Abstract

Background:

Very few studies chart developmental pathways from early childhood to adolescent alcohol-related outcomes. We test whether measures of temperament collected from mothers at multiple assessments from 6 months through 5 years predict alcohol-related outcomes in mid-adolescence, the developmental pathways that mediate these effects, and whether there are gender differences in pathways of risk.

Methods:

Structural models were fit to longitudinal data from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, an epidemiological sample of pregnant women with delivery dates between April 1991 and December 1992, with children followed longitudinally. Temperamental characteristics were assessed at 6 time points from 6 to 69 months of age. Alcohol use and problems were assessed at age 15.5. Analyses here utilize data from 6,504 boys and 6,143 girls.

Results:

Childhood temperament prior to age 5 predicted adolescent alcohol use and problems at age 15.5 years, even after controlling for socio-demographic factors and parental alcohol problems. In both boys and girls, 2 largely uncorrelated and distinct temperament styles—children who were rated as having consistent emotional and conduct difficulties through age 5, and children who were rated as consistently sociable through age 5—both showed elevated rates of alcohol problems at age 15.5, but via different mediational pathways. In both genders, the association between emotional and conduct difficulties and alcohol problems was mediated through reduced conscientiousness and lower emotional stability. The association between sociability and alcohol problems was mediated through increased extraversion and sensation-seeking for both genders. Boys also showed mediation for sociability and alcohol outcomes through friendship characteristics, and girls through lower conscientiousness and reduced emotional stability.

Conclusions:

Our findings support multiple pathways to alcohol consumption and problems in adolescence. Some of these pathways are shared in boys and girls, while other risk factors are more salient in one gender or the other.

Keywords: ALSPAC, Temperament, Alcohol, Adolescence, Sex Differences

MUCH OF THE research on risk factors for alcohol use has focused on adolescence, due to the importance of this period for initiation and escalation of alcohol use (Windle et al., 2009). However, most risk and protective factors for alcohol use do not arise de novo in early adolescence but rather have roots in developmental processes stretching back into early childhood (Zucker et al., 2008). Clarifying the roots of these developmental patterns will be vital in acquiring a more complete understanding of the origins of risk factors for the acquisition and maintenance of patterns of alcohol use. During their very early years, children begin to develop skill sets and behavioral styles for regulating their emotions and behaviors and interacting with others. Through interactions between early temperamental styles and the child’s experience, the individual enters adolescence with personality characteristics and life experiences that have been accumulated over the first decade of life.

A number of studies now suggest that temperamental and behavioral characteristics from childhood predict much later alcohol use outcomes. Several large, longitudinal studies have found that externalizing behavior measured at ages 7 to 9 predict alcohol consumption in late adolescence and young adulthood (Dubow et al., 2008; Englund et al., 2008; Maggs et al., 2008; Pitkanen et al., 2008). A small number of studies have also found behavioral characteristics even earlier in life that predict subsequent alcohol-related outcomes. For example, in a longitudinal epidemiological sample of children born in the city of Dunedin from 1972 to 1973, observer ratings of undercontrol and of behavioral inhibition at age 3 predicted the diagnosis of alcohol use disorders at age 21 (Caspi et al., 1996). Studies by Zucker and colleagues of children of alcoholics have also found that early externalizing behavior and measures of undercontrol in preschool age children were related to alcohol use outcomes in early adolescence (Martel et al., 2009; Zucker, 2006). Thus, the handful of studies that have examined risk factors in childhood have found significant relationships with adolescent and adult alcohol use and/or misuse; however, most of these studies have analyzed data from late childhood (e.g., ages 8 to 9), with only a few notable exceptions examining earlier behavioral development. The findings from this small number of studies indicate that further exploration of early childhood risk factors and the pathways by which they are associated with the eventual emergence of risky behaviors in adolescence and young adulthood is an important area of study.

Data from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) provide a rare opportunity to address questions about longitudinal pathways of risk for alcohol use. This ongoing project has followed a large cohort of children and their parents from early in the mother’s pregnancy through childhood and adolescence, with assessments ongoing as the participants currently enter young adulthood. The study enrolled all pregnant mothers resident in a defined geographical area with expected dates of delivery between April 1, 1991, and December 31, 1992, and has collected comprehensive health-related information, from both the mothers and (when they were old enough) children. With this rich existent data set, we sought to ask: How early can we predict risk for adolescent alcohol involvement? We make use of measures of temperament collected from the mother at multiple assessments from 6 months through 5 years of age. Although we use the word temperament throughout this manuscript, we adopt a broad perspective and make use of all measures that index emotional and behavioral styles through the age of 5. From these measures, we attempt to predict self-reports of alcohol use and alcohol-related problems from the adolescents at age 15.5.

Additionally, we sought to understand factors that may mediate associations between very early childhood temperament and adolescent alcohol use. We focused on personality and peers. We examined personality because temperament is thought to encompass the affective, activational, and attentional core of personality. Temperament represents the individual differences in reactivity and self-regulation that arise very early in life, while personality consists of the more stable patterns of thoughts, emotions, and behaviors that subsequently emerge (Rothbart and Bates, 1998). Accordingly, we sought to examine whether any associations that might exist with very early childhood temperamental characteristics would be mediated through personality dimensions as measured later in life (early adolescence). A considerable literature connects personality traits to alcohol use (Littlefield and Sher, 2010), providing further rationale for testing whether personality mediates associations between early temperament and subsequent alcohol use.

Second, we tested whether associations between early temperament and subsequent alcohol use would be mediated through peer characteristics. Studies have consistently found that peer substance use and deviant peer affiliation is one of the strongest predictors of adolescent substance use (Dick et al., 2007; Simons-Morton et al., 2001; Wang et al., 1995; Windle, 2000). Association with deviant peers is not random, but rather reflects in part selection by the adolescent into antisocial peer groups based partly on their own predispositions (Dick et al., 2007; Harden et al., 2008; Kandel, 1978; Rose, 2002). Other aspects of peer relationships have also been shown to be important. For example, social rejection by peers predicts adolescent substance use in prospective studies (Dishion et al., 1995; Dodge et al., 2009). Transactional theory (Sameroff, 2009) suggests that features of the child’s interpersonal style and behavior may contribute to peer group rejection. The association between child characteristics and affilation with antisocial peers and/or having difficulty with peers, and the subsequent association of these variables with substance use led us to test whether aspects of the peer group may mediate potential associations between temperamental characteristics and substance use.

