Abstract

Free full text

Immune activation and response to pembrolizumab in POLE-mutant endometrial cancer

Abstract

Antibodies that target the immune checkpoint receptor programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) have resulted in prolonged and beneficial responses toward a variety of human cancers. However, anti–PD-1 therapy in some patients provides no benefit and/or results in adverse side effects. The factors that determine whether patients will be drug sensitive or resistant are not fully understood; therefore, genomic assessment of exceptional responders can provide important insight into patient response. Here, we identified a patient with endometrial cancer who had an exceptional response to the anti–PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab. Clinical grade targeted genomic profiling of a pretreatment tumor sample from this individual identified a mutation in DNA polymerase epsilon (POLE) that associated with an ultramutator phenotype. Analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) revealed that the presence of POLE mutation associates with high mutational burden and elevated expression of several immune checkpoint genes. Together, these data suggest that cancers harboring POLE mutations are good candidates for immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy.

Introduction

Prolonged and deep responses to antibody therapy directed against the immune checkpoint programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) receptor have been demonstrated in multiple types of human cancer (1–7). However, objective responses are seen in less than half of patients treated, and the potential for serious side effects exists. Combination immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy raises response rates, but also increases toxicity and cost (8, 9). There is a clear need for identifying biomarkers of response to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy, particularly if these markers can select the subset of patients who will require only single-agent anti–PD-1 therapy.

High expression of the programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) is under investigation as a potential predictor of response to anti–PD-1 therapy. However, while patients with higher PD-L1 expression may experience greater benefit, a subset of patients with PD-L1–negative cancers sustain important responses (5, 8, 10). Thus, the discovery of additional predictive markers may complement the utility of assessment of PD-L1 expression.

Several emerging studies demonstrate that tumors with high mutational burdens exhibit a greater response rate to immune checkpoint blockade (11–14). Here, we report the genomic analysis of what we believe is the first known case of a patient with endometrial cancer who experienced a prolonged response to pembrolizumab therapy in a clinical trial. Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified (CLIA-certified) targeted genomic profiling of a pretreatment biopsy specimen revealed that this tumor had a mutation in the DNA polymerase epsilon (POLE) gene. This POLE mutation is associated with disruption of the exonuclease activity required for proofreading function and results in a high mutational burden or “ultramutator” phenotype (15, 16). POLE mutations are seen in approximately 10% of endometrial cancers and are associated with increased expression of PD-1 and PD-L1, additional T cell markers (16–20), and robust lymphocytic infiltration. These data suggest that presence of POLE mutations may identify a subset of cancers especially vulnerable to immune checkpoint therapy.

