Abstract

Free full text

A CRISPR-based screen for Hedgehog signaling provides insights into ciliary function and ciliopathies

Abstract

The primary cilium organizes Hedgehog signaling and shapes embryonic development, and its dysregulation is the unifying cause of ciliopathies. We conducted a functional genomic screen for Hedgehog signaling by engineering antibiotic-based selection of Hedgehog-responsive cells and applying genome-wide CRISPR-mediated gene disruption. The screen robustly identifies factors required for ciliary signaling with few false positives or false negatives. Characterization of hit genes uncovers novel components of several ciliary structures, including a protein complex containing δ- and ε-tubulin that is required for centriole maintenance. The screen also provides an unbiased tool for classifying ciliopathies and reveals that many congenital heart disorders are caused by loss of ciliary signaling. Collectively, our study enables a systematic analysis of ciliary function and of ciliopathies and also defines a versatile platform for dissecting signaling pathways through CRISPR-based screening.

Introduction

The primary cilium is a surface-exposed microtubule-based compartment that serves as an organizing center for diverse signaling pathways1–3. Mutations affecting cilia cause ciliopathies, a group of developmental disorders that includes Joubert Syndrome, Meckel Syndrome (MKS), Nephronophthisis (NPHP), and Bardet-Biedl Syndrome (BBS). The defining symptoms of ciliopathies include skeletal malformations, mental retardation, sensory defects, obesity, and kidney cysts and are thought to arise from misregulation of ciliary signaling pathways. Advances in human genetics have led to the identification of over 90 ciliopathy genes4. However, the molecular basis for many ciliopathy cases remains undiagnosed,5 and critical aspects of cilium assembly and function remain poorly understood.

A leading paradigm for ciliary signaling is the vertebrate Hedgehog (Hh) pathway, which plays key roles in embryonic development and in cancers such as medulloblastoma and basal cell carcinoma6,7. Primary cilia are required for Hh signaling output3, and all core components of the Hh signaling machinery – from the receptor PTCH1 to the GLI transcriptional effectors – dynamically localize to cilia during signal transduction.

Efforts to systematically identify genes needed for cilium assembly or Hh signaling have been reported, but these studies relied on arrayed siRNA libraries and exhibit the high rates of false positives and false negatives characteristic of such screens8–11. Recently, genome-wide screening using CRISPR/Cas9 for gene disruption has emerged as a powerful tool for functional genomics12–15. However, the pooled screening format used in these studies requires a means to select for/against or otherwise isolate cells exhibiting the desired phenotype, a requirement that has limited the scope of biological applications amenable to this approach. Indeed, most studies to date have searched for genes that either intrinsically affect cell growth or that affect sensitivity to applied perturbations16–23.

Here, we engineered a Hh pathway-sensitive reporter to enable an antibiotic-based selection platform. Combining this reporter with a single guide RNA (sgRNA) lentiviral library targeting the mouse genome, we conducted a CRISPR-based screen that systematically identified ciliary components, Hh signaling machinery, and ciliopathy genes with few false positives or false negatives. We further show that previously uncharacterized hits encode new components of cilia and centrioles and also include novel ciliopathy genes.

Results

Development of a Hh pathway reporter for pooled screening

Pooled functional screening requires the ability to enrich or deplete mutants that exhibit a desired phenotype. Because ciliary signaling is not intrinsically linked to such a selectable phenotype, we engineered a reporter that converts Hh signaling into antibiotic resistance (Fig. 1A–B). This transcriptional reporter was introduced into mouse NIH-3T3 fibroblasts, a widely used cell line for Hh signaling and cilium biology24, and these cells were then modified to express Cas9-BFP (3T3-[Shh-BlastR;Cas9] cells).

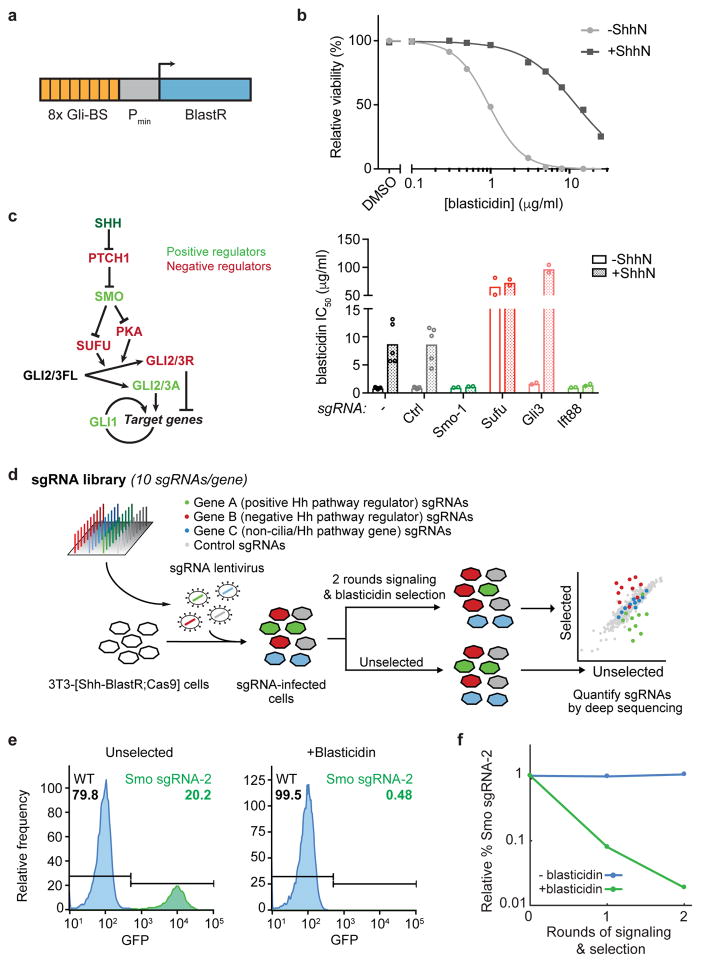

a) A transcriptional reporter combining 8 copies of the GLI binding sequence (Gli-BS) with a minimal promoter (Pmin) to convert Hh signals into blasticidin resistance. b) Blasticidin resistance was assayed across a range of concentrations in stimulated (+ShhN) and unstimulated 3T3-[Shh-BlastR;Cas9] cells. Representative curves of 5 independent experiments performed in duplicate. c) Overview of the Hh pathway, with key negative and positive regulators shown in red and green, respectively (left). Effects of control sgRNAs on blasticidin resistance in stimulated and unstimulated 3T3-[Shh-BlastR;Cas9] cells (right). Bars show mean inhibitory concentration 50 (IC50) values and circles show IC50 values from N = 2 (for gene-targeting sgRNAs) or 5 (for no sgRNA and negative control (Ctrl) sgRNA) independent experiments performed in duplicate. d) Overview of the screening strategy. Cells receiving a negative control sgRNA, a positive regulator-targeting sgRNA, and a negative regulator-targeting sgRNA are shaded grey, green, and red, respectively. e) Flow cytometry histograms of cell mixtures showing the fraction of GFP positive (Smo sgRNA-2, green) cells either in the absence of selection (left) or after two rounds of signaling and selection (right). Representative results from three independent experiments. f) Quantification of cell depletion as in (e).

To validate our reporter cell line, we virally introduced sgRNAs targeting regulators of the Hh pathway (Supplementary Table 1). The transmembrane receptor SMO and intraflagellar transport (IFT) complex subunit IFT88 are required for Hh signaling, while SUFU and GLI3 restrain Hh pathway activity (Fig. 1c, left). As expected, sgRNAs targeting Smo or Ift88 severely reduced Sonic Hedgehog N-terminal domain (ShhN)-induced blasticidin resistance, while deleting Gli3 potentiated blasticidin resistance and targeting Sufu led to ligand-independent blasticidin resistance (Fig. 1c, right). These effects on blasticidin resistance were paralleled by concordant changes in endogenous pathway outputs, including GLI1 expression and changes in GLI3 processing (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Additionally, Western blotting confirmed loss of target protein expression for Gli3, Ift88, and Sufu sgRNAs (Supplementary Fig. 1a,b).

We next tested the suitability of our reporter cells for pooled screening, which involves quantifying sgRNAs in blasticidin-selected and unselected cell pools to identify sgRNAs that confer a selective advantage or disadvantage (Fig. 1d). We mimicked screening conditions by mixing GFP-marked cells expressing a Smo sgRNA with mCherry-marked cells expressing a portion of our genome-wide sgRNA library. Flow cytometry revealed that the fraction of Smo sgRNA-transduced cells decreased by >12-fold and by >50-fold after one and two rounds of signaling and selection, respectively, thus indicating that our strategy is suitable for pooled screening (Fig. 1e,f).

Genome-wide screening

We conducted our genome-wide screen using a newly developed mouse sgRNA library25. Key features of this library are the use of 10 sgRNAs per gene and the inclusion of >10,000 negative control sgRNAs that are either non-targeting or that target “safe” sites with no predicted functional role (Supplementary Fig. 2a). We lentivirally transduced 3T3-[Shh-BlastR;Cas9] cells with this library at low multiplicity of infection and maintained sufficient cell numbers to ensure ~1000X coverage of the library. Cells were next exposed to ShhN for 24 h to fully stimulate Hh signaling, split into separate blastidicin-selected and unselected pools, and then subjected to a second cycle of signaling and selection before sgRNA quantification by deep sequencing (Fig. 1d). Genes affecting ciliary signaling were identified by comparing sgRNAs in the blastidicin-selected versus unselected cell pools, while genes affecting proliferation were identified by comparing the plasmid sgRNA library to the sgRNA population after 15 days growth in the absence of blasticidin. For statistical analysis, a maximum likelihood method termed casTLE26 was used to determine a P value for each gene from the changes in sgRNA abundance. In addition, the casTLE method estimates the apparent strength of the phenotype (effect size) caused by knockout of a given gene.

