Abstract

Free full text

Germline BAP1 Mutations Predispose to Renal Cell Carcinomas

Abstract

The genetic cause of some familial nonsyndromic renal cell carcinomas (RCC) defined by at least two affected first-degree relatives is unknown. By combining whole-exome sequencing and tumor profiling in a family prone to cases of RCC, we identified a germline BAP1 mutation c.277A>G (p.Thr93Ala) as the probable genetic basis of RCC predisposition. This mutation segregated with all four RCC-affected relatives. Furthermore, BAP1 was found to be inactivated in RCC-affected individuals from this family. No BAP1 mutations were identified in 32 familial cases presenting with only RCC. We then screened for germline BAP1 deleterious mutations in familial aggregations of cancers within the spectrum of the recently described BAP1-associated tumor predisposition syndrome, including uveal melanoma, malignant pleural mesothelioma, and cutaneous melanoma. Among the 11 families that included individuals identified as carrying germline deleterious BAP1 mutations, 6 families presented with 9 RCC-affected individuals, demonstrating a significantly increased risk for RCC. This strongly argues that RCC belongs to the BAP1 syndrome and that BAP1 is a RCC-predisposition gene.

Main Text

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC [MIM 144700]) represents ~2% of all malignant diseases in adults.1 Although most cases are sporadic, approximately 2% to 4% of RCC cases are hereditary. The majority of familial RCC is linked to monoallelic VHL (MIM 608537) mutations and is associated with the von Hippel Lindau syndrome (VHL [MIM 193300]). Other cases are linked to FLCN (MIM 607273) mutations defining the Birt-Hogg-Dubé (BHD [MIM 135150]) syndrome, to monoallelic MET (MIM 164860), FH (MIM 136850), SDHB (MIM 185470), or CDC73 (MIM 607393) mutations, or to chromosome 3 translocations.2,3 However, the hereditary origin of some familial nonsyndromic RCC cases, defined by at least two affected first-degree relatives, remains unknown. The best genetic model to date is an autosomal-dominant inheritance according to a large European segregation study, which gathered 60 families with members who tested negative for VHL germline mutations.4 By combining whole-exome sequencing, genotyping, and tumor profiling in a family with RCC-prone individuals, we identified a BAP1 (MIM 603089) mutation as the genetic basis for RCC predisposition. Predisposition to RCC was further confirmed in independent families with members who carried deleterious BAP1 mutations.

