Abstract

Free full text

Rationale for Prolonged Corticosteroid Treatment in the Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Caused by Coronavirus Disease 2019

CORONAVIRUS DISEASE 2019 ASSOCIATED ACUTE RESPIRATORY DISTRESS SYNDROME

In December 2019, pneumonia associated with the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) emerged in Wuhan, China. On March 14, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the coronavirus outbreak a pandemic with confirmed cases in 127 countries. This unprecedented load on healthcare institutions is particularly overwhelming for ICUs and medical personnel treating mechanically ventilated patients. The occurrence rate of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) with COVID-19 infection varied between 17% and 41% (1–3). ARDS may require weeks of mechanical ventilation (MV) and is associated with an unacceptably high mortality rate. Worldwide, thousands of patients are denied life-saving support for lack of mechanical ventilators. This is unprecedented global emergency without a workable solution. Thus, any intervention directed at decreasing duration of MV and mortality could have a great impact on public health and national security.

PROLONGED CORTICOSTEROID TREATMENT IN NONVIRAL ARDS

Corticosteroids have been off patent for greater than 20 years, they are cheap and globally equitable. Since the first clinical description of ARDS (4), corticosteroids are the most broadly used medication specifically targeted at treatment. Translational research has established a strong association between dysregulated systemic inflammation and progression (maladaptive repair) or delayed resolution of ARDS. In patients with ARDS, glucocorticoid receptor-mediated down-regulation of systemic and pulmonary inflammation is essential to restore tissue homeostasis and accelerate resolution of diffuse alveolar damage and extrapulmonary organ dysfunction. This can be significantly enhanced with prolonged low-to-moderate dose corticosteroid treatment (CST) (5). The recent publication of a large confirmatory trial (6) provides stronger evidence that prolonged low-to-moderate dose CST is effective and safe for nonviral ARDS (mostly caused by bacterial pneumonia and sepsis).

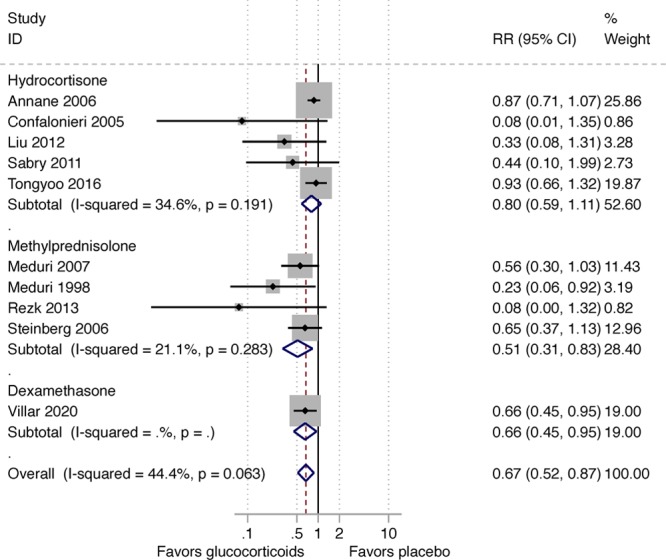

In 2017, the Corticosteroid Guideline Task Force of the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) released guidelines for CST in critically ill patients including those with ARDS (5). The analysis to support the Task Force’s recommendations was limited to nine randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that investigated methylprednisolone (n = 322) (7) and hydrocortisone (n = 494) treatment in ARDS for a duration of at least 7 days. The Task Force found moderate quality/certainty of evidence for a reduction in the duration of MV (mean difference, 7.1 d; 95% CI, 3.2–10.9 d) and improved survival (relative risk, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.46–0.89) and therefore made a conditional recommendation for methylprednisolone treatment (5). The high benefit/risk (therapeutic index) associated with the intervention supported their recommendation. Except for transient hyperglycemia (mostly within the 36 hr following an initial bolus), CST was not associated with increased risk for neuromuscular weakness, gastrointestinal bleeding, or nosocomial infections (very low certainty evidence) (5). Importantly, the survival benefit observed during hospitalization persisted after hospital discharge with follow-up observations extending up to 60 days (6, 8, 9), 4 months (10), 6 months (11), or 1 year (limit of measurement) (12). However, most trials were less than 100 patients and performed before the implementation of lung-protective MV. A larger confirmatory RCT in patients receiving low tidal volume (LTV) ventilation was missing.