Assessment of screen performance

We first assessed our ability to detect genes affecting growth. This readout is independent of our reporter-based selection strategy and enables comparisons to other proliferation-based screens. Using reference positive and negative essential gene sets27, we found that our screen identified >90% of essential genes with a 5% false discovery rate (FDR) (Supplementary Fig. 2b and Supplementary Tables 2–3). This performance validates the design of our sgRNA library and is comparable to that seen with other recently described libraries18,20.

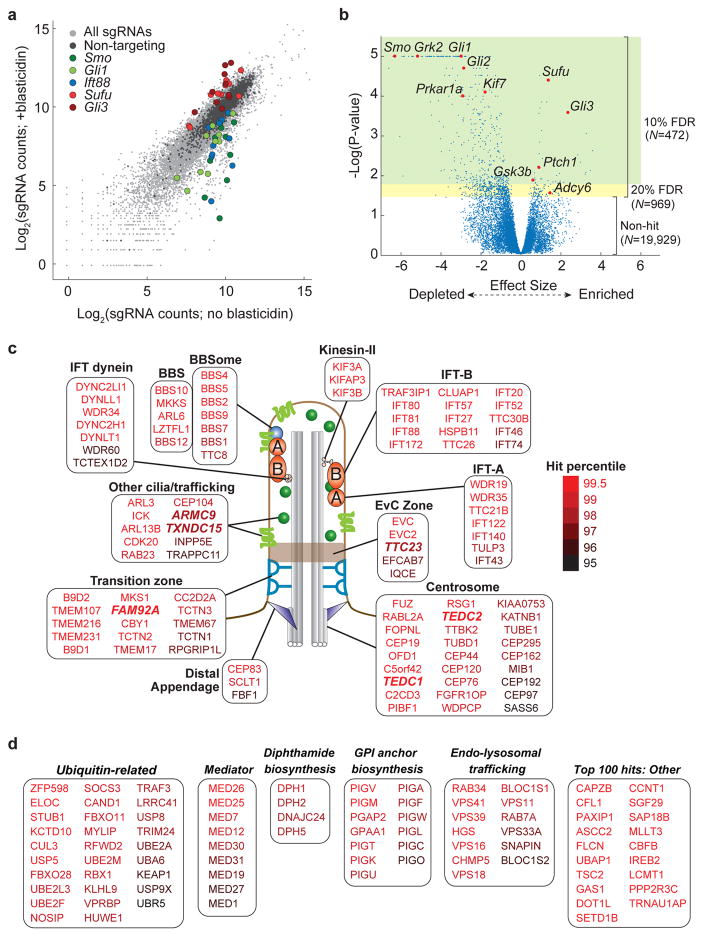

We next evaluated the ability of our screen to identify genes known to participate in ciliary Hh signaling. Initial inspection of screen results for Smo, Ift88, Gli1, Gli3, and Sufu revealed several sgRNAs targeting each gene that were depleted or enriched as expected upon blasticidin selection (Fig. 2a). Virtually all known Hh signaling components were among the top hits, including positive regulators Smo, Grk2, Kif7, Prkar1a, Gli1, and Gli2 and negative regulators Ptch1, Adcy6, Gsk3b, Sufu, and Gli3 (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 4). Our screen also recovered hits that encompass nearly all functional and structural elements of cilia, highlighting the diverse features of cilia needed for signaling (Fig. 2c). For example, several hits encode components of the basal body that nucleates the cilium, the transition fibers that anchor the basal body to the cell surface, the transition zone that gates protein entry into the cilium, the motors that mediate intraciliary transport, and the IFT complexes that traffic ciliary cargos (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Table 4). We observed no apparent correlation between growth and signaling phenotypes, indicating that our antibiotic selection strategy is not biased by general effects on proliferation (Supplementary Fig. 2c).

a) Scatter plot showing log2 of normalized sgRNA counts in selected versus unselected cell pools, with sgRNAs targeting select genes highlighted. b) Volcano plot of casTLE P values versus effect sizes for all genes (after filtering; see Methods), with select Hh pathway components highlighted. Green area indicates P-value cutoff corresponding to 10% false discovery rate (FDR); combined green and yellow areas indicate 20% FDR, with the number of genes in each area indicated. c) Schematic illustration of a primary cilium, with known structural features and select protein products of hit genes shown. Proteins shown are grouped by protein complex membership or localization, with select newly identified hits highlighted in bold, italic font. d) For the indicated categories, proteins encoded by hit genes identified are listed in order of statistical confidence. In addition to select gene ontology terms enriched among screen hits, the top 100 hits not otherwise listed in panels a–c are shown.

In total, we obtained 472 hits at a 10% FDR and 969 hits at a 20% FDR, and 92% of these hits led to decreased rather than increased signaling (Fig. 2b). This asymmetry indicates that, under the saturating level of ShhN used here, many genes are required to sustain high-level signaling while fewer genes act to restrain pathway output. Gene ontology (GO) term analysis using DAVID28 revealed that the top 472 hit genes were enriched for expected functional categories (e.g. cilium morphogenesis, P = 9.6×10−61; Smoothened signaling pathway, P < 3.6×10−32) as well as some novel categories, indicating new avenues for investigation (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Table 5). In some cases, corroborating reports support these new connections: mouse mutants for two hit genes that enable diphthamide modification exhibit Hh pathway-related phenotypes such as polydactyly29,30, and DPH1 mutations likewise cause a syndrome with ciliopathy-like features31.

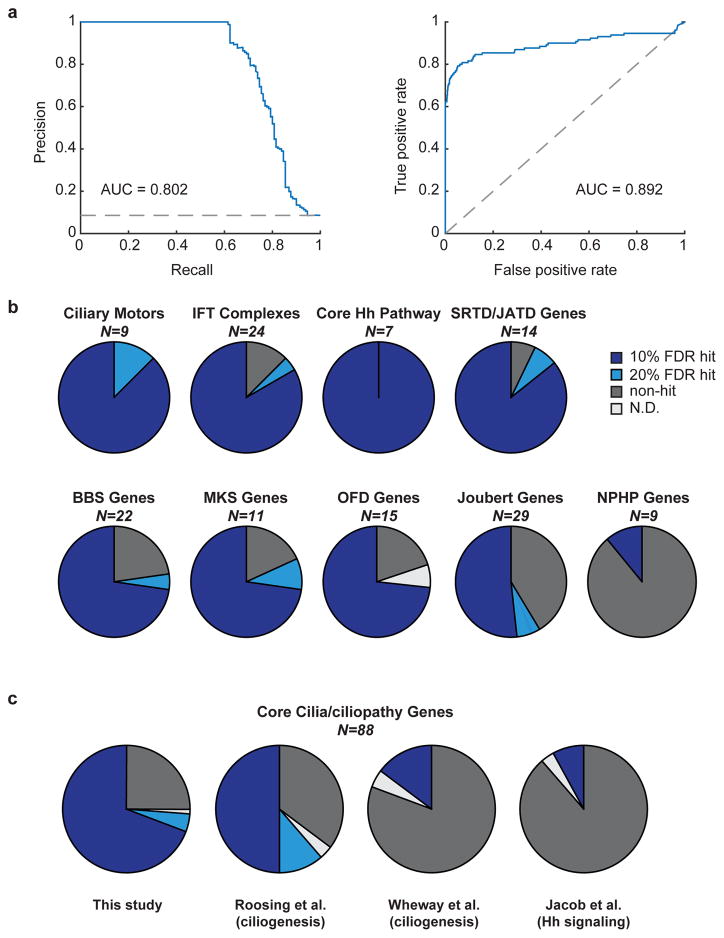

We next sought to use reference sets of expected hit and non-hit genes to quantitatively assess screen performance. We curated a set of ciliogenesis reference genes8 to generate a list of 130 expected hits; for expected non-hits we used 1386 olfactory and vomeronasal receptor genes (Supplementary Table 3). We then calculated precision-recall and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves (Fig. 3a) from the P values generated by casTLE. Both performance metrics showed a high area under the curve (0.802 for precision-recall, 0.892 for ROC), demonstrating that our screen detects hits with high sensitivity and precision (Fig. 3a).

a) Assessment of screen performance using 130 positive and 1386 negative reference genes, as determined by precision-recall analysis (left) and ROC curve (right), with the area under each curve (AUC) shown. Dashed lines indicate performance of a random classification model. b) Analysis of hit gene detection for select gene categories (N = number of genes in each category), with the fraction of hits detected at 10% or 20% FDR, not detected, or not determined shown; see Supplementary Table 3 for details. The NPHP category includes genes mutated exclusively in NPHP and not other ciliopathies. Abbreviations: SRTD (short rib thoracic dysplasia), JATD (Jeune asphyxiating thoracic dysplasia), OFD (Oral-Facial-Digital Syndrome). c) Hit gene identification is compared for the indicated datasets. Pie charts show the fraction of N=88 genes detected as hits across all genes included in part (b), except the NPHP-specific category; see Supplementary Fig. 3a for detail among individual categories.

As a second means of evaluation, we compared our ability to detect expected hit genes to that of three related screens. These studies used arrayed siRNA-based screening to study either Hh signaling using a luciferase reporter10 or ciliogenesis using microscopy-based measures of ciliary markers8,9. While there are notable differences among the screens (e.g. Roosing et al. incorporated gene expression data to score hits8), they each defined a number of hit genes similar to our screen. Overall, we detected the vast majority of expected hits across functional categories ranging from Hh pathway components to ciliopathy genes. Furthermore, even though our screen was focused on Hh signaling, we detected a greater fraction of ciliary hits than the ciliogenesis screens across categories including IFT subunits, ciliary motors, and nearly all classes of ciliopathy genes (Fig. 3b,c, Supplementary Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 4). Indeed, among the 88 genes encompassed by the categories shown in Fig. 3b (except for NPHP-specific genes; see below), we detect 65 as hits, indicating that our screen is approaching saturation (Fig. 3c). Interestingly, few hits were found for genes mutated exclusively in NPHP, raising the possibility that NPHP pathophysiology is distinct from that of other ciliopathies (see Supplementary Note).

