Abstract

Rationale

We hypothesized that providing patients with acute lung injury two different protein/calorie nutritional strategies in the intensive care unit may affect longer-term physical and cognitive performance.Objectives

To assess physical and cognitive performance 6 and 12 months after acute lung injury, and to evaluate the effect of trophic versus full enteral feeding, provided for the first 6 days of mechanical ventilation, on 6-minute-walk distance, cognitive impairment, and secondary outcomes.Methods

A prospective, longitudinal ancillary study of the ARDS Network EDEN trial evaluating 174 consecutive survivors from 5 of 12 centers. Blinded assessments of patients' arm anthropometrics, strength, pulmonary function, 6-minute-walk distance, and cognitive status (executive function, language, memory, verbal reasoning/concept formation, and attention) were performed.Measurements and main results

At 6 and 12 months, respectively, the mean (SD) percent predicted for 6-minute-walk distance was 64% (22%) and 66% (25%) (P = 0.011 for difference between assessments), and 36 and 25% of survivors had cognitive impairment (P = 0.001). Patients performed below predicted values for secondary physical tests with small improvement from 6 to 12 months. There was no significant effect of initial trophic versus full feeding for the first 6 days after randomization on survivors' percent predicted for 6-minute-walk distance, cognitive impairment status, and all secondary outcomes.Conclusions

EDEN trial survivors performed below predicted values for physical and cognitive performance at 6 and 12 months, with some improvement over time. Initial trophic versus full enteral feeding for the first 6 days after randomization did not affect physical and cognitive performance.Free full text

Physical and Cognitive Performance of Patients with Acute Lung Injury 1 Year after Initial Trophic versus Full Enteral Feeding. EDEN Trial Follow-up

Abstract

Rationale: We hypothesized that providing patients with acute lung injury two different protein/calorie nutritional strategies in the intensive care unit may affect longer-term physical and cognitive performance.

Objectives: To assess physical and cognitive performance 6 and 12 months after acute lung injury, and to evaluate the effect of trophic versus full enteral feeding, provided for the first 6 days of mechanical ventilation, on 6-minute-walk distance, cognitive impairment, and secondary outcomes.

Methods: A prospective, longitudinal ancillary study of the ARDS Network EDEN trial evaluating 174 consecutive survivors from 5 of 12 centers. Blinded assessments of patients’ arm anthropometrics, strength, pulmonary function, 6-minute-walk distance, and cognitive status (executive function, language, memory, verbal reasoning/concept formation, and attention) were performed.

Measurements and Main Results: At 6 and 12 months, respectively, the mean (SD) percent predicted for 6-minute-walk distance was 64% (22%) and 66% (25%) (P = 0.011 for difference between assessments), and 36 and 25% of survivors had cognitive impairment (P = 0.001). Patients performed below predicted values for secondary physical tests with small improvement from 6 to 12 months. There was no significant effect of initial trophic versus full feeding for the first 6 days after randomization on survivors’ percent predicted for 6-minute-walk distance, cognitive impairment status, and all secondary outcomes.

Conclusions: EDEN trial survivors performed below predicted values for physical and cognitive performance at 6 and 12 months, with some improvement over time. Initial trophic versus full enteral feeding for the first 6 days after randomization did not affect physical and cognitive performance.

The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Clinical Trials Network (ARDS Network) of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) published a multicenter, randomized, open-label trial of initial trophic versus full enteral feeding for up to 6 days in patients with acute lung injury (ALI) (the “EDEN trial”) (1). This trial demonstrated no significant difference in short-term outcomes, including ventilator-free days through Day 28 and 60-day mortality. Moreover, subsequent evaluation of patient-reported physical and psychological outcomes of EDEN survivors at 6 and 12 months after ALI showed little or no difference between initial trophic versus full feeding (2). However, further evaluation of the effect of these nutritional strategies on muscle strength and performance-based physical outcome measures is necessary (2, 3) because the relationship between self-reported and performance-based outcome measures is unclear (4) and because initial trophic feeding may exacerbate protein limitations in the intensive care unit (ICU) (5), with the potential for muscle loss (6), persistent muscle weakness, and functional impairment (7–11). Furthermore, the effect of nutritional strategies on longer-term cognitive outcomes in critically ill patients is unknown. Hence, evaluating physical and cognitive performance is important in understanding the longer-term effects of ICU-based nutritional strategies on ALI survivors.

In this study, prospective longitudinal evaluation of physical and cognitive performance at 6 and 12 months after ALI was undertaken for EDEN study participants via in-depth, in-person, performance-based tests. This research was conducted via two separate NHLBI-funded ancillary studies to the original EDEN trial. The objectives of this study were to (1) assess patient upper arm anthropometrics, global muscle strength, pulmonary function, 6-minute-walk distance, and cognition (based on tests of executive function, language, memory, verbal reasoning/concept formation, and attention) 6 and 12 months after ALI, and (2) evaluate the effect of initial trophic versus full enteral feeding on 6-minute-walk distance and cognitive impairment, and secondary outcome measures.

Methods

Five of the 12 EDEN study centers, representing 12 hospitals, participated in this prospective, longitudinal study, with follow-up occurring between July 2008 and May 2012. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at all participating hospitals. Each patient or their proxy (when the patient was incapable of consent) provided informed consent to participate in this follow-up study.

Study Population

The eligibility criteria of the EDEN trial have been reported previously (1). EDEN trial patients were excluded from this follow-up study if they had potential baseline cognitive impairment (e.g., preexisting dementia, stroke, traumatic brain injury, psychiatric disorder with psychosis, mental retardation, or similar conditions, ascertained via medical records and patient/proxy interview), or were non–English speaking, homeless, or under 18 years of age. Those in the trophic versus full feeding groups of the EDEN trial received about 400 versus 1,300 kcal/day beginning within 6 hours of randomization until the earlier of extubation, death, or Day 6 after randomization. After 6 days, patients in the trophic feeding group who were still on mechanical ventilation were transitioned to full feeding. The first 272 of 1,000 patients enrolled in EDEN were simultaneously randomized to a separate blinded trial (the OMEGA study) comparing a nutritional supplement containing omega-3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus an isocaloric, isovolemic control in a 2 × 2 factorial design (1). In our study, 29 of 174 (17%) patients were coenrolled in the OMEGA trial and randomized to receive the active nutritional supplement. All patients were managed with simplified versions of the ARDS Network lung-protective ventilation (12) and fluid-conservative hemodynamic management (13) protocols. Blood glucose control targeted 80 to 150 mg/dl (with tighter control permitted), using institution-specific insulin protocols (1).

