Abstract

Free full text

Perivascular macrophages mediate neutrophil recruitment during bacterial skin infection

Associated Data

Abstract

Transendothelial migration of neutrophils in post-capillary venules is a key event in the inflammatory response against pathogens and tissue damage. The precise regulation of this process is incompletely understood. We report that perivascular macrophages are critical for neutrophil migration into skin infected with the pathogen Staphylococcus aureus. Using multiphoton intravital microscopy we show that neutrophils extravasate from inflamed dermal venules in close proximity to perivascular macrophages, which are a major source of neutrophil chemoattractants. The virulence factor alpha-hemolysin lyses perivascular macrophages leading to decreased neutrophil transmigration. Our data illustrate a previously unrecognized role for perivascular macrophages in neutrophil recruitment to inflamed skin, and indicate that Staphylococcus aureus uses hemolysin-dependent killing of these cells as an immune evasion strategy.

Introduction

Neutrophils, through their ability to be rapidly recruited to tissues and deploy a diverse array of antimicrobial effector mechanisms, are essential for the clearance of many bacterial pathogens1. Given the potentially logarithmic growth of microorganisms during early stages of infection, effective destruction of pathogens depends upon the timely coordination of a complex series of cellular and molecular processes within the host. This commences with immune ‘sensing’ of pathogens by tissue-resident cells followed by activation of the vascular endothelium and neutrophil extravasation from the bloodstream, and finally initiation of neutrophil antimicrobial functions1, 2.

The current paradigm of neutrophil recruitment is described by a well-defined series of steps that occur within post-capillary venules1, 3. The first of these is tethering and rolling on the vascular endothelium, which is mediated by P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) or VLA-4 (very late antigen-4/CD49d/CD29) on the neutrophil and E- and P-selectin or VCAM-1 (vascular cell adhesion molecule) on the endothelium4. Under the influence of Gα-coupled chemokine receptor-mediated signaling, conformational changes in the β2 integrins LFA-1 and Mac-1 occur on rolling cells, resulting in increased integrin affinity for their endothelial ligands5. Subsequent to adhesion, neutrophils crawl along the intraluminal surface of the vessel in a Mac-1 dependent manner to reach a preferred site of transendothelial migration (TEM), which in some cases may be through the endothelial cell itself (transcellular pathway) but typically occurs between endothelial cell junctions (paracellular pathway)6, 7.

Although the sequential model of leukocyte recruitment is well supported by many studies, recent findings have suggested that additional mechanisms coordinate this process, particularly in the perivascular space. Immediately following migration through the endothelial layer, neutrophils enter a space between endothelial cells and surrounding pericytes. Once there, they migrate along pericyte processes in a Mac-1/LFA-1/ICAM-1 dependent manner to reach optimal sites of exit from the pericyte layer8. In addition to pericytes, immune cell subpopulations, particularly macrophages9–11, are associated with post-capillary venules. Based on their expression of a range of pattern recognition receptors and ability to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, tissue-resident macrophages have been argued to participate in the induction of inflammation12. Nevertheless, the precise role of macrophages, in particular the perivascular subset, on neutrophil recruitment during tissue inflammation, if any, is unclear.

Of the human pathogens that require neutrophils for control and clearance, infections with Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) are particularly prevalent, resulting in an estimated 1.3 million infections and 390,000 hospital admissions per year in the US alone13, 14. In addition, the widespread emergence of nosocomial and community-acquired methicillin-resistant (CA-MRSA) strains represents a major health problem, and it is estimated that the mortality due to MRSA infections is comparable to the combined total of AIDS, tuberculosis and viral hepatitis15. The fact that most systemic sequelae caused by S. aureus originate from skin infections necessitates an in-depth understanding of the cutaneous anti-bacterial immune response.

A key virulence strategy used by many pathogens is to subvert effective immune responses. The pathogenicity of S. aureus is due, in large part, to a diverse array of virulence factors that strains may produce. Foremost amongst these is a range of cytotoxins that includes α-hemolysin (Hla), Panton Valentine Leukocidin and Phenol Soluble Modulins16. The secreted pore-forming cytolysin Hla, which is produced by virtually all clinical isolates, has been implicated in the pathogenesis of necrotising pneumonia and skin infections17–20. Hla binds to the membrane-associated protease A Disintegrin and Metallopeptidase 10 (ADAM10), which has been shown to facilitate Hla-mediated disruption of epithelial integrity19–21. However, whether and how Hla interferes with the ensuing innate immune response is incompletely understood.

Given that the precise cellular and molecular events that take place during early infection with S. aureus are ill-defined, we utilized our well-characterized intravital skin imaging model22 in combination with fluorescently-tagged bacterial strains to dissect the orchestration of the cutaneous anti-bacterial immune response. We further made use of an isogenic deletional bacterial mutant that lacks functional Hla (ΔHla) to determine the actions of this essential virulence factor within the context of an intact microenvironment in vivo. When compared with wild-type (WT) S. aureus, infection with ΔHla S. aureus led to increased neutrophil recruitment, decreased bacterial load and protection from tissue necrosis. Strikingly, in ΔHla S. aureus-infected animals, neutrophils were found to preferentially extravasate from “hotspots” that were in close physical proximity to perivascular macrophages (PVM), which were the dominant source of neutrophil-attracting chemokines. In contrast, during infection with WT S. aureus, neutrophils failed to arrest on the inflamed endothelium and subsequently transmigrate, and this was associated with rapid, specific Hla-dependent lysis of PVM. Our studies reveal the thus far unknown guidance of blood-borne leukocytes during extravasation by perivascular hematopoietic cells and provide novel insight into the mechanisms of bacterial immunoevasion.

Results

Hla interferes with neutrophil accumulation during cutaneous S. aureus infection

While neutrophils are required for the control and clearance of bacterial infections, the mechanisms that regulate their homing from the bloodstream and subsequent interstitial migration at sites of bacterial barrier breach are incompletely understood. We have previously established the ear skin in mice as an ideal site for dissecting anti-pathogen responses, as resident immune cells are well defined and the ear is readily accessible for intravital imaging22.

We initially compared the capacity of various bacteria to cause neutrophil influx into ear skin in order to assess potential strain-specific differences in this essential step of the immune response. We found that neutrophil numbers in skin infected with the commensal S. epidermidis and E. coli were significantly higher than that of WT S. aureus (Fig. 1a). Since the virulence factor Hla has been implicated in the pathogenesis of cutaneous S. aureus infections, we determined neutrophil numbers following injection with S. aureus DU1090, which is an isogenic Hla-deficient strain (ΔHla). Remarkably, this resulted in neutrophil numbers similar to S. epidermidis and E. coli (Fig. 1a), indicating that Hla impacts on the accumulation of neutrophils in infected skin. Macroscopically, ears infected with ΔHla S. aureus showed more pronounced signs of inflammation as indicated by increased redness and ear thickness as compared to WT bacteria (Fig. 1b; Suppl. Fig. 1a). Furthermore, an increased number of red blood cells (RBC) was observed in the absence of Hla, consistent with the hemolytic activity of this virulence factor (Suppl. Fig. 1b). Co-injection of ΔHla S. aureus with purified Hla phenocopied infection with WT S. aureus (Suppl. Fig. 1c&d). Strikingly, over the course of several days, infection with WT S. aureus culminated in necrosis, while infection with ΔHla S. aureus ultimately resulted in complete reconstitution of tissue integrity (Fig. 1b).

(a) Flow cytometry analysis of neutrophil influx in infected ears with indicated bacteria at 12h p.i. n=4 mice/group. (b) Clinical manifestations, and (c) neutrophil influx of ears infected with WT S. aureus, ΔHla S. aureus or after PBS injection at various timepoints mentioned in the figure. n=3 mice/group for PBS injected at each time point and for all groups at 48 hours; n=4 mice/group for WT & ΔHla S. aureus groups at 4h and 8h p.i.; n=5 mice/group for WT & ΔHla at 12h p.i.; n=6 mice/group WT & ΔHla at 24h p.i. (d) Myeloperoxidase activity in ear skin of mice either sham infected (PBS; n=3 mice/group) or infected with WT or ΔHla S. aureus at 4h (n=5 mice/group) and 12h (n=6 mice/group) p.i. A single outlier sample from the 12hr PBS group was excluded from analysis using the ROUT method. (e) Representative haematoxylin and eosin stained ear sections obtained from mice infected with PBS (n=3 mice/group), WT or ΔHla S. aureus at 6h p.i. (n=6 mice/group). (f) Neutrophil influx in ears of mice at 12h p.i. with concomitant injection of ΔHla S. aureus and purified Hla (n=4 mice/group). (g) Neutrophil influx in ears at 12h p.i. with WT S. aureus in mice pretreated with control serum or anti-Hla serum (n=4 mice/group). (h) Bacterial load (CFUs) of infected ears at indicated time points (n=4 mice/group). Bars represent mean±SD. All data are representative of at least 2 independent experiments except for (e), which is from a single experiment. Statistical analysis was performed on log-transformed data as follows: (a and f) one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test; (c, d and h) two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni test; (g) Student’s two-tailed unpaired t-test was used to determine the P-value. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001; n.s, not significant.

To better understand these divergent outcomes, we conducted a detailed analysis of neutrophil influx into the skin during S. aureus infection. While no difference was observed at 4h post-infection (p.i.), significantly higher numbers of neutrophils accumulated in ΔHla S. aureus infected skin at 8h, 12h, 24h and 48h p.i. (Fig. 1c). These changes in absolute neutrophil number were corroborated by myeloperoxidase assays (Fig. 1d) and histopathology, which revealed increased ear thickness and large numbers of neutrophils in the dermis of mice infected with ΔHla S. aureus (Fig. 1e). Neutrophil recruitment was impeded when ΔHla S. aureus injection was combined with purified Hla (Fig. 1f). Treatment of WT S. aureus infected mice with Hla antiserum resulted in increased neutrophil numbers in the skin (Fig. 1g), while the antiserum had no effect in ΔHla S. aureus-infected mice (data not shown). These additional controls demonstrate that the phenotypic difference observed with ΔHla S. aureus was indeed due to the absence of Hla in the bacterium rather than some unrecognized changes mediated by genetic manipulation. To extend this finding beyond the ear infection model, we confirmed the influence of Hla on neutrophil influx following S. aureus infection in another commonly used infection site, i.e. the back skin (Suppl. Fig. 1e). Moreover, treatment of mice with Hla anti-serum augmented neutrophil influx following infection with the clinical isolate USA300, which is the dominant strain causing skin infections in the United States, and which produces high levels of Hla16 (Suppl. Fig. 1f), suggesting that the neutrophil recruitment defect in the presence of Hla is clinically relevant. Finally, the observed decrease in neutrophil influx in WT S. aureus was mirrored by increased bacterial survival (Fig. 1h). Together, these data indicate that Hla interferes with the presence of neutrophils in the skin following infection, and that these effects occur independently of other S. aureus-specific factors.

