Abstract

Objective

Postacute COVID-19 syndrome (PACS) is an emerging entity characterised by a large array of manifestations, including musculoskeletal complaints, fatigue and cognitive or sleep disturbances. Since similar symptoms are present also in patients with fibromyalgia (FM), we decided to perform a web-based cross-sectional survey aimed at investigating the prevalence and predictors of FM in patients who recovered from COVID-19.Methods

Data were anonymously collected between 5 and 18 April 2021. The collection form consisted of 28 questions gathering demographic information, features and duration of acute COVID-19, comorbid diseases, and other individual's attributes such as height and weight. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Survey Criteria and the Italian version of the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire completed the survey.Results

A final sample of 616 individuals (77.4% women) filled the form 6±3 months after the COVID-19 diagnosis. Of these, 189 (30.7%) satisfied the ACR survey criteria for FM (56.6% women). A multivariate logistic regression model including demographic and clinical factors showed that male gender (OR: 9.95, 95% CI 6.02 to 16.43, p<0.0001) and obesity (OR: 41.20, 95% CI 18.00 to 98.88, p<0.0001) were the strongest predictors of being classified as having post-COVID-19 FM. Hospital admission rate was significantly higher in men (15.8% vs 9.2%, p=0.001) and obese (19.2 vs 10.8%, p=0.016) respondents.Conclusion

Our data suggest that clinical features of FM are common in patients who recovered from COVID-19 and that obesity and male gender affect the risk of developing post-COVID-19 FM.Free full text

Original research

Fibromyalgia: a new facet of the post-COVID-19 syndrome spectrum? Results from a web-based survey

Abstract

Objective

Postacute COVID-19 syndrome (PACS) is an emerging entity characterised by a large array of manifestations, including musculoskeletal complaints, fatigue and cognitive or sleep disturbances. Since similar symptoms are present also in patients with fibromyalgia (FM), we decided to perform a web-based cross-sectional survey aimed at investigating the prevalence and predictors of FM in patients who recovered from COVID-19.

Methods

Data were anonymously collected between 5 and 18 April 2021. The collection form consisted of 28 questions gathering demographic information, features and duration of acute COVID-19, comorbid diseases, and other individual’s attributes such as height and weight. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Survey Criteria and the Italian version of the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire completed the survey.

Results

A final sample of 616 individuals (77.4% women) filled the form 6±3 months after the COVID-19 diagnosis. Of these, 189 (30.7%) satisfied the ACR survey criteria for FM (56.6% women). A multivariate logistic regression model including demographic and clinical factors showed that male gender (OR: 9.95, 95% CI 6.02 to 16.43, p<0.0001) and obesity (OR: 41.20, 95%

CI 6.02 to 16.43, p<0.0001) and obesity (OR: 41.20, 95% CI 18.00 to 98.88, p<0.0001) were the strongest predictors of being classified as having post-COVID-19 FM. Hospital admission rate was significantly higher in men (15.8% vs 9.2%, p=0.001) and obese (19.2 vs 10.8%, p=0.016) respondents.

CI 18.00 to 98.88, p<0.0001) were the strongest predictors of being classified as having post-COVID-19 FM. Hospital admission rate was significantly higher in men (15.8% vs 9.2%, p=0.001) and obese (19.2 vs 10.8%, p=0.016) respondents.

Conclusion

Our data suggest that clinical features of FM are common in patients who recovered from COVID-19 and that obesity and male gender affect the risk of developing post-COVID-19 FM.

Introduction

Since its first appearance in December 2019, SARS-CoV-2—the pathogen responsible for COVID-19)—exhibited all its devasting potential,1 causing more than three million deaths worldwide. Apart from the clinical manifestations of the acute disease, the long-term consequences of COVID-19 are emerging as a new, overwhelming challenge for clinicians and healthcare systems. A postacute COVID-19 syndrome (PACS)2 is now clearly recognised and, in the near future, is expected to impose a serious burden on different medical specialties, given the pleiotropic nature of its clinical manifestations. Of note, musculoskeletal pain—the cardinal symptoms of fibromyalgia (FM), reported in one-third of patients with acute COVID-193—is part of the complex spectrum of PACS, along with pulmonary, cardiovascular, haematological, renal, gastroenteric, dermatological, endocrine and neuropsychiatric sequelae.2

million deaths worldwide. Apart from the clinical manifestations of the acute disease, the long-term consequences of COVID-19 are emerging as a new, overwhelming challenge for clinicians and healthcare systems. A postacute COVID-19 syndrome (PACS)2 is now clearly recognised and, in the near future, is expected to impose a serious burden on different medical specialties, given the pleiotropic nature of its clinical manifestations. Of note, musculoskeletal pain—the cardinal symptoms of fibromyalgia (FM), reported in one-third of patients with acute COVID-193—is part of the complex spectrum of PACS, along with pulmonary, cardiovascular, haematological, renal, gastroenteric, dermatological, endocrine and neuropsychiatric sequelae.2

The diagnosis of FM historically relied on the 1990 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria,4 including widespread pain of at least 3 months’ duration and tenderness on pressure at 11 or more of 18 specific tender points. In 2010, the ACR proposed a new set of clinical criteria for the diagnosis of FM based on a Widespread Pain Index (WPI) and a Symptom Severity (SS) scale; however, the tender point examination was withdrawn.5 The 2010 criteria underwent a revision in 20166 that combined physician and questionnaire criteria and eliminated the previous recommendation regarding diagnostic exclusions. Furthermore, the ACR 2010 criteria have also been adapted for administration as a self-report questionnaire (‘survey’ criteria) to be used in epidemiological studies with good reliability and convergent and discriminant validity.7

The pathogenesis of FM is still far to be fully understood. Pain augmentation/dysperception seems associated with exquisite neuromorphological modifications and imbalance between pronociceptive and antinociceptive pathways arising from an intricate interplay between genetic predisposition, stressful life events, psychological characteristics and emerging peripheral mechanisms, such as small fibre neuropathy or neuroinflammation.8 Strikingly, a role for infectious triggers—viral infections, in particular—has been also postulated.9

Internet-based surveys have gained growing popularity in the past years among healthcare researchers because of their clear advantages, such as the ability to reach a large pool of potential participants within a short period of time and to involve subjects that may be geographically dispersed or otherwise may be difficult to access; this is in conjugation with other practical reasons, such as the inexpensiveness and the easiness of data extraction, management and analysis.10 The emergence of COVID-19 even emphasised the use of web-based surveys, and more than 2000 records can now be retrieved on PubMed when applying the search string “COVID-19” AND “online survey”.

