Abstract

Free full text

A Combinatorial Code for Gene Expression Generated by Transcription Factor Bach2 and MAZR (MAZ-Related Factor) through the BTB/POZ Domain

Abstract

Bach2 is a B-cell- and neuron-specific transcription repressor that forms heterodimers with the Maf-related oncoproteins. We show here that Bach2 activates transcription by interacting with its novel partner MAZR. MAZR was isolated by the yeast two-hybrid screen using the BTB/POZ domain of Bach2 as bait. Besides the BTB/POZ domain, MAZR possesses Zn finger motifs that are closely related to those of the Myc-associated Zn finger (MAZ) protein. MAZR mRNA was coexpressed with Bach2 in B cells among hematopoietic cells and in developing mouse limb buds, suggesting a cooperative role for MAZR and Bach2 in these cells. MAZR forms homo- and hetero-oligomers with Bach2 through the BTB domain, which oligomers bind to guanine-rich sequences. Unlike MAZ, MAZR functioned as a strong activator of the c-myc promoter in transfection assays with B cells. However, it does not possess a typical activation domain, suggesting a role for it as an unusual type of transactivator. The fgf4 gene, which regulates morphogenesis of limb buds, contains both guanine-rich sequences and a Bach2 binding site in its regulatory region. In transfection assays using fibroblast cells, the fgf4 gene was upregulated in the presence of both MAZR and Bach2 in a BTB/POZ domain-dependent manner. The results provide a new perspective on the function of BTB/POZ domain factors and indicate that BTB/POZ domain-mediated oligomers of transcription factors may serve as combinatorial codes for gene expression.

Eukaryotic genes are most often regulated by the simultaneous, synergistic activity of several transcription factors. Protein-protein interactions play important roles in synergistic activity among these factors. In this respect, the BTB/POZ domain (2, 4, 43) may be of particular interest because of its recurrent presence in transcription factors and its activity with regard to directing specific interactions. The genome project of Caenorhabditis elegans revealed that worms possess more than 100 genes that code for BTB/POZ domain proteins. Thus the BTB/POZ domain constitutes one of the largest families of protein domains in multicellular organisms (10). Interestingly, transcription factors encoding this domain are thought to play a variety of structural and organizational roles (1, 2, 4, 13, 21, 34, 35). For example, the Drosophila GAGA factor is involved in chromatin remodeling and in mediating enhancer-promoter interactions (34). Alterations of the PLZF and BCL6 genes, both encoding BTB/POZ factors, are associated with oncogenesis (9, 41). BTB/POZ domains appear to direct specific protein-protein interactions. However, the exact significance of such interactions in transcription regulation remains unclear.

The mammalian transcription factors Bach1 and Bach2 (36) belong to the CNC-related bZip factors that include the hematopoietic factors NF-E2 p45 (3), Nrf1 (6, 7, 28), Nrf2 (18, 31), and Nrf3 (24). Among these factors, Bach1 and Bach2 are unique in that they each possess a BTB/POZ domain. The CNC-related factors form heterodimers with the Maf-related factors through the leucine zippers and bind to the DNA sequence motif called MARE, which contains an AP-1 binding sequence. MARE is found in regulatory regions of various genes like β-globin genes, immunoglobulin heavy-chain genes, antioxidant response genes (e.g., GST genes), and crystallin genes (20). These observations suggest that transcription factors binding to the MARE may play important roles in a variety of vertebrate cell types and that only very few of the actual target genes of the CNC family have been identified.

Among the CNC-related factors, Bach1 and Bach2 function as transcription repressors. In B cells, Bach2 represses the immunoglobulin heavy-chain 3′ enhancer, or LCR, perhaps through binding to the corepressor SMRT (32). Since Bach2 possesses the BTB/POZ domain in the N terminus, it may regulate gene expression by interacting with other factors through the BTB/POZ domain. In this study, we identified a new BTB/POZ domain factor, MAZR, which associates with Bach2 through the BTB/POZ domain. MAZR stimulated transcription despite of its lack of any apparent transcription activation domain. Rather, BTB/POZ-mediated oligomer formation was important for transcriptional activity, suggesting that MAZR might be not a typical transactivator but an architectural transcription factor like Drosophila GAGA factor (21). Together with previous observations, our results suggest that BTB/POZ-mediated oligomers of transcription factors play important roles in gene activation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Abbreviations.

The following abbreviations are used: AER, apical ectodermal ridge; Bach1 and Bach2, BTB and CNC homology factors 1 and 2, respectively; BTB, broad complex tramtrack bric-a-brac; bZip, basic region leucine zipper; CNC, Cap'n' collar; DBD, DNA binding domain; dpc, days post coitus; EMSA, electrophoretic mobility shift analysis; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; MARE, Maf recognition element; MAZ, Myc-associated Zn finger protein; MAZR, MAZ-related factor; MBP, maltose-binding protein; LCR, locus control region; POZ, pox and Zn finger; GAD, GAL4 activation domain; GBD, GAL4 DNA-binding domain; G-rich, guanine rich; PLZF, promyelocytic leukemia Zn finger; BCL6, B-cell lymphoma 6; GST, glutathione S-transferase; SMRT, silencing mediator of retinoid and thyroid receptor.

Two-hybrid screen and assays.

The bait plasmid pGBD-Bach2/BTB was constructed by inserting a portion of the Bach2 cDNA, encoding the amino-terminal 413 residues, into the EcoRI site of pGBT9 (Clontech) after isolating the cDNA fragment by PCR. The yeast two-hybrid screen was performed, as described previously (36), by using pGBD-Bach2/BTB as bait and a 17-dpc embryo cDNA library (Clontech). Approximately 2 × 108 yeast transformants were screened for His autotrophy, and β-galactosidase filter assay was used to isolate three positive clones. One of them was sequenced in both directions. The transformation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae SFY526 and measurements of β-galactosidase activities were performed as described previously (24).

Plasmids.

pEF-MAZR was generated by inserting the 2.4-kbp EcoRI fragment into the fill-ended BssHII site of pEF-BssHII (30). The FLAG epitope-tagged expression plasmids pEF-fMAZR, pEF-fMAZRΔBTB, pEF-fMAZRΔ(1-219) and pEF-fMAZRΔ(1-288) were created as follows. The 2.4-kbp EcoRI fragment of GAD-MAZR and the PCR-created fragments were inserted into the EcoRI site of pBSK-FLAG (a kind gift from K. Itoh). The BssHII fragments of the resultant plasmids were subcloned into the BssHII site of pEF-BssHII. The primers used were 5′-CGGAATTCAGGTCGGTCATCGAGATCTG-3′, 5′-CGGAATTCATTGCGGGCCAAGCTTCTCT-3′, 5′-CGGAATTCGCAGGCATCCTTCCATGTGG-3′, and T7. The 2.4-kbp fill-ended BamHI fragment of the resultant plasmid was inserted into the blunt-ended BssHII site of pEF-BssHII. Expression plasmids of GAD-MAZR/BTB and GBD-MAZR/BTB were constructed by inserting the 900-bp PCR-created fragment of GAD-MAZR into the EcoRI sites of GAD424 and GBD, respectively, and that of GBD-Bach2/bZip was constructed by inserting the 1.3-kbp PCR-created fragment of pCMSV Bach2J/F into the EcoRI-BamHI site of GBD. GAD-MAZRΔBTB was created by inserting the 2-kbp EcoRI fragment of pEF-fMAZRΔBTB into the EcoRI site of GAD424. pGBD-Bach1/BTB, which expresses Bach1 BTB domain fused with the GBD, was described previously (36). Expression plasmids of pcDNA GAL4DBD and pcDNA GAL-MAZR(1-288) were generated by inserting the 900- and the 1,900-bp HindIII fragments of pGBT9 and GBD-MAZR/BTB into the HindIII site of pcDNA3.1/Myc-HisC (Invitrogen), respectively. pcDNA-GAL-MAZR, pcDNA-GAL-MAZR(288-641), pcDNA-GAL-MAZR(1-145), pcDNA-GAL-MAZR(145-288), pcDNA-GAL-MAZR(145-219), and pcDNA-GAL-MAZR(219-288) were created by subcloning the 2,400-bp EcoRI fragment of GAD#49-1 and the respective PCR-created fragments into the EcoRI site of pcDNA GAL4. The primers used were 5′-CGGAATTCAGCAGCACCTGTGGCCCTGG-3′, 5′-CGGAATTCTCAATCAGCAGGAACTTGGC-3′, 5′-CGGAATTCCCTCAAGCCCCCTGGA-3′, 5′-CGGAATCAGGTCGGTCATCGAGATCTG-3′, and 5′-TACCACTACAATGGATG-3′.

