Abstract

Purpose

For postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer, long-term use of aromatase inhibitors (AIs) significantly reduces the risk of cancer recurrence and improves survival. Still, many patients are nonadherent due to adverse side effects. We conducted a pilot randomized controlled trial to test the use of a web-based application (app) designed with and without weekly reminders for patients to report real-time symptoms and AI use outside of clinic visits with built-in alerts to patients' oncology providers. Our goal was to improve symptom burden and medication adherence.Methods

Forty-four women with early-stage breast cancer and a new AI prescription were randomized to either an App+Reminder (weekly reminders to use app) or an App (no reminders) group. Pre- and post-assessment data were collected from all participants.Results

Participants in the App+Reminder group had higher weekly app usage rate (74 vs. 38%, p < 0.05) during the intervention and reported higher AI adherence at 8 weeks (100 vs. 72%, p < 0.05). Symptom burden increase was higher for the App group compared to the App+Reminder group but did not reach statistical significance.Conclusions

Weekly reminders to use a web-based app to report AI adherence and treatment-related symptoms demonstrated feasibility and improved short-term AI adherence, which may reduce symptom burden for women with breast cancer and a new AI prescription.Implications for cancer survivors

If short-term gains in adherence persist, this low-cost intervention could improve survival outcomes for women with breast cancer. A larger, long-term study should examine if AI adherence and symptom burden improvements persist for a 5-year treatment period.Free full text

Use of a Web-based App to Improve Breast Cancer Symptom Management and Adherence for Aromatase Inhibitors: A Randomized Controlled Feasibility Trial

Abstract

Purpose

For postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer, long-term use of aromatase inhibitors (AIs) significantly reduces the risk of cancer recurrence and improves survival. Still, many patients are nonadherent due to adverse side effects. We conducted a pilot randomized controlled trial to test the use of a web-based application (app) designed with and without weekly reminders for patients to report real-time symptoms and AI use outside of clinic visits with built-in alerts to patients’ oncology providers. Our goal was to improve symptom burden and medication adherence.

Methods

Forty-four women with early-stage breast cancer and a new AI prescription were randomized to either an App+Reminder (weekly reminders to use app) or App (no reminders) group. Pre- and post-assessment data were collected from all participants.

Results

Participants in the App+Reminder group had higher weekly app usage rate (74% vs. 38%, p<0.05) during the intervention and reported higher AI adherence at 8 weeks (100% vs. 72%, p<0.05). Symptom burden increase was higher for the App group compared to the App+Reminder group, but did not reach statistical significance.

Conclusions

Weekly reminders to use a web-based app to report AI adherence and treatment-related symptoms demonstrated feasibility and improved short-term AI adherence, which may reduce symptom burden for women with breast cancer and a new AI prescription.

Implications

If short-term gains in adherence persist, this low-cost intervention could improve survival outcomes for women with breast cancer. A larger, long-term study should examine if AI adherence and symptom burden improvements persist for a five-year treatment period.

INTRODUCTION

One in eight women are diagnosed with breast cancer during their lifetime; among them more than 80% have hormone receptor-positive (HR+) tumors [1]. Aromatase inhibitors (AIs), a type of adjuvant endocrine therapy (AET), are commonly prescribed to postmenopausal women with HR+ breast cancer after surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation for a period of five to 10 years to lower cancer recurrence rates and improve survival [2, 3]. The benefit of AET for recurrence and mortality reduction has been shown to be similar for Black and White patients [4]. Despite the potential improvement in survival outcomes, evidence suggests that AI adherence and persistence rates are low [3, 5–8]. Patients who do not take the full amount of their medication as prescribed or who discontinue their AI treatment early do not receive the full, intended treatment benefits and, consequently, are at increased risk for all-cause mortality, cancer death, and recurrence [9]. In addition, AET nonadherence is also associated with poorer quality of life [10], more physician visits and hospitalizations, and longer hospital stays [11, 12].

