Abstract

Free full text

The Impact of PI3-kinase/RAS Pathway Cooperating Mutations in the Evolution of KMT2A-rearranged Leukemia

Associated Data

Abstract

Leukemia is an evolutionary disease and evolves by the accrual of mutations within a clone. Those mutations that are systematically found in all the patients affected by a certain leukemia are called “drivers” as they are necessary to drive the development of leukemia. Those ones that accumulate over time but are different from patient to patient and, therefore, are not essential for leukemia development are called “passengers.” The first studies highlighting a potential cooperating role of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/RAS pathway mutations in the phenotype of KMT2A-rearranged leukemia was published 20 years ago. The recent development in more sensitive sequencing technologies has contributed to clarify the contribution of these mutations to the evolution of KMT2A-rearranged leukemia and suggested that these mutations might confer clonal fitness and enhance the evolvability of KMT2A-leukemic cells. This is of particular interest since this pathway can be targeted offering potential novel therapeutic strategies to KMT2A-leukemic patients. This review summarizes the recent progress on our understanding of the role of PI3K/RAS pathway mutations in initiation, maintenance, and relapse of KMT2A-rearranged leukemia.

Background

Many cancers are the result of 2 or multiple sequential hits that damage the DNA.1 In the 2-hit model of leukemia, the initial genetic hit often leads to abnormal cell differentiation (Type II mutation) (such as PML-RARα, AML1-ETO, KMT2A rearrangements) while subsequent mutations may activate specific signaling pathways that are involved in cell proliferation, such as FLT3, c-Kit and the RAS/MAP kinase pathway (Type I mutation).2 Chromosomal translocations affecting the Histone-Lysine-N-methyl-transferase 2A gene (KMT2A, previously known as Mixed Lineage Leukemia, MLL) at 11q23 are a genetic hallmark of acute myeloid (AML) and lymphoblastic (ALL) leukemia. This subgroup of leukemia exhibits a particular poor outcome, especially in infant.3,4 To date, 135 KMT2A rearrangements have been described; these chromosomal rearrangements give rise to oncofusion proteins that impair the differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) by epigenetic reprogramming.5–9

HOX genes are the prime targets of KMT2A-fusion products and regulate cellular differentiation in normal hematopoietic development.5 Despite the wide range of potential fusion partners, only 9 account for over 90% of the KMT2A rearrangements and the most frequently diagnosed are KMT2A-AFF1 (MLL-AF4), KMT2A-MLLT3 (MLL-AF9), KMT2A-MLLT10 (MLL-AF10), and KMT2A-MLLT1 (MLL-ENL).8

Analyses of neonatal blood spots, the blood collected by heel prick test, have suggested that KMT2A-AFF1 translocations arise in utero and rapidly lead to the development of overt ALL, often at or shortly after birth.10–12 This argues in favor of the existence of preleukemic clones that do not need cooperating mutations to develop a malignant disease.10,13 In the last 20 years, several groups have investigated the role of cooperating mutations in the development, maintenance, and relapse of KMT2A-rearranged leukemia. The availability of the correct mouse models and the power of sequencing technologies have represented major challenges toward a unified working model.

Several murine mouse models have been developed to study KMT2A-rearranged leukemia in vivo. While the expression of some KMT2A fusion proteins is sufficient for the development of full blown AML in mice,14–21 the development of mouse models of ALL has proved more challenging. For example, KMT2A-MLLT1 is frequently associated with B cell ALL in humans, but it generates AML in mice.22 In 2 studies, KMT2A-AFF1 has shown to induce lymphoma in mice with a latency time of 12 to 14 months for the disease phenotype to become overt.23,24 Whereas the enforced expression of KMT2A-AFF1 in human HSC does not induce leukemia, transduction of human HSCs with a KMT2A-Aff1 construct carrying the human KMT2A fused to the murine Aff1 does induce pro-B ALL within 22 weeks.25 Notably, in humans KMT2A-AFF1 translocations give rise to ALL and are mostly found in infants younger than 1 year old.8,9,12

In addition to the availability of the correct mouse models, another technical challenge is the limitation of sequencing technologies. Both solid and hematological malignancies are made of several subclones, this means that within a cancer there is a bulk of cancer cells sharing a subset of mutations, which are defined as clonal. From each of these clones, at every cell division, new subclones might emerge and they can carry new, additional mutations.26 Thus, although leukemia has a clonal origin, a leukemia is typically a collection of related but genetically distinct populations best considered to be subclones. This has important implications for treatment and clonal evolution of the disease. Recent studies have shown that somatic mutations affecting the kinase/phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/RAS signaling pathway genes, including the PI3K catalytic α polypeptide, (PI3KCA), PI3K regulatory subunit α (PI3KR1), the GTPase activating protein (GAP) NF1 (NF1), the guanosine diphosphate (GDP)/guanosine triphospate (GTP) molecules NRAS and KRAS, the phosphatase SHP2 (PTPN11) and the ubiquitin ligase c-CBL are found in KMT2A-rearranged patients (Fig. (Fig.11).27–43 The PI3K/RAS pathway is activated in response to a variety of extracellular stimuli and transduce signals from the cell surface to the nuclear targets that play a key role in proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation44,45 (Fig. (Fig.1).1). Although the scientific community has accumulated convincing evidences on the role of activated FLT3, which also signals through the Ras pathway, in the development of adult KMT2A-AML2,40,46 and FLT3 has been proven a therapeutic target in both AML and ALL,47,48 the role of PI3K-RAS pathway mutations on KMT2A-driven AML and ALL is controversial. This review summarizes the recent progress on our understanding of the role of mutations in PI3K/RAS pathway in initiation, maintenance, and relapse of KMT2A-rearranged leukemia.

