (75%) were not eligible, and 36 (14%) were not interested in participating. The primary reasons for ineligibility were cancer-related, including diagnosis with Stage 3 or 4 breast cancer (n = 23), no previous breast cancer diagnosis (n = 19), less than 6 months post treatment completion (n = 11), and other cancer in last 5 years (n = 3). Medical exclusions were BMI greater than 31 (n=23), medical conditions that might interfere with safe yoga practice (n = 17), chronic medical conditions or medications that might impact fatigue (n = 11), and age and menopause-related (n = 39). Fatigue-related exclusions were not fatigued (n = 30) and fatigue not related to cancer (n = 11). We randomized 31 women to either a 12-week Iyengar yoga intervention (n = 16) or a 12-week health education program (n = 15). Twenty-eight women received the allocated intervention, which we defined as attending more than one class, and follow-up data was obtained on 29 participants (94%). A CONSORT flow diagram is provided in Figure 1.

Groups were balanced on demographic and disease-related characteristics at baseline, and both reported high levels of fatigue (Table 1). In the yoga group, the mean number of classes attended was 18.9 (78%) and the median was 22 (92%), out of a total of 24 classes. In the education group, the mean number of classes attended was 9.2 (77%) and the median was 11 (92%), out of a total of 12 classes. At the 3 month follow-up, 9 of the 14 women who attended the yoga classes (64%) were continuing to use techniques learned in class.

Table 1

Demographic and treatment-related characteristics of study participants

| Characteristic | Yoga (n = 16) | Health education (n = 15) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 54.4 (5.7) | 53.3 (4.9) |

| Race/ethnicity, # (%): | ||

| White | 15 (94) | 12 (80) |

| Hispanic | 0 | 2 (13) |

| Black | 1 (6) | 0 |

| Other | 0 | 1 (7) |

| Relationship status, # (%): | ||

| Married/committed relationship | 12 (75) | 11 (73) |

| Education status, # (%): | ||

| High school graduate/AA degree | 6 (37.5) | 7 (46) |

| College graduate | 6 (37.5) | 4 (27) |

| Graduate degree | 4 (25) | 4 (27) |

| Annual family income, # (%): | ||

| < 45,000 | 3 (19) | 1 (7) |

| 45,000 – 75,000 | 5 (31) | 4 (27) |

| 75,000 – 100,000 | 4 (25) | 3 (20) |

| > 100,000 | 3 (19) | 7 (46) |

| Not reported | 1 (6) | 0 |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) | 24.0 (2.5) | 25.3 (3.4) |

| Treated with radiation, # (%) | 11 (69) | 13 (87) |

| Treated with chemotherapy, # (%) | 8 (50) | 9 (60) |

| Tamoxifen/aromatase inhibitor, # (%) | 12 (75) | 10 (67) |

| Years since treatment completion, median (range) | 1.7 (0.7 – 4.1) | 1.7 (0.7 – 18.3) |

