Abstract

Aims

Media reports suggest increasing popularity of marijuana concentrates ("dabs"; "earwax"; "budder"; "shatter; "butane hash oil") that are typically vaporized and inhaled via a bong, vaporizer or electronic cigarette. However, data on the epidemiology of marijuana concentrate use remain limited. This study aims to explore Twitter data on marijuana concentrate use in the U.S. and identify differences across regions of the country with varying cannabis legalization policies.Methods

Tweets were collected between October 20 and December 20, 2014, using Twitter's streaming API. Twitter data filtering framework was available through the eDrugTrends platform. Raw and adjusted percentages of dabs-related tweets per state were calculated. A permutation test was used to examine differences in the adjusted percentages of dabs-related tweets among U.S. states with different cannabis legalization policies.Results

eDrugTrends collected a total of 125,255 tweets. Almost 22% (n=27,018) of these tweets contained identifiable state-level geolocation information. Dabs-related tweet volume for each state was adjusted using a general sample of tweets to account for different levels of overall tweeting activity for each state. Adjusted percentages of dabs-related tweets were highest in states that allowed recreational and/or medicinal cannabis use and lowest in states that have not passed medical cannabis use laws. The differences were statistically significant.Conclusions

Twitter data suggest greater popularity of dabs in the states that legalized recreational and/or medical use of cannabis. The study provides new information on the epidemiology of marijuana concentrate use and contributes to the emerging field of social media analysis for drug abuse research.Free full text

“Time for dabs”: Analyzing Twitter data on marijuana concentrates across the U.S.

Abstract

Aims

Media reports suggest increasing popularity of marijuana concentrates (“dabs”; “earwax”; “budder”; “shatter; “butane hash oil”) that are typically vaporized and inhaled via a bong, vaporizer or electronic cigarette. However, data on the epidemiology of marijuana concentrate use remain limited. This study aims to explore Twitter data on marijuana concentrate use in the U.S. and identify differences across regions of the country with varying cannabis legalization policies.

Methods

Tweets were collected between October 20 and December 20, 2014, using Twitter's streaming API. Twitter data filtering framework was available through the eDrugTrends platform. Raw and adjusted percentages of dabs-related tweets per state were calculated. A permutation test was used to examine differences in the adjusted percentages of dabs-related tweets among U.S. states with different cannabis legalization policies.

Results

eDrugTrends collected a total of 125,255 tweets. Almost 22% (n=27,018) of these tweets contained identifiable state-level geolocation information. Dabs-related tweet volume for each state was adjusted using a general sample of tweets to account for different levels of overall tweeting activity for each state. Adjusted percentages of dabs-related tweets were highest in states that allowed recreational and/or medicinal cannabis use and lowest in states that have not passed medical cannabis use laws. The differences were statistically significant.

Conclusions

Twitter data suggest greater popularity of dabs in the states that legalized recreational and/or medical use of cannabis. The study provides new information on the epidemiology of marijuana concentrate use and contributes to the emerging field of social media analysis for drug abuse research.

1. INTRODUCTION

In the context of the changing legislative landscape of cannabis use (National Conference of State Legislatures; NCSL, 2015), law enforcement and popular media reports suggest a growing trend across the country of manufacture and use of marijuana concentrates (Healy, 2015; Drug Enforcement Administration; DEA, 2014a; Carson, 2013;). Marijuana concentrates are highly potent tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) preparations derived from marijuana plant material. Although marijuana concentrates, or hash oil, have been available for centuries, recent increases in the U.S. are associated with advanced methods to obtain high-level THC extractions (DEA, 2014a,b). Although many methods can be used to convert flower cannabis into concentrates, the solvent-based method that uses butane to extract THC is one of the more commonly used (DEA, 2014a,b). Once converted to concentrates, such products are commonly referred to as “dabs,” “hash oil,” “shatter,” “budder,” or “earwax.” In Colorado and Washington, marijuana concentrates can be obtained legally from licensed retailers and producers. Qualified patients can also obtain marijuana concentrates at some medical marijuana dispensaries. However, in many parts of the country, there has been an increase in explosions and injuries resulting from home-based operations to produce marijuana concentrates using butane gas (DEA 2014a).