The PI3K/Ras signaling pathway. This illustration of the Ras signaling pathway highlights proteins affected by mutations in KMT2A-rearranged leukemia (pink). Growth factor (GF) binding to cell surface receptors results in activated tyrosine kinase receptor (TRK) complexes, which contain adaptors such as GRB2 (GF receptor bound protein 2) and Gab (GRB2-associated binding) proteins. Upon binding of a GF, such as G-CSF, to a receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), the RTK is autophosphorylated. This creates docking sites for adaptor molecules (eg, GRB2) and for the phosphatase SHP2. These molecules recruit and activate guanosin exchange factors (eg, SOS1) that catalyzes the GDP/GTP exchange on RAS. The GTPase-activating protein neurofibromin (NF1) binds to Ras-GTP and accelerates the conversion of Ras-GTP to Ras-GDP which terminates signaling. RAS-GTP activates several pathways and some are described here. The BRAF–mitogen-activated and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MEK)–extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) cascade primarily determines proliferation via activation of expression of genes important for cell cycle entry. RAF phosphorylates MEK1 and/or MEK2, which in turn activates ERK1 and/or ERK2. Activation of ERKs prompts a cascade of events that culminate in the activation of transcriptional regulators such as MYC, ELK1, FOS, ETS and expression of proteins regulating the cell cycle entry such as cyclin D1. This pathway also regulates the transcriptional activity of CREB/HOX/MEIS complex, which specifically regulates the proliferation and survival of KMT2A-leukemic cells via HOXA9 activity. Ras also activates the PI3K–3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 (PDK1)–Akt pathway that frequently determines cellular survival via inhibition of apoptosis. Active RAS is also able to activate PI3K/Akt pathway by a direct interaction with the PI3K p110 catalytic subunit. This leads to activation of downstream kinases such as PDK1 and AKT. AKT is a Ser/Thr kinase that promotes survival by phosphorylating, and therefore inactivating, several proapoptotic proteins such as BAD and BAX and regulators of cell cycle such as p27 and p21 and also regulates the activity of GSK3. PI3K = phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase.

The detection of cooperating mutations; from the Sanger to Next-Generation Sequencing era

RAS mutations

RAS proteins act as molecular switches by cycling between an active GTP-bound (RAS-GTP) and an inactive GDP-bound (RAS-GDP) conformation that regulate cell fates by coupling receptor activation to downstream effector pathways (Fig. (Fig.1).1). RAS proteins are encoded by 3 genes, KRAS (v-Ki-ras2 Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog), NRAS (neuroblastoma RAS viral [v-ras] oncogene homolog), and HRAS. The N-terminal portion of HRAS, KRAS, and NRAS comprises a highly conserved G domain that has a common structure.45 RAS proteins diverge substantially at the C-terminal end that specifies post-translational protein modifications. In most cases, the somatic missense RAS mutations found in cancer cells affect the aminoacid positions 12, 13, and 61. These changes impair the intrinsic GTPase activity of RAS and confer resistance to GAPs. Thereby mutant RAS proteins accumulate in the active, GTP-bound conformation. Constitutively active mutants of RAS induce oncogenic transformation through activation of the MAPK cascade45 (Fig. (Fig.11).

