Abstract

Blood and/or breast milk have been used to assess human exposure to various environmental contaminants. Few studies have been available to compare the concentrations in one matrix with those in another. The goals of this study were to determine the current levels of polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in Japanese women, with analysis of the effects of lifestyle and dietary habits on these levels, and to develop a quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) with which to predict the ratio of serum concentration to breast milk concentration. We measured PBDEs and PCBs in 89 paired samples of serum and breast milk collected in four regions of Japan in 2005. The geometric means of the total concentrations of PBDE (13 congeners) in milk and serum were 1.56 and 2.89 ng/g lipid, respectively, whereas those of total PCBs (15 congeners) were 63.9 and 37.5 ng/g lipid, respectively. The major determinant of total PBDE concentration in serum and milk was the geographic area within Japan, whereas nursing duration was the major determinant of PCB concentration. BDE-209 was the most predominant PBDE congener in serum but not in milk. The excretion of BDE 209 in milk was lower than that of BDE 47 and BDE 153. QSAR analysis revealed that two parameters, calculated octanol/water partition and number of hydrogen-bond acceptors, were significant descriptors. During the first weeks of lactation, the predicted partitioning of PBDE and PCB congeners from serum to milk agreed with the observed values. However, the prediction became weaker after 10 weeks of nursing.

Keywords: breast milk, partition coefficient, polybrominated diphenyl ethers, polychlorinated biphenyls, quantitative structure—activity relationship, serum

Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) have been found in human breast milk (Darnerud et al. 1998; Noren and Meironyte 1998, 2000). This route is a potential excretion pathway for the mother and a route of exposure to these compounds for the neonate. Thus, the monitoring of breast milk provides data for not only adult exposure but also neonatal exposure.

Recently, an examination of Swedish human milk samples from 1972 to 1997 revealed exponential increases in the concentrations of PBDEs (Darnerud et al. 1998; Noren and Meironyte 1998, 2000). Deca-BDE is used primarily in electrical and electronic applications (e.g., television housing, wire and cable insulation) and to a lesser extent in upholstery textiles. Penta-BDE was formerly used in flexible polyurethane foam for cushions. Octa-BDE was used in acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene resins intended for business equipment housings. PBDEs are now found as residues in sediment (Song et al. 2004); in marine mammals, fish, and bird eggs (Covaci et al. 2005; Kajiwara et al. 2004; Watanabe et al. 2004); and in the breast milk, serum, whole blood, and adipose tissue of humans (Eslami et al. 2005; Koizumi et al. 2005; Lind et al. 2003; She et al. 2002; Takasuga et al. 2004). In contrast to PBDEs, banning the production and use of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in the 1970s has decreased PCB serum levels and dietary exposure to PCBs since the 1980s (Koizumi et al. 2005).

The aims of the present study were 2-fold. The first was to determine the current levels of PBDEs and PCBs in Japanese women of reproductive age and to analyze the effects of lifestyle and dietary habits on these levels. The second was to develop a quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) model, which enables us to predict the relationship between serum and breast milk. The second aim addresses the importance of translatability between the serum and milk data.

Materials and Methods

Target populations

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Kyoto University Institutional Review Board, and appropriate written informed consent was obtained from all the participants before sample collection.

After obtaining formal informed consent, we collected blood and breast milk samples from mothers who had delivered and were lactating in maternity hospitals in four regions: Sendai city (population, 1 million) in Miyagi Prefecture, Takarazuka city (population, 250,000) in Hyogo Prefecture, Takayama city (population, 200,000) in Gifu Prefecture, and Shizunai-cho (population, 23,000) in Hokkaido Prefecture.

Collection of serum samples and breast milk samples

Milk samples were self-collected manually into breast pumps with glass containers at the individual hospitals and transferred to 50-mL polypropylene conical tubes (milk tube) that had been thoroughly rinsed with methanol and acetone before use; samples were kept frozen at –20°C. The target volume was > 20 mL from each mother per sample. Blood samples (10 mL) were collected into two 5-mL vacuum blood collection polypropylene tubes (Venoject II; TERUMO Inc., Tokyo, Japan) (blood tube) from cubital vein by physicians or nurses. The blood and milk samples were shipped within 48 hr to Kyoto University. The serum samples were separated by centrifugation at 3,000g for 15 min, transferred to new blood tubes, and stored at –20°C in the Department of Health and Environmental Sciences, Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine, until analysis.

When the milk samples were collected, we asked the mothers to fill out questionnaires that contained necessary items for milk surveillance (LaKind et al. 2004) and sources of exposure to PBDEs (Ohta et al. 2002; Sakai et al. 2001; Schecter et al. 2005; Wilford et al. 2003), including the duration of lactation, parity, residential history within the previous 5 years, lifestyle and habits, and indoor environment (Supplemental Table 1; available online at http://www.ehponline.org/docs/2006/9032/suppl.pdf).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants.

| Total | Hokkaido | Miyagi | Gifu | Hyogo | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of participants | 89 | 20 | 40 | 20 | 9 | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 20–29 | 45 | 13 | 19 | 10 | 3 | 0.66 |

| 30–39 | 40 | 6 | 20 | 9 | 5 | |

| 40–49 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Mean ± SD | 30.1 ± 4.6 | 27.7 ± 4.8 | 30.7 ± 4.1 | 30.0 ± 4.3 | 33.3 ± 4.5 | 0.01 |

| Parity (mean ± SD) | 1.45 ± 0.6 | 1.55 ± 0.8 | 1.33 ± 0.5 | 1.55 ± 0.7 | 1.56 ± 0.5 | 0.43 |

| Nursing week at milk collection (mean ± SD) | 13.6 ± 22.1 | 1.55 ± 1.6 | 12.0 ± 18.6 | 33.4 ± 30.3 | 3.11 ± 0.9 | < 0.0001* |

| Occupation [no. (%)] | ||||||

| Housewife | 50 (56.2) | 13 (65.0) | 21 (52.5) | 9 (45.0) | 7 (77.8) | 0.21 |

| Office worker | 16 (18.0) | 1 (5.0) | 11 (27.5) | 4 (20.0) | 0 | |

| Technical professional | 22 (24.7) | 5 (25.0) | 8 (20.0) | 7 (35.0) | 2 (22.2) | |

| Farmer | 1 (1.1) | 1 (5.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Use electronic equipment [no. (%)] | ||||||

