Abstract

Free full text

The multilayered complexity of ceRNA crosstalk and competition

Abstract

Recent reports have described an intricate interplay among diverse RNA species, including protein-coding messenger RNAs and non-coding RNAs such as long non-coding RNAs, pseudogenes and circular RNAs. These RNA transcripts act as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) or natural microRNA sponges — they communicate with and co-regulate each other by competing for binding to shared microRNAs, a family of small non-coding RNAs that are important post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression. Understanding this novel RNA crosstalk will lead to significant insight into gene regulatory networks and have implications in human development and disease.

In recent years, numerous studies have documented pervasive transcription across 70–90% of the human genome. This was particularly surprising because less than 2% of the total genome encodes protein-coding genes, suggesting that non-coding RNAs represent most of the human transcriptome. Recent reports indicate that aside from around 21,000 protein-coding genes, the human transcriptome includes about 9,000 small RNAs, about 10,000–32,000 long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and around 11,000 pseudogenes1,2. Non-coding transcripts can generally be divided into two major classes on the basis of their size. Small non-coding RNAs have been relatively well characterized, and include transfer RNAs, which are involved in translation of messenger RNAs; microRNAs (miRNAs) and small-interfering RNAs, which are implicated in post-transcriptional RNA silencing; small nuclear RNAs, which are involved in splicing; small nucleolar RNAs, which are implicated in ribosomal RNA modification; PIWI-interacting RNAs, which are involved in transposon repression; and transcription initiation RNAs, promoter upstream transcripts and promoter-associated small RNAs, which may be involved in transcription regulation. lncRNAs can vary in length from 200 nucleotides to 100 kilobases, and have been implicated in a diverse range of biological processes from pluripotency to immune responses3. One of the best-studied and most dramatic examples is XIST, a single RNA gene that can recruit chromatin-modifying complexes to inactivate an entire chromosome during dosage compensation4. However, although thousands of lncRNAs have been identified in the past decade, only a small number have been functionally characterized.

The importance of the non-coding transcriptome has become increasingly clear in recent years — comparative genomic analysis has demonstrated a significant difference in genome utilization among species (for example, the protein-coding genome constitutes almost the entire genome of unicellular yeast, but only 2% of mammalian genomes)5, and the non-coding transcriptome is often dysregulated in cancer6. These observations suggest that the non-coding transcriptome is of crucial importance in determining the greater complexity of higher eukaryotes and in disease pathogenesis7,8. Functionalizing the non-coding space will undoubtedly lead to important insight about basic physiology and disease progression.

Although many reviews have focused on the regulatory mechanisms and functions of lncRNAs3,9, there are many additional implications for the pervasive transcription observed in mammalian genomes. In this Review, we focus on the emerging roles of RNA–RNA crosstalk, which include new layers of gene regulation that involve interactions between diverse RNA species. A classic example of RNA–RNA interactions involves the post-transcriptional regulation of RNA transcripts by miRNAs. As our knowledge of the transcriptome space has expanded, it has become increasingly clear that numerous miRNA-binding sites exist on a wide variety of RNA transcripts, leading to the hypothesis that all RNA transcripts that contain miRNA-binding sites can communicate with and regulate each other by competing specifically for shared miRNAs, thus acting as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs)10–12. miRNA competition thus extends beyond the non-coding transcriptome and potentially confers an additional non-protein-coding function to protein-coding mRNAs. Although it has been proposed that ceRNA crosstalk may be limited to a small subset of transcripts, owing to factors such as miRNA abundance, ceRNA abundance and subcellular localization10,13, the discovery of functional ceRNA regulation in diverse species — including viruses, plants, mice and humans — by multiple independent groups suggests that it may represent a widespread layer of gene regulation14–18. We discuss literature describing the effect of miRNA competition on the regulation of both non-coding and coding RNAs, additional factors that may affect ceRNA activity and potential directions for future studies, as well as the implications of miRNA competition for development and disease.

RNA crosstalk in competitive endogenous networks

Competition between various molecular species to bind to a specific molecular target has been described in multiple contexts, and includes DNA–protein, RNA–protein, RNA–RNA and protein–protein crosstalk. This Review focuses on crosstalk involving RNA–RNA interactions and an additional regulatory layer of RNA–protein interactions.

Protein-RNA competition

RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) are key regulators of multiple post-transcriptional events, including RNA splicing, stability, transport and translation19. Various RBPs may compete to bind to specific target transcripts: the RBP HuR, which generally stabilizes target transcripts; and AUF1, which generally leads to the rapid degradation of target transcripts, have been shown to compete for common target binding sites20,21; and competition between HuR and wild-type TTP for binding to the HuR (also known as Elavl1) transcript has been implicated in HuR regulation and cytoplasmic localization22. Conversely, target transcripts may compete to bind to specific RBPs: competition between GAP43 and β-actin mRNAs for binding to the K-homology (KH)-domain RBP ZBP1 has been shown to affect their exonal localization23.

miRNA-RNA competition

In addition to the protein-coding dimension, molecular competition also extends to regulatory networks comprised exclusively of RNAs, suggesting that sequence competition represents a universal and prevalent form of gene regulation. Two intriguing new players, which add further complexity to RNA crosstalk, are miRNAs and lncRNAs. Experimental evidence has confirmed that competition for miRNAs, small non-coding regulators of gene expression, plays an integral part in the regulation of both lncRNAs14–16,24,25 and mRNAs17,18,26,27. We summarize the background and experimental evidence that supports this competitive RNA crosstalk and discuss potential refinements and directions for future analyses.

Artificial miRNA sponges as miRNA competitors

Several years before the discovery of naturally occurring miRNA sponges, or ceRNAs, various groups described the use of artificial miRNA sponges as effective miRNA inhibitors28–30. These sponges are usually expressed from strong promoters, contain multiple binding sites for an miRNA of interest and have been shown to derepress miRNA targets at least as effectively as chemically modified antisense oligonucleotides30. The efficacy of artificial sponges has been demonstrated for multiple miRNAs both in vitro and in vivo30–34. Artificial miRNA sponges constructed with multiple binding sites for different miRNAs may also be used to study the effect of several miRNAs simultaneously30,32.

