Abstract

Free full text

μ-Opioid Receptors Modulate NMDA Receptor-Mediated Responses in Nucleus Accumbens Neurons

Abstract

The nucleus accumbens (NAcc) may play a major role in opiate dependence, and central NMDA receptors are reported to influence opiate tolerance and dependence. Therefore, we investigated the effects of the selective μ-opioid receptor agonist [d-Ala2-N-Me-Phe4,Gly-ol5]-enkephalin (DAMGO) on membrane properties of rat NAcc neurons and on events mediated by NMDA and non-NMDA glutamate receptors, using intracellular recording in a brain slice preparation. Most NAcc neurons showed a marked inward rectification (correlated with Cs+- and Ba2+-sensitive inward relaxations) when hyperpolarized, as well as a slowly depolarizing ramp with positive current pulses. Superfusion of DAMGO did not alter membrane potential, input resistance, or the inward relaxations. In the presence of 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX) used to block non-NMDA glutamate receptors and bicuculline to block GABAAreceptors, EPSPs evoked by local stimulation displayed characteristics of an NMDA component: (1) long duration, (2) voltage sensitivity, and (3) blockade by the NMDA receptor antagonistdl-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (d-APV). DAMGO (0.1–1 μm) significantly decreased both NMDA- and non-NMDA–EPSP amplitudes with reversal of this effect by naloxone and the μ-selective antagonist [Cys2-Tyr3-Orn5-Pen7]-somatostatinamide (CTOP). To assess a postsynaptic action of DAMGO, we superfused slices with tetrodotoxin and evoked inward currents by local application of glutamate agonists. Surprisingly, 0.1–1 μm DAMGO markedly enhanced the NMDA currents (with reversal by CTOP) but reduced the non-NMDA currents. At higher concentrations (5 μm), DAMGO reduced NMDA currents, but this effect was enhanced, not blocked, by CTOP. These results indicate a complex DAMGO modulation of the NMDA component of glutamatergic synaptic transmission in NAcc: μ receptor activation decreases NMDA–EPSP amplitudes presynaptically yet increases NMDA currents postsynaptically. These new data may provide a cellular mechanism for the previously reported role of NMDA receptors in opiate tolerance and dependence.

The nucleus accumbens (NAcc) is considered a ventral part of the striatum (Heimer and Wilson, 1975). Immunocytochemical studies have revealed organizational complexity of the NAcc as a heterogeneous structure that can be divided into shell and core regions. The NAcc contains mostly (90%) GABAergic medium spiny neurons with some cholinergic interneurons (Wilson, 1990;Groenewegen et al., 1991). These neurons receive dopaminergic inputs primarily from the ventral tegmental area and substantia nigra and glutamatergic afferents from the prefrontal cortex, subiculum, and thalamus (Pennartz et al., 1994). Besides its proposed role as an interface in the limbic motor system (e.g., in locomotor activity and goal-directed behavior), the NAcc has drawn considerable attention for its role in reinforcing effects of abused drugs, including opiates (Koob et al., 1992). Significantly, this region contains several classes of opioid peptides and opiate receptor subtypes, including the μ-opioid receptor (Mansour et al., 1994, 1995; Zastawny et al., 1994), for which the pattern of expression is complex (Herkenham and Pert, 1981; Herkenham et al., 1984; Jongen-Relo et al., 1993).

Recent findings suggest that glutamatergic transmission may interact with these opioid systems. For example, it has been proposed that glutamatergic transmission plays a role in opiate tolerance and dependence. Thus, the noncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801 antagonizes some aspects of naloxone-precipitated tolerance and withdrawal syndromes (Marek et al., 1991; Trujillo and Akil, 1991,1994). Electrophysiological studies have revealed that excitatory transmission in the NAcc is composed primarily of glutamatergic EPSPs (Wilson, 1990). However, few studies have addressed the question of physiological interactions between opiate and glutamatergic transmission in this structure (Yuan et al., 1992), and none has determined the effect of opiates on NMDA-mediated transmission in NAcc. Therefore, we have examined possible interactions between the μ-opioid receptor agonist [d-Ala2-N-Me-Phe4,Gly-ol5]-enkephalin (DAMGO) and NMDA-mediated responses in a slice preparation of the NAcc to help clarify the role of glutamatergic NMDA transmission in opiate addiction at the cellular level. Our findings suggest that μ receptor activation does regulate NMDA receptor-mediated processes, but in a surprisingly complex manner: by reducing glutamate release presynaptically while augmenting responses of NMDA receptors postsynaptically.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and slice preparation. We used male Sprague Dawley rats (100–170 gm) to prepare nucleus accumbens slices from fresh brain tissue, as described previously (Yuan et al., 1992; Nie et al., 1993). We rapidly removed the brain and transferred it to a cold (4°C) and oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) of the following composition (in mm): NaCl 130, KCl 3.5, NaH2PO4 1.25, MgSO4·7H2O 1.5, CaCl2 2, NaHCO3 24, and glucose 10. We glued a tissue block containing NAcc to a Teflon chuck, cut it transversely with a Vibroslice cutter (Campden Instrument), and immediately incubated the slices (400 μm thick) in the recording chamber. During initial incubation in an interface configuration, the tops of the slices were exposed to a mixture of 95% O2/5% CO2. After 30 min we submerged and superfused the slices with warm (34°C) carbogenated ACSF at a rate of 3–4 ml/min.

Recording. We pulled sharp glass microelectrodes from borosilicate capillary glass (1.2 mm outer diameter, 0.8 mm inner diameter) on a Brown–Flaming puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) and filled them with 3 m KCl. Tip resistances were 60–100 MΩ. We used an Axoclamp 2B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) to record neurons in current- and voltage-clamp modes. Throughout all experiments we continuously monitored electrode resistance in current-clamp mode, and electrode settling time and capacitance neutralization (on a separate oscilloscope) in discontinuous single-electrode voltage-clamp studies. Current and voltage levels were monitored and stored on a polygraph, digitized by a TL-1 interface (Axon Instruments), and stored on a 486 personal computer with Clampex 6.0 software (Axon Instruments). Then the digitized records were analyzed with Clampfit software (Axon Instruments). We recorded neurons within the core NAcc just ventrally to the anterior commissure [Yuan et al. (1992), their Fig. Fig.1].1]. We constructed current–voltage curves in both current- and voltage-clamp modes. For most of the cells we used standard current-clamp (bridge) methods with a 250 msec step duration and measured the voltage before the step and at a steady-state 240 msec after the onset of the current pulse. In a smaller group of neurons we used voltage clamp with step durations of 700 msec and measured the step current at a steady-state 600 msec after the onset of the voltage pulse.

