Abstract

Free full text

Ketogenic diet enhances neurovascular function with altered gut microbiome in young healthy mice

Abstract

Neurovascular integrity, including cerebral blood flow (CBF) and blood-brain barrier (BBB) function, plays a major role in determining cognitive capability. Recent studies suggest that neurovascular integrity could be regulated by the gut microbiome. The purpose of the study was to identify if ketogenic diet (KD) intervention would alter gut microbiome and enhance neurovascular functions, and thus reduce risk for neurodegeneration in young healthy mice (12–14 weeks old). Here we show that with 16 weeks of KD, mice had significant increases in CBF and P-glycoprotein transports on BBB to facilitate clearance of amyloid-beta, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). These neurovascular enhancements were associated with reduced mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) and increased endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) protein expressions. KD also increased the relative abundance of putatively beneficial gut microbiota (Akkermansia muciniphila and Lactobacillus), and reduced that of putatively pro-inflammatory taxa (Desulfovibrio and Turicibacter). We also observed that KD reduced blood glucose levels and body weight, and increased blood ketone levels, which might be associated with gut microbiome alteration. Our findings suggest that KD intervention started in the early stage may enhance brain vascular function, increase beneficial gut microbiota, improve metabolic profile, and reduce risk for AD.

Introduction

Neurovascular functions play a critical role in determining cognitive capability and mental health1. Studies have shown that neurovascular risk is highly associated with accelerated decline in language ability, verbal memory, attention and visuospatial abilities2,3. Specifically, reduced cerebral blood flow (CBF) is linked to increased risk for anxiety, depression, and dementia3–5, while impaired blood-brain-barrier (BBB) function is associated with neuroinflammation, synaptic dysfunction, and psychiatric disorders6,7.

Emerging evidence suggests that gut microbiota play an important role in determining brain vascular integrity. Braniste et al. recently showed that BBB permeability is increased in germ-free mice due to lack of butyrate, a short chain fatty acid (SCFA) produced by microorganisms such as Clostridium tyrobutyricum8. Similarly, Akkermansia muciniphila can produce SCFAs such as acetate and propionate9, and the lack of A. muciniphila can alter the microbial ecology of the mucus layer10 and lead to damage of tight junctions of BBB and the gut7,11. BBB dysfunction further leads to reduced CBF and impaired clearance of amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease (AD)1,6. Interventions that maintain gut microbiome and neurovascular integrity may be thus crucial for impeding neurological disorders.

Ketogenic diet (KD), a high fat and low carbohydrate diet, has been an effective therapeutic for a wide range of neurological disorders12. Clinically, KD has been used to treat epilepsy12,13, Parkinson’s disease14, and autism15. Furthermore, significant evidence for KD as a therapeutic for a broader range of conditions can be found in preclinical studies where KD has been shown to protect brain function in Alzheimer’s disease16, traumatic brain injury17, and ischemic stroke18. A recent study showed that KD significantly increased regional CBF in a mouse model with ischemic stroke19. In another study with an autism mouse model, KD mitigated neurological symptoms potentially through changes in the gut microbiome20. Collectively, KD may be protective against various neurological disorders, possibly through the restoration of neurovascular function and by maintaining healthy gut microbiome.

While KD has beneficial effects in disease systems, it is unclear if similar impacts persist in healthy conditions. Therefore, the goal of the study was to identify whether administration of KD to young healthy mice would also benefit their neurovascular functions and gut microbiome composition, and whether these changes could contribute to lowering risk for AD, the most common form of dementia. We were also interested in identifying potential signaling pathways in association with vascular changes induced by KD. We hypothesized that KD would increase neuroprotection for young healthy mice, and reduce their risk for neurodegeneration, by enhancing their neurovascular functions and increasing the abundance of beneficial gut microbiota.

Results

Ketogenic diet enhances neurovascular functions

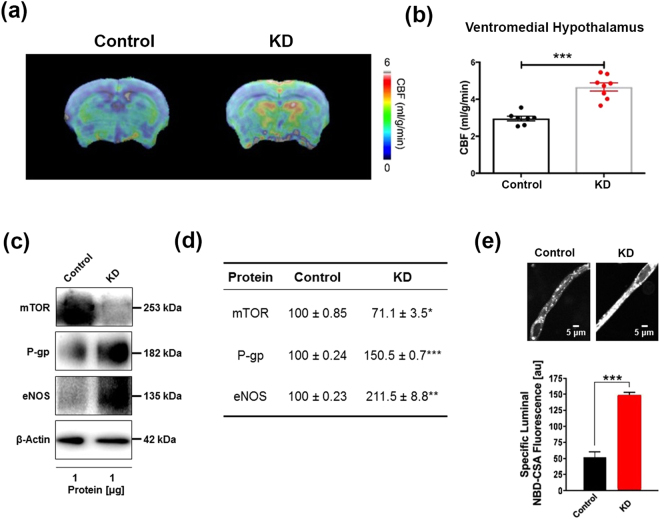

We used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to measure CBF and confocal microscopy to determine BBB function. Figure 1a shows representative CBF maps superimposed on structural brain images. The color code indicates the level of CBF in a linear scale. We found that KD-fed mice had significantly elevated CBF globally and regionally, particularly in ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) (11.82%; p <

< 0.0001; Fig. 1b). We previously reported that inhibiting mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling increases neurovascular function by activating endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS)21,22. In this study, we also found that mTOR protein expression was reduced (−29.9%; p

0.0001; Fig. 1b). We previously reported that inhibiting mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling increases neurovascular function by activating endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS)21,22. In this study, we also found that mTOR protein expression was reduced (−29.9%; p <

< 0.01) while eNOS levels were increased (111.5%; p

0.01) while eNOS levels were increased (111.5%; p <

< 0.001) in mice fed with KD, compared to control mice (Fig. 1c). In addition, protein expression levels of P-glycoprotein (P-gp), which transports Aβ across at the BBB, were also significantly elevated in KD-fed mice (50.5%; p

0.001) in mice fed with KD, compared to control mice (Fig. 1c). In addition, protein expression levels of P-glycoprotein (P-gp), which transports Aβ across at the BBB, were also significantly elevated in KD-fed mice (50.5%; p <

