Abstract

Background

Workplace violence is one of the factors which can strongly reduce job satisfaction and the quality of working life of nurses. The aim of this study was to measure nurses' exposure to workplace violence in one of the major teaching hospitals in Tehran in 2010.Methods

We surveyed the nurses in a cross-sectional design in 2010. The questionnaire was adapted from a standardized questionnaire designed collaboratively by the International Labor Office (ILO), the International Health Organization (IHO), the International Council of Nurses (ICN), and the Public Services International (PSI). Finally, in order to analyze the relationships among different variables in the study, T-test and Chi-Square test were used.Results

Three hundred and one nurses responded to the questionnaire (a response rate of 73%). Over 70% of the nurses felt worried about workplace violence. The participants reported exposure to verbal abuse (64% CI: 59-70%), bullying-mobbing (29% CI: 24-34%) and physical violence (12% CI: 9-16%) at least once during the previous year. Relatives of hospital patients were responsible for most of the violence. Nurses working in the emergency department and outpatient clinics were more likely to report having experienced violence. Nurses were unlikely to report violence to hospital managers, and 40% of nurses were unaware of any existing policies within the hospital for reducing violence.Conclusion

We observed a considerable level of nurse exposure to workplace violence. The high rate of reported workplace violence demonstrates that the existing safeguards that aim to protect the staff from abusive patients and relatives are inadequate.Free full text

Nurses exposure to workplace violence in a large teaching hospital in Iran

Abstract

Background: Workplace violence is one of the factors which can strongly reduce job satisfaction and the quality of working life of nurses. The aim of this study was to measure nurses’ exposure to workplace violence in one of the major teaching hospitals in Tehran in 2010.

Methods: We surveyed the nurses in a cross-sectional design in 2010. The questionnaire was adapted from a standardized questionnaire designed collaboratively by the International Labor Office (ILO), the International Health Organization (IHO), the International Council of Nurses (ICN), and the Public Services International (PSI). Finally, in order to analyze the relationships among different variables in the study, T-test and Chi-Square test were used.

Results: Three hundred and one nurses responded to the questionnaire (a response rate of 73%). Over 70% of the nurses felt worried about workplace violence. The participants reported exposure to verbal abuse (64% CI: 59-70%), bullying-mobbing (29% CI: 24-34%) and physical violence (12% CI: 9-16%) at least once during the previous year. Relatives of hospital patients were responsible for most of the violence. Nurses working in the emergency department and outpatient clinics were more likely to report having experienced violence. Nurses were unlikely to report violence to hospital managers, and 40% of nurses were unaware of any existing policies within the hospital for reducing violence.

Conclusion: We observed a considerable level of nurse exposure to workplace violence. The high rate of reported workplace violence demonstrates that the existing safeguards that aim to protect the staff from abusive patients and relatives are inadequate.

Introduction

Nurses provide a great amount of direct service to the patients and have a pivotal role in the quality of services provided for the patients. Despite the importance of the role of nurses, health systems and specially hospitals, have been unable to ensure the safety of frontline nurses against workplace violence, which is important since they are in close contact with the patients and their relatives (1–3). Workplace violence against healthcare staff is commonly reported from different countries (4-6). International reports demonstrate that around 10-50% healthcare staff are exposed to violence every year and in certain settings this rate may reach over 85% (2). Violence against healthcare staff, including nurses, may be increasing (2,7,8).

Generally, certain factors increase the exposure risk of nurses to workplace violence in comparison with other groups. These factors include close interaction with patients and their family, working at night, the high level of stress in clinical care settings, working in environments that lack an adequate number of nurses proportional to the services expected from them (resulting in stressful conditions for patients as well as the staff), dominance of the female gender among nurses, lapses in workplace security in most hospitals, transfers between wards, stressful conditions for patients’ relatives (e.g. while waiting to visit a doctor), and at the end of the shifts, when nurses are preparing to ‘leave their patients’ (3,9,10). Workplace violence can be defined as: “Incidents where staff are abused, threatened or assaulted in circumstances related to their work, including commuting to and from work, involving an explicit or implicit challenge to their safety, well-being or health” (11).

