Abstract

Free full text

Toll-like Receptor 10 in Helicobacter pylori Infection

Abstract

Innate immunity plays important roles in the primary defense against pathogens, and epidemiological studies have suggested a role for Toll-like receptor 1 (TLR1) in Helicobacter pylori susceptibility. Microarray analysis of gastric biopsy specimens from H. pylori–positive and uninfected subjects showed that TLR10 messenger RNA (mRNA) levels were upregulated approximately 15-fold in infected subjects; these findings were confirmed by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis. Immunohistochemical investigation showed increased TLR10 expression in the gastric epithelial cells of infected individuals. When H. pylori was cocultured with NCI-N87 gastric cells, both TLR10 and TLR2 mRNA levels were upregulated. We compared the ability of TLR combinations to mediate nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activation. Compared with other TLR2 subfamily heterodimers, the TLR2/TLR10 heterodimer mediated the greatest NF-κB activation following exposure to heat-killed H. pylori or H. pylori lipopolysaccharide. We conclude that TLR10 is a functional receptor involved in the innate immune response to H. pylori infection and that the TLR2/TLR10 heterodimer functions in H. pylori lipopolysaccharide recognition.

Helicobacter pylori is a spiral, gram-negative, human pathogen present in the stomachs of approximately half of the world's population and is responsible for most cases of peptic ulcer disease and gastric cancer [1–3]. The infection is typically transmitted within families during childhood, and it generally persists for decades. The severity of H. pylori–related disease varies greatly among infected individuals, with the outcome governed by interactions between host, bacterial, and environmental factors [4, 5].

The innate immune system provides one of the first defensive barriers against bacterial infection [6]. H. pylori expresses several pathogen-associated molecular pattern antigens, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and flagellin. However, the role of the innate immune response to H. pylori remains unclear in part because H. pylori is able to avoid detection by several types of pattern-recognition receptors that are crucial for the recognition of other gram-negative enteropathogens [7–10]. In addition, H. pylori LPS does not stimulate a vigorous Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) responses, unlike most other gram-negative bacteria [10, 11]. The response of TLR5 to H. pylori flagellin is also weak, owing to modifications in the N-terminal TLR5 recognition domain [12]. However, several studies have suggested that TLR2 is able to sense H. pylori LPS [13, 14].

Although H. pylori has evolved elaborate strategies to evade and subvert host immune defenses, interpretation of the published studies related to the TLR response to H. pylori is complicated by the fact that most studies rely on models in which the respective TLR is ectopically expressed. Recently, a genome-wide association study (GWAS) meta-analysis found that the TLR1-TLR6-TLR10 locus was associated with H. pylori seroprevalence and focused on the potential importance of TLR1 [15]. These results were consistent with work showing that TLRs play an important role in susceptibility to other infections [16, 17]. Here, we provide evidence that TLR10 rather than TLR1 plays a central role in innate immune responses following H. pylori infection.

METHODS

Gastric Mucosa Samples From Patients

We used gastric biopsy samples obtained from patients in 2 markedly different regions, Bhutan, Asia, and the Dominican Republic. As previously described [18], written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the protocols were approved by the ethics committees of Oita University (Japan), Chulalongkorn University (Thailand), and Universidad Autonoma de Santo Domingo (Dominican Republic), as well by the local hospitals where we collected samples. During endoscopy, 4 gastric biopsy specimens were obtained from the antrum: one each for H. pylori culture, rapid urease test, histological examination, and cytokine examination. The clinical diagnoses after endoscopy included gastritis, duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, and gastric cancer. Peptic ulcers and gastric cancer were identified by endoscopy; gastric cancers were confirmed by histopathologic analysis. Gastritis was defined as H. pylori gastritis in the absence of peptic ulcers or gastric malignancy. Patients with a history of partial gastric resection were excluded. Patients who had received H. pylori eradication therapy or treatment with antibiotics, bismuth-containing compounds, H2-receptor blockers, or proton pump inhibitors within 4 weeks prior to the study were also excluded.

All biopsy specimens obtained for culture and for RNA analyses were placed in a −20°C freezer and subsequently sent frozen on dry ice by express mail to Oita University Faculty of Medicine, Japan, where they were stored at −80°C until use. Biopsy specimens for histologic analysis were fixed in buffered formalin at room temperature and were sent to Oita University Faculty of Medicine for sectioning and analyses.

H. pylori Status and cagA Status

H. pylori status was determined using the combination of rapid urease test, culture, serologic analysis, and histologic analysis as previously described [19, 20]. Patients were considered negative for H. pylori when results of all tests were negative. H. pylori–positive status required at least 1 positive test result. Antral biopsy specimens were obtained for the isolation of H. pylori, using standard culture methods [21]. DNA was extracted from cultured H. pylori, using a DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, California). The cagA status was determined by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for the conserved region of cagA and the cag empty site, as described previously [22, 23].

Gene Expression Microarrays

Messenger RNA (mRNA) from the gastric mucosa was isolated using commercially available kits (Ambion, Carlsbad, California). Gene expression levels from the gastric mucosa were analyzed with gene expression microarray. Complementary RNA was amplified, labeled, and hybridized to a 44 K Agilent 60-mer oligonucleotide microarray according to the manufacturer's instructions. All hybridized microarray slides were scanned using an Agilent scanner, and relative hybridization intensities and background hybridization values were calculated using Agilent Feature Extraction software (9.5.1.1). The microarray data were registered in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under accession number 60 427.