Study Procedures

Research personnel underwent in-person training and annual in-person quality assurance reviews for conducting the physical and cognitive performance tests in this study. At study sites that did not routinely assess for delirium, research staff also conducted validated and reliable daily assessments of sedation status (using the Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale [RASS] [14], with “coma” defined as a score of –4 or –5) and delirium status (using the Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU [CAM-ICU] [15]). In addition, research staff collected baseline comorbidity status (using the Charlson Comorbidity Index [16]) and daily ICU medication use (for narcotics, benzodiazepines, corticosteroids, insulin, and catecholamines) from the medical record. Research staff completed physical and cognitive performance tests (details below) at 6 and 12 months after ALI onset and were blinded to treatment allocation. Published methods were used to minimize loss to follow-up (17–22), including conducting research visits at patients’ homes or health care facilities for those who were unable to attend the research clinic. In addition, as previously validated (23), the detailed cognitive performance tests were completed by telephone if an in-person visit was not feasible.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes: Physical Performance

For physical performance, the primary outcome was the 12-month 6-minute-walk test (6MWT) as a percentage of the predicted value (24, 25). Patients who were unable to walk because of ICU-acquired functional impairment were assigned a 6MWT distance of 0 (with an a priori sensitivity analysis performed, excluding these patients from analysis of the 6MWT score). Secondary physical outcomes were as follows: 4-m timed walk speed (in meters per second) (26–28); manual muscle testing using the Medical Research Council sum score (range, 0 to 60; <48 indicating “ICU-acquired weakness” [10, 29, 30]); percentage of predicted value for hand grip strength (31), maximal inspiratory pressure (32, 33), FEV1, and FVC (34, 35); body mass index (BMI); and percent fat and muscle areas based on upper arm anthropometric assessment (calculated on the basis of the mean of three triceps skinfold and three mid-arm circumference measurements) (36, 37).

Primary and Secondary Outcomes: Cognitive Performance

A battery of validated and standardized performance tests of the most relevant cognitive domains for ALI survivors (23) was performed, with the primary outcome being “cognitive impairment” at 12 months, conservatively defined as having either one cognitive test within the battery with a score at least 2 SDs below population norms (i.e., bottom 2.5%) or at least two tests with a score equal to or greater than 1.5 SDs below norms (i.e., bottom 6.7% for both tests) (38). Secondary outcomes include individual results on specific cognitive tests, presented as both continuous scores and as binary outcomes (score ≥ 1.5 SDs below norm). The following cognitive domains were evaluated with the test battery: (1) executive function, evaluated via the Hayling Sentence Completion Test scaled score (range, 1 to 10; higher is better) (39); (2) language, evaluated via the Controlled Oral Word Association (COWA) total score (higher score is better) (40); (3) immediate and delayed memory, evaluated via the Logical Memory I and Logical Memory II age-adjusted scaled scores (range, 1 to 19; higher is better) from the Wechsler Memory Scale-Third Edition (41, 42); (4) verbal reasoning and concept formation, evaluated via the Similarities age-adjusted scaled score (range, 1 to 19; higher is better) from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Third Edition (41, 42); and (5) attention and working memory evaluated via the Digit Span age-adjusted scaled score (range, 1 to 19; higher is better) from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Third Edition (41, 42).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted according to an a priori written statistical analysis plan. Only the study biostatisticians had access to patient treatment allocation data, which were provided by the ARDS Network only after all data were finalized and the study database was locked. Analyses were performed in accordance with the intention to treat principle, using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and R statistical software (R Development Core, Vienna, Austria). A two-sided P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

For the continuous and binary outcome measures assessed at 6 and 12 months, linear and logistic regression models were created, using generalized estimating equations with an exchangeable correlation model (43), with an indicator for treatment group (initial trophic vs. full feeding), follow-up time (12 vs. 6 mo), and the interaction of treatment group and time. For patients coenrolled in the OMEGA trial, to evaluate whether study results for initial trophic versus full feeding changed on the basis of OMEGA treatment allocation, the previously described regression model for the primary physical and cognitive outcomes included a statistical interaction between OMEGA assignment and EDEN treatment group. A priori subgroup analyses and statistical interactions were evaluated for both of the primary outcome variables, based on the following baseline variables: shock (present [on vasopressors or mean arterial pressure < 60 mm Hg] vs. absent), ALI subgroup (PaO2/FiO2 [fraction of inspired oxygen] ≤ 200 vs. > 200), and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health III (APACHE III) score as a continuous variable. For the primary physical outcome, the following additional a priori subgroup analyses and statistical interactions were evaluated on the basis of the following baseline variables: BMI (<25, 25 to <30, ≥30 kg/m2), sex, baseline Functional Performance Inventory-Short Form score (44, 45), and baseline Short Form-36 Physical Function domain score (46). The latter two measures were survey-based evaluations completed after hospital discharge to obtain a retrospective estimate of baseline status because prospective baseline assessment is not possible given the acute onset of ALI (47–50). Also, on an a priori basis, covariates were prespecified to be included in adjusted analyses of the primary outcomes if potentially important imbalances existed between the randomized groups (see below).

The available data were included in all statistical analyses. For missing RASS and CAM-ICU data, multiple imputation using chained equations (51), with five imputed data sets, was implemented. If the initial ICU day’s assessment was missing, multiple imputation was completed on the basis of clinically relevant predictors measured within the study. Missing data on subsequent days of the ICU stay were similarly imputed, using the same set of clinically relevant predictors plus RASS or CAM-ICU status on the prior day. P values for the imputed data sets were calculated according to standard methods (52).