Results and Discussion

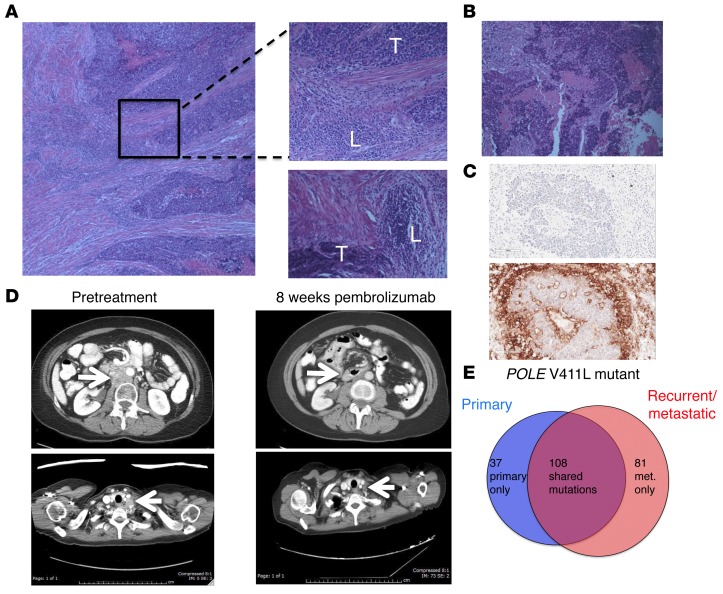

A 53-year-old woman presenting with irregular vaginal bleeding was treated with hysterectomy and diagnosed with a pT1b pN0, stage IB, FIGO grade III endometrial adenocarcinoma, high-grade endometrioid type, with extensive necrosis, lymphovascular invasion, and myometrial invasion. A peritumoral lymphocytic infiltrate was readily apparent (Figure 1A) in her tumor. Her oncologic family history included 2 brothers with prostate cancer, aged 55 and 67 years at diagnosis, a father with a form of brain cancer who died from this disease at age 54 years, and a maternal aunt who was diagnosed with colon cancer at age 54 years and lymphoma, type unknown, a few years later. The patient deferred radiation therapy and, in follow-up, rapidly developed new retroperitoneal adenopathy, with biopsy showing recurrent cancer. She was treated with doxorubicin, cisplatin, paclitaxel, and extended-field radiotherapy. Two years later, she developed supraclavicular adenopathy that, when biopsied, revealed recurrent metastatic adenocarcinoma (Figure 1B). In the process of performing screening tests to determine the eligibility of the patient for a clinical trial of pembrolizumab, this metastasis was found to be positive for PD-L1 expression (Figure 1C) using a prototype immunohistochemical (IHC) assay as previously described (21). CT scans showed bulky retroperitoneal and abdominal lymphadenopathy encasing the inferior vena cava (Figure 1D). She soon developed extensive bilateral lower extremity edema, interfering with her daily activities and quality of life.

(A) Histology from surgical resection of primary endometrial cancer. Top inset shows region of peritumoral lymphocytic infiltration; bottom inset shows separate region with peritumoral lymphocytic micronodules. Original magnification, ×10 (left); ×20 (right). T, tumor; L, lymphocytic infiltrate. (B) Histology from supraclavicular LN biopsy taken 4 years after original diagnosis. Original magnification, ×20. (C) Sections of LN metastasis: hematoxylin counterstain (negative control; top image); IHC staining with anti–PD-L1 antibody clone 22C3 (Merck) (bottom image). Original magnification, ×20. (D) Representative abdominal (top) and thoracic (bottom) CT images taken prior to pembrolizumab treatment and 8 weeks after initiation of therapy. Arrows highlight paraaortic and supraclavicular tumor masses, which substantially decreased. (E) Number of nonsynonymous somatic variants, including somatic variants of unknown significance, found in 315 cancer-related genes shown for primary and recurrent tumor samples.

The patient enrolled in a phase I trial of pembrolizumab (10 mg/kg every 2 weeks) for patients with tumors harboring PD-L1 expression. She experienced rapid clinical improvement, with resolution of lower extremity edema, supraclavicular adenopathy, and a partial response at 8 weeks following treatment initiation, sustained, at this writing, for over 14 months (Figure 1D). She tolerated therapy well, with grade 1 rash, grade 1 liver function test elevation, and grade 2 fever early in her treatment course that resolved spontaneously. She provided informed consent to participate in the Rutgers CINJ genomic tumor–profiling protocol.

The primary endometrial cancer specimen and the recurrent supraclavicular lymph node (LN) metastasis obtained prior to treatment were sent for hybrid-capture–based comprehensive genomic profiling, targeting all exons of 315 cancer-related genes at a CLIA-certified laboratory (Foundation Medicine). There were 32 sequence variants identified as likely pathogenic in the primary tumor and 33 potentially pathogenic variants identified in the LN recurrence; 28 changes were present in both samples (Table 1). Both samples harbored a mutation in the exonuclease domain of POLE that affects proofreading function (V411L) as well as a separate nonsense mutation in POLE (R114*), consistent with inactivation of the WT allele; these features are associated with an ultramutator phenotype (15, 16, 20). The presence of 32 and 33 potentially pathogenic mutations represents an exceptionally high mutation frequency. In addition, there were a large number of single-nucleotide variants classified as variant of unknown significance (VUS): 116 in the primary sample and 159 in the recurrence, with 83 VUS shared between the tumors. Sequencing of germline DNA performed on the same platform demonstrated that only 3 of the variants identified in both tumor samples were also present in the germline DNA (see Supplemental Methods and Supplemental Table 1; supplemental material available online with this article; 10.1172/JCI84940DS1). All 3 germline variants had been classified as VUS in tumor sequencing. The remaining mutations identified in tumor sequencing, including POLE mutations and all variants identified as potentially pathogenic, were somatic mutations. The distribution of shared and private somatic mutations in the 2 samples is shown in Figure 1E. This number of somatic mutations found in the set of 315 genes assayed can be extrapolated to an estimated total mutational burden of approximately 4,500 and 6,500 nonsynonymous mutations in the whole exome in the primary and metastatic samples, respectively. These estimates are consistent with the high mutational burden and ultramutator phenotype reported for POLE-mutant endometrial cancers (15, 16, 20).