| Personal computer | ||||||

| Frequent use | 43 (48.3) | 4 (20.0) | 27 (67.5) | 8 (40.0) | 4 (44.4) | 0.004* |

| Rare use | 46 (51.7) | 16 (80.0) | 13 (32.5) | 12 (60.0) | 5 (55.6) | |

| Mobile phone | ||||||

| Frequent use | 58 (65.2) | 13 (65.0) | 26 (65.0) | 15 (75.0) | 4 (44.4) | 0.47 |

| Rare use | 31 (34.8) | 7 (35.0) | 14 (35.0) | 5 (25.0) | 5 (55.6) | |

| Television | ||||||

| Frequent use | 69 (77.5) | 17 (85.0) | 29 (72.5) | 17 (85.0) | 6 (66.7) | 0.36 |

| Rare use | 20 (22.5) | 3 (15.0) | 11 (27.5) | 3 (15.0) | 3 (33.3) | |

| Household furnishings [no. (%)] | ||||||

| Carpet | ||||||

| Frequent use | 65 (73.0) | 18 (90.0) | 28 (70.0) | 12 (60.0) | 7 (77.8) | 0.14 |

| Rare use | 24 (27.0) | 2 (10.0) | 12 (30.0) | 8 (40.0) | 2 (22.2) | |

| Cushions | ||||||

| Frequent use | 52 (58.4) | 10 (50.0) | 24 (60.0) | 10 (50.0) | 8 (88.9) | 0.15 |

| Rare use | 37 (41.6) | 10 (50.0) | 16 (40.0) | 10 (50.0) | 1 (11.1) | |

| Sofa | ||||||

| Frequent use | 66 (74.2) | 18 (90.0) | 30 (75.0) | 11 (55.0) | 7 (77.8) | 0.08 |

| Rare use | 23 (25.8) | 2 (10.0) | 10 (25.0) | 9 (45.0) | 2 (22.2) | |

| Curtains | ||||||

| Frequent use | 81 (91.0) | 18 (90.0) | 37 (92.5) | 17 (85.0) | 9 (100.0) | 0.46 |

| Rare use | 8 (9.0) | 2 (10.0) | 3 (7.5) | 3 (15.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Blinds | ||||||

| Frequent use | 42 (47.2) | 10 (50.0) | 19 (47.5) | 9 (45.0) | 4 (44.4) | 0.99 |

| Rare use | 47 (52.8) | 10 (50.0) | 21 (52.5) | 11 (55.0) | 5 (55.6) | |

| Fish consumption (> once/week) [no. (%)] | ||||||

| Yellowtail and young yellowtail | ||||||

| Yes | 14 (15.7) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (10.0) | 8 (40.0) | 2 (22.2) | 0.003* |

| No | 75 (84.3) | 20 (100.0) | 36 (90.0) | 12 (60.0) | 7 (77.8) | |

| Mackerel | ||||||

| Yes | 34 (38.2) | 5 (25.0) | 12 (30.0) | 10 (50.0) | 7 (77.8) | 0.03 |

| No | 55 (61.8) | 15 (75.0) | 28 (70.0) | 10 (50.0) | 2 (22.2) | |

| Salmon | ||||||

| Yes | 56 (62.9) | 13 (65.0) | 30 (75.0) | 9 (45.0) | 4 (44.4) | 0.30 |

| No | 33 (37.1) | 7 (35.0) | 10 (25.0) | 11 (55.0) | 5 (58.6) | |

| Smoking status [no. (%)] | ||||||

| Nonsmoker | 56 (62.9) | 10 (50.0) | 27 (67.5) | 11 (55.0) | 8 (88.9) | 0.17 |

| Ex-smoker | 25 (28.1) | 8 (40.0) | 10 (25.0) | 7 (35.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Current smoker | 4 (4.5) | 2 (10.0) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Passive smoker | 4 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.0) | 1 (5.0) | 1 (11.1) | |

| Alcohol consumption [no. (%)] | ||||||

| Nondrinker | 35 (39.3) | 12 (60.0) | 12 (30.0) | 7 (35.0) | 4 (44.4) | 0.21 |

| Ex-drinker | 48 (53.9) | 7 (35.0) | 26 (65.0) | 10 (50.0) | 5 (55.6) | |

| Current drinker | 6 (6.7) | 1 (5.0) | 2 (5.0) | 3 (15.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

p < 0.01; p-values were calculated for continuous values by ANOVA and for categorical values for the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test.

We prepared eight field blanks per site, each consisting of an empty milk tube and an empty blood tube. In addition, we prepared eight milk tube/blood tube pairs filled with 5 mL of distilled water at the sampling site as field operational blanks. All the blank samples were sent to Kyoto University and run through complete extraction, cleanup, and analysis procedures.

Serum extraction

The internal standard from mono- to deca-13C12-PBDE and mono to deca-13C12-PCB was spiked in the serum (3 g) and extracted by liquid–liquid extraction following the method of Takasuga et al. (2004, 2006). Briefly, in the serum spiked with internal standard, 3 mL ammonium sulfate, 1 mL ethanol, and 2 mL hexane were mixed and extracted twice. The final extract was washed with hexane-washed water, dehydrated with sodium sulfate, and concentrated to 5 mL for further cleanup.

Milk extraction

The internal standard from mono- through deca-13C12-PBDE and mono- to deca-13C12-PCB was spiked in the milk (3 g) and extracted by liquid–liquid extraction. Briefly, in the milk spiked with internal standard, 1 mL saturated potassium oxalate, 2 mL ethanol, 2 mL diethyl ether, and 1 mL hexane were mixed and extracted twice. The final extract was washed with 1 mL of 5% sodium chloride and then dehydrated with sodium sulfate and concentrated to 5 mL for further cleanup.

Cleanup of serum and milk

The 5-mL extract from serum or milk was subjected to multilayer Florisil silica gel column cleanup (Takasuga et al. 2004, 2006). The multilayer cleaned samples were further concentrated to the injection volume by nitrogen purge.