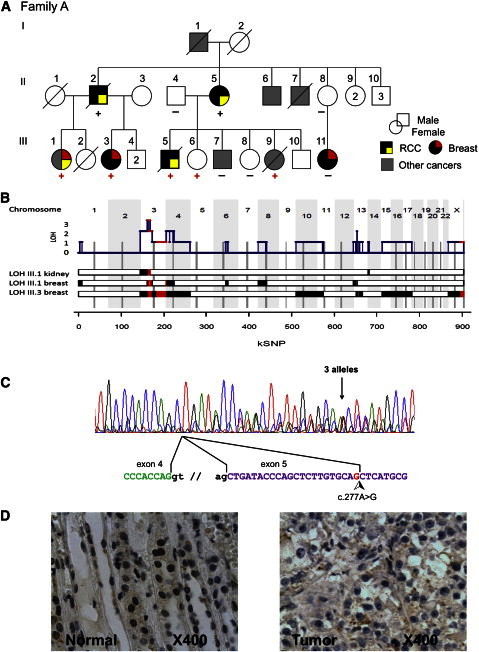

Aiming at identifying new genetic factors of familial RCC, we characterized a two-generation family with a high incidence of RCC. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and proper informed consents were obtained. Family A included individuals with multiple cancer types, including four first-degree relatives over two generations with RCC (Figure 1A). This number of RCCs within a non-VHL family is uncommon and indicates a genetic predisposition. As a comparison, only 3 out of the 60 non-VHL RCC-affected families reported by Woodward et al. had as many affected individuals.4 The index case of family A (III-1) developed multiple and bilateral clear cell RCCs (ccRCC) at 37, 39, and 47 years of age as well as two independent breast cancers at early onset. She was tested negative for germline VHL and FLCN mutations, chromosome 3 translocations, and BRCA1 (MIM 113705), BRCA2 (MIM 600185), and TP53 (MIM 191170) alterations. Her father (II-2), cousin (III-5), and aunt (II-5) developed RCC, and for two of them at early onset (40 and 47 years of age for III-5 and II-2, respectively). Other tumor types were reported in this family: breast carcinomas at early onset in three female individuals (III-1, III-3, and III-11), including the previously mentioned bilateral breast carcinoma for the index case; a pericardial metastatic adenocarcinoma of unknown primary origin (III-9); and a lung carcinoma (III-7) (Figure 1A).

Clinical and Biological Characterization of Family A

(A) Pedigree and tumor spectrum of family A. Proven BAP1 mutation carriers are indicated with a red plus sign, obligate mutation carriers with a black plus sign, and proven wild-type individuals with a black minus sign. Abbreviations are as follows: RCC, renal cell carcinoma; Breast, breast carcinoma. Other cancers: I-1, esophagus carcinoma; II-6, head and neck carcinoma; II-7, esophagus carcinoma; III-1, cervix carcinoma; III-7, lung carcinoma; III-9, adenocarcinoma of unknown primitive tumor (ACUP).

(B) Whole-genome tumor analysis by SNP array identified 3p21-containing BAP1 gene as the unique region of consistent loss of heterozygosity (LOH) and identical by descent (IBD) haplotype. The three lower tracks correspond to the three tumors analyzed in Affymetrix SNP6.0, using the number of consecutive probesets as coordinates. LOH is indicated by red boxes (IBD haplotype retained in the tumor) and black boxes (unshared haplotype retained in the tumor). Cumulative LOH is shown on the upper track with the location of BAP1. IBD is defined between III-1, III-3, and III-5 affected individuals.

(C) BAP1 transcript detected in index case III-1. Three sequences are visible on the electropherogram: the wild-type cDNA, the cDNA with the missense c.277A>G mutation, and the abnormally spliced cDNA as a consequence of the new acceptor splicing site within exon 5. The alternative splicing is illustrated below the electropherogram. The cDNA sequence was amplified from a lymphoblastoid cell line derived from patient III-1.

(D) Immunohistochemistry from a renal cell carcinoma affecting index case III-1. The left panel shows adjacent normal renal tissue of the tumor sample. The brown staining illustrates a significant normal nuclear immune-labeling of BAP1 protein. The right panel shows a subset of tumor cells with a blue counterstaining indicating a lack of BAP1 expression in tumors.

Whole-exome sequencing of germline DNA was performed for III-1 and her first-degree cousin (III-5), both affected with RCC. After liquid capture enrichment of coding sequences (SureSelect kit V1, Agilent) and sequencing performed on the SOLiD platform (v.4), approximately 100 million uniquely mapped reads were obtained for each case (alignment performed on Bioscope Aligner, UCSC genome version hg19, February 2009, Genome Reference Consortium GRCh37). SAMtools pileup was utilized to enumerate variations.5 Approximately 90% of exons were covered at least 1×, and the median coverage was 60×. Detected variation was annotated with ANNOVAR with the SeattleSeq Annotation tool.6 Seven unknown (absent in dbSNP v.137) nonsynonymous single-nucleotide variations (SNVs) at the heterozygous state, and shared between the two individuals, were detected. A summary of the sequencing results is presented in Tables S1 and S2 (available online). Five SNVs were predicted by the PolyPhen method to have high deleterious impacts on their corresponding protein function.7 Three of these were validated by Sanger sequencing (Table 1). A single deletion, leading to a frameshift, was also detected but was not considered as a possible candidate (Table S3).

