Abstract

Ring A (3-dimethylallyl-4-hydroxybenzoic acid) is a structural moiety of the aminocoumarin antibiotics novobiocin and clorobiocin. In the present study, the prenyltransferase involved in the biosynthesis of this moiety was identified from the clorobiocin producer (Streptomyces roseochromogenes), overexpressed, and purified. It is a soluble, monomeric 35-kDa protein, encoded by the structural gene cloQ. 4-Hydroxyphenylpyruvate and dimethylallyl diphosphate were identified as the substrates of this enzyme, with Km values determined as 25 and 35 μM, respectively. A gene inactivation experiment confirmed that cloQ is essential for ring A biosynthesis. Database searches did not reveal any similarity of CloQ to known prenyltransferases, and the enzyme did not contain the typical prenyl diphosphate binding site (N/D)DXXD. In contrast to most of the known prenyltransferases, the enzymatic activity was not dependent on the presence of magnesium, and in contrast to the membrane-bound polyprenyltransferases involved in ubiquinone biosynthesis, CloQ did not accept 4-hydroxybenzoic acid as substrate. CloQ and the similar NovQ from the novobiocin producer seem to belong to a new class of prenyltransferases.

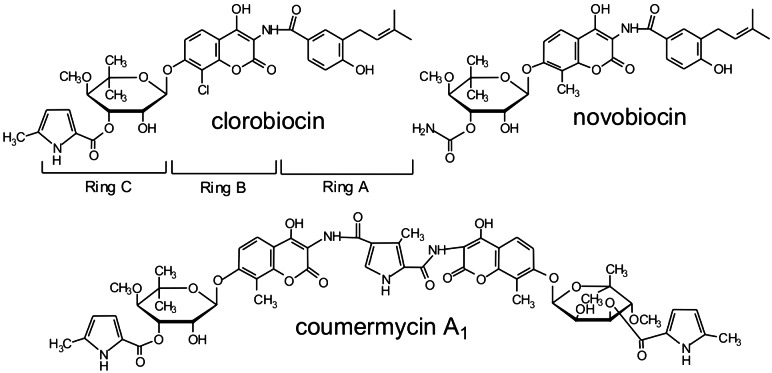

Aminocoumarin antibiotics (Fig. 1) are very potent inhibitors of bacterial DNA gyrase (1). Novobiocin (Albamycin, Pharmacia–Upjohn) is licensed as an antibiotic for human therapy. Novobiocin, clorobiocin, and coumermycin A1 are formed by different Streptomyces strains (2, 3). The 3-prenylated 4-hydroxybenzoic acid (4HB) moiety of novobiocin (called ring A) has been shown to be derived from tyrosine and an isoprenoid precursor (4), but conflicting suggestions have been made for the prenylation substrate (5–8). 3-Prenylated 4HB moieties are known as intermediates in the biosynthesis of ubiquinones (9, 10) and shikonin (11), where they are formed from 4HB under catalysis of membrane-bound prenyltransferases. These enzymes contain the characteristic prenyl diphosphate binding site [(N/D)DXXD] known from trans-prenyltransferases (12, 13). Surprisingly, cloning of the novobiocin and the clorobiocin biosynthetic gene clusters (14, 15) revealed neither a gene with sequence similarity to known prenyltransferases nor genes that could be assigned to 4HB biosynthesis, e.g., similar to the benzoate biosynthesis genes recently described in Streptomyces maritimus (16).

Figure 1.

Structures of the aminocoumarin antibiotics.

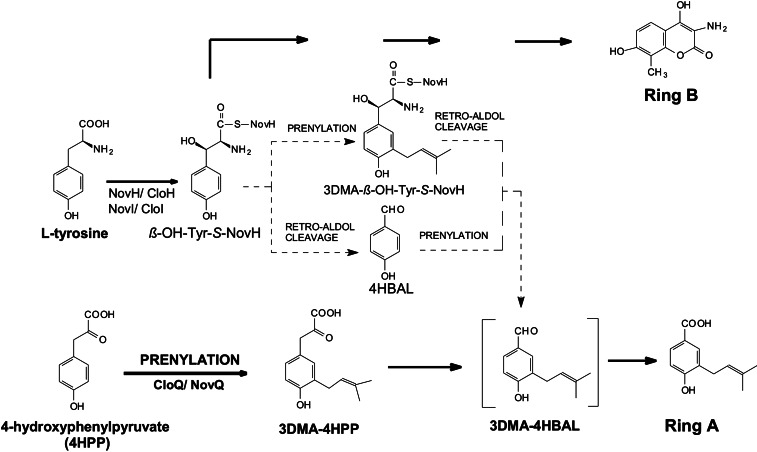

A hypothesis for the formation of ring A was derived from studies on the biosynthesis of the aminocoumarin moiety (ring B) of novobiocin. Chen and Walsh (7) showed that the first two steps in ring B formation are the activation of L-tyrosine by NovH and the subsequent hydroxylation to β-hydroxytyrosyl-NovH (β-OH-Tyr-S-NovH) under catalysis of the cytochrome P450 enzyme NovI (Fig. 2). Alkali treatment of this product led to the formation of 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde (4HBAL), resulting from a retro-aldol cleavage of β-OH-Tyr-S-NovH. It therefore seemed possible that ring A of novobiocin may also be derived from β-OH-Tyr-S-NovH by a retro-aldol reaction, occurring either before or after prenylation of the aromatic nucleus (Fig. 2). Further support for this hypothesis came from the detection of the genes novR and cloR in the biosynthetic gene clusters of novobiocin and clorobiocin, respectively, as their gene products show similarity to aldolases, and the involvement of cloR in ring A biosynthesis was proven by a gene inactivation experiment in the clorobiocin producer (15).