Histologic and Immunohistochemical Analyses

The fixed specimens were embedded in paraffin wax and stained with hematoxylin-eosin and Giemsa stains. The following features were evaluated on each slide by a histologist (T. U.) blinded to the patient's clinical diagnosis or the characteristics of the H. pylori strains: H. pylori density and the degree of mononuclear cell and polymorphonuclear leukocyte infiltration according to the updated Sydney system [24].

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed as described previously [25]. Briefly, after antigen retrieval and inactivation of endogenous peroxidase activity, tissue sections were incubated with anti-TLR10 (H-165; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, Texas) or rabbit polyclonal anti-H. pylori (DAKO, Copenhagen, Denmark) antibodies with diluting solution (DAKO) overnight at 4°C.

Cell Culture

Human NCI-N87 gastric cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Virginia). NCI-N87 gastric epithelial cell lines are a naturally polarized cell line that form a tight monolayer and exhibits gastric epithelial characteristics like ZO-1 and E-cadherin expression [26, 27]. Cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2. HEK-Blue cells (InvivoGen, San Diego, California), which are collections of HEK 293 engineered cell lines designed to a provide reliable method for screening and validating TLR agonists or antagonists, were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 mg/mL Normocin, and 100 mg/mL Zeocin (InvivoGen, San Diego, California) at 37°C in 5% CO2. Total RNA from human cell lines was extracted using commercially available kits (Ambion).

Reverse Transcription (RT)–PCR and Real-Time Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

RT-PCR was performed using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California). Real-time qPCR was performed using TaqMan PCR. TLR10 and β-actin mRNA levels in gastric mucosa were quantified using an ABI Prism 7300 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California). Specific primers and TaqMan probes (TLR10 and β-actin) were designed using a Gene Expression Assay kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, California). The samples were placed in the analyzer, and real-time qPCR was conducted according to the manufacturer's instructions. The expression of TLR10 mRNA was expressed as the ratio of TLR10 mRNA to β-actin mRNA. The ratio change in target gene relative to the β-actin control gene was determined by the 2−ΔΔCT1 method.

In in vitro experiments, we also measured the mRNA levels of TLR1, TLR2, TLR6, and TLR10 in NCI-N87 cells and the mRNA levels of interleukin 8 (IL-8) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) in HEK cells, using TaqMan probes (Applied Biosystems). These analyses were performed according to the procedures described above.

H. pylori Culture and H. pylori Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) Used for In Vitro Studies

H. pylori 26 695, TN2GF4, and cag pathogenicity island (PAI) isogenic mutants of strain 26 695 (26 695Δcag PAI) were used from our stocks. H. pylori was grown on Brucella blood agar (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, Maryland) containing 7% defibrinated horse blood for 72 hours. Before infection, bacteria were inoculated into brain heart infusion broth (Becton Dickinson) with 10% FBS and grown under microaerophilic conditions at 37°C overnight with shaking. Bacteria were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4), resuspended in PBS for the duration of infection, and used to infect cell cultures. Bacterial density was determined from the OD600. Cells were infected with H. pylori at multiplicities of infection (MOIs) ranging from 10 to 500. Heat-killed bacteria were prepared by growing H. pylori in liquid culture and placing the culture tubes in a boiling water bath for 30 minutes [27]. We purchased H. pylori LPS extracted from H. pylori strain CA2 (Wako Junyaku, Tokyo, Japan).

Transfections and Reporter Assays

HEK-Blue cells do not produce/express most TLRs (eg, TLR2), and they express low levels of endogenous TLR1, TLR6, and TLR10. Thus, they are widely used for TLR ligand analyses [28, 29]. We defined untreated HEK-Blue cells as HEK-Null cells in this study. HEK-Null cells were transfected with single or double plasmid from pUNO1-hTLR02, pUNO3-hTLR1, pUNO3-hTLR6, and pUNO3-hTLR10 (InvivoGen, San Diego, California), using LyoVec (InvivoGen) as a transfection reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were maintained in the selective medium and seeded at 1.0 × 104 cells/well on a 96-well plate the day before transfection. These cells were then stimulated by heat-killed H. pylori, H. pylori LPS, or Pam3CSK4 at 24 hours after transfection.

The reporter assay measured changes in nuclear factor–κB (NF-κB) activity, and secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase reporter HEK-Blue cells were used according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical Analysis

Clinical samples were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test for nonparametric data. In vitro samples were analyzed using the Student t test. Correlation coefficients were calculated with the Pearson product moment correlation coefficient test. The correlation coefficients of TLR10 and TLR2 expression were calculated with the Spearman rank correlation coefficient. A P value of <.05 was accepted as statistically significant. All analyses were performed using JMP 10.0. (SAS, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Subjects

Samples were obtained from 293 subjects (138 subjects from Bhutan and 155 subjects from the Dominican Republic). The prevalence of H. pylori was 64% in the Bhutan samples and 59% in the Dominican Republic samples. The prevalence of cagA positivity was 100% among Bhutanese subjects and 72% among Dominican subjects.

