Abstract

Background

Current clinical definitions of diabetes require repeated blood work to confirm elevated levels of glucose or hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) to reduce the possibility of a false-positive diagnosis. Whether 2 different tests from a single blood sample provide adequate confirmation is uncertain.Objective

To examine the prognostic performance of a single-sample confirmatory definition of undiagnosed diabetes.Design

Prospective cohort study.Setting

The ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities) study.Participants

13 346 ARIC participants (12 268 without diagnosed diabetes) with 25 years of follow-up for incident diabetes, cardiovascular outcomes, kidney disease, and mortality.Measurements

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes was defined as elevated levels of fasting glucose (≥7.0 mmol/L [≥126 mg/dL]) and HbA1c (≥6.5%) from a single blood sample.Results

Among 12 268 participants without diagnosed diabetes, 978 had elevated levels of fasting glucose or HbA1c at baseline (1990 to 1992). Among these, 39% had both (confirmed undiagnosed diabetes), whereas 61% had only 1 elevated measure (unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes). The confirmatory definition had moderate sensitivity (54.9%) but high specificity (98.1%) for identification of diabetes cases diagnosed during the first 5 years of follow-up, with specificity increasing to 99.6% by 15 years. The 15-year positive predictive value was 88.7% compared with 71.1% for unconfirmed cases. Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes was significantly associated with cardiovascular and kidney disease and mortality, with stronger associations than unconfirmed diabetes.Limitation

Lack of repeated measurements of fasting glucose and HbA1c.Conclusion

A single-sample confirmatory definition of diabetes had a high positive predictive value for subsequent diagnosis and was strongly associated with clinical end points. Our results support the clinical utility of using a combination of elevated fasting glucose and HbA1c levels from a single blood sample to identify undiagnosed diabetes in the population.Primary funding source

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.Free full text

Prognostic Implications of Single-Sample Confirmatory Testing for Undiagnosed Diabetes: A Prospective Cohort Study

Abstract

Background

Current clinical definitions of diabetes require repeated blood work to confirm elevated levels of glucose or hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) to reduce the possibility of a false-positive diagnosis. Whether 2 different tests from a single blood sample provide adequate confirmation is uncertain.

Objective

To examine the prognostic performance of a single-sample confirmatory definition of undiagnosed diabetes.

Design

Cohort study.

Setting

The ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities) study.

Participants

13 346 ARIC participants (12 268 without diagnosed diabetes) with 25 years of follow-up for incident diabetes, cardiovascular outcomes, kidney disease, and mortality.

Measurements

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes was defined as elevated levels of fasting glucose (≥7.0 mmol/L [≥126 mg/dL]) and HbA1c (≥6.5%) from a single blood sample.

Results

Among 12 268 participants without diagnosed diabetes, 978 had elevated levels of fasting glucose or HbA1c at baseline (1990 to 1992). Among these, 39% had both (confirmed undiagnosed diabetes), whereas 61% had only 1 elevated measure (unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes). The confirmatory definition had moderate sensitivity (54.9%) but high specificity (98.1%) for identification of diabetes cases diagnosed during the first 5 years of follow-up, with specificity increasing to 99.6% by 15 years. The 15-year positive predictive value was 88.7% compared with 71.1% for unconfirmed cases. Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes was significantly associated with cardiovascular and kidney disease and mortality, with stronger associations than unconfirmed diabetes.

Limitation

Lack of repeated measurements of fasting glucose and HbA1c.

Conclusion

A single-sample confirmatory definition of diabetes had a high positive predictive value for subsequent diagnosis and was strongly associated with clinical end points. Our results support the clinical utility of using a combination of elevated fasting glucose and HbA1c levels from a single blood sample to identify undiagnosed diabetes in the population.

Primary Funding Source

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Glucose measurement has long been the customary diagnostic test for diabetes mellitus. Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) measurement has been the standard test for monitoring of long-term glycemic control in the setting of diagnosed diabetes but was not recommended as a diagnostic test until 2009 (1, 2). The recommendation for use of HbA1c measurement as a diagnostic test was a major change in diabetes clinical practice guidelines. A diagnostic cut point for HbA1c of 6.5% was chosen for its high specificity (2) and on the basis of data showing associations with prevalent retinopathy above that threshold (3).

Current clinical definitions of diabetes require repeated testing to confirm elevated levels of glucose or HbA1c to reduce the possibility of a false-positive diagnosis. Guidelines from the American Diabetes Association state that repeating the same test in a new blood sample at a different time to confirm the diagnosis is preferred (4) but that results of 2 different biochemical tests exceeding diagnostic thresholds can also provide confirmation. It is common clinical practice for 2 different tests (for example, fasting glucose and HbA1c measurement) to be done with the same blood sample, but whether this can provide adequate confirmation is uncertain.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the prognostic performance of a single-sample confirmatory definition of undiagnosed diabetes. Specifically, we examined the diagnostic performance of definitions of confirmed undiagnosed diabetes (elevated fasting glucose and HbA1c levels) and unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes (elevated fasting glucose or HbA1c level) to identify future cases of diagnosed diabetes. We also evaluated the absolute risk and relative risk associations of the single-sample confirmatory definition with subsequent development of chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular disease (coronary heart disease, stroke, or heart failure), peripheral artery disease, and all-cause mortality during more than 25 years of follow-up of participants in the community-based ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities) study.

Methods

Study Population

We conducted a prospective cohort analysis of participants in the ARIC study, an ongoing community-based cohort study of 15 792 persons who were initially enrolled during 1987 to 1989 from 4 U.S. communities (Forsyth County, North Carolina; Jackson, Mississippi; suburban Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Washington County, Maryland). We used ARIC visit 2 in 1990 to 1992 as baseline for the present study because this was the first time point with HbA1c measurements. Institutional review boards at each study site reviewed the study protocols, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

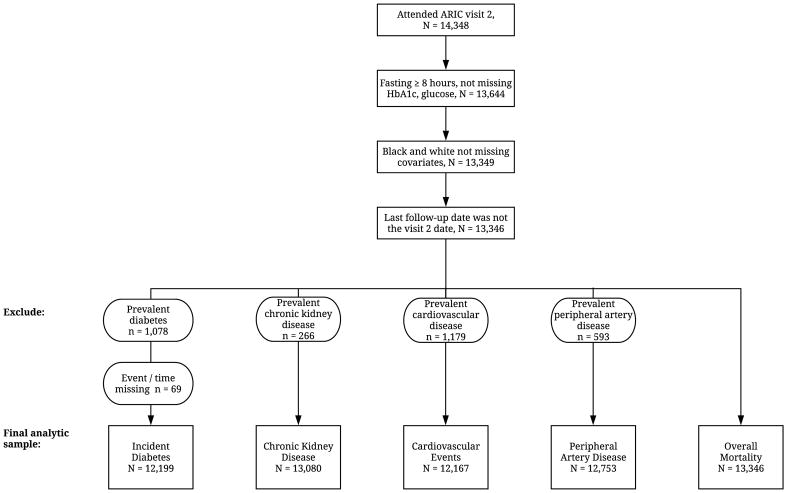

Among the 14 348 participants who attended visit 2, we excluded those who had been fasting for less than 8 hours or were missing HbA1c or glucose measurements (n = 704). In the ARIC study, white participants were recruited at the Minnesota and Maryland sites, black participants were recruited at the Mississippi site, and the North Carolina site recruited a mix of black and white participants. For the present study, we excluded nonwhite participants at the Minnesota and Maryland sites (n = 49) and participants from all field centers whose recorded race/ethnicity was not black or white (n = 40). In all analyses, we also excluded participants who were missing other variables of interest at the ARIC visit 2 examination (n = 206) and those whose last contact date was the same as their visit 2 examination date (n = 3). Thus, our analyses of all-cause mortality included 13 346 participants. Persons with prevalent disease or missing outcome data were excluded from analyses of those conditions (Appendix Figure 1, available at Annals.org). In the analyses of incident diabetes, we further excluded participants who had diagnosed diabetes at baseline or were missing information on diabetes status during follow-up, resulting in a sample size of 12 199 for this outcome.