Figure 2.

Possible biosynthetic pathways to the prenylated 4HB moiety (ring A) of novobiocin and clorobiocin.

The present study revealed, however, that ring A and ring B are formed by two distinct and independent pathways. CloQ was identified as a soluble aromatic prenyltransferase, which prenylates 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate (4HPP) in clorobiocin biosynthesis. CloQ was found to be dissimilar to most prenyltransferases described so far and may indicate the existence of a new class of prenyltransferases.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Radiochemicals.

[1-14C]Dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) and L-[U-14C]tyrosine were obtained from Moravek Biochemicals (Brea, CA). β-Hydroxy-L-tyrosine and unlabeled DMAPP were kindly provided by K.-H. van Pée (Institut für Biochemie, Dresden, Germany) and K. Yazaki (Wood Research Institute, Kyoto), respectively. 3-dimethylallyl (3DMA)-4HBAL was synthesized as described in ref. 17. Ring A of novobiocin (3-dimethylallyl-4-hydroxybenzoic acid) was prepared as described in ref. 18. Ring B of novobiocin (3-amino-4,7-dihydroxy-8-methylcoumarin) was kindly provided by Pharmacia–Upjohn.

Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions.

Streptomyces roseochromogenes var. oscitans DS 12.976 was kindly provided by Aventis. Wild-type and mutant strains of S. roseochromogenes were cultured as described in ref. 15. Escherichia coli strains used were XL1 Blue MRF′ (Stratagene) and BL21(DE3) (Novagen).

DNA Manipulation.

DNA manipulations were carried out as described in refs. 19 and 20. Southern blot analysis was performed on Hybond-N membranes (Amersham Pharmacia) with digoxigenin-labeled probes by using the DIG high prime DNA labeling and detection kit II (Roche Applied Science).

Construction of In-Frame Deletion Mutants of S. roseochromogenes.

For in-frame deletion of cloQ in S. roseochromogenes, two fragments cloQ-1 (727 bp) and cloQ-2 (1,259 bp) were amplified. Primer pairs used were cloQ-1/HindIII (5′-GTGCGCGAAGCTTGGCCCCG-3′) and cloQ-1/PstI (5′-GAAGGCCTGCAGGACGGT-3′); and cloQ-2/PstI (5′-CACGACCTGCAGGCACTTCA-3′) and cloQ-2/BamHI (5′-ACCGGGGGATCCCCTGCAA-3′). Introduced restriction sites are underlined. The fragments were cloned into the corresponding sites of pBSKT (21), containing a thiostrepton-resistance gene, resulting in pFP04. Transformation of S. roseochromogenes with pFP04 and selection for mutants resulting from single- and double-crossover recombination events were carried out as described in ref. 15. Chromosomal DNA from wild type and mutants was digested with BamHI and PvuII and hybridized with a probe containing a part of the cloR gene immediately downstream of cloQ. A single band of 1.5 kb was detected in the wild type, whereas a single band of 2.9 kb was detected in the cloQ− mutant, confirming the in-frame deletion of cloQ.

For the in-frame deletion of cloI in S. roseochromogenes, two fragments, denoted cloI-1 (1,249 bp) and cloI-2 (1,013 bp), were amplified. Primer pairs used were cloI-1/HindIII (5′-CGGCCAAGCTTGCCACGATG-3′) and cloI-1/PstI (5′-GTACTCGGCCTGCAGAATCGG-3′); and cloI-2/PstI (5′-GCATCCTGCAGGGGATGAGC-3′) and cloI-2/XbaI (5′-GCCGGACTTCTAGATCCGTC-3′). As for pFP04, the two fragments cloI-1 and cloI-2 were cloned into pBSKT, resulting in pEW02. After transformation, single- and subsequently double-crossover mutants were obtained. Chromosomal DNA from wild type and mutants was digested with NcoI and hybridized with a 2-kb probe containing the cloI gene and the adjacent upstream and downstream region. A 2-kb band was detected in the wild type, whereas a 0.9-kb band was detected in cloI− mutant, confirming the in-frame deletion of cloI.

Feeding of the Mutants with Ring A, Ring B, and 3DMA-4HBAL.

The cloI− and cloQ− defective mutants were grown in 50 ml of preculture medium (15) supplemented with 1 mg of ring A or 1 mg of ring B of novobiocin. After 48 h, 5 ml of this preculture was inoculated into 50 ml of production medium (15), again supplemented with 1 mg of ring A or ring B. Another 1 mg of ring A or ring B was added after 2 days. After 7 days of cultivation, secondary metabolites were analyzed. The feeding of the cloQ defective mutant with 3DMA-4HBAL was done in the same way.

