Abstract

Free full text

Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase 1 Regulates Resistance to Infection

Abstract

Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP-1)-deficient mice are resistant to Pseudomonas aeruginosa corneal infections. Corneas healed completely in TIMP-1-deficient mice, and infections were cleared faster in TIMP-1-deficient mice than in wild-type littermates. Genetic suppression studies using matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-deficient mice showed that MMP-9, MMP-3, and MMP-7 but not MMP-2 or MMP-12 are needed for resistance. Increased resistance was also seen during pulmonary infections. These results identify a novel pathway regulating infection resistance.

Twenty-five matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) comprise the major extracellular matrix-degrading activities in mammals. They can remodel matrix during development, tumor metastasis, and cell migration but have nonmatrix substrates as well. MMPs are inhibited posttranslationally by four tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMP-1, TIMP-2, TIMP-3, and TIMP-4) and by α2-macroglobulin (33).

Many correlative studies have suggested that MMP production was associated with inflammation and that MMP inhibition had an anti-inflammatory effect (3-5, 21, 26, 29). More recently, studies with MMP mutant mice have confirmed that MMPs play an important role in promoting inflammation and immunity: overexpression of MMP-1 in lungs promotes a spontaneous emphysema-like response (6), MMP-12 loss attenuates macrophage migration and lung damage caused by cigarette smoke (27), MMP-7 participates in proteolytic activation of antibacterial defensins by epithelial cells (32) and chemoattraction of inflammatory cells to the lung (16), and MMP-3 loss diminishes T-cell-dependent delayed type hypersensitivity responses, while the loss of MMP-9 delays the resolution of those responses (30). TIMP expression has also been associated with a variety of infectious and noninfectious inflammatory conditions, including those affecting the eye (12, 14, 34), and TIMP-3 regulates tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) production (18). Collectively, these data highlight varied and complex roles for components of the TIMP-MMP axis during immune and inflammatory responses; however, TIMPs have not been directly shown to regulate responses to infection. To study the role of TIMP-1 in inflammation and immunity and its possible involvement in other physiological processes, mice deficient in TIMP-1 were generated and evaluated for responses during corneal and pulmonary infections with Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Preparation of Timp1 mutant mice.

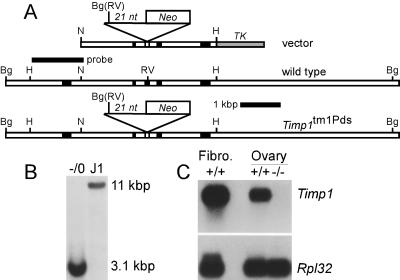

A replacement vector (Fig. (Fig.1A)1A) targeted to the Timp1 locus in embryonic stem (ES) cells (Fig. (Fig.1B)1B) produced a null allele in mice (Fig. (Fig.1C).1C). The replacement vector included a 3.3-kb NdeI to HindIII 5′ arm; a 21-mer oligonucleotide (5′-CTGATCAGCTGACTCGAGG-3′) at an EcoRV site in the third coding exon that abolished the EcoRV site generating BamHI, BglII, and XhoI sites; a G418 drug resistance cassette at the XhoI site; and a TK marker. Electroporated ES clones were screened by Southern blot analysis with a 1,400-nucleotide HindIII-NdeI Timp1 5′ fragment as a probe. Mutant mice were made by injecting blastocysts with targeted ES cells.

Targeting Timp1 with a replacement vector. (A) Vector includes 1.6 kb of Timp1 sequences 5′ of an EcoRV (RV) site within coding exon 3, a stop codon-containing oligonucleotide inserted at the EcoRV site replacing it with a BglII (Bg) site, a neo marker 3′ of the mutating oligonucleotide, 1.6 kb of 3′ Timp1 sequences, and a herpes simplex virus TK marker. Before electroporation into J1 ES cells, the vector was linearized 5′ of the Timp1 sequences. Homologous recombination generated the genomic structure shown. (B) A Southern blot of DNA from ES clones digested with BglII revealed an 11-kb wild-type band in the control (J1) and a 3.1-kb mutant band in the homologous recombinants. Because Timp1 is X-linked and J1 cells are from males, a single mutant band is present in targeted clones. (C) Northern blot of RNA from wild-type (+/+) embryonic fibroblasts and ovaries of wild-type and Timp1 mutant (−/−) mice hybridized to human TIMP1 cDNA and mouse Rpl32 cDNA as a loading control.