On this basis, here we report the results of a web-based survey aimed at investigating the prevalence of FM developed after symptomatic COVID-19; the secondary aim was to investigate predictive factors of post-COVID-19 FM syndrome development.

Methods

Design of the study

The present study was carried out as a web-based cross-sectional survey. Data were collected between 5 and 18 April 2021 through an online form built using the Google Forms platform.11 Google Forms is a free survey administration tool that has been largely used in medical research.11 Reporting was compliant with the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Survey.12

FM classification and assessment

To define the presence of FM in survey respondents, the ACR survey criteria13—developed as a modification of the ACR 2010 criteria to be used as a self-administration tool—were applied after linguistic validation as detailed in online supplemental methods. FM survey criteria have been successfully applied in web-based survey research.14 A Fibromyalgianess Scale or Fibromyalgia Symptom Scale (FS) is obtained by summing up the modified WPI and SS scores. An FS score of ≥13 has been largely adopted as the best cut-off for FM classification.13 The FS can be also used as a continuous measure of symptom burden.13 To quantify FM severity, the Italian version of the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ-I)15 was used. FIQ-I was modified by excluding one question (item 3, ‘work missed’, and item 4, ‘do work’) expressly recalling a past FM diagnosis. The overall score was adjusted to account for the reduced number of questions according to the suggestion for managing non-responses to individual questions.

Supplementary data

Survey development

A group of senior researchers (FU, RM and LM), including a medical psychotherapist (LL), designed the survey draft. The content was further reviewed by all study researchers. Pilot testing investigating the understandability of questions and technical usability was performed on a pool of healthy individuals (n=20) and patients with post-COVID-19 (n=20) who did not participate in developing the survey. The final version was consequently modified following their suggestions and was approved by consensus. The survey was found to require a total of 10 min to be completed. Results were transmitted to the database only if the participant clicked on ‘survey completed’ at the end of the questionnaire. Questions were listed in the same order for all participants. The survey could not be submitted unless all mandatory questions were completed.

min to be completed. Results were transmitted to the database only if the participant clicked on ‘survey completed’ at the end of the questionnaire. Questions were listed in the same order for all participants. The survey could not be submitted unless all mandatory questions were completed.

Survey structure

The survey consisted of a single page including a total of 28 questions. Questions were preceded by a preface stating the overall goal of the survey, information on how to contact the research group and that collected data could be anonymously used for research purposes and publication. Details of the survey structure are reported in online supplemental table S1.

Briefly, a first part of the survey (Q1–Q14) was used to collect demographic characteristics, marital and occupational status, symptoms and duration of acute COVID-19, comorbid diseases and other individual characteristics such as height and weight.

A second part of the survey (Q15–Q19) was dedicated to the ACR Survey Criteria for FM.13 Finally, the third and last parts of the survey (Q20–Q28) contained the FIQ-I.15

Target population and survey administration

The target population comprised adult individuals (≥18 years) who developed COVID-19 3 or more months before the survey publication. To reach this population, members of the research group combined several lines of contact, mainly based on social network (Facebook and Instragram) interactions as detailed in online supplemental methods. No monetary or non-monetary incentives were offered for the voluntary completion of the survey. One follow-up reminder message was sent 1 week apart to all direct contacts; however, participants were explicitly asked to answer the survey only once.

week apart to all direct contacts; however, participants were explicitly asked to answer the survey only once.

Ethical considerations

By voluntarily taking part in the survey, each participant explicitly authorised the use of the anonymous data recorded in the questionnaire for research purposes and their publication, as clearly stated in the questionnaire preface.16

Statistical analysis

A sample size of at least 457 patients was needed to estimate a prevalence of 2%–5% with precision set at 0.02 and confidence level set at 0.95. A sample size of at least 385 patients was needed to estimate a prevalence of 10%–50% with precision set at 0.05 and confidence level set at 0.95.

Data are expressed as mean±SD, median (25th–75th percentiles) or number (percentage) as appropriate.

Poststratification weighting was used to adjust for self-selection bias as previously suggested.17 Weighting is a family of techniques that allow improvement of the accuracy of survey estimates by using auxiliary information, that is, a set of variables (eg, age and gender) that have been measured in the survey, and for which the value for the population is available. By comparing the response distribution of an auxiliary variable, it can be extrapolated whether or not the sample is representative for the whole population. If these distributions differ considerably, adjustment weights are computed and assigned to all records in order to align the representation of various subpopulation groups to match that of the known population. The weight is calculated as the ratio between the population (N) and the sample (n) proportion for the auxiliary variable: W=N/n. The weight variable is created for each record of the data table and applied in analysis using the ‘weight cases’ function of the statistical analysis software.

Student’s t-test was used for comparing means of continuous variables between groups; highly skewed variables were ln-transformed before the analysis. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were built to assess the predictivity of continuous or categorical variables for a dichotomic dependent variable, expressed as OR and 95% CI.

All tests were two tailed. Analyses were performed using the Statistic Package for Social Sciences software V.23 (IBM).

