Abstract

Background

Prior studies have suggested an increased risk of oral clefts after exposure to amoxicillin in early pregnancy, but findings have been inconsistent.Methods

Among participants in the Slone Epidemiology Center Birth Defects Study from 1994 to 2008, we identified 877 infants with cleft lip with/without cleft palate and 471 with cleft palate alone. Controls included 6952 nonmalformed infants. Mothers were interviewed about demographic, reproductive and medical factors, and details of medication use. We estimated odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) associated with use of amoxicillin in the first trimester using conditional logistic regression and adjusting for known risk factors for oral clefts, as well as for infections, fever, and concomitant treatments.Results

In the control group, 2.1% of women had used amoxicillin in the first trimester. Maternal use of amoxicillin was associated with an increased risk of cleft lip with/without cleft palate (adjusted OR = 2.0 [95% confidence interval = 1.0-4.1]), with an OR of 4.3 (1.4-13.0) for third-gestational-month use. Risks were not elevated for use of other penicillins or cephalosporins. For cleft palate, the OR for first-trimester amoxicillin was 1.0 (0.4-2.3) with an OR of 7.1 (1.4-36) for third-gestational month use.Conclusions

Amoxicillin use in early pregnancy may be associated with an increased risk of oral clefts.Free full text

Maternal Exposure to Amoxicillin and the Risk of Oral Clefts

Abstract

Background

Prior studies have suggested an increased risk of oral clefts after exposure to amoxicillin in early pregnancy, but findings have been inconsistent.

Methods

Among participants in the Slone Epidemiology Center Birth Defects Study from 1994 to 2008, we identified 877 infants with cleft lip with/without cleft palate (CL/P) and 471 with cleft palate alone (CP). Controls included 6952 non-malformed infants. Mothers were interviewed about demographic, reproductive and medical factors, and details of medication use. We estimated odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) associated with use of amoxicillin in the first trimester using conditional logistic regression and adjusting for known risk factors for oral clefts, as well as for infections, fever, and concomitant treatments.

Results

In the control group, 3% of women had used amoxicillin in the first trimester. Maternal use of amoxicillin was associated with an increased risk of CL/P (adjusted OR= 2.0 [95% CI= 1.0–4.1]), with an OR of 4.3 (1.4–13.0) for third-gestational-month use. Risks were not elevated for use of other penicillins or cephalosporins. For CP, the OR for first-trimester amoxicillin was 1.0 (0.4–2.3), with an OR of 7.1 (1.4–36.4) for third-gestational-month use.

Conclusions

Amoxicillin use in early pregnancy may be associated with an increased risk of oral clefts.

The most commonly prescribed drugs in pregnancy, after prenatal vitamins, are antibiotics.1 Among antibiotics, amoxicillin has been the preferred drug for the treatment of respiratory and urinary tract infections,2 conditions frequently encountered in women of childbearing age. Thus, it is particularly important for clinicians, pregnant women, and public-health officials to have information on the potential teratogenic effects of amoxicillin in order to make risk-benefit judgments on its use early in pregnancy.

Amoxicillin is assigned to pregnancy category B (animal reproduction studies have failed to demonstrate a risk to the fetus and there are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women) by the U.S Food and Drug Administration (FDA).3 While use of amoxicillin during pregnancy has not been associated with most specific congenital malformations in several prior epidemiologic studies,4–6 at least two studies have suggested an increased risk of oral clefts after exposure to amoxicillin in early pregnancy.2, 7 Ampicillin, which is in the same aminopenicillin class as amoxicillin, has also been associated with an increased risk of cleft palate.8

Therefore, the association between the most commonly prescribed antibiotic during pregnancy in North America and oral clefts remains controversial. To test the hypothesis that the risk of oral clefts is associated with maternal use of amoxicillin early in pregnancy, we used data from the Slone Epidemiology Center Birth Defects Study, an ongoing program of case-control surveillance of medications in relation to birth defects.