Table 1

To further investigate the mutational burden in endometrial cancers, data from a set of 252 deidentified endometrial cancers sequenced using the FoundationOne assay were analyzed. Twenty-three (9.1%) of these mostly advanced/metastatic endometrioid endometrial cancers had sequence variants in POLE. In this subset, the mean numbers of variants identified as likely pathogenic and VUS were 21.2 ± 4.1 and 82.2 ± 25, respectively, compared with mean values of 7.5 ± 0.5 likely pathogenic variants and 12.8 ± 2.6 VUS in POLE-WT cases (P < 0.005 and P = 0.015, respectively). Thus, similarly to The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) findings in mostly primary endometrial cancers, a clear subset of advanced/recurrent endometrial cancers also harbor POLE mutations and are associated with a high mutational burden.

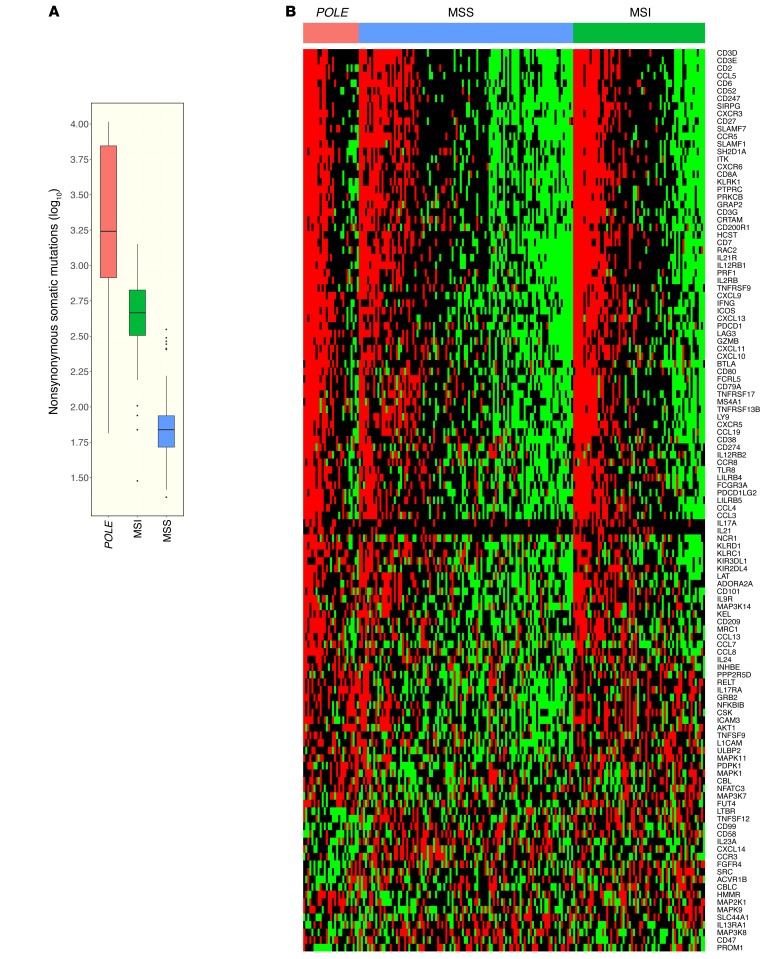

Endometrial cancers harboring POLE mutations, approximately 10% of endometrial cancers analyzed in TCGA (20), have a much higher nonsynonymous mutational burden than other classes of endometrial cancers, including those with a microsatellite instability (MSI) phenotype (Figure 2A). To determine whether POLE-mutant cancers were associated with an immune signature, we analyzed RNA-sequencing data from endometrioid endometrial cancer that was previously deposited in TCGA (20). Serous endometrial cancers were not included, as they appear to be a distinct class of cancers with different patterns of mutations and copy number alterations (20). Endometrioid endometrial cancers were divided into 3 categories: (a) POLE-mutant cancer, (b) POLE-WT tumors with MSI phenotype, and (c) POLE-WT tumors with microsatellite stable (MSS) phenotype. A heat map of differentially expressed immune-related genes (Figure 2B) demonstrated that POLE-mutant endometrioid endometrial cancers have high expression of a large set of immune-related genes compared with MSS cancers. The MSI tumors appear to have an intermediate phenotype, having lower expression of immune signature genes than POLE-mutant tumors, but higher than MSS tumors.