H. pylori–Induced Gene Expression Profiles

We selected 32 samples (16 samples from Bhutan and 16 samples from the Dominican Republic) for microarray analysis, based on typical pathological findings (4 samples each from 4 pathological groups: H. pylori–negative normal mucosa, mild gastritis, severe gastritis, and intestinal metaplasia; the latter 3 groups were H. pylori positive; Supplementary Table 1). In this study, we compared the H. pylori–negative and H. pylori–positive groups. The array chipset contained 50 599 total probe sets, and the expression levels of 2354 probe set (4.6%) changed >2-fold in the presence of H. pylori infection (1721 genes were upregulated, and 633 genes were downregulated; Supplementary Table 2). TLR10 was upregulated 15.4-fold in H. pylori–infected gastric mucosa; the fold upregulation was higher than that of IL-8 (13.6-fold), which is used to confirm upregulation in response to H. pylori infection. Among the TLRs, we found that TLR2, TLR4, TLR6, TLR7, TLR8, TLR9, and TLR10 were upregulated >2-fold (Table (Table1).1). TLR10 showed the greatest increase in the samples from both countries: 23.5-fold in Bhutan and 10.2-fold in the Dominican Republic (Table (Table11).

Table 1.

Microarray Analysis of Toll-like Receptor (TLR) Messenger RNA (mRNA) Expression

| Gene Symbol | Probe ID | Total | Bhutan | Dominican Republic | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P Value | Fold Change, Meana | P Value | Fold Change, Meana | P Value | Fold Change, Meana | ||

| TLR1 | A_23_P10873 | .01 | 1.42 | 4.31 × 10 − 03 | 1.75 | .44 | 1.16 |

| TLR2 | A_23_P92499 | 5.27 × 10 − 07 | 3.10 | 1.39 × 10 − 04 | 3.00 | 1.61 × 10 − 05 | 3.21 |

| TLR3 | A_23_P29922 | .56 | 0.94 | .84 | 0.97 | .53 | 0.92 |

| TLR4 | A_24_P69538 | 6.22 × 10 − 06 | 2.49 | 3.22 × 10 − 05 | 2.29 | 1.29 × 10 − 04 | 2.73 |

| TLR5 | A_23_P85903 | .65 | 0.94 | .93 | 1.02 | .47 | 0.87 |

| TLR6 | A_23_P256561 | 6.00 × 10 − 04 | 2.67 | 4.46 × 10 − 06 | 4.25 | .25 | 1.69 |

| TLR7 | A_23_P85240 | 3.28 × 10 − 09 | 4.36 | 1.11 × 10 − 06 | 5.18 | 1.32 × 10 − 04 | 3.69 |

| TLR8 | A_23_P73837 | 3.71 × 10 − 06 | 4.25 | 2.85 × 10 − 07 | 8.53 | .03 | 2.12 |

| TLR9 | A_33_P3380807 | 1.57 × 10 − 09 | 2.92 | 8.62 × 10 − 06 | 3.16 | 6.86 × 10 − 05 | 2.69 |

| TLR10 | A_33_P3383970 | 4.77 × 10 − 08 | 15.43 | 5.10 × 10 − 07 | 23.46 | 8.56 × 10 − 04 | 10.15 |

The fold change in TLR10 mRNA levels was much higher than the fold change in the mRNA levels of the other TLRs.

Abbreviation: ID, identification.

a Defined as the mean fold change between Helicobacter pylori–positive subjects and H. pylori–negative subjects in 2 separate experiments.

TLR10 mRNA Levels in the Antral Gastric Mucosa

We focused on TLR10 and measured TLR10 mRNA levels in 275 clinical samples, using quantitative RT-PCR. TLR10 mRNA levels in samples from H. pylori–positive subjects were approximately 3-fold higher than those in samples from H. pylori–negative subjects (Figure (Figure11A). The difference was observed in both countries (Supplementary Figure 1). The mucosal TLR10 mRNA levels from H. pylori–positive subjects were significantly positive correlation with TLR2 mRNA levels (Figure (Figure11B). The mucosal TLR10 mRNA levels were similar in cagA-negative and cagA–positive subjects from the Dominican Republic (Figure (Figure11C).

Messenger RNA (mRNA) levels for the gene encoding Toll-like receptor 10 (TLR10) in the gastric mucosa. TLR10 mRNA levels were measured with real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and normalized to the housekeeping gene encoding β-actin. Statistical analyses were calculated with the Mann–Whitney U test. A, Helicobacter pylori–negative (n = 113) and H. pylori–positive (n = 180) subjects. TLR10 mRNA levels in samples from H. pylori–positive subjects were approximately 3-fold higher than in those from H. pylori–negative subjects (median, 8.3 [range, 0.22–550] and 2.8 [range, 0.18–180], respectively; P < .001). Expression levels within the range of 0–100 are plotted in the figure. B, TLR2 mRNA levels in samples from H. pylori–positive subjects had a significantly positive correlation with TLR10 mRNA levels (R = 0.538, P < .0001). C, cagA-negative (n = 15) and cagA-positive (n = 47) subjects from the Dominican Republic. The mucosal TLR10 mRNA levels were similar in cagA-negative and cagA-positive subjects from the Dominican Republic (median = 5.9 [range, 0.96–39] and 7.1 [range, 0.6–162], respectively; P = .19). We could not compare the mucosal TLR10 mRNA levels of Bhutanese subjects according to cagA status because all H. pylori–infected Bhutanese subjects were cagA positive. *P < .0001. Abbreviation: NS, not significant.