RNA blot analysis.

Total RNA samples from various tissues and cultured cell lines were prepared by the guanidine-acidified phenol chloroform method (11). RNA samples were electrophoresed with a 1.0% agarose gel containing 1.1 M formaldehyde and transferred onto ZetaProbe membranes (Bio-Rad). Radiolabeled probe was prepared from the full-length cDNA of MAZR and hybridized at 65°C for 1 h with ExpressHybri (Clontech).

In situ RNA hybridization.

Embryos (10.5 dpc) were analyzed for MAZR, Bach2, and FGF4 expression by whole-mount in situ hybridization with digoxygenin-labeled RNA probes, as described previously (40). MAZR probe (full length of cDNA), Bach2 probe (nucleotides 232 to 793), and FGF4 (full-length cDNA; a kind gift from G. Martin [15a]) in pBluescript were transcribed in the antisense and sense directions. In situ hybridization was performed essentially as described previously (40), with 0.3 to 0.5 μg of cRNA probe per ml at 65°C for 1 h.

Transient transfection assay.

pMycluc was constructed by inserting a HindIII fragment of about 2,400 bp from pMycCAT (a kind gift from Kazunari Yokoyama, RIKEN) into the HindIII site of pGL3 (Promega). An internal deletion of the pMycluc was performed by the PCR amplification of a desired fragment using primers 5′-CGCTGAGTATAAAAGCCGGTTTTCGGGGCT-3′ and 5′-AGGCAGGAGGGGAGCCAGGGACGGCCGGGG-3′ and ligation. The 2,000-bp HindIII fragment of the resultant plasmid was resubcloned into the HindIII site of pGL3 (pMycΔMEluc). pFGF4luc was generated by inserting the 4,300-bp PCR-created fragment of 5′ fgf4 promoter into the KpnI site of pGL3. The primers used were 5′-GGTCCGCACAAAGGGCCACACACTGCTAGGCTGAT-3′ and 5′-TTGTACCGCGCGCCCAGCCCTCCGGAGCAGTGGTATA-3. pFGF4Δluc was generated by deletion of the 600-bp EcoRI-Asp718 fragment from pFGF4luc. Transient transfection assay and luciferase assay were performed as described previously (24).

DNA binding site selection and EMSA.

MBP-MAZR(251-641) was constructed by inserting the 1,800-bp PCR-created fragment into the EcoRI-SalI site of pMAL-c2 (New England Biolabs). Primers used were 5′-CGAATTCCCTAATGTGGCATCCAG-3′ and M13-20. Expression of MBP-MAZR(251-641) in Escherichia coli was performed as described previously (24), but with a minor modification. Briefly, a chimeric protein bound on the amylose resin was eluted with buffer (20 mM Hepes-NaOH [pH 7.9], 100 mM NaCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 20% glycerol, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 0.1% NP-40) containing 10 mM maltose. DNA binding site selection assay was performed as described previously (36). The oligonucleotide probe used for the EMSA contained both the G-rich element and the MARE and had the following sequence: 5′-GATCCTCTGTGGGGGGGGGACACTCGAAAGGAGCTGACTCATGCTAG-3′ (each recognition element indicated by underlining). An oligonucleotide probe containing the G-rich element and a mutated MARE had the following sequence: 5′-GATCCTCTGTGGGGGGGGGACACTCGAAAGGATCTTACTTATGCTAG-3′ (mutations indicated by underlining).

In vivo pull-down assay.

The expression plasmid of GST-MAZR was generated by inserting the 1,800-bp BamHI fragment of pEF-fMAZR into the BamHI site of pBosGST (23). Pull-down assays were performed as described previously (23). Precipitated Bach2 was visualized by immunoblot analysis using anti-F69-2 antibody (36).

Preparation of antisera.

The expression plasmid of MBP-fused MAZR (amino acids 490 to 641) was generated by inserting the PCR-created fragment into the EcoRI and SalI sites of pMAL-c2. The primers used were 5′-GGAATTCAGTGAGGGGCCCAGCAACTT-3′ and T7. Expression and purification of MBP-fused MAZR (amino acids 490 to 641) were carried out as described above. The purified fusion protein was used to immunize two Japanese White rabbits by an adjuvant system (RIBI Immunochem Research, Inc.).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper will appear in the DDBJ, EMBL, and GenBank nucleotide sequence databases with the accession number AB029397.

RESULTS

Isolation of a cDNA encoding a Bach2-associated factor.

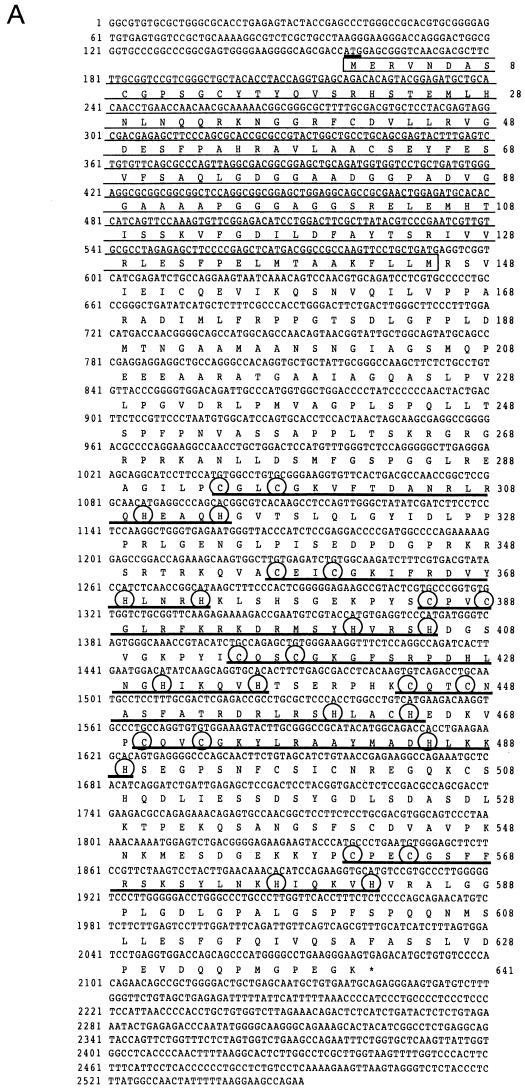

We searched for a protein molecule(s) which associates with the BTB/POZ domain of Bach2, by using a yeast two-hybrid screen. The yeast cell Hf7c was transformed with a 17-dpc mouse embryo cDNA library (2 × 108 CFU) along with a bait plasmid that expressed a fusion protein of the BTB/POZ domain of Bach2 and GBD. Positive transformants were selected for His autotrophy, and three positive cDNA clones were isolated. After DNA sequencing, one of them was found to encode a BTB/POZ domain in the N terminus and seven C2-H2 type Zn finger domains in the C-terminal end (Fig. (Fig.1A).1A). No preceding in-frame stop codon was noted within the 5′ region of this cDNA. We tentatively assigned the first methionine codon in this clone as an initiation codon (Fig. (Fig.1A)1A) because BTB/POZ domains are usually located at the N termini of proteins. The nucleotide sequence around the putative initiation ATG codon matches the translation initiation site consensus sequence reported by Kozak (26). The open reading frame encodes a predicted protein of amino acid residues with a calculated molecular mass of 69,034 Da (Fig. (Fig.1A).1A). We refer to it as MAZR (see below).