< 0.001). The Western blots are shown in Fig. 1c and the corresponding values are shown in Fig. 1d. We further used confocal microscope imaging to assess P-gp transport activity23. This assay measures accumulation of [N-ε(4-nitro-benzofurazan-7-yl)-DLys(8)]-cyclosporin A (NBD-CSA), a fluorescent P-gp substrate in the capillary lumen. Figure 1e (top) shows representative confocal images of capillaries incubated to steady state in a medium containing 2

0.001). The Western blots are shown in Fig. 1c and the corresponding values are shown in Fig. 1d. We further used confocal microscope imaging to assess P-gp transport activity23. This assay measures accumulation of [N-ε(4-nitro-benzofurazan-7-yl)-DLys(8)]-cyclosporin A (NBD-CSA), a fluorescent P-gp substrate in the capillary lumen. Figure 1e (top) shows representative confocal images of capillaries incubated to steady state in a medium containing 2 µM NBD-CSA; the intensity of fluorescence in the capillary lumen reflects the amount of NBD-CSA transported by P-gp. The corresponding quantitative results are shown in Fig. 1e (bottom) – KD mice had significantly enhanced P-gp transport activity (185.38%; p

µM NBD-CSA; the intensity of fluorescence in the capillary lumen reflects the amount of NBD-CSA transported by P-gp. The corresponding quantitative results are shown in Fig. 1e (bottom) – KD mice had significantly enhanced P-gp transport activity (185.38%; p <

< 0.001) in capillaries compared to capillaries isolated from control mice. Taken together, these results indicate that KD enhanced neurovascular function and increased Aβ clearance.

0.001) in capillaries compared to capillaries isolated from control mice. Taken together, these results indicate that KD enhanced neurovascular function and increased Aβ clearance.

Ketogenic diet enhances neurovascular functions. (a) Representative cerebral blood flow (CBF) maps superimposed on structural images; color code indicates level of CBF in a linear scale. KD mice exhibited significantly higher CBF in the (b) ventromedial hypothalamus. Data are presented as mean ±

± SEM, ***p

SEM, ***p <

< 0.001. (c) Western blot (WB) images for mTOR, P-gp, and eNOS from the cortical vasculature, β-Actin was used as loading control. (d) The corresponding values of the levels of protein expression. WB data from KD mice were normalized to β-Actin and compared to the control mice (100%), *p

0.001. (c) Western blot (WB) images for mTOR, P-gp, and eNOS from the cortical vasculature, β-Actin was used as loading control. (d) The corresponding values of the levels of protein expression. WB data from KD mice were normalized to β-Actin and compared to the control mice (100%), *p <

< 0.05, **p

0.05, **p <

< 0.01, ***p

0.01, ***p <

< 0.001. (e) Representative confocal images showing increased luminal accumulation of NBD-CSA fluorescence in brain capillaries isolated from KD mice compared to control mice, indicating higher P-gp transport activity. Corresponding quantitative fluorescence data; images are shown in arbitrary fluorescence units (scale 0–255). Data are mean

0.001. (e) Representative confocal images showing increased luminal accumulation of NBD-CSA fluorescence in brain capillaries isolated from KD mice compared to control mice, indicating higher P-gp transport activity. Corresponding quantitative fluorescence data; images are shown in arbitrary fluorescence units (scale 0–255). Data are mean ±

± SEM for 10 capillaries from one preparation of 10 mice per group, ***p

SEM for 10 capillaries from one preparation of 10 mice per group, ***p <

< 0.001. mTOR: mechanistic target of Rapamycin; P-gp: P-glycoprotein; eNOS; endothelial nitric oxide synthase.

0.001. mTOR: mechanistic target of Rapamycin; P-gp: P-glycoprotein; eNOS; endothelial nitric oxide synthase.

Ketogenic diet alters gut microbial diversity and increases beneficial microbiota

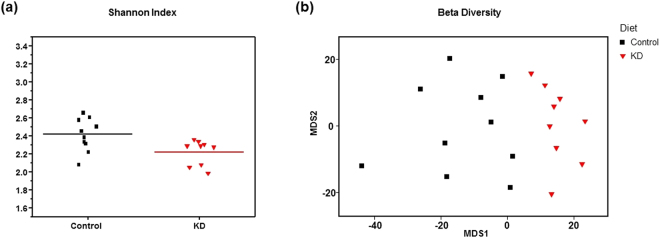

Figure 2a shows Shannon index (H) for alpha diversity, which is measure of within-sample diversity and is a synthesis of both the richness and evenness of the microbial community in a particular sample. Shannon indices calculated based on rarefied datasets (10,000 sequences/sample) were significantly different between control and KD mice (Mann-Whitney U test; p =

= 0.018), with the fecal microbiomes of KD mice having lower diversity. Figure 2b shows a genus-level metric multi-dimensional scaling (mMDS) plot of 16s rRNA gene amplicon microbiome data generated from a Bray-Curtis resemblance matrix. The fecal microbiomes of control and KD mice were significantly different as assessed by analysis of similarity (ANOSIM; R

0.018), with the fecal microbiomes of KD mice having lower diversity. Figure 2b shows a genus-level metric multi-dimensional scaling (mMDS) plot of 16s rRNA gene amplicon microbiome data generated from a Bray-Curtis resemblance matrix. The fecal microbiomes of control and KD mice were significantly different as assessed by analysis of similarity (ANOSIM; R =

= 0.473, p

0.473, p =

= 0.0002). These results indicate that KD significantly altered fecal microbial composition, and the effects included both a significant decrease in microbial diversity and a significant shift in microbial community composition.

0.0002). These results indicate that KD significantly altered fecal microbial composition, and the effects included both a significant decrease in microbial diversity and a significant shift in microbial community composition.

Ketogenic diet alters gut microbial diversity and increases pro-vascular microbiota. (a) Microbial diversity (Shannon index) was significantly higher in fecal samples from control relative to KD mice (Mann-Whitney U <

< 0.02). (b) Genus-level metric multi-dimensional scaling (mMDS) plot of 16S rRNA gene amplicon microbiome data was generated with a Bray-Curtis resemblance matrix. Fecal microbial communities of control and KD mice were significantly different in terms of individual taxa (ANOSIM R

0.02). (b) Genus-level metric multi-dimensional scaling (mMDS) plot of 16S rRNA gene amplicon microbiome data was generated with a Bray-Curtis resemblance matrix. Fecal microbial communities of control and KD mice were significantly different in terms of individual taxa (ANOSIM R =

= 0.473; p

0.473; p =

= 0.0002), as described in the text and Table 1. All samples were standardized and square root transformed. 2D stress

0.0002), as described in the text and Table 1. All samples were standardized and square root transformed. 2D stress =

= 0.16.