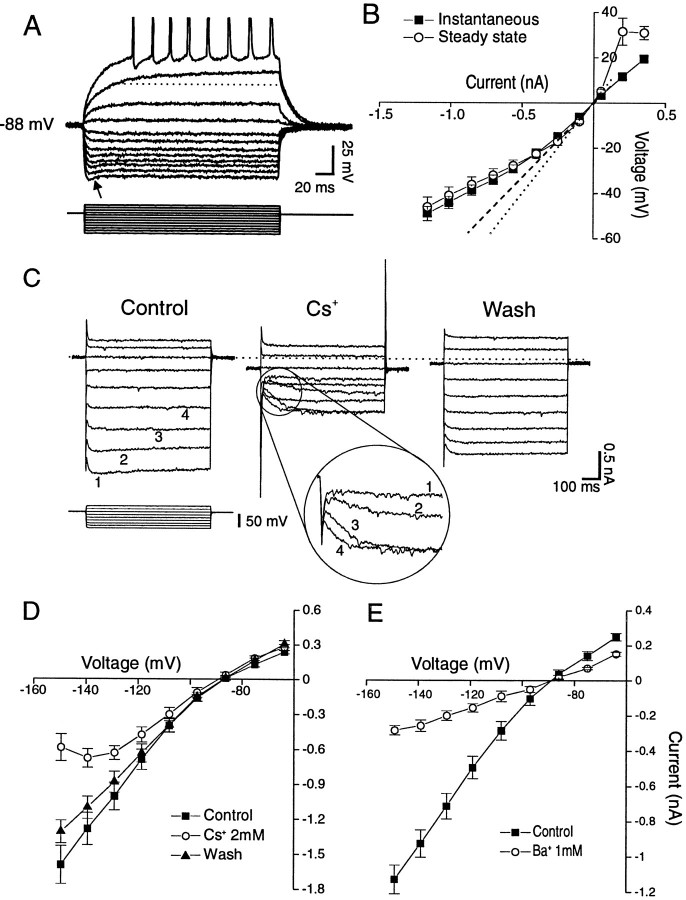

Typical membrane properties of NAcc neurons, evaluated by recording responses to hyper- and depolarizing steps.Top panels, Current clamp; the most negative potential was obtained with a step of 1150 pA, with decrements of current pulses of 150 pA; the pulse duration was 210 msec. A, A cell with rectification, a sag (arrow), and a slowly depolarizing ramp, highlighted by the dotted line.B, V–I relations of a group of cells displaying instantaneous (filled squares) and steady-state potentials (open circles). Thedotted and dashed lines represent the theoretical ohmic behavior of cells. C, Voltage-clamp records of inward relaxations produced by hyperpolarizing steps applied to a NAcc neuron. Cs+ (2 mm) dramatically decreased overall conductance (middle panels); moreover, it blocked the inward relaxation at large hyperpolarizing steps (inset numbers refer to the same steps as in theleft panel) but had little effect at the smaller steps (although it did seem to slow the kinetics of the inward relaxation), with nearly complete recovery (right panel) on washout [holding potential (VH) = RMP = −85 mV]. Cs+also caused an inward holding current (−230 pA), followed by a partial recovery on washout (−120 pA). Bottom panels, Mean (± SEM) I–V curves from voltage-clamp recordings.D, Effects of 2 mm Cs+, which had a voltage-sensitive influence: it reduced overall conductance primarily in the hyperpolarized domain, resulting in a region of negative slope conductance. E, Effects of 1 mm Ba2+. Note that this concentration of Ba2+ gave rise to a nonvoltage-sensitive reduction in conductance, resulting in a linear I–V curve.

Synaptic stimulation. For the majority of the cells, we studied the NMDA component of EPSPs in bridge mode, using aV–I protocol (400 msec step duration) to measure EPSP amplitudes evoked at different membrane potentials. Monosynaptic NMDA–EPSPs were elicited by local (“focal” or “proximal”) stimulation triggered 100 msec after the onset of, and therefore superimposed on, the current pulse. We averaged two traces at the same current step size with their superimposed NMDA–EPSPs. We also measured membrane potential for each current step before the evoked EPSP. Because the current-evoked potential reached was different from cell to cell (attributable to the variability of membrane input resistance), we measured each NMDA–EPSP amplitude relative to the membrane potential from which the EPSP was evoked. Such measures allowed pooling across cells of NMDA–EPSP amplitudes evoked within the same potential range, thus minimizing the influence of membrane input resistance.

Synaptic components were elicited with a tungsten bipolar stimulating electrode with a tip separation of 1 mm. In contrast to the peritubercle stimulation used previously in our laboratory (Nie et al., 1993), we placed the stimulating electrode within the NAcc close to (within 1 mm of) the recording electrode. Stimulation parameters (3–14 V, 50 μsec pulse duration, delivered at 0.1 Hz) were chosen to generate a sizable and reproducible monosynaptic NMDA–EPSP (without spiking) for each cell, and the stimulus intensity then was maintained constant throughout the recording period.

Drug administration. To isolate the NMDA–EPSP component pharmacologically, we superfused the slices with antagonists specific for (R,S)-α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid (AMPA)/kainate (non-NMDA) receptors [10 μm6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX)] and GABAAreceptors (15 μm bicuculline), for at least 1 hr before recording. For further verification of the involvement of NMDA receptors in the EPSPs, we superfused the NMDA receptor antagonistdl-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (d-APV; 60 μm) at the end of some experiments. To isolate AMPA/kainate receptors, we superfused 60 μmd-APV and 15 μm bicuculline for 1 hr before data acquisition. In other studies, to test for postsynaptic DAMGO effects, we applied NMDA, AMPA, or kainate locally by pressure (5–15 psi; 200 μm NMDA, 15 μm AMPA, or 15 μm kainate; 2 sec duration) from a broken-tipped pipette (tip diameter ~2 μm) or, in a few cells, by rapid superfusion of 30 μm NMDA. In these studies, we superfused 1 μm tetrodotoxin (TTX) to minimize presynaptic DAMGO, AMPA, kainate, or NMDA effects, in addition to the 10 μmCNQX (or 30 μmd-APV for AMPA/kainate tests) and 15 μm bicuculline.

Our standard drug-testing protocol was as follows: after recording a stable membrane potential and glutamate receptor-evoked events for at least 15 min, we superfused the slices with the ACSF–antagonist solution described above but containing the selective μ-opioid receptor agonist DAMGO (0.01–5 μm; 15–25 min). This was followed by washout with the control ACSF solution. Opiate antagonists were superfused either before or after DAMGO application. The superfusion system allowed switching of drug–ACSF solutions without disrupting the rapid flow of the ACSF through the recording chamber (Moore et al., 1988a). We purchased TTX from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA); CNQX from RBI (Natick, MA); [Cys2-Tyr3-Orn5-Pen7]-somatostatinamide (CTOP) from Peninsula (Belmont, CA); and naloxone, bicuculline,d-APV, AMPA, kainate, and NMDA from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Statistics. We expressed all averaged values as mean ± SEM. We tested for statistically significant differences among control, treatment, washout, and opiate antagonist conditions by one-factor ANOVA for repeated measures, with a post hoc analysis by Newman–Keuls or Fisher Probability of Least Significant Difference comparison tests. We considered p < 0.05 statistically significant.

RESULTS

Features of NAcc core neurons

Membrane properties

We recorded from 103 cells in NAcc slices taken from 75 rats. All stable (therefore relatively uninjured) cells had resting membrane potentials (RMPs) more negative than −80 mV and spike amplitudes >100 mV. None of these cells displayed spontaneous action potentials, although some displayed spontaneous synaptic activity of uncharacterized origin. Membrane properties were analyzed more precisely from voltage–current relationships in a subset (n = 51) of this sample: the mean RMP of this subset was −85.3 ± 0.5 mV; average membrane resistance was 78.6 ± 5.1 MΩ, and average spike amplitude was 119 ± 1.9 mV. There was some evidence of heterogeneity in cell type or state in this NAcc population. For example, 39 of 51 cells displayed a slowly developing ramp in response to depolarizing steps subthreshold for spiking (Fig.(Fig.11A; see dashed line). In addition, there was some heterogeneity in responses to hyperpolarizing steps. We saw inward rectification (i.e., smaller voltage responses to larger hyperpolarizing current steps) in many, but not all, NAcc cells (Fig. (Fig.11A). Most NAcc neurons displayed a rapid “sag” (a reduction in the electrotonic potential over the duration of the current step, thought to be an expression of inwardly rectifying conductances; Fig. Fig.1A,1A, arrow). However, we found that some cells displayed only a sag (n = 4) or a rectification (n = 11) or both (n = 24). To better quantify these features, we pooled neurons displaying rectifying properties in plots of theirV–I curves. As shown in Figure Figure11B, plots of both the “instantaneous” and the steady-state V–Irelationships in the hyperpolarized range were inwardly rectifying.

In voltage-clamp mode, hyperpolarizing steps revealed fast inward current relaxations that could represent either a K+ inward rectifier current (IRK) or the so-called Q- or H-current (Halliwell and Adams, 1982; Surmeier et al., 1991), with a time course similar to the sag seen in current clamp. Superfusion of 2 mmCs+ had complex effects on the hyperpolarizing conductances of NAcc neurons (n = 7): overall input conductance dramatically decreased, whereas the inward relaxation depended on the size of the voltage command (Fig. (Fig.11C). Plots ofI–V curves obtained from such Cs+ studies averaged from all seven of the cells showed a voltage-sensitive reduction by Cs+ of the inward rectification (Fig.(Fig.11D). Ba2+ (1 mm), known to block several types of K+ channels including the IRK, also dramatically reduced overall membrane conductance and the inward rectification, but in a nonvoltage-sensitive manner (Fig.(Fig.11E).

Synaptic components elicited by local stimulation

Local stimulation of NAcc near the recording pipette evoked multicomponent postsynaptic potentials (PSPs). FigureFigure22A shows PSPs elicited by low intensity local stimulation (4 V), superimposed on different membrane potentials, and the effect of selective GABAA and AMPA/kainate receptor antagonists (bicuculline and CNQX, respectively). In control conditions (without any blocker in the superfusion ACSF), the PSP showed a very fast rise time (5 msec) and large amplitude (up to 30 mV for the most hyperpolarized potential), as well as a fast decay. The PSP amplitude decreased with cell depolarization and gave rise to a spike for the most depolarized potential. At this potential the duration of the PSP was longer than at RMP. Subsequent blockade of GABAA receptors by bicuculline (15 μm) strongly decreased the amplitude of this synaptic component at all potentials, with a more pronounced effect at the most hyperpolarized potential, demonstrating the presence of a prominent GABAergic component. Bicuculline did not affect the rapid rise time of the remaining EPSP. When we superfused CNQX (10 μm) in addition to bicuculline, the remaining EPSP was blocked almost completely at this low stimulus intensity (Fig. (Fig.22A). Figure Figure22B plots the stimulus intensity versus the average amplitude of the PSP component at the RMP for eight cells treated as described above. Bicuculline markedly attenuated the mean input–output curve, shifting it to the right and well below the spike threshold (dashed line). With CNQX superfusion along with bicuculline, there was an additional large decrease of the remaining mean EPSP amplitude; only a small EPSP was left at the lowest stimulus intensities. However, increasing the stimulus intensity up to 9 V elicited a larger CNQX- and bicuculline-resistant synaptic component (filled triangles ).