Intriguingly, although sponges with perfectly complementary miRNA-binding sites have been shown to be effective29,30,33, ‘bulged sponges’, which include a central bulge and hence bind miRNAs with imperfect complementarity, have been demonstrated to sequester miRNAs with greater efficacy30–33,35,36. This may be partly due to the fact that, unlike perfectly complementary targets, imperfect targets are not immediately degraded and are thus able to reduce miRNA bioavailability until the mRNA is destabilized by other factors31,35. These artificial miRNA sponges will not only be invaluable tools for miRNA loss-of-function studies in vitro and in vivo, but may also provide a new platform for RNA-based therapeutic applications.

Natural miRNA sponges as ceRNAs

It has been proposed that naturally occurring protein-coding and non-coding RNA transcripts can act as endogenous miRNA sponges, or ceRNAs11,12,15. ceRNAs communicate with, and co-regulate, each other by competing to bind to shared miRNAs, thereby titrating miRNA availability. Because ceRNA crosstalk can be deciphered bioinformatically and experimentally, the identification and analysis of ceRNA interactions may allow the systematic functionalization of the non-coding transcriptome, as well as a non-protein-coding function to be attributed to mRNA transcripts, which may be complementary or even distinct from their protein-coding function11.

Non-coding RNAs as ceRNAs

Increasing experimental evidence supports the hypothesis that multiple non-coding RNA species, including small non-coding RNAs, pseudogenes, lncRNAs and circular RNAs (circRNAs) may possess ceRNA activity.

Plant and viral non-coding ceRNAs

One of the first examples of endogenous non-coding miRNA sponges was described in plants15 (Table 1). The non-coding RNA IPS1 from Arabidopsis thaliana has been reported to alter the stability of PHO2 mRNA by sequestering the phosphate starvation-induced miRNA miR-399. In addition, although most miRNA targets in plants are cleaved owing to almost perfect miRNA complementarity, the IPS1 motif contained a mismatched loop at the miRNA cleavage site that abolished transcript cleavage and resulted in effective miR-399 sequestration. Generation of a cleavable IPS1 variant eliminated its inhibitory activity on miR-399. This was consistent with the observations from artificial sponge constructs suggesting that imperfectly complementary ‘bulged sponges’ sequester miRNAs more effectively than perfectly complementary miRNA sponges.

Table 1

List of validated non-coding competing endogenous RNAs

| Non-coding RNA species | Competing endogenous RNAs | Shared microRNAs | Organism | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small non-coding RNA | HSUR1 | FOXO1 | miR-27a | Herpesvirus saimiri | 14 |

| Long non-coding RNA | IPS1 | PHO2 | miR-399 | Arabidopsis thaliana | 15 |

| HULC | PRKACB | miR-372 | Homo sapiens | 25 | |

| linc-MD1 | MAML1 MEF2C | miR-133 miR-135 | Mus musculus and Homo sapiens | 24 | |

| linc-RoR | NANOG OCT4 SOX2 | miR-145 | Homo sapiens | 43 | |

| PTCSC3 | miR-574-5p | Homo sapiens | 41 | ||

| H19 | Let-7 family | Mus musculus and Homo sapiens | 42 | ||

| Pseudogene | PTENP1 | PTEN | miR-17, miR-19, miR-21, miR-26 and miR-214 families | Homo sapiens | 16 |

| KRAS1P | KRAS | Let-7 family | |||

| Pbcas4 | BCAS4 | miR-185 | Mus musculus and Homo sapiens | 39 | |

| Circular RNA | CDR1as/ciRS-7 | miR-7 | Danio rerio, Mus musculus and Homo sapiens | 45, 46 | |

| Sry | miR-138 | Mus musculus and Homo sapiens | 45 | ||

Intriguingly, the primate virus Herpesvirus saimiri has been shown to use a non-coding ceRNA to control host-cell gene expression14. H. saimiri-transformed T cells express several viral non-coding RNAs of unknown function called H. saimiri U-rich RNAs (HSURs). One of these non-coding RNAs, HSUR1, has been found to contain miR-27-binding sites and direct miR-27 degradation in a sequence-specific and binding-dependent manner. The expression of HSUR1 and HSUR2 was shown to correlate with an upregulation of FOXO1 levels, a validated miR-27 target, suggesting that perturbation of miRNA expression by HSURs was able to control host gene expression.

Pseudogene ceRNAs

In humans, the non-coding PTENP1 pseudogene has been reported to regulate levels of its cognate gene, the tumour suppressor PTEN, by competing for shared miRNAs16 (Fig. 1). PTENP1 has been shown to act as a decoy for PTEN-targeting miRNAs, to possess tumour suppressive activity and to be selectively lost in human cancers. An additional dimension to PTENP1-mediated ceRNA regulation was recently out-lined37, whereby two antisense RNAs encoded by the PTENP1 locus α and β were characterized. The β isoform was shown to interact with the PTENP1 transcript through an RNA–RNA pairing interaction, affecting its stability and ceRNA activity37.

Validated interactions (grey arrows) between ceRNAs have been reported, shown here with the respective validated microRNAs (miRNAs). Studies have also identified potential ceRNA interactions (blue arrows) based on the respective validated miRNAs. Validated PTEN ceRNAs described in ref. 26 are not included because the specific miRNAs were not identified.