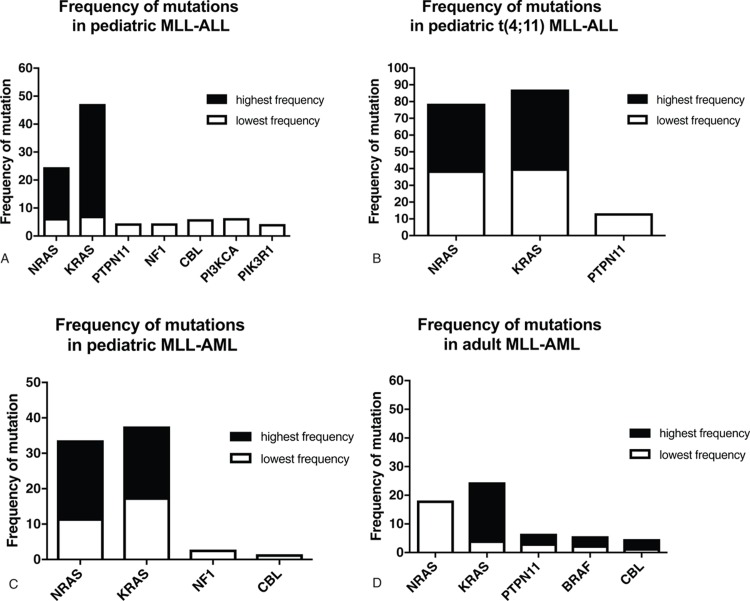

The first study investigating the presence of RAS mutations by Sanger Sequencing in KMT2A-rearranged ALL was published 20 years ago and found no RAS mutations in these patients.27 Subsequently independent groups have reported RAS mutations in up to 80% of KMT2A-rearranged ALL and 50% KMT2A-rearranged AML (Fig. (Fig.22 and Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content).27RAS mutations were most common in infant with KMT2A-AFF1-rearranged ALL28–30 (Fig. (Fig.2).2). Whereas in adult KMT2A-rearranged AML, a statistical significant correlation between mutations and overall survival was not found,34RAS mutations, independently, contribute to a poor outcome in KMT2A-rearranged infant ALL patients.29 In the study by Driessen et al, RAS mutations were not present in the main leukemic clone but in subclones.29 This highlights that the frequency of these mutations might have been underestimated in the previous studies due to the fact that the Sanger Sequencing could not detect mutations with a very low mutant allele frequency. The advent of the Next-Generation Sequencing technologies has enabled the detection of rare subclonal mutations.49,50 Taking advantage of this technology Andersson et al performed a detailed genome and transcriptome wide analysis on diagnostic and matched relapse samples of infant KMT2A-rearranged ALL and found that although the genome of these leukemias are “silent,” with only 1.3 somatic mutations per clone, the most mutated pathway was the RAS/PI3K pathway.31 This has been confirmed by other studies32,33,35,43 (Fig. (Fig.22 and Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content). Interestingly, in the majority of the cases, the mutations were subclonal.31–33,35,43 Clonal but not subclonal mutations showed a correlation with a worse outcome.33 In agreement with previous data,29 a higher frequency of RAS mutations was detected in infants rather than in older patients, corroborating the concept that aberrant RAS expression might shorten leukemia latency.

Frequency of PI3K/RAS pathway mutations in KMT2A-driven leukemia. The figure reports the lowest and the highest frequency of PI3K/RAS pathway mutations in KMT2A-driven leukemia in pediatric MLL-ALL (A), in pediatric MLL-ALL t(4;11) (B), in pediatric MLL-AML (C), and in adult MLL-AML (D). PI3K = phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase.

A further confirmation of the subclonality of these mutations came from the studies of matched diagnostic and relapsed samples. These analyses showed that these mutations might be lost,30,31,33–35,43 maintained/expanded,30–34,36 or gained at relapse.33,42

These studies highlight that RAS mutations are frequent at diagnosis (25–73% frequency) in patients carrying KMT2A rearrangements, in particular in pediatric KMT2A-AFF1 cases, and that these mutations can be either clonal or subclonal secondary genetic events that might take part of a delicate selection process underlying clonal evolution of leukemia. Clonal but not subclonal mutations correlate with a worse outcome in KMT2A-AFF1 ALL.

PTPN11 mutations

PTPN11 encodes for the phosphatase SHP2, a ubiquitously expressed SH2 domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP), required for the full activation of the RAS–RAF–mitogen-activated and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MEK)–extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway (Fig. (Fig.1).1). Constitutively active mutants of SHP2 induce oncogenic transformation through activation of the MAPK and PI3K/AKT cascade.51–54PTPN11 mutations have been initially associated with the development of myeloproliferative disorders (MPD), juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML), and AML.45,51,55–57 More recently, a few studies have shown that single Ptpn11 gain-of-function mutations predispose mice to acute leukemias58,59 suggesting that PTPN11 mutations play a causal role in the development of this disease. More importantly, activating PTPN11 mutations have been described in KMT2A-rearranged ALL31,33 and AML34,36,40 with a frequency of ca.3% for AML and 4% to 13% in ALL (Fig. (Fig.22 and Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content). These are particularly high considering that PTPN11 mutations have been found in 4% to 5% of overall AML patients and 6% of ALL patients.60

The most common mutations are located in the N-SH2 domain and include PTPN11D61Y, PTPN11A72V and PTPN11E76K. These mutants exhibit higher tyrosine phosphatase activity. Mutations in the PTB domain including PTPN11S502T and PTPN11G503A/R/L/E have been reported in a case study and exhibit higher phosphatase activity as well.18 These mutants dephosphorylates yet unknown substrates that negatively affect RAS signaling. Analysis of matched diagnostic and relapsed samples showed that PTPN11G60V were retained in pediatric ALL patient while PTPN11E76Q were gained at relapse.33

Mutations in other PI3K/RAS pathway genes

Few studies have reported mutations in other genes belonging to the PI3K/RAS pathway. BRAF is a member of the RAF kinase family45,61 (Fig. (Fig.1).1). Active RAS culminates in the activation of MAPK pathway via Ser/Thr kinase BRAF. BRAF phosphorylates MEK1 and/or MEK2, which in turn activates ERK1 and/or ERK2. BRAF mutations have been found in KMT2A-rearranged AML and ALL (Fig. (Fig.22 and Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content).29,34,36 Most cancer-associated BRAF mutations encode gain-of-function mutants that constitutively activate the kinase and the MEK–ERK pathway. The mutations seem to disrupt the interaction of the glycine loop and activation segment, which destabilizes the inactive conformation of the protein.