Finally, we ask whether there are gender differences in the mediational pathways from early child characteristics to adolescent alcohol-related outcomes. Mean differences in levels of alcohol use have been shrinking in industrialized countries as gender roles have begun to equalize (Rose et al., 2001); however, less clear is whether the relationships between risk and protective factors are the same for the sexes (Dodge et al., 2009). While several studies failed to find robust differences in predictors of alcohol involvement (Zucker, 2008), other studies report evidence for sex-specific risk factors, particularly with respect to the relative importance of internalizing factors and emotional distress as they relate to alcohol use in females (Hussong et al., 2008; Kokkevi et al., 2007). Many studies are underpowered to test for robust sex differences. With the large cohort of children followed in ALSPAC, we are able to address this question.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample Overview

The sample comprised participants from the ALSPAC (http://www.alspac.bris.ac.uk; Golding et al., 2001). ALSPAC is an ongoing population-based study investigating a wide range of environmental and other influences on the health and development of children. All pregnant women resident in the Avon district of South West England with an expected date of delivery between April 1, 1991, and December 31, 1992, were invited to participate in the ALSPAC. The achieved sample was 14,541 pregnant women (80% of those eligible) with 13,988 live infants at age 12 months. ALSPAC parents and children have been followed up regularly since recruitment, with data obtained through questionnaires completed by mothers, children, and teachers and through clinical assessments. The present analyses used data collected at months 6, 24, 38, 42, 57, and 69 (on early childhood temperament), friendship characteristics collected at age 10.5 years, and personality characteristics collected at ages 11.5 and 13 years. Alcohol use outcomes were assessed at age 15.5. The number of individuals with data for each of the above measures analyzed in this project is shown in Table 1. There were 12,647 individuals with data available on at least 1 time point: 6,504 (51%) of these individuals were male, and 6,143 (49%) were female. The majority of the sample (86%) was white (reflecting the relative homogeneity of the region from which the sample was drawn), 4% reported another ethnicity, and 10% of the sample had unknown ethnicity. There was considerable variability with respect to educational level: 3,482 (28%) of mothers had less than O level education (Ordinary Level; exams taken at the completion of legally required school attendance, equivalent to the present UK General Certificate of Secondary Education), 4,991 (40%) had O level education, and 3,703 (29%) had A level (Advanced Level; exams taken at age 18 years) or university education, with 471 missing. Full details of all measures, procedures, sample characteristics, and response rates are available at www.alspac.bris.ac.uk. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the ALSPAC Ethics and Law Committee and the Local Research Ethics Committee.

Table 1.

Number of Participants for the Measures Included in Analyses

| Assessment age | N | |

|---|---|---|

| Outcome variables | ||

| Alcohol consumption/problems | 15.5 years | 4,594 |

| Temperament variables | ||

| Carey Infant Temperament Scale | 6 months | 11,416 |

| Carey Infant/Toddler Temperament Scale |

24 months | 10,335 |

| Emotionality, Activity, and Sociability (EAS) Scale |

38 months | 10,079 |

| Revised Rutter Parent Scale for Preschool Children |

42 months | 10,024 |

| EAS Scale | 57 months | 9,423 |

| EAS Scale | 69 months | 8,615 |

| Mediating variables | ||

| Friendship problems | 10.5 years | 7,377 |

| Friends’ antisocial behavior | 10.5 years | 7,486 |

| Sensation-seeking | 11.5 years | 6,982 |

| Extraversion | 13 years | 5,829 |

| Agreeableness | 13 years | 5,731 |

| Conscientiousness | 13 years | 5,582 |

| Emotional stability | 13 years | 5,651 |

| Total participants with data | Any | 12,647 |

Measures

Early Childhood Temperament

Information about temperament was reported on by the mother at 6 separate assessments through the child’s fifth year of age. Developmentally appropriate instruments were used. From age 6 to 24 months, the Carey Infant (Toddler) Temperament (CIT) Scale (Carey and McDevitt, 1978) was employed, which contains 9 subscales (intensity, activity, rhythmicity, approach, adaptability, mood, persistence, distractibility, and threshold). The Emotionality, Activity, and Sociability (EAS) Temperament Scale (Buss and Plomin, 1984) was administered at 38, 57, and 69 months and consists of 4 subscales (emotionality, shyness, sociability, and activity). At 42 months, the Revised Rutter Parent Scale for Preschool Children (Elander and Rutter, 1996) was also administered, which assesses total behavioral difficulties, prosocial behavior, hyperactivity, emotional symptoms, conduct problems, and peer problems.

Alcohol Use/Problems

At the age 15.5 in-person clinic, ALSPAC subjects were asked a series of questions about their alcohol consumption and associated alcohol-related symptoms/problems that correspond relatively well to the DSM-IV criteria for alcohol abuse and dependence. These items were extracted from the Semi-Structured Assessment of the Genetics of Alcoholism interview, developed by the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism (Bucholz et al., 1994; Hesselbrock et al., 1999). The alcohol items are listed in Table 2, along with mean scores for males and females.

Table 2.

