Abstract

Free full text

Ketone body signaling mediates intestinal stem cell homeostasis and adaptation to diet

SUMMARY

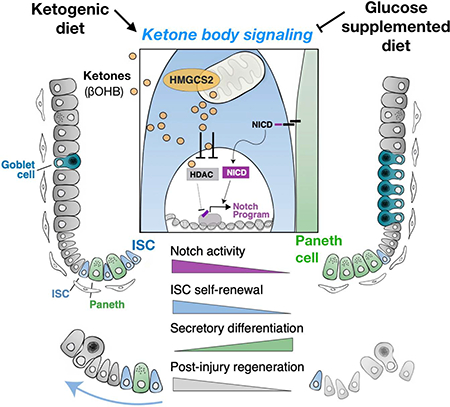

Little is known about how metabolites couple tissue-specific stem cell function with physiology. Here we show that in the mammalian small intestine, the expression of Hmgcs2 (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthetase 2)—the gene encoding the rate-limiting enzyme in the production of ketone bodies, including beta-hydroxybutyrate (βOHB)—distinguishes the self-renewing Lgr5+ stem cells (ISCs) from differentiated cell types. Hmgcs2 loss depletes βOHB levels in Lgr5+ ISCs and skews their differentiation towards secretory cell fates, which can be rescued by exogenous βOHB and class I histone deacetylases (HDACs) inhibitor treatment. Mechanistically, βOHB acts by inhibiting HDACs to reinforce Notch signaling, thereby instructing ISC self-renewal and lineage decisions. Notably, while a high-fat ketogenic diet elevates ISC function and post-injury regeneration through βOHB-mediated Notch signaling, a glucose-supplemented diet has the opposite effects. These findings reveal how control of βOHB-activated signaling in ISCs by diet helps to fine-tune stem cell adaptation in homeostasis and injury.

INTRODUCTION

In the mammalian intestine, the actively cycling Lgr5+ intestinal stem cells (ISCs) depend on the precise control of intrinsic regulatory programs that include the Wnt, Notch, and BMP developmental signaling pathways as well as extrinsic cues from their environment to dynamically remodel intestinal composition(Barker et al., 2007; Fre et al., 2005; Mihaylova et al., 2014; Nakada et al., 2011; Qi et al., 2017; van der Flier et al., 2009; Yan et al., 2017). Lgr5+ ISCs reside at the bottom of intestinal crypts and are nestled between Paneth cells in the small intestine(Sato et al., 2011), deep secretory cells in the colon(Sasaki et al., 2016) and stromal cells throughout the small intestine and colon(Degirmenci et al., 2018; Shoshkes-Carmel et al., 2018), which comprise components of the ISC niche. These ISC niche cells elaborate myriad growth factors and ligands that determine ISC identity in part through modulation of these developmental pathways. In addition to these semi-static epithelial and stromal niche components, migratory immune cell subsets provide inputs that inform stem cell fate decisions through cytokine signaling based on external signals (Biton et al., 2018; Lindemans et al., 2015).

Although significant progress has been made in deciphering how transcription factors or interactions with the niche exert executive control on Lgr5+ ISC identity, recent evidence implicate an emerging role for energetic metabolites and metabolism in this process. For example, the Paneth niche cells provide lactate, an energetic substrate, to promote Lgr5+ ISC activity through mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (Rodriguez-Colman et al., 2017). Furthermore, low calorie metabolic states extrinsically control stem-cell number and function in calorically restricted dietary regimens through the Paneth cell niche (Igarashi and Guarente, 2016; Yilmaz et al., 2012), and intrinsically engage a fatty acid oxidation metabolic program in ISCs to enhance stemness (Mihaylova et al., 2018). However, more investigation is needed to delineate how changes in the ISC microenvironment interplay with stem cell metabolism to control stemness programs.

Recent studies also indicate that dietary nutrients play an important instructive role in the maintenance of tissues and adult stem-cells in diverse tissues(Mihaylova et al., 2014). For example, ascorbic acid (i.e., Vitamin C) is an essential dietary nutrient that regulates hematopoietic stem-cell function via TET2 enzymes(Agathocleous et al., 2017; Cimmino et al., 2017). In the intestine, low levels of dietary vitamin D compromise the function of Lgr5+ ISCs (Peregrina et al., 2015). Furthermore, fatty acid components or their derivatives in high-fat diets (HFDs) enhance ISC function through activation of a PPAR-delta program(Beyaz et al., 2016) and high levels of dietary cholesterol through phospholipid remodeling(Wang et al., 2018). While these examples demonstrate that exogenous nutrients couple diet to adult stem cell activity, little is known about how systemic or stem cell generated endogenous metabolites that become highly enriched in Lgr5+ ISCs coordinate cell fate decisions. Here, we interrogate how levels of the ketone body beta-hydroxybutyrate (βOHB) in Lgr5+ ISCs governs a diet responsive metabolite signaling axis that modulates the Notch program to sustain intestinal stemness in homeostasis and regenerative adaptation.

RESULTS

Ketogenic enzyme HMGCS2 is enriched in Lgr5+ intestinal stem cells (ISCs)

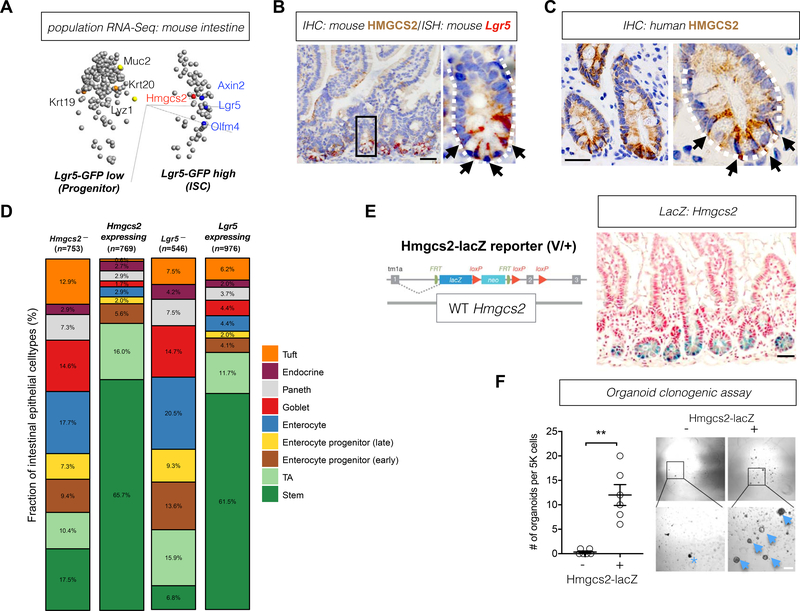

To identify the metabolic pathways enriched in ISCs, we analyzed RNA-Seq data(Beyaz et al., 2016; Mihaylova et al., 2018) from populations of flow sorted Lgr5-GFPhi ISCs(Sato et al., 2009), Lgr5-GFPlow progenitors(Sato et al., 2009) and CD24+c-Kit+ Paneth cells(Beyaz et al., 2016; Sato et al., 2011) from Lgr5-eGFP-IRES-CreERT2 knock-in mice(Barker et al., 2007) (Data Availability). Because Paneth cells are metabolically distinct from ISCs and progenitors(Rodriguez-Colman et al., 2017), we focused on genes differentially expressed between ISCs and progenitors (filtered by two group comparison ρ/ρmax=5e-4; p<0.14, q<0.28). 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl-CoA Synthase 2 (Hmgcs2), the gene encoding the rate-limiting step for ketogenesis (schematic, Figure S1A), was a metabolic enzyme with significant differential expression (p=0.002; q=0.046) between Lgr5+ ISCs (GFPhi cells) and progenitors (GFPlow cells) (Figure 1A and Table S1), which was also in agreement with the published Lgr5 ISC signature (Munoz et al., 2012a). Lastly, re-analysis of single-cell transcriptome data from the small intestine(Haber et al., 2017) demonstrated that 65.7% of Hmgcs2-expressing cells were stem cells and 16% were transit-amplifying progenitors, which is similar to the distribution observed for Lgr5-expressing cells (Figure 1D).

A, Principal component analysis (PCA) for genes differentially expressed in Lgr5-GFPlow progenitors versus Lgr5-GFPhi ISCs. Variance filtered by (ρ/ρmax)=5e-4; p=0.14, q=0.28; plot/total:25¾5578 variables. Axin2, axin-like protein 2; Hmgcs2, 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl-CoA Synthase 2; Lgr5, Leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein coupled receptor 5; Olfm4, Olfactomedin 4; n=4 mice. (see also Table S1). B, Mouse HMGCS2 protein expression by immunohistochemistry (IHC, brown) and Lgr5 expression by ISH (red). White-dashed line defines the intestinal crypt and black arrows indicate HMGCS2+ cells. The image represents one of 3 biological replicates. Scale bar, 50um. C, Human HMGCS2 protein expression by immunohistochemistry (IHC, brown). White-dashed line defines the intestinal crypt and black arrows indicate HMGCS2+ cells. The image represents one of 10 biological replicates. Scale bar, 50um. D, Stacked barplots show cell composition (%) of Hmgcs2-, Hmgcs2-expressing, Lgr5- and Lgr5-expressing intestinal epithelial cells. Numbers in parenthesis indicate the total number (n) of the noted cell populations. E, Hmgcs2-lacZ reporter construct where the lacZ-tagged allele reflects endogenous Hmgcs2 expression (left). Hmgcs2-lacZ expression (blue) in the small intestine (right). The image represents one of 3 biological replicates. Scale bar, 50um. F, Organoid-forming potential of flow-sorted Hmgcs2-lacZ− and Hmgcs2-lacZ+ crypt epithelial cells (7AAD-EpCAM+). 5,000 cells from each population was flow-sorted into matrigel with crypt culture media. Arrows indicate organoids and asterisk indicates aborted organoid debris. The numbers of organoids formed from plated cells were quantified at 5 day in culture. Data represent mean+/−s.e.m. **p<0.01. n=6 samples from 3 mice. Scale bar: 20 μm.

We verified the enrichment of Hmgcs2 expression in Lgr5+ ISCs at both the mRNA and protein levels, by qRT-PCR and immunoblots of flow sorted ISCs, progenitors and Paneth cells (Figures S1B and C). Single cell immunoblots also illustrated that HMGCS2-expressing cells (HMGCS2+) were highly enriched in the flow sorted Lgr5+ ISCs (77.97%) but less frequent in total intestinal crypt cells (21.17%) (Figure S1D). Moreover, dual ISH and IHC confirmed the concordance between Lgr5 and Hmgcs2 expression in the intestine (Figure 1B). Selectively high HMGCS2 expression in the crypt base cells (CBCs) was also observed in human duodenum (Figure 1C). Expression levels of metabolic genes often fluctuate depending on nutrient availability in diverse dietary regimens(Beyaz et al., 2016; Rodriguez-Colman et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018; Yilmaz et al., 2012). Notably, unlike the metabolic rate-limiting enzymes of glucose metabolism, TCA cycle, and fatty acid oxidation, Hmgcs2 mRNA expression is robustly enriched in Lgr5+ ISCs compared to progenitors across a range of physiological states (e.g., fed, fasted and old age), even in fasting where it is strongly induced (Figures S1E and S1F), raising the possibility that Hmgcs2 plays a key role in the maintenance of Lgr5+ ISCs.