NF1 encodes neurofibromin, which is a GAP that inhibits RAS signaling by hydrolysis of active RAS-GTP into inactive RAS-GDP (Fig. (Fig.1).1). Therefore, NF1 deficiencies act as functional equivalents of activating mutations in RAS.62 Inactivating NF1 mutations lead to the development of a human developmental disorder, the Neurofibromatosis 1, characterized by mental retardation, facial dysmorphism, and increased risk for developing malignant tumors, including JMML and AML.63,64 Few studies have also reported NF1 deletions in KMT2A-rearranged leukemias (Fig. (Fig.22 and Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content).31,37

CBL encodes an E3 ubiquitin ligase that negatively regulates receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) and proteins regulating RAS activity, such as GRB2 and SOS (Fig. (Fig.1).1). Mutations in the linker region and RING finger domain of CBL impair the ability of Grb2 and SOS to suppress RAS signaling, and thereby over-activate RAS.65 CBL mutations have been found at high frequency (15%) in JMML and in 1% to 2% of adult AML.66,67 Recent studies also reported CBL mutations in KMT2A-rearranged patients (Fig. (Fig.22 and Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content).36,39,41

Activating mutations in PIK3CA and PIK3R1 have been reported in KMT2A-rearranged ALL by Andersson et al (Table (Table11).31

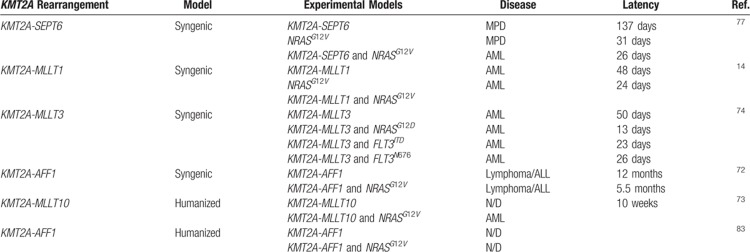

Table 1

Summary of In Vivo Studies Addressing the Role of PI3K/RAS Pathway Mutations in KMT2A-driven Development

Contribution of clonal cooperating mutations to KMT2A-driven leukemogenesis

Experimental mouse models have enabled to understand the role of cooperating mutations in initiation, maintenance, and relapse of leukemia. When modeled using murine systems, gain-of-function mutations in Ptpn11, K-Ras, and N-Ras, or loss-of-function in Nf1 and Cbl are not sufficient to induce leukemogenesis but they induce cytokine hypersensitivity in myeloid progenitors and MPD in mice.51,55,58,59,68–71 Coexpression of these mutations with KMT2A-rearrangement has provided substantial evidence to the hypothesis that some cooperating mutations may synergistically cooperate with KMT2A rearrangements in leukemogenesis.14,72–74

Syngenic mouse models of KMT2A-leukemia

The in vivo leukemogenesis assay is based on injection of mouse HSC that have been retrovirally transduced with a KMT2A-fusion gene, in syngenic mice lethally or sublethally irradiated. Serial transplantation of primary leukemia in secondary recipients allows to evaluate the impact of additional genetic and epigenetic events in the disease onset.75 However, these models are far from being perfect. The phenotype and pathogenesis of the leukemia developed in these murine models sometimes do not match those observed in human leukemia associated with the same genetic lesion, in part because of the biological differences between human and mouse HSCs.76

A controversial study by Ono et al concluded that NRASG12V cooperated with KMT2A-SEPT6. The mice receiving the HSC expressing KMT2A-SEPT6 and NRASG12V died of AML with a significantly shorter latency of those receiving KMT2A-SEPT6, which instead died of MPD (26 ±

± 2.4 days vs 137

2.4 days vs 137 ±

± 9.0 days). However, in this setting, mice receiving NRASG12V alone died with a similar latency than those receiving KMT2A-SEPT6 and NRASG12V (31

9.0 days). However, in this setting, mice receiving NRASG12V alone died with a similar latency than those receiving KMT2A-SEPT6 and NRASG12V (31 ±

± 1.4 days vs 26

1.4 days vs 26 ±

± 2.4 days), although they developed MPD rather than AML (Table (Table11).77

2.4 days), although they developed MPD rather than AML (Table (Table11).77

Zuber et al investigated the cooperation between KMT2A-rearrangement (KMT2A-MLLT1) and RAS mutation (NRASG12V). They found that NRASG12V accelerated the disease onset in mice injected with HSC transduced with KMT2A-MLLT1 (24 days vs 48 days) (Table (Table11).14 Hyrenius-Wittsten et al studied the effect of NRASG12D, FLT3ITD, and FLT3N676K on KMT2A-MLLT3 leukemia development.74FLT3 is a tyrosine kinase receptor overexpressed in KMT2A-rearranged leukemia and it is also commonly mutated in AML.2,5,40 Despite the fact that the percentage of cells coexpressing KMT2A-MLLT3 and one of the cooperating mutations was very low (1–3%), the mice receiving cotransduced cells succumbed of leukemia much earlier than those receiving cells only transduced with KMT2A-MLLT3 (median latency of 13, 23, 26 days, respectively, vs 50 days for KMT2A-MLLT3 alone) (Table (Table1).1). These data indicate that these mutations, when occurring in the founder clone, can accelerate the onset of AML driven by KMT2A-MLLT3.74 The authors then performed a serial transplantation, by transplanting primary murine KMT2A-rearranged AML in secondary recipients. Interestingly, the disease latency of the secondary KMT2A-MLLT3 mice was very similar to those of the secondary mice that coexpressed an activating mutation indicating that secondary KMT2A-MLLT3 mice had accumulated additional genetic and epigenetic events that accelerated the disease onset. Further analysis of the bone marrow of these mice indicated a consistent activation of Akt, p38, and ERK pathways. These data therefore indicate that after serial transplantation the leukemic cells expressing KMT2A-MLLT3 adapted in vivo to acquire a phenotype similar to those that coexpressed activating mutations. This suggest that these mutations might confer clonal fitness.74 Tamai et al developed a transgenic mouse carrying KMT2A-AFF1 and KRASG12V that developed B-cell lymphoma/ALL in 6 months.72 Previous mouse models failed to recapitulate the human leukemia induced by KMT2A-AFF1.20,23,24 In the study of Tamai et al, mice developed lymphoma/ALL significantly earlier than the transgenic mice carrying KMT2A-AFF1 alone (median survival 5.5 months vs 12 months), suggesting that KRAS mutations contributes to the early onset of ALL driven by KMT2A-AFF1 (Table (Table11).72