As a final assessment of our screening platform, we evaluated reproducibility across replicate screens. We observed high concordance among hits for the 95 genes measured in two different batches of the screen, with 50 of 54 screen hits also scoring as hits in the second batch (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Similarly, strong overlap in hits was found for 263 genes that were screened using two similar but distinct activators of Hh signaling: PTCH1 ligand (ShhN) and SMO agonist (SAG) (Supplementary Fig. 3c). This reproducibility makes it possible to pinpoint genes acting at specific steps in Hh signal transduction. For example, Gas1 was a hit in the ShhN screen but not in the SAG screen, a result in agreement with GAS1’s known function as a Shh co-receptor32,33.

Identification of new ciliary components

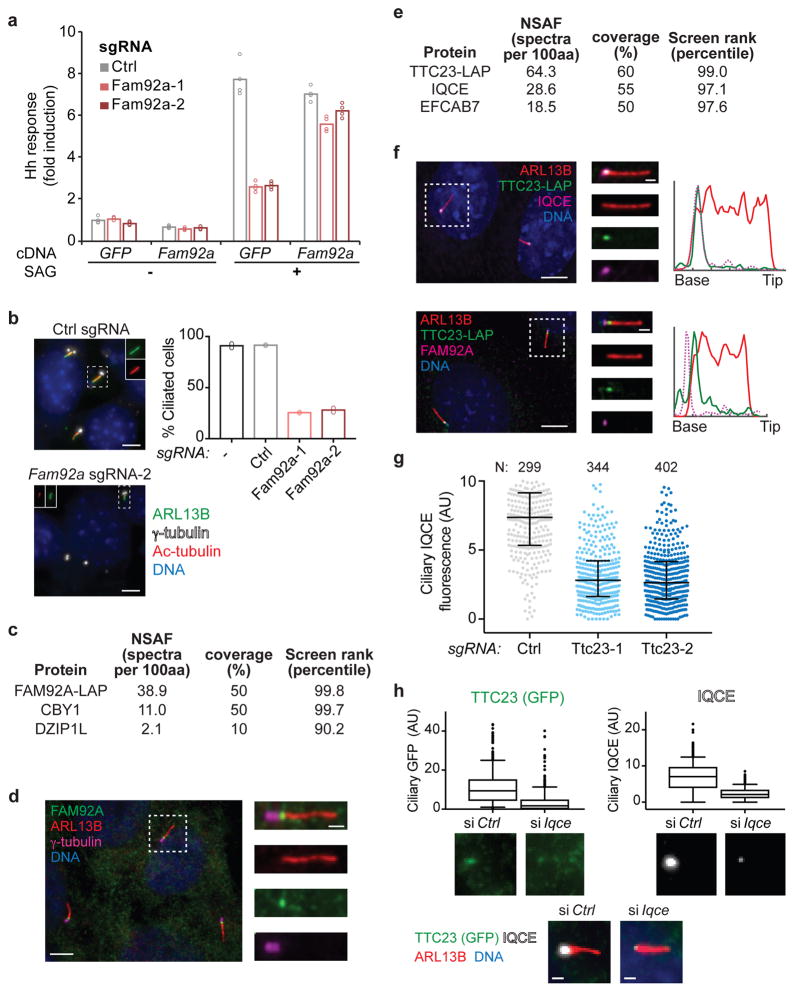

To further establish the value of our screen, we next set out to characterize six previously unstudied hit genes. We first focused on Fam92a and Ttc23 because their gene products contain domains associated with membrane trafficking. For Fam92a, we generated mutant cell pools using individually cloned sgRNAs and confirmed by sequencing that most cells harbored likely null alleles34. Indeed, a high rate of mutagenesis was observed for all genes characterized here and below (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Fam92a disruption caused a strong defect in inducible blasticidin resistance (Supplementary Fig. 4b). This defect was also seen for induction of luciferase from a GLI binding site reporter and could be rescued by sgRNA-resistant Fam92a (Fig. 4a), indicating that the phenotype is specific and independent of the blasticidin-based readout. Notably, ciliogenesis was severely reduced in Fam92a knockout cell pools (Fig. 4b). To gain further insight into Fam92a function, we identified FAM92A-associated proteins from cells expressing FAM92A-LAP (S-tag-HRV3C-GFP localization and affinity purification tag). FAM92-LAP purification specifically recovered CBY1 and DZIP1L, which are components of the transition zone (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Table 6)35–37. Consistent with this finding, we observed FAM92A localization at the transition zone using a validated antibody (Supplementary Fig. 4c,d) and the FAM92A-LAP cell line (Fig. 4d). While this work was in progress, another group independently established FAM92A as a transition zone protein that interacts with CBY1 and promotes ciliogenesis38.

a) Induction of Hh pathway luciferase reporter is shown for cells transduced with the indicated sgRNAs and transfected with plasmids encoding Fam92a-3xFLAG (Fam92a) or GFP-FKBP (GFP). Cells were untreated or stimulated with SAG. Bars show mean of 4 replicate measurements (circles); one of two representative experiments. b) Analysis of cilia in 3T3-[Shh-BlastR;Cas9] cells transduced with the indicated sgRNAs. Bars show mean percentage of ciliated cells; dots show ciliated percentage in each of two independent experiments (>200 cells analyzed per datapoint). Scale bar: 5 μm c) Mass spectrometry analysis of FAM92A-associated proteins purified from IMCD3 cells. The normalized spectral abundance factor (NSAF), the percent of each protein covered by identified peptides, and the percentile rank of the corresponding gene in the screen are indicated. d) FAM92A localizes to the transition zone of IMCD3 cells, distal to centrioles (γ-tubulin) and proximal to the ciliary membrane (ARL13B). One of two independent experiments (five fields of view each). Scale bars: 5 μm and 1 μm (insets). e) Mass spectrometry analysis of TTC23-associated proteins purified from IMCD3 cells. f) TTC23-LAP co-localizes with IQCE, distal to FAM92A, in IMCD3 cells. Line plots show normalized intensity along the length of the cilium; tick marks are 1 μm intervals. Representative images are shown from two independent experiments (five fields of view each). Scale bars: 5 μm and 1 μm (insets). g) The median and interquartile range of ciliary IQCE levels are shown for cells transduced with the indicated sgRNAs; one of two independent experiments. h) Ciliary TTC23-LAP and IQCE signals were analyzed following introduction of Iqce-targeting or control (Ctrl) siRNAs. The median, interquartile range (box boundaries), 10–90% percentile range (whiskers), and outliers are plotted for N=390 (Ctrl) and N=300 (Iqce) cilia. One of two (IQCE) or four (GFP) replicate experiments. Scale bars: 1 μm.

To characterize the TPR domain-containing protein TTC23, we identified TTC23-interacting proteins by affinity purification and mass spectrometry. Notably, the most prominent TTC23-associated proteins were IQCE and EFCAB7, which localize to a proximal region of the cilium known as the Ellis-van Creveld (EvC) zone (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Table 6)39,40. While the four known EvC zone proteins are dispensable for cilium assembly, they are all important for Hh signaling. Furthermore, mutations that affect EvC zone proteins EVC and EVC2 cause the ciliopathy Ellis-van Creveld syndrome39–41. Consistent with TTC23 being a new EvC zone component, TTC23-LAP co-localized with EVC and IQCE at the EvC zone (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 4e). Although Ttc23 knockout had no effect on cilium assembly, mutant cells exhibited decreased blasticidin resistance and reduced localization of IQCE and EVC to the EvC zone (Fig. 4g and Supplementary Fig. 4b,f–h). Conversely, Iqce RNAi led to decreased localization of TTC23-LAP to the EvC zone (Fig. 4h). Together these results establish TTC23 as a novel EvC zone component that participates in Hh signaling.

Identification of novel disease genes

Because the vast majority of ciliopathy genes were hits in the screen, we asked whether uncharacterized hit genes may be mutated in ciliopathies of previously unknown etiology. We first examined Txndc15, which encodes a thioredoxin domain-containing transmembrane protein. A previous analysis of MKS patients identified a family with a TXNDC15 mutation; however, a coincident EXOC4 variant was favored as the causative mutation42. We analyzed Txndc15 knockout cells using the luciferase reporter assay, finding a clear defect in Hh signaling. Furthermore, wildtype Txndc15 rescued this defect, whereas the mutant allele found in MKS patients behaved like a null allele (Fig. 5a). We also found that cilia in Txndc15 knockout cells exhibited increased variability in length and decreased levels of the ciliary GTPase ARL13B (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 5a,b). Thus, TXNDC15 likely represents a novel MKS gene. Consistent with our findings, a very recent follow-up study has identified additional MKS families with TXNDC15 mutations and characterized ciliary defects resulting from TXNDC15 disruption43.