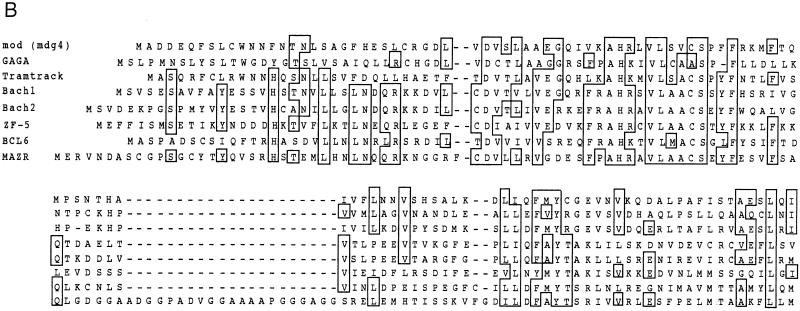

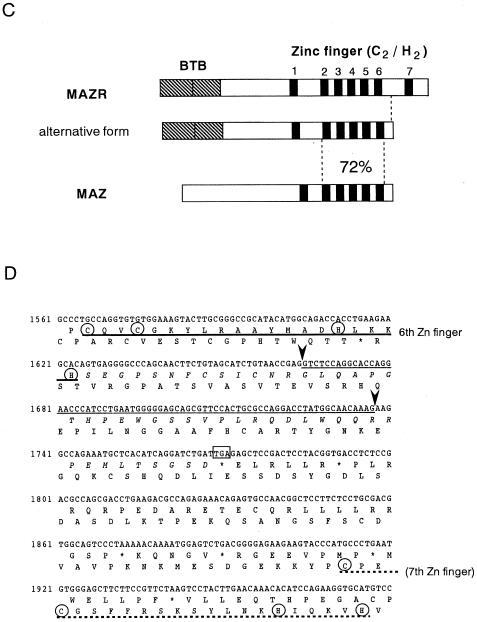

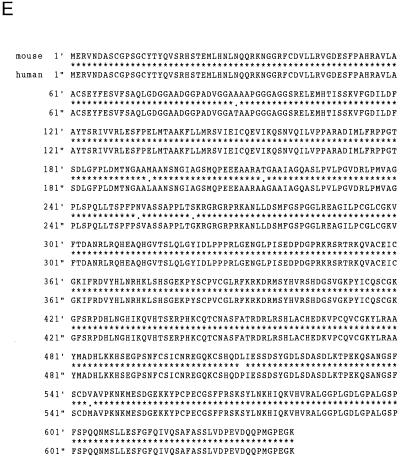

Cloning and structure of MAZR. (A) Nucleotide sequence and deduced amino acid sequence of mouse MAZR cDNA. The BTB/POZ domain is indicated by the opened box. The Zn finger domains and the Cys and His residues in these domains are indicated by the thick lines and circles, respectively. The underlined ATG is a putative initiation codon. (B) Comparison of the BTB domains of mod (mdg4), GAGA factor, Tramtrack, Bach1, Bach2, ZF5, and BCL6. Boxes indicate amino acids conserved among at least four proteins. The Gly- and Ala-rich sequence within the BTB domain of MAZR is indicated below. (C) Schematic comparison of MAZR, its alternative form, and MAZ. (D) Nucleotide and amino acid sequences of the alternative form of MAZR. Junctions of the alternative exon are indicated with arrowheads. (E) Comparison of mouse and human MAZR. Exons for human MAZR were predicted from the genomic sequence (DDBJ accession no. AC005003), and were used to deduce the amino acid sequence.

The BTB/POZ domain encoded by this clone is distinct from those of other BTB/POZ proteins in that a glycine- and alanine-rich short sequence was inserted into its middle (Fig. (Fig.1B).1B). This inserted sequence might confer some specific function to this domain. Among the Zn finger domains, the second to the sixth fingers show 72% homology to those of MAZ (Fig. (Fig.1C)1C) (5, 22, 38). MAZ was identified as a regulatory factor that binds to a G-rich element within the promoter region of the c-myc gene. The similarity of the Zn fingers of MAZ and MAZR suggests the possibility that MAZR also recognizes a G-rich element through these Zn finger motifs (described below). We also found an alternative form of MAZR during expression analyses by reverse transcription-PCR (data not shown). A 73-bp alternative exon was inserted into the boundary between exons which encode the sixth and the seventh Zn finger domains, respectively. This insertion results in a shifting of the reading frame, creating an in-frame termination codon in the seventh Zn finger exon (Fig. (Fig.1D).1D). Therefore, this alternative form lacks the seventh Zn finger and thus has a calculated molecular mass of 57,996 Da.

A search for related sequences in the databases identified a human genomic DNA sequence (GenBank accession number AC005003) that covers a 198-kbp region. Four segments within this sequence showed significant homology to mouse MAZR cDNA, indicating that these segments are exons for the human MAZR gene. Predicted human MAZR cDNA showed 91% identity with mouse MAZR cDNA. At the amino acid level, they showed 99% identity (Fig. (Fig.1E).1E). The AC005003 sequence is derived from chromosome 22 (22q12-14). This chromosomal localization was confirmed by chromosome mapping using the human radiation hybrid panel (data not shown).

Expression profile of MAZR overlaps that of Bach2.

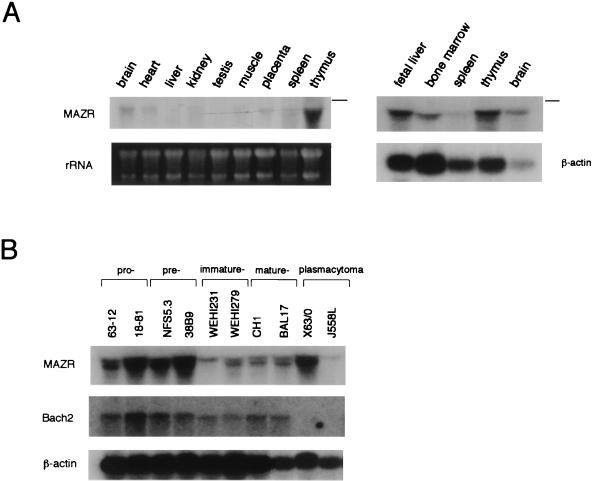

To shed light on the biological function of MAZR, its expression profile was determined by RNA blot analyses (Fig. (Fig.2A).2A). High levels of MAZR mRNA were detected in thymus, fetal liver (13.5 dpc), and bone marrow. In addition to hematopoietic tissues, various other tissues expressed MAZR mRNA at much lower levels. Since Bach2 shows a stage-specific expression during B-cell differentiation, we compared the expression of MAZR and Bach2 in various cell lines representing each stage of B-cell differentiation (Fig. (Fig.2B).2B). Expression of MAZR was highly abundant in the early stages of B cells (i.e., pro- and pre-B-cell lines). These results suggest that MAZR regulates gene expression in hematopoietic cells and that MAZR cooperates with Bach2 during early stages of B-cell differentiation.