HPLC Analysis of Culture Extracts.

Bacterial culture was acidified to pH 4 with HCl and extracted twice with an equal volume of ethyl acetate. The solvent was evaporated and the residue was resuspended in 1 ml of methanol. Metabolites were analyzed by HPLC with a Multosphere RP18-5 column (250 × 4 mm, 5 μm) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. For analysis of clorobiocin and novclobiocin C102 production, a linear gradient of methanol (40–100%) in 1% aqueous formic acid was used, and elution was monitored at 340 nm. For the analysis of the accumulation of ring A by the cloI− mutant, a linear gradient of methanol (50–80%) in 1% aqueous formic acid was used, and elution was monitored at 254 nm.

The extracts were also analyzed by liquid chromatography (LC) using a Multosphere RP18-5 column (250 × 4 mm, 5 μm) at a flow rate of 100 μl/min, coupled to an electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrometer TSQ Quantum (ThermoFinnigan, San Jose, CA) in negative-ion mode under the addition of 10% ammonia (15 μl/min). A linear gradient of acetonitrile (30–100%) in 0.1% aqueous formic acid was used. The negative ion-ESI collision-induced dissociation (CID) mass spectrum of clorobiocin was as follows: (m/z) = 697/695 ([M − H]−), 588, 507, 226. The negative ion-ESI-CID mass spectrum of ring A was as follows: (m/z) = 205 ([M − H]−), 161, 106.

Overexpression of Holo-NovH and NovI Proteins.

The NovH construct pHC10 and the NovI construct pHC21 were described in ref. 7, and the phosphopantetheinyltransferase gene (sfp) cloned into pSU20 was described in ref. 22.

Holo-NovH was obtained by cotransformation of pHC10 and sfp/pSU20 into E. coli BL21(DE3). Cells were grown in LB medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin and 50 μg/ml chloramphenicol at 25°C to an OD600 of 0.4–0.6. After cooling to 15°C, they were further cultured at this temperature to an OD600 of 0.6–0.7 before induction with 50 μM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG). The cells were then allowed to grow for an additional 15 h at 15°C. Holo-NovH was subsequently purified as described in ref. 7. Expression of pHC21 in E. coli BL21(DE3) and purification of NovI were carried out as described in ref. 7.

Overexpression and Purification of CloQ Protein.

For construction of the plasmid cloQ-pGEX4T1, cloQ was amplified by using the primers cloQ-Nterm-BamHI (5′-GGAGGAAGTCGGATCCGCTCTCCCGATAGATC-3′) and cloQ-Cterm-XhoI (5′-AAGCCTCTCGAGTCGGGCACCTCCCATGGTC-3′). Introduced restriction sites are underlined. The product was digested with BamHI and XhoI and ligated into pGEX-4T-1 (Amersham Pharmacia) to give cloQ-pGEX4T1. E. coli BL21(DE3) cells were grown in 100 ml of LB medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml carbenicillin at 28°C until an OD600 of 0.6 was reached. Isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside was added to a final concentration of 1 mM. After 5 h, the cells were harvested by centrifugation and broken by using a French press (SLM-Aminco, Urbana, IL). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (30 min; 20,000 × g). Purification of CloQ as a glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein and subsequent cleavage of the GST tag by thrombin treatment were carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amersham Pharmacia) using glutathione Sepharose 4B and the batch method.

Protein Analysis.

Standard protein techniques were used as described in refs. 23 and 24. The molecular weight of native CloQ was determined by gel filtration on a HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 200 column that had been equilibrated with 50 mM Tris⋅HCl buffer (pH 8.0) containing 150 mM NaCl. The column was calibrated with dextran blue 2000 (2,000 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa), albumin (67 kDa), ovalbumin (43 kDa), and ribonuclease A (13.7 kDa) (Amersham Pharmacia).

Incubation of Holo-NovH, NovI, and CloQ with L-[U-14C]Tyrosine.

Holo-NovH was loaded with L-[U-14C]tyrosine at 24°C for 1.5 h in a reaction mixture (110 μl) that contained 75 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 2.5 μM L-[U-14C]tyrosine (500 Ci/mol; 1 Ci = 37 GBq), 3 mM ATP, 2 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, and 30 μg of NovH. Subsequently, NADPH and spinach ferredoxin (Sigma) were added to a final concentration of 1.5 mM and 5 μM, and 0.1 units of ferredoxin reductase (Sigma) and 25 μg of NovI were added. Incubation was continued for 2 h at 24°C. Then, 5 μg of CloQ and 1 mM DMAPP were added, and incubation was continued for 1 h at 30°C before quenching with 500 μl of 10% trichloroacetic acid. The precipitated proteins were pelleted by centrifugation, washed twice with 500 μl of distilled water, and redissolved in 100 μl of 0.1 M KOH. The tethered product was released from the carrier protein by incubating for 5 min at 60°C. The proteins were removed by acidifying the mixture with 5 μl of 50% trifluoroacetic acid followed by centrifugation. Product formation was analyzed by HPLC with a Multosphere RP18-5 column (250 × 4 mm, 5 μm) coupled to a radiodetector (Berthold, Bad Wildbad, Germany) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. A linear gradient of acetonitrile (0–100%) in 1% aqueous formic acid was used. A control incubation was carried out with denatured CloQ.