| SF-36 vitality score, mean (SD) | 37.8 (16) | 34.0 (16.3) |

No differences are significant at p < .20

Intervention effects on fatigue and vigor

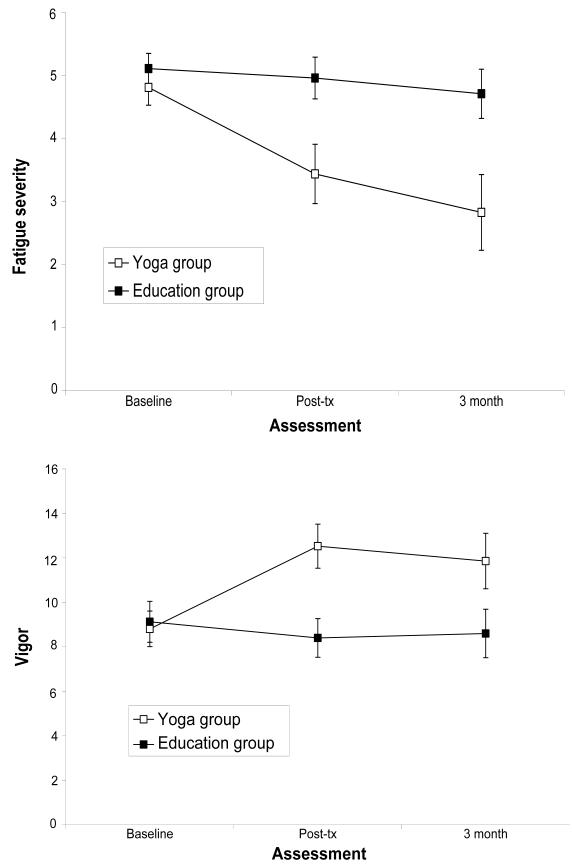

Yoga led to statistically significant improvements in fatigue severity (P for group x time interaction = .032; effect size for predicted change from baseline to 3 month follow-up in yoga vs. health education: d = 1.5). Participants in the yoga group reported steady declines in fatigue severity from baseline to post-treatment and over the 3 month follow-up, whereas women assigned to health education reported no change over this period (Figure 2). Similar effects were observed for vigor, with the yoga group showing a statistically significant increase over the assessment period compared to controls (P for group x time interaction = .011; effect size for predicted change from baseline to 3 month follow-up in yoga vs. health education: d = 1.20). We also explored intervention effects on fatigue interference, and found a significant effect of time (P < .0001) and a marginally significant group x time interaction (P = .08). Both groups reported decreases in fatigue interference over time, with a marginally larger decrease in the yoga group (mean change from baseline to 3 month follow-up = 15.8) than in health education (mean change from baseline to 3 month follow-up = 7.9). Yoga group participants also felt significantly more confident about their ability to manage fatigue and its impact on their lives than control group participants at post-treatment (yoga group mean = 7.9, education group mean = 6.1; t (28) = −2.6, P = .017).

Change in fatigue severity (Panel A) and vigor (Panel B) in yoga and health education groups. The yoga group showed significant declines in fatigue severity and significant improvements in vigor from baseline to post-treatment and over the 3-month post-treatment follow-up relative to health education controls.

To determine the clinical significance of these effects, we calculated the change in SF-36 vitality scale scores from baseline to 3 month follow-up in each group. Although this was not a primary outcome for the trial, there are published norms for determination of clinically significant change on this measure (39). For women randomized to yoga, there was a mean increase in SF-36 vitality scores of 23.9 points, which exceeds the reliable change index of 22.7 for this scale and indicates a clinically significant improvement in fatigue. For women randomized to health education, the mean increase in SF-36 vitality scores was 7.7 points.

Intervention effects on depressive symptoms, stress, sleep, and physical performance

For depressive symptoms, there was a significant effect of time (P < .0001) and a significant group x time interaction (P = .026). Both groups reported reductions in depressive symptoms from baseline to post-treatment, although there was a greater decline in symptoms among women in the yoga group at this time point. By the 3 month follow-up, the yoga group had rebounded and the groups reported similar symptom levels. There was also a significant time effect for perceived stress (P = .015); feelings of stress decreased over the assessment period in both groups. There were no significant effects for subjective sleep quality. For the physical performance tasks, there was a significant time effect for chair stands (P < .0001) as both groups improved over time, but no group x time interaction for either task (Ps > .60). Table 3 presents mean scores for the primary and secondary outcomes at baseline, post-treatment, and 3 month follow-up as well as group differences in change scores.

Table 3

Mean Scores on Outcome Measures for Yoga and Health Education Groups

| Outcome | Baseline Mean (SD) | Post-treatment Mean (SD) | 3 month FU Mean (SD) | Group Difference in Change from Baseline- Post treatment Mean (95%CI) | Group Difference in Change from Baseline-3 month FU Mean (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Primary Outcomes

| |||||

| FSI fatigue severity (0-11; higher is worse) | |||||

Iyengar Yoga Iyengar Yoga | 4.8 (1.1) | 3.4 (1.8) | 2.8 (2.3) | −1.24 (−0.04 to −2.45)* | −1.62 (−0.37 to −2.88)* |

Health Education Health Education | 5.1 (.95) | 4.9 (1.3) | 4.7 (1.5) | ||

| MFSI vigor (0-24; higher is better) | |||||

Iyengar Yoga Iyengar Yoga | 8.8 (3.2) | 12.5 (3.8) | 11.9 (4.7) | 4.80 (1.86 to 7.74)* | 4.25 (0.99 to 7.50)* |

Health Education Health Education | 9.1 (3.6) | 8.4 (3.4) | 8.6 (4.2) | ||

|

| |||||

|

Secondary Outcomes

| |||||

| BDI-II depressive symptoms (0-63; higher is worse) | |||||

Iyengar yoga Iyengar yoga | 15.5 (7.5) | 7.7 (5.8) | 9.9 (8.0) | −5.80 (−1.74 to −9.86)* | −3.06 (0.37 to −6.49) |