Methods

Study population

The Birth Defects Study was established in 1976,9 and since that time has interviewed mothers of malformed infants ascertained through review of admissions and discharges at major referral hospitals and clinics in the greater metropolitan areas of Boston, Philadelphia, Toronto and San Diego, as well as through statewide birth defects registries in New York State (since 2004) and in Massachusetts (since 1998). Study subjects include liveborn infants, stillborns, and therapeutic abortions. For hospital-based surveillance, the subjects’ physicians are asked to confirm the diagnosis and mothers are asked to release their medical records in order to permit confirmation of the infant’s condition. Infants with isolated minor defects are excluded. In 1992, a sample of non-malformed infants were added as controls; initially these infants were identified exclusively at study hospitals but, since 1998, the study has also included a population-based random sample of newborns in Massachusetts. Among eligible subjects, the mothers of 73 percent of malformed and 68 percent of non-malformed infants contacted agreed to an interview and provided informed consent. The study has been approved by the Boston University Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the IRBs of all relevant institutions. It is fully compliant with requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). The current analysis was restricted to women interviewed between 1994 and 2008 because full ascertainment of our primary control group (non-malformed infants) was not underway until 1994.

Cases

Cases consisted of 1,348 infants and fetuses with a diagnosis of either cleft lip with or without cleft palate (CL/P, n=877) or cleft palate alone (CP, n=471). We excluded from analysis infants with chromosomal defects (n=1929), known Mendelian inherited disorders (n=188), syndromes (n=193), DiGeorge sequence (associated with 22q deletion, n=20), and amniotic bands (n=57).

Controls

Our primary control group consisted of 6,952 infants without malformations. In the study period 1994–2008, these non-malformed infants were initially recruited at study hospitals (hospital-based) and then more recently population-based birth registries in Massachusetts (since 1998) and in New York State (since 2004). Because mothers of malformed infants may differ from mothers of non-malformed infants in their recall of antenatal drug exposure,10 we included a secondary control group of infants with malformations other than oral clefts. Among all infants with malformations, we excluded those with defects that have been associated with amoxicillin or ampicillin, including cardiac defects.11 Our final malformed controls consisted of 5647 infants. The major diagnostic categories included in this control group were (not mutually exclusive) gastrointestinal-system defects (n=1495), musculoskeletal-system defects (n=1443), urinary-system defects (n=1252), genital-system defects (n=929), and central-nervous-system defects (n=894).

Interviews

Within 6 months of the subject’s delivery, trained study nurses unaware of the study hypothesis interview mothers of study subjects. The 45–60 minute structured telephone interview includes questions on maternal demographic characteristics, medical and obstetric history, habits and occupations, and the use of medication (both prescription and over-the-counter) from two months before conception and throughout pregnancy. Recall of medication exposures is enhanced by questions regarding both indications for use (e.g. infections) and a list of specifically-named medications12 that include amoxicillin, among other antibiotics. Mothers who report taking a particular medication are asked to identify, as accurately as possible, the dates when use began and ended, as well as how certain they are about each of these dates. Interviewers record the certainty of each reported date as follows: (i) “exact,” if the exact date is reported; (ii) “estimated,” if the date provided is stated as an estimate; or (iii) “sometime in a given month,” if the day within a month is unknown. Mothers who cannot recall the month are considered to have unknown dates of exposure. Recall of the timing of medication use is enhanced by the use of a calendar on which the mother records the dates of her last menstrual period (LMP) and delivery. Mothers are also asked about duration (days of treatment), frequency of use (e.g., days per week or month) and specific doses. We defined exposure as systemic use of amoxicillin during the first trimester of pregnancy.

Algorithm to classify timing of exposure

For defining pregnancy dates, the LMP date was most often determined by early ultrasound examination; in the absence of that information, we relied on maternal report of the date she was given by her health care provider. The first trimester of pregnancy was defined as the first three gestational months after the LMP date. We developed an exposure-classification algorithm taking into account recall uncertainty in reported timing of medication exposure.13 For uncertain start/stop dates reported as being sometime in a month, we considered the mother as exposed during the widest possible exposure period. For example, if a mother reported medication use sometime in May, we assigned May 1 as her medication start date and May 31 as her stop date. We classified a mother as being “likely exposed” in the first trimester if the timing and duration of her medication use, independent of date certainty, at least partially included the first trimester; she was considered “possibly exposed” if the use was likely to include the first trimester but, because of uncertain dates and the reported duration, might also fall completely outside the first trimester. To minimize misclassification of exposure for each medication, we included only those women classified as “likely exposed” in our exposure group of primary interest.