Table 1

SNVs with Predicted Damaging Effect on the Protein Function

| Gene | Chr | Positiona | Accession NCBI | Ref/Alt | Alt Transcript | Alt Protein | LOH in RCC | IBD | Coverage | Alt Freq |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAP1 | 3 | 52442072 | NM_004656.2 | T/C | c.A277G | p.Thr93Ala | 1 | 1 | 39 | 0.21 |

| KALRNb | 3 | 124397063 | NM_001024660.3, NM_007064.3 | G/A | c.G7220A | p.Arg2407His | 0 | 1 | 35 | 0.4 |

| ERCC5b | 13 | 103519045 | NM_000123.3 | G/A | c.G2383A | p.Ala795Thr | 0 | 1 | 48 | 0.48 |

Mutation nomenclature follows the recommended guidelines of the Human Genome Variation Society with the nucleotide numbering based on GenBank reference sequence indicated by its accession NCBI number. Nucleotide numbering denotes the adenosine of the annotated translation start codon as nucleotide position +1. Only Sanger-validated SNVs are indicated in this table. Abbreviations and definitions are as follows: Alt freq, ratio of alternative/total reads; Alt protein, alternative protein; Alt transcript, alternative transcript; Chr, chromosome; Coverage, number of independent reads; IBD, identical by descent region; LOH in RCC, loss of heterozygosity in renal cell carcinoma of individual III-1 from family A; Ref/Alt, reference and alternative alleles; SNVs, single-nucleotide variants.

To further evaluate these variants as candidate predisposition genes, the genomic profiles of tumors from family A were analyzed by SNP arrays (Affymetrix SNP6.0). If the predisposition gene responsible for RCC in this family follows the Knudson’s two-hit model for tumor suppressor genes, one can assume that (1) one allele is inactivated by a germline deleterious mutation, (2) this mutated allele is retained in the tumor, and (3) the other allele is inactivated somatically, classically by deletion. The available RCC sample from the index case showed loss of heterozygosity (LOH) for the 3pter–14.1 chromosomal region (genomic position 0–64 Mb) as the unique acquired large genomic alteration in this tumor (Figure 1B).

Germline SNP-array genotyping of ten members from the family A was also performed. The list of identical by descent (IBD) regions for the two cousins (III-1 and III-5) included 3p21.31–13 (genomic positions 46–72 Mb), and this was confirmed by whole-exome sequencing (Table S4). The shared haplotype in the 3p chromosomal region retained in the tumor narrowed the candidate region to 3p21.31–14.1 (46–64 Mb) (Figures 1B and S1).

Because the dbSNP v.137 database contains some SNPs with pathologic consequences, we detected six variants with predicted high impact on protein function, reported in dbSNP v.137 with low or unknown minor allele frequencies (MAF), and common between III-1 and III-5. These variants were not further considered because none were in a LOH region in the RCC from the III-1 index case (Table S5).

We then evaluated the three validated unknown SNVs with potential deleterious effects. All three SNVs segregated with RCC-affected relatives, but only the g.52442072T>C substitution in BAP1 (BRCA1 Associated Protein 1) was located in the 3p LOH region. This BAP1 SNV was confirmed by Sanger sequencing in all RCC-affected relatives with available DNA (Figures 1A and S2). Because the 3p21 haplotype encompassing the BAP1 mutation was shared by the two cousins, the father (II-2) and aunt (II-5) of the index case were obligate mutation carriers, indicating a complete cosegregation of the BAP1 mutation with RCC in this family.

BAP1 encodes a nuclear ubiquitin carboxyterminal hydrolase (UCH), which was initially described as binding to the BRCA1 RING finger and enhancing BRCA1-mediated cell growth suppression.8 BAP1 interacts with ASXL1 (MIM 612990) to form the Polycomb group Repressive Deubiquitinase complex (PR-DUB). This complex deubiquitinates H2A and participates in HOX repression by chromatin modification.9 BAP1 also contains a UCH37-like domain (ULD), which is the binding site for the transcriptional factor HCFC1 (MIM 300019). The HCFC1/BAP1 complex contributes to cell cycle progression and BAP1 deubiquitinating activity is probably involved in HCFC1 turnover.10 BAP1 was found to be frequently somatically inactivated in uveal melanoma and mesothelioma, and germline mutations predispose to these tumors.11–14 More recently, BAP1 was found somatically inactivated in 8% to 14% of ccRCCs.15,16 Deleterious mutations found in BAP1 in various pathological cases are mainly leading to truncated BAP1 proteins, by nonsense mutations, frameshifts, or splicing defects.17