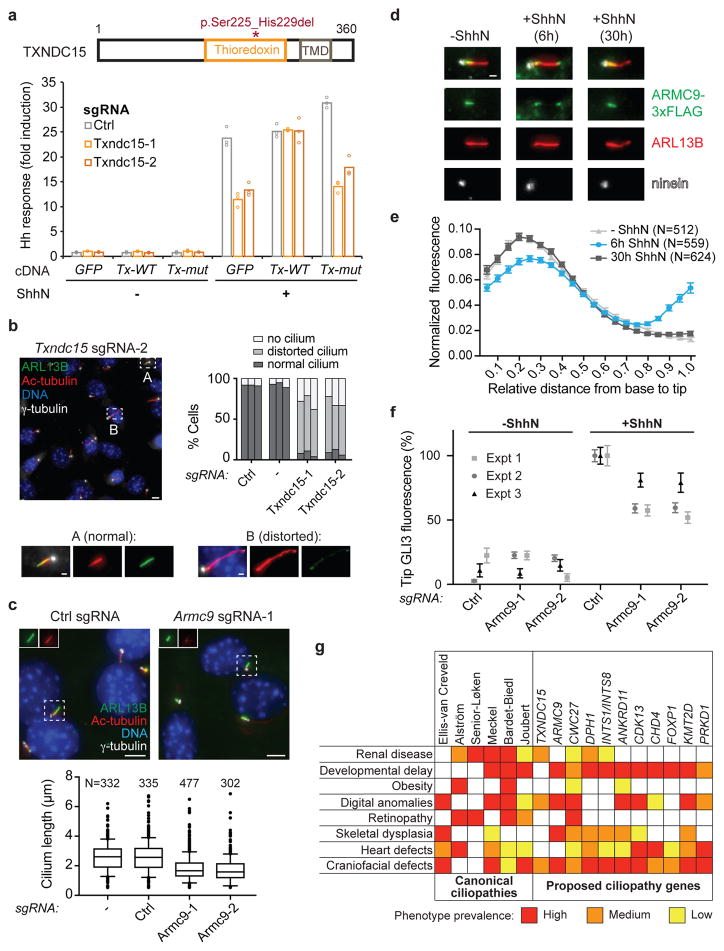

a) TXNDC15, with the transmembrane domain (TMD), thioredoxin domain, and MKS-associated mutation indicated (top). Luciferase reporter levels were measured for cells transduced with the indicated sgRNAs and transfected with plasmids encoding GFP-FKBP (GFP), wildtype Txndc15 (Tx-WT), or mutant Txndc15 (Tx-mut). Bars show mean of 3 replicates (circles); one of two representative experiments. b) Cilia were analyzed in 3T3-[Shh-BlastR;Cas9] cells transduced with the indicated sgRNAs. Bars in graph show percentage of cells with cilia that are normal, distorted, or absent. Each bar per condition represents an independent experiments with >200 cells counted. Scale bars: 5 μm and 1 μm (insets). c) Cilia were analyzed in 3T3-[Shh-BlastR;Cas9] cells transduced with the indicated sgRNAs. Representative images are shown at top. At bottom, the median cilium length, interquartile range (box boundaries), 10–90% percentile range (whiskers), and outliers are plotted. One of three independent experiments. Scale bars: 5 μm. d) Analysis of ARMC9-FLAG localization relative to centrioles (ninein) and ciliary membrane (ARL13B) is shown for IMCD3 cells treated as indicated. Scale bar: 1 μm. e) ARMC-FLAG intensity along the length of the cilium from base (position 0) to tip (position 1.0) was measured for IMCD3 cells treated as indicated. The mean and standard deviation are plotted after normalizing the total intensity in each cilium to 1.0; one of three representative experiments. f) Fluorescence intensity of GLI3 at the cilium tip was measured for the indicated cells in the presence or absence of ShhN. Mean and standard error of the mean are shown for each of N=3 independent experiments (at least 250 cilia analyzed per condition). g) Table showing select clinical features in canonical ciliopathies and their observation in the context of specific mutations and syndromes. Colors indicate high (red), moderate (orange) and low (yellow) prevalence.

Our observation of Armc9 as a screen hit raises the possibility that it is also a ciliopathy gene. Recently, Kar et al. reported that individuals with a homozygous mutation in ARMC9 present with mental retardation, polydactyly, and ptosis, but a diagnosis of Bardet-Biedl syndrome was disfavored44,45. We found that cilia from Armc9 mutant cells were short and exhibited reduced levels of acetylated and polyglutamylated tubulin (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 5c). Furthermore, ARMC9-3xFLAG localized to the proximal region of cilia when stably expressed in IMCD3 or NIH-3T3 cells (Fig. 5d,e and Supplementary Fig. 5d). Notably, stimulation of Hh signaling in IMCD3 cells led to redistribution of ARMC9 towards the ciliary tip within 6 hr before a gradual return to its original proximal location, suggesting that ARMC9 might become ectocytosed from the cilium tip at later time points46,47 (Fig. 5d,e). This change in localization was due to Hh signaling, as it was blocked by SMO inhibitor vismodegib (Supplementary Fig. 5e). Furthermore, Armc9 mutant NIH-3T3 cells exhibited reduced ciliary accumulation of GLI2 and GLI3 (but not SMO) upon pathway activation, suggesting that ARMC9 participates in the trafficking and/or retention of GLI proteins at the ciliary tip (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Fig. 5f–h). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that ARMC9 is a ciliary signaling factor and suggest that ARMC9 is a novel ciliopathy gene. Indeed, a recent report confirms that ARMC9 is mutated in Joubert Syndrome and finds that loss of the zebrafish ortholog disrupts cilium assembly and function48. This study further reports that ARMC9 localizes to centrioles in RPE cells, whereas we find ARMC9-FLAG localizes to cilia (Fig. 5d,e and Supplementary Fig. 5d) and is present in the ciliary proteome (D. Mick and M. Nachury, personal communication). While the basis for these differing observations warrants further investigation, together these data reveal an important role for ARMC9 in ciliary signaling.

Our evidence that ARMC9- (and DPH1-) based syndromes likely represent unrecognized ciliopathies led us to ask whether our screen could help classify other genetic disorders as ciliopathies. Consistent with this possibility, CWC27, which encodes a peptidyl-prolyl isomerase, and INTS1 and INTS8, which encode subunits of the Integrator, are orthologues of screen hits for which patient mutations have recently been described49. Some canonical ciliopathy symptoms are present in these patients, and thus these disorders may stem from altered ciliary signaling (see Supplementary Note).

These cases of individual disorders that can now be classified as likely ciliopathies led us to ask whether systematic efforts to map disease genes might reveal broader commonalities with our screen hits. Strikingly, we found that human orthologues of screen hits Ankrd11, Cdk13, Chd4, Foxp1, Kmt2d, and Prkd1 were all identified in an exome sequencing study of patients with congenital heart defects (CHD)50,51. The significant overlap in these two unbiased datasets (P = 6.11 × 10−4) indicates that defective ciliary signaling may be a prevalent cause of CHDs. Moreover, mutations in these genes appear to cause bona fide ciliopathies, as patients also exhibit ciliopathy symptoms including craniofacial abnormalities and developmental delay (ANKRD11, CDK13, CHD4, FOXP1, KMT2D, PRKD1), dysgenesis of the corpus callosum (CDK13), polydactyly (CHD4), obesity (ANKRD11), and craniofacial malformations (ANKRD11 and KMT2D)4,50,52 (Fig. 5g).

A new protein complex for centriole stability

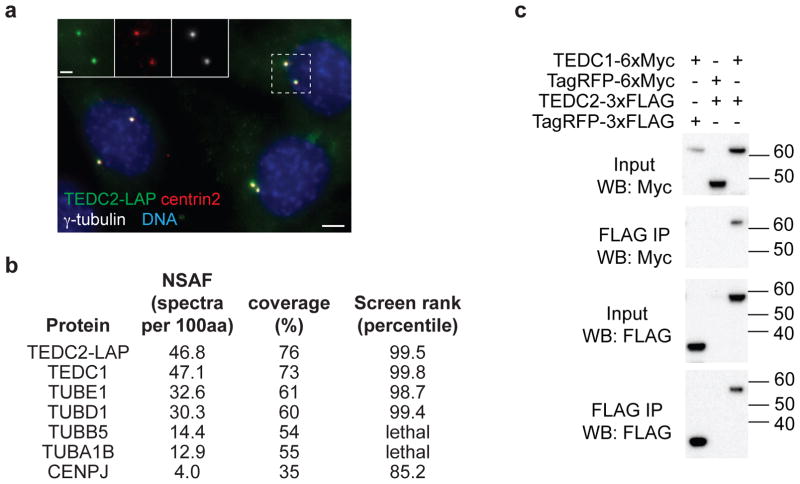

Because our screen hits encode centriolar proteins CEP19, CEP44, CEP120, and CEP29553–62, we considered whether other hits might also have centriolar functions. Indeed, the protein encoded by uncharacterized hit 1600002H07Rik (human C16orf59) localized to centrioles in IMCD3 cells (Fig. 6a). We performed affinity purifications and found that 1600002H07Rik-LAP co-purified with the uncharacterized protein 4930427A07Rik (human C14orf80) and the distant α/β-tubulin relatives ε-tubulin (TUBE1) and δ-tubulin (TUBD1) (Fig. 6b). All four of the genes encoding these proteins are hits in our screen, and ε-tubulin and δ-tubulin have previously been linked to centriole assembly and maintenance63–67. We therefore propose to name 4930427A07Rik/C14orf80 and 1600002H07Rik/C16orf59 as Tedc1 and Tedc2, respectively, for their association with a tubulins epsilon and delta complex.

a) IMCD3 cells stably expressing TEDC2-LAP were immunostained with antibodies to centrin2 and γ-tubulin to visualize centrioles. Scale bar: 5 μm (2 μm for insets). Representative images are shown for three independent experiments. b) Mass spectrometry analysis of TEDC2-associated proteins purified from IMCD3 cells reveals TEDC1, ε-tubulin, δ-tubulin in nearly stoichiometric amounts, as well as α/β-tubulin and CENPJ. For each protein, the normalized spectral abundance factor (NSAF), the percent of the protein covered by identified peptides, and the percentile rank of the corresponding gene in the screen dataset are indicated. c) Binding of TEDC1 and TEDC2 was assessed via co-immunoprecipitations performed in HEK293T cells transfected with plasmids encoding the indicated proteins. Recovered proteins were analyzed by Western blot. Representative blots are shown for two independent experiments. See also Supplementary Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 8.

Our mass spectrometry analysis of TEDC2-associated proteins revealed approximately stoichiometric amounts of TEDC1, TEDC2, ε-tubulin, and δ-tubulin, as seen by comparison of the normalized spectral abundance factors (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Table 6). We also recovered lower amounts of α/β-tubulin and CENPJ, a centriolar regulator of microtubule dynamics68–70. We confirmed co-purification of TUBD1 and TUBE1 with TEDC2 by Western blot, readily detecting these proteins in our TEDC2-LAP purification but not in a control purification (Supplementary Fig. 6a). The interaction between TEDC1 and TEDC2 could also be detected by co-transfection and co-immunoprecipitation, and moreover we found that TEDC1 and TEDC2 mutually stabilize each other’s expression (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 6b). In further support of our data, two large-scale proteomic datasets have also identified interactions among TED complex proteins71,72.