Marijuana concentrates produced using solvent-based methods typically contain very high THC levels that can exceed 80% (DEA, 2014b). Most commonly, they are vaporized and inhaled via a bong, oil pipe, vaporizer or electronic cigarette (Loflin and Earleywine, 2014; DEA, 2014b). Because of the increased THC concentration and novel means of administration, use of “dabs” might lead to more severe psychological and physical problems, (Moore et al., 2007; Hall and Degenhardt, 2009; Degenhardt et al., 2013). Prior research has suggested that use of high potency cannabis may increase the risk of cannabis dependence (Hall and Degenhardt, 2015), first-episode psychosis (Di Forti et al., 2014, 2015), and contribute to the cognitive skills impairment (Ramaekers et al., 2006).

Although mainstream media reports about marijuana concentrate use in the U.S. have been increasing (Kim, 2013; Denson, 2014; Wyatt and Johnson, 2015; Healy, 2015; Associated Press, 2015), research on its use remains very limited. A recent web-based study that recruited 357 participants via craigslist found that users viewed dabs to be more dangerous than flower cannabis and reported an increase in tolerance and withdrawal symptoms as a result of using dabs (Loflin and Earleywine, 2014). Overall, there is a lack of epidemiological data on regional differences in marijuana concentrate use because current surveillance systems do not systematically track use of marijuana concentrates apart from general cannabis consumption (SAMHSA, 2014).

There is a growing recognition that Twitter data can be highly useful for public health surveillance (Bartlett and Wurtz, 2013; Burke-Garcia and Scally, 2014; Jashinsky et al., 2014). Emerging research also suggests its utility in tracking drug abuse trends, including Twitter-based studies that focused on problem drinking (Joshua et al., 2012), and nonmedical use of Adderall among college students (Hanson et al., 2013). Prior research has also used a commercial social media analytics company to examine cannabis-related tweets, and found that the majority of tweets expressed pro-marijuana sentiment, and involved a greater proportion of African Americans and young individuals compared with the Twitter average (Cavazos-Rehg et al., 2014, 2015).

Currently, Twitter reports 302 million monthly active users that generate over 500 million tweets per day (Twitter, 2015). Twitter use is more common among young adults (Kim et al., 2013), an age group that also displays the highest rates of cannabis and other substance use (SAMHSA, 2014). Although tweets are limited to 140 characters and thus contain very brief information, because of the volume of data generated by Twitter users, analysis of tweets can provide valuable population-level metrics. The study aims to explore tweets related to marijuana concentrates (“dabs”) and identify differences across regions with varying cannabis legalization policies.

2. METHODS

Tweets were collected using Twitter's streaming API that provides free access to 1% of all tweets (Twitter, 2014). However, with a limited number of keywords, all or most relevant tweets can be collected since such content will be far less than 1% of overall tweet volume (Morstatter et al., 2013). A Twitter data filtering and aggregation framework was available through the eDrugTrends system (eDrugTrends, 2015), which adapts the social media analysis capabilities of the Twitris platform (Sheth et al., 2013). Data were collected between October 20 and December 20, 2014. Data collection was limited to English language content. The Wright State University IRB reviewed the protocol and determined that it met the criteria for Human Subjects Research exemption 4 because it is limited to publicly available tweets. To protect the anonymity of tweeters, no individual screen names of Twitter users are included in any reports or publications. Global Positioning System (GPS) coordinates were converted into state-level geo-information and analyzed in the aggregate form.

The following keywords were used to collect tweets: “dabs”; “hash oil”; “butane honey oil”; “smoke/smoking shatter”; “smoke/smoking budder”; “smoke/smoking concentrates.” Selected keywords were pre-tested to assure that they collected relevant information. Several keywords were modified (e.g., adding “smoke/smoking” to “shatter,” “concentrates,” and “budder”) and/or removed (e.g., “BHO”) after determining that they generated irrelevant data. Keywords “earwax marijuana” and “marijuana BHO” generated no tweets.