The BAP1 mutation detected in family A created a new splicing acceptor site within exon 5, with functional consequences demonstrated by transcript analyses from a lymphoblastoid cell line derived from the index case. Two transcripts resulting from this mutation were detected: c.256_277del (p.Ile87MetfsX4) and c.277A>G (p.Thr93Ala) (Figure 1C). Quantitative cDNA characterization and ExonTrap approach (MoBiTec; Figure S3) indicated that 80% of BAP1 transcripts corresponded to the aberrantly spliced transcripts leading to a frameshift, whereas less than 20% corresponded to the missense mutation. Furthermore, the location of this missense mutation close to the active site of the UCH domain, and the amino acid phylogenetic conservation, strongly suggest that the p.Thr93Ala amino acid substitution impairs BAP1 deubiquitinating activity.18 Finally, BAP1 was undetected by immunohistochemistry (IHC, sc-28383 antibody from Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in three available RCCs from this family, two from III-1 and one from II-2 (Figure 1D). The monoallelic BAP1 germline deleterious mutation and the absence of detectable BAP1 in renal tumors in family A, together with the demonstrated role of BAP1 in nonhereditary RCC malignancy,15,16 strongly argue that the BAP1 mutation is the genetic basis of renal cancer predisposition in this family.

To further evaluate the contribution of germline BAP1 mutations in RCC susceptibility, two series of individuals were screened. The first series included 32 unrelated French RCC individuals with at least one first- or second-degree relative affected with RCC and who tested negative for RCC-predisposing genes (Table S6). Half of this series was previously published for the French cases.4 Screening was performed by the sensitive heteroduplex detection method EMMA, which allows the detection of both small size mutations and large gene rearrangements.19 The EMMA amplicons, having an abnormal profile, were Sanger sequenced (Table S7). No BAP1 mutation was detected in this series, suggesting that germline BAP1 mutations rarely explain families affected only with RCC.

Following the already described spectrum of diseases associated with BAP1 mutations (MIM 614327), an additional series of familial cases was considered in order to evaluate the occurrence of RCC in families with members carrying BAP1 mutations. A cohort of 60 European index cases, with familial features suggesting a high risk of BAP1 mutation as a genetic basis of cancer, was assembled from three reference cancer centers in the Paris area. All included familial cases affected either with uveal melanoma (UM), cutaneous melanoma (CM), or mesothelioma (MPM) that had at least one first- or second-degree relative affected with one of these malignancies (Figure 2A; Table S8). It should be noted that families with only CM were not included and that RCC was not a selection criteria for screening these families. Germline deleterious BAP1 mutations were identified in 11 out the 60 families (18%), especially in all families presenting both UM and MPM (5 out of 5), whereas families with only UM or with both UM and CM were rarely mutated (1/8 and 3/42, respectively) (Table 2, Figures 2A and 2B). All identified mutations led to a premature stop codon (nonsense, frameshift, or splicing mutations). Clinical records for these 11 families comprised 83 individuals (38 females, 45 males, 2 unknown; Table S9) with 2 to 14 relatives available per family in 1 to 3 generations (average age 54.0 [18–90], 1 with unknown age). A total of 33 individuals were diagnosed with UM, MPM, or CM in diverse associations; 14 individuals had other cancers, including renal, lung, breast, prostatic, thyroid, and bladder carcinomas.

Pedigree of the Families with Members Carrying BAP1 Mutations

(A) Venn diagram of familial tumor spectrum of the 60 families screened for BAP1 germline mutation. Numbers in black represent number of families with members carrying a given tumor association, and numbers in red represent number of these families with members carrying BAP1 mutation.

(B) Pedigrees of families with members carrying a germline BAP1 mutation. Arrows indicate index cases. Proven BAP1 mutation carriers are indicated with a red plus sign, obligate mutation carriers indicated with a black plus sign, and proven wild-type individuals indicated with a black minus sign.