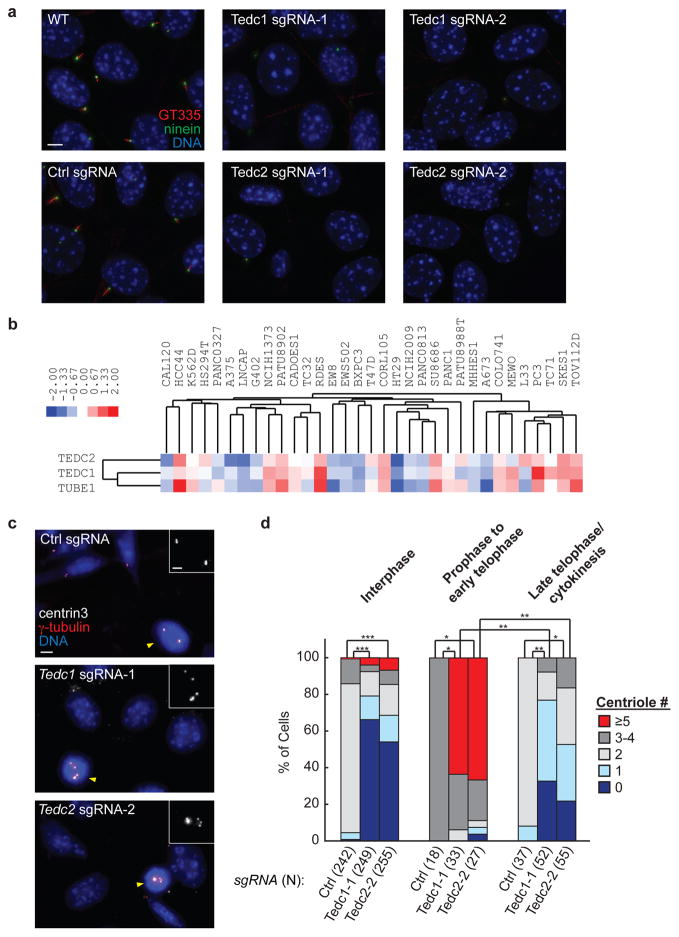

To functionally characterize Tedc1 and Tedc2, we examined mutant cell pools and found that they were almost completely devoid of centrioles, as assessed by staining with antibodies to centrin, ninein, polyglutamylated tubulin or γ-tubulin (Fig. 7a,c,d). Mutant cells also lacked cilia (Fig. 7a) and had strong defects in Hh signaling (Supplementary Fig. 6c,d). Notably, centrioles and cilia were restored in Tedc1 mutant cells following introduction of sgRNA-resistant TEDC1-Flag (Supplementary Fig. 6e,f), which also localized to centrioles (Supplementary Fig. 6g).

a) Cells transduced with the indicated sgRNAs were stained with antibodies to ninein (centrioles) and polyglutamylated tubulin (GT335, centrioles and cilia). Scale bar: 5 μm. One of three representative experiments. b) Hierarchical clustering of relative growth scores across the indicated cell lines reveals that TEDC1, TEDC2, and TUBE1 share a similar pattern of relative fitness. Blue and red shading indicates decreased and increased proliferation relative to the average behavior across all cell lines. c) For cells transduced with the indicated sgRNAs, centrioles were visualized by staining with antibodies to centrin3 and γ-tubulin. Insets show centrin3 staining in mitotic cells, marked by yellow arrowheads. Scale bars: 5 μm (2 μm for insets). See also Supplementary Fig. 6h. One of three representative experiments. d) Centrioles marked by centrin3 and γ-tubulin were counted in cells at the indicated cell cycle stages. Statistically significant differences in centriole counts are shown for select conditions (*, P < 1×10−6; **, P < 1×10−10; ***, P < 1×10−60, determined by two-sided Fisher’s exact test).

We noted that Tedc1 and Tedc2 mutants exhibited a mild growth defect (Supplementary Table 3), which is consistent with recent evidence that NIH-3T3 cells lacking centrioles proliferate at a reduced rate73. By contrast, in other cell types, a p53-dependent arrest prevents growth in the absence of centrioles. These observations prompted us to investigate whether the varying effects of Tedc1 or Tedc2 on proliferation across different cell types could enable predictive identification of genes with similar function. We therefore examined a collection of CRISPR-based growth screens conducted in 33 different human cell lines and used hierarchical clustering to group genes based on their cell type-specific growth phenotypes74. Strikingly, this unbiased approach placed TEDC1, TEDC2, and TUBE1 in a single cluster (Fig. 7b and Supplementary Table 7), suggesting that they share a highly similar function. While TUBD1 was not found in this cluster, this result is likely due to ineffective targeting of TUBD1 by the sgRNA library used. Indeed, while other CRISPR screens have reported pronounced growth defects for TUBD1 mutants18,25, this study did not.74.

To better understand the basis for centriole loss in Tedc1 and Tedc2 mutants, we examined cells at different stages of the cell cycle. Surprisingly, while mutant cells typically had zero or one centriole in interphase, nearly all mitotic cells had excess centrioles (more than four), suggestive of de novo centriole formation before mitotic entry (Fig. 7c,d and Supplementary Fig. 6h). By contrast, cells exiting mitosis showed significantly fewer centrioles than control cells (Fig. 7d). Taken together, these observations suggest that Tedc1 and Tedc2 are dispensable for centriole biogenesis but required for centriole stability, with newly generated centrioles rapidly lost as cells exit mitosis. In further support of a shared function for TED complex components, TUBE1- and TUBD1-deficient human cells were recently shown to have a similar phenotype75.

Discussion

Here we present a functional screening platform that pairs a pathway-specific selectable reporter with genome-wide CRISPR-based gene disruption. Applying these technologies to cilium-dependent Hh signaling, we obtain a comprehensive portrait of cilium biology that identifies hit genes with high sensitivity and specificity. Several factors likely contributed to the quality of our screen, including the pooled screening format, the use of CRISPR for gene disruption, and a newly designed sgRNA library (see Supplementary Note). Furthermore, our use of a selectable pathway reporter makes this technology applicable to virtually any process with a well-defined transcriptional response.

Our pooled CRISPR-based screening approach enabled us to generate a rich dataset that will be a valuable resource for dissecting ciliary signaling, defining ciliopathy genes, and discovering potential therapeutic targets in Hh-driven cancers. While siRNA-based screens have contributed to our understanding of cilia and Hh signaling, these datasets suffer from false positives or false negatives that limit their utility. Roosing et al.8 improved their ciliogenesis screen results by using reference gene sets to help classify hits and by integrating gene expression datasets with their microscopy-based screen data. Our approach achieved high performance without dependence on other data sources, which may not always be available, or on a priori definition of hits, which could bias discovery of new hit classes. Our screens are also highly reproducible, thereby enabling comparative screening approaches that will be instrumental in uncovering novel factors acting at specific steps in Hh signaling. Modifications to our screening strategy, such as performing screens in other cell lines or in unstimulated (or weakly stimulated) cells, may better replicate certain in vivo signaling modalities and may have improved sensitivity for identifying negative regulators of Hh signaling.

The value of our screen is demonstrated by the discovery of new genes that participate in ciliary signaling and new candidate ciliopathy genes. While the precise roles of FAM92A at the transition zone and TTC23 at the EvC zone will require further study, our screen demonstrates that new components remain to be identified even for well-studied ciliary structures. Similarly, our analyses of TXNDC15, ARMC9, CWC27, DPH1, INTS6, INTS10, ANKRD11, CDK13, CHD4, FOXP1, PRKD1, and KTM2D illustrate that screen hits can help to identify a ciliopathy-causing gene from a short list of variants, as is frequently the case in studies involving small pedigrees, and to classify new genetic syndromes as disorders of ciliary signaling. With the exception of TXNDC15, all of the aforementioned genes had been previously linked to disease without a potential role for cilia described (e.g. KMT2D and Kabuki Syndrome, OMIM 147920; ANKRD11 and KBG Syndrome, OMIM 148050; DPH1 and Loucks-Innes Syndrome, OMIM 616901). Among the syndromes caused by mutations in these genes, it is striking that the most prevalent feature is CHD. Our screen thus provides unbiased evidence that several CHD cases are ciliopathies, building upon similar connections observed in mice76 and motivating future investigations by human geneticists and developmental biologists.

By contrast, it is noteworthy that few of the ciliopathy genes primarily linked to kidney pathology were found as screen hits, suggesting that these renal diseases are mechanistically distinct (see Supplementary Note). By capturing an unbiased picture of cilium-based signaling, our screen refines the classification of ciliopathies. More broadly, as genome sequencing reveals disease-associated variants at ever-growing rates, genome-wide functional studies such as that presented here will become a powerful resource to distinguish disease-causing mutations from innocuous variants77 and to gain insight into underlying disease mechanisms.

Our screen identifies hit genes with diverse roles in cilium function, Hh signaling, and centriole biology. For hits Tedc1, Tedc2, Tubd1, and Tube1, we found that these genes act in concert to ensure centriole stability, as evidenced by the association of their gene products in a stoichiometric complex. This finding reveals a new direct link between ε- and δ-tubulin and raises the possibility that they may form a heterodimer analogous to α/β-tubulin. In addition to the physical association of TED complex components, deficiency for TED complex-encoding genes produces a remarkably similar pattern of growth phenotypes across cell lines. Moreover, we find that these genes exhibit a similar phylogenetic distribution (see Supplementary Table 8, Supplementary Fig. 7, and Supplementary Note). Together, these observations provide further evidence for a shared function and illustrate the precise functional predictions made possible by CRISPR-based growth profiling18.

