Abstract

Free full text

Assessment of Resistance Components for Improved Phenotyping of Grapevine Varieties Resistant to Downy Mildew

Abstract

Grapevine varieties showing partial resistance to downy mildew, caused by Plasmopara viticola, are a promising alternative to fungicides for disease control. Resistant varieties are obtained through breeding programs aimed at incorporating Rpv loci controlling the quantitative resistance into genotypes characterized by valuable agronomic and wine quality traits by mean of crossing. Traditional phenotyping methods used in these breeding programs are mostly based on the assessment of the resistance level after artificial inoculation of leaf discs in bioassays, by using the visual score proposed in the 2nd Edition of the International Organization of Vine and Wine (OIV) Descriptor List for Grape Varieties and Vitis species (2009). In this work, the OIV score was compared with an alternative approach, not used for the grapevine-downy mildew pathosystem so far, based on the measurement of components of resistance (RCs); 15 grapevine resistant varieties were used in comparison with the susceptible variety ‘Merlot’. OIV scores were significantly correlated with P. viticola infection frequency (IFR), the latent period for the downy mildew (DM) lesions to appear (LP50), and the number of sporangia produced per lesion (SPOR), so that when the OIV score increased (i.e., the resistance level increases), IFR and SPOR decreased, while LP50 increased. The relationship was linear for LP50, monomolecular for IFR and hyperbolic for SPOR. No significant correlation was found between OIV score and DM lesion size, sporangia produced per unit area of lesion, length of infectious period, and infection efficiency of the sporangia produced on DM lesions. The correlation between OIV score and area under the disease progress curve (AUDPC) calculated by using the RCs and a simulation model was significant and fit an inverse exponential function. Based on the results of this study, the measurement of the RCs to P. viticola in grapevine varieties by means of monocyclic, leaf disc bioassays, as well as their incorporation into a model able to simulate their effect on the polycyclic development of DM epidemics in vineyards, represents an improved method for phenotyping resistance level.

Introduction

The ooomycete Plasmopara viticola originates from North America (Millardet, 1881) and is the causal agent of downy mildew (DM), one of the major diseases of Vitis vinifera L. worldwide. Its control still largely relies on fungicide treatments, which have environmental, social and economic impacts (Gessler et al., 2011). However, according to the Directive 2009/128/CE on the sustainable use of pesticides, the use of plant protection products has to be limited and alternative approaches to DM control are then needed (Rossi et al, 2012). The use of grapevine varieties showing partial resistance to DM represents an important tool for disease control (Töpfer et al., 2011) because it is compatible with other management options and does not have negative environmental impacts.

Wild grapevine species from North America and Asia, pertaining to the genera Vitis and Muscadinia, developed different mechanisms of resistance against P. viticola because of their coevolution with the pathogen (Kortekamp et al., 1997; Bellin et al., 2009; Casagrande et al., 2011; Gessler et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2012). The resistance response is conferred by quantitative trait loci (QTLs) named Rpv (meaning: “Resistance to P. viticola”); to date, 14 Rpv loci have been identified (Marino et al., 2003; Merdinoglu et al., 2003; Fischer et al., 2004; Wiedemann-Merdinoglu et al., 2006; Welter et al., 2007; Bellin et al., 2009; Marguerit et al., 2009; Peressotti et al., 2010; Blasi et al., 2011; Moreira et al., 2011; Di Gaspero et al., 2012; Schwander et al., 2012; Venuti et al., 2013; Ochssner et al., 2016; Zyprian et al., 2016; Sánchez-Mora et al., 2017). Depending on the Rpv locus and on the host genotype (Foria et al., 2018), the resistance responses to P. viticola infection involve different mechanisms, such as a hypersensitive response (Bellin et al., 2009; Venuti et al., 2013; Zyprian et al., 2016), callose and lignin accumulation (Dai et al., 1995; Kortekamp et al., 1997; Gindro et al., 2003), synthesis of stilbene phytoalexins (Pezet et al., 2004; Gindro et al., 2006), cell necrosis (Boso and Kassemeyer, 2008; Bellin et al., 2009; Zini et al., 2015), induction of peroxidase activity (Kortekamp et al., 1998; Toffolatti et al., 2012), and accumulation of phenolic compounds in the plant tissues surrounding the infection sites (Langcake, 1981; Alonso-Villaverde et al., 2011).

Since the discovery of the sources of resistance to P. viticola (Munson, 1909; Olmo, 1971), many breeding programs have been developed in order to obtain grapevine hybrids combining disease resistance genes from the wild grapevine species with the desirable agronomic and grape-quality traits carried by V. vinifera cultivars. From the beginning of the 20th century, several disease resistant varieties with a good level of grape quality and, in some cases, with a vinifera-like wine (Golodriga, 1978; Alleweldt, 1980; Bouquet, 1980; Kozma, 2002) have been selected and released by breeders. Some institutions are active in these breeding programs worldwide, including: Cornell University, UC Davis, and Florida AM University in the USA; several scientific institution in China (Lu and Liu, 2015); CSIRO in Australia; University of Krasnodar in Russia; JKI Gelweilerhof in Germany; INRA and IFV in France; University of Pécs in Hungary; and University of Udine, FEM, and CREA-VE in Italy (Bavaresco, 2019).

However, the use of resistant genotypes is still limited to few areas. Currently, resistant grapevine hybrids account for about 6% of the world grape-growing surface, with Kyoho (V. labrusca × V. vinifera), a Japanese table grape variety, being the most cropped one, especially in China (365,000 ha, OIV 2015 data). Resistant hybrids for wine production are mainly spread in America and Eastern Europe, specifically in Brazil (about 41,046 ha, 83% of the national viticultural surface), USA (about 11,980 ha, 5%), Moldova (about 11,656 ha, 13%), Russia (about 9,430 ha, 37%), Hungary (about 7,450 ha, 11%), Ukraine (about 3,251 ha, 6%), and Canada (about 2,680 ha, 27%) (Anderson, 2013). In the European Union (EU), the Regulation 1308/2013/EC states that resistant varieties can be grown to produce Table and PGI (Protected Geographic Indication) wines, but not PDO (Protected Denomination of Origin) wines (where only V. vinifera is allowed). In this respect, the situation is not uniform across the EU; for instance, Germany has classified the new disease resistant varieties as V. vinifera, unlike Italy and France.

The hybridization process using conventional breeding requires several years, but genetic engineering, marker assisted selection (MAS), genetic linkage maps, the availability of the V. vinifera genome sequence, and the knowledge of Rpv all help breeders in the selection of new resistant varieties. In addition to these methods, efficient phenotyping tools play a crucial role (Eibach et al., 2007; Töpfer et al., 2011; Schwander et al., 2012).