Diabetes Definitions

Prevalent diagnosed diabetes was defined as self-reported physician diagnosis or current glucose-lowering medication use at visit 1 or 2. Glucose was measured using the hexokinase method. Hemoglobin A1c was measured in stored whole blood samples by using high-performance liquid chromatography methods certified by the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program and aligned to the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial assay (5). Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes was defined as elevations in HbA1c level (≥6.5%) and fasting glucose level (≥7.0 mmol/L [≥126 mg/dL]) among persons without diagnosed diabetes. Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes was defined as no diagnosis of diabetes and only 1 elevated measure. We examined the unconfirmed cases together and also separately (isolated fasting glucose elevation and isolated HbA1c elevation).

Outcomes

Incident diagnosed diabetes was defined on the basis of self-reported use of glucose-lowering medication or report of a physician diagnosis of diabetes at a subsequent visit or during annual telephone calls to all participants (6).

Incident chronic kidney disease was defined as either estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and a decrease in eGFR from baseline of at least 25% (estimated using the 2009 Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation and serum creatinine level at visit 4 during 1996 to 1998) or hospitalization or death due to kidney disease identified during continuous active surveillance (7).

Incident cardiovascular disease was a composite outcome defined as the first occurrence of coronary heart disease, stroke, or heart failure. This included any validated definite or probable hospitalization for myocardial infarction, death due to coronary heart disease, silent myocardial infarction detected at visit 3 or 4, a validated stroke event, or hospitalization or death due to heart failure (heart failure events after 2004 were adjudicated by an end point committee) (8–13). Incident peripheral artery disease was defined as the first hospitalization related to peripheral artery disease (14). Deaths were identified from state records and linkage to the National Death Index.

Participants were followed until the incident event, the date of last contact, or 31 December 2015 (whichever came first) in analyses of incident diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and mortality. Follow-up was available through 31 December 2014 for peripheral artery disease and through 31 December 2013 for chronic kidney disease.

Other Variables

Measurements were obtained at visit 2 (1990 to 1992), except for education, which was self-reported at visit 1 (1987 to 1989) and categorized as less than high school, high school or equivalent, or college or above. Body mass index was calculated as measured weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Smoking and drinking status were self-reported and categorized as never, former, or current. Total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglyceride levels were measured using standard methods (15–17). Systolic and diastolic blood pressures were measured according to a standardized protocol (18), and we calculated the mean of the second and third of 3 measurements. Hypertension was defined as mean systolic blood pressure of 140 mm Hg or greater, mean diastolic blood pressure of 90 mm Hg or greater, or current use of blood pressure–lowering medications. Parental history of diabetes was self-reported.

Statistical Analysis

We examined baseline characteristics of participants by diabetes status (diagnosed, confirmed undiagnosed, unconfirmed undiagnosed, and no diabetes) and evaluated the concordance of HbA1c and fasting glucose levels in persons with no history of diabetes by using a scatter plot and calculating measures of agreement.

We evaluated the diagnostic performance of confirmed undiagnosed diabetes to identify incident cases of diagnosed diabetes during 5, 10, and 15 years of follow-up. In the diagnostic performance analyses, we compared the confirmed definition to a combined group that included both unconfirmed and confirmed diabetes diagnoses. This approach is taken because in a binary screening scenario which classifies unconfirmed cases as positives, confirmed cases would also inevitably be considered positive cases. We calculated the crude incidence rates per 1000 person-years and adjusted 5-, 10-, and 15-year cumulative incidence (risk) estimates for incident diagnosed diabetes and the other clinical end points (19), and we used Cox proportional hazards regression models to evaluate the prospective associations with each outcome. These analyses compared the mutually exclusive categories of diagnosed diabetes, confirmed undiagnosed diabetes, unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes, and no diabetes. The proportional hazards assumption was evaluated and confirmed using log-log plots and testing for interactions between risk factors and time. We adjusted for age, sex, and 5 categories of race–center (Minnesota white participants, Maryland white participants, Mississippi black participants, North Carolina white participants, and North Carolina black participants) (model 1). In secondary analyses, we also adjusted for body mass index, education, smoking status, drinking status, total and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, triglyceride level, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, current use of blood pressure–lowering medication, parental history of diabetes, and eGFR (modeled using a linear spline with a knot at 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) (model 2). Persons without diabetes served as the reference group. We tested for differences in hazard ratios (HRs) between the unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes and confirmed undiagnosed diabetes groups using the Wald test and tested for interaction by race and race–center using the likelihood ratio test. We also conducted sensitivity analyses in which we divided the unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes group into persons with isolated fasting glucose elevation (≥126 mg/dL) or isolated HbA1c elevation (≥6.5%) to examine absolute risk and relative risk associations.

All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata/SE, version 15.0 (StataCorp). We used the Stata survci command to generate the covariate-adjusted cumulative incidence estimates and corresponding CIs (20). A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Role of the Funding Source

The funding source had no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Results

There were 978 persons with elevated fasting glucose level or elevated HbA1c level at baseline, among whom 39% had confirmed undiagnosed diabetes and 61% had unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes. In general, persons with confirmed undiagnosed diabetes had higher prevalence of risk factors for diabetes and cardiovascular disease than those with unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes (Table 1). With respect to risk factors, the confirmed group was generally most similar to the diagnosed diabetes group and had the highest prevalence of obesity (body mass index ≥30 kg/m2) (64.5% vs. 51.0% in the diagnosed diabetes group and 46.6% in the unconfirmed group).