Results

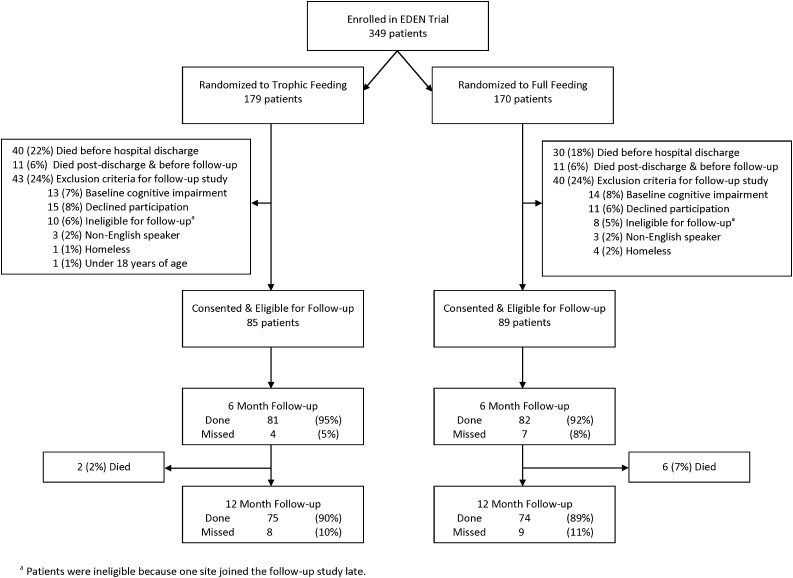

At the five study centers (12 hospitals) participating in this follow-up study, 349 patients were enrolled in the EDEN trial. Of these 349 patients, 20% died before hospital discharge, 6% died after discharge but before follow-up, and 24% met exclusion criteria with no significant differences between the two treatment groups (Figure 1). For the 174 patients who consented and were eligible for follow-up, most baseline characteristics were similar for both treatment groups, with a mean (SD) age of 47 (14) years, 50% male, 49% with more than high school education (Table 1), and mean (SD) ICU and hospital lengths of stay of 15 (12) and 22 (16) days, respectively. However, potentially important differences existed between groups (Table 1) for the following covariates, which were selected a priori for consideration in adjusted statistical analyses of treatment effect: sex, years of education, pneumonia/sepsis as ALI risk factor, APACHE III score, dialysis in hospital, sedation status, and ICU medications (catecholamines, steroids, insulin, and neuromuscular blocker).

TABLE 1.

PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

| Characteristic | All (n = 174)* | Trophic Feeding (n = 85)* | Full Feeding (n = 89)* | P Value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline status before hospital admission | ||||

Age, yr Age, yr | 47 (14) | 48 (14) | 47 (14) | 0.433 |

Male, no. (%) Male, no. (%) | 87 (50) | 45 (53) | 42 (47) | 0.448 |

White, no. (%) White, no. (%) | 157 (91) | 78 (92) | 79 (90) | 0.651 |

More than high school education, no. (%) More than high school education, no. (%) | 85 (49) | 38 (45) | 47 (53) | 0.285 |

Body mass index, kg/m2 Body mass index, kg/m2 | 32 (8) | 31 (8) | 32 (9) | 0.754 |

Corticosteroid use, no. (%) Corticosteroid use, no. (%) | 17 (10) | 10 (12) | 7 (9) | 0.426 |

Living independently at home Living independently at home | 161 (93) | 79 (93) | 82 (92) | 0.840 |

Employed, no. (%) Employed, no. (%) | 85 (49) | 42 (49) | 43 (49) | 0.999 |

Short Form-36 Physical Function score‡ Short Form-36 Physical Function score‡ | 68 (31) | 70 (31) | 66 (32) | 0.419 |

Functional Performance Inventory score‡ Functional Performance Inventory score‡ | 2.3 (0.6) | 2.3 (0.6) | 2.2 (0.6) | 0.667 |

Charlson Comorbidity Index Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1.2 (1.6) | 1.2 (1.7) | 1.1 (1.5) | 0.759 |

Comorbidities at admission Comorbidities at admission | | | | |

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, no. (%) Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, no. (%) | 31 (18) | 11 (13) | 7 (8) | 0.272 |

Moderate or severe kidney disease, no. (%) Moderate or severe kidney disease, no. (%) | 13 (8) | 5 (6) | 8 (9) | 0.436 |

Moderate or severe liver disease, no. (%) Moderate or severe liver disease, no. (%) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1.000 |

Cardiovascular disease Cardiovascular disease | 24 (14) | 12 (14) | 12 (14) | 0.903 |

Diabetes Diabetes | 41 (24) | 21 (25) | 20 (23) | 0.729 |

History of cancer History of cancer | 15 (8.6) | 6 (7.1) | 9 (10.1) | 0.473 |

Neurologic, no. (%) Neurologic, no. (%) | 16 (9) | 9 (11) | 7 (8) | 0.534 |

Psychiatric, no. (%) Psychiatric, no. (%) | 66 (38) | 32 (38) | 34 (38) | 0.940 |

History of smoking, no. (%) History of smoking, no. (%) | 106 (61) | 49 (58) | 57 (64) | 0.441 |

Alcohol abuse or drug use, no. (%) Alcohol abuse or drug use, no. (%) | 39 (22) | 20 (24) | 19 (21) | 0.730 |

| Critical illness characteristics | ||||

Pneumonia or sepsis as ALI risk factor, no. (%) Pneumonia or sepsis as ALI risk factor, no. (%) | 143 (82) | 75 (88) | 68 (76) | 0.041 |

Baseline shock, no. (%) Baseline shock, no. (%) | 59 (34) | 25 (29) | 34 (38) | 0.221 |

Baseline PaO2/FiO2 Baseline PaO2/FiO2 | 161 (67) | 165 (70) | 157 (64) | 0.447 |

Baseline PaO2/FiO2 ratio ≤ 200, no. (%) Baseline PaO2/FiO2 ratio ≤ 200, no. (%) | 118 (69) | 57 (69) | 61 (70) | 0.839 |