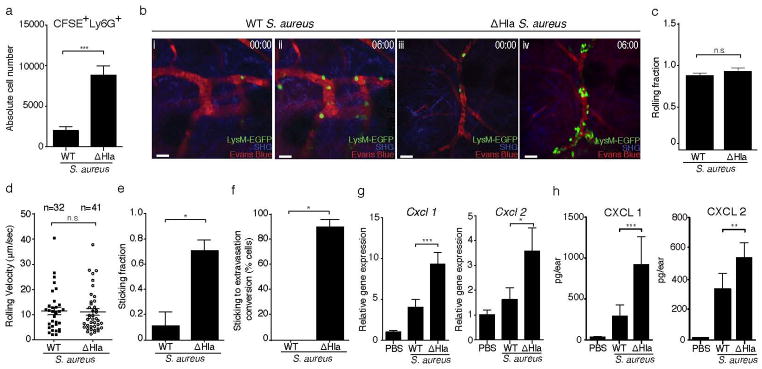

Neutrophil homing to S. aureus infected skin is reduced in the presence of Hla

We hypothesized that the reduced numbers of neutrophils in WT S. aureus infected skin were related to their impaired homing into the dermis. Indeed, short-term homing of CFSE-labeled bone marrow cells revealed significantly increased accumulation of neutrophils in ΔHla as compared to WT S. aureus infected skin (Fig. 2a). To obtain insight into the mechanism underlying this phenomenon, we performed intravital multi-photon microscopy of infected ears following adoptive transfer of bone marrow cells (2×107) from LysMgfp/+ mice23 (Fig. 2b; Suppl. Movie 1 and data not shown). Donor neutrophil rolling fractions were identical in WT and ΔHla S. aureus infected skin (Fig. 2c), indicating that the integrity of the venular endothelium was maintained under both conditions. Similarly, no difference was found in rolling velocities, demonstrating that the expression of adhesion molecules on endothelial cells were the same (Fig. 2d). In contrast, neutrophil sticking fractions were markedly reduced during WT S. aureus infection (Fig. 2e), and of those cells that managed to adhere, significantly fewer cells extravasated in response to WT S. aureus infection during the imaging period (Fig. 2f, Suppl. Movie 1, time frame 5:30–7:20 min). Confocal imaging of infected tissue 1h post adoptive transfer of LysM-EGFP bone marrow cells revealed a large number of GFP+ neutrophils to be present in the interstitium of ΔHla S. aureus-infected ear skin, with only a few cells present in WT S. aureus-infected tissue (Suppl. Fig. 2a). Flow cytometric analysis of ΔHla S. aureus infected tissue confirmed that the vast majority (97.3%) of GFP+ cells were Ly6G+Ly6Cint neutrophils. Only 0.8% GFP+ cells represented Ly6G−Ly6Chi monocytes (Suppl. Fig. 2b). Together, these data suggest a major defect in the capability of neutrophil transmigration in WT S. aureus infected skin.

(a) Numbers of CFSE+Ly6G+ neutrophils at 12h p.i., determined by flow cytometry, in WT and ΔHla S. aureus infected ears. CFSE-labeled bone marrow cells were transferred at 10h p.i. Bars represent mean±SD; n=3 mice/group. (b) Intravital multi-photon microscopy showing the increased adhesion and extravasation of adoptively transferred LysM-EGFP+ neutrophils in ΔHla S. aureus (iii,iv) as compared to WT S. aureus (i,ii) infected ear dermis. 00:00, min:sec. SHG, Second harmonic generation. Scale bar, 30μm. Neutrophil rolling fractions (c), mean rolling velocities (d) and sticking fractions (e) in dermal blood vessels of mice infected with WT S. aureus or ΔHla S. aureus. (f) Conversion of neutrophil sticking to extravasation in the blood vessels of mice infected with WT S. aureus or ΔHla S. aureus. n, number of events analyzed per group (cumulative from 3 mice/group). Imaging data shown in (b–f) were from one out of two experiments with n=3 mice/group each. More than 10 vessels of diameters ranging between 10–30μm were included in these analyses for each treatment group. Bars represent mean±SEM. (g) Relative Cxcl1 and Cxcl2 mRNA levels as determined by RT-qPCR (PBS: n=3 mice/group; WT and ΔHla S. aureus: n=5 mice/group; mean±SD) and (h) protein levels in mice injected with PBS (n=4) WT S. aureus (n=7) or ΔHla S. aureus (n=8). Bars represent mean±SD. Neutrophil numbers (a) were analyzed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test on log-transformed data. Imaging data were analyzed using either a two-tailed (c and d) or one-tailed (e and f) Mann-Whitney U test. Chemokine data (g and h) were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s post-test following log transformation. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. n.s., not significant. Unless otherwise stated data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

Since the conversion of rolling to firm adherence requires chemokine-mediated integrin activation5, 24, we assessed the production of proinflammatory mediators and chemokines in infected skin. mRNA and protein levels of CXCL1 (KC) and CXCL2 (MIP2), the major chemokines implicated in neutrophil homing, were reduced during WT S. aureus infection compared to ΔHla S. aureus infection (Fig. 2g and h), as were CCL2 (MCP-1), CCL3 (MIP-1α) and CCL4 (MIP-1β) (Suppl. Fig. 2c). These data suggested that critical neutrophil chemoattractants were reduced in WT S. aureus-infected skin.

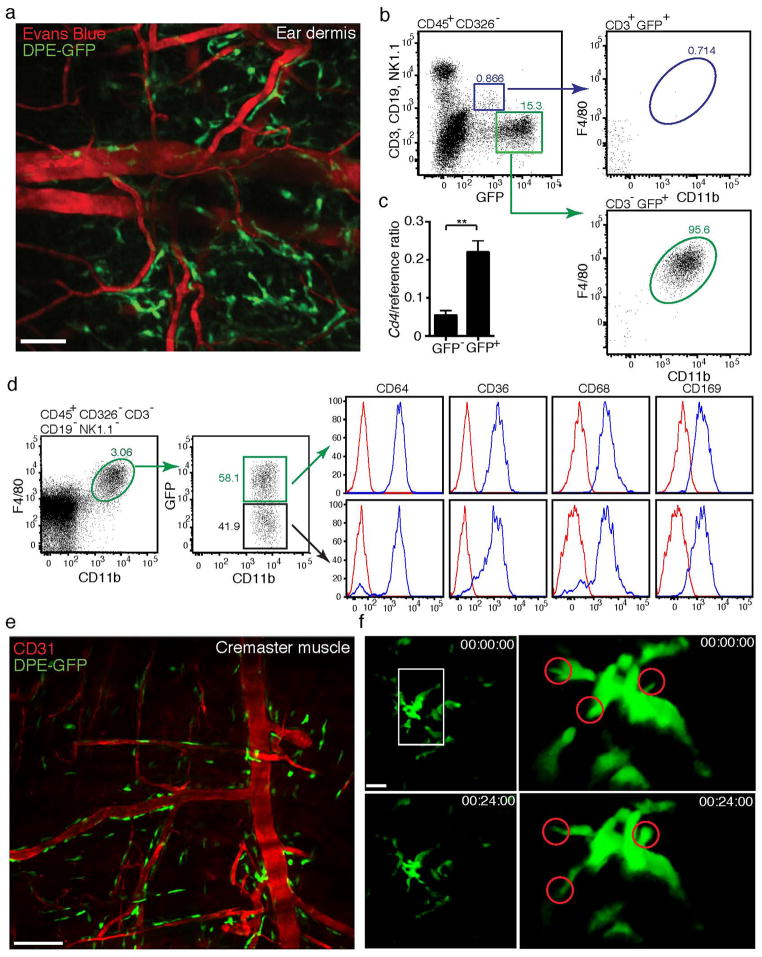

PVM can be identified in transgenic DPE-GFP mice, expressing a reporter gene under the control of CD4 regulatory elements

Close inspection of our movie sequences revealed that neutrophils often adhered in small clusters within postcapillary venules (Fig. 2b; Suppl. Movie 2), consistent with recent studies showing the extravasation of neutrophils at distinct “hotspots”8, 25, although the underlying mechanism for this preferential adherence of neutrophils is unclear. It is conceivable that microenvironmental cues, for example cells located in close proximity to post-capillary venules, may influence neutrophil adherence and extravasation. Based on the fact that CXCL1 and CXCL2, proinflammatory mediators that are preferentially produced by macrophages, were reduced in WT S. aureus infected skin, and that macrophages are often found in close proximity to blood vessels, we further tested the involvement of macrophages in neutrophil recruitment. In order to do so, we made use of transgenic DPE-GFP mice, in which GFP is expressed under the control of the CD4 enhancer/promoter26. While αβ T cells are uniformly GFP+ in these mice, we have recently discovered that a specific subset of cutaneous macrophages, namely PVM, also express GFP at higher levels than T cells (Fig. 3a and b). Thus, GFP+ cells with an elongated, dendritic shape were found to localize directly adjacent to post-capillary venules within the skin of DPE-GFP mice. On average, 38±3% (mean±SEM) of the length of venules were associated with PVM (Fig. 3a; Suppl. Movie 3). Flow cytometric analysis revealed that these GFPhi cells were CD45+CD3−CD326−CD11bhiF4/80+ (Fig. 3b). They also exhibited high cell surface expression of the resident tissue macrophage markers CD64 and ATP binding cassette transporter A1 (Suppl. Fig 3a). Based on these anatomical and phenotypic characteristics, we inferred that GFP expression in the skin of DPE-GFP mice identified PVM. A second macrophage population that exhibited lower expression of Cd4 mRNA and did not express GFP was further identified in the skin of DPE-GFP mice (Fig. 3c and d), and expressed comparable surface markers as PVM (Fig. 3d and Suppl. Fig. 3a).