Table 1

Characteristics of Participants at ARIC Study Visit 2 (1990–1992), by Diabetes Status (n = 13 346)

| Characteristic | No Diabetes (n = 11 290)* | Unconfirmed Undiagnosed Diabetes (n = 595)† | Confirmed Undiagnosed Diabetes (n = 383)‡ | Diagnosed Diabetes (n = 1078)§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD), y | 56.8 (5.7) | 57.7 (5.6) | 57.6 (5.8) | 58.5 (5.7) |

|

| ||||

| Female, % | 56.0 | 49.7 | 57.2 | 56.2 |

|

| ||||

| Black, % | 20.1 | 35.3 | 45.4 | 39.2 |

|

| ||||

| Race–center, % | ||||

Minnesota white participants Minnesota white participants | 28.9 | 24.4 | 14.1 | 14.7 |

|

| ||||

Mississippi black participants Mississippi black participants | 17.9 | 31.3 | 40.7 | 35.7 |

|

| ||||

Maryland white participants Maryland white participants | 26.7 | 23.4 | 25.3 | 28.6 |

|

| ||||

North Carolina black participants North Carolina black participants | 2.2 | 4.0 | 4.7 | 3.5 |

|

| ||||

North Carolina white participants North Carolina white participants | 24.3 | 17.0 | 15.1 | 17.4 |

| Body mass index category, % | ||||

|

| ||||

Normal weight (<25 kg/m2) Normal weight (<25 kg/m2) | 34.7 | 12.3 | 6.0 | 14.8 |

|

| ||||

Overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2) Overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2) | 40.9 | 41.2 | 29.5 | 34.1 |

|

| ||||

Obese (≥30 kg/m2) Obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 24.3 | 46.6 | 64.5 | 51.0 |

|

| ||||

| Education level, % | ||||

Less than high school Less than high school | 7.1 | 10.6 | 12.8 | 16.0 |

|

| ||||

High school or equivalent High school or equivalent | 43.8 | 49.4 | 46.2 | 47.6 |

|

| ||||

College or above College or above | 49.0 | 40.0 | 41.0 | 36.4 |

| Smoking status, % | ||||

|

| ||||

Never Never | 39.8 | 34.8 | 42.6 | 43.2 |

|

| ||||

Former Former | 38.0 | 43.2 | 36.0 | 37.4 |

|

| ||||

Current Current | 22.3 | 22.0 | 21.4 | 19.4 |

|

| ||||

| Drinking status, % | ||||

Never Never | 21.4 | 20.8 | 30.3 | 30.3 |

|

| ||||

Former Former | 18.8 | 24.7 | 27.4 | 35.0 |

|

| ||||

Current Current | 59.7 | 54.5 | 42.3 | 34.7 |

|

| ||||

| Mean total cholesterol level (SD) | ||||

mmol/L mmol/L | 5.4 (1.0) | 5.5 (1.1) | 5.7 (1.1) | 5.6 (1.2) |

mg/dL mg/dL | 209.1 (38.3) | 213.4 (41.7) | 218.4 (43.7) | 215.2 (46.7) |

|

| ||||

| Mean high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level (SD) | ||||

mmol/L mmol/L | 1.3 (0.4) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.1 (0.3) | 1.1 (0.4) |

mg/dL mg/dL | 50.7 (16.8) | 44.8 (15.0) | 41.7 (12.6) | 43.0 (14.0) |

|

| ||||

| Mean triglyceride level (SD) | ||||

mmol/L mmol/L | 1.4 (0.9) | 1.8 (1.3) | 2.0 (1.3) | 2.1 (1.7) |

mg/dL mg/dL | 127.8 (76.3) | 163.2 (114.7) | 177.6 (114.2) | 183.7 (151.0) |

|

| ||||

| Hypertension, % | 31.4 | 55.3 | 57.2 | 59.3 |

|

| ||||

| Mean systolic blood pressure (SD), mm Hg | 120.2 (18.3) | 127.8 (19.7) | 128.7 (17.3) | 127.8 (20.0) |

|

| ||||

| Mean diastolic blood pressure (SD), mm Hg | 72.0 (10.2) | 74.4 (10.9) | 74.5 (10.2) | 71.4 (10.2) |

|

| ||||

| eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, % | 1.6 | 2.2 | 2.6 | 5.6 |

|

| ||||

| Family history of diabetes, % | 21.7 | 30.4 | 37.6 | 41.7 |

ARIC = Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; HbA1c = hemoglobin A1c.

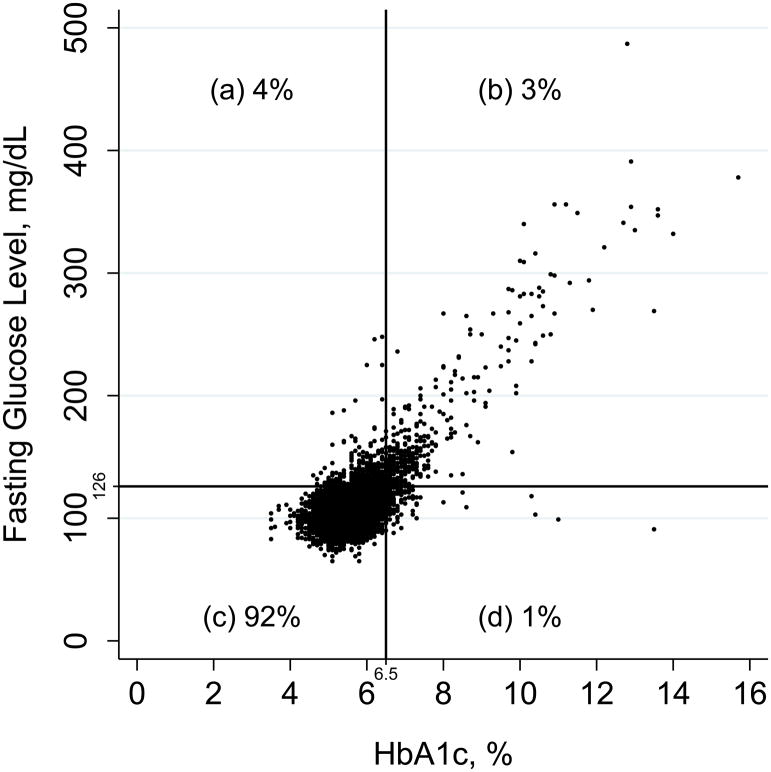

The scatter plot of HbA1c and fasting glucose levels in persons with no history of diagnosed diabetes is shown in Appendix Figure 2 (available at Annals.org). The overall percent agreement across diagnostic categories was 95%, with a positive percent agreement of 37.5%. Of note, isolated fasting glucose elevation (≥126 mg/dL) was 4 times more common (4% of the population) than isolated HbA1c elevation (≥6.5%) (1% of the population).

Scatter plot of HbA1c and fasting glucose levels in persons with no history of diagnosed diabetes who attended ARIC visit 2 (1990 to 1992). The figure is divided into 4 quadrants (a, b, c, and d) according to diagnostic cut points for fasting glucose and HbA1c levels. On the basis of the number of persons in these quadrants, the overall percent agreement is 95%, defined as 100% × ([b + c]/[a + b + c + d]). The positive percent agreement is 37.5%, defined as 100% × (b/[a + b + d]). The Pearson correlation coefficient is 0.72; the Spearman correlation coefficient is 0.43. ARIC = Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities; HbA1c = hemoglobin A1c.

The confirmed definition of undiagnosed diabetes had high specificity to identify cases of diabetes diagnosed during follow-up (98.1% at 5 years and 99.6% at 15 years) (Table 2). The confirmed definition had lower sensitivity than the combined group of unconfirmed and confirmed cases, although both had low sensitivity to identify future cases of diabetes after many years of follow-up. At 5 years, the positive predictive value of the confirmed definition was moderate (39.7%) but was higher than that for the combined unconfirmed and confirmed group (21.0%). By 15 years, the positive predictive value for the confirmed definition was 88.7% compared with only 71.1% for unconfirmed or confirmed cases. The negative predictive value was high for both.