Assay for 4HPP Dimethylallyltransferase Activity.

For quantitative determination of enzyme activity, the reaction mixture (100 μl) contained 75 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.25 mM 4HPP, 0.5 mM DMAPP, and purified CloQ. After incubation for 10 min at 30°C, the reaction was stopped with 2 μl of formic acid. Products were analyzed by HPLC at 285 nm as described above. The same conditions were used for incubation with L-tyrosine, β-hydroxytyrosine, prephenic acid, 4HBA, and 4HBAL.

For radioactivity assays, 19 μM [1-14C]DMAPP (3.4 GBq/μmol) was used instead of unlabeled DMAPP. Otherwise, the incubation was carried out and terminated as described above, with an incubation time of 60 min. The reaction mixture was extracted twice with 500 μl of ethyl acetate. After evaporation, the residue was dissolved in 100 μl of ethanol. For the conversion of 3DMA-4HPP to 3DMA-4HBAL, 50 μl of the ethanolic solution was mixed with 50 μl of 1 M NaOH and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. The reaction was stopped with 10 μl of formic acid. The products were analyzed by HPLC as described above, using a radioactivity detector.

Mass Spectroscopic Analysis of the Reaction Product of 4HPP Dimethylallyltransferase.

The incubation mixture (500 μl) contained 75 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM 4HPP, 0.1 mM DMAPP, and 12.5 μg of CloQ and was incubated at 30°C for 1 h. The reaction was stopped with 5 μl of formic acid, and the mixture was extracted twice with 500 μl of ethyl acetate. After evaporation, the residue was dissolved in 60 μl of ethanol. A control incubation was carried out with denatured CloQ.

Product formation was analyzed by liquid chromatography coupled to an ESI mass spectrometer as described above. The negative ion-ESI-CID mass spectrum of 4HPP was as follows: m/z = 179 ([M − H]−), 135, 107. The negative ion-ESI-CID mass spectrum of 3DMA-4HPP was as follows: m/z = 247 ([M − H]−), 203, 175.

Analysis of Metal Content of CloQ.

Zinc was determined by using a Unicam atom absorption spectrometer. Magnesium was determined spectrophotometrically by using the Roche/Hitachi 902 clinical chemistry analyzer. Both the zinc and the magnesium contents were <0.1 mol per mol of CloQ.

Results

Inactivation of cloQ.

Sequence analysis of the gene clusters of novobiocin and clorobiocin (14, 15) did not reveal any genes with similarity to known prenyltransferases, nor genes containing the typical prenyl diphosphate binding site (N/D)DXXD (12). The identification of candidates for prenyltransferase genes was facilitated, however, by a comparison of the biosynthetic gene clusters of novobiocin (14), clorobiocin (15), and coumermycin A1 (25). The prenylated 4HB moiety (ring A) is present in novobiocin and clorobiocin but not in coumermycin A1 (Fig. 1). Correspondingly, three genes were found to be present in the novobiocin and the clorobiocin clusters but absent in the coumermycin A1 cluster: (i) the putative aldolase genes novR and cloR, which were proven to be involved in ring A biosynthesis (15); (ii) novF and cloF, with sequence similarity to prephenate dehydrogenase; and (iii) novQ and cloQ, which did not show any similarity to known genes in the database. If the prenyltransferases were contained within the clusters and were dissimilar to prenyltransferases described previously, novQ and cloQ would be candidate genes for these enzymes.

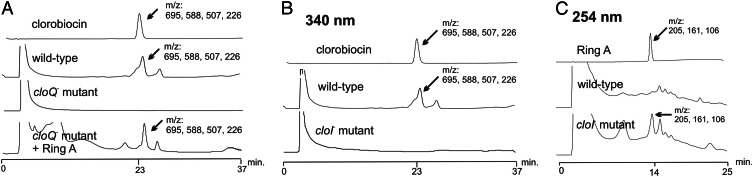

A gene inactivation experiment was therefore carried out with cloQ. To avoid polar effects on the genes downstream of cloQ, especially on cloR, an in-frame deletion of 810 bp within the coding sequence of cloQ was created, and the correct genotype of the mutant was confirmed by Southern blotting (see Materials and Methods). HPLC analysis of the culture extracts showed that clorobiocin production was abolished in the cloQ− mutant (Fig. 3A). However, on addition of ring A to the culture, the production of clorobiocin was restored to one-third of the wild-type level (Fig. 3A). This finding proved that cloQ is involved in ring A biosynthesis. 3DMA-4HBAL is a possible intermediate of ring A biosynthesis (Fig. 2). Adding this compound to cloQ− mutant culture proved to be equally as effective in restoring clorobiocin production as the addition of ring A (data not shown).

