Abstract

Free full text

Trends in Timing of Pregnancy Awareness Among US Women

Abstract

Objectives

Early pregnancy detection is important for improving pregnancy outcomes as the first trimester is a critical window of fetal development; however, there has been no description of trends in timing of pregnancy awareness among US women.

Methods

We examined data from the 1995, 2002, 2006–2010 and 2011–2013 National Survey of Family Growth on self-reported timing of pregnancy awareness among women aged 15–44 years who reported at least one pregnancy in the 4 or 5 years prior to interview that did not result in induced abortion or adoption (n = 17, 406). We examined the associations between maternal characteristics and late pregnancy awareness (≥7 weeks’ gestation) using adjusted prevalence ratios from logistic regression models. Gestational age at time of pregnancy awareness (continuous) was regressed over year of pregnancy conception (1990–2012) in a linear model.

Results

Among all pregnancies reported, gestational age at time of pregnancy awareness was 5.5 weeks (standard error = 0.04) and the prevalence of late pregnancy awareness was 23 % (standard error = 1 %). Late pregnancy awareness decreased with maternal age, was more prevalent among non-Hispanic black and Hispanic women compared to non-Hispanic white women, and for unintended pregnancies versus those that were intended (p < 0.01). Mean time of pregnancy awareness did not change linearly over a 23-year time period after adjustment for maternal age at the time of conception (p < 0.16).

Conclusions for Practice

On average, timing of pregnancy awareness did not change linearly during 1990–2012 among US women and occurs later among certain groups of women who are at higher risk of adverse birth outcomes.

Introduction

Early pregnancy detection and first trimester prenatal care increase the chances of having a healthy pregnancy and baby (Ayoola et al. 2009).1 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and other organizations call for folic acid supplementation and cessation of alcohol, tobacco, recreational drugs and nonessential medication use prior to or as early in pregnancy as possible for the prevention of neural tube and other birth defects which develop during critical periods in early pregnancy (ACOG Committee Opinion number 2005; Floyd et al. 2013).2 Pregnancy awareness later in gestation has previously been observed among women with characteristics associated with continuing high risk behaviors into early pregnancy, such as young maternal age, lower education and socioeconomic status, and pregnancy unintendedness, and with later initiation of prenatal care (Dott et al. 2010; Ayoola 2015; Ayoola et al. 2010; Swanson et al. 2014; Kost and Lindberg 2015). The combination of later pregnancy awareness and initiation of prenatal care and continuation of high risk behaviors into pregnancy can lead to higher risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, including birth defects, preterm delivery, low birthweight, and neonatal intensive care admissions (Ayoola et al. 2009 Ayoola et al. 2010; Than et al. 2005).

In addition, while pregnancy awareness in early gestation is important for the curtailment of risky behaviors, as women become aware of their pregnancies earlier in gestation this also increases the potential for earlier miscarriage detection and reporting. This could influence time trend analyses of miscarriage rates, which may be driven by changes in awareness and reporting versus a real increase in miscarriage over time (Lang and Nuevo-Chiquero 2012). However, there has been no examination of trends in timing of pregnancy awareness among US women to date. Therefore, using a national sample of US women from the National Survey of Family Growth, we estimated associations between maternal characteristics and gestational age at time of pregnancy awareness and how these associations may have changed over time. In addition, we sought to examine overall trends in gestational age at time of pregnancy awareness in US women over the last two decades.

Methods

Study Participants

We analyzed data on women from the 1995, 2002, 2006–2010 and 2011–2013 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG). The NSFG, conducted by the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics and funded by multiple Federal agencies, is a nationally representative survey of the non-institutionalized civilian US population ages 15–44 years and uses a complex, multistage, probability design to select participants.3 Female response rates for the 1995, 2002, 2006–2010 and 2011–2013 NSFG were 79, 80, 78 and 73 %, respectively. This secondary analysis of NSFG data was exempt from National Center for Health Statistics’ Ethics Review Board review.

Study Variables

Details on previous pregnancies were captured in the NSFG Pregnancy Interval File, which contains detailed information on all reported pregnancies for each female participant (see footnote 3). This file included 21,332 pregnancies from 10,847 women in the 1995 NSFG; 13,593 pregnancies from 7,643 women in the 2002 NSFG; 20,492 pregnancies from 12,279 women in the 2006–2010 NSFG; and 9,543 pregnancies from 5,601 women in the 2011–2013 NSFG. Although details such as pregnancy duration and outcome were asked about all pregnancies occurring up to the time of interview, only completed pregnancies reported in the 4 or 5 years prior to interview were included in our analysis. This included multiple pregnancies to the same woman if she reported more than one in the past 4 or 5 years. More on this is described below and in the description regarding a sensitivity analysis.

Starting with the 1995 NSFG, timing of pregnancy awareness was ascertained by asking “how many weeks pregnant were you when you learned that you were pregnant?” for each completed pregnancy that occurred in the 4 (1995 NSFG) or 5 (2002, 2006–2010–2011–2013 NSFG) years prior to interview and that did not end in induced abortion or with a livebirth being placed for adoption. This is a standard restriction used by the NSFG for this question. After excluding conception years with fewer than 100 pregnancies reported due to unstable estimates (1995, n = 22; 2013, n = 10) and pregnancies with missing information on the timing of pregnancy awareness (n = 37), our analysis included a 23-year span of time including 17,406 pregnancies for analysis (see Table 1 for the breakdown of number of pregnancies and respondents by survey period).

Table 1

Maternal and pregnancy characteristics of completed pregnancies reported: National Survey of Family Growth, 1995, 2002, 2006–2010, 2011–2013

| Respondents, n Pregnanciesb, n | Pooled (1990–1994, 1996–2012)a 11928 17406 % (SE) | 1995 (1990–1994) 3073 4083 % (SE) | 2002 (1996–2002) 2707 4052 % (SE) | 2006–2010 (2000–2010) 4216 6350 % (SE) | 2011–2013 (2005–2012) 1932 2921 % (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at pregnancy conceptionc | |||||

15–19 years 15–19 years | 13.3 (0.47) | 14.3 (0.7) | 13.5 (0.9) | 13.7 (0.8) | 12.1 (1.1) |

20–24 years 20–24 years | 25.1 (0.57) | 26.5 (1.0) | 25.5 (1.2) | 24.6 (1.0) | 24.4 (1.3) |

25–29 years 25–29 years | 27.8 (0.59) | 28.8 (0.9) | 25.9 (0.9) | 26.8 (1.0) | 30.3 (1.6) |

30–34 years 30–34 years | 21.8 (0.63) | 20.6 (0.8) | 22.2 (1.1) | 21.9 (1.1) | 22.1 (1.7) |

