Abstract

Free full text

Irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease overlap syndrome: pieces of the puzzle are falling into place

Abstract

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a common gastrointestinal disorder involving the gut-brain axis, and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), a chronic relapsing inflammatory disorder, are both increasing in incidence and prevalence in Asia. Both have significant overlap in terms of symptoms, pathophysiology, and treatment, suggesting the possibility of IBS and IBD being a single disease entity albeit at opposite ends of the spectrum. We examined the similarities and differences in IBS and IBD, and offer new thoughts and approaches to the disease paradigm.

INTRODUCTION

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and IBD are two common chronic gastrointestinal (GI) disorders with unknown etiology and mechanisms. As our understanding improves, what were initially thought of as two separate and distinct GI disorders seem to have more in common, particularly at the extreme spectrum of both disorders–the prodromal phase of IBD and the late phase of IBS. This is augmented by the overlap of symptoms as well as the presence of colitis, raising the question of whether IBS and IBD are essentially on the same timeline–an evolution of the same disease.

DILEMMA OF IBS-IBD

IBS is characterized by a disordered gut-brain axis, but can develop following an enteric infection, and is associated with persistent immune activation that is a feature of IBD. Similarly, IBD, which encompasses CD and UC, is characterized by chronic relapsing inflammation and immune activation; however, recent evidence also points to altered gut microbiota and disturbed psychology, which are features of IBS, being important, both in the development and maintenance of disease.

The considerable overlap of symptoms and colitis raises the questions of whether IBS is a prodromal or mild subset of IBD, or whether IBD is pathologically related to the cause of IBS, or do they even represent the same pathophysiological spectrum of a disease. These claims are supported by the association and prevalence of IBS coexisting with IBD, especially in CD, with 39% pooled prevalence and OR of 4.89, even in remission.1

Indeed, there are a few studies correlating an increased risk of IBD among those with initial IBS symptoms.2,3,4

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF IBS AND IBD−BOTH ON THE RISE IN ASIA

The incidence of CD in the world ranges from 5.0 to 10.7 per 100,000 person-years, while the incidence of UC ranges from 6.3 to 24.3 per 100,000 person-years. The marked variations are due to geographical localities, with Asia tending to show the lowest incidence rate, as compared to predominantly UC in Europe, and CD in North America.5 Even in Asia, with its large geographical area, there is variation in the annual incidence rate from 0.1 to 6.3 per 100,000 population for UC and 0.04 to 5.0 per 100,000 population for CD.5

Gender differences were reportedly equal in large population-based studies, although some contested a higher male preponderance for IBD in Asia.5,6 The highest incidence ages of diagnosis were recorded in the second to fourth decades, therefore implicating the most productive age group, with socioeconomic impact in terms of hours off work and impaired productivity.

IBS in Asia shows a prevalence rate of 2.9% to 15.6%, with no predilection for the traditionally female gender.7,8,9 The prevalence rate is highly dependent on the utilization of Manning or Rome-based criteria, and to a lesser extent on the geographical distribution. Age distribution still involves younger individuals in their early 20's, comparable to Western studies.

However, for both IBS and IBD, the prevalence and annual incidence has shown a consistently increasing trend in Asia; which is in keeping with a worldwide trend.

Several studies from Asia spanning from 1986 to 2006 had shown increasing prevalence of IBD, ranging from 1.3 to 7.6 in the 1990's to 6.3 to 30.9 per 100,000 in the new millennium.10,11,12,13,14 In contrast, IBS is more variable, but the general trend has been on the increase, especially in affluent cities such as Singapore and Tokyo, while some reports indicate a common syndrome affecting both rural and urban populations.15,16,17,18

SIMILARITIES OF IBS AND IBD

Apart from similarities in symptoms and signs, there are several other pathophysiological similarities between IBD and IBS. These can be broadly categorized into four main components, including the brain-gut axis, genetic factors, microbiota, and the epithelial barrier, among others.

1. Brain-Gut Axis

It is a well-known fact that both IBD and more particularly IBS are predisposed to psychological comorbidities, with a cause and effect relationship. There is a bidirectional interaction between the central nervous system and the enteric nervous system, which in turn modulates the gut function.