Geolocation information of tweets was processed by the eDrugTrends/Twitris platform (Sheth et al., 2013). Twitter users may indicate geolocation information in their user profiles, or enable their tweets to contain GPS coordinates via a mobile phone that supports the feature. Tweets that contained geolocation information indicating a state in the U.S. were extracted for further analysis.

To adjust for the different level of tweeting activity in each state, we generated a general sample of tweets. This general sample was collected over an 8-day period and consisted of the default random sample of 1% of all tweets provided by the Twitter Application Programming Interface (API). The general sample was processed using eDrugTrends to extract tweets that contained identifiable state-level geolocation information (N=209,837) (Table 1).

Table 1

Ranking of States by Percentage of Tweets in General and Dabs-Related Samples.

| Rank Order | General Sample of Tweets (N=209,837) | Dabs-Related Sample of Tweets (N=27,018) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of General Sample of Tweets per State | Raw Percentage of Dabs-Related Tweets per State | Adjusted Percentage of Dabs-Related Tweets per State | ||||

| 1 | CA | 13.6 | CA | 20.6 | OR | 6.4 |

| 2 | NY | 10.2 | TX | 8.4 | CO | 6.2 |

| 3 | TX | 10.0 | FL | 6.3 | WA | 4.0 |

| 4 | FL | 6.6 | NY | 6.0 | MI | 3.5 |

| 5 | IL | 4.2 | MI | 5.2 | AK | 3.4 |

| 6 | GA | 3.9 | CO | 5.0 | NM | 3.2 |

| 7 | PA | 3.5 | WA | 4.1 | ME | 3.1 |

| 8 | OH | 3.1 | OR | 3.4 | NV | 2.9 |

| 9 | MI | 2.8 | IL | 3.1 | CA | 2.9 |

| 10 | NC | 2.7 | PA | 2.8 | SD | 2.8 |

| 11 | NJ | 2.3 | OH | 2.8 | AZ | 2.7 |

| 12 | MA | 2.3 | AZ | 2.6 | MN | 2.6 |

| 13 | MO | 2.0 | NV | 2.3 | HI | 2.5 |

| 14 | VA | 2.0 | MA | 2.1 | KS | 2.4 |

| 15 | TN | 2.0 | NJ | 1.8 | NE | 2.3 |

| 16 | LA | 1.9 | MN | 1.7 | IA | 2.3 |

| 17 | WA | 1.9 | GA | 1.6 | RI | 2.1 |

| 18 | AZ | 1.8 | LA | 1.5 | MT | 2.1 |

| 19 | MD | 1.8 | MD | 1.5 | VT | 2.0 |

| 20 | DC | 1.5 | MO | 1.3 | WI | 2.0 |

| 21 | CO | 1.5 | NC | 1.2 | NH | 2.0 |

| 22 | KY | 1.5 | WI | 1.2 | FL | 1.8 |

| 23 | NV | 1.5 | VA | 1.2 | ND | 1.8 |

| 24 | AL | 1.4 | IN | 0.9 | UT | 1.7 |

| 25 | IN | 1.3 | KS | 0.9 | OH | 1.7 |

| 26 | MN | 1.2 | KY | 0.8 | MA | 1.7 |

| 27 | WI | 1.1 | DC | 0.8 | TX | 1.6 |

| 28 | OR | 1.0 | TN | 0.8 | MD | 1.5 |

| 29 | SC | 1.0 | SC | 0.7 | PA | 1.5 |

| 30 | CT | 0.8 | IA | 0.7 | CT | 1.4 |

| 31 | OK | 0.8 | CT | 0.6 | NJ | 1.4 |

| 32 | KS | 0.7 | NE | 0.6 | LA | 1.4 |

| 33 | WV | 0.6 | NM | 0.6 | IL | 1.4 |

| 34 | AR | 0.5 | UT | 0.5 | SC | 1.4 |

| 35 | UT | 0.5 | ME | 0.5 | IN | 1.3 |

| 36 | IA | 0.5 | OK | 0.5 | WV | 1.3 |

| 37 | NE | 0.5 | AK | 0.4 | MO | 1.2 |

| 38 | RI | 0.4 | RI | 0.4 | ID | 1.1 |

| 39 | MS | 0.3 | AL | 0.4 | VA | 1.1 |

| 40 | NM | 0.3 | WV | 0.4 | OK | 1.1 |

| 41 | ME | 0.3 | HI | 0.4 | NY | 1.1 |

| 42 | HI | 0.3 | AR | 0.2 | KY | 1.1 |

| 43 | WY | 0.3 | NH | 0.2 | DC | 1.0 |

| 44 | AK | 0.2 | MT | 0.2 | WY | 0.9 |

| 45 | ID | 0.2 | SD | 0.2 | NC | 0.8 |

| 46 | DE | 0.2 | ID | 0.1 | AR | 0.8 |

| 47 | NH | 0.2 | VT | 0.1 | GA | 0.8 |

| 48 | MT | 0.2 | WY | 0.1 | TN | 0.7 |

| 49 | VT | 0.1 | ND | 0.1 | DE | 0.7 |

| 50 | ND | 0.1 | MS | 0.1 | AL | 0.6 |

| 51 | SD | 0.1 | DE | 0.1 | MS | 0.5 |