Traditional phenotyping is based on the evaluation of resistance after natural or artificial infection on leaves or leaf discs. Usually, the in vitro screening of partial resistance to DM is based on leaf disc bioassays (Bavaresco and Eibach, 1987; Staudt and Kassemeyer, 1995; Cadle-Davidson, 2008) and the assessment of the degree of resistance based on a visual score (from 1 = very low to 9 = very high), according to the 2nd Edition of the OIV Descriptor List for Grape Varieties and Vitis species (2009), i.e., the OIV 452-1 (hereafter referred to as OIV scale). In host-pathogen systems different from grape-P. viticola (Savary and Zadoks, 1989; Rossi et al., 1999; Rossi et al., 2000; Gordon et al., 2006; Burlakoti et al., 2010; Willocquet et al., 2011; Azzimonti et al., 2013; Schwanck et al., 2016), the measurement of resistance components (hereafter referred to as RCs) efficiently supports the evaluation of plant genotypes showing partial resistance, a type of resistance that affects several stages of the infection cycle, such as the resistance to P. viticola. Resistance components analysis is based on the phenotypic dissection of resistance into its components, which classically include: infection efficiency of spores, duration of latent period (i.e., the time from infection to the start of sporulation on lesions), lesion size, production of spores on lesions, and the duration of infectious period (i.e., the time a lesion continues producing spores) (Van der Plank, 1963; Zadoks, 1972; Parlevliet, 1979).

In a previous work, a resistance components analysis was conducted for 16 grapevine genotypes, some of them carrying one or more Rpv loci (Bove, 2018). In the present work, a comparison was made between the OIV scale and RCs with the aim of evaluating the relationships between the two phenotypic methods.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Inoculation

The resistance response of different grapevine varieties was previously measured in a three-year study (2014 to 2016) after artificial inoculation of leaf discs in environmentally controlled conditions (Bove, 2018). Fifteen partially resistant varieties, some of them carrying one or more Rpv loci known to be involved in the resistance to P. viticola, and the V. vinifera ‘Merlot’, which is susceptible to downy mildew, were used ( Table 1 ). Some of the resistant varieties consist of introgression lines developed in different European breeding institutes, such as the Julius-Kuehn Institute (JKI) and the Institute of Viticulture and Enology in Freiburg in Germany, and the University of Udine in collaboration with the Institute of Applied Genomics (IGA) in Italy.

Table 1

Grapevine varieties showing resistance to Plasmopara viticola used in leaf disc bioassays, their pedigree, the reference of the breeder, and Rpv loci.

| Variety | Pedigree | Breeder | Loci |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bronner* | Merzling × Geisenheim 6494 | Becker, N. (Freiburg) | Rpv10 |

| Cabernet Volos* | Cabernet sauvignon × 20/3 | Castellarin, S.D.; Cipriani, G.; Di Gaspero, G.; Morgante, M.; Peterlunger, E.; Testolin, R. (IGA) | Rpv12 |

| Calandro* | Domina × Regent | Eibach, R.; Töpfer, R. (JKI) | Rpv3.1 |

| Calardis blanc* | Geilweilerhof GA-47-42 × S.V. 39-639 KL.1 | Eibach, R.; Töpfer, R. (JKI) | Rpv3.1, Rpv3.2 |

| Felicia* | Sirius × Vidal Blanc | Eibach, R.; Töpfer, R. (JKI) | Rpv3 |

| Fleurtai* | Tocai × 20/3 | Castellarin, S.D.; Cipriani, G.; Di Gaspero, G.; Morgante, M.; Peterlunger, E.; Testolin, R. (IGA) | Rpv12 |

| Johanniter* | Riesling Weiss × Freiburg 589-54 | Zimmermann, J. (Freiburg) | Rpv3.1 |

| Merlot Kanthus* | ‘Merlot’ × 20/3 | Castellarin, S.D.; Cipriani, G.; Di Gaspero, G.; Morgante, M.; Peterlunger, E.; Testolin, R. (IGA) | Rpv3 |

| Merlot Khorus* | ‘Merlot’ × 20/3 | Castellarin, S.D.; Cipriani, G.; Di Gaspero, G.; Morgante, M.; Peterlunger, E.; Testolin, R. (IGA) | Rpv12 |

| Palava | Traminer × Mueller Thurgau | Veverka, J. (Czeck Republic) | – |

| Reberger* | Regent × Lemberger | Eibach, R.; Töpfer, R. (JKI) | – |

| Regent* | Diana × Chambourchin | Alleweldt, G. (JKI) | Rpv3.1 |

| Rkatsiteli | Unknown | - | – |

| Solaris* | Merzling × Geisenheim 6493 | Becker, N. (Freiburg) | Rpv10 |

| Villaris* | Sirius × Vidal blanc | Eibach, R.; Töpfer, R. (JKI) | Rpv3.1 |

The introgression lines (*) were developed in different European breeding institutes, such as the Julius-Kuehn Institute (JKI) and the Institute of Viticulture and Enology in Freiburg in Germany, and the University of Udine in collaboration with the Institute of Applied Genomics (IGA) in Italy (www.vivc.de).

The inoculation method is fully described in Bove (2018). In short, for each variety, fifteen fully developed leaves (specifically the fourth leaf from the shoot apex) were detached from five plants randomly selected at three growth stages (specifically at shoot growing BBCH 18, flowering BBCH 65 and fruit set BBCH 79; Lorentz et al., 1995) and immediately transported to the laboratory in a fridge at 5°C. Five leaf discs (21 mm diameter) were excised from each leaf using a cork borer. Leaf discs were repeatedly washed under tap water to remove superficial materials, dried under a laminar flow hood and finally placed, abaxial side up, in Petri dishes on filter paper wetted with 3 ml of sterile demineralized water. Each leaf disc was inoculated with four 10 µl drops of inoculum suspension containing a population of P. v0iticola at 5 × 105 sporangia ml−1 concentration. The inoculum suspension was prepared from freshly (2–3-day old) sporulating DM lesions obtained by inoculating the leaves of ‘Merlot’ plants grown in pots in a greenhouse by using a bulk of sporangia produced on field-grown leaves collected from different V. vinifera varieties in several untreated vineyards of northern Italy. Fresh sporangia produced on these leaves were collected, diluted in sterile water, adjusted to 5 × 105 sporangia ml−1, and immediately used for the inoculation of leaf discs. After inoculation, leaf discs were incubated at 20°C with a 12-h photoperiod.

Phenotypic Assessment Using the OIV Scale

Leaf discs were observed both visually and with the help of a microscope (at tenfold magnification), in order to observe single sporangiophores of P. viticola (Schwander et al., 2012), at 11 days post inoculation (dpi), and assigned to one DM resistance score based on the OIV scale (OIV, 2009), as follows: 1—very little degree of resistance to P. viticola (dense sporulation at 100% of inoculation sites, on large lesions); 3—little (dense sporulation at 50 to 75% of inoculation sites, on medium to large lesions; 5—medium (sparse sporulation at 50% to 75% of inoculation sites, on medium size lesions); 7—high (sparse sporulation at 25% of inoculation sites, on small size lesions); 9—very high (no sporulation) ( Figure 1 ). All the assessments were made by a single expert to minimize subjectivity.

Scores assigned to grape leaf discs inoculated with Plasmopara viticola sporangia to assess the level of resistance based on the OIV 452-1 descriptor: 1—very little degree of resistance (dense sporulation at 100% of inoculation sites, on large lesions); 3—little (dense sporulation at 50 to 75% of inoculation sites, on large lesions); 5—medium (sparse sporulation at 50 to 75% of inoculation sites, on medium size lesions); 7—high (sparse sporulation at 25% of inoculation sites, on small size lesions); 9—very high (no sporulation). Inoculation was performed by placing on each leaf disc four 10µl drops of a suspension of 5 × 105 sporangia ml−1.