Immunohistochemical Analysis

Using immunohistochemical analysis, we examined which cells expressed TLR10. TLR10 staining was primarily observed in the epithelial cells of H. pylori–infected mucosa, although some infiltrating cells were also stained (Figure (Figure2).2). In contrast, TLR10–positive cells were rare in the uninfected gastric mucosa.

Immunohistochemical analysis of Toll-like receptor 10 (TLR10) in the gastric mucosa. Sections of paraffin-embedded tissues from Helicobacter pylori–infected and uninfected subjects showed TLR10 staining mainly on epithelial cells. Images in the left column were obtained at an original magnification ×100 (scale bar, 250 µm), and images in the right column were obtained at an original magnification ×400 (scale bar, 100 µm). A, Subject with H. pylori infection and chronic gastritis. B, Subjects with H. pylori infection and intestinal metaplasia gastritis. C, Subject without H. pylori infection.

TLR10 mRNA Expression in NCI-N87 Epithelial Cells in Response to H. pylori Infection

Because TLR10 was mainly produced by epithelial cells, we used the highly differentiated and naturally polarized NCI-87 gastric epithelial cell line to examine TLR10 mRNA levels following infection with H. pylori for 24 hours. TLR10 mRNA levels in cells infected with strains 26 695 and TN2GF4 were significantly higher than in uninfected cells (Figure (Figure33A). TLR10 mRNA levels increased in a time-dependent manner after the infection (Figure (Figure33B). TLR10 mRNA levels in infected cells with H. pylori at 6 hours were also higher than in uninfected cells; however, the differences were not statistically significant, probably because of the small number of experiments. The increases in TLR1, TLR2, TLR6, and TLR10 mRNA levels were MOI dependent (Figure (Figure33C). TLR10 mRNA levels significantly correlated with TLR2 mRNA levels (Pearson R = 0.867; P < .001; Figure Figure33D).

Messenger RNA (mRNA) levels for the gene encoding Toll-like receptor 10 (TLR10) in NCI-N87 epithelial cells in response to H. pylori infection. A, TLR10 mRNA levels in NCI-N87 cells. Cells were infected with H. pylori strains 26 695 and TN2GF4 at multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100 for 24 hours. Mean TLR10 mRNA levels (±standard deviation [SD]) in cells infected with strains 26 695 and TN2GF4 were significantly higher than in uninfected cells (cells infected with strain 26695, 19.5 ± 4; cells infected with strain TN2GF4, 11.2 ± 4; and uninfected cells, 1.6 ± 3 [P < .001 and P < .05, respectively). Error bars represent the SD of values obtained from 3 experiments. Statistical differences between treated and control samples were analyzed using the Student t test. **P < .001 and *P < .05. B, Kinetics of H. pylori–induced TLR10 mRNA expression in NCI-N87 epithelial cells. TLR10 mRNA levels in H. pylori–infected and noninfected NCI-N87 cells were measured at a MOI of 100 for 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 hours. Error bars represent the SD of values obtained from 3 experiments. Statistical differences between treated and control samples were analyzed using the Student t test. *P < .05. C, TLR mRNA levels according to H. pylori MOI. TLR1, TLR2, TLR6, and TLR10 mRNA levels in H. pylori–infected (MOIs, 10, 100, and 500) and noninfected NCI-N87 cells after 24 hours. TLR1, TLR2, TLR6, and TLR10 showed MOI-dependent increases (mean fold change after H. pylori infection at MOIs of 10, 100, and 500: TLR1, 0.60, 0.50, and 0.83, respectively; TLR2, 0.94, 6.52, and 199.0, respectively; TLR6, 0.58, 1.73, and 16.7, respectively; and TLR10, 1.55, 16.6, and 421.0, respectively). Results are mean ± SD (n = 3 for each group). *P < .05 vs noninfected cells, **P < .001 vs noninfected cells. D, Correlation coefficient for TLR10 and TLR2 mRNA levels. TLR10 and TLR2 mRNA levels in NCI-N87 cells after H. pylori infection. There was a positive correlation between TLR10 mRNA levels and TLR2 mRNA levels. The correlation coefficient was calculated as the Pearson product moment correlation coefficient. *P < .001. E, TLR10 mRNA levels in noninfected NCI cells, NCI-N87 cells infected with live H. pylori, and NCI-N87 cells cultured with the supernatant from the medium of infected cells. For the latter, the culture medium of H. pylori–infected NCI-87 cells (MOI of 100 for 24 hours) was filtered through a 0.2-µm filter, and 50% of the supernatant was added to the medium of NCI-N87 cells. TLR10 mRNA levels in cells infected with live H. pylori 26 695 were markedly higher than in mock-infected cells. Abbreviation: NS, not significant.

To determine whether the upregulation of TLR10 mRNA was induced by surface components of H. pylori or by secreted materials (eg, H. pylori toxins such as VacA, and various cytokines secreted from the infected NCI-N87 cells), we compared the effects of live H. pylori infection with the effects of supernatants derived from cell–H. pylori coculture medium (Figure (Figure33E). TLR10 mRNA levels in cells infected with live H. pylori 26 695 were markedly higher (20.7 ± 2-fold greater, compared with mock-infected cells) than in cells treated with supernatant from infected cells (2.03 ± 2-fold, compared with mock-infected cells; P < .001 for each comparison), suggesting that direct contact with surface components of H. pylori plays a role in the upregulation of TLR10 expression.