Expression profile of MAZR. RNA blot analyses with total RNAs derived from mouse tissues (A) and B-cell lines representing various developmental stages (B). Positions of 28S rRNA are indicated by lines.

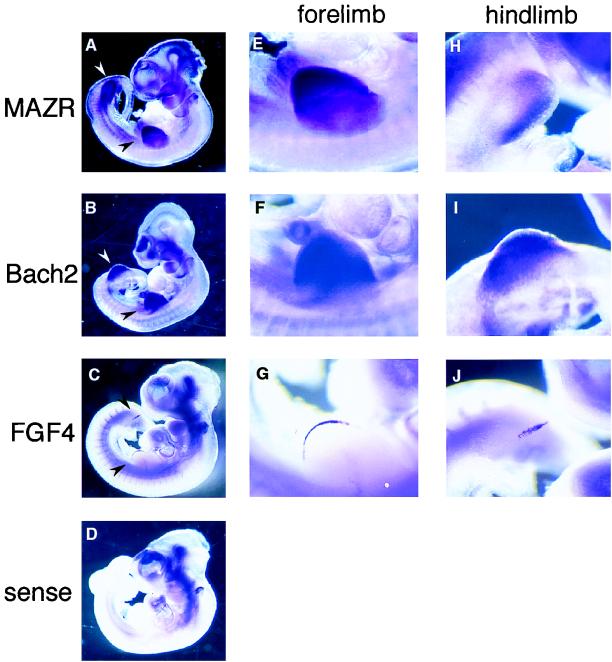

To test further the possible function of Bach2 and MAZR in development, we investigated the expression of MAZR and Bach2 during embryogenesis by whole-mount in situ hybridization. Interestingly, MAZR and Bach2 mRNAs were both expressed strongly in the limb buds of 10.5-dpc mouse embryos. Both MAZR and Bach2 mRNA showed broad patterns of expression within the limb buds (Fig. (Fig.3A,3A, B, E, F, H, and I). However, their expression increased toward the edges of limb buds, where the AER was located. Expression of FGF4 mRNA, a marker for AER, was confined to the AER (Fig. (Fig.3C,3C, G, and J) but contained within the Bach2- and MAZR-expressing regions. These observations suggest that, in addition to cooperating in B-cell differentiation, Bach2 and MAZR cooperate in limb bud development. Besides being expressed in the limb buds, MAZR mRNA was expressed strongly in the midbrain region.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization on 10.5-dpc mouse embryos with MAZR, Bach2, and FGF4 cRNA probes. (A to D) Lateral views of 10.5-dpc embryos hybridized with MAZR, Bach2, FGF4 cRNA probes, and sense probe, respectively. Limb buds are indicated with arrow heads. (E to J) Higher magnifications of the forelimbs (E to G) and hindlimbs (H to J) revealing MAZR, Bach2, and FGF4 expressions, respectively.

In vivo interaction between MAZR and Bach2.

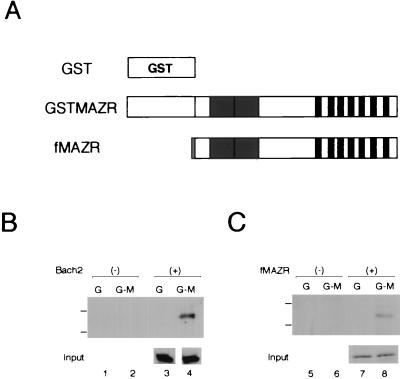

We verified an interaction between MAZR and Bach2 by the in vivo pull-down assay. GST-fused MAZR was transiently expressed along with Bach2 in the human embryonic kidney cell line, 293T, and was pulled down by glutathione beads. The precipitates were separated on a sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel and examined for the presence of Bach2 by immunoblot analysis (Fig. (Fig.4A4A and B). Bach2 could be precipitated with GST-MAZR (Fig. (Fig.4B,4B, lane 4) but not with the GST tag alone (Fig. (Fig.4B,4B, lane 3). These results indicate that MAZR indeed interacts with Bach2 in mammalian cells as well as in yeast cells. Interestingly, when FLAG-tagged MAZR was expressed along with GST-MAZR, it was also precipitated together with GST-MAZR (Fig. (Fig.4C),4C), indicating that MAZR could form a homomeric complex.

In vivo interaction between MAZR and Bach2. (A) Schematic representation of GST-fused MAZR and FLAG-tagged MAZR (fMAZR). Dotted box indicates the FLAG epitope. (B and C) GST-MAZR, Bach2 and fMAZR were transiently expressed in 293T cells in various combinations as indicated. Whole-cell extracts were incubated with glutathione beads and precipitates were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting using anti-Bach2 (αF69-2 serum) (B) and anti-FLAG (C). Positions of molecular markers (116 and 83 kDa) are shown on the left. G, GST; G-M, GST-MAZR.

MAZR interacted with Bach2 through BTB/POZ domain.

To examine the specificity of the association between MAZR and Bach2, we attempted to define regions that are involved in the interaction by the two-hybrid system. For this purpose, the S. cerevisiae strain SFY526, which carries a LacZ reporter gene with binding sites for GAL4, was used. Several domains of MAZR and Bach2 were fused to the GBD or the GAD (Fig. (Fig.5)5) and were expressed in yeast cells. Interactions between these chimeric proteins were determined by measuring the LacZ activities. As shown in Table Table1,1, control experiments using GBD plasmid and GAD424, GAD-MAZR, GAD-MAZR/BTB, or GAD-MAZRΔBTB did not reveal any LacZ reporter activity. Similarly, another set of control experiments using GAD424 and GBD-MAZR/BTB or GBD-Bach2/BTB showed no LacZ activities. GBD-Bach2/bZip was found to activate the LacZ reporter expression (1.4 Miller units). This might be due to a cryptic transactivation domain present on Bach2. Significant enhancement of LacZ activity was observed when yeast cells were transformed with GBD-Bach2/BTB and GAD-MAZR or GAD-MAZR/BTB. GAD-MAZRΔBTB (lacking the BTB/POZ domain) did not exhibit association activity with GBT-Bach2/BTB. Taken together, these data suggest that interaction between MAZR and Bach2 is mediated primarily by their BTB/POZ domains. Besides this interaction, MAZR appeared to interact with the bZip domain of Bach2, but at a lower affinity than with BTB domain of Bach2 (GAD-MAZR and GBD-Bach2/bZip). Interestingly, MAZR formed a homomeric complex more efficiently than it formed a heteromeric complex with Bach2 in yeast cells (compare GAD-MAZR and GBD-MAZR/BTB with GAD-MAZR and GBD-Bach2/BTB). In addition to interacting with Bach2, MAZR interacted with Bach1 (GAD-MAZR and GBD-Bach1/BTB).

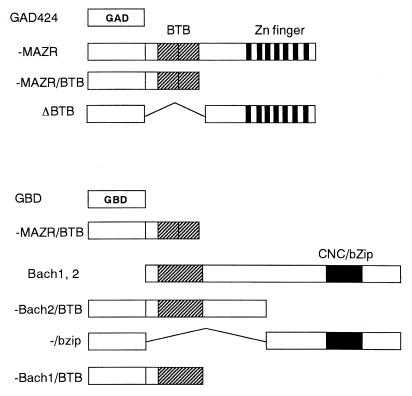

Schematic representation of GAL4 fusions. MAZR, Bach2, and Bach1 proteins were fused to the GBD and the GAD.