Identification and quantification of PBDEs and PCBs

We used high-resolution gas chromatography (HRGC; HP6890, Agilent)/high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS; Autospec Ultima; Micromass, Cary, NC, USA) for analysis of PBDEs and PCBs. Details on the HRGC/HRMS program are reported elsewhere (Takasuga et al. 2004, 2006). Briefly, for PBDE analysis we used either a BP-1 [15 m × 0.25 mm i.d. (0.1 μm); SGE Analytical Science Pty. Ltd., Austin, TX, USA] column or a ENV-5MS [15 m × 0.25 mm i.d. (0.1 μm)] column. The column was used with a temperature program of 120°C (1 min), increased 20°C/min to 160°C (0 min), 10°C/min to 260°C (0 min), and 20°C/min to 300°C (8 min). For analysis of PCBs, we used an HT-8 PCB column (60 m × 0.25 mm i.d.; SGE Analytical), which was used with an initial temperature of 150°C (0 min), increased 20°C/min to 200°C (0 min), 5°C/min to 260°C (0 min), and 10°C/min to 300°C (11.5 min). We used an on-column injection program with a 2-μL sample injection volume and with a resolution of M/ΔM > 10,000 (10% valley). We determined the individual and total concentrations of 13 PBDE congeners [ΣPBDE13; International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) congeners 15, 28, 47, 99, 100, 153, 154, 183, 196, 197, 206, 207, and 209] and 15 PCB congeners (ΣPCB15; IUPAC congeners 74, 99, 118, 138, 146, 153, 156, 163/164, 170, 180, 182/187, 194, 199, 206, and 209).

The limit of detection (LOD) for each PCB congener was 1 pg/g in both serum and breast milk. The LOD of each PBDE congener in serum and milk was between 0.2 and 2 pg/g for di-BDE to hepta-BDE and between 0.3 and 2 pg/g for octa-BDE to deca-BDE. The serum and milk concentrations of PCBs and PBDEs were expressed as nanograms per gram lipid. The lipid content in the serum samples was estimated from the total cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations (Phillips et al. 1989). The lipid content of the milk samples was determined from 2 mL crude extracts by gravimetric method.

Quality assurance and quality control

PBDE and PCB (native as well as 13C12−labeled) standard solutions that contained the major congeners of mono-BDE or mono-CB to deca-BDE or deca-CB (> 95% pure) were purchased from Wellington Laboratories (Guelph, Ontario, Canada). The average recovery of individual PBDE congeners was 54–84% in serum (n = 100) and 54–103% in milk (n = 100), and the average recovery of PCB congeners was 61–79% in serum (n = 100) and 68–115% in milk (n = 100). The coefficient of variation for each determination was within 15% for both PBDEs and PCBs.

For all field blanks and field operational blanks, all PBDE and PCB congeners were < LOD. Operational blank tubes filled with 5 mL distilled water in an analytical laboratory (Shimadzu Techno-Research Inc., Kyoto, Japan) were also prepared for each eight-sample batch. These operational blanks were < LOD for all PBDE and PCB congeners in both the serum and milk batches. Thus, we did not correct the results for background levels.

Structure–activity relationship

For the QSAR analysis, we chose congeners that were detected in > 50% of both the serum and milk samples. Theoretical molecular descriptors for the compounds, which included constitutional descriptors, atom-centered fragments, and molecular properties, such as hydrophilicity, molar refractivity, polar surface area, and octanol/water partition coefficient (Kow), were calculated using Dragon software (version 5.0; Milano Chemo Metrics and QSAR Research Group, Milan, Italy) and ADMET Predictor 1.2.3 (Simulations Plus, Lancaster, CA, USA). The Kow calculated by Hansch’s method (CLogP) and the molar refractivity calculated by Hansch’s method (CMR) were calculated using Web applications provided by Daylight Chemical Information Systems (Aliso Viejo, CA, USA). Descriptors that had a bivariate correlation > 0.70 were removed.

We performed a stepwise multiple linear regression analysis using the SAS statistical package (version 8.2; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). All independent variables in the regressions had a significance of at least 95%, based on Student’s t-score.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted after logarithmic transformation of the concentrations of the PBDEs and PCBs. We tested differences between means by analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Student’s t-test when appropriate. A stepwise multiple regression analysis was used to explore determinants for the serum and milk levels of contaminants using a forward–backward stepwise regression model (F-statistic to enter and stay in the model with a p-value of < 0.25). We evaluated the determinants for PBDEs and PCBs in serum and breast milk using a conservative approach based on multiple comparisons of the questionnaire items. Thus, a p-value of < 0.01 was considered significant in the multiple regression analysis for the questionnaire items. For the other analyses, a p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were carried out with SAS software.

Results

Demographic features of the participants

On the whole, there were 20 participants from Hokkaido, 40 from Miyagi, 20 from Gifu, and 9 from Hyogo. The ages of the participants ranged from 20 to 43 years (mean ± SD, 30.1 ± 4.6 years). The results of the questionnaires are summarized in Table 1.

Determination of PBDEs and PCBs in serum and milk

The concentrations of some congeners in the human samples were < LOD. We treated these samples as 0 pg/g lipid when we calculated the total amount.

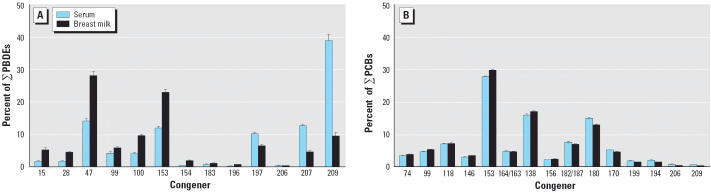

The distributions of ΣPBDE13 in serum and milk followed log-normal distributions (Kolmogorov-Smirnov-Lilliefors test, p > 0.05). The geometric mean (GM) values for the total amounts of ΣPBDE13 in the milk and serum samples were 1.56 and 2.89 ng/g lipid, respectively (Table 2). The PBDE congener levels and detection rates for milk and serum are available online (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3, respectively; http://www.ehponline.org/docs/2006/9032/suppl.pdf). BDE-209 was the predominant congener in serum and accounted for 38% of the total PBDEs but was a minor congener in milk and accounted for 8% of the ΣPBDE13 (Figure 1A). In milk, BDE-47 and BDE-153 were the major congeners and accounted for 28 and 23% of the total PBDEs, respectively.

Table 2.