Data analysis

We estimated odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for amoxicillin exposure and the risk of CL/P and CP through conditional logistic regression. We defined the reference category as women with no exposure to amoxicillin from 56 days before the LMP date through the end of pregnancy.

We used multivariate conditional logistic regression to adjust for potential confounding in a 3-staged manner: (1) Model 1,which adjusted for geographic area of participants’ residences and calendar year of ascertainment (to account for secular trends and regional variations in use of antimicrobials as well as recruitment of cases with specific malformations); (2) Model 2, which included model 1 plus risk factors for oral clefts (maternal age, race, education level, pre-pregnancy BMI, family history of oral clefts, diabetes mellitus, first-trimester cigarette smoking, peri-conceptional folic acid supplementation, and multiple pregnancy); (3) Model 3, which included model 2 plus infection-related factors (urinary tract, respiratory, or vaginal/yeast infection, sexually transmitted disease, other infect ions, and febrile events in the first trimester with or without treatment). Statistical analyses were conducted with SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Secondary and sensitivity analyses

The primary outcomes of interest were CL/P and CP with or without other birth defects (except for those excluded, as noted above); in a secondary analysis, only isolated CL/P and CP were considered. To assess whether amoxicillin use was unselectively associated with all birth defects, we compared the proportion of amoxicillin use in non-malformed controls with amoxicillin use in the largest categories among the malformed controls (4132 infants with cardiovascular system defects, 1138 with central nervous system defects, 1825 with gastrointestinal system defects, and 1948 with musculoskeletal system defects). Given previous suggestions that amoxicillin and smoking may share similar chemical structures that may be linked to increased risk of oral clefts,14, 15 we also examined the interaction between cigarette smoking and amoxicillin use in the first trimester on the risk of clefts. In the conditional logistic regression, we included an interaction term (product of the smoking and amoxicillin exposure variables), and we estimated ORs and CIs for smoking but no amoxicillin exposure, amoxicillin use but no smoking, and both smoking and amoxicillin in the first trimester — each compared with neither amoxicillin use nor cigarette smoking during pregnancy. Also, the risks of clefts in those exposed to amoxicillin in the 1st trimester were compared for first-trimester smokers and those who did not smoke during pregnancy.

Results

Antibiotic use during pregnancy

Among the non-malformed control group, 10.9% of women reported having used at least one antibiotic in the first trimester, the most common type being amoxicillin (3.0%), followed by macrolide antibiotics (1.3%). Ampicillin was used by 0.1% of women in the first trimester. Overall, 5.4% reported having taken an antibiotic whose name they could not recall (“not otherwise specified”, or “NOS”); therefore, the proportions for specific antibiotics are likely to be slightly underestimated.

Characteristics of study participants

Table 1 provides selected characteristics for cases and non-malformed controls. Geographical region of residence and calendar time were both highly associated with the frequency of oral clefts because of secular trends and regional variations in recruitment of study subjects. Therefore the estimates we present are adjusted for region and calendar year.

Table 1

Baseline characteristics among mothers of infants with oral clefts and a control group of mothers with non-malformed infants, Slone Epidemiology Cener Birth Defects Study, 1994–2008.

| Oral Clefts | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Levels | Controls (n=6952) | CL/P (n=877) | CP (n=471) | ||

| No (%) | No (%) | OR (95 % CI)a | No (%) | OR (95 % CI)a | ||

| Mother's age (years) | <20 | 394 (6) | 51 (6) | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 24 (5) | 0.9 (0.6–1.5) |

| 20–24 | 888 (13) | 152 (17) | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) | 52 (11) | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) | |

| 25–29 | 1703 (25) | 221 (25) | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) | 153 (33) | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | |

| 30–34 | 2460 (35) | 288 (33) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 158 (34) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | |

| 35–39b | 1254 (18) | 145 (17) | 1.0 | 68 (14) | 1.0 | |

| >=40 | 253 (4) | 20 (2) | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) | 16 (3) | 1.0 (0.6–1.7) | |

| Mother's race | Non-Hispanic whiteb | 5144 (74) | 622 (71) | 1.0 | 351 (75) | 1.0 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 489 (7) | 58 (7) | 1.0 (0.7–1.3) | 29 (6) | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | |

| Hispanic | 844 (12) | 113 (13) | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 47 (10) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | |

| Asian, Pacific Islander | 336 (5) | 64 (7) | 1.6 (1.2–2.1) | 32 (7) | 1.4 (1.0–2.0) | |

| Other /Not available | 139 (2) | 20 (2) | 1.2 (0.7–1.9) | 12 (3) | 1.3 (0.7–2.3) | |

| Mother's education (years) | <13b | 1890 (27) | 306 (35) | 1.0 | 140 (30) | 1.0 |

| 13–15 | 1699 (24) | 232 (27) | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) | 122 (26) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | |

| >=16 | 3363 (48) | 339 (39) | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) | 209 (44) | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) | |

| Mother's Prepregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | <18.5 | 423 (6) | 53 (6) | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 26 (6) | 1.0 (0.7–1.5) |

| 18.5–24.9b | 4340 (62) | 505 (58) | 1.0 | 264 (56) | 1.0 | |

| 25–29.9 | 1334 (19) | 176 (20) | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 110 (23) | 1.4 (1.1–1.7) | |

| 30–34.9 | 475 (7) | 78 (9) | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 37 (8) | 1.3 (0.9–1.8) | |

| 35–39.9 | 167 (2) | 33 (4) | 1.7 (1.2–2.5) | 18 (4) | 1.8 (1.1–2.9) | |

| >=40 | 91 (1) | 12 (1) | 1.1 (0.6–2.1) | 7 (2) | 1.3 (0.6–2.8) | |

| Not available | 122 (2) | 20 (2) | 1.4 (0.9–2.3) | 9 (2) | 1.2 (0.6–2.4) | |

| Diabetes Mellitus | Noneb | 6618 (95) | 810 (92) | 1.0 | 442 (94) | 1.0 |

| Diagnosed before pregnancy | 37 (1) | 12 (1) | 2.7 (1.4–5.1) | 8 (2) | 3.2 (1.5–7.0) | |

| Diagnosed during pregnancy | 290 (4) | 53 (6) | 1.5 (1.1–2.0) | 19 (4) | 1.0 (0.6–1.6) | |

| Folic acid supplementation | Noneb | 248 (4) | 36 (4) | 1.0 | 16 (3) | 1.0 |

| Peri-conceptional useb | 4431 (64) | 489 (56) | 0.8 (0.5–1.1) | 295 (63) | 1.0 (0.6–1.7) | |

| Family history of oral clefts | Noneb | 6895 (99) | 770 (88) | 1.0 | 440 (93)c | 1.0 |

| First-degree | 10 (<1) | 57 (7) | 51.0 (25.9–100.2) | 21 (5) c | 15.7 (8.5–28.9) | |

| Second-degree | 26 (<1) | 36 (4) | 12.4 (7.4–20.6) | 6 (1) c | 5.2 (2.1–13.2) | |

| Third-degree | 21 (<1) | 14 (2) | 6.0 (3.0–11.8) | 4 (1) c | 3.5 (1.2–10.3) | |

| Multiple pregnancy | Singleb | 6749 (97) | 840 (96) | 1.0 | 444 (94) | 1.0 |

| Multiple | 203 (3) | 37 (4) | 1.5 (1.0–2.1) | 27 (6) | 2.0 (1.3–3.1) | |

| Smoking in the 1st trimester e | Non-smokerb | 4034 (58) | 481 (55) | 1.0 | 280 (59) | 1.0 |

| Active smoker in the 1st trimester | 1207 (17) | 199 (23) | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) | 90 (19) | 1.1 (0.8–1.4) | |

| Ex-smoker/ smoked outside the 1st trimester | 1711 (25) | 197 (23) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 101 (21) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | |

| Infection in the 1st trimester e, f | No infection during pregnancyb | 1523 (22) | 183 (21) | 1.0 | 98 (21) | 1.0 |

| Urinary tract infection | 254 (4) | 27 (3) | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) | 19 (4) | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) | |

| Respiratory infection | 1171 (17) | 167 (19) | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) | 85 (18) | 1.1 (0.8–1.4) | |

| Yeast/vaginal | 355 (5) | 49 (6) | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 26 (6) | 1.1 (0.7–1.6) | |

| Sexually transmitted infection | 127 (2) | 15 (2) | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) | 9 (2) | 1.0 (0.5–2.1) | |

| Others | 427 (6) | 72 (8) | 1.4 (1.0–1.8) | 36 (8) | 1.3 (0.9–1.8) | |

| Febrile event | Noneb | 5601 (81) | 698 (80) | 1.0 | 384 (82) | 1.0 |

| Fever <101° F in the 1st trimester | 130 (2) | 28 (3) | 1.7 (1.1–2.6) | 8 (2) | 0.9 (0.4–1.8) | |

| Fever ≥101° F in the 1st trimester | 201 (3) | 28 (3) | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | 15 (3) | 1.1 (0.6–1.9) | |

Amoxicillin and the risk of oral clefts

Table 2 shows the ORs of CL/P and CP associated with first-trimester exposure to amoxicillin using non-malformed controls. Region- and year-adjusted ORs were not appreciably influenced by further adjustment for risk factors and infection variables. Based on the fully adjusted model, maternal use of amoxicillin in the first trimester was associated with an increased risk of CL/P (OR= 2.0 [95% CI= 1.0–4.1]). The corresponding OR for CP was 1.0 (0.4–2.3).

Table 2

Maternal exposure to amoxicillin and risk of oral clefts, Slone Epidemiology Cener Birth Defects Study, 1994–2008.

| Cases N=877) No (%) | Non-malformed Controls (n=6952) No (%) | Crude OR (95 % CI) | Model 1 Adjusted OR (95 % CI)a | Model 2 Adjusted OR (95 % CI)a | Model 3 Adjusted OR (95 % CI)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cleft lip with or without cleft palate | ||||||

| No exposure to amoxicillin during pregnancyb | 810 (92.4) | 6379 (91.8) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Likely exposure to amoxicillin in the 1st trimesterc | 28 (3.2) | 144 (2.1) | 1.5 (1.0–2.3) | 1.9 (1.0–3.6) | 1.9 (1.0–3.6) | 2.0 (1.0–4.1) |

| Cleft palate alone | ||||||

| No exposure to amoxicillin during pregnancyb | 434 (92.1) | 6379 (91.8) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Likely exposure to amoxicillin in the 1st trimesterc | 11 (2.3) | 144 (2.1) | 1.1 (0.6–2.1) | 1.1 (0.5–2.4) | 1.1 (0.5–2.4) | 1.0 (0.4–2.3) |

Model 2: Model 1 + maternal age, race, education level, pre-pregnancy BMI, family history of oral clefts, diabetes mellitus, first trimester cigarette smoking, peri-conceptional folic acid supplement, and multiple pregnancy.

Model 3: Model 2 + urinary tract, respiratory, or vaginal/yeast infection, sexually transmitted disease, other kinds of infection, and/or febrile events that occurred in the first trimester.

Role of confounding by indication: other antibiotic use and oral clefts

We did not identify positive associations between CL/P or CP and any other specific antibiotics, including penicillins other than aminopenicillins, macrolides, and cephalosporins (data not shown). We were not able to evaluate the association between oral clefts and ampicillin because there were fewer than five exposed subjects (data not shown).

Role of recall bias and exposure misclassification

To assess the potential differential recall between mothers of malformed and non-malformed infants, we used infants with malformations other than CL/P as the reference; for CL/P, the risk estimate did not change appreciably, and for CP, it increased modestly (Table 3). In a sensitivity analysis, we excluded from the reference group the 5.4 % of women who took antibiotics not otherwise specified (since those in this group who actually took amoxicillin would incorrectly be assigned to the reference group). This did not materially change our results. For instance, the OR of CL/P associated with likely exposure in the first trimester was 1.9 (0.93–3.7) with reference group as “no exposure to either amoxicillin or antibiotic not otherwise specified during pregnancy” (data not shown).