Results

General features of the survey respondents

A total of 937 individuals (76.7% women) completed the survey form. Of these, 321 were excluded from the analysis for different reasons: 37 did not report a diagnosis of COVID-19 confirmed by a physician; 61 did not perform a nasopharyngeal swab or reported a negative result; 23 had a pre-existent diagnosis of FM; 12 declared a history of chronic musculoskeletal pain and 188 did not meet the symptom duration criteria (≥3 months) for FM classification. The final cohort comprised 616 patients. General characteristics of the population are reported in table 1. Most patients (77.4%) were women with a mean age of 45±12 years; median COVID-19 duration was 13 days with 10.7% of patients requiring hospital admission. The most common pre-existent comorbid diseases were anxiety (17.5%), obesity (16.6%), high blood pressure (15.7%), chronic pulmonary diseases (8.4%), depression (5.8%) and inflammatory arthritides (4.9%). Comparison between our cohort and official data released from the Italian Ministry of Health18 describing the cumulative Italian population of patients with COVID-19 showed a major difference in gender distribution (women: 77.4% vs 51.1%); to account for this potential source of self-selection bias, poststratification weights were assigned to each gender (weight for female gender=0.66, weight for male gender=1.99), and weighted values for all variables were calculated (table 1).

Table 1

General characteristics of the study population

| Overall (n=616) | Weight-adjusted (n*=591) | |

| Age (years) | 45±12 | 45±12 |

| Female gender, n (%) | 477 (77.4) | – |

| Marital status | ||

Single, n (%) Single, n (%) | 116 (18.8) | 126 (21.3) |

Married, n (%) Married, n (%) | 437 (70.9) | 417 (70.6) |

Separated, n (%) Separated, n (%) | 51 (8.3) | 39 (6.6) |

Widowed, n (%) Widowed, n (%) | 12 (1.9) | 9 (1.6) |

| Employment status | ||

Student, n (%) Student, n (%) | 29 (4.7) | 35 (5.9) |

Employed, n (%) Employed, n (%) | 494 (80.2) | 469 (79.4) |

Unemployed, n (%) Unemployed, n (%) | 66 (10.7) | 56 (9.4) |

Retired, n (%) Retired, n (%) | 27 (4.4) | 31 (5.3) |

| COVID-19 symptoms | ||

Fever, n (%) Fever, n (%) | 429 (69.6) | 421 (71.3) |

Cough, n (%) Cough, n (%) | 292 (47.4) | 282 (47.7) |

Dyspnoea, n (%) Dyspnoea, n (%) | 237 (38.5) | 225 (38.1) |

Headache, n (%) Headache, n (%) | 390 (63.3) | 352 (59.5) |

Myalgia, n (%) Myalgia, n (%) | 436 (70.8) | 398 (67.3) |

Arthralgia, n (%) Arthralgia, n (%) | 404 (65.6) | 358 (60.6) |

Anosmia or ageusia, n (%) Anosmia or ageusia, n (%) | 437 (70.9) | 399 (67.4) |

Abdominal pain, n (%) Abdominal pain, n (%) | 229 (37.2) | 198 (33.5) |

| Treatment setting | ||

No treatment, n (%) No treatment, n (%) | 165 (26.8) | 165 (27.9) |

Home treatment, n (%) Home treatment, n (%) | 375 (60.9) | 342 (57.8) |

Hospital admission, n (%) Hospital admission, n (%) | 66 (10.7) | 73 (12.3) |

ICU admission, n (%) ICU admission, n (%) | 10 (1.6) | 12 (2.0) |

| COVID-19 duration (days) | 13 (7–20) | 10 (7–20) |

| COVID-19 treatment | ||

Analgesics/NSAIDs, n (%) Analgesics/NSAIDs, n (%) | 422 (68.5) | 401 (67.8) |

LMWH, n (%) LMWH, n (%) | 131 (21.3) | 132 (22.3) |

Hydroxychloroquine, n (%) Hydroxychloroquine, n (%) | 53 (8.6) | 48 (8.2) |

Supplemental oxygen, n (%) Supplemental oxygen, n (%) | 66 (10.7) | 69 (11.6) |

| Pre-existent comorbid diseases | ||

Rheumatoid arthritis or other inflammatory arthritides, n (%) Rheumatoid arthritis or other inflammatory arthritides, n (%) | 30 (4.9) | 24 (4.0) |

Connective tissue diseases, n (%) Connective tissue diseases, n (%) | 3 (0.5) | 2 (0.3) |

Anxiety, n (%) Anxiety, n (%) | 108 (17.5) | 104 (17.7) |

Depression, n (%) Depression, n (%) | 30 (5.8) | 37 (6.3) |

Diabetes, n (%) Diabetes, n (%) | 10 (1.6) | 9 (1.6) |

High blood pressure, n (%) High blood pressure, n (%) | 97 (15.7) | 101 (17.1) |

Chronic pulmonary diseases, n (%) Chronic pulmonary diseases, n (%) | 52 (8.4) | 46 (7.8) |

History of myocardial infarction, n (%) History of myocardial infarction, n (%) | 3 (0.5) | 5 (0.8) |

History of stroke, n (%) History of stroke, n (%) | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) |

Other neurological diseases, n (%) Other neurological diseases, n (%) | 3 (0.5) | 2 (0.3) |

Malignancy, n (%) Malignancy, n (%) | 5 (0.8) | 5 (0.8) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.3±4.8 | 25.6±4.7 |

| BMI category | ||

Underweight, n (%) Underweight, n (%) | 19 (3.1) | 14 (2.3) |

Normal weight, n (%) Normal weight, n (%) | 335 (54.4) | 302 (51.1) |

Overweight, n (%) Overweight, n (%) | 160 (26.0) | 172 (29.1) |

Obese, n (%) Obese, n (%) | 102 (16.6) | 103 (17.5) |

| FM (FS score ≥13), n (%) | 189 (30.7) | 234 (39.5) |

| Additional symptoms | ||

Constipation, n (%) Constipation, n (%) | 68 (11) | 71 (12.1) |

Diarrhoea, n (%) Diarrhoea, n (%) | 69 (11.2) | 76 (12.9) |

Nausea, n (%) Nausea, n (%) | 61 (9.9) | 61 (10.4) |

Heartburn, n (%) Heartburn, n (%) | 90 (14.6) | 105 (17.7) |

Pain in upper abdomen, n (%) Pain in upper abdomen, n (%) | 108 (17.5) | 127 (21.5) |