(A) The relative numbers of nonsynonymous mutations found in POLE-mutant, MSI, and MSS endometrial cancers. (B) Heat map showing relative expression of differentially expressed immune-related genes in POLE-mutant, MSI, and MSS endometrial cancers. Number of samples: 27 POLE, 64 MSI, 104 MSS. Box plots (shown in A) use the following default convention: the horizontal line represents the median value, the box covers the interquartile range (IQR), the whiskers cover values within 1.5 IQR beyond the box, and values beyond 1.5 IQR are represented as dots.

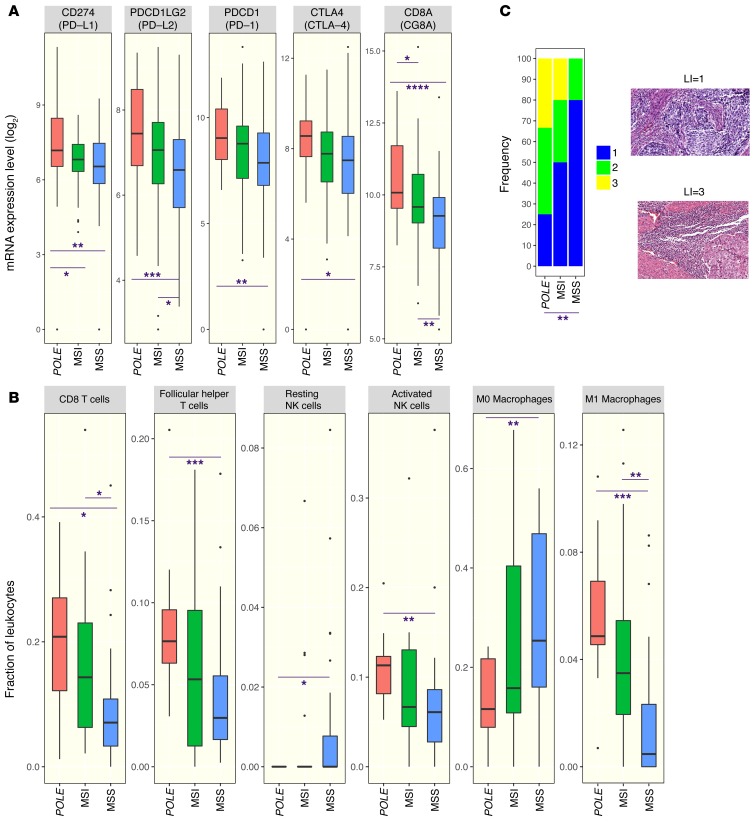

In the TCGA data set, POLE-mutant cancers have higher expression of several genes encoding for immune checkpoint-related proteins, including PD-L1 and PD-L2, than either MSI or MSS endometrioid cancers (Figure 3A). Similarly, POLE-mutant cancers also showed higher expression of T cell markers such as CD8A, PD-1, and cytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein-4 (CTLA-4) (Figure 3A), suggesting the presence of a preexisting T cell infiltrate. An estimate of leukocyte subsets that may be contributing to the immune gene expression signature was generated using CIBERSORT (https://cibersort.stanford.edu/) (22). As shown in Figure 3B, POLE mutant endometrial cancers had significantly higher estimated proportions of CD8+ T cells, T follicular helper cells, M1 macrophages, and activated NK cells than MSS cancers, with MSI cancers having intermediate levels. There was no difference in the estimated proportion of resting or activated dendritic cells or M2 macrophages between these groups (data not shown).