Figure 3.

HPLC analysis of culture extracts of the cloQ− and cloI− mutants. (A) Clorobiocin standard, wild type, cloQ− mutant, and cloQ− mutant fed with ring A. Detection was at 340 nm. The identity of clorobiocin ([M − H]− = 695) was confirmed by LC-ESI-CID. Mass spectroscopic fragments are indicated. (B) Clorobiocin standard, wild type, and cloI− mutant. Detection was at 340 nm. (C) Ring A standard, wild type, and cloI− mutant. Detection was at 254 nm. The identity of ring A ([M − H]− = 205) was confirmed by LC-ESI-CID. Mass spectroscopic fragments are indicated.

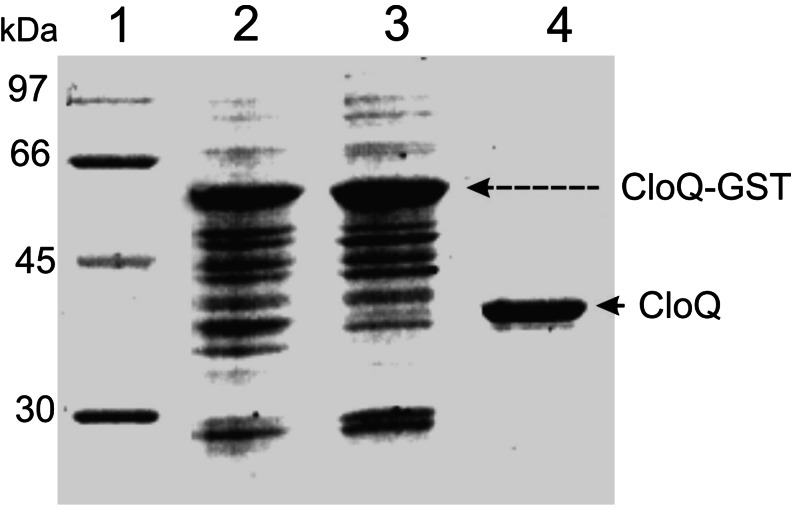

Expression and Purification of CloQ.

CloQ was expressed in E. coli as a soluble GST fusion protein of 61.6 kDa. After purification, GST was cleaved from CloQ by thrombin treatment and removed. This procedure resulted in apparently homogenous CloQ protein as judged by SDS/PAGE (Fig. 4). The observed molecular mass corresponded to the calculated mass (35.6 kDa). A protein yield of 6 mg of pure CloQ per liter of culture was obtained.

Figure 4.

Purification of CloQ after overexpression as a fusion protein with GST. The SDS/12% polyacrylamide gel was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Lane 1, molecular mass standards; lane 2, total protein after isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside induction; lane 3, soluble protein after induction; lane 4, eluate after thrombin treatment.

Investigation of 4HB, 4HBAL, and β-Hydroxytyrosyl-S-NovH (β-OH-Tyr-S-NovH) as Substrates of CloQ.