Limited studies have addressed the contribution of Ptpn11 to KMT2A-driven leukemia in vivo. As shown for RAS, coexpression of Ptpn11S506W and Ptpn11E67k accelerated KMT2A-MLLT3 leukemia development in syngenic mouse models.74,78 In vitro studies have demonstrated that SH2 and PTB domains PTPN11 mutants such as PTPN11E76K, PTPN11A72V, PTPN11D61Y, and PTPN11G503A lose the autoinhibitory feedback, increased phosphatase activity, and induced hypersensitivity to IL-3 and GM-CSF. This can provide a growth advantage to the leukemic clones.18,51,55,70,79,80

Overall, these studies suggest that distinct KMT2A rearrangements have different dependence on RAS signaling or that a certain threshold of RAS signaling may be necessary to establish a leukemic disease in the murine models.

Humanized mouse models of KMT2A-leukemia

Humanized mouse models have also attempted to clarify the role of cooperating mutations in KMT2A-rearranged leukemia. In these models, human cord blood-derived HSC are retro- or lentivirally transduced with a KMT2A-fusion gene and then transplanted into immunodeficient mice, such as NOD/SCID, that lack mature B and T cells, or NSG mice that lack mature NK, B, and T cells.81 Barabe et al showed that KMT2A-MLLT1 and KMT2A-MLLT3 induce AML in NOD/SCID mice in which the NK cells were depleted by an anti-NK cell antibody.21 Likewise Wei et al showed that KMT2A-MLLT3 induces AML in NOD/SCID mice that express transgenic human SCF, GM-CSF, and IL-3 genes suggesting that human cytokines may provide the KMT2A-MLLT3-transdused HSCs with additional signals for cell growth and survival, acting as oncogenic promoters.16 Interestingly, although KMT2A-MLLT10 does not induce leukemia on its own, mice transplanted with HSC expressing KMT2A-MLLT10 and KRASG12V developed AML and died within 10 weeks from transplantation (Table (Table11).73 In this contest, expression of KRASG12V can mimic the signaling stimulated by the cytokines reported in the study by Wei et al since stimulation with SCF and IL-3 directly activates the RAS signaling pathway in leukemogenesis.73 By contrast, the enforced expression of KMT2A-AFF1 in human HSCs does not induce leukemia,82 even in cooperation with KRASG12V83. This is in contrast with the results obtained in the syngenic model.72 Whereas the inability to generate a faithful model of KMT2A-AFF1 ALL supported the hypotheses that this oncogene could be unable to transform cells without cooperating oncogenes, the failure of models exploring the role of cooperating mutations83–85 have fuelled other hypotheses such as that KMT2A fusions might have a different dependence on RAS signaling,73 distinct KMT2A fusions might target different progenitor cells82,86,87 or strictly depend on the bone marrow microenvironment.25,76 These hypotheses are brilliantly reviewed by Sanjuan-Pla et al.13 Notably, the gene expression profile of KMT2A-AFF1-KRASG12V human HSC indicates an up-regulation of genes important in cell motility and cell migration and a down-regulation of genes important for cell adhesion, aggregation, and mesenchymal-epithelial transition.30,88 These data are in agreement with the Gene Ontology signature of KMT2A-AFF1 patients. This would also explain the clinical hallmarks of KMT2A-AFF1 patients who suffer from extramedullary hematopoiesis and central nervous system infiltration.

This suggests that clonal RAS mutations might be important in maintenance and chemotherapy resistance rather than initiation of KMT2A-AFF1-driven leukemia.