35–44 years 35–44 years | 11.9 (0.52) | 10.0 (0.6) | 12.8 (1.3) | 13.0 (0.9) | 11.3 (0.9) |

| Race and ethnicity | |||||

Hispanic or Latino Hispanic or Latino | 19.1 (0.97) | 15.2 (1.1) | 18.7 (1.3) | 20.4 (2.4) | 21.2 (2.2) |

Non-Hispanic white Non-Hispanic white | 59.7 (1.06) | 65.9 (1.4) | 61.5 (1.6) | 56.4 (2.4) | 56.8 (2.6) |

Non-Hispanic black Non-Hispanic black | 15.1 (0.73) | 14.3 (0.9) | 14.3 (1.1) | 16.6 (1.5) | 15.1 (1.9) |

Non-Hispanic other Non-Hispanic other | 6.0 (0.60) | 4.6 (0.6) | 5.6 (0.6) | 6.6 (1.2) | 6.9 (1.8) |

| Educational attainment (at time of interview) | |||||

No high school diploma or GED No high school diploma or GED | 19.0 (0.70) | 19.0 (0.9) | 18.9 (1.3) | 22.1 (1.4) | 15.8 (1.6) |

High school diploma or GED High school diploma or GED | 31.0 (0.73) | 40.6 (1.1) | 31.8 (1.4) | 27.0 (1.1) | 27.5 (1.9) |

Some college, no bachelor’s degree Some college, no bachelor’s degree | 25.6 (0.73) | 21.7 (0.9) | 25.5 (1.2) | 24.7 (1.2) | 29.6 (2.0) |

Bachelor’s degree Bachelor’s degree | 16.7 (0.59) | 15.1 (0.8) | 17.0 (1.1) | 18.0 (1.1) | 16.0 (1.4) |

Master’s degree or higher Master’s degree or higher | 7.7 (0.62) | 3.6 (0.4) | 6.8 (1.0) | 8.2 (0.8) | 11.2 (1.9) |

| Percentage of poverty level (at time of interview) | |||||

Less than 100 % Less than 100 % | 27.2 (0.73) | 22.6 (1.1) | 24.6 (1.3) | 27.1 (1.4) | 33.3 (1.9) |

100–299 % 100–299 % | 41.0 (0.79) | 41.4 (1.1) | 40.3 (1.4) | 45.0 (1.4) | 37.2 (2.0) |

300–399 % 300–399 % | 14.0 (0.59) | 11.8 (0.8) | 17.7 (1.2) | 15.7 (1.2) | 10.1 (1.3) |

400 % or more 400 % or more | 17.8 (0.68) | 24.2 (1.1) | 17.4 (0.9) | 12.2 (0.9) | 19.5 (2.0) |

| Marital status at pregnancy conception | |||||

Married Married | 56.6 (0.91) | 64.2 (1.1) | 57.8 (1.6) | 54.2 (1.6) | 52.4 (2.4) |

Widowed, divorced, separated Widowed, divorced, separated | 8.0 (0.45) | 6.8 (0.5) | 9.0 (1.2) | 7.3 (0.6) | 8.4 (1.0) |

Never married Never married | 35.4 (0.82) | 29.0 (1.0) | 33.3 (1.5) | 38.5 (1.5) | 39.2 (2.1) |

| Smoked during pregnancyc | |||||

Yes Yes | 15.8 (0.69) | 52.5 (1.9) | 14.4 (1.2) | 13.2 (0.9) | 10.9 (1.4) |

No No | 84.2 (0.70) | 47.5 (1.9) | 85.6 (1.3) | 86.7 (0.9) | 89.0 (1.4) |

| Intendedness of pregnancy at conceptionc | |||||

Intended Intended | 64.4 (0.67) | 67.9 (0.8) | 64.5 (1.2) | 61.7 (1.3) | 64.7 (1.6) |

Unwanted Unwanted | 22.2 (0.49) | 22.3 (0.7) | 20.9 (0.9) | 23.5 (1.0) | 22.2 (1.2) |

Mistimed Mistimed | 13.4 (0.46) | 9.8 (0.5) | 14.6 (0.9) | 14.8 (0.8) | 13.1 (1.2) |

| Gravidity | |||||

First pregnancy First pregnancy | 29.0 (0.46) | 29.6 (0.9) | 28.6 (1.0) | 28.7 (0.8) | 29.2 (0.9) |

Not first pregnancy Not first pregnancy | 71.1 (0.46) | 70.4 (0.9) | 71.5 (1.0) | 71.3 (0.8) | 70.8 (0.9) |

| Pregnancy outcome | |||||

Livebirth Livebirth | 78.4 (0.53) | 81.8 (0.8) | 78.2 (1.0) | 78.0 (0.9) | 76.4 (1.3) |

Miscarriage/stillbirth Miscarriage/stillbirth | 20.1 (0.51) | 16.6 (0.8) | 20.2 (1.0) | 20.5 (0.8) | 21.9 (1.2) |

Ectopic pregnancy Ectopic pregnancy | 1.6 (0.16) | 1.6 (0.2) | 1.5 (0.3) | 1.5 (0.2) | 1.7 (0.4) |

| Gestational age of pregnancy | |||||

Less than 12 weeks Less than 12 weeks | 15.5 (0.50) | 12.5 (0.7) | 15.0 (0.9) | 15.6 (0.8) | 18.1 (1.4) |

12–19 weeks 12–19 weeks | 4.7 (0.23) | 4.4 (0.4) | 4.8 (0.5) | 5.1 (0.4) | 4.2 (0.5) |

20–29 weeks 20–29 weeks | 2.0 (0.19) | 1.6 (0.2) | 2.4 (0.3) | 2.0 (0.3) | 2.0 (0.6) |

30–36 weeks 30–36 weeks | 8.7 (0.30) | 7.6 (0.4) | 9.1 (0.6) | 8.5 (0.5) | 9.2 (0.7) |

37+ weeks 37+ weeks | 69.1 (0.58) | 74.0 (0.9) | 68.6 (1.1) | 68.8 (0.9) | 66.5 (1.6) |

| Prenatal care initiationc | |||||

Less than 12 weeks Less than 12 weeks | 75.0 (0.52) | 73.0 (0.8) | 78.8 (1.0) | 74.1 (0.9) | 73.4 (1.2) |

12+ weeks 12+ weeks | 15.4 (0.40) | 17.7 (0.8) | 13.2 (0.8) | 16.2 (0.7) | 15.1 (0.9) |

No care No care | 9.7 (0.38) | 9.3 (0.6) | 8.1 (0.6) | 9.7 (0.6) | 11.5 (1.1) |

GED general education development

Several factors have been identified from previous studies to be associated with timing of pregnancy awareness, including the following ascertained by the NSFG: race/ethnicity, age (at the time of conception), marital status (at the time of conception), pregnancy intendedness, smoking during pregnancy, gravidity (at the time of conception), pregnancy outcome and duration, timing of prenatal care initiation, poverty-income ratio (measured at the time of interview), and educational attainment (measured at the time of interview) (Dott et al. 2010; Ayoola 2015; Ayoola et al. 2010; Swanson et al. 2014; Kost and Lindberg 2015). We therefore included these variables in our analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Mean gestational age at time of pregnancy awareness was calculated for each maternal and pregnancy characteristic included in our analysis. To assess potential differences over time, we calculated mean gestational age using all the data combined (pooled analysis) and for each survey period separately. Differences in mean gestational age among levels of each characteristic were assessed with p values from Satterthwaite adjusted general linear F tests from unadjusted linear regression models using data pooled across survey periods. Similarly, differences among survey periods within each characteristic’s category level were assessed with Satterthwaite adjusted p values, using data restricted to the respective category level.

