Abstract

Free full text

Two Fatal Intoxications Involving Butyryl Fentanyl

Abstract

We present the case histories, autopsy findings and toxicology findings of two fatal intoxications involving the designer drug, butyryl fentanyl. The quantitative analysis of butyryl fentanyl in postmortem fluids and tissues was performed by an ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry method. In the first case, butyryl fentanyl was the only drug detected with concentrations of 99 ng/mL in peripheral blood, 220 ng/mL in heart blood, 32 ng/mL in vitreous humor, 590 ng/mL in gastric contents, 93 ng/g in brain, 41 ng/g in liver, 260 ng/mL in bile and 64 ng/mL in urine. The cause of death was ruled fatal intoxication by butyryl fentanyl. In the second case, butyryl fentanyl was detected along with acetyl fentanyl, alprazolam and ethanol. The butyryl fentanyl concentrations were 3.7 ng/mL in peripheral blood, 9.2 ng/mL in heart blood, 9.8 ng/mL in vitreous humor, 4,000 ng/mL in gastric contents, 63 ng/g in brain, 39 ng/g in liver, 49 ng/mL in bile and 2 ng/mL in urine. The acetyl fentanyl concentrations were 21 ng/mL in peripheral blood, 95 ng/mL in heart blood, 68 ng/mL in vitreous humor, 28,000 ng/mL in gastric contents, 200 ng/g in brain, 160 ng/g in liver, 330 ng/mL in bile and 8 ng/mL in urine. In addition, the alprazolam concentration was 40 ng/mL and the ethanol concentration was 0.11 g/dL, both measured in peripheral blood. The cause of death in the second case was ruled a mixed drug intoxication. In both cases, the manner of death was accident.

Introduction

Fentanyl was developed in the 1960s as a high potency synthetic µ opioid agonist that is ~50–100 times more potent than morphine (1). Due to its potency and wide availability as a prescribed drug, fentanyl has been abused and misused by health professionals, pain management patients and recreational abusers for the past several decades (2). In addition, clandestinely manufactured fentanyl analogs introduced into the illicit drug market or available from internet websites have led to clusters of fentanyl analog overdose deaths in both the USA and Europe (3). Recently, there have been several reports of fatalities involving acetyl fentanyl (Figure (Figure1,1, 4–7). Many of these case reports, however, lack postmortem toxicology findings, and the cause and manner of death were established by case history and testing of drugs found at the scene. However, a recently published case study reported a single acetyl fentanyl fatality with quantitative acetyl fentanyl findings as measured by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) (8). More recently, a larger case report presented 14 acetyl fentanyl fatalities including postmortem tissue distribution results as measured by ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC/MS/MS) (9, 10).

Newer fentanyl analogs, butyryl fentanyl (butyryl fentanyl or N-phenyl-N-[1-(2-phenylethyl)-4-piperidinyl]-butanamide, Figure Figure1),1), and 4-fluorobutyryl fentanyl (N-(4-fluorophenyl)-N-[1-(2-phenylethyl)-4-piperidinyl]-butanamide), have recently become available and have been associated with abuse and severe intoxication (11–14). Butyryl fentanyl, aka “Scooby Fentanyl”, and its fluorinated derivative have no medical uses and are currently not regulated or controlled in the USA and Europe (11–14).

There is little information about the effects of the butyryl fentanyl analogs, however, butyryl fentanyl was estimated to have 1/30th the potency of fentanyl in mice (15). The potency of 4-fluorobutyryl fentanyl is unknown, however, the fluorinated analogs are generally less potent than their respective non-fluorinated parent compounds (15). A recent case study reported an 18-year old developed diffuse alveolar hemorrhage and hypoxic respiratory failure after unknowingly snorting butyryl fentanyl in a product labeled to contain acetyl fentanyl. In this report, toxicology testing for butyryl fentanyl was not conducted. The patient survived with naloxone administration and ventilator support (16). Five non-fatal intoxications involving butyryl fentanyl and 4-fluorobutyryl fentanyl were recently reported in Sweden (11). In this report, the victims exhibited classical opioid-like clinical symptoms including decreased level of consciousness, respiratory depression, apnea, agitation, pinpoint pupils, hypothermia and tachycardia yet all survived with naloxone and/or ventilator support. Two of the victims brought the ingested substances into the hospital, one being a butyryl fentanyl powder and the other a butyryl fentanyl nasal spray. One victim indicated that they had purchased the nasal spray from a Swedish web-based novel psychoactive substance dealer. According to user experiences posted on the various drug forums, butyryl fentanyl can be administered nasally, rectally, intravenously and sublingually (17–19). Users often mention that the sublingual route of administration is less effective due to low bioavailability of butyryl fentanyl. At the time these cases occurred, there were no published butyryl fentanyl fatalities.