Multiple studies point to AET-related adverse symptoms as a key reason for nonadherence or premature discontinuation [5, 6, 8, 13–20]. Most patients who become nonadherent discontinue AETs during the first six months when the most severe medication-related toxicities tend to occur [8, 21, 22]. Monitoring adverse effects and symptoms, especially between clinic visits, could help healthcare providers better manage breast cancer patients’ AI treatment and increase long-term adherence. A few studies have started to investigate the feasibility of symptom monitoring among oncology patients using web portals and automated telephone calls [23–25]. Their findings suggest that monitoring patient symptoms outside of clinic visits can reduce adverse symptoms. However, these previous studies focused only on alleviating symptoms, not improving adherence. To date, only five behavioral interventions have specifically aimed to increase AET adherence, and of these, most provided educational materials only, and none showed statistically significant improvements [26–30]. Furthermore, there remains a critical need for evidence on the impact of these types of interventions among underserved, lower income, and minority patients [31].

While there is a well-documented, persistent digital divide, defined as the gulf between individuals with ready access to the internet and those whose access is limited [32], the diffusion of smartphone technology, including smartphone applications (apps), has increased mobile access to the internet, particularly among those most affected by the digital divide (e.g., those with lower socioeconomic status (SES) and racial/ethnic minorities) [33]. This increasing penetration of web-enabled devices, including smartphones, across every segment of the population can be leveraged by the healthcare community as a way to further engage patients between visits in order to improve care quality and health outcomes [34].

Given the pace of clinical practice, the infrequency of clinic visits, and limitations of patient recall, adverse symptoms are often not optimally evaluated or managed [13, 35]. Moreover, a new study found that integrating patient-reported symptoms into routine care increased survival for women with breast cancer [36]. Thus, the ability of healthcare providers to monitor symptom reports via an app and engage in treatment-related communication with patients outside of clinic visits could provide a wide-reaching and potentially cost-effective way to improve symptom management and ultimately health outcomes. Nonetheless, unless patient-reported information is seamlessly integrated into the patient’s medical record, clinical workflow disruption may limit use and effectiveness of the patient-reported data.

In this study, we conducted a pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) to evaluate the feasibility and short-term effect of use of a web-based communication app designed for breast cancer patients to report adverse symptoms and AI adherence outside of clinic visits, with builtin alerts sent to patients’ care teams (i.e., prescribing physician and nurses). All information reported using the app was available for review in the patient’s electronic health record (EHR).

METHODS

Setting

Participants were recruited from the West Cancer Center (WCC) in Memphis, Tennessee. For fourteen years, patients at the WCC have routinely completed a comprehensive assessment of physical and psychological cancer-related symptoms, quality of life, and satisfaction as part of their routine care using the Patient Care Monitor™ (PCM), Vector Oncology Solutions, Memphis TN. The PCM is an electronic, tablet-based patient engagement platform used to collect patient-reported treatment side effects, physical and emotional symptoms, and functional status at the point of care. Patient responses are included in their EHR, and summary reports highlight significant changes as well as elevated symptom severity that may require further evaluation and treatment during the clinic visit [37].

Study population

Between December 2015 and June 2016, patients receiving a new prescription for AI therapy as an adjuvant treatment for primary breast cancer were screened for this study. The study was open to English-speaking female WCC patients at least 18 years of age with a diagnosis of early stage (0-III) HR+ breast cancer and a first prescription for an aromatase inhibitor, a valid email address, a mobile device with a data plan or a home computer with an Internet connection, and willingness to complete brief, weekly reports of symptoms on their mobile device or computer. Since AET-related side effects are generally worse at the beginning of treatment, patients with prior use of AET were excluded. Other exclusions included patients with symptomatic rheumatologic disease (since AET can exacerbate joint pain), those with prior chronic daily narcotic usage (since these medications alter a patient’s symptoms), and patients concurrently undergoing surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation treatments (since AET is not typically recommended until completion of these treatments).

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The University of Tennessee Health Science Center Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol. This trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT02957526.