Table 2

Diagnostic Performance of Confirmed and Unconfirmed Definitions of Undiagnosed Diabetes at ARIC Study Visit 2 (1990–1992) to Identify Cases of Diagnosed Diabetes at 5, 10, and 15 Years of Follow-up (n = 12 199)*

| Diabetes Status During Follow-up, n | Diagnostic Performance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Developed Diagnosed Diabetes | No Diagnosed Diabetes | Sensitivity (95% CI), % | Specificity (95% CI), % | Positive Predictive Value (95% CI), % | Negative Predictive Value (95% CI), % | |

| 5 y | ||||||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | ||||||

|

| ||||||

Yes Yes | 151 | 229 | 54.9 (48.8–60.9) | 98.1 (97.8–98.3) | 39.7 (34.8–44.9) | 99.0 (98.8–99.1) |

|

| ||||||

No No | 124 | 11 695 | – | – | – | – |

Unconfirmed and confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Unconfirmed and confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | ||||||

|

| ||||||

Yes Yes | 205 | 770 | 74.5 (69.0–79.6) | 93.5 (93.1–94.0) | 21.0 (18.5–23.7) | 99.4 (99.2–99.5) |

|

| ||||||

No No | 70 | 11 154 | – | – | – | – |

| 10 y | ||||||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | ||||||

|

| ||||||

Yes Yes | 318 | 62 | 22.9 (20.7–25.2) | 99.4 (99.3–99.6) | 83.7 (79.6–87.3) | 90.9 (90.4–91.4) |

|

| ||||||

No No | 1073 | 10 746 | – | – | – | – |

Unconfirmed and confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Unconfirmed and confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | ||||||

|

| ||||||

Yes Yes | 571 | 404 | 41.0 (38.4–43.7) | 96.3 (95.9–96.6) | 58.6 (55.4–61.7) | 92.7 (92.2–93.2) |

|

| ||||||

No No | 820 | 10 404 | – | – | – | – |

| 15 y | ||||||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | ||||||

|

| ||||||

Yes Yes | 337 | 43 | 13.5 (12.2–14.9) | 99.6 (99.4–99.7) | 88.7 (85.1–91.7) | 81.8 (81.1–82.5) |

|

| ||||||

No No | 2153 | 9666 | – | – | – | – |

Unconfirmed and confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Unconfirmed and confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | ||||||

|

| ||||||

Yes Yes | 693 | 282 | 27.8 (26.1–29.6) | 97.1 (96.7–97.4) | 71.1 (68.1–73.9) | 84.0 (83.3–84.7) |

|

| ||||||

No No | 1797 | 9427 | – | – | – | – |

ARIC = Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities; HbA1c = hemoglobin A1c.

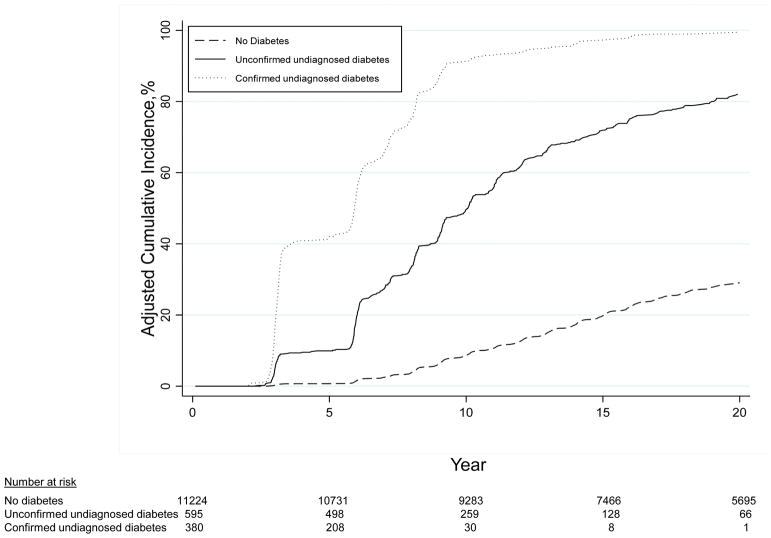

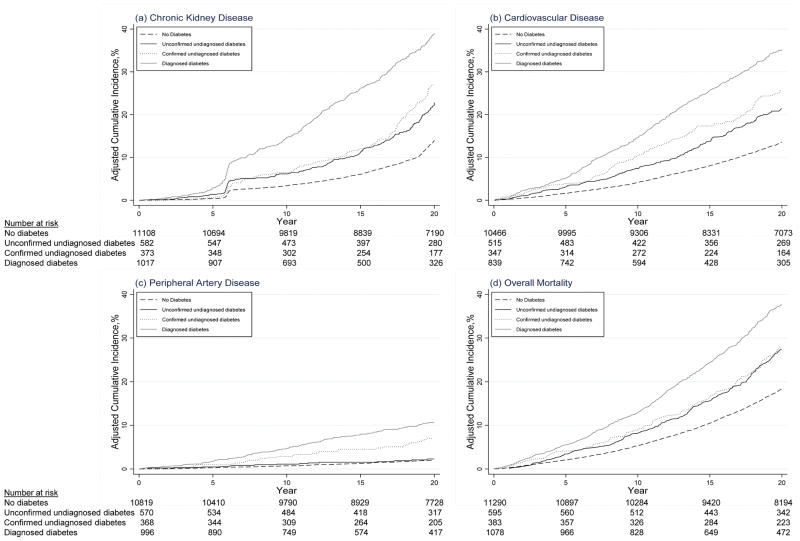

Consistent with the high positive predictive value, the adjusted cumulative incidence (risk) of diagnosed diabetes in the confirmed undiagnosed group was 42.0% at 5 years and 97.3% at 15 years (Table 3). In contrast, the unconfirmed undiagnosed group had an adjusted cumulative incidence of only 9.9% at 5 years and 71.7% at 15 years. By 20 years, the adjusted cumulative incidence among persons with confirmed undiagnosed diabetes at baseline was nearly 100% (Figure 1). This definition was also associated with high incidence rates and adjusted cumulative incidence of chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, peripheral artery disease, and mortality (Table 3 and Figure 2). Similar patterns were observed with additional adjustment for diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors (Appendix Table 1, available at Annals.org).

Cumulative incidence of diagnosed diabetes after ARIC visit 2 (1990 to 1992), adjusted for age, sex, and race–center. ARIC = Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities.

Cumulative incidence of chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, peripheral artery disease, and all-cause mortality after ARIC visit 2 (1990 to 1992), adjusted for age, sex, and race–center. ARIC = Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities.