We next engineered heterozygous Hmgcs2-lacZ (i.e. Hmgcs2V/+) reporter mice (Figures 1E and S1G, Methods) to ascertain whether Hmgcs2 expressing (Hmgcs2+) crypt cells possessed functional stem-cell activity in organoid assays. Hmgcs2V/+ reporter mice were phenotypically indistinguishable from controls in body mass, causal blood glucose, serum βOHB, small intestinal length and crypt depth (Figures S1H–L). Consistent with ISH and IHC for Hmgcs2 (Figures 1B and and1C),1C), beta galactosidase (lacZ) staining of the small intestine from Hmgcs2V/+ mice predominantly highlighted CBC cells (Figure 1E). Functionally, using a fluorescein di-β-D-galactopyranoside (FDG) substrate of lacZ, we found that the Hmgcs2-lacZ+ fraction of crypt cells possessed nearly all of the organoid propagating activity compared to the LacZ− fraction (Figure 1F). This finding together with the strong co-expression of Hmgcs2 in Lgr5+ ISCs (Figures 1A–D, S1B to S1D) affirms Hmgcs2 expressing crypt cells as functional stem cells.

Loss of Hmgcs2 compromises intestinal stemness and regeneration

In addition to validating that Hmgcs2 marks Lgr5+ ISCs, we conditionally ablated Hmgcs2 in the entire intestine and specifically in Lgr5+ ISCs to decipher how its loss impacts stem cell maintenance. We engineered three separate tamoxifen-inducible conditional alleles (Methods): The first model is the Hmgcs2loxp/loxp; Villin-CreERT2 conditional intestinal knockout model that disrupts Hmgcs2 in all intestinal epithelial cell types upon tamoxifen administration (Figure 2A, termed iKO). The second model is the Hmgcs2loxp/loxp; Lgr5-EGFP-IRES-CreERT2 reporter mouse, where the Lgr5 knock-in allele has mosaic expression in the intestine and permits the enumeration and isolation of Lgr5-GFPhi ISCs by flow cytometry as well as the deletion of Hmgcs2 in the GFPhi subset of ISCs upon tamoxifen administration (Figures S2A and S2B), termed Lgr5-GFP reporter). This model is often used to quantify GFPhi ISCs and GFPlow progenitors(Beyaz et al., 2016; Mihaylova et al., 2018; Sato et al., 2009; Yilmaz et al., 2012). The third model is the Hmgcs2loxp/loxp; Lgr5-IRES-CreERT2; Rosa26LSL-tdTomato reporter mouse (termed, Lgr5 lineage tracer) that enables the deletion of Hmgcs2 upon tamoxifen administration in nearly all Lgr5+ ISCs and the permanent tdtTomato labeling of the stem cells and their progeny over time (Figures S2D to S2F). Given that this Lgr5-IRES-CreERT2 allele(Huch et al., 2013) is expressed by nearly all Lgr5+ ISCs, this third model (similar to the first iKO model) enables the quantification of how loss of a gene in ISCs, for example, alters the differentiation of stem-cell derived progeny within the entire intestine and also permits fate mapping from Lgr5+ ISCs (Figure S2M).

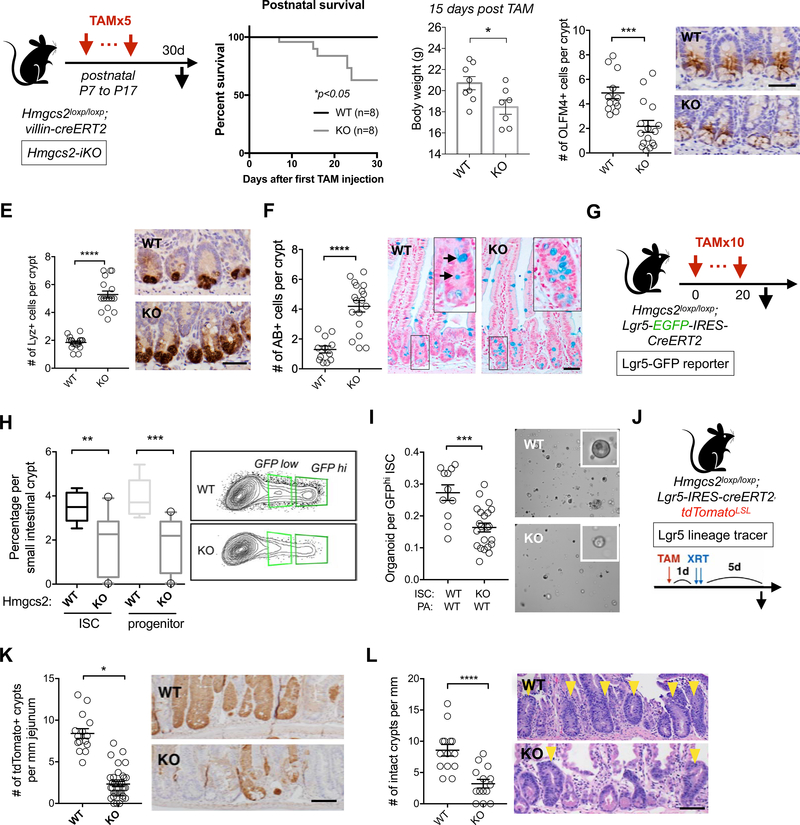

A, Schematic of intestinal Hmgcs2 deletion in postnatal mice with Villin-CreERT2 (iKO) including the timeline for tamoxifen (TAM) injections and tissue collection. B, Kaplan–Meier survival curves of the WT and Hmgcs2-iKO mice starting the first day of tamoxifen injection. C, Body weights of WT and Hmgcs2-iKO mice. 15 days after first TAM injection. D-F, Quantification (left) and representative images (right) of Olfactomedin 4+ (OLFM4+) stem cells by IHC (D), Lysozyme + (LYZ+) Paneth cells by IHC and (E), Mucin+ goblet cells by Alcian Blue (AB) (F) in proximal jejunal crypts. n>5 mice per group. For D-F, mice were analyzed at the age of 37 days. For D-F, Scale bars, 100um. G, Schematic of Hmgcs2 deletion with Lgr5-EGFP-IRES-CreERT2 (Lgr5-GFP reporter) including the timeline for tamoxifen (TAM) injections and tissue collection.1 day after last TAM injection (Day 21), ISCs and Paneth cells from WT or conditional Hmgcs2-null (KO) intestinal crypts were isolated using flow cytometry. H, Frequency of 7AAD-/Epcam+/CD24-/Lgr5-GFPhi ISCs and Lgr5-GFPlow progenitors in crypt cells from WT and KO mice by flow cytometry. n>10 mice per group. I, Organoid-forming assay for sorted WT and KO ISCs co-cultured with WT Paneth cells. Representative images: day 5 organoids. n>10 mice per group. Scale bar: 100um. J, Schematic of the Lgr5 lineage tracing including timeline of TAM injection, irradiation (XRT, 7.5Gy x 2) and tissue collection. K-L, Quantification and representative images of tdTomato+ Lgr5+ ISC-derived progeny labeled by IHC for tdTomato (K) and number of surviving crypts assessed by the microcolony assay (L). Scale bar:100 μm. n>25 crypts per measurement, n>5 measurements per mouse and n>3 mice per group. For box- and-whisker plots (H), the data are expressed as 10 to 90 percentiles. For dot plots (C-F,I,K and L), the data are expressed as mean+/−s.e.m. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005, ****p<0.001. n>25 crypts per measurement, n>3 measurements per mouse and n>5 mice per group.

In the iKO model, we administered five doses of tamoxifen starting at postnatal day 7 to iKO and control mice (Figure 2A). Interestingly, intestinal Hmgcs2 loss reduced the survival of iKO mice where no mortality was noted in the control cohort, and 15 days post-tamoxifen iKO mice had a modest but significant reduction in body mass relative to controls (Figures 2A–C). Also, at this same time point, there was a greater than 2-fold reduction in the numbers of Olfactomedin 4 (OLFM4) positive cells, a marker co-expressed by Lgr5+ ISCs and early progenitors (Figure 2D) and a greater than 2-fold increase in the numbers of Lysozyme 1 (LYZ1)+ Paneth cells and Alcian Blue (AB)+ goblet cells (Figures 2E and andF).F). These findings indicate that Hmgcs2 plays an essential role in sustaining ISC numbers and lineage balanced differentiation in the juvenile intestine.

To specifically interrogate the role of Hmgcs2 in adult ISC maintenance, we ablated Hmgcs2 in 12-week-old adult Lgr5-GFP reporter mice for 3 weeks (Figures 2G and S2A–B), which decreased the frequencies of Lgr5-GFPhi ISCs and Lgr5-GFPlow progenitors by 50% (Figure 2H). When co-cultured with WT Paneth cells, flow sorted Hmgcs2-null ISCs engendered 42.9% fewer and 34.6% smaller organoids compared to WT ISCs, indicating that Hmgcs2 loss in ISCs cell-autonomously attenuates organoid-initiating capacity (Figures 2I and S2C). Similarly, in the Lgr5-tdTomato lineage tracer mice, Hmgcs2 loss gradually reduced the numbers of OLFM4+ ISCs with no change in the proliferation or apoptosis of ISCs and progenitors (Figures S2G,S2J and S2K), small intestinal length (Figures S2H) or crypt depth (Figures S2I). As observed in the iKO model, the reduction in the numbers of OLFM4+ ISCs was accompanied by increases in the numbers of Paneth cells and goblet cells (Figure S2G), however, the numbers of chromogranin A+ enteroendocrine cells in the crypts were not affected (Figure S2L). Loss of Hmgcs2 in adult intestines not only dampens ISC self-renewal (i.e., fewer ISC numbers with less organoid-forming potential) but also shifts early differentiation within the crypt towards the secretory lineage (i.e., greater numbers of Paneth and goblet cells).

Lgr5+ ISCs drive intestinal maintenance in homeostasis and regeneration in response to injury such as from radiation-induced damage(Beumer and Clevers, 2016; Metcalfe et al., 2014). We induced tdTomato expression and Hmgcs2 excision in the Lgr5+ ISCs with tamoxifen one day prior to radiation-induced intestinal epithelial injury to ascertain whether Hmgcs2 affected the in vivo ability of these ISCs to regenerate the intestinal lining (Figure 2J). We assessed the efficiency of regeneration by quantifying the number of tdTomato+ clonal progeny generated from the Lgr5+ ISCs 5 days post-radiation exposure and the number of intact crypt units per length of intestine: First, Hmgcs2-null ISCs generated 5-fold fewer labeled tdTomato+ crypts (Figures 2J and and2K)2K) with fewer labeled progeny extending up crypt-villous units as was observed in controls (Figure S2M). Second, loss of Hmgcs2 also diminished the overall number of surviving intact crypts by 2-fold compared to controls (Figure 2L). Thus, these data demonstrate that Hmgc2 is critical for Lgr5+ ISC-mediated repair in vivo after injury.