Workplace violence is categorized into two main groups: physical, and mental or psychological, including verbal abuse, bullying and mobbing as well as sexual and racial abuse that may overlap both groups (2,12). Workplace violence contributes to a reduced level of efficiency and productivity in healthcare, has a negative impact on the nurses’ quality of working life, job satisfaction levels and their willingness to stay in the job, may result in increased stress levels and absenteeism, can result in chronic fatigue and sleep disorder, and negatively affects the quality of patient care (10,12–15).

Increased exposure to workplace violence or fear of violence reduces job satisfaction and organizational commitment. In general, fear is one of the important consequences of violence which acts as a mediator for decreased job satisfaction and increased stress symptoms (16,17). Workplace violence is associated with stress and work strain. Sometimes this connection is circular. Work strain and stress are also causes of workplace violence. Increased negative stress increases the likelihood of violence, burnout, suicide and even murder. The relationship between stress/violence is usually mediated, and the relationship between violence/stress is direct (14,18–20). Violence may also directly affect nurses’ quality of life and result in different physical or psychological manifestations of illness (6,21,22). Workplace violence is normally associated with mental disorders, and it can be limited by factors such as job control, social protection and justice (23,24). The costs of workplace violence on people, work environment and society are substantial, although further studies are required (11–13).

Methods

We conducted this descriptive, cross-sectional study in Tehran in the summer of 2010. The study population included all the nurses working in a major teaching hospital affiliated with the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS).

The total number of nurses registered with the hospital was 493, of which number we only had access to 413. The reasons for lack of access to nurses included: recent retirement or discontinuation of contracts, maternity or annual leave, secondment to other facilities, or leave for further education.

In this study, data was collected using a standard questionnaire that was adapted from a standardized questionnaire designed collaboratively in 2003 by the International Labor Office (ILO), the World Health Organization (WHO), the International Council of Nurses (ICN), and the Public Services International (PSI) (11,25).

We translated the questionnaire to Farsi (Persian). The face validity of the translated questionnaire was assessed by five academics and experts as well as five nurse supervisors and matrons. We conducted this procedure in an iterative manner so that all the experts were satisfied with the translation, and its concordance with the original text.

The questionnaire was sent to 413 nurses working in the hospital. The questionnaires were anonymous, and completion was not compulsory. This questionnaire contained 78 questions (75 closed and 3 open–ended questions) categorized in to five sections: demographic data, physical violence, psychological violence (verbal abuse, bullying, sexual harassments, racial harassment), employer role in violence control, opinions on work place violence. While adapting the questionnaire to the cultural settings in Iran, questions on racial abuse (which is extremely rare in Iran) and sexual abuse (which is a culturally sensitive topic) were excluded from the study.

Two previous studies in Iran (both published in Farsi) conducted in Tabriz and in a separate hospital in Tehran had used a translated version of the questionnaire (26,27).

We analyzed the data using descriptive univariate analyses including Student’s T-tests and Chi-Square tests.

Results

Of 413 nurses, 73 nurses did not participate in the study and 39 nurses returned the questionnaire unanswered. Hence, a total of 301 nurses answered the questionnaire (a response rate of 73%). The average age of the respondents was 34 years (SD: 8, range: 23–53). Of the respondents 90% were female and 59% were married. 45% of the respondents had a work experience of over 10 years. The biggest proportion of nurses participating in the study worked in the internal wards. Over 70% of the nurses felt worried about workplace violence, and 20% mentioned that they were extremely worried about violence (Table 1).