In addition, overexpression of the KRAS pseudogene KRAS1P 3′ untranslated region (UTR) has been reported to increase KRAS transcript abundance and accelerate cell proliferation. The KRAS1P locus was amplified in various human cancers, and KRAS1P transcript levels positively correlated with KRAS transcript levels in prostate cancer. Taken together, these findings were particularly relevant because they attributed a new function to transcribed pseudogenes, lncRNAs, which have been considered to be biologically inconsequential owing to their inability to be translated into functional proteins. Although transcribed pseudogenes may be expressed at much lower levels than their cognate genes, this is counterbalanced by their high degree of shared sequence homology, which results in the conservation of multiple miRNA-binding sites and allows them to compete for the binding of many shared miRNAs simultaneously. Furthermore, it has been suggested that RNA transcripts that contain premature stop codons, such as pseudogenes, may be subjected to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay38. This rapid turnover may conceivably lead to their low abundance, as well as the increased degradation of bound miRNAs, enhancing their effectiveness as miRNA sponges.

Another example of a pseudogene ceRNA was described by Marques et al., who focused their attention on ‘unitary pseudogenes’, which retain protein-coding capability in the human lineage but lose protein-coding function in the rodent lineage. This allowed the RNA-mediated function of RNAs to be disentangled from their ancestral protein-coding function. The mouse Pbcas4 transcript was validated as a conserved ceRNA for human BCAS4, which downregulated expression levels of the protein-coding transcripts Bcl2, Il17rd, Pnpla3, Shisa7 and Tapbp by acting as a miR-185 decoy39. The preservation of miRNA response elements (MREs) and thus miRNA sponge function of this unitary pseudogene after the loss of its protein-coding function lends support to the hypothesis that ceRNA interactions represent a conserved and biologically relevant mechanism of post-transcriptional gene regulation, which confers an additional non-protein-coding role to protein-coding transcripts.

lncRNA ceRNAs

The complexity and diversity of potential ceRNA interactions have scaled exponentially with the identification of more than 10,000 lncRNAs. Examples are already emerging of lncRNAs as competitive platforms for both miRNAs and mRNAs. HuR-mediated binding of the miRNA let-7 to the long intergenic non-coding RNA lincRNA-p21 was shown to lead to decreased lincRNA-p21 transcipt levels and a concomitant increase in the translation of the lincRNA-p21-associated mRNAs JUNB and CTNNB1 (ref. 40).

Many lncRNAs are known to have low abundance and/or nuclear localization9, which may adversely affect their effectiveness as ceRNAs in steady state conditions. However, it has been shown that thousands of lncRNAs possess cell type-, tissue type-, developmental stage- and disease-specific expression patterns and localization9, suggesting that individual lncRNAs may be potent natural miRNA sponges in certain settings. Two such examples of lncRNA ceRNAs that have emerged, underscoring the importance of these miRNA–lncRNA competitive interactions, are HULC and PTCSC3.

The lncRNA HULC has been identified as one of the most significantly upregulated transcripts in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)25. The HULC transcript was found to contain miR-372-binding sites, and its overexpression could reduce miR-372 expression and activity in the liver cancer cell line Hep3B. HULC’s ceRNA activity forms part of an intricate autoregulatory loop: miR-372 inhibition by HULC reduces translational repression of its target transcript PRKACB, inducing cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) phosphorylation and enhancing CREB-dependent HULC upregulation in liver cancer. Significantly, this observed interaction extended beyond in vitro cell-line data to human clinical samples: miR-372 expression was downregulated in all HCC tissue samples compared with corresponding adjacent normal tissue, consistent with increased HULC expression.

In contrast to HULC, which is upregulated in HCC, PTCSC3 was found to be dramatically downregulated in thyroid cancers. PTCSC3 transfection has been shown to lead to a significant decrease in expression levels of the oncogenic miR-574-5p, as well as growth inhibition, cell-cycle arrest and increased apoptosis in three thyroid cancer cell lines41. These two studies suggest that both the disease-specific upregulation and downregulation of individual lncRNAs, and the resultant changes in ceRNA-mediated interactions, may have profound effects in pathophysiological conditions.

In addition to their roles in various cancers, lncRNA ceRNAs have been implicated in human development. For example, a muscle-specific lncRNA, lincMD1, which is activated on myoblast differentiation and controls muscle differentiation in human and mouse myoblasts through its ceRNA activity, has been identified24. lincMD1 sequestered miR-133 and miR-135, effectively regulating the expression of MAML1 and MEF2C mRNAs, respectively. Importantly, when lincMD1 levels were in excess, the repression of MAML1 and MEF2C could be titrated by increasing expression levels of the respective miRNAs, confirming that the observed regulation was due to direct competition for those specific miRNAs. As MAML1 and MEF2C encode transcription factors known to activate muscle-specific gene expression, these data suggest that ceRNA regulation is of crucial importance in myogenic differentiation. In another study, developmentally regulated lncRNA H19 was found to contain binding sites for the let-7 miRNA family, and thus acted as an effective ceRNA for the very abundant let-7 miRNA, hence modulating the expression of other let-7 target transcripts including Dicer and Hmga2 (ref. 42). The observation that let-7 overexpression could recapitulate the precocious muscle differentiation caused by H19 knockdown provides further evidence of the physiological relevance of ceRNA interactions in this setting.

Sequestration of miRNAs has also been shown to be of functional importance in pluripotent embryonic stem (ES) cells. The lncRNA linc-RoR, which is abundantly expressed in human ES cells and down-regulated during differentiation, has been shown to share regulatory miRNAs with OCT4, SOX2 and NANOG, which are core transcription factors that are essential for ES cell self-renewal43. linc-RoR effectively sequestered miR-145, protecting OCT4, SOX2 and NANOG transcripts from miR-145-mediated suppression. Significantly, this regulation was abolished by the introduction of mutations in the two miR-145-binding sites in linc-RoR, providing further evidence that the observed effect was miR-145 dependent. As linc-RoR transcription is directly regulated by these core transcription factors, these results implicate it in a regulatory feedback loop in ES cells and suggest that its ceRNA function is essential for ES cell pluripotency and self-renewal.

circRNA ceRNAs

About 20 years ago, the predominant transcript of the testis-determining gene Sry in mouse testis was found to be circular44, although the physiological relevance of these RNA circles remained elusive. The recent discovery of competitive RNA–RNA interactions coupled with the extensive complementarity of circRNAs to their linear mRNA counterparts has raised the possibility that these RNA circles may have an integral role in regulatory RNA networks. Recently, a circRNA called CDR1as (also known as ciRS-7)45,46 was identified. This highly stable circRNA contains more than 60 conserved binding sites for miR-7 and hence acts as an effective miR-7 sponge that affects miR-7 target gene activity. In zebrafish, its expression impaired midbrain development in a manner analogous to miR-7 knockdown46. However, this is not an isolated example of circRNAs with ceRNA activity, Sry has also been validated as a miR-138 sponge45. These studies represent the first functional analysis of circRNAs.