Phenotypic Assessment Using the RCs

The following components of partial resistance were considered: i) infection frequency (IFR), ii) duration of latent period (LP50), iii) lesion size (LS), iv) number of sporangia per lesion (SPOR) and per mm2 of DM lesion (SPOR’), v) infectious period (IP), iv) infection efficiency of the sporangia produced on inoculation sites and re-inoculated on the susceptible variety ‘Merlot’ (INF). Methods for the measurements of RCs are described in Bove (2018). Briefly, IFR was measured at 11 dpi as the proportion of the inoculation sites showing DM sporulation over the total inoculated sites (where 0 = no inoculation sites show sporulation to 1 = all inoculation sites show sporulation). LP50 was measured in degree days (DDs, base 0°C) cumulated between the inoculation and when 50% of the inoculation sites resulting in lesions at 11 dpi showed a DM lesion. For the measurement of LS, leaf discs were photographed at 11 dpi and the area (in mm2) of each lesion was determined using the image analysis software Assess 2.0 (Lakhdar Lamari, APS PRESS, Saint Paul, Minnesota). SPOR was measured at 11 dpi as follows: sporangia produced on all the sporulating lesions of a leaf disc were carefully collected by using a sterile needle, suspended in 100 µl of sterile water, counted using a haemocytometer, and finally expressed as the number of sporangia per DM lesion. SPOR’ was also calculated by dividing the number of sporangia per lesion by the lesion size, and expressed as the number of sporangia per mm2 of DM lesion. IP was measured as the number of sporulating events on a DM lesion; after each sporulation, all the sporangiophores and sporangia were gently removed from the lesion using a sterile cotton swab, and this was repeated until the lesion no longer produced new sporangia. In order to measure INF, sporangia were collected at 11 dpi from leaf discs and then re-inoculated on new fresh leaf discs of ‘Merlot’, using the same procedure for inoculation and incubation previously described. INF was then measured as the proportion of inoculation sites showing DM sporulation on ‘Merlot’. The measurement procedures, the statistical analyses and all the details concerning the assessment of partial resistance components are described in Bove (2018).

µl of sterile water, counted using a haemocytometer, and finally expressed as the number of sporangia per DM lesion. SPOR’ was also calculated by dividing the number of sporangia per lesion by the lesion size, and expressed as the number of sporangia per mm2 of DM lesion. IP was measured as the number of sporulating events on a DM lesion; after each sporulation, all the sporangiophores and sporangia were gently removed from the lesion using a sterile cotton swab, and this was repeated until the lesion no longer produced new sporangia. In order to measure INF, sporangia were collected at 11 dpi from leaf discs and then re-inoculated on new fresh leaf discs of ‘Merlot’, using the same procedure for inoculation and incubation previously described. INF was then measured as the proportion of inoculation sites showing DM sporulation on ‘Merlot’. The measurement procedures, the statistical analyses and all the details concerning the assessment of partial resistance components are described in Bove (2018).

The following RCs: IFR, LP50, SPOR and IP, were incorporated into a model able to simulate downy mildew epidemics in partially resistant varieties. The model is described in Bove (2018). In short, the model captures the main features of the grapevine downy-mildew pathosystem, i.e. primary and secondary infections, physiology and dynamics of the host (crop growth, senescence and ontogenic resistance), and development of the disease on leaves and clusters. The parameterization of the model was performed according to the available literature (Bove, 2018) and considers the main environmental variables influencing the pathosystem (rain, wetness and temperature) by using a scenario approach. The model was developed by using the STELLA® software (Isee Systems, Inc, 2005). The model was operated in a favourable (i.e. not limiting) scenario for the disease, for each of the 16 varieties, by using the RCs measured in the leaf disc bioassay, so that the disease progress over time of the DM severity was simulated for each variety. The Area Under the Disease Progress Curve (AUDPC) (Campbell and Madden, 1990) was also calculated for comparing these epidemics.

Data Analysis

In order to compare the two phenotypic methods, a correlation analysis was conducted between OIV scores, each of the seven RCs, and the AUDPC, by calculating the Pearson’s correlation coefficient, r. When correlations were significant at P ≤ 0.05, a regression analysis was conducted by fitting different equations to the data, in which the OIV score was the independent variable and the RC or the AUDPC was the dependent one. All statistical analyses were all performed by using the SPSS software version 24 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Results

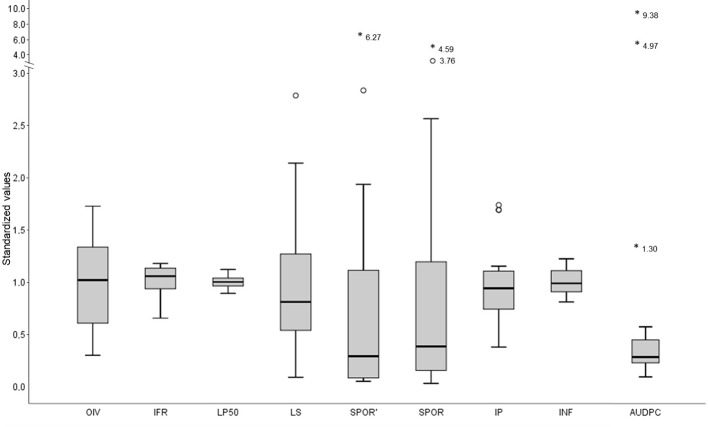

Results on the phenotypic assessment of partial resistance components have been shown in detail in Bove (2018). Box plots of Figure 2 show the distribution of OIV scores, components of resistance, and AUDPC in the 16 grapevine varieties. In Figure 2 , original values of single varieties were standardized by dividing them by the average of the 16 varieties, to facilitate comparisons among variables that are expressed in different units.

Box plots showing the distribution of OIV scores, components of partial resistance, and AUDPC in the 16 grapevine varieties. Original values of single varieties were standardized by dividing them by the average of the 16 varieties, to facilitate comparison among variables that are expressed in different units. OIV is the OIV score (average 4.6); IFR is the infection frequency of sporangia (average 0.83, in a 0-1 interval); LP50 is latent period (average 102 degree-days); LS is the lesion size (average 7.6 mm2); SPOR’ is the number of sporangia per mm2 lesion (average 344 sporangia × mm−2); SPOR is the number of sporangia per lesion (1,582 sporangia × lesion); IP is the infectious period (average 2.84 sporulation events); INF is the infectivity of the sporangia produced on the varieties and inoculated on the susceptible ‘Merlot’ (average 0.77 in a 0–1 interval); AUDPC is the area under the disease progress curve calculated using a simulation model (average 42,679). The box representing the AUDPC is multiplied by 10 to visually appreciate its distribution. The thick line in the boxes is the median; the lowest value in each box represents the 1st quartile (25th percentile); the top part of each box represents the 3rd quartile (75th percentile). Circles and asterisks in the graph are outliers, i.e. values that are far or very far from the rest of the values, respectively.