TABLE 1

MAZR interacts with Bach1 and Bach2 through their BTB/POZ domains in a yeast two-hybrid systema

systema

| Domain or fusion | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units) of cells transformed with:

| |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAD424 | GAD-MAZR | GAD-MAZR/BTB | GAD-MAZRΔBTB | |

| GBD | 0.029 (1) (1) | 0.025 (0.86) (0.86) | 0.062 (2.1) (2.1) | 0.04 (1.4) (1.4) |

| GBD-MAZR/BTB | 0.053 (1) (1) | 14 (264) (264) | 7.7 (145) (145) | 0.052 (0.98) (0.98) |

| GBD-Bach2/BTB | 0.034 (1) (1) | 0.56 (16) (16) | 0.014 (4.1) (4.1) | 0.026 (0.76) (0.76) |

| GBD-Bach2/bZip | 1.4 (1) (1) | 4.4 (3.1) (3.1) | ||

| GBD-Bach1/BTB | 0.065 (1) (1) | 0.88 (13) (13) | ||

MAZR recognizes G-rich sequences in vitro and activates c-myc promoter.

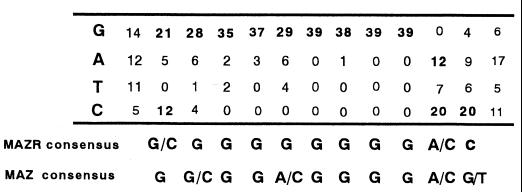

To gain clues regarding target genes regulated by MAZR and Bach2, we determined the optimal recognition element of MAZR by the DNA-binding site selection experiment. A C-terminal end of MAZR including seven Zn fingers was expressed in E. coli as an MBP fusion protein [MBP-MAZR(251-641)]. After three rounds of selection by EMSA and PCR amplification, bound DNA fragments were subcloned and sequenced. As tabulated in Fig. Fig.6,6, MAZR bound to G-rich sequences. As expected from the similarity in their Zn finger domains, the binding site consensus for MAZR is highly related to that of MAZ (Fig. (Fig.6,6, below). Thus, MAZR and MAZ likely regulate a similar set of target genes.

Selection of G-rich sequences by MAZR. The tally was compiled by aligning sequences of 39 independent clones selected by MBP-MAZR(251-641). The n for each position varies, because whenever nonrandom portions of the DNA overlapped with the aligned sequence, these sequences were excluded from the analysis. The consensus site is shown below the tally. The consensus sequence for MAZ binding (37) is also shown below the tally.

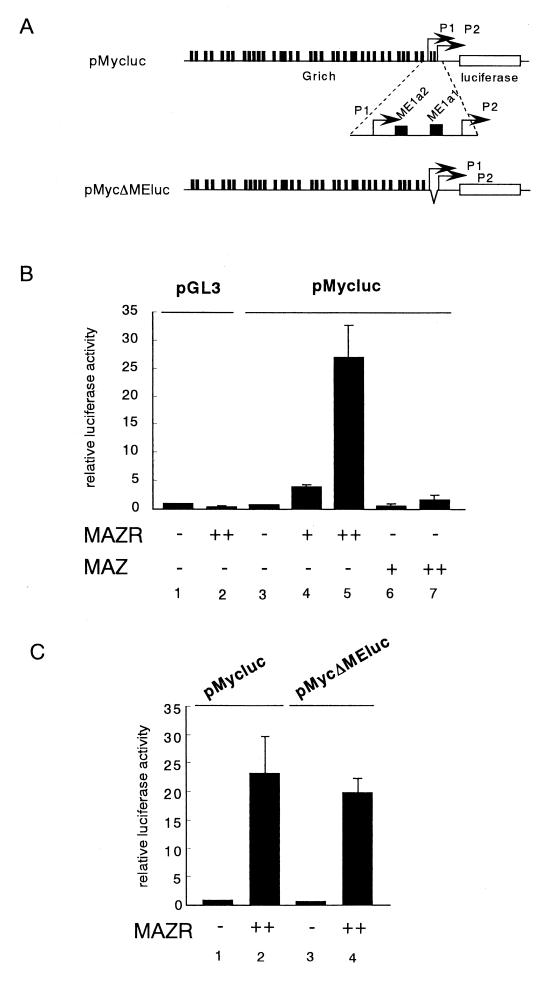

One of the target genes of MAZ is c-myc. A majority of c-myc transcripts initiate at its P2 promoter, which contains the G-rich sequence elements ME1a1 and ME1a2 (Fig. (Fig.7A).7A). MAZ represses P2 promoter activity through binding to ME1a2 (19). We compared effects of MAZR and MAZ on the c-myc promoter activity in a transfection assay using the pro-B-cell line 18-81. As shown in Fig. Fig.7B,7B, MAZR strongly activated the expression of the c-myc promoter plasmid in a dose-dependent manner, whereas MAZ showed only marginal effects. Unexpectedly, internal deletion of both ME1a1 and ME1a2 elements from the P2 promoter did not abolish the effect of MAZR (Fig. (Fig.7A7A and C). Perhaps the presence of other G-rich sites in c-myc promoter (Fig. (Fig.7A)7A) compensated for the loss of ME1a1 and ME1a2 elements. These results indicated that, even though MAZ and MAZR possess similar DNA binding Zn finger domains, they are endowed with distinct biochemical functions. MAZR may be a physiological transcriptional activator of the c-myc gene in B cells.

MAZR transactivates the c-myc promoter. (A) Schematic structures of pMycluc and pMycΔMEluc reporters. (B and C) Increasing amounts of MAZR and MAZ expression plasmid (0.1 and 1 μg) were transfected into 18-81 B-cell lines along with the pMycluc, pRGBP4, or pMycΔMEluc reporter (1 μg) and an internal control plasmid, pEF-SP (0.25 μg). The results are the means of five independent transfections.

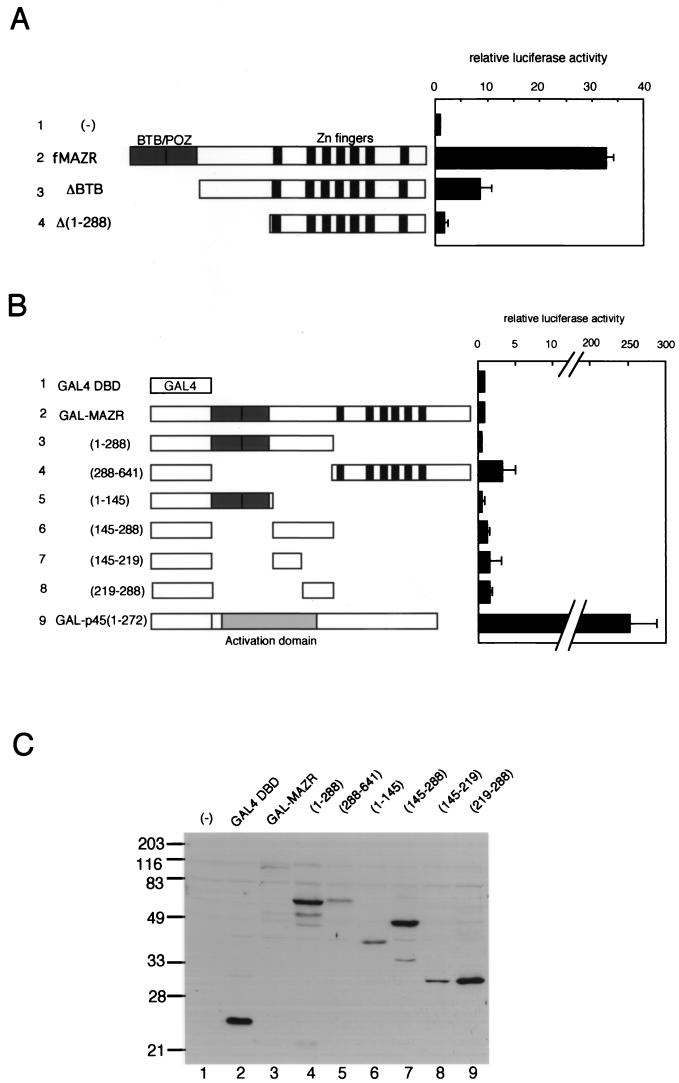

MAZR functions as an unusual type of transcription factor.