Recent bioinformatic and experimental analyses have identified thousands of circRNAs in the mammalian transcriptome, suggesting that circRNAs may in fact represent a new class of ceRNA regulators45–47. Importantly, owing to their high expression levels and increased stability, circRNAs with ceRNAs activity may be exceptionally effective modulators of the crosstalk between linear ceRNAs48. circRNAs such as CDR1as that contain multiple binding sites for the same miRNA may represent a mechanism for sequestering more abundant miRNAs, which would be significantly less susceptible to titration by transcripts that contain only one miRNA-binding site. In addition to their ceRNA function, it is possible that circRNAs may also bind and sequester RBPs, base pair with other RNAs or even produce proteins49.

Taken together, these studies suggest that the analysis of ceRNA crosstalk may provide invaluable insight into the function of diverse species of non-coding RNAs, including lncRNAs, pseudogenes and circRNAs. Furthermore, because any RNA transcript that contains miRNA-binding sites can sequester miRNAs, ceRNA crosstalk also extends beyond the non-coding space to confer a non-protein-coding function to mRNAs.

mRNAs as ceRNAs

The gene with perhaps the most extensively characterized ceRNA network is the important tumour suppressor PTEN. Aside from the non-coding pseudogene PTENP1 (discussed earlier), the PTEN ceRNA network includes multiple protein-coding transcripts (Fig. 1, Table 2).

Table 2

List of validated protein-coding competing endogenous RNAs

| Competing endogenous RNAs | Shared microRNAs | Organism | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTEN | CNOT6L | miR-17 and miR-19 families | Homo sapiens | 17 |

| VAPA | miR-17, miR-19 and miR-26 families | |||

| ZEB2 | miR-25, miR-92a, miR-181 and miR-200b | Homo sapiens and Mus musculus | 18 | |

| ABHD13, CCDC6, CTBP2, DCLK1, DKK1, HIAT1, HIF1A, KLF6, LRCH1, NRAS, RB1, TAF5 and TNKS2 | Homo sapiens | 26 | ||

| PTEN | VCAN | miR-136 and miR-144 | Homo sapiens and Mus musculus | 50 |

| Rb1 | VCAN | miR-144 and miR-199a-3p | ||

| CD34 | miR-133a, miR-144 and miR-431 | 51 | ||

| FN1 | miR-133a, miR-199a-3p and miR-431 | 27,51 | ||

| FN1 | CD44 | miR-491, miR-512-3p and miR-671 | Homo sapiens | 53 |

| Col1α1 | CD44 | miR-328 | ||

| CDC42 | miR-216a, miR-330 and miR-608 | 52 | ||

| HMGA2 | TGFBR3 | Let-7 family | Homo sapiens and Mus musculus | 54 |

| m169 | m169 | miR-27a and miR-27b | Murine cytomegalovirus | 55, 56 |

A combined computational and experimental approach has been used to identify CNOT6L and VAPA as protein-coding transcripts that regulate PTEN transcript and protein expression in a Dicer-dependent manner, antagonize downstream PI(3)K signalling and possess growth-and tumour-suppressive properties17. These genes were also coexpressed with PTEN mRNA in several human cancers and displayed copy number loss in colon cancer. The study demonstrated that previously uncharacterized transcripts could be functionalized, partly through the identification of their ceRNA interactors, and presented a framework for the prediction and validation of ceRNA interactions that is widely applicable to any potential transcript of interest.

One of the first examples linking aberrant ceRNA expression to tumorigenesis in vivo came from the discovery of a significant enrichment of predicted PTEN ceRNAs among genes whose loss accelerated melanomagenesis in a Sleeping Beauty insertional mutagenesis screen in vivo. ZEB2 was subsequently validated as a bona fide PTEN ceRNA that modulated PTEN protein levels in an miRNA-dependent, protein-coding-independent fashion18. Decreased ZEB2 transcript levels activated downstream signalling, enhanced cell transformation and were found to occur frequently in human melanoma and other cancers with low PTEN mRNA expression. These data suggest that the dysregulation of PTEN expression owing to the loss of its ceRNA ZEB2 contributes to the development of melanoma both in vitro and in vivo.

Analysis of gene expression data in glioblastoma in combination with matched miRNA profiles validated 13 PTEN ceRNAs or miR program-mediated post-transcriptional regulatory (mPR) regulators whose locus deletions were predictive of decreased PTEN expression, downregulated PTEN in a 3′ UTR-dependent manner and increased tumour cell growth rates26. When the analysis was significantly extended beyond the binary ceRNA associations described in most other studies, the PTEN ceRNA interactions were found to be part of a post-transcriptional regulatory layer comprising more than 248,000 miRNA-mediated interactions.