Gestational age at time of pregnancy awareness was then dichotomized into “early awareness” (0–6 weeks) and “late awareness” (≥7 weeks) similar to previous analyses using self-reported maternal data (Ayoola et al. 2009; Ayoola 2015; Kost and Lindberg 2015). Logistic regression models were used to estimate the predicted prevalence of late pregnancy awareness by level of each characteristic.

The association of late pregnancy awareness with each demographic characteristic was estimated with prevalence ratios (PR) using adjusted predicted prevalence estimates. Models controlled for possible confounding by maternal age, race/ethnicity and pregnancy intendedness. Except for models where age, race/ethnicity and intendedness were the independent variables, all other models were adjusted for these three characteristics. For models where these characteristics were the independent variables, we adjusted for the other two characteristics (e.g., model for age was adjusted for race/ethnicity and intendedness). Smoking during pregnancy, gestational age of pregnancy, pregnancy outcome and week of prenatal care initiation are potentially consequences of the time of pregnancy awareness and therefore were not included in these models of late pregnancy awareness. Usually the category with the lowest prevalence of late pregnancy awareness was the referent group for each characteristic. Cross-product terms between characteristic and survey period were added to the adjusted model to assess statistical interaction. If the cross-product term p value was ≤0.05, indicating that there were significant differences by survey period, then the results were presented only by survey period; otherwise, results using pooled data were presented.

Linear regression was used to assess trend in timing of pregnancy awareness with gestational age at time of pregnancy awareness as the dependent variable and calendar year of pregnancy conception as the continuous linear independent variable. This model was only adjusted for maternal age as retrospective time trend data from the NSFG are naturally biased by maternal age (i.e. mean, minimum and maximum age during pregnancy calendar year increases over time up to the year of interview). Analyses were performed using the pooled data.

Sensitivity Analysis

We conducted a sensitivity analysis by restricting the dataset to the most recent pregnancy (68 % of completed pregnancies in the last 5 years) to determine the joint effect of (1) including more than one pregnancy per woman in the analysis and (2) misclassification of timing of pregnancy awareness for pregnancies with a longer recall period. We then recreated our table of mean gestational age by maternal and pregnancy characteristics using the restricted dataset and compared the results with the original table in a supplemental analysis. None of the mean gestational ages differed by more than 0.7 weeks and the differences we did observe were not systematically higher or lower.

We also investigated the effect of not statistically accounting for the clustering of pregnancies by woman by rerunning the linear regressions for time trend analyses using subject identification number in place of primary sampling unit in our complex survey analysis. This resulted in the same point estimates but slightly narrower confidence intervals (data not shown). All analyses were conducted with SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) and SAS-callable SUDAAN 11.0 (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina).

Results

Maternal and pregnancy characteristics of completed pregnancies included in our analysis are shown in Table 1. Overall, the mean gestational age at time of pregnancy awareness was 5.5 weeks (standard error = 0.04, Table 2). Mean gestational age at time of pregnancy awareness varied by NSFG survey period (p < 0.001), with that reported in the 2002 survey significantly lower than the other survey periods (all p < 0.05). No other pairwise differences between survey periods were significant. See supplemental figure for complete distribution of gestational age at time of pregnancy awareness by survey period.

Table 2

Mean gestational age (in weeks) of pregnancy awareness by maternal and pregnancy characteristics: National Survey of Family Growth, 1995, 2002, 2006–2010, 2011–2013

| Pooled (1990–1994–1996–2012)a | 1995 (1990–1994) | 2002 (1996–2002) | 2006–2010 (2000–2010) | 2011–2013 (2005–2012) | Pd | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondents, n | 11,928

| 3073 | 2707 | 4216 | 1932 | ||

| Pregnanciesb, n | 17,406

| 4083 | 4052 | 6350 | 2921 | ||

| Mean (SE) | Pc | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | ||

| All | 5.5 (0.04) | 5.6 (0.1) | 5.2 (0.1) | 5.5 (0.1) | 5.7 (0.1) | <0.001 | |

| Age at pregnancy conception | <0.001 | ||||||

15–19 years 15–19 years | 6.6 (0.14) | 6.7 (0.2) | 6.0 (0.2) | 6.5 (0.2) | 7.4 (0.4) | 0.01 | |

20–24 years 20–24 years | 5.7 (0.08) | 5.9 (0.2) | 5.4 (0.2) | 5.6 (0.1) | 5.9 (0.2) | 0.10 | |

25–29 years 25–29 years | 5.3 (0.06) | 5.2 (0.1) | 5.1 (0.1) | 5.3 (0.1) | 5.5 (0.2) | 0.09 | |

30–34 years 30–34 years | 5.0 (0.09) | 5.0 (0.1) | 4.7 (0.1) | 5.1 (0.2) | 5.0 (0.2) | 0.43 | |

35–44 years 35–44 years | 5.0 (0.11) | 4.9 (0.2) | 4.7 (0.2) | 5.2 (0.2) | 5.1 (0.3) | 0.45 | |

| Race and ethnicity | 0.01 | ||||||

Hispanic or Latina Hispanic or Latina | 5.7 (0.10) | 5.9 (0.1) | 5.4 (0.1) | 5.6 (0.1) | 6.2 (0.3) | 0.02 | |

Non-Hispanic white Non-Hispanic white | 5.2 (0.05) | 5.3 (0.1) | 5.0 (0.1) | 5.2 (0.1) | 5.3 (0.1) | 0.11 | |

Non-Hispanic black Non-Hispanic black | 6.2 (0.10) | 6.6 (0.2) | 5.7 (0.2) | 6.5 (0.2) | 6.1 (0.2) | 0.01 | |

Non-Hispanic other Non-Hispanic other | 5.8 (0.21) | 5.7 (0.4) | 5.6 (0.3) | 5.5 (0.3) | 6.3 (0.4) | 0.28 | |

| Educational attainment (at time of interview) | <0.001 | ||||||

No high school diploma or GED No high school diploma or GED | 5.9 (0.10) | 6.5 (0.2) | 5.4 (0.2) | 5.8 (0.2) | 6.0 (0.3) | 0.01 | |