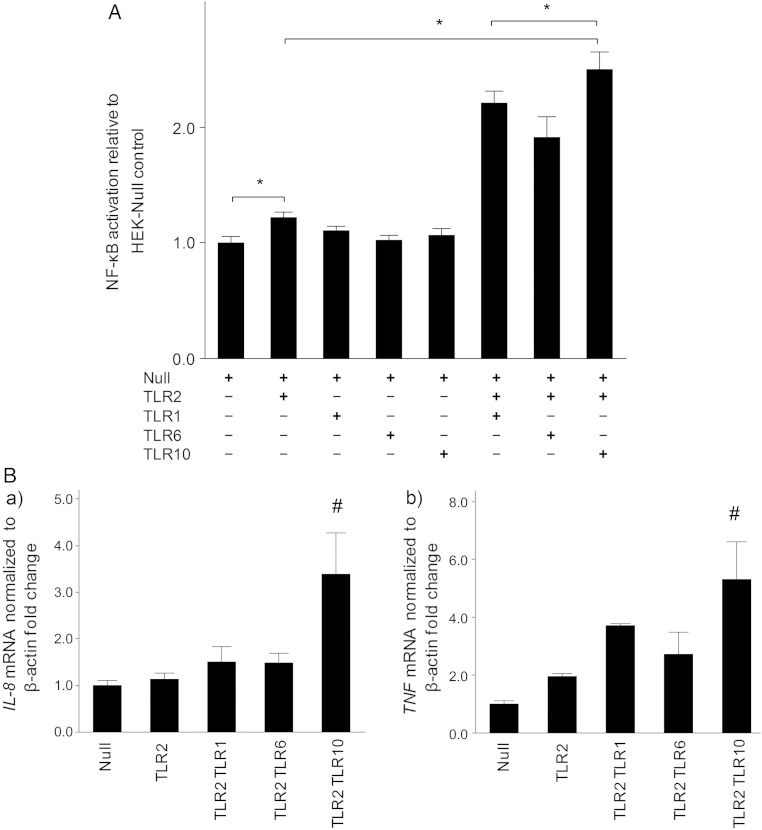

Heat-Killed H. pylori Stimulates NF-κB Activation and Cytokine Induction via TLRs

We next investigated which components acted as ligand(s) for TLR10. We used HEK-Null, HEK-TLR2, HEK-TLR1, HEK-TLR6, HEK-TLR10, HEK-TLR2/TLR1, HEK-TLR2/TLR6, and HEK-TLR2/TLR10 cells, based on findings that TLR10 forms a heterodimer with TLR2 [29, 30]. Relative NF-κB activation was significantly greater in HEK-TLR2/TLR10 cells than in other HEK-TLR combinations (Figure (Figure44A). This phenomenon was also observed when cells were exposed to heat-killed H. pylori 26 695Δcag PAI (data not shown).

Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activation and cytokine induction stimulated by heat-killed Helicobacter pylori via Toll-like receptors (TLRs). A, NF-κB activation. HEK-TLR cell lines carrying an NF-κB–inducible secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase reporter plasmid were stably transfected with the plasmid combinations indicated and then were or were not infected with H. pylori for 24 hours. The cell-free supernatants were then collected for quantification of NF-κB activation, using the colorimetric QUANTI-Blue detection method. Mean relative NF-κB activation (±standard deviation [SD]) in HEK-TLR2/TLR10 cells was significantly higher than in other combinations of the TLR2 subfamily (Null, 1.00 ± 0.09; TLR2, 1.21 ± 0.07; TLR1, 1.10 ± 0.06; TLR6, 1.02 ± 0.06; TLR10, 1.06 ± 0.09; TLR2/TLR1, 2.20 ± 0.17; TLR2/TLR6, 1.91 ± 0.30; and TLR2/TLR10, 2.50 ± 0.25. *P < .05 (n = 3). B, Cytokine induction. a, mRNA levels of the gene encoding interleukin 8 (IL-8) in HEK-TLR cells. Mean relative IL-8 mRNA levels (±SD) in HEK-TLR2/TLR10 cells were significantly higher than in the other cell lines (Null, 1.00 ± 0.18; TLR2, 1.13 ± 0.21; TLR2/TLR1, 1.50 ± 0.55; TLR2/TLR6, 1.48 ± 0.35; and TLR2/TLR10, 3.38 ± 1.52). B, mRNA levels of the gene encoding tumor necrosis factor (TNF) in HEK-TLR cells. Mean relative TNF mRNA levels (±SD) in HEK-TLR2/TLR10 cells were higher than in the other cell lines (Null, 1.00 ± 0.17; TLR2, 1.93 ± 0.16; TLR2/TLR1, 3.71 ± 0.10; TLR2/TLR6, 2.72 ± 1.31; and TLR2/TLR10, 5.31 ± 2.23). #P < .05 vs the other HEK-TLRs.

We examined cytokine expression in HEK-TRL cells stimulated with heat-killed H. pylori. The relative levels of IL-8 and TNF mRNA in HEK-TLR2/TLR10 cells were significantly higher than those in the other HEK-TLR combinations (Figure (Figure44B).