The VCAN 3′ UTR has been reported to modulate PTEN levels by sequestering the shared miRNAs miR-144 and miR-136, freeing PTEN mRNA for translation50. In addition to its role as a PTEN ceRNA, VCAN has been shown to modulate the expression of several other genes through miRNA competition (Fig. 1). VCAN was also demonstrated to act as a ceRNA for the cell-cycle regulator RB1 by regulating miR-199a-3p and miR-144 levels, upregulating the expression of this crucial tumour suppressor both in vitro and in vivo50. CD34 and FN1 were validated as two additional VCAN ceRNAs that communicate through interactions with miR-133a, miR-199a-3p, miR-144 and miR-431 (refs 27, 51). As overexpression of the VCAN 3′ UTR in vivo was shown to induce organ adhesion followed by hepatocellular carcinoma development at a later time point, these studies were the first to demonstrate that the perturbation of a non-coding RNA transcript with validated ceRNA function has physiological and pathophysiological relevance in vivo.

Another gene with validated protein-coding ceRNAs is CD44, which encodes a transmembrane glycoprotein that is involved in a wide range of cellular functions52. The CD44 3′ UTR was shown to inhibit cell proliferation, colony formation, tumour growth and enhance cell motility, invasion and adhesion52,53. CD44 regulated levels of CDC42, a Rho-GTPase involved in the control of cell morphology, migration and cell-cycle progression, by binding and sequestering three miRNAs, miR-216a, miR-330 and miR-608. It was also shown to modulate levels of Col1α1 through miR-328 binding and FN1 through miR-512-3p, miR-491 and miR-671 binding. The ceRNA interactions between CD44 and FN1 link CD44, CDC42 and Col1α1 to the broader miRNA–ceRNA network revolving around PTEN and VCAN. This adds another level of complexity to these post-transciptional regulatory associations between multiple transcripts, which play important parts in tumorigenesis (Fig. 1).

A recent study outlined the role of Hmga2’s ceRNA function in promoting lung carcinogenesis54. Hmga2, a non-histone chromosomal high mobility group protein, was shown to be highly expressed in metastatic lung adenocarcinoma and to promote lung cancer progression by sequestering the abundant let-7 family of miRNAs. The TGF-β co-receptor Tgfbr3 was identified as a putative Hmga2 ceRNA, and Tgfbr3-driven TGF-β signalling was demonstrated to be largely necessary for Hmga2-mediated lung-cancer progression. The discovery that the primary function of a protein-coding transcript is to act as an oncogenic ceRNA for a very abundant miRNA, largely independently of its protein-coding function, provides further support for the hypothesis that the ceRNA function of multiple protein-coding transcripts is of fundamental importance in cancer progression.

A viral mRNA that functions as a natural miRNA sponge in host cells has also been described. Intriguingly, this mRNA was found to sequester the same miRNA reported to be downregulated by HSUR1-binding in H. saimiri, suggesting that ceRNA-mediated regulation of this miRNA may be a conserved mechanism for controlling host gene expression in multiple viruses. Two studies independently showed that the highly abundant murine cytomegalovirus mRNA m169 acted as a natural miRNA sponge in host cells by binding to miR-27 through a single site in its 3′ UTR, hence directing its degradation55,56. Importantly, m169-mediated miR-27 regulation is another example of the importance of ceRNA function in vivo: disruption or replacement of the miRNA target site resulted in significant viral attenuation in multiple organs, suggesting that this miRNA-sponge interaction is crucial for efficient replication in vivo.

Predicting ceRNA crosstalk

ceRNA crosstalk depends on the MREs located on each transcript, which combinatorially form the foundation of these co-regulatory interactions11. Prediction of ceRNA crosstalk is thus dependent on the identification of MREs on the relevant transcripts of interest. Several miRNA-target prediction algorithms, including TargetScan, miRanda, rna22 and PITA, have been successfully used to identify ceRNA interactions. However, miRNA target identification is challenging owing to the imperfect nature of base pairing between an miRNA and its target, and the rules of targeting are not completely understood57. Further development and optimization of these algorithms will undoubtedly improve subsequent predictions of ceRNA interactions.

A database of predicted ceRNA interactions (ceRDB), which was generated by examining the co-occurrence of MREs on a genome-wide basis58, has recently been compiled. Predicted miRNA–mRNA target interactions were obtained from TargetScan release 5.2, and interaction scores were defined for each mRNA by adding the total number of MREs that overlap with the miRNAs for the mRNA of interest; these interaction scores were then used to rank the predicted potential ceRNAs. Although this analysis is limited to the 3′ UTRs of protein-coding transcripts, it still represents a useful tool for the identification of putative ceRNA crosstalk.

As an alternative to in silico prediction strategies, recently developed high-throughput biochemical techniques, which identify endogenous miRNA–target interactions can be used. Examples of these experimental methods include high-throughput sequencing of RNA isolated by crosslinking immunoprecipitation (HITS-CLIP)59 and photoactivatable- ribonucleoside-enhanced crosslinking and immunoprecipitation (PAR-CLIP)60. HITS-CLIP analysis of argonaute-bound miRNA–mRNA complexes has generated genome-wide interaction maps for specific miRNAs61. Recently, integration of HITS-CLIP data was shown to enhance miRNA target predictions by more than 20-fold over computational approaches alone, and mRNA–miRNA predictions have been used to identify candidate ceRNA interactions in the regenerating liver62. PAR-CLIP is a modification of the HITS-CLIP methodology with improved RNA recovery, which is able to indicate the exact targeting site more precisely. A complementary approach to these is MS2-tagged RNA affinity purification (MS2-TRAP), which can be used to identify all miRNAs associated with a target transcript in a particular cellular context63. Harnessing these experimental techniques will provide further insight into ceRNA regulation beyond that which is possible with in silico target predictions.

Additional considerations for ceRNA activity

Although multiple examples of ceRNA interactions have been described, little is known about the molecular conditions necessary for optimal ceRNA activity. Considerations such as the abundance of key players, potential interplay with RBPs and RNA editing may have profound effects on ceRNA crosstalk.