High school diploma or GED High school diploma or GED | 5.7 (0.07) | 5.8 (0.1) | 5.4 (0.1) | 5.7 (0.1) | 6.2 (0.2) | <0.01 | |

Some college, no bachelor’s degree Some college, no bachelor’s degree | 5.5 (0.08) | 5.2 (0.1) | 5.3 (0.1) | 5.6 (0.2) | 5.7 (0.2) | 0.03 | |

Bachelor’s degree Bachelor’s degree | 4.7 (0.08) | 4.7 (0.1) | 4.7 (0.1) | 4.7 (0.1) | 4.9 (0.2) | 0.69 | |

Master’s degree or higher Master’s degree or higher | 5.0 (0.13) | 4.5 (0.2) | 4.7 (0.2) | 5.3 (0.2) | 5.0 (0.3) | 0.21 | |

| Percentage of poverty level (at time of interview) | <0.001 | ||||||

Less than 100 % Less than 100 % | 6.1 (0.08) | 6.6 (0.2) | 5.4 (0.1) | 6.0 (0.1) | 6.4 (0.2) | <0.001 | |

100 %–299 % 100 %–299 % | 5.5 (0.06) | 5.5 (0.1) | 5.4 (0.1) | 5.4 (0.1) | 5.7 (0.1) | 0.44 | |

300 %–399 % 300 %–399 % | 5.1 (0.11) | 5.1 (0.3) | 4.7 (0.1) | 5.4 (0.2) | 5.3 (0.3) | 0.05 | |

400 % or more 400 % or more | 4.8 (0.08) | 4.8 (0.1) | 4.8 (0.1) | 4.7 (0.2) | 4.8 (0.2) | 0.97 | |

| Marital status at pregnancy conception | <0.001 | ||||||

Married Married | 5.0 (0.05) | 5.0 (0.1) | 4.8 (0.1) | 5.1 (0.1) | 5.1 (0.1) | 0.04 | |

Widowed, divorced, separated Widowed, divorced, separated | 5.4 (0.14) | 5.6 (0.2) | 5.3 (0.3) | 5.4 (0.3) | 5.4 (0.3) | 0.85 | |

Never married Never married | 6.2 (0.08) | 6.7 (0.2) | 5.9 (0.1) | 6.1 (0.1) | 6.5 (0.2) | <0.01 | |

| Smoked during pregnancy | 0.01 | ||||||

Yes Yes | 5.8 (0.11) | 6.2 (0.2) | 5.4 (0.2) | 5.5 (0.2) | 6.3 (0.3) | 0.01 | |

No No | 5.4 (0.06) | 5.4 (0.1) | 5.2 (0.1) | 5.5 (0.1) | 5.6 (0.1) | 0.01 | |

| Intendedness of pregnancy at conception | <0.001 | ||||||

Intended Intended | 5.1 (0.04) | 5.3 (0.1) | 4.8 (0.1) | 5.1 (0.1) | 5.2 (0.1) | 0.01 | |

Unwanted Unwanted | 6.1 (0.11) | 6.1 (0.2) | 5.7 (0.2) | 6.1 (0.2) | 6.6 (0.3) | 0.03 | |

Mistimed Mistimed | 6.3 (0.12) | 6.3 (0.2) | 6.0 (0.2) | 6.2 (0.2) | 6.7 (0.3) | 0.18 | |

| Gravidity | <0.001 | ||||||

First pregnancy First pregnancy | 5.8 (0.08) | 5.9 (0.1) | 5.4 (0.1) | 5.7 (0.1) | 6.2 (0.2) | <0.01 | |

Not first pregnancy Not first pregnancy | 5.3 (0.05) | 5.4 (0.1) | 5.1 (0.1) | 5.4 (0.1) | 5.5 (0.1) | 0.04 | |

| Pregnancy outcome | <0.001 | ||||||

Livebirth Livebirth | 5.7 (0.05) | 5.7 (0.1) | 5.4 (0.1) | 5.8 (0.1) | 6.1 (0.1) | <0.001 | |

Miscarriage/stillbirth Miscarriage/stillbirth | 4.5 (0.07) | 4.9 (0.1) | 4.3 (0.1) | 4.4 (0.1) | 4.4 (0.1) | 0.02 | |

Ectopic pregnancy Ectopic pregnancy | 4.8 (0.26) | 5.0 (0.3) | 4.6 (0.4) | 4.4 (0.4) | 5.3 (0.7) | 0.50 | |

| Gestational age of pregnancy | <0.001 | ||||||

Less than 12 weeks Less than 12 weeks | 4.1 (0.06) | 4.3 (0.1) | 3.9 (0.1) | 4.1 (0.1) | 4.1 (0.1) | 0.07 | |

12–19 weeks 12–19 weeks | 5.3 (0.16) | 5.7 (0.3) | 5.0 (0.3) | 4.9 (0.3) | 5.9 (0.4) | 0.06 | |

20–29 weeks 20–29 weeks | 6.5 (0.35) | 7.3 (0.7) | 6.2 (0.4) | 6.0 (0.4) | 6.8 (1.1) | 0.56 | |

30–36 weeks 30–36 weeks | 6.2 (0.14) | 6.5 (0.3) | 5.7 (0.2) | 6.2 (0.2) | 6.8 (0.4) | 0.02 | |

37+ weeks 37+ weeks | 5.7 (0.05) | 5.6 (0.1) | 5.4 (0.1) | 5.8 (0.1) | 5.9 (0.1) | <0.01 | |

| Prenatal care initiation | <0.001 | ||||||

Less than 12 weeks Less than 12 weeks | 4.7 (0.03) | 4.7 (0.0) | 4.5 (0.1) | 4.6 (0.1) | 4.8 (0.1) | <0.01 | |

12+ weeks 12+ weeks | 9.5 (0.16) | 8.9 (0.3) | 9.4 (0.3) | 9.5 (0.3) | 10.3 (0.4) | 0.03 | |

No care No care | 5.3 (0.15) | 6.1 (0.3) | 4.9 (0.2) | 5.2 (0.2) | 5.2 (0.4) | 0.08 | |

GED general education development

Mean gestational age at time of pregnancy awareness was significantly associated with all characteristics we considered in our analysis (Table 2). In addition, for most characteristics mean gestational age at time of pregnancy awareness varied among survey periods within levels of the characteristic, with 2002 often showing the lowest estimate. Table 3 shows the predicted prevalence of late (≥7 weeks) pregnancy awareness for each characteristic; findings and patterns regarding groups with prevalence of late timing of pregnancy awareness were similar to those from the mean gestational age analysis in Table 2.