Concentrations (ng/g lipid) of PBDEs or PCBs in human milk or serum samples.

| Measure/area | No. of participants | GM (GSD)a | Mean ± SD | Range | Q25 | Median | Q75 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBDE in milk | |||||||

| Hokkaido | 20 | 2.23 (1.47)A | 2.39 ± 0.94 | 1.02–4.55 | 1.72 | 2.22 | 2.97 |

| Miyagi | 40 | 1.42 (1.56)B | 1.55 ± 0.65 | 0.49–3.11 | 1.06 | 1.46 | 1.98 |

| Gifu | 20 | 1.45 (1.51)B | 1.58 ± 0.71 | 0.82–3.30 | 1.01 | 1.40 | 2.00 |

| Hyogo | 9 | 1.30 (1.65)B | 1.45 ± 0.70 | 0.66–2.38 | 0.83 | 1.31 | 2.31 |

| Total | 89 | 1.56 (1.59) | 1.74 ± 0.81 | 0.49–4.55 | 1.13 | 1.54 | 2.24 |

| PBDE in serum | |||||||

| Hokkaido | 20 | 2.75 (1.47)AB | 2.93 ± 1.04 | 1.04–5.43 | 2.24 | 2.96 | 3.50 |

| Miyagi | 40 | 3.64 (1.66)B | 4.21 ± 3.14 | 1.33–21.19 | 2.68 | 3.56 | 4.93 |

| Gifu | 20 | 2.06 (1.55)A | 2.24 ± 0.92 | 0.74–4.50 | 1.45 | 2.34 | 2.71 |

| Hyogo | 9 | 2.52 (1.76)AB | 2.84 ± 1.32 | 0.76–5.38 | 1.78 | 3.13 | 3.41 |

| Total | 89 | 2.89 (1.68) | 3.34 ± 2.37 | 0.74–21.19 | 2.16 | 2.99 | 3.76 |

| PCB in milk | |||||||

| Hokkaido | 20 | 58.91 (1.53)AB | 64.50 ± 29.91 | 20–160 | 50.0 | 60.0 | 71.0 |

| Miyagi | 40 | 70.75 (1.56)B | 78.48 ± 40.66 | 29–250 | 54.5 | 72.5 | 89.3 |

| Gifu | 20 | 47.24 (1.76)A | 54.95 ± 30.17 | 18–130 | 33.3 | 51.5 | 72.0 |

| Hyogo | 9 | 94.64 (1.75)B | 109.44 ± 58.41 | 39–190 | 65.0 | 93.0 | 170.0 |

| Total | 89 | 63.86 (1.69) | 73.18 ± 40.90 | 18–250 | 47.0 | 65.0 | 88.0 |

| PCB in serum | |||||||

| Hokkaido | 20 | 35.92 (1.61)AB | 40.65 ± 24.49 | 14–130 | 29.8 | 35.0 | 49.0 |

| Miyagi | 40 | 45.80 (1.72)B | 53.00 ± 31.24 | 15–170 | 32.8 | 51.0 | 62.3 |

| Gifu | 20 | 22.26 (1.88)A | 27.25 ± 18.86 | 7.9–82 | 14.0 | 22.0 | 35.5 |

| Hyogo | 9 | 54.32 (1.85)B | 65.22 ± 40.67 | 23–130 | 34.0 | 50.0 | 89.0 |

| Total | 89 | 37.52 (1.89) | 45.67 ± 30.58 | 7.9–170 | 26.0 | 38.0 | 57.0 |

Abbreviations: GSD, geometric SD; Q25, first quartile; Q75, third quartile.

Different letters (A, B, or AB) indicate that the corresponding values are statistically different by Tukey’s HSD test after ANOVA (p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Correlation coefficients between pairs of molecular descriptors or log P for PCBs and PBDEs.

| log Kow | CLogP | MLogP | MW | MgVol | CMR | AMR | PolarizG | TPSA | HBA | nCL | nBR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| log Kow | 1 | |||||||||||

| CLogP | 0.978 | 1 | ||||||||||

| MLogP | 0.899 | 0.948 | 1 | |||||||||

| MW | 0.876 | 0.835 | 0.634 | 1 | ||||||||

| MgVol | 0.900 | 0.866 | 0.677 | 0.998 | 1 | |||||||

| CMR | 0.967 | 0.958 | 0.832 | 0.956 | 0.972 | 1 | ||||||

| AMR | 0.968 | 0.960 | 0.836 | 0.954 | 0.970 | 1.000 | 1 | |||||

| PolarizG | 0.964 | 0.954 | 0.823 | 0.961 | 0.975 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1 | ||||

| TPSA | 0.270 | 0.189 | –0.125 | 0.667 | 0.631 | 0.437 | 0.430 | 0.450 | 1 | |||

| HBA | 0.270 | 0.189 | –0.125 | 0.667 | 0.631 | 0.437 | 0.430 | 0.450 | 1.000 | 1 | ||

| nCL | –0.102 | 0.008 | 0.305 | –0.540 | –0.490 | –0.270 | –0.263 | –0.286 | –0.936 | –0.936 | 1 | |

| nBR | 0.648 | 0.570 | 0.301 | 0.928 | 0.903 | 0.778 | 0.773 | 0.788 | 0.871 | 0.871 | –0.816 | 1 |

| log P | –0.891 | –0.894 | –0.731 | –0.921 | –0.933 | –0.940 | –0.939 | –0.941 | –0.499 | –0.499 | 0.326 | –0.777 |

Figure 1.

Distributions of PBDE (A) and PCB (B) congeners in milk and serum from the 89 participants (mean ± SE). The levels of each congener are indicated as the mean percentage of the ΣPBDE or ΣPCB concentration.

The distributions of the ΣPCB15 in serum and milk also followed log-normal distributions (Kolmogorov-Smirnov-Lilliefors test, p > 0.05). The GM values for ΣPCB15 in the milk and serum samples were 63.9 and 37.5 ng/g lipid, respectively (Table 2). The PCB congener levels and detection rates for milk and serum are available online (Supplemental Tables 4 and 5, respectively; http://www.ehponline.org/docs/2006/9032/suppl.pdf). CB-153, CB-138, and CB-180 were the major congeners in both milk and serum (30, 17, and 13% of the total for milk and 28, 16, and 15% of the total for serum, respectively) (Figure 1B).

Table 4.