HMGCS2 regulates secretory differentiation through NOTCH signaling

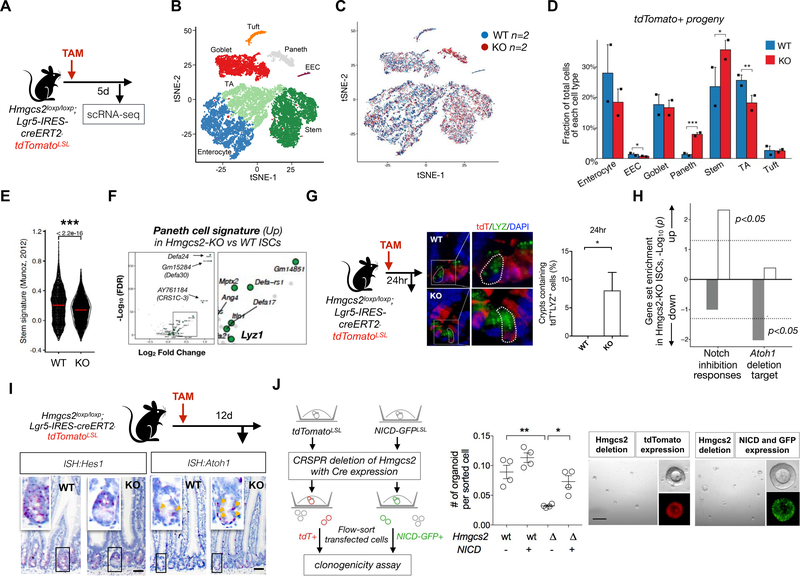

To gain mechanistic insight into how Hmgcs2 impacts the differentiation of ISCs, we performed droplet-based scRNA-seq (Figure 3A, Methods) on the sorted tdTomato+ progeny of WT and Hmgcs2-null ISCs five days after tamoxifen injection, a timepoint prior to the reduction in the number of Hmgcs2-null ISCs (Figure 2D)(Haber et al., 2017), chosen to allow us to capture early changes in regulatory programs. Cell-type clustering based on the expression of known marker genes partitioned the crypt cells into seven cell types (Figures 3B, ,3C,3C, S3A–S3C, Tables S2 and S3, and Methods)(Haber et al., 2017).

A, Schematic of the mouse model including the timeline of tamoxifen (TAM) injection and tissue collection for single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq). 5 days after TAM injection, intestinal crypts were isolated from WT and Hmgcs2-KO mice and the Lgr5+ ISC-derived tdTomato+ progeny were flow-sorted for scRNA-seq. B, Cell-type clusters. We used t-SNE to visualize the clustering (color coding) of 17,162 single cells (Hmgcs2-KO; n=2 mice; 7793 cells, vs WT; n=2 mice; 9369 cells), based on the expression of known marker genes(Haber et al., 2017). See also Figures S3B. EEC, enteroendocrine cells; TA, transit amplifying (progenitor) cells. C, Merged t-SNE plot of Tdtomato+ progeny derived from WT (blue) and Hmgcs2-KO (red) ISCs. D, Fraction of total cells per cell type. Error bars, s.e.m.; * FDR < 0.25, ** FDR < 0.1, *** FDR < 0.01; χ2 test (Methods and Table S2). E, Violin plot showing the distribution of the mean expression of the stem cell signature genes (Munoz et al., 2012a) in WT and Hmgcs2-KO ISCs. ***FDR < 0.0001; Mann–Whitney U test. F, Volcano plot displaying differential expressed (DE) genes in Hmgcs2-KO ISCs vs. WT ISCs. 20 of 194 significantly up-regulated genes in Hmgcs2-KO ISCs are Paneth cell markers (green dots)((Haber et al., 2017)). p<0.0001. n=2151 WT ISCs and n=2754 KO ISCs. G, Representative image and quantification at 24hr after TAM injection by immunofluorescence (IF) staining: tdTomato for progeny of Lgr5+ ISCs and Lysozyme (LYZ) as Paneth cell marker. n>25 crypts per measurement, n>3 measurements per mouse and n>5 mice per group. H, Gene set enrichment analysis of Notch-inhibition response genes (left) and Atoh1 deletion target genes (right)(Kim et al., 2014). Bar plot of the -Log10 (p-value) indicates the gene sets up- (white) or down-regulated (gray) in Hmgcs2-KO ISCs compared to WT ISCs. I, Hes Family BHLH Transcription Factor 1 (Hes1) and Atonal BHLH Transcription Factor 1(Atoh1) mRNA expression in intestinal crypts by ISH. Image represents one of 5 biological replicates per group. Yellow arrows indicate Atoh1 transcript positive cells. Scale bar: 50um. J, Schematic for assessing organoid-forming ability of genetically-engineered organoid cells with the CRISPR/CAS9 mediated loss of Hmgcs2 (left) and the constitutive Notch activation by Cre-induced NICD expression (right) or both. Transfected cells were flow-sorted based on the fluorescent markers and plated onto matrigel (Methods). Organoids were quantified and imaged after 5 days of culture (n=4 measurements from 2 independent experiments). Scale bar:200 μm. Data in the dot plot are expressed as mean+/−s.e.m. *p<0.05 and **p<0.01.

Acute deletion of Hmgcs2 in ISCs led to a modest increase in stem cells (35.34% compared to 22.96% by WT ISCs), fewer transient amplifying/bipotential progenitors(Kim et al., 2016) (TA, 18.40% compared to 25.73% by WT ISCs) and a pronounced 5.8-fold expansion of Paneth cells (7.88% compared to 1.36% by WT ISCs) (Figure 3D and Table S2). Further analysis of ISC profiles revealed that while Hmgcs2-loss weakened the Lgr5+ stemness signature(Munoz et al., 2012a) in ISCs (Figure 3E), it had only minor effects on proliferation and apoptosis signatures (Figure S3E and S3F). Together with the progressive loss of ISCs and the shift towards Paneth and goblet cell differentiation observed at the later time points after induction of Hmgcs2 deletion (Figures 2B and and2D2D–2F), these data support the notion that Hmgcs2 loss compromises stemness and skews their differentiation towards the secretory lineage.

These findings prompted us to investigate for signs of premature differentiation in Hmgcs2-null ISCs, which surprisingly show up-regulation of Paneth cell signature genes (Figure 3F). While six days after Hmgcs2 loss in ISCs had no effect on the numbers of tdTomato+ stem cells (Lgr5-GFPhi) or progenitors (Lgr5-GFPlow) (Figure S3H), Hmgcs2-null ISCs engendered substantially greater numbers of tdTomato+ Paneth cells after as few as 24 hours of deletion in jejunal sections (Figures 3G and S3G) and after 6 days of deletion by flow cytometry (Figure S3H).

In the mammalian intestine, Notch signaling activates Olfm4 transcription (a co-marker for Lgr5+ ISCs), maintains ISC self-renewal, and skews differentiation towards absorptive cell fates, which involves repressing atonal homolog 1 (Atoh1) transcription by the hairy and enhancer of split 1 (Hes1) transcription factor(Sancho et al., 2015). This sequence of events permits stem cell self-renewal and prevents differentiation to the secretory lineage(Sancho et al., 2015; VanDussen et al., 2012). Indeed, the rapid adoption of early secretory Paneth cell fates by Hmgcs2-null ISCs is compatible with a Notch-deficient phenotype(Sancho et al., 2015; Tian et al., 2015), which is confirmed by gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) in Hmgcs2-null versus control ISCs: Notch inhibition responsive genes were significantly upregulated, and Atoh1 deletion target genes were significantly down-regulated in Hmgcs2-null ISCs compared to WT ISCs (Figure 3H)(Kim et al., 2014). We validated the induction of Atoh1 transcripts and the reduction of its negative regulator Hes1 by ISH in Hmgcs2-null intestinal crypt cells compared to controls (Figure 3I). Lastly, enforced expression of the constitutively active Notch intracellular domain (NICD) rescued the organoid-forming capacity of Hmgcs2-null cells (Figure 3J), thereby supporting the paradigm that HMGCS2 actuates ISCs function through NOTCH signaling.

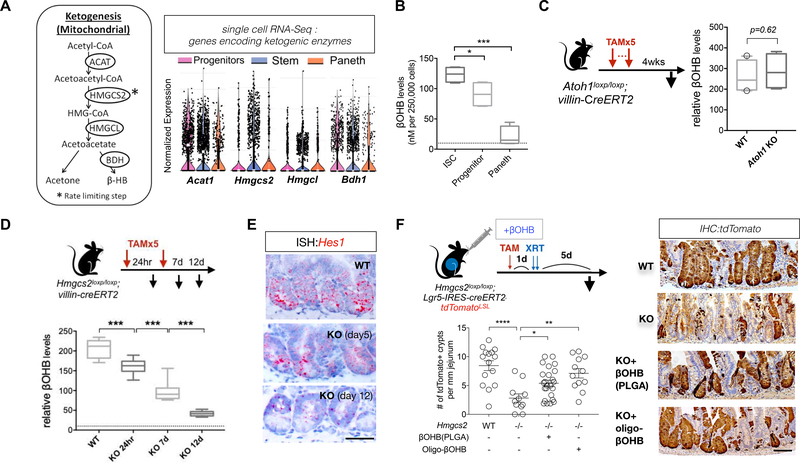

Beta-hydroxybutyrate (βOHB) compensates for Hmgcs2 loss in ISCs

HMGCS2 catalyzes the formation of HMG-CoA from acetoacetyl-CoA and acetyl-CoA, a rate-limiting step of ketone body production (i.e. ketogenesis, Figure 4A). While Hmgcs2 was selectively expressed in ISCs compared to progenitors and Paneth cells, genes encoding other ketogenic enzymes including Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 1 (Acat1), Hmg-CoA lyase (Hmgcl) and 3-Hydroxybutyrate Dehydrogenase 1 (Bdh1) were broadly expressed in both stem and progenitor cells compared to Paneth cells, based on the results of both population and scRNA-Seq (Figure 4A)(Adijanto et al., 2014). Consistent with these expression patterns, measured βOHB levels were highest in Lgr5-GFPhi ISCs followed by Lgr5-GFPlow progenitors and then Paneth cells (Figure 4B), which was near the detection threshold in sorted intestinal ISCs and progenitors after Hmgcs2 loss (dotted line in Figure 4B). In addition, genetic ablation of the Paneth cells, which provide paracrine metabolites to ISCs(Rodriguez-Colman et al., 2017), in an intestinal Atoh1-null model(Durand et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2012b) did not alter crypt expression of HMGCS2 protein or βOHB levels (Figures 4C, S4E–F), highlighting that HMGCS2-mediated ketogenesis in crypt cells generate ketone bodies independent of Paneth cells. Finally, genetic ablation of Hmgcs2 in all intestinal epithelial cells using adult iKO mice diminished βOHB levels over time in crypts (Figure 4D) with no impact on hepatic HMGCS2 protein expression and serum βOHB levels (Figures S4H–S4I). Interestingly, crypt βOHB levels after Hmgcs2 loss also correlated with a decline in Hes1 ISH expression over time (Figure 4E), highlighting that maximal reduction in Notch activity is observed at the nadir of βOHB depletion.