First, raw state-level percentages of dabs-related tweets were computed. Next, adjusted percentages were calculated using general sample rates to account for different levels of tweeting activity in each state. In particular, for each state, we computed the ratio of the proportion of dabs tweets within a particular state to the proportion of general sample of tweets. These ratios were then rescaled by dividing each by the sum of ratios across states and multiplying by 100, resulting in adjusted state-specific percentages of dabs tweets.

A permutation test with 10,000 replications was performed using R (R Core Team, 2014) to examine differences in the adjusted percentages of dabs-related tweets among U.S. states with different cannabis legalization policies. We tested the null hypothesis of no difference between adjusted percentages across legal status, with pairwise comparisons between legal statuses adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Holm-Bonferroni procedure (Holm, 1979).

States’ legal statuses were classified as follows: 1) “Status 1” includes 2 states that passed laws legalizing medical and recreational use of cannabis prior to January 2015 (CO, WA); 2) “Status 2” includes 21 states and the District of Columbia that have legalized medical but not recreational use of cannabis (AK, AZ, CA, CT, DC, DE, HI, IL, MD, ME, MA, MI, MN, MT, NY, NV, NH, NJ, NM, OR, RI, VT); 3) “Status 3” includes 27 states that had not yet passed medical cannabis laws (AL, AR, FL, GA, ID, IN, IA, KS, KY, LA, MS, MO, NE, NC, ND, OH, OK, PA, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VA, WV, WI, WY). Although Alaska, Oregon, and the District of Columbia voted in November 2014 for legalization of recreational cannabis, these laws were not scheduled to become effective until 2015. Thus, they were classified as Status 2.

3. RESULTS

Over a two-month period, eDrugTrends collected a total sample of 125,255 tweets. Keyword “dabs” produced 121,061 tweets, which comprised over 99% of the total sample (e.g., “Dabs on Dabs on Dabs;” “I just need a cute girl to take dabs with me and get stoned together”). “Hash oil” generated 3,671 tweets (“I smoked some hash oil. Im buzzin like crazy”). Other keywords were much less commonly used on Twitter: “Smoke/smoking shatter” produced 488 tweets (“Had some vivid ass dreams last night after smoking almost a full gram of shatter”); “Smoke/smoking budder” produced 50 tweets (“I swear after smoking budder for so long, smoking weed is a foreign concept”); “Smoke/smoking concentrates” (“People that smoke concentrates are whack, flower power”) identified 84 tweets; and “butane honey oil” generated 35 tweets (“I like the butane honey oil lol”).

Out of a total sample of 125,255 tweets, 22% (n=27,018) contained state-level geolocation information. These 27,018 tweets were posted by 15,897 unique users. Raw counts of dabs-related tweets were the highest in California, Texas, Florida, and New York (Table 1), which are also the most populous states. However, after adjusting for the different levels of Twitter use for each state based on the general sample of tweets, Oregon, Colorado, and Washington had the highest proportions of dabs-related tweets, while Mississippi and Alabama had the lowest (Table 1).