Health education Health education | 14.3 (7.5) | 11.6 (7.1) | 10.5 (7.9) | ||

| PSQI sleep disturbance (0-21; higher is worse) | |||||

Iyengar yoga Iyengar yoga | 9.2 (3.3) | 8.1 (2.5) | 7.6 (2.7) | 0.20 (2.78 to −2.38) | −2.14 (1.06 to −5.39) |

Health education Health education | 9.1 (3.5) | 7.7 (2.6) | 9.1 (3.3) | ||

| Perceived stress scale (0-40; higher is worse) | |||||

Iyengar yoga Iyengar yoga | 26.6 (7.3) | 23.5 (7.3) | 23.6 (6.7) | −1.77 (1.71 to −5.26) | −1.51 (2.38 to −5.39) |

Health education Health education | 26.8 (5.9) | 25.4 (5.9) | 24.2 (4.7) | ||

| Chair stand time, sec (higher is worse) | |||||

Iyengar yoga Iyengar yoga | 13.4 (2.3) | 12.3 (2.0) | 11.1 (1.9) | 1.31 (−5.00 to 2.38) | −0.74 (−3.74 to 2.26) |

Health education Health education | 13.5 (2.6) | 12.6 (3.2) | 12.2 (2.8) | ||

| Functional reach, cm (higher is better) | |||||

Iyengar yoga Iyengar yoga | 31.1 (5.7) | 29.6 (6.2) | 29.5 (5.1) | −2.00 (5.76 to −9.73) | −2.21 (5.56 to −9.98) |

Health education Health education | 29.5 (6.7) | 28.5 (7.2) | 28.8 (8.0) | ||

Expectations and beliefs about treatment

We assessed expectations and beliefs about treatment efficacy to determine whether these might account for beneficial effects of yoga. After random assignment, participants in both groups believed that the intervention to which they had been assigned would be effective in improving their fatigue symptoms; on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 0 “not at all effective” to 6 “very effective”, the mean score for the yoga group was 3.86 and for the health education group was 3.2 (P = .33). At post-treatment, participants in both groups reported that they had experienced “quite a bit” of benefit from attending the classes (mean score for the yoga group was 4.43 and for the health education group was 4.87 on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 0 “no benefit” to 6 “very much benefit”; P = .53). Moreover, both groups reported positive changes in fatigue at post-intervention; on a 13-point Likert scale ranging from −6 “very much worse” to 6 “very much better”, the mean score for the yoga group was 1.93 and for the education group was 1.87 (P = .94). These findings suggest that the two groups had similar expectations and beliefs about treatment efficacy.

Safety

There was one adverse event related to the protocol; a participant with a history of back problems experienced a back spasm in yoga class. After evaluation by her physician, she was able to return to class and complete the intervention.

DISCUSSION

Results from this randomized, controlled trial indicate that a yoga intervention targeted at improving fatigue may be a feasible and effective treatment for breast cancer survivors with persistent cancer-related fatigue. Participants in the yoga group experienced significant reductions in fatigue and increases in vigor from pre to post-treatment that persisted over a three month follow-up, consistent with results from our single arm pilot study (19), whereas control group participants showed no change in these outcomes. Measures of effect size indicated that this was a large effect (d = 1.5 for fatigue severity), considerably larger than the small to moderate effect sizes observed in previous behavioral interventions for cancer-related fatigue (5;7). This change also appeared to be clinically significant. By the three month post-treatment follow up, scores on the Fatigue Symptom Inventory fell below the cutoff for clinically meaningful fatigue among women in the yoga group (40), and this group also showed a clinically significant increase on the SF-36 vitality scale (39).

Despite high levels of fatigue at study onset, adherence to the yoga intervention was excellent, with over 80% of participants attending at least 20 of the 24 yoga classes offered. This is notable because fatigue is typically a barrier to participation in behavioral interventions for cancer patients, including yoga programs not specifically designed to treat fatigue (18). We suspect that the careful selection of yoga poses for fatigued individuals and the use of props that enabled these poses to be performed without effort or strain played an important role in maintaining trial adherence.

Participants in the yoga and the health education interventions reported comparable declines in depressive symptoms and perceived stress by the three month follow-up. For the education group, these improvements may have resulted from the provision of information about breast cancer survivorship as well as non-specific aspects of the intervention, including attention and group support. Very few behavioral or mind-body intervention trials for cancer-related fatigue have included active control groups, relying instead on usual care or wait-list controls (5-7). Consistent with our findings, Irwin et al. found beneficial effects of health education on depressive symptoms in a study comparing Tai Chi to health education for insomnia (41). These results strongly support the inclusion of active control groups in mind-body and other behavioral intervention trials.