Characterization of different synaptic components evoked by local stimulation in NAcc. A, PSPs evoked with a low stimulus intensity (4 V, arrows) at three different membrane potentials (RMP = −85 mV; KCl electrode). The PSP evoked without any blocker (Control) was strongly reduced by bicuculline (Bic; 15 μm). When CNQX (10 μm) was added to the bath together with Bic, the PSP was almost abolished. B, Input–ouput graph of the mean (±SEM) relationship between stimulus intensity and PSP amplitude measured at RMP in a group of seven neurons treated as shown in A. Note that, for the higher intensities, there was a bicuculline/CNQX-resistant (probable NMDA) component (see Fig. Fig.4).4). Dashed line is spike threshold.

NMDA synaptic components

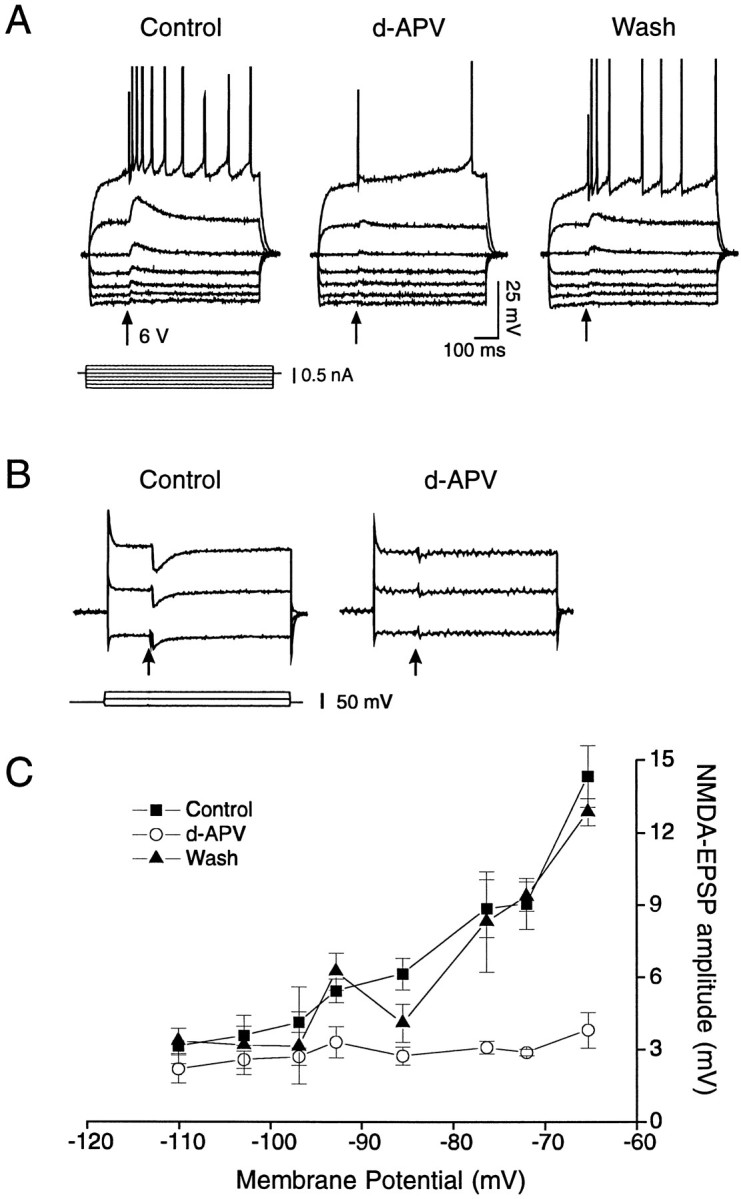

To characterize further the CNQX- and bicuculline-resistant synaptic component elicited by strong local stimulation, we evoked it at different membrane potentials in current- and voltage-clamp mode and examined the effect of the specific NMDA receptor antagonistd-APV. Figure Figure33A shows that local stimulation in current clamp could elicit a PSP component, the characteristics of which were equivalent to EPSPs mediated by NMDA receptor activation. Thus, EPSP amplitude increased as the cell was depolarized, with a corresponding shift of the time to peak (e.g., 7 msec at −114 mV, 9 msec at −107 mV, 30 msec at −84 mV, and 38 msec at −74 mV; see Fig. Fig.33A). In addition, the EPSP duration (up to 200 msec or more) was much longer than for non-NMDA–EPSPs (30–50 msec). Superfusion of 60 μmd-APV almost completely abolished the evoked EPSP.

Pharmacological isolation and characterization of the NMDA–EPSP component in NAcc neurons elicited by stronger local stimulation (arrows) in the presence of bicuculline (15 μm) and CNQX (20 μm). A, Voltage recording of the NMDA–EPSPs at different membrane potentials; the amplitude and the duration increased as the cell was depolarized. Note the presence of this component at RMP (−84 mV) and at even more negative potentials. In the presence of d-APV (60 μm, 5 min) the NMDA–EPSP component was abolished almost completely, followed by a partial recovery on washout (20 min).B, Voltage-clamp recording of NMDA–EPSCs; like the EPSPs, the EPSC amplitude increased as the cell (RMP =Vh = −85 mV) was depolarized and was blocked by d-APV superfusion (60 μm, 15 min).C, Average NMDA–EPSP amplitudes (mean ± SEM;n = 7) at different membrane potentials before (filled squares), during (open circles), and after d-APV (filled triangles).

Although these data argue strongly in favor of the presence of NMDA–EPSPs in NAcc core neurons, we recorded some cells in voltage-clamp mode to minimize the likelihood that the increased amplitude of this component at depolarized potentials was attributable to the activation of voltage-dependent Ca2+channels (Deisz et al., 1991). Figure Figure33B shows NMDA–EPSCs recorded at three different potentials, in which the amplitude as well as the duration of the EPSCs increased with depolarization. This component was blocked almost completely by 60 μmd-APV. In plots of NMDA–EPSC amplitudes at different membrane potentials (Fig. (Fig.33C), again there was a strong increase of the amplitude at depolarized potentials, andd-APV greatly reduced NMDA–EPSP amplitudes. It is interesting that with stronger local stimulation the presumed NMDA–EPSP could be elicited at relatively negative resting potentials.

DAMGO Effects

NAcc membrane properties

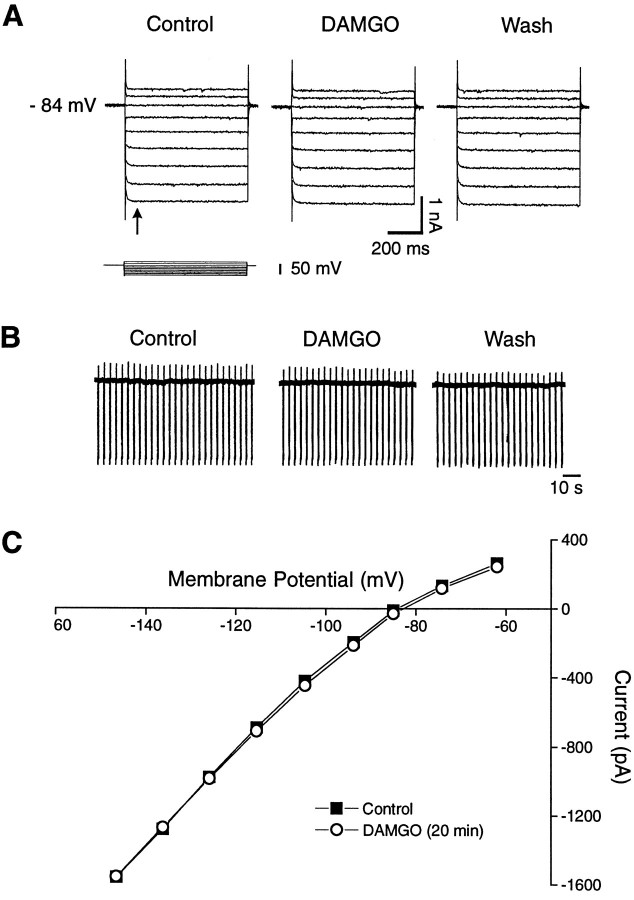

We used voltage-clamp mode to assess whether DAMGO alters membrane conductances in NAcc neurons, as described for some other CNS neurons. As shown in Figure Figure44A, negative voltage steps (from a holding potential of −84 mV) gave rise to the rapid inward relaxation (arrow) described above, the amplitude of which increased with hyperpolarization. Superfusing DAMGO (1 μm) for up to 20 min did not affect this relaxation. DAMGO also did not alter the membrane potential or conductance in either the hyperpolarizing or depolarizing range. FigureFigure44B shows a similar lack of effect for another cell recorded at a slower time base. Here, there was no significant DAMGO effect either on the current response to voltage steps or on the baseline holding current (control, 0 pA; DAMGO, 0.1 pA; washout, 0.1 pA). Figure Figure55C is a plot of the meanI–V relationship for a group of 12 cells showing that the curve taken during DAMGO is virtually superimposable on the control curve.