Abbreviations are as follows: CM, cutaneous melanoma; MPM, malignant pleural mesothelioma; UM, uveal melanoma.

Table 2

Families with Members Carrying BAP1 Mutations

| ID | Cancers and Age at Onset in Years | BAP1 Mutation | Predicted Effect | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UM | MPM | CM | RCC | |||

| Family B | II-1 (35) | II-1 (36) | c.629dupT (p.Met211HisfsX32) | truncating | ||

| II-3 (NA) | II-2 (54) | |||||

| I-3 (NA) | I-1 (57) | |||||

| Family C | II-5 (52) | II-5 (59) | I-2 (50) | c.1654delG (p.Asp552IlefsX19) | truncating | |

| II-6 (53) | I-5 (54) | |||||

| II-4 (41) | ||||||

| Family D | III-2 (48) | III-2 (34) | I-1 (55) | c.437+1G>A (p.?) | truncating | |

| II-1 (70) | ||||||

| III-7 (50) | ||||||

| Family E | III-1 (44) | II-1 (60) | c.219delT (p.Asp73GlufsX5) | truncating | ||

| I-1 (60) | ||||||

| Family F | II-1 (41) | c.670dupC (p.His224ProfsX19) | truncating | |||

| I-1 (64) | ||||||

| Family G | II-4 (57) | I-1 (59) | II-1 (49) | II-3 (36) | c.37+1delG (p.?) | splicinga |

| II-3 (29,31,34) | ||||||

| Family H | I-3 (62) | c.1647delT (p.Val550SerfsX21) | truncating | |||

| I-1 (59) | ||||||

| Family I | II-1 (44) | I-1 (66) | c.1846delG (p.Val616X) | truncating | ||

| Family J | I-1 (53) | I-4 (NA) | I-2 (45) | I-2 (53) | c.78_79delGG (p.Val27AlafsX41) | truncating |

| I-3 (33) | ||||||

| Family K | II-4 (42) | II-2 (38) | I-1 (58) | II-3 (34) | c.660−11T>A (p.?) | splicing |

| II-1 (47,52) | ||||||

| II-6 (42) | ||||||

| Family L | I-1 (71) | II-1 (47) | c.588G>A (p.Trp196X) | splicing | ||

Mutation nomenclature follows the recommended guidelines of the Human Genome Variation Society with the nucleotide numbering based on GenBank reference sequence NM_004656.2. Nucleotide numbering denotes the adenosine of the annotated translation start codon as nucleotide position +1.

Interestingly, 9 RCCs were reported in 6 of the 11 families with members carrying BAP1 mutations. Four of these six RCC-affected families were presenting with both UM and MPM. Furthermore, RCC was associated with a BAP1-mutated status in four cases for which the status was available (all individuals from independent families). RCC-affected individuals could not be tested in two other families with members carrying BAP1 mutations with RCC. Renal cell carcinoma is a relatively rare disease, with a lifetime risk in the French population estimated to be 0.0056 for men and 0.0021 for women.20 According to these data, the probability to have 9 RCCs by the age of 90 in 83 individuals from families with members carrying BAP1 mutations is estimated to be 10−8 (95% CI: 0.05–0.20) if applying the larger male probability to the whole cohort. Taking into account that all individuals with known age were younger than 90 years of age and that the 8 individuals affected by RCC were younger than 60 years of age in these families with members carrying BAP1 mutations, the low boundary of RCC relative risk in a BAP1 mutated context is 8-fold (Table S10). Such an elevated risk of RCC in families with members carrying BAP1 mutations strongly suggests that BAP1 is a RCC-predisposition gene. Furthermore, two individuals with BAP1 germline mutations were previously reported with RCC.14,21 Considering the recently described BAP1 cancer syndrome, which includes UM, CM, MPM, and putatively other cancers,22 our findings indicate that RCC should be added to the tumor spectrum of this syndrome.

Because somatic BAP1 deleterious mutations have been associated with high-grade RCCs,16 we evaluated the Fuhrman grade of the four paraffin-embedded tumor slides available. Three RCCs were found to be of grade I-II (family A) and one of grade III (family B). These few cases did not allow definitive conclusions but suggested that germline and somatic BAP1 mutations may have different consequences concerning RCC aggressiveness.