(a) Multi-photon imaging of dermis of DPE-GFP mice showing presence of GFP+ cells with dendritic morphology apposed to dermal vessels (delineated by Evans Blue). Image is representative of more than 3 independent experiments. (b) Flow cytometric analysis of GFP+ cells from ear skin of DPE-GFP mice, showing expression of GFP by CD11b−F4/80−CD3+ αβ T cells and CD11b+F4/80+ CD3− macrophages (cells were pooled from 3 mice/experiment – representative of two independent experiments). (c) CD4 mRNA expression by sorted GFP+ and GFP− CD45+CD11b+F4/80+ macrophages. Bars indicate mean±SEM of 4 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using a two-tailed unpaired t-test on log transformed data. (d) Phenotypic analysis of GFP+ and GFP− macrophages in DPE-GFP mice (cells pooled from 3 mice/experiment – representative of two independent experiments). (e) Confocal imaging of GFP+ macrophages associated with post-capillary venules in cremaster muscle. (f) Multi-photon imaging of PVM in ear dermis of DPE-GFP mice showing extension and retraction of dendrites. Single cell images have been rotated to better represent dendritic behavior (circled). 00:00:00, hr:min:sec. Imaging data are representative of a minimum of 3 animals (a, e, f) in independent experiments. **P<0.01.

GFP+ macrophages were also observed in association with post-capillary venules in the cremaster muscle of DPE-GFP mice (Fig. 3e), consistent with the previous description of “adventitial” macrophages9. These cells were in close association with pericytes and did not directly contact endothelial cells (Suppl. Fig. 3b). In contrast, microglia, Langerhans cells, Kupffer cells and alveolar macrophages were GFP− (data not shown). Transcriptional profiling of GFP+F4/80+ skin cells revealed expression of Csf1r, which encodes the CSF-1 receptor and is essential for macrophage development and homeostasis (Suppl. Fig. 3c)27. Further transcriptional comparison between GFP+ vs GFP− macrophages from DPE-GFP mice revealed a small but significant increase in Tlr4 expression by PVM, while both subpopulations expressed comparable levels of mRNA for other common macrophage proteins (Suppl. Fig. 3d).

PVM could also be identified in Csf1r-EGFP (MacGreen) mice28 (Suppl. Fig. 3e). The vascular association of blood vessels with PVM in MacGreen mice was determined at 40±6%, similar to DPE-GFP mice. Since the vast majority of F4/80+ macrophages (>95%) in the skin of MacGreen mice are GFP+ (data not shown), these data suggest that GFP expression in DPE-GFP mice demarks most, if not all, PVM. We then performed intravital imaging to explore the steady-state behavior of GFP+ PVM in skin. As shown in Fig. 3f and Suppl. Movie 4, these cells were non-migratory, but displayed continuous movements of their dendrites. Similar behavior has been associated with scanning/sampling of the microenvironment in other leukocyte populations, particularly dendritic cells29.

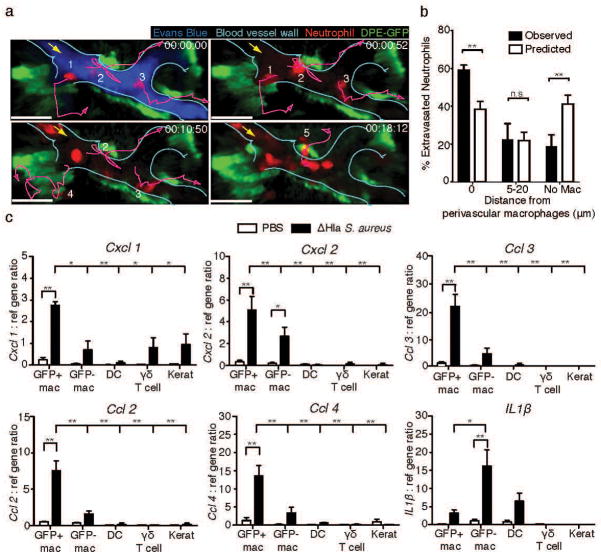

PVM interact with blood-borne neutrophils during extravasation

To test whether PVM were involved in neutrophil recruitment during S. aureus infection, we adoptively transferred red fluorescent protein (RFP)-expressing bone marrow cells from mT/mG mice30 into ΔHla S. aureus-infected DPE-GFP mice and analyzed their adherence to and extravasation from dermal venules by intravital multi-photon microscopy (93.4% ± 2.1% of transferred cells that extravasated into infected skin were neutrophils; data not shown). Neutrophils that crawled along the endothelium appeared to be attracted towards GFP+ PVM (Fig. 4a; Suppl. Movie 5). 82±4% of neutrophils that adhered in post capillary venules did so within 0–20 μm of PVM localization. 83% of neutrophil extravasation hotspots co-localized with PVM, and 80% of neutrophils exited venules within 0–20 μm of PVM. Since PVM associated with 38±3% of the wall of dermal venules, we further evaluated whether this neutrophil-macrophage correlation differed from that expected from chance alone by randomizing neutrophil extravasation throughout the entire lengths of analyzed post-capillary venules (Suppl. Fig. 4a; see Materials and Methods section for detailed description). Indeed, this analysis confirmed a preferential bias of neutrophil extravasation towards regions proximal to perivascular macrophages (Fig. 4b). A similar correlation between neutrophil extravasation and PVM localization was observed following intradermal injection of E. coli (Suppl. Fig. 4b and c), indicating that this phenomenon was not unique to S. aureus infection. Moreover, concomitant injection of E. coli with purified S. aureus hemolysin resulted in reduced neutrophil influx, ear thickness and RBC counts (Suppl. Fig. 4d–f), similar to those observed for WT S. aureus infection.

(a) Time-lapse intravital multi-photon imaging of ear dermis of DPE-GFP mice infected with ΔHla S. aureus depicting the adherence and extravasation of adoptively transferred neutrophils isolated from mT/mG mice (red, numbered 1–5) in close proximity to perivascular macrophages (green). Lines (purple) represent migration tracks of selected neutrophils (red) and the arrow (yellow) represents the direction of blood flow in the vessel (cyan). 00:00:00, hr:min:sec. Scale bar 30μm (b) Statistical analysis of neutrophil extravasation site with respect to perivascular macrophages. Numbers of neutrophils extravasating at theoretical/random (white bars) or observed (black bars) distances from GFP+ perivascular macrophages within the same vessels. Data represents 45 total extravasation events from 5 mice pooled from 2 independent experiments. Bars represent mean±SEM. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. (c) Relative gene expression by the indicated cell populations (GFP+ or GFP− macrophages, dendritic cells (DC), γδ T cells and keratinocytes) isolated from ears of ΔHla S. aureus infected or control (PBS) treated mice at 6h p.i. Data shown are mean±SEM of 3 independent experiments. P-values were calculated using two-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test (between treatment comparisons) and one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (determination of differences between GFP+ macrophages and other cell types from infected animals), *P<0.05; **P<0.01. n.s., not significant.

Based on these observations, we tested the production of chemokines by GFP+ PVM. To this end, PVM and, for comparison, GFP− macrophages, dermal dendritic cells, dermal γδ T cells and keratinocytes were isolated from the skin at six hours after ΔHla S. aureus infection and sorted to high purity. Quantitative RT-PCR revealed that GFP+ PVM were the prime producers of Cxcl1, Cxcl2, Ccl2, Ccl3, and Ccl4 (Fig. 4c and Suppl. Fig. 5). In contrast, GFP− macrophages expressed significantly lower levels of all tested chemokines but significantly higher amounts of Il-1β, while non-macrophage populations were negative for most chemokines, with the exception of low amounts of Cxcl1 in γδ T cells and keratinocytes.

Together, these data indicate that GFP+ PVMs are a major source of chemokines that have been implicated in neutrophil attraction and guide neutrophils during extravasation into infected dermis.

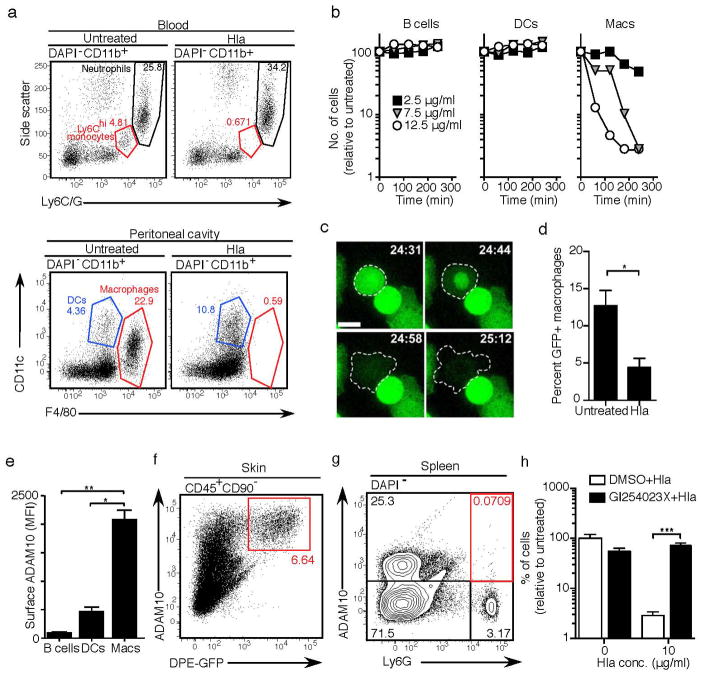

Hla induces rapid lysis of macrophages in vitro

Since both neutrophil sticking on the endothelium as well as extravasation were impaired in WT S. aureus infection as compared to the Hla-deficient strain, we hypothesized that macrophages may be sensitive to Hla-induced toxicity. To explore this possibility further, we exposed leukocytes harvested from the peritoneal cavity or peripheral blood to Hla in vitro (Fig. 5a). Monocytes and macrophages were exquisitely sensitive to Hla, while neutrophils, dendritic cells and B cells resisted Hla-induced lysis, which occurred in a time and concentration dependent manner (Fig. 5b). Real time imaging indicated a rapid loss of membrane integrity in macrophages during the early phase, thereby confirming lytic cell death (Fig. 5c; Suppl. Movie 6 and data not shown). Lysis was also observed for GFP+ macrophages harvested from ear skin (Fig. 5d).