APACHE III APACHE III | 85 (25) | 82 (24) | 87 (26) | 0.152 |

Duration of mechanical ventilation, d§ Duration of mechanical ventilation, d§ | 11.4 (9.9) | 12.3 (11) | 10.6 (8.7) | 0.249 |

Ever glucose < 60 mg/dl|| Ever glucose < 60 mg/dl|| | 29 (17) | 15 (18) | 14 (16) | 0.735 |

Mean daily minimum glucose, mg/dl|| Mean daily minimum glucose, mg/dl|| | 107 (23) | 105 (22) | 109 (25) | 0.234 |

Ever hospital dialysis Ever hospital dialysis | 28 (16) | 16 (19) | 12 (14) | 0.338 |

Any catecholamine use, no. (%) Any catecholamine use, no. (%) | 92 (54) | 48 (57) | 44 (51) | 0.389 |

Mean percentage of ICU days per patient Mean percentage of ICU days per patient | 17 (23) | 18 (22) | 16 (24) | 0.725 |

Any corticosteroids, no. (%) Any corticosteroids, no. (%) | 73 (43) | 39 (46) | 34 (39) | 0.331 |

Mean percentage of ICU days per patient Mean percentage of ICU days per patient | 25 (37) | 28 (38) | 22 (35) | 0.297 |

Any insulin, no. (%) Any insulin, no. (%) | 132 (77) | 60 (71) | 72 (83) | 0.078 |

Mean percentage of ICU days per patient Mean percentage of ICU days per patient | 55 (40) | 52 (42) | 58 (37) | 0.278 |

Any narcotics, no. (%) Any narcotics, no. (%) | 165 (97) | 80 (95) | 85 (98) | 0.438 |

Mean percentage of ICU days per patient Mean percentage of ICU days per patient | 69 (26) | 66 (29) | 72 (24) | 0.169 |

Any benzodiazepines, no. (%) Any benzodiazepines, no. (%) | 139 (81) | 70 (83) | 69 (79) | 0.500 |

Mean percentage of ICU days per patient Mean percentage of ICU days per patient | 48 (33) | 50 (33) | 46 (34) | 0.366 |

Any neuromuscular blocker, no. (%) Any neuromuscular blocker, no. (%) | 47 (28) | 26 (31) | 21 (24) | 0.318 |

Mean percentage of ICU days per patient Mean percentage of ICU days per patient | 5 (12) | 3 (7) | 6 (16) | 0.165 |

Ever comatose (RASS score < –3),¶,** no. (%) Ever comatose (RASS score < –3),¶,** no. (%) | 100 (57) | 52 (61) | 48 (54) | 0.585 |

Mean percentage of ICU days comatose per patient Mean percentage of ICU days comatose per patient | 18 (21) | 19 (21) | 16 (21) | 0.498 |

Ever delirious,¶,** no. (%) Ever delirious,¶,** no. (%) | 156 (90) | 77 (91) | 79 (89) | 0.903 |

Mean percentage of noncomatose ICU days in delirium per patient Mean percentage of noncomatose ICU days in delirium per patient | 54 (30) | 53 (30) | 54 (31) | 0.784 |

ICU length of stay ICU length of stay | 14.6 (11.6) | 15.8 (12.5) | 13.4 (10.6) | 0.179 |

Hospital length of stay Hospital length of stay | 21.5 (15.5) | 22.5 (16.2) | 20.6 (14.9) | 0.416 |

Definition of abbreviations: ALI = acute lung injury; APACHE III = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation III; FiO2 = fraction of inspired oxygen; ICU = intensive care unit; RASS = Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale.

Patient Outcomes at 6 and 12 Months

At 12 months, the mean (SD) 6MWT percent predicted value was 66% (25%), slightly higher than the 6-month mean (SD) value of 64% (22%) (P = 0.011 for difference between 6 and 12 mo). In general, the physical performance of survivors was lower than available predicted values at both 6 and 12 months, with improvement over time (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

SIX- AND TWELVE-MONTH PATIENT OUTCOMES*

| 6 Months (n = 163) | 12 Months (n = 149) | Difference (95% CI)† | P Value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical outcomes | | | | |

6-min-walk distance, % predicted 6-min-walk distance, % predicted | 64 (22) | 66 (25) | 4 (1, 7) | 0.011 |

4-m timed walk speed, m/s 4-m timed walk speed, m/s | 0.98 (0.32) | 1.02 (0.29) | 0.04 (0, 0.08) | 0.051 |

Manual Muscle Test score Manual Muscle Test score | 55.5 (4.6) | 56.0 (4.6) | 0.7 (0.2, 1.3) | 0.011 |

Manual Muscle Test score < 48, no. (%) Manual Muscle Test score < 48, no. (%) | 10 (7) | 6 (4) | −3 (–7, 2) | 0.220 |

Hand grip strength, % predicted Hand grip strength, % predicted | 76 (27) | 84 (27) | 8 (5, 11) | <0.001 |

Maximal inspiratory pressure, % predicted Maximal inspiratory pressure, % predicted | 88 (31) | 98 (32) | 8 (4, 13) | <0.001 |

FEV1, % predicted FEV1, % predicted | 77 (19) | 78 (19) | 1 (–1, 3) | 0.323 |

FVC, % predicted FVC, % predicted | 78 (19) | 81 (19) | 2 (0, 4) | 0.016 |

Body mass index, kg/m2 Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29.5 (7.7) | 29.5 (8.1) | 0.7 (0.2, 1.1) | 0.004 |

Arm fat area, % Arm fat area, % | 39.9 (11.3) | 39.3 (11.8) | −0.3 (–1.7, 1.0) | 0.648 |

Arm muscle area, % Arm muscle area, % | 50.0 (9.8) | 50.6 (10.4) | 0.6 (–0.7, 1.9) | 0.396 |

| Cognitive outcomes | | | | |

Cognitive impairment, no. (%) Cognitive impairment, no. (%) | 58 (36) | 37 (25) | −11 (–18, –5) | 0.001 |

COWA COWA | 31 (12) | 33 (13) | 2 (1, 4) | <0.001 |

COWA, ≤1.5 SDs, no. (%) COWA, ≤1.5 SDs, no. (%) | 51 (32) | 36 (24) | −8 (–15, –2) | 0.015 |