Numbness and tingling in arms, n (%) Numbness and tingling in arms, n (%) | 228 (37) | 241 (40.7) |

Dizziness or vertigo, n (%) Dizziness or vertigo, n (%) | 177 (27.1) | 183 (31.0) |

Insomnia, n (%) Insomnia, n (%) | 199 (32.3) | 223 (37.7) |

Chest pain, n (%) Chest pain, n (%) | 121 (19.6) | 130 (22.0) |

Blurred vision, n (%) Blurred vision, n (%) | 163 (26.5) | 175 (29.7) |

Fever, n (%) Fever, n (%) | 151 (24.5) | 158 (26.7) |

Dry eyes, n (%) Dry eyes, n (%) | 154 (25.0) | 163 (27.5) |

Diffuse itching, n (%) Diffuse itching, n (%) | 124 (20.1) | 128 (21.7) |

Excessive sweating, n (%) Excessive sweating, n (%) | 108 (17.5) | 116 (19.7) |

Ringing in ear, n (%) Ringing in ear, n (%) | 123 (20.0) | 126 (21.4) |

Change in smell and/or taste, n (%) Change in smell and/or taste, n (%) | 157 (25.5) | 167 (28.3) |

Shortness of breath, n (%) Shortness of breath, n (%) | 270 (43.8) | 284 (48.1) |

Loss of appetite, n (%) Loss of appetite, n (%) | 57 (9.3) | 65 (11.1) |

Hair loss, n (%) Hair loss, n (%) | 156 (25.3) | 165 (28) |

Frequent or painful urination, n (%) Frequent or painful urination, n (%) | 98 (15.9) | 103 (17.5) |

*Corresponding to the imputed total number of respondents calculated on the basis of gender-based weights.

BMI, body mass index; FM, fibromyalgia; FS, Fibromyalgia Symptom Scale; ICU, intensive care unit; LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Prevalence of FM after COVID-19 and comparison between respondents with FM and without FM

A total of 189 individuals (30.7%) fulfilled the criteria for FM classification after an average of 6±3 months from COVID-19 diagnosis (table 1). Of these, a total of 79 patients have contracted COVID-19 during the first pandemic wave (February–April 2020) and 491 during the second wave (October 2020–January 2021); prevalence of FM was 39.2% (31 cases) and 28.9% (142 cases), respectively (p=0.066). The remaining 46 got COVID-19 in between the two waves.

Respondents with FM were predominantly women (56.6%), admitted to hospital more frequently than counterparts without FM (19.0% vs 7.0%, p<0.0001) and reported significantly higher proportions of cough (52.9% vs 45.0%, p=0.046) and dyspnoea (45.5% vs 35.4%, p=0.017) during acute COVID-19 (table 2). Accordingly, a higher proportion of patients with FM were treated with supplemental oxygen (18.0% vs 7.5%, p<0.0001). The body mass index (BMI) was significantly higher in patients with FM (30.4±4.4 kg/m2 vs 23.0±2.9 kg/m2, p<0.0001) as well as the proportion of obese individuals (49.2% vs 2.1%, p<0.0001). Furthermore, among self-reported pre-existent comorbidities, high blood pressure was significantly more common in individuals with FM (27.0% vs 10.8%, p<0.0001).

kg/m2, p<0.0001) as well as the proportion of obese individuals (49.2% vs 2.1%, p<0.0001). Furthermore, among self-reported pre-existent comorbidities, high blood pressure was significantly more common in individuals with FM (27.0% vs 10.8%, p<0.0001).

Table 2

Comparison between respondents with and without FM

| FM (n=189) | No FM (n=427) | P value | Weighted P value | |

| Age (years) | 46±11 | 44±12 | 0.312 | 0.04 |

| Female gender, n (%) | 107 (56.6) | 370 (86.7) | <0.0001 | – |

| Marital status | ||||

Single, n (%) Single, n (%) | 37 (19.6) | 79 (18.5) | 0.739 | 1.000 |

Married, n (%) Married, n (%) | 137 (72.5) | 300 (70.3) | 0.631 | 0.519 |

Separated, n (%) Separated, n (%) | 12 (6.3) | 39 (9.1) | 0.271 | 0.848 |

Widowed, n (%) Widowed, n (%) | 3 (1.6) | 9 (2.1) | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Employment status | ||||

Student, n (%) Student, n (%) | 4 (2.1) | 25 (5.9) | 0.061 | 0.019 |

Employed, n (%) Employed, n (%) | 158 (83.6) | 336 (78.7) | 0.188 | 0.047 |

Unemployed, n (%) Unemployed, n (%) | 17 (9.0) | 49 (11.5) | 0.399 | 0.059 |

Retired, n (%) Retired, n (%) | 10 (5.3) | 17 (4.0) | 0.523 | 0.187 |

| COVID-19 symptoms | ||||

Fever, n (%) Fever, n (%) | 128 (67.7) | 301 (70.5) | 0.491 | 0.746 |

Cough, n (%) Cough, n (%) | 100 (52.9) | 192 (45.0) | 0.069 | 0.046 |

Dyspnoea, n (%) Dyspnoea, n (%) | 86 (45.5) | 151 (35.4) | 0.017 | 0.001 |

Headache, n (%) Headache, n (%) | 112 (59.3) | 278 (65.1) | 0.165 | 0.108 |

Myalgia, n (%) Myalgia, n (%) | 133 (70.4) | 303 (71.0) | 0.882 | 0.749 |

Arthralgia, n (%) Arthralgia, n (%) | 122 (64.6) | 282 (66.0) | 0.719 | 0.246 |

Anosmia or ageusia, n (%) Anosmia or ageusia, n (%) | 134 (70.9) | 303 (71.0) | 0.988 | 0.352 |