Lack of effect of DAMGO (1 μm) on the membrane properties of NAcc core neurons. A, Voltage-clamp recordings show membrane responses to positive and negative voltage steps (600 msec duration, 10 mV voltage increments). Jumps to potentials more negative than 100 mV evoked a fast inward relaxation (arrow), the amplitude of which increased as the cell was hyperpolarized. The application of DAMGO (20 min) did not induce any measurable effect on this relaxation or on either membrane potential (RMP = −84 mV) or membrane conductance.B, Another cell recorded at a slower time base: resting membrane current with downward deflections representing current responses to a constant hyperpolarizing voltage step (400 msec, 10 mV) applied every 4 sec. The cell was held at RMP (−86 mV). DAMGO (1 μm, 15 min) changed neither the membrane conductance nor the holding current. C, The average membrane currents from 12 cells tested with DAMGO. Note again the lack of measurable DAMGO effect on membrane current or conductance (open circles).

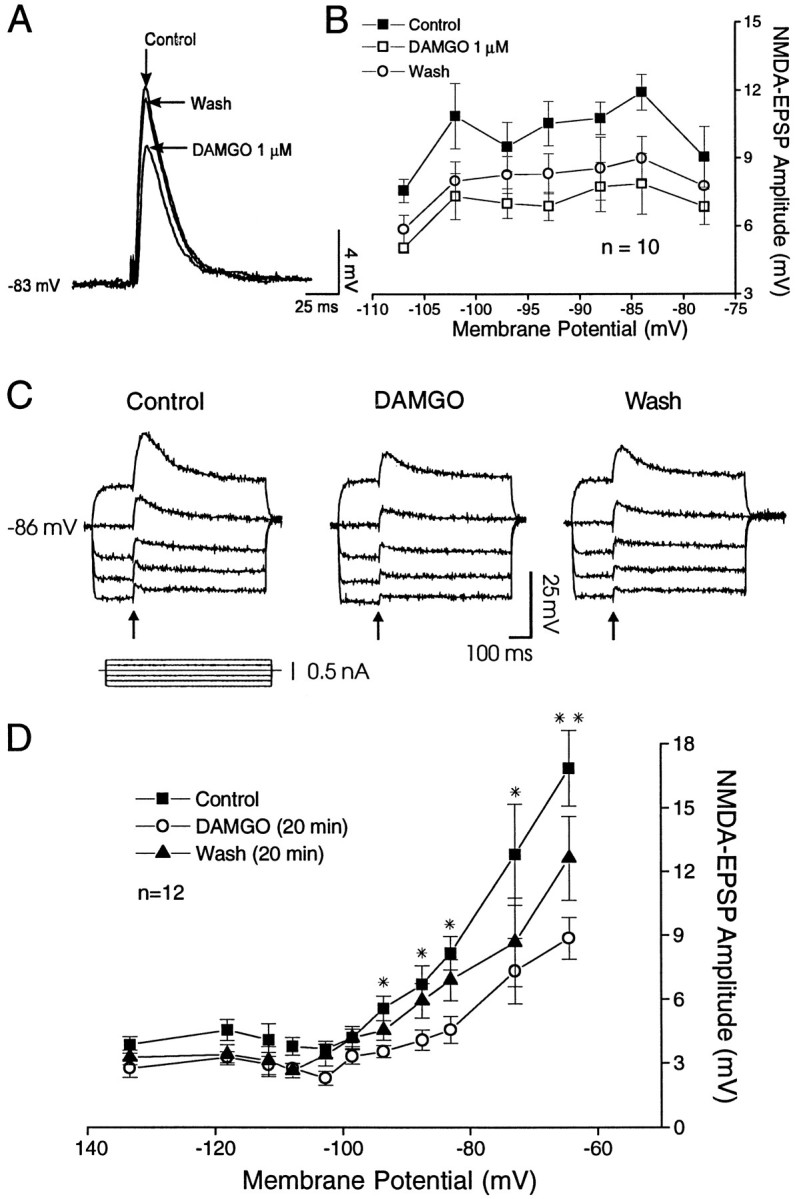

Effect of 1 μm DAMGO on pharmacologically isolated non-NMDA– and NMDA–EPSPs: current-clamp recordings of EPSPs evoked at different membrane potentials.A, In the presence of 60 μmd-APV and 15 μm bicuculline, 1 μm DAMGO decreases non-NMDA EPSPs evoked by local stimulation in NAcc, as compared with control, with recovery on washout. B, Plot of non-NMDA–EPSP amplitudes (mean ± SEM) versus membrane potential (n = 10) showing little voltage dependence over the range studied. DAMGO clearly reduced mean non-NMDA–EPSP amplitudes over all of the voltages studied, with partial recovery on washout (see text). C, In the presence of 20 μm CNQX and 15 μmbicuculline, DAMGO (1 μm, 20 min) decreased the NMDA–EPSP amplitudes and durations at all potentials tested (RMP = −85 mV), as compared with control. This inhibition was particularly apparent at the most depolarized potential and was followed by a partial recovery on washout (Wash, 20 min).D, Plot of the average amplitude (mean ± SEM) of the NMDA–EPSP components (n = 12 cells) versus membrane potential showing that 1 μm DAMGO significantly reduced NMDA–EPSP amplitudes evoked in the depolarized range (see text for group statistics). Washout led to significant recovery (p < 0.002). Asterisks show significance for each potential: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.001.

Effect of DAMGO on EPSPs

With local stimulation in the presence of d-APV and bicuculline, DAMGO 1 μm markedly reduced non-NMDA (AMPA/kainate) EPSP components in NAcc neurons (Fig. (Fig.55A). When averaged over all EPSPs obtained at all membrane potentials, DAMGO reduced the non-NMDA EPSPs to 64% of control (Fig. (Fig.55B), with partial recovery on washout. These findings are consistent with our previous NAcc data obtained with remote stimulation at RMPs. With the use of an equivalent voltage-dependent protocol and local stimulation in the presence of CNQX and bicuculline in another group of NAcc neurons, DAMGO (1 μm) superfusion also markedly decreased NMDA–EPSP amplitudes, followed by partial recovery on washout (Fig. (Fig.55C). Averaging NMDA–EPSP amplitudes for each voltage level over a range of potentials (Fig. (Fig.55D), DAMGO significantly decreased the NMDA–EPSPs (to 60 ± 2.3% of control; F(2,116) = 46.5; p < 0.0001). (However, as shown in Fig. Fig.55D, the difference was not statistically significant at the most hyperpolarized potentials.) This decrease was followed by a significant recovery (F(2,57) = 10.36; p < 0.002).