Table 3

Incidence Rates per 1000 Person-Years and Adjusted 5-, 10-, and 15-Year Cumulative Incidence (Risk) for Major Clinical Outcomes, by Baseline Diabetes Status at ARIC Study Visit 2 (1990–1992)*

| Incidence Rate per 1000 Person-Years (95% CI) | Adjusted Cumulative Incidence (95% CI), %† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| 5 y | 10 y | 15 y | ||

| Incident diagnosed diabetes | ||||

|

| ||||

No diabetes No diabetes | 14.8 (14.3–15.4) | 0.7 (0.6–0.9) | 8.7 (8.0–9.5) | 19.8 (18.5–21.2) |

|

| ||||

Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 65.4 (59.3–72.1) | 9.9 (7.6–12.9) | 49.5 (44.7–54.5) | 71.7 (67.0–76.3) |

|

| ||||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 156.8 (141.1–174.3) | 42.0 (36.8–47.7) | 91.1 (87.3–94.1) | 97.3 (94.9–98.7) |

|

| ||||

| Chronic kidney disease | ||||

No diabetes No diabetes | 12.7 (12.3–13.2) | 0.4 (0.3–0.5) | 3.4 (3.0–3.8) | 6.1 (5.5–6.7) |

|

| ||||

Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 19.1 (16.6–22.0) | 1.4 (0.7–2.5) | 6.2 (4.6–8.3) | 11.1 (8.9–14.0) |

|

| ||||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 21.4 (18.1–25.4) | 0.7 (0.2–2.0) | 6.5 (4.5–9.3) | 12.2 (9.3–16.0) |

|

| ||||

Diagnosed diabetes Diagnosed diabetes | 31.6 (28.8–34.6) | 2.8 (2.1–3.9) | 14.4 (12.4–16.8) | 26.1 (23.2–29.3) |

|

| ||||

| Cardiovascular disease | ||||

No diabetes No diabetes | 10.0 (9.6–10.5) | 1.6 (1.4–1.9) | 4.2 (3.7–4.6) | 8.1 (7.4–8.8) |

|

| ||||

Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 15.8 (13.4–18.5) | 3.1 (2.0–4.5) | 7.5 (5.7–9.7) | 13.8 (11.2–16.8) |

|

| ||||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 19.7 (16.5–23.5) | 3.9 (2.6–6.0) | 10.4 (7.9–13.5) | 17.4 (14.1–21.3) |

|

| ||||

Diagnosed diabetes Diagnosed diabetes | 26.3 (23.8–29.1) | 5.1 (4.0–6.5) | 14.6 (12.6–17.0) | 25.7 (22.8–28.9) |

|

| ||||

| Peripheral artery disease | ||||

No diabetes No diabetes | 1.4 (1.3–1.6) | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | 0.7 (0.6–0.9) | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) |

|

| ||||

Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 1.9 (1.2–3.0) | 0.5 (0.2–1.3) | 1.1 (0.6–2.2) | 1.5 (0.8–2.8) |

|

| ||||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 5.1 (3.7–7.2) | 1.0 (0.4–2.4) | 2.9 (1.6–4.9) | 4.5 (2.9–7.1) |

|

| ||||

Diagnosed diabetes Diagnosed diabetes | 8.2 (6.9–9.8) | 1.7 (1.1–2.7) | 4.7 (3.4–6.3) | 8.0 (6.1–10.4) |

|

| ||||

| All-cause mortality | ||||

No diabetes No diabetes | 17.5 (17.0–18.0) | 2.1 (1.9–2.3) | 5.4 (4.9–5.8) | 10.5 (9.8–11.2) |

|

| ||||

Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 26.9 (24.0–30.1) | 3.4 (2.5–4.8) | 8.1 (6.5–10.0) | 15.5 (13.2–18.2) |

|

| ||||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 30.1 (26.3–34.4) | 4.0 (2.7–5.9) | 8.8 (6.8–11.4) | 16.4 (13.5–19.8) |

|

| ||||

Diagnosed diabetes Diagnosed diabetes | 41.8 (38.9–44.9) | 5.5 (4.5–6.7) | 12.9 (11.3–14.7) | 24.3 (22.0–26.8) |

ARIC = Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities; HbA1c = hemoglobin A1c.

Appendix Table 1

Multivariable-Adjusted 5-, 10- and 15-Year Cumulative Incidence (Risk) for Major Clinical Outcomes, by Baseline Diabetes Status at ARIC Study Visit 2 (1990–1992)*

| Adjusted Cumulative Incidence (95% CI), %† | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 5 y | 10 y | 15 y | |

| Incident diagnosed diabetes | |||

|

| |||

No diabetes No diabetes | 0.5 (0.4–0.6) | 6.3 (5.6–7.0) | 14.9 (13.6–16.5) |

|

| |||

Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 5.5 (4.1–7.2) | 32.9 (28.6–37.5) | 54.1 (48.6–59.8) |

|

| |||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 24.5 (20.7–29.0) | 74.0 (67.4–80.1) | 88.4 (82.2–93.3) |

|

| |||

| Chronic kidney disease | |||

No diabetes No diabetes | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) | 2.2 (1.9–2.5) | 4.0 (3.6–4.6) |

|

| |||

Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 0.7 (0.4–1.4) | 3.4 (2.5–4.6) | 6.4 (5.0–8.2) |

|

| |||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 0.4 (0.1–1.1) | 3.8 (2.6–5.6) | 7.5 (5.6–10.0) |

|

| |||

Diagnosed diabetes Diagnosed diabetes | 1.5 (1.0–2.1) | 8.3 (6.9–9.9) | 16.1 (13.8–18.8) |

|

| |||

| Cardiovascular disease | |||

No diabetes No diabetes | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 2.7 (2.4–3.1) | 5.5 (4.9–6.2) |

|

| |||

Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 1.7 (1.1–2.5) | 4.3 (3.2–5.6) | 8.1 (6.5–10.1) |

|

| |||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 2.1 (1.4–3.3) | 5.9 (4.4–7.8) | 10.2 (8.0–12.9) |

|

| |||

Diagnosed diabetes Diagnosed diabetes | 2.5 (1.9–3.3) | 7.9 (6.6–9.6) | 15.2 (13.0–17.8) |

|

| |||

| Peripheral artery disease | |||

No diabetes No diabetes | 0.2 (0.1–0.2) | 0.4 (0.3–0.5) | 0.7 (0.5–1.0) |

|

| |||

Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 0.2 (0.1–0.5) | 0.4 (0.2–0.9) | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) |

|

| |||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 0.3 (0.1–0.9) | 1.0 (0.6–1.9) | 1.7 (1.0–2.9) |

|

| |||

Diagnosed diabetes Diagnosed diabetes | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) | 1.6 (1.0–2.4) | 3.1 (2.1–4.5) |

|

| |||

| All-cause mortality | |||

No diabetes No diabetes | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | 3.7 (3.3–4.1) | 7.4 (6.7–8.1) |

|

| |||

Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 2.1 (1.5–2.9) | 5.0 (4.0–6.4) | 10.0 (8.4–12.0) |

|

| |||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 2.5 (1.7–3.7) | 5.6 (4.3–7.4) | 10.8 (8.8–13.3) |

|

| |||

Diagnosed diabetes Diagnosed diabetes | 2.9 (2.4–3.6) | 7.4 (6.3–8.7) | 15.3 (13.5–17.4) |

ARIC = Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities; HbA1c = hemoglobin A1c.

In Cox proportional hazards models (model 1), confirmed undiagnosed diabetes was strongly associated with risk for diagnosed diabetes during follow-up (HR, 25.00 [95% CI, 21.10 to 28.28]) (Table 4). Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes was also a risk factor for diagnosed diabetes (HR, 5.75 [CI, 5.16 to 6.40]). Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes was significantly associated with all other outcomes, particularly peripheral artery disease (HR, 3.50 [CI, 2.44 to 5.01]). These associations persisted even after multivariable adjustment for major risk factors (model 2). Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes was also significantly associated with most outcomes; however, these associations were weaker than those for confirmed undiagnosed diabetes. Compared with unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes, confirmed undiagnosed diabetes was statistically significantly more strongly associated with incident diagnosed diabetes (P < 0.001), cardiovascular disease (P = 0.016), and peripheral artery disease (P < 0.001). We observed no statistically significant interactions by race or race–center (P value for interaction >0.1 for all).