Table 1

| Wards | Level of feeling worried about workplace violence | Total | ||||

| Not at all worried | Little worried | Worried | Very worried | Extremely worried | ||

| Number (%) | Number (%) | Number (%) | Number (%) | Number (%) | Number (%) | |

| Clinic/outpatient | 3 (21.43) | 4 (28.63) | 3 (21.41) | 1 (7.11) | 3 (21.42) | 14 (100) |

| General medicine | 5 (7.91) | 13 (20.62) | 25 (39.71) | 10 (15.88) | 10 (15.88) | 63 (100) |

| General surgery | 5 (11.11) | 9 (20.00) | 19 (42.20) | 7 (15.58) | 5 (11.11) | 45 (100) |

| Emergency | 1 (2.21) | 6 (12.98) | 9 (19.61) | 12 (26.11) | 18 (39.09) | 46 (100) |

| Operation room | 4 (12.11) | 8 (24.22) | 10 (30.32) | 4 (12.11) | 7 (21.24) | 33 (100) |

| ICU | 4 (9.80) | 6 (14.56) | 15 (36.54) | 12 (29.30) | 4 (9.80) | 41 (100) |

| Others | 5 (11.58) | 7 (16.29) | 15 (34.88) | 6 (13.95) | 10 (23.30) | 43 (100) |

| Total | 27 (9.51) | 53 (18.59) | 96 (33.69) | 52 (18.21) | 57 (20.00) | 285 (100) |

ICU= Intensive Care Unit

The highest proportion of worry was reported by nurses working in the emergency department, where over 60% of nurses reported being ‘very worried’ or ‘extremely worried’ about work place violence.

Sixty nine percent of the participants reported at least one type of workplace violence within the past year. According to this research, the most common types of violence were verbal abuse (64% 95% CI: 59–70 ), followed by bullying-mobbing (29% 95% CI: 24–34 ) and physical violence (12% 95% CI: 9–16 ) with most of the threat coming from the patients’ relatives (Table 2).

Table 2

| Physical violence | Verbal abuse | Bullying-mobbing | |||||

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | ||

| Exposure with violence | Yes | 37 | 12.29 | 193 | 64.09 | 87 | 28.90 |

| No | 264 | 87.71 | 108 | 35.91 | 214 | 71.10 | |

| Aggressors | Patient | 11 | 30.56 | 54 | 27.95 | 25 | 30.53 |

| Relative of patient | 24 | 66.65 | 110 | 56.96 | 43 | 52.42 | |

| Staff | 1 | 2.79 | 16 | 8.33 | 7 | 8.53 | |

| Management | - | - | 6 | 3.11 | 2 | 2.40 | |

| External colleague | - | - | 1 | 0.54 | - | - | |

| General public | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1.20 | |

| Other | - | - | 6 | 3.11 | 4 | 4.92 | |

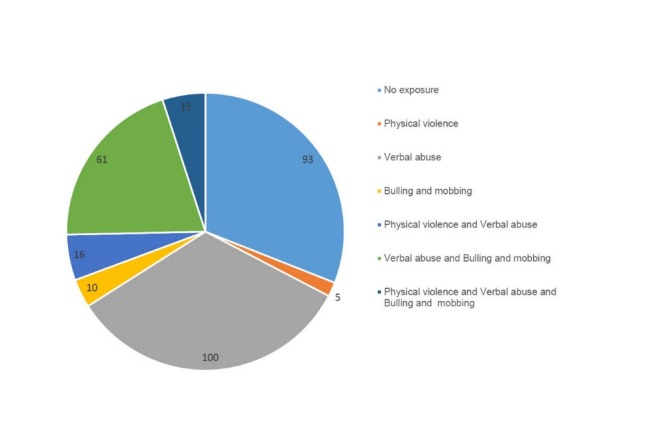

The number of nurses that had not faced any form of violence in their workplace was 31% (Figure 1).

The most reported reaction to the violence was to invite the aggressor to calm down and avoid violence. In most cases, nurses considered the reporting of violence to responsible bodies and speaking about the event as useless and ineffective, and hence they did not report the incidents. Forty percent of the nurses cited that in their opinion the managers did not have any special policy towards security measures in workplace.

Findings show that there is a meaningful relationship between the wards that the nurses were working in and the rate of exposure to physical violence (P<0.01). The most frequently reported exposures to physical violence were reported to have occurred in clinics or outpatient wards (29%) and the emergency department (26%) respectively. Nurses working in the management section, operating rooms and incentive care units reported the lowest incidents of violence (5%). Similar patterns were observed for exposure to verbal abuse (P=0.02).