PBDE levels in human milk and blood samples from different countries.

| ΣPBDE (ng/g lipid) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country/type | No. of samples | Year of sampling | Mean | Median | BDE-209mean | PBDE congeners included in ΣPBDE | Reference |

| Japan | |||||||

| Milk | 105 | 2004 | 2.54 | 1.28 | 28, 47, 99, 100, 153, 154 | Eslami et al. 2005 | |

| Milk | 89 | 2005 | 1.74 | 1.54 | 0.12 | 15, 28, 47, 99, 100, 153, 154, 183, 196, 197, 206, 207, 209 | Present study |

| Serum | 40 | 1995 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 47, 99, 100, 153 | Koizumi et al. 2005 | |

| Serum | 89 | 2005 | 3.34 | 2.99 | 1.20 | 15, 28, 47, 99, 100, 153, 154, 183, 196, 197, 206, 207, 209 | Present study |

| Milk | 12 | 1999 | 1.72 | 28, 47, 99, 153, 154 | Ohta et al. 2002 | ||

| Milk | 1(27)a | 2000 | 1.39 | 0.04 | 28, 37, 47, 66, 75, 77, 85, 99, 100, 138, 153, 154, 183 | Akutsu et al. 2003 | |

| Blood | 156 | 1999–2001 | 13 | 6.9 | 9.20 | 3, 7, 15, 17, 28, 47, 49, 66, 71, 77, 85, 99, 100, 119, 126, 138, 139, 153, 154, 183, 209 | Takasuga et al. 2004 |

| Milk | 4 | 2003 | 1.04 | 17, 25, 28, 30, 32, 33, 35, 37, 47, 49, 66, 71, 75, 77, 85, 99, 100, 116, 119, 126, 138, 153, 154, 155, 166 | Hirai et al. 2004 | ||

| Blood | 4 | 2003 | 0.3 | 17, 25, 28, 30, 32, 33, 35, 37, 47, 49, 66, 71, 75, 77, 85, 99, 100, 116, 119, 126, 138, 153, 154, 155, 166 | Hirai et al. 2004 | ||

| United States | |||||||

| Milk | 47 | 2002 | 73.9 | 34 | 0.92 | 28, 47, 99, 100, 153, 154 | Schecter et al. 2003 |

| Milk | 16 | 2004 | 77.5 | 48.5 | 0.38 | 28, 32, 33, 47, 66, 71, 85, 99, 100, 153, 154, 183, 209 | She et al. 2004 |

| Serum | 93 | 2001–2003 | 24.6 | 47, 85, 99, 100, 153, 154, 183 | Morland et al. 2005 | ||

| Serum | 7 | 2000–2002 | 61 | 17, 28, 47, 66, 85, 99, 100, 153, 154, 183, 203, 209 | Sjödin et al. 2004 | ||

| Serum | 12 | 2001 | 37 | 47, 99, 100, 153, 154, 183 | Mazdai et al. 2003 | ||

| Canada | |||||||

| Milk | 10 | 1992 | 5.65 | 3.03 | 28, 47, 99, 100, 153 | Ryan and Patry 2000 | |

| Milk | 98 | 2001–2002 | 22 | 28, 47, 99, 100, 153 | Pereg et al. 2003 | ||

| Plasma | 10 | 1994–1999 | 23.3 | 20.3 | 28, 47, 85, 99, 100, 153, 154, 183 | Ryan and van Oostdam 2004 | |

| Mexico | |||||||

| Milk | 7 | 2003 | 4.4 | 0.30 | 47, 99, 100, 153, 154, 209 | López et al. 2004 | |

| Plasma | 5 | 2003 | 29.1 | 9.50 | 47, 99, 100, 153, 154, 209 | López et al. 2004 | |

| United Kingdom | |||||||

| Milk | 54 | 2001–2003 | 8.9 | 6.3 | 17, 28, 32, 35, 37, 47, 49, 71, 75, 85, 99, 100, 119, 153, 154 | Kalantzi et al. 2004 | |

| Sweden | |||||||

| Milk | 93 | 1996–1999 | 4.01 | 3.15 | 47, 99, 100, 153, 154 | Lind et al. 2003 | |

| Serum | 20 | 1997 | 3.3 | 47, 153, 154, 183, 209 | Sjödin et al. 1999 | ||

| Milk | 15 | 2000–2001 | 2.14 | 17, 28, 47, 66, 85, 99, 100, 153, 154, 183 | Guvenius et al. 2003 | ||

| Plasma | 15 | 2000–2001 | 2.07 | 17, 28, 47, 66, 85, 99, 100, 153, 154, 183 | Guvenius et al. 2003 | ||

| Norway | |||||||

| Serum | 1(29)a | 1999 | 3.34 | 28, 47, 99, 100, 153, 154 | Thomsen et al. 2002 | ||

| Finland | |||||||

| Milk | 11 | 1994–1998 | 2.25 | 1.62 | 28, 47, 99, 153 | Strandman et al. 2000 | |

| Germany | |||||||

| Milk | 93 | 2001–2003 | 2.23 | 1.78 | 0.17 | 28, 47, 99, 153, 154, 183, 209 | Vieth et al. 2004 |

| Netherlands | |||||||

| Serum | 78 | 2001–2002 | 10.7 | 9.3 | 47, 99, 100, 153, 154 | Weiss et al. 2004 | |

| Spain | |||||||

| Milk | 15 | 2002 | 2.41 | 1.7 | 15 congeners | Schuhmacher et al. 2004 | |

| Italy | |||||||

| Milk | 4(40)a | 2000–2001 | 2.75 | 28, 47, 66, 85, 99, 100, 138, 153, 154, 183 | Ingelido et al. 2004 | ||

The numbers of pooled samples are shown in parentheses.

It should be noted that approximately the same concentrations of the lighter PBDEs (e.g., BDE-47) are present in serum and milk, but BDE-209 is found at 10 times lower concentrations in milk than in serum (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3; available online at http://www.ehponline.org/docs/2006/9032/suppl.pdf). Likewise, almost double the serum concentration of CB-153 is found in milk, whereas more than double the milk concentration of CB-209 is found in serum (Supplemental Tables 4 and 5; available online at http://www.ehponline.org/docs/2006/9032/suppl.pdf).

Determinants for PCBs and PBDEs in serum and milk

We found significant correlations between ΣPCB15 and ΣPBDE13 levels in both milk and serum (r2 = 0.194, p < 0.0001 for milk; r2 = 0.1808, p < 0.0001 for serum). There were also significant geographic differences in ΣPBDE13 concentrations in milk and serum (ANOVA, p = 0.00095 and p = 0.00030, respectively; Table 2). The GM for ΣPBDE13 in the milk samples was higher for Hokkaido than for the other areas [Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD) test, p < 0.05], whereas the GM for ΣPBDE13 in serum samples was higher in Miyagi than in Gifu (Tukey’s HSD test, p < 0.05). The PCB levels also exhibited geographic differences (ANOVA, p = 0.0029 for milk and p < 0.0001 for serum; Table 2). The GMs for ΣPBDE13 in both milk and serum samples were higher in Miyagi and Hyogo than in Gifu (Tukey’s HSD test, p < 0.05).