Abdominal pain, n (%) Abdominal pain, n (%) | 71 (37.6) | 158 (37.1) | 0.910 | 0.696 |

| Treatment setting | ||||

No treatment, n (%) No treatment, n (%) | 45 (23.8) | 120 (28.1) | 0.279 | 0.019 |

Home treatment, n (%) Home treatment, n (%) | 103 (54.5) | 272 (63.7) | 0.032 | 0.233 |

Hospital admission, n (%) Hospital admission, n (%) | 36 (19.0) | 30 (7.0) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

ICU admission, n (%) ICU admission, n (%) | 5 (2.6) | 5 (1.2) | 0.185 | 0.234 |

| COVID-19 duration (days) | 14 (7–21) | 12 (7–20) | 0.424 | 0.820 |

| COVID-19 treatment | ||||

Analgesics/NSAIDs, n (%) Analgesics/NSAIDs, n (%) | 131 (69.3) | 291 (68.1) | 0.755 | 0.364 |

LMWH, n (%) LMWH, n (%) | 58 (30.7) | 73 (17.1) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

Hydroxychloroquine, n (%) Hydroxychloroquine, n (%) | 22 (11.6) | 31 (7.3) | 0.074 | 0.029 |

Supplemental oxygen, n (%) Supplemental oxygen, n (%) | 34 (18) | 32 (7.5) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Pre-existent comorbid diseases | ||||

Rheumatoid arthritis or other inflammatory arthritides, n (%) Rheumatoid arthritis or other inflammatory arthritides, n (%) | 7 (3.7) | 23 (5.4) | 0.371 | 0.294 |

Connective tissue diseases, n (%) Connective tissue diseases, n (%) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.7) | 0.248 | 0.251 |

Anxiety, n (%) Anxiety, n (%) | 37 (19.6) | 71 (16.6) | 0.375 | 0.198 |

Depression, n (%) Depression, n (%) | 11 (5.8) | 25 (5.9) | 0.986 | 0.414 |

Diabetes, n (%) Diabetes, n (%) | 3 (1.6) | 7 (1.6) | 0.962 | 0.706 |

High blood pressure, n (%) High blood pressure, n (%) | 51 (27) | 46 (10.8) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

Chronic pulmonary diseases, n (%) Chronic pulmonary diseases, n (%) | 16 (8.5) | 36 (8.4) | 0.989 | 0.575 |

History of myocardial infarction, n (%) History of myocardial infarction, n (%) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) | 0.920 | 0.983 |

History of stroke, n (%) History of stroke, n (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.5) | 0.346 | 0.418 |

Other neurological diseases, n (%) Other neurological diseases, n (%) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) | 0.920 | 0.763 |

Malignancy, n (%) Malignancy, n (%) | 2 (1.1) | 3 (0.7) | 0.650 | 0.349 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.4±4.4 | 23±2.9 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| BMI category | ||||

Underweight, n (%) Underweight, n (%) | 0 (0) | 19 (4.4) | 0.001 | 0.001 |

Normal weight, n (%) Normal weight, n (%) | 19 (10.1) | 316 (74) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

Overweight, n (%) Overweight, n (%) | 77 (40.7) | 83 (19.4) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

Obese, n (%) Obese, n (%) | 93 (49.2) | 9 (2.1) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

P values <0.05 are highlighted in bold.

BMI, body mass index; FM, fibromyalgia; ICU, intensive care unit; LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

To explore the possible role of COVID-19 severity in FM symptom burden, we compared the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) scores obtained from patients with FM who were admitted to the hospital versus those who were not and from patients treated with supplemental oxygen versus those who were not (online supplemental table S2). No significant differences, except for a slightly lower FIQ–stiffness score in patients treated with oxygen were observed.

Predictors of FM after COVID-19

In an attempt to identify factors associated with FM development, we performed correlation and regression analyses to ascertain potential predictors among demographic, anthropometric and COVID-19-related variables. After gender-based poststratification weighting, the FS score (table 3) was positively correlated with BMI (R=0.763, p<0.0001).

Table 3

Univariate correlation between FS score and other continuous variables with poststratification weights applied

| FS score | ||

| R | P value | |

| Age (years) | 0.028 | 0.742 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.763 | <0.0001 |

| Time since COVID-19 (months) | 0.068 | 0.423 |

| ln-COVID-19 duration (days) | 0.054 | 0.523 |

P values <0.05 are highlighted in bold.

BMI, body mass index; FS, Fibromyalgia Symptom Scale.

Further, variables obtaining a p value of <0.10 in the comparative analysis reported in table 2 were entered in univariate and multivariate logistic regression models with poststratification weights applied. Results of the logistic regression analyses are shown in table 4. Age (OR: 1.015, 95% CI 1.001 to 1.029, p=0.036), male gender (OR: 4.975, 95%

CI 1.001 to 1.029, p=0.036), male gender (OR: 4.975, 95% CI 3.332 to 7.426, p<0.0001), cough (OR: 1.397, 95%

CI 3.332 to 7.426, p<0.0001), cough (OR: 1.397, 95% CI 1.003 to 1.945, p=0.048), dyspnoea (OR: 1.786, 95%

CI 1.003 to 1.945, p=0.048), dyspnoea (OR: 1.786, 95% CI 1.272 to 2.506, p=0.001), intensity of treatment setting (OR: 1.727, 95%

CI 1.272 to 2.506, p=0.001), intensity of treatment setting (OR: 1.727, 95% CI 1.344 to 2.218, p<0.001), treatment with antibiotics (OR: 1.440, 95%

CI 1.344 to 2.218, p<0.001), treatment with antibiotics (OR: 1.440, 95% CI 1.033 to 2.008, p=0.031), LMWH (OR: 2.180, 95%

CI 1.033 to 2.008, p=0.031), LMWH (OR: 2.180, 95% CI 1.472 to 3.229, p<0.0001), supplemental oxygen (OR: 2.531, 95%