Increased infection resistance in Timp1 mutants.

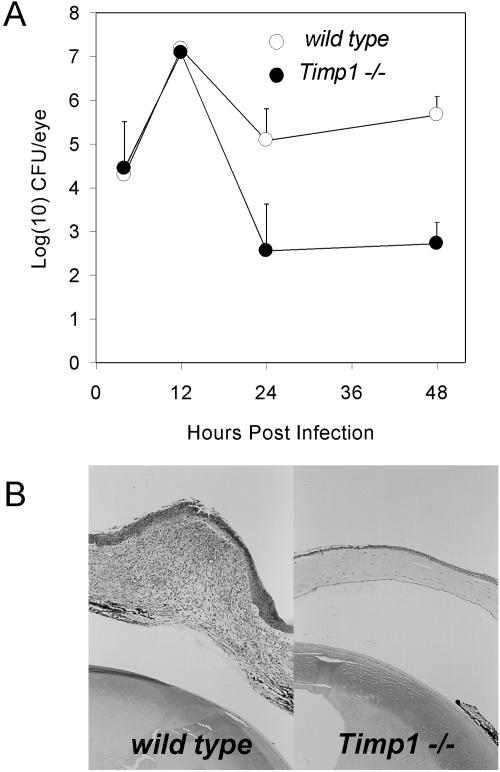

TIMP-1 has been implicated in erythropoiesis (9), wound healing (25), steroidogenesis (2), and tumor metastasis. However, the loss of TIMP-1 in mice caused no detectable changes in these processes (22, 28) or in kidney fibrosis (8), but modest changes were observed in corneal neovascularization (35) and left ventricular geometry (24). However, TIMP-1-deficient mice had dramatically improved bacterial clearance relative to wild-type mice after induction of corneal infections with a human corneal isolate of P. aeruginosa (Fig. (Fig.2A).2A). For corneal infections, we grew nonmucoid P. aeruginosa strain 6389 overnight on tryptic soy agar plates prepared with Noble agar, collected bacteria in sterile proteose peptone (2%), anesthetized mice with tribromoethanol, made three 1-mm scratches with a 26-gauge needle, and placed 5 μl of bacteria (107 CFU) on the corneas. We measured bacterial burdens several times within 5 days after infection by plate count of whole eyes homogenized in 2% proteose peptone. At 4 h after infection of strain 129S4/Jae mice, eyes from wild-type and mutant animals had identical numbers of bacteria, indicating that the initiation of the infection was not altered by the Timp1 mutation. By 12 h after infection, when a burst of P. aeruginosa replication had occurred, comparable numbers of bacteria were recovered from mutant and wild-type eyes, indicating that there was no intrinsic barrier to bacterial replication in mutant mice. By 24 and 48 h after infection, when histological sections revealed that neutrophil infiltration into infected corneas had begun and then peaked, respectively (data not shown), there were 2 to 3 orders of magnitude fewer viable bacteria in eyes of mutant mice than in eyes of wild-type mice. Statistical analysis of bacterial burden was done by analysis of variance (ANOVA). Strain 129 mice recover completely from these infections and are considered resistant. C57BL/6 mice can clear infections too, but they undergo corneal perforation because of unresolved inflammation and are considered infection sensitive (23). By 16 days after infection, wild-type C57BL/6 mice maintained a persistent inflammatory response and underwent perforation; however, TIMP-1-deficient littermates resolved the inflammation completely, and corneal integrity was restored (Fig. (Fig.2B).2B). These results, from two different measures, demonstrated dramatically increased resistance to P. aeruginosa corneal infection in TIMP-1-deficient mice.

Increased resistance to P. aeruginosa in eyes of Timp1−/− mice. Mice on the 129S4/SvJae background were infected with 106 CFU of P. aeruginosa (strain 6389)/ml. (A) At several times after infection, the infected eyes were removed, and bacterial burdens were assayed by plate count of whole-eye homogenates. Each point represents the mean of results from at least four animals. The P values are <0.003 and <0.0001 at 24 and 48 h postinfection, respectively. (B) Histological sections of corneas from representative mutant and wild-type mice on the C57BL/6 background taken 16 days after infection.

