Abstract

Free full text

World Health Organization declares global emergency: A review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19)

Abstract

An unprecedented outbreak of pneumonia of unknown aetiology in Wuhan City, Hubei province in China emerged in December 2019. A novel coronavirus was identified as the causative agent and was subsequently termed COVID-19 by the World Health Organization (WHO). Considered a relative of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), COVID-19 is caused by a betacoronavirus named SARS-CoV-2 that affects the lower respiratory tract and manifests as pneumonia in humans. Despite rigorous global containment and quarantine efforts, the incidence of COVID-19 continues to rise, with 90,870 laboratory-confirmed cases and over 3,000 deaths worldwide. In response to this global outbreak, we summarise the current state of knowledge surrounding COVID-19.

1. Introduction

On 31st December 2019, 27 cases of pneumonia of unknown aetiology were identified in Wuhan City, Hubei province in China [1]. Wuhan is the most populous city in central China with a population exceeding 11 million. These patients most notably presented with clinical symptoms of dry cough, dyspnea, fever, and bilateral lung infiltrates on imaging. Cases were all linked to Wuhan's Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, which trades in fish and a variety of live animal species including poultry, bats, marmots, and snakes [1]. The causative agent was identified from throat swab samples conducted by the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CCDC) on 7th January 2020, and was subsequently named Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The disease was named COVID-19 by the World Health Organization (WHO) [2].

To date, most SARS-CoV-2 infected patients have developed mild symptoms such as dry cough, sore throat, and fever. The majority of cases have spontaneously resolved. However, some have developed various fatal complications including organ failure, septic shock, pulmonary oedema, severe pneumonia, and Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) [3]. 54.3% of those infected with SARS-CoV-2 are male with a median age of 56 years. Notably, patients who required intensive care support were older and had multiple comorbidities including cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, endocrine, digestive, and respiratory disease. Those in intensive care were also more likely to report dyspnoea, dizziness, abdominal pain, and anorexia [4].

1.1. WHO global health emergency

On 30th January 2020, the WHO declared the Chinese outbreak of COVID-19 to be a Public Health Emergency of International Concern posing a high risk to countries with vulnerable health systems. The emergency committee have stated that the spread of COVID-19 may be interrupted by early detection, isolation, prompt treatment, and the implementation of a robust system to trace contacts [5]. Other strategic objectives include a means of ascertaining clinical severity, the extent of transmission, and optimising treatment options. A key goal is to minimise the economic impact of the virus and to counter misinformation on a global scale [5]. In light of this, various bodies have committed to making articles pertaining to COVID-19 immediately available via open access to support a unified global response [6].

1.2. Global response

Efforts aimed at deciphering the pathophysiology of COVID-19 have led to the EU mobilising a €10,000,000 research fund to “contribute to more efficient clinical management of patients infected with the virus, as well as public health preparedness and response” [7]. Regarding diagnostic testing, US-based companies such as Co-Diagnostics and the Novacyt's molecular diagnostics division Primerdesign have launched COVID-2019 testing kits for use in the research setting [8,9]. The United Kingdom (UK) government have also invested £20,000,000 to help develop a COVID-19 vaccine [10]. Additionally, the United States (US) have suspended all entry of immigrants and non-immigrants having travelled to high-risk zones with the intention of halting further viral spread [11]. Hong Kong has also suspended several public transport services across the border and many hospital workers and civil servants are currently on strike. Strikers are demanding that the border to mainland China be closed completely to prevent further COVID-19 transmission. However, Hong Kong authorities have resisted these requests, stating that “closing the border would go against advice from the WHO” [12]. In addition, growing fears regarding China's economy has led the Chinese central bank to invest ¥150 billion to support the stability of the currency market [13].

1.3. Confirmed UK cases and British response

As of 4th March 2020, a total of 16,659 tests for COVID-19 have been conducted across the UK. To date, 85 individuals have tested positive resulting in the UK public health risk for viral infection being raised from low to moderate [14]. To prevent transmission, the UK government are following direct guidelines from the Department of Health (DoH) for encountering overseas travellers with respiratory infections, particularly for those who have travelled to Wuhan [[15], [16], [17]]. The UK National Health Service (NHS) have stressed the importance of using Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), taking a thorough travel history, and escalating suspected cases immediately with a view to isolating patients. Any detected cases of COVID-19 should be transferred to an Airborne High Consequence Infectious Diseases (HCID) centre, including the two principal centres in England (the Royal Free Hospital in London and the Newcastle Royal Victoria Infirmary).