CI 1.472 to 3.229, p<0.0001), supplemental oxygen (OR: 2.531, 95% CI 1.514 to 4.229, p<0.0001), high blood pressure (OR: 3.061, 95%

CI 1.514 to 4.229, p<0.0001), high blood pressure (OR: 3.061, 95% CI 1.964 to 4.770, p<0.0001) and obesity (OR: 41.192, 95%

CI 1.964 to 4.770, p<0.0001) and obesity (OR: 41.192, 95% CI 18.003 to 98.879, p<0.0001) significantly predicted the fulfilment of FM criteria. In a multivariate model including all the aforementioned variables, only male gender (OR: 9.951, 95%

CI 18.003 to 98.879, p<0.0001) significantly predicted the fulfilment of FM criteria. In a multivariate model including all the aforementioned variables, only male gender (OR: 9.951, 95% CI 6.025 to 16.435, p<0.0001) and obesity (OR: 82.823, 95%

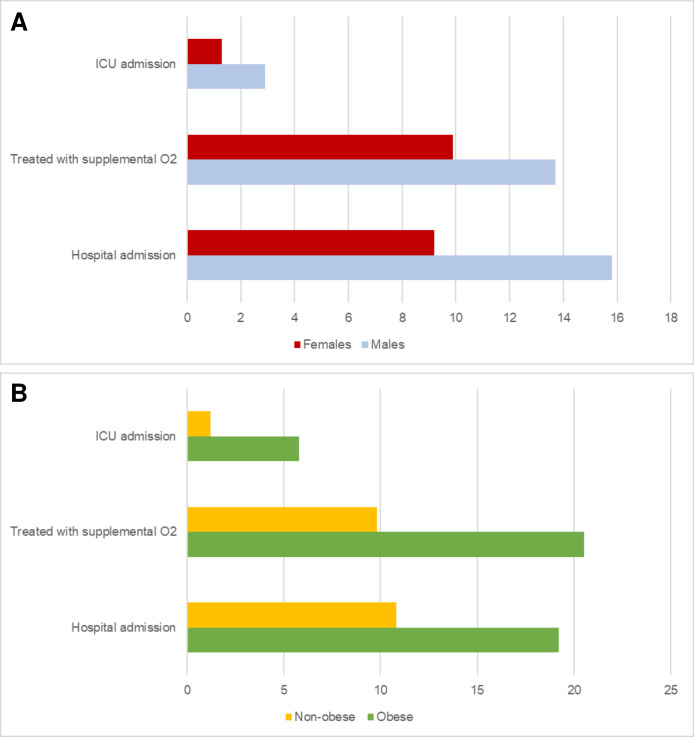

CI 6.025 to 16.435, p<0.0001) and obesity (OR: 82.823, 95% CI 32.192 to 213.084, p <<0.0001) predicted FM classification. Finally, as depicted in figure 1, male sex (figure 1A) and obesity (figure 1B) were associated with surrogate measures of COVID-19 severity, including higher hospital admission, treatment with supplemental oxygen and intensive care unit (ICU) admission.

CI 32.192 to 213.084, p <<0.0001) predicted FM classification. Finally, as depicted in figure 1, male sex (figure 1A) and obesity (figure 1B) were associated with surrogate measures of COVID-19 severity, including higher hospital admission, treatment with supplemental oxygen and intensive care unit (ICU) admission.

Table 4

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses with poststratification weights applied

| Univariate OR | P value | Multivariate OR | P value | |

| Age | 1.015 (1.001 to 1.029) | 0.036 | 1.006 (0.986 to 1.026) | 0.584 |

| Male gender | 4.975 (3.332 to 7.426) | <0.0001 | 9.951 (6.025 to 16.435) | <0.0001 |

| COVID-19 duration | 1.000 (0.991 to 1.009) | 0.962 | – | – |

| Had COVID-19 during the first wave | 1.537 (0.944 to 2.502) | 0.084 | 1.126 (0.523 to 2.426) | 0.762 |

| Had cough | 1.397 (1.003 to 1.945) | 0.048 | 1.090 (0.677 to 1.755) | 0.723 |

| Had dyspnoea | 1.786 (1.272 to 2.506) | 0.001 | 1.627 (0.922 to 2.870) | 0.093 |

| Had myalgia | 0.944 (0.665 to 1.341) | 0.749 | – | – |

| Had arthralgia | 0.822 (0.587 to 1.151) | 0.254 | – | – |

| Had anosmia | 0.842 (0.593 to 1.195) | 0.336 | – | – |

| Intensity of COVID-19 treatment setting | 1.727 (1.344 to 2.218) | <0.0001 | 1.548 (0.937 to 2.58) | 0.088 |

| Treated with analgesics/NSAIDs | 1.182 (0.828 to 1.686) | 0.357 | 0.983 (0.592 to 1.631) | 0.947 |

| Treated with LMWH | 2.180 (1.472 to 3.229) | <0.0001 | 1.897 (0.944 to 3.812) | 0.072 |

| Treated with HCQ | 1.969 (1.088 to 3.562) | 0.025 | 1.313 (0.464 to 3.713) | 0.607 |

| Treated with supplemental oxygen | 2.531 (1.514 to 4.229) | <0.0001 | 0.482 (0.181 to 1.283) | 0.144 |

| Pre-existent arthritis | 0.664 (0.273 to 1.614) | 0.366 | – | – |

| Pre-existent anxiety | 1.314 (0.858 to 2.013) | – | – | |

| Pre-existent depression | 1.255 (0.642 to 2.452) | 0.507 | – | – |

| Pre-existent high blood pressure | 3.061 (1.964 to 4.770) | <0.0001 | 1.511 (0.781 to 2.925) | 0.220 |

| Pre-existent diabetes | 0.849 (0.219 to 3.290) | 0.813 | – | – |

| Pre-existent pulmonary disease | 1.164 (0.634 to 1.164) | 0.624 | – | – |

| Pre-existent obesity | 41.192 (18.003 to 98.879) | <0.0001 | 82.823 (32.192 to 213.084) | <0.0001 |

P values <0.05 are highlighted in bold.

HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin; NSAIDs, Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Percentage of patients admitted to the hospital, treated with supplemental oxygen and admitted to ICU according to gender (A) or obesity (B). ICU, intensive care unit.

Given the significant role of male gender as a predictor of FM, we compared the clinical characteristics of male versus female respondents (online supplementary table S3). Although women had more symptoms during acute COVID-19, the rate of hospital admission was significantly higher in male respondents (15.8% vs 9.2%, p=0.001). Moreover, BMI was higher in men (26.3±4.3 kg/m2 vs 24.9±4.9 kg/m2) as was the percentage of overweight individuals (36.0% vs 23.1%, p=0.002). Similarly, when comparing non-obese versus obese individuals, the latter showed a higher rate of hospital admission (19.2% vs 10.8%, p=0.016) and treatment with supplemental oxygen (20.5% vs 9.8%, p=0.002) and admission to ICU (5.8% vs 1.2%, p=0.003).

kg/m2) as was the percentage of overweight individuals (36.0% vs 23.1%, p=0.002). Similarly, when comparing non-obese versus obese individuals, the latter showed a higher rate of hospital admission (19.2% vs 10.8%, p=0.016) and treatment with supplemental oxygen (20.5% vs 9.8%, p=0.002) and admission to ICU (5.8% vs 1.2%, p=0.003).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that self-reported clinical features of FM are common after symptomatic COVID-19, with an estimated prevalence of ~31%. Notably, this figure is similar to that found in other chronic painful disorders19 and comparable to the 30% recently reported for PACS after a similar follow-up.20

Globally, respondents with FM exhibited features suggestive of a more serious form of COVID-19, including a higher rate of hospitalisation and more frequent treatment with supplemental oxygen. Unfortunately, the study design did not allow accurate definition of the clinical severity of COVID-19,21 and thus, our evaluation relies solely on surrogate measures. However, when a multivariate model was built, obesity and male gender were identified as independent, strong predictors of being classified as FM. Notably, both male gender22 and obesity23 have been consistently associated with a more severe clinical course in patients with COVID-19, including a significantly increased mortality rate.

Strikingly, we found a high percentage of men (43%) in respondents meeting criteria for FM. Subanalysis of our data revealed that male gender was associated with surrogate measures of COVID-19 severity, as suggested by a significantly higher rate of patients requiring hospital admission. Thus, the most intuitive explanation for the increased prevalence of FM in men is the overall tendency to a more aggressive disease course. However, other speculative mechanisms may contribute to this phenomenon. Although it is a common belief that FM is a female-predominant disorder, an elegant study by Wolfe et al24 questioned this assumption, suggesting that gender specificity may be the consequence of several biases. Indeed, similarly to what we observed, they demonstrated that women represent ~59% of cases of FM when classification criteria are applied to individuals, as opposed to ‘traditional’, biased cohorts where they account for nearly 90% of patients. Similar figures have been reported in other studies,25 including a web-based survey.14

The second, perhaps strongest, predictor of FM in our cohort was obesity. The relationship between obesity and FM is mutual and bidirectional; in a recent systematic review and meta-analysis,26 our group demonstrated that BMI can influence nearly all domains of the syndrome.

Taken together, our data suggest a speculative mechanism in which obesity and male gender synergistically affect the severity of COVID-19 that, in turn, may rebound on the risk of developing post-COVID-19 FM syndrome and determine its severity. Interestingly, individuals who got COVID-19 during the first pandemic wave—when a prejudicial mix of hospital overloading and extremely limited knowledge of the disease affected the management of the disease—showed a tendency towards an increase in FM prevalence when compared with those who got COVID-19 during second wave, further emphasising a possible association with the disease severity and proper management.

Despite their usefulness in healthcare research, online surveys are affected by well-known intrinsic limitations.27 28 First, the respondents are not selected through probability sampling, and this may impair the generalisability of the findings; in addition, information about non-respondents is not available. Thus, a self-selection bias may arise because some individuals are more likely than others to complete online surveys. Several factors have been associated with non-response in health surveys,29 including male gender, younger age, lower socioeconomic status, and poorer health and health behaviours. Thus, the lower rate of male respondents in our survey is not surprising and reflects a well-known gender bias in survey-based research, with women being more prone to participate in online surveys.30 31

In an attempt to ascertain the presence of self-selection bias, we used a classical approach based on comparing study results with auxiliary information available from official government data. In Italy, the median age of confirmed COVID-19 cases is 47 years,18 and analysing official Italian Ministry of Health data collected from 24 February 2020 to 25 April 2021, we found that the mean daily percentage of hospitalised patients was 11.1% of all confirmed cases, while 1.4% were admitted to ICU. The figures observed in our sample, with 10.7% and 1.6% of patients, respectively, treated in a non-critical hospital setting or in an ICU, are therefore comparable to the general COVID-19 population. Moreover, also additional sociodemographic characteristics are similar. For instance, in 2020, taking into account the age range 30–59 years, 63.2% of the Italian population was married and 31% was single. Correspondingly, the majority of participants in our sample were married (70.9%), while only 18.8% were single.17

The only major difference between our study sample and the COVID-19 population in Italy is the female predominance of survey respondents. Although the overall gender ratio of COVID-19 is thought to be ~1:1, official data from the Italian Ministry of Health demonstrate an uneven distribution of COVID-19 cases, with a female predominance in the age range of 30–59 years and, on the contrary, a male predominance in individuals >60 years of age18; female predominance is perhaps more evident in certain populations, such as healthcare professionals. Similarly, a female predominance has been reported in other countries according to The Sex, Gender and COVID-19 Project, an online database of gender-disaggregated data on COVID-19.32 It is important to note that these data refer to the overall population of SARS-CoV-2-positive individuals and do not distinguish between mildly symptomatic (the vast majority in our sample) and fully asymptomatic individuals. Interestingly, available literature suggests that, taking into consideration only mild cases of COVID-19, women seem to be more represented than men.33–36 However, to account for this potential source of bias, we applied gender-calculated poststratification weights to all analyses; no major differences emerged when compared with raw data.