Table 3

Predicted marginal proportions of late pregnancy awareness (≥7 weeks) by maternal and pregnancy characteristics: National Survey of Family Growth, 1995, 2002, 2006–2010, 2011–2013

| All | Pooled (1990–1994–1996–2012)a Pr. (SE) 0.23 (0.01) | 1995 (1990–1994) Pr. (SE) 0.26 (0.01) | 2002 (1996–2002) Pr. (SE) 0.21 (0.01) | 2006–2010 (2000–2010) Pr. (SE) 0.23 (0.01) | 2011–2013 (2005–2012) Pr. (SE) 0.24 (0.01) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at pregnancy conception | |||||

15–19 years 15–19 years | 0.36 (0.01) | 0.36 (0.02) | 0.30 (0.02) | 0.36 (0.02) | 0.41 (0.03) |

20–24 years 20–24 years | 0.27 (0.01) | 0.30 (0.02) | 0.24 (0.02) | 0.25 (0.01) | 0.29 (0.02) |

25–29 years 25–29 years | 0.22 (0.01) | 0.22 (0.02) | 0.21 (0.02) | 0.22 (0.02) | 0.23 (0.03) |

30–34 years 30–34 years | 0.17 (0.01) | 0.20 (0.02) | 0.15 (0.02) | 0.19 (0.02) | 0.16 (0.03) |

35–44 years 35–44 years | 0.17 (0.01) | 0.19 (0.03) | 0.17 (0.03) | 0.17 (0.02) | 0.16 (0.03) |

| Race and ethnicity | |||||

Hispanic or Latina Hispanic or Latina | 0.28 (0.01) | 0.29 (0.02) | 0.23 (0.02) | 0.28 (0.02) | 0.31 (0.03) |

Non-Hispanic white Non-Hispanic white | 0.20 (0.01) | 0.23 (0.01) | 0.18 (0.01) | 0.18 (0.01) | 0.20 (0.02) |

Non-Hispanic black Non-Hispanic black | 0.31 (0.01) | 0.38 (0.02) | 0.28 (0.02) | 0.34 (0.02) | 0.27 (0.02) |

Non-Hispanic other Non-Hispanic other | 0.27 (0.03) | 0.24 (0.05) | 0.26 (0.04) | 0.23 (0.04) | 0.34 (0.06) |

| Educational attainment (at time of interview) | |||||

No high school diploma or GED No high school diploma or GED | 0.29 (0.01) | 0.35 (0.02) | 0.25 (0.02) | 0.29 (0.02) | 0.28 (0.03) |

High school diploma or GED High school diploma or GED | 0.27 (0.01) | 0.29 (0.01) | 0.24 (0.02) | 0.26 (0.01) | 0.29 (0.03) |

Some college, no bachelor’s degree Some college, no bachelor’s degree | 0.24 (0.01) | 0.21 (0.02) | 0.22 (0.02) | 0.23 (0.02) | 0.27 (0.02) |

Bachelor’s degree Bachelor’s degree | 0.15 (0.01) | 0.16 (0.02) | 0.14 (0.02) | 0.14 (0.02) | 0.15 (0.03) |

Master’s degree or higher Master’s degree or higher | 0.15 (0.02) | 0.13 (0.03) | 0.10 (0.02) | 0.21 (0.03) | 0.14 (0.04) |

| Percentage of poverty level (at time of interview) | |||||

Less than 100 % Less than 100 % | 0.31 (0.01) | 0.38 (0.02) | 0.26 (0.02) | 0.31 (0.02) | 0.31 (0.02) |

100 %–299 % 100 %–299 % | 0.24 (0.01) | 0.26 (0.01) | 0.24 (0.02) | 0.22 (0.01) | 0.26 (0.02) |

300 %–399 % 300 %–399 % | 0.17 (0.01) | 0.19 (0.03) | 0.14 (0.02) | 0.19 (0.03) | 0.20 (0.04) |

400 % or more 400 % or more | 0.15 (0.01) | 0.17 (0.02) | 0.15 (0.02) | 0.18 (0.03) | 0.12 (0.02) |

| Marital status at pregnancy conception | |||||

Married Married | 0.18 (0.01) | 0.20 (0.01) | 0.16 (0.01) | 0.18 (0.01) | 0.17 (0.02) |

Widowed, divorced, separated Widowed, divorced, separated | 0.23 (0.02) | 0.27 (0.03) | 0.21 (0.04) | 0.21 (0.03) | 0.25 (0.05) |

Never married Never married | 0.33 (0.01) | 0.39 (0.02) | 0.29 (0.01) | 0.32 (0.01) | 0.34 (0.02) |

| Smoked during pregnancy | |||||

Yes Yes | 0.28 (0.01) | 0.33 (0.02) | 0.50 (0.09) | 0.50 (0.22) | 0.50 (0.14) |

No No | 0.23 (0.01) | 0.24 (0.01) | 0.50 (0.21) | 0.93 (0.09) | 0.18 (0.01) |

| Intendedness of pregnancy at conception | |||||

Intended Intended | 0.22 (0.01) | 0.16 (0.01) | 0.18 (0.01) | 0.17 (0.02) | 0.27 (0.01) |

Unwanted Unwanted | 0.34 (0.02) | 0.29 (0.02) | 0.32 (0.02) | 0.38 (0.03) | 0.22 (0.01) |

Mistimed Mistimed | 0.36 (0.03) | 0.31 (0.02) | 0.32 (0.02) | 0.35 (0.04) | 0.29 (0.01) |

| Gravidity | |||||

First pregnancy First pregnancy | 0.24 (0.01) | 0.20 (0.01) | 0.22 (0.01) | 0.22 (0.02) | 0.13 (0.01) |

Not first pregnancy Not first pregnancy | 0.23 (0.01) | 0.27 (0.02) | 0.29 (0.02) | 0.26 (0.01) | 0.23 (0.04) |

| Pregnancy outcome | |||||

Livebirth Livebirth | 0.27 (0.01) | 0.23 (0.01) | 0.26 (0.01) | 0.28 (0.02) | 0.08 (0.01) |

Miscarriage/stillbirth Miscarriage/stillbirth | 0.19 (0.02) | 0.12 (0.01) | 0.13 (0.02) | 0.11 (0.02) | 0.25 (0.02) |

Ectopic pregnancy Ectopic pregnancy | 0.26 (0.06) | 0.25 (0.07) | 0.21 (0.05) | 0.22 (0.09) | 0.32 (0.04) |

| Gestational age of pregnancy | |||||

| Less than 12 weeks | 0.33 (0.02) | 0.39 (0.03) | 0.30 (0.03) | 0.30 (0.02) | 0.36 (0.04) |

12–19 weeks 12–19 weeks | 0.25 (0.01) | 0.26 (0.01) | 0.23 (0.01) | 0.26 (0.01) | 0.27 (0.02) |