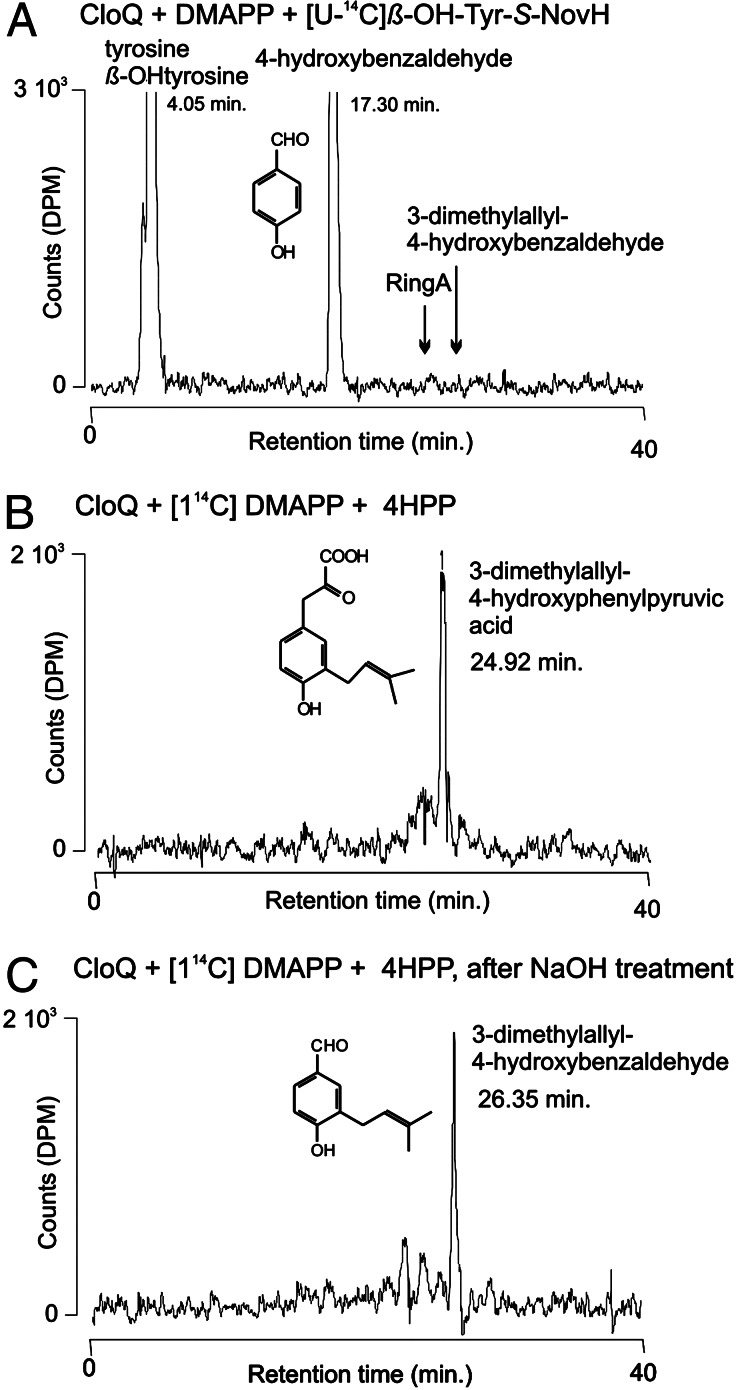

4HBAL can be formed from β-OH-Tyr-S-NovH by retro-aldol cleavage (7). Subsequent prenylation and oxidation may lead to the formation of ring A of novobiocin or clorobiocin (Fig. 2). However, when the purified CloQ protein was incubated with 4HBAL, or with the corresponding acid 4HB, in the presence of DMAPP and Mg2+, no prenylated products were observed. Alternatively, prenylation of β-OH-Tyr-S-NovH may precede the retro-aldol cleavage reaction in novobiocin and clorobiocin formation, rendering 3-dimethylallyl-β-hydroxytyrosine, in its enzyme-bound form, as an intermediate of ring A biosynthesis (Fig. 2). A natural product containing a 3-dimethylallyl-β-hydroxytyrosyl residue has been identified previously in a fungus (26). We therefore prepared β-OH-Tyr-S-NovH by incubation of L-[U-14C]tyrosine with NovH and NovI, as described by Chen and Walsh (7). When the resulting products were precipitated with trichloroacetic acid and cleaved with alkali, [14C]4HBAL was detected by HPLC, representing the retro-aldol reaction product from β-OH-Tyr-S-NovH. When CloQ, DMAPP, and Mg2+ were included in the enzyme incubation, however, no prenylated products were observed (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

Radioactive prenyltransferase assays with CloQ. The three incubation mixtures were analyzed by HPLC with radioactivity detection. The retention times of tyrosine, β-OH-tyrosine, 4HBAL, 3DMA-4HBAL, and ring A were determined by using authentic reference samples.

Therefore, neither β-OH-Tyr-S-NovH nor 4HB or 4HBAL was readily identified as substrates for CloQ.

Inactivation of cloI: Proof for an Independent Pathway for Ring A Biosynthesis.

The cytochrome P450 enzyme CloI is responsible for the hydroxylation of Tyr-S-CloH to β-OH-Tyr-S-CloH (Fig. 2). If the latter compound is indeed an intermediate in ring A biosynthesis, inactivation of cloI should lead to the abolishment of ring A formation. cloI was inactivated by in-frame deletion, and the genotype of the resulting mutant was confirmed by Southern blotting (see Materials and Methods).

HPLC analysis of culture extracts of the cloI− mutant showed abolishment of the clorobiocin production (Fig. 3B). This result was expected because CloI had been shown to catalyze an essential step in ring B biosynthesis (7). The same cultures were subsequently analyzed for the accumulation of ring A, using a different UV wavelength for detection (Fig. 3C). The wild type did not accumulate detectable amounts of this compound. However, ring A was clearly detected in the cloI− mutant (≈3.5 mg/liter of culture). This compound was identified mass spectroscopically, using LC-ESI-CID, by comparison to an authentic reference sample. Moreover, addition of ring B of novobiocin to the cloI− mutant led to the formation of a clorobiocin analogue, termed novclobiocin C102, in which the chlorine atom of clorobiocin is replaced by a methyl group. This compound was identified mass spectroscopically, using negative LC-ESI-CID (m/z = 675 [M − H]−, 488, 206).

These experiments demonstrated that ring A can still be formed in the absence of CloI. Therefore, β-OH-Tyr-S-CloH cannot be an intermediate in the biosynthesis of ring A of clorobiocin (Fig. 2). This finding prompted us to test additional compounds as substrates for CloQ.

Identification of 4HPP as Substrate of CloQ.

When CloQ was incubated with 4HPP and [1-14C]DMAPP, the formation of a prenylation product was readily detected (Fig. 5B). This product was absent from control incubations with heat-denatured CloQ. The incubation was repeated with nonradioactive substrates, and the product was analyzed mass spectroscopically by using LC-ESI-CID, resulting in the following ions: m/z = 247 ([M − 1]−), 203 ([M − 44]−), and 175 ([M − 72]−). This is identical to the mass spectrum of a previously isolated sample of this compound, which had been identified by both mass spectroscopy and 1H NMR (8).