Abundance of miRNAs, ceRNAs and argonaute

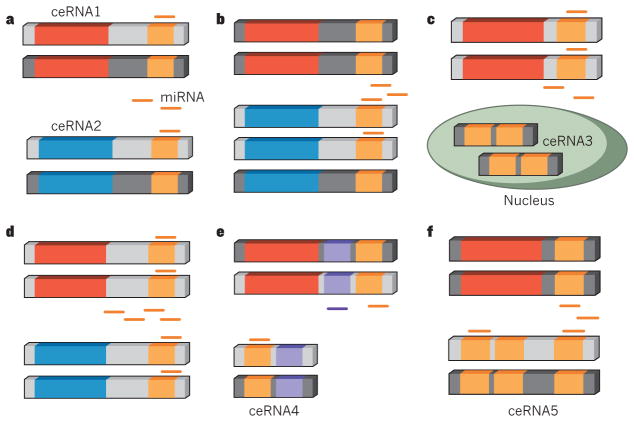

Various factors, including miRNA- and ceRNA-expression levels and subcellular localization, the number of shared miRNAs and MREs, as well as binding affinity of the shared MREs have been suggested to contribute to ceRNA effectiveness10,11,64 (Fig. 2). For example, it has been hypothesized that miRNA–RNA competition would apply only to a small subset of miRNAs whose abundance and corresponding target abundance fell within a narrow range, as the expression of competitor RNAs would have little impact on regulation by highly abundant miRNAs, and low abundance miRNAs would be unlikely to contribute much to gene regulation because a minimal number of targets would be bound at any given time13.

a, Steady state levels of ceRNA1 (protein-coding region shown in red) and ceRNA2 (protein-coding region shown in blue). Active repression by miRNAs is shown in light grey. b, If expression of ceRNA2 increases, this will increase expression of ceRNA1. c, ceRNA3 has a different subcellular localization from ceRNA1, and may be a less effective ceRNA than ceRNA2. d, Increased expression of the shared miRNA will increase repression of both ceRNA1 and ceRNA2. e, ceRNA4 contains miRNA response elements (MREs, purple and orange) for multiple shared miRNAs, and may be a more effective ceRNA than ceRNA2. f, ceRNA5 contains more MREs than ceRNA2 and may be a more effective ceRNA.

Recent studies have further refined the dynamics and constraints of ceRNA crosstalk. Optimal conditions for ceRNA activity in silico have been determined using a mathematical mass-action model, and these were confirmed experimentally using PTEN and its validated ceRNA VAPA65. In addition, a minimal rate equation-based model to describe crosstalk between ceRNAs at steady state has been developed66. The relative abundance of both ceRNAs and miRNAs, their stoichiometry, the number of shared MREs and indirect interactions were shown to be crucial determinants of ceRNA cross-regulation. For instance, both studies found that ceRNA crosstalk was optimal when the transcript abundance of miRNAs and ceRNAs within a network were near equimolarity. ceRNA crosstalk would be minimal when ceRNA transcript abundance vastly exceeded that of miRNAs owing to the limited number of miRNAs available to repress their targets, as well as when miRNA transcript abundance vastly exceeded that of ceRNAs owing to maximal repression of most target transcripts.

Strong correlations in network connectivity that enhance ceRNA crosstalk have also been observed66: ceRNA interactions may be mediated by a large number of miRNA species that individually have weak effects on their respective targets; and ceRNA regulation may be symmetrical (two ceRNAs reciprocally regulate each other) or asymmetrical (one ceRNA regulates another but not vice versa). Intriguingly, a separate study65 found that ceRNA and transcription factor networks were intricately intertwined and, with optimal molecular conditions, changes in the levels of a single ceRNA could affect integrated ceRNA and transcriptional networks.

Another potential rate-limiting determinant of ceRNA crosstalk is the abundance of argonaute, the catalytic component of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). A mathematical model constructed to analyse changes in gene expression caused by competition between small RNAs, showed that competition for argonaute binding occurs within an intermediate range of argonaute abundance, whereby lower amounts of argonaute result in stronger competition67. Surprisingly, this model also revealed that when argonaute is highly abundant, the overexpression of one miRNA decreases expression levels of its own targets as well as the targets of other miRNAs. This is a result of the overexpressed miRNA binding to targets that share MREs for that miRNA and other miRNAs, freeing the other miRNAs to regulate other target genes.

Interplay between miRNAs and RBPs

As already discussed, in addition to competing for shared miRNAs, RNA transcripts may also compete for shared RBPs. These two regulatory functions are not always distinct and may in fact be intricately intertwined. RBP and miRNA crosstalk may be either direct, whereby they compete or cooperate for binding to a specific binding site, or indirect, whereby RBP binding changes the RNA secondary structure and thus alters accessibility to miRNA-binding sites. For example, competition between the stabilizing RBP HuR and miRNAs usually enhances gene expression if the HuR–mRNA association is predominant, and cooperation between HuR and miRNAs typically reduces expression of the target mRNA68. HuR has been shown to compete with miR-122, miR-548c, miR-494, miR-16 and miR-331-3p for binding to the CAT1, TOP2A, NCL, COX2 and ERBB2 mRNAs, respectively69–73. Conversely, HuR has been demonstrated to recruit the let-7 RISC and miR-19 RISC to repress the expression of c-Myc and RhoB transcripts, respectively74,75. Other examples of miRNA and RBP crosstalk include a study that reported that the germ-cell-specific RBP Dnd1 bound mRNAs and blocked miRNA access to their target sites76; and another that demonstrated that competition between miR-4661 and TTP for binding to the ARE sequence in IL-10 mRNA protected IL-10 from TTP-mediated degradation77. The exact RBP species present in a specific biological setting and their relative abundance may thus have a profound impact on miRNA and ceRNA regulatory networks.