Multiple regression analysis revealed that the geographic factor was the primary determinant for the PBDE levels in both milk and serum (data not shown). In contrast, nursing duration was the significant determinant for PCB levels in both serum and milk (data not shown). To investigate the possible association between hospitals and nursing durations, we tested whether nursing duration was a determinant for PBDE or PCB levels within a single hospital. The nursing duration was correlated with the ΣPBDE13 in serum in Miyagi (n = 38, Kendall’s τ= −0.266, p = 0.0187) and the ΣPCB15 in both serum and milk in Miyagi (n = 38, Kendall’s τ= –0.426, p = 0.0002, and Kendall’s τ= –0.312, p = 0.0059, respectively; data not shown).

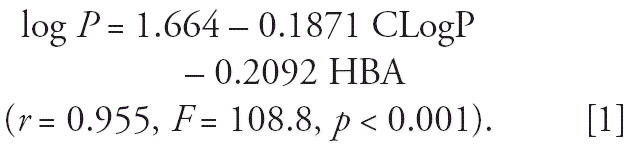

QSAR analysis

BDE-154, BDE-183, BDE-196, and BDE-206 were eliminated from the analysis because of their low detection rates in serum and/or milk (< 50%). In the first step, we calculated the mean ratios of milk concentrations (nanograms per gram lipid) to serum concentrations (nanograms per gram lipid) for individual congeners from milk and serum as surrogates for their partition coefficients (Supplemental Table 6; available online at http://www.ehponline.org/docs/2006/9032/suppl.pdf). Using these mean ratios, we then applied a multiple linear regression analysis using various descriptors for individual PCB and PBDE congeners. The descriptors that have been used for QSAR analysis include hydrophobicity [log Kow, CLogP, (octanol/water partition coefficient calculated by Hansch’s method), and MLogP (octanol/water partition coefficient calculated by Moriguchi’s method)], size [MW (molecular weight) and MgVol (molar volume calculated by McGowan’s method)], polarizability [CMR, (molar refractivity calculated by Hansch’s method), AMR (calculated by Ghose and Crippen’s method), and PolarizG (polarizability calculated by Glen’s method)], and constitutional descriptors [TPSA (topologic polar surface area), HBA (number of hydrogen-bond acceptors), nCL (number of chlorines), and nBR (number of bromines)] (Table 3) (Abraham and McGowan 1987; Ghose and Crippen 1987; Glen 1994; Leo et al. 1971; Moriguchi et al. 1994).

Table 3 summarizes the correlation coefficients between pairs of the descriptors, together with regression coefficients for each descriptor. Regarding PCB and PBDE congeners, the descriptors for hydrophobicity (log Kow, CLogP, and MLogP), molecular size (MW and MgVol), and polarizability (CMR, AMR, and PolarizG) were collinear, and each correlated well with the milk/serum partition coefficient (log P). We explored the combination of the descriptors that exhibited the highest multiple regression coefficient (r) and obtained the following equation:

|

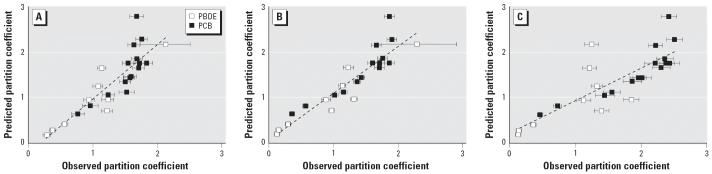

Because partition coefficients have been reported to be dependent on the nursing period (LaKind et al. 2004), we tested the relationship between the predicted and observed mean partition coefficients for three nursing durations (Figure 2). For nursing durations ≤10 weeks, the partition coefficients predicted by the QSAR analysis agreed with the observed values. However, the coefficient of x was smaller for nursing durations > 10 weeks, suggesting that the prediction became weaker for longer nursing periods.

Figure 2.

Predicted and observed partition coefficients (milk/serum) of PBDE and PCB congeners by nursing duration. (A) Weeks 0–1. (B) Weeks 2–10. (C) Weeks 11–88. The y-axis represents the predicted partition coefficient, and the x-axis represents the ratio of the observed milk concentration to the observed serum concentration (mean ± SE). For (A), the relationship between the predicted (y) and observed (x) partition coefficients was y = 1.210x – 0.237 (r = 0.866, p < 0.001, n = 26); for weeks 2–10 (B), y = 1.028x + 0.082 (r = 0.921, p < 0.001, n = 38); for weeks 11–88 (C), y = 0.717x + 0.233 (r = 0.824, p < 0.001, n = 25).

Discussion

In this article we have reported the current levels of ΣPBDE13, including deca-BDE (BDE-209), in serum and milk from Japanese mothers. We found that BDE-209 was the most abundant congener in serum but a minor congener in milk. Its abundance in serum suggests that wide industrial use of BDE-209 may result in exposure (Watanabe and Sakai 2003). Thus, low partitioning of this congener from serum to milk might have resulted in the underestimation of human adult exposure to deca-BDE, if the exposure monitoring system used was dependent solely on milk surveillance.

Table 4 shows the recent data on PBDEs in breast milk and serum from 12 countries. The current total PBDE levels in Japan are significantly lower than those in most Western countries (Kalantzi et al. 2004; López et al. 2004; Mazdai et al. 2003; Morland et al. 2005; Pereg et al. 2003; Ryan and Patry 2000; Ryan and van Oostdam 2004; Schecter et al. 2003; She et al. 2004; Sjödin et al. 2004) and appear to be approximately equal to those of Sweden (Guvenius et al. 2003; Kalantzi et al. 2004; Lind et al. 2003; Sjödin et al. 1999), Spain (Schuhmacher et al. 2004), Italy (Ingelido et al. 2004), Germany (Vieth et al. 2004), and Finland (Strandman et al. 2000). Even for BDE-209, exposure was relatively lower in Japan than in the United States and Mexico. Even taking into account the variations in the measured PBDE congeners, the above argument holds true.

We investigated factors that may influence the PBDE or PCB levels in serum and milk. We found that the geographic factor was the major determinant of PBDE levels in Japan. In contrast, current nursing duration was most significant for PCBs. Because the current nursing duration was confounded by the variation in the timing of milk collection in the different hospitals, one could argue that the apparent differences might be explained partly by the geographic factor. However, the current nursing duration remained significant for both PBDEs and PCBs even within sample series from a single hospital, indicating that their concentrations became lower as the nursing period became longer, as previously reported by others (Wilson et al. 1985).