A, Relative expression of genes encoding enzymes for ketogenesis in ISCs, progenitors and Paneth cells: ACAT, acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase; BDH, 3-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase; HMGL, HMG-CoA lyase, visualized by violin plots for scRNA-Seq data. n=6 mice. B, Relative β-Hydroxybutyrate (βOHB) levels in flow-sorted Lgr5-GFPhi ISCs, Lgr5-GFPlow progenitors and Paneth cells. 250,000 cells of each cell population were directly sorted into the assay buffer and immediately processed for βOHB measurement. Dashed line indicates the detection limit of the colorimetric assay. n=8 samples per population from 4 mice. C, Schematic for Atoh1 deletion. 4 weeks after 5th (last) tamoxifen (TAM) injection, intestinal tissues were harvested for histology. Intestinal crypts were isolated for βOHB measurement. Quantification of βOHB levels in intestinal crypts from WT and Atoh1-KO mice. Levels of βOHB were normalized to total protein of crypt cells. n= 16 samples from 8 mice per group. D, Schematic of the mouse model of Hmgcs2 loss. After tamoxifen (TAM) injection, intestinal tissues were harvested for histology and intestinal crypts were isolated for βOHB measurement at the indicated time points (i.e. 24hr, 7d and 12 d after first TAM injection). E, Hes1 mRNA expression in intestinal crypts by ISH at indicated timepoints after inducing Hmgcs2 loss. Image represents one of 5 biological replicates per group. F, Schematic (top) of the mouse model including the timeline of tamoxifen (TAM) injection, oral administration of nanoparticle PLGA encapsulated βOHB or βOHB oligomers, irradiation (XRT, 7.5Gy x 2) and tissue collection. Quantification (bottom) and representative images (right) of tdTomato+ Lgr5+ ISC-derived lineage (cell progenies) by IHC. Scale bar:100 μm. n>25 crypts per measurement, n>5 measurements per mouse and n>3 mice per group. For box-and-whisker plots (B-D), data were expressed as box-and-whisker 10 to 90 percentiles. Data in dot plots were expressed as mean+/−s.e.m. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005.

We recently described a role for fatty acid oxidation (FAO) in the long-term maintenance of Lgr5+ ISCs, whose end product acetyl-CoA can feed into ketogenesis and other metabolic pathways. Genetic loss of intestinal Cpt1a (Carnitine palmitoyltransferase I), the rate-limiting step of FAO, resulted in compensatory elevation of HMGCS2 protein expression and in stable crypt βOHB concentrations (Figure S4A–S4D). Conversely, loss of Hmgcs2 in all intestinal epithelial cells had no impact on intestinal CPT1a protein levels or on FAO in Hmgcs2-null crypts (Figure S4J–S4K). Although intestinal loss of either Cpt1a or Hmgcs2 diminishes Lgr5+ ISC numbers, Cpt1a loss has no effect on intestinal differentiation (Mihaylova et al., 2018) whereas Hmgcs2 loss skews differentiation towards the secretory lineage (Figures 2E, ,2F2F and and3G).3G). Taken together, these findings indicate that FAO and ketogenesis maintain intestinal stem and progenitor cell activity partly through independent mechanisms.

We next examined whether βOHB rescues the function and secretory differentiation phenotype of Hmgcs2-null organoids. To address this question, we administered tamoxifen to control and Hmgcs2loxp/loxp; Lgr5-tdTomato lineage tracer mice 24 hours before crypt isolation (Figure S4L). Crypts with Hmgcs2-null ISCs were then cultured in standard media, with or without βOHB. Compared to controls, crypts with Hmgcs2-null ISCs were 34.4% less capable of forming organoids and the resulting organoids showed a 40.5% increase in goblet cells and a 64.3% decline in tdTomato+ cells per organoid (Figure S4L). These results indicate that Hmgcs2-null ISCs in vitro are less functional and are biased towards secretory differentiation as is seen in vivo. Exogenous βOHB but not lactate, a Paneth niche derived metabolite that sustains ISC function (Rodriguez-Colman et al., 2017), rectified these functional deficiencies (i.e., organoid-forming capacity and generation of tdTomato+ clones) and the secretory lineage bias of Hmgcs2-null organoids (Figures S4L and S4M). To investigate whether βOHB also compensates for the loss of intestinal HMGCS2 activity in vivo, we developed and delivered two modified forms of βOHB to the gastrointestinal tract of Hmgcs2-KO mice (Figure S4N). Oral administration of poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) encapsulated βOHB nanoparticles or βOHB oligomers (Figure S4N) partially restored intestinal regeneration after irradiation-induced damage, which otherwise was severely impaired upon Hmgcs2 intestinal deletion (Figure 4F). Thus, βOHB is sufficient to substitute for HMGCS2 activity in ISCs and may serve as a biochemical link between the HMGCS2 and the NOTCH signaling pathways.

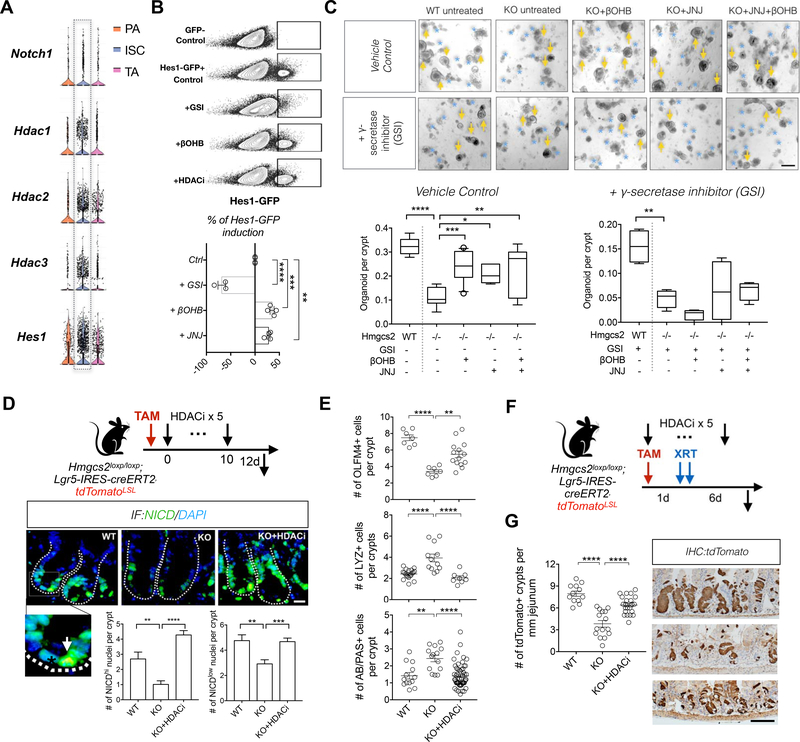

βOHB mediated class 1 HDAC inhibition enhances NOTCH signaling

HMGCS2 is a mitochondrial matrix enzyme and unlikely to physically interact with the NOTCH transcriptional machinery, so we explored the regulatory role of its metabolic product βOHB, which has been reported to be an endogenous inhibitor for class I HDACs(Shimazu et al., 2013). Although the link between HDAC and NOTCH is not well delineated in the mammalian intestine, experimental evidence in model organisms(Yamaguchi et al., 2005) and in other tissues(Hsieh et al., 1999; Kao et al., 1998; Oswald et al., 2002) suggest that HDACs can transcriptionally repress NOTCH target genes. Consistent with this possibility, an earlier study found that the addition of HDAC inhibitors to organoid cultures decreases the niche dependency of Lgr5+ ISCs partly through NOTCH activation(Yin et al., 2014). Our published population-based RNA-seq and scRNA-Seq dataset(Haber et al., 2017) (Data Availability) revealed that Notch receptor (e.g. Notch1), Hdacs (e.g. Hdac1, Hdac2 and Hdac3) and Notch target genes (e.g. Hes1) are enriched in ISCs and that the REACTOME_ NOTCH1_ INTRACELLULAR_ DOMAIN_ REGULATES_ TRANSCRIPTION, which includes Notch and HDACs, ranked as the 2nd highest signature of ISCs from the MSigDB c2 collection of 2864 transcriptional pathways (Figures 5A and S5A). These analyses indicate that ISCs display high Notch activity despite enrichment for repressive HDACs. To test whether enzymatic inhibition of HDACs by βOHB activates NOTCH target gene expression such as Hes1, we exposed Hes1-GFP organoids to βOHB and HDAC1 inhibitor Quisinostat (JNJ-26481585, JNJ) (Figure 5B). Both interventions increased GFP expression compared to control while, as expected, treatment with a γ-secretase inhibitor (GSI, a NOTCH inhibitor) dampened GFP expression.

A, Violin plots of genes related to Figure S5A: Notch receptor Notch1, Class I HDAC genes: HDAC1/2/3 and Notch target Hes1, based on a previously published scRNA-Seq data (Haber et al., 2017). B, Representative flow cytometry plots (top) and quantification of GFP expressiopn (bottom) Hes1-GFP+ primary organoids exposed to γ-secretase inhibitor (GSI, 10uM), βOHB (50uM) and HDAC inhibitor (JNJ-26481585, 0.2nM), compared to control condition. n=6 samples per treatment from n=3 mice. C, Organoid-forming assay for intestinal crypts isolated from WT and Hmgcs2-KO mice, with combinations of HDAC inhibitor JNJ-26481585 (JNJ) or βOHB treatments or Notch receptor inhibitor (GSI, gamma secretase inhibitor). Quantification and representative images: day-5-to-7 organoids. n=4 mice. Scale bar:500 μm. Arrows indicate organoids and asterisks indicate aborted crypts. D, Schematic (top) of the mouse model including the timeline of tamoxifen (TAM) and HDACi (JNJ) injection and tissue collection. Nuclear NICD, a measure of Notch activation, by immunofluorescence (IF). Inset: arrow illustrates NICDhigh nucleus and asterisk indicates NICDlow nucleus. Data (bottom) represents n>25 crypts per measurement, n>3 measurements per mouse and n>3 mice per gourp. Scale bar:20 μm. E, Quantification of OLFM4+ stem cells, LYZ+ Paneth cells and AB/PAS+ goblet cells in proximal jejunal crypts by IHC. F, Schematic of the mouse model including timeline of TAM and HDACi (JNJ) injection, irradiation (XRT, 7.5Gy × 2) and tissue collection. G, Quantification and representative images of tdTomato+ Lgr5+ ISC-derived lineage (cell progenies) by IHC. Scale bar:100 μm. n>25 crypts per measurement, n>3 measurements per mouse and n>5 mice per group. For box-and-whisker plots (C) data were expressed as box-and-whisker 10 to 90 percentiles, Data in bar graph (D) and dot plot (E and G) are expressed as mean+/−s.e.m. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005, ****p<0.0001.

