Abstract

Objectives:

Medications for opioid use disorder (MOUDs) like buprenorphine are a first-line treatment for individuals who have opioid use disorder (OUD); however, these medications are not designed to impact the use of other classes of drugs. This descriptive study provides up-to-date information about non-opioid substance use among patients who recently initiated office-based buprenorphine treatment for OUD using data from two ongoing clinical trials.

Methods:

The study sample was comprised of 257 patients from six federally qualified health centers in the mid-Atlantic region who recently (i.e., within the past 28 days) initiated office-based buprenorphine treatment between July 2020 and May 2022. Following the screening and informed consent processes, participants completed a urine drug screen (UDS) and psychosocial interview as a part of the study baseline assessment. Descriptive analyses were performed on UDS results to identify the prevalence and types of substances detected.

Results:

Over half of participants provided urine specimens that were positive for non-opioid substances, with marijuana (37%; n = 95), cocaine (22%; n = 56), and benzodiazepines (11%; n = 28) detected with the highest frequencies.

Conclusions:

A significant number of participants used non-opioid substances after initiating buprenorphine treatment, suggesting that some patients receiving MOUDs could potentially benefit from adjunctive psychosocial treatment and supports to address their non-opioid substance use.

Keywords: opioid use disorder, buprenorphine, medications for opioid use disorder, polysubstance use

Introduction

The opioid epidemic continues to plague this country with rates of opioid use, overdoses, and overdose deaths increasing substantially in recent years. Opioids were involved in 80,725 overdose deaths in 2021 with synthetic opioids including fentanyl present in 88% of these cases.1 Fortunately, medications for opioid use disorder (MOUDs) including buprenorphine, methadone, and naltrexone exist and are the standard of care for opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment.2,3,4 Buprenorphine and methadone have been shown to substantially lower overdose risk and reduce emergency department utilization and hospitalizations.5 Unlike methadone, buprenorphine may be provided in office-based settings.

MOUDs including buprenorphine are designed to address opioid use. Consequently, they have little impact on other types of drug use. Several studies of patients receiving buprenorphine for OUD have shown polysubstance use to negatively impact outcomes including retention and opioid abstinence.6,7,8,9 Furthermore, it can produce dangerous drug interactions.4 Although there is much debate around when and even if adjunctive psychosocial treatment may be warranted,10,11 it is likely that some individuals receiving MOUDs may benefit from additional psychosocial services to address their non-opioid substance use.

This brief report provides up-to-date information about the prevalence of other drug use among patients recently initiating office-based buprenorphine treatment for OUD. Using urine drug screen (UDS) results from two ongoing studies, it reports on the prevalence and types of non-opioid substances detected along with the prevalence of current opioid use (excluding buprenorphine).

Methods

Participants

The sample was comprised of 257 participants enrolled in two ongoing clinical trials examining the impact of providing psychosocial support (i.e., cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and/or peer support) to patients who recently initiated office-based buprenorphine treatment for OUD. Inclusion criteria and recruitment procedures were the same for both studies, but they differed in how the psychosocial interventions were delivered with one employing a 2×2 factorial design and one using an adaptive approach to deliver the two interventions. Participants were recruited from six federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) in the mid-Atlantic region between July 2020 and May 2022. To be eligible for participation, individuals had to have begun this episode of office-based buprenorphine treatment within the past 28 days, have moderate to severe OUD as indicated by the provider in the clinical record, and not require an inpatient level of care.

Individuals who met the inclusion criteria were informed about the study opportunity by their healthcare provider. Interested individuals then met with the onsite research assistant who provided a study overview, screened them for eligibility, and walked them through the informed consent process. After providing informed consent, participants completed a comprehensive baseline psychosocial assessment that included the Addiction Severity Index 5th Edition-Lite (ASI-5 Lite12) and provided a urine specimen. The baseline assessment took between 45 minutes to one hour to complete and participants received $40 remuneration. Each study was overseen by the Institutional Review Board of the lead organization (i.e., Public Health Management Corporation and Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine).

Measures

Self-reported demographic (age, race, gender identity, ethnicity) and substance use history variables (current and lifetime polysubstance use [days/years used more than one substance including alcohol in past 30/lifetime], opioid overdose history) were obtained from the general and drug sections of the ASI-5 Lite. Use of 13 substances [i.e., amphetamines, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, buprenorphine, cocaine, ecstasy, fentanyl, marijuana, methadone/metabolites, methamphetamine, opiates, oxycodone, and phencyclidine (PCP)] was determined using Identify Diagnostics USA® CLIA-waived 14-panel test cups and fentanyl testing strips.