Studies in Paramecium, Tetrahymena, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, and, most recently, human cells have shown that disrupting δ- or ε-tubulin leads to loss of the C and/or B tubules of the centriolar triplet microtubules64,66,67,78. We propose that the centrioles formed in Tedc1/2-deficient cells similarly lack triplet microtubules, causing them to degenerate during mitotic exit at the time when pericentriolar material (PCM) is stripped from the centrosome. Since removal of the PCM causes centriolar instability in fly spermatocytes79, post-mitotic PCM removal may also trigger centriole loss in Tedc1/2 mutants. CENPJ may act together with the TED complex to ensure centriole stability, as CENPJ was found in our TEDC2 purifications and a mutation in Cenpj disrupts triplet microtubules in Drosophila spermatocytes80. As CENPJ is a microcephaly gene81,82, TED complex components are potential candidate genes for this neurodevelopmental disorder.

In summary, we have developed a functional screening platform that provides a resource for investigating long-standing questions in Hh signaling and primary cilia biology. By further applying these tools, it may now be possible to systematically define vulnerabilities in Hh pathway-driven cancers, to identify modifiers of Hh pathway-inhibiting chemotherapeutics, and to search for suppressors of ciliopathies that may inform treatment. Integrating this functional genomic approach with complementary insights from proteomics and human genetics promises a rich toolkit for understanding ciliary signaling in health and disease.

Online Methods

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to David Breslow ([email protected]).

EXPERIMENTAL MODELS AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Cell lines and cell culture

NIH-3T3 and HEK293T cells were grown in high glucose, pyruvate-supplemented DMEM (Gibco) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM glutamine, 10 U/ml penicillin and 10 μg/ml streptomycin (Gemini Bio-Products). NIH-3T3 FlpIn cells (gift from R. Rohatgi) were grown in the same medium supplemented with non-essential amino acids (Gibco). Light-II NIH-3T3 cells24 were grown in the same medium except with 10% bovine calf serum (ATCC), and IMCD3 cells were grown in DMEM/F12 medium (Gibco) with FBS, glutamine, penicillin and streptomycin additives. Serum starvation was done using medium with 0.5% FBS for NIH-3T3 cells, 0.5% calf serum for Light-II NIH-3T3 cells, and 0.2% FBS for IMCD3 cells. IMCD3 FlpIn cells were provided by Peter Jackson. NIH-3T3 cells were obtained from ATCC. HEK239T-EcR-ShhN cells were provided by Philip Beachy. Cells were confirmed to be mycoplasma free with the MycoAlert system (Lonza).

METHOD DETAILS

DNA cloning

Individual sgRNAs were cloned by ligating annealed oligonucleotides into pMCB306 or pMCB320 digested with BstXI and Bpu1102I (Fermentas FastDigest enzymes, Thermo Fisher). Ligated products were transformed into Mach1-T1 competent cells (Thermo Fisher), and recovered plasmids were verified by sequencing.

Cilia-focused sgRNA libraries were cloned from oligonucleotide pools (Agilent) as described25. Briefly, oligonucleotides were amplified using primer sequences common to each sub-library, digested with BstXI and Bpu1102I, ligated into pMCB320, and transformed into Endura competent cells (Lucigen). DNA was isolated using a Plasmid Plus Giga kit (Qiagen).

Individual cDNAs were amplified from mouse cDNA or commercially available sources (Dharmacon) and cloned into Gateway Entry vectors via BP clonase-mediated recombination (Thermo Fisher) or using isothermal assembly. Mutations to introduce resistance to sgRNA-directed cleavage were introduced by isothermal assembly. Plasmids for expression of tagged genes of interest were generated from Entry vectors by LR clonase-mediated recombination (Thermo Fisher) into Destination vectors encoding C-terminal LAP, 3xFLAG, or 6xMyc tags.

Plasmid pHR-Pgk-Cas9-BFP was cloned by digestion of pHR-SFFV-Cas9-BFP (M. Bassik) and replacement of the SFFV promoter with the Pgk promoter amplified from pEFB/FRT-pCrys-APGpr161NG3-NsiI-pPgk-BirA-ER46. Plasmid pGL-8xGli-Bsd-T2A-GFP-Hyg was generated in the pGL4.29-[luc2P/CRE/Hygro] vector (Promega) by replacement of the CRE response element with 8xGli binding sites amplified from pGL3-8xGli-Luc (P. Beachy) and of Luc2P with Bsd-T2A-GFP amplified from pEF5B-FRT-DEST-LAP83.

Virus production and cell transduction

VSVG-pseudotyped lentiviral particles were produced by co-transfection of HEK293T cells with a lentiviral vector and appropriate packaging plasmids (pMD2.G, pRSV-Rev, pMDLg/RRE for sgRNAs expressed in pMCB320 or pMCB306; pCMV-ΔR-8.91 and pCMV-VSVG for Pgk-Cas9-BFP). Following transfection using polyethyleneimine (linear, MW~25000, Polysciences), virus-containing supernatant was collected 24 h later and filtered through a 0.45 μm cellulose acetate filter. For sgRNA libraries, a second harvest of viral medium was performed 24 h after the initial harvest. For Cas9-containing virus, lentiviral particles were concentrated 20-fold using Lenti-X Concentrator (Clontech).

Cells were transduced by addition of viral supernatants diluted to an appropriate titer in growth medium containing 4 μg/ml polybrene (Sigma Aldrich). Following 24 h incubation at 37°C, virus-containing medium was removed; after an additional 24 h, cells were passaged and, where appropriate, selection for transduced cells was commenced by addition of 2.0 μg/ml puromycin (Invivogen). Multiplicity of infection was determined by flow cytometry.

ShhN production and titering

ShhN-containing conditioned medium was produced in HEK239T-EcR-ShhN cells. Cells were grown to 80% confluence, medium changed to DMEM with 2% FBS, followed by collection of conditioned medium after 48 h and filtration through a 0.22 μm filter (EMD Millipore). The titer of ShhN was determined using NIH-3T3 Light-II reporter cells (see Luciferase reporter assays), and a concentration approximately two-fold greater than the minimum dilution needed for full induction was used for further experiments (typically 1:12.5).

Flow cytometry and fluorescence-activated cell sorting

Flow cytometry analyses were conducted using a FACSScan (Becton Dickinson) outfitted with lasers provided by Cytek Biosciences. FACS was performed using FACSAria II cell sorters (Becton Dickinson). Flow cytometry and FACS data were analyzed using Flowjo (Treestar).

Generation of stable cell lines

The 3T3-[Shh-BlastR;Cas9] reporter cell line was generated using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher) to transfect NIH-3T3 cells with pGL-8xGli-Bsd-T2A-GFP-Hyg. Following selection for hygromycin-resistant cells, clonal isolates were obtained by limiting dilution and tested for SAG-induced blastidicin resistance. Pgk-Cas9-BFP was introduced lentivirally, followed by three rounds of FACS sorting for high-level BFP expression.

Stable cell lines for affinity purification and localization studies were generated using the FlpIn system (Life Technologies) with IMCD3 FlpIn or NIH-3T3 FlpIn cells. Plasmids encoding genes of interest in the pEF5B/FRT-DEST-LAP (or 3xFLAG) vector were transfected into FlpIn cells together with pOG44 Flp recombinase (Life Technologies) using X-tremegene 9 (Roche). Recombined cell pools were obtained following selection with blasticidin (Sigma Aldrich).

Rescue of Tedc1 mutant cells was performed by lentiviral transduction with a construct expressing sgRNA-resistant mouse TEDC1-3xFlag-T2A-GFP. This construct was expressed from the Pgk promoter, and cells were analyzed 7–14 days post-transduction.

Blasticidin reporter assays

3T3-[Shh-BlastR;Cas9] cells were seeded for signaling and grown to near confluence. Growth medium was replaced with serum starvation medium with or without pathway agonist (ShhN conditioned medium or 250 nM SAG, synthesized as described84,85). After 24 h, cells were passaged at ~1:6 dilution into medium with 10% FBS, and 5 h later subjected to selection with blasticidin (blasticidin S hydrochloride, Sigma Aldrich) for 4 d. Relative viability was determined using the CellTiter-Blue assay (Promega) using a SpectraMax Paradigm (Molecular Devices) or Infinite M1000 (Tecan) plate reader.

Genome-wide screening

Due to the large number of cells required, we conducted the screen in four batches using subsets of the library containing ~45,000–70,000 sgRNAs (Supplementary Fig. 2a)25. For each batch, lentivirus was produced and titered as described above. 3T3-[Shh-BlastR;Cas9] cells were grown in 15 cm plates and transduced at a multiplicity of infection of ~0.3 in sufficient numbers such that there was a ~500:1 ratio of transduced cells to sgRNA library elements. Cells were selected with puromycin for 5 d, grown for 3 d without puromycin, and then plated for signaling, maintaining a ~1,000:1 ratio of cells to sgRNAs for these and all subsequent steps. After cells reached confluence, signaling was initiated by addition of serum starvation medium containing ShhN. After 24 h, cells were passaged, allowed to adhere, and then subjected to blasticidin selection for 4 d at 5 μg/ml, a concentration we found sufficient to achieve strong enrichment/depletion of hits without causing sgRNA library bottlenecks due to excess cell death. After passaging cells to blasticidin-free medium, a ‘T1’ sample was harvested (1000-fold more cells than sgRNAs) and remaining cells were passaged once more before seeding for a second round of signaling and selection. The final ‘T2’ cell sample was collected following 4 d blasticidin selection and one additional passage in the absence of blasticidin. Unselected control cells were also propagated through the entire experiment and harvested at equivalent timepoints.

Screens using the cilia/Hh pathway-focused library were conducted as above except that a variant blasticidin reporter cell line was used in which Cas9-BFP was expressed using the shortened EF1α promoter. Because some Cas9-negative cells accumulated during the experiment, the final blasticidin-selected and unselected cells were FACS-sorted for BFP expression.