Next, we treated Hmgcs2-null organoids with βOHB, HDAC inhibitors or both and assessed the role of NOTCH in this process by treating a subset of cultures with GSI. Strikingly, we found that HDAC inhibitor Quisinostat (JNJ-26481585, JNJ) at a dose shown to block HDAC1 activity(Arts et al., 2009), as did CRISPR deletion of HDAC1 (Figures 5C and S5G), rescued crypt organoid-forming capacity better than the more promiscuous pan-HDAC class I and II inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA) (Figures 5C and S5F). Also, co-treatment of Quisinostat (JNJ) with βOHB did not further augment crypt organoid-forming capacity, demonstrating redundancy between βOHB signaling and HDAC inhibition (Figure 5C, left). Blockade of NOTCH signaling by GSI treatment prevented the ability of either βOHB or JNJ HDAC inhibitor (Figure 5C, right) to restore the organoid-forming capacity of Hmgcs2-null crypts, indicating that βOHB and HDAC inhibition regulate ISC function through NICD-mediated transcriptional activity (Figure 7F). In parallel experiments, treatment with HDAC1/3 inhibitor (MS-275, 10-to-100nM) rescued Hmgcs2-null organoid function, however, doses beyond this range(Zimberlin et al., 2015) failed to do so (Figure S5F).

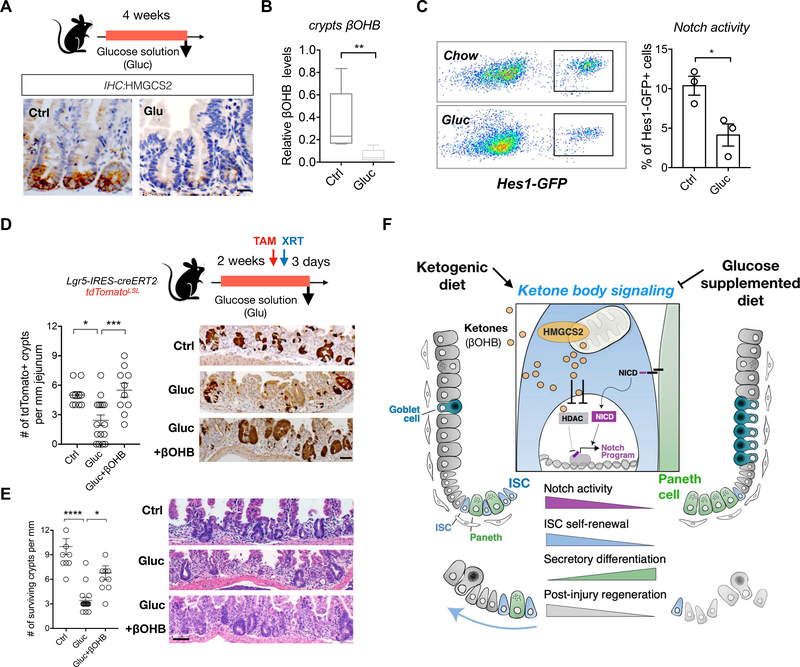

A, Schematic (top) of the mouse model including the timeline of glucose supplementation (Gluc) and tissue collection. After 3–4 weeks of the diet, intestinal tissues of Gluc and Ctrl mice were harvested for histology, crypts culture or sorted by flow cytometry for cell frequency analysis. n>5 mice per group. HMGCS2 expression (bottom) by IHC. The image represents one of 5 biological replicates. Scale bars: 50 μm. B, βOHB levels in intestinal crypts from Gluc and Ctrl mice. Levels of βOHB were normalized to total protein of crypt cells. n= 12 samples from 6 mice per group. C, Hes1-GFP expression, a measure of Notch activation by flow cytometry, of crypt cells from Gluc and Ctrl mice. D-E, Schematic (top) of the Lgr5 lineage tracing including timeline of TAM injection, irradiation (XRT, 7.5Gy × 2) and tissue collection. Quantification and representative images (bottom) of tdTomato+ Lgr5+ ISC-derived progeny labeled by IHC for tdTomato (D) and number of surviving crypts assessed by the microcolony assay (E). Scale bar:100 μm. n>25 crypts per measurement, n>5 measurements per mouse and n>3 mice per group. F, Model of how ketone body (βOHB) signaling dynamically regulates intestinal stemness in homeostasis and in response to diet. In normal dietary states, mitochondrial HMGSCS2-derived βOHB enforces NOTCH signaling through HDAC, class 1 inhibition. Genetic ablation of Hmgcs2 reduces ISC βOHB levels, thereby increasing HDAC-mediated suppression of the NOTCH transcriptional program, which diminishes ISC numbers, function and skews differentiation towards the secretory lineage. Ketogenic diets (KTD) enhance both systemic and stem cell produced βOHB levels in ISCs, leading to higher NOTCH activity, ISC function, and post-injury regeneration. In contrast, glucose supplemented diets suppress ketogenesis and have the opposite effects on intestinal stemness. Thus, we propose that dynamic control of ISC βOHB levels enables it to serve as a metabolic messenger to execute intestinal remodeling in response to diverse physiological states.

To bolster the connection between HMGCS2-mediated control of HDAC activity and NOTCH signaling in vivo, we found that Hmgcs2-loss and ketone depletion (Figure 4D) decreased the numbers of H3K27ac or NICD positive crypt cell nuclei, which correlates with greater HDAC activity and less NOTCH signaling (Figures 5D and S5H). Consistent with the paradigm that βOHB hinders HDAC1 activity, robust in vivo induction of Hmgcs2 (Mihaylova et al., 2018; Tinkum et al., 2015) and βOHB levels in the crypts with a 24 hour fast (Figure S5B) associated with greater H3K27ac enrichment peaks compared to controls by ChIP-seq (Figure S5C). Moreover, this trend also holds true at gene enhancer and promoter sites (−/+5kbTSS), including at Hes1 (Figures S5D and S5E). Importantly, HDAC inhibitor treatment (JNJ, 1 mg/kg, 5 i.p. injections) of Hmgcs2-null mice not only prevented these changes, but also rescued the decline in ISCs numbers (Figure 5E), ISC function after injury (Figures 5F and andG)G) and the expansion of secretory cell types (Figure 5E and Figure S5G). These data collectively support the notion that βOHB drives the downstream effects of HMGCS2 through the inhibition of class I HDACs to stimulate NOTCH signaling for stemness (Figure 6H).

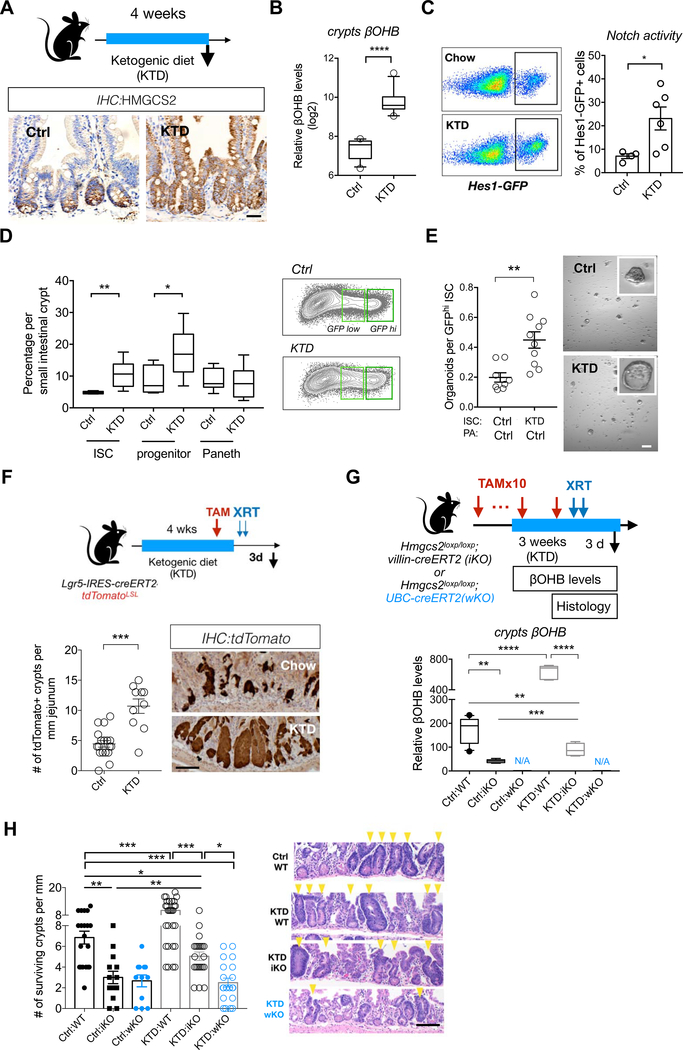

A, Schematic (top) of the mouse model including the timeline of ketogenic diet (KTD) and tissue collection. After 3–4 weeks of the diet, intestinal tissues of KTD-fed or chow-fed (Ctrl) mice were harvested for histology, crypts culture or sorted by flow cytometry for cell frequency analysis. n>5 mice per group. HMGCS2 expression (bottom) by IHC. The image represents one of 5 biological replicates. Scale bars: 50 μm. B, βOHB levels in intestinal crypts from KTD- and Chow-fed mice. Levels of βOHB were normalized to total protein of crypt cells. n= 12 samples from 6 mice per group. C, Hes1GFP expression, a measure of Notch activation by flow cytometry, of crypt cells from KTD- and Chow-fed mice. D, Frequencies of Lgr5-GFPhi ISCs, Lgr5-GFPlow progenitors and CD24+c-Kit+ Paneth cells in crypts from KTD- and Chow-fed mice. n=6 mice per group. E, Organoid-forming assay for sorted ISCs from KTD and Chow mice, co-cultured with Paneth cells from Chow mice. n=6 mice per group. representative images: day 5 organoids. Scale bar: 100um. F, Schematic (top) of the Lgr5 lineage tracing including timeline of TAM injection, irradiation (XRT, 7.5Gy × 2) and tissue collection. Intestinal tissues were harvested for histology and intestinal crypts were isolated for βOHB measurement at the indicated time points. Quantification and representative images (bottom) of tdTomato+ Lgr5+ ISC-derived progeny labeled by IHC for tdTomato. For G-H, Schematic (top) of intestinal Hmgcs2-deletion (iKO) and whole-body Hmgcs2-deletion (wKO) mice on KTD, including timeline of TAM injection, irradiation (XRT, 7.5Gy × 2) and tissue collection. βOHB levels (bottom) in intestinal crypts isolated from the indicated groups (G), number of surviving crypts assessed by the microcolony assay (H). For F and H, Scale bar:100 μm. n>25 crypts per measurement, n>5 measurements per mouse and n>3 mice per group. Data in dot plots (C,E and F) are expressed as mean+/−s.e.m. For (B,D and G), Box-and-whisker 10 to 90 percentiles. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ****p<0.001.