hr following an initial bolus), CST was not associated with increased risk for neuromuscular weakness, gastrointestinal bleeding, or nosocomial infections (very low certainty evidence) (5). Importantly, the survival benefit observed during hospitalization persisted after hospital discharge with follow-up observations extending up to 60 days (6, 8, 9), 4 months (10), 6 months (11), or 1 year (limit of measurement) (12). However, most trials were less than 100 patients and performed before the implementation of lung-protective MV. A larger confirmatory RCT in patients receiving low tidal volume (LTV) ventilation was missing.

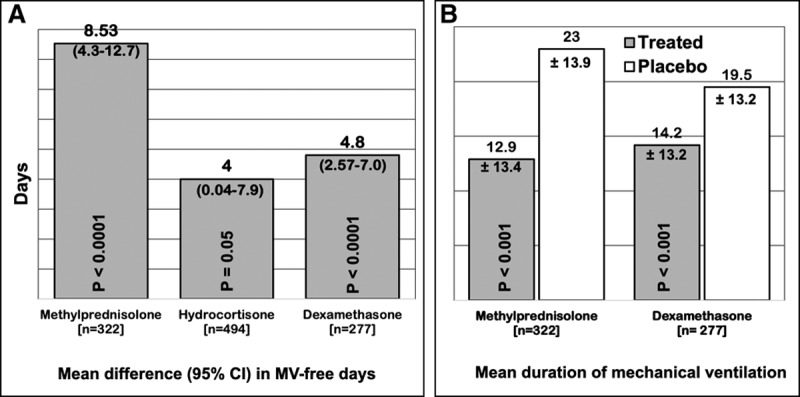

Clinical investigators in Spain recently completed a large confirmatory RCT (Efficacy Study of Dexamethasone to Treat the Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome [DEXA-ARDS]) enrolling 277 patients with moderate-to-severe ARDS and receiving LTV ventilation (6). Early administration of dexamethasone for 10 days led to a significant reduction in duration of MV (mean difference, 5.9 d; 95% CIs, 2.7–9.1 d) and all-cause mortality (mean difference, 15.3%; 95% CIs, 4.9–25.9%), without increasing rate of complications. This latest RCT provided consistent evidence similar to what was observed in the previous meta-analyses. The aggregate data from 10 RCTs (n = 1,093) clearly demonstrate that CST is associated with a sizable reduction in duration of MV and hospital mortality. Figures Figures11 and 22 show the impact of prolonged CST on reduction of ventilator dependence and hospital mortality (number needed to save one life is seven). Canadian investigators are working on an updated meta-analysis.

Randomized trials investigating prolonged corticosteroid treatment (CST) in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (n = 1,093): impact (treated vs control) on (a) duration ventilator dependence and ventilator-free days. Data obtained from prior meta-analysis (randomized controlled trials [RCTs] 9; n = 816) used for the Corticosteroid Guideline Task Force of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine released guidelines for CST in critically ill patients including those with ARDS (5), with the addition of the new DEXA-ARDS RCT (n = 277) (6). A, Mean difference and 95% CI for increase in mechanical ventilation (MV)-free days by day 28 (7). The reduction in duration of MV in the four RCTs investigating methylprednisolone treatments was strikingly similar (methylprednisolone vs control: 10.4 ± 19.2 vs 20.2 ± 26.6, p = 0.051; 10.6 ± 2.9 vs 21.2 ± 2.2, p < 0.001; 18.6 ± 24.4 vs 27.3 ± 26.6, p = 0.43; and 27.3 ± 26.6 vs 14.1 ± 1.7, p = 0.006) (7). B, Mean (sd) difference in methylprednisolone treatment versus control (–10.10; –13.12 to 7.08; p < 0.001) and dexamethasone versus control (–5.3; –8.4 to –2.2; p = 0.0009).