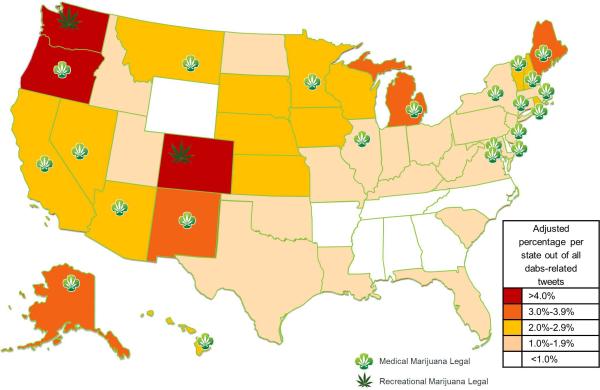

We found statistically significant differences in the average adjusted proportion of dabs tweets between states with different legal status. The average adjusted proportion of dabs-related tweets for Status 1 states was 5.1%, for Status 2 states 2.3%, and for Status 3 states 1.4%. After adjusting for multiple comparisons, all three pairwise differences were significantly different from 0 (p<0.05). As seen from the map that displays regional differences in the adjusted percentages of dabs-related tweets (Figure 1), rates appear to be greater in the Western part than in the Eastern part of the U.S.

4. DISCUSSION

The analysis of Twitter data demonstrates that the average adjusted percentages of dabs-related tweets were significantly greater in states with recreational and/or medical marijuana laws. Oregon, Colorado, and Washington had the highest rates, compared to other states. Although epidemiological data on marijuana concentrate use are lacking, our Twitter-based findings are consistent with the DEA report suggesting that marijuana concentrate production labs are more common on the West Coast and in the states with more relaxed marijuana laws (DEA, 2014a).

Colorado and Washington were the first states to legalize recreational cannabis use and have established booming commercial markets of cannabis products, including marijuana concentrates (Marijuana Policy Group, 2014; Kleiman, 2015). Interestingly, a web-based survey of cannabis users (N=1,659) that was conducted in Washington state in the year prior to legalization of recreational marijuana use, found that “dabbing” was quite common, with about 47% of surveyed cannabis users reporting past year use of dabs (Beau et al., 2013). Colorado law allows home-based production of concentrates, but due to increased injuries and explosions, is now considering a ban on home-based operations that use butane and other hazardous materials to manufacture marijuana concentrates (Colorado General Assembly, 2015).

Although Oregon has just passed laws allowing recreational cannabis use that are to become operational in 2015, it has one of the oldest medical marijuana programs in the U.S., and a growing medical marijuana dispensary system (Oregon Health Authority, 2015). Oregon also has one of the highest rates of marijuana use in the country, with over 19% of individuals reporting past year marijuana use, compared to average U.S. rate of 12.3% (SAMHSA, 2014). Overall, greater popularity of dabbing in Oregon, and other states that allow medical marijuana use, could be partially related to the emergence of vaporizer use being perceived as a safer and more therapeutically beneficial alternative to smoking among medical marijuana patients (Abrams et al., 2007; Earleywine and Barnwell, 2007). Furthermore, prior research suggested that the emerging trend of “dabbing” is linked to recent increases in the availability of marijuana concentrates at medical marijuana dispensaries (Loflin and Earleywine, 2014).

Regional differences in dabs-related tweets could be partially related to greater acceptance of cannabis use in states that allow medical and/or recreational use. In addition, production of marijuana concentrates requires access to large amounts of plant material. Although the ratio may vary from producer to producer, an ounce of plant material can generally yield only a few grams of dabs (Colorado Pot Guide, 2015). Easier access to the quantities of raw material needed to produce marijuana concentrates might be one of the reasons for potentially greater popularity of dabs in the states that allow medical and/or recreational cannabis use compared to states where marijuana use is illegal.