0.16.

We used a group significance test (Kruskal-Wallis test)24 to identify specific microbial taxa, which differed in relative abundance between fecal samples of KD and control mice. Table 1 shows the genera and species that were significantly different between control and KD mice (Kruskal-Wallis test, with Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate p <

< 0.05). We found that KD mice had significant increases in the relative abundance of A. muciniphila and Lactobacillus (approximately 2.5 and 3.2-fold increases, respectively). Both taxa have members that are capable of producing SCFAs25,26 and members of the genus Lactobacillus have been used elsewhere as probiotics27. Two low abundance genera of putative acetate producers (<0.3% relative abundance) within the order Clostridiales, Clostridium and Dorea28, were significantly lower in KD mice. The relative abundance of bacteria from the genera Desulfovibrio and Turicibacter was significantly and substantially lower in KD mice. Desulfovibrio sequences were not detected in KD mice but present at an average relative abundance of 0.53% in control animals, while Turicibacter relative abundance was nearly two orders of magnitude higher in the fecal samples of control mice relative to KD mice. Desulfovibrio are sulfate-reducing bacteria associated with inflammatory bowel disease29, while members of the genus Turicibacter were shown to increase with diet-induced obesity30. Collectively, KD increased the relative abundance of microbiota that are putatively able to protect neurovascular integrity, as well as reduced those which may induce inflammation.

0.05). We found that KD mice had significant increases in the relative abundance of A. muciniphila and Lactobacillus (approximately 2.5 and 3.2-fold increases, respectively). Both taxa have members that are capable of producing SCFAs25,26 and members of the genus Lactobacillus have been used elsewhere as probiotics27. Two low abundance genera of putative acetate producers (<0.3% relative abundance) within the order Clostridiales, Clostridium and Dorea28, were significantly lower in KD mice. The relative abundance of bacteria from the genera Desulfovibrio and Turicibacter was significantly and substantially lower in KD mice. Desulfovibrio sequences were not detected in KD mice but present at an average relative abundance of 0.53% in control animals, while Turicibacter relative abundance was nearly two orders of magnitude higher in the fecal samples of control mice relative to KD mice. Desulfovibrio are sulfate-reducing bacteria associated with inflammatory bowel disease29, while members of the genus Turicibacter were shown to increase with diet-induced obesity30. Collectively, KD increased the relative abundance of microbiota that are putatively able to protect neurovascular integrity, as well as reduced those which may induce inflammation.

Table 1

Diet changes in gut microbiome composition.

| Genera with significantly different relative abundance between control and KD animals* | Control | KD | p-value | FDRC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phylum Actinobacteria | ||||

| Class Coriobacteriia; Order Coriobacteriales; Family Coriobacteriaceae; Genus Adlercreutzia | 28.5 | 60.2 | 0.002 | 0.019 |

| Phylum Firmicutes | ||||

| Class Bacilli; Order Lactobacillales; Family Lactobacillaceae; Genus Lactobacillus | 142.8 | 453.4 | 0.006 | 0.008 |

| Class Bacilli; Order Turicibacterales; Family Turicibacteraceae; Genus Turicibacter | 120.2 | 1.6 | 0.000 | 0.008 |

| Class Clostridia; Order Clostridiales; Family Clostridiaceae; Genus Clostridium | 2.1 | 0.2 | 0.002 | 0.019 |

| Class Clostridia; Order Clostridiales; Family Lachnospiraceae; Genus Dorea | 19.7 | 4.0 | 0.002 | 0.019 |

| Class Erysipelotrichi; Order Erysipelotrichales; Family Erysipelotrichaceae; Genus Clostridium | 187.0 | 831.2 | 0.003 | 0.020 |

| Phylum Proteobacteria | ||||

| Class Deltaproteobacteria; Order Desulfovibrionales; Family Desulfovibrionaceae; Genus Desulfovibrio | 53.4 | 0.0 | 0.001 | 0.015 |

| Phylum Verrucomicrobia | ||||

| Class Verrucomicrobiae; Order Verrucomicrobiales; Family Verrucomicrobiaceae; Genus Akkermansia** | 792.1 | 1943.9 | 0.005 | 0.028 |

*Data for ‘Control’ and ‘KD’ are presented as mean number of reads per sample, based on a rarefied sequencing depth of 10,000 sequences/sample. The p-value is derived from a Kruskal-Wallis test, and the FDRC is the Benjamini-Hochberg false-discovery rate adjusted p-value. Only those genus-level taxa with an FDRC <0.05 are shown.

**All Akkermansia sequences were annotated to the taxonomic level of species as A. muciniphila.

Ketogenic diet modulates blood ketone and glucose, and decreases body weight

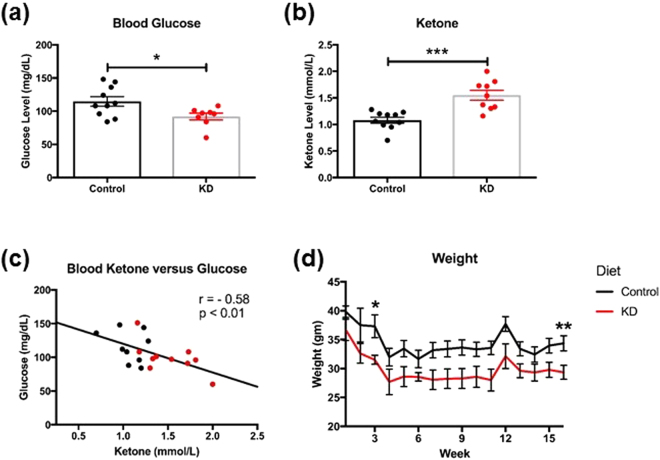

A. muciniphila can increase insulin sensitivity31, and exhibits a negative correlation with body-mass index32. Consistent with our gut microbiome findings, we observed a significant decrease in blood glucose level in the KD mice (Fig. 3a; −19.97%; p =

= 0.01). With KD feeding, mice exhibited significantly higher ketone concentration when compared to the control group (Fig. 3b; 43.48%; p

0.01). With KD feeding, mice exhibited significantly higher ketone concentration when compared to the control group (Fig. 3b; 43.48%; p =