The impact of subclonal mutation on KMT2A-driven leukemogenesis

All the in vivo studies reviewed in the previous paragraphs were based on human or mouse HSC cotransduced with retro- or lentivirus vectors expressing the KMT2A-rearrangement and the cooperating mutation of interest. These models enabled the authors only to address the effect of clonal mutations in the development of KMT2A-rearranged leukemia. Very limited information is available on the impact of subclonal mutations on KMT2A-driven leukemogenesis. A recent study from Hyrenius-Wittsten et al elegantly addresses how subclonal mutations affecting FLT3N676K contribute to the development of KMT2A-MLLT3 leukemia. The authors injected cells expressing KMT2A-MLLT3 and the activating mutation FLT3N676K and cells expressing only KMT2A-MLLT3 at various ratios (from 1:28 to 1:156). Despite the low number of cells coexpressing KMT2A-MLLT3 and FLT3N676K, mice receiving cotransduced cells succumbed of leukemia much earlier than those receiving cells only transduced with KMT2A-MLLT3 (median latency 34 days vs 50 days for KMT2A-MLLT3 alone), confirming that subclonal activating mutations in FLT3 accelerate KMT2A-MLLT3 leukemogenesis Hyrenius-Wittsten.74 Disease latency in secondary recipients was just slightly different (median latency 16 days vs 21 days for KMT2A-MLLT3 alone). As the FLT3N676K construct was fused with GFP, the authors could analyze the clone size by fluorescence. The data indicate that in most of the mice the clone increased in size; however, there were also cases where the clone was maintained or lost. This, together with the shorter latency of mice receiving KMT2A-MLLT3 and FLT3N676K, suggests that the clone might have acquired de novo mutations to adapt in vivo. Sequencing revealed that the secondary recipients show de novo mutations in PI3K/RAS pathway genes such as Ptpn11, Cbl, Braf, and Kras. This suggests that the subclones KMT2A-MLLT3+FLT3N676K might influence the environment and increase the chances for other clones to acquire specific mutations. The authors investigated the expression of cytokines and growth factors and found that several genes were differentially regulated in the leukemic cells. One commonly upregulated in cells expressing KMT2A-MLLT3 and a cooperating mutation (either NRASG12D, FLT3ITD, or FLT3N676K) but not in cells expressing KMT2A-MLLT3 alone and normal healthy hematopoietic subpopulations, was the macrophage Migration Inhibitory factor (Mif).74 These data agree with previous data reporting a marked increase in inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, CCL12, CCL4, in the plasma of transgenic mice Ptpn11E76K/+Mx1-Cre+ mice, where the Ptpn11E76K mutation is expressed in HSC and bone marrow microenvironment.58 Thus, it appears that persistent high levels of proinflammatory cytokines hyperactivate the bone marrow microenvironment and displace HSC from their niches, contributing to the development of MPD that might lead to AML.58 The results of Hyrenius-Wittsten et al highlight the importance of FLT3N676K in the initiation and in the progression of KMT2A-MLLT3 leukemia and suggest that cooperating mutations might facilitate an inflammatory environment that could play an important role on the selection process underlying clonal evolution of leukemia.

Are mutations in PI3K/RAS pathway second hits for early KMT2A-leukemia onset?

The studies reviewed so far highlight that mutations in the PI3K/RAS pathway are frequent at diagnosis in patients carrying KMT2A rearrangements.

It is difficult to establish the role of these mutations in pediatric versus adult KMT2A-driven ALL because only one of the studies reviewed here reports the mutation frequency in KMT2A-rearranged adult ALL. In this study, by Prelle et al, the frequency of RAS mutations is higher in pediatric than adult patients (26% vs 8%).30 Nevertheless, the authors neglect that these additional mutations might be the second hits for early onset of KMT2A-AFF1 ALL. The authors disagree with this speculation because the frequency of the mutations is not sufficient to fully sustain the 2-hit model. If we sum the frequency of all the mutations reported in the PI3K-RAS pathway in each study, we can clearly observe that in pediatric KMT2A-AFF1 cases the mutation frequency reaches 80% to 90%, at least in the most recent publications where more sensitive sequencing technologies have been applied.32,33 This can lead us to speculate that mutations in the RAS/PI3K pathway could be the second hits for early leukemia onset at least for some patients, as those carrying the translocations KMT2A-AFF1. However, the subclonality of these mutations, the fact that they are often lost at relapse and the lack of a robust in vivo model do not fully fit with this hypothesis.

Additional studies are required to determine whether in the cases with KMT2A-rearrangements without PI3K/RAS mutations or in the cases where the mutations are subclonal there are alternative modes of RAS pathway activation. For example, in chronic myeloid leukemia, where RAS mutations generally are absent, the RAS signaling pathway is deregulated by the BCR-ABL fusion protein.89 In view of this, it is interesting that both KMT2A-AFF1 and KMT2A-MLLT3 have been shown to directly activate RAS pathway through activation of ELK-1 protein, a downstream target of the RAS/RAF signaling pathway.90,91 In addition, KMT2A-AF6 has been shown to aberrantly activate RAS and its downstream signaling.92 Thus, these fusion proteins are per se able to activate the RAS/RAF signaling cascade by themselves and, therefore, RAS clonal mutations might actually not be necessary. Unfortunately appropriate in vitro and in vivo models are not yet available to fully elucidate the role of RAS activation in KMT2A-leukemogenesis. It is, however, notable that RAS mutations are a predictor of poor outcome in KMT2A-rearranged pediatric ALL and therefore this information can help to stratify patients.29

Mutations in NRAS and KRAS are more frequent at diagnosis in KMT2A-rearranged AML than KMT2A-rearranged ALL (Fig. (Fig.2).2). In the majority of the AML cases, the subclones with RAS pathway mutations detected at diagnosis are not detectable at relapse. An exception to this pattern is mutations in KRAS that were instead found expanded in relapse samples.34,36 However, in contrast to infant RAS-mutant KMT2A-rearranged ALL, the presence of these mutations does not impact the outcome of the patients. Again, in contrast to infant RAS-mutant KMT2A-rearranged ALL where the contribution of RAS activation is still under debate, several studies have proven that RAS activation and activation of RAS downstream targets, MAPK and PI3K signaling, confers a proliferative advantage to AML leukemic cells and is almost ubiquitous in AML.77,93 In addition to the known somatic activating mutations in RAS and RAS activating genes NF1 and PTPN11, that we have reviewed here, constitutive activation of several RTKs, such as colony stimulating factor 1 and FLT3, which also partially signals through the RAS pathway, contribute to the pathogenesis of AML.5,46 Together, these observations indicate that RAS mutations and/or activation provide a growth advantage to KMT2A-AML cells and have therefore fuelled intense interest in the development of RAS-targeted AML therapy as described below.