We also observed that there was a statistically significant relationship between exposure to bullying and mobbing in the workplace and gender, so that women reported higher rates of bullying and mobbing (30.71% versus 10.32%, respectively, P=0.03). No significant relationship was observed between age and exposure to violence (Table 3). Work experience was modestly linked with physical violence, so that nurses with less than 10 years of experience reported more physical violence (Table 3).

Table 3

| Probable relative factors | Type of violence | |||||

| Physical violence | Verbal abuse | Bullying and mobbing | ||||

| Yes (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | No (%) | |

| Age | ||||||

| Less than 35 | 25 (15.00) | 142 (85.00) | 112 (67.11) | 55 (32.89) | 44 (26.29) | 123 (73.71) |

| 35 or more | 12 (9.41) | 116 (90.59) | 78 (60.91) | 50 (39.09) | 41 (32.00) | 87 (68.00) |

| Work experience | ||||||

| Less than 10 years | 27 (16.61) | 136 (83.39) | 110 (67.50) | 53 (32.50) | 45 (27.58) | 118 (72.42) |

| More than 10 years | 9 (6.68) | 125 (93.32) | 79 (59.00) | 55 (41.00) | 41 (30.61) | 93 (69.39) |

*Association between work experience and physical violence was statistically significant (P<0.05). All other relations were non-significant.

Discussion and Conclusion

Using a standard questionnaire frequently used for assessing workplace violence in different countries, we demonstrated that a similarly high proportion of nurses reported exposure to workplace violence within the past year. As expected, verbal abuse (69%) followed by bullying and mobbing (29%) and physical violence (12%) were the most commonly reported types of violence.

Previous studies that had taken place in Iran reported similar trends such as: 72% of nurses in a hospital experienced verbal abuse in Tabriz over the course of a year, 87% in a hospital in Tehran and 95% in a hospital in Mazandaran (4,6,10,26,28–30).

All of these suggest that a coherent program to provide support for nurses (and other staff) and prevent workplace violence is essential and should be considered a priority. Nurses’ exposure to verbal abuse is significant and considerable. Based on researches carried out in Turkey, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, the most prevalent violence against nurses were verbal abuse and bullying and mobbing, physical violence; sexual and racial abuse respectively (1,2,15). Similarly, case studies in Australia, Brazil, and Bulgaria hospitals demonstrated that the verbal abuse rate was very prevalent compared to the other types of workplace violence, which is consistent with our study (31).

Previous studies conducted in Iran and several countries reported that in most cases, patients and their relatives perpetrated violence (1–3,10,15,28,32). In our study, there was almost twice as much violence reported by patients’ relatives as reported by the patients themselves. A similar finding was reported by recent studies in Iran (10,28).

This is an important feature, and as it may be more feasible to prevent violence by relatives, this detail should be given full attention in any plan aiming to reduce workplace violence in hospitals. Violence occurring by others (colleagues, the general public) was rare, similar to other studies.

The presence of a significant relationship between the hospital wards and the rate of verbal abuse was consistent with studies from Turkey and Hong Kong (2,3). In agreement with the findings of an Australian study, the less experienced nurses were more exposed to physical violence (33).

Our study is helpful in directing violence prevention programs towards high-risk areas. Most reported incidents of violence happened in the clinics and emergency departments. For example, in a study conducted in Italy, staff who worked in emergency and mental health departments were more at risk of violence (24). Other findings of the study suggest that senior managers were unlikely to be informed of the magnitude of workplace violence towards nurses. Similarly, nurses were rarely informed of any plans developed by the managers to reduce workplace violence, or of the supports that were available to nurses when and if violence occurred. Further widespread studies of workplace violence toward nurses as well as other hospital staff are required. Also studies are required to assess the potential reasons for violence, and studies that look for effective interventions to prevent violence and address it when it occurs.