By using this large cohort of families with members carrying BAP1 mutations, we then evaluated a possible predisposition to other cancers besides RCC. Evidence for breast cancer predisposition was ambiguous for the following reasons. Only two breast cancers, including one at early onset, were reported in seven families with members carrying BAP1 mutations published so far.13,14,17,21,23 In the 12 families with members carrying BAP1 mutations reported here, family A was the only one providing two mutation carriers with early-onset breast tumors including a bilateral case, and conversely presented neither UM, nor MPM nor CM. However, it should be noted that index case from family A harbors numerous benign cutaneous naevi. LOH at the BAP1 locus with retention of the mutated BAP1 allele and loss of BAP1 expression were demonstrated for family A breast carcinomas (Figures 1B and S4). However, another second-degree relative also developed a breast cancer at early onset, although not carrying the BAP1 mutation. Thus, the overall incidence of breast tumors in families with members carrying BAP1 mutations was not sufficient to include or exclude this tumor type in the BAP1 syndrome. We further screened 187 unrelated individuals with breast cancer predisposition who tested negative for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations and we failed to identify germline BAP1 truncating mutations, confirming a previous result on an independent series of 47 individuals with breast cancer predisposition.24 Furthermore, somatic BAP1 mutations are found in less than 1% of breast tumors, not supporting a major role for BAP1 in breast cancer.25,26

Predisposition for lung cancers has also been suggested by Abdel-Rahman et al.23 They reported a family with a BAP1 germline truncating mutation and demonstrated the loss of the BAP1 normal allele in a lung carcinoma arising in a mutation carrier. In our study, two BAP1-mutated index cases were affected with lung carcinomas before 55 years old without reported history of smoking (II-1 and I-1 in families G and J, respectively; Figure 2B). Furthermore, the NCI-H226 non-small-cell lung cancer cell line is the first known example of BAP1 inactivation.8 However, somatic mutations of BAP1 were rarely found in large sequencing studies of lung cancers.27,28 Thus, whether BAP1 mutations predispose to breast or lung carcinomas still remain to be determined.

Next-generation sequencing technologies revolutionized the field of human genetics, enabling fast and cost-effective generation of genome-scale sequence data with exquisite resolution and accuracy. Whole-exome sequencing allowed us to find that a BAP1 mutation was the genetic basis of RCC predisposition in a tumor-prone family. By gathering this large cohort of families with members carrying BAP1 mutations, we statistically demonstrated a link between the predisposition to develop RCC and BAP1 germline deleterious mutations. The BAP1 syndrome is a rare entity, which makes it difficult to fully evaluate its clinical spectrum, prevalence in the general population, and actual predisposing risk for cancers. A striking feature is the tumor spectrum heterogeneity among the growing number of reported families with members carrying BAP1 mutations. Possible explanations for this heterogeneity include different consequences of the various BAP1 mutations, influences of the genetic background or of environment factors (asbestos exposure), or biases in selecting individuals for screening. Whether including RCC in the BAP1-associated tumor spectrum will modify genetic testing and lead to identification of familial RCC without other tumor association is yet to be determined. The next challenge required for the management of mutation carriers is to estimate carefully tumor risks from large epidemiological studies.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the family members who participated in this study. The authors would like to thank S. Chanock, C. Houdayer, A. Vincent-Salomon, and E. Heard for helpful discussions; R. Lebofsky and A. Holmes for reviewing the manuscript; M.C. King, S. Giraud, L. Venat, D. Joly, D. Chauveau, and S. Piperno-Neumann for access to individual samples; D. Bellanger, O. Mariani, M. de Lichy, M. Mary, A. Riffault, B. Grandchamp, L. Thomas, and M. Belotti for their contributions; M. Sahbatou and E. Génin for initial genetic studies; the NGS (A.N., P. Legoix-Né) and Sanger (L. Trémolet) platforms; P. Fanen and L. Golmard for help in Exontrap assays; and A. Renier and N. Amirouchene Angelozzi for providing cell lines. This project was supported by grants from Comité de Paris de la Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer, l’Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (ARC), l’Institut National du Cancer (INCa), le Cancéropole Région Ile-de-France, and the Institut Curie Translational department. T.P. was supported by INCa, L.H. by the Translational department and the Ministère de l’Education Nationale, de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche (MERNT), and V.J. by ARC. The NGS platform was supported by grants from Canceropôle Ile de France and Région Ile de France. The EMMA technology is dependent on Curie Institute/CNRS/University Pierre et Marie Curie joint patents. D.S.-L. is a shareholder of Fluigent.