Digit Span Digit Span | 10.0 (2.9) | 10.0 (3.2) | −0.2 (–0.5, 0.1) | 0.282 |

Digit Span, ≤1.5 SDs, no. (%) Digit Span, ≤1.5 SDs, no. (%) | 8 (5) | 10 (7) | 1 (–3, 5) | 0.538 |

Hayling Sentence Completion Hayling Sentence Completion | 4.9 (1.8) | 5.3 (1.7) | 0.5 (0.3, 0.7) | <0.001 |

Hayling, ≤1.5 SDs, no. (%) Hayling, ≤1.5 SDs, no. (%) | 39 (24) | 21 (14) | −11 (–17, –5) | <0.001 |

Logical Memory I Logical Memory I | 8.8 (3.1) | 9.6 (3.4) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.3) | <0.001 |

Logical Memory I, ≤1.5 SDs, no. (%) Logical Memory I, ≤1.5 SDs, no. (%) | 28 (17) | 22 (15) | −2 (–8, 3) | 0.428 |

Logical Memory II Logical Memory II | 8.4 (2.9) | 9.2 (3.1) | 0.9 (0.5, 1.2) | <0.001 |

Logical Memory II, ≤1.5 SDs, no. (%) Logical Memory II, ≤1.5 SDs, no. (%) | 26 (16) | 17 (12) | −3 (–9, 2) | 0.218 |

Similarities Similarities | 9.6 (3.6) | 10.1 (3.4) | 0.6 (0.2, 0.9) | 0.002 |

Similarities, ≤1.5 SDs, no. (%) Similarities, ≤1.5 SDs, no. (%) | 25 (15) | 15 (10) | −5 (–9, 0) | 0.039 |

Definition of abbreviations: 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; COWA = Controlled Oral Word Association; MRC = Medical Research Council.

With respect to cognitive performance, at 12 months, 25% of survivors had cognitive impairment (primary outcome – as previously defined), with significant improvement from 36% at 6 months (P = 0.001). At 12 months, patients demonstrated impairments (i.e., ≥1.5 SDs below population norms) in executive function (14% based on Hayling Sentence Completion test), language (24% based on COWA), immediate and delayed memory (15 and 12% based on Logical Memory I and II tests, respectively), verbal reasoning and concept formation (10% based on Similarities test), and attention and working memory (7% based on Digit Span test). These scores of ≥1.5 SDs below the population norms occur in less than 6.7% of the normal population and represent moderate to severe impairments. In all tests, except Digit Span, there was significant improvement in mean scores between 6 and 12 months.

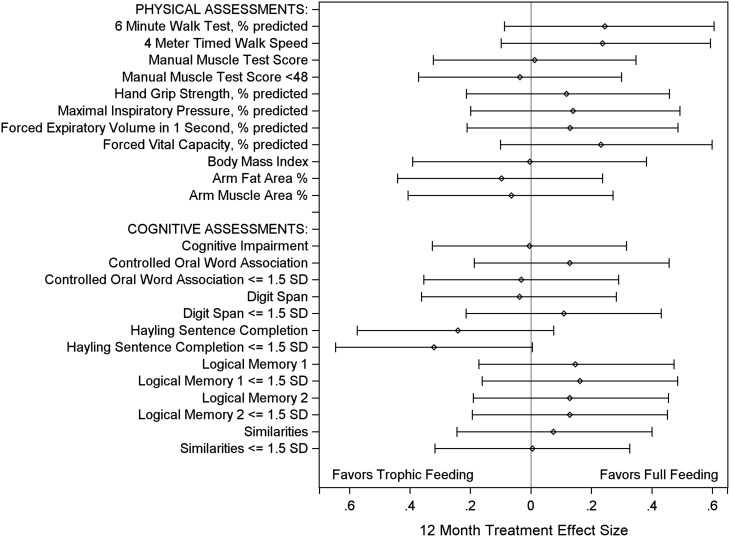

Initial Trophic versus Full Feeding

At 12 months, when comparing the initial trophic versus full feeding patient groups, there was no significant difference in the average (SD) percent predicted 6MWT values (63% [25%] vs. 70% [24%]; P = 0.136), and in the proportion of patients with cognitive impairment (29 vs. 20%; P = 0.311) (Table 3 and Figure 2). These results did not substantially change after adjusting for the covariates with potentially important differences between the treatment groups, as outlined previously. Specifically, the unadjusted versus adjusted treatment effect (95% confidence interval) of initial trophic feeding compared with full feeding for the percent predicted 6MWT outcome was –6.0% (–14.0 to 2.0; P = 0.136) versus –2.3% (–10.0 to 5.3; P = 0.551), respectively, and the unadjusted versus adjusted odds ratio for the cognitive impairment outcome was 1.45 (0.71, 3.00; P = 0.311) versus 1.50 (0.61, 3.67; P = 0.375), respectively.

TABLE 3.

TWELVE-MONTH RESULTS BY TREATMENT GROUP*

| Trophic Feeding (n = 75) | Full Feeding (n = 74) | Treatment Effect (95% CI)† | P Value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical outcomes | | | | |

6-min-walk distance, % predicted 6-min-walk distance, % predicted | 63 (25) | 70 (24) | −6 (–14, 2) | 0.136 |

4-m timed walk speed, m/s 4-m timed walk speed, m/s | 0.98 (0.29) | 1.08 (0.29) | −0.07 (–0.16, 0.02) | 0.125 |

Manual Muscle Test score Manual Muscle Test score | 55.9 (4.0) | 56.2 (5.2) | −0.1 (–1.6, 1.4) | 0.901 |

Manual Muscle Test score < 48, no. (%) Manual Muscle Test score < 48, no. (%) | 3 (4) | 3 (5) | 0.84 (0.16, 4.39) | 0.833 |

Hand grip strength, % predicted Hand grip strength, % predicted | 82 (27) | 85 (26) | −3 (–12, 5) | 0.462 |