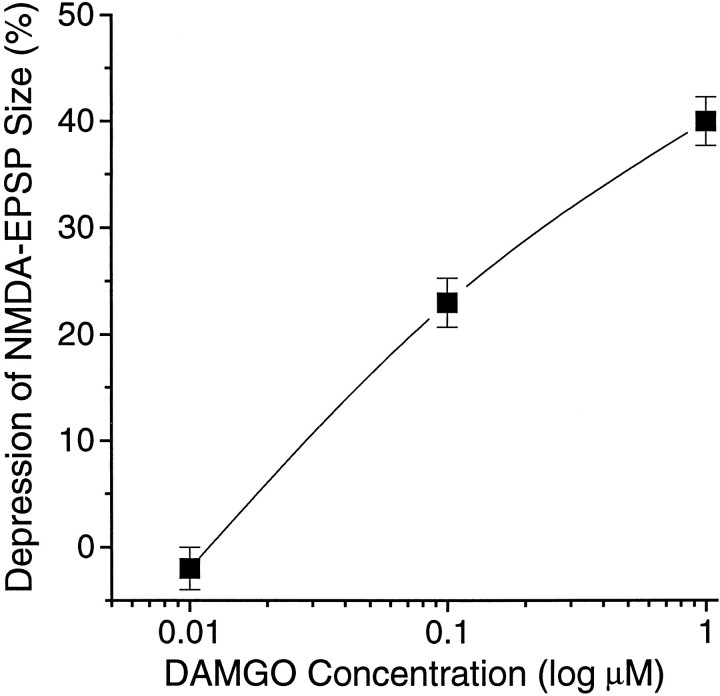

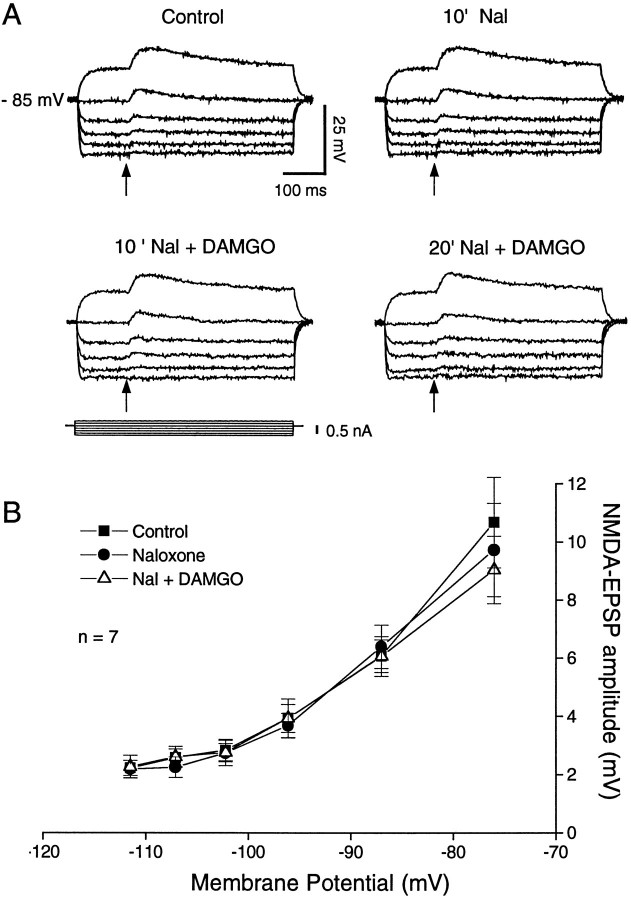

The decrease of the NMDA–EPSP amplitudes by DAMGO was dose-dependent (Fig. (Fig.6).6). At the lowest concentration (0.01 μm), DAMGO had no measurable effect on the EPSP amplitude (102 ± 2.0% of control). By contrast, 0.1 μm DAMGO significantly (F(2,80) = 26.1; p < 0.0001) decreased NMDA–EPSP amplitudes to 77% ± 2.3% of control. As noted above, 1 μm DAMGO significantly reduced NMDA–EPSPs to 60% of control. We did not test DAMGO concentrations >1 μm on EPSPs because of the likelihood of nonspecific activation of δ- and κ-opiate receptors (see below). Although the low effective concentration of DAMGO (0.1–1 μm) suggests a selective μ-opioid receptor effect, we also examined specific opiate antagonists to verify further the type of receptor involved. Superfusion of the relatively nonselective opiate antagonist naloxone (1 μm) alone had no effect per se on the evoked NMDA–EPSP amplitudes (Fig. (Fig.7).7). However, when 1 μm DAMGO was added to the bath after naloxone, there was no decrease of the NMDA–EPSP amplitudes (F(2,52) = 0.072; p = 0.78;n = 9; Figure Figure77A,B), suggesting involvement of opiate receptors in the DAMGO effect.

Dose–response relationship for DAMGO reduction of the NMDA–EPSP amplitudes; percentage of inhibition of EPSP amplitude (control amplitude as 100%) plotted as a function of increasing DAMGO concentration (log scale). The apparent maximum effect (40 ± 2.3% reduction, n = 12) was obtained with 1 μm; 0.01 μm had virtually no effect (n = 7).

Naloxone (1 μm) prevents the DAMGO (1 μm)-induced decrease of NMDA–EPSP amplitudes.A, NMDA–EPSPs recorded at different membrane potentials did not display any significant change of amplitude in the presence of naloxone. When DAMGO (20 min superfusion) was added together with naloxone (10 min), there was again no significant change of the NMDA–EPSP amplitudes. B, Plot of mean ± SEM NMDA–EPSP amplitudes versus membrane potential. For all seven cells treated as described in A, note the complete lack of DAMGO effect except, perhaps, a small decrease at the most depolarized membrane potential.

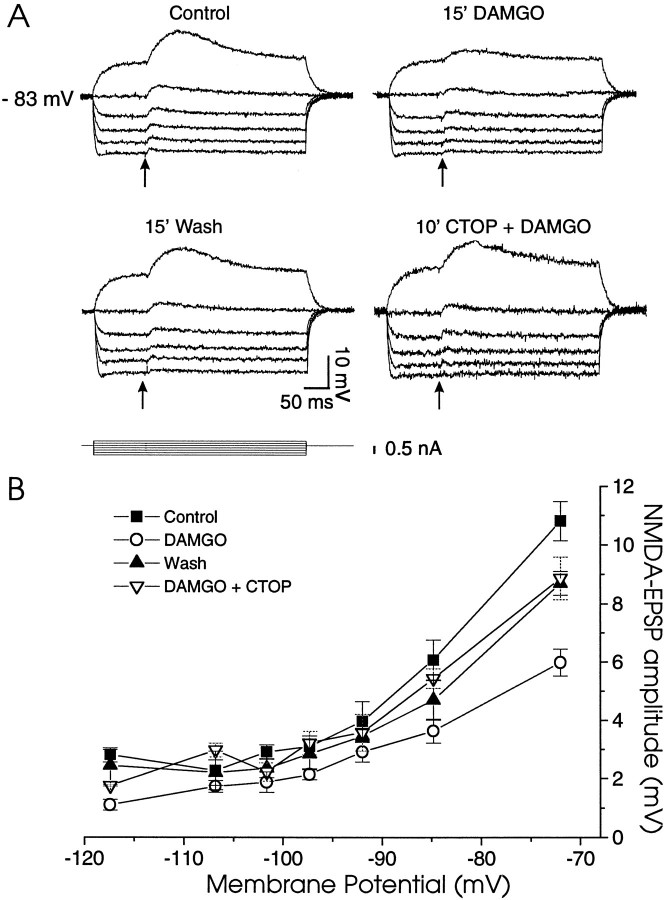

We also tested the effect of a more specific antagonist of the μ-opiate receptor CTOP. Figure Figure88Ashows CTOP (0.5 μm) blockade of DAMGO depressant effects (bottom right panel) in a NAcc neuron that previously showed DAMGO inhibition (top right panel) of pharmacologically isolated NMDA–EPSPs. Averaged over all seven of the neurons studied, CTOP nearly completely antagonized the inhibitions induced by DAMGO (Fig. (Fig.88B); plotted as means (± SEM) of the NMDA–EPSP amplitudes over different membrane potentials, the depressant effect of DAMGO on EPSP amplitudes was significant (F(3,84) = 21.29; p < 0.0001) before CTOP superfusion, but not after (F(2,28)= 2.99; p = 0.09). These combined data suggest that μ-opioid receptors mediate the DAMGO-induced decrease of the NMDA–EPSP amplitude.

The μ-specific antagonist CTOP prevents the DAMGO reduction of NMDA–EPSPs. A, Current-clamp recording of NMDA–EPSPs at different membrane potentials. DAMGO alone markedly reduced the NMDA–EPSP amplitudes but had no effect in the presence of CTOP (0.5 μm). B, Plot of mean NMDA–EPSP amplitudes versus membrane potential taken from seven cells treated as shown in A. CTOP (0.5 μm) nearly completely blocked the DAMGO effect.