MMP-9, MMP-7, and MMP-3 are needed for infection resistance in Timp1 mutants.

To determine whether the increased resistance phenotype was due to the loss of proteinase inhibitory activity in Timp1−/− mice, we repeated the corneal infections in 129S4/Jae mice that were treated with BB-94, a synthetic metalloproteinase inhibitor (7). We first injected animals intraperitoneally with 40 mg of BB-94 (British Biotech, Oxford, England)/kg of body weight daily for 4 days prior to infection and on the day of infection using suspension of BB-94 (3.0 mg/ml) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.01% Tween 40. Over 99% of the enhanced bacterial clearance by mutant mice was suppressed by BB-94 treatment (Table (Table11).

TABLE 1.

Suppression of the infection resistance phenotype in Timp1 mutants by a synthetic proteinase inhibitora

| Timp1 genotype | Treatment | n | CFU/eye | CFU/eye relative to Timp1−/− mice | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −/0 | PBS | 6 | 1.9 × 102 | 1 | 7 × 10−6 |

| +/0 | PBS | 7 | 1.5 × 105 | 790 | |

| −/0 | BB-94 | 5 | 6.5 × 104 | 1 | 0.02 |

| +/0 | BB-94 | 7 | 2.7 × 105 | 4 |

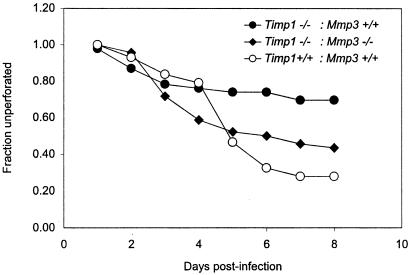

Because BB-94 inhibits MMPs as well as the non-MMP proteinase tumor necrosis factor alpha-converting enzyme (TACE) that releases membrane-bound TNF-α from the surfaces of cells (1, 19), this pharmacological approach did not identify the specific proteinases influencing the infection phenotypes in Timp1−/− mice. However, because TIMP-1 is inactive against TACE (15), it was likely that that the Timp1 mutant phenotype was mediated most directly by an MMP. Nonetheless, to identify the proteinases responsible for the Timp1 mutant phenotype, we took a genetic approach, reasoning that if one or more MMPs are required for the mutant phenotype, then the increased resistance to infection should be suppressed in mice harboring mutations in both Timp1 and the critical proteinases. To perform this analysis, we bred Timp1 mutants with animals carrying lesions in Mmp2 (11), Mmp3 (20), Mmp7 (31), Mmp9 (17), and Mmp12 (10). These animals were available on either the C57BL/6 background or on different 129 backgrounds. Guided by the results shown in Fig. Fig.2,2, the controls and suppression tests used the assay appropriate for the specific strain background: bacterial burden assays for strain 129 mice and kinetics of corneal perforation for C57BL/6 mice. For each cross, control infections were performed with wild-type progeny and mice with only the Timp1 mutation to verify that the Timp1 mutant phenotype could be observed on these backgrounds. On each strain background, Timp1 mutants exhibited significantly increased resistance to infection relative to the wild-type controls, consistent with our earlier data with Timp1−/− mice that had not been crossed into Mmp mutant backgrounds (Table (Table2,2, Fig. Fig.3,3, and data not shown). In Timp1 Mmp9 double mutants, resistance to infection was indistinguishable from the corresponding wild-type control animals but significantly lower than resistance in the Timp1 single mutants on the same background. This result indicated that MMP-9 was essential for the Timp1 phenotype (Table (Table2).2). In Timp1 Mmp7 double mutants and Timp1 Mmp3 double mutants, resistance to infection was significantly higher than in the strain-matched wild-type controls but significantly lower than in the Timp1 single mutant controls. This result indicated that while these two MMPs also contributed to the Timp1 mutant phenotype, they were not by themselves responsible for all of the resistance (Table (Table22 and Fig. Fig.3).3). Suppression analysis using Mmp2 and Mmp12 mutants revealed that they do not contribute to the Timp1−/− phenotype (data not shown). Statistical analysis of corneal perforation data was by log rank testing of all data points in each experiment.