Ketogenic diet boosts ISCs numbers and function

Because HMGCS2-derived ketones in ISCs promote self-renewal and prevent premature differentiation, we asked whether a ketogenic diet (KTD, Methods), an intervention that dramatically elevates circulating ketone body levels(Newman et al., 2017), enhances ISC numbers, function, or both. Lgr5+ reporter mice fed a KTD for 4–6 weeks show no change in body mass, intestinal length or crypt depths and have a 3.5-fold increase in plasma βOHB level compared to chow controls (Figures 6A and S6A–S6D). In the intestine, a KTD pronouncedly not only boosted HMGCS2 protein expression throughout the entire crypt/villous unit (Figures 6A) that correlated with a 6.8-fold elevation in crypt βOHB concentrations (Figure 6B) but also enhanced NOTCH activity by 2-fold as measured flow cytometrically for HES1-GFP positivity (Figure 6C), NICD nuclear localization (Figure S6F), and OLFM4 protein expression (a NOTCH target gene, Figure S6E)(Tian et al., 2015; VanDussen et al., 2012). In addition, KTD mice had greater numbers of Lgr5-GFPhi/ OLFM4+ ISCs and Lgr5-GFPlow progenitors (Figures 6D and S6E) with higher rates of proliferation for ISCs, but not for progenitor cells, as determined after a 4-hour BrdU pulse (Figure S6H)..

Not only did a KTD lead to quantitative changes in ISCs, both KTD crypts and KTD-derived ISCs in Paneth cell co-culture assays were more capable of forming organoids compared to controls (Figures 6E and S6F). Similarly, a KTD also boosted the regenerative output of tdTomato-labeled ISCs after radiation-induced damage relative to their chow counterparts (Figure 4F). Since exogenous ketones rectify Hmgcs2 loss in vitro (Figure S4L) and in vivo (Figure 4F), liver or other non-intestinal sources of ketones may substitute for or supplement ISC-generated ketones in KTD-mediated regeneration (Figure 4F) where plasma ketone levels are highly elevated (Figure S6B). To distinguish between the contribution of plasma ketones versus intestinal ketones in this process, we engineered Hmgcs2loxp/loxp; UBC-CreERT2 conditional whole-body knockout mice that disrupts Hmgcs2 in all adult cell types upon tamoxifen administration (Figure 6G, termed wKO). Although Hmgcs2 loss in the iKO model significantly lowered crypt βOHB levels in a KTD, it was still higher than levels noted in control iKO crypts. This difference is likely due to uptake of circulating plasma ketones induced by the KTD (Figure 6G) as crypt βOHB levels were undetectable in control or KTD crypts from wKO mice (Figure 6G). Remarkably, this pattern of crypt βOHB concentration mirrored the numbers of intact surviving crypts after radiation-induced intestinal epithelial injury (Figure 6H). While the pro-regenerative effects of a KTD were blunted by intestinal Hmgcs2 loss, they were entirely blocked with whole body Hmgcs2 loss, demonstrating that βOHB regulates ISCs in a cell autonomous and non-autonomous manner in ketogenic states (Figure 6H).

Although exogenous βOHB in a KTD restored the in vivo lineage differentiation defects and crypt organoid-forming capacity in Hmgcs2-null intestines (Figure S6M), neither a KTD nor exogenous βOHB exposure in wild-type intestines or organoids impacted secretory cell lineage differentiation (Figures S6G to S6J). This finding indicates that while surplus intestinal βOHB bolsters ISC self-renewal (i.e. ISC numbers, proliferation, and in vitro and in vivo function) and NOTCH signaling, it is not sufficient to suppress secretory differentiation in Hmgcs2-compentent ISCs. This disconnect between excessive (i.e. supraphysiologic) NOTCH activity in driving stemness but not in inhibiting secretory differentiation has been previously documented in conditional genetic models of enforced NOTCH signaling in the adult intestine (Vooijs et al., 2011; Zecchini et al., 2005).

A glucose-supplemented diet dampens intestinal ketogenesis and stemness

Ketogenesis is an adaptive response to dietary shortages of carbohydrates, where in low carbohydrate states liver-derived ketone bodies are utilized by peripheral tissues for energy (Newman and Verdin, 2017; Puchalska and Crawford, 2017). In the presence of dietary glucose, for example, hepatic HMGCS2 expression and ketone body production rapidly switch off in response to insulin(Cotter et al., 2013). To investigate how a glucose-supplemented diet alters ISCs, we fed mice a chow diet with glucose supplemented drinking water (13% glucose in drinking water, ad libitum) for 4 weeks (Figure 7A), where mice consumed 2.68+/−0.5ml of the glucose solution (per mouse per day). While 4-week glucose supplementation did not induce obesity (Figure S7A), this regimen significantly diminished HMGCS2 expression at the crypt base (Figure 7A) and reduced crypt βOHB levels (Figure 7B). This dietary suppression of intestinal ketogenesis was accompanied by a 2-fold decrease in Hes1 expression, confirming that NOTCH activity correlates with βOHB concentrations (Figure 7C). Similar to intestinal Hmgcs2 loss (Figure 2), mice on this regimen had 3-fold fewer OLFM4+ ISCs and greater Lyz1+ Paneth cell and AB+ goblet cell numbers (Figures S7B to S7D). Functionally, a 2-week course of glucose supplementation hampered the ability of ISCs by 2-fold to generate tdTomato+ labeled progeny in lineage tracing experiment with radiation-induced injury (Figure 7D) and separately decreased surviving intact crypt numbers compared to controls (Figure 7E). These functional deficits could be rescued by a single oral bolus of βOHB (15mg/25g βOHB oligomers, 16hrs prior to irradiation) (Figures 7D and and7E).7E). These results illustrate that dietary suppression of βOHB production mimics many aspects of Hmgcs2 loss and that exogenous ketone bodies can compensate for these deficits.

DISCUSSION

Our data favor a model in which small intestinal Lgr5+ ISCs express the enzyme 3-hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl-CoA Synthase 2 (i.e., HMGCS2) that produces ketone bodies including acetoacetate, acetate, and beta-hydroxybutyrate (βOHB) to regulate intestinal stemness(Newman and Verdin, 2017)(Figure 6H). Although ketone bodies are known to provide energy to tissues during periods of low energy states such as fasting or prolonged exercise, they have also been implicated as signaling metabolites that inhibit the activity of class I histone deacetylase (HDACs)(Newman and Verdin, 2017; Shimazu et al., 2013). A recent study(Wang et al., 2017) implicated HMGCS2-mediated ketogenesis as promoting secretory differentiation with loss-of-function studies in immortal colon cell lines and with a ketone supplemented diet, which contrasts with our findings. This discrepancy highlights the importance of robust in vivo loss-of-function models, where we generated separate alleles that target in vivo Hmgcs2 expression (i.e. the LacZ and loxp models)(Wang et al., 2017). Here, we identify novel roles for βOHB as a signaling metabolite in Lgr5+ ISCs that facilitates NOTCH signaling—a developmental pathway that regulates stemness and differentiation in the intestine—through HDAC inhibition (Figure 7F). Thus, we propose that dynamic control of βOHB levels in ISCs enables this metabolic messenger to execute rapid intestinal remodeling in response to diverse physiological states (Figure 7F).

A challenge is how to optimally model and reconcile βOHB-mediated partial class 1 HDAC enzymatic inhibition with genetic loss-of-function approaches in the intestine. Two independent groups(Gonneaud et al., 2015; Zimberlin et al., 2015) demonstrated loss of secretory differentiation with combined Hdac1 and Hdac2 intestinal loss, which is consistent with a Notch phenotype and our model (Figure 6H). However, these two groups came to different conclusions regarding how loss of Hdac1 and 2 impact crypt proliferation with one model(Gonneaud et al., 2015) showing crypt hyperplasia and proliferation, using an inducible intestinal specific Villin-CreERT2 allele, and the other model(Zimberlin et al., 2015) showing crypt loss and reduced proliferation, using an inducible Ah-Cre allele that is expressed in the intestine and liver. The Ah-Cre model reportedly(Gonneaud et al., 2015) causes greater DNA damage and is not specific to the intestine, which cannot exclude non-intestinal effects. Regardless, as proposed by others(Haberland et al., 2009), genetic ablation of Hdac members irreversibly eliminates HDAC enzymatic activity and permanently disrupts all complexes seeded by HDACs throughout the genome. In contrast, HDAC inhibitors, similar to βOHB, temporarily inhibit enzymatic activity without abolishing the co-repressor complexes(Haberland et al., 2009), thus pharmacologic or βOHB-mediated reversible inhibition of HDACs need not phenocopy permanent genetic loss in vivo.

Many lines of evidence indicate that NOTCH signaling is undergirding the effects of HMGCS2 in Lgr5+ ISCs: First, Hmgcs2 loss leads to a gradual decrease in the expression and number of OLFM4+ cells within the crypt (Figure 2D), which is a stem-cell marker dependent on NOTCH signaling(VanDussen et al., 2012). Second, Hmgcs2 loss emulates many of the characteristics of intestinal-specific Notch1 deletion with expansions in goblet and Paneth cell populations (Figures 2E, ,2F,2F, S2G, ,3A3A–H) (Fre et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2014; Sancho et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2001). Third, Hmgcs2 loss dampens NOTCH target gene expression, perturbs NOTCH-mediated lateral inhibition (Figures 3H and and3I)3I) and primes ISCs to adopt an early Paneth cell fate (Figures 3F,,3G3G,S3G and S3H). Lastly, these deficits correlate with a reduction in the number of NICD positive intestinal crypt cell nuclei (Figure 5D) and constitutive NOTCH activity remedies Hmgcs2-null organoid function (Figure 3J).

As Lgr5+ ISCs receive NOTCH ligand stimulation (e.g. Dll1 and Dll4) from their Paneth cell niche, an important question is why do small intestinal Lgr5+ ISCs reinforce NOTCH signaling with endogenous ketones? One possible answer is that stem cells, in contrast to lateral NOTCH inhibition in non-ISC progenitor cells that are higher up in the crypt, depend on greater NOTCH activity to maintain stemness and prevent their premature differentiation into Paneth cells (Figures 3G and S3G). These redundant pathways that stimulate NOTCH signaling in Lgr5+ ISCs may, for example, permit these cells to persist when Paneth cells are depleted with diphtheria toxic(Sato et al., 2011) or in other genetic models(Durand et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2012a; Yang et al., 2001) such as with intestinal Atoh1-loss (Figures 4C,S4E and S4F).

Another possibility is that systemic and intestinal βOHB production provides a signaling circuit that couples organismal diet and metabolism to intestinal adaptation (Barish et al., 2006; Beyaz et al., 2016; Ito et al., 2012; Narkar et al., 2008). For example, we previously reported that diets that induce ketogenic states such as fasting (Mihaylova et al., 2018), high fat diets (Beyaz et al., 2016) and ketogenic diets (Figure 6 and and7E)7E) strongly induce PPAR (Peroxisome Proliferator-activated Receptor) transcriptional targets in ISCs that also includes Hmgcs2 (Figure S2E). Furthermore, these ketogenic states coordinately drive βOHB production in the liver (which accounts for plasma levels) and in the intestine, which both then stimulate a ketone body-mediated signaling cascade in stem cells that bolsters intestinal regeneration after injury (Figure F-H). We propose that βOHB actuates the ISC-enhancing effects of these ketone-generating diets by functioning downstream of PPAR-delta signaling to reinforce NOTCH activity. Supporting this supposition, we find that a ketogenic diet boosts not only crypt βOHB levels but also ISC numbers, function and NOTCH signaling. The converse occurs in glucose rich diets where βOHB levels are suppressed as are ISC numbers, function and NOTCH signaling. An interesting implication of our work is to understand the cancer implications of ISC-promoting ketogenic diets, given that some intestinal cancers arise from ISCs (Barker et al., 2009) and that ketogenic diets in some mouse strains improve health and mid-life survival(Newman et al., 2017). Future studies will need to further explore (i.) the cancer consequences of our model, (ii.) the energetic and NOTCH independent signaling roles that ketone bodies play in intestinal stemness and, (iii.) the cell non-autonomous roles of ISC-derived ketone bodies on stromal, immune and microbial elements in stem cell microenvironment.