DAMGO effects on exogenous AMPA, kainate, and NMDA currents

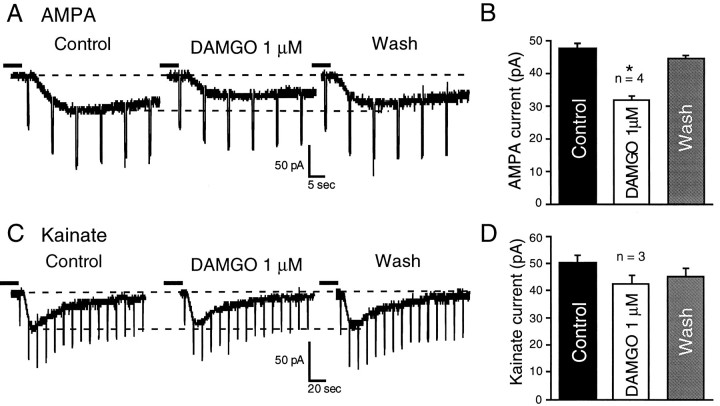

Because DAMGO reduced both the non-NMDA and NMDA–EPSPs, the effects of DAMGO could be mediated by either pre- or postsynaptic actions. Indeed, DAMGO has been reported to enhance NMDA responses by a postsynaptic action in various preparations (Chen and Huang, 1991;Martin et al., 1993; Oz et al., 1994; Zhang et al., 1994). To assess the site and specificity of opioid action, we applied AMPA, kainate, or NMDA locally from pipettes or via rapid superfusion (NMDA) in the presence of 15 μm bicuculline and 30 μmd-APV (for AMPA/kainate currents) or 10 μmCNQX (for NMDA currents), and in 1 μm TTX to reduce presynaptic effects. Local application of AMPA or kainate elicited inward currents in NAcc neurons that subsequently were blocked by 10 μm CNQX. Superfusion of 1 μm DAMGO decreased current responses to the non-NMDA agonists AMPA and kainate (Fig. (Fig.9).9). When averaged across all four of the NAcc cells studied, DAMGO significantly reduced AMPA currents (Fig.(Fig.99B) by a mean of 33% (F(2,6) = 116,072; p < 0.0001), with nearly complete recovery on washout. DAMGO also reduced kainate currents (Fig. (Fig.99D) in three other NAcc neurons by a mean of 16%; however, this trend was not significant (F(2,2) = 10.14; p = 0.089).

DAMGO superfusion decreases current responses to exogenously applied non-NMDA agonists AMPA or kainate.A, In a NAcc neuron, 1 μm DAMGO reduces by 45% the inward current amplitude evoked by local AMPA application via pipette. Rapid downward deflections are current responses to constant voltage steps used to monitor input conductance.Vh = RMP = −89 mV. B, Mean ± SEM data averaged from all four NAcc cells tested with local AMPA application, showing a 31% decrease of the mean AMPA current; *p < 0.0001. C, Another NAcc neuron; 1 μm DAMGO reduces by 18% the inward current evoked by kainate applied by pipette.Vh = RMP = −81 mV. In bothA and C, dashed linesindicate holding current (top) and peak control agonist current (bottom). D, Mean ± SEM data averaged from all three NAcc cells tested with local kainate application, showing a 17% decrease of the mean kainate current (p = 0.089). The time between solution changes was 8–15 min for all cells.

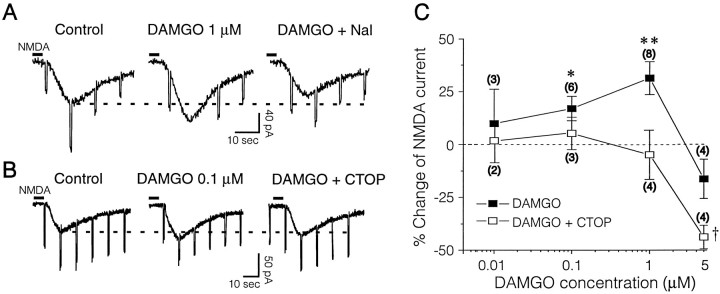

To test DAMGO interactions with NMDA, we held each cell at a fairly depolarized potential (approximately −65 mV) to reduce the voltage-dependent NMDA receptor blockade by Mg2+. FigureFigure1010A shows that NMDA application also induced inward currents. However, in contrast to DAMGO effects on AMPA and kainate currents, NMDA current amplitudes were significantlyincreased after 1 μm DAMGO, in some cells by up to 75% of control, with a mean increase of 31% (F(2,16) = 32.22; p < 0.0002) averaged over all eight of the cells studied. In two of these cells, subsequent superfusion of d-APV totally blocked the NMDA currents. Superfusion of 1 μm naloxone significantly antagonized the effect of DAMGO (Fig. (Fig.1010A), as it did in five other cells so tested. In addition, we examined the dose–response relationship of DAMGO effects on NMDA currents (Fig.(Fig.1010C). Interestingly, although 0.1 μm(F(2,10) = 11.75; p < 0.024) and 1.0 μm (statistics above) DAMGO significantly increased NMDA currents, 5 μm DAMGO actually reduced them (although not significantly; p = 0.09) on average, creating an inverted U-shaped curve. This U-shaped curve precluded assessment of a maximal DAMGO enhancement of NMDA currents (Vmax) or fitting to a logistic equation. Therefore, we could not calculate a true EC50 for the enhancement, although we estimate an apparent EC50 of ~0.1 μm DAMGO. The enhancement of NMDA currents, but not the reduction by 5 μm DAMGO, was blocked totally by 0.5–1 μm CTOP (Fig. (Fig.1010B,C), suggesting the involvement of μ receptors in the enhancing effect. Note that at 5 μm DAMGO, CTOP significantly enhanced (F(2,6) = 15.34; p = 0.004) the depressant effects of DAMGO, suggesting a nonspecific effect of DAMGO at this concentration and a possible balance between opposing effects on two different receptor populations or sites (see the dynorphin effect in Chen et al., 1995).

DAMGO enhances postsynaptic responses to exogenous NMDA. A, Voltage-clamp recording of a NAcc neuron (RMP = −85; Vh = −68 mV), showing inward currents in response to exogenous NMDA that are augmented by 1 μm DAMGO. Naloxone (1 μm) reverses the augmentation. B, Voltage-clamp recordings of another NAcc neuron (RMP = −88 mV;Vh = −70 mV) also showing inward currents in response to exogenous NMDA. In both A andB the slice was pretreated with CNQX (10 μm), bicuculline (30 μm), and TTX (1 μm). Pressure application (2 sec duration) of NMDA (200 μm) from a pipette near the recording electrode induced the pronounced inward currents. Brief downward deflections were current responses to constant voltage steps used to monitor input conductance. In contrast to its action on the NMDA–EPSP evoked by endogenous glutamate release and to its effects on AMPA and kainate currents, DAMGO enhanced the exogenous NMDA-induced currents. This action was antagonized completely by 1 μm naloxone (A) or 0.5 μm CTOP (B).C, Concentration–response relationships of the DAMGO–NMDA interaction and the effect of 0.5–1 μm CTOP. NMDA was applied either by pressure (200 μm in the pipette) or by rapid superfusion (30 μm).Numbers in parentheses denoten cells tested at each concentration. Note that CTOP totally blocks the enhancement of NMDA currents at all DAMGO concentrations but actually augments the depression of NMDA currents by 5 μm DAMGO, suggesting involvement of nonspecific DAMGO effects at this high concentration (perhaps the dynorphin site of Chen et al., 1995). Statistics: *p = 0.024 (DAMGO vs control); **p < 0.0002 (DAMGO vs control);†p = 0.004 (for CTOP plus DAMGO vs control).

Summary of results

This intracellular study of NAcc neurons has yielded several pieces of data: (1) the transmembrane properties of NAcc core neurons seem heterogeneous in terms of the presence of a sag in response to hyperpolarizing steps, inward rectification, and a slow ramp response to depolarizing steps; (2) these neurons reveal several synaptic components evoked by local stimulation with pharmacological isolation, including an NMDA–EPSP, an AMPA/kainate-EPSP, and a GABAA-ergic component; (3) the μ-specific agonist DAMGO had no effect on membrane potential or conductance; (4) DAMGO significantly decreased both the non-NMDA and NMDA–EPSPs dose dependently (the NMDA–EPSP effect was naloxone- and CTOP-sensitive); (5) DAMGO 1 μm reduced responses to exogenously applied AMPA and kainate (although insignificantly for kainate); (6) in contrast, DAMGO 0.1–1 μm superfusion markedly augmented postsynaptic responses to exogenously applied NMDA, an effect blocked by naloxone and CTOP; (7) DAMGO 5 μm reduced NMDA currents by a non-μ receptor mechanism.