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

Human Genome Variation Society, http://www.hgvs.org/mutnomen/

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.omim.org/

SeattleSeq Annotation 137, http://snp.gs.washington.edu/SeattleSeqAnnotation137/

UCSC Genome Browser, http://genome.ucsc.edu

References

Articles from American Journal of Human Genetics are provided here courtesy of American Society of Human Genetics

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.04.012

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

http://www.cell.com/article/S0002929713001730/pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.04.012

Article citations

Genetic study of the CDKN2A and CDKN2B genes in renal cell carcinoma patients.

Pract Lab Med, 40:e00410, 25 May 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38867760

ITGB2-ICAM1 axis promotes liver metastasis in BAP1-mutated uveal melanoma with retained hypoxia and ECM signatures.

Cell Oncol (Dordr), 47(3):951-965, 27 Dec 2023

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 38150154

Risk Factors and Innovations in Risk Assessment for Melanoma, Basal Cell Carcinoma, and Squamous Cell Carcinoma.

Cancers (Basel), 16(5):1016, 29 Feb 2024

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 38473375 | PMCID: PMC10931186

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Deubiquitinases in cancer.

Nat Rev Cancer, 23(12):842-862, 07 Nov 2023

Cited by: 35 articles | PMID: 37935888

Review

Genomic Profiling and Molecular Characterization of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma.

Curr Oncol, 30(10):9276-9290, 20 Oct 2023

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 37887570 | PMCID: PMC10605358

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (154) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Diseases (Showing 16 of 16)

- (1 citation) OMIM - 300019

- (1 citation) OMIM - 164860

- (1 citation) OMIM - 113705

- (1 citation) OMIM - 614327

- (1 citation) OMIM - 193300

- (1 citation) OMIM - 607273

- (1 citation) OMIM - 607393

- (1 citation) OMIM - 144700

- (1 citation) OMIM - 185470

- (1 citation) OMIM - 191170

- (1 citation) OMIM - 612990

- (1 citation) OMIM - 600185

- (1 citation) OMIM - 136850

- (1 citation) OMIM - 603089

- (1 citation) OMIM - 135150

- (1 citation) OMIM - 608537

Show less

RefSeq - NCBI Reference Sequence Database (3)

- (2 citations) RefSeq - NM_004656.2

- (1 citation) RefSeq - NM_001024660.3

- (1 citation) RefSeq - NM_007064.3

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

A novel germline mutation in BAP1 predisposes to familial clear-cell renal cell carcinoma.

Mol Cancer Res, 11(9):1061-1071, 24 May 2013

Cited by: 92 articles | PMID: 23709298 | PMCID: PMC4211292

Assessment of Risk of Hereditary Predisposition in Patients With Melanoma and/or Mesothelioma and Renal Neoplasia.

JAMA Netw Open, 4(11):e2132615, 01 Nov 2021

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 34767027 | PMCID: PMC8590170

Expanding the clinical phenotype of hereditary BAP1 cancer predisposition syndrome, reporting three new cases.

Genes Chromosomes Cancer, 53(2):177-182, 15 Nov 2013

Cited by: 64 articles | PMID: 24243779 | PMCID: PMC4041196

Genotypic and Phenotypic Features of BAP1 Cancer Syndrome: A Report of 8 New Families and Review of Cases in the Literature.

JAMA Dermatol, 153(10):999-1006, 01 Oct 2017

Cited by: 44 articles | PMID: 28793149 | PMCID: PMC5710339

Review Free full text in Europe PMC