Human milk or serum surveillance is typically performed to monitor temporal changes in the concentrations of environmental chemicals or to compare the concentrations of environmental chemicals among different populations. However, only a few trials to bridge the values for serum and milk have been carried out for environmental chemicals (Greizerstein et al. 1999). In contrast, there have been several models and methods for predicting drug transfer into human milk (Fleishaker 2003) using the QSAR approach. We applied the same approach for PCBs and PBDEs. The analysis revealed that CLogP and HBA are sufficient predictors of the transfer from serum to milk. For PBDEs, the oxygen atom bridging two halogenated aryl groups, which functions as a hydrogen-bond acceptor, appeared to reduce the transfer from serum to milk. On the other hand, the model only weakly predicted the partition coefficients in the later stages of nursing (≥11 weeks), as suggested by Wilson et al. (1985). With the limitation of the nursing period as a mode of prediction by Equation 1, the present model can be practically used for translating the concentrations in the two samples.

Conclusion

BDE-209 was the PBDE detected at the highest concentration in serum of Japanese lactating women, but its excretion in milk was lower than that of the lower brominated diphenyl ethers BDE-47 and BDE-153. Geographic location within Japan and the duration of nursing were discernible determinants for levels of PBDEs and PCBs in human serum and milk, respectively. The levels of PBDEs in Japan were much lower than those in the United States, Canada, and Mexico but similar to those in European countries. The application of QSAR for the structure–partition relationship revealed that the values for serum and milk are translatable to each other.

Footnotes

Supplemental Material is available online at http://www.ehponline.org/docs/2006/9032/suppl.pdf

This study was supported primarily by a Grant-in-Aid for Health Sciences Research from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan (H15-Chemistry-004), but also received funding from and by the Nippon Life Insurance Foundation (Environment-04-08).

Supplementary Material

References

- Abraham MH, McGowan JC. The use of characteristic volumes to measure cavity terms in reversed phase liquid chromatography. Chromatographia. 1987;23:243–246. [Google Scholar]

- Akutsu K, Kitagawa M, Nakazawa H, Makino T, Iwazaki K, Oda H, et al. Time-trend (1973–2000) of polybrominated diphenyl ethers in Japanese mother’s milk. Chemosphere. 2003;53:645–654. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(03)00764-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covaci A, Bervoets L, Hoff P, Voorspoels S, Voets J, Van Campenhout K, et al. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in freshwater mussels and fish from Flanders, Belgium. J Environ Monit. 2005;7:132–136. doi: 10.1039/b413574a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnerud PO, Atuma S, Aune M, Cnattingius S, Wernroth ML, Wicklund-Glynn A. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers PBDEs in breast milk from primiparous women in Uppsala County, Sweden. Organohalogen Compounds. 1998;35:411–414. [Google Scholar]

- Eslami B, Koizumi A, Yoshinaga T, Harada K, Inoue K, Morikawa A, et al. Large-scale evaluation of the current level of poly-brominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in breast milk from 13 regions of Japan. Chemosphere. 2005;99:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleishaker JC. Models and methods for predicting drug transfer into human milk. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2003;55:643–652. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(03)00032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghose AK, Crippen GM. Atomic physicochemical parameters for three-dimensional-structure-directed quantitative structure-activity relationships. 2. Modeling dispersive and hydrophobic interactions. J Comput Sci. 1987;27:21–35. doi: 10.1021/ci00053a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glen RC. A fast empirical method for the calculation of molecular polarizability. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 1994;8:457–466. doi: 10.1007/BF00125380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greizerstein HB, Stinson C, Mendola P, Buck GM, Kostyniak PJ, Vena JE. Comparison of PCB congeners and pesticide levels between serum and milk from lactating women. Environ Res. 1999;80:280–286. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1999.3956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guvenius DM, Aronsson A, Ekman-Ordeberg G, Bergman A, Noren K. Human prenatal and postnatal exposure to polybrominated diphenyl ethers, polychlorinated biphenyls, polychlorobiphenylols, and pentachlorophenol. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:1235–1241. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai T, Fujimine Y, Watanabe S, Nakamura Y, Shimomura H, Nagayama J. Maternal-infant transfer of polybrominated diphenyl ethers. Organohalogen Compounds. 2004;66:2451–2456. [Google Scholar]

- Ingelido AM, Di Domenico A, Ballard T, De Felip E, Dellatte E, Ferri F, et al. Levels of polybrominated diphenyl ethers in milk from Italian women living in Rome and Venice. Organohalogen Compounds. 2004;66:2722–2727. [Google Scholar]

- Kajiwara N, Ueno D, Takahashi A, Baba N, Tanabe S. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers and organochlorines in archived northern fur seal samples from the Pacific coast of Japan, 1972–1998. Environ Sci Technol. 2004;38:3804–3809. doi: 10.1021/es049540c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalantzi OI, Martin FL, Thomas GO, Alcock RE, Tang HR, Drury SC, et al. Different levels of polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) and chlorinated compounds in breast milk from two U.K. regions. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:1085–1091. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi A, Yoshinaga T, Harada K, Inoue K, Morikawa A, Muroi J, et al. Assessment of human exposure to poly-chlorinated biphenyls and polybrominated diphenyl ethers in Japan using archived samples from the early 1980s and mid-1990s. Environ Res. 2005;99:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaKind JS, Amina Wilkins A, Berlin CM., Jr Environmental chemicals in human milk: a review of levels, infant exposures and health, and guidance for future research. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;198:184–208. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leo A, Hansch C, Elkins D. Partition coefficients and their uses. Chem Rev. 1971;71:525–616. [Google Scholar]

- Lind Y, Darnerud PO, Atuma S, Aune M, Becker W, Bjerselius R, et al. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers in breast milk from Uppsala County, Sweden. Environ Res. 2003;93:186–194. doi: 10.1016/s0013-9351(03)00049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López D, Athanasiadou M, Athanassiadis I, Estrada LY, Diaz-Barriga F, Bergman Å.2004. A preliminary study on PBDEs and HBCDD in blood and milk from Mexican women. In: Third International Workshop on Brominated Flame Retardants, 6–9 June 2004, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; University of Toronto, 483–487. Available: http://www.bfr2004.com/Individual%20Papers/BFR2004%20Abstract%20111%20Lopez.pdf [accessed 2 June 2006].