Table 4

Adjusted Hazard Ratios and 95% CIs for Major Clinical Outcomes, by Baseline Diabetes Status at ARIC Study Visit 2 (1990–1992)*

| Events/Participants, n/N | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Model 1† | Model 2‡ | ||

| Incident diagnosed diabetes | |||

|

| |||

No diabetes No diabetes | 2830/11 224 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

| |||

Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 400/595 | 5.75 (5.16–6.40)§ | 4.32 (3.87–4.82)§ |

|

| |||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 343/380 | 25.00 (22.10–28.28)§ | 15.90 (13.99–18.07)§ |

|

| |||

| Chronic kidney disease | |||

No diabetes No diabetes | 2653/11 108 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

| |||

Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 188/582 | 1.55 (1.33–1.80) | 1.24 (1.07–1.44) |

|

| |||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 134/373 | 1.80 (1.51–2.14) | 1.51 (1.26–1.80) |

|

| |||

Diagnosed diabetes Diagnosed diabetes | 456/1017 | 2.91 (2.63–3.22) | 2.53 (2.27–2.82) |

|

| |||

| Cardiovascular disease | |||

No diabetes No diabetes | 2550/10 466 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

| |||

Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 180/515 | 1.52 (1.31–1.77)§ | 1.20 (1.03–1.40)§ |

|

| |||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 146/347 | 1.99 (1.68–2.36)§ | 1.52 (1.28–1.81)§ |

|

| |||

Diagnosed diabetes Diagnosed diabetes | 429/839 | 2.75 (2.48–3.06) | 2.17 (1.95–2.43) |

|

| |||

| Peripheral artery disease | |||

No diabetes No diabetes | 308/10 819 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

| |||

Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 20/570 | 1.24 (0.79–1.95)§ | 0.93 (0.59–1.48)§ |

|

| |||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 34/368 | 3.50 (2.44–5.01)§ | 2.47 (1.70–3.57)§ |

|

| |||

Diagnosed diabetes Diagnosed diabetes | 130/996 | 5.60 (4.53–6.92) | 4.03 (3.19–5.09) |

|

| |||

| All-cause mortality | |||

No diabetes No diabetes | 4110/11 290 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

| |||

Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes Unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 304/595 | 1.45 (1.29–1.63) | 1.29 (1.15–1.45) |

|

| |||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 216/383 | 1.67 (1.45–1.91) | 1.48 (1.29–1.71) |

|

| |||

Diagnosed diabetes Diagnosed diabetes | 743/1078 | 2.31 (2.13–2.50) | 1.98 (1.82–2.16) |

ARIC = Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities; HbA1c = hemoglobin A1c.

In sensitivity analyses of isolated elevations in HbA1c or fasting glucose level (which together make up the unconfirmed group), persons with elevated HbA1c level tended to have higher absolute risk than those with elevated fasting glucose level (Appendix Table 2, available at Annals.org). Both isolated fasting glucose elevation (HR, 5.56 [CI, 4.92 to 6.28]) and isolated HbA1c elevation (HR, 6.40 [CI, 5.25 to 7.80]) were associated with future diagnosis of diabetes (Appendix Table 3 [model 1], available at Annals.org). Associations for incident chronic kidney disease (P = 0.049), incident cardiovascular disease (P = 0.037), peripheral artery disease (P = 0.008), and all-cause mortality (P = 0.013) tended to be stronger for elevated HbA1c level than for elevated fasting glucose level.

Appendix Table 2

Incidence Rates per 1000 Person-Years and Adjusted 5-, 10-, and 15-Year Cumulative Incidence (Risk) for Major Clinical Outcomes, by Isolated Fasting Glucose Elevation, Isolated HbA1c Elevation, Confirmed Undiagnosed Diabetes, or Diagnosed Diabetes at ARIC Study Visit 2 (1990–1992)*

| Outcome, by Diabetes Status | Incidence Rate per 1000 Person-Years (95% CI) | Adjusted Cumulative Incidence (95% CI), %† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| 5 y | 10 y | 15 y | ||

| Incident diagnosed diabetes | ||||

|

| ||||

No diabetes No diabetes | 14.8 (14.3–15.4) | 0.7 (0.6–0.9) | 8.7 (8.0–9.5) | 19.8 (18.5–21.2) |

|

| ||||

Isolated fasting glucose elevation Isolated fasting glucose elevation | 63.7 (56.9–71.5) | 10.5 (7.8–14.1) | 49.8 (44.4–55.4) | 70.9 (65.6–76.0) |

|

| ||||

Isolated HbA1c elevation Isolated HbA1c elevation | 70.5 (58.3–85.3) | 8.5 (5.0–14.2) | 48.4 (40.0–57.5) | 74.3 (65.7–82.1) |

|

| ||||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 156.8 (141.1–174.3) | 42.1 (36.8–47.8) | 91.1 (87.4–94.1) | 97.3 (94.9–98.7) |

|

| ||||

| Chronic kidney disease | ||||

No diabetes No diabetes | 12.7 (12.3–13.2) | 0.4 (0.3–0.5) | 3.4 (3.0–3.8) | 6.1 (5.5–6.7) |

|

| ||||

Isolated fasting glucose elevation Isolated fasting glucose elevation | 17.9 (15.1–21.3) | 1.3 (0.6–2.8) | 5.5 (3.8–7.9) | 10.1 (7.6–13.3) |

|

| ||||

Isolated HbA1c elevation Isolated HbA1c elevation | 22.6 (17.4–29.5) | 1.5 (0.5–4.4) | 8.1 (4.9–13.1) | 14.3 (9.7–20.7) |

|

| ||||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 21.4 (18.1–25.4) | 0.7 (0.2–2.0) | 6.5 (4.5–9.3) | 12.2 (9.3–16.0) |

|

| ||||

Diagnosed diabetes Diagnosed diabetes | 31.6 (28.8–34.6) | 2.8 (2.1–3.9) | 14.5 (12.4–16.8) | 26.2 (23.3–29.4) |

|

| ||||

| Cardiovascular disease | ||||

No diabetes No diabetes | 12.1 (11.7–12.6) | 1.6 (1.4–1.9) | 4.2 (3.7–4.6) | 8.1 (7.4–8.8) |

|

| ||||

Isolated fasting glucose elevation Isolated fasting glucose elevation | 17.2 (14.4–20.5) | 2.5 (1.5–4.2) | 6.5 (4.7–9.0) | 12.3 (9.6–15.7) |

|

| ||||

Isolated HbA1c elevation Isolated HbA1c elevation | 25.7 (19.9–33.2) | 4.5 (2.4–8.2) | 10.0 (6.6–15.1) | 17.7 (12.8–24.1) |

|

| ||||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 24.6 (21.0–29.0) | 3.9 (2.6–6.0) | 10.4 (7.9–13.5) | 17.4 (14.1–21.4) |

|

| ||||

Diagnosed diabetes Diagnosed diabetes | 33.6 (30.6–37.0) | 5.1 (4.0–6.5) | 14.6 (12.6–17.0) | 25.7 (22.8–29.0) |

|

| ||||

| Peripheral artery disease | ||||

No diabetes No diabetes | 1.4 (1.3–1.6) | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | 0.7 (0.6–0.9) | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) |