To process cell samples for sgRNA sequencing, genomic DNA was isolated using QiaAmp DNA Blood Maxi or QiaAmp DNA mini kits (Qiagen). Genomic DNA was then amplified using Herculase II polymerase (Agilent) as described16, first using outer primers to amplify the sgRNA cassette, then inner primers to amplify a portion of the initial PCR product while introducing sample-specific barcodes and adapters for Illumina sequencing (Supplementary Table 9). Gel-purified PCR products were quantified with a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer using the dsDNA HS kit (Thermo Fisher) and pooled for sequencing. Deep sequencing was performed on a NextSeq 500 sequencer with high-output v2 kits (Illumina) to obtain ~500-fold excess of reads to sgRNA library elements. Sequencing was performed using a custom primer to read the sgRNA protospacer (see Supplementary Table 9).

Cas9-induced mutation analysis by sequencing

Genomic DNA from sgRNA-transduced cell pools was extracted using the QIAamp DNA Mini kit (Qiagen) and amplified using primers flanking the sgRNA target site (see Supplementary Table 1). Gel-purified PCR products were subjected to Sanger sequencing, and resulting chromatograms were analyzed using TIDE (Tracking of Indels by Sequence Decomposition)34.

Luciferase reporter assays

Luciferase reporter assays were conducted using 3T3-[Shh-BlastR;Cas9] cells co-transfected with pGL3-8xGli-Firefly-luciferase and pGL3-SV40-Renilla-luciferase. One day after plating, cells were transfected using Mirus TransIT-2020 (Mirus Bio) with luciferase plasmids and either control GFP-encoding plasmid (pEF5B-FRT-GFP-FKBP)86 or a plasmid encoding a gene of interest. Nearly confluent cells were switched to serum starvation medium with or without pathway agonist 24 h later, and allowed to signal for 24–30 h. Alternatively, luciferase assays for titering ShhN-conditioned medium were performed with the NIH-3T3 Light-II cell line, which has stably integrated versions of GLI-driven firefly luciferase and constitutively expressed Renilla luciferase. After signaling, cells were lysed in lysis buffer (12.5 mM Tris pH 7.4, 4% glycerol, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.5 mg/mL BSA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT) and a dual luciferase measurement performed using a Modulus microplate luminometer (Turner Biosystems).

Immunofluorescence and localization studies

IMCD3 FlpIn or 3T3-[Shh-BlastR;Cas9] cells were plated on acid-washed 13mm round #1.5 coverslips (additionally coated with poly-L-lysine for NIH-3T3 cells). After 24 h, cells were transfected as needed with siRNAs (Supplementary Table 9) using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Thermo Fisher) or with plasmids using Fugene 6 (Promega). Where indicated, cells were serum starved for 24 h and treated with ShhN or 1 μM vismodegib (Chemietek) before fixation using 4% paraformaldehyde, ice-cold methanol, or both in succession. For GLI2/GLI3/SMO trafficking assays, cells were serum-starved for 20 h, followed by 5–6 h incubation in the presence or absence of ShhN-conditioned medium. For analysis of TEDC2-LAP localization, cells were pre-extracted prior to methanol fixation via a one-minute exposure to PHEM buffer (60 mM PIPES, 25 mM HEPES, 4 mM MgSO4, 10 mM EGTA, pH 7.0) with 0.2% TritonX-100.

Fixed coverslips were blocked using PBS with 3% BSA and 5% normal donkey serum, permeabilized using PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100, and then incubated with appropriate primary and secondary antibodies (Supplementary Table 10). Coverslips were either stained with Hoechst DNA dye and mounted on slides using Fluoromount-G mounting medium (Electron Microscopy Sciences) or directly mounted using ProLong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Life Technologies).

Coverslips were imaged at 60x or 63x magnification using one of the following microscope systems: an Axio Imager.M1 (Carl Zeiss) equipped with SlideBook software, an LED light source (Intelligent Imaging Innovations) and a Prime 95b sCMOS camera (Photometrics); an Axio Imager.M1 (Carl Zeiss) equipped with SlideBook software, a Lambda XL light source (Sutter instruments) and CoolSNAP HQ2 CCD camera (Photometrics); an Axio Imager.M2 equipped with ZEN software, an X-Cite 120 LED light source (Excelitas) and an Axiocam 503 mono camera (Carl Zeiss); or a DeltaVision Elite imaging system equipped with SoftWoRx software, an LED light source, and sCMOS camera (Applied Precision). Z-stacks were acquired at 250–500 nm intervals and deconvolved as needed using Slidebook 6.0 or SoftWoRx softwares.

Co-transfection and co-immunoprecipitation

HEK293T cells were co-transfected with Tedc1, Tedc2 or TagRFP plasmids using Fugene 6, collected after 48 h, and lysed on ice in CoIP buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1X DTT, 1X LPB) supplemented with protease inhibitors. Lysates were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 20 min, and FLAG-tagged proteins were captured by incubation for 2 h with anti-FLAG M2 antibody (Sigma Aldrich) and Protein G Sepharose 4 Fast Flow (GE Healthcare). After four washes of resin with CoIP buffer, bound proteins were eluted by incubation at 95°C in lithium dodecyl sulfate-based gel loading buffer.

Western blotting

Lysates from 3T3-[Shh-BlastR;Cas9] cells were prepared in SDS sample buffer (50 mM Tris HCl pH 6.8, 8% v/v glycerol, 2% w/v SDS, 100 mM DTT, 0.1 mg/mL bromophenol blue), boiled and sonicated. Samples were loaded onto a 4–15% Criterion TGX Stainfree gel (Bio-Rad), and run for 25 min, 300V in Tris/Glycine/SDS buffer (Bio-Rad), before being transferred onto a PVDF membrane using a Transblot Turbo system (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked in 1:1 PBS:SeaBlock (Thermo Scientific) for 1 h at room temperature, and subsequently incubated with the indicated primary antibody for 16 h at 4 °C (Supplementary Table 10). After incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody, blots were developed using Supersignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo Fisher) and imaged on a ChemiDoc MP (Bio-Rad). Membranes were stripped using Restore Western Blot stripping buffer (Thermo-Fisher) and re-probed as described.

For analysis of immunoprecipitations, Western blotting was performed as described above, except samples were separated in 4–12% Bis-Tris PAGE gels (Invitrogen) using MOPS running buffer, transferred to PVDF membranes using the Criterion Blotter system (Bio-Rad), developed using ECL or ECL 2 chemiluminescence detection kits (Pierce), and imaged on a Chemidoc Touch system (Bio-Rad).

Large-scale affinity purification and mass spectrometry

Affinity purifications were conducted as described83. Briefly, ~500–1000 μl packed cell volume was lysed in LAP purification buffer containing 0.3% NP-40. Lysate was cleared sequentially at 16,000 × g and 100,000 × g before incubation with anti-GFP antibody coupled to Protein A resin. After protein capture and washes, bound LAP-tagged proteins were eluted by incubation with HRV3C protease. For mass spectrometry analysis ‘A’ (see Supplementary Table 6), eluted proteins were further purified by capture on S-Protein agarose followed by elution at 95°C in lithium dodecyl sulfate-based gel loading buffer.

For protein analysis by mass spectrometry, gel slices containing affinity-purified proteins were washed with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, followed by reduction with DTT (5 mM) and alkylation using propionamide (10 mM). Gel slices were further washed with an acetonitrile-ammonium bicarbonate buffer until all stain was removed. 120 ng of Trypsin/LysC (Promega) reconstituted in 0.1% ProteaseMAX (Promega) with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate was added to each gel band; after 30 min., 20 μL of additional 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate in 0.1% ProteaseMAX was added. Digestion was then allowed to occur overnight at 37 °C. Peptides were extracted from the gels in duplicate followed by drying using a SpeedVac concentrator. Peptide pools were then reconstituted and injected onto a C18 reversed phase analytical column, ~20 cm in length, pulled and packed in-house. The UPLC was a NanoAcquity or M-Class column (Waters), operated at 450 nL/min using a linear gradient from 4% mobile phase B to 45% B. Mobile phase A consisted of 0.2% formic acid, water; mobile phase B was 0.2% acetic acid, acetonitrile. The mass spectrometer was an Orbitrap Elite or Fusion (Thermo Fisher) set to acquire in a data-dependent fashion selecting and fragmenting the 15 most intense precursor ions in the ion-trap, where the exclusion window was set at 45 seconds and multiple charge states of the same ion were allowed.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Analysis of CRISPR-based screens

CRISPR-based screens were analyzed as described26, processing data from each screen batch separately. To determine sgRNA counts in each sample, raw sequencing reads were trimmed to the 3′-most 17 nt of each protospacer and aligned to expected sgRNA sequences. This alignment was carried out with the makeCounts script of the casTLE software package26, which uses Bowtie87 to perform alignment with zero mismatches tolerated. The analyzeCounts script (v0.7 and v1.0) of casTLE was then used to identify genes exhibiting significant enrichment or depletion and to estimate the phenotypic effect size for each gene. This method uses an empirical Bayesian approach to score genes according to the log-likelihood ratio that a gene’s observed changes in sgRNA counts is drawn from a model of gene effect versus the distribution of negative control sgRNAs. An expected negative score distribution is obtained by random permutation of gene-targeting sgRNA fold-change values and used to determine a P value for each gene. Note that the use of 100,000 permutations leads to a minimum reported P value of 1 × 10−5 (200,000 permutations were used for comparative screening in Supplementary Fig. 3c, with minimum P value of 5 × 10−6). For each gene, the casTLE algorithm also estimates the magnitude of the phenotype resulting from complete gene inactivation. This value is output as the effect size and is accompanied by an estimated range of effect sizes compatible with each gene’s sgRNA data.