Variable definitions and analysis

Variables were created to reflect (1) substance detection for each of the 8 non-opioid substances (i.e., amphetamines, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, cocaine, ecstasy, marijuana, methamphetamine, PCP), (2) detection of any of the 8 non-opioid substances, and (3) the number of non-opioid substances detected. In addition, a variable was created to reflect any opioid use (i.e., fentanyl, methadone/metabolites, opiates, oxycodone)—this variable definition excludes buprenorphine as it was prescribed for all participants. Importantly, substances for which the participant had been prescribed (including medical marijuana) were not considered drug-positive. Descriptive statistics were calculated for the self-report and urinalysis-related variables described above.

Results

Participants were 43.2 years of age on average (SD = 11.2) and the majority identified as male (66%; n = 169), Black (39%; n = 100) or White (38%; n = 96), and not Hispanic/Latino (76%; n = 196). They reported 5.5 days (SD = 9.3) of polysubstance use in the past month and 9 years (SD = 10.5) of polysubstance use, on average. Almost half (46%; n = 116) had experienced an opioid overdose.

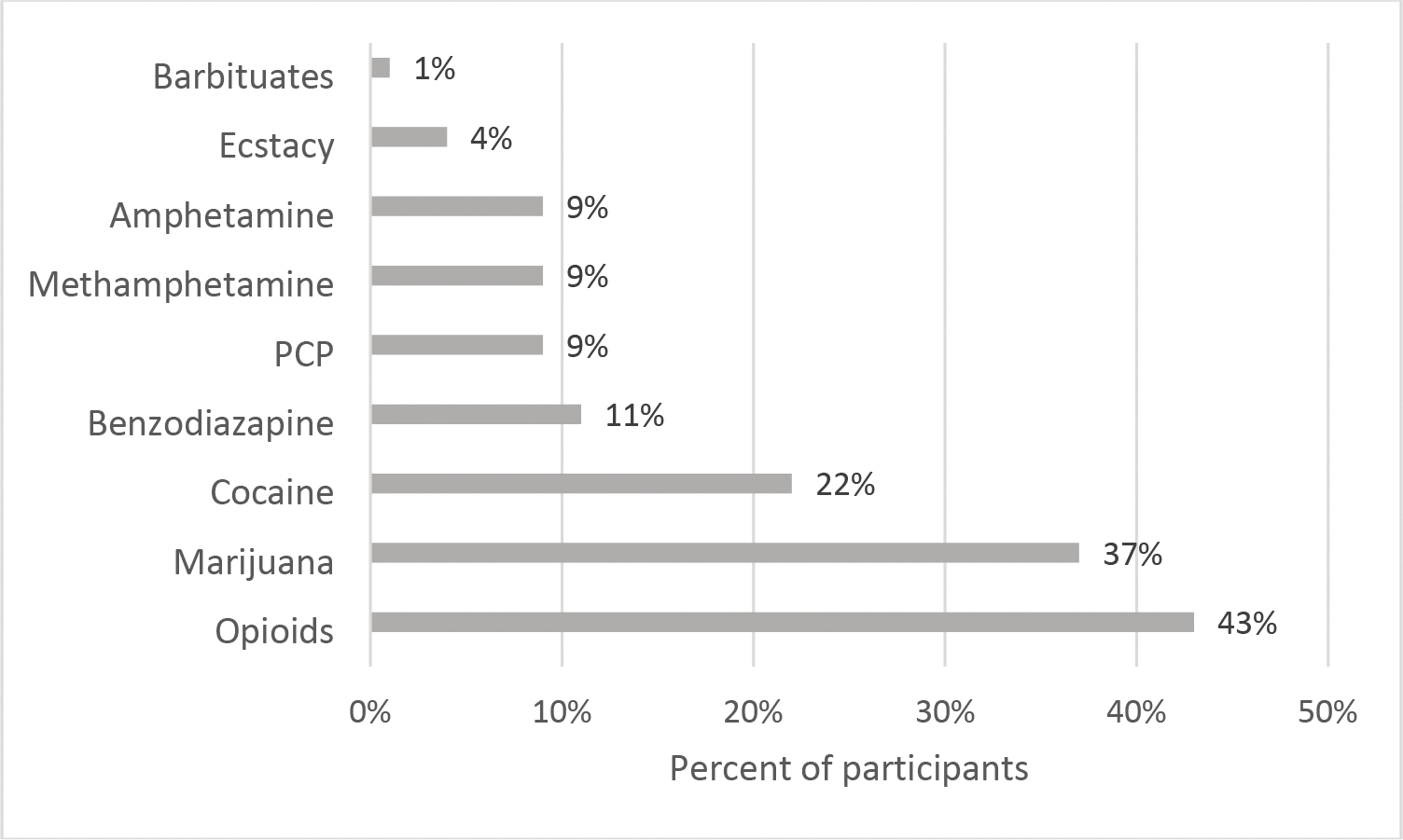

Over half of participants in the sample (57%; n = 147) provided a urine specimen that was positive for at least one non-opioid substance. Thirty-seven percent (n = 94) of participants provided a urine specimen that was positive for non-opioid substances other than marijuana. As seen in Figure 1, the most frequently detected non-opioid substance was marijuana (37%; n = 95), followed by cocaine (22%; n = 56) and benzodiazepines (11%; n = 28).