Means for Alcohol-Related Items at Age 15.5, Along with Factor Loadings from the Exploratory Factor Analysis

| Male |

Female |

Alcohol factors |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | |

| Number of occasions lifetime had a full drink of alcohol | 5.21 | 1.818 | 5.12 | 1.770 | 0.84 | −0.12 |

| Largest number of whole drinks ever consumed in 24 hours | 8.59 | 8.571 | 7.87 | 7.515 | 0.67 | 0.04 |

| Number of drinks on a typical drinking day, last 6 months | 2.73 | 4.408 | 2.71 | 3.482 | 0.43 | 0.16 |

| Number of times 5+ full drinks in 24 hours, last 2 years | 3.37 | 2.005 | 3.31 | 1.937 | 0.82 | 0.01 |

| Number of times set a limit on drinking but drank more, last 2 years | 1.74 | 1.482 | 1.87 | 1.508 | 0.44 | 0.28 |

| Number of times felt need to stop drinking or cut back, last 2 years | 1.39 | 1.086 | 1.40 | 1.065 | 0.23 | 0.36 |

| Number of times spent a great deal of their day drinking alcohol, last 2 years | 1.27 | 0.982 | 1.24 | 0.903 | 0.07 | 0.66 |

| Number of times not done things would usually do because would rather drink, last 2 years | 1.22 | 0.877 | 1.23 | 0.864 | −0.01 | 0.64 |

| Number of times continued to drink even though it was causing problems, last 2 years | 1.11 | 0.620 | 1.12 | 0.635 | −0.13 | 0.74 |

| Number of times unable to keep up with school work/sports/job because of drinking, last 2 years | 1.06 | 0.475 | 1.05 | 0.457 | −0.18 | 0.64 |

| Number of times used alcohol in a dangerous situation, last 2 years | 1.18 | 0.798 | 1.08 | 0.494 | −0.02 | 0.56 |

| Number of times accidentally physically hurt while drinking, last 2 years | 1.21 | 0.737 | 1.27 | 0.804 | 0.15 | 0.54 |

| Number of times parents or friends complained about drinking, last 2 years | 1.19 | 0.736 | 1.19 | 0.742 | 0.06 | 0.54 |

| Number of times got into fights when drinking, last 2 years | 1.22 | 0.837 | 1.13 | 0.531 | 0.09 | 0.52 |

| Number of times had a problem with the police because of drinking, last 2 years | 1.18 | 0.725 | 1.14 | 0.610 | 0.03 | 0.58 |

| Number of times drank so much could not remember things, last 2 years | 1.29 | 0.851 | 1.43 | 0.929 | 0.28 | 0.41 |

Means for which significant (p < 0.05) differences existed for males and females are shown in italics. Factor loadings > 0.3 shown in bold italics.

Possible Mediating Variables

Personality

At the age 13 in-person assessment, a personality battery was self-administered to the young person via computer using the International Personality Item Pool (Ehrhart et al., 2008; Goldberg, 1999), which assesses the big 5 personality characteristics: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional Stability (e.g., reverse of neuroticism), and Intellect/Imagination (e.g., openness). Only the first 4 characteristics were hypothesized to play a potential mediating role between childhood temperament and alcohol use and accordingly were included in analyses. Sensation-seeking was assessed at age 11.5 using a modified version of Arnett’s Inventory of Sensation Seeking (Arnett, 1994).

Friendship Characteristics

Study children attended a research clinic at age 10.5 where they reported on their satisfaction/engagement with their friends, based on a series of questions from the Cambridge Hormones and Moods project Friendship questionnaire (Goodyer et al., 1987). In addition, they reported on deviant behaviors in their friends, based on the following list of behaviors: skipped school, told off by teacher, destroyed something for fun, set fire to something, stolen something, gotten into fights/cruel to animals, trouble with the police, smoked cigarettes, drunk alcohol without parental permission, been offered illegal drugs, and smoked cannabis.

Covariates

We included several sociodemographic covariates in the model, including child’s ethnicity, educational level for mother and partner, and occupational status for mother and partner (as described in Melotti et al., 2011, 2013). In addition, we included indices of parental alcohol consumption and problems, as these are known to relate to both early temperament and adolescent substance use (Chassin et al., 1996; Leonard et al., 2000), and this allowed us greater confidence that any detected associations would not be due to correlated parental alcohol use. Information on parental alcohol use was collected at multiple time points in ALSPAC. A 5-factor solution was derived based on all available information (as detailed in Kendler et al., manuscript submitted for publication), with the factors corresponding to alcohol consumption by mother, alcohol consumption by mother during pregnancy, problem drinking in mother, alcohol consumption by partner, and problem drinking in partner. The resultant factor-derived scores were included as covariates in all structural equation models.

Model Fitting

Theoretically driven multiple mediation models (see Fig. 1) were tested using Mplus, Version 6.1 (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2011) to assess the effects of early childhood temperament on adolescent alcohol use/problems, both directly and indirectly through personality attributes and peer characteristics, in order to test the intermediary role of personality/peers in links between early temperament and later drinking behaviors. Alcohol and temperament factor scores were calculated using the full sample with mediation allowed to vary for males and females. Covariates, as detailed above, were also included. In all models, path coefficients and standard errors were estimated while accounting for nonindependence of observations due to complex sampling (i.e., individuals nested within sibships). A robust maximum likelihood estimator was employed to accommodate missing data. Mplus applies the product of coefficients strategy (Mackinnon et al., 2002; Preacher and Hayes, 2004) in the assessment of indirect effects. In the simple case, partial mediation by a single variable (i.e., a partial indirect effect) is evaluated in relation to the Z-distribution, with the ratio of the product of the component path coefficients (i.e., the a and b paths in the traditional causal steps approach; Baron and Kenny, 1986; Judd and Kenny, 1981) over the normal-theory standard error for that product. When assessing the total indirect effect operating through multiple mediators, the sum of the products of those coefficients taken over the square root of the asymptotic variance of the sum of those products provides a ratio to be evaluated in relation to the Z-distribution.

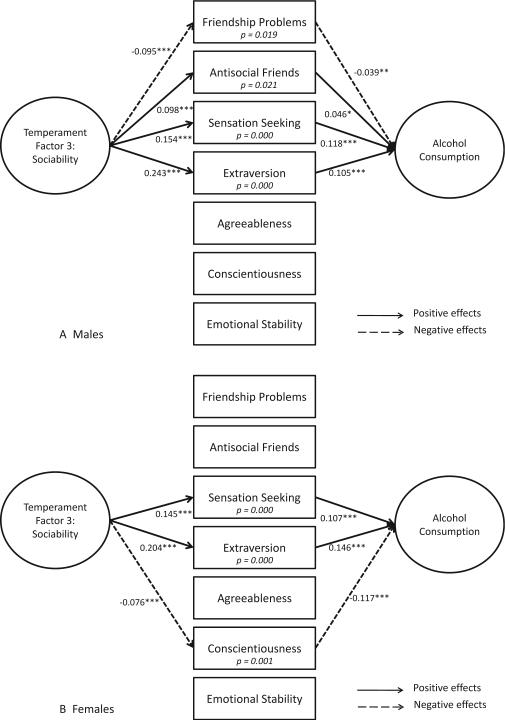

Fig. 1.