20–29 weeks 20–29 weeks | 0.12 (0.02) | 0.06 (0.01) | 0.10 (0.02) | 0.07 (0.01) | 0.16 (0.01) |

30–36 weeks 30–36 weeks | 0.27 (0.04) | 0.24 (0.04) | 0.21 (0.04) | 0.30 (0.07) | 0.64 (0.01) |

37+ weeks 37+ weeks | 0.46 (0.07) | 0.28 (0.05) | 0.24 (0.06) | 0.35 (0.13) | 0.21 (0.01) |

| Prenatal care initiation | |||||

Less than 12 weeks Less than 12 weeks | 0.17 (0.01) | 0.15 (0.01) | 0.15 (0.01) | 0.16 (0.01) | 0.16 (0.01) |

12+ weeks 12+ weeks | 0.59 (0.02) | 0.61 (0.02) | 0.62 (0.03) | 0.72 (0.04) | 0.72 (0.04) |

No care No care | 0.32 (0.03) | 0.19 (0.03) | 0.21 (0.03) | 0.15 (0.03) | 0.15 (0.03) |

GED general education development

The adjusted prevalence ratios showed significant interactions by survey period for all characteristics except age (Table 4). Age patterns were consistent with what we observed in Tables 2 and and3:3: compared to women aged 25–29, younger women were more likely (PR = 1.31 [1.17, 1.46] and PR = 1.11 [0.99, 1.25]) for women 15–19 and 20–24, respectively) and older women were less likely (PR = 0.82 [0.70, 0.96] and PR = 0.78 [0.66, 0.92]) for women 30–34 and 35–44, respectively) to learn of their pregnancies late. For the results stratified by year, Hispanic women who participated in the 1995, 2006–2010, and 2011–2013 NSFG were more likely than non-Hispanic white women to learn of their pregnancies late; non-Hispanic black women were significantly different from non-Hispanic white women for the 1995 and 2006–2010 survey periods only. In addition, women with unwanted and mistimed pregnancies were more likely than those with intended pregnancies to learn of their pregnancies late in each survey period. Similar patterns were seen with the other characteristics.

Table 4

Prevalence ratio of late pregnancy awareness (≥7 weeks) by maternal and pregnancy characteristics: National Survey of Family Growth, 1995, 2002, 2006–2010, 2011–2013

| Pooled (1990–1994–1996–2012)a PR (CI) | 1995 (1990–1994) PR (CI) | 2002 (1996–2002) PR (CI) | 2006–2010 (2000–2010) PR (CI) | 2011–2013 (2005–2012) PR (CI) | Pb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.11 | ||||||

| Age at pregnancy endc | ||||||

15–19 years 15–19 years | 1.31 (1.17, 1.46) | |||||

20–24 years 20–24 years | 1.11 (0.99, 1.25) | |||||

25–29 years 25–29 years | 1.00 | |||||

30–34 years 30–34 years | 0.82 (0.70, 0.96) | |||||

35–44 years 35–44 years | 0.78 (0.66, 0.92) | |||||

| Race and ethnicityd | 0.04 | |||||

Hispanic or latina Hispanic or latina | 1.19 (1.02, 1.39) | 1.11 (0.92, 1.33) | 1.40 (1.20, 1.64) | 1.35 (1.04, 1.75) | ||

Non-hispanic white Non-hispanic white | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

Non-hispanic black Non-hispanic black | 1.44 (1.25, 1.66) | 1.24 (1.00, 1.55) | 1.60 (1.34, 1.91) | 1.07 (0.82, 1.40) | ||

Non-hispanic other Non-hispanic other | 1.11 (0.73, 1.68) | 1.34 (0.95, 1.89) | 1.20 (0.88, 1.63) | 1.83 (1.40, 2.40) | ||

| Educational attainment (at time of interview)e | 0.04 | |||||

No high school diploma or GED No high school diploma or GED | 1.57 (1.18, 2.09) | 1.31 (0.99, 1.72) | 1.31 (0.92, 1.85) | 1.26 (0.82, 1.94) | ||

High school diploma or GED High school diploma or GED | 1.42 (1.12, 1.80) | 1.40 (1.06, 1.84) | 1.27 (0.90, 1.79) | 1.44 (0.97, 2.14) | ||

Some college, no bachelor’s degree Some college, no bachelor’s degree | 1.11 (0.87, 1.42) | 1.36 (1.06, 1.76) | 1.23 (0.91, 1.67) | 1.46 (0.92, 2.29) | ||

Bachelor’s degree Bachelor’s degree | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

Master’s degree or higher Master’s degree or higher | 0.85 (0.51, 1.42) | 0.75 (0.44, 1.28) | 1.46 (1.03, 2.08) | 1.12 (0.67, 1.88) | ||

| Percentage of poverty level (at time of interview)e | 0.01 | |||||

Less than 100 % Less than 100 % | 1.75 (1.41, 2.16) | 1.36 (1.03, 1.81) | 1.18 (0.90, 1.56) | 1.61 (1.15, 2.27) | ||

100–299 % 100–299 % | 1.33 (1.10, 1.61) | 1.39 (1.04, 1.86) | 0.96 (0.72, 1.27) | 1.55 (1.07, 2.24) | ||

300–399 % 300–399 % | 1.08 (0.76, 1.53) | 0.93 (0.65, 1.33) | 1.08 (0.77, 1.51) | 1.41 (0.93, 2.14) | ||

400 % or more 400 % or more | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Marital status at pregnancy ende | 0.04 | |||||

Married Married | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

Widowed, divorced, separated Widowed, divorced, separated | 1.22 (0.96, 1.54) | 1.16 (0.83, 1.64) | 1.03 (0.76, 1.40) | 1.22 (0.83, 1.79) | ||

Never married Never married | 1.51 (1.29, 1.78) | 1.34 (1.13, 1.60) | 1.30 (1.09, 1.54) | 1.39 (1.06, 1.82) | ||

| Intendedness of pregnancy at conceptionf | 0.02 | |||||

Intended Intended | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

Unwanted Unwanted | 1.31 (1.13, 1.51) | 1.57 (1.30, 1.90) | 1.49 (1.27, 1.75) | 1.78 (1.36, 2.33) | ||

Mistimed Mistimed | 1.56 (1.32, 1.84) | 1.71 (1.36, 2.15) | 1.55 (1.30, 1.86) | 1.85 (1.39, 2.46) | ||

| Graviditye | 0.01 | |||||

First pregnancy First pregnancy | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

Not first pregnancy Not first pregnancy | 1.04 (0.90, 1.20) | 0.96 (0.83, 1.12) | 1.14 (0.99, 1.30) | 1.09 (0.88, 1.35) |