SUPPORTING ARGUMENTS FOR CONSIDERING USE OF CORTICOSTEROID TREATMENT IN COVID-19 ARDS

Dysregulated Systemic Inflammation (Cytokine Storm) and CST

The dysregulated inflammation and coagulation observed in COVID-19 (13) is similar to that of multifactorial medical ARDS, where ample evidence has demonstrated the ability of prolonged CST to down-regulate inflammation-coagulation-fibroproliferation and accelerate disease resolution (14). Additionally, the CT findings of ground-glass opacities (15) and the histological findings of hyaline membrane and inflammatory exudates (16) are compatible with corticosteroid-responsive inflammatory lung disease. A recent study (2) showed that COVID-19 is associated with a cytokine elevation profile that is reminiscent of secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, a condition responsive to CST.

The WHO statement (17) of not recommending the routine use of corticosteroids for treatment of viral pneumonia outside clinical trials relies on incomplete evidence. If the evidence favors the use of corticosteroids in nonviral ARDS, why does the WHO not recommend CST for COVID-19-associated ARDS? There are limitations on the evidence approach used by WHO to reach a categorical decision with potentially serious public health repercussions. The WHO’s brief argument to support the recommendation is mainly based on the risk of decreased viral clearance reported in one observational study (18) and inconclusive evidence from retrospective observational studies without a predesigned study protocol and subjected to cofounding (imbalances in baseline characteristics and postbaseline time-dependent patient differences that influence the decision to prescribe corticosteroids), and hidden bias (19). A more recent high-quality meta-analysis found a high correlation between CST and potential confounders for measured outcomes, such as disease severity and comorbid illnesses. Therefore, confounding by indication is likely to be a significant bias in studies which only provided unadjusted effect estimates. Additionally, time to hospitalization, antiviral use, presence of respiratory failure prior to corticosteroids, and the rationale for corticosteroid use or treatment regimen were sparsely reported across studies (20). What “kills” COVID-19 patients is dysregulated systemic inflammation. There is no evidence linking delayed viral clearance to worsened outcome in critically ill COVID-19 patients, and it is unlikely that it would have a greater negative impact than the host own “cytokine storm” (13).

In a recent commentary regarding the use of corticosteroids in contemporary severe viral epidemics (such as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, or influenza), coauthored by a member of the WHO panel on clinical management for 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), it states that there are “conclusive data” to expect that patients with COVID-19 ARDS will not benefit from corticosteroids (21). This interpretation is biased and without evidence-based support (22). First, their “conclusive” statement rested on only four small studies without including results from another 25 publications (19). Six of the 10 studies in the referenced meta-analysis did not describe the CST used (23). Second, they ignored the positive findings of two large studies (5,327 patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome [SARS] [24] and 2,141 patients with influenza H1N1 pneumonia [25]) that evaluated the impact of time, dose, and duration of CST and reported a significant reduction in mortality with dosage and duration similar to the one recommended by SCCM and ESICM Task Force (5). In the SARS study, after adjustment for possible confounders, CST was safe and decreased the risk for death by 47% (hazard ratio [HR], 0.53; 95% CI, 0.35–0.82) (24). In the H1N1 study, 1,055 patients received corticosteroids and 1,086 did not receive it. Subgroup analysis among patients with Pao2/Fio2 less than 300 mm Hg (535 vs 462

mm Hg (535 vs 462 mm Hg), low-to-moderate-dose CST significantly reduced both 30-day mortality (adjusted HR [aHR], 0.49; 95% CI, 0.32–0.77) and 60-day mortality (aHR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.33–0.78) (25).

mm Hg), low-to-moderate-dose CST significantly reduced both 30-day mortality (adjusted HR [aHR], 0.49; 95% CI, 0.32–0.77) and 60-day mortality (aHR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.33–0.78) (25).

Early Evidence and Recommendations From Those on the Frontline in China and Italy

Early evidence from few observational studies on COVID-19 ARDS is available. In a recent report in 84 COVID-19 patients with ARDS from a single center in Wuhan, China, the administration of methylprednisolone (dosage similar to protocol recommended by the SCCM and ESICM Task Force [5]) was associated with reduced risk of death (HR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.20–0.72; p = 0.003) (3). In a letter to Lancet “On the use of corticosteroids for 2019-nCoV pneumonia,” Shang et al (22) provide a compelling argument from intensivists in the frontline of the outbreak in China that deserves consideration. The letter includes a summary of the expert consensus statement on the use of corticosteroids in 2019-nCoV pneumonia from the Chinese Thoracic Society. Finally, the Italian National Institute for the Infectious Diseases “L. Spallanzani” released updated recommendations for COVID-19 clinical management that included the use of methylprednisolone or dexamethasone for COVID-19-associated ARDS (26).