Path coefficients for the significant mediated pathways to alcohol consumption from sociability for males (A) and females (B). Asterisks indicate the significance of individual pathways: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Measurement Models

Adolescent Drinking

Exploratory factor analysis conducted with the alcohol items identified 2 factors, loadings for which are shown in Table 2. The first factor consisted of items related to alcohol consumption, with the highest loadings (>0.80) for the number of times the participant reporting drinking alcohol and engaging in binge drinking. The second factor consisted of items related to problems associated with alcohol use, with the highest loading on number of times the participant continued to drink even though it was causing problems. Accordingly, we refer to the first alcohol factor as alcohol consumption and the second factor as alcohol problems throughout this manuscript. The correlation between the factors was +0.66.

Temperament

Exploratory factor analysis conducted with the scores from all temperament scales available through age 5 resulted in a 3-factor solution based on the scree plots’ jump in eigenvalues. Factor loadings are shown in Table 3. The first factor contained items from the CIT Scale at 6 months, with the highest loadings for low adaptability and low approachability. The second and third factors consisted of constructs measured across multiple time points and using different scales, indicating more stable temperament patterns that persisted across early childhood. Factor 2 consisted of measures that reflected both emotional and conduct difficulties across 5 assessments between 24 and 69 months of age. Factor 3 consisted of items that indexed high activity, low shyness, and high sociability across the same 5 assessments between 24 and 69 months of age. Factors are referred to by the italicized indicator in tables and text for ease of interpretation.

Table 3.

Factor Loadings from Exploratory Factor Analysis of All Temperament-Related Characteristics Collected in Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children Through Age 5

| Factor |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Age (months) |

Scale | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| CIT | 6 | Rhythmicity score (rev) |

0.371 | 0.077 | −0.011 |

| CIT | 6 | Approach score (rev) |

0.797 | −0.012 | −0.042 |

| CIT | 6 | Adaptability score (rev) |

0.806 | −0.014 | 0.002 |

| CIT | 6 | Mood score | 0.608 | 0.181 | 0.01 |

| CIT | 6 | Persistence score (rev) |

0.371 | 0.119 | −0.008 |

| CIT | 6 | Distractibility score (rev) |

0.619 | 0.07 | −0.01 |

| CIT | 24 | Adaptability score (rev) |

0.166 | 0.593 | 0.192 |

| CIT | 24 | Intensity score | 0.046 | 0.497 | 0.308 |

| CIT | 24 | Mood score | 0.252 | 0.595 | −0.003 |

| CIT | 24 | Persistence score (rev) |

0.093 | 0.363 | 0.131 |

| EAS | 38 | Emotionality | −0.011 | 0.596 | −0.058 |

| RR | 42 | Emotional difficulties score |

−0.059 | 0.508 | −0.224 |

| RR | 42 | Conduct difficulties score |

−0.024 | 0.462 | 0.218 |

| RR | 42 | Hyperactivity score |

−0.015 | 0.461 | 0.333 |

| RR | 42 | Prosocial score | −0.077 | −0.282 | 0.138 |

| EAS | 57 | Emotionality | −0.062 | 0.614 | −0.053 |

| EAS | 69 | Emotionality | −0.067 | 0.599 | −0.043 |

| CIT | 24 | Activity score | 0.013 | 0.471 | 0.479 |

| CIT | 24 | Approach score (rev) |

0.164 | 0.2 | − 0.383 |

| EAS | 38 | Activity | −0.071 | 0.046 | 0.607 |

| EAS | 38 | Shyness | 0.054 | 0.224 | − 0.616 |

| EAS | 38 | Sociability | 0.008 | 0.033 | 0.55 |

| EAS | 57 | Shyness | 0.007 | 0.222 | − 0.651 |

| EAS | 57 | Sociability | 0.027 | −0.028 | 0.614 |

| EAS | 57 | Activity | −0.044 | 0.01 | 0.648 |

| EAS | 69 | Shyness | −0.013 | 0.214 | − 0.629 |

| EAS | 69 | Sociability | 0.049 | −0.046 | 0.588 |

| EAS | 69 | Activity | −0.024 | 0.007 | 0.622 |

| CIT | 6 | Activity score | −0.02 | 0.187 | 0.247 |

| CIT | 6 | Intensity score | 0.141 | 0.055 | 0.201 |

| CIT | 6 | Threshold score | 0.213 | 0.001 | 0.116 |

| CIT | 24 | Rhythmicity score (rev) |

0.12 | 0.217 | 0.052 |

| CIT | 24 | Distractibility score (rev) |

0.017 | 0.11 | 0.142 |

| CIT | 24 | Threshold score | 0.068 | −0.013 | 0.001 |

CIT, Carey Infant Temperament; EAS, Emotionality Activity and Sociability; RR, Revised Rutter; (rev), indicates reverse coding. Factor loadings > 0.3 shown in bold italics.

Correlations between the temperament factors were generally low, with the exception of low adaptability and emotional and conduct difficulties (r = 0.39). The correlation between low adaptability and sociability was −0.12. The correlation between emotional and conduct difficulties and sociability was −0.16.

Full Structural Model

Table 4 shows the associations between each of the temperament factors with the 2 alcohol factors, as well as whether that effect was mediated by the intervening variables (total indirect effect), and whether a direct (residual) effect of the temperament factor on the alcohol factor remained after accounting for the mediation effects (remaining direct effect). The proportion of the total effect that was mediated by the intervening variables is also reported for significant effects. The total indirect effect is an omnibus test for mediation, that is, it provides an overall test of mediation taking into account all the mediating variables in the model, not specific to any one mediator. The specific variables for which there was mediation when the overall indirect effect was significant are shown in the corresponding figures, along with the path coefficients for significantly mediated pathways. The p-value indicated inside the intervening variable boxes indicates the p-value associated with the mediation effect through that variable for significantly mediated effects. Note that the model was fit in a single step (separately for males and females), but the results for each pair of temperament–alcohol factor associations are broken out into a series of figures to make them interpretable.