According to studies conducted in the field of workplace violence against nurses, some strategies can be used to reduce the incidence of workplace violence against nurses, such as:

- Teaching nurses strategies to cope with violent behavior;

- Continuous assessment of hazardous situations and providing an abuse-free working environment;

- Establishing a training program for nurses on how to interactive with aggressive patients and their relatives and teaching them anger management methods;

- Establishing clear procedures for reporting incidents of violence and encouraging personnel to report cases of violence.

Based on a study carried out in an emergency unit in Iran, use of anger management training is effective in increasing self-control skills of nurses faced with workplace violence (29).

One of the limitations of the study was that it was conducted in a major referral hospital in Tehran. As such, the rates and level of violence observed in this hospital may not be comparable to other hospitals in the country. Still, our findings were similar to those reported from a couple of smaller studies. Due to cultural sensitivities, we dropped the questions relevant to sexual violence. Future studies should consider innovative approaches to overcome such limitations.

Generally, this study demonstrated that workplace violence is an important nuisance to nurses’ services in a major hospital in Tehran. The high rate of reported workplace violence may demonstrate that the existing safeguards aiming to protect the staff from abusive patients and relatives are inadequate. Our study involved self-completion of the questionnaires. Therefore, recall bias in responding to the questions may have affected the findings. Such limitations also affected most of the studies previously conducted in different countries.

Acknowledgments

We thank all people who helped us carry out the study especially the hospital’s Chairman, vice-Chairman, matron and the nurses who participated in the study.

Ethical issues

Tehran University of Medical Sciences - Ethics Committee. Reference number: 130/2015.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ET: Conception and design, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting of the manuscript, Final approval of the manuscript; AR: Conception and design, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting of the manuscript, Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, Final approval of the manuscript; MA: Conception and design, Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, Final approval of the manuscript; AAK: Conception and design, Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, Final approval of the manuscript; SMH: Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting of the manuscript, Final approval of the manuscript.

Authors’ affiliations

1Department of Health Management and Economics, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. 2Department of Health Management and Economics, School of Public Health and Knowledge Utilization Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. 3Health Management and Economics Research Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Key messages

Notes

Citation: Teymourzadeh E, Rashidian A, Arab M, Akbari-Sari A, Hakimzadeh SM. Nurses exposure to workplace violence in a large teaching. Int J Health Policy Manag 2014; 3: 301–305. 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.98

References

Articles from International Journal of Health Policy and Management are provided here courtesy of Kerman University of Medical Sciences

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2014.98

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

http://www.ijhpm.com/article_2896_751d61d158dc2d41e59d1a74c1c52c2d.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.15171/ijhpm.2014.98

Article citations

Developing and validating the nurse-patient relationship scale (NPRS) in China.

BMC Nurs, 23(1):255, 22 Apr 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38649929 | PMCID: PMC11034141

Fear of violence and working department influences physical aggression level among nurses in northwest Ethiopia government health facilities.

Heliyon, 10(6):e27536, 08 Mar 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38509935 | PMCID: PMC10951522

Workplace violence against nurses: a narrative review.

J Clin Transl Res, 8(5):421-424, 13 Sep 2022

Cited by: 7 articles | PMID: 36212701 | PMCID: PMC9536186

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Prevalence of workplace violence against health care workers in hospital and pre-hospital settings: An umbrella review of meta-analyses.

Front Public Health, 10:895818, 08 Aug 2022

Cited by: 28 articles | PMID: 36003634 | PMCID: PMC9393420

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Prevalence of lateral violence in nurse workplace: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

BMJ Open, 12(3):e054014, 29 Mar 2022

Cited by: 7 articles | PMID: 35351708 | PMCID: PMC8966576

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (19) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Workplace violence among Iraqi hospital nurses.

J Nurs Scholarsh, 39(3):281-288, 01 Jan 2007

Cited by: 44 articles | PMID: 17760803

Violence towards the caregiver. A growing crisis for professional nursing.

Mich Nurse, 76(1):11-12, 01 Jan 2003

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 12613427

Workplace violence against nursing staff in a Saudi university hospital.

Int Nurs Rev, 63(2):226-232, 02 Feb 2016

Cited by: 34 articles | PMID: 26830364