Our results also show greater dabs-related tweeting activity in the Western part of the country (Figure 1). Potentially, these differences might be at least partially related to the fact that medical marijuana laws in the western states were passed in the late 90s-early 2000s, while in most of the medical marijuana states on the East Coast, such laws came into effect in 2010-2014 (NCSL, 2015).

Interpretation of the study findings should take into account several limitations. First, our results are limited to English language content. Second, lack of demographic information presents another limitation, which is inherent to most social media studies. Third, the findings from the study should be interpreted with caution given known and not yet fully understood characteristics and behaviors of Twitter users. For example, it is known that Twitter users are more likely to be young adults, and thus our findings may be more reflective of drug use behaviors among younger than older age groups. Also, it is not known if there are clear differences between those who choose to identify their geolocation and those who do not, which might contribute to additional limitations when comparing regional differences. In addition, we do not know the characteristics of people who tweeted in terms of medical versus recreational use. It is also likely that regional differences in dabs-related tweets might be partially related to the fact that users living in states with more liberal cannabis policies might feel less restricted to publically acknowledge their use than individuals in states where cannabis use is illegal. Finally, selection of keywords and information extraction techniques might have contributed to additional limitations. Some relevant keywords (wax, BHO) had to be excluded because they generated high numbers of irrelevant tweets. Improvement of information extraction techniques and disambiguation will help address such limitations in the future research.

The study contributes new information on the emerging trend of “dabbing,” a form of marijuana concentrate, which may carry significant health consequences and risks. In the context of shifting cannabis legalization policies, active monitoring is needed to identify emerging issues and trends, and to inform timely prevention and policy measures. Our present study demonstrates that Twitter can be of particular value in detection of emerging drug use practices that are difficult to capture using traditional epidemiological surveillance methods. Twitter data collection and processing can be much more rapid, compared to traditional survey methods. Further development of information extraction methods will help conduct more powerful, in-depth analyses of Twitter data for drug abuse epidemiology research. Additional studies using community-recruited samples and web-based surveys are also needed to corroborate Twitter findings and to better understand this emerging trend. Considering the potential adverse effects inherent in these concentrated forms of cannabis use (Hall and Degenhardt, 2015; Kleiman, 2015), gaining new insights on this emerging trend would help to better inform users, practitioners and policy makers.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of the paper is presented at the 77th Annual Meeting of College on Problems of Drug Dependence - June, 13-18, 2015, Phoenix, Arizona.

Role of Funding Source. This study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), Grant No. R01 DA039454-01 (Daniulaityte, PI; Sheth, PI). The funding source had no further role in the study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors. R. Daniulaityte, A. Sheth, R. Carlson, R. Nahhas, S. Martins and E. Boyer designed the study. S. Wijeratne and G.A. Smith worked on the development of eDrugTrends platform for collection and filtering of Twitter data. F. Lamy contributed to data extraction and management. R. Nahhas helped with statistical analysis. R. Daniulaityte reviewed the literature and wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors reviewed, commented, and edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest. All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Abrams DI, Vizoso HP, Shade SB, Jay C, Kelly ME, Benowitz NL. Vaporization as a smokeless cannabis delivery system: a pilot study. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007;82:572–578. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Associated Press (AP) ‘Industrial-Scale’ Hash Oil Lab Busted in San Diego County. Associated Press DBA Press Association; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett C, Wurtz R. Twitter and public health. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. Dec 18. 2013 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Beau K, Caulkins JP, Midgette G, Dahlkemper L, MacCoun RJ, Pacula RL. Before the Grand Opening: Measuring Washington State's Marijuana Market in the Last Year before Legalized Commercial Sales. RAND Corporation; Santa Monica, CA: 2013. 2013. http://www.Rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR466. RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Burke-Garcia A, Scally G. Trending now: future directions in digital media for the public health sector. J. Public Health. 2014;36:527–534. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Colorado General Assembly (CGA) [05/18/2015];House Bill 15-1305: Concerning a Prohibition on Manufacturing Marijuana Concentrate in an Unregulated Environment using an Inherently Hazardous Substance, and, in Connection Therewith, Making an Appropriation. 2015 http://www.colorado.gov/