Table 4.

Direct and Indirect Effects Between Each of the Temperament and Alcohol Factors, Shown for Males (A) and Females (B)

| Total effect |

Total indirect effect |

Remaining direct effect |

Mediated proportion of total effect |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol factor | Temperament factor | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | |

| (A) Males N = 4,318 | |||||||||||

| Consumption | Low adaptability, 6 months | −0.002 | 0.015 | 0.896 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.640 | −0.004 | 0.015 | 0.770 | |

| Emotional and conduct difficulties | −0.063 | 0.015 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.636 | −0.066 | 0.015 | 0.000 | ||

| Sociability | 0.274 | 0.015 | 0.000 | 0.050 | 0.007 | 0.000 | 0.224 | 0.016 | 0.000 | 0.182 | |

| Problems | Low adaptability, 6 months | −0.001 | 0.016 | 0.949 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.474 | −0.004 | 0.016 | 0.810 | |

| Emotional and conduct difficulties | 0.041 | 0.018 | 0.019 | 0.012 | 0.005 | 0.014 | 0.029 | 0.018 | 0.110 | 0.293 | |

| Sociability | 0.112 | 0.018 | 0.000 | 0.027 | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.086 | 0.019 | 0.000 | 0.241 | |

| (B) Females N = 4,091 | |||||||||||

| Consumption | Low adaptability, 6 months | 0.044 | 0.017 | 0.010 | −0.009 | 0.006 | 0.128 | 0.053 | 0.017 | 0.002 | |

| Emotional and conduct difficulties | −0.070 | 0.017 | 0.000 | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.228 | −0.079 | 0.017 | 0.000 | ||

| Sociability | 0.262 | 0.015 | 0.000 | 0.059 | 0.007 | 0.000 | 0.202 | 0.016 | 0.000 | 0.225 | |

| Problems | Low adaptability, 6 months | 0.026 | 0.019 | 0.171 | −0.007 | 0.005 | 0.121 | 0.033 | 0.019 | 0.081 | |

| Emotional and conduct difficulties | 0.039 | 0.020 | 0.051 | 0.011 | 0.005 | 0.041 | 0.028 | 0.020 | 0.159 | ||

| Sociability | 0.120 | 0.015 | 0.000 | 0.042 | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.078 | 0.017 | 0.000 | 0.350 | |

Significant effects p < 0.05 are indicated in bold.

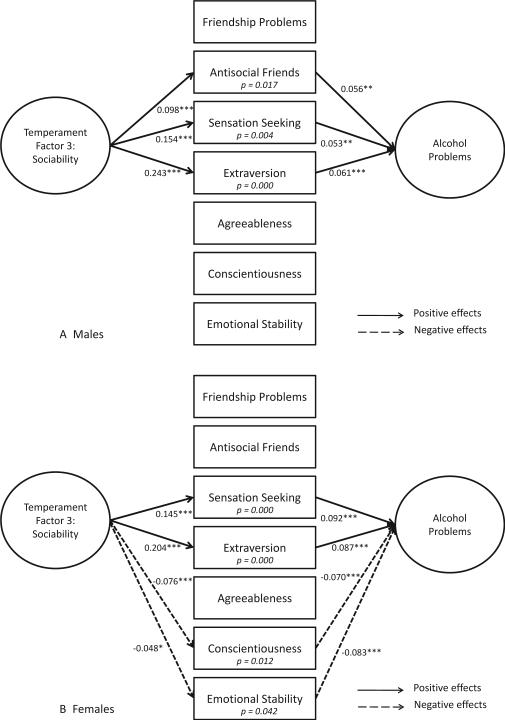

The 2 temperament factors that were indexed stably across time, emotional and conduct difficulties, and sociability were both significantly associated with alcohol consumption and problems in both males and females. The association between emotional and conduct difficulties and consumption was not mediated through personality or peer characteristics for either gender and surprisingly had a protective effect on consumption, whereby both boys and girls who had elevated levels of emotional and conduct difficulties showed lower levels of alcohol consumption. Sociability was related to increased consumption, with mediation through personality and peers (Fig. 1). Although mediation was significant for both boys and girls (accounting for 18 and 23% of the total effect, respectively), the mediating variables partially differed. Sociability was associated with consumption through higher sensation-seeking and higher extraversion in both boys and girls, but boys showed additional mediation through antisocial friends and friendship problems, whereas girls showed mediation through reduced conscientiousness. The direction of effect associated with friendship problems in boys was that increased sociability was associated with reduced friendship problems.

The pattern of mediation between sociability and problems was very similar to that observed with consumption for both boys and girls, with the exception that reduced friendship problems were not a significant mediator to problems in boys and that reduced emotional stability was an additional mediator between sociability and alcohol problems in girls (Fig. 2). The mediating variables accounted for a slightly higher percentage of the total effect in girls than in boys (35% compared with 24%). The path coefficients suggested that extraversion and sensation-seeking were somewhat more strongly associated with alcohol consumption than with problems.

Fig. 2.

Path coefficients for the significant mediated pathways to alcohol problems from sociability for males (A) and females(B). Asterisks indicate the significance of individual pathways: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