We present the case histories, autopsy findings and toxicology findings of two fatal intoxications involving butyryl fentanyl. One death was due solely the butyryl fentanyl and the other was a mixed drug death involving both butyryl and acetyl fentanyl as well as alprazolam and ethanol. The postmortem distribution of the fentanyl analogs in heart blood, peripheral blood, bile, brain, liver, urine and vitreous humor is also presented.

Case histories and pathological findings

Case 1

A 53-year-old female came to Florida recently to visit various friends and family. She was last seen alive going into a bathroom where she never came out. Ten minutes later her son went in to check on her and found her fully clothed, collapsed over the toilet and not breathing. 911 was called, paramedics responded and she was pronounced dead at the scene. A bowl of cereal was noted nearby on the bathroom sink. There was no evidence of licit or illicit drug use (pills, powders, capsules, spoons, straws or syringes) at the scene. She had a history of smoking, prescription drug abuse (drugs not specified) and had been hospitalized for psychiatric reasons 3 years prior to her death. Her only prescribed medication was famotidine. Autopsy findings were unremarkable except for some mild atherosclerosis and left concentric ventricular myocardial hypertrophy. The cut surfaces of the lungs were edematous, dark and red-purple with congestion and exuded a small amount of frothy liquid. The left lung weighed 450 g and the right lung weighed 510 g. The stomach contained ~750 mL of tan liquid with partially digested tan soft food fragments. No other extrinsic disease was noted.

Case 2

A 45-year-old female was last seen alive watching television in the evening. The next day, she was found unresponsive and not breathing on her bed. 911 was called, paramedics responded and she was pronounced dead at the scene. She had a history of anxiety, bipolar disorder and two previous suicide attempts. She was also known to abuse prescription drugs (oxycodone) and alcohol but had stopped using oxycodone and alcohol ~6 months prior to her death. Numerous CO2 cartridges were found at the scene; however, family members indicated that she had no history of huffing or abusing inhalants. Her prescribed medications, which included alprazolam, diazepam, promethazine, zonisamide, trazodone and topiramate, were found at the scene. The pill bottles contained the expected number of pills so overmedication was not suspected. There was no evidence of illicit drug use at the scene (spoons, straws, syringes or track marks). At autopsy, the decedent was noted to have mild left ventricular myocardial hypertrophy and mild nephrosclerosis. The cut surfaces of the lungs were edematous, dark and red-purple with congestion and exuded a large amount of frothy liquid. The left lung weighed 570 g and the right lung weighed 680 g. The stomach contained ~300 mL of blue-turquoise liquid. No other extrinsic disease was noted.

