Abstract

A 17-year-old female patient presented with unusual enlargement of the gingiva with generalized alveolar bone loss. In spite of periodontal therapy, including plaque control, scaling, root planning and surgical treatment, recurrence with the same degree of the gingival enlargement and further loss of attachment level occurred. Biopsy revealed dense infiltration of normal plasma cells separated by collagenous stroma. Discontinuation of herbal toothpaste resulted in remarkable remission of the gingival enlargement within 2 weeks. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of toothpaste components disclosed “Acacia” as an etiologic antigenic agent and confirmed the diagnosis of plasma cell gingivitis (PCG). Usually, PCG is not associated with the loss of attachment. This case report appears to be the first publication to document an atypical presentation of PCG with generalized aggressive periodontitis related to the use of herbal toothpaste containing “Acacia” extract from the tree “Acacia Arabica.”

Keywords: Acacia extract, generalized aggressive periodontitis, gingival enlargement, herbal toothpaste, plasma cell gingivitis

INTRODUCTION

Plasma cell gingivitis (PCG) is a rare condition characterized by diffuse and massive infiltration of plasma cells into the sub-epithelial gingival tissue. Clinically, it appears as diffuse reddening and edematous swelling of the gingiva with a sharp demarcation along the mucogingival border. PCG is known by a variety of other names such as atypical gingivitis, plasma cell gingivostomatitis and allergic gingivostomatitis.[1] The etiology of PCG is not clear, but due to the obvious presence of plasma cells many authors are of the opinion that it is an immunological reaction to allergens. Flavoring agents such as cinnamonaldehyde and cinnamon in toothpaste and chewing gum, mint pastels, khat, strong spices and some herbs such as chili, pepper and cardamom may be important factors.[2,3,4,5]

Aggressive periodontitis (AgP) represents the most heterogenous and severe form of periodontitis due to its peculiar clinical presentation: Occurring around puberty and amount of microbial deposits inconsistent with the severity of periodontal destruction.

Usually PCG is not associated with the loss of attachment. This report outlines a case of PCG associated with generalized aggressive periodontitis (GAgP), which was brought on by the use of herbal toothpaste containing “Acacia” extract from the tree “Acacia Arabica.”

CASE REPORT

A 17-year-old girl was referred to the Department of Periodontics with the chief complaint of gingival overgrowth and mobility in her teeth for the last 2 years. She reported that the problem has begun in lower anterior and progressed involving both the arches. Patient appeared fit and indicated no current or previous systemic disease during her medical history interview.