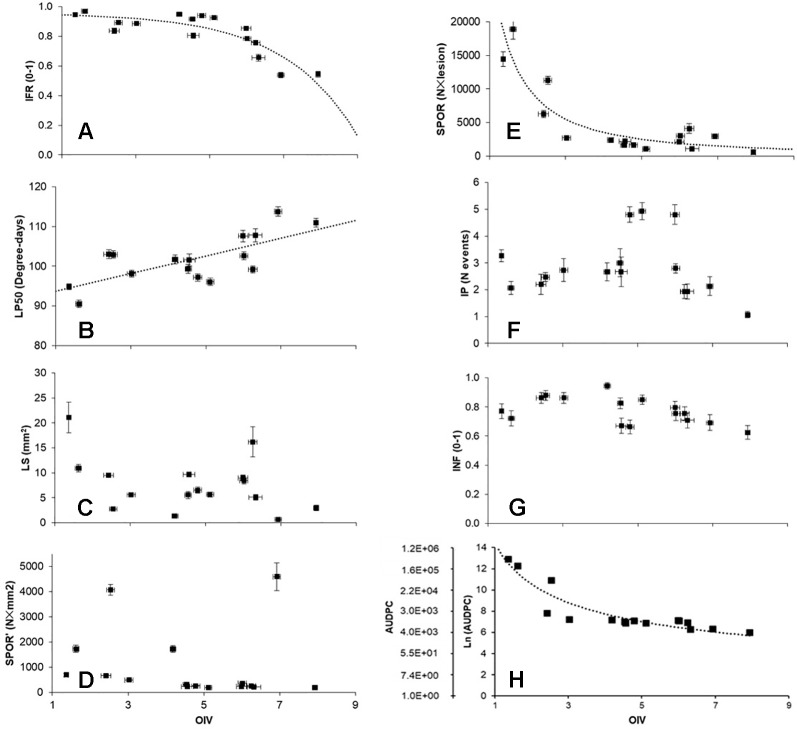

Relationships between OIV score and the seven RCs measured for the 16 grapevine varieties are shown in Figure 3 . OIV scores were significantly correlated with IFR (r = −0.759; P = 0.001), LP50 (r = 0.710; P = 0.002), and SPOR (r = −0.763; P = 0.001), so that when the OIV score increased (i.e., the resistance level increases), IFR and SPOR decreased, while LP50 increased ( Table 2 ). The relationship was linear for LP50 ( Figure 3B ), so that the latent period increased by 2.22 degree-days for each unit of the OIV score ( Table 3 , Equation 2). For the infection frequency, the relationship fit a monomolecular equation ( Table 3 , Equation 1); based on this equation, IFR decreased at very slow rate when the OIV score increased from 1 to 5, at higher rates when OIV rated 5 to 7, and at a very high rate when the OIV score was >7 ( Figure 3A ). Conversely, the relationship was hyperbolic and inversely proportional for the production of sporangia on DM lesions ( Table 3 , Equation 3); therefore, the sporulation decreased sharply when the OIV score ranged 1 to 3, and then it decreased at lower and reducing rates ( Figure 3E ).

Correlations between OIV score (see Figure 1), components of partial resistance (RCs) (panels A to G) measured for 16 grapevine varieties through artificial inoculation of Plasmopara viticola sporangia in leaf discs bioassays, and the area under disease progress curve (AUDPC) calculated by using the RCs and a simulation model (panel H). RCs are: infection frequency of sporangia (IFR; 0–1; panel A); latent period (LP50; degree-days; panel B); lesion size (LS; mm2; ;panel C); number of sporangia per mm2 lesion (SPOR’; panel D); number of sporangia per lesion (SPOR; panel E); infectious period (IP; number of sporulation events; panel F); infectivity of the sporangia produced on the varieties and inoculated on the susceptible ‘Merlot’ (INF; 0–1; panel G). For significant correlations ( Table 2 ), data were fit by the equations described in Table 3 (dotted lines).

Table 2

Coefficients of correlation (r) between the OIV score assigned as in Figure 1 and the components of partial resistance (RCs) to Plasmopara viticola measured for 16 grapevine varieties through artificial inoculation of P. viticola sporangia in leaf discs bioassays and the area under disease progress curve (AUDPC) calculated by using the RCs and a simulation model.

| RCs | AUDPC | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFR | LP50 | LS | SPOR’ | SPOR | IP | INF | |||

| OIV score | r | −0.759 | 0.710 | −0.759 | −0.759 | −0.759 | −0.759 | −0.759 | −0.759 |

| P-value | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

RCs are: IFR, infection frequency of sporangia (0-1); LP50, latent period (degree-days); LS, lesion size (mm2); SPOR’, number of sporangia per mm2 lesion; SPOR, number of sporangia per lesion; IP, infectious period (number of sporulation events; INF, infectivity of the sporangia produced on the varieties and inoculated on the susceptible ‘Merlot’ (0–1).

Table 3

Parameters and statistics of the regression equations used for fitting the relationship between the OIV score assigned as in Figure 1 (independent variable X), some components of partial resistance (RCs, dependent variable Y) to Plasmopara viticola measured for 16 grapevine varieties through artificial inoculation of P. viticola sporangia in leaf discs bioassays (specifically: IFR, infection frequency of sporangia, Equation 1; LP50, latent period, Equation 2; SPOR, number of sporangia per lesion, Equation 3) and the area under disease progress curve (AUDPC, depend variable Y) calculated by using the RCs and a simulation model (Equation 4).

| Equations | Estimated parameters | R2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | |||

| (1) | y = a − b × c(-X) | 0.960 | 0.008 | 0.601 | 0.763 |

| 0.053 a | 0.012 | 0.109 | |||

| (2) | y = a × X + b | 2.222 | 91.511 | – | 0.504 |

| 0.589 | 2.921 | ||||

| (3) | y = b × X(−a) | 1.537 | 29799.00 | – | 0.834 |

| 0.221 | 4662.48 | ||||

| (4) | y = b × X(−a) | 0.447 | 14.393 | – | 0.848 |

| 0.047 | 0.866 | ||||

No significant correlation was found between OIV score and LS (r = −0.393, P = 0.132), SPOR’ (r = −0.142, P = 0.601), IP (r = −0.101, P = 0.709), or INF (r = −0.470, P = 0.066) ( Table 2 ).

The correlation between OIV score and AUDPC was negative and significant (r = −0.633; P < 0.001; Table 2 ). The relationship between these two variables fits an inverse exponential function, with R2 = 0.989 ( Table 3 , Equation 4). Specifically, all the grape varieties with an OIV score between 3 and 9 showed similar epidemic patterns, with very low AUDPC values ( Figure 3H ).

Discussion

This paper shows a comparison between two phenotypic methods used to assess partial resistance to P. viticola in grapevine trough an in vitro bioassay with artificial inoculation of leaf discs. Leaf disc inoculation is a well-established method to obtain reliable data for assessing grape resistance to P. viticola and many studies have revealed its strong correlation with data from naturally or artificially infected plants in the field or in pots (Stein et al., 1985; Eibach et al., 1989; Staudt and Kassemeyer, 1995; Brown et al., 1999; Boso et al., 2006; Boso and Kassemeyer, 2008; Bellin et al., 2009).