Targeting the RAS pathway in KMT2A-driven leukemia

The high incidence of RAS pathway mutations at diagnosis, their abundance in the major clone of relapsed leukemic cells and association with high-risk disease, provide a rationale to investigate potential novel therapies that exploit pathway activation, such as kinase inhibitors that act downstream of RAS targeting the RAF/MAPK or PI3K/AKT pathway or farnesyltransferase inhibitors preventing the post-translational modification of RAS, in KMT2A patients.94,95 MEK1/2 inhibitors are the most promising as ERK1/2 are the only downstream targets of MEK1/2, whereas ERK can phosphorylate over 150 targets.96 MEK1/2 inhibitors, such as Selumetinib, Pimasertib, and Trametinib, are in clinical trials and have moderate efficacy as single agents in AML and ALL, particularly in leukemias harboring RAS pathway mutations.42,97–101 A few studies have addressed their efficacy in KMT2A-rearranged AML and ALL.

Kerstjens et al investigated the effect of MEK inhibitors in infant KMT2A-ALL carrying RAS mutations and found that RAS mutant KMT2A-ALL cell lines and primary samples are sensitive to Trametinib, MEK162, and Selumetinib, whereas non-RAS mutant KMT2A-ALL cell lines and primary samples were insensitive to MEK1 inhibitors.102 Interestingly, MEK inhibitors increased apoptosis and enhanced the sensitivity of KMT2A-ALL cells to prednisolone, regardless of the RAS mutational status, in agreement with previously published data.100 However, when tested in vivo, MEK inhibitor Trametinib did not inhibit leukemia progression in a KMT2A-rearranged ALL in vivo model.103 Trentin et al tested PD0325901, a potent inhibitor of MEK1/2 currently in phase II clinical trials, on NRASQ61K mutated KMT2A-AFF1 B cell line MI04. The inhibitor reduced the proliferation of MI04 of 40% even at nanomolar concentrations, whereas the 2 RAS wild-type KMT2A-AFF1 cell lines showed only a modest proliferative reduction even increasing the drug concentration.32 Importantly, in 1 RAS wild-type non-KMT2A-rearranged ALL patient Trametinib had an antagonistic effect on prednisolone sensitivity.100 This is in contrast with the data published by Jones et al that reported an agonistic effect between Trametinib and prednisolone in 2 non-KMT2A rearranged ALL patients who did not carry RAS mutations.97 Notably the study by Jones et al reported the agonistic effect in 3 out of 5 patients, and only one of them carried RAS mutations. These findings warn against a broad use of MEK inhibitors and suggest that the implementation of these inhibitors needs to be guided by relevant biomarkers (eg, RAS mutation) and preclinical in vitro evidence.

Although in AML no major differences between the transcriptomes of KMT2A-rearranged RAS wild-type and KMT2A-rearranged RAS-mutant cells have been found, kinome, proteome profiling, and chemical analyses revealed that the responses of these cells to MEK inhibitors were distinct, suggesting that MEK inhibitors could be effective.36,104

MEK inhibitor U0126 effectively reduced the cell survival of primary KMT2A-rearranged AML samples in contrast to normal bone marrow cells.104 Among the samples tested by Kampen et al, the ones carrying RAS mutations showed greater sensitivity to MEK inhibitors. Kampen et al also tested a range of AML cell lines carrying NRAS mutations and/or KMT2A rearrangement. The authors found that THP1 (NRAS mutated—KMT2A rearranged) showed greater sensitivity to MEK inhibitors than HL60 and OCI-AML3 (NRAS mutated—non-KMT2A rearranged) and RAS wild-type non-KMT2A-rearranged AML cell lines. By contrast, neither knockdown nor knockout of MEK1 affected the proliferation of THP1.105 These results might suggest that simultaneous targeting of MEK1 and MEK2 might be fundamental to achieve a therapeutic effect.

Despite the encouraging preclinical data obtained with MEK inhibitors on KMT2A-rearranged AML and ALL, a monotherapy is unlikely to be successful. In vivo data and phase II clinical trials showed that MEK inhibition only resulted in nonsustained responses, suggesting aberrant feedback mechanisms.98 Kampen et al showed in response to MEK inhibitors a sustained activation of AKT/mTOR and VEGFR-2 pathways that enabled a subpopulation of KMT2A-rearranged AML cells to survive MEK inhibition, suggesting the need to target multiple pathways.104 In agreement, Lavallée et al showed increased efficacy in KMT2A-rearranged RAS mutant AML samples when MEK inhibitors were used in combinations with VEGFR-2 inhibitors.36 Notably both KMT2A-AFF1 and KMT2A-MLLT3 have been shown to directly activate RAS pathway.90,91 This suggests that KMT2A patients might benefit from inhibitor of this pathway even if they do not carry RAS mutations. This hypothesis needs to be experimentally validated.