|

| ||||

Isolated fasting glucose elevation Isolated fasting glucose elevation | 1.3 (0.7–2.4) | 0.3 (0.1–1.3) | 0.6 (0.2–1.8) | 1.0 (0.5–2.3) |

|

| ||||

Isolated HbA1c elevation Isolated HbA1c elevation | 3.9 (2.1–7.2) | 0.9 (0.2–3.7) | 2.5 (1.0–5.9) | 3.1 (1.4–6.9) |

|

| ||||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 5.1 (3.7–7.2) | 1.0 (0.4–2.4) | 2.9 (1.7–5.0) | 4.5 (2.9–7.1) |

|

| ||||

Diagnosed diabetes Diagnosed diabetes | 8.2 (6.9–9.8) | 1.7 (1.1–2.7) | 4.7 (3.4–6.3) | 8.0 (6.1–10.4) |

|

| ||||

| All-cause mortality | ||||

No diabetes No diabetes | 17.5 (17.0–18.0) | 2.1 (1.9–2.3) | 5.4 (4.9–5.9) | 10.5 (9.8–11.2) |

|

| ||||

Isolated fasting glucose elevation Isolated fasting glucose elevation | 24.6 (21.4–28.2) | 3.1 (2.1–4.7) | 7.3 (5.5–9.5) | 14.8 (12.2–17.8) |

|

| ||||

Isolated HbA1c elevation Isolated HbA1c elevation | 33.8 (27.7–41.2) | 4.2 (2.4–7.3) | 10.3 (7.2–14.6) | 17.5 (13.3–22.9) |

|

| ||||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 30.1 (26.3–34.4) | 4.0 (2.8–5.9) | 8.8 (6.8–11.4) | 16.4 (13.5–19.8) |

|

| ||||

Diagnosed diabetes Diagnosed diabetes | 41.8 (38.9–44.9) | 5.5 (4.6–6.7) | 12.9 (11.4–14.7) | 24.4 (22.1–26.9) |

ARIC = Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities; HbA1c = hemoglobin A1c.

Appendix Table 3

Adjusted Hazard Ratios and 95% CIs for Major Clinical Outcomes, by Isolated Fasting Glucose Elevation, Isolated HbA1c Elevation, Confirmed Undiagnosed Diabetes, or Diagnosed Diabetes at ARIC Study Visit 2 (1990–1992)*

| Diabetes Status, by Outcome | Events/Participants, n/N | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Model 1† | Model 2‡ | ||

| Incident diagnosed diabetes | |||

|

| |||

No diabetes No diabetes | 2830/11 224 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

| |||

Isolated fasting glucose elevation Isolated fasting glucose elevation | 294/435 | 5.56 (4.92–6.28) | 4.17 (3.68–4.72) |

|

| |||

Isolated HbA1c elevation Isolated HbA1c elevation | 106/160 | 6.40 (5.25–7.80) | 4.82 (3.95–5.89) |

|

| |||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 343/380 | 25.06 (22.15–28.35) | 15.93 (14.02–18.10) |

|

| |||

| Chronic kidney disease | |||

No diabetes No diabetes | 2653/11 108 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

| |||

Isolated fasting glucose elevation Isolated fasting glucose elevation | 133/427 | 1.43 (1.20–1.70)§ | 1.15 (0.96–1.37) |

|

| |||

Isolated HbA1c elevation Isolated HbA1c elevation | 55/155 | 1.96 (1.49–2.56)§ | 1.53 (1.17–2.01) |

|

| |||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 134/373 | 1.80 (1.51–2.15) | 1.51 (1.26–1.81) |

|

| |||

Diagnosed diabetes Diagnosed diabetes | 456/1017 | 2.92 (2.64–3.23) | 2.54 (2.28–2.82) |

|

| |||

| Cardiovascular disease | |||

No diabetes No diabetes | 2550/10 466 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

| |||

Isolated fasting glucose elevation Isolated fasting glucose elevation | 121/380 | 1.38 (1.15–1.66)§ | 1.09 (0.90–1.31)§ |

|

| |||

Isolated HbA1c elevation Isolated HbA1c elevation | 59/135 | 1.93 (1.49–2.50)§ | 1.55 (1.19–2.01)§ |

|

| |||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 146/347 | 2.00 (1.69–2.36) | 1.52 (1.28–1.81) |

|

| |||

Diagnosed diabetes Diagnosed diabetes | 429/839 | 2.76 (2.48–3.06) | 2.18 (1.95–2.43) |

|

| |||

| Peripheral artery disease | |||

No diabetes No diabetes | 308/10 819 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

| |||

Isolated fasting glucose elevation Isolated fasting glucose elevation | 10/419 | 0.81 (0.43–1.52)§ | 0.64 (0.34–1.21)§ |

|

| |||

Isolated HbA1c elevation Isolated HbA1c elevation | 10/151 | 2.65 (1.40–5.00)§ | 1.72 (0.91–3.27)§ |

|

| |||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 34/368 | 3.52 (2.46–5.04) | 2.48 (1.71–3.59) |

|

| |||

Diagnosed diabetes Diagnosed diabetes | 130/996 | 5.63 (4.55–6.95) | 4.05 (3.21–5.11) |

|

| |||

| All-cause mortality | |||

No diabetes No diabetes | 4110/11 290 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

| |||

Isolated fasting glucose elevation Isolated fasting glucose elevation | 207/435 | 1.33 (1.16–1.53)§ | 1.20 (1.04–1.38)§ |

|

| |||

Isolated HbA1c elevation Isolated HbA1c elevation | 97/160 | 1.81 (1.48–2.22)§ | 1.54 (1.25–1.89)§ |

|

| |||

Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes Confirmed undiagnosed diabetes | 216/383 | 1.67 (1.46–1.92) | 1.49 (1.29–1.71) |

|

| |||

Diagnosed diabetes Diagnosed diabetes | 743/1078 | 2.31 (2.14–2.50) | 1.99 (1.82–2.16) |

ARIC = Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities; HbA1c = hemoglobin A1c.

Discussion

Current clinical guidelines recommend that elevated glucose or HbA1c levels be confirmed in a second blood sample for diagnosis of diabetes. We comprehensively evaluated the prognostic implications of using a combination of HbA1c and fasting glucose levels from a single blood sample to identify persons with undiagnosed diabetes in the community. We found that this confirmatory definition had high positive predictive value for future risk for diagnosed diabetes and was associated with substantial risk for major clinical end points.

This study provides construct validity for a confirmatory definition of undiagnosed diabetes that is based on a combination of HbA1c and fasting glucose measured in a single blood sample. This definition could facilitate both clinical practice and the conduct of epidemiologic studies. The vast majority of prior epidemiologic studies have used definitions of undiagnosed diabetes that did not involve confirmatory testing. Such definitions greatly inflate the prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes (21, 22). In research cohorts, using a combination of fasting glucose and HbA1c levels measured in a single blood sample is substantially more cost-effective than requiring participants to return for repeated phlebotomy. In the clinical setting, using both tests allows providers to make clinical decisions based on the HbA1c level, which drives treatment decisions. Our data suggest high general concordance between fasting glucose and HbA1c levels; therefore, attention should be paid to any sizeable discordance between them because this may indicate a sample processing problem or a coexisting medical condition that may be interfering with either test.