Methods

Initial toxicology screening

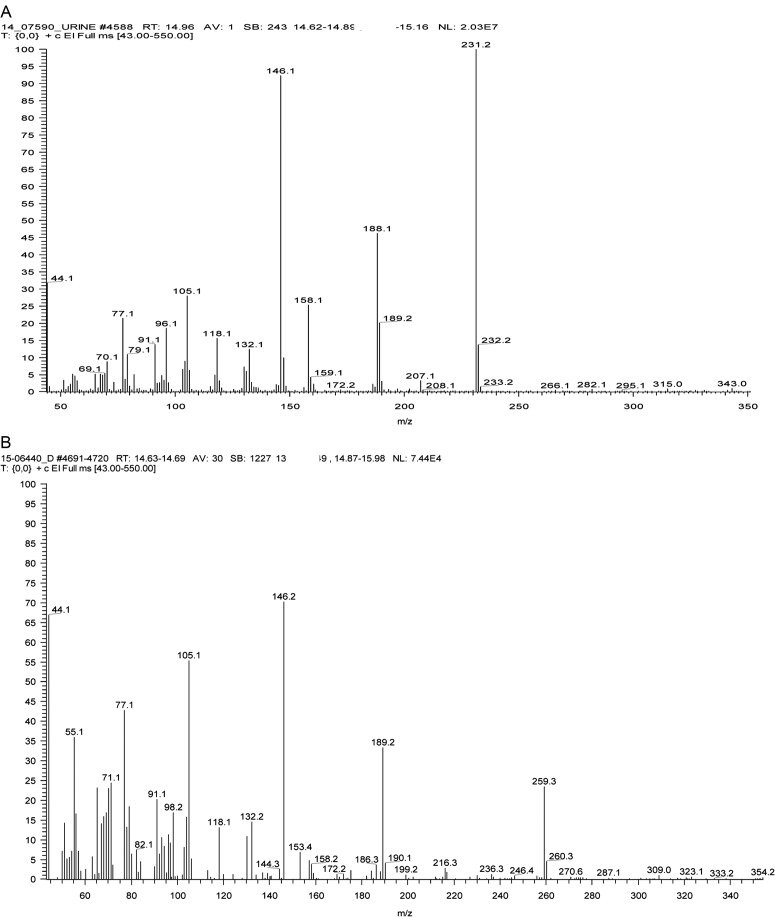

Postmortem blood, vitreous and/or urine specimens were screened for volatiles by headspace gas chromatography (GC), drugs of abuse by immunoassay (acetaminophen, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, cannabinoids, carisoprodol/meprobamate, benzoylecgonine, fentanyl, methadone, methamphetamine/3,4-methylenedioxymethampetamine, opiates, oxycodone and salicylates) and alkaline extractable drugs by full-scan GC mass/MS. In both cases, the blood immunoassay screens for fentanyl at a cut-off value of 2 ng/mL were positive (Immunalysis, Pomona, CA); however, fentanyl was not detected in either case. Acetyl fentanyl and butyryl fentanyl were isolated using a liquid/liquid extraction. Briefly, 2 mL of specimens were extracted with saturated borate buffer and THIA (78:20:2 mixture of toluene, hexane and isoamyl alcohol), back extracted with sulfuric acid, neutralized and concentrated in ethyl acetate for analysis (20). Alkaline extracts were separated chromatographically on an Rtx-5 (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm) column (Restek, Bellefonte, PA). The initial oven temperature of 100°C was held for 1 min, followed by a 15°C ramp to 230°C, then a 12°C ramp to 300°C followed by a 10-min hold. Identification was by electron impact full-scan GC/MS analysis (Figure (Figure22).

UPLC/MS/MS method for acetyl fentanyl, acetyl norfentanyl and butyryl fentanyl

Reagents

The primary reference materials for acetyl fentanyl, acetyl norfentanyl, butyryl fentanyl and their internal standards (ISTD); acetyl fentanyl-13C6, acetyl norfentanyl-13C6 and fentanyl-d5 were purchased from Cerilliant (Round Rock, TX). Ammonium formate, ammonium hydroxide, glacial acetic acid, isopropanol, methylene chloride, methanol, sodium phosphate monobasic, sodium phosphate dibasic and deionized (DI) water were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Hanover Park, IL). All reagents were ACS grade or better. SPEC® MP3 solid phase extraction (SPE) columns were purchased from Agilent Technologies, Inc. (Santa Clara, CA). Medical grade nitrogen was purchased from National Welders Supply Company (Richmond, VI). Drug-free expired whole blood was obtained from Transfusion Medicine Laboratory at Virginia Commonwealth University Health System. The blood was certified drug free by screening for alkaline extractable drugs by GC/MS and UPLC/MS/MS prior to use.

Sample preparation

Pre-extraction preparation was unnecessary for the whole blood and vitreous humor specimens. Bile, gastric contents and urine were diluted 1:10 with DI water, mixed using a vortex mixer and allowed to stand for 1 h. Two-gram aliquots of brain and liver tissue were diluted with 6.0 g of DI water and homogenized using an IKA®-Labortechnik Ultra-Turrax T25 homogenizer (Wilmington, NC). Samples that were determined to have concentrations that exceeded upper limit of the calibration were diluted to bring their concentrations within the linear range of the assay.