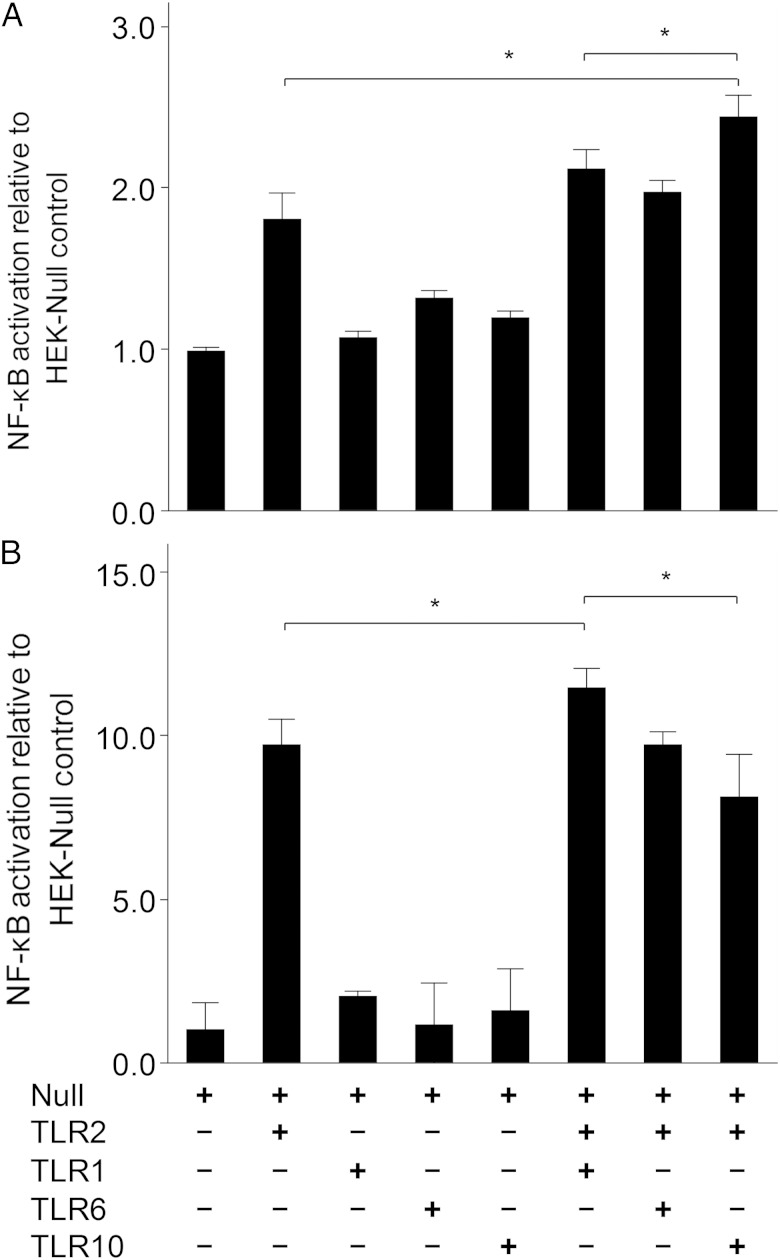

Stimulation of NF-κB Activation by H. pylori LPS Is Mediated by TLRs

To investigate which components of H. pylori acted as a ligand for the TLR2/TLR10 heterodimer, we used experiments as described by Govindaraj et al [31] to assess whether lipopeptide was a ligand for TLR10 with TLR2. We focused on H. pylori LPS (see “Discussion” section).

We examined NF-κB activation after stimulation of HEK-Null, HEK-TLR2, HEK-TLR1, HEK-TLR6, HEK-TLR10, HEK-TLR2/TLR1, HEK-TLR2/TLR6, and HEK-TLR2/TLR10 cells with H. pylori LPS (20 µg/mL) and Pam3CSK4 (100 ng/mL). Pam3CSK4 is a synthesized lipopeptide and ligand of the TLR2/TLR1 heterodimer. The relative NF-κB activation induced by H. pylori LPS was higher in TLR2/TLR10 cells than in cells expressing other HEK-TLR combinations (Figure (Figure55A). The relative NF-κB activation induced by Pam3CSK4 (100 ng/mL) was greatest in TLR2/TLR1 cells (Figure (Figure55B) in other HEK-TLR combinations.

Nuclear factor–κB (NF-κB) activation stimulated by Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide (LPS) via Toll-like receptors (TLRs). The HEK-TLR cell lines carrying an NF-κB–inducible secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase reporter plasmid were stably transfected with the plasmid combinations indicated and then stimulated with ligand for 24 hours. The experiment was performed using a transient TLR transfection method. A, H. pylori LPS (20 µg/mL). B, Pam3CSK4 (100 ng/mL). Mean relative NF-κB activation (±SD) induced by H. pylori LPS in TLR2/TLR10 cells was significantly higher than in cells lines expressing other receptor combinations (Null, 1.00 ± 0.03; TLR2, 1.80 ± 0.28; TLR1, 1.07 ± 0.06; TLR6, 1.31 ± 0.08; TLR10, 1.19 ± 0.06; TLR2/TLR1, 2.11 ± 0.20; TLR2/TLR6, 1.97 ± 0.12; and TLR2/TLR10, 2.43 ± 0.23).