There is evidence that depression and anxiety are more common in IBD patients, with the symptoms being more severe during active disease.2 A large Swiss IBD Cohort Study involving 2,007 patients showed that although anxiety is more prevalent compared to depression in IBD patients, depression has a more significant negative effect on IBD activity.19 Depression in itself predisposes to increased inflammation in response to stress, by releasing a higher amount of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin 6 (IL-6), compared to normal controls, as proven in human studies and animal models.20,21 Interestingly, a bidirectional effect has also been shown, in which the IBD course is also worse in patients who are depressed.22,23,24

In IBS, it has been reported that 50% to 90% of patients have or had at some point one or more common psychiatric condition, including major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, somatization disorder, or posttraumatic stress disorder.2,25 Our own limited data suggest that these psychological comorbidities in IBS are often nonserious.9 The limbic system is believed to be responsible by causing a surge in adrenocorticotrophic hormone and cortisol, and mediators such as IL-6 and IL-8 initiate a response in the enteric nervous system, resulting in symptoms of abdominal pain and diarrhea, which are typical of IBS.20,26 A more prominent activation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex area, which controls emotional and autonomic responses, has been shown to be increased in IBS patients, compared to control patients.27

2. Genetic Factors

The Tumor Necrosis Factor (Ligand)-Superfamily Member 15, also known as the TNF-SF15 gene, is known to be associated with CD and also primary biliary cirrhosis. The expression of this protein subsequently acts as an autocrine factor inducing apoptosis, and also inhibits endothelial cell proliferation, resulting in inflammation.

Several studies from the USA, Sweden, and more recently the UK have also noted the association of TNF-SF15 polymorphism with increased risk of IBS.28,29 This suggests a possible common pathway for both IBD and IBS through immune activation in both of these diseases.

Familial occurrence is common in both diseases, which highlights the possibility of shared genetic transmission. TNF-SF15 polymorphism may pave the way for identification of a precursor or trigger, whereas multi-gene analysis, such as the von Stein et al.30 seven gene model, may be utilized to differentiate between IBS and IBD.

3. Microbiota

Dysbiosis (abnormal gut microbiota) has been linked with several diseases that include IBD and IBS. A recent study evaluating a dysbiosis index algorithm detected dysbiosis in 70% of treatment-naïve IBD patients and 73% of IBS patients, in comparison with only 16% of healthy subjects.31

Alterations in gut microbiota have been observed in IBS patients,32,33 and are also seen in post-infectious IBS, which in turn is postulated to be a trigger for IBD.33,34,35,36 Fluorescent in-situ hybridization studies have detected increased bacterial presence in the mucus layer of IBD and IBS patients. Commensal organisms in IBD and IBS patients are also inherently different when compared to healthy subjects.34 Dysbiosis involving Faecalibacterium prausnitzii was noted to occur in a CD population in Europe, strengthening the argument for alterations of the intestinal microbiota as a cause of IBD.37,38

4. Impaired Epithelial Barrier

Increased gut permeability, which therefore increases susceptibility to injurious agents, has been suggested to precede clinical CD.39 Stress exacerbates IBD, and has been shown to cause an increase in activation of gut mast cells, which subsequently increases gut permeability.34,40

Similarly in IBS, elevation in miRNA-29a has been noted. This plays a role in down-regulating glutamine synthetase, which causes increased gut permeability,41 in a manner similar to IBD-related increases in permeability and subsequent injury.

Increased intestinal permeability due to changes at the cellular levels has been attributed to changes in transient receptor potential vanilloid receptor 1, protein zonulin 1, and a-catenin, and has indeed been implicated in both IBS and also IBD presenting with IBS symptoms.18,42,43

Bacterial gastroenteritis as opposed to viral gastroenteritis also predisposes to greater permeability disturbances, and is associated with increased postinfectious IBS.

This common endpoint of increased gut permeability is currently the subject of intense studies worldwide.