STAR METHODS

LEAD CONTACT AND MATERIALS AVAILABILITY

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Omer H. Yilmaz (ude.tim@zamliyho).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Animal

Mouse strains. Hmgcs2-lacZ reporter and conditional loxp mice were generated using a knockout-first strategy(Skarnes et al., 2011) to functionally validate whether Hmgcs2-expressing cells harbor function ISC activity and whether Hmgcs2 is necessary for ISC maintenance. The knockout-first combines the advantage of both a reporter-tagged and a conditional mutation. Briefly, a cassette containing mouse En2 splicing acceptor (SA), LacZ, and promoter-driven neomycin resistant gene (Neo) is inserted in introns of target genes. The initial allele (Hmgcs2-Vector, V)(KOMP: PG00052_Z_4_A06) is predicted to generate a null allele through splicing to the LacZ trapping element. Targeted clones therefore report endogenous gene expression and carry null mutation (Figures 2A and S2A). Successful targeting was validated by Southern blotting and PCR analysis (Figure S2B). Conditional alleles (Hmgcs2-loxP, L) can be generated by removal of the gene trap cassette using Flp recombinase. To investigate the necessity of Hmgcs2 in maintaining ISC functions, we generated Hmgcs2loxp/loxp mice and crossed them to Lgr5-eGFP-IRES-CreERT2(Barker et al., 2007) and to Lgr5-CreERT2; tdTomatoLSL(Huch et al., 2013) reporter mice separately. CRE-mediated excisions in sorted GFP+ cells and in tdTomato+ crypt cells were both confirmed by PCR (Figures S2B and S2E). Lgr5-CreERT2; tdTomatoLSL were generated by crossing Lgr5-IRES-CreERT2 mice (a gift from Dr. Hans Clevers)(Huch et al., 2013) to tdTomatoLSL mice (Jackson Laboratory, #007909). Hmgcs2loxp/loxp;Villin-CreERT2 mice were generated by crossing Hmgcs2loxp/loxp mice to Villin-CreERT2 mice (el Marjou et al., 2004). Atoh1(Math1)L/L;Villin-CreERT2 mice were generated by crossing Atoh1(Math1)L/L mice to Villin-CreERT2 mice (Shroyer et al., 2007). Hes1-GFP reporter mice were previously described (Lim et al., 2017). In this study, both male and female mice were used at the ages of 3–5 months unless otherwise specified in the figure legends.

Organoids

Hes1-GFP organoids were generated from adult male and female Hes1-GFP reporter mice (Lim et al., 2017). Primary NICD-GFPLSL organoids were generated from adult male RosaN1-IC mice (Jackson Laboratory, #008159). Primary organoids were cultured in the CO2 incubator (37°C, 5% CO2) using the compl ete crypt culture medium, as described in METHOD DETAILS: Crypt Isolation and culturing) (Mihaylova et al., 2018).

Human intestinal samples

Human duodenal biopsies that were diagnosed as normal were obtained from 10 patients (n=4 19-to-20-year-old females, n=3 81-to-84-year-old females and n=3 19-to-20-year-old males). The MGH Institutional Review Board committee approved the study protocol.

METHOD DETAILS

In vivo treatments

Tamoxifen treatment. Tamoxifen injections were achieved by intraperitoneal (i.p.) tamoxifen injection suspended in sunflower seed oil (Spectrum S1929) at a concentration of 10 mg/ml, 250ul per 25g of body weight, and administered at the time points indicated in figures and figure legends. Irradiation experiments. Mice were challenged by a lethal dose of irradiation (7.5Gy × 2, 6 hours apart). Intestine tissues were collected for histology 5 days after ionizing irradiation-induced (XRT). Exogenous βOHB treatments: Mice received a single oral dose of βOHB-encapsulated PLGA nanoparticles (16.67mg/25g in 500ul) or βOHB oligomers (15mg/25g in 500ul) 16hrs prior to irradiation. See also supplemental methods for preparation of βOHB nanoparticles and oligomers. HDAC inhibitor treatments. Mice received up to 5 injections (i.p.) of vehicle (2% DMSO+30% PEG 300+ddH2O) or Quisinostat (JNJ-26481585) 2HCl (1 mg/kg per injection). Ketogenic diet (KTD). Per-calorie macronutrient content: 15 kcal protein, 5 kcal carbohydrate and 80 kcal fat per 100 kcal KTD (Research diet, Inc. D0604601). See also supplement table 4 for the ingredient composition. Food was provided ad libitum at all times. The fat sources are Crisco, cocoa butter, and corn oil. Glucose solution. Glucose supplement was prepared by adding 13g D-(+)-Glucose (Sigma, Cat. #G8270) into 100 ml drinking water of mice. Unless otherwise specified in figure legends, all experiments involving mice were carried out using adult male and female mice (n>3 per group), with approval from the Committee for Animal Care at MIT and under supervision of the Department of Comparative Medicine at MIT. See also QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS for general information related to experimental design.

Beta-Hydroxybutyrate (βOHB) measurements

Serum βOHB. Blood was obtained via submandibular vein bleed (10–40 uL). Blood was collected into an eppendorf tube and allowed to clot for 15–30 minutes at room temperature. Serum was separated by centrifugation at 1500 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Serum samples were frozen at −80°C until thawed for assay. Crypts βOHB. Intestinal crypts freshly isolated in PBS were aliquoted into two samples. Samples were pelleted (centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 minutes) and re-suspended in lysis buffer of BCA assay (Thermofisher, # 23225) for measuring total proteins and that for Beta-Hydroxybutyrate measurements (Cayman, #700190). Level of crypts βOHB was normalized to total proteins of each sample.

Crypt Isolation and culturing

As previously reported and briefly summarized here (Mihaylova et al., 2018), small intestines were removed, washed with cold PBS, opened longitudinally and then incubated on ice with PBS plus EDTA (10 mM) for 30–45 min. Tissues were then moved to PBS. Crypts were then mechanically separated from the connective tissue by shaking or by scraping, and then filtered through a 70-μm mesh into a 50-ml conical tube to remove villus material and tissue fragments. Isolated crypts for cultures were counted and embedded in Matrigel™ (Corning 356231 growth factor reduced) at 5–10 crypts per μl and cultured in a modified form of medium as described previously(Sato et al., 2009; Yilmaz et al., 2012). Unless otherwise noted, crypt culture media consists of Advanced DMEM (Gibco) that was supplemented with EGF 40 ng ml−1 (PeproTech), Noggin 200 ng ml−1 (PeproTech), R-spondin 500 ng ml−1 (R&D, Sino Bioscience or (Ootani et al., 2009)), N-acetyl-L-cysteine 1 μM (Sigma-Aldrich), N2 1X (Life Technologies), B27 1X (Life Technologies), CHIR99021 3μM (LC laboratories), and Y-27632 dihydrochloride monohydrate 10uM (Sigma-Aldrich). Intestinal crypts were cultured in the above mentioned media in 20–25μL droplets of Matrigel™ were plated onto a flat bottom 48-well plate (Corning 3548) and allowed to solidify for 20–30 minutes in a 37°C incubator. Three hundred microliters of c rypt culture medium was then overlaid onto the Matrigel™, changed every three days, and maintained at 37°C in fully humidified chambers containing 5% CO2. Clonogenicity (colony-forming efficiency) was calculated by plating 50–300 crypts and assessing organoid formation 3–7 days or as specified after initiation of cultures. Beta-hydroxybutyrate (Sigma, 54965), Quisinostat (JNJ-26481585) 2HCl (Selleckchem, S1096), Entinostat (MS-275) (Selleckchem, S1053), Trichostatin A (Selleckchem, S1045) and γ-secretase inhibitor MK-0752 (Cayman Chemical Company, 471905–41-6) were added into cultures as indicated in the figure legends. Plasmids for Hdac1 CRISPR-deletion (sc-436647), Cre-expression (sc-418923), Cre-expression and Hmgcs2 CRISPR-deletion (VB180615–1103gue) were used for organoid transfection according to manufacturers’ instructions.

μM (Sigma-Aldrich), N2 1X (Life Technologies), B27 1X (Life Technologies), CHIR99021 3μM (LC laboratories), and Y-27632 dihydrochloride monohydrate 10uM (Sigma-Aldrich). Intestinal crypts were cultured in the above mentioned media in 20–25μL droplets of Matrigel™ were plated onto a flat bottom 48-well plate (Corning 3548) and allowed to solidify for 20–30 minutes in a 37°C incubator. Three hundred microliters of c rypt culture medium was then overlaid onto the Matrigel™, changed every three days, and maintained at 37°C in fully humidified chambers containing 5% CO2. Clonogenicity (colony-forming efficiency) was calculated by plating 50–300 crypts and assessing organoid formation 3–7 days or as specified after initiation of cultures. Beta-hydroxybutyrate (Sigma, 54965), Quisinostat (JNJ-26481585) 2HCl (Selleckchem, S1096), Entinostat (MS-275) (Selleckchem, S1053), Trichostatin A (Selleckchem, S1045) and γ-secretase inhibitor MK-0752 (Cayman Chemical Company, 471905–41-6) were added into cultures as indicated in the figure legends. Plasmids for Hdac1 CRISPR-deletion (sc-436647), Cre-expression (sc-418923), Cre-expression and Hmgcs2 CRISPR-deletion (VB180615–1103gue) were used for organoid transfection according to manufacturers’ instructions.

If not directly used for cultures, crypts were then dissociated into single cells and sorted by flowcytometry. Isolated ISCs or progenitor cells were centrifuged at 300g for 5 minutes, re-suspended in the appropriate volume of crypt culture medium and seeded onto 20–25 μl Matrigel™ (Corning 356231 growth factor reduced) containing 1 μM JAG-1 protein (AnaSpec, AS-61298) in a flat bottom 48-well plate (Corning 3548). Alternatively, ISCs and Paneth cells were mixed after sorting in a 1:1 ratio, centrifuged, and then seeded onto Matrigel™. The Matrigel™ and cells were allowed to solidify before adding 300 μl of crypt culture medium. The crypt media was changed every third day.