= 0.0004). Interestingly, there was a significant inverse correlation between ketone level and blood glucose measurements (Fig. 3c; Pearson’s r

0.0004). Interestingly, there was a significant inverse correlation between ketone level and blood glucose measurements (Fig. 3c; Pearson’s r =

= − 0.58; r2

− 0.58; r2 =

= 0.33, p

0.33, p <

< 0.01). Another interesting aspect of the present study is that KD mice lost body weight despite having higher energy intake (7.24

0.01). Another interesting aspect of the present study is that KD mice lost body weight despite having higher energy intake (7.24 kcal/gm) compared to the control mice (3.79

kcal/gm) compared to the control mice (3.79 kcal/gm). KD mice exhibited reduced body weight by week 3 (Fig. 3d; −15.50%; p

kcal/gm). KD mice exhibited reduced body weight by week 3 (Fig. 3d; −15.50%; p =

= 0.0096), and this trend continued for the remainder of the study. At the time of the final measurement, the KD mice maintained significantly lower weights than the control mice (−14.58%; p

0.0096), and this trend continued for the remainder of the study. At the time of the final measurement, the KD mice maintained significantly lower weights than the control mice (−14.58%; p =

= 0.0042). Our findings are consistent with literature that KD reduces blood glucose levels33 and body weight34.

0.0042). Our findings are consistent with literature that KD reduces blood glucose levels33 and body weight34.

Ketogenic diet modulates blood ketone and glucose, and decreases body weight. (a) KD mice had significantly lower blood glucose and (b) significantly higher blood ketone levels than control mice. (c) A scatter plot of blood ketone and glucose showing an inverse linear relationship (Pearson’s r =

= −0.5761, p

−0.5761, p <

< 0.01) where each point represents a mouse (n

0.01) where each point represents a mouse (n =

= 19). (d) KD mice had a significant decrease in weight over the 16 weeks compared to control mice.

19). (d) KD mice had a significant decrease in weight over the 16 weeks compared to control mice.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that KD enhanced neurovascular functions and increased beneficial gut microbiota in young healthy mice. In particular, KD enhanced BBB function by increasing protein expression and transport activity of the Aβ transporter P-gp, increased CBF in VMH, and reduced mTOR with increased eNOS protein expressions. In addition, KD increased potentially beneficial gut microorganisms, including A. muciniphila and bacteria from the genus Lactobacillus. KD also reduced potentially pro-inflammatory taxa, including bacteria from the genera Desulfovibrio and Turicibacter. We also found that mice fed with KD had reduced blood glucose levels and body weight, and increased blood ketone body levels; there was an inverse correlation between blood glucose and ketone bodies levels. Collectively, KD showed multifactorial benefits for mice even under healthy conditions.

The enhancements of CBF, BBB transporter activities, and potentially increased Aβ clearance suggest that mice with KD may have lower risk to develop age-related neurodegenerative disorders, including AD. This is consistent with literature that KD reduces Aβ toxicity and restores memory in animal models that develop AD-like symptoms35–38. This also agrees with our previous findings showing that preserving CBF and BBB integrity is critical in preventing AD development in a mouse model with human APOE4 gene, the strongest genetic risk factor for AD39; and restoring CBF improves memory in a symptomatic AD mouse model21. Our findings are consistent with literature showing that an acute increase in ketone body levels elevated CBF in rats37 and humans36.

We further demonstrate that mTOR inhibition may play an important role in neurovascular enhancements. mTOR is a nutrient sensor and its activity can be down-regulated when glucose availability is reduced or ketogenesis is increased40. Similar to caloric restriction, mTOR inhibition can preserve brain metabolism with age41, potentially due to the shift from glucose to ketone body utilization42. In the present study, we found that KD mice exhibited significantly lower expression of mTOR, but significantly increased expression of eNOS. This is consistent with our previous study using rapamycin, showing that mTOR inhibition can activate eNOS, which causes the release of nitric oxide, a vessel dilator, and consequently elevates CBF21,23. This is also consistent with studies showing that down-regulation of mTOR is associated with elevated P-gp expression23. The neurovascular enhancements by mTOR inhibition were associated with preserved white matter integrity and long-term memory, and reduced anxiety in aging mice23,43.

Gut microbiome alterations induced by KD may also contribute to the neurovascular enhancements. We found that KD significantly increased the relative abundance of A. muciniphila and Lactobacillus, known to produce SCFAs25–27. SCFAs are transported by monocarboxylate transporters expressed at the BBB44,45. Lack of SCFAs can cause higher BBB permeability7,8,11. On the other hand, we found that Desulfovibrio was absent in KD mice. This is consistent with a prior study showing that KD significantly decreases the abundance of Desulfovibrio in Glucose Transporter 1 Deficiency Syndrome29. Members of the genus Desulfovibrio are capable of respiring sulfate and producing hydrogen sulfide, which is known to induce gut barrier impairment46. Consequently, reducing the abundance of Desulfovibrio may also facilitate BBB and neurovascular enhancements. Together, changes in relative abundance of A. muciniphila, Lactobacillus, and Desulfovibrio may contribute to protection of neurovascular functions.

We found that KD decreased overall microbial diversity. This is likely a result of reduced carbohydrate intake, which decreases the polysaccharide content that many gut bacteria derive energy from47. Although other studies suggested that reduced microbiome diversity may be associated with disease progression48, we found that levels of several beneficial microbiota were increased, even though the overall diversity was reduced by KD. In part, the decrease in diversity (Shannon index) can be attributed to the substantially higher relative abundance of A. muciniphila in KD mice, reaching nearly 20% of the observed microbial community. Future studies are needed to further identify the different contributions between overall diversity and underlying taxonomy for health and diseases. In addition, shotgun metagenome and metatranscriptome sequencing efforts will be required to associate specific metabolic capabilities (e.g., SCFAs production) with identified taxa, and to demonstrate where and when these genes are expressed in situ in the gastrointestinal tract.

We confirmed that KD is able to reduce body weight34 and lower blood glucose level33. This could be due to increased relative abundance of A. muciniphila and Lactobacillus spp. The relative abundance of A. muciniphila also increases when type 2 diabetic patients are given metformin49, a prescribed medication to increase glucose utilization and reduce body weight by activating AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway50. Accordingly, A. muciniphila is associated with increased insulin sensitivity31 and reduced body weight32. Similar results could be elicited by Lactobacillus through SCFAs production. In line with this, Lactobacillus has been shown in several studies to decrease body weight and fat51.