Sample analysis

Sample extraction and instrumental analysis were performed as previously described (10). In brief, 5 ng of fentanyl-d5, acetyl fentanyl-13C6 and acetyl norfentanyl-13C6 were added to 1.0 mL or 1.0 g aliquots of calibrators, quality control (QC) specimens or test specimens followed by the addition of 1 mL of pH 6.0 phosphate buffer. Samples were mixed using a vortex mixer for 30 seconds and centrifuged for 5 min. SPEC MP3 SPE columns were conditioned with 0.4 mL of methanol followed by 0.4 mL of 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6). The samples were added to the columns and aspirated, followed by 0.4 mL of DI water and 0.4 mL of 100 mM acetic acid. Columns were then dried under vacuum. The fentanyl derivatives, their metabolites and ISTDs were eluted with 1 mL of 78:20:2 dichloromethane/isopropanol/ammonia (v:v:v). The eluted extracts were evaporated under nitrogen and reconstituted in 100 µL of mobile phase A for UPLC/MS/MS analysis.

Apparatus

The UPLC/MS/MS analysis of butyryl fentanyl, acetyl fentanyl and acetyl norfentanyl was performed on a Waters Xevo TQD LC/MS mass spectrometer attached to a ACQUITY UPLC® System controlled by MassLynx software (Milford, MA). Chromatographic separation (Figure (Figure3)3) was performed on an Allure Biphenyl 5 µm 100 × 2.5 mm column (Restek, Bellefonte, Pennsylvania). The column was kept at 40°C and 5 µL of sample was injected. The mobile phase consisted of A: DI water and 10 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid and B: methanol. The following gradient was used: 0.00–1.5 min at 95% A and 5% B, 1.5–3 min at 60% A and 40% B, 3–3.5 min at 100% B and then return to 95% A and 5% B at 3.6 min. The flow rate was 0.6 mL/min. The separation of the fentanyl analytes and their ISTDs are presented in Figure Figure3.3. The source temperature was set at 150ºC with a capillary voltage of 3.00 kV. The desolvation temperature was set at 600ºC with a gas flow rate of 650 L/h. The cone flow rate was set at 100 L/h. The acquisition mode used was multiple reaction monitoring. The retention times (min), cone voltage (V), transition ions (m/z) and corresponding collection energies (eV) for all the compounds can be found in Table TableI.I. The total run time for the analytical method was 4.0 min.

Table I.

Fentanyl analogsa

| Designer drug | RT (min) | Cone (V) | Trans ions (m/z) | CE (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Butyryl fentanyl | 2.95 | 50 | 351 > 105 | 36 |

| 351 > 188 | 24 | |||

| Fentanyl-d5 | 2.86 | 50 | 342 > 105 | 36 |

| 342 > 188 | 24 | |||

| Acetyl fentanyl | 2.79 | 48 | 323 > 105 | 35 |

| 323 > 188 | 23 | |||

| Acetyl fentanyl-13C6 | 2.79 | 48 | 329 > 105 | 35 |

| 329 > 188 | 23 | |||

| Acetyl norfentanyl | 1.96 | 32 | 219 > 85 | 17 |

| 219 > 56 | 25 | |||

| Acetyl norfentanyl-13C6 | 1.95 | 32 | 225 > 84 | 17 |

| 225 > 56 | 25 |

aRetention times (RT), cone voltages (V), transition ions (m/z) and collision energies (CE).

Method validation

The method validation was performed as previously described (10). Method validation studies included selectivity, specificity, linearity, limit of detection, limit of quantitation, accuracy, precision, ion suppression/enhancement, matrix effects, recovery, stability and dilution integrity. Linearity of the assay was verified from seven-point calibration curves prepared in certified in-house drug-free whole blood. Butyryl and other fentanyl analyte calibrators prepared with the following concentrations: 1, 2, 5, 10, 25, 50 and 100 ng/mL with the lower limit of quantitation administratively defined to be 1 ng/mL. The linear regression correlation coefficients (r2) for the all the calibration curves ranged from 0.9982 to 0.9999. The QC samples were within ±20% of the target value and had responses at least 10 times greater than the signal to noise ratio of drug-free whole blood. The within-run and between-run precision ranged from 2% to 14% CV.