Table 3

Sensitivity of results to recall bias,a Slone Epidemiology Cener Birth Defects Study, 1994–2008.

| Case (n=877) No (%) | Malformed controls (n=5647) No (%) | Crude OR (95 % CI) | Adjusted ORb (95 % CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cleft lip with or without cleft palate | ||||

| No exposure to amoxicillin during pregnancyc | 810 (92.4) | 5226 (92.5) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Likely exposure to amoxicillin in the 1st trimesterd | 28 (3.2) | 109 (1.9) | 1.7 (1.1–2.5) | 1.8 (0.9–3.4) |

| Cleft palate alone | ||||

| No exposure to amoxicillin during pregnancyc | 434 (92.1) | 5226 (92.5) | 1.0 | |

| Likely exposure to amoxicillin in the 1st trimesterd | 11 (2.3) | 109 (1.9) | 1.2 (0.6–2.3) | 0.7 (0.3–1.8) |

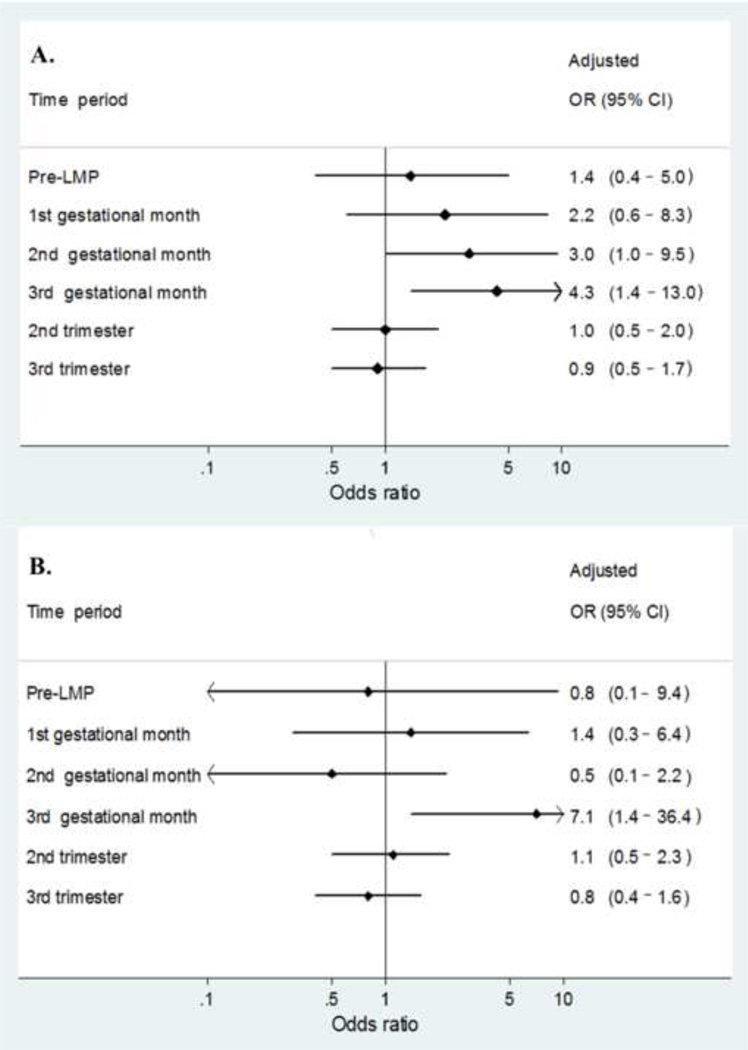

We calculated ORs of CL/P or CP for each gestational month (Figure) to evaluate whether the observed risks were greatest during the exposure window that most closely approximated the etiologically relevant periods for development of CL/P and CP. The critical period of CL/P is between 7th and 10th gestational weeks and that of CP from 9th to 11th gestational weeks.16 The risk elevations for both CL/P and CP are generally consistent with the respective gestational months during which these particular defects develop.