RT-PCR and In Situ Hybridization

25,000 cells were sorted into Tri Reagent (Life Technologies), and total RNA was purified according to the manufacturer’s instructions with following modification: the aqueous phase containing total RNA was purified using RNeasy plus kit (Qiagen). RNA was converted to cDNA with cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). qRT-PCR was performed with diluted cDNA (1:5) in 3 wells for each primer and SYBR green master mix on Roche LightCycler® 480 detection system. Primers used are previously described6. Single-molecule in situ hybridization was performed using Advanced Cell Diagnostics RNAscope 2.0 HD Detection Kit (Fast Red dye) for the following probes: Mm-Hmgcs2, Mm-Hes1, Mm- Atoh1. Mm-Lgr5. For IHC and ISH co-staining, after signal detection of Lgr5 ISH, slides were dried and proceeded with regular IHC for HMGCS2 staining.

Immunostaining and Immunoblotting

As previously described(Beyaz et al., 2016; Rickelt and Hynes, 2018; Yilmaz et al., 2012), tissues were fixed in 10% formalin, paraffin embedded and sectioned. Antigen retrieval was performed with Borg Decloaker RTU solution (Biocare Medical) in a pressurized Decloaking Chamber (Biocare Medical) for 3 minutes. Antibodies used for immunohistochemistry: rabbit anti-HMGCS2 (1:500, Abcam ab137043), rat anti-BrdU (1:2000, Abcam 6326), rabbit monoclonal anti-OLFM4 (1:10,000, gift from CST, clone PP7), rabbit polyclonal anti-lysozyme (1:250, Thermo RB-372-A1), rabbit anti-chromogranin A (1:4,000, Abcam 15160), rabbit Cleaved Caspase-3 (1:500, CST #9664), rabbit polyclonal anti-RFP (1:500, Rockland 600–401-379), goat polyclonal anti-Chromogranin A (1:100, Santa Cruz sc-1488). Biotin-conjugated secondary donkey anti-rabbit or anti-rat antibodies were used from Jackson ImmunoResearch. The Vectastain Elite ABC immunoperoxidase detection kit (Vector Labs PK-6101) followed by Dako Liquid DAB+ Substrate (Dako) was used for visualization. Antibodies used for immunofluorescence: tdTomato and Lysozyme immunofluorescence costaining, Alexa Fluor 488 and 568 secondary antibody (Invitrogen). For NICD and H3K27ac staining, antibodies rabbit anti-Cleaved Notch1 (CST, #4147), rabbit anti-H3K27ac (CST,#8173) and TSA™ Alexa Fluor 488 tyramide signal amplification kit (Life Technologies, T20948) was used. Slides were stained with DAPI (2 μg/mL) for 1 min and covered with Prolong Gold (Life Technologies) mounting media. All antibody incubations involving tissue or sorted cells were performed with Common Antibody Diluent (Biogenex). The following antibodies were used for western blotting: anti-HMGCS2 (1:500, Sigma AV41562) and anti- alpha tubulin (1:3000, Santa Cruz sc- 8035). Single cell western blotting was performed using Proteinsimple Milo™ system according to manufacturer’s instructions. Anti-HDAC1 antibody (1:200, ab53091) was used to detect HDAC1 levels by flow cytometry and analyzed using FlowJo.

13C-Palmitate labeling and LC/MS Methods

13C-Palmitate labeling assay were performed as previously described in (Mihaylova et al., 2018). Briefly, intestinal crypts were isolated from mice and incubated in RPMI media containing above mentioned crypt components and 30mM 13C-Palmitate for 60 minutes and metabolites were extracted for LC/MS analysis.

Population RNA-Seq analysis

Reads were aligned against the mm10 murine genome assembly, with ENSEMBL 88 annotation, using v. STAR 2.5.3a, with flags --runThreadN 8 --runMode alignReads --outFilterType BySJout --outFilterMultimapNmax 20 --alignSJoverhangMin 8 --alignSJDBoverhangMin 1 --outFilterMismatchNmax 999 --alignIntronMin 10 --alignIntronMax 1000000 --alignMatesGapMax 1000000 --outSAMtype BAM SortedByCoordinate --quantMode TranscriptomeSAM pointing to a 75nt-junction STAR genome suffix array(Dobin et al., 2013). Quantification was performed using RSEM with flags --forward-prob 0 --calc-pme --alignments -p 8(Li and Dewey, 2011). The resulting posterior mean estimates of read counts were retrieved and used for differential expression analysis using the edgeR package, in the R 3.4.0 statistical framework(McCarthy et al., 2012). In the absence of replicates, pairwise comparisons of samples/conditions were performed using an exact test with a dispersion set to bcv-squared, where bcv value was set to 0.3. For pooled analyses (with samples pooled by their ISC, Progenitor or Paneth cell status), exact tests were similarly performed, with dispersions estimated from the data using the estimateDisp function. Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-values and log2-fold-changes were retrieved and used for downstream analyses.

GSEA analysis of bulk RNA-Seq

The command-line version of the GSEA tool(Subramanian et al., 2005) was used to analyze potential enrichment of interesting gene sets affected by age, diet, etc. Genes were ranked according to their log2(FoldChange) values and analyzed using the “pre-ranked” mode of the GSEA software using the following parameters: -norm meandiv-nperm 5000 -scoring_scheme weighted -set_max 2000 -set_min 1 -rnd_seed timestamp. The MSigDB C2 collection was analyzed and the c2_REACTOME_SIGNALING_BY_NOTCH.gmt dataset was plotted using GSEA.

Droplet scRNA-seq

Cells were sorted with the same parameters as described above for flow-cytometry into into an Eppendorf tube containing 50μl of 0.4% BSA-PBS and stored on ice until proceeding to the Chromium Single Cell Platform. Single cells were processed through the Chromium Single Cell Platform using the Chromium Single Cell 3’ Library, Gel Bead and Chip Kits (10X Genomics, Pleasanton, CA), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, an input of 7,000 cells was added to each channel of a chip with a recovery rate of 1,500–2,500 cells. The cells were then partitioned into Gel Beads in Emulsion (GEMs) in the Chromium instrument, where cell lysis and barcoded reverse transcription of RNA occurred, followed by amplification, tagmentation and 5’ adaptor attachment. Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq 500.

Droplet scRNA-seq data processing

Alignment to the mm10 mouse genome and unique molecular identifier (UMI) collapsing was performing using the Cellranger toolkit (version 1.3.1, 10X Genomics). For each cell, we quantified the number of genes for which at least one UMI was mapped, and then excluded all cells with fewer than 1,000 detected genes. We then identified highly variable genes. Variable gene selection. A logistic regression was fit to the cellular detection fraction (often referred to as α), using the total number of UMIs per cell as a predictor. Outliers from this curve are genes that are expressed in a lower fraction of cells than would be expected given the total number of UMIs mapping to that gene, i.e., cell-type- or state-specific genes. We controlled for mouse-to-mouse variation by providing mouse labels as a covariate and selecting only genes that were significant in all mice, and used a threshold of deviance<−0.1, producing a set of 806 variable genes. Known cell-cycle genes (either part of a cell-cycle signature(Kowalczyk et al., 2015) or in the Gene Ontology term ‘Cell-Cycle’: GO:0007049) were excluded, resulting in a set of 672 variable genes. Dimensionality reduction. We restricted the expression matrix to the subsets of variable genes and high-quality cells noted above, and then centered and scaled values before inputting them into principal component analysis (PCA), which was implemented using the R package ‘Seurat’ version 2.3.4. Given that many principal components explain very little of the variance, the signal-to-noise ratio can be improved substantially by selecting a subset of n top principal components, we selected 13 principal components by inspection of the ‘knee’ in a scree plot. Scores from only these principal components were used as the input to further analysis. Batch correction and clustering. Both prior knowledge and our data show that different cell types have differing proportions in the small intestine. This makes conventional batch correction difficult, as, due to random sampling effects, some batches may have very few of the rarest cells. To avoid this problem, we performed an initial round of unsupervised clustering using k-nearest neighbor (kNN) graph-based clustering, implemented in Seurat using the ‘FindClusters’ function, using a resolution parameter of 1. We next performed batch correction within each identified cluster (which contained only transcriptionally similar cells) ameliorating problems with differences in abundance. Batch correction was performed (only on the 672 variable genes) using ComBat(Johnson et al., 2007) as implemented in the R package sva(Leek et al., 2012) using the default parametric adjustment mode. Following this batch correction step, we re-ran PCA and kNN-based clustering to identify the final clusters (resolution parameter=0.25). Visualization. For visualization, the dimensionality of the datasets was further reduced using the ‘Barnes-hut’ approximate version of t-SNE(Haber et al., 2017) (http://jmlr.org/papers/v15/vandermaaten14a.html) as implemented in the Rtsne function from the ‘Rtsne’ R package using 1,000 iterations and a perplexity setting of 60. Testing for changes in cell-type proportions. To assess the significance of changes in the proportions of cells in different clusters, we used a negative binomial regression model to model the counts of cells in each cluster, while controlling for any mouse-to-mouse variability amongst our biological replicates. For each cluster, we model the number of cells detected in each analyzed mouse as a random count variable using a negative binomial distribution. The frequency of detection is then modeled by using the natural log of the total number of cells profiled in a given mouse as an offset. The condition of each mouse (i.e., knock-out or wild-type) is then provided as a covariate. The negative binomial model was fit using the R command ‘glm.nb’ from the ‘MASS’ package. The p-value for the significance of the effect produced by the knock-out was then assessed using a likelihood-ratio test, computing using the R function ‘anova’. Scoring cells using signature gene sets. To obtain a score for a specific set of n genes in a given cell, a ‘background’ gene set was defined to control for differences in sequencing coverage and library complexity. The background gene set was selected to be similar to the genes of interest in terms of expression level. Specifically, the 10n nearest neighbors in the 2-D space defined by mean expression and detection frequency across all cells were selected. The signature score for that cell was then defined as the mean expression of the n signature genes in that cell, minus the mean expression of the 10n background genes in that cell. Violin plots to visualize the distribution of these scores were generated using the R package ‘ggplot2’. We scored cells in this manner for Paneth cell markers(Haber et al., 2017), proliferation(Kowalczyk et al., 2015), apoptosis(Dixit et al., 2016), and intestinal stem cell markers(Munoz et al., 2012b). Enrichment analysis. Enrichment analysis was performed using the hypergeometric probability computed in R using ‘phyper’. Differential expression and cell-type signatures. To identify maximally specific genes for cell-types, we performed differential expression tests between each pair of clusters for all possible pairwise comparisons. Then, for a given cluster, putative signature genes were filtered using the maximum FDR Q-value and ranked by the minimum log2 fold-change of means (across the comparisons). This is a stringent criterion because the minimum fold-change and maximum Q-value represent the weakest effect-size across all pairwise comparisons. Cell-type signature genes for the initial droplet based scRNA-seq data were obtained using a maximum FDR of 0.001 and a minimum log2 fold-change of 0.1. Differential expression tests were carried using a two part ‘hurdle’ model to control for both technical quality and mouse-to-mouse variation. This was implemented using the R package MAST(Finak et al., 2015), and p-values for differential expression were computed using the likelihood-ratio test. Multiple hypothesis testing correction was performed by controlling the false discovery rate (FDR) using the R function ‘p.adjust’, and results were visualized using ‘volcano’ plots constructed using ‘ggplot2’. Code availability. R scripts enabling the main steps of the analysis to be reproduced are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

ChIP-sequencing analysis