4HPP is an unstable compound and decomposes to 4HBAL, especially in the presence of alkali (27). When the enzymatic prenylation products were treated with 0.5 M NaOH, a nearly complete conversion of 3DMA-4HPP to 3DMA-4HBAL was observed (Fig. 5C). The latter compound was identified in comparison with an authentic reference sample, synthesized according to ref. 17.

Biochemical Properties and Kinetic Parameters of 4HPP Dimethylallyltransferase.

The native molecular mass of CloQ was determined as 34.6 kDa by using gel chromatography, showing that the protein was monomeric in solution. Moreover, the enzyme was soluble in the absence of detergents.

Product formation showed a linear dependence on the amount of protein (up to 3 μg per assay) and on the reaction time (up to 15 min). The reaction was strictly dependent on the presence of active CloQ, 4HPP, and DMAPP. The presence of Mg2+ enhanced prenyltransferase activity, with 2.5 mM being the most effective concentration. However, in the absence of divalent cations and in the presence of 5 mM EDTA, the enzyme retained 25% of its original activity. This finding is in contrast to the absolute requirement for divalent cations reported for most prenyltransferases (13). The addition of Ca2+ (2.5 mM) instead of Mg2+ resulted in 70% of the activity obtained with Mg2+. In contrast to many protein prenyltransferases that contain a tightly bound zinc atom (28), purified CloQ protein was found to contain neither zinc nor magnesium (see Materials and Methods).

CloQ was found to be specific for the substrate 4HPP. No product formation was observed when L-tyrosine, 4HB, 4HBAL, or prephenic acid was used. Only with β-hydroxy-L-tyrosine was formation of dimethylallyl-β-hydroxytyrosine observed. The identity of the product was confirmed by LC-ESI-CID (m/z: 264 [M − H]−, 189, 134). The reaction velocity, however, was only 2% of that obtained with 4HPP. When DMAPP was replaced with isopentenyl diphosphate or geranyl diphosphate, no product formation was observed.

The CloQ reaction apparently followed Michaelis–Menten kinetics, and the Km values were determined as ≈25 μM for 4HPP and 35 μM for DMAPP. The maximum reaction velocity observed was 3,690 pkat⋅mg−1, corresponding to a turnover number of 7.9 min−1.

Discussion

In this study, cloQ was identified as the structural gene for the prenyltransferase involved in the biosynthesis of the 3DMA-4HB moiety of clorobiocin (Fig. 1). 4HPP and DMAPP were identified as the substrates of CloQ. Inactivation of cloQ led to abolishment of clorobiocin formation, which could be restored by addition of ring A. This observation showed that the reaction catalyzed by CloQ is an essential step of the biosynthesis of ring A of clorobiocin.

Novobiocin, just as clorobiocin, contains a 3DMA-4HB moiety, and the novobiocin biosynthetic gene cluster contains the gene novQ. The predicted gene product NovQ (323 aa) shows 84% identity on the amino acid level to CloQ (324 aa) (14, 15). Therefore, NovQ is likely to catalyze the prenyltransferase reaction in novobiocin biosynthesis.

Surprisingly, database searches did not reveal any similarities between NovQ or CloQ and known prenyltransferases. The only match found for CloQ in a BLAST search was a hypothetical protein of Streptomyces coelicolor (E = 4 × 10−8). At present, very few sequences are available for “aromatic” prenyltransferases, i.e., enzymes catalyzing the formation of a carbon–carbon bond between a prenyl group and an aromatic nucleus. Among the few aromatic prenyltransferases that have been cloned are those involved in the biosynthesis of ubiquinones (10), menaquinones (29), tocopherols (30), plastoquinones (31), and the prenyltransferase involved in formation of the plant secondary metabolite shikonin (11). All of these enzymes are integral membrane proteins, and their active centers include the prenyl diphosphate binding site (N/D)DXXD similar to that of the trans-prenyltransferases (12, 13). In contrast, CloQ and NovQ do not show this motif and represent soluble enzymes, without membrane-spanning domains.

The only other soluble aromatic prenyltransferase cloned so far is dimethylallyltryptophan synthase (DMAT), which is involved in ergot alkaloid biosynthesis in the fungus Claviceps (32–36). DMAT was found to be active in a metal-free buffer containing EDTA, in contrast to all previously known prenyltransferases (35, 36). It has been suggested that the reaction catalyzed by DMAT may not proceed via a carbonium ion (35), unlike the reaction of farnesyl-diphosphate synthase (37). In common with DMAT, CloQ was also active in the presence of EDTA, i.e., the reaction did not show an absolute requirement for divalent cations. Moreover, the Km values, the specific activity, and the turnover number determined for CloQ are similar to those reported for DMAT (34–36). However, the bacterial enzyme CloQ (35 kDa) shows only low sequence similarity (20% identity, 33% similarity) to the 50-kDa protein deduced from the sequence of cpd1, suggested as the structural gene for the fungal enzyme DMAT (33). Nevertheless, CloQ, NovQ, and DMAT may belong to a previously unrecognized class of prenyltransferases that exist as soluble enzymes, do not contain the prenyl diphosphate binding motif (N/D)DXXD, and are able to form carbon–carbon bonds between isoprenoid and aromatic substrates.