Maximal inspiratory pressure, % predicted Maximal inspiratory pressure, % predicted | 97 (33) | 99 (31) | −4 (–15, 6) | 0.421 |

FEV1, % predicted FEV1, % predicted | 77 (19) | 80 (19) | −2 (–9, 4) | 0.424 |

FVC, % predicted FVC, % predicted | 78 (18) | 83 (19) | −4 (–10, 1) | 0.144 |

Body mass index, kg/m2 Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29.5 (7.2) | 29.6 (9.1) | 0.0 (–2.9, 2.8) | 0.985 |

Arm fat area, % Arm fat area, % | 38.9 (12.1) | 39.7 (11.5) | −1.2 (–4.9, 2.6) | 0.550 |

Arm muscle area, % Arm muscle area, % | 50.8 (10.7) | 50.4 (10.0) | 0.7 (–2.7, 4) | 0.703 |

| Cognitive outcomes | | | | |

Cognitive impairment, no. (%) Cognitive impairment, no. (%) | 22 (29) | 15 (20) | 1.45 (0.71, 3) | 0.311 |

COWA COWA | 32 (13) | 34 (13) | −2 (–6, 2) | 0.431 |

COWA, ≤1.5 SDs, no. (%) COWA, ≤1.5 SDs, no. (%) | 18 (24) | 18 (24) | 0.93 (0.44, 1.95) | 0.843 |

Digit Span Digit Span | 9.8 (3.2) | 9.9 (3.1) | 0.1 (–0.8, 1.1) | 0.800 |

Digit Span, ≤1.5 SDs, no. (%) Digit Span, ≤1.5 SDs, no. (%) | 6 (8) | 4 (5) | 1.57 (0.41, 6.06) | 0.512 |

Hayling Sentence Completion Hayling Sentence Completion | 5.5 (1.6) | 5.2 (1.8) | 0.4 (–0.1, 1.0) | 0.119 |

Hayling, ≤1.5 SDs, no. (%) Hayling, ≤1.5 SDs, no. (%) | 7 (10) | 14 (19) | 0.38 (0.14, 1.03) | 0.058 |

Logical Memory I Logical Memory I | 9.3 (3.4) | 9.9 (3.4) | −0.5 (–1.5, 0.6) | 0.379 |

Logical Memory I, ≤1.5 SDs, no. (%) Logical Memory I, ≤1.5 SDs, no. (%) | 13 (18) | 9 (12) | 1.58 (0.65, 3.85) | 0.316 |

Logical Memory II Logical Memory II | 9.0 (3.0) | 9.4 (3.2) | −0.4 (–1.4, 0.6) | 0.443 |

Logical Memory II, ≤1.5 SDs, no. (%) Logical Memory II, ≤1.5 SDs, no. (%) | 10 (14) | 7 (10) | 1.49 (0.56, 3.92) | 0.423 |

Similarities Similarities | 9.8 (3.3) | 10.5 (3.4) | −0.2 (–1.3, 0.8) | 0.648 |

Similarities, ≤1.5 SDs, no. (%) Similarities, ≤1.5 SDs, no. (%) | 8 (11) | 7 (10) | 1.02 (0.36, 2.83) | 0.976 |

Definition of abbreviations: 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; COWA = Controlled Oral Word Association; FVC = forced vital capacity.

Effect size of treatment intervention at 12 months. The treatment effect, presented as an effect size, with 95% confidence interval, for the primary outcomes (6-min-walk test % predicted, and cognitive impairment) and all secondary outcomes. Effect size was calculated as the treatment effect (Table 3, difference in means or proportions) divided by the pooled SD from the initial trophic and full feeding groups (77, 78).

In comparing treatment effects at 6 versus 12 months, for 21 of 24 (92%) of the physical and cognitive performance tests, there was no significant difference in effect, with the only significant differences being for the 4-m walk speed (0.03 [–0.07, 0.13] vs. –0.07 [–0.16, 0.02], P = 0.010, for initial trophic vs. full feeding) and for the evaluation of executive function using the Hayling Sentence Completion continuous scaled score (–0.26 [–0.82, 0.30] vs. 0.42 [–0.11, 0.95]; P = 0.004) and proportion of patients more than 1.5 SDs below norms (1.35 [0.67, 2.73] vs. 0.38 [0.14, 1.03]; P = 0.005). There was no interaction between the OMEGA randomized assignment and initial trophic versus full feeding. Moreover, none of the secondary physical and cognitive performance tests showed any significant difference between initial trophic versus full feeding groups, and there were no significant differences in the a priori sensitivity analysis, subgroup analyses, and statistical interactions.

Discussion

In this 1-year, multisite follow-up study of 174 patients with ALI from the EDEN trial, survivors performed below predicted values across a comprehensive battery of physical and cognitive performance assessments with some improvements observed between 6 and 12 months, particularly for the cognitive performance. Initial trophic versus full feeding, for up to the first 6 days of mechanical ventilation after randomization, had no significant effect on any physical or cognitive performance measure at 6 or 12 months.

The results of this study of performance-based outcomes for 174 survivors from 5 EDEN study centers are consistent with the patient-reported outcomes evaluated via telephone survey for 525 survivors from 11 of 12 EDEN study centers (2). In this prior publication, EDEN trial survivors reported physical function lower than population norms (mean values of 62 and 67% of age- and sex-matched norms for SF-36 Physical Function domain at 6 and 12 mo), similar to 6MWT performance measured in the present study (mean percent predicted values of 64 and 66%, respectively). Using the telephone version of the Mini Mental State Exam (a global cognitive screening tool) (53), the prior publication demonstrated that 25 and 21% of EDEN survivors had cognitive impairment at 6 and 12 months, respectively, compared with 36 and 25% in this study that used a more sensitive and comprehensive battery of performance-based cognitive tests. Similarly, initial trophic feeding versus full enteral feeding did not affect any of the patient-reported outcomes (2). Because the association between patient-reported outcomes and performance-based assessments is unclear (4), consistency between this study’s in-person performance-based assessments and the previously reported telephone-based, patient-reported outcomes helps solidify our understanding of the longer-term effects of initial trophic versus full enteral feeding strategies. In addition, this study makes important contributions through evaluating anthropometrics, muscle strength, and physical function, which specifically may be affected by the limited protein and total caloric intake in the initial trophic feeding group (7–11, 54).