Figure 1.

Percent of participants providing drug-positive urine specimen for each substance tested (n = 257).

Note: Opioids category excludes buprenorphine as all participants were prescribed the medication.

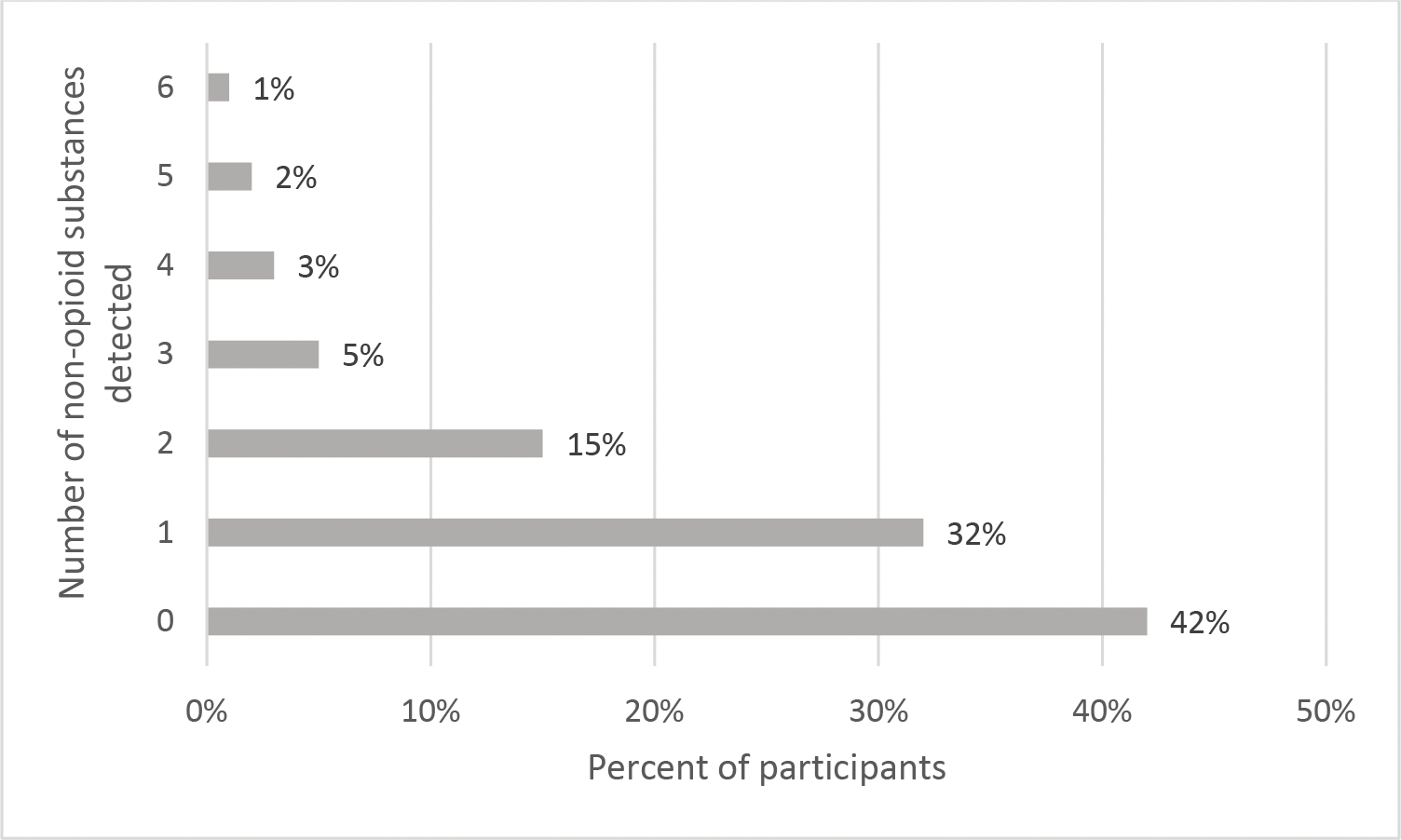

Figure 2 provides frequencies for the number of non-opioid substances detected. As can be seen, 32% (n = 82) of the participants provided a urine specimen that was positive for one non-opioid drug, 15% (n = 39) for two non-opioid drugs, and 10% (n = 26) for three or more non-opioid drugs. Excluding marijuana, 21% (n = 55) of participants provided a urine specimen that was positive for one non-opioid drugs, 7% (n =18) for two non-opioid drugs, and 8% (n = 21) for three or more non-opioid drugs.