Having established that MAZR is a transcription activator, we next examined various MAZR derivatives to locate the transactivation domain of MAZR using the c-myc reporter gene. As shown in Fig. Fig.8A,8A, N-terminal deletion mutants of MAZR were expressed in 18-81 cells. Interestingly, deletion of BTB domain from MAZR (fMAZRΔBTB) reduced its transcription activity, whereas deletion of most of the region N-terminal to the Zn finger domains abolished its activity. To test whether the N-terminal region is a transactivation domain, we utilized the GAL4 fusion system (Fig. (Fig.8B).8B). Chimeric proteins of several portions of MAZR fused to the GBD were expressed in 18-81 cells along with the reporter plasmid which contains four copies of the GAL4 binding sites. As a positive control, GAL-p45(1-272) which contains the transactivation domain of NF-E2 p45 (33) was also compared. GAL-p45(1-272) strongly activated expression of the reporter gene, so that the level was about 250-fold greater (Fig. (Fig.8B,8B, row 9). In contrast, all of the MAZR fusion proteins showed only very weak activity (Fig. (Fig.8B,8B, rows 2 to 8). Most importantly, the N-terminal region of MAZR, including the BTB/POZ domain, did not show any transcriptional activity (Fig. (Fig.8B,8B, rows 3, 5, and 6). Expression levels of these fusion proteins were determined by Western blotting, as shown in Fig. Fig.8C.8C. These intriguing results suggested that MAZR functions not as a typical transactivator but as another type of transcription factor, like GAGA, which is also a BTB/POZ factor (see Discussion).

Examination of MAZR transactivation domain. (A) Schematic representation and transcriptional activity of MAZR deletion mutants. The experiment procedure is described in the legend of Fig. Fig.7.7. (B) Schematic representation and transcriptional activity of portions of MAZR fused to the GBD. Each expression plasmid (1 μg) was introduced into 18-81 cells along with pG4TATAluc reporter (1 μg) and pEF-SP (0.25 μg) as an internal control. GAL-p45(1-272) was described previously (33). (C) Western blot analysis of QT6 whole-cell extracts expressing GAL4-MAZR fusion proteins using anti-GAL4 DBD antibody (Upstate Biotechnology). Molecular size markers are shown to the left. (−), mock transfection.

Synergistic transactivation of fgf4 gene expression by MAZR and Bach2.

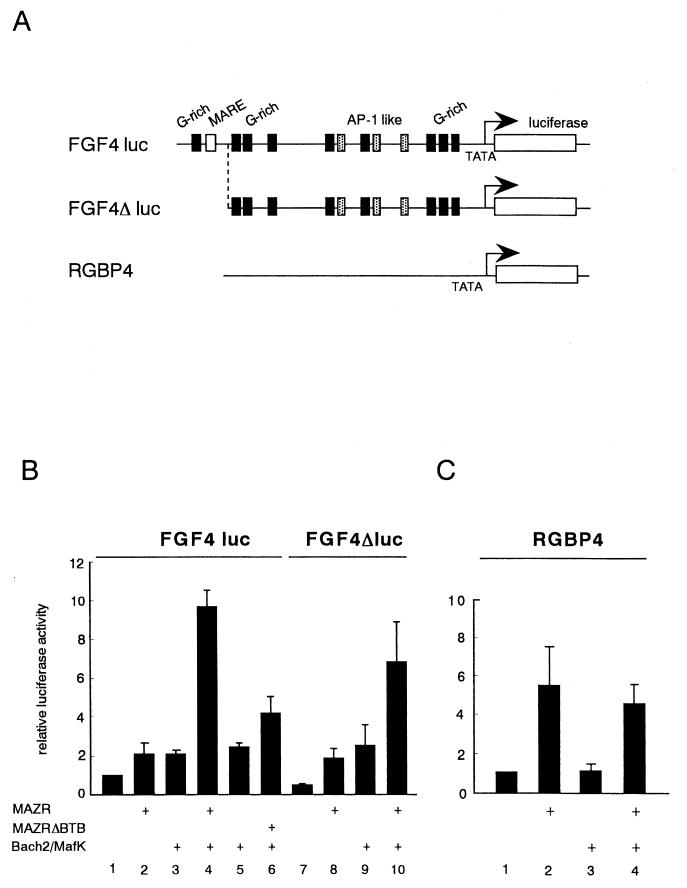

The above results suggest that a target gene(s) regulated by MAZR and Bach2 would contain both the G-rich sequence and MARE in its regulatory region. We searched for genes with such regulatory sequences in the genomic database using Genetyx Mac software. Of several candidate genes (data not shown), the fgf4 gene was found to contain multiple putative MAZR-binding sites and a single MARE in its 5′ regulatory region (shown in Fig. Fig.9A).9A). It should be noted that FGF4 plays an important role in the development of limb buds, along with FGF2, -8, and -10 (29). The presence of these clustered binding sites, as well as the expression profiles (Fig. (Fig.3),3), provoked us to examine regulatory roles for MAZR and Bach2 in the expression of the fgf4 gene. The fgf4 gene reporter plasmid, which contains the 4,300-bp 5′ promoter fused to the luciferase gene, was created (Fig. (Fig.9A).9A). The fgf4 reporter plasmid was introduced into NIH3T3 cells along with expression plasmids of MAZR, Bach2, and its partner MafK. MAZR alone or Bach2 or MafK alone slightly activated the expression of the reporter. In the presence of the Bach2-MafK complex, MAZR enhanced the reporter gene expression synergistically (Fig. (Fig.9B,9B, lane 4). This enhancement was diminished by deletion of the BTB/POZ domain of MAZR (MAZRΔBTB) (Fig. (Fig.9B,9B, lane 6), indicating that this synergistic effect was mediated through the BTB/POZ domain of MAZR. Deletion of the G-rich site and MARE in the 5′ terminal end of the fgf4 gene promoter (FGF4Δluc) (Fig. (Fig.9A)9A) slightly reduced the synergistic activity between MAZR and Bach2 (Fig. (Fig.9B,9B, right panel). Such synergism between MAZR and Bach2 was not observed with the pRGBP4 reporter plasmid (16) which contains only a minimal TATA box promoter (Fig. (Fig.7C).7C). Taken together, these data indicated that a complex generated between MAZR and Bach2 functions as an activator of the fgf4 gene promoter. Transcription activation by the MAZR-Bach2 complex is in clear contrast to functions of other BTB/POZ proteins, most of which repress transcription (8, 12, 27).

MAZR and Bach2 synergistically transactivate expression of the fgf4 gene. (A) Schematic structure of the fgf4 gene reporters and pRGBP4 (16), which served as a negative control. (B and C) MAZR, Bach2, and MafK expression plasmids (0.5 μg each) were transfected into NIH 3T3 cells along with pFGF4luc and pFGF4Δluc reporters (B) or the pRBGP4 reporter (C) (1 μg each) in the combinations indicated. The results are the means of three experiments.