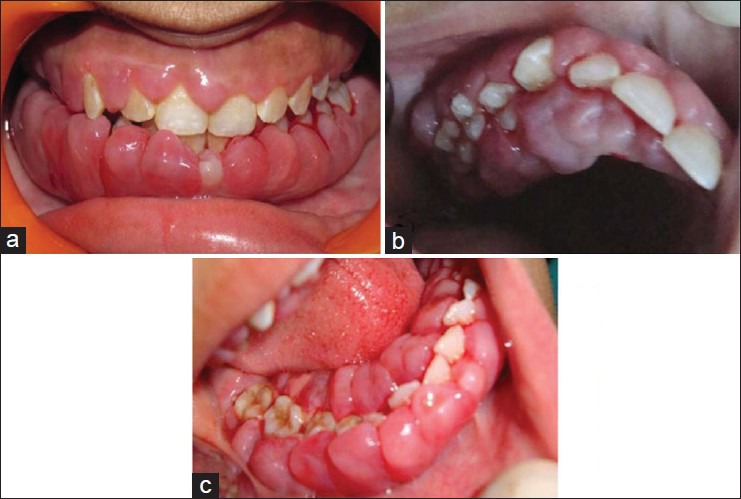

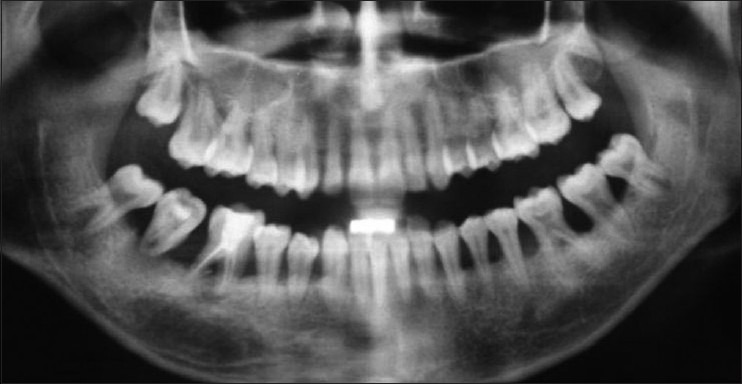

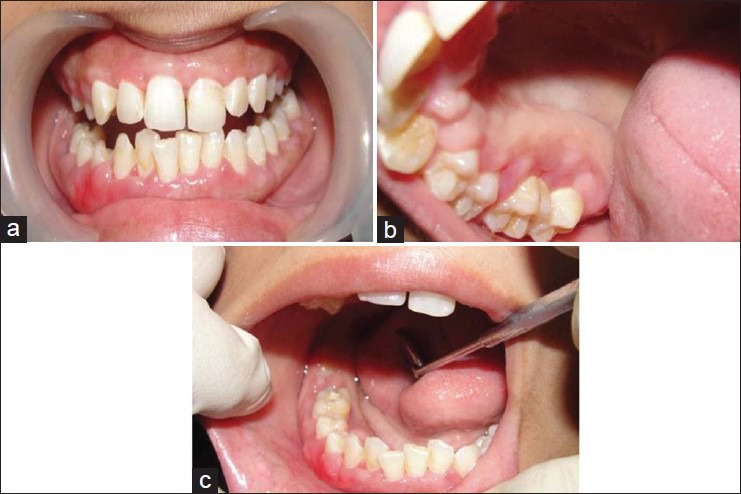

Intraorally, severe diffuse gingival enlargement of both the arcades (more pronounced on the right side) was observed covering almost all the surfaces of teeth and projecting into the vestibule [Figure 1a–c]. Gingiva was bright red, friable, fibrous as well as edematous in consistency. The erythema was disproportionate to the amount of plaque and calculus remaining on the dentition panoramic radiograph demonstrated generalized alveolar bone loss [Figure 2]. Probing depth ranged from 10 mm to 12 mm with an attachment loss of 7-9 mm and was more in the right molar region. Grade 2 mobility was present around the mandibular and maxillary first and second molars and grade 1 around the mandibular right premolars.

Figure 1.

(a) Facial; (b) maxillary occlusal and (c) mandibular occlusal view of enlargement of the gingiva at the initial visit

Figure 2.

Panoramic radiograph at the initial visit

Laboratory tests revealed no evidence of any systemic disease such as leukemia, scurvy and hormonal disorders.

Internal bevel gingivectomy was performed in the maxillary arch and left mandibular region[Figure 3]. Adjunctive amoxicillin (500 mg, 3 × 1) plus metronidazole (400 mg, 3 × 1) for 7 days was prescribed to treat AgP. Patient could not continue her treatment for personal reasons and when she reported after 1 year, the recurrence of gingival enlargement was noticed [Figure 4a–c]. Periodic panoramic radiographic examination revealed progressive alveolar bone loss, which was more pronounced on the right lower molars [Figure 5]. Biopsy showed hyperplastic stratified squamous epithelium along with ulceration of epithelium at places. Sub-epithelial tissue revealed a large number of normal plasma cells, few eosinophils and inflammatory granulation tissue [Figure 6a and b]. A diagnosis consistent with PCG was made. To clarify whether this enlargement was due to a hypersensitivity reaction, the screening for the various antigenic substances was done. The patient was questioned about the habitual use of chewing gum, mouthwash and toothpaste. The only relevant history given by the patient was the use of herbal toothpaste (Babool, Dabur Oral Care Products, India) for the last 3-4 years. The patient was advised to discontinue the use of herbal toothpaste, which dramatically reduced the severity of enlargement within 2 weeks [Figure 7a–c]. Moreover, the patient herself switched on to other herbal toothpaste (Meswak, Dabur Oral Care Products, India) after discontinuing Babool toothpaste. Thus, it was highly probable that babul extract from the Babul tree “Acacia Arabia” was responsible for the gingival enlargement in the present case as all other constituents of both the herbal toothpastes are similar.

Figure 3.

Facial view of the gingiva after periodontal treatment (gingivectomy in the maxillary arch and left mandibular region)

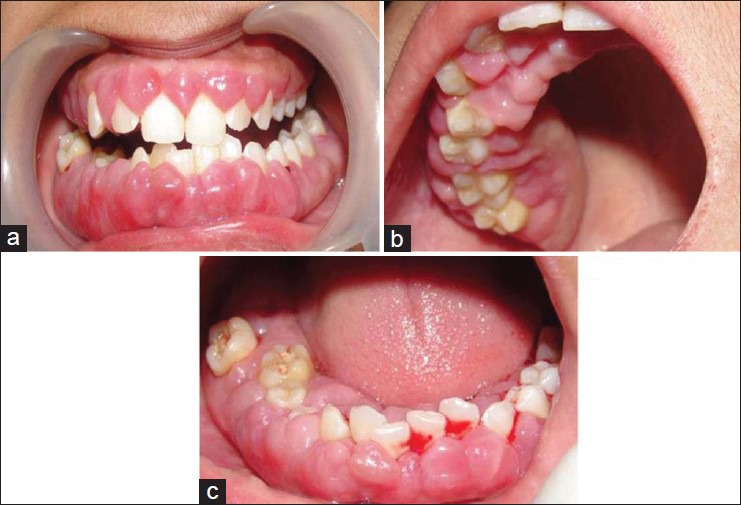

Figure 4.