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN IBS AND IBD

Notable differences were also seen between IBD and IBS, although there are arguments that these could be considered similarities. These include the following:

1. Fecal Calprotectin

The advent of fecal calprotectin has revolutionized noninvasive testing in IBD. High calprotectin levels are almost always due to ongoing inflammation related to chronic IBD. Keohane et al.44 found that IBD in remission with associated IBS exhibited greater fecal calprotectin levels than IBD in remission alone. This suggests that despite IBD being in remission, occult inflammation continues in the presence of IBS. In contrast, IBS is likely to have normal to low levels of calprotectin unless it is associated with a low degree of inflammation, as in postinfectious IBS.45

It has been proposed that a level below 40 µg/g is an indicator of no inflammation, whereas a level above 100 µg/g indicates significant inflammation, suggesting IBD. However, at the in-between level of 40 to 100 µg/g, it is uncertain whether this indicates a low level of IBD or IBS, or pre-IBD IBS.46 In comparison to other biomarkers, including high sensitivity CRP, lactoferrin, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, nitric oxide, and intraepithelial lymphocytes, fecal calprotectin has helped to identify active IBD patients, but not such that it has proved to be a good positive or negative predictor, as evident by being normal in IBS.44,47,48 These other biomarkers, however, may be more useful as part of a diagnostic workup in combination with calprotectin.49

2. Degree of Inflammation

In IBD, mucosal inflammation is usually ongoing and slow to resolve, even in clinically asymptomatic patients. IBD in remission still exhibits a higher level of TNF-α and intraepithelial lymphocytes compared to IBS patients.50 In contrast, IBS patients tend to exhibit low grade, variable, or even absent mucosal inflammation.2

3. Symptoms versus Inflammation Mismatch

Inherently, IBD is an organic disease, as evidenced by mucosal inflammation, whereas IBS lies more in the spectrum of a functional disorder, with no evidence of organic disease. IBS symptoms are nonspecific, and may precede diagnosis of both IBS and IBD by many years. Lack of mucosal inflammation results in a mismatch compared to the severity of the reported symptoms.

In IBD, mucosal inflammation is characteristic, but the symptoms do not necessarily correlate with endoscopic findings.51

4. Visceral Hypersensitivity

The gut viscera are controlled by a complex, incompletely understood interaction between the enteric nervous system, the vagal and spinal primary afferents, and both small and large myelinated and unmyelinated fibers that control motility and peristalsis. The interaction of neuroimmune and intestinal epithelial cells may prove to be a protective barrier in health but has also been implicated as the likely cause of GI pathology. In addition, there are persistent increases in mast cells, vasoactive intestinal peptide, and substance P, among many other receptors, which again either maintains or is a causative agent of GI disease.

As proven by persistent pain despite minimal inflammation and the response to centrally-acting agents, visceral hypersensitivity is the likely explanation for the symptoms and brain responses in IBS.

However, in IBD, the hallmark of the disease is mucosal inflammatory change that correlates with disease severity, and is the target of healing treatment. Visceral hypersensitivity is more apparent in IBD patients in remission, further strengthening the argument for IBS as a pre-IBD state.

IBS-IBD DISEASE PARADIGMS

There is growing evidence that IBS or IBS-like symptoms are a prodrome before the formal diagnosis of IBD. It has also been documented that IBS symptoms occur in IBD patients in remission, particularly in cases of CD.

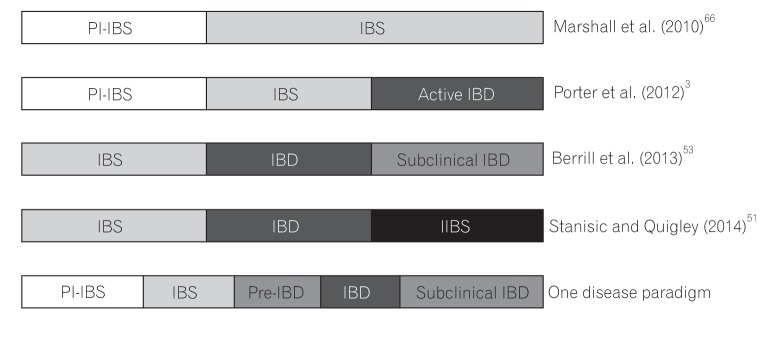

Over the years, several disease progression paradigms have been proposed (Fig. 1). Initially, after an episode of contaminated municipal water supply, it was proven that postinfectious IBS predates the formal diagnosis of IBS.52 In 2012, Porter et al.3 added to that work with the suggestion that post-infectious IBS is followed by IBS, and subsequently followed by active IBD. Berrill et al.53 suggested that IBS is an early part of a disease spectrum that subsequently leads to IBD, and progresses towards "subclinical IBD," in which case, mucosal healing might not be the endpoint in therapy. Stanisic and Quigley51 instead proposed "irritable IBD" as the unifying model of IBS symptoms in IBD in remission.