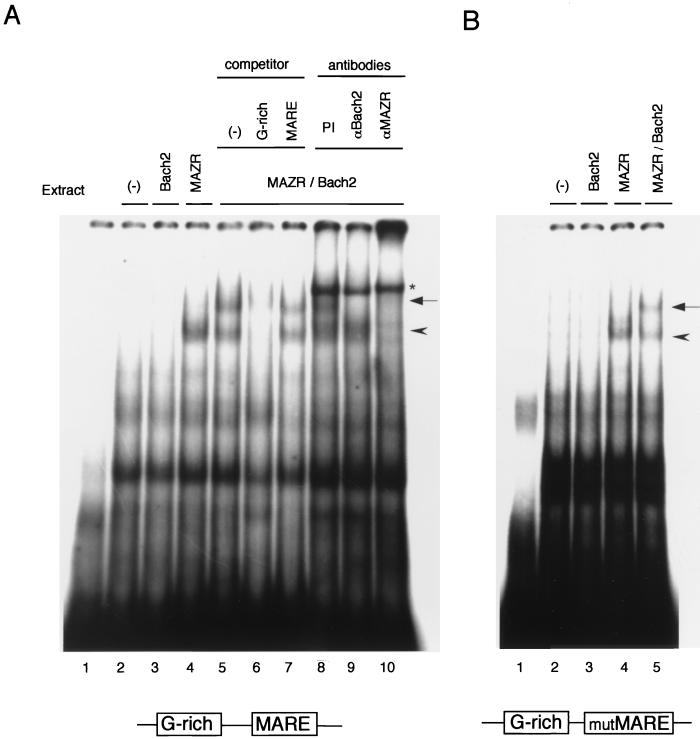

The synergistic activation of the FGF4Δluc reporter by MAZR and Bach2 (Fig. (Fig.9B)9B) could point to two mechanisms. First, three AP-1-like sites in the fgf4 promoter (dotted boxes shown in Fig. Fig.9A)9A) may compensate for loss of the MARE because Bach2 can recognize an AP-1 site (36). Second, only G-rich elements might be sufficient to recruit Bach2 onto DNA, resulting in the synergistic activation. To test the second possibility, we investigated an interaction between MAZR and Bach2 on DNA by EMSA. The oligonucleotide probe contained both a G-rich element and a MARE (Materials and Methods). Each factor was transiently expressed in 293T cells and subjected to EMSA.

As shown in Fig. Fig.10A,10A, MAZR bound to the probe efficiently, whereas Bach2 did not bind under the conditions examined (Fig. (Fig.10A,10A, lanes 3 and 4). Binding of MAZR was competed with a cold oligonucleotide DNA containing only a G-rich site (Fig. (Fig.10A,10A, lanes 5 and 6), verifying its site-specific binding. Coexpression of MAZR and Bach2 resulted in formation of another distinct band with slower mobility (Fig. (Fig.10A,10A, lane 5). Formation of this complex was inhibited by specific antibodies against Bach2 or MAZR (Fig. (Fig.10A,10A, lanes 9 and 10), showing that it contained both MAZR and Bach2. This complex was specifically competed out by a cold G-rich oligonucleotide but not by a MARE oligonucleotide (Fig. (Fig.10A,10A, lanes 6 and 7) (molar excess, 100-fold). Furthermore, an interaction between MAZR and Bach2 on DNA was also observed in EMSA using a probe which contained the G-rich site and a mutated MARE (Fig. (Fig.10B).10B). Taken together, these results indicated that Bach2 associated with MAZR on a G-rich site of probe DNA and that MARE is not critical for their association.

Association between MAZR and Bach2 on DNA. (A) EMSA was carried out with the oligonucleotide probe containing both the G-rich element and the MARE. Lane 1, empty; lane 2, mock transfection; lanes 3 through 10, whole-cell extracts from 293T cells transiently expressing Bach2 (lane 3), MAZR (lane 4), and MAZR and Bach2 (lanes 5 to 10) were prepared and subjected to EMSA. Cold competitor DNAs, containing either G-rich site or MARE (lanes 6 and 7, respectively), were added at 100-fold molar excess prior to addition of the radiolabeled probe. The antibodies used were a control preimmune (PI) rabbit serum (lane 8), anti-Bach2 (lane 9), and anti-MAZR (lane 10). The asterisk indicates an unknown binding complex in rabbit serum. (B) EMSA of whole-cell extracts of 293T cells expressing neither Bach2 nor MAZR (lane 2), Bach2 (lane 3), MAZR (lane 4), or Bach2 and MAZR (lane 5) was carried out with the oligonucleotide probe carrying the G-rich element and the mutated MARE. Lane 1 was empty. The arrowheads and the arrows indicate MAZR and MAZR-Bach2 complexes, respectively.

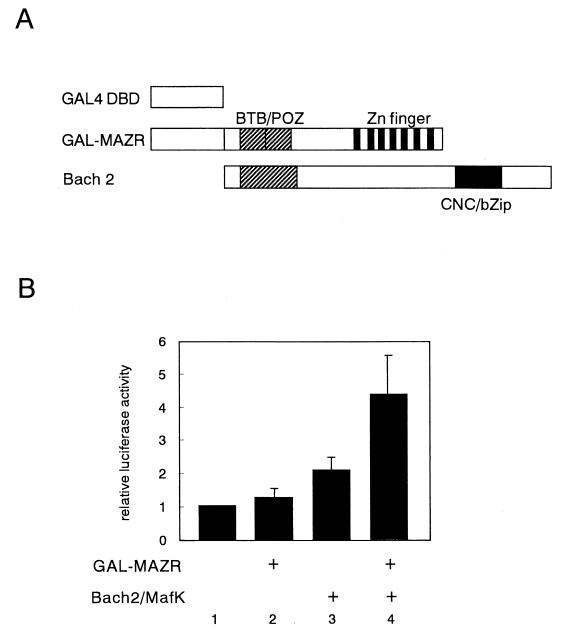

To evaluate transcriptional activity of MAZR-Bach2 complex, we carried out a mammalian two-hybrid assay (Fig. (Fig.11).11). When expressed individually, GAL-MAZR showed no effect on the GAL4-dependent reporter gene expression, but GAL-Bach2 repressed transcription. Thus, these two factors lacked transcription activation potential on their own. However, simultaneous expression of the GAL-MAZR and nonfusion Bach2 resulted in activation, indicating that MAZR-Bach2 complex acquired transactivation activity.

Mammalian two-hybrid assay revealing transcriptional activity of MAZR-Bach2 complex. (A) GAL4 fusion and nonfusion factors used in the assay. (B) Expression plasmids (1 μg) were introduced into 18-81 cells in the combinations indicated along with pG4TATAluc reporter (1 μg) and pEF-SP (0.25 μg) as an internal control.

DISCUSSION

The BTB/POZ domain appears to play diverse roles in mediating interactions among proteins that are involved in transcription regulation, chromatin structures, and cytoskeleton organization. In this study, we have identified a new BTB/POZ transcription factor, MAZR, which interacts with Bach2 through respective BTB/POZ domains. The significance of the results is twofold. First, MAZR was found to be a strong transactivator of c-myc promoter whose activity was independent of the presence of a transcription activation domain. Second, Bach2, which has been regarded as a transcription repressor, functions as a part of the transcription activating complex on certain promoters like the fgf4 gene by interacting with MAZR. Protein-protein interaction mediated by the BTB/POZ domain was shown to play critical roles in both of the two aspects.