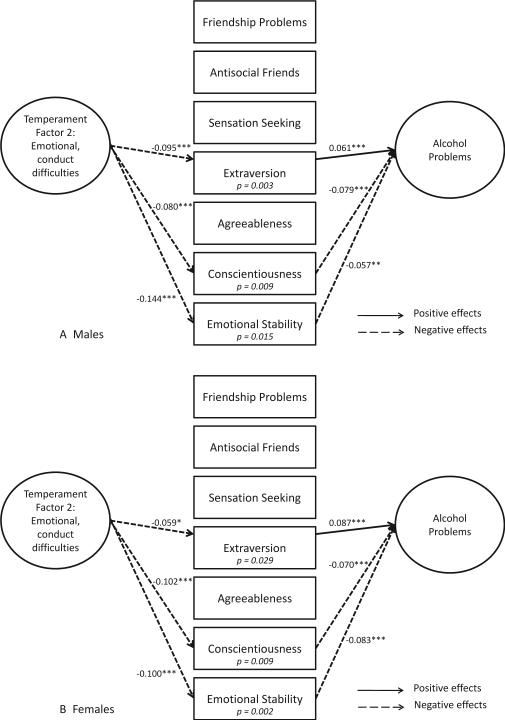

Finally, emotional and conduct difficulties were positively associated with alcohol problems in both boys and girls. The association was significantly mediated through personality characteristics in both genders, with a similar set of mediating variables (Fig. 3): in both sexes, the association was mediated through lower conscientiousness and lower emotional stability. In both sexes, emotional and conduct difficulties were also associated with lower levels of extraversion, which had a protective effect on alcohol problems; however, the overall association between emotional and conduct problems and alcohol problems was positive (more emotional and conduct difficulties more alcohol problems).

Fig. 3.

Path coefficients for the significant mediated pathways to alcohol problems from emotional and conduct difficulties for males (A)and females (B). Asterisks indicate the significance of individual pathways: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

This study represents, to our knowledge, the largest effort to date to understand early childhood predictors of adolescent alcohol use and the pathways through which those associations arise. We use data from the large epidemiological ALSPAC cohort of >12,000 children, containing multiple maternal reports of childhood temperament from 6 months of age to 69 months of age, and self-reports of adolescent alcohol use and problems at age 15.5 years. Several interesting findings emerge. First, temperament characteristics found in very early childhood are significantly associated with alcohol use more than 15 years later, even after controlling for parental alcohol consumption/problems and sociodemographic factors. While a small number of longitudinal studies have examined early childhood factors (e.g., among 5- to 6-year-olds; Kaplow et al., 2002; Masse and Tremblay, 1997), we extend this literature by studying infancy through age 5 and find that temperamental characteristics that can be stably indexed even earlier in life relate to adolescent alcohol problems. Second, the temperament styles associated with subsequent adolescent alcohol-related outcomes are very different and largely uncorrelated. Children who are rated as consistently sociable through age 5 and children who are rated as having consistent emotional and conduct difficulties through age 5 both show elevated rates of alcohol problems at age 15.5. Interestingly, the association was mediated through different pathways. Sociability was associated with increased problems through increased extraversion and sensation-seeking in both boys and girls, whereas emotional and conduct difficulties were associated with increased problems through reduced conscientiousness and lower emotional stability in both sexes. Accordingly, our findings support multiple pathways, through different temperamental and personality styles, to problematic alcohol use.

It is striking that such different and largely uncorrelated temperament styles both would be associated with adolescent alcohol problems. Multiple pathways to alcohol problems are usually discussed in the context of internalizing and externalizing pathways (Zucker et al., 2008). However, our findings suggest a more nuanced understanding of different pathways to alcohol problems when starting in very early childhood. We do not find a clear externalizing/internalizing distinction in our empirical evaluation of very early childhood temperament, with both emotionality and other indices of conduct difficulties as indexed before the age of 5 all loading together. A further point is that the other temperament style associated with alcohol problems in the ALSPAC sample (sociability) is not one that is on the surface maladaptive. In studying risk factors for adolescent alcohol consumption and problems, it is important to remember that alcohol use is largely a social phenomenon in adolescence. Experimentation in adolescence is normative. More than a decade ago, a longitudinal study of drug use among adolescents followed from preschool through age 18 (Shedler and Block, 1990) showed that adolescents who had never tried any drug by age 18 were more likely to be anxious, emotionally constricted, and lacking in social skills. Adolescents who engaged in some drug experimentation were actually the best adjusted (Shedler and Block, 1990). This phenomenon may be reflected in the association we observed in males between increased sociability and reduced friendship problems (which was then associated with increased consumption but not problems). It may also be influencing the inverse relationship observed between increased conduct, emotional difficulties and decreased alcohol consumption. It is possible that the difficult temperamental style evidenced by children with emotional and conduct difficulties leads to less opportunity to engage in normative alcohol consumption with peers. This, coupled with emotional distress and problems, may lead to increased alcohol-related problems, even while these characteristics are related to decreased normative adolescent experimentation/consumption. Accordingly, some children may be at higher risk for developing problems through temperamental problems evident early in life, while other adolescents may engage in risky behavior and subsequently be at risk for alcohol-related problems by virtue of their social nature and not as a result of a predisposition to problematic behavior per se. These different pathways to alcohol problems indicate that we need to be cognizant of different groups of children at risk for alcohol-related problems in adolescence, as this is likely to impact the ability to deliver effective prevention and intervention programming.

We observed both similarities and differences between males and females in the pathways mediating early temperamental styles and adolescent alcohol outcomes. The pathway by which conduct and emotional difficulties and alcohol problems were mediated was identical in boys and girls—via reduced conscientiousness and decreased emotional stability (with an inverse relationship with extraversion also observed in both sexes). The association between sociability and consumption/problems also showed parallel mediating variables between the genders; both sexes showed mediation through sensation-seeking and extraversion. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have concluded that risk factors for substance use in girls and boys are often remarkably similar (Costello et al., 1999; Zucker, 2008). However, some notable differences were also observed: boys showed additional mediation between sociability and consumption/problems through friendship characteristics that was not present in girls, and girls showed mediation through reduced conscientiousness and lower emotional stability that was not associated with sociability in boys. Both temperamental styles showed mediation through reduced emotional stability in girls. This supports previous literature suggesting that girls in particular may be more prone to adopt problematic alcohol use as a means of dealing with emotional distress and is consistent with the higher rates of comorbid depression and alcohol problems observed in women in adulthood (Grant et al., 2004). It is also consistent with methods of subtyping alcohol problems in which alcohol use associated with depression and anxiety is more prevalent in women (Cloninger, 1987). The association with peer characteristics in boys only was unexpected. Some of the pivotal work on the role of peer deviance in substance use has been done in males (Dishion et al., 1995), but in other work, there has been evidence for stronger genetic influences on peer substance use, and stronger associations with the adolescent's own substance use, in females (Dick et al., 2007). The latter study examined peer influences later in adolescence, so it is possible that the relative influence of peer characteristics may vary for the sexes at different developmental stages. This warrants further, more systematic, exploration in future research.