DISCUSSION

Features of NAcc core neurons

Membrane properties

In this study all stable neurons recorded had large RMPs (mean, −85 mV). Several features of these NAcc neurons (inward rectification, the sag in hyperpolarizing potentials, and a depolarizing ramp) mainly agree with those reported by Uchimura et al. (1989a,b) and our laboratory (Yuan et al., 1992; Nie et al., 1993). The ramp may reflect the presence of a K+ conductance: either the D-current described by Storm (1988) or a slow A-current (Surmeier et al., 1991;Nisenbaum et al., 1994). The sag may represent an inward rectifying K+ conductance or the inward rectification, termedIH or IQ, mediated by nonselective cationic currents. The inward relaxations elicited by hyperpolarizing steps in voltage-clamp resemble those reported byUchimura et al. (1989a) for NAcc cells with large RMPs. This relaxation has fast kinetics; Cs+ inhibits it voltage dependently, as previously shown for cortical neurons (Galvan and Constantini, 1983). The corresponding inward rectification also is antagonized greatly by 1 μm Ba2+. These features, and nonlinearities in the instantaneous V–I curves, are consistent with a true inward rectifier K+ channel (IRK). Because of the sag and inward relaxations with apparent biphasic kinetics, this channel may coexist with other inwardly rectifying conductances, such as the H- or Q-currents (carried by both Na+ and K+) described for striatal (Uchimura et al., 1989a) and hippocampal neurons (Halliwell and Adams, 1982). We found some cells that showed only a sag or a rectification in theV–I curves, whereas two-thirds of the cells displaying a sag also showed rectification. Although these data suggest the presence of multiple neuronal populations, they also may represent multiple states of the same cell type.

NMDA–EPSPs

We have shown that local monosynaptic stimulation, in contrast to our former peritubercle stimulation site (Yuan et al., 1992; Nie et al., 1993), consistently elicits NMDA–EPSPs and probable depolarizing GABAA-IPSPs at RMPs, in addition to the AMPA/kainate glutamatergic component previously reported (Nie et al., 1993). This is consonant with data from guinea pig NAcc (Uchimura et al., 1989b) showing that the synaptic component evoked by focal stimulation comprises a sizable NMDA–EPSP. Furthermore, neurons of the NAcc express the receptor subunits NMDAR1 and NMDAR2A or 2B (Petralia et al., 1994b), which could constitute a functional receptor (McBain and Mayer, 1994).

The presence of NMDA–EPSPs at hyperpolarized potentials (−85 mV or more negative) in NAcc neurons contrasts with assumptions that NMDA channels are blocked completely by Mg2+ at these potentials (Nowak et al., 1984). Our findings also contrast with data by Pennartz et al. (1990, 1991), who elicited mainly non-NMDA components at RMPs with local stimulation in the presence of normal Mg2+ levels. In our study, only AMPA/kainate and GABA components contributed to the synaptic responses at low stimulus intensities, whereas generation of NMDA–EPSPs required doubling the stimulus intensity. This suggests that more glutamate release is needed to overcome the Mg2+ blockade of the NMDA receptors at RMP to activate a larger population of receptors with low Mg2+ sensitivity. Sensitivity to Mg2+ varies with the subunit composition (Mori et al., 1992; Kawajiri and Dingledine, 1993; Monyer et al., 1994), another variable that could account for differences across studies.

Effects of μ receptor activation

On membrane properties

In this study 1 μm DAMGO did not significantly change membrane potential, conductance, or inward rectifying properties in NAcc neurons (see also Yuan et al., 1992). This finding contrasts with previous results that DAMGO hyperpolarizes a proportion of neurons in other CNS areas (Christie and North, 1988; Williams et al., 1988;Wimpey and Chavkin, 1991), generally by increasing a K+conductance (usually an inward rectifier). Other reports showed that μ agonists did not hyperpolarize most neurons in several structures (Caudle and Chavkin, 1990; Chen and Huang, 1991; Lupica et al., 1992;Xie et al., 1992; Akins and McCleskey, 1993; Martin et al., 1993; Moore et al., 1994), including striatum (Jiang and North, 1992). This disparity suggests that μ-agonist effects depend on the brain region or neuronal population studied. Most cells hyperpolarized by opioids had a low RMP (approximately −65 to −70 mV) compared with the NAcc cells in our study (−85 mV average) or in dentate (Moore et al., 1988b) or cortical neurons (Martin et al., 1993). Moreover, it has been suggested that both NAcc and caudate have two distinct neuronal populations: so-called “principal” cells with very negative RMPs and “secondary” cells (a small percentage of the total) with RMPs approximately −60 mV (Uchimura et al., 1990; Jiang and North, 1992).Jiang and North (1992) showed that DAMGO strongly hyperpolarized secondary cells, unlike its lack of effect on primary cells in the NAcc. However, we found no evidence for secondary cells in NAcc core, with respect either to membrane potential or DAMGO responses.

There is evidence that primary striatal cells are the main projection cells, whereas secondary cells are interneurons (Nisenbaum et al., 1988; Wilson et al., 1990; Jiang and North, 1991). Some neurons hyperpolarized by opioids may represent interneurons (Madison and Nicoll, 1988). However, opioids also can hyperpolarize cells other than interneurons (North and Williams, 1983; Christie and North, 1988). The well established opiate receptor linkage to different G-proteins (Shen and Crain, 1990; Eriksson et al., 1992; Barg et al., 1993; Laugwitz et al., 1993; Jackisch et al., 1994; Prather et al., 1994) may explain the different opioid effects. G-protein diversity is such that their coupling to opiate receptors could lead to non-K+ channel effects, such as changes in phosphorylation of ligand-gated receptor/channel complexes.

DAMGO effects on NMDA responses

We found that μ receptor activation in NAcc neurons decreased the amplitude of evoked NMDA–EPSPs (as well as non-NMDA–EPSPs) dose dependently, in agreement with studies on isolated glutamatergic EPSP components in other CNS regions (Pan et al., 1990; Rusin and Randic, 1991; Jiang and North, 1992; Wagner et al., 1992; Xie et al., 1992;Capogna et al., 1993; Glaum et al., 1994; Grudt and Williams, 1994;Tanaka and North, 1994). Previously, our group showed that DAMGO markedly decreased uncharacterized EPSPs in the NAcc evoked by stimulation of the peri-tubercle region (Yuan et al., 1992). A major effect of opioids is a presynaptic action on interneurons or their terminals (Siggins and Zieglgänsberger, 1981; Madison and Nicoll, 1988; Lambert et al., 1991). Although the mechanisms controlling glutamate release are still debated, opiates can decrease Ca2+ currents (Meredith et al., 1990; Surprenant et al., 1990; Schroeder et al., 1991; Seward et al., 1991; Moises et al., 1994;Stefani et al., 1994) as well as hyperpolarize interneurons or terminals via potassium channel activation (Madison and Nicoll, 1988).

In the present studies, we have shown for the first time that μ receptor activation depresses NMDA–EPSPs (probably presynaptically, because non-NMDA–EPSPs were reduced equally) while postsynaptically augmenting currents induced by exogenous NMDA. Our postsynaptic DAMGO data confirm findings of Chen and Huang (1991) in cultured spinal cord neurons and, more recently, those of Oz et al. (1994) and Zhang et al. (1994) with NMDA subunits expressed in oocytes. The μ-opioid potentiation of NMDA currents could involve activation of protein kinase C (Chen and Huang, 1991; Martin et al., 1993) or protein kinase A (Colwell and Levine, 1995). A μ-opioid potentiation of NMDA responses in locus coeruleus was not affected by forskolin or a phorbol ester but was suggested to be dependent on membrane hyperpolarization induced by DAMGO (Oleskevich et al., 1993). However, in our studies and in all other studies cited above showing a DAMGO potentiation of NMDA currents, there was no change of membrane potential to account for the boost of NMDA responses. In addition, DAMGO augmentation of NMDA responses in NAcc runs counter to the DAMGO reduction of depolarizing responses to local application of glutamate (Yuan et al., 1990; Siggins et al., 1995) and, in the present study, of AMPA and kainate.