RNA editing

RNA editing refers to a post-transcriptional processing mechanism producing an RNA sequence that is different from its template DNA78. The most prevalent type of RNA editing in higher eukaryotes is the hydrolytic deamination of adenosine to inosine in double-stranded RNA substrates (A to I RNA editing). As inosine has the same base-pairing properties as guanosine, it pairs preferentially with cytidine instead of uridine. This effectively alters the sequence and base-pairing properties of the edited RNA, and may affect ceRNA regulation in two ways. First, editing of miRNA transcripts may repress biogenesis, affect strand stability or even alter their target spectrum79; second, editing of target RNA transcripts may abolish or create new miRNA-binding sites. One study reported the tissue-specific A to I editing of miR-376 cluster transcripts, and identified one editing site located in the middle of the ‘seed’ region, which is crucial for miRNA–target binding. Subsequently, the predominantly expressed edited miR-376 isoforms were shown to silence a different set of target genes compared with unedited miR-376 (ref. 80). This phenomenon is probably not limited to miR-376. In a second study, it was suggested that up to 16% of all human primary miRNAs may be targeted by ADARs81. A to I RNA editing was initially thought to be restricted to the coding regions of a few genes79, but recent genome-wide screening coupled with bioinformatic analyses has revealed numerous editing sites that are frequently located in non-coding repetitive RNA sequences78. As 85% of pre-mRNAs are predicted to be subject to A to I RNA editing, with most target sites located in introns and UTRs82,83, this phenomenon may significantly increase the complexity of elucidating ceRNA interactions.

Implications for human disease

Many of the genes with known ceRNA interactors identified so far have been implicated in human disease. For example, PTEN is a potent tumour suppressor gene that is frequently disrupted in multiple cancers and governs multiple cellular processes, including survival, proliferation, energy metabolism and cellular architecture84; HULC is the most upregulated gene in HCC and has been shown to regulate several genes involved in liver cancer25,85; T cells that are infected with HSUR1-expressing H. saimiri cause aggressive leukaemias and lymphomas14 and linc-MD1 expression in primary muscle cells isolated from patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy has been shown to result in partial mitigation of the correct timing of the differentiation program24. This suggests that ceRNA crosstalk is not only of fundamental importance in physiological conditions, but is also crucially relevant in various pathophysiological states.

In addition to the genomic amplifications, deletions, mutations and epigenetic modifications that dysregulate crucial gene function and result in disease pathogenesis, aberrant changes in ceRNA regulation may also contribute to disease initiation and progression. First, changes in the expression levels of ceRNA transcripts represent an additional mechanism for regulating the levels of key disease genes, such as tumour suppressors or oncogenes. ceRNA crosstalk may thus allow the functional characterization of transcripts with no other known function on the basis of their ceRNA activity. This is of particular importance because although many lncRNAs (for example, HULC) are expressed at low levels in steady state conditions, their expression is known to be dysregulated in various diseases6. Second, it has been shown that, compared with non-transformed cell lines, cancer cells in vitro often express mRNAs with shorter 3′ UTRs, which result from alternative cleavage and polyadenylation86. This phenomenon has also been reported in primary breast and lung cancer tumours87. Transcripts with shorter 3′ UTRs are not only subject to reduced miRNA regulation in cis, but will have diminished ability to act as ceRNAs through miRNA crosstalk in trans. Third, the altered expression of transcript variants of many genes through alternative splicing or differential use of initiation and/or stop codons has been linked to disease11,88,89. These variants may produce proteins with different structures and functions, but may also introduce or eliminate MREs, and thus affect ceRNA activity. Fourth, chromosomal translocations are frequent events in cancer that may contribute to tumorigenesis. These events result in the production of various fusion proteins, but could also potentially affect ceRNA regulation owing to misexpression of 3′ UTRs under the control of non-endogenous promoters11. Finally, SNPs (single-nucleotide polymorphisms) associated with various diseases may create, modify or destroy MREs. For example, SNPs in genes related to Alzheimer’s disease may potentially dysregulate miRNA and ceRNA networks and thus contribute to aberrant gene expression in Alzheimer’s disease90. These observations suggest that ceRNA network interactions may have a role in determining the effectiveness of RNA-directed therapies91.

Future perspectives

As ceRNA research is still in its infancy, there are only a handful of validated examples of each existing class of ceRNAs, such as mRNAs, small non-coding RNAs, lncRNAs, pseudogenes and the recently described circRNAs (Tables 1 and and2).2). Although research should certainly focus on the identification of more ceRNAs in these categories to ascertain whether ceRNA crosstalk represents a widespread network of RNA regulation, another exciting avenue for future work is the discovery of new classes of ceRNAs. For example, argonaute proteins have been found to interact with rRNAs and tRNAs, raising the possibility that these abundant, stable, small RNA species may also act as ceRNAs92. Intriguingly, 3′ UTRs that are expressed independently of their associated protein-coding sequences have been described in humans, mice and flies, suggesting that they may represent another new class of ceRNAs93.

Refinements in ceRNA prediction strategies will facilitate the discovery of additional ceRNA interactions. One limitation of current ceRNA prediction strategies is that they do not factor in miRNA and potential ceRNA expression levels. This is especially crucial as miRNAs and ceRNAs are known to have temporal, spatial and disease-specific expression patterns, and it has been suggested that ceRNA crosstalk applies mainly to a subset of ceRNAs and miRNAs whose cellular concentration and target abundance fall within a specific range of values10,11,13. A precise understanding of miRNA and ceRNA abundance is thus essential for deconvoluting any ceRNA network of interest in a particular context. Although paired miRNA and mRNA expression profiles have been integrated with bioinformatic target predictions to refine potential ceRNA interactions17,18,26, they have been based mainly on relative quantitation methods such as microarray and quantitative PCR (polymerase chain reaction) analysis that are subject to variations in probe binding and affinity. Techniques such as RNA sequencing that allow the quantitation of absolute levels of both ceRNA and miRNA transcript abundance will allow a more precise determination of ceRNA effectiveness. In addition, the integration of methods such as HITS-CLIP and PAR-CLIP, which allow the biochemical identification of endogenous miRNA–target interactions on a transcriptome-wide level in specific cellular contexts, will further refine ceRNA prediction strategies that currently depend mainly on in silico bioinformatic miRNA predictions.