Figure 2.

Number of non-opioid substances detected in urine specimen (n = 257).

Excluding buprenorphine, 42% (n = 108) of participants provided UDS that was positive for fentanyl and/or other opioids (i.e., opioids/heroin, oxycodone, methadone). Positivity percentages were 12% (n = 30) for other opioids excluding fentanyl, 9% (n = 23) for fentanyl only, and 21% (n = 55) for both fentanyl and other opioids.

Discussion

Findings indicated that the majority of FQHC patients who recently initiated office-based buprenorphine treatment for OUD provided a urine specimen that was positive for at least one non-opioid substance. Marijuana, cocaine, and benzodiazepines were the non-opioid substances detected with the highest frequency. It is important that providers consider other substance use in developing treatment plans for patients. Because MOUDs are not designed to reduce non-opioid drug use, individuals on MOUDs who use non-opioid substances may require additional psychosocial supports to address their polysubstance use, including CBT or contingency management (CM) which have been found to be effective in reducing cocaine and other substance use.13,14

This report has several limitations. First, it relies on results from a single point of care urine and does not provide a measure problem severity. As such, a positive result may not be an indicator of problematic use. Second, participants were recruited from the same geographic area which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Finally, it is possible that some positive UDS results may represent false positives triggered by other medications the participant had taken.15

Conclusions

Additional research is necessary to better understand how non-opioid substance use adversely affects treatment outcomes in buprenorphine patients. Furthermore, studies of this nature could shed light on when additional psychosocial supports may be warranted within the context of MOUDs and which types of treatment (e.g., CBT, CM, peer support) may best address non-opioid drug use.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the late Dr. David S. Festinger who was instrumental in conceptualizing and carrying out this work and thank our participants, study sites, and research staff.

Supported by grants from the Pennsylvania Department of Health SAP#4100083338 and Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute Contract #OBOT-2018C2–13158

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ahmad FB, Cisewski JA, Rossen LM, Sutton P. Provisional drug overdose death counts. National Center for Health Statistics. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kampman K, Jarvis M. American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) National Practice Guideline for the Use of Medications in the Treatment of Addiction Involving Opioid Use. J Addict Med. 2015;9(5):358–367. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Clinical Guidelines for the Use of Buprenorphine in the Treatment of Opioid Addiction. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uchtenhagen A Guidelines for the Psychosocially Assisted Pharmacological Treatment of Opioid Dependence. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wakeman SE, Larochelle MR, Ameli O, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Different Treatment Pathways for Opioid Use Disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1920622. Published 2020 Feb 5. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sullivan LE, Moore BA, O’Connor PG, et al. The association between cocaine use and treatment outcomes in patients receiving office-based buprenorphine/naloxone for the treatment of opioid dependence. Am J Addict. 2010;19(1):53–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2009.00003.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simon CB, Tsui JI, Merrill JO, Adwell A, Tamru E, Klein JW. Linking patients with buprenorphine treatment in primary care: Predictors of engagement. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;181:58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsui JI, Mayfield J, Speaker EC, et al. Association between methamphetamine use and retention among patients with opioid use disorders treated with buprenorphine. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020;109:80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haddad MS, Zelenev A, Altice FL. Integrating buprenorphine maintenance therapy into federally qualified health centers: real-world substance abuse treatment outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1–2):127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dugosh K, Abraham A, Seymour B, McLoyd K, Chalk M, Festinger D. A Systematic Review on the Use of Psychosocial Interventions in Conjunction with Medications for the Treatment of Opioid Addiction. J Addict Med. 2016;10(2):93–103. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwartz RP. When Added to Opioid Agonist Treatment, Psychosocial Interventions do not Further Reduce the Use of Illicit Opioids: A Comment on Dugosh et al. J Addict Med. 2016;10(4):283–285. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cacciola JS, Alterman AI, McLellan AT, Lin YT, Lynch KG. Initial evidence for the reliability and validity of a “Lite” version of the Addiction Severity Index. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87(2–3):297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McPherson SM, Burduli E, Smith CL, et al. A review of contingency management for the treatment of substance-use disorders: adaptation for underserved populations, use of experimental technologies, and personalized optimization strategies. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2018;9:43–57. Published 2018 Aug 13. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S138439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rawson RA, Huber A, McCann M, et al. A comparison of contingency management and cognitive-behavioral approaches during methadone maintenance treatment for cocaine dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(9):817–824. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.9.817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kale N Urine drug tests: ordering and interpreting results. Am Fam Physician. 2019; 99(1), 33–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]