(a) Leukocytes were isolated from peripheral blood or the peritoneal cavity and incubated with Hla (7.5 μg/ml) for 3h. Cell viability was assessed by flow cytometry. Data are representative of 3 mice from one of two experiments (blood) or more than 10 experiments (peritoneal cells). (b) Specific death of peritoneal macrophages, but not B cells or dendritic cells, in the presence of indicated concentrations of Hla. Symbols represent individual values from a single experiment using cells pooled from 3 mice. Data are representative of more than 10 independent experiments using a range of Hla concentrations and times. (c) In vitro live imaging of peritoneal macrophage cell death in the presence of Hla (7.5 μg/ml). Scale bar 10μm. 00:00, min:sec. Images are representative of two independent experiments using cells isolated from Csf1r-EGFP mice. (d) Death of GFP+ macrophages harvested from the skin of DPE-GFP mice following in vitro culture in the presence of Hla (12.5 μg/ml). Data are expressed as a percentage of total CD45+ cells and are representative of 2 independent experiments (n=4 mice/group). (e) ADAM10 expression levels on peritoneal leukocyte populations as determined by flow cytometry. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments (n=3 mice/group). (f) High level of ADAM10 expression by DPE-GFP+ cells from the skin. Data are from an individual mouse and are representative of 4 independent experiments using cells either from individual animals or pooled from 3 mice. (g) Absence of ADAM10 expression by neutrophils (Ly6G+ cells) in spleen. Data shown are from a single mouse in one of two experiments with a total of n=4 animals. (h) GI254023X mediated protection of peritoneal macrophages from Hla-induced lysis. One out of three experiments using cells pooled from 3 mice performed in quadruplicate is shown. Bars indicate mean±SD of technical replicates. MFI = geometric mean fluorescence intensity. Statistical analysis was performed as follows: (d) two-tailed t-test; (e) one-way ANOVA or (h) two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test on log transformed data. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.0001.

To determine the mechanisms underlying the specificity of Hla-induced cell death, we then measured the expression of ADAM10, which has been implicated in Hla binding to cells19, 21. While neutrophils, dendritic cells and B cells were low for ADAM10 expression, macrophages, including GFP+ dermal PVM, expressed high levels (Fig. 5e–g; Suppl. Fig. 6). Furthermore, pretreatment of peritoneal macrophages with the ADAM10-specific inhibitor GI254023X31 significantly reduced Hla-mediated lysis (Fig. 5h). Together, these data provide a molecular basis for the preferential macrophage killing by Hla.

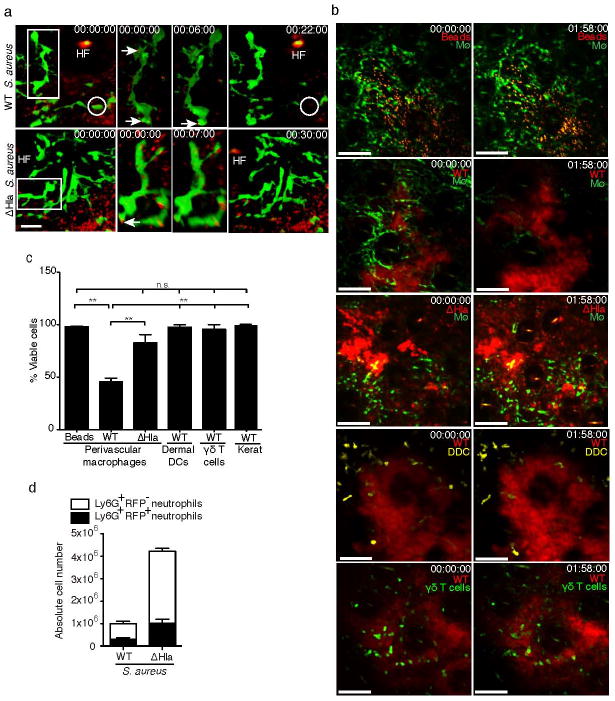

Hla induces rapid lysis of GFP+ PVM in vivo

Finally, we set out to determine whether S. aureus-derived Hla impacted on PVM integrity in vivo. In order to visualize injected bacteria in vivo, we engineered both WT and ΔHla S. aureus to express red fluorescent protein (RFP), which did not affect the growth of S. aureus strains in vitro or neutrophil influx into the skin in vivo (data not shown). On initial contact with bacteria, PVM rapidly phagocytosed both WT and ΔHla S. aureus (Fig. 6a; Suppl. Movies 7&8). However, GFP+ PVM around WT S. aureus injection sites rapidly retracted their dendrites, which was followed by their sudden disappearance within 2h of injection (Suppl. Movies 7&9), consistent with the lytic cell death observed in vitro (Fig. 5a–d). In contrast, GFP+ PVM remained intact following injection of inert beads (Fig. 6b&c; Suppl. Movie 10). Importantly, ΔHla S. aureus induced only occasional PVM death (Fig. 6b and c; Suppl. Movie 11), indicating that their destruction by WT S. aureus was Hla-dependent. Furthermore, viability of dermal dendritic cells in CD11c-YFP mice32, γδ T cells and ILC2 cells in Cxcr6+/gfp mice33, 34, and keratinocytes in mT/mG mice30 in situ was not impacted by WT S. aureus (Fig. 6b&c; Suppl. Movies 12&13 and data not shown). Consistently, freshly isolated keratinocytes did not express ADAM10, and we did not observe evidence for the killing of these cells by Hla in vitro (data not shown). Furthermore, vascular integrity, as shown by staining for CD31 and laminin was not affected by WT S. aureus even 6h post infection (Suppl. Fig. 7a), indicating that endothelial cells were not susceptible to Hla-induced lysis during early S. aureus infection. This was corroborated by the fact that vascular leakage (measured by Evans Blue extravasation) was much more pronounced post ΔHla S. aureus as compared to WT S. aureus infection (Suppl. Fig. 7b and Suppl. Movie 1, timepoint 03:00 onwards). Finally, anti-Thy-1 staining on whole mount dermal specimens did not provide evidence for damage of Thy-1 expressing stromal cells 6 hr post WT S. aureus infection (Suppl. Fig. 7c). Taken together, these data indicated that macrophages and not other stromal components or epithelial cells are the prime target of Hla during the early phase of intradermal S. aureus infection in vivo.

(a) Intravital multi-photon images showing phagocytosis of WT and ΔHla S. aureus (red) by DPE-GFP+ macrophages (green). Single cell images have been rotated to highlight bacterial uptake (arrows). A GFP+ macrophage that is lysed during the course of the video is circled. HF, autofluorescent hair follicle. Data are representative of n=2 mice/group from one of two independent experiments. (b) Intravital multi-photon images of ear skin of DPE-GFP mice (macrophage, MΦ) 2h p.i. with RFP-expressing WT S. aureus, ΔHla S. aureus or fluorescent beads. Effects of WT S. aureus infection in ear skin on dermal dendritic cells (CD11c-YFP+) or γδ T cells (CXCR6-GFP+) are also shown. Scale bar, 60 μm. Numbers represent time in hr:min:sec, Pooled data from 2 independent experiments are shown. n=6 for PVM from DPE-GFP mice infected with WT S. aureus and n=3 mice for all other groups. (c) Graph representing quantitative analysis of macrophage, DC, and T cells as shown in (b). Keratinocyte death (Kerat) was analyzed in mT/mG mice using WT S. aureus. Bars represent mean±SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. (d) absolute numbers of neutrophils with phagocytosed RFP-expressing WT or ΔHla S. aureus in the skin 12h p.i. Data show mean±SD of 3 mice/group and are representative of two independent experiments. Error bars indicate SD. **P<0.01; n.s., not significant.

Twelve hours following challenge with RFP-expressing S. aureus, the absolute numbers of RFP+ neutrophils were significantly reduced in mice infected with WT S. aureus when compared to ΔHla S. aureus (Fig. 6d), consistent with their reduced recruitment. However, the percentage of neutrophils that had internalized bacteria did not differ between tissues infected with WT and ΔHla S. aureus (Suppl. Fig. 8a). Moreover, mean fluorescence intensities of RFP-expressing S. aureus strains were comparable, as were the intensities of RFP+ neutrophils (Suppl. Figs 8b and 8c), indicating that similar numbers of bacteria were taken up by neutrophils on an individual cell basis. We concluded that Hla did not directly influence the uptake of bacteria by neutrophils, and that the increased bacterial burden in WT S. aureus compared to ΔHla S. aureus infected tissue was therefore primarily due to the reduced number of neutrophils recruited to the site. Thus, PVM-mediated regulation of neutrophil recruitment in infected skin is a critical determinant of bacterial survival and tissue reconstitution during S. aureus infection.

Discussion

Neutrophil extravasation is a tightly controlled process that is thought to primarily depend on molecular cues displayed on post-capillary endothelial cells. Thus, a cascade of consecutive interactions occurring between blood-borne neutrophils and the endothelium, characterized by rolling, firm adhesion and transendothelial migration, ensures the timely arrival of neutrophils at sites of inflammation. Our data reveal that PVM, a thus far unrecognized player in this process, provide via chemoattractant production biochemical guidance of neutrophils into the cutaneous interstitial space. Furthermore, our data indicate that S. aureus, a pathogen that usually enters the body via the skin, directly impedes neutrophil extravasation via Hla-dependent destruction of PVM. The fact that S. aureus exploits this pathway highlights its importance in the innate immune defence against bacterial pathogens.