Consistent with the findings of mainly single-center prior studies of ALI survivors (7, 11, 38, 55–58), this multicenter study demonstrated impairments across multiple aspects of physical and cognitive performance. The mean percent predicted 6MWT in this study, with patient enrollment from 2008 to 2011, was about 30% below predicted, similar to a single-center observational study from Toronto, Canada in 81 patients with ARDS (enrolled 1998–2002) completing the 6MWT (7). Percent predicted values for FVC and FEV1 were consistent with prior studies recruiting patients from Canada and the United States (enrolled 1999–2000) (7, 59). Moreover, a single-center observational study of 74 ALI survivors from Utah (enrolled 1994–1998) reported similar mean scores at 1-year follow-up for the Similarities, Digit Span, and COWA cognitive tests, evaluating verbal reasoning/concept formation, attention/working memory, and language, respectively (55, 60). Last, survivors from the prior multicenter ARDS Network FACTT (Fluid and Catheter Treatment Trial) study (enrolled 2000–2005) also showed similar impairments in the Similarities, Logical Memory I, and COWA cognitive tests, at 1-year follow-up (58). Important differences between this study and these prior ALI studies (7, 11, 38, 55) are that patients in the present study were enrolled about 10 years more recently and that all patients received low tidal volume ventilation and fluid-conservative therapy as part of the EDEN study protocol; hence, results of this study reflect more current ICU practice for these patients with ALI. Fluid-conservative therapy was found to be a potential risk factor for long-term cognitive impairment (58), which may have affected our study findings; however, this prior study was limited by significant loss to follow-up and the inability to adjust for potential covariates. Despite advances in ALI management over the past two decades, ALI survivors still experience significant impairment 1 year after ALI.

In evaluating physical and cognitive performance in this study, when possible, comparison was made with matched normal values because the baseline status of individual patients cannot be measured before ALI onset. This issue raises the possibility that these impairments existed before ALI; however, the patient group evaluated was relatively young and functional at baseline (mean age of 47 yr without any known cognitive impairment, and 93% were living independently without assistance) (2). Moreover, large cohort studies, with prospective measurement of pre-ICU status, have demonstrated important, new post-ICU impairments in physical, psychological, and cognitive outcomes (61–65). Finally, the incidence and magnitude of these impairments are supported by the high rate of rehabilitation use and/or new institutionalization (56% of survivors), and inability to return to work after ALI (48% without return to work at 12 mo), as previously reported in the telephone-based follow-up study of 525 EDEN survivors (2).

Initial trophic versus full enteral feeding did not have any significant effect on a wide spectrum of physical and cognitive performance–based outcome measures despite the fact that differences in total calories and protein received by the two study groups were considered large enough to potentially effect differences in longer-term outcomes (5, 66). There is little clinical research and no prior randomized studies evaluating the long-term outcomes of ICU nutritional strategies, which limits our ability to confidently explain why there was no treatment effect observed in this study. Importantly, approximately half of patients in the initial trophic feeding group eventually received full feeding after the initial 6-day period, as per the EDEN protocol (1); hence, the overall duration of difference in feeding strategies may not have been long enough to cause differences in patient performance. Alternatively, any effect of the nutritional strategies may have only lasted for a shorter time period relative to the initial 6-month follow-up assessment in this study. However, there was no difference between groups in the need for new residence in a health care facility at 90 days (2), or in other, shorter-term outcomes (e.g., mortality, ventilator-free days, organ failure–free days), with consistent results observed across patient subgroups (1). Hence, our findings of no differences in 6- and 12-month physical and cognitive performance are novel and important in the evaluation of ICU nutritional strategies.

Caution must be taken in interpreting these results because there are still limitations in the mechanistic understanding of anabolism and catabolism during critical illness and their potential for effects on muscle and long-term functional outcomes given the many unmeasured factors that affect patients’ trajectory of recovery over time (67, 68) It is well known that early critical illness is marked by systemic inflammation and activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary axis, leading to rapid catabolism in which muscles are sacrificed as a source of amino acids (69). Muscles rapidly change in the early days of critical illness, with evidence of atrophy via autophagy and proteasomal degradation (70, 71), decreased force generation (72), and myopathic changes such as myosin loss and membrane inexcitability (68, 73, 74). It is unclear whether nutrition delivered during this highly acute phase of critical illness can alter these processes in a beneficial way, or whether there may be untoward effects of providing nutrition during such a catabolic state.

Strengths of this study include use of a detailed battery of performance-based physical and cognitive tests at 6- and 12-month follow-up for a relatively large number of patients with ALI recruited from 12 hospitals at 5 study centers across the United States. This study also has several potential limitations. First, the EDEN study enrolled relatively younger, overweight patients, and explicitly excluded underweight patients, who primarily had pneumonia or nonpulmonary sepsis. Hence, results of this study may not be generalizable to other ICU patients. Second, the EDEN trial had an open-label design; however, the outcomes assessors of this ancillary study were blinded to treatment assignments to minimize bias in outcome assessment. Third, there is potential bias in the understanding of the effects of initial trophic versus full feeding because physical and cognitive performance can be assessed only in survivors (75). However, the EDEN study treatment allocation did not affect either short- or longer-term mortality, thus minimizing this potential bias on these analyses. Fourth, this study did not measure physical and cognitive performance at hospital discharge given its focus on longer-term outcomes the ICU-based feeding strategies. Finally, the sample size of this study may have been underpowered to exclude clinically important differences between groups and to test for statistical interactions. However, compared with prior publications evaluating longer-term physical and cognitive performance of ALI survivors, this study is large. Nonetheless, future ALI trials should continue to evaluate longer-term outcomes using even larger sample sizes (76).