Acknowledgments

We thank Aventis for the generous gift of the S. roseochromogenes DS 12.976 strain and for authentic clorobiocin. We are grateful to T. Luft for the synthesis of 3DMA-4HBAL; to S. Hildenbrand and R. Wahl, Tübingen University Hospital, for determinations of zinc and magnesium; and to D. Lawson (John Innes Foundation, Norwich, U.K.) for help in the preparation of the manuscript. This work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (to L.H. and S.-M.L.) and by the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

Abbreviations

- ring A

3-dimethylallyl-4-hydroxybenzoic acid

- ring B of novobiocin

3-amino-4,7-dihydroxy-8-methylcoumarin

- DMAPP

dimethylallyl diphosphate

- 4HPP

4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate

- 4HB

4-hydroxybenzoic acid

- 4HBAL

4-hydroxybenzaldehyde

- 3DMA

3-dimethylallyl

- LC

liquid chromatography

- ESI

electrospray ionization

- CID

collision-induced dissociation mass spectroscopy

- DMAT

dimethylallyltryptophan synthase

Footnotes

References

- 1.Gormley N A, Orphanides G, Meyer A, Cullis P M, Maxwell A. Biochemistry. 1996;35:5083–5092. doi: 10.1021/bi952888n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger J, Batcho A D. J Chromatogr Lib. 1978;15:101–159. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lanoot B, Vancanneyt M, Cleenwerck I, Wang L, Li W, Liu Z, Swings J. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2002;52:823–829. doi: 10.1099/00207713-52-3-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li S-M, Hennig S, Heide L. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:2717–2720. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kominek L A. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1972;1:123–134. doi: 10.1128/aac.1.2.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calvert R T, Spring M S, Stoker J R. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1972;24:972–978. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1972.tb08929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen H, Walsh C T. Chem Biol. 2001;8:301–312. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steffensky M, Li S-M, Vogler B, Heide L. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;161:69–74. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melzer M, Heide L. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1212:93–102. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(94)90193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meganathan R. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2001;203:131–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yazaki K, Kunihisa M, Fujisaki T, Sato F. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:6240–6246. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106387200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koyama T, Tajima M, Sano H, Doi T, Koike-Takeshita A, Obata S, Nishino T, Ogura K. Biochemistry. 1996;35:9533–9538. doi: 10.1021/bi960137v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang P H, Ko T P, Wang A H. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:3339–3354. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steffensky M, Mühlenweg A, Wang Z X, Li S-M, Heide L. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1214–1222. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.5.1214-1222.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pojer F, Li S-M, Heide L. Microbiology. 2002;148:3901–3911. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-12-3901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hertweck C, Moore B S. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:9115–9120. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gluesenkamp K H, Buechi G. J Org Chem. 1986;51:4481–4483. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kominek L A, Meyer H F. Methods Enzymol. 1975;43:502–508. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(75)43111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sambrook J, Russel D W. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 3rd Ed. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kieser T, Bibb M J, Buttner M J, Chater K F, Hopwood D A. Practical Streptomyces Genetics. Norwich, U.K.: John Innes Foundation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lombo F, Siems K, Brana A F, Mendez C, Bindseil K, Salas J A. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3354–3357. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3354-3357.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bartolome B, Jubete Y, Martinez E, Cruz F. Gene. 1991;102:75–78. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90541-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bradford M M. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laemmli U K. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Z X, Li S-M, Heide L. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:3040–3048. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.11.3040-3048.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barrow C J, Doleman M S, Bobko M A, Cooper R. J Med Chem. 1994;37:356–363. doi: 10.1021/jm00029a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doy C H. Nature. 1960;186:529–531. doi: 10.1038/186529a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris C M, Derdowski A M, Poulter C D. Biochemistry. 2002;41:10554–10562. doi: 10.1021/bi020349u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suvarna K, Stevenson D, Meganathan R, Hudspeth M E. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2782–2787. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.10.2782-2787.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schledz M, Seidler A, Beyer P, Neuhaus G. FEBS Lett. 2001;499:15–20. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02508-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Collakova E, DellaPenna D. Plant Physiol. 2001;127:1113–1124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsai H F, Wang H, Gebler J C, Poulter C D, Schardl C L. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;216:119–125. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tudzynski P, Holter K, Correia T, Arntz C, Grammel N, Keller U. Mol Gen Genet. 1999;261:133–141. doi: 10.1007/s004380050950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee S L, Floss H G, Heinstein P. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1976;177:84–94. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(76)90418-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cress W A, Chayet L T, Rilling H C. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:10917–10923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gebler J C, Poulter C D. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;296:308–313. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90577-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poulter C D, Rilling H C. Biochemistry. 1976;15:1079–1083. doi: 10.1021/bi00650a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]