GED general education development

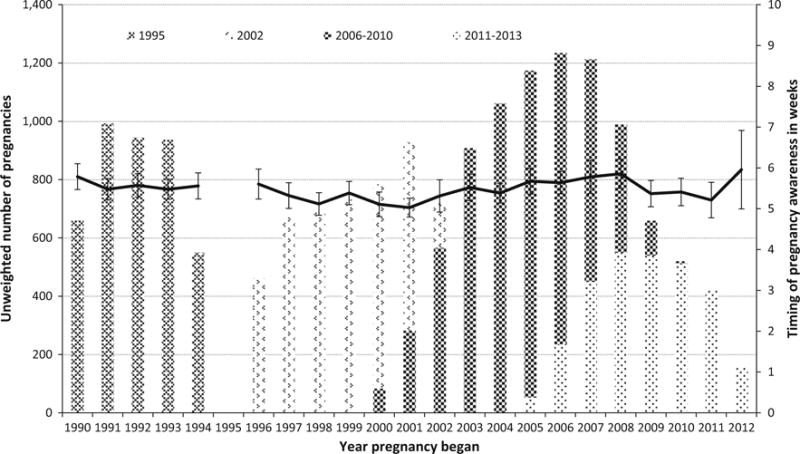

Linear regression of conception year on gestational age at time of pregnancy awareness showed no significant trend using pooled data across the survey periods before or after adjustment for maternal age (per year increase in gestational age at time of pregnancy awareness β = 0.006 [p value = 0.39] and β = 0.0100 [p value = 0.16], respectively) (Fig. 1).

Discussion

In this analysis of over seventeen thousand pregnancies over a 23-year period, we found that gestational timing of pregnancy awareness did not increase or decrease consistently and that on average, women become aware of their pregnancies around 5.5 weeks’ gestation. We also demonstrated that several maternal characteristics measured at conception or during pregnancy, including younger age, never married marital status, smoking during pregnancy, unintended or mistimed pregnancy, prenatal care initiation later than 12 weeks, and maternal characteristics measured at the time of interview, including lower educational attainment, lower poverty-income ratios were associated with pregnancy awareness at 7 weeks or later, although the statistical significance and magnitude of associations varied across time periods. Given the recommendations by ACOG and other professional groups for women to begin folic acid use and to curtail alcohol, recreational drugs, tobacco and nonessential medication use as early in pregnancy as possible, we report that on average, women are still unaware of their pregnancies until between 5 and 6 weeks gestation, the time at which the neural tube is closing and many other organs are in development (Larsen’s Human Embryology 2015).

The literature on timing of pregnancy awareness is relatively scant. However, our results are comparable to at least one other major population-based data system, as well as a previous analysis using NSFG data. Using 2000–2004 Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) data, Ayoola reported a mean gestational age of 5.9 weeks from over 137,000 pregnancies that resulted in a live birth (Ayola 2010). In addition, the percentage of women who reported timing of pregnancy awareness at 6 weeks or less was 23 % in the NSFG and 28 % in the PRAMS data. The higher percentage shown in the PRAMS data may be due to sampling only women who delivered live births, as we found that live birth outcomes in the NSFG data were associated with later pregnancy awareness. Indeed, among live births included in our analysis, gestational age at pregnancy awareness was 5.7 weeks and percentage of late pregnancy awareness was 27 %, providing a very close match to the PRAMS data. Also similar to findings using PRAMS data by Ayoola, we found a higher likelihood of late pregnancy recognition associated with younger age, Hispanic and non-Hispanic black race/ethnicity, lower educational attainment, lower poverty-income ratio, and smoking during pregnancy (Ayoola et al. 2009). Similar findings were observed as well in a previous analysis of 2002 and 2006–2010 NSFG data focused on pregnancy intention and maternal behaviors during and after pregnancies resulting in live birth (Kost and Lindberg 2015).

Given that home pregnancy tests have been available since the mid-1970s, the lack of increase in mean gestation at time of pregnancy awareness during 1990–2012 may be expected. Currently there are 32 urine tests for human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for home and clinical use.4 Although these home pregnancy tests are still most accurate when used within 1 to 2 weeks after a missed period, when hCG is present in concentrations high enough to be detected reliably (>25 mIU/mL hCG) (Butler et al. 2001), some tests promote use before a missed period when hCG levels are lower. Our results do not support a trend towards earlier awareness of pregnancy which may have coincided with increased use of these tests before a missed period, although not all women reporting pregnancies in the NSFG may have become aware of their pregnancy via a home pregnancy test. It is unclear why there was a significant decline in mean gestational age at the time of pregnancy awareness between the 1995 and 2002 surveys as there were no changes in the way the question was asked or any other aspects of the collection of this information. In addition, after adjusting for age, race/ethnicity, and pregnancy intendedness, factors which differed among women in the 2002 NSFG compared to the other survey years, in a post hoc analysis, mean gestational age remained significantly lower among women reporting pregnancies in the 2002 survey although the magnitude of the difference is relatively small. It is possible that the statistical significance is a function of the large numbers of pregnancies examined during this time.

As average gestational age at time of pregnancy awareness has not changed over the last two decades, the potential impact on trends in miscarriage reporting is unclear. In an analysis of pregnancies reported in the 1988, 1995 and 2002 survey periods of the NSFG, Lang and Nuevo-Chiquero reported that miscarriage rates, mainly early miscarriages (7 weeks or less), increased 1 % annually between 1970 and 2000 among women ages 13 to 25 (Lang and Nuevo-Chiquero 2012). In describing these findings the authors conclude that this apparent increase was most likely due to improvements in pregnancy tests which would have increased awareness of early pregnancy. Our results do not support an increase in early pregnancy awareness, at least going back to 1990; however, it is possible that improvements in home pregnancy testing may have occurred between 1970 and 1990.

Our study was not without limitations. First, the question used in the NSFG about timing of pregnancy awareness does not include specifics about how the pregnancy was determined (i.e., home pregnancy test, physician confirmation or other). This prevented examination of trends in timing of pregnancy awareness specific to use of home pregnancy tests. This also prevented examination of how respondents interpreted the question and whether they were measuring pregnancy length using time from conception, first missed period or last menstrual period. Gestational age at time of pregnancy awareness was reported as less than 4 weeks in 25 % of pregnancies included in our analysis. While not biologically implausible, it is unlikely that all these reports reflected positive results of pregnancy tests taken before a missed period. Previous analyses concerning a similar issue with NSFG data have suggested gestational age reports of <4 weeks were actually misclassified gestational ages dated since the time of conception (Jones and Kost 2007) or since the first missed period (Lang and Nuevo-Chiquero 2012). However, Ayoola observed a similar percentage of pregnancies recognized at less than 4 weeks using the PRAMS data, for which a more explicit question concerning pregnancy recognition is used: “How many weeks or months pregnant were you when you were sure you were pregnant? E.g., you had a pregnancy test or a doctor or nurse said you were pregnant.”). In a post hoc analysis, we sought to evaluate our assumption that women with gestational age of pregnancy awareness <4 weeks were more similar to those with awareness at 4, 5 or 6 weeks compared to those with awareness at 7 weeks or later. We compared the maternal characteristics and found that characteristics were very similar between the first two groups compared with the later awareness group.