It is interesting to consider why postsynaptic potentiation of NMDA receptors seems not to compensate for opioid reduction of glutamate release. We were surprised to find that, whereas 0.1–1 μm DAMGO enhanced responses to exogenous NMDA, it reduced both NMDA– and non-NMDA–EPSPs to approximately the same percentage, probably via presynaptic reduction of glutamate release. Unfortunately, comparisons of percentage changes of EPSPs (evoked over a range of potentials) with the enhancement of exogenous NMDA (tested only at −60 to −70 mV) are unwise, because their voltage dependencies and recording conditions were so diverse (compare Fig. Fig.5,5, B vsD). The possibility that subsynaptic non-NMDA glutamate receptors, along with NMDA receptors, are both enhanced postsynaptically is not likely, because depolarizing responses of NAcc neurons to exogenous glutamate (Yuan et al., 1990; Siggins et al., 1995) or AMPA and kainate (present study) were reduced most often, not enhanced, by DAMGO superfusion. Another possibility is a site-dependent interaction, whereby subsynaptic μ receptors are linked directly to subsynaptic NMDA receptors (see Petralia et al., 1994a), and the short-term DAMGO superfusion used here did not allow access to these subsynaptic sites but did reach extra- and presynaptic ones. However, this does not seem likely, because such linkages to ligand-gated channels usually involve G-proteins activating nonmembrane-delimited diffusible second messengers (cf. Chen and Huang, 1991). A more likely site-dependent possibility is that subsynaptic NMDA receptors (Petralia et al., 1994a), easily accessed by synaptically released glutamate, and extrasynaptic NMDA receptors (V. Pickel, personal communication), activated by exogenously applied NMDA, differ with respect either to subunit composition or to transduction linkage(s). Thus, NAcc neurons may require PKC activation for DAMGO enhancement of NMDA responses, as in spinal neurons (Chen and Huang, 1991); extrasynaptic NMDA receptors, but not subsynaptic ones, could be linked to the μ receptor/PKC transduction pathway. A site-dependent interaction of μ and NMDA receptors is supported by recent ultrastructural immunocytochemical studies showing predominately extrasynaptic “modulatory” localization of μ-opiate receptors in NAcc (Svingos et al., 1996). However, regardless of the mechanism, an important aspect of our findings is that, to be complete, future studies of μ/NMDA receptor interactions will require verification of μ receptor effects on synaptically activated NMDA receptors.

Physiological and behavioral relevance of opioid–glutamate interactions

The NAcc plays a role in motor and motivational functions (for review, see Pennartz et al., 1994). In addition, the NAcc has drawn much attention for its involvement in drug dependence (Koob et al., 1992). Chronic exposure to drugs such as opiates leads to long-lasting changes in terms of tolerance, dependence, and sensitization (Self and Nestler, 1995). The locus coeruleus may mediate some aspects of physical withdrawal via the interaction of opioid receptors with K+ channels and changes in second messenger systems (Nestler et al., 1993). By contrast, dependence, defined as the need for continued drug administration to avoid the negative effects of withdrawal, may involve the NAcc (Koob et al., 1992). Thus, administration of an opiate antagonist into the NAcc results in a dramatic loss of opiate reinforcement but little physical withdrawal (Stinus et al., 1990; Vaccarino et al., 1995).

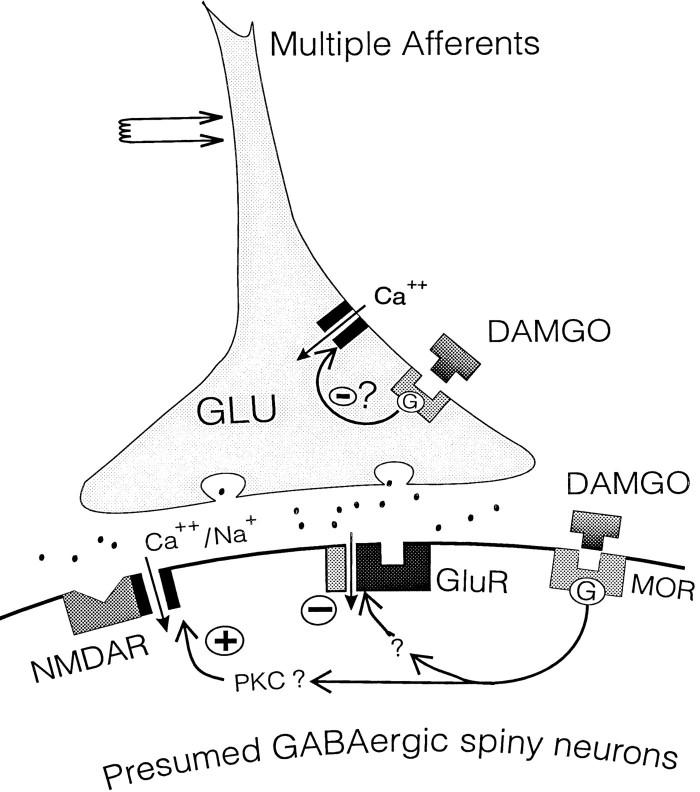

The mechanisms underlying dependence are unknown, although it correlates with modulation of adenylate cyclase activity via G-protein transduction systems (Self and Nestler, 1995). Other data suggest that dependence is controlled by glutamatergic transmission, because MK-801 treatment inhibits morphine dependence and tolerance in rats (Marek et al., 1991; Trujillo and Akil, 1991). However, the cellular mechanisms that underlie these effects have been a mystery. Our study has provided data suggesting that μ opioids can regulate the level of activation of NMDA receptors in NAcc neurons by a complex, balanced control at pre- and postsynaptic (and possibly extrasynaptic) sites (Fig.(Fig.11).11). We hypothesize that a disruption of this balance occurs with chronic opiate treatment, leading to tolerance and dependence. Recent observations of changes in NAcc receptor subunit composition with chronic morphine treatment (Fitzgerald et al., 1996), as well as our recent studies showing altered NMDA receptor function in morphine-dependent rats (Martin et al., 1996), lend credence to this hypothesis.

Schematic of proposed loci of μ-receptor regulation of glutamatergic synapses. DAMGO may act on μ-opiate receptors (MOR) at two sites, pre- and postsynaptic. Presynaptic reduction of glutamate release could occur via reduction of spike-generated Ca2+ currents, and the postsynaptic enhancement of NMDA currents could be mediated by activation of protein kinase C (PKC), as previously reported (see text for references). MOR also may interact negatively with AMPA/kainate receptors (GluR) via an unknown mechanism.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DA03665 and AA06420. We thank W. Francesconi, P. Schweitzer, S. J. Henriksen, S. Madamba, G. Koob, and W. Zieglgänsberger for helpful discussions and criticisms of this manuscript, and we thank F. Bellinger for technical assistance.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. George Robert Siggins, Department of Neuropharmacology, The Scripps Research Institute, 10555 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, CA 92037.

REFERENCES

Articles from The Journal of Neuroscience are provided here courtesy of Society for Neuroscience

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.17-01-00011.1997

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://www.jneurosci.org/content/jneuro/17/1/11.full.pdf

Free after 6 months at www.jneurosci.org

http://www.jneurosci.org/cgi/content/full/17/1/11

Free to read at www.jneurosci.org

http://www.jneurosci.org/cgi/content/abstract/17/1/11

Free after 6 months at www.jneurosci.org

http://www.jneurosci.org/cgi/reprint/17/1/11.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Article citations

Mu-opioid receptor-dependent transformation of respiratory motor pattern in neonates in vitro.

Front Physiol, 13:921466, 22 Jul 2022

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 35936900 | PMCID: PMC9353126

Opioid Receptor-Mediated Regulation of Neurotransmission in the Brain.

Front Mol Neurosci, 15:919773, 15 Jun 2022

Cited by: 34 articles | PMID: 35782382 | PMCID: PMC9242007

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Magnesium and Morphine in the Treatment of Chronic Neuropathic Pain-A Biomedical Mechanism of Action.

Int J Mol Sci, 22(24):13599, 18 Dec 2021

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 34948397 | PMCID: PMC8707930

The opioid antagonist naltrexone decreases seizure-like activity in genetic and chemically induced epilepsy models.

Epilepsia Open, 6(3):528-538, 09 Jun 2021

Cited by: 8 articles | PMID: 34664432 | PMCID: PMC8408599

The role of orphan receptor GPR139 in neuropsychiatric behavior.

Neuropsychopharmacology, 47(4):902-913, 21 Jan 2021

Cited by: 9 articles | PMID: 33479510 | PMCID: PMC8882194

Go to all (101) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Ethanol inhibits glutamatergic neurotransmission in nucleus accumbens neurons by multiple mechanisms.

J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 271(3):1566-1573, 01 Dec 1994

Cited by: 103 articles | PMID: 7527857

Activation of kappa-opioid receptors depresses electrically evoked excitatory postsynaptic potentials on 5-HT-sensitive neurones in the rat dorsal raphé nucleus in vitro.

Brain Res, 583(1-2):237-246, 01 Jun 1992

Cited by: 31 articles | PMID: 1354563

Opioid-glutamate interactions in rat locus coeruleus neurons.

J Neurophysiol, 70(3):931-937, 01 Sep 1993

Cited by: 25 articles | PMID: 7693886

Glutamatergic transmission in opiate and alcohol dependence.

Ann N Y Acad Sci, 1003:196-211, 01 Nov 2003

Cited by: 86 articles | PMID: 14684447

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NIAAA NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: AA06420

NIDA NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: DA03665