The phenotypic response of leaves in these bioassays mainly focused on the sporulation severity, assessed by means of the OIV 452-1 (Eibach et al., 2007; Bellin et al., 2009; Deglene-Benbrahim et al., 2010; Peressotti et al., 2010; Calonnec et al., 2012; Foria et al., 2018). For instance, Deglene-Benbrahim et al. (2010) scored leaf discs based on the severity of sporulation (abundant, dense, sparse, weak or absent) and its distribution (equally distributed or in large, small or very small patches) at 6 dpi. In epidemiological terms, the assessment of sporulation by the OIV scale accounts for the infection efficiency of the sporangia in causing infection (and then in causing DM lesions), for the density of sporangiophores and sporangia on lesions, and, indirectly, for lesion size. Results of the present work show that the OIV score is correlated with the number of sporangia produced on a DM lesion (SPOR). Similarly, a strong correlation between the number of sporangia per spray-inoculated leaf disc and the OIV score was found by Calonnec et al. (2013) and the number of sporangia per unit of leaf area and a modified OIV score by Bellin et al. (2009). However, the present work shows that this relationship is nonlinear. In addition, the OIV score is not related to the number of sporangia produced per mm2 of DM lesion (SPOR’), which represents the real sporulation potential of P. viticola on leaf tissue. Therefore, the OIV scale does not represent adequately the quantitative differences in sporulation of resistant genotypes compared to a susceptible one (‘Merlot’ in this work). Concerning relevant periods of epidemics related to sporulation, the OIV score is linearly related to the time a DM lesion takes for starting to produce sporangia (i.e., the latent period, LP50), but it is not related to the time a lesion continues producing sporangia (i.e., the infectious period, IP), which is a key component for the development of polycyclic diseases in the vineyard, as DM is.

Vezzulli et al. (2018) found a significant correlation between OIV 452-1 score and DM severity on spray-inoculated leaf discs, and supplemented the OIV descriptor by introducing the disease severity score, according to OEPP/EPPO, as follows: 1, corresponding to a leaf disc with more than 40% of the area occupied by sporulation, at 6 dpi (i.e., disease severity, DS > 40%); 2, DS ranging from 30 to 40%; 3, DS 25 to 30%; 4, DS 20 to 25%; 5, DS 15 to 20%; 6, DS 10 to15%; 7, DS 5 to 10%; 8, DS 1 to 5%; 9, DS < 1%. In epidemiological terms, the assessment based on disease severity accounts for infection frequency and lesion size. In the present work, the OIV score was correlated with the IFR, which is a measure of the infection efficiency of P. viticola inoculum of leaves, but it is not correlated with the LS. In addition, the relationship between OIV score and IFR is not linear. Therefore, the OIV scale does not accurately reflect the ability of resistance to reduce the disease severity of DM. Finally, the OIV scale does not clearly reflect the ability of the sporangia produced on resistant plants to cause new infections, which is an important driver of DM development in natural epidemics.

The OIV 452-1 descriptor considers only some aspects of partial resistance, in a monocycle. This approach may be reductionist and does not adequately represent the ability of plant resistance to reduce the disease development under natural vineyard conditions. This is confirmed by the nonlinear relationship existing between the OIV score and the AUDPC of the varieties considered in the present work, as determined through using a simulation model for monocycle concatenation during DM epidemics. The simulation model enabled the exploration of each component of partial resistance and of its effect in slowing down epidemic development, alone or in combination with other RCs (Van der Plank, 1963). In a previous work (Bove, 2018), the infection frequency showed the strongest effect in reducing the disease development because it affects both primary and secondary infections. The number of sporangia produced per lesion also had a strong effect in slowing the disease progress because the higher number of propagules produced per lesion caused a higher basic infection rate (Rc) (Zadoks and Schein, 1979). Therefore, resistant varieties showing low IFR and SPOR in monocyclic bioassay have great potential for slowing down DM epidemics in the vineyard. Varieties showing a shorter IP compared to susceptible ones also reduce epidemic development, because the number of secondary infection cycles originating from a lesion is lower. Similarly, the varieties showing a longer latent period slow down DM epidemics because the time at which they start producing sporangia for new infections is delayed.

The low accuracy of the OIV scale in representing the real effect of a resistant variety on slowing down DM epidemics in the vineyard is also confirmed by some contrasting results of previous works. In some works, a relationship was found between resistance levels from visual observation of leaf disc in bioassays and from field assessments (Sotolář, 2007; Boso et al., 2014; Zyprian et al., 2016; Buonassisi et al., 2018; Foria et al., 2018; Vezzulli et al., 2018). In other works, no relationship was found and this was imputed to the inoculation of a single P. viticola strain, which may be not representative of a field population (Cadle-Davidson, 2008), or to high inoculum concentration and optimal environmental conditions of the leaf discs bioassay, which may lead to an underestimation of the resistance level with the OIV scale (Calonnec et al., 2013). In addition (or as an alternative) to these argumentations, the inconsistent relationship between the resistance level of a variety in the bioassay assessed through the OIV scale and in the vineyard may be due to the fact that monocyclic experiments (i.e., leaf disc bioassays) and the OIV scale do not account for all the effects of partial resistance on each infection cycle and in the concatenation of infection cycles during the season as well. It might be also considered that in this study a mixture of isolates collected from different varieties in multiple vineyards were used for artificial inoculation of different resistant grapevine accessions carrying different resistant loci. It is known that some DM isolates are more aggressive than others (Delmotte et al., 2014), and each specific isolate/accession pair may have a unique scenario in term of disease severity and RCs.

Based on the results of this study, the measurement of the components of partial resistance to P. viticola in grapevine varieties by means of monocyclic leaf disc bioassays, as well as their incorporation into a model able to simulate their effect on the polycyclic development of DM epidemics in vineyards represents an improved method for phenotyping resistance level. In addition, the measurement of resistance components is a quantitative method, which is not influenced by the subjective bias of qualitative methods, like the OIV descriptor, and this would reduce bias of phenotyping outcomes. Therefore, resistance component analysis meets all the criteria for efficient phenotyping tools needed to grapevine breeders for the selection of new resistant genotypes (Töpfer et al., 2011).

Data Availability Statement

Datasets are available on request: The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Ethics Statement

The authors declare that the present manuscript complies with the Ethical Rules of good scientific practice applicable for this Journal. The research does not involve humans or animals.

Author Contributions

FB and VR mainly contributed to the conception and the design of the study. TC contributed to the analysis of results. FB and VR wrote the first draft of the manuscript. TC and LB contributed to the critical analysis of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was supported by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7-2007-2013) under grant agreement no. 311775 project INNOVINE.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Ph.D. in Agro-Food System (Agrisystem) of the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore (Italy).