- Carson T. Marijuana Wax. DrugScopes: Cincinnati Drug and Poison Information Center; 2013. [05/18/2015]. Fall, 2013. http://www.cincinnatichildrens.org/service/d/dpic/community/Newsletters/ [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos-Rehg P, Krauss M, Grucza R, Bierut L. Characterizing the followers and tweets of a marijuana-focused Twitter handle. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014;16:e157. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos-Rehg PA, Krauss M, Fisher SL, Salyer P, Grucza RA, Bierut LJ. Twitter chatter about marijuana. J. Adolesc. Health. 2015;56:139–145. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Colorado Pot Guide (CPG) [05/18/2015];2015 https://www.coloradopotguide.com/

- Degenhardt L, Coffey C, Romaniuk H, Swift W, Carlin JB, Hall WD, Patton GC. The persistence of the association between adolescent cannabis use and common mental disorders into young adulthood. Addiction. 2013;108:124–133. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Denson B. Hash Oil Explosions in Portland Area Lead to Federal Charges for Three. The Oregonian; Portland, OR: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Di Forti M, Sallis H, Allegri F, Trotta A, Ferraro L, Stilo SA, Marconi A, La Cascia C, Reis Marques T, Pariante C, Dazzan P, Mondelli V, Paparelli A, Kolliakou A, Prata D, Gaughran F, David AS, Morgan C, Stahl D, Khondoker M, MacCabe JH, Murray RM. Daily use, especially of high-potency cannabis, drives the earlier onset of psychosis in cannabis users. Schizophr. Bull. 2014;40:1509–1517. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) Marijuana Concentrates. U.S. Department of Justice, DEA; 2014a. [Google Scholar]

- Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) 2014 National Drug Threat Assessment Summary. U.S. Department of Justice, DEA; 2014b. [Google Scholar]

- Earleywine M, Barnwell SS. Decreased respiratory symptoms in cannabis users who vaporize. Harm Reduct. J. 2007;4:11. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- eDrugTrends Project Information. 2015 http://wiki.knoesis.org/index.php/EDrugTrends.

- Hall W, Degenhardt L. Adverse health effects of non-medical cannabis use. Lancet. 2009;374:1383–1391. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Hall W, Degenhardt L. High potency cannabis. BMJ. 2015;350:h1205. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson CL, Burton SH, Giraud-Carrier C, West JH, Barnes MD, Hansen B. Tweaking and tweeting: exploring Twitter for nonmedical use of a psychostimulant drug (Adderall) among college students. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013;15:e62. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Healy J. Odd Byproduct Of Legal Weed: Homes Blow Up. (Cover story) Vol. 164. New York Times; 2015. pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Jashinsky J, Burton SH, Hanson CL, West J, Giraud-Carrier C, Barnes MD, Argyle T. Tracking suicide risk factors through Twitter in the US. Crisis. 2014;35:51–59. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Joshua HW, Parley CH, Carl LH, Prier K, Giraud-Carrier Christophe, Shannon Neeley E, Michael DB. Temporal variability of problem drinking on Twitter. Open J. Prev. Med. 2012;2:43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kim V. [05/19/2015];Is ‘dabbing’ the crack of pot? The Fix. 2013 Available from: http://www.thefix.com/content/dabbing-crack-pot-legalization91774.

- Kim AE, Hansen HM, Murphy J, Richards AK, Duke J, Allen JA. Methodological considerations in analyzing Twitter data. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2013;2013:140–146. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiman MA. Legal Commercial Cannabis Sales in Colorado and Washington: What Can We Learn. Brookings Institution; Washington, DC: 2015. www.globalinitiative.net. [Google Scholar]