Being able to maintain proper body weight and blood glucose level is crucial for reducing risk for AD, which is known as type 3 diabetes with increased glucose intolerance in the brain52. In fact, diabetes or obesity is highly associated with glucose intolerance, insulin insensitivity, and increased risk for AD53. Recent advances indicate that excessive white fat increases secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines from adipocytes, which could consequently lead to neuroinflammation, Aβ retention, brain cell death, and dementia54. In a study with obese rats, KD reduced their body weight and improved their lipid profile55. In addition, KD decreases pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α), down-regulates brain amyloid protein precursor, and improves brain oxidative stress of the obese rats. Furthermore, KD improves hippocampal glycolytic and tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates and amino acid in a 3xTgAD mouse model56, suggesting that KD may also improve insulin sensitivity in the brain57. It indicates that KD-induced body weight loss may evoke metabolic and immune function changes that potentially lead to neuroprotective effects. This is consistent with a human study that diet-induced weight loss improves functional brain responses during an episodic memory task58.

Although KD mice had higher energy intake per gram of the food (due to high fat content) compared to the control mice, they still showed lower body weight. As ketone bodies could enhance fatty acid metabolism, we speculate that KD would switch from burning carbohydrate to fat and thus facilitate fat utilization more effectively in the body59. This is consistent with a clinical study that people with obesity lost three times more visceral adipose tissue with KD60.

There were several limitations in the present study. We did not measure levels of SCFAs, and tight junction protein in the intestinal barrier and BBB. Therefore, we could not identify further linkages between the gut microbiome changes and brain vascular protection. In addition, we used DNA-based amplicon profiling of the microbial community in fecal samples to determine the diversity and taxonomy of gut microbiota. We acknowledge that the various compartments of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract harbor different bacterial populations61; therefore, future studies will need to include different parts of the GI tracts for gut microbiome analysis, and to incorporate shotgun sequencing approaches to the community profiling to improve taxonomic resolution and to measure gene expression activity.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that KD enhanced neurovascular functions, which might be associated with the diet-induced changes in gut microbiome. Our results indicate that KD may not only be beneficial in disease states, but also in healthy condition. These findings imply that dietary intervention started in early stages may evoke neuroprotective effects via neurovascular and gut microbiome changes. Future studies will be needed to further identify the mechanism linking brain and gut interactions for KD-induced neuroprotective effects in both healthy and disease states. Understanding nutritional effects on central and enteric nervous systems, and their interactions, has profound implications for neuroprotection in humans.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Diet

We used C57BL/6 male mice (12–14 weeks of age) obtained from the National Institutes of Health. We determined the sample size with the power that could perform the comparison at a 0.05 level of significance, with a 90% chance of detecting a true difference of all the measurements between the two groups; N =

= 9–10 per group were used in the study. After arriving at our facilities, each mouse was given its own cage housed in a specific pathogen-free facility to avoid microbiome transfer62. The control regimen (type F1515) consisted of 3.79

9–10 per group were used in the study. After arriving at our facilities, each mouse was given its own cage housed in a specific pathogen-free facility to avoid microbiome transfer62. The control regimen (type F1515) consisted of 3.79 kcal/gm pellets composed of 65.2% carbohydrates, 18.1% protein, 5.1% fat, 4.8% fiber, 2.9% ash, and less than 10% moisture. The KD regimen (type F3666), in the form of a 7.24

kcal/gm pellets composed of 65.2% carbohydrates, 18.1% protein, 5.1% fat, 4.8% fiber, 2.9% ash, and less than 10% moisture. The KD regimen (type F3666), in the form of a 7.24 kcal/gm paste, consisted of 75.1% fat (composed of saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fatty acids), 8.6% protein, 4.8% fiber, 3.2% carbohydrates, 3.0% ash, and less than 10% moisture. Both diets were obtained from Bio-Serv. All mice were fed ad libitum for 16 weeks, and body weight was measured once a week. The amount of remaining diet was weighted each week to determine the food intake of the mice. We did not find a significant difference in food intake between the control (46

kcal/gm paste, consisted of 75.1% fat (composed of saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fatty acids), 8.6% protein, 4.8% fiber, 3.2% carbohydrates, 3.0% ash, and less than 10% moisture. Both diets were obtained from Bio-Serv. All mice were fed ad libitum for 16 weeks, and body weight was measured once a week. The amount of remaining diet was weighted each week to determine the food intake of the mice. We did not find a significant difference in food intake between the control (46 ±

± 3

3 g/mouse/week) and KD mice (47

g/mouse/week) and KD mice (47 ±

± 2

2 g/mouse/week; p

g/mouse/week; p >

> 0.5). All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Kentucky (UK) and in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines63.

0.5). All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Kentucky (UK) and in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines63.

Cerebral Blood Flow Measurement

We measured CBF using MRI-based arterial spin labeling techniques. Details have been described in a previous study23. Briefly, MRI experiments were performed on a 7T MR scanner (Clinscan, Bruker BioSpin, Germany) at the Magnetic Resonance Imaging & Spectroscopy Center of the University of Kentucky. Mice were anesthetized with 4.0% isoflurane for induction and then maintained in a 1.2% isoflurane and air mixture using a nose cone. Heart rate (90–110 bpm), respiration rate (50–80 breaths/min), and rectal temperature (37

bpm), respiration rate (50–80 breaths/min), and rectal temperature (37 ±

± 1

1 °C) was continuously monitored and maintained. A water bath with circulating water at 45–50

°C) was continuously monitored and maintained. A water bath with circulating water at 45–50 °C was used to maintain the body temperature. A whole-body volume coil was used for transmission and a mouse brain surface coil was placed on top of the head for receiving. We measured CBF using MRI-based pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling (pCASL) techniques23. Paired control and label images were acquired in an interleaved fashion with a train of Hanning window-shaped radiofrequency pulses of duration/spacing

°C was used to maintain the body temperature. A whole-body volume coil was used for transmission and a mouse brain surface coil was placed on top of the head for receiving. We measured CBF using MRI-based pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling (pCASL) techniques23. Paired control and label images were acquired in an interleaved fashion with a train of Hanning window-shaped radiofrequency pulses of duration/spacing =