Maternal likely exposure to amoxicillin and the risk of A., cleft lip with or without cleft palate and B., cleft palate alone by specific time period during pregnancy

Considering only isolated clefts (i.e., without other major birth defects), the OR for likely exposure to amoxicillin in the first trimester was 1.6 (0.7–3.8) for CL/P and 1.3 (0.5–3.6) for CP.

Use of amoxicillin and other birth defects

We did not find associations between first-trimester exposure to amoxicillin and the risk of most other major birth defects, such as cardiovascular system (OR= 1.3 [95% CI= 0.9–1.9]), central nervous system (0.9 [0.5–1.7]), gastrointestinal system (1.1 [0.7–1.9]), urinary system defects (1.2 [0.7–1.9]) and musculoskeletal system defects (1.0 [0.6–1.6]).

Potential interaction between amoxicillin and smoking on the risk of CL/P

The elevated risk of CL/P associated with likely exposure to amoxicillin in the first trimester was confined to non-smokers (2.0 [1.0–4.1]); the OR among smokers was 1.0 (0.3–3.0). Compared with neither amoxicillin use nor cigarette smoking during pregnancy, the OR for CL/P was 1.3 (1.1–1.7) for smoking but no amoxicillin use, 2.0 (1.0–3.9) for amoxicillin use but no smoking, and 1.1 (0.4–3.0) for both smoking and amoxicillin use in the first trimester. The corresponding estimates for CP could not be reliably calculated due to small numbers.

Discussion

In our study population, we found a 2-fold increased risk of CL/P associated with maternal use of amoxicillin during the first trimester of pregnancy, and no increase in risk for CP. Of importance, however, is that for both types of clefts, risks were greatest for exposures occurring during their respective developmental periods. Indeed, the risk for CP was markedly elevated (OR= 7.1) for 3rd month exposures, although small numbers yielded a very wide confidence interval (1.4–36).

Taken overall, our findings are consistent with those from a case-control study7 that identified a 5-fold increased risk of CL/P associated with prenatal exposure to amoxicillin in the 2nd and 3rd gestational months. Our results are also compatible with results from a large cohort study in the US that compared use of amoxicillin to no antibiotic in the first 4 gestational months and observed a modest increased risk for oral clefts (OR= 1.7 [95% CI= 0.6–5.0]). Results from the National Birth Defects Prevention Study did not focus on amoxicillin specifically17 but rather considered penicillins overall; consistent with our findings, they did not identify a positive association between penicillins and oral clefts. Due to limited numbers, we could not test the previously hypothesized association between ampicillin and CP.8, 10

As is true for any observational study, we had to confront a number of challenges. First, to correct for secular trends and regional variations in both patterns of use of antimicrobials and case ascertainment , we stratified our analyses by the joint strata of geographical region of residence and calendar year of ascertainment in a conditional logistic regression. This approach assumed that region of residence is a proxy for antibiotic prescription patterns in the area. The OR of CL/P associated with maternal use of amoxicillin in the first trimester increased from 1.5 (95% CI= 1.0–2.3) without any adjustment to 1.7 (1.1–2.6) after adjusting for interview year alone, and to 1.9 (1.0–3.6) after adjusting for interview year and region of residence. Thus, results were affected by adjustment for region and calendar year. This association is unlikely to be explained by biases, because neither exposure during second and third trimester nor exposure to other antibiotics was associated with CL/P. Moreover, amoxicillin use was not associated with other malformations, with or without regional stratification.

Second, if mothers of infants with birth defects (in this case, CL/P and CP) more completely recall their use of amoxicillin during pregnancy than mothers of non-malformed controls, our results could be due to recall bias. However, when we used a control series composed of other malformed infants, the observed associations did not weaken. In addition, the associations were largely restricted to amoxicillin use during the embryologically critical periods for both CL/P and CP, which makes recall bias unlikely and at the same time adds biologic plausibility to our findings.

Third, the association with CL/P and CP could be due to risk factors related to infections that prompted amoxicillin therapy, rather than to amoxicillin exposure itself (i.e., confounding by indication). However, other antibiotics were not associated with CL/P or CP, and adjustment for infection-related variables (e.g., specific types of infection with or without antibiotic use, febrile events in the first trimester, and duration of the fever) did not materially influence our findings.