In conclusion, clinical features of FM are common in patients who recovered from symptomatic COVID-19. Preliminary evidence from clinical and preclinical studies suggests that several disease-specific mechanisms may explain the pathophysiology of this musculoskeletal syndrome, including virus-induced injury to endothelium37 or neuromuscular structures,38 immunological derangement and smouldering inflammation. Regarding the latter, it is interesting to note that some of the proinflammatory cytokines involved in COVID-19 and PACS manifestations, such as interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-6,2 39 may contribute to the pathogenesis of FM.40 41 Unfortunately, our data do not provide a mechanistic support in understanding the pathophysiology of fibromyalgianess in these patients and other, indirect and non-specific processes—for example, prolonged bed rest, deconditioning, post-traumatic stress disorder—may actually prevail. Moreover, the lack of a control group impairs the possibility to ascertain a possible contribution of the psychophysical distress associated with lockdown measures and other pandemic-related constraints on the susceptibility to FM-like symptoms in patients without a known SARS-CoV-2 exposure.

In the light of the overwhelming numbers of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, it is reasonable to forecast that rheumatologists will face up with a sharp rise of cases of a new entity that we defined ‘FibroCOVID’ to underline potential peculiarities and differences, such as the male involvement. From the rheumatology perspective, some open questions need to be addressed in the near future. First, how are patients, in general practice and other specialty settings (eg, infectious disease clinics), who deserve referral to the rheumatologist after COVID-19 identified for suspected FM? Easy-to-use, inexpensive and quick instruments, such as the Fibromyalgia Rapid Screening Tool42 questionnaire or the London Fibromyalgia Epidemiology Study Screening Questionnaire,43 may be the answer, but they need adequate validation in this new population of patients. Second, what is the optimal treatment strategy for FibroCOVID? Although no definitive protocols are still available for FM treatment, it is possible to hypothesise that a traditional approach including graded exercise, cognitive behavioural therapy and pain modulators may still help patients. On the other hand, given the suspected viral trigger, other treatments (eg, immune-modulating agents) or SARS-CoV-2 vaccines may provide specific benefits. Finally, what is the clinical course of post-COVID-19 musculoskeletal symptoms? Prospective studies, including comparative analysis with primary FM cohorts, will shed light on this topic.

Footnotes

JC and LM contributed equally.

Contributors: FU, JC and RM conceived and designed the work, analysed the data and prepared the first draft of the manuscript; LM, LL, VB, CC, MDO, AM, EB, JFC, MLR, PV, PR and MM contributed to the acquisition of data; RDG, NB, CB, AG, AI, RG, CF and MPL contributed to the acquisition and interpretation of data; all author revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, approved the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the local ethics committee (Comitato Etico Area Vasta Emilia Centrale, Bologna, Italy). The research was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its latest amendments. No personally identifiable information was collected and data remained completely anonymous throughout the study. The local ethics committee, Comitato Etico Area Vasta Emilia Centro, exempted this study for the following reasons: (1) no personally identifiable information was collected and data remained completely anonymous throughout the survey; (2) the use and communication of the data collected were performed according to the European General Data Protection Regulation (2016/679); (3) no diagnostic or therapeutic intervention was delivered to research participants, and therefore there was no risk of physical harm to individuals who participated; (4) no risk of informational or psychological harms; and (5) no enrolment of vulnerable individuals with diminished autonomy.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2021-001735

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://rmdopen.bmj.com/content/rmdopen/7/3/e001735.full.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/112351655

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1136/rmdopen-2021-001735

Article citations

Understanding Non-Pharmacological Treatments for Fibromyalgia Functional and Well-Being Status: The Role of Literacy.

Healthcare (Basel), 12(19):1956, 30 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39408136 | PMCID: PMC11475347

New-Onset Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain Following COVID-19 Infection Fulfils the Fibromyalgia Clinical Syndrome Criteria: A Preliminary Study.

Biomedicines, 12(9):1940, 23 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39335454 | PMCID: PMC11429044

Common Non-Rheumatic Medical Conditions Mimicking Fibromyalgia: A Simple Framework for Differential Diagnosis.

Diagnostics (Basel), 14(16):1758, 13 Aug 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 39202246 | PMCID: PMC11354086

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback Efficacy on Fatigue and Energy Levels in Fibromyalgia: A Secondary Analysis of RCT NCT0412183.

J Clin Med, 13(14):4008, 09 Jul 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39064048 | PMCID: PMC11278324

Inflammation, Autoimmunity, and Infection in Fibromyalgia: A Narrative Review.

Int J Mol Sci, 25(11):5922, 29 May 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38892110 | PMCID: PMC11172859

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (47) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

A Cross-Sectional Study of Fibromyalgia and Post-acute COVID-19 Syndrome (PACS): Could There Be a Relationship?

Cureus, 15(7):e42663, 29 Jul 2023

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 37644924 | PMCID: PMC10462402

Prevalence of post-COVID-19 in patients with fibromyalgia: a comparative study with other inflammatory and autoimmune rheumatic diseases.

BMC Musculoskelet Disord, 23(1):471, 19 May 2022

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 35590317 | PMCID: PMC9117853

The possible onset of fibromyalgia following acute COVID-19 infection.

PLoS One, 18(2):e0281593, 10 Feb 2023

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 36763625 | PMCID: PMC9916594

Could the fibromyalgia syndrome be triggered or enhanced by COVID-19?

Inflammopharmacology, 31(2):633-651, 27 Feb 2023

Cited by: 9 articles | PMID: 36849853 | PMCID: PMC9970139

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

1,2

1,2