= 200/200

200/200 μs, flip angle

μs, flip angle =

= 25° and slice-selective gradient

25° and slice-selective gradient =

= 9

9 mT/m, and a labeling duration

mT/m, and a labeling duration =

= 2100

2100 ms. The images were acquired by 2D multi-slice spin-echo echo planner imaging with FOV

ms. The images were acquired by 2D multi-slice spin-echo echo planner imaging with FOV =

= 18

18 ×

× 18

18 mm2, matrix

mm2, matrix =

= 128

128 ×

× 128, slice thickness

128, slice thickness =

= 1

1 mm, 10 slices, TR

mm, 10 slices, TR =

= 4,000

4,000 ms, TE

ms, TE =

= 35

35 ms, and 120 repetitions. pCASL images were analyzed with in-house written codes in MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA) to obtain quantitative CBF (with units of mL/g per minute). Brain structural T2-weighted images were acquired with field of view (FOV)

ms, and 120 repetitions. pCASL images were analyzed with in-house written codes in MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA) to obtain quantitative CBF (with units of mL/g per minute). Brain structural T2-weighted images were acquired with field of view (FOV) =

= 18

18 ×

× 18

18 mm2, matrix

mm2, matrix =

= 256

256 ×

× 256; slice thickness

256; slice thickness =

= 1

1 mm, 10 slices, repetition time (TR)

mm, 10 slices, repetition time (TR) =

= 1500

1500 ms, and echo time (TE)

ms, and echo time (TE) =

= 35

35 ms. The CBF images were then superimposed to the corresponding structural images using Multi-Image Analysis GUI (Mango) software (http://rii.uthscsa.edu/mango/).

ms. The CBF images were then superimposed to the corresponding structural images using Multi-Image Analysis GUI (Mango) software (http://rii.uthscsa.edu/mango/).

Gut Microbiome Analyses

Fecal DNA Amplification

The experimental protocol has been described in a previous study64. Fecal samples were collected from control and KD mice and frozen at −80 °C until further use. The PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (MO BIO Laboratories, Inc.) was used for fecal DNA extraction, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Genomic DNA was PCR amplified with primers 515

°C until further use. The PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (MO BIO Laboratories, Inc.) was used for fecal DNA extraction, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Genomic DNA was PCR amplified with primers 515 F modified and 926R65 targeting the V4-V5 regions of microbial 16S rRNA genes using a two-stage “targeted amplicon sequencing (TAS)” protocol66. The primers contained 5′ common sequence tags (known as common sequence 1 and 2, CS1 and CS2) as described previously67. First stage amplifications were performed with the following thermocycling conditions: 95

F modified and 926R65 targeting the V4-V5 regions of microbial 16S rRNA genes using a two-stage “targeted amplicon sequencing (TAS)” protocol66. The primers contained 5′ common sequence tags (known as common sequence 1 and 2, CS1 and CS2) as described previously67. First stage amplifications were performed with the following thermocycling conditions: 95 °C for 3

°C for 3 mins, 28 cycles of 95

mins, 28 cycles of 95 °C for 45

°C for 45 sec, 50

sec, 50 °C for 45

°C for 45 sec, 72

sec, 72 °C for 1:30

°C for 1:30 minutes and final elongation at 72

minutes and final elongation at 72 °C for 10

°C for 10 minutes. The PCR master mix was made in a total volume of 25

minutes. The PCR master mix was made in a total volume of 25 µl of reaction mixture containing 4

µl of reaction mixture containing 4 µl (100

µl (100 ng) of DNA template, 0.5

ng) of DNA template, 0.5 µl (20

µl (20 µM) of each forward and reverse primers, 12.5

µM) of each forward and reverse primers, 12.5 µl of PCR ready-to-use mixture (MyTaq HS Mix 2x, Bioline, London, UK) and 7.5

µl of PCR ready-to-use mixture (MyTaq HS Mix 2x, Bioline, London, UK) and 7.5 µl of distilled water.

µl of distilled water.

Subsequently, a second PCR amplification was performed in 10 microliter reactions in 96-well plates. A mastermix for the entire plate was made using the MyTaq HS 2X mastermix. Each well received a separate primer pair with a unique 10-base barcode, obtained from the Access Array Barcode Library for Illumina (Fluidigm, South San Francisco, CA; Item# 100-4876). These Access Array primers contained the CS1 and CS2 linkers at the 3′ ends of the oligonucleotides. Cycling conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 5

°C for 5 minutes, followed by 8 cycles of 95

minutes, followed by 8 cycles of 95 °C for 30”, 60

°C for 30”, 60 °C for 30” and 72

°C for 30” and 72 °C for 30”. A final, 7-minute elongation step was performed at 72

°C for 30”. A final, 7-minute elongation step was performed at 72 °C. PCR products were purified using SequalPrep plates (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequently, these PCR products were quantified using a Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher), implemented on a Genios Pro Fluorescence microplate reader (Tecan). PCR products were then pooled using PicoGreen quantification results, using an epMotion5075 liquid handling workstation (Eppendorf).

°C. PCR products were purified using SequalPrep plates (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequently, these PCR products were quantified using a Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher), implemented on a Genios Pro Fluorescence microplate reader (Tecan). PCR products were then pooled using PicoGreen quantification results, using an epMotion5075 liquid handling workstation (Eppendorf).

The pooled libraries, with a 15% phiX spike-in, were loaded on to a MiSeq v3 flow cell, and sequenced using an Illumina MiSeq sequencer, with paired-end 300 base reads. Fluidigm sequencing primers, targeting the CS1 and CS2 linker regions, were used to initiate sequencing. De-multiplexing of reads was performed on instrument. Second stage PCR amplification and library pooling was performed at the DNA Services (DNAS) facility, Research Resources Center (RRC), University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC). Sequencing was performed at the W.M. Keck Center for Comparative and Functional Genomics at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC).