References

- Alleweldt G. (1980). The breeding of fungus- and phylloxera-resistant grapevine varieties. Proc. 3rd Int. Symp. Grape Breeding, Davis (California), 242-250. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Villaverde V., Voinesco F., Viret O., Spring J. L., Gindro K. (2011). The effectiveness of stilbenes in resistant Vitaceae: ultrastructural and biochemical events during Plasmopara viticola infection process. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 49 (3), 265–274. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.12.010 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson K. (2013). Which Winegrape Varieties are Grown Where? Vol. 670 (Adelaide, Australia: University of Adelaide Press; ). pp.670. 10.20851/winegrapes [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Azzimonti G., Lannou C., Sache I., Goyeau H. (2013). Components of quantitative resistance to leaf rust in wheat cultivars: diversity, variability and specificity. Plant Pathol. 62 (5), 970–981. 10.1111/ppa.12029 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bavaresco L., Eibach R. (1987). Investigations on the influence of N fertilizer on resistance to powdery mildew (Oidium tuckeri) downy mildew (Plasmopara viticola) and on phytoalexin synthesis in different grapevine varieties. Vitis 26, 192–200. [Google Scholar]

- Bavaresco L. (2019). Impact of grapevine breeding for disease resistance on the global wine industry. Acta Hortic. 7–14. 10.17660/actahortic.2019.1248.2 [CrossRef]

- Bellin D., Peressotti E., Merdinoglu D., Wiedemann-Merdinoglu S., Adam-Blondon A. F., Cipriani G., et al. (2009). Resistance to Plasmopara viticola in grapevine ’Bianca’is controlled by a major dominant gene causing localised necrosis at the infection site. Theor. Appl. Genet. 120 (1), 163–176. 10.1007/s00122-009-1167-2 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Blasi P., Blanc S., Wiedemann-Merdinoglu S., Prado E., Rühl E. H., Mestre P., et al. (2011). Construction of a reference linkage map of Vitis amurensis and genetic mapping of Rpv8, a locus conferring resistance to grapevine downy mildew. Theor. Appl. Genet. 123 (1), 43–53. 10.1007/s00122-011-1565-0 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Boso S., Kassemeyer H. H. (2008). Different susceptibility of European grapevine cultivars for downy mildew. Vitis 47, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Boso S., Martínez M. C., Unger S., Kassemeyer H. (2006). Evaluation of foliar resistance to downy mildew in different cv. Albariño clones. Vitis-Geilweilerhof 45 (1), 23. [Google Scholar]

- Boso S., Alonso-Villaverde V., Gago P., Santiago J. L., Martínez M. C. (2014). Susceptibility to downy mildew (Plasmopara viticola) of different Vitis varieties. Crop Prot. 63, 26–35. 10.1016/j.cropro.2014.04.018 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bouquet A. (1980). Vitis x Muscadinia hybridization: a new way in grape breeding for disease resistance in France, Proc. 3rd Int. Symp. Grape Breeding, Davis (California), 42-61. [Google Scholar]

- Bove F. (2018). “A modelling framework for grapevine downy mildew epidemics incorporating foliage-cluster relationships and host plant resistance,” in PhD Thesis, 205 Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Piacenza, Italy. http://hdl.handle.net/10280/57899.

- Brown M. V., Moore J. N., Fenn P., McNew R. W. (1999). Comparison of leaf disk, greenhouse, and field screening procedures for evaluation of grape seedlings for downy mildew resistance. HortScience 34 (2), 331–333. 10.21273/HORTSCI.34.2.331 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Buonassisi D., Cappellin L., Dolzani C., Velasco R., Peressotti E., Vezzulli S. (2018). Development of a novel phenotyping method to assess downy mildew symptoms on grapevine inflorescences. Sci. Hortic. 236, 79–89. 10.1016/j.scienta.2018.03.023 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Burlakoti R. R., Mergoum M., Kianian S. F., Adhikari T. B. (2010). Combining different resistance components enhances resistance to Fusarium head blight in spring wheat. Euphytica 172 (2), 197–205. 10.1007/s10681-009-0035-0 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cadle-Davidson L. (2008). Variation within and between Vitis spp. for foliar resistance to the downy mildew pathogen Plasmopara viticola. Plant Dis. 92 (11), 1577–1584. 10.1094/PDIS-92-11-1577 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Calonnec A., Wiedemann-Merdinoglu S., Deliere L., Cartolaro P., Schneider C., Delmotte F. (2012). The reliability of a leaf bioassays for predicting disease resistance on fruit. A. Case Study Grapevine Resist. S Downy Powdery Mildew Plant Pathol. 62, 533–544. 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2012.02667.x [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Calonnec A., Wiedemann-Merdinoglu S., Deliere L., Cartolaro P., Schneider C., Delmotte F. (2013). The reliability of leaf bioassays for predicting disease resistance on fruit: a case study on grapevine resistance to downy and powdery mildew. Plant Pathol. 62 (3), 533–544. 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2012.02667.x [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C. L., Madden L. V. (1990). Introduction to plant disease epidemiology (New York: John Wiley & Sons; ). [Google Scholar]

- Casagrande K., Falginella L., Castellarin S. D., Testolin R., Di Gaspero G. (2011). Defence responses in Rpv3-dependent resistance to grapevine downy mildew. Planta 234 (6), 1097–1109. 10.1007/s00425-011-1461-5 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Copyright © (2007). The American Phytopathological Society. All rights reserved.

- Dai G. H., Andary C., Mondolot-Cosson L., Boubals D. (1995). Involvement of phenolic compounds in the resistance of grapevine callus to downy mildew (Plasmopara viticola). Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 101 (5), 541–547. 10.1007/BF01874479 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Deglene-Benbrahim L., Wiedemann-Merdinoglu S., Merdinoglu D., Walter B. (2010). Evaluation of downy mildew resistance in grapevine by leaf disc bioassay with in vitro- and greenhouse-grown plants. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 61, 521–528. 10.5344/ajev.2010.10009 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Delmotte F., Mestre P., Schneider C., Kassemeyer H. H., Kozma P., Richart-Cervera S., et al. (2014). Rapid and multiregional adaptation to host partial resistance in a plant pathogenic oomycete: evidence from European populations of Plasmopara viticola, the causal agent of grapevine downy mildew. Infect. Genet. Evol. 27, 500–508. 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.10.017 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Di Gaspero G., Copetti D., Coleman C., Castellarin S. D., Eibach R., Kozma P., et al. (2012). Selective sweep at the Rpv3 locus during grapevine breeding for downy mildew resistance. Theor. Appl. Genet. 124 (2), 277–286. 10.1007/s00122-011-1703-8 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Eibach R., Diehl H., Alleweldt G. (1989). Investigations on the heritability of resistance to Oidium tuckeri, Plasmopara viticola and Botrytis cinerea in grapes. Vitis 28 (4), 209–228. [Google Scholar]