These findings should be interpreted in the context of certain strengths and weaknesses. One strength is that the analyses are cross-reporter, from mother reports of early temperament to child reports of adolescent alcohol use; therefore, correlated rater bias is not an issue. However, a limitation of these findings is that all reports on early temperament derive from the mother. It is at least encouraging that the 2 temperament factors associated with the alcohol factors embody constructs that are stably indexed across multiple assessments and using different measures. Second, although ALSPAC is a large epidemiological cohort, with data at any one point available on >12,000 individuals, there are considerable missing data. Alcohol-related outcome data at age 15.5 were available on only 4,594 individuals. Analytic methods were used to account for missing data and make use of all available data. ALSPAC is particularly well suited to data imputation methods, which are most accurate when large amounts of auxiliary data are available for the prediction model, as is the case in ALSPAC. However, continued participation in ALSPAC is known to be correlated with child sex and ethnicity (females and whites are more likely to continue participation), as well as household income, with low-income individuals being less likely to have sustained participation (Boyd et al., 2013). Finally, we note that rates of alcohol use are higher among adolescents in the United Kingdom as compared to the United States (Hibell et al., 2011; Johnston et al., 2011). By the age 15.5 assessment, virtually all of the ALSPAC participants (99.5%) report that they have had a full drink of alcohol, with 77% reporting at least 1 episode of binge drinking and 69% reporting that they have at least 1 time thought that they should cut back on their drinking. However, a recent report of substance use among 15- to 16-year-old individuals from 36 European countries found that alcohol use in the United Kingdom was only slightly above average compared with other European countries (Hibell et al., 2011).

In summary, using data from the large epidemiological ALSPAC cohort, we find that childhood temperament prior to age 5 predicts adolescent alcohol use and problems at age 15.5 years. Two uncorrelated and distinct temperament styles—children who are rated as consistently sociable through age 5 and children who are rated as having consistent emotional and conduct difficulties through age 5—both show elevated rates of alcohol problems at age 15.5. Each of these early temperament styles is associated with different personality factors in mid-adolescence: the association between emotional and conduct difficulties and alcohol problems is mediated through decreased conscientiousness and reduced emotional stability, and the association between sociability and alcohol problems is mediated through sensation-seeking and extraversion. The pathways by which sociability was associated with alcohol consumption/problems also showed some gender-specificity: Boys showed additional mediation through friendship characteristics and girls showed additional mediation through reduced conscientiousness and decreased emotional stability. Our findings support multiple pathways to alcohol consumption and problems in adolescence, with some of the mediating factors being sex specific. Prevention programming should take into account the multiple routes by which individuals can arrive at problematic alcohol use, and the extent to which boys and girls may be more or less susceptible to different risk factors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are extremely grateful to all the families who took part in this study, the midwives for their help in recruiting them, and the whole ALSPAC team, which includes interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, receptionists, and nurses. The UK Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust (Grant ref: 092731) and the University of Bristol provide core support for ALSPAC. This publication is the work of the authors, and DMD and KSK will serve as guarantors for the contents of this article. This work was specifically funded by R01AA018333 (DMD and KSK) and K02AA018755 (DMD).

REFERENCES

- Arnett J. Sensation seeking: a new conceptualization and a new scale. Personality Individ Differ. 1994;16:289–296. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator mediator variable distinction in social psychological-research—conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd A, Golding J, Macleod J, Lawlor DA, Fraser A, Henderson J, Molloy L, Ness A, Ring S, Smith Davey G. Cohort profile: the ‘children of the 90s’—the index offspring of the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:111–127. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucholz KK, Cadoret R, Cloninger CR, Dinwiddie SH, Hesselbrock VM, Nurnberger JI, Reich T, Schmidt I, Schuckit MA. A new, semistructured psychiatric interview for use in genetic-linkage studies—a report on the reliability of the SSAGA. J Stud Alcohol. 1994;55:149–158. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss A, Plomin R. Temperament: Early Developing Personality Traits. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Carey WB, McDevitt SC. Revision of infant temperament questionnaire. Pediatrics. 1978;61:735–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Newman DL, Silva PA. Behavioral observations at age 3 years predict adult psychiatric disorders—longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:1033–1039. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830110071009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Curran PJ, Hussong AM, Colder CR. The relation of parent alcoholism to adolescent substance use: a longitudinal follow-up study. J Abnorm Psychol. 1996;105:70–80. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger C. Neurogenetic adaptive mechanisms in alcoholism. Science. 1987;236:410–416. doi: 10.1126/science.2882604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Federman E, Angold A. Development of psychiatric comorbidity with substance abuse in adolescents: effects of timing and sex. J Clin Child Psychol. 1999;28:298–311. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp280302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Pagan JL, Holliday C, Viken R, Pulkkinen L, Kaprio J, Rose RJ. Gender differences in friends’ influences on adolescent drinking: a genetic epidemiological study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:2012–2019. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Capaldi D, Spracklen KM, Li F. Peer ecology of male adolescent drug use. Dev Psychopathol. 1995;7:803–824. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Malone PS, Lansford JE, Miller S, Pettit GS, Bates J. A dynamic cascade model of the development of substance-use onset. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 2009;74:vii–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2009.00528.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubow EF, Boxer P, Huesmann LR. Childhood and adolescent predictors of early and middle adulthood alcohol use and problem drinking: the Columbia County Longitudinal Study. Addiction. 2008;103:36–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhart KH, Roesch SC, Ehrhart MG, Kilian B. A test of the factor structure equivalence of the 50-item IPIP Five-factor model measure across gender and ethnic groups. J Pers Assess. 2008;90:507–516. doi: 10.1080/00223890802248869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elander J, Rutter M. Use and development of the Rutter parents’ and teachers’ scales. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1996;6:63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Englund MM, Egeland B, Oliva EM, Collins WA. Childhood and adolescent predictors of heavy drinking and alcohol use disorders in early adulthood: a longitudinal developmental analysis. Addiction. 2008;103:23–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02174.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR. A broad-bandwidth, public-domain, personality inventory measuring the lower-level facets of several five-factor models. In: Mervielde I, Deary I, DeFruyt F, Ostendorf F, editors. Personality Psychology in Europe. Vol. 7. Tilburg University Press; Tilburg, The Netherlands: 1999. pp. 7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Golding J, Pembrey M, Jones R, Team AS. ALSPAC-The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children—I. Study methodology. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2001;15:74–87. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodyer IM, Kolvin I, Gatzanis S. The impact of recent undesirable life events on psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;151:179–184. doi: 10.1192/bjp.151.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, Pickering RP, Kaplan K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden KP, Hill JE, Turkheimer E, Emery RE. Gene-environment correlation and interaction in peer effects on adolescent alcohol and tobacco use. Behav Genet. 2008;38:339–347. doi: 10.1007/s10519-008-9202-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesselbrock M, Easton C, Bucholz KK, Schuckit M, Hesselbrock V. A validity study of the SSAGA—a comparison with the SCAN. Addiction. 1999;94:1361–1370. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94913618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibell B, Guttormsson U, Ahlstrom S, Balakireva O, Bjarnason T, Kokkevi A, Kraus L. The 2011 ESPAD Report: substance use among students in 36 European countried. 2011 2012 May 31; Available at: http://www.espad.org/Uploads/ ESPAD_reports/2011/The_2011_ESPAD_Report_FULL_2012_10_29.pdf.