Our proposal that IBS and IBD comprise a single disease paradigm is not new, although variation exists as to what happens in-between the two conditions. Moreover, IBS is a disorder with a very broad spectrum, and immune activation has been found in only a fraction of cases. Thus, the association of IBS with IBD may be confined to this fraction of IBS. Indeed, further research is needed to support this idea.3,18,54,55

The initial or prodromal insult is enteric infection, resulting in postinfectious IBS, which is followed by a period of IBS-like symptoms without obvious colonic inflammation. We further propose an "early or pre-IBD" period at which there is a low level or grade of colonic inflammation occurring in IBS. This then leads to active IBD, followed by subclinical IBD with ongoing low-grade inflammation, although it is possible that irritable IBD occurs when the inflammation burns out.

This low-grade inflammation during the early pre-IBD period is suggested by studies showing that fecal calprotectin remains positive in one-third of IBS patients; this indicates that inflammation, along with further insults such as infections or stress, may inadvertently trigger IBD, followed by the extreme end of the spectrum, which is the proposed subclinical IBD (Fig. 1). Other studies showed that microscopic inflammation was found in up to 14.9% of cases in diarrheapredominant IBS, supporting the claim of low-level ongoing inflammation prior to the diagnosis of IBD.56 Indeed, patients with IBS are 15 times more likely to develop IBD compared to those with no IBS-like symptoms.3

The question is what may have caused the ongoing low-grade inflammation in the early or pre-IBD period? We believe that altered gut-brain axis and disturbed psychology associated with IBS can perpetuate and sustain the low-grade inflammation. Likewise, new triggers including new enteric infection in the form of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) or intestinal dysbiosis, that is often unsuspected in IBS or IBD, may have sustained the low-grade inflammation. Bloating is a common symptom present in both disorders, and SIBO is a cause of bloating that can be excluded easily through hydrogen breath testing.57,58

WHAT TO OFFER THESE PATIENTS?

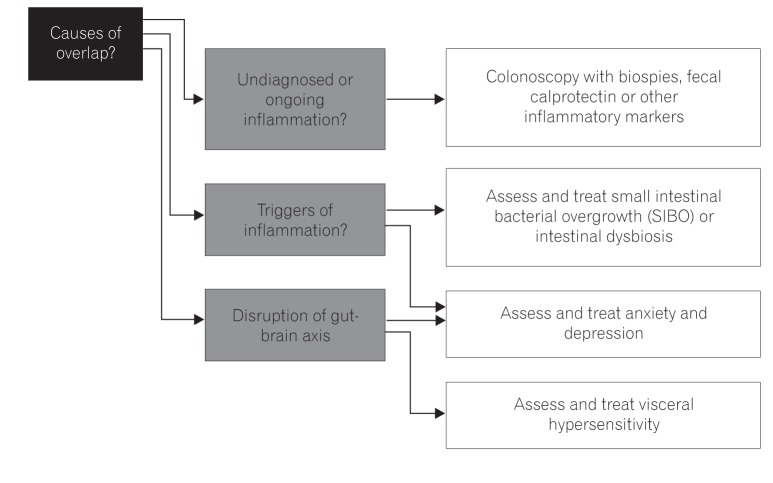

The main challenge has always been to make a definitive diagnosis, but overlap between IBS and IBD can pose a problem. A colonoscopy with mucosal histopathological studies and/or Rome questionnaires may not be adequate to separate the two. Management consideration is shown in Fig. 2.