DISCUSSION

Since the discovery of TLRs in 1997 [32], ligands have been identified for all TLRs, with the exception of TLR10 [33]. TLRs are sensors in the innate immune system that recognize conserved microbial structures (eg, LPS, lipoteichoic acid, and flagellin), resulting in increased production of inflammatory mediators by macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells, and epithelial cells. TLRs bridge innate immunity and acquired immunity. Recently, studies have indicated that TLR10 is involved in the induction of the innate immune response to Listeria [29] and influenza virus infection, with TLR10 mRNA levels increased in vitro [34]. However, no reports describing clinical samples or the TLR10 ligand are yet available.

In this study, we used microarray analysis to investigate the innate immune response to H. pylori infection in humans. Generally, the induction of TLR mRNA levels is TRL ligand specific [35–38]. We confirmed that TLR10 mRNA levels increased in H. pylori–infected gastric mucosa. Immunohistochemical analyses showed that TLR10 was primarily expressed in gastric epithelial cells. TLR10 mRNA levels were independent of the cagA status. We examined H. pylori infection by using the NTC-N87 cell line, a highly differentiated and naturally polarized gastric epithelial cancer cell line. TLR10 mRNA levels increased in an MOI-dependent manner following H. pylori attachment to the cells. We used HEK cells stimulated with heat-killed H. pylori to identify which TLRs were responsible for the increase in TLR10 mRNA levels. NF-κB activity was highest in HEK-TLR2/TLR10 cells, and the increase in activity was statistically significant when compared to activity in cells expressing other HEK-TLR combinations.

Finally, we considered H. pylori LPS as a candidate ligand because it is reportedly recognized by TLR2. Many studies of TLR2 have shown that LPS can combine with either TLR1 or TLR6; this interaction is essential for effective ligand binding by TLR2 and for discriminating between triacyl and diacyl lipopeptides from different bacteria [39]. We hypothesized that TLR10 would also form a heterodimer with TLR2. H. pylori LPS has a unique structure with a tetra-acyl chain lipid A region [9, 11]. Tetra-acyl lipid A might be a ligand for TLR2/TLR10. Of note, LPS from Francisella tularensis contains tetra-acyl lipid A, and the GEO database (GDS3298) reports that TLR10 mRNA levels are elevated in F. tularensis infection.

The structure of H. pylori LPS is thought to have evolved to help the bacterium evade the host innate immune system, thus facilitating its ability to cause chronic infections [9, 40]. Our data suggest the H. pylori tetra-acyl lipid A is recognized by a complex of TLR2 and TLR10, similar to triacyl lipopeptide recognized by TLR2/TLR1 and diacyl lipopeptide recognized by TLR2/TLR6. However, a structural analysis will be required to establish whether the tetra-acyl chain is in fact a ligand of TLR2/TLR10.

A recent GWAS meta-analysis identified a putative association between the TLR1-TLR6-TLR10 locus and H. pylori seroprevalence. The conclusion was based on the association of the TLR1/TLR6/TLR10 locus on chromosome 4p14 with H. pylori seroprevalence [15]. The single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs10004195 was used as the lead SNP and interpreted as indicative of an association with TLR1. However, rs10004195 also belongs to TLR10, as illustrated in the Human Genome Resources database (National Center for Biotechnology Information; available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). A review of the data published in support of the observation revealed the presence of rs10004195, as well as a number of SNPs belonging to TLR10 (eg, rs12233670, rs7653908, rs7658893, and rs11725309). The original report likely focused on TLR1 because TLR1 mRNA levels in whole blood were exclusively differentially expressed with respect to the rs10004195 genotype. We speculate that this result represents a local response to H. pylori infection, rather than a systemic response. In the discussion, the authors of the GWAS article noted that H. pylori LPS is a triacylated lipid A recognized by TLR1, citing an article [41] that described H. pylori LPS extracted from clinical strains 206. However, reinvestigation were performed by same group and found the tetra-acyl form of H. pylori 206 [42]. Therefore, tetra-acylated lipid A have been identified as the major components of H. pylori LPS [9, 11]. Our microarray data from H. pylori–infected human stomachs showed that the fold increase in TLR10 expression was the highest among the TLRs and that the relative levels of TLR10 mRNA were significantly higher than the relative levels of TLR1 mRNA in clinical samples (Table (Table1)1) and in the cell lines tested (Figure (Figure33C). We suggest that the published association between TLR1 and H. pylori seroprevalence points to TLR10, rather than to TLR1 and that TRL10, is an important factor in H. pylori infection and disease pathogenesis. Furthermore, several studies [43] support the notion that positive selection has targeted the TLR1-TLR6-TLR10 gene cluster in humans. Variation in this genomic region has been linked to disease phenotypes TLR1 and TLR6 [16, 17], respectively. It is also expected that TLR10 would link to disease phenotype for its own pathogens. Further works are needed to validate TLR10 and disease phenotype. In conclusion, TLR10 acts a functional receptor in the innate immune response to H. pylori infection and recognizes H. pylori LPS associated with TLR2.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online (http://jid.oxfordjournals.org). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank Dr Lotay Tshering (Department of Surgery, Jigme Dorji Wangchuk National Referral Hospital, Thimphu, Bhutan), Dr Mildre Disla (Dominican-Japanese Friendship Medical Education Center, Dr Luis E. Aybar Health and Hygiene City, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic), Dr Seiji Shiota (Department of Environmental and Preventive Medicine, Oita University Faculty of Medicine, Yufu, Japan), and Dr Lourdes Tronilo and Dr Eduardo Rodríguez (Dominican-Japanese Digestive Disease Center, Dr Luis E. Aybar Health and Hygiene City).