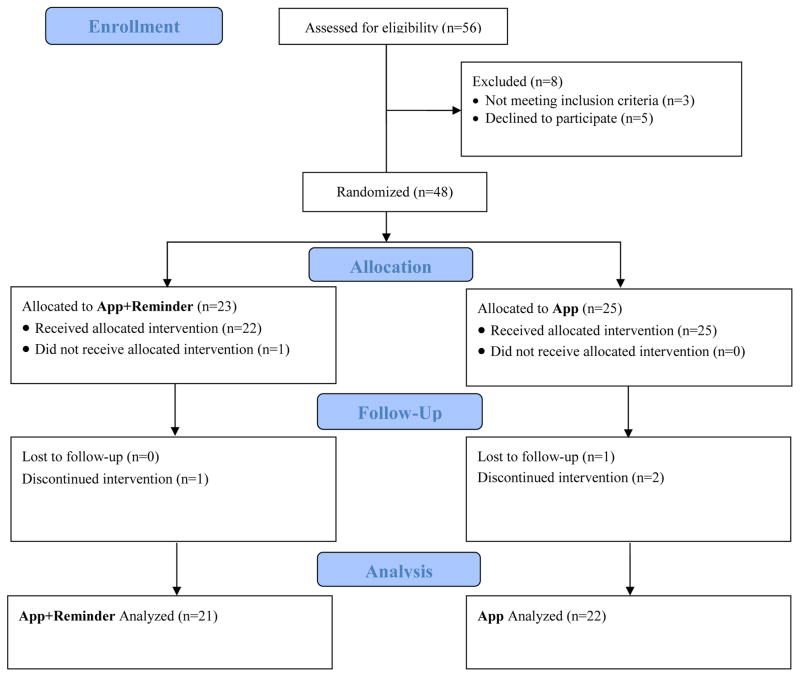

Figure 1 shows the consort diagram. Briefly, of the 56 participants who were assessed for eligibility, 48 were eligible and randomized, 48 began the intervention, and 44 completed the intervention; one participant did not complete the follow-up survey.

Study Design and Treatments

Our trial tested a web-based app designed so that patients can share health information on a real-time basis with their oncology care team using their own web-enabled devices (e.g., smartphone, computer) outside of clinic visits.

The study was a prospective, RCT pilot of a web-based app that provided patients with the ability to report symptoms and AI medication use, with built-in alerts sent to a patient’s care team based on predetermined threshholds. Participants were randomized to two groups: 1) an “App+Reminder” group, who received weekly reminders (either by text message and/or email based on their preference) to use the web-based study app to report symptoms and AI adherence, or 2) an “App” group, who were provided access to the app but did not receive weekly reminders to do so. Both groups completed a baseline and follow-up survey assessing adherence to the AI medication and symptom burden, and app responses (number of logins and data reported) were tracked for the first 6–8 weeks after initiating an AI (until the next scheduled follow-up appointment). Randomization was done by a study research nurse using a set of sealed opaque envelopes numbered consecutively that contained a paper with the condition assignment inside. For each patient, the research nurse would enter the date, screening ID, and condition assignment in a study randomization log.

App and App Alerts

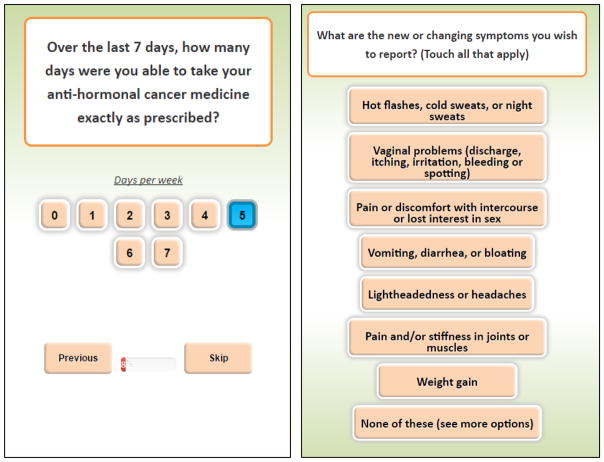

The app was based on a modified version of the PCM designed to be accessed through any web-enabled device or Internet browser outside of clinic visits. To increase study retention, questions were designed to limit the time burden on patients. Figure 2 shows screenshots of the app used in the pilot trial. The app asked participants to respond to two basic questions: 1) AI adherence; and 2) treatment-related adverse symptoms (Figure 2). For AI adherence, we used the single-item adherence measure from the Medication Adherence Reasons (MARS-1) scale, which asked about adherence within the last 7 days [38, 39]. The treatment-related adverse symptoms were based on common AI-related symptoms guided by the physician collaborators, Drs. Schwartzberg and Vidal. If participants reported any adverse symptoms, then they answered follow-up questions about the severity of the reported symptoms using a 10-point scale.