- Eibach R., Zyprian E., Welter L., Topfer R. (2007). The use of molecular markers for pyramiding resistance genes in grapevine breeding. Vitis-Geilweilerhof 46 (3), 120. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer B. M., Salakhutdinov I., Akkurt M., Eibach R., Edwards K. J., Töpfer R., et al. (2004). Quantitative trait locus analysis of fungal disease resistance factors on a molecular map of grapevine. Theor. Appl. Genet. 108 (3), 501–515. 10.1007/s00122-003-1445-3 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Foria S., Magris G., Morgante M., Di Gaspero G. (2018). The genetic background modulates the intensity of Rpv3-dependent downy mildew resistance in grapevine. Plant Breed. 137 (2), 220–228. 10.1111/pbr.12564 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gessler C., Pertot I., Perazzolli M. (2011). Plasmopara viticola: a review of knowledge on downy mildew of grapevine and effective disease management. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 50 (1), 3–44. 10.1111/pbr.12564 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gindro K., Pezet R., Viret O. (2003). Histological study of the responses of two Vitis vinifera cultivars (resistant and susceptible) to Plasmopara viticola infections. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 41 (9), 846–853. 10.1016/S0981-9428(03)00124-4 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gindro K., Spring J. L., Pezet R., Richter H., Viret O. (2006). Histological and biochemical criteria for objective and early selection of grapevine cultivars resistant to Plasmopara viticola . Vitis-Geilweilerhof 45 (4), 191. [Google Scholar]

- Golodriga, P.Ia. (1978). Culture de variétés de vigne polyrésistantes. Génétique et amélioration de la vigne. IIe Symposium International sur l’Amélioration de la Vigne, Bordeaux, 14-18 juin 1977, 183-188. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon S. G., Lipps P. E., Pratt R. C. (2006). Heritability and components of resistance to Cercospora zeae-maydis derived from maize inbred VO613Y. Phytopathology 96 (6), 593–598. 10.1094/PHYTO-96-0593 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Isee Systems, Inc. (2005). STELLA. System thinking for education and research. Lebanon N.H., USA: <https://www.iseesystems.com/>. [Google Scholar]

- Kortekamp A., Wind R., Zvprian E. (1997). The role of callose deposits during infection of two downy mildew-tolerant and two-susceptible Vitis cultivars. Vitis-Geilweilerhof 36, 103–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kortekamp A., Wind R., Zyprian E. (1998). Investigation of the interaction of Plasmopara viticola with susceptible and resistant grapevine cultivars / Untersuchungen zur Interaktion von Plasmopara viticola mit anfälligen und resistenten Rebsorten. Z. für Pflanzenkrankheiten Pflanzenschutz/J. Plant Dis. Prot., 105, 475–488. [Google Scholar]

- Kozma P. (2002). Goals and methods in grape resistance breeding in Hungary. Int. J. Hortic. Sci. 8, 1, 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Langcake P. (1981). Disease resistance of Vitis spp. and the production of the stress metabolites resveratrol, ε-viniferin, α-viniferin and pterostilbene. Physiol. Plant Pathol. 18 (2), 213–226. 10.1016/S0048-4059(81)80043-4 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz D. H., Eichhorn K. W., Bleiholder H., Klose R., Meier U., Weber E. (1995). Growth Stages of the Grapevine: phenological growth stages of the grapevine (Vitis vinifera L. ssp. vinifera)-Codes and descriptions according to the extended BBCH scale. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 1 (2), 100–103. 10.1111/j.1755-0238.1995.tb00085.x [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J., Liu C. (2015). “Grapevine breeding in China,” in Grapevine Breeding Programs for the Wine Industry. Ed. Reynolds A. (Cambridge, UK: Woodhead Publishing; ), 273–310. 10.1016/B978-1-78242-075-0.00012-0 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Marguerit E., Boury C., Manicki A., Donnart M., Butterlin G., Némorin A., et al. (2009). Genetic dissection of sex determinism, inflorescence morphology and downy mildew resistance in grapevine. Theor. Appl. Genet. 118 (7), 1261–1278. 10.1007/s00122-009-0979-4 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Marino R., Sevini F., Madini A., Vecchione A., Pertot I., Dalla Serra A., et al. (2003). QTL mapping for disease resistance and fruit quality in grape. Acta Hortic. 603, 527–533. 10.17660/ActaHortic.2003.603.69 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Merdinoglu D., Wiedeman-Merdinoglu S., Coste P., Dumas V., Haetty S., Butterlin G., et al. (2003). Genetic analysis of downy mildew resistance derived from Muscadinia rotundifolia. Acta Hortic. 603, 451–456 10.17660/ActaHortic.2003.603.57 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Millardet A. (1881). Notes sur les vignes américaines et opuscules divers sur le même sujet Ferret edn. (Feret: Bordeaux: ). [Google Scholar]

- Moreira F. M., Madini A., Marino R., Zulini L., Stefanini M., Velasco R., et al. (2011). Genetic linkage maps of two interspecific grape crosses (Vitis spp.) used to localize quantitative trait loci for downy mildew resistance. Tree Genet. Genomes 7 (1), 153–167. 10.1007/s11295-010-0322-x [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Munson T. V. (1909). Foundations of American Grape Culture. T.V. Munson Son Denison Texas pp, 252. 10.5962/bhl.title.55446 [CrossRef]

- Ochssner I., Hausmann L., Töpfer R. (2016). Rpv14, a new genetic source for Plasmopara viticola resistance conferred by Vitis cinerea. Vitis: J. Grapevine Res. 55 (2), 79–81. 10.5073/vitis.2016.55.79-81 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- OIV (2009). Descriptor list for grape varieties and Vitis species, 2nd ed O.I.V. (Off. Int. Vigne Vin), Paris, http://www.oiv.org. [Google Scholar]

- Olmo H. P. (1971). Vinifera Rotundifolia hybrids as wine grapes. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 22, 87–91. [Google Scholar]

- Parlevliet J. E. (1979). Components of resistance that reduce the rate of epidemic development. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 17 (1), 203–222. 10.1146/annurev.py.17.090179.001223 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Peressotti E., Wiedemann-Merdinoglu S., Delmotte F., Bellin D., Di Gaspero G., Testolin R., et al. (2010). Breakdown of resistance to grapevine downy mildew upon limited deployment of a resistant variety. BMC Plant Biol. 10 (1), 147. 10.1186/1471-2229-10-147 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pezet R., Gindro K., Viret O., Richter H. (2004). Effects of resveratrol, viniferins and pterostilbene on Plasmopara viticola zoospore mobility and disease development. Vitis-Geilweilerhof 43 (3), 145–148. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi V., Battilani P., Chiusa G., Giosuè S., Languasco L., Racca P. (1999). Components of rate-reducing resistance to Cercospora leaf spot in sugar beet: incubation length, infection efficiency, lesion size. J. Plant Pathol. 81, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi V., Battilani P., Chiusa G., Giosuè S., Languasco L., Racca P. (2000). Components of rate-reducing resistance to Cercospora leaf spot in sugar beet: conidiation length, spore yield. J. Plant Pathol. 82, 125–131. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi V., Caffi T., Salinari F. (2012). Helping farmers face the increasing complexity of decision-making for crop protection. Phytopathol. Mediterr., 51(3), 457–479. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Mora F. D., Saifert L., Zanghelini J., Assumpção W. T., Guginski-Piva C. A., Giacometti R., et al. (2017). Behavior of grape breeding lines with distinct resistance alleles to downy mildew (Plasmopara viticola). Crop Breed. Appl. Biotechnol. 17 (2), 141–149. 10.1590/1984-70332017v17n2a21 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Savary S., Zadoks J. C. (1989). Analyse des composantes de l’interaction hôte-parasite chez la rouille de l’arachide: 1. Définition et mesure des composantes de résistance. (Analysis of host-parasite interaction components in groundnut rust: 1. Definition and measurement of resistance components.) Oléagineux, 44(3), 163-174. [Google Scholar]