While the central features of leukocyte recruitment into inflamed tissues have been validated in many experimental models1, 3, recent findings have also implied a role for tissue resident cells that associate with blood vessels in the coordination of inflammation. Venular pericytes, which lie between endothelial cells and the basement membrane (BM) and ensheath the vessel itself, have been shown to support neutrophil crawling during their egress from the vessel lumen8. Furthermore, NG2-expressing arteriolar and capillary pericytes activate and guide neutrophils after their extravasation and support their interstitial migration via provision of macrophage migration inhibitory factor35. Our data support a scenario where extravascular PVM directly impact on the adhesive and transmigratory activity of neutrophils in the blood stream. Thus, intraluminally crawling neutrophils finally extravasate, in the majority of cases (80%), in areas juxtaposed to GFP+ PVM. In the absence of PVM, firm adherence and TEM are markedly reduced. While we do not have evidence that PVM processes directly reach into the lumen of dermal venules, they associate tightly with pericytes, indicating that they may assist or mediate the previously observed crawling of neutrophils between pericytes. Mechanistically, based on their expression of Cxcl1 and Cxcl2 mRNA, PVM appear to create an appropriate chemokine milieu for the egressing neutrophil. The discontinuous association of PVM with the vessel wall implies the existence of confined areas of increased chemokine deposition within post-capillary venules and subsequent patchy arrest of neutrophils. Consistently, we noted that following challenge with ΔHla S. aureus, neutrophils arrested in small clusters, rather than continuously along the venular wall, and preferentially extravasated at circumscribed locations that were adjacent to PVM. Neutrophil extravasation hotspots have been reported to occur due to a range of mechanisms including the presence of tricellular junctions36, pericyte gaps8, or to regions of low basement membrane protein expression37. Collectively, based on their intimate association with the vessel wall, PVM are thus in an ideal position to contribute to focal chemokine gradients, which may either be transported to the luminal surface of endothelial cells and/or act as a migratory cue directly after TEM.

Although the existence of PVM within the dermis has been sporadically reported, this has generally been an incidental finding, and no particular functions have been ascribed to them9, 38. Given the striking capacity of DPE-GFP+ PVM to produce chemokines and mediate neutrophil recruitment, this raises the question of whether analogous populations exist in other organs. Preliminary analysis of GFP-expressing perivascular cells in a range of tissues of DPE-EGFP mice, including cremaster muscle, meninges and adipose, indicated the presence of such cells. However, in other organs, such as the lungs and spleen, GFP+ PVM were scarce or absent. These findings may help explain some of the well-documented organ-specific differences in leukocyte homing during inflammation. Skin and muscle, for example, display, by and large, similar molecular requirements for neutrophil entry, while in the lungs and spleen leukocyte homing follows different rules.

Another salient observation from DPE-GFP mice was the existence of macrophage heterogeneity within the dermis, as indicated by the presence of GFP+ and GFP− populations. While the phenotypic profile of these cells was largely identical (with the exception of Cd4 and Tlr4 mRNA expression), they exhibited distinct functional properties, as demonstrated for chemokine and cytokine production profiles. Macrophage heterogeneity within a single tissue, in terms of both developmental pathways and functions, has previously been reported. For example, in the brain, a numerically major population comprises long lived and/or self-renewing microglia, which originate from yolk-sac derived precursors during embryogenesis39; however, the existence of a second population of perivascular macrophages that originate from hematopoietic sources has long been appreciated.10 Future studies will have to determine the precise lineage relationship of GFP+ and GFP− dermal macrophages during ontogeny and in adult animals.

While bacterial virulence factors have been studied extensively in the past, how exactly they disrupt specific microenvironments is poorly understood. To the best of our knowledge, our study provides the first direct visualization of the action of a defined virulence factor, Hla, in real time in situ. Although the virulence of S. aureus certainly cannot be ascribed to any single factor, it is accepted that Hla, which shows near ubiquitous expression by clinical isolates, is a major determinant. We observed diminished adhesion of neutrophils during WT S. aureus infection, which is in line with the previously described reduced leukocyte homing induced by E. coli expressing alpha-hemolysin40. The main finding of our live microscopy experiments was the rapid and specific destruction of GFP+ PVM by Hla. The resultant impact on neutrophil homing into inflamed skin is consistent with several different strategies employed by S. aureus to modulate neutrophil functions41. Nevertheless, given the indispensable role of Hla in the induction of tissue necrosis, it is plausible to postulate that Hla-mediated destruction of PVM represents a major mechanism by which the bacterium thwarts the ensuing innate immune response, at least during its earliest phase. During later stages, other bacterial factors, such as PSMs and other leukocidins, which exhibit neutrophil chemotactic activity and are primarily produced by CA-MRSA, may also play a role16. Indeed, neutrophils continue to be recruited even in wildtype S. aureus infections, albeit at reduced numbers as compared to Hla-deficient bacteria. Collectively, our findings thus argue that the net effect of Hla-mediated PVM destruction is a delay in neutrophil influx into the dermis, which is thereby likely to give the bacterium a survival advantage.

The specificity of macrophage killing by Hla likely relates to the high expression of its receptor ADAM10 on macrophages. Mechanistically, binding of Hla to ADAM10 in epithelial cells during lung inflammation was demonstrated to induce ADAM10 activity, which eventually mediates the breakdown of epithelial integrity via cleavage of E-cadherin19. Such a pathway was proposed to be the dominant cause of necrosis in both pulmonary19 and cutaneous20 infection models. Other studies have suggested that Hla acts predominantly as a cytotoxin21, 42, and our data are consistent with this notion, since Hla lysed macrophages from various sources both in vitro and in vivo. Nevertheless, our data do not discount the reported role for Hla/ADAM10 interactions in mediating virulence through disruption of epithelial integrity. In our model we observed tissue necrosis at times beyond 24 hours p.i. but cannot formally ascribe this to increased bacterial load. This finding is consistent with recent studies by Inoshima et al. who specifically targeted ADAM10 deletion to keratinocytes20 or alveolar epithelial cells19. Following WT S. aureus infection, these authors found that necrosis occurred at later stages of infection but this was not associated with changes in bacterial numbers, which suggests that independent mechanisms may underpin necrosis and bacterial clearance.

PVM in human skin may contribute in a similar manner to neutrophil recruitment during bacterial infection, and may also be targets of S. aureus. Thus, the interference with Hla-ADAM10 interactions on these cells by small molecule inhibitors or anti-Hla antibodies may prove a useful treatment strategy for antibiotic-resistant S. aureus infections.

In summary, we have described a population of PVM that is a dominant source of neutrophil-recruiting chemokines during dermal S. aureus infection. The existence and likely functions of PVM emphasize the critical role of non-endothelial, but blood vessel associated cells in the co-ordination of leukocyte extravasation. The selective killing of PVM by S. aureus produced Hla results in diminished availability of chemokines immediately following bacterial invasion. This is likely to give the bacterium an extended window of opportunity to proliferate in the absence of antimicrobial neutrophil effector mechanisms. Thus, the fine-tuning of the inflammatory influx by skin resident cells during the first hours of bacterial invasion is critical for the control of infection.

Materials and Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 (WT) mice were purchased from the Animal Resources Centre (Perth, Australia). Albino C57BL/6 (C57BL/6-Tyrc-2J also referred to as WB6) and mT/mG mice30 were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory; LysM-EGFP mice were a kind gift from Thomas Graf23 Csf1r-EGFP (MacGreen) mice were a kind gift from David Hume28. CD11c-YFP mice32 were a kind gift from Michel Nussenzweig. DPE-GFP mice were described previously26. Mice were bred and maintained on the C57BL/6 background in pathogen–free conditions at the Centenary Institute animal facility. 8–16 week old mice of either sex were used for experimentations. The Animal Ethics Committee of University of Sydney approved all animal experiments.

Bacterial strains

S. aureus 8325-4 (WT) and its isogenic Hla-deficient strain S. aureus DU1090 (ΔHla) were kindly provided by Dr. Mark Willcox, University of NSW, Australia. S. aureus DU1090 was generated as described previously43. S. epidermidis ATCC12283 and E. coli DH5α (Invitrogen) were used as indicated. USA300 was a kind gift from Dr. Elizabeth Harry, University of Technology Sydney. Bacteria were grown to mid log-phase in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth, washed, and resuspended in PBS. Bacterial concentrations were estimated with a spectrophotometer by determining the optical density at 600 nm (OD600). Colony-forming units (CFUs) were verified by plating dilutions of the inoculum onto LB agar overnight at 37°C.

Generation of red fluorescent protein (RFP)-expressing S. aureus strains

The shuttle-plasmid pSK9054 was used in order to express RFP in S. aureus strains. On pSK9054, the moderate-strength staphylococcal promoter, Porf90, was used to drive the transcription of mRFPmars44, a fluorescent protein that is highly codon-adapted to S. aureus. Transcription from the Porf90 promoter in pSK9054 is constitutive, and S. aureus cells expressing mRFPmars from this plasmid attain a high-level of fluorescence (Suppl. Fig. 8c). A DNA fragment containing the mRFPmars ORF, which included a strong ribosomal binding site upstream from the initiation codon, was amplified by PCR from plasmid pmRFPmars44 (Addgene plasmid 26252) with sense oligonucleotide AB62 (CGGGATCCTAGGAAAGGAGGATG) and anti-sense oligonucleotide AB63 (GGGGTACCTTAATGATGGTGGTGATGATGG), using iProof™ High Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Bio-Rad). Following amplification, the resultant 727 bp fragment was purified using a Bioline ISOLATE PCR and Gel Kit, prior to digestion with KpnI restriction endonuclease (NEB). The digested fragment was purified as per above, and was treated with T4 polynucleotide kinase (PNK; NEB) in order to phosphorylate the blunt 5′ end of the amplicon. Concurrent with this process, 2 μg of plasmid pSK706345 DNA was digested with BamHI (NEB), gel purified (Bioline ISOLATE PCR and Gel Kit), and the recessed ends of the digested fragments were in-filled using Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene). The blunted plasmid fragment was purified as above, prior to digestion with KpnI. pSK7063 DNA prepared in this way was used in a ligation reaction with the amplified mRFPmars ORF fragment, and then used to transform chemically competent E. coli DH5α cells. The integrity of a resulting construct was checked by sequencing (Australian Genome Research Facility) and designated pSK9054. RFP-expressing derivatives of S. aureus strains 8325-4 and DU1090 were obtained by electroporation of pSK9054 essentially as described previously46.