- Loflin M, Earleywine M. A new method of cannabis ingestion: the dangers of dabs? Addict. Behav. 2014;39:1430–1433. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Marijuana Policy Group (MPG) Market Size and Demand for Marijuana in Colorado: Prepared for the Colorado Department of Revenue. State Government of Colorado; Denver, CO.: 2014. [05/19/2015]. www.colorado.gov/pacific/sites/default/files/Market%20Size%20and%20Demand%20Study,%20July%209,%202014%5B1%5D.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Moore TH, Zammit S, Lingford-Hughes A, Barnes TR, Jones PB, Burke M, Lewis G. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. 2007;370:319–328. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Morstatter F, Pfeffer J, Liu H, Carley KM. Is the sample good enough? Comparing data from Twitter's streaming API with Twitter's firehose. arXiv preprint arXiv. 2013:1306, 5204. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) State Medical Marijuana Laws. 2015 http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-medical-marijuana-laws.aspx.

- Oregon Health Authority (OHA) [05/18/2015];Medical Marijuana Dispensary Program. 2015 http://www.oregon.gov/oha/mmj/Pages/index.aspx.

- R Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) 2012-2013 National Survey on Drug use and Health: Model-Based Prevalence Estimates (50 States and the District of Columbia) Office of Applied Studies; Rockville, MD.: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sheth A, Jadhav A, Kapanipathi P, Lu C, Purohit H, Smith GA, Wang W. Twitris - a system for collective social intelligence. In: Alhajj R, Rokne J, editors. Encyclopedia of Social Network Analysis and Mining (ESNAM) Springer; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Twitter About Company. 2015 https://about.twitter.com/company.

- Twitter Public Streams. 2014 https://dev.twitter.com/streaming/overview.

- Wyatt K, Johnson G. Hash Oil Explosions Prompt Proposed Changes in Pot States. Associated Press DBA Press Association; 2015. [Google Scholar]

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.07.1199

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc4581982?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

Evaluation of the Daily Sessions, Frequency, Age of Onset, and Quantity of Cannabis Use Questionnaire and its Relations to Cannabis-Related Problems.

Cannabis, 6(3):64-86, 03 Nov 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38035173 | PMCID: PMC10683753

Health, safety, and socioeconomic impacts of cannabis liberalization laws: An evidence and gap map.

Campbell Syst Rev, 19(4):e1362, 30 Oct 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 37915420 | PMCID: PMC10616541

Twitter activity surrounding the Finnish green party's cannabis legalisation proposal: A mixed-methods analysis.

Nordisk Alkohol Nark, 40(6):625-645, 30 May 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38045011 | PMCID: PMC10688398

Associations of alternative cannabis product use and poly-use with subsequent illicit drug use initiation during adolescence.

Psychopharmacology (Berl), 03 Mar 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 36864260 | PMCID: PMC10475141

Linguistic Methodologies to Surveil the Leading Causes of Mortality: Scoping Review of Twitter for Public Health Data.

J Med Internet Res, 25:e39484, 12 Jun 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 37307062 | PMCID: PMC10337472

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (57) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

"You got to love rosin: Solventless dabs, pure, clean, natural medicine." Exploring Twitter data on emerging trends in Rosin Tech marijuana concentrates.

Drug Alcohol Depend, 183:248-252, 27 Dec 2017

Cited by: 16 articles | PMID: 29306816 | PMCID: PMC5803369

"Retweet to Pass the Blunt": Analyzing Geographic and Content Features of Cannabis-Related Tweeting Across the United States.

J Stud Alcohol Drugs, 78(6):910-915, 01 Nov 2017

Cited by: 14 articles | PMID: 29087826 | PMCID: PMC5668996

"Those edibles hit hard": Exploration of Twitter data on cannabis edibles in the U.S.

Drug Alcohol Depend, 164:64-70, 26 Apr 2016

Cited by: 47 articles | PMID: 27185160 | PMCID: PMC4893972

Cannabis use, attitudes, and legal status in the U.S.: A review.

Prev Med, 104:13-23, 11 Jul 2017

Cited by: 236 articles | PMID: 28705601 | PMCID: PMC6348863

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NIDA NIH HHS (3)

Grant ID: R01 DA039454

Grant ID: K24 DA037109

Grant ID: R01 DA039454-01

NIMH NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: R01 MH105384