Most nonsyndromic oral clefts are thought to be caused by an interaction between polygenic and environmental factors,18 but the exact mechanisms remain largely unknown. Amoxicillin can cross the placenta and could potentially influence fetal organogenesis.19 The fact that the current and prior studies found increased risks after prenatal exposure to aminopenicillins but not to other penicillins17 suggests that the aminobenzyl group may play a role in the development of oral clefts. Interestingly, maternal smoking of tobacco, which contains aromatic amines, has also been linked to the risk of CL/P.14, 20 Because aromatic amines in cigarette smoke and the aminobenzyl group in amoxicillin might share some structural similarities, it is of interest that the increased risk of CL/P associated with first-trimester maternal use of amoxicillin was evident only among non-smokers, whereas the risk was close to the null (with wide confidence intervals) among smokers. We cannot easily explain this observation. If the effect modification is not a chance finding, one possibility might be competitive effects between smoking and amoxicillin on the risk of CL/P (and possibly CP). Given the limited power to examine this interaction, these results should be considered hypothesis-generating. Further studies are needed to confirm our observations related to smoking and, if they are confirmed, to assess the potential etiologic roles of these amines on the development of oral clefts.

It is important to keep in perspective the absolute risk of CL/P after exposure to amoxicillin during early pregnancy. Given the baseline risk for oral clefts of about 1–2 per 1,000 live births, a two-fold risk among women who use amoxicillin in the first trimester would increase clefts risk to about 2–4 per 1,000 — quite modest in absolute terms or compared with the overall baseline risk of major malformations at birth of about 30/1,000.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Slone Epidemiology Center Birth Defects Study and the thousands of women who generously participate in the study.

Sources of financial support:

This project is supported by grant R01 HD046595-04 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child and Human Development (NICHD).

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1097/ede.0b013e318258cb05

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://journals.lww.com/epidem/Fulltext/2012/09000/Maternal_Exposure_to_Amoxicillin_and_the_Risk_of.9.aspx

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1097/ede.0b013e318258cb05

Article citations

A Review of Hidradenitis Suppurativa in Special Populations: Considerations in Children, Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women, and the Elderly.

Dermatol Ther (Heidelb), 14(9):2407-2425, 04 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39230800 | PMCID: PMC11393272

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Dietary Exposure to Pesticide and Veterinary Drug Residues and Their Effects on Human Fertility and Embryo Development: A Global Overview.

Int J Mol Sci, 25(16):9116, 22 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39201802 | PMCID: PMC11355024

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Characteristics of Factors Influencing the Occurrence of Cleft Lip and/or Palate: A Case Analysis and Literature Review.

Children (Basel), 11(4):399, 28 Mar 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38671616 | PMCID: PMC11049449

Management of Acne in Pregnancy.

Am J Clin Dermatol, 25(3):465-471, 07 Mar 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38453786

Review

Assessment of non-syndromic orofacial cleft severity and associated environmental factors in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study.

Saudi Dent J, 36(3):480-485, 28 Dec 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38525175 | PMCID: PMC10960119

Go to all (22) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

First-trimester nonsystemic corticosteroid use and the risk of oral clefts in Norway.

Ann Epidemiol, 24(9):635-640, 08 Jul 2014

Cited by: 8 articles | PMID: 25127739 | PMCID: PMC4161959

Low maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy and oral clefts in offspring: the Slone Birth Defects Study.

Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol, 67(7):509-514, 01 Jul 2003

Cited by: 24 articles | PMID: 14565622

Lack of relation of oral clefts to diazepam use during pregnancy.

N Engl J Med, 309(21):1282-1285, 01 Nov 1983

Cited by: 85 articles | PMID: 6633586

Maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy and the risk of having a child with cleft lip/palate.

Plast Reconstr Surg, 105(2):485-491, 01 Feb 2000

Cited by: 97 articles | PMID: 10697150

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NICHD NIH HHS (2)

Grant ID: R01 HD046595

Grant ID: R01 HD046595-04