Participants were informed that they could use the app at any time regardless of whether or when they were prompted to do so. Alerts based on response thresholds to adherence and symptom questions were automatically generated to inform the patient’s care team (i.e., prescribing physician and nurse) of any concerning responses or trends that emerged from the patient-reported outcomes via the app. WCC medical oncologists specializing in breast cancer determined the alert thresholds used, which included:

New symptoms (i.e., symptoms not reported in the previous use of the app)

Increase in symptom severity of 4+ points

Reports of 2 or more missed AI doses or not filling the initial prescription

The alert messages were sent to the care team via email. Participating care teams were asked to respond to alerts within 24 hours and make therapeutic adjustments when necessary using standard procedures regarding triage and follow-up in response to alerts. This is similar to how providers respond to patient clinic phone calls; thus, the app intervention did not introduce an unfamiliar process or timeline to responsive task into the existing clinical workflow.

Assessments

All participants completed a survey at baseline and at follow-up (6–8 weeks later at the time of the next scheduled appointment).

AI Adherence

AI adherence was the primary outcome for this study and was self-reported using the four-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-4), a widely used, reliable, and validated self-report instrument [40, 41] collected in the follow-up survey from all participants. Using the MMAS-4, we compared responses to each of the four items and categorized participants as being fully adherent if they answered “No” to each of the four questions about missed doses.

Symptom Burden

Symptom burden was a secondary outcome and was assessed using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Endocrine Symptoms (FACT-ES), an 18-item, self-report instrument designed to assess physical, functional, social, and emotional well-being as well as endocrine symptoms. Items of the FACT-ES ask women to report the occurrence of endocrine-specific symptoms on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from “not at all” to “very much” [42]. Symptom burden was assessed at baseline and in the follow-up survey for all participants. Symptom burden was calculated by adding the four FACT-ES well-being subscales (Physical, Social/Family, Emotional and Functional, each with a range of 0–28 points) to the Endocrine Symptom subscale (range of 0–76 points), and then reversing the scale so that higher scores indicated greater symptom burden.

Participant Characteristics

Several participant-level characteristics were also collected at baseline, including a three-question, validated instrument to assess health literacy [43], demographic characteristics (age, race/ethnicity, marital status), socioeconomic status (education level and household income), and clinical characteristics (breast cancer stage at diagnosis, tumor grade, HR status, and postmenopausal status).

App Usage Logs

Usage logs tracked dates that participants used the app to report AI adherence and/or symptoms, the outcomes they reported, and alerts that were triggered. We calculated the use rate as the number of app reports divided by the number of weeks enrolled in the study.

Intervention Feedback

Among the participants who completed the pilot trial, we invited five of them to also participate in 20-minute telephone interviews. Our selection process was aimed at achieving a diverse sample of experiences with the app (high vs. low use, intervention vs. control). The goal of the interviews was to assess perceived utility and acceptance of the app and any barriers to usage. All interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed according to thematic analysis conventions (see Appendix for interview guide). We also assessed clinical implementation feasibility based on workflow impact reports from providers (e.g., physicians, nurses) obtained during biweekly meetings during the intervention period as well as post-intervention feedback.

Statistical Analysis

We analyzed data from the participants who completed the intervention and follow-up surveys (N=44). Descriptive statistics were computed for age, race/ethnicity, marital status, health literacy, education, income, internet use frequency, tumor grade, and stage of cancer at diagnosis. Baseline comparisons between the two intervention groups were made using χ2 tests. We used t-tests to compare app use (number of reports/number of weeks enrolled) and the number of alerts sent to the care team between the App and App+Reminder group. We compared the primary outcome, self-reported AI adherence that was captured in the follow-up survey, using a χ2 test to compare the two groups. For the secondary outcome, symptom burden, we subtracted the total burden pre-intervention from the total burden post-intervention and then compared the difference in pre-post change between the two groups using a t-test. All analyses were conducted using Stata 14.2 for Windows (Statacorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the 44 participants who completed the intervention: 88.6% were over the age of 50 (mean age of 59.9, range 34–77); 22.7% were Black; 73.8% were married or in a long-term relationship; 27.5% had low health literacy; 36.4% had incomes of 150% or less of the federal poverty level (FPL); and 73.8% reported accessing the Internet daily. Further, 59.1% were Stage I at diagnosis, and 71.4% had a tumor grade of either low or intermediate. We found no statistical differences in characteristics between the two intervention groups.