The single-sample confirmatory definition of undiagnosed diabetes had very high specificity and a high positive predictive value for predicting future diabetes diagnoses. The modest positive predictive value during the first 5 years of follow-up may seem to suggest that there are many false-positive diagnoses; however, the high positive predictive value with longer follow-up (almost 90% at 15 years) demonstrated that most of these persons progressed to diabetes over time. In contrast, the positive predictive value for unconfirmed and confirmed cases combined was very low early on and reached only 71% at 15 years. The negative predictive value was high for both groups, suggesting that false-negatives are not a major concern with either definition. The lower sensitivity of the confirmatory definition suggests that persons with unconfirmed diabetes should still be followed over time. To increase sensitivity, repeated testing at a second visit to confirm additional cases (identified in the unconfirmed group) would be needed. Overall, our results support the efficiency of a single-sample definition of undiagnosed diabetes.

Understanding disease risk as it relates to diagnostic thresholds is crucial (23). Progression to diagnosed diabetes was high in persons with elevated glucose or HbA1c level (confirmed or unconfirmed), although the absolute and relative risks for the confirmed definition were extraordinarily high—nearly all participants with confirmed undiagnosed diabetes who remained alive were subsequently diagnosed with diabetes. This is not to say that persons with unconfirmed undiagnosed diabetes were not at risk for clinical outcomes; by definition, this population has a high prevalence of prediabetes, and our data demonstrate that they are at future risk for diabetes and other major clinical outcomes.

Limitations of this study that should be considered in the interpretation of the results include the lack of information on repeated testing at a second time point in a new blood sample or contemporaneous information on 2-hour glucose level. The reliance on self-reported diabetes cases during follow-up is also a potential limitation, although self-reported diabetes has been shown to be highly reliable and specific in the ARIC cohort (24). Clinically relevant results measured at the ARIC visit are reported to participants, and notifying them about abnormal glucose results may have increased the probability of a diabetes diagnosis. On a related note, the majority of diabetes diagnoses would have been made on the basis of glucose measures during follow-up because HbA1c measurement was not recommended for diagnosis until 2009. This would inherently favor the predictive capacity of definitions of undiagnosed diabetes based on fasting glucose level rather than HbA1c level in the present study.

Strengths of this study include the large population of black and white adults with more than 20 years of active follow-up for major clinical outcomes. This study also benefited from the rigorous and standardized data collection procedures implemented in the ARIC study. Baseline in the current study occurred from 1990 to 1992, which allowed us to evaluate how risks played out in a scenario where screening and diagnostic cut points for diabetes were higher. Such a study would not be possible in the current era, where few diabetes cases in the U.S. adult population are undiagnosed (21).

Current clinical practice guidelines are not clear on whether HbA1c and fasting glucose levels from a single blood sample can be used to diagnose diabetes. Our findings support clinical use of a combination of HbA1c and fasting glucose levels from a single blood sample to identify cases of undiagnosed diabetes in the population, although these results will need to be confirmed in other data sets. In our study, a single-sample confirmatory definition of undiagnosed diabetes combining elevated levels of fasting glucose and HbA1c had high positive predictive value for future diagnosis of diabetes and captured persons at high risk for clinical outcomes. The relatively low sensitivity of this definition in identifying future cases of diabetes suggests that those with isolated fasting glucose elevations (which are more common) or isolated HbA1c elevations (which are less common) at a single time point should be retested at a later time to ensure that cases are not missed, which is consistent with current clinical recommendations. The associations of unconfirmed cases of undiagnosed diabetes with major clinical outcomes—even if many of these persons did not develop diabetes—reinforce that hyperglycemia and its associated risks exist along a continuum and emphasize the need for interventions to prevent progression from prediabetes to diabetes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions.

Financial Support: The ARIC study has received federal funds from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, under contract nos. HHSN268201700001I, HHSN268201700002I, HHSN268201700003I, HHSN268201700005I, and HHSN268201700004I. Dr. Selvin was supported by grants K24DK106414 and R01DK089174 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health. Dr. Matsushita was supported by grant R21HL133694 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

Conception and design: E. Selvin.Statistical Analysis: D. Wang

Drafting of the article: E. Selvin.

Critical revision for important intellectual content and interpretation of the data: E. Selvin, D. Wang, K. Matsushita, M. Grams, J. Coresh.

Final approval of the article: E. Selvin, D. Wang, K. Matsushita, M. Grams, J. Coresh.

Statistical expertise: E. Selvin, D. Wang, J. Coresh.

Obtaining of funding: E. Selvin.

Collection and assembly of data: E. Selvin. J. Coresh. K. Matsushita. M. Grams.

Disclosures: Dr. Matsushita reports grants and personal fees from Fukuda Denshi and Kyowa Hakko Kirin outside the submitted work. Authors not named here have disclosed no conflicts of interest. Disclosures can also be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum=M18-0091.

Reproducible Research Statement: Study protocol, statistical code, and data set: Available from Dr. Selvin (ude.uhj@nivlese).

Contributor Information

Elizabeth Selvin, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.

Dan Wang, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland.

Kunihiro Matsushita, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.

Morgan E. Grams, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.

Josef Coresh, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.7326/m18-0091

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc6082697?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.7326/m18-0091

Article citations

Diabetes and Dyslipidemia Screening in Pediatric Practice.

Mo Med, 121(3):206-211, 01 May 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38854609

Review

Associations between hyperuricemia and ultrasound-detected knee synovial abnormalities in middle-aged and older population: a cross-sectional study.

J Orthop Surg Res, 19(1):226, 04 Apr 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38575963 | PMCID: PMC10996165

2. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2024.

Diabetes Care, 47(suppl 1):S20-S42, 01 Jan 2024

Cited by: 141 articles | PMID: 38078589

Review

Association between hyperuricaemia and hand osteoarthritis: data from the Xiangya Osteoarthritis Study.

RMD Open, 9(4):e003683, 01 Dec 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38053456 | PMCID: PMC10693871

Global variation in diabetes diagnosis and prevalence based on fasting glucose and hemoglobin A1c.

Nat Med, 29(11):2885-2901, 09 Nov 2023

Cited by: 8 articles | PMID: 37946056 | PMCID: PMC10667106

Go to all (36) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Identifying Trends in Undiagnosed Diabetes in U.S. Adults by Using a Confirmatory Definition: A Cross-sectional Study.

Ann Intern Med, 167(11):769-776, 24 Oct 2017

Cited by: 41 articles | PMID: 29059691 | PMCID: PMC5744859

Value of risk stratification to increase the predictive validity of HbA1c in screening for undiagnosed diabetes in the US population.

J Gen Intern Med, 23(9):1346-1353, 10 Jun 2008

Cited by: 29 articles | PMID: 18543044 | PMCID: PMC2517991

Combined use of fasting plasma glucose and glycated hemoglobin A1c in the screening of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance.

Acta Diabetol, 47(3):231-236, 17 Sep 2009

Cited by: 62 articles | PMID: 19760291

Effects of diabetes definition on global surveillance of diabetes prevalence and diagnosis: a pooled analysis of 96 population-based studies with 331,288 participants.

Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 3(8):624-637, 21 Jun 2015

Cited by: 85 articles | PMID: 26109024 | PMCID: PMC4673089

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NHLBI NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: R21 HL133694

NIDDK NIH HHS (2)

Grant ID: K24 DK106414

Grant ID: R01 DK089174