Microbial Analysis

Forward and reverse reads were merged using PEAR68. Primer sequences were identified using Smith-Watermann alignment and trimmed from the sequence. Reads that lacked either primer sequence were discarded. Sequences were then trimmed based on quality scores using a modified Mott algorithm with PHRED quality threshold of p =

= 0.01, and sequences shorter than 300 bases after trimming were discarded. QIIME v1.8 was used to generate OTU tables and taxonomic summaries24. Briefly, the resulting sequence files were merged with sample information. OTU clusters were generated in a de novo manner using the UCLUST algorithm with a 97% similarity threshold69. Chimeric sequences were identified using the USEARCH61 algorithm with the GreenGenes 13_8 reference sequences70. Taxonomic annotations for each OTU were using the UCLUST algorithm and GreenGenes 13_8 reference with a minimum similarity threshold of 90%69,70. Taxonomic and OTU abundance data were merged into a single OTU table and summaries of absolute abundances of taxa were generated for all phyla, classes, orders, families, genera, and species present in the dataset. The taxonomic summary tables were then rarefied to a depth of 10,000 counts per sample.

0.01, and sequences shorter than 300 bases after trimming were discarded. QIIME v1.8 was used to generate OTU tables and taxonomic summaries24. Briefly, the resulting sequence files were merged with sample information. OTU clusters were generated in a de novo manner using the UCLUST algorithm with a 97% similarity threshold69. Chimeric sequences were identified using the USEARCH61 algorithm with the GreenGenes 13_8 reference sequences70. Taxonomic annotations for each OTU were using the UCLUST algorithm and GreenGenes 13_8 reference with a minimum similarity threshold of 90%69,70. Taxonomic and OTU abundance data were merged into a single OTU table and summaries of absolute abundances of taxa were generated for all phyla, classes, orders, families, genera, and species present in the dataset. The taxonomic summary tables were then rarefied to a depth of 10,000 counts per sample.

Shannon and Bray-Curtis indices were calculated with default parameters in software package Primer771. The rarefied species data, taxonomic level 6, were used to calculate both indices. Significant difference among tested groups was determined using the Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance. The group significance tests were performed on the rarefied species data using the group_significance.py script within the QIIME v1.8 package. The gene amplicon sequence data generated as part of this study have been submitted to the NCBI BioProject database (PRJNA401034).

P-glycoprotein (P-gp) Transport Determination and Western Blotting

Capillary isolation

Details of the experiments have been described in previous studies23,64. Brain capillaries were isolated from mice according to a previously described protocol23. Briefly, mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation and decapitated; brains were immediately harvested and collected in ice-cold DPBS buffer supplemented with 5 mM D-glucose and 1

mM D-glucose and 1 mM Na-pyruvate, pH 7.4. Brains were dissected by removing meninges, choroid plexus and white matter, and homogenized in DPBS. The brain homogenate was mixed with Ficoll® and centrifuged at 5,800

mM Na-pyruvate, pH 7.4. Brains were dissected by removing meninges, choroid plexus and white matter, and homogenized in DPBS. The brain homogenate was mixed with Ficoll® and centrifuged at 5,800 g for 15

g for 15 min at 4

min at 4 °C. The capillary pellet was resuspended in 1% BSA buffer and first passed through a 300

°C. The capillary pellet was resuspended in 1% BSA buffer and first passed through a 300 µm nylon mesh followed by filtration through a 27

µm nylon mesh followed by filtration through a 27 µm nylon mesh. Capillaries retained by the 27

µm nylon mesh. Capillaries retained by the 27 µm nylon mesh were collected and washed with DPBS buffer, and used for experiments.

µm nylon mesh were collected and washed with DPBS buffer, and used for experiments.

P-glycoprotein transport activity

Isolated brain capillaries were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with 2

h at room temperature with 2 μM NBD-CSA (custom-synthesized by R. Wenger, Basel, Switzerland) in DPBS buffer. Per treatment group, 10 capillary images were acquired by confocal microscopy (Leica TSP SP5 Confocal Microscope with Environmental Chamber, 63

μM NBD-CSA (custom-synthesized by R. Wenger, Basel, Switzerland) in DPBS buffer. Per treatment group, 10 capillary images were acquired by confocal microscopy (Leica TSP SP5 Confocal Microscope with Environmental Chamber, 63 ×

× D-Water UV objective, numerical aperture 1.2, 488-nm line of an argon laser, Leica Microsystems). Confocal images were analyzed by quantitating luminal NBD-CSA fluorescence with Image J software (v.1.45

D-Water UV objective, numerical aperture 1.2, 488-nm line of an argon laser, Leica Microsystems). Confocal images were analyzed by quantitating luminal NBD-CSA fluorescence with Image J software (v.1.45 s; Wayne Rasband, NIH). Specific, luminal NBD-CSA fluorescence was taken as the difference between total luminal fluorescence and fluorescence in the presence of the P-glycoprotein specific inhibitor PSC833 (5

s; Wayne Rasband, NIH). Specific, luminal NBD-CSA fluorescence was taken as the difference between total luminal fluorescence and fluorescence in the presence of the P-glycoprotein specific inhibitor PSC833 (5 μM, Novartis, Basel, Switzerland).

μM, Novartis, Basel, Switzerland).

Western blotting and quantification

To determine protein expression, isolated brain capillaries were homogenized in tissue lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail. Homogenized brain capillary samples were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 15

g for 15 min at 4

min at 4 °C, followed by centrifugation of the denucleated supernatants at 100,000

°C, followed by centrifugation of the denucleated supernatants at 100,000 g for 90

g for 90 min at 4

min at 4 °C. Pellets (crude brain capillary plasma membranes) were resuspended and protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford protein assay. Western blots were performed using the NuPage™ electrophoresis and blotting system from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Blotting membranes were incubated overnight with antibody to P-gp (C219; MA1-26528, ThermoFisher, 1

°C. Pellets (crude brain capillary plasma membranes) were resuspended and protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford protein assay. Western blots were performed using the NuPage™ electrophoresis and blotting system from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Blotting membranes were incubated overnight with antibody to P-gp (C219; MA1-26528, ThermoFisher, 1 μg/ml), mTOR (ab134903, Abcam, 1

μg/ml), mTOR (ab134903, Abcam, 1 μg/ml), GLUT1 (ab652, Abcam, 1

μg/ml), GLUT1 (ab652, Abcam, 1 μg/ml), and β-actin (ab8226 from Abcam, 1:1000, 1

μg/ml), and β-actin (ab8226 from Abcam, 1:1000, 1 μg/ml). Proteins were detected using SuperSignal® West Pico Chemoluminescent substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) and protein bands were visualized with a BioRad Gel Doc™ XRS imaging system. Image Lab 5.0 software from Bio-Rad Laboratories was used for densitometric analyses of band intensities and digital molecular weight analyses; the molecular weight marker was RPN800E (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, Buckinghamshire, UK). Linear adjustments of contrast and brightness were applied to entire Western blot images. None of the Western blots shown were modified by nonlinear adjustments.