Results

The toxicology findings for both deaths are presented in Table TableII.II. In the first case, butyryl fentanyl was the only drug detected with concentrations of 99 ng/mL in peripheral blood, 220 ng/mL in heart blood, 32 ng/mL in vitreous humor, 590 ng/mL in gastric contents, 93 ng/g in brain, 41 ng/g in liver, 260 ng/mL in bile and 64 ng/mL in urine. In the first case, based on case history, autopsy findings and the toxicology findings, the medical examiner determined the cause of death was butyryl fentanyl intoxication and the manner of death was accident.

Table II.

Tissue distributions of butyryl fentanyl, acetyl fentanyl and acetyl norfentanyl (concentrations shown in units of ng/mL or ng/g, except for ethanol)a

| Case | Drug | PB | HB | Vitreous | Gastric | Brain | Liver | Bile | Urine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Butyryl fentanyl | 99 | 220 | 32 | 590 | 93 | 41 | 260 | 64 |

| 2 | Butyryl fentanyl | 3.7 | 9.2 | 9.8 | 4,000 | 63 | 39 | 49 | 2 |

| Acetyl fentanyl | 21 | 95 | 68 | 28,000 | 200 | 160 | 330 | 8 | |

| Acetyl norfentanyl | <1 | 1.2 | <1 | 8.9 | <4 | <4 | 4 | <1 | |

| Alprazolam | 40 | ||||||||

| Ethanol | 0.11 (g/dL) | 0.12 (g/dL) |

aPB, peripheral blood; HB, heart blood.

In the second case, butyryl fentanyl concentrations were 3.7 ng/mL in peripheral blood, 9.2 ng/mL in heart blood, 9.8 ng/mL in vitreous humor, 4,000 ng/mL in gastric contents, 63 ng/g in brain, 39 ng/g in liver, 49 ng/mL in bile and 2 ng/mL in urine. The acetyl fentanyl concentrations were 21 ng/mL in peripheral blood, 95 ng/mL in heart blood, 68 ng/mL in vitreous humor, 28,000 ng/mL in gastric contents, 200 ng/g in brain, 160 ng/g in liver, 330 ng/mL in bile and 8 ng/mL in urine. In addition, the alprazolam concentration was 40 ng/mL and the ethanol concentration was 0.11 g/dL, both measured in peripheral blood. In the second case, based on case history, autopsy findings and the toxicology findings, the medical examiner determined the cause of death was intoxication by the combined effects of butyryl fentanyl, acetyl fentanyl, alprazolam and ethanol, and the manner of death was accident.

Discussion

The presented cases were unusual in that the case histories and death scenes provided no indication that drugs associated with intravenous narcotism such as butyryl fentanyl or acetyl fentanyl would be detected. The presence of fentanyl analogs was indicated by the presumptive positive fentanyl blood immunoassay screens (despite negative fentanyl findings), which suggests both butyryl fentanyl and/or acetyl fentanyl have some degree of cross-activity with the fentanyl immunoassay. Both decedents had no evidence of intravenous drug use, as evidenced by the lack of old or fresh injection sites on their bodies. There was no evidence of illicit or intravenous drug use (needles, syringes, spoons, powders or baggies) at the scene nor any history of heroin abuse. Although both decedents had a history of prescription drug abuse, their case histories were not at all consistent with the previous reports of fentanyl or fentanyl analog deaths, which have had case histories and autopsy findings consistent with intravenous narcotism (4–10).