The DoH and UK Chief Medical Officers have also advised individuals having visited Wuhan and the Hubei Province in the last 14 days to remain indoors and to call NHS 111. This advice also applies to individuals having visited mainland China, Thailand, Japan, Republic of Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia, and Macau. The British Foreign and Commonwealth Office have advised British citizens to avoid all travels to the Hubei Province, and to avoid unnecessary travel to Mainland China [18]. More recently, 200 British citizens were quarantined following an evacuation flight from Wuhan on the 30 January 2020. All other flights arriving to the UK from Hubei Province have since been suspended [19]. However, in keeping with WHO recommendations, no travel restrictions have been placed on individuals having travelled to China within the last two weeks and are free to enter the UK.

1.4. Viral transmission and spread

There are currently few studies that define the pathophysiological characteristics of COVID-19, and there is great uncertainty regarding its mechanism of spread. Current knowledge is largely derived from similar coronaviruses, which are transmitted from human-to-human through respiratory fomites [20]. Typically, respiratory viruses are most contagious when a patient is symptomatic. However, there is an increasing body of evidence to suggest that human-to-human transmission may be occurring during the asymptomatic incubation period of COVID-19, which has been estimated to be between 2 and 10 days [[20], [21], [22]].

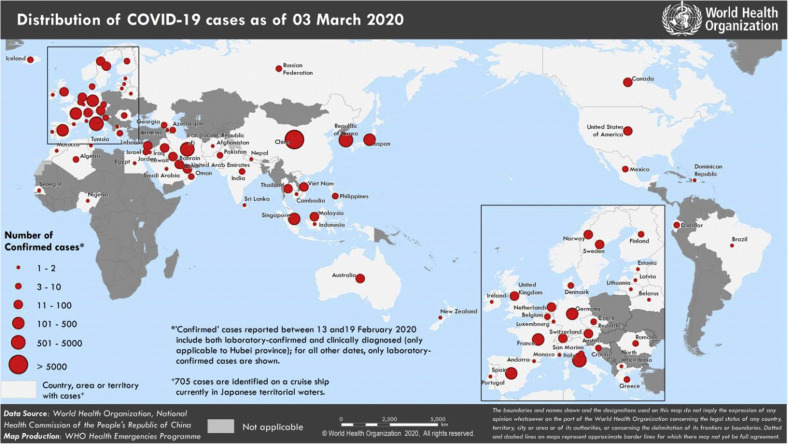

As of 3rd March 2020, 90,870 cases of COVID-19 have been confirmed, 80,304 of which are confined to China. Of the Chinese cases, 67,217 were confirmed in the Hubei Province with the remainder being reported in 34 provinces, regions and cities in China (Fig. 1 ) [23]. The remaining 10,566 cases were identified in 72 countries including Japan, the US, and Australia. 166 of these cases were fatal (the Philippines, Japan, Korea, Italy, France, Iran, Australia, Thailand, and the US). It is important to note that these figures are likely to be an underestimate, since the data presented depicts laboratory-confirmed diagnoses only.

1.5. Prevention

Various bodies including the WHO and US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have issued advice on preventing further spread of COVID-19 [20,24]. They recommend avoiding travel to high-risk areas, contact with individuals who are symptomatic, and the consumption of meat from regions with known COVID-19 outbreak. Basic hand hygiene measures are also recommended, including frequent hand washing and the use of PPE such as face masks. Japanese-based company Bespoke Inc has also launched an artificial intelligence-powered chatbot (Bebot) that provides up-to-date information regarding the coronavirus outbreak, preventative measures that can be taken, as well as a symptom checker [25].

1.6. Diagnosis

Clinical features of COVID-19 include dry cough, fever, diarrhoea, vomiting, and myalgia. Individuals with multiple comorbidities are prone to severe infection and may also present with acute kidney injury (AKI) and features of ARDS [3,26]. The WHO and CDC have both issued guidance on key clinical and epidemiological findings suggestive of a COVID-19 infection (Table 1 ) [27]. Extensive laboratory tests should be requested for patients with suspected infection. Patients may present with an elevated C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, lactate dehydrogenase, creatinine, and a prolonged prothrombin time [4].