(A) Expression of a set of immune checkpoint and lymphocyte-associated genes as assayed by RNA sequencing in POLE-mutant, MSI, and MSS endometrial cancers. (B) Estimated proportion representation of some leukocyte subsets, as calculated by CIBERSORT, for POLE-mutant, MSI, and MSS endometrial cancers. (C) Distribution of lymphocyte infiltration scores in histological images of a set of POLE-mutant, MSI, and MSS endometrial cancers. Representative images associated with scores of 1 and 3 are shown to the right. Original magnification, ×20. A 2-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used in all cases to determine P values. P <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Number of samples: 27 POLE, 64 MSI, 104 MSS (A); 12 POLE, 20 MSI, 28 MSS (B); 12 POLE, 10 MSI, 10 MSS (C). For the remaining samples not shown in B, CIBERSORT provided a P value ≥ 0.05. Box plots (shown in B and C) use the following default convention: the horizontal line represents the median value, the box covers the interquartile range (IQR), the whiskers cover values within 1.5 IQR beyond the box, and values beyond 1.5 IQR are represented as dots. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

To determine whether POLE-mutant status was associated with histologic presence of lymphocytic infiltration, high-resolution images of H&E-stained sections of individual endometrial cancers from TCGA were analyzed. Endometrial cancers that had POLE mutations, MSI phenotype, and MSS phenotype were analyzed in a blinded fashion and scored on a scale of 1 to 3 for the presence of lymphocytic infiltration. POLE-mutant endometrial cancers had a significantly higher extent of lymphocytic infiltration than MSS tumors; MSI tumors again had an intermediate phenotype, with a trend for more infiltration than MSS tumors but less than POLE-mutant tumors, although this did not reach statistical significance (Figure 3C).

Both POLE and DNA polymerase delta 1 (POLD1) mutations have been noted in patients with non–small cell lung cancer who are responsive to pembrolizumab and are associated with high mutational burdens (11). Furthermore, mismatch repair status has been shown to predict clinical benefit from pembrolizumab in a clinical trial of both colorectal and noncolorectal cancers (13). The mutational burden seen in POLE-mutant endometrial cancers is an order of magnitude greater than that seen in endometrial cancers with the MSI phenotype (20). Gene-expression data from the TCGA (Figures 2 and and3)3) and several recent studies also show that POLE-mutant cancers have higher expression of immune checkpoint proteins and T cell markers than MSI endometrioid endometrial cancers (17–19), suggesting that these tumors may be even more responsive to immunotherapy. Of note, the majority of POLE-mutant tumors have an MSS phenotype (23) and would not be identified by MSI assays. We propose further clinical investigation with immunotherapy specifically targeting endometrial and other cancers with POLE and POLD1 mutations, with translational clinical trials currently in development.

Methods

Tumor sequencing.

Formalin-fixed tumor samples and DNA extracted from peripheral blood specimens were analyzed by a comprehensive genomic profiling assay performed on indexed, adaptor-ligated, hybridization captured libraries targeting all exons of 315 cancer-related genes at a commercial CLIA-certified laboratory, Foundation Medicine.

Data collection and analysis.

Details regarding the source and analysis of mRNA expression data and analysis of histological images are summarized in Supplemental Methods.

Statistics.

A 2-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used in all cases to determine P values. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Study approval.

The patient described in this report was enrolled in a clinical trial conducted at CINJ. The trial was approved by an institutional review board at CINJ, and the patient provided informed consent prior to study enrollment.

Author contributions

JMM drafted the manuscript, identified and treated patient, designed experiments, and interpreted data. AP designed experiments and performed computational analyses. HZ performed analyses of pathological specimens. KH provided direction on scope of analyses, interpreted data, and edited the manuscript. SD was involved in patient care. KL was involved in patient care. LS performed analyses of radiologic evidence. MNS provided direction on scope of analyses and was involved in patient care. LRR provided direction on scope of analyses and edited the manuscript. HLK provided direction on scope of analyses and edited the manuscript. SA acquired data and performed data analyses. JSR acquired data and performed data analyses. DCP performed data analyses. GB designed experiments and performed computational analyses. EPW provided direction on the scope of analyses. RSD provided direction on the scope of analyses and edited the manuscript. AL provided direction on the scope of analyses and edited the manuscript. JC provided direction on the scope of analyses and edited the manuscript. SG drafted the manuscript, designed experiments, and interpreted data. All authors have reviewed and approved the content in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Functional Genomics and Biospecimen Repository Shared Resource(s) of the Rutgers CINJ (P30CA072720) and a generous gift to the Genetics Diagnostics to Cancer Treatment Research Initiative of the Rutgers CINJ and RUCDR Infinite Biologics. Funding for this research was also provided by Merck and Co.