Another limitation of current ceRNA prediction methods is their focus on crosstalk between canonical MREs that are located exclusively on the 3′ UTRs of target transcripts. A number of recent studies have suggested that miRNA regulation is not limited to canonical 3′ UTR targets. For example, several groups have demonstrated that a significant proportion of MREs in humans are non-canonical94,95, and others have shown that effective miRNA targeting can occur outside the 3′ UTR96,97. Furthermore, it has been shown that miRNA binding does not always result in target downregulation98; 5′ UTR structure has been demonstrated to be a crucial determinant of miRNA-dependent regulation99; and, for dynamically recruited miRNAs, changes in overall miRNA expression were found to not always be correlated with miRNA recruitment to the RISC62. These new insights into miRNA function should be incorporated into future ceRNA prediction analysis, and may potentially add further complexities to the dynamics of ceRNA regulation and significantly expand the realm of potential ceRNA activity.

Although most of the ceRNA interactions identified so far have been between binary partners, there is increasing evidence that ceRNAs crosstalk in large interconnected networks; and that, in addition to direct interactions through shared miRNAs, secondary indirect interactions may also have a profound effect on ceRNA regulation26,65. For example, PTEN expression has been shown to be regulated by ceRNA interactions between PTEN and its ceRNAs PTENP1, CNOT6L, VAPA, VCAN and ZEB2 (Fig. 2). In addition, indirect ceRNA crosstalk (for example, between VCAN and FN1), as well as secondary interactions between PTEN ceRNAs (for example, between PTENP1, CNOT6L and VAPA mediated by the miR-17 and miR-19 families) may also contribute significantly to the effectiveness of ceRNA regulation. Future ceRNA research should extend beyond the identification of binary ceRNA interactions and include network analysis of potential intertwined miRNA and ceRNA networks.

The conservation of ceRNA crosstalk in multiple organisms, including plants, zebrafish, mice, humans and viruses, suggests that it may represent an important widespread layer of RNA regulation. As already discussed, this regulation is not limited to non-coding RNAs, it also encompasses protein-coding mRNAs. Recently, the genome of the carnivorous bladderwort Utricularia gibba was found to contain a typical number of protein-coding genes, but significantly less non-genic DNA100, providing one example whereby a large non-coding genome is not essential for complex life. This presents an interesting opportunity to study potential RNA regulatory networks that involve mainly mRNAs and a much smaller non-coding transcriptome that consists of non-coding RNAs encoded in genic DNA such as circRNAs and antisense non-coding RNAs.

In summary, analysis of ceRNA interactions and crosstalk in intertwined networks may represent a robust platform to methodically functionalize non-coding transcripts on the basis of competition for shared miRNAs. Furthermore, the analysis sheds light on the non-coding function of protein-coding transcripts, and may uncover regulatory networks that have been overlooked by conventional protein-coding studies. To fully understand and appreciate the impact of ceRNA crosstalk on physiological and pathophysiological conditions, it will be of crucial importance to integrate these miRNA–RNA competitive networks with other competitive regulatory networks such as protein–RNA crosstalk. Although the full extent of ceRNA networks remains to be determined, this miRNA–RNA competition is a new post-transcriptional layer of endogenous competitive gene regulation, which has exciting implications for multiple basic biological systems, pathophysiological conditions and the development of new therapeutic approaches for cancer and other diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. M. Tan, R. Taulli, F. Karreth and other members of the Pandolfi laboratory for helpful discussions and critical review of the manuscript. Y.T. received a Special Fellow Award from The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. P.P.P. was supported by US National Institutes of Health grant R01 CA-82328.

Footnotes

Author Information Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints. The authors declare no competing financial interests. Readers are welcome to comment on the online version of this article at www.nature.com/emoqic.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12986

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4113481

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1038/nature12986

Article citations

Methyltransferase-like 3 represents a prospective target for the diagnosis and treatment of kidney diseases.

Hum Genomics, 18(1):125, 14 Nov 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39538346 | PMCID: PMC11562609

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Aberrant NSUN2-mediated m5C modification of exosomal LncRNA MALAT1 induced RANKL-mediated bone destruction in multiple myeloma.

Commun Biol, 7(1):1249, 02 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39358426 | PMCID: PMC11446919

LncRNA PTPRG-AS1 Promotes Breast Cancer Progression by Modulating the miR-4659a-3p/QPCT Axis.

Onco Targets Ther, 17:805-819, 04 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39380914 | PMCID: PMC11460282

Integration Analysis of miRNA Circulating Expression Following Cerebellar Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation in Patients with Ischemic Stroke.

Biochem Genet, 21 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39304639

Bibliometric analysis of microRNAs and Parkinson's disease from 2014 to 2023.

Front Neurol, 15:1466186, 25 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39385824 | PMCID: PMC11462628

Go to all (2,201) article citations

Other citations

Data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Computational Identification of Cross-Talking ceRNAs.

Adv Exp Med Biol, 1094:97-108, 01 Jan 2018

Cited by: 28 articles | PMID: 30191491

Review

Competing endogenous RNA: the key to posttranscriptional regulation.

ScientificWorldJournal, 2014:896206, 02 Feb 2014

Cited by: 166 articles | PMID: 24672386 | PMCID: PMC3929601

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

starBase v2.0: decoding miRNA-ceRNA, miRNA-ncRNA and protein-RNA interaction networks from large-scale CLIP-Seq data.

Nucleic Acids Res, 42(database issue):D92-7, 01 Dec 2013

Cited by: 3013 articles | PMID: 24297251 | PMCID: PMC3964941

A potential role of extended simple sequence repeats in competing endogenous RNA crosstalk.

RNA Biol, 15(11):1399-1409, 05 Nov 2018

Cited by: 13 articles | PMID: 30381983 | PMCID: PMC6284579

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NCI NIH HHS (3)

Grant ID: R01 CA082328

Grant ID: R01 CA170158

Grant ID: R01 CA-82328