An increasing number of BTB/POZ proteins have been identified and characterized; most of these proteins form homo- and/or hetero-oligomers through their BTB/POZ domains (4, 41). However, the significance of such interactions in transcription regulation has remained unclear. Isolation of MAZR allowed us to address this issue. The results of quantitative two-hybrid assays and EMSA showed that MAZR regulates gene expression as both homomeric and heteromeric complexes (Table (Table11 and Fig. Fig.10).10). The central question raised by the present results is how MAZR activated transcription in the absence of transcription activation domain. Considering the recent reports regarding BTB/POZ domain proteins, one of the interesting possibilities is that MAZR functions as an architectural transcription factor. One of the most-characterized BTB/POZ domain proteins is Drosophila GAGA factor. GAGA factor binds to regulatory DNA sequences that contain multiple GAGA sites by generating multimers through its BTB/POZ domain. Electron microscopy observations revealed that target DNAs wrap around such a GAGA multimer (21), indicating its structural role in gene regulation. Another interesting example in this line is Bach1. Bach1-MafK heterodimer generates a higher-order complex through the BTB/POZ domain of Bach1 (17, 42). This resulting higher-order complex binds to target DNA sequences with multiple MAREs, generating DNA loops (42). These observations suggest that BTB/POZ domain transcription factors regulate transcription as architectural factors (42). In this sense, it should be noted that both c-myc and fgf4 promoters contain multiple potential target sites for MAZR. Thus, it is highly likely that binding of multimers of MAZR can generate topological changes within the promoter regions. The observed dependence on the BTB/POZ domain is consistent with this idea. Structural changes induced by binding of architectural factors may directly or indirectly lead to activation of transcription.

The role of Bach2 as an integral part of the activating complex on the fgf4 promoter was unexpected because previous results implicated Bach2 as a transcriptional repressor. For example, Bach2 represses expression of the IgH gene through MARE in its 3′ enhancer in B cells (32). The mechanistic role for Bach2 in the transactivating complex is still unknown. One possibility is that Bach2 carries a transcription activation domain whose activity is manifested under specific contexts. This is supported by the fact that the GBD-Bach2/bZip fusion protein induced LacZ activity in yeast cells (Table (Table1).1). The results of a mammalian two-hybrid assay (Fig. (Fig.11)11) are also consistent with this idea. Alternatively, binding of Bach2 to MAZR may induce further structural changes of regulatory regions as suggested above. Of course, these two possibilities are not mutually exclusive and further analysis is required to understand the detailed mechanism. Thus far, most of the BTB/POZ domain transcription factors have been found to repress transcription (8, 12, 27). However, the results presented here suggest that some of them may also participate in transcription activation by interacting with other factors through BTB/POZ domains.

c-myc plays important roles in cell proliferation and differentiation. As such, its expression must be tightly regulated. Regulation of c-myc occurs at multiple levels, including initiation and termination of transcription, and attenuation of transcription. MAZ is implicated in repression of the c-myc gene (19). There are several transcription factors, such as β-catenin–Tcf-4 complex, that activate the c-myc expression (15). Our results, including high levels of expression observed in hematopoietic tissues, suggest MAZR is a candidate for activators of c-myc in hematopoietic cells. Because MAZR and MAZ possess similar Zn fingers and DNA recognition specificities, c-myc may be regulated by competing activities of transcription factors that target similar cis-DNA elements. Competition between MAZ and MAZR is expected to confer strict regulation of gene expression. Previous reports indicated that the ME1a1 and ME1a2 elements are the target of MAZ (19, 25). However, our results suggest that MAZR regulates transcription through binding to other G-rich elements scattered within the promoter region as well. Further studies are necessary to identify critical sites for MAZR and/or MAZ effects. In any case, the involvement of BTB/POZ-Zn finger proteins in development and cancer (2) makes MAZR an interesting candidate for being an upstream regulator of the c-myc gene.

The observed synergistic activity of MAZR and Bach2 appears biologically relevant. Besides B lymphoid cells, we found by whole-mount in situ hybridization that Bach2 and MAZR are coexpressed in limb buds of 10.5-dpc mouse embryos (Fig. (Fig.3).3). The limb development requires a complex program of events which is directed by a number of signaling molecules, such as FGFs and Sonic hedgehog, whose expressions are under strict regulation (29). The present results suggest that gene regulation in limb buds utilizes a combinatorial code of Bach2 and MAZR. One of the potential targets in limb buds is fgf4. However, these two proteins are not the sole determinants of fgf4 expression, since Bach2 and MAZR are expressed outside the AER as well.

If a combinatorial usage of BTB/POZ domain transcription factors is widespread among higher eukaryotes, BTB/POZ domains will shed a novel light on cancer etiology. Several BTB/POZ transcription factors have been implicated in malignant transformation (9, 41). Ectopic expression (e.g., BCL6) or generation of fusion proteins (e.g., PLZF) of BTB/POZ domain factors could negatively influence some important combinatorial codes of transcription factors within a cell, resulting in deregulated gene expression. Because of its potential involvement in c-myc regulation, MAZR is an interesting candidate for being a target in hematopoietic cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank K. Yokoyama (RIKEN) for plasmids and discussion, G. Martin (University of California) for plasmids, and T. Tanaka (Tsukuba University) for discussion. We also thank K. Furuyama for database searching, R. Matano for preparation of an antibody, and M. Mochita for construction of plasmids.

This work was supported by grants-in-aid from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture, an RFTF grant from the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Sciences, and grants from Naito Foundation, Uehara Memorial Foundation (to K.I.), Mochida Memorial Foundation, and Yamanouchi Foundation for Research on Metabolic Disorders (to A.K.).

REFERENCES

Articles from Molecular and Cellular Biology are provided here courtesy of Taylor & Francis

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.20.5.1733-1746.2000

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc85356?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Article citations

Binding to the Other Side: The AT-Hook DNA-Binding Domain Allows Nuclear Factors to Exploit the DNA Minor Groove.

Int J Mol Sci, 25(16):8863, 14 Aug 2024

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 39201549 | PMCID: PMC11354804

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

POZ/BTB and AT hook containing zinc finger 1 (PATZ1) suppresses differentiation and regulates metabolism in human embryonic stem cells.

Int J Biol Sci, 20(4):1142-1159, 21 Jan 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38385086 | PMCID: PMC10878140

Sibling rivalry among the ZBTB transcription factor family: homodimers versus heterodimers.

Life Sci Alliance, 5(11):e202201474, 12 Sep 2022

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 36096675 | PMCID: PMC9468604

Knockdown of ZBTB11 impedes R-loop elimination and increases the sensitivity to cisplatin by inhibiting DDX1 transcription in bladder cancer.

Cell Prolif, 55(12):e13325, 26 Aug 2022

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 36054300 | PMCID: PMC9715355

PATZ1 (MAZR) Co-occupies Genomic Sites With p53 and Inhibits Liver Cancer Cell Proliferation via Regulating p27.

Front Cell Dev Biol, 9:586150, 01 Feb 2021

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 33598459 | PMCID: PMC7882738

Go to all (77) article citations

Other citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Nucleotide Sequences (2)

- (3 citations) ENA - AC005003

- (1 citation) ENA - AB029397

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Bach proteins belong to a novel family of BTB-basic leucine zipper transcription factors that interact with MafK and regulate transcription through the NF-E2 site.

Mol Cell Biol, 16(11):6083-6095, 01 Nov 1996

Cited by: 412 articles | PMID: 8887638 | PMCID: PMC231611

The LAZ3/BCL6 oncogene encodes a sequence-specific transcriptional inhibitor: a novel function for the BTB/POZ domain as an autonomous repressing domain.

Cell Growth Differ, 6(12):1495-1503, 01 Dec 1995

Cited by: 82 articles | PMID: 9019154

Novel BTB/POZ domain zinc-finger protein, LRF, is a potential target of the LAZ-3/BCL-6 oncogene.

Oncogene, 18(2):365-375, 01 Jan 1999

Cited by: 88 articles | PMID: 9927193

Orchestration of plasma cell differentiation by Bach2 and its gene regulatory network.

Immunol Rev, 261(1):116-125, 01 Sep 2014

Cited by: 52 articles | PMID: 25123280

Review