Our study had several limitations. First, we enrolled a relatively small number of participants, reflecting the challenges of recruiting fatigued breast cancer survivors with no co-morbid fatigue-related medical conditions or physical limitations who were willing to participate in a demanding intervention study. It will be important to replicate these findings in a larger trial, and to determine if effects are generalizable to a broader group of breast cancer survivors. We also restricted our sample to women who had been diagnosed with early stage disease, had completed cancer treatment, and had a BMI under 31. Thus, effects may not be generalizable to breast cancer survivors with more advanced disease, who are undergoing treatment, and/or who are obese, and the yoga intervention may require adaptation to meet the specific needs of these groups. In addition, although the majority of study participants (94%) were within 5 years post-diagnosis, we did enroll a few women who had been living with cancer-related fatigue for over 10 years. Future studies should examine whether the length of time since cancer treatment influences intervention efficacy, and possibly target either shorter-term or longer-term survivors. Next, it is not feasible to use a double-blind study design with this type of intervention; participants are unavoidably aware of the treatment that they receive. We attempted to minimize the impact of pre-existing beliefs and expectations on study outcomes by informing participants that we were testing two different treatments for cancer-related fatigue, each of which were presumably effective. This presentation appeared to have been successful, as both groups had similar positive expectations about the efficacy of the treatment to which they had been assigned. Finally, the yoga and health education conditions were not matched for class frequency or duration, and it is possible that benefits seen in the yoga group may be attributable in part to the higher number of intervention hours received. Future studies should match class frequency and duration across conditions. It will also be useful to compare yoga to a more physically-oriented control condition (e.g., stretching) or to relaxation, to probe the active components of this intervention.

These preliminary findings indicate that a specialized yoga intervention may have beneficial effects on cancer-related fatigue, even among survivors who have experienced fatigue for years post-treatment. Future investigation into this promising approach is warranted, including examination of mechanisms and duration of treatment effects. Yoga may have effects on the immune and neuroendocrine systems (42-46), which have been linked to post-treatment fatigue in previous research (21;23;24;26;47-49) and are currently under investigation in this sample.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NCCAM/NIH U01- AT003682 Iyengar Yoga for Breast Cancer Survivors with Persistent Fatigue. The authors report no financial disclosures

Reference List

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.26702

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc3601551?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1002/cncr.26702

Article citations

Optimal exercise dose and type for improving sleep quality: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of RCTs.

Front Psychol, 15:1466277, 03 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39421847 | PMCID: PMC11484100

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Yoga as Potential Therapy for Burnout: Health Technology Assessment Report on Efficacy, Safety, Economic, Social, Ethical, Legal and Organizational Aspects.

Curr Psychiatry Rep, 13 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39266899

Review

Effects of a tailor-made yoga program on upper limb function and sleep quality in women with breast cancer: A pilot randomized controlled trial.

Heliyon, 10(16):e35883, 09 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39253212 | PMCID: PMC11382167

The effectiveness of mind-body therapy and physical training in alleviating depressive symptoms in adult cancer patients: a meta-analysis.

J Cancer Res Clin Oncol, 150(6):289, 05 Jun 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38836958 | PMCID: PMC11153279

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Integrating Yoga into Comprehensive Cancer Care: Starting Somewhere.

Eur J Integr Med, 67:102348, 21 Feb 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39372426

Go to all (157) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Yoga reduces inflammatory signaling in fatigued breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial.

Psychoneuroendocrinology, 43:20-29, 30 Jan 2014

Cited by: 146 articles | PMID: 24703167 | PMCID: PMC4060606

Randomized pilot trial of yoga versus strengthening exercises in breast cancer survivors with cancer-related fatigue.

Support Care Cancer, 24(9):4005-4015, 29 Apr 2016

Cited by: 32 articles | PMID: 27129840

Mindful Yoga for women with metastatic breast cancer: design of a randomized controlled trial.

BMC Complement Altern Med, 17(1):153, 13 Mar 2017

Cited by: 12 articles | PMID: 28288595 | PMCID: PMC5348886

Effects of yoga interventions on fatigue in cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials.

Explore (NY), 9(4):232-243, 01 Jul 2013

Cited by: 39 articles | PMID: 23906102 | PMCID: PMC3781173

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NCATS NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: UL1 TR000124

NCCIH NIH HHS (3)

Grant ID: U01 AT003682-01

Grant ID: U01-AT003682

Grant ID: U01 AT003682