Table 1

Baseline Characteristics

| Total | App+Reminder | App | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients N (%) | 44 (100.0) | 21 (47.7) | 23 (52.3) |

|

| |||

| Age | 59.9 | 60.6 | 59.3 |

18–49 18–49 | 11.4 | 9.5 | 13.0 |

50–65 50–65 | 56.8 | 52.4 | 60.9 |

Over 65 Over 65 | 31.8 | 38.1 | 26.1 |

|

| |||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

White White | 75.0 | 81.0 | 69.6 |

Black Black | 22.7 | 14.3 | 30.4 |

Hispanic Hispanic | 2.3 | 4.8 | 0.0 |

|

| |||

| Marital Status | |||

Single Single | 14.3 | 10.0 | 18.2 |

Married/Long-Term Married/Long-Term | 73.8 | 70.0 | 77.3 |

Divorced Divorced | 4.8 | 5.0 | 4.5 |

Widowed Widowed | 7.1 | 15.0 | 0.0 |

|

| |||

| Health Literacy† | |||

Lower Lower | 27.5 | 36.8 | 19.1 |

High High | 72.5 | 63.2 | 81.0 |

|

| |||

| Education | |||

No Degree No Degree | 5.0 | 10.5 | 0.0 |

HS Degree/Some College HS Degree/Some College | 55.0 | 47.4 | 61.9 |

4-year Degree or More 4-year Degree or More | 40.0 | 42.1 | 38.1 |

|

| |||

| Income (% FPL) | |||

Less than 150% Less than 150% | 36.4 | 23.5 | 50.0 |

150% to <400% 150% to <400% | 27.3 | 35.3 | 18.8 |

400% or More 400% or More | 36.4 | 41.2 | 31.2 |

|

| |||

| Freq. Internet Use | |||

Never/Rarely Never/Rarely | 9.5 | 15.0 | 4.6 |

Monthly Monthly | 2.4 | 0.0 | 4.6 |

Weekly Weekly | 14.3 | 15.0 | 13.6 |

Daily Daily | 73.8 | 70.0 | 77.2 |

|

| |||

| Stage at Diagnosis | |||

|

| |||

0 0 | 20.5 | 19.1 | 21.7 |

I I | 59.1 | 66.7 | 52.2 |

II II | 11.4 | 4.8 | 17.4 |

III III | 9.1 | 9.5 | 8.7 |

|

| |||

| Tumor Grade | |||

Low (G1) Low (G1) | 23.8 | 30.0 | 18.2 |

Intermediate (G2) Intermediate (G2) | 47.6 | 50.0 | 45.5 |

High (G3) High (G3) | 21.4 | 20.0 | 22.7 |

Other Other | 7.1 | 0.0 | 13.6 |

NOTE: No significant differences between App+Reminder and App groups (t-tests for group comparison)

App Use and Alerts

Table 2 shows app usage, number of alerts, and AI adherence at the end of the study. Overall, the mean app use rate was 55%. Participants in the App+Reminder had a higher proportion of logins per week enrolled compared to App group participants (73.5% vs. 37.6%, p<.05). Likewise, app-generated alerts were higher in the App+Reminder group compared with the App group (2.4 vs. 1.7, p<.05). The proportion of app use with weekly reminders per week enrolled was high among all participants in this group, especially among Blacks (90.4%), younger users (34–59 years old, 76.1%), and those with higher literacy levels (83.5%, Table 2). Most alerts (87%) had a documented call to the patient within 24 hours, and 95% within 48 hours.