(a) Facial; (b) maxillary occlusal and (c) mandibular occlusal view showing recurrence of gingival enlargement 12 months post-surgery

Figure 5.

Panoramic radiograph 1 year after the initial visit

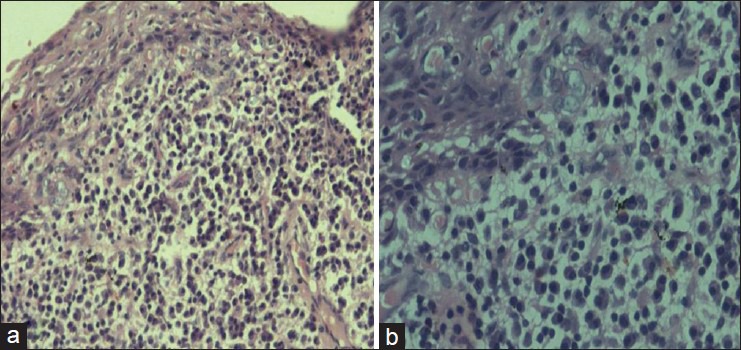

Figure 6.

(a) Biopsy comprised of plasma cell gingivitis with hyperplastic stratified squamous epithelium with dense plasma cells infiltrate in sub-epithelium (H and E, ×200); (b) High power magnification revealing abundant normal plasma cells (H and E, ×400)

Figure 7.

(a) Facial, (b) maxillary occlusal and (c) mandibular occlusal view of regression of enlargement after discontinuation of herbal toothpaste

Blood test (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) for allergy of toothpaste components disclosed very high level of allergen specific antibody and symptoms relation for Acacia (105 kUA/L; normal value < 0.35 kUA/L), which confirmed “Acacia” as causative allergen.

Right mandibular second molar with hopeless prognosis was extracted. Although pocket depth reduced significantly from 10-14 mm to 6-8 mm, but clinical attachment level was not reduced significantly. Surgical procedures were carried out on right molar region to treat AgP and residual enlargement. Patient was advised to continue with regular toothpaste.

Patient was recalled at 1, 3, 6 months and after that she was recalled at 6 months interval. No recurrence of gingival enlargement was noticed in both arches and probing depth ranged from 3 mm to 5 mm [Figure 8]. Panoramic radiograph showed no further progression of bone loss [Figure 9].

Figure 8.

Intraoral view after a follow-up of 1 year. No recurrence of gingival enlargement was seen

Figure 9.

Panoramic radiograph after 1 year follow-up showing no further progression of bone loss

DISCUSSION

The initial presentation of severe gingival enlargement associated with GAgP necessitated the formulation of an extensive differential diagnosis. Clinically, the enlarged gingiva in idiopathic gingival fibromatosis is firm and leathery in consistency and the histologic features are densely arranged collagen bundles and numerous fibroblasts; both of which differ from the features in this patient. Plaque induced gingivitis would normally involve the marginal gingiva alone and not the entire width of attached gingiva. In the present case, there was an inflammation of marginal and attached gingiva, which was not responding to local therapy and hence inconsistent with a plaque related etiology. Gingival hyperplasia is well-known consequence of administration of certain drugs, such as phenytoin, cyclosporine and nifedipine. The patient had not taken any of these drugs. Gingival enlargement due to scurvy was ruled out as the patient did not have any signs of scurvy, such as petechiae, ecchymoses, or spontaneous bruising of the extremities.

The presence of a large number of plasma cells can occasionally lead to a difficulty in distinguishing PCG from more exotic and rare plasma cell lesions affecting the gingiva such as extramedullary plasmacytoma, plasmacytosis of the gingiva and plasma-cell granuloma.[1] PCG is purely benign and the detection and elimination of exposure to the etiologic antigenic agent will bring about remission of the condition.

Histopathologically, it is important to differentiate PCG from various plasma cell tumors. Morphologically normal plasma cells are common constituents of allergic reactions. However, sheets of atypical plasma cells may represent multiple myeloma, Waldenström's macroglobulinemia and solitary plasmacytoma.[2] PCG is frequently associated with cheilitis and glossitis and sometimes with psoriasis,[6] but the patient did not exhibit any of these symptoms.