Mouse model of cutaneous bacterial infection and in vivo blocking of Hla

Approximately 107 CFUs of bacteria were injected intradermally in a small volume of PBS (4μl) into the pinnae of each ear using a 29g insulin syringe (BD). In some experiments, bacteria (107 CFUs) were injected subcutaneously into the back skin of mice. In some experiments, injections of ΔHla S. aureus were combined with Hla purified from S. aureus (Sigma-Aldrich). For in vivo blocking of Hla, 8h before infection mice were administered intra-peritoneally with 2.5mg of whole antiserum against Hla or control rabbit serum (both from Sigma-Aldrich). Sera were dialysed in PBS before use. For intravital imaging, approximately 2×106 CFUs of bacteria were injected into the pinnae of each ear in a volume of 0.5μl PBS using a 35g Hamilton syringe.

Tissue processing and flow cytometry

Isolation of skin cells involved the following process: Ears were split into dorsal and ventral halves using forceps and subjected to enzymatic digestion with collagenase type IV (2 mg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS for 60 min at 37°C to release cells. To obtain single-cell suspensions, the tissues were filtered through an 80μm stainless steel mesh. Cell and RBC numbers were determined using a hemocytometer. For flow cytometric analysis, single-cell suspensions were incubated with anti-CD16/32 (2.4G2; BD) to block Fc receptors and stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies diluted in “FACS buffer” (PBS containing 5% FCS, 2 mM EDTA, and 0.02% sodium azide). Resident tissue macrophages from spleen and peritoneal cavity were isolated and identified as descried previously47. Fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies (purchased from BD, eBioscience, BioLegend, AbD Serotec, R & D Systems or Invitrogen) against the following cell surface molecules were used: CD45 (clone 30-F11), CD11b (clone M1/70), Ly6G (clone 1A8), Ly6C (clone HK1.4), CD64 (clone X54-5/7.1.1), F4/80 (clones BM8 or Cl:A3-1), ABCA1 (clone 5A1-1422), CD36 (clone HM36), CD169 (clone MOMA1), ADAM10 (clone 139712), CD326 (clone G8.8), CD19 (clone 1D3), CD3 (clone 145-2C11), NK1.1 (clone PK136) CD68 (clone FA-11). Samples were first stained for cell surface molecules and aquafluorescent reactive dye (Invitrogen) for dead cell exclusion after fixation with 4% formalin. In some experiments cells were analyzed unfixed and DAPI was used as a viability marker. Samples were acquired on a LSR Fortessa or 10-laser LSR SORP flow cytometer (BD) and data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc.). Sorting was performed using a 10-laser Influx sorter (BD).

Whole mount staining

Whole mount staining on infected ears was performed as described previously33. Briefly, dorsal and ventral halves of untreated or WT S. aureus infected ears were split 6 hour p.i. The dorsal halves were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at 37°C. The tissue was washed with PBS containing 5% FCS, 0.3% Triton X100 and 2mM EDTA (immunostaining buffer) for 30 min at 37°C. The samples were then incubated with anti-CD31 (Clone:MEC13.3, BD biosciences) and anti-laminin (Sigma-Aldrich) primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The tissue samples were washed three times with immunostaining buffer and incubated with Goat Anti Rat Alexa 647 and Goat Anti Rabbit Alexa 405 antibodies for 4 hr at 4°C. The tissues were thoroughly washed and mounted using antifade (DABCO). For Thy-1 staining anti-Thy-1 (Clone: 30-H12, BD biosciences) primary antibody was used followed by goat anti rat Alexa 647 as the secondary antibody. For imaging of cremaster muscle, the tissue was exteriorized, dissected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at 37°C and processed as described above. The tissue was then stained with anti-CD31 (Clone:MEC13.3, BD biosciences) and anti-smooth muscle actin (Clone: 1A4, Abcam) followed by goat anti rat Alexa 647 and goat anti rabbit Alexa 594 antibodies. Confocal imaging was performed using Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope system. Images were processed using Volocity software (Perkin Elmer).

Quantification of tissue bacterial burden after infection

S. aureus strains (WT and ΔHla) were inoculated intradermally into the ears as described above. At 24, 48 and 72 hours p.i., ears were harvested, weighed and then mechanically homogenized using a rotor stator homogeniser (Polytron, Lucerne, CH) in 2 mL of sterile PBS. Serial dilutions of ear homogenates were plated on LB agar plates. Plates were incubated at 37°C overnight and CFUs were counted the following day.

Histologic analysis of skin lesions

Pinnae of PBS or S. aureus infected mice were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and hematoxylin and eosin sections prepared according to standard procedures.

Cytokine measurement of tissues

Cytokine and chemokine content of tissue homogenate was measured using Cytometric Bead Array assay (BD) as recommended by the manufacturer. CXCL2 protein in homogenates was quantified using a Quantikine ELISA kit (R & D Systems). Briefly, tissues were mechanically homogenized using a rotor stator homogeniser (Polytron) in PBS containing protease inhibitors (Halt™ protease inhibitor; Thermo Scientific) and 5mM EDTA. The homogenate was then centrifuged 15,000g for 10 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatant was then used for cytokine quantification.

RT-qPCR

Tissues were homogenized in RLT buffer (Qiagen, CA), using a rotor stator homogeniser (Polytron). RNA was extracted using an RNeasy miniprep kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions and reverse-transcribed using Moloney murine leukemia virus-RT (Ambion) primed with random hexamers (GeneWorks, Australia). Quantitative PCR was performed using the primers listed below on a Corbett Research Rotor Gene 3000 using kapa SYBR Green (KAPA Bioystems, MA) with cycling conditions as follows: 2 min 95°C denaturation and then 35 repeats of a two-step amplification cycle (95°C for 15s and 60°C for 45s). Following amplification, product purity was assessed by melt-curve analysis. Gene-expression levels were normalized against the geometric mean of 4 reference genes (HPRT, RPL13a, β-actin and YWHAZ). In tissue samples, expression was then normalised to the PBS challenged group. The following primers were used for RT-qPCR: RPL13a: RPL13a: 5′-CTTAGGCACTGCTCCTGTGGAT-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGTGCGCTGTCAGCTCTCTAAT-3′ (antisense); HPRT: 5′-GCTTTCCCTGGTTAAGCAGTACA-3′ (sense) and 5′-CAAACTTGTCTGGAATTTCAAATC-3′ (antisense); YWHAZ: 5′-TGTCACCAACCATTCCAACTTG-3′ (sense) and 5′-ACACTGAGTGGAGCCAGAAAGA-3′ (antisense); β-actin: 5′-CCCCAACTTGATGTATGAAGGC-3′ (sense) and 5′-TCAAGTCAGTGTACAGGCCAGC-3′ (antisense); CXCL1: 5′-TGTCAGTGCCTGCAGACCAT-3′ (sense) and 5′-CCTGAGGGCAACACCTTCA-3′ (antisense); CXCL2: 5′-CCCTCAACGGAAGAACCAAA-3′ (sense) and 5′-AGGCACATCAGGTACGATCCA-3′ (antisense); IL-1b 5′-GTGGTTCGAGGCCTAATAGGCT-3′ and 5′-AGCTGCTTCAGACACCTTGCA- 3′ (antisense); (sense), CCL2: 5′-GGCTCAGCCAGATGCAGTTAA-3′ (sense) and 5′-CCTACTCATTGGGATCATCTTGCT-3′ (antisense); CCL3: 5′-CATATGGAGCTGACACCCCG-3′ (sense) and 5′-CGTGGAATCTTCCGGCTGTA-3′ (antisense); CCL4: 5′-AGGGTTCTCAGCACCAATGG-3′ (sense) and 5′-GCTGCCGGGAGGTGTAAGA-3′; F4/80: 5′-GGCATACCTGTTCACCATTATCAAC-3′ (sense) and 5′-CCTGGTGAGGAGTTTCTTATATTCATC-3′ (antisense); γδTCR: 5′-TTTGAACCATATGCAAATTCTTTCA -3′ (sense) and 5′-GTGACTCTTGGGCCATAGCAA-3′ (antisense); MHC class II: 5′-AGTCACACCCTGGAAAGGAAGG-3′ (sense) and 5′-TCACCCAGCACACCACTTCTT-3′

Quantification of gene expression in sorted macrophages

Briefly, ears were injected with live ΔHla S. aureus, and 4–6 hours later cell suspensions were prepared and stained for flow cytometric analysis. Cell populations were identified as follows: macrophages (DAPI−CD45+CD11bhiCD64hi), dendritic cells (DAPI−CD45+CD64−MHCIIhi), γδT cells (DAPI−CD45+CD64−MHCII−CD3+ γδT+) and keratinocytes (DAPI−CD45−CD326+CD90−). Cells were sorted (1000–2000 per population depending on experiment) using an Influx sorter (BD) into RLT plus lysis buffer (Qiagen). Due to low numbers of cells isolated from ears, sort purity was assessed by expression of cell population specific genes (Suppl Fig 5). RNA was extracted using an RNeasy micro plus kit (Qiagen), followed by RT-qPCR as described for tissue homogenates.

Homing experiments

Mice were infected with S. aureus (WT or ΔHla) for 10h as described above. Afterwards, 107 CFSE-labeled bone marrow cells were adoptively transferred via tail vein injection. Two hours later, ears were harvested and quantified for the presence of CFSE+Ly6G+ neutrophils. For confocal imaging, mice were infected for 6h with labeled WT or ΔHla S. aureus following which 10–20×106 LysM-EGFP bone marrow cells were adoptively transferred and tissue harvested 1h post transfer. Tissue samples were stained and imaged as described above or harvested for flow cytometry.