Table 2

App Usage, App Alerts, and AI Adherence

| Total | App+Reminder | App | |

|---|---|---|---|

| App Usage and Alerts | |||

|

| |||

| App Use: % per week enrolled | 54.7 | 73.5 | 37.6* |

By Race By Race | |||

White White | 57.3 | 70.7 | 42.3* |

Black Black | 46.0 | 90.4 | 27.0* |

By Health Literacy By Health Literacy | |||

Lower Lower | 48.7 | 61.1 | 26.8 |

Higher Higher | 60.2 | 83.5 | 43.8* |

By Age By Age | |||

34–59 years 34–59 years | 50.1 | 76.1 | 29.9* |

60–77 years 60–77 years | 58.6 | 71.1 | 46.1 |

|

| |||

| App Alerts: Avg. counts | 2.0 | 2.4 | 1.7* |

|

| |||

| AI Adherence | |||

|

| |||

| MMAS-4 (%) | 86.1 | 100.0 | 72.7* |

By Race By Race | |||

White White | 90.9 | 100.0 | 80.0* |

Black Black | 70.0 | 100.0 | 57.1* |

| MMAS-4 – questions | |||

| Stop taking if you feel worse | 9.3 | 0.0 | 18.2* |

| Forget to take medicine | 7.0 | 0.0 | 13.6 |

| Problems remembering | 4.7 | 0.0 | 9.1 |

| Stop taking if you feel better | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

AI Adherence Measures

We found statistically significantly higher AI adherence in the App+Reminder group compared to the App group: 100% of App+Reminder group participants reported being fully adherent to the AI at the end of the study, compared with 72.7% of App participants (p<0.05). Among those reporting lower adherence (N=6), 66% (N=4) cited treatment-related adverse symptoms as a primary concern (Figure 3). Although not statistically significant, directional results within the App group show higher AI adherence among White versus Black participants (80.8% vs. 57.1%, p=0.284).

Change in Symptom Burden

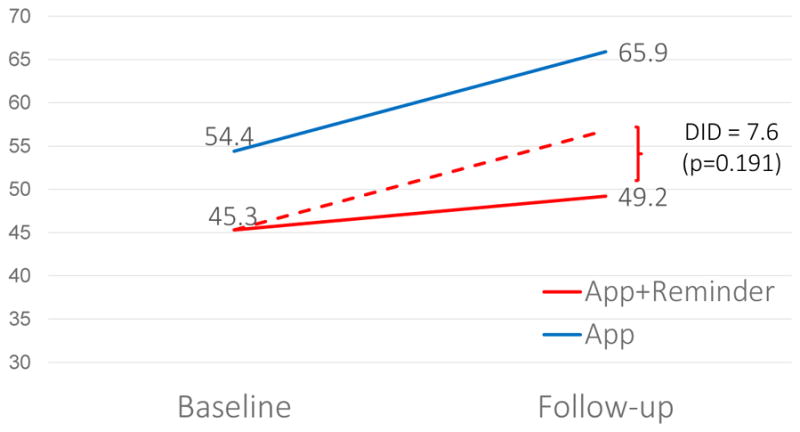

Note: The dotted line represents the expected change for App+Reminder participants if they had the same trajectory as App only participants. The difference-in-difference (DID) is equal to the difference from baseline to follow-up for the App group minus the difference from baseline to follow-up for the App+Reminder group.

Symptom Burden

While both groups experienced an increase in symptom burden after AI initiation, the increase was substantially larger (difference=7.6, p=0.191) in the App group compared with the App+Reminder group. Given our small sample size, this difference did not reach statistical significance (Figure 4).

Post-Intervention Feedback

To substantiate quantitative findings from the app intervention trial, we conducted phone interviews with five participants to learn more about their personal experiences with the intervention. All interview respondents reported being satisfied with weekly reminders and that more frequent reminders would have been burdensome. In addition, respondents reported that the app was easy to use and helpful to their treatment. In particular, they liked the convenience of being able report symptoms in real-time, not having to wait for an in-person visit, and the resultant outreach from their care team. For example, one participant said:

“It was beneficial - I actually used it for a symptom… I was having and the nurse called me back, right away … I wasn’t expecting that, so that was nice to have someone call to check on you, so I feel like it was beneficial for that reason and because I could do it in my own privacy, like, at home, you know, that was nice.”

Another participant said:

“I can go in and note my symptoms before I went to see the doctor and, so I wasn’t sitting in there and trying to fill it out really quickly on their iPad [clinic-based questionnaire]. I felt like if I could go to the apps and fill out my symptoms right away, I wouldn’t forget. Having to wait for three weeks or whatever to fill out my symptoms makes it hard to remember.”