- Hussong AM, Flora DB, Curran PJ, Chassin L, Zucker R. Defining risk heterogeneity for internalizing symptoms among children of alcoholic parents. Dev Psychopathol. 2008;20:165–193. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg J. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2010: Volume II, College Students and Adults Ages 19–50. Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; Ann Arbor: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Judd CM, Kenny DA. Process analysis—estimating mediation in treatment evaluations. Eval Rev. 1981;5:602–619. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB. Similarity in real-life adolescent friendship pairs. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1978;36:306–312. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplow JB, Curran PJ, Dodge KA, The Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group Child, parent, and peer predictors of early-onset substance use: a multi-site longitudinal study. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2002;30:199–216. doi: 10.1023/a:1015183927979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokkevi A, Richardson C, Florescu S, Kuzman M, Stergar E. Psychosocial correlates of substance use in adolescence: a cross-national study in six European countries. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Das Eiden R, Wong MM, Zucker RA, Puttler LI, Fitzgerald HE, Hussong AM, Chassin L, Mudar P. Developmental perspectives on risk and vulnerability in alcoholic families. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:238–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Sher KJ. The multiple, distinct ways that personality contributes to alcohol use disorders. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2010;4:767–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00296.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggs JL, Patrick ME, Feinstein L. Childhood and adolescent predictors of alcohol use and problems in adolescence and adulthood in the National Child Development Study. Addiction. 2008;103:7–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel MM, Pierce L, Nigg JT, Jester JM, Adams KM, Pulttler LI, Buu A, Fitzgerald HE, Zucker R. Temperament pathways to childhood disruptive behavior and adolescent substance abuse: testing a cascade model. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2009;37:363–373. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9269-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masse LC, Tremblay RE. Behavior of boys in kindergarten and the onset of substance use during adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:62–68. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830130068014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melotti R, Heron J, Hickman M, Macleod J, Araya R, Lewis G, Cohort AB. Adolescent alcohol and tobacco use and early socioeconomic position: the ALSPAC birth cohort. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e948–e955. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melotti R, Lewis G, Hickman M, Heron J, Araya R, Macleod J. Early life socio-economic position and later alcohol use: birth cohort study. Addiction. 2013;108:516–525. doi: 10.1111/add.12018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus Users’s Guide. 6th Muthéen &Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998–2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pitkanen T, Kokko K, Lyyra AL, Pulkkinen L. A developmental approach to alcohol drinking behaviour in adulthood: a follow-up study from age 8 to age 42. Addiction. 2008;103:48–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose RJ. How do adolescents select their friends? A behavior-genetic perspective. In: Pulkkinen L, Caspi A, editors. Paths to Successful Development: Personality in the Life Course. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2002. pp. 106–128. [Google Scholar]

- Rose RJ, Dick DM, Viken RJ, Pulkkinen L, Kaprio J. Drinking or abstaining at age 14: a genetic epidemiological study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1594–1604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Bates J. Temperament. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 3, Social, Emotional, and Personality Development. 5th Wiley; New York, NY: 1998. pp. 105–176. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ. Transactional Development: Operationalizing a Dynamic System. American Psychological Association; Washington DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Shedler J, Block J. Adolescent drug use and psychological health: a longitudinal inquiry. Am Psychol. 1990;45:612–630. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.5.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton B, Haynie DL, Crump AD, Eitel SP, Saylor KE. Peer and parent influences on smoking and drinking among early adolescents. Health Educ Behav. 2001;28:95–107. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MQ, Fitzhugh EC, Westerfield RC, Eddy JM. Family and peer influences on smoking behavior among American adolescents: an age trend. J Adolesc Health. 1995;16:200–203. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(94)00097-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M. Parental, sibling, and peer influences on adolescent substance use and alcohol problems. Appl Dev Sci. 2000;4:98–110. [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, Spear LP, Fuligni AJ, Angold A, Brown JD, Pine D, Smith GT, Giedd J, Dahl RE. Transitions into underage and problem drinking summary of developmental processes and mechanisms: ages 10–15. Alcohol Res Health. 2009;32:30–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker R. Alcohol use and alcohol use disorders: a developmental-biopsychosocial formulation covering the life course. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen D, editors. Developmental Psychopathology, Vol. 3: Risk, Disorder, and Adaptation. Wiley; NewYork, NY: 2006. pp. 620–656. [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA. Anticipating problem alcohol use developmentally from childhood into middle adulthood: what have we learned. Addiction. 2008;103:100–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02179.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Donovan JE, Masten AS, Mattson ME, Moss HB. Early developmental processes and the continuity of risk for underage drinking and problem drinking. Pediatrics. 2008;121:S252–S272. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2243B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]