Footnotes

Hua Zhong’s present address is: Department of Pathology, Community Medical Center Barnabas Health, Toms River, New Jersey, USA.

Conflict of interest: J.M. Mehnert is the principal investigator for clinical trial MK-3475-028/KEYNOTE-28, funded by Merck & Co. (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02054806). H.L. Kaufman serves on a scientific advisory board and a speaker’s bureau for Merck & Co. (funds returned to Rutgers University); serves on scientific advisory boards for Alkermes, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, EMD Serono Inc., and Prometheus Laboratories Inc.; provides consulting services for Sanofi; and receives clinical trial funding from Amgen, EMD Serono Inc., Prometheus Laboratories Inc., and Viralytics. S. Ali, J.S. Ross, and D.C. Pavlik are employees of Foundation Medicine. A. Lovell and J. Cheng are employees of Merck & Co. S. Ganesan serves on a scientific advisory board and as a consultant to Inspirata and has equity in Inspirata; serves on an advisory board for Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp.; and has a patent (PCT/US2010/022891) on digital imaging technology licensed to Inspirata.

Reference information:J Clin Invest. 2016;126(6):2334–2340. 10.1172/JCI84940.

References

Articles from The Journal of Clinical Investigation are provided here courtesy of American Society for Clinical Investigation

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1172/jci84940

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

http://www.jci.org/articles/view/84940/files/pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Article citations

Pyroptosis-associated genes and tumor immune response in endometrial cancer.

Discov Oncol, 15(1):433, 12 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39264524 | PMCID: PMC11393226

Low-Risk and High-Risk NSMPs: A Prognostic Subclassification of No Specific Molecular Profile Subtype of Endometrial Carcinomas.

Cancers (Basel), 16(18):3221, 21 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39335192 | PMCID: PMC11429616

Emerging applications of hypomethylating agents in the treatment of glioblastoma (Review).

Mol Clin Oncol, 21(3):59, 28 Jun 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39006906

Review

Immune checkpoint inhibitors in colorectal cancer: limitation and challenges.

Front Immunol, 15:1403533, 11 Jun 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38919624 | PMCID: PMC11196401

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Landscape of Endometrial Cancer: Molecular Mechanisms, Biomarkers, and Target Therapy.

Cancers (Basel), 16(11):2027, 27 May 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38893147 | PMCID: PMC11171255

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (221) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Clinical Trials

- (1 citation) ClinicalTrials.gov - NCT02054806

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Tumor genotype and immune microenvironment in POLE-ultramutated and MSI-hypermutated Endometrial Cancers: New candidates for checkpoint blockade immunotherapy?

Cancer Treat Rev, 48:61-68, 18 Jun 2016

Cited by: 60 articles | PMID: 27362548

Review

Response to PD-1 Blockade in Microsatellite Stable Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Harboring a POLE Mutation.

J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 15(2):142-147, 01 Feb 2017

Cited by: 119 articles | PMID: 28188185

Utility of a custom designed next generation DNA sequencing gene panel to molecularly classify endometrial cancers according to The Cancer Genome Atlas subgroups.

BMC Med Genomics, 13(1):179, 30 Nov 2020

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 33256706 | PMCID: PMC7706212

Clinical outcomes of patients with POLE mutated endometrioid endometrial cancer.

Gynecol Oncol, 156(1):194-202, 19 Nov 2019

Cited by: 20 articles | PMID: 31757464 | PMCID: PMC6980651

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NCI NIH HHS (3)

Grant ID: R01 CA188096

Grant ID: P30 CA072720

Grant ID: R01 CA163591

1,3

1,3