In conclusion, this multicenter study of patients with ALI demonstrated that survivors performed below predicted values across a comprehensive battery of physical and cognitive performance tests with some improvements observed between 6 and 12 months, particularly in cognitive performance. Initial trophic versus full feeding strategies, during the first 6 days of mechanical ventilation after randomization, had no effect on physical or cognitive performance at 6 or 12 months. Evaluation of other novel interventions is needed to reduce the frequent 6- and 12-month impairments in physical and cognitive performance experienced by ALI survivors.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank all patients and their proxies who participated in the study. The authors acknowledge our dedicated research staff, including the following who assisted with data collection, training/quality assurance, and/or data management: Lindsay Anderson, Ellen Caldwell, Nancy Ciesla, William Flickinger, Jacqueline Flynn, Stephanie Gundel, John Keenan, Christopher Mayhew, Melissa McCullough, Jessica McCurley, Mardee Merrill, Laura Methvin, Kristin Sepulveda, and Kelly Swanson.

Investigators and research staff from NHLBI ARDS Network sites that participated in this follow-up study: University of Washington, Harborview (L. Hudson, M. Neff, K. Sims, A. Ungar, T. Watkins); Johns Hopkins University (R. Brower, H. Fessler, D. Hager, K. Oakjones); Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center (J. Sevransky, A. Workneh); University of Maryland (C. Shanholtz, D. Herr, H. Howes, G. Netzer, P. Rock, A. Sampaio, J. Titus); Union Memorial Hospital (P. Sloane, T. Beck, D. Highfield, S. King); Washington Hospital Center (B. Lee, N. Bolouri); Vanderbilt University (A. P. Wheeler, G. R. Bernard, M. Hays, S. Mogan); Wake Forest University (R. D. Hite, K. Bender, A. Harvey, Mary Ragusky); LDS Hospital and Intermountain Medical Center (A. Morris, A. Austin, S. Barney, S. Brown, J. Fergeson, H. Gallo, T. Graydon, C. Grissom, E. Hirshberg, A. Jephson, N. Kumar, R. Miller, D. Murphy, J. Orme, A. Stow, L. Struck, F. Thomas, D. Ward, L. Weaver); LDS Hospital (P. Bailey, W. Beninati, L. Bezdijan, T. Clemmer, S. Rimkus, R. Tanaka); McKay Dee Hospital (C. Lawton, D. Hanselman); Utah Valley Regional Medical Center (K. Sundar, W. Alward, C. Bishop, D. Eckley, T. Hill, B. Jensen, K. Ludwig, D. Nielsen, M. Pearce). Clinical Coordinating Center: Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School (D. Schoenfeld, M. Guha, E. Hammond, N. Lavery, P. Lazar, R. Morse, C. Oldmixon, N. Ringwood, E. Smoot, B. T. Thompson, R. Wilson). National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute: A. Harabin, S. Bredow, M. Waclawiw, G. Weinmann. Data and Safety Monitoring Board: R. G. Spragg (chair), A. Slutsky, M. Levy, B. Markovitz, E. Petkova, C. Weijer. Protocol Review Committee: J. Sznajder (chair), M. Begg, E. Israel, J. Lewis, S. McClave, P. Parsons.

Footnotes

Supported by the NHLBI, which funded this follow-up study (R01HL091760, R01HL091760-02S1, and R01HL096504), the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR) (UL1 TR 000424-06), and the EDEN trial (contracts for sites participating in this study: HHSN268200536170C, HHSN268200536171C, HHSN268200536173, HHSN268200536174C, HHSN268200536175C, and HHSN268200536179C).

Author Contributions: D.M.N., V.D.D., P.E.M., C.L.H., E.W.E., and R.O.H. contributed to the conception and design of this study. D.M.N., V.D.D., P.E.M., C.L.H., J.C.J., and R.O.H. contributed to the acquisition of data. All authors contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data. D.M.N. and V.D.D. drafted the manuscript, and all authors critically revised it for important intellectual content and approved the final version to be submitted.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201304-0651OC on June 27, 2013

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

Articles from American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine are provided here courtesy of American Thoracic Society

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201304-0651oc

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc3827703?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

Nutritional therapy for the prevention of post-intensive care syndrome.

J Intensive Care, 12(1):29, 29 Jul 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39075627 | PMCID: PMC11285132

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Impact of withholding early parenteral nutrition on 2-year mortality and functional outcome in critically ill adults.

Intensive Care Med, 50(10):1593-1602, 17 Jul 2024

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 39017697

Tackling Brain and Muscle Dysfunction in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Survivors: NHLBI Workshop Report.

Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 209(11):1304-1313, 01 Jun 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38477657

Nutrition in the intensive care unit: from the acute phase to beyond.

Intensive Care Med, 50(7):1035-1048, 21 May 2024

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 38771368 | PMCID: PMC11245425

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Deep Machine Learning Might Aid in Combating Intensive Care Unit-Acquired Weakness.

Cureus, 16(4):e58963, 24 Apr 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38800279 | PMCID: PMC11126887

Go to all (144) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

One year outcomes in patients with acute lung injury randomised to initial trophic or full enteral feeding: prospective follow-up of EDEN randomised trial.

BMJ, 346:f1532, 19 Mar 2013

Cited by: 150 articles | PMID: 23512759 | PMCID: PMC3601941

Initial trophic vs full enteral feeding in patients with acute lung injury: the EDEN randomized trial.

JAMA, 307(8):795-803, 05 Feb 2012

Cited by: 417 articles | PMID: 22307571 | PMCID: PMC3743415

Randomized trial of initial trophic versus full-energy enteral nutrition in mechanically ventilated patients with acute respiratory failure.

Crit Care Med, 39(5):967-974, 01 May 2011

Cited by: 144 articles | PMID: 21242788 | PMCID: PMC3102124

Trophic feedings for parenterally fed infants.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev, (3):CD000504, 20 Jul 2005

Cited by: 26 articles | PMID: 16034854

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NCATS NIH HHS (2)

Grant ID: UL1 TR000424

Grant ID: UL1 TR 000424-06

NHLBI NIH HHS (6)

Grant ID: R01 HL091760

Grant ID: R34 HL105869

Grant ID: R01HL096504

Grant ID: R01HL091760-02S1

Grant ID: R01HL091760

Grant ID: R01 HL096504

1,2,3

1,2,3