Additionally, we queried participating physicians and nurses during biweekly study meetings and post-intervention feedback sessions about the time required to carry out the intervention and how well it fit into their clinical workflow in order to assess implementation feasibility. The nurses expressed that responding to alerts generated by the app did not add a lot of time to their daily routines or disrupt from other patients, saying, “It was the difference between getting a phone call and getting it [via the app].” They also expressed that the pilot intervention fit in very well with their workflow and resulted in more communication with patients, since many patients may not have made a phone call if they were experiencing symptoms. Lastly, the physicians involved expressed that the intervention had a minimal impact on their workflow, as their nurses were able to address most clinical alerts without their assistance.

DISCUSSION

Our study found that a web-based mobile app with weekly reminders for real-time reporting of AI adherence and treatment-related adverse symptoms was feasible and efficacious for improving short-term AI adherence among women with HR+ breast cancer. We assessed feasibility according to several factors, including participant recruitment and retention, improved AET adherence due to the intervention, and clinical implementation. Without the weekly reminders, use of the app was lower, particularly for participants who were Black, younger, and had lower literacy levels—arguably patient populations for whom AI adherence interventions are necessary (Table 2). Although not statistically significant, directional results suggest that the App+Reminder group had smaller increases in symptom burden relative to those in the App group after starting the AI, suggesting that they may have received better and more timely symptom management as a result of the app-based real-time reports. If short-term gains in adherence persist, this low-cost intervention with few, if any, clinical barriers to implementation could improve quality of life and survival outcomes for women with HR+ breast cancer.

We recruited a large proportion of underserved patients, including many with lower income and education, usually underrepresented in clinical trial for cancer care [31]. Moreover, our trial was set in a region recently found to have the highest racial disparity in breast cancer survival rates in the country [44]. More than a third of participants had incomes below 150% FPL, a quarter reported lower health literacy, and nearly two-thirds did not have a 4-year college degree. Using weekly reminders, we were able to achieve a high level of use across a diverse group of patients, including those with lower health literacy (61.1% used at least once per week), and older participants, ages 60–77 (71.1% used at least once per week, Table 2).

Although early detection and new treatments have improved breast cancer survival rates overall, Black-White disparities in breast cancer mortality continue to widen, and as of 2012, Black women living in the South had significantly higher incidence of breast cancer compared to White women [1, 44]. Importantly, for Black women [45–47], the majority of newly diagnosed breast cancers (70%) are HR+ [48], and the death rate for Black women with HR+ cancers is double that of White women [3]. Differences in AET treatment adherence may offer one explanation for this growing disparity; observational studies have found significant underuse [49] and lower adherence [5, 50] to AET among Black women when compared to White women. Lower adherence among Black women [5, 50] may be contributing to the large and growing disparities in mortality outcomes. Our small trial found that the App+Reminder intervention resulted in high app use among Black and White patients and was similarly effective in improving AI adherence. Interventions that can improve AET adherence overall, and reduce disparities in adherence, could have clinically meaningful implications for survival and racial disparities in cancer survival outcomes.

Patients and providers who participated in the trial conveyed a positive experience with the study app, citing that it was beneficial to providing and receiving care. Patients found the weekly reminders helpful and the ability to report real-time AI use and symptoms beneficial for several reasons, including: receipt of timely calls from nurses to promptly address concerning symptoms, convenience of reporting symptoms at any time from their home, not having to remember symptoms for several weeks before reporting them at their next appointment, and not having to decide whether or not to call the clinic to report the symptom. The clinic staff stated that participating in the intervention had minimal impact on their clinical workflow and likely increased communication with patients who were experiencing concerning treatment-related adverse symptoms but may not have called the clinic for advice. These findings suggest that this patient-centered intervention has the potential to be widely disseminated without adversely affecting providers’ clinical workflow or overburdening clinic staff.

Our pilot trial had some limitations. First, since it was a small pilot trial, it was not powered to detect statistically significant differences in the study outcomes; instead, it was designed to assess the feasibility and short-term effect of a web-based app in the context of a busy cancer center and detect trends in the treatment-related outcomes. Nonetheless, we still found large, statistically significant differences in reported AI adherence. Second, we only followed participants for up to eight weeks, so it is unknown whether initial gains in adherence translate into long-term, higher adherence. However, previous research suggests that short-term medication adherence is highly associated with long-term adherence [51]. Third, due to cost limitations, we measured adherence using self-reports, which have been found to be less reliable than electronic monitoring systems or pill counts [12, 52–54]. Nonetheless, our measure of adherence is widely used, validated, and captured consistently across both study groups. Lastly, we recruited patients from a single clinic and required participants to have access to the Ihnternet, either via a computer or mobile device, which limits the generalizability of findings. An additional limitation impacting generalizability is that patients who are unable to communicate in English were excluded from the study. While non-English speaking patients could also potentially benefit from the app, for this initial trial, we only developed English versions of the surveys and app.