Marker and Krogdahl[4] sub-divide PCG into three types: (1) Caused by an allergen, (2) neoplastic and (3) unknown cause. Hedin et al.[6] reached the conclusion that PCG is the result of an allergic reaction to bacterial plaque, even though this had been eliminated by means of conventional periodontal treatment. Nitta et al.[7] reported marked inflammatory gingival enlargement with a predominance of plasma cells associated with rapidly progressive periodontitis, but were not able to identify the cause of the gingival enlargement. The present case belongs to type 1 as the changes had developed after prolonged use of herbal toothpaste containing “Acacia” for last 2 years. Amelioration of the gingival enlargement was obtained to a large extent when the use of the toothpaste was discontinued.

Acacia tree is a thorny, scraggly evergreen tree, native to Africa, Southern California and the Indian subcontinent. Various parts of this plant are used for medicinal purposes and as a preservative. Whole gum mixtures of Acacia have been shown to inhibit the growth of periodontopathic bacteria, including Porphyromonas gingivalis and Prevotella intermedia in vitro.[8] A significant number of this genus of plants bears pollen and has been reported to cause pollinosis or strong allergic reactions.[9] Recognition of “Acacia” extract used in herbal toothpaste as an allergen, which caused severe gingival enlargement was the important finding in this case.

Clinically, GAgP is characterized by generalized interproximal attachment loss affecting at least three permanent teeth other than first molars and incisors. Radiograph often shows progressive bone loss in spite of the apparent lack of local factors.[10] All these features were identifiable in the patient, so the diagnosis of GAgP in association with PCG was confirmed. In many types of gingival enlargement, the rapid loss of alveolar bone or attachment level is not commonly observed. In the present case, PCG was associated with GAgP, but it was difficult to retrace the clinical presentation and identify which of the two occurred first. Gingival enlargement as an allergic response to “Acacia” containing herbal toothpaste may be an aggravating factor resulting in exaggerated progressive bone loss. Deepened gingival pockets due to unusual gingival enlargement may have allowed subgingival periodontopathic bacteria to colonize and overgrow and the alveolar bone loss might then advance very rapidly.

CONCLUSION

This case underscores the necessity of a comprehensive history, examination and appropriate diagnostic tests in order to arrive at a definitive diagnosis and treatment plan for gingival conditions, which are refractory to conventional therapy. PCG is a hypersensitivity reaction to some antigen, often flavorings or spices. The importance of this lesion is that it may cause severe gingival inflammation, discomfort and bleeding and may mimic more serious conditions. Plaque control and conventional periodontal therapy alone will not cure this disease. Hence, the etiologic agent must be identified and the substance should be eliminated from its use. This report outlines a case of PCG which was brought on by the use of herbal toothpaste containing “Acacia” extract from the tree “Acacia Arabica” associated with AgP.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anil S. Plasma cell gingivitis among herbal toothpaste users: A report of three cases. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2007;8:60–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serio FG, Siegel MA, Slade BE. Plasma cell gingivitis of unusual origin. A case report. J Periodontol. 1991;62:390–3. doi: 10.1902/jop.1991.62.6.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lamey PJ, Lewis MA, Rees TD, Fowler C, Binnie WH, Forsyth A. Sensitivity reaction to the cinnamonaldehyde component of toothpaste. Br Dent J. 1990;168:115–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4807098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marker P, Krogdahl A. Plasma cell gingivitis apparently related to the use of khat: Report of a case. Br Dent J. 2002;192:311–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macleod RI, Ellis JE. Plasma cell gingivitis related to the use of herbal toothpaste. Br Dent J. 1989;166:375–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4806848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hedin CA, Karpe B, Larsson A. Plasma-cell gingivitis in children and adults. A clinical and histological description. Swed Dent J. 1994;18:117–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nitta H, Kameyama Y, Ishikawa I. Unusual gingival enlargement with rapidly progressive periodontitis. Report of a case. J Periodontol. 1993;64:1008–12. doi: 10.1902/jop.1993.64.10.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark DT, Gazi MI, Cox SW, Eley BM, Tinsley GF. The effects of Acacia arabica gum on the in vitro growth and protease activities of periodontopathic bacteria. J Clin Periodontol. 1993;20:238–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1993.tb00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boral D, Chatterjee S, Bhattacharya K. The occurrence and allergising potential of airborne pollen in West Bengal, India. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2004;11:45–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vishnoi SL, Phadnaik MB. Unusual gingival enlargement with aggressive periodontitis: A case report. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2010;11:049–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]