μg/ml). Proteins were detected using SuperSignal® West Pico Chemoluminescent substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) and protein bands were visualized with a BioRad Gel Doc™ XRS imaging system. Image Lab 5.0 software from Bio-Rad Laboratories was used for densitometric analyses of band intensities and digital molecular weight analyses; the molecular weight marker was RPN800E (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, Buckinghamshire, UK). Linear adjustments of contrast and brightness were applied to entire Western blot images. None of the Western blots shown were modified by nonlinear adjustments.

Blood Glucose and Ketone Bodies Measurements

The procedure has been described in a previous study43. When the mice were sacrificed, blood samples were collected in 500 μl lithium heparin 12.5

μl lithium heparin 12.5 IU Terumo Capiject Capillary blood collection tubes (Vacutainer K2 EDTA) to avoid blood coagulation. A total of 1–2

IU Terumo Capiject Capillary blood collection tubes (Vacutainer K2 EDTA) to avoid blood coagulation. A total of 1–2 μl of blood sample were used to measure blood glucose level using a blood glucose meter and a test strip (Clarity Plus, Boca Raton, FL, USA). Another 10

μl of blood sample were used to measure blood glucose level using a blood glucose meter and a test strip (Clarity Plus, Boca Raton, FL, USA). Another 10 μl of blood sample was used for ketone bodies level measurement using a STAT-Site M (β-Hydroxybutyrate) meter and a test strip (Standbio Ketosite STAT-Site M-β HB, Boerne, TX, USA).

μl of blood sample was used for ketone bodies level measurement using a STAT-Site M (β-Hydroxybutyrate) meter and a test strip (Standbio Ketosite STAT-Site M-β HB, Boerne, TX, USA).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). One-tailed Student’s t-test was performed for determination of differences between the two groups. Values of p <

< 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NIH/NIA grants R01AG054459 and K01AG040164, NIH/CTSA grant UL1TR000117, and American Federation for Aging Research Grant #A12474 to A-LL, NIH/NIA grant R01AG039621 to AMSH, NIH/NINDS grant R01NS079507 to BB, and NIH/NIDDK Training Grant T32DK007778 to JDH. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging or the National Institutes of Health. The MRI imaging and data were processed using MANGO software developed by the Research Imaging Institute of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. The 7 T ClinScan small animal MRI scanner of UK was funded by the S10 NIH Shared Instrumentation Program Grant (1S10RR029541-01). We thank Vikas Bakshi, Janet Guo, Max Baker, Stephanie Edelmann, and Ralf Rempe of the University of Kentucky for assisting the experiments.

T ClinScan small animal MRI scanner of UK was funded by the S10 NIH Shared Instrumentation Program Grant (1S10RR029541-01). We thank Vikas Bakshi, Janet Guo, Max Baker, Stephanie Edelmann, and Ralf Rempe of the University of Kentucky for assisting the experiments.

Author Contributions

D.M., A.C.W., I.P., and A.-L.L. contributed to the major design, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data for the work. S.J.G., G.C., and I.P. contributed to the gut microbiome analysis. B.S.S., A.M.S.H. and B.B. contributed to data acquisition and analysis related to blood-brain barrier functions. D.M., A.C.W., I.P., J.D.H., S.J.G., G.C., M.P.M., B.S.S., B.B., A.M.S.H., and A.-L.L. drafted and revised the work for important intellectual content. D.M., A.C.W., I.P., J.D.H., S.J.G., G.C., M.P.M., B.S.S., B.B., A.M.S.H., and A.-L.L. approved of the final version and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Articles from Scientific Reports are provided here courtesy of Nature Publishing Group

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-25190-5

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-25190-5.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

Ketogenic diets are associated with an elevated risk of hypertension: Insights from a cross-sectional analysis of the NHANES 2007-2018.

Int J Cardiol Cardiovasc Risk Prev, 23:200342, 10 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39484088 | PMCID: PMC11525463

Machine Learning-Driven Prediction of Brain Age for Alzheimer's Risk: APOE4 Genotype and Gender Effects.

Bioengineering (Basel), 11(9):943, 20 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39329685 | PMCID: PMC11429338

The gut microbiota changed by ketogenic diets contribute to glucose intolerance rather than lipid accumulation.

Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 15:1446287, 27 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39398341 | PMCID: PMC11466860

Metabarcoding study of potential pathogens and zoonotic risks associated with dog feces in Seoul, South Korea.

PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 18(8):e0012441, 28 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39196875 | PMCID: PMC11355564

Decoding the Gut Microbiome in Companion Animals: Impacts and Innovations.

Microorganisms, 12(9):1831, 04 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39338505 | PMCID: PMC11433972

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (144) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

BioProject

- (1 citation) BioProject - PRJNA401034

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

mTOR Attenuation with Rapamycin Reverses Neurovascular Uncoupling and Memory Deficits in Mice Modeling Alzheimer's Disease.

J Neurosci, 41(19):4305-4320, 22 Apr 2021

Cited by: 29 articles | PMID: 33888602 | PMCID: PMC8143195

Ketogenic Diets Induced Glucose Intolerance and Lipid Accumulation in Mice with Alterations in Gut Microbiota and Metabolites.

mBio, 12(2):e03601-20, 30 Mar 2021

Cited by: 22 articles | PMID: 33785628 | PMCID: PMC8092315

Ketogenic diet modifies the gut microbiota in a murine model of autism spectrum disorder.

Mol Autism, 7(1):37, 01 Sep 2016

Cited by: 123 articles | PMID: 27594980 | PMCID: PMC5009541

Ketogenic Diet: A Dietary Intervention via Gut Microbiome Modulation for the Treatment of Neurological and Nutritional Disorders (a Narrative Review).

Nutrients, 14(17):3566, 30 Aug 2022

Cited by: 22 articles | PMID: 36079829 | PMCID: PMC9460077

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NCATS NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: UL1 TR000117

NCRR NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: S10 RR029541

NIA NIH HHS (4)

Grant ID: RF1 AG039621

Grant ID: R01 AG054459

Grant ID: R01 AG039621

Grant ID: K01 AG040164

NIDDK NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: T32 DK007778

NINDS NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: R01 NS079507

1,3,6

1,3,6