CONCLUSION

We found that use of a web-enabled app with weekly reminders significantly improved short-term AI adherence. The high penetration of web-enabled devices, including smartphones, can be leveraged by the healthcare community as a way to further engage patients between visits in order to improve care quality and health outcomes. Our results suggest that the ability of healthcare providers to monitor symptom reports via an app with reminders to engage in treatment-related communication with patients outside of clinic visits could provide a wide-reaching and cost-effective way to improve symptom management, medication adherence, and ultimately health outcomes. Future studies should test if short-term gains in AI adherence can be maintained over the full treatment period (typically 5–10 years), and if improved adherence is associated with clinically meaningful improvements in health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The corresponding author, Ilana Graetz states that she had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Funding: This study was funded by the University of Tennessee Health Science Center Clinical and Translational Science Institute and the National Cancer Institute (R01CA218155). The funding agencies had no role in the design and conduct of the study.

Appendix A

Table A1

Summary of Measures

| Baseline | Follow-up | App | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aromatase Inhibitor Adherence | |||

MMAS-4 MMAS-4 | x | ||

MARS-1 MARS-1 | x | x | |

| Symptoms and severity | x | ||

| Symptom Burden (FACT-ES) | x | x | |

| Participant characteristics | x | ||

Note: MMAS-4 refers to the four-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale and MARS-1 to the single-item adherence measure from the Medication Adherence Reasons.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest: Drs. Graetz, Anderson, and McKillop declare that they have no conflict of interest. Drs. Stepanski and Schwartzberg own stock in Vector Oncology. Dr. Vidal received a speaker honorarium from Pfizer Inc. and AstraZeneca.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-018-0682-z

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc6054536?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

Factors influencing 5-year persistence to adjuvant endocrine therapy in young women with breast cancer.

Breast, 77:103765, 04 Jul 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39002281 | PMCID: PMC11301370

Functional and Nonfunctional Requirements of Virtual Clinic Mobile Applications: A Systematic Review.

Int J Telemed Appl, 2024:7800321, 11 Jun 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38899062 | PMCID: PMC11186682

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Effectiveness of mHealth apps on adherence and symptoms to oral anticancer medications: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Support Care Cancer, 32(7):426, 12 Jun 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38864924

Review

Remote Monitoring App for Endocrine Therapy Adherence Among Patients With Early-Stage Breast Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial.

JAMA Netw Open, 7(6):e2417873, 03 Jun 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38935379

A scoping review of web-based, interactive, personalized decision-making tools available to support breast cancer treatment and survivorship care.

J Cancer Surviv, 28 Mar 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38538922

Review

Go to all (46) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Clinical Trials

- (1 citation) ClinicalTrials.gov - NCT02957526

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

THRIVE study protocol: a randomized controlled trial evaluating a web-based app and tailored messages to improve adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy among women with breast cancer.

BMC Health Serv Res, 19(1):977, 19 Dec 2019

Cited by: 11 articles | PMID: 31856812 | PMCID: PMC6924011

Perceived barriers to treatment predict adherence to aromatase inhibitors among breast cancer survivors.

Cancer, 123(1):169-176, 29 Aug 2016

Cited by: 24 articles | PMID: 27570979 | PMCID: PMC5161545

Remote Monitoring App for Endocrine Therapy Adherence Among Patients With Early-Stage Breast Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial.

JAMA Netw Open, 7(6):e2417873, 03 Jun 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38935379

Interventions to improve endocrine therapy adherence in breast cancer survivors: what is the evidence?

J Cancer Surviv, 12(3):348-356, 02 Feb 2018

Cited by: 36 articles | PMID: 29396760

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NCI NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: R01 CA218155

National Cancer Institute (1)

Grant ID: R01CA218155