Table 1

| CDC | WHO | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical features |

|

|

| Epidemiological Risk |

|

|

Full genome sequencing and phylogenetic analysis on fluid from bronchoalveolar lavage can confirm COVID-2019 infection [29]. Investigations for other respiratory pathogens should also be performed.

1.7. Treatment

At present, no effective antiviral treatment or vaccine is available for COVID-19. However, a randomized multicentre controlled clinical trial is currently underway to assess the efficacy and safety of abidole in patients with COVID-19 (ChiCTR2000029573). First-line treatment for fevers include antipyretic therapy such as paracetamol, whilst expectorants such as guaifenesin may be used for a non-productive cough [4]. Patients with severe acute respiratory infection, respiratory distress, hypoxaemia or shock require the administration of immediate oxygen therapy. This should be at 5 L/min to reach SpO2 targets of ≥90% in non-pregnant adults and children, and ≥92–95% in pregnant women [[30], [31], [32]]. In the absence of shock, intravenous fluids should be carefully administered [33]. Renal replacement therapy (RRT) should be initiated for patients with an AKI. Renal function and fluid balance should be used to identify patients that may require RRT [4]. Broad spectrum antibiotic therapy should also be administered within 1 hour of initial assessment for sepsis [34]. It is important to note that patients can develop further bacterial and fungal infections during the middle and latter stages of the disease. Therefore, conservative and rational antibiotic regimens must still be followed [35].

The National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China recommends the use of IFN-α and lopinavir/ritonavir. This advice is based on prior research showing that these medications lower mortality rates in patients infected with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) [36]. Oseltamivir, a neurominidase inhibitor, is currently being used by medical staff in China for suspected infections despite the lack of any conclusive evidence regarding its effectiveness on COVID-19. Glucocorticoids may also be considered for patients with severe immune reactions. In children, methylprednisolone should be limited to 1–2 mg/kg/day for a maximum of 5 days [4,35].

1.8. Prognosis

As of 3rd March 2020, a total of 3,112 deaths have been reported worldwide. Outside of China, 166 of these deaths have been reported in the Philippines, Japan, Korea, Italy, France, Iran, Australia, Thailand, and the US [23]. However, the number of positive cases and deaths continues to rise. The current reported mortality for COVID-19 is approximately 3.4% compared with 9.6% for SARS [37] and 34.4% for Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) [38]. The clinical features of COVID-19 versus its distance relative SARS are summarised in Table 2 . To date, COVID-19 has been shown to have a mean incubation period of 5.2 days and a median duration from the onset of symptoms to death of 14 days [22,39], which is comparable to that of MERS [40]. Patients ≥70 years of age have a shorter median duration (from the onset of initial symptoms to death) of 11.5 days, highlighting the vulnerability of this particular patient cohort.

Table 2

| SARS | COVID-19 | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical presentation | Fever Dry cough Shortness of breath | Fever Cough Shortness of breath |

| Incubation period | 2–7 days | 2–14 days |

| Number infected globally | 8096 | 90,870 |

| Deaths globally | 774 | 3,112 |

| Mortality | 9.6% | 3.4% |

1.9. Methods of containment

The epicentre in Wuhan is comprised of an urban area spanning 1,528 km2 and exceeds 11 million residents. This area was quarantined on 23rd January 2020. Subsequent viral spread led to the imposition of a cordon sanitaire, restricting movement across Hubei Province in 16 cities, affecting 50 million people [42]. All forms of public transportation including long-distance bus routes, metros, express railways, and aviation were uncompromisingly sealed off – a process facilitated by China's mega city-region infrastructure [43]. In addition, Chinese New Year celebrations were subdued amid an unprecedented national lockdown to prevent the amplification of viral spread [44]. Despite the implementation of restrictions on trade and trading routes representing an effective method of curbing viral spread [45], WHO recommendations continue to advise against the enforcement of restrictions to travel and trade [46].