The identification of PTPN11 mutations in KMT2A-rearranged leukemia and the requirement for SHP2 function in the RAS signaling pathway strongly suggest that small molecule SHP2 inhibitors might have important therapeutic applications. Indeed, SHP2 plays a key role in controlling apoptosis and the suppression of SHP2 expression induces differentiation, apoptosis and inhibits leukemic cell clonogenic growth.79,80,106 Unfortunately, the development of bioavailable SHP2 inhibitors has proven to be difficult. The discovery of SHP2-specific inhibitors is complicated by the extremely high homology of the catalytic core of SHP2 with those of SHP1 and other PTPs that play negative roles in growth factor and cytokine signaling. Yu et al characterized the inhibitor No. 220 to 324 in cell line and JMML primary samples and found that the drug effectively inhibited SHP2 activity and IL-3-induced ERK, AKT, and STAT5 activation in a dose-dependent manner.107

Other agents such as MEK and mTOR inhibitors might prove efficacious in RAS-mutated leukemias. Liu et al demonstrated the preclinical therapeutic efficacy of mTOR inhibitor Rapamycin in the mouse model of Ptpn11 mutation-induced MPN and also in PTPN11 mutation-positive JMML patient cells.108 Likewise Parkin et al showed that AML blasts that do not express NF1 display differential sensitivity to in vitro treatment with Rapamycin.64

Conclusions and perspectives

The high frequency of activating mutations in tyrosine kinase/PI3K/RAS pathway genes in KMT2A-rearranged leukemia underscores the biologic cooperativity between KMT2A fusion proteins and signaling through this pathway. Experimental models have proved that some KMT2A rearrangements synergistically cooperate with RAS mutations in leukemogenesis, suggesting that these mutations could be important in the initiation of the disease. The controversial data on the crosstalk between RAS mutations and KMT2A-AFF1 suggest that RAS mutations are not important for initiation of leukemia. Analyses of several diagnostic and relapse matched samples will be essential to address the contribution of these mutations to maintenance and relapse of KMT2A-rearranged leukemia. The mutational burden could also inform therapeutic decisions and indicate which patients could benefit from a targeted therapy. One can argue that targeting minor clones rather than the dominant one is a questionable approach; however, the experimental data indicate that RAS and PTPN11 clonal mutations are associated with chemotherapy resistance and that MEK inhibitors enhance the sensitivity to prednisolone of both RAS wild-type and mutant ALL.33,97,100,102,109 Therefore, given that effective targeted therapies are currently not available for KMT2A-rearranged leukemia patients, these findings have important therapeutic implications.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank Prof. Fulvio D’Acquisto for critical reading of the manuscript and mentorship.

Footnotes

Citation: Esposito MT. The Impact of PI3-kinase/RAS Pathway Cooperating Mutations in the Evolution of KMT2A-rearranged Leukemia. HemaSphere, 2019;00:00. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/HS9.0000000000000195.

Funding: This work has been supported by the University of Roehampton and Leuka.

Disclosure: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Authors’ contributions: MTE planned the review, wrote and reviewed the manuscript.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article.

References

Articles from HemaSphere are provided here courtesy of Wiley

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

Mutation of key signaling regulators of cerebrovascular development in vein of Galen malformations.

Nat Commun, 14(1):7452, 17 Nov 2023

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 37978175 | PMCID: PMC10656524

SET-PP2A complex as a new therapeutic target in KMT2A (MLL) rearranged AML.

Oncogene, 42(50):3670-3683, 27 Oct 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37891368 | PMCID: PMC10709139

Nuclear FGFR2 Interacts with the MLL-AF4 Oncogenic Chimera and Positively Regulates HOXA9 Gene Expression in t(4;11) Leukemia Cells.

Int J Mol Sci, 22(9):4623, 28 Apr 2021

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 33924850 | PMCID: PMC8124917

Acute Myeloid Leukemia in Children: Emerging Paradigms in Genetics and New Approaches to Therapy.

Curr Oncol Rep, 23(2):16, 13 Jan 2021

Cited by: 32 articles | PMID: 33439382 | PMCID: PMC7806552

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

De novo activating mutations drive clonal evolution and enhance clonal fitness in KMT2A-rearranged leukemia.

Nat Commun, 9(1):1770, 02 May 2018

Cited by: 29 articles | PMID: 29720585 | PMCID: PMC5932012

Duplex Sequencing Uncovers Recurrent Low-frequency Cancer-associated Mutations in Infant and Childhood KMT2A-rearranged Acute Leukemia.

Hemasphere, 6(10):e785, 30 Sep 2022

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 36204688 | PMCID: PMC9529062

CRISPR-Cas9 Library Screening Identifies Novel Molecular Vulnerabilities in KMT2A-Rearranged Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia.

Int J Mol Sci, 24(17):13207, 25 Aug 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 37686014 | PMCID: PMC10487613

Updates in the biology and therapy for infant acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Curr Opin Pediatr, 29(1):20-26, 01 Feb 2017

Cited by: 9 articles | PMID: 27841777

Review