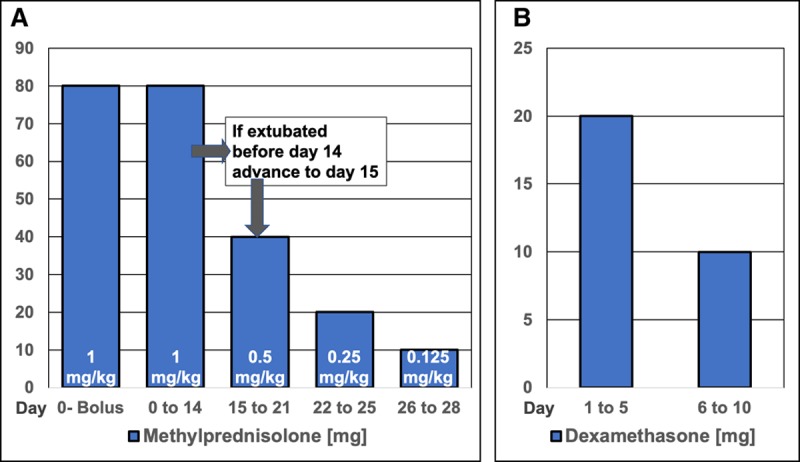

In conclusion, this is a critical moment for the world, in which even industrially advanced countries have rapidly reached ICU saturation and intensivists are forced to make difficult ethical decisions that are uncommon outside war zones. Although there is a wide divergence of opinion in the literature on whether corticosteroids should be used in patients with COVID-19, the two largest studies on H1N1 and SARS (n = 7,568) (25, 27) lend support to its use. However, the lack of sufficient evidence is not tantamount with negating the plausible efficacy of corticosteroids in COVID-19-associated ARDS. The stronger evidence for nonviral ARDS, the early reports from China, and the recommendations from the frontlines of China and Italy should be considered. Inconclusive clinical evidence should not be a reason for abandoning CST in COVID-19-associated ARDS. RCTs are in progress (NCT04273321, NCT04244591, NCT04325061, and NCT04323592) and results will not be available for months. Until then, there is no justification based on available evidence and professional ethics to categorically deny the use of CST in severe life-threatening “cytokine storm” associated with COVID-19 in hospitals not involved in a RCT. Figure Figure33 shows the protocols most commonly used in patients with nonviral ARDS RCTs.

Corticosteroid treatment protocols: methylprednisolone and dexamethasone. A, Methylprednisolone treatment. The dosage is adjusted to ideal body weight and round up to the nearest 10 mg (i.e., 77

mg (i.e., 77 mg round up to 80

mg round up to 80 mg). Day 0, IV bolus (80

mg). Day 0, IV bolus (80 mg in 50 cc normal saline) over 30

mg in 50 cc normal saline) over 30 min. Day 0-to ICU discharge: infusion is obtained by adding the daily dosage to 240 cc of normal saline and run at 10 cc/hr. If necessary, infusion can be changed to bolus every 6

min. Day 0-to ICU discharge: infusion is obtained by adding the daily dosage to 240 cc of normal saline and run at 10 cc/hr. If necessary, infusion can be changed to bolus every 6 hr (1/4 daily dose) or in the last 6 d very 12

hr (1/4 daily dose) or in the last 6 d very 12 hr (1/2 daily dose). Five days after the patient can ingest medications, methylprednisolone is administered orally in one single daily equivalent dose. Enteral absorption of methylprednisolone, and likely other corticosteroids, is compromised for days after extubation. If between days 1 to 14, the patient is extubated, the patient is advanced to day 15 of drug therapy and tapered according to schedule. Monitor anti-inflammatory response with daily measurements of C-reactive protein levels in addition to severity scores of acute respiratory distress syndrome and multiple organ dysfunction. Rapid tapering can be associated with reconstituted systemic inflammation in the presence of suppressed adrenal function with worsening lung physiology and increased mortality risk (28). Urgent reinstitution of corticosteroid treatment is necessary to be followed after improvement by slow tapering. B, Dexamethasone treatment. Patients in the dexamethasone group received an IV dose of 20