To halt further viral spread, a ¥1 billion fund from China's Finance Ministry was used to facilitate the construction of two new hospitals in under two weeks in Wuhan [47]. Outside of China, aviation restrictions are being employed. In Europe, the Czech Republic, Greece, and Italy have recently suspended visa issuance and all air traffic from mainland China [48]. US airlines have also suspended flights until early spring [49]. Local exit screening conducted by healthcare professionals at airports is currently recommended by WHO [46], and multiple countries (Australia, Thailand, South Korea, Japan, India, Italy, and Singapore) have initiated temperature and symptom screening protocols [50]. Several countries (UK, US, and Australia) are also quarantining citizens having recently been evacuated from Wuhan [[51], [52], [53]]. Notably, significant concerns are currently focused towards Africa which may be least prepared should an outbreak ensue [46]. Evidently, an exponential increase in case count may dampen concerted containment efforts.

1.10. COVID-19 pathophysiology

COVID-19 is caused by SARS-CoV-2, a betacoronavirus. It is comprised of a single-stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA) structure that belongs to the Coronavirinae subfamily, part of the Coronaviridae family. Sequence analysis of SARS-CoV-2 has shown a structure typical to that of other coronaviruses (Fig. 2 ), and its genome has been likened to a previously identified coronavirus strain that caused the SARS outbreak in 2003 [54]. Structurally, the SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV) has a well-defined composition comprising 14 binding residues that directly interact with human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Of these amino acids, 8 have been conserved in SARS-CoV-2 [55]. In humans, coronaviruses were thought to cause mild respiratory infections until the identification of SARS-CoV and MERS coronavirus (MERS-CoV). Although the exact pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 are unknown (due to pending laboratory trials), genomic similarities to SARS-CoV could help to explain the resulting inflammatory response that may lead to the onset of severe pneumonia [55]. Until these laboratory trials are initiated, the precise mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 remains hypothetical.

1.11. The wider consequences of COVID-19

China is integral to nearly every sector of the global economy. As the world's most populous nation, China has already battled with viral epidemics, including the outbreak of SARS in 2003. At the time, however, China's gross domestic production was 4% of the global total – it is now 17% [57]. The recent outbreak of the COVID-19 has already challenged an economy strained by trade wars with the US; national growth hit a 30-year low in 2019 [58]. Provinces responsible for over 90% of Chinese exports have since ordered their factories to stay closed or to run at low capacity [59]. Moreover, China's position as the world's largest manufacturer [60] and importer of crude oil [61] has caused economists to nudge down their forecasts for full-year global growth. The key difference between COVID-19 and SARS however is the complexity of supply chains that China is now enmeshed in. There exists little historical evidence to provide guidance for the disruption of such supply chains as global reliance on them is a relatively new phenomenon.

1.12. Lessons learned from the COVID-19 outbreak

The international response to COVID-19 has been more transparent and efficient when compared to the SARS outbreak. However, several learning points should be taken away from COVID-19 in the event of future outbreaks (Table 3 ). Of particular note, it has been suggested that the Chinese central government may have issued viral response guidelines 13 days before the public were informed [62]. This may have delayed the implementation of containment strategies that could have dampened viral spread such as reporting suspected cases in public and the work place.

Table 3

A tabular presentation of lessons to be learned from the response to COVID-19.

| Issues with the current response | Event | Consequence | Key learning points |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of transparency | Intimidation of clinicians who initially identified COVID-19 | Delay in the release of information pertaining to COVID-19 cases | Establish clear whistleblowing policies for possible global health emergencies |

| Travel restriction delay | Aviation services operated for over a month following the initial outbreak with minimal health screening at international borders | Citizens travelling from high-risk areas were able to freely pass through large airports without health screening | Precautions such as screening citizens returning from high-risk countries should be implemented earlier |

| Quarantine delay | On 31st December 2019, the first report of COVID-19 was released. Wuhan began to quarantine on 23rd January 2020, nearly a month later | Allowed individuals potentially infected with COVID-19 to spread the infection both nationally and internationally | Quarantine high-risk areas as soon as a possible health threat is identified |