Myeloperoxidase assay

Samples were homogenized in potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) containing 0.5% hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide. The suspension was centrifuged at 18,000g for 20 min, and 10μl of supernatant was added to 190μl of potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) containing 0.167 mg/ml o-dianisidine dihydrochloride (Sigma) and 0.0005% hydrogen peroxide. Activity of MPO in tissues was determined by absorbance at 460nm.

Multi-photon intravital imaging of skin and image analysis

Preparation of animals and imaging was performed as previously described22. In brief, mice were anesthetized by i.p. injection of Ketamine/Xylazine (80/10mg/kg), with repeated half-dose injections as required. The ears were treated with Nair cream (Church & Dwight) to remove hairs. The animals were then placed onto a custom-built stage to position the ear on a small metal platform for multi-photon (MP) imaging. The ear was immersed in PBS/glycerin (70:30, vol:vol) and covered with a coverslip. The temperature of the platform was regulated independently, and maintained at 35°C, whereas the body temperature was kept at 37°C using a heating pad placed underneath the mouse. MPM imaging was performed on a LaVision BioTec TriMScope attached to an Olympus BX-51 fixed stage microscope equipped with 20x (NA 0.95) water immersion objectives. The setup includes six external non-descanned dual-channel reflection/fluorescence detectors, a diode pumped, wideband mode-locked Ti:Sapphire femtosecond laser (MaiTai HP; SpectraPhysics, 720nm–1050nm, <140fs, 90MHz), and an APE Optical Parametric Oscillator system (tuning range 1050–1400nm). To understand the neutrophil recruitment defect, ears of WB6 mice were injected intradermally with 2–3×106 CFUs of either WT or ΔHla S. aureus bacteria in a volume of 0.5μl PBS using a 35g Hamilton syringe. After 6 hours, ears were mounted onto the imaging stage as described above. Bone marrow cells (10–20×106) from LysM-EGFP mice were injected intravenously followed by Evans blue (Evans blue conjugated to BSA) and imaging was performed for 300×300 μm region of the ear dermis at 250×250 pixel resolution at 1 frame/second for 10 min. For observing the correlation between neutrophil extravasation and perivascular macrophages in DPE-GFP mice, 2–3×106 CFUs of ΔHla S. aureus bacteria were injected in a volume of 0.5μl PBS 6h before imaging. Bone marrow cells (10–20×106) from mT/mG mice were injected intravenously followed by Evans blue and imaging was performed for 300×300 μm region at 500×500 pixel with 6–8 z steps 4 μm apart for 20–30 min. In experiments involving perivascular macrophage cell death fluorescent beads, RFP-expressing WT S. aureus or ΔHla S. aureus bacteria were used for infection and imaging performed immediately. Images were recorded for 500×500 μm region at 500×500 pixel with 10–12 z steps 4 μm apart every 2 min for 2hr. All images were processed using Image J (NIH, Bethesda) and image stacks were then transformed into movies using Volocity software (PerkinElmer). Migration parameters and cellular interactions were determined using Volocity as described previously48.

Analysis of intravascular neutrophil behaviour

Neutrophil rolling was defined as the movement of cells along the blood vessel wall at a velocity lower than free flowing cells. Sticking was defined as neutrophil arrest for more than 30s without movement of more than one cell diameter. Extravasation was defined as the migration of sticking cells from the vessel lumen to the interstitium during the period of analysis. Only post-capillary venules were considered and the complete observation period (at least 10 min) of data acquisition was analyzed.

Determination of vascular association of blood vessel to PVM

Vascular association refers to the length of blood vessel associated with PVMs and was calculated using the following formula:

To determine this fraction for Csf1r-EGFP (MacGreen) mice, intravital imaging was performed for up to 2hrs and only non-migratory GFP+ cells along blood vessels were considered for analysis.

Methodology to determine neutrophil-perivascular macrophage interactions

The total events of neutrophil extravasation observed experimentally were arranged at equal distance to one another in the blood vessel under analysis (each blood vessel for each set of observation). The proximity of these equally distributed simulated extravasation locations to the nearest PVM was measured and used as the predicted measurement (Suppl. Fig. 4a). In both cases of observed and predicted values only the perivascular macrophage on the same side of the neutrophil extravasation were considered. “Hotspots” were defined as regions along the blood vessels from where 2 or more neutrophils extravasated during the imaging period.

Quantification of cell lysis in situ

Image stacks (500×500 μm, 10–12 z planes at 4μm step size) were recorded every 2 min for 2hr. Indicated fluorescent cells were counted at the start and end time points. Cell death was calculated as % viable cells at the end if the imaging session.

Hla treatment in vitro

Whole blood from WT C57BL/6 mice was collected in Alsevers solution prior to RBC lysis in ACK Lysing Buffer (Life Technologies) and washing in serum-free RPMI (Life Technologies) prior resuspension in RPMI and Hla treatment (7.5μg/ml) at 37°C for 3 hours. Peritoneal lavages from WT C57BL/6 mice were collected and pooled in serum-free RPMI before separating into 400μl aliquots at a concentration of 106 cells/ml. Hla was added at indicated concentrations and incubated up to 4 hours in RPMI at 37°C. For inhibition of ADAM-10 dependent Hla-mediated lysis, peritoneal cells were pre-incubated with 80μM GI254023X (Okeanos Tech.) for 60min at 37°C followed by addition of a two-fold stock Hla leading to a final concentration of 40μM GI254023X49 and 10μg/ml of Hla in the cell suspension which was incubated for a further 20–30 minutes. Following incubation, cells were washed in FACS buffer and stained with anti-CD19 APC-Cy7 or PE (clone 1D3), anti-CD11c PE-Cy7 (clone HL3), anti-CD11b FITC (clone M1/70) and anti-F4/80 PE (clone BM8) or A647 (clone: CI:A3-1) antibodies (all purchased from BD or AbD Serotec) and assessed by flow cytometry using 10-laser LSR II cytometer (BD). Data were analyzed using Flowjo software (Tree Star, Inc.). Live B cells (CD19+), DCs (CD11c+) and macrophages (CD11bhi F4/80hi) were evaluated by DAPI-exclusion and enumerated by adding a known number of fluorescent calibration particles to allow the determination of cell number. The number of live cells for each subtype were normalised relative to the number of corresponding cells in untreated (no Hla) controls co-cultured under identical conditions.

In vitro time-lapse microscopy

Whole peritoneal lavages from MacGreen mice in which the GFPhi cells are predominantly macrophages, were plated on to a FluoroDish™ (World Precision Instruments) immediately prior to addition of Hla (7.5μg/ml) and subsequent imaging. Cells were then imaged using a Leica SP500 confocal microscope equipped with resonant scanner in a humidified, 37°C chamber with 5% CO2 for up to three hours. Differential interference contrast and fluorescence images were simultaneously collected using a 488nm laser, and data were analyzed and converted to movies using ImageJ64.

General experimental design and statistical analysis

For animal experiments, littermates were randomly distributed to the treatment groups so that all groups were age and sex matched (no specific randomization or blinding protocol was used). No animals were excluded from the analysis. A single outlier sample from the 12 h PBS group (Fig. 1c) was excluded from analysis using the robust outlier detection method (Prism Software) based on pooled data from both PBS groups. Statistical analyses were performed using Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc.). Following experiments, where group size was adequately large, data were assessed for normality using a Kolmogrov-Smirnov test, and parametric or non-parametric tests applied as appropriate. Where data was demonstrated or suspected to deviate overtly from normality, or if there were unequal variances between groups, log transformation was applied prior to statistical analysis (as indicated in figure legends). Differences in P-value between treatment two groups were determined using a two-tailed unpaired t-test (parametric data). Alternatively, Mann-Whitney U test was used on non-parametric data. One-way ANOVA followed by either a Bonferroni or a Dunnett multiple comparison test (as described in figure legends) was used to determine statistical significance. Statistical difference was assumed if P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Supp. Figs

Supplementary Figure 1. Effect of Hla on bacterial infection parameters. (a) Ear thickness, (b) RBC count following infection of C57BL/6 mice with WT or ΔHla S. aureus at various time points. (c) Ear swelling response and (d) RBC count of concomitant injection of purified Hla together with ΔHla S. aureus 12 hours p.i. (e) Neutrophil myeloperoxidase activity in back skin of mice infected with WT or ΔHla S. aureus at 12 hours p.i. (f) Neutrophil influx into ears infected with S. aureus strain USA300 in the presence or absence of anti-Hla serum. Student’s two-tailed unpaired t-test was used to determine the P-value. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. Error bars indicate SD. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

Supplementary Figure 2. Hla supresses the homing of adoptively transferred LysM-EGFP+ neutrophils to the site of infection. (a) Confocal imaging of extravasated LysM-EGFP+ neutrophils in dermis of WT or ΔHla S. aureus 6 hours p.i. Blood vessels are visualized by CD31 staining. Scale bar represents 100μm. (b) Flow cytometric analysis of ΔHla S. aureus infected tissue 1h post LysM-EGFP bone marrow cell transfer showing percentage of extravasated neutrophils (Ly6G+Ly6Cint) and monocytes (Ly6G−Ly6Chi). (c) CCL2, CCL3 and CCL4 protein levels in mice infected with WT S. aureus or ΔHla S. aureus. Five to six mice/group/time point. Student’s two-tailed unpaired t-test was used to determine the P-value. ***P<0.001.