hr (1/2 daily dose). Five days after the patient can ingest medications, methylprednisolone is administered orally in one single daily equivalent dose. Enteral absorption of methylprednisolone, and likely other corticosteroids, is compromised for days after extubation. If between days 1 to 14, the patient is extubated, the patient is advanced to day 15 of drug therapy and tapered according to schedule. Monitor anti-inflammatory response with daily measurements of C-reactive protein levels in addition to severity scores of acute respiratory distress syndrome and multiple organ dysfunction. Rapid tapering can be associated with reconstituted systemic inflammation in the presence of suppressed adrenal function with worsening lung physiology and increased mortality risk (28). Urgent reinstitution of corticosteroid treatment is necessary to be followed after improvement by slow tapering. B, Dexamethasone treatment. Patients in the dexamethasone group received an IV dose of 20 mg once daily from day 1 to day 5, which was reduced to 10

mg once daily from day 1 to day 5, which was reduced to 10 mg once daily from day 6 to day 10. Treatment was maintained for a maximum of 10 d after randomization or until extubation (if occurring before day 10). An updated protocol mandates to give dexamethasone for a maximum of 10 d after randomization, independently of the intubation status. This protocol does not mandate further tapering for few days to minimize the risk for reconstituted systemic inflammation.

mg once daily from day 6 to day 10. Treatment was maintained for a maximum of 10 d after randomization or until extubation (if occurring before day 10). An updated protocol mandates to give dexamethasone for a maximum of 10 d after randomization, independently of the intubation status. This protocol does not mandate further tapering for few days to minimize the risk for reconstituted systemic inflammation.

Footnotes

The contents of this commentary do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. Government.

This material is the result of work supported with the resources and use of facilities at the Memphis VA Medical Center.

Dr. Villar is funded by grants from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain (CB06/06/1088, PI16/0049), the European Regional Development’s Funds, and the Asociación Científica Pulmón y Ventilación Mecánica. Canary Islands, Spain. Dr. Meduri received support for article research from the Veteran Administration. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

Articles from Critical Care Explorations are provided here courtesy of Wolters Kluwer Health

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

The Efficacy of Oral/Intravenous Corticosteroid Use in COVID-19 Patients: A Systematic Review.

J Exp Pharmacol, 16:321-337, 01 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39371262 | PMCID: PMC11453156

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Outpatient glucocorticoid use and COVID-19 outcomes: a population-based study.

Inflammopharmacology, 32(4):2305-2315, 02 May 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38698179 | PMCID: PMC11300658

The analysis of low-dose glucocorticoid maintenance therapy in patients with primary nephrotic syndrome suffering from COVID-19.

Front Mol Biosci, 10:1326111, 11 Jan 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38274101 | PMCID: PMC10808412

American Association for the Surgery of Trauma/American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma clinical protocol for management of acute respiratory distress syndrome and severe hypoxemia.

J Trauma Acute Care Surg, 95(4):592-602, 12 Jun 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 37314843 | PMCID: PMC10545067

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Screening for Femoral Head Osteonecrosis Following COVID-19: Is It Worth It?

Arch Bone Jt Surg, 11(12):731-737, 01 Jan 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38146516 | PMCID: PMC10748811

Go to all (68) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Recovery from COVID-19 and acute respiratory distress syndrome: the potential role of an intensive care unit recovery clinic: a case report.

J Med Case Rep, 14(1):161, 10 Sep 2020

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 32912329 | PMCID: PMC7481550

Adherence to Lung Protective Ventilation in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019.

Crit Care Explor, 3(8):e0512, 10 Aug 2021

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 34396146 | PMCID: PMC8357244

Corticosteroid Administration Is Associated With Improved Outcome in Patients With Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2-Related Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome.

Crit Care Explor, 2(6):e0143, 15 Jun 2020

Cited by: 7 articles | PMID: 32696006 | PMCID: PMC7314336

Role of corticosteroids in the management of acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Clin Ther, 30(5):787-799, 01 May 2008

Cited by: 16 articles | PMID: 18555927

Review

6,,7

6,,7