Genes targeted by our sgRNA library that lacked an NCBI identifier or that severely affected growth (casTLE effect size ≤ −2.5 and casTLE P value < 0.005) were not considered for further analysis but are included in Supplementary Table 3. Negative and positive reference genes were defined for growth and signaling phenotypes using previously defined gene sets (Supplementary Table 3)8,27. Precision-recall and ROC curves were computed in Matlab (Mathworks). Hit genes at 10% and 20% false discovery rate cutoffs were defined using the precision-recall threshold values at precision of 0.9 and 0.8, yielding P value cutoffs of 0.0163 and 0.0338, respectively. Ciliopathy-associated genes were defined from OMIM. Functional category enrichment analysis for 10% FDR hits was performed using the DAVID website’s Functional Annotation Chart tool using all mouse genes as the background28. A second analysis was performed using human homologs of 10% FDR hits using all human genes as the background. Significance of overlap between the top 15 congenital heart defect genes reported by Sifrim et al.50 and P values from functional screening was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

Quantification of Hh signaling assays

Blasticidin-based inhibition of cell growth was determined by normalizing raw CellTiter-Blue fluorescence such that growth in the absence of blasticidin corresponds to 100% growth. The IC50 for blasticidin was determined using Prism 7.0 (Graphpad Software).

Dual-luciferase data were analyzed by first subtracting background signal such that cells without luciferase give readings of zero. Firefly to Renilla (8x-Gli to constitutive) ratios were then calculated and normalized such that unstimulated control cells have a value equal to 1.

Quantification of fluorescence microscopy images

Microscopy images were analyzed using Fiji ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health) and a custom Matlab (Mathworks) script. Local background subtraction was performed on all images before analysis. To determine ciliary frequency, cells were manually scored for the presence or absence of a cilium using ARL13B and acetylated tubulin as ciliary markers. For analyses of ciliary length and intensity of ciliary markers, the ARL13B and/or acetylated tubulin channels were used to create a ciliary mask. The ciliary mask was then used to determine cilium length and measure ciliary signal in other channels. The γ-tubulin or ninein signal (staining centrioles) was used to orient cilia from base to tip. Tip fluorescence for GLI2 and GLI3 was defined as the summed fluorescence in the distal-most five pixels of each cilium. For ARMC9-FLAG localization, the ciliary fluorescence of each cilium was normalized to 1, and each axoneme was divided in 20 equal-distance bins.

Differences in cilium length distribution were tested for significance using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test in Matlab. Line plots of fluorescence intensity along cilia were generated in ImageJ.

Centriole counting measurements were done manually using γ-tubulin and centrin3 staining to guide centriole calling. Cell cycle stage was determined using DNA morphology, and statistical significance was determined using Fisher’s exact test. Cell counts for each of the five centriole number categories were used for statistical comparisons between genotypes.

Analysis of mass spectrometry data

MS/MS data were analyzed using both Preview and Byonic v2.10.5 (ProteinMetrics). All data were first analyzed in Preview to provide recalibration criteria if necessary and then reformatted to MGF format before full analysis with Byonic. Data were searched at 12 ppm mass tolerances for precursors, with 0.4 Da fragment mass tolerances assuming up to two missed cleavages and allowing for fully specific and ragged tryptic peptides. The database used was Uniprot for Mus musculus downloaded on 10/25/2016. These data were validated at a 1% false discovery rate using typical reverse-decoy techniques88. The resulting identified peptide spectral matches and assigned proteins were then exported for further analysis using MatLab (MathWorks) to provide visualization and statistical characterization.

Analysis of CRISPR growth screen datasets

Gene-level growth phenotype data74 were downloaded from the Achilles website. Hierarchical clustering using uncentered correlation and average linkage settings was performed using Cluster 3.0 software89, and clustered data were visualized in Java Treeview90.

Phylogenetic analysis

Homologs for Tubd1 and Tube1 were either previously described 91 or identified using protein BLAST. Homologs for Tedc1 and Tedc2 were identified using iterative searches with PSI-BLAST92. To analyze sequence divergence, homolog sequences were first aligned using Clustal Omega93. Phylogenetic trees were generated via neighbor joining with distance correction using Simple Phylogeny 93 and visualized using Unrooted94.

Statistical analysis of centriole number

Tests of statistical significance for differences in centriole number between conditions were calculated by two-sided Fisher’s exact test using Stata 14.2 (StataCorp).

CODE AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Software used for casTLE analysis can be found at http://bitbucket.org/dmorgens/castle. Matlab scripts for quantification of cilium intensities and length are available upon request.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files, with the exception of raw Illumina sequencing data and sequencing-based analysis of CRISPR-induced mutations, which are available upon request.

Supplementary Material

1

2

3

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge members of the Chen and Nachury labs for advice and technical support; S. van Dorp for assistance with image quantification; P. Beachy (Stanford) for NIH-3T3 cells, 8xGli-luciferase reporter plasmid, and ShhN-producing HEK293T cells; K. Anderson (Sloan Kettering) for SMO antibody; G. Crabtree, K.C. Garcia, and A. Pyle for use of plate readers; N. Dimitrova for microscope use; C. Bustamante for use of an Illumina sequencer; R. Rohatgi (Stanford) for antibodies to EVC and IQCE; J. Wang and T. Stearns (Stanford) for sharing unpublished results and cDNA for Cby1; and M. Scott for helpful discussions. This project was supported by NIH Pathway to Independence Award K99/R00 HD082280 (D.K.B), Damon Runyon Dale F. Frey Award DFS-11-14 (D.K.B.), a seed grant from the Stanford Center for Systems Biology (D.K.B., S.H. and G.T.H.) and Stanford ChEM-H (M.C.B.), an NWO Rubicon Postdoctoral Fellowship (S.H.), National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship DGE-114747 (D.W.M.), a Walter V. and Idun Berry Award (K.H.), T32 HG000044 (G.T.H.), DP2 HD08406901 (M.C.B.), R01 GM113100 (J.K.C.), and R01 GM089933 (M.V.N.). Cell sorting/flow cytometry was done on instruments in the Stanford Shared FACS Facility, including an instrument supported by NIH shared instrument grant S10RR025518-01. Mass spectrometry analyses were conducted in the Vincent Coates Foundation Mass Spectrometry Laboratory, Stanford University Mass Spectrometry and the Stanford Cancer Institute Proteomics/Mass Spectrometry Shared Resource; these centers are supported by Award S10 RR027425 from the National Center for Research Resources and NIH P30 CA124435, respectively. We thank Carsten Carstens, Ben Borgo, Peter Sheffield, and Laurakay Bruhn of Agilent Technologies for cilia-focused oligonucleotide sub-libraries.

Footnotes

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions

D.K.B., S.H., J.K.C., and M.V.N. conceived the project with advice from M.C.B. D.K.B. and S.H. developed the Hh pathway reporter screening strategy with assistance from B.K.V. D.W.M., K.H., A. L., G.T.H, and M.C.B. provided functional genomics expertise, the genome-wide sgRNA library, and software for screen data analysis. D.K.B. conducted the genome-wide screen and screen data analysis with assistance from S.H. and A.R.K. D.K.B., S.H., A.R.K., and M.C.K. functionally characterized hit genes of interest, analyzed data, and prepared figures. D.K.B., S.H., J.K.C., and M.V.N. wrote the manuscript with assistance from M.C.B. D.K.B, S.H., G.T.H., M.C.B, J.K.C. and M.V.N. provided funding for the project.References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0054-7

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc5862771?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1038/s41588-018-0054-7

Article citations

A prioritization tool for cilia-associated genes and their in vivo resources unveils new avenues for ciliopathy research.

Dis Model Mech, 17(10):dmm052000, 14 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39263856 | PMCID: PMC11512102

The Proteasome and Cul3-Dependent Protein Ubiquitination Is Required for Gli Protein-Mediated Activation of Gene Expression in the Hedgehog Pathway.

Cells, 13(17):1496, 06 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39273066 | PMCID: PMC11394618

Exploring the structural landscape of DNA maintenance proteins.

Nat Commun, 15(1):7748, 05 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39237506 | PMCID: PMC11377751

A disease-associated PPP2R3C-MAP3K1 phospho-regulatory module controls centrosome function.

Curr Biol, 34(20):4824-4834.e6, 23 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39317195

The genomes of all lungfish inform on genome expansion and tetrapod evolution.

Nature, 634(8032):96-103, 14 Aug 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 39143221 | PMCID: PMC11514621

Go to all (100) article citations

Other citations

Wikipedia

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Diseases (3)

- (1 citation) OMIM - 148050

- (1 citation) OMIM - 147920

- (1 citation) OMIM - 616901

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

CRISPR Screens Uncover Genes that Regulate Target Cell Sensitivity to the Morphogen Sonic Hedgehog.

Dev Cell, 44(1):113-129.e8, 28 Dec 2017

Cited by: 58 articles | PMID: 29290584 | PMCID: PMC5792066

Is ciliary Hedgehog signalling dispensable in the kidneys?

Nat Rev Nephrol, 14(7):415-416, 01 Jul 2018

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 29700487

Cilia, ciliopathies and hedgehog-related forebrain developmental disorders.

Neurobiol Dis, 150:105236, 28 Dec 2020

Cited by: 43 articles | PMID: 33383187

Review

Supernumerary centrosomes nucleate extra cilia and compromise primary cilium signaling.

Curr Biol, 22(17):1628-1634, 26 Jul 2012

Cited by: 77 articles | PMID: 22840514 | PMCID: PMC4094149

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NCI NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: P30 CA124435

NCRR NIH HHS (3)

Grant ID: S10 RR025518

Grant ID: S10 RR022448

Grant ID: S10 RR027425

NHGRI NIH HHS (2)

Grant ID: T32 HG000044

Grant ID: K22 HG000044

NICHD NIH HHS (2)

Grant ID: K99 HD082280

Grant ID: R00 HD082280

NIGMS NIH HHS (3)

Grant ID: R01 GM089933

Grant ID: P50 GM107615

Grant ID: R01 GM113100