The greatest strength of our study was our large national sample of pregnancies among US women with detailed information on maternal characteristics, timing of pregnancy awareness and pregnancy outcomes. Further, we could assess trends in timing of pregnancy awareness because this question has been asked in an identical fashion of all recent pregnancies not ending in induced abortion or adoption since the 1995 survey. Our analysis examining how timing of pregnancy awareness changed across 23 years provides the only national trend analysis on this topic. In addition, our sensitivity analyses examined the possible effects of clustering by respondent, finding that within woman differences were larger than the between women differences and that using the primary sample unit as such was more conservative than using the subject identification number in its place to account for clustering.

Over the last two decades, women on average discover that they are pregnant around 5.5 weeks’ gestation and this has remained unchanged. Given that during this same period the recognition for preconception and early conception care and abatement of risk behaviors by public health and women’s health medical organizations has increased (ACOG Committee Opinion number 2005; Floyd et al. 2013) (see footnote 2), these results indicate that many women may still be missing the opportunity to begin folic acid or discontinue risky behaviors during critical windows of fetal development.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lauren Rossen, PhD, Alan Simon, MD, Anjani Chandra, PhD, and Andrea Owens for their input and advice on this manuscript. Dr. Rossen, Dr. Simon and Dr. Chandra are employees of the National Center for Health Statistics in Hyattsville, MD and their work was performed under employment of the US federal government; they did not receive any other compensatory funding.

Footnotes

A previous version of this analysis was presented at the 27th annual meeting of the Society of Pediatric and Perinatal Epidemiologic Research (SPER) in Denver, Colorado, on June 15–17, 2015 and at the National Conference on Health Statistics in North Bethesda, Maryland, on August 24–26, 2015.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (10.1007/s10995-016-2155-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

1Clinical Quality Measure: Prenatal-First Trimester Care Access, Health Resources and Services Administration. http://www.hrsa.gov/quality/toolbox/measures/prenatalfirsttrimester/index.html.

2Get ready for pregnancy. March of Dimes. http://www.marchofdimes.org/pregnancy/get-ready-for-pregnancy.aspx.

3National Center for Health Staistics. National Survey of Family Growth. Questionnaires, datasets and related documentation. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg.htm.

4U.S. Food and Drug Administration Medical Devices Database. Search “home pregnancy test”. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfPMN/pmn.cfm.

References

- ACOG Committee Opinion number 313. The importance of preconception care in the continuum of women’s health care. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;106(3):665–666. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoola AB. Late recognition of unintended pregnancies. Public health nursing. 2015;32(5):462–470. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoola AB, Nettleman MD, Stommel M. Time from pregnancy recognition to prenatal care and associated newborn outcomes. Journal of obstetric gynecologic and neonatal nursing: JOGNN/NAACOG. 2010a;39(5):550–556. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoola AB, Nettleman MD, Stommel M, et al. Time of pregnancy recognition and prenatal care use: A population-based study in the United States. Birth (Berkeley, Calif) 2010b;37(1):37–43. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoola AB, Stommel M, Nettleman MD. Late recognition of pregnancy as a predictor of adverse birth outcomes. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2009;201(2):156.e151–156.e156. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Butler SA, Khanlian SA, Cole LA. Detection of early pregnancy forms of human chorionic gonadotropin by home pregnancy test devices. Clinical Chemistry. 2001;47(12):2131–2136. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Dott M, Rasmussen SA, Hogue CJ, et al. Association between pregnancy intention and reproductive-health related behaviors before and after pregnancy recognition, National Birth Defects Prevention Study 1997–2002. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2010;14(3):373–381. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd RL, Johnson KA, Owens JR, et al. A national action plan for promoting preconception health and health care in the United States (2012–2014) Journal of Womens Health (Larchmt) 2013;22(10):797–802. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RK, Kost K. Underreporting of induced and spontaneous abortion in the United States: An analysis of the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Studies in Family Planning. 2007;38(3):187–197. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kost K, Lindberg L. Pregnancy intentions, maternal behaviors, and infant health: Investigating relationships with new measures and propensity score analysis. Demography. 2015;52(1):83–111. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lang K, Nuevo-Chiquero A. Trends in self-reported spontaneous abortions: 1970–2000. Demography. 2012;49(3):989–1009. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen’s Human Embryology. 5th. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson M, Karasek D, Drey E, et al. Delayed pregnancy testing and second-trimester abortion: Can public health interventions assist with earlier detection of unintended pregnancy? Contraception. 2014;89(5):400–406. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Than LC, Honein MA, Watkins ML, et al. Intent to become pregnant as a predictor of exposures during pregnancy: Is there a relation? The Journal of reproductive medicine. 2005;50(6):389–396. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-2155-1

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc5269518?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

Maternal infection with hepatitis B virus before pregnancy and risk of congenital malformations in offspring: a record-linkage study of a large national sample from China.

Lancet Reg Health West Pac, 48:101121, 28 Jun 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39040040 | PMCID: PMC11262192

Factors associated with timely initiation of antenatal care among reproductive age women in The Gambia: a multilevel fixed effects analysis.

Arch Public Health, 82(1):73, 17 May 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38760806

Race and Ethnicity of Reproductive-Age Females Affected by US State Abortion Bans.

JAMA, 331(20):1765-1767, 01 May 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38691367 | PMCID: PMC11063914

Multilevel negative binomial analysis of factors associated with numbers of antenatal care contacts in low and middle income countries: Findings from 59 nationally representative datasets.

PLoS One, 19(4):e0301542, 18 Apr 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38635815 | PMCID: PMC11025891

Prenatal Care Initiation and Exposure to Teratogenic Medications.

JAMA Netw Open, 7(2):e2354298, 05 Feb 2024

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 38300617 | PMCID: PMC10835507

Go to all (43) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Abortion surveillance--United States, 2009.

MMWR Surveill Summ, 61(8):1-44, 01 Nov 2012

Cited by: 32 articles | PMID: 23169413

Abortion surveillance - United States, 2010.

MMWR Surveill Summ, 62(8):1-44, 01 Nov 2013

Cited by: 26 articles | PMID: 24280963

Prevalence of selected maternal behaviors and experiences, Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), 1999.

MMWR Surveill Summ, 51(2):1-27, 01 Apr 2002

Cited by: 98 articles | PMID: 12004983

Abortion surveillance--United States, 2008.

MMWR Surveill Summ, 60(15):1-41, 01 Nov 2011

Cited by: 29 articles | PMID: 22108620

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

Intramural CDC HHS (1)

Grant ID: CC999999

1 and

1 and