- Mazdai A, Dodder NG, Abernathy MP, Hites RA, Bigsby RM. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers in maternal and fetal blood samples. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:1249–1252. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriguchi I, Hirono S, Nakagome I, Hirano H. Comparisons of reliability of log P values for drugs calculated by several methods. Chem Pharm Bull. 1994;42:976–978. [Google Scholar]

- Morland KB, Landrigan PJ, Sjödin A, Gobeille AK, Jones RS, McGahee EE, et al. Body burdens of polybrominated diphenyl ethers among urban anglers. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:1689–1692. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noren K, Meironyte D. Contaminations in Swedish human milk. Decreasing levels of organocholorine and increasing levels of organobromine compounds. Organohalogen Compounds. 1998;38:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Noren K, Meironyte D. Certain organochlorine and organobromine contaminants in Swedish human milk in perspective of past 20–30 years. Chemosphere. 2000;40:1111–1123. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(99)00360-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta S, Ishizuka D, Nishimura H, Nakao T, Aozasa O, Shimidzu Y, et al. Comparison of polybrominated diphenyl ethers in fish, vegetables, and meats and levels in human milk of nursing women in Japan. Chemosphere. 2002;46:689–696. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(01)00233-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereg D, Ryan JJ, Ayotte P, Muckle G, Patry B, Dewailly E. Temporal and spatial changes of brominated diphenyl ethers (BDEs) and other POPs in human milk from Nunavik (Arctic) and southern Quebec. Organohalogen Compounds. 2003;61:127–130. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DL, Pirkle JL, Burse VW, Bernert JTJ, Henderson LO, Needham LL. Chlorinated hydrocarbon levels in human serum: effects of fasting and feeding. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 1989;18:495–500. doi: 10.1007/BF01055015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan JJ, Patry B. Determination of brominated diphenyl ethers (BDEs) and levels in Canadian human milk. Organohalogen Compounds. 2000;47:57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan JJ, van Oostdam J. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in maternal and cord blood plasma of several northern Canadian populations. Organohalogen Compounds. 2004;66:2579–2585. [Google Scholar]

- Sakai S, Honda Y, Takatsuki H, Watanabe J, Aoki I, Nakamura K, et al. Polybrominated substances in waste electrical and electronic plastics and their behavior in the incineration plants. Organohalogen Compounds. 2001;52:35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Schecter A, Papke O, Joseph JE, Tung KC. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in U.S. computers and domestic carpet vacuuming: possible sources of human exposure. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2005;68:501–513. doi: 10.1080/15287390590909715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schecter A, Pavuk M, Papke O, Ryan JJ, Birnbaum L, Rosen R. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in U.S. mothers’ milk. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:1723–1729. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuhmacher M, Kiviranta H, Vartiainen T, Domingo LL. Concentrations of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in breast milk of women from Catalonia, Spain. Organohalogen Compounds. 2004;66:2560–2566. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.05.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- She J, Holden A, Sharp M, Tanner M, Williams-Derry C, Hooper K. Unusual pattern of polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in US breast milk. Organohalogen Compounds. 2004;66:3945–3950. [Google Scholar]

- She J, Petreas M, Winkler J, Visita P, McKinney M, Kopec D. PBDEs in the San Francisco Bay Area: measurements in harbor seal blubber and human breast adipose tissue. Chemosphere. 2002;46:697–707. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(01)00234-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjödin A, Hagmar L, Klasson-Wehler E, Kronholm-Diab K, Jakobsson E, Bergman Å. Flame retardant exposure: polybrominated diphenyl ethers in blood from Swedish workers. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107:643–648. doi: 10.1289/ehp.107-1566483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjödin A, Jones RS, Focant JF, Lapeza C, Wang RY, McGahee EE, III, et al. Retrospective time-trend study of poly-brominated diphenyl ether and polybrominated and poly-chlorinated biphenyl levels in human serum from the United States. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:654–658. doi: 10.1289/ehp.112-1241957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W, Ford JC, Li A, Mills WJ, Buckley DR, Rockne KJ. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers in the sediments of the Great Lakes. 1. Lake Superior. Environ Sci Technol. 2004;38:3286–3293. doi: 10.1021/es035297q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strandman T, Koistinen J, Vartiainen T. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in placenta and human milk. Organohalogen Compounds. 2000;47:61–64. [Google Scholar]

- Takasuga T, Senthilkumar K, Matsumura T, Shiozaki K, Sakai S. Isotope dilution analysis of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in transformer oil and global commercial PCB formulations by high resolution gas chromatography–high resolution mass spectrometry. Chemosphere. 2006;62:469–484. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takasuga T, Senthilkumar K, Takemori H, Ohi E, Tsuji H, Nagayama J. Impact of fermented brown rice with Aspergillus oryzae (FEBRA) intake and concentrations of polybrominated diphenylethers (PBDEs) in blood of humans from Japan. Chemosphere. 2004;57:795–811. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen C, Lundanes E, Becher G. Brominated flame retardants in archived serum samples from Norway: a study on temporal trends and the role of age. Environ Sci Technol. 2002;36:1414–1418. doi: 10.1021/es0102282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieth B, Herrmann T, Mielke H, Ostermann B, Papke O, Rudiger T. PBDE levels in human milk: the situation in Germany and potential influencing factors—a controlled study. Organohalogen Compounds. 2004;66:2643–2648. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe I, Sakai S. Environmental release and behavior of brominated flame retardants. Environ Int. 2003;29:665–682. doi: 10.1016/s0160-4120(03)00123-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K, Senthilkumar K, Masunaga S, Takasuga T, Iseki N, Morita M. Brominated organic contaminants in the liver and egg of the common cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo) from Japan. Environ Sci Technol. 2004;38:4071–4077. doi: 10.1021/es0307221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss J, Meijer L, Sauer P, Linderholm L, Athanassiadis I, Bergman A. PBDE and HBCDD levels in blood from Dutch mothers and infants—analysis of a Dutch Groningen Infant Cohort. Organohalogen Compounds. 2004;66:2677–2682. [Google Scholar]

- Wilford BH, Thomas GO, Alcock RE, Jones KC, Anderson DR. Polyurethane foam as a source of PBDEs to the environment. Organohalogen Compounds. 2003;61:219–222. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JT, Brown RD, Hinson JL, Dailey JW. Pharmaco-kinetic pitfalls in the estimation of the breast milk/plasma ratio for drugs. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1985;25:667–689. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.25.040185.003315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.