Loss of MMP-3 suppresses resistance to infection in Timp1−/− mice. A total of 43 Timp1+/+ Mmp3+/+ animals, 46 Timp1−/− Mmp3+/+ animals, and 46 Timp1−/− Mmp3−/− animals were infected as described in the legend to Fig. Fig.22 and observed daily for signs of corneal perforation. Perforation in Timp1+/+ Mmp3+/+ and Timp1−/− Mmp3−/− animals were indistinguishable (P = 0.3). However, the rates of perforation of Timp1+/+ Mmp3+/+ and Timp1−/− Mmp3+/+ animals were distinct (P = 0.002).

TABLE 2.

MMP-9 and MMP-7 are needed for the Timp1 mutant corneal phenotypea

| Genotype | n | CFU/eye | CFU/eye relative to Timp1−/− mice | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timp1+/+Mmp9+/+ | 32 | 1.5 × 104 | 63a | 0.2 | |

| Timp1−/−Mmp9−/− | 17 | 4.6 × 104 | 19 | 0.01 | |

| Timp1−/−Mmp9+/+ | 32 | 2.4 × 102 | 1a | ||

| Timp1+/+Mmp7+/+ | 30 | 1.6 × 105 | 2,100b | 0.0004 | |

| Timp1−/−Mmp7−/− | 34 | 5.7 × 103 | 75 | 0.0005 | |

| Timp1−/−Mmp7+/+ | 31 | 76 | 1b |

Enhanced resistance to pulmonary infections in Timp1 mutants.

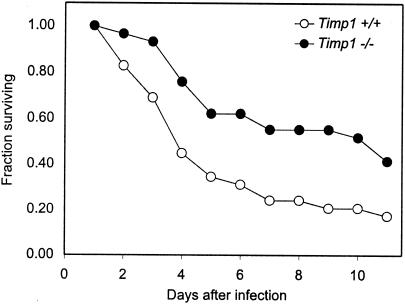

To determine whether TIMP-1-deficient mice also showed enhanced resistance to pulmonary infection, we grew P. aeruginosa strain M57-15 overnight in liquid tryptic soy broth and instilled 107 CFU in 25 μl of solution intratracheally into the right lungs of anesthetized mice. This strain is a mucoid isolate from the lungs of a cystic fibrosis patient. Our assays for bacterial burden and gross appearance of histological sections revealed no differences between Timp1+/+ and Timp1−/− mice at several times after infection. However, survival of mutant animals was significantly improved in TIMP-1-deficient mice (P = 0.008). This result demonstrated that increased resistance to infection in Timp1 mutants is not limited to the cornea (Fig. (Fig.44).

Timp1−/− mice are resistant to pulmonary challenge with P. aeruginosa. Pulmonary infections were established by instilling into the right lungs of mice 25 μl of solution containing 107 CFU of P. aeruginosa (M57-15). Mice were observed daily during the 11-day period following infection, and numbers of survivors were noted. Infected animals included 17 Timp1+/+ and 29 Timp1−/− animals. All mice were strain matched. Timp1−/− mice had significantly better survival than Timp1+/+ mice (P = 0.008).

Loss of TIMP-1 in mice resulted in increased resistance to corneal and pulmonary infection with P. aeruginosa. Resistance to corneal infection could be suppressed by BB-94, indicating that the phenotype was reversible and due to the loss of the proteinase-inhibiting activity of TIMP-1. The proteinases MMP-9, MMP-7, and MMP-3 are each important for resistance; however, the hierarchy of their importance is unknown. Because BB-94 also inhibits TACE (1, 19), BB-94 suppression of the Timp1−/− phenotype may involve effects mediated by TNF-α release. However, suppression of the Timp1 phenotype by loss of MMPs that do not process TNF-α indicates that TNF-α-mediated effects cannot explain the phenotype of Timp1 mutants. Furthermore, in animals with corneal infections, no circulating TNF-α was detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (data not shown); however, local production in the cornea was not tested.