Supplementary Figure 3. Phenotypic analysis of PVM. (a) Flow cytometric analysis of GFP+ and GFP− macrophages from skin of DPE-GFP mice in comparison to red pulp and peritoneal macrophages. (b) Confocal imaging of cremaster muscle showing the localization of PVMs (green) in relation to pericytes (anti-smooth muscle actin, red) and endothelial cells (blue). (c) Expression of Csf1r mRNA transcripts in GFP+ macrophages from DPE-GFP mice. (d) Comparative mRNA expression of indicated genes in GFP+ vs GFP− dermal macrophages from DPE-GFP mice. (e) Intravital imaging of ears from Csf1r-EGFP mice showing presence of GFP+ PVM (asterisk). Student’s two-tailed unpaired t-test was used to determine the P-value. *P<0.05

Supplementary Figure 4. Neutrophils extravasate adjacent to perivascular macrophages during E. coli infection. (a) Figure depicts the methodology employed to calculate predicted neutrophil to macrophage correlation (detailed in Materials and Methods section). The total observed extravasation tracks for the blood vessel imaged are overlayed in comparison to the predicted tracks. The insets depict one such event of neutrophil extravasation (red) from blood vessel (blue, vessel wall marked in cyan) in relation to PVM (green, asterix in main figure). 00:00, min:sec. (b) Time-lapse intravital multi-photon imaging of ear dermis of DPE-GFP mice infected with E. coli depicting the adherence and extravasation of adoptively transferred neutrophils isolated from mT/mG mice (red, numbered 1–4) in close proximity to PVM (green). Lines (white) represent migration tracks of selected neutrophils (red) 00:00:00, hr:min:sec. (c) Statistical analysis of neutrophil extravasation site with respect to perivascular macrophages. Numbers of neutrophils extravasating at theoretical/random (white bars) or observed (black bars) distances from GFP+ PVM within the same vessels. Data is cumulative of 50 events of extravasation from 3 independent experiments. (d) Neutrophil influx, (e) ear thickness and (f) RBC counts of ears concomitantly injected with E. coli and Hla (10μg) or only E. coli alone for 12 hours p.i. Data shown are mean±SEM of 3 independent experiments. P-values were calculated using two-way ANOVA or two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test, **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001; n.s., not significant.

Supplementary Figure 5. Expression of lineage specific genes by sorted skin resident populations in DPE-GFP mice. The indicated cell populations (GFP+ or GFP− macrophages, dendritic cells, γδ T cells and keratinocytes) were isolated from ears of ΔHla S. aureus infected, or control (PBS) treated mice at ~6 hours p.i. For each population, the relative expression of indicated lineage-associated genes was determined by RT-qPCR. Data shown are mean±SEM of 3 independent experiments.

Supplementary Figure 6. ADAM10 expression on peritoneal macrophages. Flow cytometric quantification of surface ADAM10 expression on B cells, dendritic cells (DC) and macrophages (macs) isolated from peritoneal cavity. Fluorescence minus one controls are shown by grey histograms. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Supplementary Figure 7. Vascular integrity is unaffected by S. aureus infection. (a) Confocal imaging of ear whole mounts from untreated DPE-GFP mice (left panels) or animals infected with WT S. aureus (right panels). Basement membranes are delineated by laminin and endothelium by CD31 labeling. (b) Intravital imaging of Evans blue (red; conjugated to BSA) leakage from ΔHla or WT S. aureus infected tissue 6hr p.i. Adoptively transferred neutrophils (green) and SHG (blue) are also depicted. The images are tiles of 1mm×1mm region of ear tissue. (c) Confocal imaging of Thy-1 stained ear whole mounts from untreated DPE-GFP mice (left panels) or animals infected with WT S. aureus (right panels) showing no appreciable loss of Thy-1+ cells.

Supplementary Figure 8. Comparable uptake of WT and ΔHla S. aureus by neutrophils. (a) Percent neutrophils containing RFP-expressing S. aureus strains were determined by flow cytometry at 12h p.i. (b) Representative dotplots illustrating fluorescence intensity of neutrophils containing RFP-expressing WT or ΔHla S. aureus. (c) Fluorescence intensity of RFP expressing S. aureus strains as determined by flow cytometry. Data are representative of two independent experiments (four to five mice/group). Error bars indicate SD.

Supplementary Movie 1. Time-lapse intravital imaging of mice infected with either WT or ΔHla S. aureus depicting neutrophil rolling and sticking in dermal blood vessels (red). The mice were infected 6hr before imaging and neutrophils (green) were adoptively transferred immediately prior to imaging. Time represents min: sec. Increased red background in ΔHla S. aureus infection is observed due inflammation induced vascular leakage of Evans blue.

Supplementary Movie 2. Time-lapse intravital imaging of ear dermis of mice infected with ΔHla S. aureus depicting hotspots for neutrophil sticking and extravasation from the blood vessel (red). The mice were infected 6hr before imaging and neutrophils (green) were adoptively transferred immediately prior to imaging. Time represents min: sec.

Supplementary Movie 3. Z stack of ear dermis of DPE-GFP mice showing the localisation of GFP+ macrophages (green) along dermal blood vessel (red). Second harmonic generation is depicted in blue.

Supplementary Movie 4. 3D time lapse reconstruction of Z stacks of ear dermis of DPE-GFP mice showing the homeostatic scanning behaviour of GFP+ macrophages. Time represents hr: min: sec.

Supplementary Movie 5. Time-lapse intravital imaging of ear dermis of mice infected with ΔHla S. aureus depicting neutrophil (red) extravasation in relation to GFP+ perivascular macrophages (green). The mice were infected 6h before imaging and neutrophils were adoptively transferred immediately prior to imaging. Time represents hr: min: sec.

Supplementary Movie 6. In vitro time-lapse imaging of macrophage (green) death in the presence of Hla (7.5μg/ml). Time represents min: sec after addition of Hla.

Supplementary Movie 7. 3D time lapse reconstruction of Z stacks of ear dermis of DPE-GFP mice infected with WT S. aureus (red) showing the behaviour of GFP+ macrophages in presence of WT S. aureus. Imaging was performed immediately after injection of the bacterium. Time represents hr: min: sec.

Supplementary Movie 8. 3D time lapse reconstruction of Z stacks of ear dermis of DPE-GFP mice infected with ΔHla S. aureus (red) showing the behaviour of GFP+ macrophages in presence of ΔHla S. aureus. Imaging was performed immediately after injection of the bacterium. Time represents hr: min: sec.

Supplementary Movie 9. Time-lapse intravital imaging of ear dermis of mice injected with RFP-expressing WT S. aureus (red) in relation to perivascular macrophages (green). The mice were injected just before imaging. Time represents hr: min: sec.

Supplementary Movie 10. Time-lapse intravital imaging of ear dermis of mice injected with fluorescent beads (red) in relation to perivascular macrophages (green). The mice were injected just before imaging. Time represents hr: min: sec.

Supplementary Movie 11. Time-lapse intravital imaging of ear dermis of mice injected with RFP-expressing ΔHla S. aureus (red) in relation to perivascular macrophages (green). The mice were injected just before imaging. Time represents hr: min: sec.

Supplementary Movie 12. Time-lapse intravital imaging of ear dermis of dermal dendritic cells (yellow) in CD11c-YFP mice injected with RFP-expressing WT S. aureus (red). The mice were injected just before imaging. Time represents hr: min: sec.

Supplementary Movie 13. Time-lapse intravital imaging of ear dermis of γδ T cells (green) in CXCR6-GFP mice injected with RFP-expressing WT S. aureus (red). The mice were injected just before imaging. Time represents hr: min: sec.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Mark Willcox for providing S. aureus strains, Elizabeth Harry for providing S. aureus USA300, Thomas Graf and David Hume for providing LysM-EGFP and MacGreen mice, respectively, and Martin Fraunholz for making the pmRFPmars plasmid available. We also thank Dr. Adrian Smith, Mr. Steven Allen and Dr Suat Dervish for their technical assistance and Ms. Mary Rizk and Mr. Jim Qin for animal husbandry. This work was supported by NHMRC grant 1030147 (to A.A., N.F. and W.W.). W.W. is supported by a fellowship from the NSW Cancer Institute. M.J.H. is an NHMRC Senior Research Fellow.

Footnotes

Author contributions

A.A. and W.W. conceived the idea for this project. A.A., R.J., A.J.M. and W.W. wrote the paper. A.A. performed immunological and flow cytometry experiments and assisted with imaging experiments. R.J. designed and conducted intravital and confocal imaging experiments. B.R. conducted flow cytometry and imaging experiments. R.J. and A.J.M. performed sorting experiments for perivascular macrophages. A.J.M. performed qPCR experiments and CBAs. R.J. A.J.M., B.R. and S.T. performed all other experiments. A.J.B. and N.F. generated fluorescent protein expressing bacteria. All authors discussed the results and commented on the paper.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.2769

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4097073

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Article citations

Resilience of dermis resident macrophages to inflammatory challenges.

Exp Mol Med, 56(10):2105-2112, 01 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39349826 | PMCID: PMC11542019

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

α-Hemolysin-mediated endothelial injury contributes to the development of Staphylococcus aureus-induced dermonecrosis.

Infect Immun, 92(8):e0013324, 02 Jul 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38953668

Diving head-first into brain intravital microscopy.

Front Immunol, 15:1372996, 16 May 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38817606 | PMCID: PMC11137164

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Targeting brain-peripheral immune responses for secondary brain injury after ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke.

J Neuroinflammation, 21(1):102, 18 Apr 2024

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 38637850 | PMCID: PMC11025216

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

CNS-associated macrophages contribute to intracerebral aneurysm pathophysiology.

Acta Neuropathol Commun, 12(1):43, 18 Mar 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38500201 | PMCID: PMC10946177

Go to all (161) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

CD36 Is Essential for Regulation of the Host Innate Response to Staphylococcus aureus α-Toxin-Mediated Dermonecrosis.

J Immunol, 195(5):2294-2302, 29 Jul 2015

Cited by: 16 articles | PMID: 26223653 | PMCID: PMC4546912

Antibody-Mediated Protection against Staphylococcus aureus Dermonecrosis: Synergy of Toxin Neutralization and Neutrophil Recruitment.

J Invest Dermatol, 141(4):810-820.e8, 16 Sep 2020

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 32946878 | PMCID: PMC7960571

MyD88 in macrophages is critical for abscess resolution in staphylococcal skin infection.

J Immunol, 194(6):2735-2745, 13 Feb 2015

Cited by: 29 articles | PMID: 25681348

Epic Immune Battles of History: Neutrophils vs. Staphylococcus aureus.

Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 7:286, 30 Jun 2017

Cited by: 73 articles | PMID: 28713774 | PMCID: PMC5491559

Review Free full text in Europe PMC