| Public misinformation | Lack of transparency allows rumours, speculation and misinformation to be spread amongst the public | Racism, incorrect public precautions, and unprecedented fear surrounding COVID-19 | Transparency and open access to all information is essential to avoid misinformation |

| Emergency announcement delay | Public Health Emergency of International Concern declared by WHO on 30th December 2019, a month following the initial outbreak | The severity of the outbreak was not widely broadcasted or acknowledged. This may have delayed containment measures | Framework should be developed for fast-spreading diseases in order to escalate a threat status earlier |

| Research and development | Lack of funding in initial stages of research and development of vaccine and treatment of COVID-19 | Over 3,000 patients worldwide have died due to COVID-19, and the death toll continues to rise weekly | Further investment is required to produce effective treatments and to establish robust methods to contain future outbreaks of communicable disease |

2. Conclusion

The recent COVID-19 outbreak has been deemed a global health emergency. Internationally, the number of confirmed reports has continued to rise, and is currently placed at 90,870 laboratory-confirmed cases with over 3,000 deaths. It is perhaps clear that quarantine alone may not be sufficient to prevent the spread of COVID-19, and the global impact of this viral infection is one of heightening concern. Further research is undoubtedly required to help define the exact mechanism of human-to-human and animal-to-human transmission to facilitate the development of a virus-specific vaccine. Evidently, the pandemic potential of COVID-19 demands rigorous surveillance and on-going monitoring to accurately track and potentially predict its future host adaptation, evolution, transmissibility, and pathogenicity. These factors will ultimately influence mortality rates and prognosis. However, the rapidly evolving nature of the COVID-2019 epidemic, ever changing statistics, and constant unravelling of new research findings represents a major limitation to the present review. Nevertheless, as a surgical community, it is also our responsibility to be aware of the aforementioned signs and symptoms and to promptly escalate suspected cases.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Data statement

The data in this review is not sensitive in nature and is accessible in the public domain. The data is therefore available and not of a confidential nature.

Ethical approval

No ethical approval required.

Sources of funding

No funding received.

Author contribution

CS, ZA, NO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Resources, Writing original draft, Editing drafts, Approval of final article. MK, AK, AA, CI, RA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Resources, Writing original draft, Approval of final article.

Research registration number

Not relevant.

Guarantor

Niamh O'Neill – Corresponding Author [email protected].

Riaz Agha – Senior Author [email protected].

Declaration of competing interest

No conflicts of interest to declare.

References

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

Reported Adverse Events and Associated Factors in Korean Coronavirus Disease 2019 Vaccinations.

J Korean Med Sci, 39(42):e274, 04 Nov 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39497564 | PMCID: PMC11538574

Environmental Stress-Induced Alterations in Embryo Developmental Morphokinetics.

J Xenobiot, 14(4):1613-1637, 21 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39449428 | PMCID: PMC11503402

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Investigation of the Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic Period on Respiratory Tract Viruses at Istanbul Medical Faculty Hospital, Turkey.

Infect Dis Rep, 16(5):992-1004, 10 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39452164 | PMCID: PMC11507061

Healthcare use among cancer survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic: results from the SHARE COVID-19 Survey.

Support Care Cancer, 32(11):718, 10 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39387931 | PMCID: PMC11467033

Silent Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Parental Attachment in Pediatric Patients.

Cureus, 16(10):e70937, 06 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39372383 | PMCID: PMC11456311

Go to all (2,132) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

The novel zoonotic COVID-19 pandemic: An expected global health concern.

J Infect Dev Ctries, 14(3):254-264, 31 Mar 2020

Cited by: 102 articles | PMID: 32235085

The outbreak of the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): A review of the current global status.

J Infect Public Health, 13(11):1601-1610, 04 Aug 2020

Cited by: 80 articles | PMID: 32778421 | PMCID: PMC7402212

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Occupational health responses to COVID-19: What lessons can we learn from SARS?

J Occup Health, 62(1):e12128, 01 Jan 2020

Cited by: 29 articles | PMID: 32515882 | PMCID: PMC7221300

Recent progress and challenges in drug development against COVID-19 coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) - an update on the status.

Infect Genet Evol, 83:104327, 19 Apr 2020

Cited by: 161 articles | PMID: 32320825 | PMCID: PMC7166307

Review Free full text in Europe PMC