The targets of MMP-9, MMP-7, and MMP-3 that lead to improved resistance to infection in TIMP-1-deficient mice are unknown. It is also unknown whether a single common mechanism is affected in the corneal and pulmonary models. It is possible that dysregulated MMP proteolysis directly modifies innate immunity in Timp1 mutants. Consistent with this are data showing that MMP-7 cleaves mature defensins from precursors (32). Alternatively, innate immunity could be affected indirectly. For example, release of syndecan-1 from epithelial cells by MMP-7 has been shown to influence chemokine mobilization and epithelial transmigration of neutrophils (16). It is not likely that the loss of TIMP-1 affects the ability of infections to become established. During the first 12 h of corneal infections, bacteria adhered to and replicated in the infected corneas equally well in both mutant and wild-type mice (Fig. (Fig.2A).2A). Furthermore, the resistance phenotype was not apparent until large numbers of inflammatory cells were recruited to infected eyes (data not shown).

In contrast to our results showing that the loss of TIMP-1 is protective against infections are studies showing that mice treated with anti-TIMP-1 rabbit serum apparently have increased susceptibility to infection relative to animals treated with normal rabbit serum (13). In those studies, it is possible that the formation of TIMP-1-containing immune complexes activated serum complement leading to its depletion. Increased susceptibility to infections in those animals could then be more influenced by complement depletion and have nothing to do with TIMP-1 depletion. Assays for serum complement or experiments using antibody against an irrelevant serum protein to control for this were not reported. Furthermore, it is not known whether TIMP-1 was actually depleted from mice or if a feedback mechanism increased local synthesis in critical anatomical sites under conditions of systemic TIMP-1 depletion. These caveats are not concerns with the null genetic alteration in Timp1 we report here.

Our results raise the possibility that TIMP-1 antagonists or MMP agonists may be of therapeutic benefit for augmenting resistance to P. aeruginosa. Such agents may be of greatest utility for individuals with unresolved, antibiotic-resistant pulmonary infections, such as cystic fibrosis patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants EY11279 and AI053194 from the National Institutes of Health.

We thank D. Oleszek and K. Somogyi for excellent technical help; Gerald B. Pier for helpful advice; and Steven Shapiro, John Mudgett, Shigeyoshi Itohara, and Lynn Matrisian for mice deficient in MMP-12, MMP-3, MMP-2, and MMP-7, respectively.

REFERENCES

Articles from Infection and Immunity are provided here courtesy of American Society for Microbiology (ASM)

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.73.1.661-665.2005

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc538985?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/102446470

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1128/iai.73.1.661-665.2005

Article citations

Matrix metalloproteinases mediate influenza A-associated shedding of the alveolar epithelial glycocalyx.

PLoS One, 19(9):e0308648, 23 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39312544 | PMCID: PMC11419339

Estrogen-dependent gene regulation: Molecular basis of TIMP-1 as a sex-specific biomarker for acute lung injury.

Physiol Rep, 12(17):e70047, 01 Sep 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 39267201 | PMCID: PMC11392656

TIMP-1 and its potential diagnostic and prognostic value in pulmonary diseases.

Chin Med J Pulm Crit Care Med, 1(2):67-76, 19 Jun 2023

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 38343891 | PMCID: PMC10857872

Immunological aspects of host-pathogen crosstalk in the co-pathogenesis of diabetes and latent tuberculosis.

Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 12:957512, 26 Jan 2023

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 36776550 | PMCID: PMC9909355

TPL-2 Inhibits IFN-β Expression via an ERK1/2-TCF-FOS Axis in TLR4-Stimulated Macrophages.

J Immunol, 208(4):941-954, 26 Jan 2022

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 35082159 | PMCID: PMC9012084

Go to all (37) article citations

Data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

TIMP-1 role in protection against Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced corneal destruction.

Exp Eye Res, 78(6):1155-1162, 01 Jun 2004

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 15109922

Matrix metalloproteinase-9 amplifies the immune response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa corneal infection.

Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 47(1):256-264, 01 Jan 2006

Cited by: 32 articles | PMID: 16384971

Evidence for TIMP-1 protection against P. aeruginosa-induced corneal ulceration and perforation.

Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 40(13):3168-3176, 01 Dec 1999

Cited by: 19 articles | PMID: 10586939

Induction of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitors of MMPs correlates with outcome of acute experimental pseudomonal keratitis.

Exp Eye Res, 83(6):1396-1404, 11 Sep 2006

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 16968651

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NEI NIH HHS (2)

Grant ID: EY11279

Grant ID: R01 EY011279

NIAID NIH HHS (2)

Grant ID: AI053194

Grant ID: P01 AI053194