We thank Dr Lotay Tshering (Department of Surgery, Jigme Dorji Wangchuk National Referral Hospital, Thimphu, Bhutan), Dr Mildre Disla (Dominican-Japanese Friendship Medical Education Center, Dr Luis E. Aybar Health and Hygiene City, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic), Dr Seiji Shiota (Department of Environmental and Preventive Medicine, Oita University Faculty of Medicine, Yufu, Japan), and Dr Lourdes Tronilo and Dr Eduardo Rodríguez (Dominican-Japanese Digestive Disease Center, Dr Luis E. Aybar Health and Hygiene City).

Disclaimer. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Veterans Administration or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Veterans Administration or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Financial support. This work was supported by the NIH (DK62813 and DK56338, which funds the Texas Medical Center Digestive Diseases Center), the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (grants in aid for scientific research 24406015, 24659200, 25293104, and 26640114), the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Strategic Young Researcher Overseas Visits Program for Accelerating Brain Circulation), the Japan Science and Technology Agency (Strategic Funds for the Promotion of Science and Technology), and the Dominican Republic Ministry of Higher Education Science and Technology (National Fund for Innovation and Scientific and Technological Development).

This work was supported by the NIH (DK62813 and DK56338, which funds the Texas Medical Center Digestive Diseases Center), the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (grants in aid for scientific research 24406015, 24659200, 25293104, and 26640114), the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Strategic Young Researcher Overseas Visits Program for Accelerating Brain Circulation), the Japan Science and Technology Agency (Strategic Funds for the Promotion of Science and Technology), and the Dominican Republic Ministry of Higher Education Science and Technology (National Fund for Innovation and Scientific and Technological Development).

Potential conflicts of interest. D. Y. G. is an unpaid consultant for Novartis in relation to vaccine development for the treatment or prevention of H. pylori infection, is a paid consultant for RedHill Biopharma regarding novel H. pylori therapies and has received research support for the culture of H. pylori, is a consultant for Otsuka Pharmaceuticals regarding diagnostic breath testing, and has received royalties from Baylor College of Medicine for patents covering materials related to a 13C-urea breath test. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

D. Y. G. is an unpaid consultant for Novartis in relation to vaccine development for the treatment or prevention of H. pylori infection, is a paid consultant for RedHill Biopharma regarding novel H. pylori therapies and has received research support for the culture of H. pylori, is a consultant for Otsuka Pharmaceuticals regarding diagnostic breath testing, and has received royalties from Baylor College of Medicine for patents covering materials related to a 13C-urea breath test. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

Articles from The Journal of Infectious Diseases are provided here courtesy of Oxford University Press

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiv270

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc4621249?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1093/infdis/jiv270

Article citations

TLR10 (CD290) Is a Regulator of Immune Responses in Human Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells.

J Immunol, 213(5):577-587, 01 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38995177

Implications of lncRNAs in Helicobacter pylori-associated gastrointestinal cancers: underlying mechanisms and future perspectives.

Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 14:1392129, 05 Jul 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39035354 | PMCID: PMC11257847

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Toll-like receptors in breast cancer immunity and immunotherapy.

Front Immunol, 15:1418025, 06 Jun 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38903515 | PMCID: PMC11187004

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

The immunopathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric cancer: a narrative review.

Front Microbiol, 15:1395403, 05 Jul 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 39035439 | PMCID: PMC11258019

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

TLR10: An Intriguing Toll-Like Receptor with Many Unanswered Questions.

J Innate Immun, 16(1):96-104, 19 Jan 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38246135 | PMCID: PMC10861218

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (50) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

GEO - Gene Expression Omnibus

- (1 citation) GEO - GDS3298

SNPs (5)

- (1 citation) dbSNP - rs7658893

- (1 citation) dbSNP - rs11725309

- (1 citation) dbSNP - rs10004195

- (1 citation) dbSNP - rs12233670

- (1 citation) dbSNP - rs7653908

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 induced through TLR4 signaling initiated by Helicobacter pylori cooperatively amplifies iNOS induction in gastric epithelial cells.

Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol, 293(5):G1004-12, 13 Sep 2007

Cited by: 58 articles | PMID: 17855767

Genetic polymorphisms in TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, and TLR10 of Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis: a prospective cross-sectional study in Thailand.

Eur J Cancer Prev, 27(2):118-123, 01 Mar 2018

Cited by: 20 articles | PMID: 28368946 | PMCID: PMC5802262

Toll-like receptor 2: An important immunomodulatory molecule during Helicobacter pylori infection.

Life Sci, 178:17-29, 18 Apr 2017

Cited by: 19 articles | PMID: 28427896

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

Dominican Republic Ministry of Higher Education Science and Technology (National Fund for Innovation and Scientific and Technological Development)

NIDDK NIH HHS (4)

Grant ID: R01 DK062813

Grant ID: P30 DK056338

Grant ID: DK62813

Grant ID: DK56338

NIH (1)

Grant ID: DK62813 and DK56338

the Japan Science and Technology Agency (Strategic Funds for the Promotion of Science and Technology)

the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Strategic Young Researcher Overseas Visits Program for Accelerating Brain Circulation)

the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (1)

Grant ID: 24406015, 24659200, 25293104, and 26640114