At the time the presented cases were analyzed, there were no published fatalities involving butyryl fentanyl. However, in a report from Sweden of four patients that survived butyryl fentanyl intoxications, analysis of two serums yielded butyryl fentanyl concentrations of 0.6 and 0.9 ng/mL (11). Testing of urine from three patients yielded butyryl fentanyl concentrations ranging from 2 to 65 ng/mL (11). In the first case, the peripheral blood butyryl fentanyl concentration of 99 ng/mL was 100 times greater than that of the highest serum value reported among the Swedish surviving patients. While anecdotal, this observation supports the medical examiner's conclusion of a fatal butyryl intoxication in the first case. Recently, there has been a single case report of a butyryl fentanyl fatality with reported butyryl fentanyl concentrations of 58 ng/mL in peripheral blood, 97 ng/mL in heart blood, 320 ng/g in liver, 40 ng/mL in vitreous humor, 170 mg total in gastric contents and 670 ng/mL in urine, findings similar to what was detected in the first case (21).

In both of our cases, it is possible that the victims ingested the substances orally since they both had significant concentrations of butyryl fentanyl in their gastric contents. However, since total gastric is not collected or submitted, the estimated amount of ingested drug could not be measured. In both cases, no evidence of butyryl fentanyl or illicit drug use was found at the death scenes so it is unclear exactly how (nasally, orally or sublingually) the butyryl fentanyl was administered. In both cases, the deaths appear to occur rapidly after drug administration as indicated by high concentrations of the drug in blood, gastric, brain and liver with low concentrations in urine. Also, the decedent in the first case was found unresponsive within 10 min after being seen entering bathroom.

At the time the autopsy and toxicology testing were completed on these cases, there were no published reports of fatal butyryl fentanyl intoxications. Therefore, the assertions in this report that butyryl fentanyl caused and/or contributed to the death in these cases were based on the case histories, autopsy results and toxicology results and the likely pharmacological similarity of butyryl fentanyl to fentanyl and acetyl fentanyl.

Conclusion

Butyryl fentanyl is a potent µ-opioid receptor agonist and CNS depressant that has been shown to produce clinical symptoms of respiratory depression and could likely lead to life-threatening respiratory depression. Based on case histories, circumstances, autopsy findings and toxicology results, both of these cases were determined to be accidental overdoses involving the new designer fentanyl analog, butyryl fentanyl.

Funding

This project was supported in part by the National Institute on Health (NIH) grant P30DA033934.

References

Articles from Journal of Analytical Toxicology are provided here courtesy of Oxford University Press

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1093/jat/bkw048

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://academic.oup.com/jat/article-pdf/40/8/703/7374026/bkw048.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

Fentanyl and its derivatives: Pain-killers or man-killers?

Heliyon, 10(8):e28795, 28 Mar 2024

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 38644874 | PMCID: PMC11031787

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Fatal cases involving new psychoactive substances and trends in analytical techniques.

Front Toxicol, 4:1033733, 25 Oct 2022

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 36387045 | PMCID: PMC9640761

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Blood concentrations of new synthetic opioids.

Int J Legal Med, 136(1):107-122, 22 Oct 2021

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 34676457

Review

Alternative matrices in forensic toxicology: a critical review.

Forensic Toxicol, 40(1):1-18, 19 Aug 2021

Cited by: 15 articles | PMID: 36454488 | PMCID: PMC9715501

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Designer drugs: mechanism of action and adverse effects.

Arch Toxicol, 94(4):1085-1133, 06 Apr 2020

Cited by: 82 articles | PMID: 32249347 | PMCID: PMC7225206

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (31) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

An Acute Butyr-Fentanyl Fatality: A Case Report with Postmortem Concentrations.

J Anal Toxicol, 40(2):162-166, 18 Dec 2015

Cited by: 28 articles | PMID: 26683128

Postmortem tissue distribution of acetyl fentanyl, fentanyl and their respective nor-metabolites analyzed by ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry.

Forensic Sci Int, 257:435-441, 26 Oct 2015

Cited by: 39 articles | PMID: 26583960 | PMCID: PMC4879818

An Acute Acetyl Fentanyl Fatality: A Case Report With Postmortem Concentrations.

J Anal Toxicol, 39(6):490-494, 26 Apr 2015

Cited by: 40 articles | PMID: 25917447

Three Cases of Fatal Acrylfentanyl Toxicity in the United States and a Review of Literature.

J Anal Toxicol, 42(1):e6-e11, 01 Jan 2018

Cited by: 14 articles | PMID: 29036502

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NIDA NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: P30 DA033934

National Institute on Health (NIH) (1)

Grant ID: P30DA033934