With fecal calprotectin (or other stool markers, e.g., lactoferrin), it is potentially easier to distinguish between IBD, IBS, or the proposed early or pre-IBD condition with its low-grade inflammation. This can further be of use as a risk-stratifying method to ensure these patients are followed up, thereby preventing or controlling active IBD.

Regulation of the gut microbiota as a potential trigger of IBS and IBD is also important. This therefore necessitates testing for SIBO or intestinal dysbiosis, and future strategies including the use of prebiotics, probiotics, or synbiotics are needed.

Often neglected but proven is the bidirectional relationship of anxiety and depression or other altered psychology states in IBD or IBS. Therefore, it is essential to have a holistic approach and to address such concerns in not only cases of active disease but for those in remission as well.59,60,61,62

FUTURE RESEARCH

Current research into IBS-IBD similarities has so far only scratched the surface. Further gene studies including NOD2 and IBD1-5 among others should be conducted to complement current information gleaned from the TNF-SF15 information we currently have.

Emerging gut microbiota research should be able to influence the management of IBS and IBD with utilization of pre/probiotics and perhaps vaccination strategies.

Gut-brain axis studies involving hypnosis and psychotherapy are beginning to show promising results, prompting a more inclusive view and stressing the importance of a multidisciplinary approach. Several studies are currently underway to assess the effect of IBS drugs such as tricyclics, and IBD drugs such as mesalamine, when used interchangeably to treat the opposite disorders. In several studies completed so far, although the above drugs had no major impact in IBS patients, there were improvements in some subtypes of IBS, suggesting that these drugs may be useful in patients at a certain threshold or timeline in their evolution of the IBS-IBD paradigm.63,64,65

CONCLUSIONS

Previously disputed, the idea of IBS and IBD being intimately interlinked seems to be gathering pace, backed by a litany of evidence and research developments. The disease paradigm may have to be altered to consider both IBS and IBD as belonging on the same timeline, but with differing presentation and outlook, allowing a more comprehensive management plan.

Ultimately, further research and studies into these particular areas may inadvertently lead to prevention strategies for IBS, thereby negating the subsequent consequences of IBD.

Footnotes

Financial support: None.

Conflict of interest: None.

References

Articles from Intestinal Research are provided here courtesy of Korean Association for the Study of Intestinal Diseases

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.5217/ir.2016.14.4.297

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://www.irjournal.org/upload/pdf/ir-14-297.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

Sources of diagnostic delay for people with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis: Qualitative research study.

PLoS One, 19(6):e0301672, 10 Jun 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38857292

Recent Trends in Non-Invasive Methods of Diagnosis and Evaluation of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Short Review.

Int J Mol Sci, 25(4):2077, 08 Feb 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38396754 | PMCID: PMC10889152

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Early life adverse exposures in irritable bowel syndrome: new insights and opportunities.

Front Pediatr, 11:1241801, 05 Sep 2023

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 37732013 | PMCID: PMC10507713

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Association between body mass index and fecal calprotectin levels in children and adolescents with irritable bowel syndrome.

Medicine (Baltimore), 101(32):e29968, 01 Aug 2022

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 35960084 | PMCID: PMC9371505

Exploring the Gut Microbiome in Myasthenia Gravis.

Nutrients, 14(8):1647, 14 Apr 2022

Cited by: 18 articles | PMID: 35458209 | PMCID: PMC9027283

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (25) article citations

Other citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Comparison of geographic distributions of Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Inflammatory Bowel Disease fail to support common evolutionary roots: Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases are not related by evolution.

Med Hypotheses, 110:31-37, 02 Nov 2017

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 29317064

Review

Irritable bowel syndrome in inflammatory bowel disease. Synergy in alterations of the gut-brain axis?

Gastroenterol Hepatol, 45(1):66-76, 21 May 2021

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 34023477

Review

The functional-organic dichotomy: postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease-irritable bowel syndrome.

Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 7(1):48-53, 03 Sep 2008

Cited by: 75 articles | PMID: 18848909

Review

Is irritable bowel syndrome a low-grade inflammatory bowel disease?

Gastroenterol Clin North Am, 34(2):235-45, vi-vii, 01 Jun 2005

Cited by: 116 articles | PMID: 15862932

Review

3

3