- Schwanck A. A., Savary S., Lepennetier A., Debaeke P., Vincourt P., Willocquet L. (2016). Predicting quantitative host plant resistance against phoma black stem in sunflower. Plant Pathol. 65 (8), 1366–1379. 10.1111/ppa.12512 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schwander F., Eibach R., Fechter I., Hausmann L., Zyprian E., Töpfer R. (2012). Rpv10: a new locus from the Asian Vitis gene pool for pyramiding downy mildew resistance loci in grapevine. Theor. Appl. Genet. 124 (1), 163–176. 10.1007/s00122-011-1695-4 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sotolář R. (2007). Comparison of grape seedlings population against downy mildew by using different provocation methods. Notulae Bot. Horti. Agrobot. Cluj. 35, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Staudt G., Kassemeyer H. H. (1995). Evaluation of downy mildew resistance in various accessions of wild Vitis species. Vitis 34 (4), 225–228. [Google Scholar]

- Stein U., Heintz C., Blaich R. (1985). The in vitro examination of grapevines regarding resistance to powdery and downy mildew. Z. Fuer. Pflanzenkrankheiten Pflanzenschutz (Germany FR). 92 (4), 355–369 [Google Scholar]

- Töpfer R., Hausmann L., Harst M., Maul E., Zyprian E., Eibach R. (2011). Fruit, Vegetable and Cereal Science and Biotechnology New Horizons for Grapevine Breeding. New Horizons grapevine Breed. 5, 79–100. [Google Scholar]

- Toffolatti S. L., Venturini G., Maffi D., Vercesi A. (2012). Phenotypic and histochemical traits of the interaction between Plasmopara viticola and resistant or susceptible grapevine varieties. BMC Plant Biol. 12 (1), 124. 10.1186/1471-2229-12-124 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Plank J. E. (1963). Plant diseases: epidemics and control. (New York: Academic Press Inc.). [Google Scholar]

- Venuti S., Copetti D., Foria S., Falginella L., Hoffmann S., Bellin D., et al. (2013). Historical introgression of the downy mildew resistance gene Rpv12 from the Asian species Vitis amurensis into grapevine varieties. PloS One 8 (4), e61228. 10.1371/journal.pone.0061228 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Vezzulli S., Vecchione A., Stefanini M., Zulini L. (2018). Downy mildew resistance evaluation in 28 grapevine hybrids promising for breeding programs in Trentino region (Italy). Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 150 (2), 485–495. 10.1007/s10658-017-1298-2 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Welter L. J., Göktürk-Baydar N., Akkurt M., Maul E., Eibach R., Töpfer R., et al. (2007). Genetic mapping and localization of quantitative trait loci affecting fungal disease resistance and leaf morphology in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L). Mol. Breed. 20 (4), 359–374. 10.1007/s11032-007-9097-7 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedemann-Merdinoglu S., Prado E., Coste P., Dumas V., Butterlin G., Bouquet A., et al. (2006). Genetic analysis of resistance to downy mildew from Muscadinia rotundifolia. In 9th International Conference on Grape Genetics and Breeding (Vol. 2, No. 06.07, p. 2006). [Google Scholar]

- Willocquet L., Lore J. S., Srinivasachary S., Savary S. (2011). Quantification of the components of resistance to rice sheath blight using a detached tiller test under controlled conditions. Plant Dis. 95 (12), 1507–1515. 10.1094/PDIS-01-11-0051 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y., Zhang Y., Yin L., Lu J. (2012). The mode of host resistance to Plasmopara viticola infection of grapevines. Phytopathology 102 (11), 1094–1101. 10.1094/PHYTO-02-12-0028-R [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zadoks J. C., Schein R. D. (1979). Epidemiology and Plant Disease Management (Oxford: Oxford University Press; ). [Google Scholar]

- Zadoks (1972). Modern concepts in disease resistance in cereals. The way ahead in plant breeding In Proceedings of Sixth Congress of Eucarpia (Lupton F.A.G.H. et al. eds.) 89–98. [Google Scholar]

- Zini E., Raffeiner M., Di Gaspero G., Eibach R., Grando M. S., Letschka T. (2015). Applying a defined set of molecular markers to improve selection of resistant grapevine accessions. In XI International Conference on Grapevine Breeding and Genetics 1082 (pp. 73-78). 10.17660/ActaHortic.2015.1082.9. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zyprian E., Ochßner I., Schwander F., Šimon S., Hausmann L., Bonow-Rex M., et al. (2016). Quantitative trait loci affecting pathogen resistance and ripening of grapevines. Mol. Genet. Genomics 291 (4), 1573–1594. 10.1007/s00438-016-1200-5 [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Articles from Frontiers in Plant Science are provided here courtesy of Frontiers Media SA

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.01559

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2019.01559/pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.3389/fpls.2019.01559

Article citations

Breeding new seedless table grapevines for a more sustainable viticulture in Mediterranean climate.

Front Plant Sci, 15:1379642, 05 Apr 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38645394 | PMCID: PMC11027070

A method for phenotypic evaluation of grapevine resistance in relation to phenological development.

Sci Rep, 14(1):915, 09 Jan 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38195696 | PMCID: PMC10776754

Effects of pathogen reproduction system on the evolutionary and epidemiological control provided by deployment strategies for two major resistance genes in agricultural landscapes.

Evol Appl, 17(1):e13627, 19 Dec 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38283600 | PMCID: PMC10810173

Plant Resistance Inducers Affect Multiple Epidemiological Components of Plasmopara viticola on Grapevine Leaves.

Plants (Basel), 12(16):2938, 14 Aug 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37631150 | PMCID: PMC10459891

Nanosheet-Facilitated Spray Delivery of dsRNAs Represents a Potential Tool to Control Rhizoctonia solani Infection.

Int J Mol Sci, 23(21):12922, 26 Oct 2022

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 36361711 | PMCID: PMC9657606

Go to all (13) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Components of partial resistance to Plasmopara viticola enable complete phenotypic characterization of grapevine varieties.

Sci Rep, 10(1):585, 17 Jan 2020

Cited by: 9 articles | PMID: 31953499 | PMCID: PMC6969139

Screening of Croatian Native Grapevine Varieties for Susceptibility to Plasmopara viticola Using Leaf Disc Bioassay, Chlorophyll Fluorescence, and Multispectral Imaging.

Plants (Basel), 10(4):661, 30 Mar 2021

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 33808401 | PMCID: PMC8067117

Phenotyping grapevine resistance to downy mildew: deep learning as a promising tool to assess sporulation and necrosis.

Plant Methods, 20(1):90, 13 Jun 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38872155 | PMCID: PMC11177444

Phenotyping for QTL identification: A case study of resistance to Plasmopara viticola and Erysiphe necator in grapevine.

Front Plant Sci, 13:930954, 11 Aug 2022

Cited by: 8 articles | PMID: 36035702 | PMCID: PMC9403010

Review Free full text in Europe PMC